Did you also toast 2023 wearing a T-shirt and shorts in spring-like temperatures? It was the warmest New Year since record-keeping began. And probably a harbinger of what we can expect to see in 2023 and beyond.

In this Climate.Table, we, therefore, take a look at what the new year holds in store: We explain, among other things, the hottest trends in global climate policy and the tasks that await the EU in the process. We describe the Swedish EU presidency’s balancing act between climate action in Brussels and climate change deniers at home in Stockholm. We look at Brazil’s old and new environment minister and her fight to preserve the Amazon rainforest. And we introduce the idea of establishing a global “climate parliament” alongside the annual COPs.

However, one should be careful with concrete predictions. If 2022 has taught us one thing, it is that there is little guarantee that things will happen as we think they will. The only thing certain is uncertainty. Especially in the climate crisis. All the more reason for us to explain in greater detail what is happening where, how and why. We look forward to having you with us and wish you a healthy new year.

It was already clear in 2022: The long-term warming of the atmosphere manifests itself more and more violently even in the short-term weather. With emissions and CO2 levels in the atmosphere at a new high, temperatures climbed again in 2022, as they had in the previous eight years – to an average of 1.15 degrees Celsius above the long-term global average and new all-time highs in some regions. And all this after three years marked by an exceptionally long “La Niña” phenomenon – the temperature anomaly in the Pacific Ocean that normally provides for global cooling. Meteorologists now expect this cooling trend to end in 2023 – and, in all probability, the start of an “El Niño” period that could drive global temperatures even higher.

The end of Russian gas supplies to Europe and global uncertainty have thrown markets into severe turmoil. High gas prices make renewables competitive worldwide – but also bring back coal. A warm winter in Europe could lower demand and prices. But lower prices could also drive consumption and emissions back up. In any case, future emissions will also be determined by how this year’s decisions are made on new gas drilling, for example, in Africa, LNG terminals in Europe, or more coal in Southeast Asia. Experts warn that the new interest in gas could make the Paris climate targets impossible.

In 2022, global carbon emissions have risen once again, by just under one percent. Will the peak finally be reached in 2023? That could be possible if renewables continue to grow as strongly as they currently are, the global economy weakens due to the Chinese Covid problems, and efficiency and saving are worthwhile while prices are high. But it may still take time – ideally, the IEA does not expect the peak until 2025 – and as a result a 2.5 degree Celsius rise in global temperature in 2100. In contrast, to meet the 1.5 limit, emissions would have to drop rapidly from 2025 onward.

The massive tax cuts in the USA through the IRA investment program should make renewables affordable enough that green hydrogen will be cheaper to produce there than with fossil fuels as early as 2025. In the US, this could “in time” make green hydrogen as cheap as previously predicted for 2050, analyzes economist Veronika Grimm – with the effect that the US could have major advantages for electrolyzer sites. This, in turn, could lead to an increase in European subsidies for the establishment of green hydrogen industries, making development much faster than expected here as well.

The third goal of the Paris Agreement, to coordinate financial flows toward climate action, will move into sharper focus this year: At the spring meeting of the World Bank and IMF in Washington in April, influential countries want to push for a reform of global financial institutions. The “Bridgetown Initiative,” presented by Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados and supported by many countries, is intended to better protect emerging and developing countries against climate shocks with the help of the World Bank and development banks. In addition to loans of one trillion dollars, this also includes 100 billion dollars from special drawing rights at the IMF, which are to be regarded as favorable financing for the poor states. However, the German Federal Bank and the European Central Bank are putting the brakes on this.

The big success of COP27 was the decision to set up a fund to finance climate loss and damage. However, the important details were left blank: Who pays how much, who gets the money, and what do applications and projects look like? All these questions are to be clarified by a “transition committee” with 24 representatives (10 from industrialized countries, and 14 from developing countries). During 2023, this committee will define the important details, which will then be decided at the COP28 at the end of the year. However, only five seats had been filled by the deadline of December 15, 2022.

As this year’s G20 presidency, India also wants to make its mark in climate policy – on the one hand with benefits for poor countries and with sharp demands for more money and know-how from the Global North. The focus will be on financial issues, but also on lifestyles and securing sustainability goals. At the same time, however, the Indian government is also talking with industrialized countries, as it has already done with South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam, about a partnership for a just energy transition (JETP). So far, these talks have failed because India is unwilling to negotiate a coal phase-out, which, however, is crucial for the industrialized countries.

At COP27, it was unclear how serious India was about a global push for a resolution to “reduce all fossil fuels” that did not make it into the final declaration. The EU did not pick up the ball, which might have partially broken the G77 group from its ties to China. Other developing countries also openly criticized China’s role for the first time. This shows that a new “High Ambition Coalition” (HAC) of progressive industrialized, emerging and developing countries might be possible – which once again came together at the end of COP27 after initial difficulties. The process for the Biodiversity Convention could serve as a model. At COP15 in Montreal in December, it was decided that the HAC on biodiversity should have its own permanent secretariat.

The election victory of Brazil’s new President Luis Inacio Lula da Silva, the inauguration of Environment Minister-designate Marina Silva, and the revival of the Amazon Fund by the industrialized countries give a reason for hope: Can Brazil’s new president make good on his promise to stop deforestation in the Amazon by 2030? And: What can be expected from the global alliance of rainforest countries comprising Brazil, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo as the “Rainforest OPEC”?

In December it will become clear in Dubai whether and how seriously the UN countries are taking their Paris pledges: Then the “Global Stocktake” will officially show whether the climate plans (NDC) of the countries meet the requirements of science regarding their targets and measures to keep the 2 or 1.5 limit. The answer from this global stocktaking of climate action is already clear: That has failed. It is doubtful whether the countries at COP28 in Dubai will decide collectively and bindingly to do more on avoidance and adaptation – and then also define this in detail for themselves.

Even if many environmental organizations hate to hear it: The controversial permanent storage and use of CO2 (CCS, CCUS), for example under the seabed, gains an increasing importance. The German government plans to present an official CCS strategy in 2023. In Europe, Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands are pressing ahead with this project at full speed with their own bids for CO2 final storage facilities. A large market for this service is emerging worldwide, capturing carbon dioxide mainly from industrial operations in the steel, glass or cement sectors and storing it in decommissioned gas storage facilities, for example.

Whether conflicts, pandemics, economic recessions or new inventions: 2023 will also hold surprises for climate policy: How will the Covid situation in China affect the global economy? What will be the further impact of Russia’s war in Ukraine? What would be the consequences of a power vacuum in Iran for the global oil market? What progress will ambitious climate policies in the climate heavyweights EU, USA, Australia or Brazil bring? Even in 2023, only one thing is certain: uncertainty.

It will be a frosty welcome for the EU Commission: To mark the start of the Swedish Council Presidency, the government of Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson will receive the entire Commission in the town of Kiruna in the far north on January 12 and 13. This is where Europe’s largest iron ore deposits are located. And here, thanks to stricter EU climate legislation, a gigantic industrial transformation is taking place driven by climate policy.

However, it is still unclear how frosty relations between the new Swedish government and the EU will become on climate policy. “Green & energy transitions” is one of four top priorities for Sweden’s presidency of the Council of the European Union, which started on Jan 1st. . This choice of focus somewhat deviates from the new government’s own domestic agenda, where

During its half-year term, Sweden is likely to bring already tabled climate dossiers forward, but new initiatives are hardly to be expected, maybe except for nuclear power.

The three-party minority government, that took power after the Swedish elections in September 2022, consists of prime minister Ulf Kristersson´s right-wing Moderates (M), the Christian Democrats (KD) and the Liberals (L). As these three only control 103 seats in the Riksdag, fewer than the opposition Social Democrats can muster alone, Kristersson´s government in more or less every vote, is dependent on the active support from the right-populist Sweden Democrats (SD). The latter gained over 20 percent in the September election and form the second-largest parliamentary group.

Infamous for its roots in neo-nazi, xenophobic groupings, SD has, until its recent growth, been politically isolated. Now, this has changed, and its rising influence is mirrored in the new government’s very restrictive immigration policies. On top, SD is also the most powerful critic of Sweden’s traditionally ambitious climate policy. Some of its new MPs are openly climate skeptics, and when the European Parliament adopted the European Climate Law in June 2021, SD’s three MEPs were among the few that voted against it.

In order to win the parliamentary support of the SD, the Moderates and the Christian Democrats gradually distanced themselves before the election from climate and energy policy decisions that they had supported until recently. For example, the new government has promised to dismantle the mandatory blending of transport fuels with renewables. By combining this with lower fuel taxes SD, M and KD, separately, promised the voters to lower fuel prices by 0,5-1 euro per liter if gaining power – promises that probably were crucial for the outcome of the election.

In the energy sector, the rapid expansion of Swedish wind power is likely to be slowed down as the government wants to eliminate some subsidies. It blames the current high electricity prices on the decommissioning of four nuclear reactors between 2015 and 2020 and now wants the remaining fleet of six reactors to be supplemented by new, probably smaller SMR (Small Modular Reactor). To do so, it promises generous loans in particular, but interest from investors appears mixed. The industry welcomes new power capacity. But while new capacity is being added day by day through wind power, potential new nuclear plants will not come online until the mid-2030s.

In the far north of Sweden, however, where the EU Commission will be visiting, the green transformation is already clearly visible. State-owned mining giant LKAB intends to invest some 40 billion euros, partly in expanding the mine, but primarily in new advanced processing methods, based on hydrogen, made from water and electricity from existing, nearby hydro plants, and a hastily expanding number of wind turbines. Two new hydrogen-based steel mills and a giant battery factory are already under construction in Luleå, Boden and Skellefteå, all close to the Gulf of Bothnia in the Baltic Sea. This re-industrialization, a central part of the former Social-democratic government’s national narrative on the green transition as a tool for re-industrialization and economic growth, will now be taken forward by the new government

The Council presidency might, paradoxically, come as a relief to the more environmentally concerned parts of the government base – including Romina Pourmokhtari, the new, liberal minister of climate and energy. As Council Presidency, Sweden will have to seek compromises and be less able to promote its own positions, which are sometimes less ambitious than mainstream EU policy. These include:

Finally, the government is likely to push for a speedy handling of the expected proposal on stricter CO2 requirements on heavy-duty vehicles. That is because two of the world’s largest truck manufacturers, Volvo and Scania, both of which are strongly committed to the electrification of road transport, are based in Sweden. By Magnus Nielsson from Stockholm

“We need a European John Kerry,” said Peter Liese, environmental spokesman for the EPP, after the end of COP27. Frans Timmermans is overburdened in his role as climate commissioner because he is responsible for both EU legislation and international climate policy, according to Liese. In Sharm el-Sheikh, he said, the bridges were built by others, meaning US climate envoy John Kerry and his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua. Timmermans had no time for any diplomatic COP preparations because he was busy with EU legislation, the MEP accuses him.

In Sharm el-Sheikh, the EU failed to push through its demands for more climate protection through global emissions reductions. Above all, it lacked backing in the global South. An EU climate czar could build and maintain long-term alliances with island states and smaller developing countries on a full-time basis. Michael Bloss, a Green MEP in the EU Parliament, said such climate partnerships are the solution for higher international climate targets.

This opens the debate on an “EU Climate Czar.” But there are difficult questions of detail:

An EU climate czar is not a new demand. After the failed COP in Copenhagen, there had been talks that the first EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Catherine Ashton, would also be responsible for foreign climate policy, says Runge-Metzger. But the new Commission structure created the position of EU climate commissioner. The debate flared up briefly under Jean-Claude Juncker but was quickly put to rest, Runge-Metzger says.

The climate commissioner himself sees no need for a new position. He is responsible for implementing EU legislation as well as promoting international climate protection measures, according to his office. Separating the two roles would be counterproductive. Runge-Metzger agrees. In international negotiations, Timmermans would benefit from his practical experience with the Green Deal.

A climate commissioner appointed during this legislative term is considered unrealistic anyway. However, the debate could come up again for the 2024 European elections – especially in the EU Parliament. There, the EPP had already achieved a majority in the Development Committee in September last year for the creation of a budget for an EU climate envoy.

In terms of profile, a climate envoy should already have experience in climate negotiations, know the structures of climate conferences and have a certain standing in the scene, says Liese.

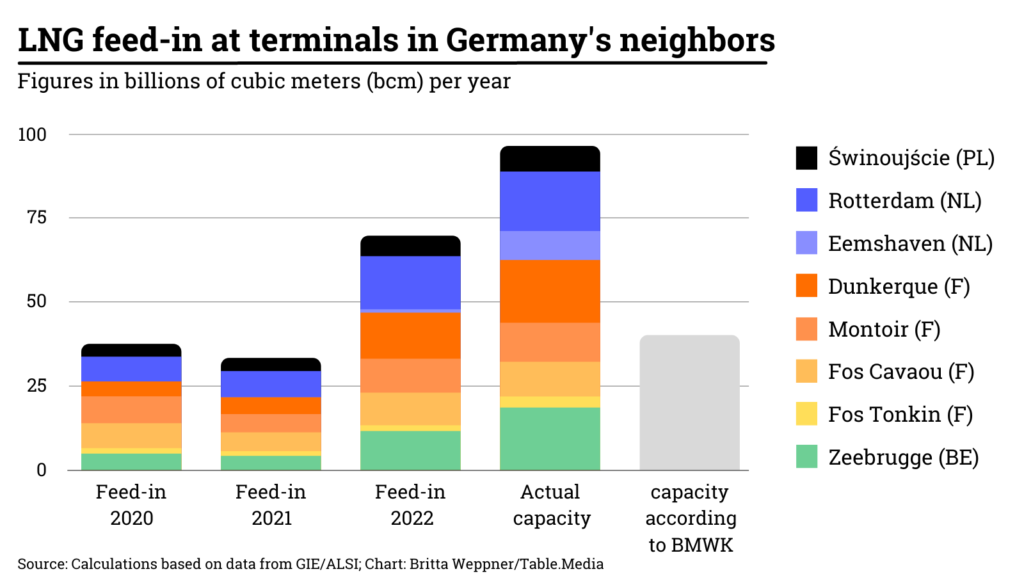

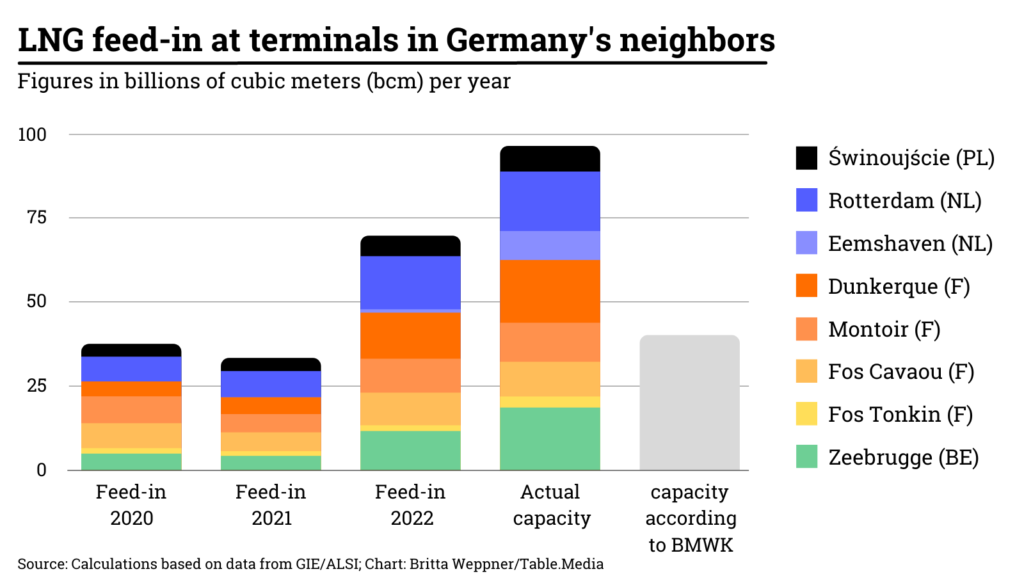

At issue is the capacity of LNG terminals in Germany’s neighboring countries. In total, Poland, the Netherlands, Belgium and France have eight terminals for the import of liquefied natural gas. Due to their geographical proximity, “these play an important role for Germany’s supply today,” the ministry led by Robert Habeck wrote in a paper sent to the media in mid-December to mark the inauguration of Germany’s first LNG terminal. “However, these together represent a regasification capacity of only about 40 bcm per year – against a gas demand of about 95 bcm per year for Germany alone,” according to the paper.

However, this figure is not correct. As an evaluation of the daily figures of the European gas network operators (AGSI) by Berlin.Table shows, the terminals in the aforementioned neighboring countries fed in almost 70 billion cubic meters in 2022. However, even this does not correspond to the maximum capacity; this amounts to 96 billion cubic meters per year if the operator data is added up and even 99 billion cubic meters if each terminal’s real daily maximum value is extrapolated to the entire year.

When asked, the ministry did not provide a conclusive explanation for the incorrect figure. It is conceivable that the figure of 40 billion cubic meters given was based on the figures for previous years: In 2020, 38 billion cubic meters of gas were injected at the LNG terminals in neighboring countries, while in 2021, the figure was 33 billion cubic meters.

For some time now, experts have considered the planning of the German LNG terminals to be oversized. The alleged miscalculation has obviously played an important role in this. Robert Habeck had claimed on Tagesthemen before the inauguration of the first terminal that without its own landing points, Germany would face a “gas shortage” this winter. The explanatory memorandum for the LNG Acceleration Act passed in May (pdf) states: “The capacity of the existing European LNG terminals, which can only be used in part for Germany, can – even at one hundred percent capacity utilization – only cover a small part of the shortfall in Russian supplies for Europe.”

This is obviously not true. In fact, the terminals available in neighboring countries can cover the shortfall in Russian natural gas deliveries via Nord Stream 2, which were around 50 billion cubic meters per year in 2021, not only to a small extent but almost completely when fully utilized. This is shown both by a comparison of the actual capacity with the deliveries of the previous years as well as the reality of the past months: The fact that there has not been a shortage in Germany (and its neighboring countries) despite the gas deliveries via Nord Stream 2 being completely stopped since the beginning of September, but rather that the storage facilities have been filled as never before, is – apart from the drop in consumption of about 15 percent – mainly due to additional gas deliveries via the LNG terminals in the neighboring countries.

This is possible without any major problems. Only Poland needs all the liquefied gas it receives at its terminal to compensate for the loss of supplies from Russia. The Netherlands and Belgium, on the other hand, have greatly increased their gas exports to Germany following the halt in deliveries from Russia; France, which previously always purchased Russian gas from Germany, has now been supplying LNG gas to Germany for its part since September – partly via Switzerland. And even in December 2022, the month with the highest LNG feed-ins to date, the terminals in neighboring countries were only at 86 percent capacity.

The years of great climate ambitions are over for the time being. In its program, the Swedish Council Presidency, therefore, emphasizes, above all, the implementation of existing climate targets. The aim is to put Fit for 55 into practice and accelerate the energy transition, according to a statement from Stockholm.

However, a few negotiations on climate legislation are still open in 2023 and will be on the desks of the Swedes in the coming months:

Accordingly, the Commission’s work program for 2023 on the Green Deal also looks rather meager. Planned are:

The Commission’s Green Claims proposal is not in the 2023 work program. It was supposed to have been submitted at the end of last year but was postponed. With the new law, the Commission wants to make advertising with environmental claims more specific and easier to verify in order to prevent greenwashing by companies.

During COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, the EU was said to be adjusting its climate change target (NDC) deposited with the UN in line with the outcome of the Fit for 55 trilogues. Now that the main trilogues on potential emissions savings and renewable expansion pathways have been completed, the European NDC can be updated.

However, it remains to be seen whether the member states will actually agree to increase the 55 percent target for 2030. Two percentage points more due to the higher LULUCF targets are being discussed. However, Timmermans already said in Sharm el-Sheikh that this would not require a new climate target, as the current one states that the aim is to reduce emissions by “at least” 55 percent. It would, therefore, be possible to simply update the annex to the NDC, which must explain how countries intend to achieve their climate targets.

Finally, the texts already adopted will be submitted to the Council and Parliament for a final vote. Adoption of a trilogue result is generally regarded as a formality, but in the case of the ETS reform, in particular, there were still doubts among the member states and in Parliament as recently as December as to whether the compromises of the jumbo trilogue would go through. The first Environment Council and the first plenary session in 2023 will provide information on whether the doubts are great enough.

Jan. 16-20; Davos

Summit World Economic Forum INFORMATION

March 19-21; Hiroshima, Japan

Summit G7

March 20

Publication IPCC Synthesis Report INFORMATION

March 22-24; New York

Conference UN Water Conference

Water is a fundamental part of all aspects of life. Water is inextricably linked to the three pillars of sustainable development, and it integrates social, cultural, economic and political values. At the UN conference, the motto “Our watershed moment: uniting the world for water” will be used to discuss how the SDGs can be achieved with reference to water. INFORMATION

March 28-29; Berlin

Dialogue Energy Transition Dialogue INFORMATION

April 10-17; Washington, USA

Conference Spring Meeting of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank INFORMATION

April 15-16; Sapporo, Japan

Summit G7 Environment Summit

June 5

World Environment Day

June 5-15; Bonn

Conference 58th Session SBI/SBSTA of the UNFCCC: Bonn Climate Change Conference INFORMATION

Sep. 9-10; Delhi, India

Summit G20 Summit

Sep. 12-30; New York

General Assembly UN General Assembly

Oct. 16-18; Rome

Conference World Conference on Climate Change and Sustainability INFORMATION

Oct. 23-27

Conference UN Montreal Protocol Conference on Ozone INFORMATION

Nov. 22-24; Amsterdam

Summit Global Summit on Climate Change INFORMATION

Nov. 30-Dec. 12; Dubai, UAE

Conference UN Climate Conference COP28

Despite lower energy consumption and a record year for renewables, Germany failed to meet its climate targets last year, according to a study by the think tank Agora Energiewende. Emissions stagnated at 761 million metric tons of CO2 compared to the previous year. The target of a 40 percent reduction compared to 1990 was missed by one percentage point. As a result of the Ukraine war, coal consumption increased, which canceled out emission reduction successes. The transport and construction sectors had also missed their climate targets.

According to the study, Germany’s energy consumption fell by 4.7 percent in 2022 compared to the previous year, dropping to its lowest level since reunification. The reasons for this are:

Emissions in the energy sector rose by eight million metric tons of CO2 compared to 2021, despite new records for renewables. The share of renewables in electricity consumption reached a new high of 46.0 percent. However, higher coal-fired power generation prevented a reduction in emissions.

However, Agora warns against overestimating the large contribution of renewables to electricity consumption. “The record year for renewables is weather-related and thus not a structural contribution to climate protection,” said Simon Müller, Director Germany at Agora Energiewende. Germany is heading for a massive gap in renewable expansion, he added.

In the transport sector, emissions of 150 million metric tons of CO2 were well above the target of 139 million metric tons. It was only at the beginning of the year that a report by the Bundestag’s scientific service emerged, accusing Transport Minister Wissing of violating the Climate Change Act. Wissing would have had to present a more comprehensive program to meet the sector targets, which would also have to compensate for the surplus of the last few years. nib

Norway revived the Amazon Fund to protect Brazil’s rainforest. The fund’s largest donor had frozen the money since August 2019, after former President Jair Bolsonaro ousted the fund’s board of directors. The fund still has 620 million US dollars that will be released after Lula da Silva recently took office, Reuters reports.

“Brazil’s new President has signaled a clear ambition to stop deforestation by 2030,” Norwegian Minister of Climate and Environment Espen Barth Eide said. Lula set up the fund in 2008 to obtain international financing for rainforest protection. One of Lula’s first acts after taking office on Sunday was to re-establish the Amazon Fund’s board of directors. Civil society and other stakeholders are broadly represented.

Following Lula’s decision, the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development allocated 35 million euros to the fund on January 1. This brings Germany’s total contribution to the fund to 90 million euros. The UK considers joining the fund, its environment minister Therese Coffey told Reuters in Brasília on Monday. nib/rtr

Sustainable palm oil production helps protect tropical rainforests – for example, in Indonesia, where deforestation rates have recently fallen sharply (Climate.Table reported). However, this can be at the expense of other species-rich ecosystems that are also important for the climate. This is indicated by a recent study published in the nature ecology & evolution journal. Its authors call for sustainability regulations for palm oil to be extended to all tropical habitats.

Global demand for palm oil is growing. The economic incentive to expand the area under cultivation is correspondingly high. According to the study, around two-thirds of the global palm oil supply is currently produced in a way that avoids deforestation (with so-called zero deforestation commitments (ZDCs)). Such ZDCs are established, for example, by the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil.

The ZDC regulations are primarily intended to preserve particularly biodiverse and carbon-rich forests. However, according to this study, the criteria by which they evaluate biodiversity and carbon content underestimate the ecological importance of tropical savannahs, scrublands or dry forests. For example, they focus on the carbon bound in plants but neglect the carbon stored in the soil, which should be particularly taken into account in grasslands.

But it is precisely in the grasslands or dry forests of the tropics – especially in South America and Africa – that more than half of all areas suitable for expanding oil palm cultivation are located, according to the study. If they were actually used for this purpose, the habitats of many already endangered vertebrates would be threatened.

In addition, large amounts of CO2 could be released into the atmosphere: “The potential greenhouse gas emissions (…) could in many places be as high as those from a conversion of the rainforest (into palm oil plantations).” However, there is still a lack of data to estimate emissions. ae

A climate conference in the form of an annual caravan is no longer in keeping with the times. COP27 has once again shown this. It was supposed to focus on the implementation of previous pledges and on accelerating the transformation of the global energy system – especially in view of the geostrategic crisis in the wake of the Russian attack on Ukraine.

But reducing global emissions once again made no headway at this COP. Negotiations were partially blocked and once again COP had to be extended to reach at least a minimum consensus. The climate crisis grows ever more urgent, and the pressure to act is enormous. The gap between necessary ambition and measurable results will also characterize 2023.

A permanent assembly of the global climate community could bridge it. It would be a global climate parliament,

In it, the negotiating groups could jointly clarify those urgent issues of international climate policy that have so far been resolved far too slowly or not at all within the COP framework. Here are three examples.

In essence, the entire Paris Agreement was already operationalized years ago, and implementation could actually move forward. But there was one exception: The rules for Article 6 were not adopted until the COP in Glasgow, six years after Paris.

We can no longer afford such delays. Additional and more efficient workflows are needed to speed up decisions for global climate action. This also applies to the newly initiated JETPs with South Africa and Indonesia, which are intended to serve as a template for global transformation. In such a parliament, committees could, for example, negotiate specifically on pending issues of structures and governance, seeking advice and building on the existing work of the individual negotiating groups.

Starting in 2020, the industrialized countries have promised to make 100 billion U.S. dollars available annually for climate protection and adaptation. This is the main budget for international climate policy. From 2025, the sum is to rise again, and the gaps of the past years still need to be filled.

But many questions remain unanswered: How can it be ensured that the funds are used effectively? How can the private sector be involved? Despite the general agreement reached at COP2several of questions also remain unanswered about loss and damage.

The answers to these questions will be decisive in determining whether an efficient and credible climate policy is possible going forward. So instead of looking for answers only once a year, somewhere in the world and often under huge time pressure, it is better to deal with them collectively in a standing committee. This is similar to what we know from our parliaments.

The drought and floods in Pakistan have shown how urgently countries will need sophisticated and internationally coordinated aid after extreme weather events. This is even more true for war-torn regions.

Consistently, aid should be coordinated from the center of a global climate community and debated there accordingly. A global climate parliament cannot replace the dense network of international aid organizations. But it can serve as a compass to help accelerate the disbursement of funds and also raise global awareness of climate risks.

Will countries agree to transform the COP process into a permanent assembly? Past efforts to reform the UN Security Council make this seem utopian. But I do not believe that a global climate parliament is politically unachievable.

The minimum requirement for such a parliament would be for it to work in committees to draft finalized resolutions for the heads of government. The UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and the UN General Assembly (UNGA) already operate on this principle. They meet permanently, but cabinet members attend the High Level Segment of ECOSOC or the General Debate of UNGA once a year.

To obtain the necessary legitimacy to make binding decisions, all signatory states would have to be represented, for example with three delegates and their staff. This would still make the assembly smaller than the current German Bundestag. Representatives of civil society, academia and other non-state actors should be admitted as permanent observers. In addition to a fixed location – Bonn as the seat of the climate secretariat, Nairobi or New York – a rotating model every four to five years could also be considered.

But these are details. The crucial point is that climate conferences and climate parliaments are not mutually exclusive. Global climate conferences fulfill many useful functions. For example, they raise global awareness and build civil society pressure. But that is no longer enough. The momentum for global climate action must be sustained and expanded. The legitimacy of the process must be strengthened. The interests of the Global South and future generations must also be adequately represented. A global climate parliament would provide the opportunity for this.

Dennis Tänzler is Director and Head of Programs Climate Policy at adelphi, the independent think and consulting factory for climate, environment and development based in Berlin.

Brazil’s new Environment Minister, Marina Silva, knows how to get her way. Even against the president, if need be. Shortly before Christmas, Brazil’s newly elected President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Workers’ Party (PT) offered her the position of head of the climate action department in his government. She declined – she wanted to be a minister, she is reported to have said. With that, she got her way: On January first, the new government under Lula was inaugurated, and Marina Silva of the REDE party (Rede Sustentabilidade, sustainability network) is the new environment minister.

Silva now faces an enormous task. Under the previous government of far-right Jair Bolsonaro, deforestation in the Amazon has increased by 60 percent, and he has also left behind mostly destruction in Brazil’s Cerrado steppe region. Scientists warn that the Amazon‘s ability to absorb CO2 is about to reach a tipping point.

That’s not all: The country’s environmental protection agencies are also in a similarly disastrous state as the rainforest. The environmental protection agency IBAMA, for example, was recently almost incapable of acting. The lack of control has also led to increased organized crime in the Amazon region. At the same time, it is difficult in Brazil to assert environmental concerns against the powerful agricultural lobby.

Marina Silva knows this. During the election campaign, referring to the powerful agribusiness industry, she said that it is now possible to increase agricultural production without further deforestation. As promised by Lula, she wants to make the goal of “zero deforestation” a reality in the Amazon region and “all other biomes,” and monitor that the government does not forget that “environmental protection is the top priority.”

Marina Silva, now 64, stands for a holistic, intersectional view of environmental protection and climate action. She wants to bring social justice together with the protection of ecosystems. She has as much experience in Brazil’s environmental movement as few others. Silva grew up in the remote Amazon state of Acre, in a low-income family of traditional rubber tappers. She didn’t learn to read and write until she was 16. Together with environmental activist Chico Mendes, who was murdered in 1988, Silva built up the trade union movement in the region. In 1994, at the age of 36, she became Brazil’s youngest female senator.

Marina Silva is already familiar with the work in the Ministry of the Environment, having held the post of Environment Minister from 2003 to 2008. At that time, she was still a member of the PT Workers’ Party. During her term in office, deforestation in Brazil fell by 67 percent. As environment minister, Silva was soon regarded as a relentless fighter for protecting the environment and the people in the rainforest regions – and repeatedly came into conflict with the Lula government, whom she accused at the time of putting economic interests above socio-ecological ones. Over the years, she lost disputes over many of these issues. For example, she was unable to prevent the construction of the Angra 3 nuclear power plant. In 2008, she, therefore, resigned because of a lack of support for her agenda.

She did not give up her commitment to Brazil’s environment. On the contrary, after this break with Lula, Marina Silva herself ran for president in 2010 and 2014. Both times she came in third place, with Dilma Rousseff of the Workers’ Party being elected for both terms. In 2018, Silva ran again – but with a much worse result than before. At the time, she was repeatedly criticized both at home and abroad for belonging to an evangelical church. She subsequently distanced herself from evangelical politics.

It was not until last year’s election campaign that Marina Silva and President Lula came closer again. Here, too, she showed that she was not afraid to stand up for her convictions. She pledged her support to Lula only on the condition that he sharpen up his environmental protection program. And that’s what he did. For the climate and the Amazon region, this persistent woman could be a good sign. Lisa Kuner

Did you also toast 2023 wearing a T-shirt and shorts in spring-like temperatures? It was the warmest New Year since record-keeping began. And probably a harbinger of what we can expect to see in 2023 and beyond.

In this Climate.Table, we, therefore, take a look at what the new year holds in store: We explain, among other things, the hottest trends in global climate policy and the tasks that await the EU in the process. We describe the Swedish EU presidency’s balancing act between climate action in Brussels and climate change deniers at home in Stockholm. We look at Brazil’s old and new environment minister and her fight to preserve the Amazon rainforest. And we introduce the idea of establishing a global “climate parliament” alongside the annual COPs.

However, one should be careful with concrete predictions. If 2022 has taught us one thing, it is that there is little guarantee that things will happen as we think they will. The only thing certain is uncertainty. Especially in the climate crisis. All the more reason for us to explain in greater detail what is happening where, how and why. We look forward to having you with us and wish you a healthy new year.

It was already clear in 2022: The long-term warming of the atmosphere manifests itself more and more violently even in the short-term weather. With emissions and CO2 levels in the atmosphere at a new high, temperatures climbed again in 2022, as they had in the previous eight years – to an average of 1.15 degrees Celsius above the long-term global average and new all-time highs in some regions. And all this after three years marked by an exceptionally long “La Niña” phenomenon – the temperature anomaly in the Pacific Ocean that normally provides for global cooling. Meteorologists now expect this cooling trend to end in 2023 – and, in all probability, the start of an “El Niño” period that could drive global temperatures even higher.

The end of Russian gas supplies to Europe and global uncertainty have thrown markets into severe turmoil. High gas prices make renewables competitive worldwide – but also bring back coal. A warm winter in Europe could lower demand and prices. But lower prices could also drive consumption and emissions back up. In any case, future emissions will also be determined by how this year’s decisions are made on new gas drilling, for example, in Africa, LNG terminals in Europe, or more coal in Southeast Asia. Experts warn that the new interest in gas could make the Paris climate targets impossible.

In 2022, global carbon emissions have risen once again, by just under one percent. Will the peak finally be reached in 2023? That could be possible if renewables continue to grow as strongly as they currently are, the global economy weakens due to the Chinese Covid problems, and efficiency and saving are worthwhile while prices are high. But it may still take time – ideally, the IEA does not expect the peak until 2025 – and as a result a 2.5 degree Celsius rise in global temperature in 2100. In contrast, to meet the 1.5 limit, emissions would have to drop rapidly from 2025 onward.

The massive tax cuts in the USA through the IRA investment program should make renewables affordable enough that green hydrogen will be cheaper to produce there than with fossil fuels as early as 2025. In the US, this could “in time” make green hydrogen as cheap as previously predicted for 2050, analyzes economist Veronika Grimm – with the effect that the US could have major advantages for electrolyzer sites. This, in turn, could lead to an increase in European subsidies for the establishment of green hydrogen industries, making development much faster than expected here as well.

The third goal of the Paris Agreement, to coordinate financial flows toward climate action, will move into sharper focus this year: At the spring meeting of the World Bank and IMF in Washington in April, influential countries want to push for a reform of global financial institutions. The “Bridgetown Initiative,” presented by Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados and supported by many countries, is intended to better protect emerging and developing countries against climate shocks with the help of the World Bank and development banks. In addition to loans of one trillion dollars, this also includes 100 billion dollars from special drawing rights at the IMF, which are to be regarded as favorable financing for the poor states. However, the German Federal Bank and the European Central Bank are putting the brakes on this.

The big success of COP27 was the decision to set up a fund to finance climate loss and damage. However, the important details were left blank: Who pays how much, who gets the money, and what do applications and projects look like? All these questions are to be clarified by a “transition committee” with 24 representatives (10 from industrialized countries, and 14 from developing countries). During 2023, this committee will define the important details, which will then be decided at the COP28 at the end of the year. However, only five seats had been filled by the deadline of December 15, 2022.

As this year’s G20 presidency, India also wants to make its mark in climate policy – on the one hand with benefits for poor countries and with sharp demands for more money and know-how from the Global North. The focus will be on financial issues, but also on lifestyles and securing sustainability goals. At the same time, however, the Indian government is also talking with industrialized countries, as it has already done with South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam, about a partnership for a just energy transition (JETP). So far, these talks have failed because India is unwilling to negotiate a coal phase-out, which, however, is crucial for the industrialized countries.

At COP27, it was unclear how serious India was about a global push for a resolution to “reduce all fossil fuels” that did not make it into the final declaration. The EU did not pick up the ball, which might have partially broken the G77 group from its ties to China. Other developing countries also openly criticized China’s role for the first time. This shows that a new “High Ambition Coalition” (HAC) of progressive industrialized, emerging and developing countries might be possible – which once again came together at the end of COP27 after initial difficulties. The process for the Biodiversity Convention could serve as a model. At COP15 in Montreal in December, it was decided that the HAC on biodiversity should have its own permanent secretariat.

The election victory of Brazil’s new President Luis Inacio Lula da Silva, the inauguration of Environment Minister-designate Marina Silva, and the revival of the Amazon Fund by the industrialized countries give a reason for hope: Can Brazil’s new president make good on his promise to stop deforestation in the Amazon by 2030? And: What can be expected from the global alliance of rainforest countries comprising Brazil, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo as the “Rainforest OPEC”?

In December it will become clear in Dubai whether and how seriously the UN countries are taking their Paris pledges: Then the “Global Stocktake” will officially show whether the climate plans (NDC) of the countries meet the requirements of science regarding their targets and measures to keep the 2 or 1.5 limit. The answer from this global stocktaking of climate action is already clear: That has failed. It is doubtful whether the countries at COP28 in Dubai will decide collectively and bindingly to do more on avoidance and adaptation – and then also define this in detail for themselves.

Even if many environmental organizations hate to hear it: The controversial permanent storage and use of CO2 (CCS, CCUS), for example under the seabed, gains an increasing importance. The German government plans to present an official CCS strategy in 2023. In Europe, Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands are pressing ahead with this project at full speed with their own bids for CO2 final storage facilities. A large market for this service is emerging worldwide, capturing carbon dioxide mainly from industrial operations in the steel, glass or cement sectors and storing it in decommissioned gas storage facilities, for example.

Whether conflicts, pandemics, economic recessions or new inventions: 2023 will also hold surprises for climate policy: How will the Covid situation in China affect the global economy? What will be the further impact of Russia’s war in Ukraine? What would be the consequences of a power vacuum in Iran for the global oil market? What progress will ambitious climate policies in the climate heavyweights EU, USA, Australia or Brazil bring? Even in 2023, only one thing is certain: uncertainty.

It will be a frosty welcome for the EU Commission: To mark the start of the Swedish Council Presidency, the government of Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson will receive the entire Commission in the town of Kiruna in the far north on January 12 and 13. This is where Europe’s largest iron ore deposits are located. And here, thanks to stricter EU climate legislation, a gigantic industrial transformation is taking place driven by climate policy.

However, it is still unclear how frosty relations between the new Swedish government and the EU will become on climate policy. “Green & energy transitions” is one of four top priorities for Sweden’s presidency of the Council of the European Union, which started on Jan 1st. . This choice of focus somewhat deviates from the new government’s own domestic agenda, where

During its half-year term, Sweden is likely to bring already tabled climate dossiers forward, but new initiatives are hardly to be expected, maybe except for nuclear power.

The three-party minority government, that took power after the Swedish elections in September 2022, consists of prime minister Ulf Kristersson´s right-wing Moderates (M), the Christian Democrats (KD) and the Liberals (L). As these three only control 103 seats in the Riksdag, fewer than the opposition Social Democrats can muster alone, Kristersson´s government in more or less every vote, is dependent on the active support from the right-populist Sweden Democrats (SD). The latter gained over 20 percent in the September election and form the second-largest parliamentary group.

Infamous for its roots in neo-nazi, xenophobic groupings, SD has, until its recent growth, been politically isolated. Now, this has changed, and its rising influence is mirrored in the new government’s very restrictive immigration policies. On top, SD is also the most powerful critic of Sweden’s traditionally ambitious climate policy. Some of its new MPs are openly climate skeptics, and when the European Parliament adopted the European Climate Law in June 2021, SD’s three MEPs were among the few that voted against it.

In order to win the parliamentary support of the SD, the Moderates and the Christian Democrats gradually distanced themselves before the election from climate and energy policy decisions that they had supported until recently. For example, the new government has promised to dismantle the mandatory blending of transport fuels with renewables. By combining this with lower fuel taxes SD, M and KD, separately, promised the voters to lower fuel prices by 0,5-1 euro per liter if gaining power – promises that probably were crucial for the outcome of the election.

In the energy sector, the rapid expansion of Swedish wind power is likely to be slowed down as the government wants to eliminate some subsidies. It blames the current high electricity prices on the decommissioning of four nuclear reactors between 2015 and 2020 and now wants the remaining fleet of six reactors to be supplemented by new, probably smaller SMR (Small Modular Reactor). To do so, it promises generous loans in particular, but interest from investors appears mixed. The industry welcomes new power capacity. But while new capacity is being added day by day through wind power, potential new nuclear plants will not come online until the mid-2030s.

In the far north of Sweden, however, where the EU Commission will be visiting, the green transformation is already clearly visible. State-owned mining giant LKAB intends to invest some 40 billion euros, partly in expanding the mine, but primarily in new advanced processing methods, based on hydrogen, made from water and electricity from existing, nearby hydro plants, and a hastily expanding number of wind turbines. Two new hydrogen-based steel mills and a giant battery factory are already under construction in Luleå, Boden and Skellefteå, all close to the Gulf of Bothnia in the Baltic Sea. This re-industrialization, a central part of the former Social-democratic government’s national narrative on the green transition as a tool for re-industrialization and economic growth, will now be taken forward by the new government

The Council presidency might, paradoxically, come as a relief to the more environmentally concerned parts of the government base – including Romina Pourmokhtari, the new, liberal minister of climate and energy. As Council Presidency, Sweden will have to seek compromises and be less able to promote its own positions, which are sometimes less ambitious than mainstream EU policy. These include:

Finally, the government is likely to push for a speedy handling of the expected proposal on stricter CO2 requirements on heavy-duty vehicles. That is because two of the world’s largest truck manufacturers, Volvo and Scania, both of which are strongly committed to the electrification of road transport, are based in Sweden. By Magnus Nielsson from Stockholm

“We need a European John Kerry,” said Peter Liese, environmental spokesman for the EPP, after the end of COP27. Frans Timmermans is overburdened in his role as climate commissioner because he is responsible for both EU legislation and international climate policy, according to Liese. In Sharm el-Sheikh, he said, the bridges were built by others, meaning US climate envoy John Kerry and his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua. Timmermans had no time for any diplomatic COP preparations because he was busy with EU legislation, the MEP accuses him.

In Sharm el-Sheikh, the EU failed to push through its demands for more climate protection through global emissions reductions. Above all, it lacked backing in the global South. An EU climate czar could build and maintain long-term alliances with island states and smaller developing countries on a full-time basis. Michael Bloss, a Green MEP in the EU Parliament, said such climate partnerships are the solution for higher international climate targets.

This opens the debate on an “EU Climate Czar.” But there are difficult questions of detail:

An EU climate czar is not a new demand. After the failed COP in Copenhagen, there had been talks that the first EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Catherine Ashton, would also be responsible for foreign climate policy, says Runge-Metzger. But the new Commission structure created the position of EU climate commissioner. The debate flared up briefly under Jean-Claude Juncker but was quickly put to rest, Runge-Metzger says.

The climate commissioner himself sees no need for a new position. He is responsible for implementing EU legislation as well as promoting international climate protection measures, according to his office. Separating the two roles would be counterproductive. Runge-Metzger agrees. In international negotiations, Timmermans would benefit from his practical experience with the Green Deal.

A climate commissioner appointed during this legislative term is considered unrealistic anyway. However, the debate could come up again for the 2024 European elections – especially in the EU Parliament. There, the EPP had already achieved a majority in the Development Committee in September last year for the creation of a budget for an EU climate envoy.

In terms of profile, a climate envoy should already have experience in climate negotiations, know the structures of climate conferences and have a certain standing in the scene, says Liese.

At issue is the capacity of LNG terminals in Germany’s neighboring countries. In total, Poland, the Netherlands, Belgium and France have eight terminals for the import of liquefied natural gas. Due to their geographical proximity, “these play an important role for Germany’s supply today,” the ministry led by Robert Habeck wrote in a paper sent to the media in mid-December to mark the inauguration of Germany’s first LNG terminal. “However, these together represent a regasification capacity of only about 40 bcm per year – against a gas demand of about 95 bcm per year for Germany alone,” according to the paper.

However, this figure is not correct. As an evaluation of the daily figures of the European gas network operators (AGSI) by Berlin.Table shows, the terminals in the aforementioned neighboring countries fed in almost 70 billion cubic meters in 2022. However, even this does not correspond to the maximum capacity; this amounts to 96 billion cubic meters per year if the operator data is added up and even 99 billion cubic meters if each terminal’s real daily maximum value is extrapolated to the entire year.

When asked, the ministry did not provide a conclusive explanation for the incorrect figure. It is conceivable that the figure of 40 billion cubic meters given was based on the figures for previous years: In 2020, 38 billion cubic meters of gas were injected at the LNG terminals in neighboring countries, while in 2021, the figure was 33 billion cubic meters.

For some time now, experts have considered the planning of the German LNG terminals to be oversized. The alleged miscalculation has obviously played an important role in this. Robert Habeck had claimed on Tagesthemen before the inauguration of the first terminal that without its own landing points, Germany would face a “gas shortage” this winter. The explanatory memorandum for the LNG Acceleration Act passed in May (pdf) states: “The capacity of the existing European LNG terminals, which can only be used in part for Germany, can – even at one hundred percent capacity utilization – only cover a small part of the shortfall in Russian supplies for Europe.”

This is obviously not true. In fact, the terminals available in neighboring countries can cover the shortfall in Russian natural gas deliveries via Nord Stream 2, which were around 50 billion cubic meters per year in 2021, not only to a small extent but almost completely when fully utilized. This is shown both by a comparison of the actual capacity with the deliveries of the previous years as well as the reality of the past months: The fact that there has not been a shortage in Germany (and its neighboring countries) despite the gas deliveries via Nord Stream 2 being completely stopped since the beginning of September, but rather that the storage facilities have been filled as never before, is – apart from the drop in consumption of about 15 percent – mainly due to additional gas deliveries via the LNG terminals in the neighboring countries.

This is possible without any major problems. Only Poland needs all the liquefied gas it receives at its terminal to compensate for the loss of supplies from Russia. The Netherlands and Belgium, on the other hand, have greatly increased their gas exports to Germany following the halt in deliveries from Russia; France, which previously always purchased Russian gas from Germany, has now been supplying LNG gas to Germany for its part since September – partly via Switzerland. And even in December 2022, the month with the highest LNG feed-ins to date, the terminals in neighboring countries were only at 86 percent capacity.

The years of great climate ambitions are over for the time being. In its program, the Swedish Council Presidency, therefore, emphasizes, above all, the implementation of existing climate targets. The aim is to put Fit for 55 into practice and accelerate the energy transition, according to a statement from Stockholm.

However, a few negotiations on climate legislation are still open in 2023 and will be on the desks of the Swedes in the coming months:

Accordingly, the Commission’s work program for 2023 on the Green Deal also looks rather meager. Planned are:

The Commission’s Green Claims proposal is not in the 2023 work program. It was supposed to have been submitted at the end of last year but was postponed. With the new law, the Commission wants to make advertising with environmental claims more specific and easier to verify in order to prevent greenwashing by companies.

During COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, the EU was said to be adjusting its climate change target (NDC) deposited with the UN in line with the outcome of the Fit for 55 trilogues. Now that the main trilogues on potential emissions savings and renewable expansion pathways have been completed, the European NDC can be updated.

However, it remains to be seen whether the member states will actually agree to increase the 55 percent target for 2030. Two percentage points more due to the higher LULUCF targets are being discussed. However, Timmermans already said in Sharm el-Sheikh that this would not require a new climate target, as the current one states that the aim is to reduce emissions by “at least” 55 percent. It would, therefore, be possible to simply update the annex to the NDC, which must explain how countries intend to achieve their climate targets.

Finally, the texts already adopted will be submitted to the Council and Parliament for a final vote. Adoption of a trilogue result is generally regarded as a formality, but in the case of the ETS reform, in particular, there were still doubts among the member states and in Parliament as recently as December as to whether the compromises of the jumbo trilogue would go through. The first Environment Council and the first plenary session in 2023 will provide information on whether the doubts are great enough.

Jan. 16-20; Davos

Summit World Economic Forum INFORMATION

March 19-21; Hiroshima, Japan

Summit G7

March 20

Publication IPCC Synthesis Report INFORMATION

March 22-24; New York

Conference UN Water Conference

Water is a fundamental part of all aspects of life. Water is inextricably linked to the three pillars of sustainable development, and it integrates social, cultural, economic and political values. At the UN conference, the motto “Our watershed moment: uniting the world for water” will be used to discuss how the SDGs can be achieved with reference to water. INFORMATION

March 28-29; Berlin

Dialogue Energy Transition Dialogue INFORMATION

April 10-17; Washington, USA

Conference Spring Meeting of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank INFORMATION

April 15-16; Sapporo, Japan

Summit G7 Environment Summit

June 5

World Environment Day

June 5-15; Bonn

Conference 58th Session SBI/SBSTA of the UNFCCC: Bonn Climate Change Conference INFORMATION

Sep. 9-10; Delhi, India

Summit G20 Summit

Sep. 12-30; New York

General Assembly UN General Assembly

Oct. 16-18; Rome

Conference World Conference on Climate Change and Sustainability INFORMATION

Oct. 23-27

Conference UN Montreal Protocol Conference on Ozone INFORMATION

Nov. 22-24; Amsterdam

Summit Global Summit on Climate Change INFORMATION

Nov. 30-Dec. 12; Dubai, UAE

Conference UN Climate Conference COP28

Despite lower energy consumption and a record year for renewables, Germany failed to meet its climate targets last year, according to a study by the think tank Agora Energiewende. Emissions stagnated at 761 million metric tons of CO2 compared to the previous year. The target of a 40 percent reduction compared to 1990 was missed by one percentage point. As a result of the Ukraine war, coal consumption increased, which canceled out emission reduction successes. The transport and construction sectors had also missed their climate targets.

According to the study, Germany’s energy consumption fell by 4.7 percent in 2022 compared to the previous year, dropping to its lowest level since reunification. The reasons for this are:

Emissions in the energy sector rose by eight million metric tons of CO2 compared to 2021, despite new records for renewables. The share of renewables in electricity consumption reached a new high of 46.0 percent. However, higher coal-fired power generation prevented a reduction in emissions.

However, Agora warns against overestimating the large contribution of renewables to electricity consumption. “The record year for renewables is weather-related and thus not a structural contribution to climate protection,” said Simon Müller, Director Germany at Agora Energiewende. Germany is heading for a massive gap in renewable expansion, he added.

In the transport sector, emissions of 150 million metric tons of CO2 were well above the target of 139 million metric tons. It was only at the beginning of the year that a report by the Bundestag’s scientific service emerged, accusing Transport Minister Wissing of violating the Climate Change Act. Wissing would have had to present a more comprehensive program to meet the sector targets, which would also have to compensate for the surplus of the last few years. nib

Norway revived the Amazon Fund to protect Brazil’s rainforest. The fund’s largest donor had frozen the money since August 2019, after former President Jair Bolsonaro ousted the fund’s board of directors. The fund still has 620 million US dollars that will be released after Lula da Silva recently took office, Reuters reports.

“Brazil’s new President has signaled a clear ambition to stop deforestation by 2030,” Norwegian Minister of Climate and Environment Espen Barth Eide said. Lula set up the fund in 2008 to obtain international financing for rainforest protection. One of Lula’s first acts after taking office on Sunday was to re-establish the Amazon Fund’s board of directors. Civil society and other stakeholders are broadly represented.

Following Lula’s decision, the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development allocated 35 million euros to the fund on January 1. This brings Germany’s total contribution to the fund to 90 million euros. The UK considers joining the fund, its environment minister Therese Coffey told Reuters in Brasília on Monday. nib/rtr

Sustainable palm oil production helps protect tropical rainforests – for example, in Indonesia, where deforestation rates have recently fallen sharply (Climate.Table reported). However, this can be at the expense of other species-rich ecosystems that are also important for the climate. This is indicated by a recent study published in the nature ecology & evolution journal. Its authors call for sustainability regulations for palm oil to be extended to all tropical habitats.

Global demand for palm oil is growing. The economic incentive to expand the area under cultivation is correspondingly high. According to the study, around two-thirds of the global palm oil supply is currently produced in a way that avoids deforestation (with so-called zero deforestation commitments (ZDCs)). Such ZDCs are established, for example, by the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil.

The ZDC regulations are primarily intended to preserve particularly biodiverse and carbon-rich forests. However, according to this study, the criteria by which they evaluate biodiversity and carbon content underestimate the ecological importance of tropical savannahs, scrublands or dry forests. For example, they focus on the carbon bound in plants but neglect the carbon stored in the soil, which should be particularly taken into account in grasslands.

But it is precisely in the grasslands or dry forests of the tropics – especially in South America and Africa – that more than half of all areas suitable for expanding oil palm cultivation are located, according to the study. If they were actually used for this purpose, the habitats of many already endangered vertebrates would be threatened.

In addition, large amounts of CO2 could be released into the atmosphere: “The potential greenhouse gas emissions (…) could in many places be as high as those from a conversion of the rainforest (into palm oil plantations).” However, there is still a lack of data to estimate emissions. ae

A climate conference in the form of an annual caravan is no longer in keeping with the times. COP27 has once again shown this. It was supposed to focus on the implementation of previous pledges and on accelerating the transformation of the global energy system – especially in view of the geostrategic crisis in the wake of the Russian attack on Ukraine.

But reducing global emissions once again made no headway at this COP. Negotiations were partially blocked and once again COP had to be extended to reach at least a minimum consensus. The climate crisis grows ever more urgent, and the pressure to act is enormous. The gap between necessary ambition and measurable results will also characterize 2023.

A permanent assembly of the global climate community could bridge it. It would be a global climate parliament,

In it, the negotiating groups could jointly clarify those urgent issues of international climate policy that have so far been resolved far too slowly or not at all within the COP framework. Here are three examples.

In essence, the entire Paris Agreement was already operationalized years ago, and implementation could actually move forward. But there was one exception: The rules for Article 6 were not adopted until the COP in Glasgow, six years after Paris.

We can no longer afford such delays. Additional and more efficient workflows are needed to speed up decisions for global climate action. This also applies to the newly initiated JETPs with South Africa and Indonesia, which are intended to serve as a template for global transformation. In such a parliament, committees could, for example, negotiate specifically on pending issues of structures and governance, seeking advice and building on the existing work of the individual negotiating groups.

Starting in 2020, the industrialized countries have promised to make 100 billion U.S. dollars available annually for climate protection and adaptation. This is the main budget for international climate policy. From 2025, the sum is to rise again, and the gaps of the past years still need to be filled.

But many questions remain unanswered: How can it be ensured that the funds are used effectively? How can the private sector be involved? Despite the general agreement reached at COP2several of questions also remain unanswered about loss and damage.

The answers to these questions will be decisive in determining whether an efficient and credible climate policy is possible going forward. So instead of looking for answers only once a year, somewhere in the world and often under huge time pressure, it is better to deal with them collectively in a standing committee. This is similar to what we know from our parliaments.

The drought and floods in Pakistan have shown how urgently countries will need sophisticated and internationally coordinated aid after extreme weather events. This is even more true for war-torn regions.

Consistently, aid should be coordinated from the center of a global climate community and debated there accordingly. A global climate parliament cannot replace the dense network of international aid organizations. But it can serve as a compass to help accelerate the disbursement of funds and also raise global awareness of climate risks.

Will countries agree to transform the COP process into a permanent assembly? Past efforts to reform the UN Security Council make this seem utopian. But I do not believe that a global climate parliament is politically unachievable.

The minimum requirement for such a parliament would be for it to work in committees to draft finalized resolutions for the heads of government. The UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and the UN General Assembly (UNGA) already operate on this principle. They meet permanently, but cabinet members attend the High Level Segment of ECOSOC or the General Debate of UNGA once a year.

To obtain the necessary legitimacy to make binding decisions, all signatory states would have to be represented, for example with three delegates and their staff. This would still make the assembly smaller than the current German Bundestag. Representatives of civil society, academia and other non-state actors should be admitted as permanent observers. In addition to a fixed location – Bonn as the seat of the climate secretariat, Nairobi or New York – a rotating model every four to five years could also be considered.

But these are details. The crucial point is that climate conferences and climate parliaments are not mutually exclusive. Global climate conferences fulfill many useful functions. For example, they raise global awareness and build civil society pressure. But that is no longer enough. The momentum for global climate action must be sustained and expanded. The legitimacy of the process must be strengthened. The interests of the Global South and future generations must also be adequately represented. A global climate parliament would provide the opportunity for this.

Dennis Tänzler is Director and Head of Programs Climate Policy at adelphi, the independent think and consulting factory for climate, environment and development based in Berlin.

Brazil’s new Environment Minister, Marina Silva, knows how to get her way. Even against the president, if need be. Shortly before Christmas, Brazil’s newly elected President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Workers’ Party (PT) offered her the position of head of the climate action department in his government. She declined – she wanted to be a minister, she is reported to have said. With that, she got her way: On January first, the new government under Lula was inaugurated, and Marina Silva of the REDE party (Rede Sustentabilidade, sustainability network) is the new environment minister.

Silva now faces an enormous task. Under the previous government of far-right Jair Bolsonaro, deforestation in the Amazon has increased by 60 percent, and he has also left behind mostly destruction in Brazil’s Cerrado steppe region. Scientists warn that the Amazon‘s ability to absorb CO2 is about to reach a tipping point.

That’s not all: The country’s environmental protection agencies are also in a similarly disastrous state as the rainforest. The environmental protection agency IBAMA, for example, was recently almost incapable of acting. The lack of control has also led to increased organized crime in the Amazon region. At the same time, it is difficult in Brazil to assert environmental concerns against the powerful agricultural lobby.

Marina Silva knows this. During the election campaign, referring to the powerful agribusiness industry, she said that it is now possible to increase agricultural production without further deforestation. As promised by Lula, she wants to make the goal of “zero deforestation” a reality in the Amazon region and “all other biomes,” and monitor that the government does not forget that “environmental protection is the top priority.”

Marina Silva, now 64, stands for a holistic, intersectional view of environmental protection and climate action. She wants to bring social justice together with the protection of ecosystems. She has as much experience in Brazil’s environmental movement as few others. Silva grew up in the remote Amazon state of Acre, in a low-income family of traditional rubber tappers. She didn’t learn to read and write until she was 16. Together with environmental activist Chico Mendes, who was murdered in 1988, Silva built up the trade union movement in the region. In 1994, at the age of 36, she became Brazil’s youngest female senator.

Marina Silva is already familiar with the work in the Ministry of the Environment, having held the post of Environment Minister from 2003 to 2008. At that time, she was still a member of the PT Workers’ Party. During her term in office, deforestation in Brazil fell by 67 percent. As environment minister, Silva was soon regarded as a relentless fighter for protecting the environment and the people in the rainforest regions – and repeatedly came into conflict with the Lula government, whom she accused at the time of putting economic interests above socio-ecological ones. Over the years, she lost disputes over many of these issues. For example, she was unable to prevent the construction of the Angra 3 nuclear power plant. In 2008, she, therefore, resigned because of a lack of support for her agenda.

She did not give up her commitment to Brazil’s environment. On the contrary, after this break with Lula, Marina Silva herself ran for president in 2010 and 2014. Both times she came in third place, with Dilma Rousseff of the Workers’ Party being elected for both terms. In 2018, Silva ran again – but with a much worse result than before. At the time, she was repeatedly criticized both at home and abroad for belonging to an evangelical church. She subsequently distanced herself from evangelical politics.

It was not until last year’s election campaign that Marina Silva and President Lula came closer again. Here, too, she showed that she was not afraid to stand up for her convictions. She pledged her support to Lula only on the condition that he sharpen up his environmental protection program. And that’s what he did. For the climate and the Amazon region, this persistent woman could be a good sign. Lisa Kuner