The world’s largest emissions trading scheme has been launched. And it’s happening in China. And just like the EU, the Chinese leadership intends to wield it as an instrument in the fight against climate change to significantly curb the amount of CO2 emissions. Although both the EU and China speak of “emissions trading,” both systems differ considerably. Chinese emissions trading is much less ambitious; a cap on thermal power generation, for example, is completely absent. Even before the official introduction of emissions trading in China, it was clear that their system would have little impact on the amount of CO2 emitted in the People’s Republic in the first few years. Amelie Richter and Nico Becker analyze how both systems could become compatible in the near future.

The Chinese automotive supplier Weichai Power shows much higher ambitions. Through acquisitions, not least in Germany, the company from the province of Shandong has catapulted itself into the global top 10. Frank Sieren describes how this poses new challenges for the Swabian competition,

I hope you enjoy our latest issue

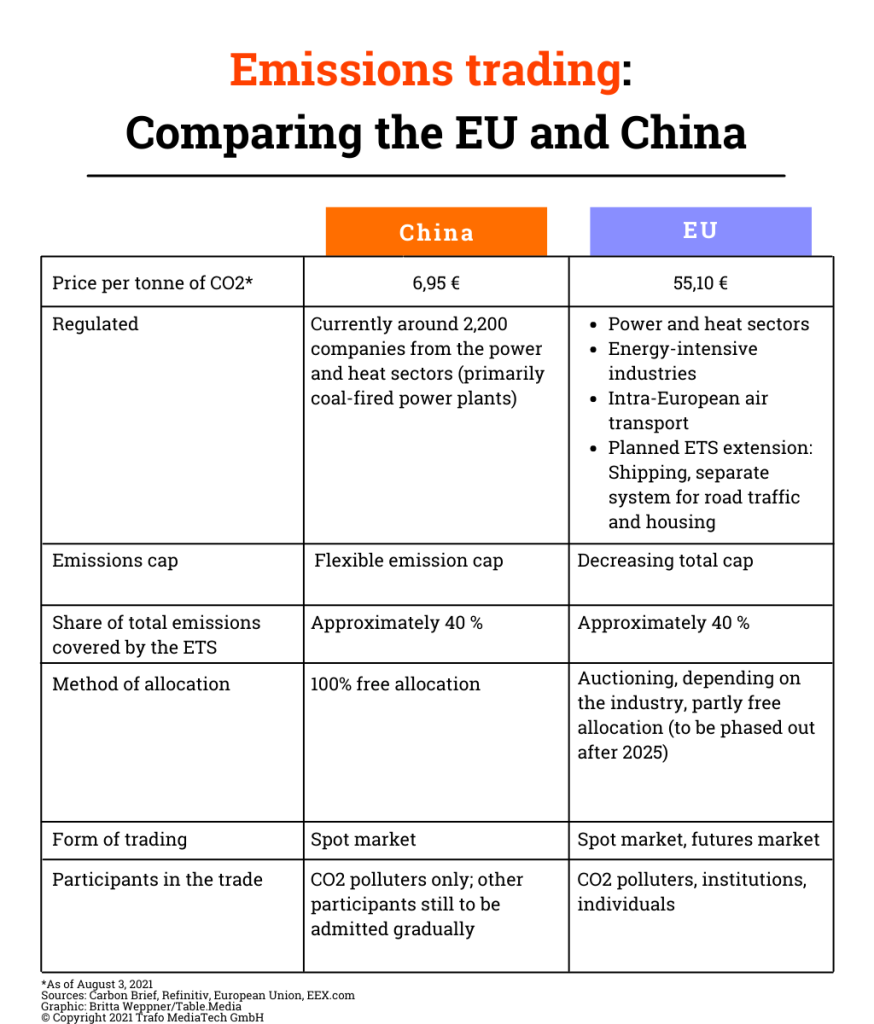

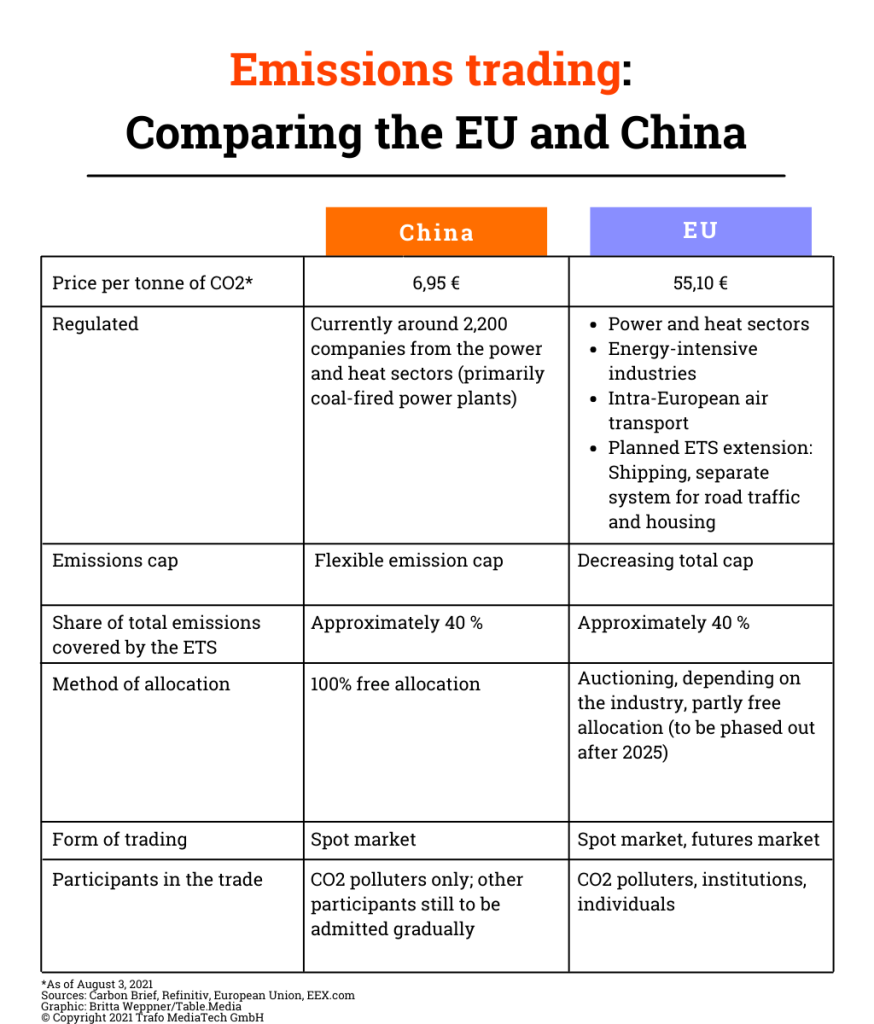

After almost ten years of preparation, China has launched its own emissions trading scheme. For the first time in just over three weeks, companies have been able to buy and sell CO2 allowances for almost 2,200 coal and gas-fired power plants. Measured in terms of included CO2 emissions, the Chinese ETS is the largest in the world. But experts doubt its effect on climate protection. Beijing is even facing climate levies in the future because Chinese emissions trading is not ambitious enough and does not meet the requirements of the European carbon border adjustment.

When trading officially began in China, EU Commission Vice-President and Commissioner for Climate Action Frans Timmermans were still congratulating the People’s Republic. But these pretty words could soon be a thing of the past. Because just two days prior to the trading launch, the EU Commission had presented twelve legislative proposals as part of its climate package for the European Union, including a possible extension of the ETS to shipping, a separate ETS for buildings and road transport – and a CO2 border adjustment (as reported by China.Table). This would require other countries to pay taxes on products produced outside the EU with higher CO2 emissions. Third countries with an ETS based on the European model, have a chance of being exempted – if their system can be incorporated into EU emissions trading

However, it is extremely unlikely that the People’s Republic will end up on the list of exempted states in the near future. A look at the details: At the end of the first trading day, the price for a ton of CO2 in the People’s Republic was the equivalent of around 6.90 euros. This data already shows a big difference to European emissions trading – because in the EU, a ton of CO2 now regularly costs over 50 euros. In addition, EU emissions trading covers around 10,000 plants in the energy sector, as well as energy-intensive industries and intra-European flights. China is currently still far behind in this respect.

However, both systems not only differ in terms of price and scope significantly. In the Chinese trading system, emission certificates are allocated flexibly. There is no fixed upper limit on how many greenhouse gases participating companies are allowed to emit in total. There are also no current plans to remove allowances from the market in the coming years and to increase the price of atmospheric pollution through the resulting scarcity. Chinese companies also do not have to bid on allowances, instead, they are allocated to them free of charge. Only if they emit more CO2 than they are previously allowed, they have to buy pollution rights on the market.

Experts see little true impact of the current system when it comes to a reduction of climate-damaging emissions (as reported by China.Table). By comparison, the EU has a decreasing cap on the number of CO2 allowances traded. Emissions trading is thus compatible with the climate goals of 2030. In addition, the EU sees a larger share of emission rights now auctioned instead of allocated for free. Currently, the ambitions of China’s emissions scheme are still too low to be exempted from the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (EU-CBAM) in the near future.

However, implementation is not planned until 2026. This gives China a few years to make its emissions trading scheme compatible with CBAM. Analysts also assume that emissions trading will be regularly tightened: Yan Qin, a climate analyst at Refinitiv, a provider of financial market data, speaking to China.Table, stated that authorities are in the process of “including more industrial sectors in the emissions trading system, such as the cement and aluminum sectors next year”(as reported by China.Table). China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection has a clear goal of bringing more industrial sectors into the emissions trading scheme by 2025, he added. However, it could still leave problems for one key industrial sector: Due to the complex calculation of CO2 emissions, Qin says, “it is not as easy to integrate the steel sector into emissions trading.”

But even if it were possible to integrate all the sectors covered by the European ETS into Chinese trading, the CBAM could still apply climate tariffs. According to analyst Qin, CO2 prices of Chinese emissions trading would hardly reach the European price level in the short term. Qin expects CO2 prices in China to rise to the equivalent of about 21 euros by 2030. In the EU, on the other hand, a price of 90 euros is expected for 2030. The question remains, whether Chinese manufacturing companies would then be required to pay the price difference to European emissions trading under the CBAM, says Qin.

Experts at the consultancy Trivium China explain that the first year of the trading system is primarily aimed at the establishment of the CO2 market in the People’s Republic. Companies are to be encouraged to participate and will initially already have their hands full with registering their emissions in the first place. According to Cory Combs, climate and energy specialist at Trivium China, it will take two to five years to establish the Chinese emissions trading scheme. By then, he says, a pricing mechanism will be in place that can help mitigate CO2 emissions.

Moreover, a lot of political effort between the EU and China will be needed to smooth out the growing resentment regarding the CBAM, as a Beijing-based ETS expert had told China.Table. The People’s Republic sees the planned border levy as a trade barrier deliberately imposed by the EU in the form of a CO2 tax or “climate tariff”. Brussels would have to explain the climate proposals to its trading partners in a comprehensible way, the analyst said. There is still a long way to go before both ETS can be merged. And more unanswered questions remain: What happens if the cost of a tonne of CO2 outside the EU exceeds the prices within the European emissions trading scheme? Will the EU then have to pay compensation for the import? A reverse CBAM, so to speak? Details such as these have not yet been sufficiently discussed, the analyst said. In his opinion, the introduction of a Chinese CO2 border adjustment is also not completely ruled out for the future. Amelie Richter/Nico Beckert

Nine times as many Chinese automotive suppliers made it into the top 100 last year than in the past ten years. Market analysts at Berylls Strategy Advisors came to this conclusion by compiling an annual ranking of the world’s 100 top suppliers in revenue since 2011. With sales of €71 billion, Bosch topped the list for the sixth year in a row. However, in 2018, sales were still at 78 billion. The list remained unchanged until the 9th spot. With Weichai Power in 10th, a Chinese company has now reached the top ten for the first time.

At the end of 2020, the company from the Province of Shandong was the world’s largest engine manufacturer and China’s largest mechanical engineering company, with sales equivalent to just under 40 billion euros. According to its own statement, Weichai aims to reach the 100 billion US dollar mark by 2025. Weichai’s Hong Kong-listed shares have risen by nearly 500 percent since August 2015. Weichai Power was founded in 1946 in Weifang as a factory for diesel engines and has since expanded its core businesses to include the assembly of engines, transmissions, axles and automotive electronics.

The state-owned group was able to rise to 10th place primarily through international acquisitions, including several German companies. Most recently, Weichai purchased the Swabian company Aradex in Lorch near Stuttgart. With 80 employees, the company has been active in the field of drive technology for more than 30 years. The company’s roots lie in industrial Control and drive engineering for production machinery. However, Aradex has recently also specialized in the fields of electrification and hybridization of commercial vehicles, construction machinery and special ships. In addition to alternative drives for commercial vehicles and electric motors, Aradex also brings a great amount of knowledge in DC/DC converters for fuel cells to the table. Aradex became part of the Weichai Group at the end of 2019. The board of directors has remained unchanged, but the supervisory board has been reappointed. Weichai’s CEO Wang Zhixin has taken over as chairman, with Wu Guogang, also of Weichai, acting as his deputy. Weichai holds an 80 percent stake in Aradex.

In addition, Weichai now holds 45 percent of the Wiesbaden-based forklift manufacturer Kion. Back in 2012, Weichai had invested 738 million euros and held 25 percent of the Hessian company in one fell swoop. At the time, it was the largest investment made by a Chinese company in Germany. The company first came to prominence in Germany in 2012 with its acquisition of Linde Hydraulics, a manufacturer based in Aschaffenburg that specializes in hydraulic drive systems for forklifts, agricultural machinery and trucks.

Weichai also holds a majority stake (51 percent) in VDS Holding GmbH, a globally acting high-tech company based in Wolfern in Upper Austria. VDS specializes in the development and production of innovative drive systems for work machinery, municipal applications, construction machinery and high-powered off-road vehicles. The company was sold in 2020. Since 2019 Weichai has also held another 51 percent majority stake in Power Solutions International, Inc. (PSI) of Chicago, a leading manufacturer of eco-friendly propulsion systems such as gas engines. The political frictions between Beijing and the U.S. government under Donald Trump could do no harm to this deal.

Back in 2018, Weichai entered into a strategic partnership with Canadian fuel cell manufacturer Ballard Power Systems. At the time, Weichai acquired a 19.9 percent stake in Ballard for $163 million. The company also acquired Baudouin, a manufacturer of boat engines in southern France, and Italian yacht builder Ferretti Group, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of yachts. The 27 percent stake cost Weichai about 178 million euros in 2012. Weichai now has around 95,000 employees worldwide.

In addition to Weichai, eight other Chinese automotive suppliers made it into the top 100. A great advantage for these companies was the fact that the economy recovered more quickly from the effects of the Covid than the West. Another reason is the growth of the Chinese auto market, as so does local expertise and demand for products from domestic companies, with more and more tech groups like Huawei now getting in on the action. Cars are increasingly becoming a fully networked high-tech product in China. German suppliers like ZF are also responding to the trend and offer more and more software. At this spring’s auto show in Shanghai, the company at Lake Constance unveiled the next generation of its high-performance computer, the ZF Pro AI. “It is currently the world’s most flexible, scalable and powerful supercomputer for the automotive industry,” said Holger Klein, member of ZF Board of Management for the Asia Pacific, during the presentation. The growing importance of batteries and semiconductors also plays a role in the shift to Asia, with companies such as CATL, TSMC, Panasonic, BYD, and LG Chem becoming key global suppliers.

With many interruptions in production, however, the Covid pandemic has also left its mark on globally active automotive suppliers. Revenues of the 100 largest groups in 2020 dropped by 12.7 percent compared to the previous year. In 2019, they had still achieved a 4.3 percent increase in sales. Weichai, on the other hand, only suffered losses of two percent. Fewer than ten suppliers were able to increase their sales in 2020 compared to the same period of the previous year. Among German suppliers, only Infineon managed to do so.

The automotive supplier ZF posted losses of €177 million in 2020. In the first half of 2021, however, the company was able to increase its sales again by 43 percent to €19.3 billion compared to the same period of the previous year.

For the first time after Brexit, UK universities have more prospective students from China than from the EU. The number of applicants from the EU dropped by 43 percent to 28,400, according to the British university admissions service UCAS. This compares with 28,490 applications from China. The number of applicants from the People’s Republic had more than doubled since 2017. The sharp decline of EU applicants was deemed “disappointing” but expected, as news agency Bloomberg quoted the head of the lobby group Universities U.K., Stephanie Harris. Since Brexit, EU students have to pay higher fees at most British universities.

The shift in the Origin of students falls amid rising tensions between London and Beijing over several disputes. British intelligence agencies had raised concerns about connections between universities and the Chinese government, according to the Bloomberg report.

However, British educational institutions need students from abroad, explains Nick Hillman of the think-tank Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI). According to a HEPI study, international students contributed an estimated 22.6 billion pounds (about 26 billion euros) to the British economy in 2015/16 alone. British universities would now “feel a very cold wind” if Chinese students stopped applying, Hillman said.

ByteDance rival Kuaishou Technology has pulled the plug on its video-sharing app Zynn in the US. The Chinese social media company told users in a message on Wednesday that Zynn would be discontinued as of Aug. 20, Bloomberg reports. According to the statement, the app, a TikTok lookalike that launched in North American markets just last year, will remove all user data 45 days after the shutdown. However, Kuaishou’s other overseas products will not be affected, according to the report. The Chinese internet company also operates apps Kwai and SnackVideo for markets like Brazil and Indonesia. Kuaishou did not provide further details on the closure of Zynn.

The app has had trouble attracting users in the US. The smartphone app had only 200,000 monthly active users in June this year, down from around three million in August last year, technology news portal Techcrunch reported. According to the report, last year’s review revealed that Zynn was paying users to watch videos to boost its ranking in the US iOS App Store. The app had also been blocked from the Play Store after reports accusing the platform of hosting a great number of videos stolen from other apps. ari

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has decided not to punish Athlete duo Bao Shanju and Zhong Tianshi. The Olympic gold medalists of the women’s team sprint track cycling had each worn a pin depicting the head of The People’s Republic founder Mao Zedong at the award ceremony on Monday. According to Article 50 of the Olympic Charter, however, political symbols are prohibited during competitions. The IOC demands strict neutrality, especially during award ceremonies. The Chinese team management has assured “that this will not happen again”, an IOC spokesman said on Wednesday. grz

When it comes to the Chinese economy, I have been a congenital optimist for over 25 years. But now I have serious doubts. The Chinese government has taken dead aim at its dynamic technology sector, the engine of China’s New Economy. Its recent actions are symptomatic of a deeper problem: the state’s efforts to control the energy of animal spirits. The Chinese Dream, President Xi Jinping’s aspirational vision of a “great modern socialist country” by 2049, could now be at risk.

At first, it seemed as if the authorities were concerned about a one-off personnel problem when they sent a stern message to the irreverent Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, the world’s largest e-commerce platform. Ma’s ill-timed comments at a Shanghai financial forum in late October 2020 about the “pawnshop” mentality of the bank-centric Chinese financial system crossed the line for China’s leaders. Early the following month, a record $34 billion initial public offering for Ant Group, the behemoth fintech spinoff of Alibaba, was canceled less than 48 hours before the scheduled listing. Five months later, Alibaba itself was fined a record $2.8 billion for alleged anti-monopoly violations.

And now it’s Didi Chuxing’s turn. Didi, the Uber-like Chinese ridesharing service, apparently had the audacity to raise $4.4 billion in US capital markets, despite rumored objections from Chinese officials. After forcing the removal of more than 25 of Didi’s apps from Chinese Internet platforms, talk of a fine that might exceed the earlier penalty imposed on Alibaba, or even a possible delisting, is rampant.

Moreover, there are signs of a clampdown on many other leading Chinese tech companies, including Tencent (Internet conglomerate), Meituan (food delivery), Pinduoduo (e-commerce), Full Truck Alliance (truck-hailing apps Huochebang and Yunmanman), Kanzhun’s Boss Zhipin (recruitment), and online private tutoring companies like TAL Education Group and Gaotu Techedu. And all of this follows China’s high-profile crackdown on cryptocurrencies.

It is not as if there were a lack of reasons – in some cases, like cryptocurrencies, perfectly legitimate reasons – for China’s anti-tech campaign. Data security is the most oft-cited justification. This is understandable in one sense, considering the high value the Chinese leadership places on its proprietary claims over Big Data, the high-octane fuel of its push into artificial intelligence. But it also smacks of hypocrisy in that much of the data has been gathered from the surreptitious gaze of the surveillance state.

The issue, however, is not justification. Actions can always be explained, or rationalized, after the fact. The point is that, for whatever reason, Chinese authorities are now using the full force of regulation to strangle the business models and financing capacity of the economy’s most dynamic sector.

Nor is the assault on tech companies the only example of moves that restrain the private economy. Chinese consumers are also suffering. Rapid population aging and inadequate social safety nets for retirement income and health care have perpetuated households’ unwillingness to convert precautionary saving into discretionary spending on items like motor vehicles, furniture, appliances, leisure, entertainment, travel, and the other trappings of more mature consumer societies.

Yes, the absolute scale of these activities, like everything in China, is large. But as a share of its overall economy, household consumption is still less than 40% of GDP – by far the smallest share of any major economy.

The reason is that China has yet to create a culture of confidence in which its vast population is ready for a transformative shift in saving and consumption patterns. Only when households feel more secure about an uncertain future will they broaden their horizons and embrace aspirations of more expansive lifestyles. It will take nothing less than that for a consumer-led rebalancing of China’s economy finally to succeed.

Confidence among businesses and consumers alike is a critical underpinning of any economy. Nobel Prize-winning economists George Akerlof and Robert Shiller view confidence as the cornerstone of a broader theory of “animal spirits.” This notion, widely popularized by John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s, is best thought of as a “spontaneous urge to action” that takes aggregate demand well beyond the underpinnings of personal income or corporate profit.

Keynes viewed animal spirits as the essence of capitalism. For China, with its mixed model of market-based socialism, animal spirits operate differently. The state plays a far more active role in guiding markets, businesses, and consumers than it does in other major economies. Yet the Chinese economy, no less than others, still requires a foundation of trust – trust in the consistency of leadership priorities, in transparent governance, and in wise regulatory oversight – to flourish.

Modern China lacks this foundation of trust that underpins animal spirits. But while this has long been an obstacle to Chinese consumerism, now distrust is creeping into the business sector, where the government’s assault on tech companies is antithetical to the creativity, energy, and sheer hard work they require to grow and flourish in an intensely competitive environment.

I have frequently raised concerns about the excesses of fear-driven precautionary saving as a major impediment to consumer-led Chinese rebalancing. But the authorities’ recent moves against the tech sector could be a tipping point. Without entrepreneurial energy, the creative juices of China’s New Economy will be sapped, along with hopes for a long-promised surge of indigenous innovation.

China’s mounting deficit of animal spirits could deal a severe, potentially lethal, blow to my own long-standing optimistic prognosis for the “Next China” – the title of a course that I have taught at Yale for the past 11 years. As I caution my students in the first class, the syllabus is a moving target.

Stephen S. Roach is a faculty member at Yale University, former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, and author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2021.

www.project-syndicate.org

Bastian Grund has moved back to Germany after resigning from his position as Head of BioLab at Evonik in Shanghai. He now works as a Group Controlling Officer in Hanau, also at Evonik.

Tobias Hofemeier has been Air Logistics Director for Hong Kong, Macau and South China at logistics and freight transport company Kuehne + Nagel since the beginning of June. He previously held the position as executive for European Gateway and Procurement Air Logistics.

Many major Chinese cities are going back into lockdown mode after the country experienced its largest Covid outbreak in several provinces in more than a year. Masks are now mandatory again. As it is for this driver near Shanghai’s Pudong Airport. It has been a ground for several recent infection cases.

The world’s largest emissions trading scheme has been launched. And it’s happening in China. And just like the EU, the Chinese leadership intends to wield it as an instrument in the fight against climate change to significantly curb the amount of CO2 emissions. Although both the EU and China speak of “emissions trading,” both systems differ considerably. Chinese emissions trading is much less ambitious; a cap on thermal power generation, for example, is completely absent. Even before the official introduction of emissions trading in China, it was clear that their system would have little impact on the amount of CO2 emitted in the People’s Republic in the first few years. Amelie Richter and Nico Becker analyze how both systems could become compatible in the near future.

The Chinese automotive supplier Weichai Power shows much higher ambitions. Through acquisitions, not least in Germany, the company from the province of Shandong has catapulted itself into the global top 10. Frank Sieren describes how this poses new challenges for the Swabian competition,

I hope you enjoy our latest issue

After almost ten years of preparation, China has launched its own emissions trading scheme. For the first time in just over three weeks, companies have been able to buy and sell CO2 allowances for almost 2,200 coal and gas-fired power plants. Measured in terms of included CO2 emissions, the Chinese ETS is the largest in the world. But experts doubt its effect on climate protection. Beijing is even facing climate levies in the future because Chinese emissions trading is not ambitious enough and does not meet the requirements of the European carbon border adjustment.

When trading officially began in China, EU Commission Vice-President and Commissioner for Climate Action Frans Timmermans were still congratulating the People’s Republic. But these pretty words could soon be a thing of the past. Because just two days prior to the trading launch, the EU Commission had presented twelve legislative proposals as part of its climate package for the European Union, including a possible extension of the ETS to shipping, a separate ETS for buildings and road transport – and a CO2 border adjustment (as reported by China.Table). This would require other countries to pay taxes on products produced outside the EU with higher CO2 emissions. Third countries with an ETS based on the European model, have a chance of being exempted – if their system can be incorporated into EU emissions trading

However, it is extremely unlikely that the People’s Republic will end up on the list of exempted states in the near future. A look at the details: At the end of the first trading day, the price for a ton of CO2 in the People’s Republic was the equivalent of around 6.90 euros. This data already shows a big difference to European emissions trading – because in the EU, a ton of CO2 now regularly costs over 50 euros. In addition, EU emissions trading covers around 10,000 plants in the energy sector, as well as energy-intensive industries and intra-European flights. China is currently still far behind in this respect.

However, both systems not only differ in terms of price and scope significantly. In the Chinese trading system, emission certificates are allocated flexibly. There is no fixed upper limit on how many greenhouse gases participating companies are allowed to emit in total. There are also no current plans to remove allowances from the market in the coming years and to increase the price of atmospheric pollution through the resulting scarcity. Chinese companies also do not have to bid on allowances, instead, they are allocated to them free of charge. Only if they emit more CO2 than they are previously allowed, they have to buy pollution rights on the market.

Experts see little true impact of the current system when it comes to a reduction of climate-damaging emissions (as reported by China.Table). By comparison, the EU has a decreasing cap on the number of CO2 allowances traded. Emissions trading is thus compatible with the climate goals of 2030. In addition, the EU sees a larger share of emission rights now auctioned instead of allocated for free. Currently, the ambitions of China’s emissions scheme are still too low to be exempted from the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (EU-CBAM) in the near future.

However, implementation is not planned until 2026. This gives China a few years to make its emissions trading scheme compatible with CBAM. Analysts also assume that emissions trading will be regularly tightened: Yan Qin, a climate analyst at Refinitiv, a provider of financial market data, speaking to China.Table, stated that authorities are in the process of “including more industrial sectors in the emissions trading system, such as the cement and aluminum sectors next year”(as reported by China.Table). China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection has a clear goal of bringing more industrial sectors into the emissions trading scheme by 2025, he added. However, it could still leave problems for one key industrial sector: Due to the complex calculation of CO2 emissions, Qin says, “it is not as easy to integrate the steel sector into emissions trading.”

But even if it were possible to integrate all the sectors covered by the European ETS into Chinese trading, the CBAM could still apply climate tariffs. According to analyst Qin, CO2 prices of Chinese emissions trading would hardly reach the European price level in the short term. Qin expects CO2 prices in China to rise to the equivalent of about 21 euros by 2030. In the EU, on the other hand, a price of 90 euros is expected for 2030. The question remains, whether Chinese manufacturing companies would then be required to pay the price difference to European emissions trading under the CBAM, says Qin.

Experts at the consultancy Trivium China explain that the first year of the trading system is primarily aimed at the establishment of the CO2 market in the People’s Republic. Companies are to be encouraged to participate and will initially already have their hands full with registering their emissions in the first place. According to Cory Combs, climate and energy specialist at Trivium China, it will take two to five years to establish the Chinese emissions trading scheme. By then, he says, a pricing mechanism will be in place that can help mitigate CO2 emissions.

Moreover, a lot of political effort between the EU and China will be needed to smooth out the growing resentment regarding the CBAM, as a Beijing-based ETS expert had told China.Table. The People’s Republic sees the planned border levy as a trade barrier deliberately imposed by the EU in the form of a CO2 tax or “climate tariff”. Brussels would have to explain the climate proposals to its trading partners in a comprehensible way, the analyst said. There is still a long way to go before both ETS can be merged. And more unanswered questions remain: What happens if the cost of a tonne of CO2 outside the EU exceeds the prices within the European emissions trading scheme? Will the EU then have to pay compensation for the import? A reverse CBAM, so to speak? Details such as these have not yet been sufficiently discussed, the analyst said. In his opinion, the introduction of a Chinese CO2 border adjustment is also not completely ruled out for the future. Amelie Richter/Nico Beckert

Nine times as many Chinese automotive suppliers made it into the top 100 last year than in the past ten years. Market analysts at Berylls Strategy Advisors came to this conclusion by compiling an annual ranking of the world’s 100 top suppliers in revenue since 2011. With sales of €71 billion, Bosch topped the list for the sixth year in a row. However, in 2018, sales were still at 78 billion. The list remained unchanged until the 9th spot. With Weichai Power in 10th, a Chinese company has now reached the top ten for the first time.

At the end of 2020, the company from the Province of Shandong was the world’s largest engine manufacturer and China’s largest mechanical engineering company, with sales equivalent to just under 40 billion euros. According to its own statement, Weichai aims to reach the 100 billion US dollar mark by 2025. Weichai’s Hong Kong-listed shares have risen by nearly 500 percent since August 2015. Weichai Power was founded in 1946 in Weifang as a factory for diesel engines and has since expanded its core businesses to include the assembly of engines, transmissions, axles and automotive electronics.

The state-owned group was able to rise to 10th place primarily through international acquisitions, including several German companies. Most recently, Weichai purchased the Swabian company Aradex in Lorch near Stuttgart. With 80 employees, the company has been active in the field of drive technology for more than 30 years. The company’s roots lie in industrial Control and drive engineering for production machinery. However, Aradex has recently also specialized in the fields of electrification and hybridization of commercial vehicles, construction machinery and special ships. In addition to alternative drives for commercial vehicles and electric motors, Aradex also brings a great amount of knowledge in DC/DC converters for fuel cells to the table. Aradex became part of the Weichai Group at the end of 2019. The board of directors has remained unchanged, but the supervisory board has been reappointed. Weichai’s CEO Wang Zhixin has taken over as chairman, with Wu Guogang, also of Weichai, acting as his deputy. Weichai holds an 80 percent stake in Aradex.

In addition, Weichai now holds 45 percent of the Wiesbaden-based forklift manufacturer Kion. Back in 2012, Weichai had invested 738 million euros and held 25 percent of the Hessian company in one fell swoop. At the time, it was the largest investment made by a Chinese company in Germany. The company first came to prominence in Germany in 2012 with its acquisition of Linde Hydraulics, a manufacturer based in Aschaffenburg that specializes in hydraulic drive systems for forklifts, agricultural machinery and trucks.

Weichai also holds a majority stake (51 percent) in VDS Holding GmbH, a globally acting high-tech company based in Wolfern in Upper Austria. VDS specializes in the development and production of innovative drive systems for work machinery, municipal applications, construction machinery and high-powered off-road vehicles. The company was sold in 2020. Since 2019 Weichai has also held another 51 percent majority stake in Power Solutions International, Inc. (PSI) of Chicago, a leading manufacturer of eco-friendly propulsion systems such as gas engines. The political frictions between Beijing and the U.S. government under Donald Trump could do no harm to this deal.

Back in 2018, Weichai entered into a strategic partnership with Canadian fuel cell manufacturer Ballard Power Systems. At the time, Weichai acquired a 19.9 percent stake in Ballard for $163 million. The company also acquired Baudouin, a manufacturer of boat engines in southern France, and Italian yacht builder Ferretti Group, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of yachts. The 27 percent stake cost Weichai about 178 million euros in 2012. Weichai now has around 95,000 employees worldwide.

In addition to Weichai, eight other Chinese automotive suppliers made it into the top 100. A great advantage for these companies was the fact that the economy recovered more quickly from the effects of the Covid than the West. Another reason is the growth of the Chinese auto market, as so does local expertise and demand for products from domestic companies, with more and more tech groups like Huawei now getting in on the action. Cars are increasingly becoming a fully networked high-tech product in China. German suppliers like ZF are also responding to the trend and offer more and more software. At this spring’s auto show in Shanghai, the company at Lake Constance unveiled the next generation of its high-performance computer, the ZF Pro AI. “It is currently the world’s most flexible, scalable and powerful supercomputer for the automotive industry,” said Holger Klein, member of ZF Board of Management for the Asia Pacific, during the presentation. The growing importance of batteries and semiconductors also plays a role in the shift to Asia, with companies such as CATL, TSMC, Panasonic, BYD, and LG Chem becoming key global suppliers.

With many interruptions in production, however, the Covid pandemic has also left its mark on globally active automotive suppliers. Revenues of the 100 largest groups in 2020 dropped by 12.7 percent compared to the previous year. In 2019, they had still achieved a 4.3 percent increase in sales. Weichai, on the other hand, only suffered losses of two percent. Fewer than ten suppliers were able to increase their sales in 2020 compared to the same period of the previous year. Among German suppliers, only Infineon managed to do so.

The automotive supplier ZF posted losses of €177 million in 2020. In the first half of 2021, however, the company was able to increase its sales again by 43 percent to €19.3 billion compared to the same period of the previous year.

For the first time after Brexit, UK universities have more prospective students from China than from the EU. The number of applicants from the EU dropped by 43 percent to 28,400, according to the British university admissions service UCAS. This compares with 28,490 applications from China. The number of applicants from the People’s Republic had more than doubled since 2017. The sharp decline of EU applicants was deemed “disappointing” but expected, as news agency Bloomberg quoted the head of the lobby group Universities U.K., Stephanie Harris. Since Brexit, EU students have to pay higher fees at most British universities.

The shift in the Origin of students falls amid rising tensions between London and Beijing over several disputes. British intelligence agencies had raised concerns about connections between universities and the Chinese government, according to the Bloomberg report.

However, British educational institutions need students from abroad, explains Nick Hillman of the think-tank Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI). According to a HEPI study, international students contributed an estimated 22.6 billion pounds (about 26 billion euros) to the British economy in 2015/16 alone. British universities would now “feel a very cold wind” if Chinese students stopped applying, Hillman said.

ByteDance rival Kuaishou Technology has pulled the plug on its video-sharing app Zynn in the US. The Chinese social media company told users in a message on Wednesday that Zynn would be discontinued as of Aug. 20, Bloomberg reports. According to the statement, the app, a TikTok lookalike that launched in North American markets just last year, will remove all user data 45 days after the shutdown. However, Kuaishou’s other overseas products will not be affected, according to the report. The Chinese internet company also operates apps Kwai and SnackVideo for markets like Brazil and Indonesia. Kuaishou did not provide further details on the closure of Zynn.

The app has had trouble attracting users in the US. The smartphone app had only 200,000 monthly active users in June this year, down from around three million in August last year, technology news portal Techcrunch reported. According to the report, last year’s review revealed that Zynn was paying users to watch videos to boost its ranking in the US iOS App Store. The app had also been blocked from the Play Store after reports accusing the platform of hosting a great number of videos stolen from other apps. ari

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has decided not to punish Athlete duo Bao Shanju and Zhong Tianshi. The Olympic gold medalists of the women’s team sprint track cycling had each worn a pin depicting the head of The People’s Republic founder Mao Zedong at the award ceremony on Monday. According to Article 50 of the Olympic Charter, however, political symbols are prohibited during competitions. The IOC demands strict neutrality, especially during award ceremonies. The Chinese team management has assured “that this will not happen again”, an IOC spokesman said on Wednesday. grz

When it comes to the Chinese economy, I have been a congenital optimist for over 25 years. But now I have serious doubts. The Chinese government has taken dead aim at its dynamic technology sector, the engine of China’s New Economy. Its recent actions are symptomatic of a deeper problem: the state’s efforts to control the energy of animal spirits. The Chinese Dream, President Xi Jinping’s aspirational vision of a “great modern socialist country” by 2049, could now be at risk.

At first, it seemed as if the authorities were concerned about a one-off personnel problem when they sent a stern message to the irreverent Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, the world’s largest e-commerce platform. Ma’s ill-timed comments at a Shanghai financial forum in late October 2020 about the “pawnshop” mentality of the bank-centric Chinese financial system crossed the line for China’s leaders. Early the following month, a record $34 billion initial public offering for Ant Group, the behemoth fintech spinoff of Alibaba, was canceled less than 48 hours before the scheduled listing. Five months later, Alibaba itself was fined a record $2.8 billion for alleged anti-monopoly violations.

And now it’s Didi Chuxing’s turn. Didi, the Uber-like Chinese ridesharing service, apparently had the audacity to raise $4.4 billion in US capital markets, despite rumored objections from Chinese officials. After forcing the removal of more than 25 of Didi’s apps from Chinese Internet platforms, talk of a fine that might exceed the earlier penalty imposed on Alibaba, or even a possible delisting, is rampant.

Moreover, there are signs of a clampdown on many other leading Chinese tech companies, including Tencent (Internet conglomerate), Meituan (food delivery), Pinduoduo (e-commerce), Full Truck Alliance (truck-hailing apps Huochebang and Yunmanman), Kanzhun’s Boss Zhipin (recruitment), and online private tutoring companies like TAL Education Group and Gaotu Techedu. And all of this follows China’s high-profile crackdown on cryptocurrencies.

It is not as if there were a lack of reasons – in some cases, like cryptocurrencies, perfectly legitimate reasons – for China’s anti-tech campaign. Data security is the most oft-cited justification. This is understandable in one sense, considering the high value the Chinese leadership places on its proprietary claims over Big Data, the high-octane fuel of its push into artificial intelligence. But it also smacks of hypocrisy in that much of the data has been gathered from the surreptitious gaze of the surveillance state.

The issue, however, is not justification. Actions can always be explained, or rationalized, after the fact. The point is that, for whatever reason, Chinese authorities are now using the full force of regulation to strangle the business models and financing capacity of the economy’s most dynamic sector.

Nor is the assault on tech companies the only example of moves that restrain the private economy. Chinese consumers are also suffering. Rapid population aging and inadequate social safety nets for retirement income and health care have perpetuated households’ unwillingness to convert precautionary saving into discretionary spending on items like motor vehicles, furniture, appliances, leisure, entertainment, travel, and the other trappings of more mature consumer societies.

Yes, the absolute scale of these activities, like everything in China, is large. But as a share of its overall economy, household consumption is still less than 40% of GDP – by far the smallest share of any major economy.

The reason is that China has yet to create a culture of confidence in which its vast population is ready for a transformative shift in saving and consumption patterns. Only when households feel more secure about an uncertain future will they broaden their horizons and embrace aspirations of more expansive lifestyles. It will take nothing less than that for a consumer-led rebalancing of China’s economy finally to succeed.

Confidence among businesses and consumers alike is a critical underpinning of any economy. Nobel Prize-winning economists George Akerlof and Robert Shiller view confidence as the cornerstone of a broader theory of “animal spirits.” This notion, widely popularized by John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s, is best thought of as a “spontaneous urge to action” that takes aggregate demand well beyond the underpinnings of personal income or corporate profit.

Keynes viewed animal spirits as the essence of capitalism. For China, with its mixed model of market-based socialism, animal spirits operate differently. The state plays a far more active role in guiding markets, businesses, and consumers than it does in other major economies. Yet the Chinese economy, no less than others, still requires a foundation of trust – trust in the consistency of leadership priorities, in transparent governance, and in wise regulatory oversight – to flourish.

Modern China lacks this foundation of trust that underpins animal spirits. But while this has long been an obstacle to Chinese consumerism, now distrust is creeping into the business sector, where the government’s assault on tech companies is antithetical to the creativity, energy, and sheer hard work they require to grow and flourish in an intensely competitive environment.

I have frequently raised concerns about the excesses of fear-driven precautionary saving as a major impediment to consumer-led Chinese rebalancing. But the authorities’ recent moves against the tech sector could be a tipping point. Without entrepreneurial energy, the creative juices of China’s New Economy will be sapped, along with hopes for a long-promised surge of indigenous innovation.

China’s mounting deficit of animal spirits could deal a severe, potentially lethal, blow to my own long-standing optimistic prognosis for the “Next China” – the title of a course that I have taught at Yale for the past 11 years. As I caution my students in the first class, the syllabus is a moving target.

Stephen S. Roach is a faculty member at Yale University, former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, and author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2021.

www.project-syndicate.org

Bastian Grund has moved back to Germany after resigning from his position as Head of BioLab at Evonik in Shanghai. He now works as a Group Controlling Officer in Hanau, also at Evonik.

Tobias Hofemeier has been Air Logistics Director for Hong Kong, Macau and South China at logistics and freight transport company Kuehne + Nagel since the beginning of June. He previously held the position as executive for European Gateway and Procurement Air Logistics.

Many major Chinese cities are going back into lockdown mode after the country experienced its largest Covid outbreak in several provinces in more than a year. Masks are now mandatory again. As it is for this driver near Shanghai’s Pudong Airport. It has been a ground for several recent infection cases.