Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow mainly leaves losers. Ukraine is the most bitter case, writes Michael Radunksi in his review of the summit. For the victim of the war of aggression, there is still no tangible prospect for peace on acceptable terms.

This is also evident from the final paper of the meeting, which Frank Sieren reviewed for us. While there is mention of peace, what it would actually mean: Russia is allowed to keep its conquered territories. After all, according to Moscow’s understanding, they belong to Russian territory.

But Russia is no winner either. The paper is rife with humiliations for the so-powerful Kremlin leader. Xi exploits his strong position to subject Putin to unacceptable positions. Xi lets Putin clearly feel the Chinese dominance.

However, neither has China gained much. While Xi is clearly the stronger partner, his visit entangled him even deeper in the war and raised expectations of a Chinese role in the peace process. In Western eyes, China is simultaneously moving very close to being an outcast. Although the Beijing-Moscow axis has been strengthened, Xi has also further tied himself to the potential loser Putin. But it is too late for him to back out.

A breakthrough in Xi’s Covid policy also comes a bit late: China approved its first mRNA vaccine – a domestic creation, developed at great speed and with a huge research effort. It would have been quicker to import the vaccine in time from its important trading partner Germany, writes Joern Petring. And China could then still have built up its own mRNA industry. But what matters most to Xi, just like in his dealings with Russia, is breaking away from the West.

From a political perspective, Xi Jinping’s visit to Russia was conservative: no impetus for Ukraine but continued close, strategic partnership with Vladimir Putin. Economically, China is coolly exploiting the effect of Western sanctions and deepening Russia’s dependence on the People’s Republic. In the future, Beijing can be expected to make not only economic but also increasingly strategic demands on Moscow.

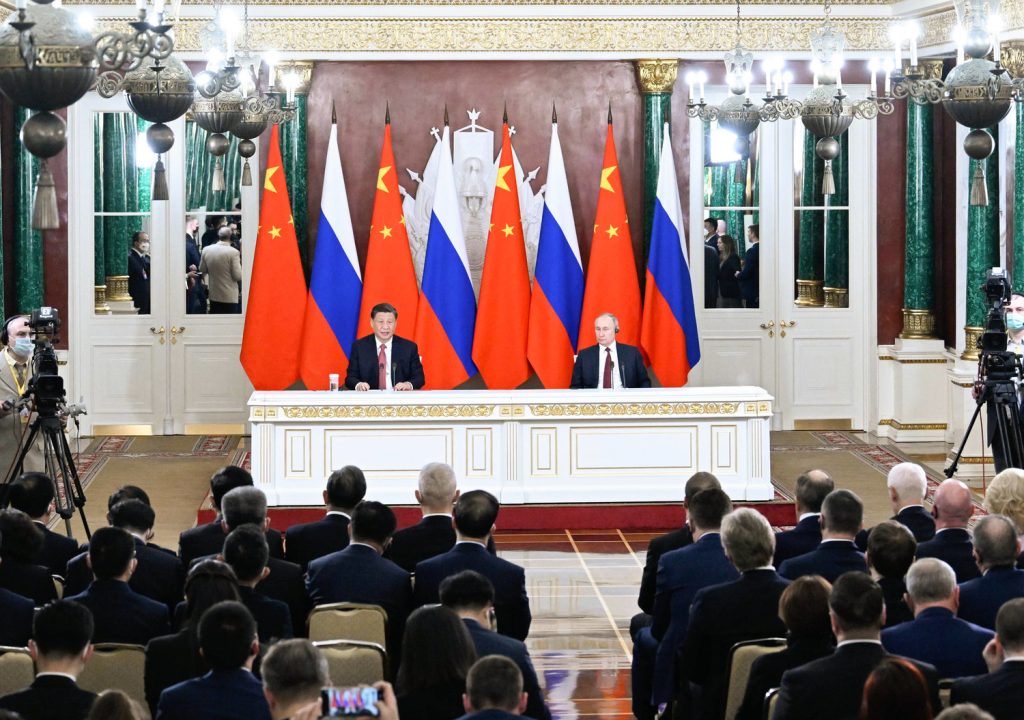

Politically, Xi’s visit raised hopes among some observers for diplomatic progress in the Ukraine war. China had presented a 12-point paper on a political solution in early March and recently scored points elsewhere as a mediator – namely with an agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Moreover, Xi had announced his visit to Moscow as a journey of peace.

But as a possible peacemaker in the Ukraine war, Xi disappointed such hopes in Moscow almost across the board. Apart from the joint rejection of a nuclear war, nothing was achieved from the Western point of view: no halt to the hostilities and also no new impetus with regard to his own 12-point paper.

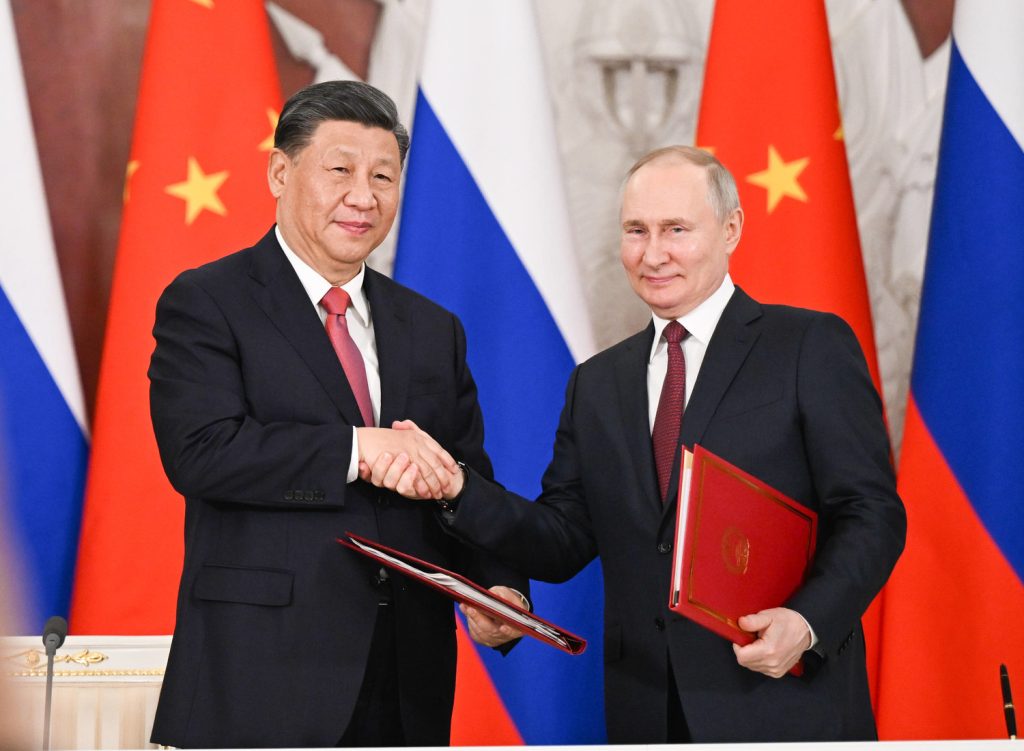

What’s more, while Xi and Putin celebrated their friendship together under golden chandeliers, the Ukrainian president in Kyiv was left only with the prospect of a possible timely phone call from Xi. He welcomed even that vague announcement. Zelenskiy knows that Xi could exert influence on Putin if he wanted to and must therefore leave no stone unturned.

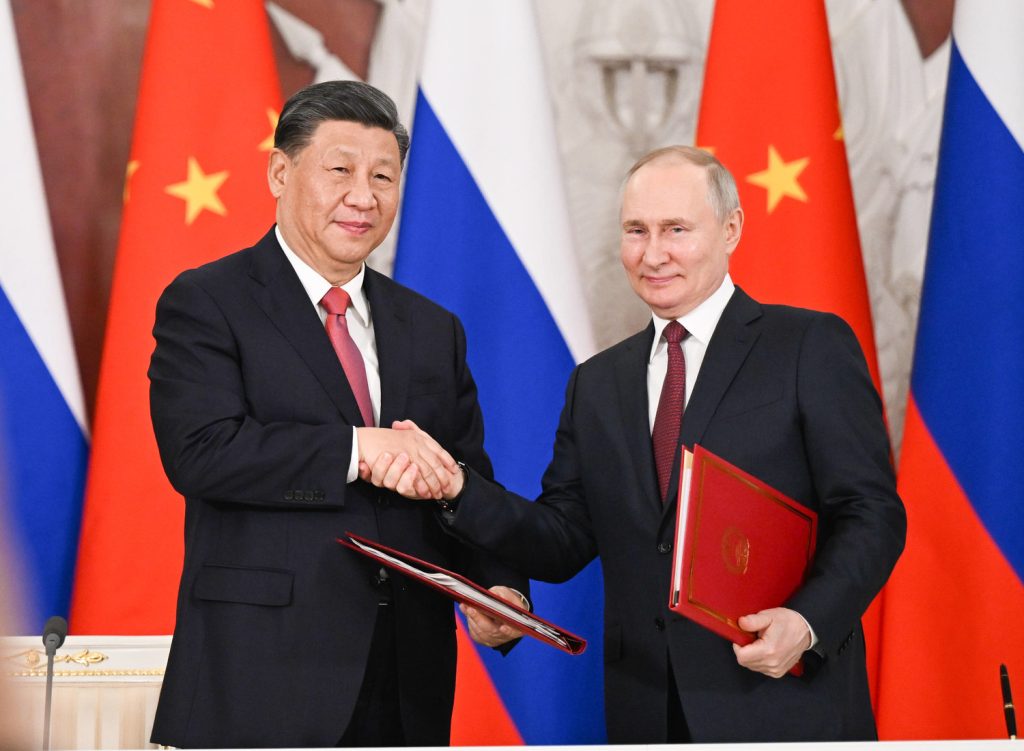

Economically, according to the Kremlin, two agreements, in particular, were signed, as well as several small projects in areas such as forestry, soybeans, television and industry in Russia’s Far East. Almost devoutly, Putin assured that his country would continue to satisfy even China’s ever-increasing hunger for energy. Record deliveries are already being reported through the “Power of Siberia” pipeline. In addition, Putin is said to have proposed a new pipeline through Mongolia during the talks.

In Moscow, it became clear how coolly Xi monetizes Russian dependence – through enormous discounts, increasing supplies of raw materials, or simply hard currency. Two-thirds of bilateral trade is already conducted in rubles or yuan, he said. Putin also promised to settle Russia’s global commodity shipments in yuan in the future. And so China benefits even where it is not directly involved in trade.

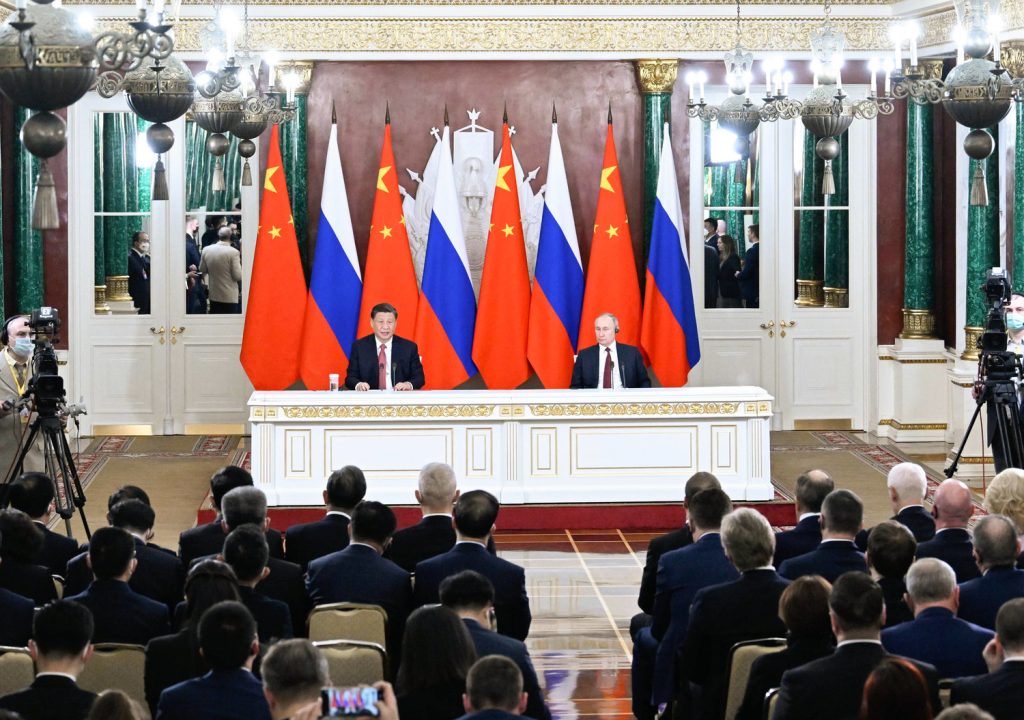

During the meetings in Moscow, it was noticeable that there was rather little of the enthusiasm of February 2022 – when Xi and Putin proclaimed their boundless friendship in Beijing. Both reaffirmed their close strategic partnership in an almost sober and matter-of-fact manner.

Nevertheless: Politically, Xi reaffirmed in Moscow his great closeness to Putin. China’s head of state continues to hold rock-solid to a man who would be arrested immediately on the basis of an international arrest warrant in 123 countries of the world (all of which recognize the International Criminal Court ICC). Xi praises Putin’s strong leadership in Moscow and invites his dear friend to Beijing for a return visit. So much, by the way, for respecting international law. It must therefore be thought-provoking when Xi announces in Moscow that China is ready to “watch over the world order based on international law” together with Russia.

Xi stands by Putin and accepts that his image will be damaged, especially in Europe – because China cannot win anything in the USA at the moment anyway.

But it is probably only a matter of time before Xi demands more from Putin in return for his support than just discounts and raw materials. Geopolitically, the focus is likely to shift to regions where Russia is still the leader, but China is increasingly making its own demands: the Arctic, Central Asia, or Russia’s historically good relationship with India, which is a thorn in China’s side.

Joint final declarations in politics are always the result of a struggle for power. The joint declaration of the Xi-Putin summit at the beginning of the week is a closing of ranks against the West, but above all, a shift in the balance of power in favor of China – and in the direction of a peaceful solution to the conflict. The West wants that, too. But not at the price Beijing is offering: A cease-fire and talks without Putin having to withdraw from the occupied Ukrainian territories. Overall, the paper documents how weak Russia’s position is vis-à-vis China after the unfavorable course of the war.

Xi is forcing Putin to take positions that he does not actually want to take. In doing so, he shows his power and criticizes him at the same time. The West’s wish is for Xi to distance himself from Putin and publicly criticize his war of aggression, even break with him. The Chinese way of criticism, however, is more indirect. Xi’s intention is to get Putin to relent without destroying the partnership with its neighbor, with whom China shares a 4,200-kilometer border. Beijing has a clear goal: The war should end quickly – and Ukraine, with which China had close relations before the invasion, should neither be subjugated by Putin nor join NATO.

Key takeaways from the brief joint statement at the conclusion of the meeting:

First point for Beijing: criticism against encroachment on foreign territory. “The purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter must be observed and international law must be respected,” the statement reads at the very beginning. Article 2, item 4 of the Charter prohibits member states from “using in their international relations any threat or use of force directed against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” Clearly, Putin has not complied and is being urged by Beijing to now relent.

Second point for Beijing: China cements its leadership role. “The Russian side speaks positively about China’s objective and impartial position in the Ukraine war,” is the next position. Putin is forced to concede here: What China says is right. And China wants peace. Humiliating for Putin.

One point for both against the West: “No country may seek military and political advantages that are harmful to a country’s legitimate interests,” the statement continues. This is an important principle, but also an iridescent one that everyone can interpret for themselves. China here means the US with NATO, but also Russia itself. Putin probably sees only NATO in this and can sell this at home as a success. Both can claim a point for themselves here.

Third point for Beijing: The very next sentence is about peace. “Russia reiterates its commitment to resume peace negotiations as soon as possible, which China welcomes.” China is forcing Russia to make this commitment. But both are also saying with this: It is not up to us that there are no peace negotiations yet.

Fourth point for Beijing: Russia “welcomes the constructive proposals in China’s position on the peaceful resolution of the Ukraine crisis” reads the next position. Another humiliation. And then the man who started a war must also concede: “Responsible dialogue is the best way to find appropriate solutions.” And not war.

One point for Putin: “Both sides reject any unilateral sanctions not decided by the UN Security Council.” That, after all, is a clear point for Putin. After all, the sanctions against Russia were not confirmed by the UN Security Council but were imposed by the West on its own. The majority of the world does not support the sanctions.

China has approved its first mRNA vaccine after a long wait. On Wednesday, the Chinese company CSPC Pharmaceutical announced on the Hong Kong stock exchange that it had received emergency approval for its mRNA vaccine developed against the Omicron variant. The company, based in Shijiazhuang, Hebei province, did not initially provide details on when the vaccine would be used in Chinese vaccination centers and hospitals.

China had rapidly developed several of its own vaccines since the outbreak of the pandemic. However, these were conventional inactivated vaccines, which tend to be less effective than modern mRNA vaccines. In Germany, by contrast, BioNTech’s mRNA vaccine was already available in the first major vaccination campaign in December 2020, and it eventually took China almost two and a half years to catch up.

After Beijing finally capitulated to the Omicron variant in December 2022 and practically threw its strict Covid measures overboard, a huge Covid wave swept through the country. Although the official death toll is still only in the tens of thousands, model calculations suggest at least one million victims. If an effective mRNA vaccine had been approved earlier, it could have been widely inoculated as a booster. Human lives could have been saved in this way.

But it was more important for Beijing not to be dependent on foreign countries. Even the new Chinese Premier Li Qiang, a close confidant of Xi, could not change this. As the then Shanghai party chief, he reacted quickly in the spring of 2020 and allowed the Chinese corporation Fosun to sign a contract with BioNTech. Fosun was to take over the production and distribution of BioNTech’s vaccine in China. More than a year later, the party newspaper Global Times reported on a video conference between Li and BioNTech founder Uğur Şahin. It was “very likely” that BioNTech would soon be approved in China, the article said. But then the central government apparently intervened. The approval failed to materialize.

It is true that at least German citizens living in China are now allowed to be vaccinated with BioNTech. In retrospect, however, this was probably primarily a gesture of goodwill. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was able to announce the good news during his trip to China at the end of last year, and observers at the time saw a chance that, with some delay, there could also be a broad market launch.

In addition to CSPC, at least three other Chinese companies are researching their own mRNA vaccines. Suzhou Abogen Biosciences received emergency approval in Indonesia last year – though still not in China. In addition, Stemirna Therapeutics of Shanghai and Cansino Biologics of Tianjin began initial human testing last year. If these companies also follow suit soon with approvals in their own countries, there will probably be no room left for foreign suppliers like BioNTech. Joern Petring

Federal Research Minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger wants to expand cooperation with Taiwan in semiconductor, hydrogen and battery research. “Germany is very strong in basic research, Taiwan very strong in application and transfer,” the FDP politician said Wednesday at the end of her two-day visit to Taipei. Asked about possible plans of the semiconductor manufacturer TSMC, she referred to the responsibility of the Ministry for Economic Affairs and the Chancellery. But of course, she said, there was a great deal of interest in this. There is a desire to build a chip infrastructure in Germany and Europe, she said. “Taiwan can be a role model and partner in this.”

At her press conference, Stark-Watzinger again rejected Chinese criticism of the visit to Taiwan, which Beijing regards as a breakaway province. She said she was conducting the talks as a specialist minister and that “all relevant players” had been involved. “The trip to Taiwan is within the framework of the German government’s ‘one China’ policy,” she stressed. The visit had been prepared with the Chancellery and the Foreign Ministry, she said. Cooperation at the technical level should become the norm in the future, she said. On Tuesday, the German government had reacted calmly to Chinese criticism of the visit.

There is worldwide competition for more technological sovereignty, Stark-Watzinger explained her trip. Taiwan has the most modern technology, but at the same time is an open and free society, as well as a constitutional state. For this reason, she said, one could also discuss issues in the field of artificial intelligence with Taiwan as a value partner. rtr/ck

There is renewed excitement about Huawei: Telekom and the Chinese network supplier are said to have agreed in 2019 that Huawei would supply Germany with network components containing American parts as a precautionary measure – before US sanctions against the company take effect. Telekom is then said to have stored the parts for later use. This is reported by Handelsblatt, which has the contract from back then.

At the very least, this contract goes against the spirit of the US sanctions, which were intended to make it difficult for Huawei to do business internationally. This is a delicate operation for a partly state-owned company in the current trade policy mood.

At the time, however, the agreement was presumably perfectly legal. The aim was to secure Telekom’s supply of key parts from its long-time partner Huawei, which the company values for its reliability. Peter Altmaier, the Economy Minister at the time, was not averse to doing business with Huawei. The US sanctions, in turn, had been decided by then-US President Donald Trump, whose policies were always suspected of not being entirely rational.

Four years later, the situation is very different. Today, the sanctions policy of the Trump era is being continued by a more credible president, Joe Biden. Authoritarian Russia, which is allied with China, has proven to be aggressive and wants to blackmail Western Europe with gas supplies. In Germany, two coalition partners who are decidedly critical of China have been sitting at the cabinet table since the change of government.

Meanwhile, the EU recommended that its members rely on European rather than Chinese suppliers for network expansion. The agreement to stockpile electronics with potentially sanctioned US components looks suspicious from this perspective. Huawei itself presents the agreements with its customers as routine procedures. It is important for the company to be able to deliver promised parts. However, Huawei cannot comment on specific agreements with customers in this area for contractual reasons. fin

The report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) presented on Monday came about only after a hard struggle over content, goals and wording. This is the result of extensive research by Climate.Table. The precise wording in the “Summary for Policymakers” (SPM) to the synthesis report of the 6th IPCC report is extremely important. The report “summarizes the state of knowledge on climate change,” and its words are now considered scientifically and politically approved – and thus form the basis of global climate policy. One of the countries that repeatedly caused discussion at the conference to finalize the text in Interlaken, Switzerland, was China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

China, for example, was unable to accept the creation of a new global climate target for 2035: Emissions of all greenhouse gases are to be reduced by 60 percent by then and minus 65 percent for CO2. China resisted mentioning a concrete figure, as insiders confirm to Climate.Table. After much back and forth, it was removed from the running text – and moved to a separate table. However, this is so prominently placed that the intervention is more of an own goal. Officially, China plans to peak its emissions in 2030. By 2060, the country wants to become climate neutral.

China also insisted on the wording that the Paris climate agreement had been adopted “under the Framework Convention on Climate Change”. This is a sign that China continues to insist on the different responsibilities between old and new industrialized countries – and that China continues to see itself as a developing country, which means that it can defend itself against possible demands, for example, in the area of climate financing. Basically, the struggle for the report revealed the well-known front positions in global climate protection: The EU, USA and Japan are pushing for far-reaching formulations in principle – China, India and Saudi Arabia are leading the blockade. bpo/ck

Compared to the first two months of 2022, Germany’s exports to the People’s Republic slumped by more than eleven percent to €15.2 billion in January and February. This is according to preliminary data from the Federal Statistical Office, which was available to the Reuters news agency on Wednesday. By comparison, exports to the US grew at double-digit rates in each of the first two months.

According to Commerzbank economist Ralph Solveen, the sharp contraction in business in China is “still a late consequence of the lockdown measures, which were only eased at the end of last year”. He expects demand from the People’s Republic to pick up again in the coming months.

The German economy’s trade with China had risen to a record level in 2022 – despite all political warnings of excessive dependence. The bilateral trade volume rose by 21 percent to around €298 billion. China thus remained Germany’s most important trading partner for the seventh year in a row. rtr/jul

Benz, Beck’s, Beckenbauer. These are the words that many Chinese associate with Germany. Oliver Lutz Radtke describes the general image of Germans in China as very positive. Not as dazzling and charming as the French and Italians, but more reliable. The 46-year-old has been in Beijing since November 2022 as Chief Representative China of the Heinrich Boell Foundation. In his new role, he wants to mediate and strengthen Chinese civil society.

Young people’s fears about the future, the question of the good life, different values from those of their grandparents’ generation – Radtke observes these debates in China as well as in Germany. People may be moving in different political contexts, but their concerns and fears are the same. Radtke wishes that social groups from individual countries could meet more closely at different levels.

In his new position at the Heinrich Boell Foundation, Radtke sees himself primarily as a mediator. He wants to take the major transformation debates on topics such as renewable energies and climate neutrality from Germany and Europe to China. The task of the century, climate change, can only be solved together, says Radtke. It is also important to him to find contacts in China, exchange ideas with them about Chinese efforts and derive recommendations from them on cooperating with Germany.

Radtke feels comfortable at the crossroads of German-Chinese understanding with all its tensions and frictions. He hopes that German interest in China will not decline. Radtke sees a responsibility for society as a whole not to relegate knowledge of China to a small circle of experts but to make it accessible to schoolchildren, students and professionals at all levels.

Oliver Radtke sees support for Chinese civil society as another major task of the Green-affiliated Heinrich Boell Foundation in China. “I admire the organizations we support,” he says. “They are trying to do their best under sometimes very difficult conditions on issues like environmental protection, biodiversity and climate change.” For him, a large part of the country’s innovative power comes from civil society.

Radtke moved to China at the end of 2022 – exactly at the final phase of the zero-Covid policy and the mass protests taking place at the time. He himself had to go into quarantine twice in a row: “The first time was an important, but fortunately time-limited, look for me at what the zero-Covid policy looked like in the country, especially in the last year.”

Before becoming Chief Representative China of the Heinrich Boell Foundation, Radtke headed the China program of the Robert Bosch Stiftung. He regularly traveled to China and organized exchange programs for judges, journalists, cultural workers, and NGOs. In addition, he was the German Secretary General of the German-Chinese Dialogue Forum for three years. Radtke is the author of three books. Maximilian Senff

Li Song was appointed as China’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations and other international organizations in Vienna, replacing Wang Qun.

Chen Ruifeng is the new head of the National Religious Affairs Authority (NRAA). He succeeds Cui Maohu, who was removed from office a few days ago. The reason, according to official reports, was suspicion of serious violations of party discipline and the country’s laws – the usual euphemism for corruption. The 57-year-old from Yunnan is already the third high-ranking official to be removed since the end of the National People’s Congress.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

When artist Duan Sixing reaches for his tools, an ordinary piece of wood is transformed into an artistic piece of furniture, sculpture or wall ornament. Three-dimensional forms emerge from an inconspicuous surface, a process that often takes months. Duan’s studio is located in southwestern Yunnan – in Jianchuan County, in the autonomous prefecture of Dali. The region has a long history of wood carving, dating back to the Tang and Song dynasties (618-907 and 960-1279). Now a museum for the art form is being built there.

Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow mainly leaves losers. Ukraine is the most bitter case, writes Michael Radunksi in his review of the summit. For the victim of the war of aggression, there is still no tangible prospect for peace on acceptable terms.

This is also evident from the final paper of the meeting, which Frank Sieren reviewed for us. While there is mention of peace, what it would actually mean: Russia is allowed to keep its conquered territories. After all, according to Moscow’s understanding, they belong to Russian territory.

But Russia is no winner either. The paper is rife with humiliations for the so-powerful Kremlin leader. Xi exploits his strong position to subject Putin to unacceptable positions. Xi lets Putin clearly feel the Chinese dominance.

However, neither has China gained much. While Xi is clearly the stronger partner, his visit entangled him even deeper in the war and raised expectations of a Chinese role in the peace process. In Western eyes, China is simultaneously moving very close to being an outcast. Although the Beijing-Moscow axis has been strengthened, Xi has also further tied himself to the potential loser Putin. But it is too late for him to back out.

A breakthrough in Xi’s Covid policy also comes a bit late: China approved its first mRNA vaccine – a domestic creation, developed at great speed and with a huge research effort. It would have been quicker to import the vaccine in time from its important trading partner Germany, writes Joern Petring. And China could then still have built up its own mRNA industry. But what matters most to Xi, just like in his dealings with Russia, is breaking away from the West.

From a political perspective, Xi Jinping’s visit to Russia was conservative: no impetus for Ukraine but continued close, strategic partnership with Vladimir Putin. Economically, China is coolly exploiting the effect of Western sanctions and deepening Russia’s dependence on the People’s Republic. In the future, Beijing can be expected to make not only economic but also increasingly strategic demands on Moscow.

Politically, Xi’s visit raised hopes among some observers for diplomatic progress in the Ukraine war. China had presented a 12-point paper on a political solution in early March and recently scored points elsewhere as a mediator – namely with an agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Moreover, Xi had announced his visit to Moscow as a journey of peace.

But as a possible peacemaker in the Ukraine war, Xi disappointed such hopes in Moscow almost across the board. Apart from the joint rejection of a nuclear war, nothing was achieved from the Western point of view: no halt to the hostilities and also no new impetus with regard to his own 12-point paper.

What’s more, while Xi and Putin celebrated their friendship together under golden chandeliers, the Ukrainian president in Kyiv was left only with the prospect of a possible timely phone call from Xi. He welcomed even that vague announcement. Zelenskiy knows that Xi could exert influence on Putin if he wanted to and must therefore leave no stone unturned.

Economically, according to the Kremlin, two agreements, in particular, were signed, as well as several small projects in areas such as forestry, soybeans, television and industry in Russia’s Far East. Almost devoutly, Putin assured that his country would continue to satisfy even China’s ever-increasing hunger for energy. Record deliveries are already being reported through the “Power of Siberia” pipeline. In addition, Putin is said to have proposed a new pipeline through Mongolia during the talks.

In Moscow, it became clear how coolly Xi monetizes Russian dependence – through enormous discounts, increasing supplies of raw materials, or simply hard currency. Two-thirds of bilateral trade is already conducted in rubles or yuan, he said. Putin also promised to settle Russia’s global commodity shipments in yuan in the future. And so China benefits even where it is not directly involved in trade.

During the meetings in Moscow, it was noticeable that there was rather little of the enthusiasm of February 2022 – when Xi and Putin proclaimed their boundless friendship in Beijing. Both reaffirmed their close strategic partnership in an almost sober and matter-of-fact manner.

Nevertheless: Politically, Xi reaffirmed in Moscow his great closeness to Putin. China’s head of state continues to hold rock-solid to a man who would be arrested immediately on the basis of an international arrest warrant in 123 countries of the world (all of which recognize the International Criminal Court ICC). Xi praises Putin’s strong leadership in Moscow and invites his dear friend to Beijing for a return visit. So much, by the way, for respecting international law. It must therefore be thought-provoking when Xi announces in Moscow that China is ready to “watch over the world order based on international law” together with Russia.

Xi stands by Putin and accepts that his image will be damaged, especially in Europe – because China cannot win anything in the USA at the moment anyway.

But it is probably only a matter of time before Xi demands more from Putin in return for his support than just discounts and raw materials. Geopolitically, the focus is likely to shift to regions where Russia is still the leader, but China is increasingly making its own demands: the Arctic, Central Asia, or Russia’s historically good relationship with India, which is a thorn in China’s side.

Joint final declarations in politics are always the result of a struggle for power. The joint declaration of the Xi-Putin summit at the beginning of the week is a closing of ranks against the West, but above all, a shift in the balance of power in favor of China – and in the direction of a peaceful solution to the conflict. The West wants that, too. But not at the price Beijing is offering: A cease-fire and talks without Putin having to withdraw from the occupied Ukrainian territories. Overall, the paper documents how weak Russia’s position is vis-à-vis China after the unfavorable course of the war.

Xi is forcing Putin to take positions that he does not actually want to take. In doing so, he shows his power and criticizes him at the same time. The West’s wish is for Xi to distance himself from Putin and publicly criticize his war of aggression, even break with him. The Chinese way of criticism, however, is more indirect. Xi’s intention is to get Putin to relent without destroying the partnership with its neighbor, with whom China shares a 4,200-kilometer border. Beijing has a clear goal: The war should end quickly – and Ukraine, with which China had close relations before the invasion, should neither be subjugated by Putin nor join NATO.

Key takeaways from the brief joint statement at the conclusion of the meeting:

First point for Beijing: criticism against encroachment on foreign territory. “The purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter must be observed and international law must be respected,” the statement reads at the very beginning. Article 2, item 4 of the Charter prohibits member states from “using in their international relations any threat or use of force directed against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” Clearly, Putin has not complied and is being urged by Beijing to now relent.

Second point for Beijing: China cements its leadership role. “The Russian side speaks positively about China’s objective and impartial position in the Ukraine war,” is the next position. Putin is forced to concede here: What China says is right. And China wants peace. Humiliating for Putin.

One point for both against the West: “No country may seek military and political advantages that are harmful to a country’s legitimate interests,” the statement continues. This is an important principle, but also an iridescent one that everyone can interpret for themselves. China here means the US with NATO, but also Russia itself. Putin probably sees only NATO in this and can sell this at home as a success. Both can claim a point for themselves here.

Third point for Beijing: The very next sentence is about peace. “Russia reiterates its commitment to resume peace negotiations as soon as possible, which China welcomes.” China is forcing Russia to make this commitment. But both are also saying with this: It is not up to us that there are no peace negotiations yet.

Fourth point for Beijing: Russia “welcomes the constructive proposals in China’s position on the peaceful resolution of the Ukraine crisis” reads the next position. Another humiliation. And then the man who started a war must also concede: “Responsible dialogue is the best way to find appropriate solutions.” And not war.

One point for Putin: “Both sides reject any unilateral sanctions not decided by the UN Security Council.” That, after all, is a clear point for Putin. After all, the sanctions against Russia were not confirmed by the UN Security Council but were imposed by the West on its own. The majority of the world does not support the sanctions.

China has approved its first mRNA vaccine after a long wait. On Wednesday, the Chinese company CSPC Pharmaceutical announced on the Hong Kong stock exchange that it had received emergency approval for its mRNA vaccine developed against the Omicron variant. The company, based in Shijiazhuang, Hebei province, did not initially provide details on when the vaccine would be used in Chinese vaccination centers and hospitals.

China had rapidly developed several of its own vaccines since the outbreak of the pandemic. However, these were conventional inactivated vaccines, which tend to be less effective than modern mRNA vaccines. In Germany, by contrast, BioNTech’s mRNA vaccine was already available in the first major vaccination campaign in December 2020, and it eventually took China almost two and a half years to catch up.

After Beijing finally capitulated to the Omicron variant in December 2022 and practically threw its strict Covid measures overboard, a huge Covid wave swept through the country. Although the official death toll is still only in the tens of thousands, model calculations suggest at least one million victims. If an effective mRNA vaccine had been approved earlier, it could have been widely inoculated as a booster. Human lives could have been saved in this way.

But it was more important for Beijing not to be dependent on foreign countries. Even the new Chinese Premier Li Qiang, a close confidant of Xi, could not change this. As the then Shanghai party chief, he reacted quickly in the spring of 2020 and allowed the Chinese corporation Fosun to sign a contract with BioNTech. Fosun was to take over the production and distribution of BioNTech’s vaccine in China. More than a year later, the party newspaper Global Times reported on a video conference between Li and BioNTech founder Uğur Şahin. It was “very likely” that BioNTech would soon be approved in China, the article said. But then the central government apparently intervened. The approval failed to materialize.

It is true that at least German citizens living in China are now allowed to be vaccinated with BioNTech. In retrospect, however, this was probably primarily a gesture of goodwill. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was able to announce the good news during his trip to China at the end of last year, and observers at the time saw a chance that, with some delay, there could also be a broad market launch.

In addition to CSPC, at least three other Chinese companies are researching their own mRNA vaccines. Suzhou Abogen Biosciences received emergency approval in Indonesia last year – though still not in China. In addition, Stemirna Therapeutics of Shanghai and Cansino Biologics of Tianjin began initial human testing last year. If these companies also follow suit soon with approvals in their own countries, there will probably be no room left for foreign suppliers like BioNTech. Joern Petring

Federal Research Minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger wants to expand cooperation with Taiwan in semiconductor, hydrogen and battery research. “Germany is very strong in basic research, Taiwan very strong in application and transfer,” the FDP politician said Wednesday at the end of her two-day visit to Taipei. Asked about possible plans of the semiconductor manufacturer TSMC, she referred to the responsibility of the Ministry for Economic Affairs and the Chancellery. But of course, she said, there was a great deal of interest in this. There is a desire to build a chip infrastructure in Germany and Europe, she said. “Taiwan can be a role model and partner in this.”

At her press conference, Stark-Watzinger again rejected Chinese criticism of the visit to Taiwan, which Beijing regards as a breakaway province. She said she was conducting the talks as a specialist minister and that “all relevant players” had been involved. “The trip to Taiwan is within the framework of the German government’s ‘one China’ policy,” she stressed. The visit had been prepared with the Chancellery and the Foreign Ministry, she said. Cooperation at the technical level should become the norm in the future, she said. On Tuesday, the German government had reacted calmly to Chinese criticism of the visit.

There is worldwide competition for more technological sovereignty, Stark-Watzinger explained her trip. Taiwan has the most modern technology, but at the same time is an open and free society, as well as a constitutional state. For this reason, she said, one could also discuss issues in the field of artificial intelligence with Taiwan as a value partner. rtr/ck

There is renewed excitement about Huawei: Telekom and the Chinese network supplier are said to have agreed in 2019 that Huawei would supply Germany with network components containing American parts as a precautionary measure – before US sanctions against the company take effect. Telekom is then said to have stored the parts for later use. This is reported by Handelsblatt, which has the contract from back then.

At the very least, this contract goes against the spirit of the US sanctions, which were intended to make it difficult for Huawei to do business internationally. This is a delicate operation for a partly state-owned company in the current trade policy mood.

At the time, however, the agreement was presumably perfectly legal. The aim was to secure Telekom’s supply of key parts from its long-time partner Huawei, which the company values for its reliability. Peter Altmaier, the Economy Minister at the time, was not averse to doing business with Huawei. The US sanctions, in turn, had been decided by then-US President Donald Trump, whose policies were always suspected of not being entirely rational.

Four years later, the situation is very different. Today, the sanctions policy of the Trump era is being continued by a more credible president, Joe Biden. Authoritarian Russia, which is allied with China, has proven to be aggressive and wants to blackmail Western Europe with gas supplies. In Germany, two coalition partners who are decidedly critical of China have been sitting at the cabinet table since the change of government.

Meanwhile, the EU recommended that its members rely on European rather than Chinese suppliers for network expansion. The agreement to stockpile electronics with potentially sanctioned US components looks suspicious from this perspective. Huawei itself presents the agreements with its customers as routine procedures. It is important for the company to be able to deliver promised parts. However, Huawei cannot comment on specific agreements with customers in this area for contractual reasons. fin

The report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) presented on Monday came about only after a hard struggle over content, goals and wording. This is the result of extensive research by Climate.Table. The precise wording in the “Summary for Policymakers” (SPM) to the synthesis report of the 6th IPCC report is extremely important. The report “summarizes the state of knowledge on climate change,” and its words are now considered scientifically and politically approved – and thus form the basis of global climate policy. One of the countries that repeatedly caused discussion at the conference to finalize the text in Interlaken, Switzerland, was China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

China, for example, was unable to accept the creation of a new global climate target for 2035: Emissions of all greenhouse gases are to be reduced by 60 percent by then and minus 65 percent for CO2. China resisted mentioning a concrete figure, as insiders confirm to Climate.Table. After much back and forth, it was removed from the running text – and moved to a separate table. However, this is so prominently placed that the intervention is more of an own goal. Officially, China plans to peak its emissions in 2030. By 2060, the country wants to become climate neutral.

China also insisted on the wording that the Paris climate agreement had been adopted “under the Framework Convention on Climate Change”. This is a sign that China continues to insist on the different responsibilities between old and new industrialized countries – and that China continues to see itself as a developing country, which means that it can defend itself against possible demands, for example, in the area of climate financing. Basically, the struggle for the report revealed the well-known front positions in global climate protection: The EU, USA and Japan are pushing for far-reaching formulations in principle – China, India and Saudi Arabia are leading the blockade. bpo/ck

Compared to the first two months of 2022, Germany’s exports to the People’s Republic slumped by more than eleven percent to €15.2 billion in January and February. This is according to preliminary data from the Federal Statistical Office, which was available to the Reuters news agency on Wednesday. By comparison, exports to the US grew at double-digit rates in each of the first two months.

According to Commerzbank economist Ralph Solveen, the sharp contraction in business in China is “still a late consequence of the lockdown measures, which were only eased at the end of last year”. He expects demand from the People’s Republic to pick up again in the coming months.

The German economy’s trade with China had risen to a record level in 2022 – despite all political warnings of excessive dependence. The bilateral trade volume rose by 21 percent to around €298 billion. China thus remained Germany’s most important trading partner for the seventh year in a row. rtr/jul

Benz, Beck’s, Beckenbauer. These are the words that many Chinese associate with Germany. Oliver Lutz Radtke describes the general image of Germans in China as very positive. Not as dazzling and charming as the French and Italians, but more reliable. The 46-year-old has been in Beijing since November 2022 as Chief Representative China of the Heinrich Boell Foundation. In his new role, he wants to mediate and strengthen Chinese civil society.

Young people’s fears about the future, the question of the good life, different values from those of their grandparents’ generation – Radtke observes these debates in China as well as in Germany. People may be moving in different political contexts, but their concerns and fears are the same. Radtke wishes that social groups from individual countries could meet more closely at different levels.

In his new position at the Heinrich Boell Foundation, Radtke sees himself primarily as a mediator. He wants to take the major transformation debates on topics such as renewable energies and climate neutrality from Germany and Europe to China. The task of the century, climate change, can only be solved together, says Radtke. It is also important to him to find contacts in China, exchange ideas with them about Chinese efforts and derive recommendations from them on cooperating with Germany.

Radtke feels comfortable at the crossroads of German-Chinese understanding with all its tensions and frictions. He hopes that German interest in China will not decline. Radtke sees a responsibility for society as a whole not to relegate knowledge of China to a small circle of experts but to make it accessible to schoolchildren, students and professionals at all levels.

Oliver Radtke sees support for Chinese civil society as another major task of the Green-affiliated Heinrich Boell Foundation in China. “I admire the organizations we support,” he says. “They are trying to do their best under sometimes very difficult conditions on issues like environmental protection, biodiversity and climate change.” For him, a large part of the country’s innovative power comes from civil society.

Radtke moved to China at the end of 2022 – exactly at the final phase of the zero-Covid policy and the mass protests taking place at the time. He himself had to go into quarantine twice in a row: “The first time was an important, but fortunately time-limited, look for me at what the zero-Covid policy looked like in the country, especially in the last year.”

Before becoming Chief Representative China of the Heinrich Boell Foundation, Radtke headed the China program of the Robert Bosch Stiftung. He regularly traveled to China and organized exchange programs for judges, journalists, cultural workers, and NGOs. In addition, he was the German Secretary General of the German-Chinese Dialogue Forum for three years. Radtke is the author of three books. Maximilian Senff

Li Song was appointed as China’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations and other international organizations in Vienna, replacing Wang Qun.

Chen Ruifeng is the new head of the National Religious Affairs Authority (NRAA). He succeeds Cui Maohu, who was removed from office a few days ago. The reason, according to official reports, was suspicion of serious violations of party discipline and the country’s laws – the usual euphemism for corruption. The 57-year-old from Yunnan is already the third high-ranking official to be removed since the end of the National People’s Congress.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

When artist Duan Sixing reaches for his tools, an ordinary piece of wood is transformed into an artistic piece of furniture, sculpture or wall ornament. Three-dimensional forms emerge from an inconspicuous surface, a process that often takes months. Duan’s studio is located in southwestern Yunnan – in Jianchuan County, in the autonomous prefecture of Dali. The region has a long history of wood carving, dating back to the Tang and Song dynasties (618-907 and 960-1279). Now a museum for the art form is being built there.