For International Women’s Day, our Climate.Table is published one day earlier than usual and particularly focuses on “Women and Climate“. This is not a “gender craze”, but an acknowledgment of the facts: True climate action is only possible if everyone has a say and can participate in decisions.

We, therefore, lay out what a feminist climate policy should look like. We present the ten most important women on the climate stage. We show how COPs are still male-dominated and climate plans of many countries forget women. And we feature a great scientist who is advancing feminist climate policy.

In addition, we present background information on the election and climate policy in Nigeria. We also cover signs of hope: The new UN High Seas Treaty can also benefit the climate; the decisive body on the loss and damage fund at the UN level is finally ready to work; Vanuatu will take climate change to international court.

So many reasons to read Climate.Table. And soon to hear and see, too: On March 23 at 12 p.m., I will be joined by Jennifer Morgan for a live conversation at Table.Media. With the Climate State Secretary at the German Federal Foreign Office, we want to take a look ahead to an exciting year: World Bank reform, IPCC report, Petersberg Climate Dialogue, Global Stocktake, COP28 and much more. Feel free to join us here and spread the word!

And finally: If you like the Climate.Table, please forward us. If this mail was forwarded to you: Here you can try the briefing free of charge.

The German foreign climate policy strategy, led by the Federal Foreign Office, is not yet finished. It could be presented in late March. However, one thing is already clear: It will be embedded in the guidelines for a feminist foreign policy that Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock presented to the public last week – together with Development Minister Svenja Schulze, whose ministry will also be pursuing a feminist strategy in the future.

The plans of the two ministries go beyond mere support for women. Feminist policy means changing unjust power structures, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) says. Feminist foreign policy wants to “achieve that all people enjoy the same rights,” writes the foreign minister. Societies that would strive for this would be “more peaceful, more just, more sustainable and more economically successful”.

This also has implications for foreign climate policy. Through their feminist approach, both ministers want to strengthen women’s rights, for example, the right to education; give women better access to resources from which they have so far often been excluded; and increase the representation of women in political offices or decision-making bodies. In addition, both ministries announced plans to gear their budgets more closely to feminist criteria and increase the number of women in leadership positions internally as well.

This is one reason why women – and other socially marginalized groups – should be particularly considered in climate policy: They often suffer particularly from global warming. This is illustrated by five examples from the recently published Climate Inequality Report 2023:

In this way, global warming can exacerbate existing injustices. Sheena Anderson is responsible for climate justice and climate foreign policy at the Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy (CFFP) in Berlin. She says that a climate policy that does not take this into account could push marginalized groups even further into the sidelines. A feminist policy aims to avoid this.

According to the CFFP, an international climate policy that takes gender aspects into account can accelerate the transition to a climate-friendly society. It benefits everyone – and it also fulfills obligations under international agreements, for example within the UNFCCC.

“Without feminism, there can be no climate justice,” says Anderson. “The climate crisis hits marginalized people particularly hard. Feminism means including them in particular in the search for solutions.” In this way, she says, previously unappreciated knowledge can be tapped.

The BMZ also points out in its guidelines that “indigenous knowledge, for example, is still not adequately included in solutions to the climate crisis”. The reason is “the devaluation of knowledge and education systems in the course of colonialism” – part of the unjust power structures that feminist policies are set to change.

A BMZ spokeswoman told Climate.Table that women’s knowledge “must be used in agriculture, natural resource management and energy use”. For this reason, the BMZ wants to “specifically promote women and involve them equally” in projects in partner countries.

Then climate would become more successful: For example, in Zambia, where women have been specially trained to improve the local water supply; in Nepal, where women have organized themselves and thus fought for the right to own land; or in the Global Shield against Climate Risks, in which the ministry has committed itself to a strong role for women. So far, however, the spokeswoman admits, “it is mainly men who make the decisions in most partner countries. It’s a matter of changing existing power structures and making women visible.”

CFFP expert Sheena Anderson gives five examples of how feminist approaches could make climate policy more equitable:

According to the CFFP, feminist policies that seek to address all dimensions of disadvantage must consider many factors. Among them:

Gina Cortés says: A truly feminist climate policy must be developed from the regions, together with the people who live there. Cortés, a Colombian national, is gender and climate policy manager for Women Engage for a Common Future (WECF), an organization that works with other civil society organizations to contribute to the UNFCCC process. Together with Bridget Burns, director of the New York-based global women’s rights organization WEDO, Cortés is the official focal point for the UNFCCC’s Women’s and Gender Constituency (WGC).

“Climate change affects all of us differently, depending on gender, class, ethnicity and skin color,” Cortés says. “That’s why there is not one feminism. It’s different in Asia than in Latin America or Africa.” That’s why feminist climate policies need to take regional specificities into account, she says.

For Cortés, feminist politics is a response to the existing capitalist, extractivist, neocolonial economic model. A feminist climate policy means overcoming this model rather than repeating it under climate-friendly auspices, she says. This would include, for example, debt relief.

“Feminist climate politics must be decolonizing, anti-racist and intersectional. Otherwise, it won’t work,” Cortés says. “We have to begin to understand that there are other ways to live well than within the existing model”: for example, based on a solidarity-based, ecological economy that strengthens interpersonal relationships and leaves room for spirituality.

“A different world is possible,” Cortés says. But instead, she sees the danger that instead of coal, Europe will import renewable energy from countries like Colombia in the future – and will also show no consideration for the local indigenous population, just to maintain its own standard of living. She asks, “Currently, Germany has even increased coal imports from Colombia. How does that fit with feminist development and foreign policy?”

On June 1, Spain will take over the EU Council Presidency. This means that one of the “best experts in international climate negotiations” will lead the EU to COP28. Spain’s Minister for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge was already part of negotiations as Secretary of State for Climate Change (2008-2011) prior to the failed Copenhagen Conference in 2009. A lawyer, she held various positions in the Spanish Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Environment (1996-2004) before becoming Director General for Climate Affairs (2004-2008). From 2014 to 2018, Ribera headed the Paris-based think tank IDDRI before moving back to the Socialist government in Madrid. Ribera’s negotiating style is considered open, communicative, and tough on issues.

Campaigning for the environment and justice can be dangerous: That is what Syeda Rizwana Hasan experienced at the end of January when she and her team were attacked in southern Bangladesh and stones were thrown at their vehicles. She was on-site to assess a controversial construction project. Internationally, Hasan has chosen law, not climate diplomacy, to help push back against greenhouse gas emissions: The 55-year-old is a lawyer at the Bangladesh High Court and Chair of the board of the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA). Among other things, she campaigned against the construction of coal-fired power plants near the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest. Her goal: Using the sharpest legal sword to fight climate change offenders – international criminal law. In 2009, she was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for her commitment.

Her appearance in defense of island nations already left a lasting impression at the World Climate Change Conference in Glasgow at the end of 2021. On stage in Sharm El-Sheikh, at the UN General Assembly and in many international forums, Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados and former lawyer, is now a powerful voice: The Caribbean politician fought for better access to international funding for countries in the Global South and financial compensation from major emitters in climate change. “If I pollute your property, you expect me to compensate you,” she said. But Mottley has sparked much more than just a demand for more money: Her Bridgetown Initiative aims to create an international alliance to put major financial players like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and the development banks on a climate track: No more funding for fossil fuels, more money and justice for victims of climate change, swift aid when disasters strike. Mottley wants to move the big levers.

The State Secretary and Special Envoy for International Climate Action in the German Foreign Ministry is a real insider on the international climate stage. No wonder: She has always been there since the start of COPs. Before changing roles to official climate policy, the political scientist and German studies graduate worked for WWF, E3G, the climate protection group CAN, the Potsdam Institute PIK and the World Resources Institute, among others. In 2016, she became head of Greenpeace International – here, too, she benefited from a large network of acquaintances and informal encounters as well as speaking frankly. Even as an activist, Morgan always had an open ear for opposite positions, and was more a diplomat than a radical. Morgan was born in the United States and has lived in Germany since 2003, before becoming a German citizen in 2021 in time for her appointment as Secretary of State.

The 20-year-old is the world’s best-known climate campaigner. It all began in 2018 when, at the age of 15, she started her “school strike for the climate” in front of the Swedish parliament to urge the government to meet its climate targets. Her small campaign inspired thousands of young people around the world to organize their own protests – and also generated a lot of hate for her around the world. By December 2018, more than 20,000 students – from the UK to Japan – had joined her protest and played hooky from school. A year later, she received the first of three nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize for her climate activism. In 2019, Thunberg sailed across the Atlantic on a yacht to attend a UN climate conference in New York. Enraged, she accused world leaders of not doing enough. “You all come to us young people for hope. How dare you. You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words,” she said.

The Ugandan Fridays for Future activist gained worldwide attention in 2020 because she was supposed to remain unknown: A news photo showing her alongside Greta Thunberg and other white climate activists was cropped to remove Nakate. Her reaction that the news agency had “not just deleted a photo, but a continent” made international headlines. Since then, the 26-year-old business economist, whose father was chair of the Rotary Club in Uganda’s capital Kampala, has been regarded as Africa’s voice for climate justice. The French-speaking daily Jeune Afrique named her one of the 100 most influential Africans in 2020. She founded the Rise Up Movement to make the voices of African climate activists heard, as well as a project to install solar panels in rural schools in Uganda. Vanessa Nakate is also the author of A Bigger Picture, a manifesto for inclusive climate action.

Since 2014, Sharan Burrow has been a member of the Global Commission for the Economy and Climate, co-chaired by Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Nicholas Stern and Paul Polman. But it is above all in her role as General Secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) since 2010 that she has made a name for herself on women, climate and workers’ rights. In the hallways of international climate conferences, the Australian with the distinctive voice and prickly humor emphasizes that global warming primarily affects the poorest. There is no getting around climate justice, is her credo. And if the preamble to the Paris Agreement notes climate justice as the “importance of ensuring the integrity of all ecosystems, including oceans, and the protection of biodiversity”, Sharan Burrow has done her part.

The director of the Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) describes herself as a feminist and environmental activist. An American national, she leads a global organization at the intersections of gender equality and environmental justice. For more than a decade, Burns has focused on advancing gender equality in climate policy at the global and national levels. Her work has involved organizing support and building capacity for women from the Global South to participate as part of their national delegations to UNFCCC conferences and intersessions through WEDO’s flagship Women Delegates Fund program.

What if we approached the climate crisis differently? In order to take action, we should not bury our heads in the sand, but display a healthy mix of outrage and confidence to take big leaps. This is the combination perfectly illustrated by the name of the podcast co-hosted by Costa Rican diplomat Christiana Figueres: “Outrage and Optimism”. A figurehead in the fight against climate change, the former Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC (2010-2016) – along with Laurence Tubiana – is widely credited with the success of the Paris Agreement in December 2015. The Costa Rican, who has worked across the public, private and non-profit sectors, was the first woman to hold the post and the first representative of the Global South. She comes from Costa Rica’s best-known political dynasty – both her father and brother were presidents of the country.

During COP21, Laurence Tubiana was one of the most important individuals. Together with Christiana Figueres, she is considered one of the architects of the Paris Agreement. No COP plenary, no bilateral meeting of the then French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius without his ambassador for climate negotiations. Due to a serious horse riding accident, she only wore sneakers to the conference – in a different color every day. Until COP21, she had headed the Paris-based think tank IDDRI, where she advocated decarbonization – the departure from the carbon-fuelled economy that was ultimately enshrined in the Paris Agreement. She currently heads the European Climate Foundation as director and is thus still present on the climate stage – as someone who networks herself and others, and gives ideas and drives policy.

The ruling All Progressives Congress candidate, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, has emerged as winner of the keenly contested Nigeria’s presidential election held on Saturday, February 25, 2023. President-elect Tinubu, Nigeria’s fifth president since the end of the military rule in 2009, was declared winner by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) after polling a total of 8.79 million votes, representing 35.2 percent of votes cast. He has his work cut out for him: He must revive an ailing economy, create jobs, reduce multidimensional poverty, tame inflation, battle widespread insecurity and entrench equity, fairness and justice to unite a polarized nation, and deal with the consequences of the climate crisis.

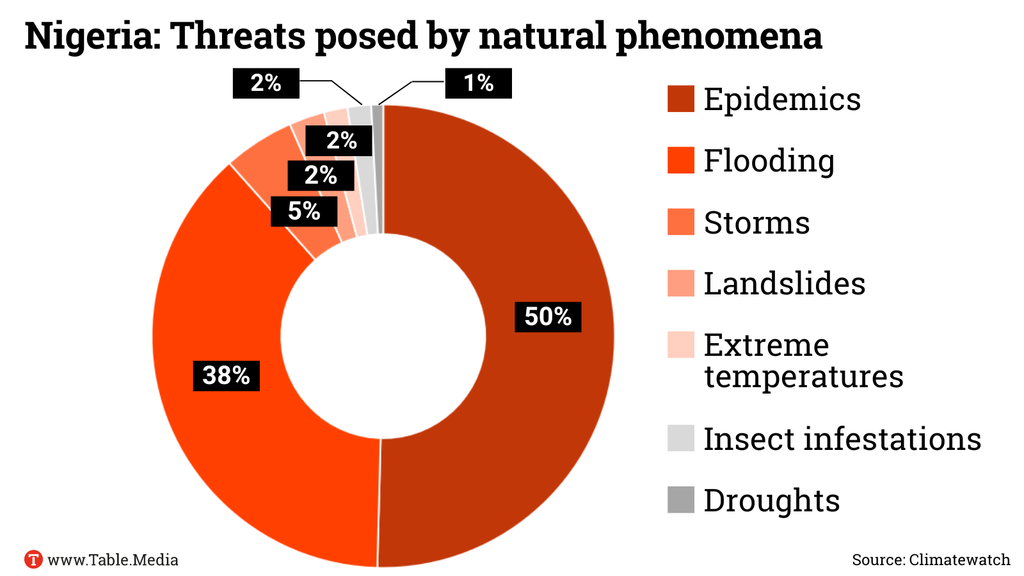

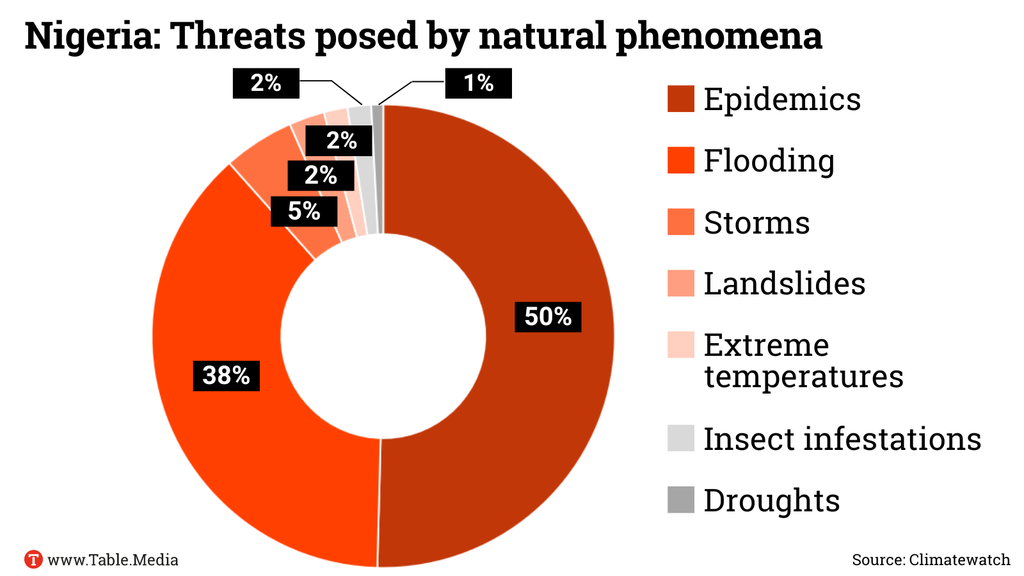

Socio-political and economic reforms around these multifaceted challenges headlined campaigns towards the recently concluded presidential election. Climate change was relatively muted in the candidates’ manifestos, though Nigeria suffers the deleterious effects of climate change. Adverse climate change subverts the country’s development and threatens the livelihoods of millions of Nigerians. Nigeria is the 53rd most climate-vulnerable country and the 6th least-ready country in the world to adapt to climate change.

Tinubu’s Renewed Hope 2023 manifesto situated climate change issues as one of the key challenges facing Nigeria’s agricultural sector. As countermeasures, Tinubu aims to increase agricultural productivity and complete the Great Green Wall. This is Africa’s flagship initiative of forest plantations to combat climate change and desertification and address food insecurity and poverty.

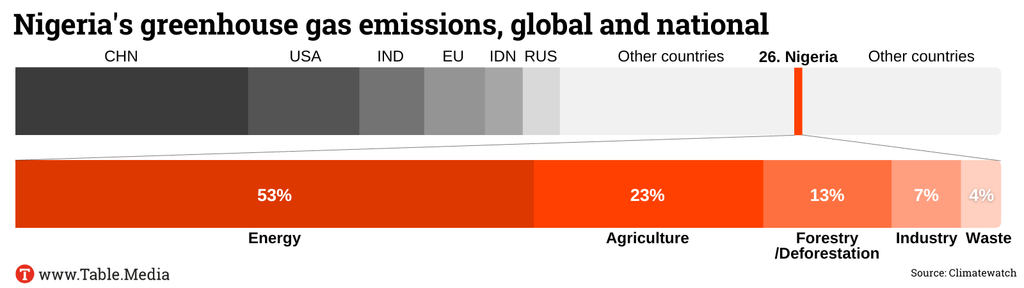

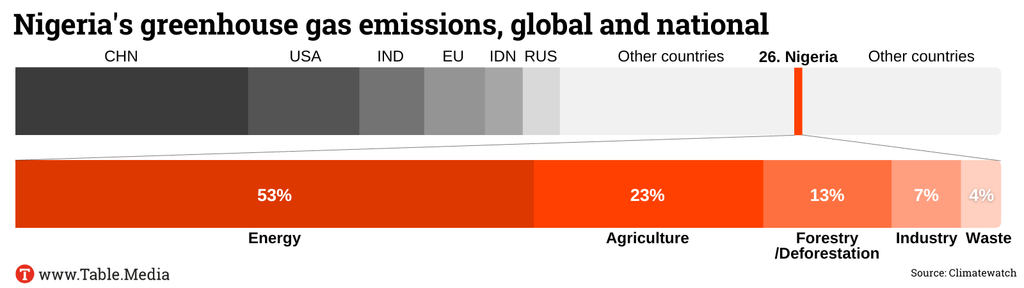

At the same time, Tinubu’s manifesto emphasizes increasing crude oil production to four million barrels a day by 2030 and increasing gas production by 20 percent. The oil sector is the primary source of government revenue in Nigeria, with roughly 25.55 billion US dollars in 2022, but the sector’s contribution to the country’s GDP is minuscule, just 4.34 percent of the country’s total real GDP in Q4 2022.

The primary energy sources in Nigeria are renewables and crude oil with shares of 47 percent and 41 percent respectively. Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan is to meet 57 percent of its energy demand using renewables by 2050 with crude oil declining to 33 percent. Tinubu’s renewable energy plan is based on Nigeria’s commitment to carbon neutrality by 2060 and aims to promote solar energy through grid connection and mini-grids.

The president is also the central figure in Nigerian climate policy. Climate measures are largely coordinated by the federal government. All climate policies, including NDC climate plans, must be approved by the cabinet, the “Federal Executive Council” chaired by the president. After all, a significant number of Nigerians believe that the government needs to do more to mitigate climate change; yet the country continues to score poorly in the “Climate Policy” category of the 2022 Environmental Performance Index (EPI).

The president is also the central figure in Nigerian climate policy. Climate action in Nigeria largely follows a top-down approach. It is coordinated by the federal government which maintains oversight over frameworks and legislation concerning climate change. All climate policies including the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) submitted to the United UNFCCC must be approved by the president-led Federal Executive Council. It is evident from his manifesto that President-elect Tinubu believes in climate change science, but like other candidates did not consider climate change a front-burner issue during the electoral process. This needs to change. After all, a considerable number of Nigerians believe the government must do more to limit climate change; however, the country continues to perform poorly on “climate policy” in the Environmental Performance Index (EPI) 2022.

President-elect Tinubu need not start from scratch. The Climate Change Act 2021 signed into law by out-going President Muhammadu Buhari is there to help the incoming government side-step the usual pitfall of political short-termism. The Act is the first stand-alone comprehensive climate change legislation in West Africa and among few in the world. The Act consolidates prior climate change policies, including the NDC, the National Climate Change Policy, national climate change programs, and the 2050 Long-Term Low Emission Vision towards fostering environmentally sustainable and transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient Nigeria.

The Climate Change Act establishes the National Council on Climate Change (NCCC) that will be chaired by the president-elect of Nigeria, with members from both the public and private sectors, to serve as secretariat for the implementation of climate change action plans. Considering the scant adoption of climate action, including adaptation frameworks and instruments, at the sub-national level and private sector in the country, it is imperative for the incoming administration to galvanize all the relevant stakeholders in the country to commit resources into combating climate change.

The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) Nigeria’s climate targets and policies as “almost sufficient,” indicating that the country’s commitments are not yet consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 degrees temperature limit but could be with moderate improvements. More strategic thinking based on science and workable solutions are required to align with the global target. Equally important are structural reforms and interventions such as targeted long-term public investments to support R&D activities, building an efficient innovation system, improving the level of education, training, and skills of the population, and building quality infrastructure to enhance the nation’s capacity to adopt low-carbon development pathways.

Climate is an important global common, making climate diplomacy a soft power in foreign policy. Tinubu intends to position Nigeria as a voice advocating for a more attentive international policy regarding climate change and how it affects Africa but has opined that Africa and Nigeria should not pay a heavy cost for environmental damage caused by nations in other continents. The historic decision at COP27 to set up a loss and damage fund for vulnerable low-and middle-income countries hit hard by climate disasters invalidated the manifesto’s assertion that Nigeria should not pay heavy costs for the environmental damage caused by nations on other continents. There is a need to revise this position and join the global community at COP28 in the UAE in December 2023 to fine-tune the loss and damage program and make it deliver for climate justice to inhabitants of the Global South, including Nigeria.

Building a low-carbon, climate-resilient Nigeria comes with heavy costs, far beyond what the country’s pressurized public finance can accommodate. To lead by example and attract much needed climate finance, it is critical for the incoming government to redirect existing and planned capital flows from traditional high to low-carbon, climate-resilient investments and infrastructures such as renewable and clean energy technologies. The government will also need to address specific market failures and institutional barriers facing private climate finance in the country, including limited proof of concept, risk-return profile and track record by incentivizing regulation to reduce risks and increase opportunities.

Last weekend’s agreement by UN countries on a convention on ocean protection (UNCLOS) is considered a historic step forward in global environmental protection – and could also bring progress for climate action. “The ship has reached the shore,” said conference president Rena Lee after a 38-hour marathon of negotiations at the end of the two-week conference.

From a climate perspective, the new agreement is relevant in several aspects:

The recently negotiated agreement on the implementation of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) creates the first opportunity to place areas in the high seas under protection and prohibit fishing or underwater mining in these zones. The high seas comprise all marine areas outside the exclusive economic zone of nations of 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers) and account for two-thirds of the ocean area and just under half of the Earth’s surface.

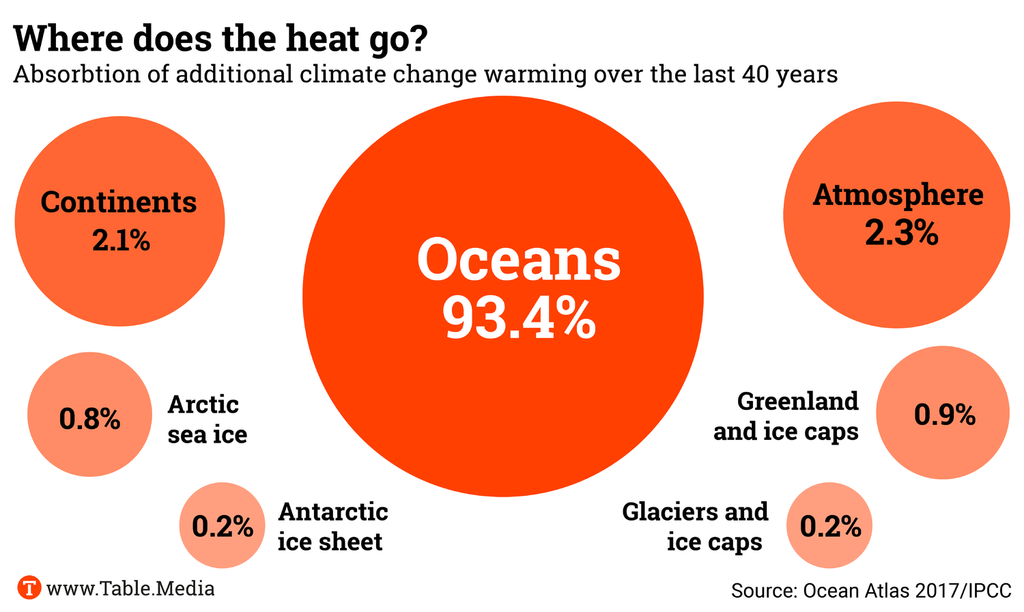

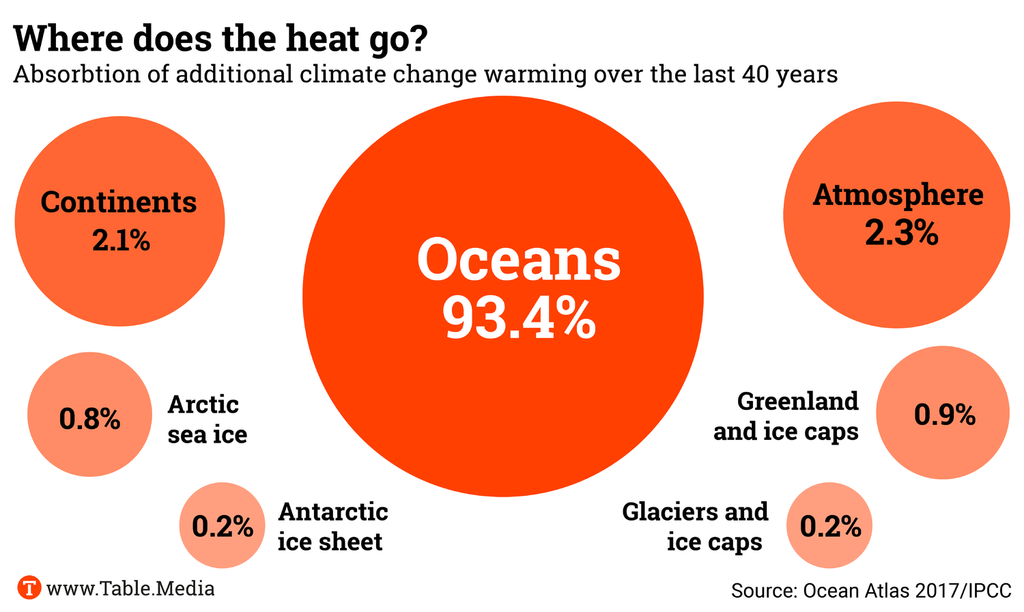

Such protected areas not only benefit biodiversity but also indirectly the climate. Because this makes the oceans more resilient as ecosystems. In the climate crisis, the oceans are warming up and absorbing more CO2, which makes them more acidic. Extensive fishing, over-fertilization near coasts and plastic waste further weaken the system. Large-scale conservation areas can reduce this pressure and strengthen the function of the oceans.

To meet the global biodiversity targets agreed upon at the biodiversity COP15 last December, protected areas covering 30 percent of the land and sea area are to be designated by 2030. This is now possible, environmental organizations praise: “This is a historic day for conservation and a sign that in a divided world, protecting nature and people can triumph over geopolitics,” says Laura Meller of Greenpeace. In climate policy, too, doubts are repeatedly being raised if multilateral policy under the umbrella of the United Nations can still produce results at all. Here, the UNCLOS agreement is a clear sign of hope.

The new agreement could also reduce emissions from fishing: Carbon emissions from long journeys to high seas areas will be eliminated if fishing is not allowed there. Emissions from bottom trawling will probably also be reduced. This involves dragging nets across the seabed, which increases the fuel consumption of fishing boats by a factor of 2.8. It also releases carbon stored in the seabed. The seabed in bottom trawling areas contains 30 percent less carbon than in undisturbed areas. The sediments in the deep sea are the world’s largest carbon sinks.

In addition, another rule of the new agreement could benefit the climate: It requires environmental impact assessments for activities that could threaten biodiversity. For example, various methods are currently being discussed to artificially accelerate the storage of carbon in the seabed, which will now probably require an assessment. The following methods are under discussion:

Environmental assessments also strengthen the position of the International Marine Authority (ISA) regarding underwater mining. Until now, the authority could not reject applications for mining licenses outright. With mandatory environmental assessments under the new agreement, the ISA can now better take environmental aspects into account.

On the one hand, this could protect the deep sea as a carbon sink and habitat for many species. On the other hand, the environmental impact assessment may also make important metals for the energy transition harder to access. The seabed is rich in metals such as manganese and cobalt in certain places.

This point is already relevant this week, even though the agreement is not yet in force. Since Tuesday, the ISA has been meeting in Kingston, Jamaica, where regulations for deep-sea mining are to be worked out.

The new UNCLOS agreement still needs to be formally adopted in a follow-up conference. It will enter into force as soon as 60 countries have ratified it. The designation of new protected areas does not require a consensus, but only a three-quarters majority of member countries. This way, a few countries cannot prevent the designation of a conservation area – an arrangement that many environmentalists would also like to see in the UN climate process.

March 8, 2023; 7.30 p.m. CET, Online

Webinar Women as Key Players in the Decentralised Renewable Energy Sector: Beneficiaries, Leaders, Innovators

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) event will focus on the role of women in the renewables sector. Although women play an important role in the energy transition, they often still face major challenges. Info

March 9, 2023; 11 a.m. CET, Online

Webinar Key findings of the EEA report – Advancing towards climate resilience in Europe

How can Europe become more resilient to the impacts of climate change? The webinar presents the key points of the European Environment Agency (EEA) report “Advancing towards climate resilience in Europe”. Info

March 9, 2023; 4 p.m. CET, Online/Augsburg

Lecture Securing Urban Climate Resilience During the Transformation Towards Carbon Neutral Cities

Professor Stephan Barthel’s research focuses on urban sustainability. In his lecture, he will talk about climate resilience in cities. Info

March 14, 2023; 1 p.m. CET

Webinar Clean hydrogen deployment in the Europe-MENA region from 2030 to 2050: A technical and socio-economic assessment

Production and import of green hydrogen from the MENA region to the EU have great potential. At the event of ENIQ Frauenhofer the study “Clean hydrogen deployment” will be presented and discussed. Info

March 13-15 2023; Dublin

Conference Global Soil Biodiversity Conference

At the 3rd Global Soil Biodiversity Conference, experts will meet to discuss the current state of the art in soil biodiversity. Info

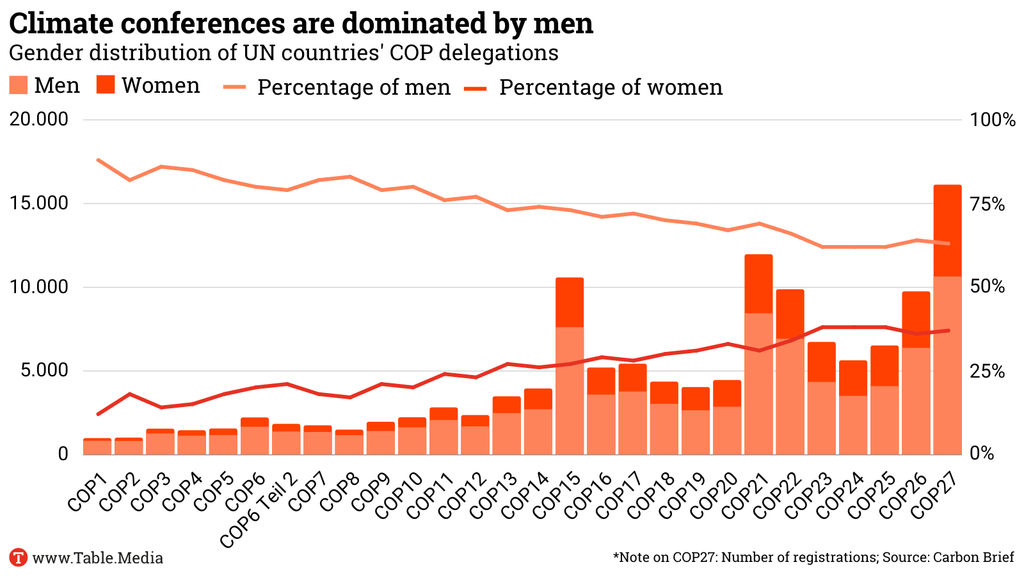

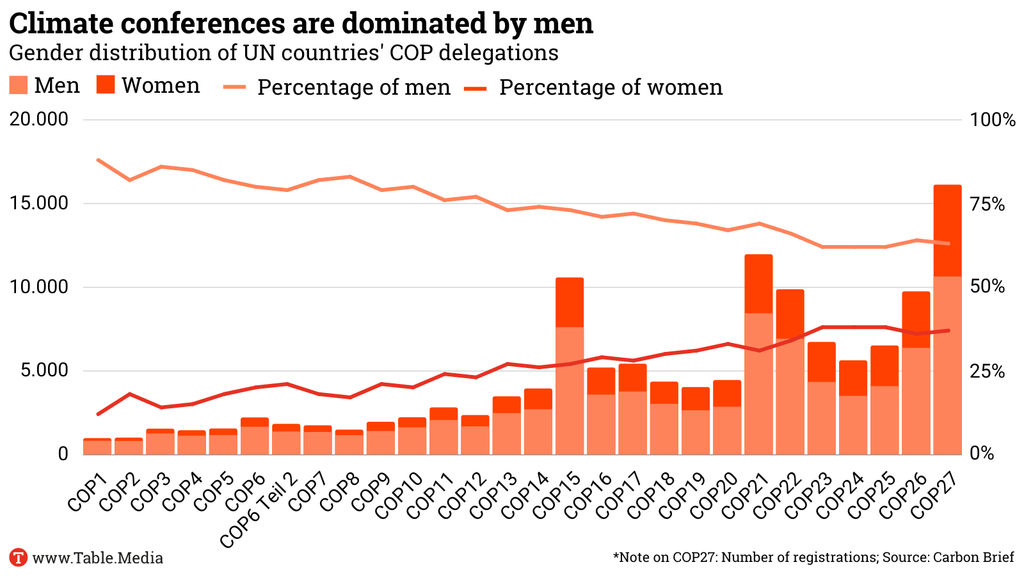

The gender gap at the UN climate conferences is closing only very slowly. The COP is still dominated by men. The delegations of the Parties at the COP27 in Sharm el Sheikh consisted of 63 percent men and only 37 percent women. At the first COP in 1995, the imbalance was even greater, at 88 to 12 percent. However, almost 30 years later, the international climate community is still far from a balance.

There are big discrepancies between countries in this respect. The German delegation had 59 women and 59 men each. For the USA, 79 women and 59 men were registered, for the EU 48 women and 70 men. For France, 67 women and 119 men. North Korea (four delegates) and Turkmenistan (five delegates) only sent men to COP27.

Yet women are often more affected by the impacts of climate change than men. Because they have less access to resources, they are less able to adapt. Moreover, if women are absent from the negotiating table and the implementation of climate action, a lot of knowledge and expertise is lost, as today’s analysis by Alexandra Endres clearly shows. nib

Gender issues are often barely mentioned in the climate plans (NDCs) submitted to the UN. This is shown by the Gender Climate Tracker of the New York Women’s Environment & Development Organization (WEDO). The number of countries that mention women’s rights or gender in their NDCs has increased slightly in recent years. But there are still large gaps:

On a positive note, the 2020 NDCs newly submitted by Grenada, Nepal, the Marshall Islands and Suriname include gender references:

The climate crisis could cost Germany up to 900 billion euros in economic damage by 2050. This is the result of a new study commissioned by the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK). Worldwide, similar calculations assume damages amounting to 23 trillion US dollars. Countries in the Global South could be particularly hard hit, as they have fewer resources to adapt.

The study on climate change costs in Germany was based in particular on economic costs. The authors of the study calculate with:

The three scenarios cannot be directly attributed to specific degrees of warming, as Alexandra Dehnhardt, Deputy Head of the Research Field Ecological Economics and Environmental Policy at the IÖW, explains. However, they do reflect “literature-supported assumptions on the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events”.

The study only considers costs that can be valued monetarily, such as:

Intangible damages caused by climate change, such as deaths, or environmental costs, like the loss of biodiversity, were not included. The study was prepared by the Institute for Ecological Economy Research (IÖW), Prognos AG and the Institute of Economic Structures Research (GWS).

The German government is currently developing an adaptation strategy and a climate adaptation law, said Christiane Rohleder, State Secretary in the Ministry of the Environment at the presentation of the study. In the long run, the federal states and municipalities would be overburdened with the costs. The goal must therefore be to anchor adaptation as a joint task in the Basic Law, Rohleder said. But spending on adaptation would be worthwhile. Even in the scenario calculation for a strong climate change, up to 60 percent of the costs could be avoided with the right adaptation strategy, according to the study. However, the results are highly uncertain.

The global economic costs of climate change are estimated in the trillions. A report by the reinsurer Swiss Re calculated costs of 23 trillion US dollars as early as 2021. By 2050, 11 to 14 percent of global economic output could be lost due to climate change. If it were possible to limit warming to less than two degrees, the losses in most countries would be less than five percent of GDP. According to a study by the consulting firm Oxford Economics, a temperature increase of 2.2 degrees by 2050 would even lead to a global GDP loss of up to 20 percent.

According to figures from the World Bank, the African Development Bank and UNEP, the countries of the Global South could suffer financial losses of 290 to 580 billion US dollars by 2030.

Without funding for loss and damage and adequate adaptation, African states alone will have to take on a trillion euros in additional debt over the next ten years, says Sabine Minninger of Bread for the World. “One can assume that many of these states will collapse without the necessary climate aid, as they will not be able to cope with the climate crisis on their own.” The international climate policy officer expects more hunger, poverty, flight and armed conflicts over dwindling resources. Yet most people in the Global South have contributed very little to the climate crisis, as the Climate Inequality Report shows.

The studies listed are not directly comparable, as they use different methodologies. Many costs that are not directly measurable or insured are partly not recorded at all. nib

The island nation of Vanuatu has made a significant step in its push to take responsibility for the impacts of climate change to court. In early March, the country announced that it had now found 105 states as supporters for its request to ask the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague for a legal assessment of responsibilities on climate change. Vanuatu thus seems to have secured a majority among the members of the UN General Assembly.

The country wants an advisory opinion to clarify what obligations all countries have in the climate crisis and how countries can be held liable for climate and environmental damage. The two-page resolution seeks clarification: “What are the obligations of states under international law to ensure the protection of the climate system and other parts of the environment from anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases for States and for present and future generations?”

In its second question to the Court, the motion asks: “What are the legal consequences under these obligations for States where they, by their acts and omissions, have caused significant harm to the climate system and other parts of the environment?” Special consideration should be given to small island states and particularly vulnerable countries, as well as future generations.

The 105 supporters include important states such as France, Germany and many other EU countries, Australia, the United Kingdom, Mexico, Vietnam, Bangladesh and many African and island states. The USA, China, South Africa, India and Brazil, for example, are not among them. An “opinion” by the ICJ is not legally binding, but could have a political effect and be used as an argument in many “climate lawsuits”.

A simple majority in the General Assembly is sufficient for a decision. At COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, more than 80 countries pledged their support for Vanuatu’s initiative (Climate.Table reported). Vanuatu has repeatedly stressed that it does not want to claim damages from the industrialized countries. The country’s Foreign Minister Jothan Napat said, “The ICJ Advisory Opinion will clarify, for all states, our obligations under a range of international laws, treaties and agreements, so that we can all do more to protect vulnerable people across the world.” bpo

The most important new body of the international climate negotiations for 2023 will begin its work at the end of March: The Transitional Committee, which is preparing the structure for the loss and damage fund, will meet for the first time from March 27-29. This has been announced by the UN Climate Change Secretariat. The meeting will be held in Egypt, the venue is yet to be announced. The group is to meet officially three times, but is also aiming for several informal meetings.

The founding of the committee was decided at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, to resolve the many unresolved questions raised by the unexpectedly adopted loss and damage fund. Among them are the decisions on how such a fund will be organized, on which criteria money will be disbursed and who will pay into it.

The committee consists of 24 members, 14 from developing and emerging countries, and 10 from industrialized countries. The appointment of the committee, which was supposed to be completed by 15 December 2022, had been repeatedly delayed. Even now, the two seats for Asian countries are still unfilled. Informally, it is said that seven countries are claiming the two places.

Such disputes have been solved by other states through joint memberships: Germany shares its seat with Ireland, other pairs are Denmark/Netherlands, Brazil/Dominican Republic, Venezuela/Barbados and Chile/Colombia. Other members of the decisive body include Egypt, South Africa, Maldives, the US, Canada, the United Arab Emirates, Australia and Sudan. bpo

The Tanzanian government has approved the construction of the long-planned East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP). Tanzania thus follows Uganda, which already approved the oil pipeline in January. The EACOP is also planned to provide an alternative to the Uganda-Kenya Crude Oil Pipeline further north. The EACOP pipeline, which is more than 1,400 kilometers long, will connect oil fields at Lake Albert in northwestern Uganda with the Tanzanian port city of Tanga on the Indian Ocean. The cost of construction is expected to be 3.5 billion dollars and will be operated by a consortium of the French commodities group Total Energies, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) together with the state-owned Uganda National Oil Company. The first oil is expected to flow as early as 2025.

Climate activists criticize the construction of the new oil pipeline. Apart from harmful climate emissions, opponents of the project also fear the destruction of critical ecosystems and the displacement of tens of thousands of people. French and Ugandan activists went to court in Paris to oppose Total Energies’ involvement. However, their hope to stop the project by a landmark ruling with reference to the new French supply chain law had been dismissed. The court argued that only a judge examining the case more in-depth could assess whether there was enough substance in the accusations against TotalEnergies. Arne Schütte

The yearly COP is the highlight of the climate calendar. Yet, as emissions continue to climb and the impacts of climate change worsen, it is time we asked what the COP process is really achieving and how it can be overhauled to ensure it helps to deliver a safe climate landing for humanity.

Research shows global emissions must come down by around 50 percent by 2030 to hold the 1.5 °C limit and continue to be cut by 50 percent every decade, to reach a net-zero world economy by 2050-2060. However, the COP process is too slow to achieve this. We are faced with a dramatic and unacceptable mismatch, confirmed by the UNEP Gap reports, between what COP needs to accomplish, and the inertia that it consolidates among the Parties.

The Paris Agreement was rightly praised for its ambition and commitment to try to keep global heating below 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. But action to turn this goal into reality advances at a glacial pace. It has taken seven years to finalize the components of the Paris Agreement – the last one being the agreement on loss and damage, which was achieved at COP27 last year.

The consensus-based COP structure is predisposed to lethargic, incremental progress, It is now time to shift gear. The current COP and Presidency leadership process will not deliver climate action at the speed required to avoid the worst impacts of global warming and create a more equal, cleaner world for all.

This need for urgent change is why I, along with a host of experts, scientists and policy leaders – including Laurence Tubiana, former Climate Change Ambassador for France and CEO of the European Climate Foundation, Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland and UN Special Envoy on Climate Change, and Ban Ki-moon, former Secretary General of the United Nations - have signed a letter calling on António Guterres and Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC Simon Stiell to reform the COP process.

In our letter, we highlight six points that could form the basis of a reform agenda for the COP process:

In this time of polycrisis, governments are understandably focused on short-term solutions, but implementing today the right levers for change, will give the world a fighting chance of averting further pandemics, wars and catastrophic global heating.

If the UN fails to put delivery at the heart of the COP summits, the world will not reduce emissions in line with the Paris Agreement and it will become harder, if not impossible, to ensure a sustainable, equitable, healthy Earth for all.

This change needs to be at the forefront of people’s minds as preparations are made for COP28 in the UAE this autumn. Leadership is needed more than ever; further delay is not an option.

Sandrine Dixson-Declève is a Belgian environmental scientist and energy policy expert. In particular, she has advised European governments and international organizations such as the OECD and the UN on climate change and clean energy issues. Since October 2018, she has co-chaired the Club of Rome with South African Mamphela Ramphele. Their position is a revised version of an open letter calling for COP reform.

Valérie Masson-Delmotte is hard to get in touch with. This is because the paleoclimatologist and research director at the national research center for nuclear energy “Commissariat for Atomic Energy and Alternative Energies” (CEA) is swamped with requests. A specialist in “past climate change,” she has already won numerous awards and was voted by Time magazine as one of the hundred most influential people of 2022.

Since her appointment as co-chair of Group I of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2015, the work of the 50-year-old scientist is a long line of television and radio broadcasts, training sessions for politicians and officials, appearances at festivals, long Twitter threads, and writing and proofreading reports and articles.

Masson-Delmotte would not have been able to do most of this if she had joined Macron’s government. The offer was on the table after Macron was re-elected in the spring of 2022, but the climate scientist turned it down. Yet she is no stranger to the political scene. Between 2008 and 2014, Masson-Delmotte served as a nonpartisan municipal councilor in her small commune of Villejust (Essonne), near Paris. However, a few months after she declined to join the government, she accepted an invitation from the Élysée in the fall of 2022 to address the French president and the entire government and brief 42 ministers and secretaries of state on climate change. A disastrous summer in France with heat waves, droughts and fires had woken up the government, after all.

She also raises awareness for the underrepresentation of women in climate science. She opened a presentation at a seminar of the French Association of Women Leaders in Higher Education, Research and Innovation (AFDESRI) in late January 2023 with a tribute to a pioneering woman in climate research.

“It is extremely important to acknowledge the fundamental contribution that women scientists have long made to understanding climate change: It was a woman, the American researcher Eunice Foote, also a feminist, who was the first scientist in the 19th century to show that increases in greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere affect air temperature and climate. She is one of those female scientists who has been sidelined and whose groundbreaking work is not adequately recognized.”

For a long time, the Irishman John Tyndall was regarded as having discovered the climate effect of CO2. It was not until 2010 that Foote’s experiments, which she had published as early as 1856 and in which she proved that CO2 is a greenhouse gas, were rediscovered.

In 2015, Masson-Delmotte was pressured by the French government to apply as co-chair of Group I for the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report. Eight years later, she admits she has reached her breaking point. Since 2015, her work has included overseeing the publication of a 2,400-page report and three special reports. She was also involved in writing the synthesis report, to be presented on March 20.

She also puts her finger in the wound at the IPCC. Only about one-third of IPCC authors are women, she says. This ratio “reflects the balance of power in the scientific community,” the researcher says. She hopes there will be female candidates for the IPCC chair next July. She will not run again. Masson-Delmotte hopes she will then have more time for tennis and her great passion, reading. She is the mother of two adult daughters who are passionate about very similar topics and focused on gender issues as well as biodiversity and ecology in their master’s studies.

Her next big project is already around the corner: A major European research project in Antarctica, Awaca, of which Masson-Delmotte is one of the main coordinators. Masson-Delmotte will not run out of work.

For International Women’s Day, our Climate.Table is published one day earlier than usual and particularly focuses on “Women and Climate“. This is not a “gender craze”, but an acknowledgment of the facts: True climate action is only possible if everyone has a say and can participate in decisions.

We, therefore, lay out what a feminist climate policy should look like. We present the ten most important women on the climate stage. We show how COPs are still male-dominated and climate plans of many countries forget women. And we feature a great scientist who is advancing feminist climate policy.

In addition, we present background information on the election and climate policy in Nigeria. We also cover signs of hope: The new UN High Seas Treaty can also benefit the climate; the decisive body on the loss and damage fund at the UN level is finally ready to work; Vanuatu will take climate change to international court.

So many reasons to read Climate.Table. And soon to hear and see, too: On March 23 at 12 p.m., I will be joined by Jennifer Morgan for a live conversation at Table.Media. With the Climate State Secretary at the German Federal Foreign Office, we want to take a look ahead to an exciting year: World Bank reform, IPCC report, Petersberg Climate Dialogue, Global Stocktake, COP28 and much more. Feel free to join us here and spread the word!

And finally: If you like the Climate.Table, please forward us. If this mail was forwarded to you: Here you can try the briefing free of charge.

The German foreign climate policy strategy, led by the Federal Foreign Office, is not yet finished. It could be presented in late March. However, one thing is already clear: It will be embedded in the guidelines for a feminist foreign policy that Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock presented to the public last week – together with Development Minister Svenja Schulze, whose ministry will also be pursuing a feminist strategy in the future.

The plans of the two ministries go beyond mere support for women. Feminist policy means changing unjust power structures, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) says. Feminist foreign policy wants to “achieve that all people enjoy the same rights,” writes the foreign minister. Societies that would strive for this would be “more peaceful, more just, more sustainable and more economically successful”.

This also has implications for foreign climate policy. Through their feminist approach, both ministers want to strengthen women’s rights, for example, the right to education; give women better access to resources from which they have so far often been excluded; and increase the representation of women in political offices or decision-making bodies. In addition, both ministries announced plans to gear their budgets more closely to feminist criteria and increase the number of women in leadership positions internally as well.

This is one reason why women – and other socially marginalized groups – should be particularly considered in climate policy: They often suffer particularly from global warming. This is illustrated by five examples from the recently published Climate Inequality Report 2023:

In this way, global warming can exacerbate existing injustices. Sheena Anderson is responsible for climate justice and climate foreign policy at the Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy (CFFP) in Berlin. She says that a climate policy that does not take this into account could push marginalized groups even further into the sidelines. A feminist policy aims to avoid this.

According to the CFFP, an international climate policy that takes gender aspects into account can accelerate the transition to a climate-friendly society. It benefits everyone – and it also fulfills obligations under international agreements, for example within the UNFCCC.

“Without feminism, there can be no climate justice,” says Anderson. “The climate crisis hits marginalized people particularly hard. Feminism means including them in particular in the search for solutions.” In this way, she says, previously unappreciated knowledge can be tapped.

The BMZ also points out in its guidelines that “indigenous knowledge, for example, is still not adequately included in solutions to the climate crisis”. The reason is “the devaluation of knowledge and education systems in the course of colonialism” – part of the unjust power structures that feminist policies are set to change.

A BMZ spokeswoman told Climate.Table that women’s knowledge “must be used in agriculture, natural resource management and energy use”. For this reason, the BMZ wants to “specifically promote women and involve them equally” in projects in partner countries.

Then climate would become more successful: For example, in Zambia, where women have been specially trained to improve the local water supply; in Nepal, where women have organized themselves and thus fought for the right to own land; or in the Global Shield against Climate Risks, in which the ministry has committed itself to a strong role for women. So far, however, the spokeswoman admits, “it is mainly men who make the decisions in most partner countries. It’s a matter of changing existing power structures and making women visible.”

CFFP expert Sheena Anderson gives five examples of how feminist approaches could make climate policy more equitable:

According to the CFFP, feminist policies that seek to address all dimensions of disadvantage must consider many factors. Among them:

Gina Cortés says: A truly feminist climate policy must be developed from the regions, together with the people who live there. Cortés, a Colombian national, is gender and climate policy manager for Women Engage for a Common Future (WECF), an organization that works with other civil society organizations to contribute to the UNFCCC process. Together with Bridget Burns, director of the New York-based global women’s rights organization WEDO, Cortés is the official focal point for the UNFCCC’s Women’s and Gender Constituency (WGC).

“Climate change affects all of us differently, depending on gender, class, ethnicity and skin color,” Cortés says. “That’s why there is not one feminism. It’s different in Asia than in Latin America or Africa.” That’s why feminist climate policies need to take regional specificities into account, she says.

For Cortés, feminist politics is a response to the existing capitalist, extractivist, neocolonial economic model. A feminist climate policy means overcoming this model rather than repeating it under climate-friendly auspices, she says. This would include, for example, debt relief.

“Feminist climate politics must be decolonizing, anti-racist and intersectional. Otherwise, it won’t work,” Cortés says. “We have to begin to understand that there are other ways to live well than within the existing model”: for example, based on a solidarity-based, ecological economy that strengthens interpersonal relationships and leaves room for spirituality.

“A different world is possible,” Cortés says. But instead, she sees the danger that instead of coal, Europe will import renewable energy from countries like Colombia in the future – and will also show no consideration for the local indigenous population, just to maintain its own standard of living. She asks, “Currently, Germany has even increased coal imports from Colombia. How does that fit with feminist development and foreign policy?”

On June 1, Spain will take over the EU Council Presidency. This means that one of the “best experts in international climate negotiations” will lead the EU to COP28. Spain’s Minister for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge was already part of negotiations as Secretary of State for Climate Change (2008-2011) prior to the failed Copenhagen Conference in 2009. A lawyer, she held various positions in the Spanish Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Environment (1996-2004) before becoming Director General for Climate Affairs (2004-2008). From 2014 to 2018, Ribera headed the Paris-based think tank IDDRI before moving back to the Socialist government in Madrid. Ribera’s negotiating style is considered open, communicative, and tough on issues.

Campaigning for the environment and justice can be dangerous: That is what Syeda Rizwana Hasan experienced at the end of January when she and her team were attacked in southern Bangladesh and stones were thrown at their vehicles. She was on-site to assess a controversial construction project. Internationally, Hasan has chosen law, not climate diplomacy, to help push back against greenhouse gas emissions: The 55-year-old is a lawyer at the Bangladesh High Court and Chair of the board of the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA). Among other things, she campaigned against the construction of coal-fired power plants near the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest. Her goal: Using the sharpest legal sword to fight climate change offenders – international criminal law. In 2009, she was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for her commitment.

Her appearance in defense of island nations already left a lasting impression at the World Climate Change Conference in Glasgow at the end of 2021. On stage in Sharm El-Sheikh, at the UN General Assembly and in many international forums, Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados and former lawyer, is now a powerful voice: The Caribbean politician fought for better access to international funding for countries in the Global South and financial compensation from major emitters in climate change. “If I pollute your property, you expect me to compensate you,” she said. But Mottley has sparked much more than just a demand for more money: Her Bridgetown Initiative aims to create an international alliance to put major financial players like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and the development banks on a climate track: No more funding for fossil fuels, more money and justice for victims of climate change, swift aid when disasters strike. Mottley wants to move the big levers.

The State Secretary and Special Envoy for International Climate Action in the German Foreign Ministry is a real insider on the international climate stage. No wonder: She has always been there since the start of COPs. Before changing roles to official climate policy, the political scientist and German studies graduate worked for WWF, E3G, the climate protection group CAN, the Potsdam Institute PIK and the World Resources Institute, among others. In 2016, she became head of Greenpeace International – here, too, she benefited from a large network of acquaintances and informal encounters as well as speaking frankly. Even as an activist, Morgan always had an open ear for opposite positions, and was more a diplomat than a radical. Morgan was born in the United States and has lived in Germany since 2003, before becoming a German citizen in 2021 in time for her appointment as Secretary of State.

The 20-year-old is the world’s best-known climate campaigner. It all began in 2018 when, at the age of 15, she started her “school strike for the climate” in front of the Swedish parliament to urge the government to meet its climate targets. Her small campaign inspired thousands of young people around the world to organize their own protests – and also generated a lot of hate for her around the world. By December 2018, more than 20,000 students – from the UK to Japan – had joined her protest and played hooky from school. A year later, she received the first of three nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize for her climate activism. In 2019, Thunberg sailed across the Atlantic on a yacht to attend a UN climate conference in New York. Enraged, she accused world leaders of not doing enough. “You all come to us young people for hope. How dare you. You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words,” she said.

The Ugandan Fridays for Future activist gained worldwide attention in 2020 because she was supposed to remain unknown: A news photo showing her alongside Greta Thunberg and other white climate activists was cropped to remove Nakate. Her reaction that the news agency had “not just deleted a photo, but a continent” made international headlines. Since then, the 26-year-old business economist, whose father was chair of the Rotary Club in Uganda’s capital Kampala, has been regarded as Africa’s voice for climate justice. The French-speaking daily Jeune Afrique named her one of the 100 most influential Africans in 2020. She founded the Rise Up Movement to make the voices of African climate activists heard, as well as a project to install solar panels in rural schools in Uganda. Vanessa Nakate is also the author of A Bigger Picture, a manifesto for inclusive climate action.

Since 2014, Sharan Burrow has been a member of the Global Commission for the Economy and Climate, co-chaired by Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Nicholas Stern and Paul Polman. But it is above all in her role as General Secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) since 2010 that she has made a name for herself on women, climate and workers’ rights. In the hallways of international climate conferences, the Australian with the distinctive voice and prickly humor emphasizes that global warming primarily affects the poorest. There is no getting around climate justice, is her credo. And if the preamble to the Paris Agreement notes climate justice as the “importance of ensuring the integrity of all ecosystems, including oceans, and the protection of biodiversity”, Sharan Burrow has done her part.

The director of the Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) describes herself as a feminist and environmental activist. An American national, she leads a global organization at the intersections of gender equality and environmental justice. For more than a decade, Burns has focused on advancing gender equality in climate policy at the global and national levels. Her work has involved organizing support and building capacity for women from the Global South to participate as part of their national delegations to UNFCCC conferences and intersessions through WEDO’s flagship Women Delegates Fund program.

What if we approached the climate crisis differently? In order to take action, we should not bury our heads in the sand, but display a healthy mix of outrage and confidence to take big leaps. This is the combination perfectly illustrated by the name of the podcast co-hosted by Costa Rican diplomat Christiana Figueres: “Outrage and Optimism”. A figurehead in the fight against climate change, the former Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC (2010-2016) – along with Laurence Tubiana – is widely credited with the success of the Paris Agreement in December 2015. The Costa Rican, who has worked across the public, private and non-profit sectors, was the first woman to hold the post and the first representative of the Global South. She comes from Costa Rica’s best-known political dynasty – both her father and brother were presidents of the country.

During COP21, Laurence Tubiana was one of the most important individuals. Together with Christiana Figueres, she is considered one of the architects of the Paris Agreement. No COP plenary, no bilateral meeting of the then French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius without his ambassador for climate negotiations. Due to a serious horse riding accident, she only wore sneakers to the conference – in a different color every day. Until COP21, she had headed the Paris-based think tank IDDRI, where she advocated decarbonization – the departure from the carbon-fuelled economy that was ultimately enshrined in the Paris Agreement. She currently heads the European Climate Foundation as director and is thus still present on the climate stage – as someone who networks herself and others, and gives ideas and drives policy.

The ruling All Progressives Congress candidate, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, has emerged as winner of the keenly contested Nigeria’s presidential election held on Saturday, February 25, 2023. President-elect Tinubu, Nigeria’s fifth president since the end of the military rule in 2009, was declared winner by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) after polling a total of 8.79 million votes, representing 35.2 percent of votes cast. He has his work cut out for him: He must revive an ailing economy, create jobs, reduce multidimensional poverty, tame inflation, battle widespread insecurity and entrench equity, fairness and justice to unite a polarized nation, and deal with the consequences of the climate crisis.

Socio-political and economic reforms around these multifaceted challenges headlined campaigns towards the recently concluded presidential election. Climate change was relatively muted in the candidates’ manifestos, though Nigeria suffers the deleterious effects of climate change. Adverse climate change subverts the country’s development and threatens the livelihoods of millions of Nigerians. Nigeria is the 53rd most climate-vulnerable country and the 6th least-ready country in the world to adapt to climate change.

Tinubu’s Renewed Hope 2023 manifesto situated climate change issues as one of the key challenges facing Nigeria’s agricultural sector. As countermeasures, Tinubu aims to increase agricultural productivity and complete the Great Green Wall. This is Africa’s flagship initiative of forest plantations to combat climate change and desertification and address food insecurity and poverty.

At the same time, Tinubu’s manifesto emphasizes increasing crude oil production to four million barrels a day by 2030 and increasing gas production by 20 percent. The oil sector is the primary source of government revenue in Nigeria, with roughly 25.55 billion US dollars in 2022, but the sector’s contribution to the country’s GDP is minuscule, just 4.34 percent of the country’s total real GDP in Q4 2022.

The primary energy sources in Nigeria are renewables and crude oil with shares of 47 percent and 41 percent respectively. Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan is to meet 57 percent of its energy demand using renewables by 2050 with crude oil declining to 33 percent. Tinubu’s renewable energy plan is based on Nigeria’s commitment to carbon neutrality by 2060 and aims to promote solar energy through grid connection and mini-grids.

The president is also the central figure in Nigerian climate policy. Climate measures are largely coordinated by the federal government. All climate policies, including NDC climate plans, must be approved by the cabinet, the “Federal Executive Council” chaired by the president. After all, a significant number of Nigerians believe that the government needs to do more to mitigate climate change; yet the country continues to score poorly in the “Climate Policy” category of the 2022 Environmental Performance Index (EPI).

The president is also the central figure in Nigerian climate policy. Climate action in Nigeria largely follows a top-down approach. It is coordinated by the federal government which maintains oversight over frameworks and legislation concerning climate change. All climate policies including the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) submitted to the United UNFCCC must be approved by the president-led Federal Executive Council. It is evident from his manifesto that President-elect Tinubu believes in climate change science, but like other candidates did not consider climate change a front-burner issue during the electoral process. This needs to change. After all, a considerable number of Nigerians believe the government must do more to limit climate change; however, the country continues to perform poorly on “climate policy” in the Environmental Performance Index (EPI) 2022.

President-elect Tinubu need not start from scratch. The Climate Change Act 2021 signed into law by out-going President Muhammadu Buhari is there to help the incoming government side-step the usual pitfall of political short-termism. The Act is the first stand-alone comprehensive climate change legislation in West Africa and among few in the world. The Act consolidates prior climate change policies, including the NDC, the National Climate Change Policy, national climate change programs, and the 2050 Long-Term Low Emission Vision towards fostering environmentally sustainable and transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient Nigeria.

The Climate Change Act establishes the National Council on Climate Change (NCCC) that will be chaired by the president-elect of Nigeria, with members from both the public and private sectors, to serve as secretariat for the implementation of climate change action plans. Considering the scant adoption of climate action, including adaptation frameworks and instruments, at the sub-national level and private sector in the country, it is imperative for the incoming administration to galvanize all the relevant stakeholders in the country to commit resources into combating climate change.

The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) Nigeria’s climate targets and policies as “almost sufficient,” indicating that the country’s commitments are not yet consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 degrees temperature limit but could be with moderate improvements. More strategic thinking based on science and workable solutions are required to align with the global target. Equally important are structural reforms and interventions such as targeted long-term public investments to support R&D activities, building an efficient innovation system, improving the level of education, training, and skills of the population, and building quality infrastructure to enhance the nation’s capacity to adopt low-carbon development pathways.

Climate is an important global common, making climate diplomacy a soft power in foreign policy. Tinubu intends to position Nigeria as a voice advocating for a more attentive international policy regarding climate change and how it affects Africa but has opined that Africa and Nigeria should not pay a heavy cost for environmental damage caused by nations in other continents. The historic decision at COP27 to set up a loss and damage fund for vulnerable low-and middle-income countries hit hard by climate disasters invalidated the manifesto’s assertion that Nigeria should not pay heavy costs for the environmental damage caused by nations on other continents. There is a need to revise this position and join the global community at COP28 in the UAE in December 2023 to fine-tune the loss and damage program and make it deliver for climate justice to inhabitants of the Global South, including Nigeria.

Building a low-carbon, climate-resilient Nigeria comes with heavy costs, far beyond what the country’s pressurized public finance can accommodate. To lead by example and attract much needed climate finance, it is critical for the incoming government to redirect existing and planned capital flows from traditional high to low-carbon, climate-resilient investments and infrastructures such as renewable and clean energy technologies. The government will also need to address specific market failures and institutional barriers facing private climate finance in the country, including limited proof of concept, risk-return profile and track record by incentivizing regulation to reduce risks and increase opportunities.

Last weekend’s agreement by UN countries on a convention on ocean protection (UNCLOS) is considered a historic step forward in global environmental protection – and could also bring progress for climate action. “The ship has reached the shore,” said conference president Rena Lee after a 38-hour marathon of negotiations at the end of the two-week conference.

From a climate perspective, the new agreement is relevant in several aspects:

The recently negotiated agreement on the implementation of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) creates the first opportunity to place areas in the high seas under protection and prohibit fishing or underwater mining in these zones. The high seas comprise all marine areas outside the exclusive economic zone of nations of 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers) and account for two-thirds of the ocean area and just under half of the Earth’s surface.

Such protected areas not only benefit biodiversity but also indirectly the climate. Because this makes the oceans more resilient as ecosystems. In the climate crisis, the oceans are warming up and absorbing more CO2, which makes them more acidic. Extensive fishing, over-fertilization near coasts and plastic waste further weaken the system. Large-scale conservation areas can reduce this pressure and strengthen the function of the oceans.

To meet the global biodiversity targets agreed upon at the biodiversity COP15 last December, protected areas covering 30 percent of the land and sea area are to be designated by 2030. This is now possible, environmental organizations praise: “This is a historic day for conservation and a sign that in a divided world, protecting nature and people can triumph over geopolitics,” says Laura Meller of Greenpeace. In climate policy, too, doubts are repeatedly being raised if multilateral policy under the umbrella of the United Nations can still produce results at all. Here, the UNCLOS agreement is a clear sign of hope.

The new agreement could also reduce emissions from fishing: Carbon emissions from long journeys to high seas areas will be eliminated if fishing is not allowed there. Emissions from bottom trawling will probably also be reduced. This involves dragging nets across the seabed, which increases the fuel consumption of fishing boats by a factor of 2.8. It also releases carbon stored in the seabed. The seabed in bottom trawling areas contains 30 percent less carbon than in undisturbed areas. The sediments in the deep sea are the world’s largest carbon sinks.

In addition, another rule of the new agreement could benefit the climate: It requires environmental impact assessments for activities that could threaten biodiversity. For example, various methods are currently being discussed to artificially accelerate the storage of carbon in the seabed, which will now probably require an assessment. The following methods are under discussion:

Environmental assessments also strengthen the position of the International Marine Authority (ISA) regarding underwater mining. Until now, the authority could not reject applications for mining licenses outright. With mandatory environmental assessments under the new agreement, the ISA can now better take environmental aspects into account.

On the one hand, this could protect the deep sea as a carbon sink and habitat for many species. On the other hand, the environmental impact assessment may also make important metals for the energy transition harder to access. The seabed is rich in metals such as manganese and cobalt in certain places.

This point is already relevant this week, even though the agreement is not yet in force. Since Tuesday, the ISA has been meeting in Kingston, Jamaica, where regulations for deep-sea mining are to be worked out.

The new UNCLOS agreement still needs to be formally adopted in a follow-up conference. It will enter into force as soon as 60 countries have ratified it. The designation of new protected areas does not require a consensus, but only a three-quarters majority of member countries. This way, a few countries cannot prevent the designation of a conservation area – an arrangement that many environmentalists would also like to see in the UN climate process.

March 8, 2023; 7.30 p.m. CET, Online

Webinar Women as Key Players in the Decentralised Renewable Energy Sector: Beneficiaries, Leaders, Innovators

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) event will focus on the role of women in the renewables sector. Although women play an important role in the energy transition, they often still face major challenges. Info

March 9, 2023; 11 a.m. CET, Online

Webinar Key findings of the EEA report – Advancing towards climate resilience in Europe

How can Europe become more resilient to the impacts of climate change? The webinar presents the key points of the European Environment Agency (EEA) report “Advancing towards climate resilience in Europe”. Info

March 9, 2023; 4 p.m. CET, Online/Augsburg

Lecture Securing Urban Climate Resilience During the Transformation Towards Carbon Neutral Cities

Professor Stephan Barthel’s research focuses on urban sustainability. In his lecture, he will talk about climate resilience in cities. Info

March 14, 2023; 1 p.m. CET

Webinar Clean hydrogen deployment in the Europe-MENA region from 2030 to 2050: A technical and socio-economic assessment

Production and import of green hydrogen from the MENA region to the EU have great potential. At the event of ENIQ Frauenhofer the study “Clean hydrogen deployment” will be presented and discussed. Info

March 13-15 2023; Dublin

Conference Global Soil Biodiversity Conference

At the 3rd Global Soil Biodiversity Conference, experts will meet to discuss the current state of the art in soil biodiversity. Info

The gender gap at the UN climate conferences is closing only very slowly. The COP is still dominated by men. The delegations of the Parties at the COP27 in Sharm el Sheikh consisted of 63 percent men and only 37 percent women. At the first COP in 1995, the imbalance was even greater, at 88 to 12 percent. However, almost 30 years later, the international climate community is still far from a balance.

There are big discrepancies between countries in this respect. The German delegation had 59 women and 59 men each. For the USA, 79 women and 59 men were registered, for the EU 48 women and 70 men. For France, 67 women and 119 men. North Korea (four delegates) and Turkmenistan (five delegates) only sent men to COP27.

Yet women are often more affected by the impacts of climate change than men. Because they have less access to resources, they are less able to adapt. Moreover, if women are absent from the negotiating table and the implementation of climate action, a lot of knowledge and expertise is lost, as today’s analysis by Alexandra Endres clearly shows. nib

Gender issues are often barely mentioned in the climate plans (NDCs) submitted to the UN. This is shown by the Gender Climate Tracker of the New York Women’s Environment & Development Organization (WEDO). The number of countries that mention women’s rights or gender in their NDCs has increased slightly in recent years. But there are still large gaps:

On a positive note, the 2020 NDCs newly submitted by Grenada, Nepal, the Marshall Islands and Suriname include gender references:

The climate crisis could cost Germany up to 900 billion euros in economic damage by 2050. This is the result of a new study commissioned by the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK). Worldwide, similar calculations assume damages amounting to 23 trillion US dollars. Countries in the Global South could be particularly hard hit, as they have fewer resources to adapt.

The study on climate change costs in Germany was based in particular on economic costs. The authors of the study calculate with:

The three scenarios cannot be directly attributed to specific degrees of warming, as Alexandra Dehnhardt, Deputy Head of the Research Field Ecological Economics and Environmental Policy at the IÖW, explains. However, they do reflect “literature-supported assumptions on the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events”.

The study only considers costs that can be valued monetarily, such as:

Intangible damages caused by climate change, such as deaths, or environmental costs, like the loss of biodiversity, were not included. The study was prepared by the Institute for Ecological Economy Research (IÖW), Prognos AG and the Institute of Economic Structures Research (GWS).

The German government is currently developing an adaptation strategy and a climate adaptation law, said Christiane Rohleder, State Secretary in the Ministry of the Environment at the presentation of the study. In the long run, the federal states and municipalities would be overburdened with the costs. The goal must therefore be to anchor adaptation as a joint task in the Basic Law, Rohleder said. But spending on adaptation would be worthwhile. Even in the scenario calculation for a strong climate change, up to 60 percent of the costs could be avoided with the right adaptation strategy, according to the study. However, the results are highly uncertain.