Expats in China can rejoice: They may continue to benefit from tax breaks that make life in the People’s Republic financially sweeter for them. They can deduct school fees or rent expenses from their taxable income for at least another four years.

These benefits should have expired at the end of last year, but were extended by one year at the last minute. Now, the highest tax authority has announced that foreigners in the People’s Republic can breathe easier for even longer. Joern Petring explains the details of this good news.

Almost a year after the presentation of ChatGPT, the Chinese government has granted four Chinese tech companies permission to make their chatbots available to the public as well. Felix Lee analyzes why this has taken such a sheer eternity in the global race for dominance in the field of artificial intelligence: The incompatibility between seamless control and the unpredictability of modern AI is a huge dilemma for Beijing.

And he explains why the obsession with control not only weakens the country: When it comes to citizens’ data – the core AI resource – a lack of qualms is a real competitive advantage.

German companies and expats have expressed relief at the extension of tax benefits in China. A corresponding announcement by the highest tax authority on 18 August shows that, if contracts are drawn up correctly, rent or school fees, for instance, will still not have to be included in taxable income. This significantly reduces the tax burden.

“The abolition of tax relief would have made secondments noticeably more expensive for companies, which would certainly have led to a further decrease in foreign employees at a time of high cost pressure,” Jens Hildebrandt, executive board member of the German Chamber of Commerce (AHK) in Beijing, told China.Table. Companies and expats alike are relieved that the status quo has been maintained.

Approval also came from the European Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber said it had lobbied for the matter at all levels. The continuation of the tax exemption could help stop the exodus of foreign talent that has been taking place in recent years, the Chamber said. The exemption is “welcome news for families who have decided to come to or stay in China,” it said.

The individual income tax benefits for foreigners had long been uncertain. They were originally scheduled to expire last year, but were extended for another year until the end of 2023, thanks in part to lobbying by the chambers.

However, the decision was made at the last minute at the turn of the year, which caused great uncertainty among many companies. Now, Beijing did not keep everyone in suspense for that long and announced the extension more than four months before they were set to end. This time, the regulation was not just extended for a single year, but for four years.

The tax savings from this special tax rule are considerable, as the consulting firm Dezan Shira & Associates points out in an analysis. Foreign employees can save “a fortune on taxes.” One example cited is the high fees for private schools in China, which can amount to 200,000 to even 350,000 yuan per year in Shanghai and Beijing. By comparison, according to Dezan Shira, “normal” Chinese tax law stipulates that only 1,000 yuan per month can be deducted per child. For rent, the maximum is 1,500 yuan per month.

Foreigners, on the other hand, can deduct the full cost in many cases thanks to the special rule, as long as the total is a “reasonable” amount and a corresponding invoice or other proof of payment can be presented, explains Dezan Shira. How much a “reasonable amount” is varies from city to city. In practice, approximately 30 to 35 percent of a monthly salary can be considered to fall under the tax relief.

Expatriates may deduct:

The Ministry of Finance has also announced plans to extend another beneficial regulation. This means that the annual bonus will remain subject only to a reduced tax rate. According to this regulation, individual income tax (IIT) is calculated separately for one-time annual bonuses and is not taxed together with total income, thus avoiding the consequences of tax progression. This rule also applies to Chinese employees.

Chamber head Hildebrandt generally observes a steady improvement in the general conditions since the end of the pandemic. “A lot has already happened. Visas are being issued quickly and there are enough flight connections at reasonable prices,” Hildebrandt said. One obstacle to attracting expatriates, however, remains China’s tarnished image, which requires more convincing on the part of companies, he said.

The robots that greeted visitors at the World Artificial Intelligence Conference (WAIC) in Shanghai in early July were not really impressive. The human-like machines can toss balls to each other and dance to traditional Chinese music. They are even used as service staff in some restaurants in China.

But if you asked them more complex questions, they only gave standardized answers on the level of Alexa or Siri at best, nowhere near ChatGPT. Complex language models were actually not yet integrated into these dancing robots. This has a specific reason: Chatbots like ChatGPT have not yet been officially approved in China. Accordingly, their use was not yet permitted.

Yet ChatGPT is also the dominant topic among Chinese programmers. But only those who bypass China’s great firewall via VPN access can use the text-based dialog system from the United States. The Chinese counterparts, such as Ernie Bot from Baidu or Alibaba’s Tongyi Qianwen, have so far only been available to testers in China. The same applies to the product range of AI and facial recognition software company SenseTime.

Only yesterday (Thursday), the Chinese government granted permission to four Chinese tech companies to make their chatbots available to the public for the first time. The release thus came almost a year after US-based Open AI presented ChatGPT. In digital development terms, that is a sheer eternity.

The reason for the delay: The state leadership wanted to lay down clear rules for the use of generative AI. Above all, it wanted to clarify responsibilities in advance. The communist leadership fears nothing more than losing control over new media and technologies.

The incompatibility between complete control and the unpredictability of modern AI is a huge dilemma for them. On the one hand, it already presented a three-stage strategy in 2017 with the so-called Next-Generation Artificial Intelligence Plan. By 2020, China was supposed to be at least on par with the United States, by 2025, it was supposed to have surpassed the United States, and finally, by 2030, it was supposed to be the global leader. At least China failed to achieve the first goal.

On the other hand, the communist leadership fears even more than Western governments that too much false information is circulating on the internet – rumors, accounts or information and opinions that could even be turned against them.

Since August 15, the powerful Cyberspace Administration of China has drafted a law to this effect. It contains 24 articles. They apply only “provisionally.” This is because the government is already working on an even more comprehensive law, which is likely to enter into force as early as the beginning of next year.

The core of the regulations currently in effect is the question of responsibilities. And these clearly lie with the tech companies.

This makes it clear that the Chinese language models will not provide any politically relevant answers. The software here is presumably throttled in a technically similar way to what OpenAI has done in the West with sensitive topics such as racism. The model refuses to answer corresponding questions.

So it will be hard to discuss the question of the advantages and disadvantages of a communist system with Ernie. The same is probably true for other ideological questions, for instance, political hotspots like Taiwan or history interpretation. If something does slip through, the provider will be in trouble.

China is hardly a viable market for US tech companies such as OpenAI, Microsoft, Google or Meta, and basically all other foreign AI providers. But this seems to be precisely the intention of the Chinese leadership.

As much as the obsession with control may temporarily weaken China in the global AI race, Beijing’s overarching goal is to develop autonomous AI technology independent of Western patents.

The sooner AI is tamed in its early stages, the faster China may set standards for AI development in other parts of the world. At least, that’s the assumption. The German government’s foreign trade agency, Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI), notes on its website that the regulations “are among the first such AI regulations in the world.”

There is another reason why China should not be written off in AI development. China has few qualms about data protection. In no other country are private companies and government institutions allowed to collect and store as much of their citizens’ data and share it with each other as in the People’s Republic.

This is a significant advantage over the West. Data is the key raw material for AI. China’s Big Data is already felt in application-related AI in the industry. Chinese companies are already at the forefront of autonomous driving development. These are less creative, more narrowly focused applications where Chinese developers can play to their strengths.

“China is not on the cutting edge when it comes to generative AI,” says Tim Ruehlig, geopolitics and technology expert focusing on China at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP). But it is when it comes to autonomous vehicles. Because China has two advantages in this area: Its data-gathering frenzy and its dense network. As Rühlig says, “It’s not just data and algorithms that are needed, but also good network coverage.”

One year ago yesterday, the UN report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang was published. Marking the anniversary, Amnesty International called the report a “grave reminder of the need to hold China to account for crimes against humanity.” The human rights organization called the international community’s response to the report “woefully inadequate.”

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, published the report shortly before midnight on the last day of her term. It was the first UN report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang. The Chinese government had attempted to prevent the publication until the very end.

The report states, among other things, that actions of the Chinese government in Xinjiang “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.” The report avoids the term “genocide,” used by the US government and several parliaments of democratic states, but very specifically addresses allegations of forced labor, forced sterilizations, and torture. Beijing was allowed to respond to the report in an annex. Over 131 pages – almost three times as long as the UN report itself – the Chinese government states that “so-called assessment distorts China’s laws and policies” and smears it.

The report’s publication had been postponed repeatedly for more than a year. Bachelet had justified the latest delay by saying that she wanted to integrate the impressions of her Xinjiang visit at the end of May into the document. However, the trip to Xinjiang was not an official investigation and was severely limited in scope. jul

China’s publication of a new standard map of the People’s Republic has caused considerable anger among neighboring states. The map, published by the Ministry of Natural Resources, designates, among other things, an entire state of India and the coastal waters of Malaysia as Chinese territory. The map is intended for use in universities and schools or by publishers – in other words, it is clearly an official map.

The new map represents an insult to India in particular. At the recent BRICS summit in Johannesburg, President Xi Jinping discussed with Prime Minister Narendra Modi how to reduce the decades-old tensions along the 3,500-kilometer-long unmarked Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the rough terrain of the Himalayas. Many had interpreted this as a thaw. But the new map now shows the state of Arunachal Pradesh, long claimed by China, as a separate territory with a new name of “Zangnan” (藏南), meaning southern Tibet. The mountainous region of Aksai Chin in western Tibet is also designated as part of China. Although China conquered the region in the 1962 border war, India has never renounced its claim.

On Thursday, it also became known that Xi will likely not attend the G20 summit in India – another affront. Satellite images from the Himalayas also reveal that China is building several bunkers on its side of the LAC to protect itself from Indian attacks. In 2020, fighting last broke out near Aksai Chin, leaving two dozen people dead on the LAC, and in 2022, troops from both sides attacked each other with batons and other equipment.

Neighboring states reacted with outrage to the map. “Absurd claims do not lead to other people’s territories becoming yours,” commented Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar. “Simply presenting maps with parts of India doesn’t mean anything.”

The Philippines, Malaysia and Taiwan have also rejected the map. Malaysia lodged a diplomatic protest against China, saying the map shows parts of the country’s exclusive economic zone off the Borneo island provinces of Sabah and Sarawak as Chinese. On Thursday, China’s foreign office spokesman Wang Wenbin coldly called for all parties to view the map in an “objective and rational” manner. Whatever he means by that, Beijing is unlikely to have made friends with the map. ck

The number of candidates for the position of outgoing Asia Director Gunnar Wiegand at the European External Action Service (EEAS) is shrinking. In the closer race for the position are Wiegand’s current deputy, Paola Pampaloni, Swedish diplomat Niclas Kvarnström and Latvian diplomat Baiba Braže, as confirmed by EU sources on Thursday. Accordingly, a decision on the appointment is to be made by mid-September.

While Pampaloni would continue the EEAS’s existing China policy, Kvarnström and Braže would presumably represent changes in the EU’s approach toward Beijing. Kvarnström currently heads the Asia-Pacific department at the Swedish Foreign Office and could bring a greater focus to the EEAS’s Indo-Pacific agenda. Braže was deputy secretary-general at NATO until July and could thus bring a stronger security policy angle. She has not previously worked with an Asia focus. ari

On Thursday, several Chinese metropolises announced measures to stabilize the teetering real estate market. Shortly before, Guangzhou was the first city to announce that it would relax previously applicable rules for granting mortgages.

On Thursday, the central bank and financial regulator announced plans to cut interest rates on existing mortgage loans for first-time home buyers starting Sept. 25. Simultaneously, several major cities – including Beijing, Shenzhen and Wuhan – announced plans to relax previously applicable mortgage lending rules. Homebuyers can now benefit from preferential loans regardless of their previous creditworthiness. In turn, the eastern province of Jiangsu wants to lower the down payment rate for first-time homebuyers. Critics believe the responses to the rampant real estate crisis are overdue.

China’s mortgage loans totaled 38.6 trillion yuan (4.9 trillion euros) at the end of June. This represents about 17 percent of banks’ total loan portfolio. The cut in interest rates is likely to increase pressure on banks’ profit margins. Three of China’s largest financial institutions announced in their interim financial statements that their net interest margins – a key benchmark for profitability – had already fallen in the past second quarter.

Also on Thursday, ailing real estate group Evergrande announced it would not be able to make payments on investment products this month due to liquidity problems. The company’s shares dropped to valuations in the cents range as recently as Monday. rtr / jul

In music, solo performances of instruments such as Erhu (二胡) or Pipa (琵琶) are still purely Chinese. But when it comes to orchestra, it’s another story. Traditionally, musicians in a group instrumental show play the same notes simultaneously. In the middle of last century, however, the Western concept of harmony was borrowed. Ancient ballads were re-arranged and new pieces were created using Western composing techniques. In addition, while the orchestras are composed of almost all traditional instruments, they also use Western double basses because no Chinese instrument can provide the music with a solid underlying support.

In dancing, performers of the so-called Chinese dance are trained in the Western classical way. The so-called Chinese dance works’ only differences from ballet are, number one: They tell Chinese stories; number two: female dancers don’t stand on their toes.

Classical Chinese fine artworks were rarely painted with a single perspective, if perspective was employed at all. Now, few stick to the old way. Students applying for programs of Chinese painting in schools of fine arts are also tested on Western-style sketches as well as skills using Chinese inks and brushes.

Of all the major traditional Chinese art forms still in existence today, the West had the least influence on calligraphy and Xiqu (戏曲), traditional Chinese opera.

Xiqu stands out remarkably to stay almost totally immune to Western influence. Some reforms were conducted regarding dramaturgy, the orchestra’s composition, performers’ physical movements and scene design, especially for the propaganda Peking Opera “Model Works” which dominated all Chinese stages during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). But the changes were later on all abandoned, except for some remnants in scene design. The stylized movements, the dance, the speech, and most importantly, the singing, are pretty much the same as in the old days.

Xiqu does not just mean Peking Opera. Almost all the 34 provinces have at least one local form of opera, some provinces have more than one, and some local Xiqu forms, like the Peking Opera, also have cross-provincial, even national influence, such as Yueju (越剧), which originated from Zhejiang, and Yuju (豫剧), from Henan. An estimated total of 150 forms of Xiqu are performed regularly in different parts of China.

Critics first claimed in the 1920s and 1930s that the “outdated” art form would go naturally into historical dustbins as China modernized itself.

The Republic of China was just founded on the ruins of the decrepit Qing dynasty. Intellectuals and revolutionists’ reflections on the aggression and humiliation the Chinese experienced since the Opium War (1840-1842) led to some radical ideas on how to make China stronger, which included the introduction of communism and revamping the Chinese culture. Critical voices against Xiqu included such big names as the great writer Lu Xun (鲁迅1881 – 1936), a famously scathing critic of traditional Chinese culture.

The next round of pessimism over Xiqu came in the 1980s. Emerging from the insane Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), when a nation of 800 million saw only 15 “revolutionary Peking operas” and about 20 films, the country was again on the path of modernization. In parallel to political thawing and economic reforms, hundreds of new and formerly banned films – both Chinese and foreign – television, pop music and other forms of the performing arts swept over a revitalized nation.

After being banned for over ten years, traditional Chinese operas were allowed to be performed again. But after an initial euphoria, their audience declined rapidly and sharply. It was assumed that only older people liked them and that Xiqu would die with these people. But the Chinese operas survived. They did not gain a large audience, but at least they gained a younger audience who came to appreciate the beauty of this purely Chinese gem. Today, more than 10,000 private troupes of different Xiqu forms are actively giving performances in the country, as compared to more than 100 groups for speaking drama.

Government support also plays a role. As the Chinese government gets richer, it also becomes keener to promote things representing the Chinese identity. The public funding goes mainly to the official Xiqu groups and Xiqu schools. Interestingly, but sadly, the image of Xiqu performers is less glamorous than that of artists of Western music. Children attending these opera schools are almost all from less wealthy families.

Still, the value of Chinese opera is recognized internationally. Kunqu (昆曲), the ancient, elegant opera form and prototype of all other Xiqu forms, including the Peking Opera, was put by UNESCO on the list of the Masterpieces of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, in 2001, and the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, in 2008.

In the Peony Pavilion, the most well-known Kunqu piece, the heroine Du Liniang croons at the scene in the spring garden: “A riot of deep purple and bright red, what pity on the ruins they overspread!” The days when traditional Chinese opera singers could cause a scene of riot are long gone, but the unique color and sound it contributes to humanity still shine on.

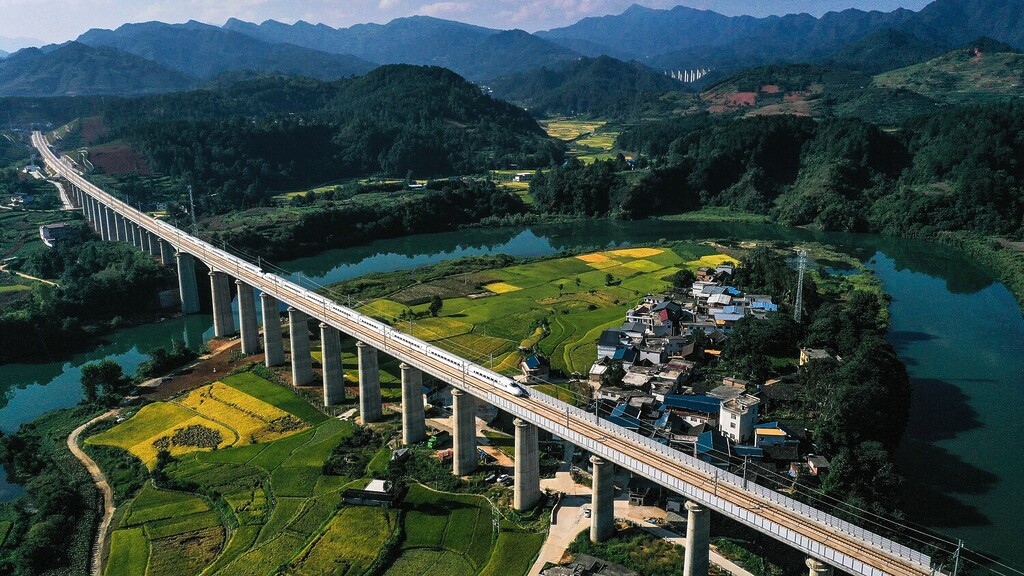

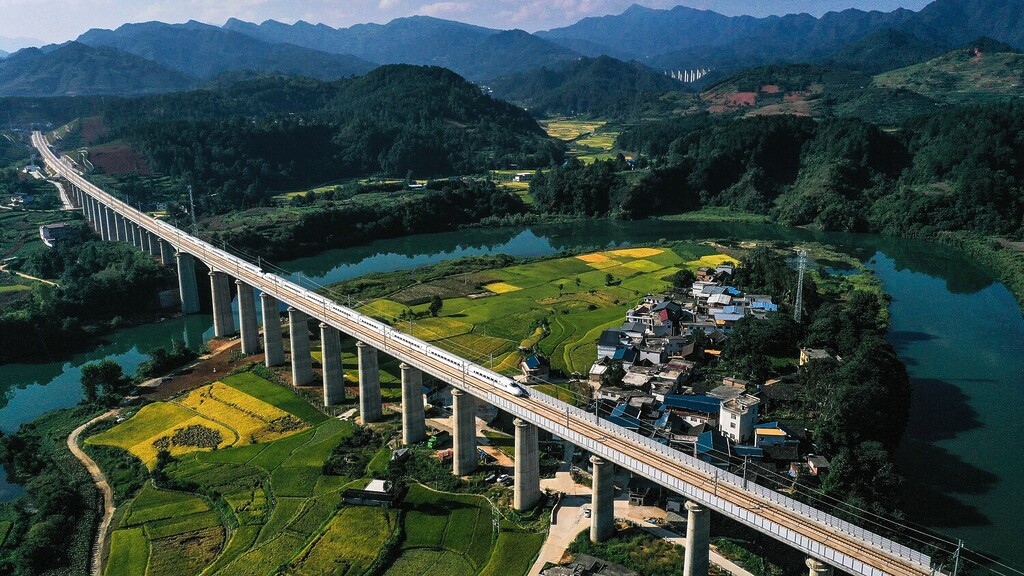

All sections of the new Guiyang-Nanning high-speed rail line have been in operation since Thursday. In numbers: 482 km of track, 148 switches, a top speed of 350 kilometers per hour. A small section of it is seen here from the air – near Duyun, the capital of Qiannan County in southwest China.

Expats in China can rejoice: They may continue to benefit from tax breaks that make life in the People’s Republic financially sweeter for them. They can deduct school fees or rent expenses from their taxable income for at least another four years.

These benefits should have expired at the end of last year, but were extended by one year at the last minute. Now, the highest tax authority has announced that foreigners in the People’s Republic can breathe easier for even longer. Joern Petring explains the details of this good news.

Almost a year after the presentation of ChatGPT, the Chinese government has granted four Chinese tech companies permission to make their chatbots available to the public as well. Felix Lee analyzes why this has taken such a sheer eternity in the global race for dominance in the field of artificial intelligence: The incompatibility between seamless control and the unpredictability of modern AI is a huge dilemma for Beijing.

And he explains why the obsession with control not only weakens the country: When it comes to citizens’ data – the core AI resource – a lack of qualms is a real competitive advantage.

German companies and expats have expressed relief at the extension of tax benefits in China. A corresponding announcement by the highest tax authority on 18 August shows that, if contracts are drawn up correctly, rent or school fees, for instance, will still not have to be included in taxable income. This significantly reduces the tax burden.

“The abolition of tax relief would have made secondments noticeably more expensive for companies, which would certainly have led to a further decrease in foreign employees at a time of high cost pressure,” Jens Hildebrandt, executive board member of the German Chamber of Commerce (AHK) in Beijing, told China.Table. Companies and expats alike are relieved that the status quo has been maintained.

Approval also came from the European Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber said it had lobbied for the matter at all levels. The continuation of the tax exemption could help stop the exodus of foreign talent that has been taking place in recent years, the Chamber said. The exemption is “welcome news for families who have decided to come to or stay in China,” it said.

The individual income tax benefits for foreigners had long been uncertain. They were originally scheduled to expire last year, but were extended for another year until the end of 2023, thanks in part to lobbying by the chambers.

However, the decision was made at the last minute at the turn of the year, which caused great uncertainty among many companies. Now, Beijing did not keep everyone in suspense for that long and announced the extension more than four months before they were set to end. This time, the regulation was not just extended for a single year, but for four years.

The tax savings from this special tax rule are considerable, as the consulting firm Dezan Shira & Associates points out in an analysis. Foreign employees can save “a fortune on taxes.” One example cited is the high fees for private schools in China, which can amount to 200,000 to even 350,000 yuan per year in Shanghai and Beijing. By comparison, according to Dezan Shira, “normal” Chinese tax law stipulates that only 1,000 yuan per month can be deducted per child. For rent, the maximum is 1,500 yuan per month.

Foreigners, on the other hand, can deduct the full cost in many cases thanks to the special rule, as long as the total is a “reasonable” amount and a corresponding invoice or other proof of payment can be presented, explains Dezan Shira. How much a “reasonable amount” is varies from city to city. In practice, approximately 30 to 35 percent of a monthly salary can be considered to fall under the tax relief.

Expatriates may deduct:

The Ministry of Finance has also announced plans to extend another beneficial regulation. This means that the annual bonus will remain subject only to a reduced tax rate. According to this regulation, individual income tax (IIT) is calculated separately for one-time annual bonuses and is not taxed together with total income, thus avoiding the consequences of tax progression. This rule also applies to Chinese employees.

Chamber head Hildebrandt generally observes a steady improvement in the general conditions since the end of the pandemic. “A lot has already happened. Visas are being issued quickly and there are enough flight connections at reasonable prices,” Hildebrandt said. One obstacle to attracting expatriates, however, remains China’s tarnished image, which requires more convincing on the part of companies, he said.

The robots that greeted visitors at the World Artificial Intelligence Conference (WAIC) in Shanghai in early July were not really impressive. The human-like machines can toss balls to each other and dance to traditional Chinese music. They are even used as service staff in some restaurants in China.

But if you asked them more complex questions, they only gave standardized answers on the level of Alexa or Siri at best, nowhere near ChatGPT. Complex language models were actually not yet integrated into these dancing robots. This has a specific reason: Chatbots like ChatGPT have not yet been officially approved in China. Accordingly, their use was not yet permitted.

Yet ChatGPT is also the dominant topic among Chinese programmers. But only those who bypass China’s great firewall via VPN access can use the text-based dialog system from the United States. The Chinese counterparts, such as Ernie Bot from Baidu or Alibaba’s Tongyi Qianwen, have so far only been available to testers in China. The same applies to the product range of AI and facial recognition software company SenseTime.

Only yesterday (Thursday), the Chinese government granted permission to four Chinese tech companies to make their chatbots available to the public for the first time. The release thus came almost a year after US-based Open AI presented ChatGPT. In digital development terms, that is a sheer eternity.

The reason for the delay: The state leadership wanted to lay down clear rules for the use of generative AI. Above all, it wanted to clarify responsibilities in advance. The communist leadership fears nothing more than losing control over new media and technologies.

The incompatibility between complete control and the unpredictability of modern AI is a huge dilemma for them. On the one hand, it already presented a three-stage strategy in 2017 with the so-called Next-Generation Artificial Intelligence Plan. By 2020, China was supposed to be at least on par with the United States, by 2025, it was supposed to have surpassed the United States, and finally, by 2030, it was supposed to be the global leader. At least China failed to achieve the first goal.

On the other hand, the communist leadership fears even more than Western governments that too much false information is circulating on the internet – rumors, accounts or information and opinions that could even be turned against them.

Since August 15, the powerful Cyberspace Administration of China has drafted a law to this effect. It contains 24 articles. They apply only “provisionally.” This is because the government is already working on an even more comprehensive law, which is likely to enter into force as early as the beginning of next year.

The core of the regulations currently in effect is the question of responsibilities. And these clearly lie with the tech companies.

This makes it clear that the Chinese language models will not provide any politically relevant answers. The software here is presumably throttled in a technically similar way to what OpenAI has done in the West with sensitive topics such as racism. The model refuses to answer corresponding questions.

So it will be hard to discuss the question of the advantages and disadvantages of a communist system with Ernie. The same is probably true for other ideological questions, for instance, political hotspots like Taiwan or history interpretation. If something does slip through, the provider will be in trouble.

China is hardly a viable market for US tech companies such as OpenAI, Microsoft, Google or Meta, and basically all other foreign AI providers. But this seems to be precisely the intention of the Chinese leadership.

As much as the obsession with control may temporarily weaken China in the global AI race, Beijing’s overarching goal is to develop autonomous AI technology independent of Western patents.

The sooner AI is tamed in its early stages, the faster China may set standards for AI development in other parts of the world. At least, that’s the assumption. The German government’s foreign trade agency, Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI), notes on its website that the regulations “are among the first such AI regulations in the world.”

There is another reason why China should not be written off in AI development. China has few qualms about data protection. In no other country are private companies and government institutions allowed to collect and store as much of their citizens’ data and share it with each other as in the People’s Republic.

This is a significant advantage over the West. Data is the key raw material for AI. China’s Big Data is already felt in application-related AI in the industry. Chinese companies are already at the forefront of autonomous driving development. These are less creative, more narrowly focused applications where Chinese developers can play to their strengths.

“China is not on the cutting edge when it comes to generative AI,” says Tim Ruehlig, geopolitics and technology expert focusing on China at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP). But it is when it comes to autonomous vehicles. Because China has two advantages in this area: Its data-gathering frenzy and its dense network. As Rühlig says, “It’s not just data and algorithms that are needed, but also good network coverage.”

One year ago yesterday, the UN report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang was published. Marking the anniversary, Amnesty International called the report a “grave reminder of the need to hold China to account for crimes against humanity.” The human rights organization called the international community’s response to the report “woefully inadequate.”

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, published the report shortly before midnight on the last day of her term. It was the first UN report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang. The Chinese government had attempted to prevent the publication until the very end.

The report states, among other things, that actions of the Chinese government in Xinjiang “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.” The report avoids the term “genocide,” used by the US government and several parliaments of democratic states, but very specifically addresses allegations of forced labor, forced sterilizations, and torture. Beijing was allowed to respond to the report in an annex. Over 131 pages – almost three times as long as the UN report itself – the Chinese government states that “so-called assessment distorts China’s laws and policies” and smears it.

The report’s publication had been postponed repeatedly for more than a year. Bachelet had justified the latest delay by saying that she wanted to integrate the impressions of her Xinjiang visit at the end of May into the document. However, the trip to Xinjiang was not an official investigation and was severely limited in scope. jul

China’s publication of a new standard map of the People’s Republic has caused considerable anger among neighboring states. The map, published by the Ministry of Natural Resources, designates, among other things, an entire state of India and the coastal waters of Malaysia as Chinese territory. The map is intended for use in universities and schools or by publishers – in other words, it is clearly an official map.

The new map represents an insult to India in particular. At the recent BRICS summit in Johannesburg, President Xi Jinping discussed with Prime Minister Narendra Modi how to reduce the decades-old tensions along the 3,500-kilometer-long unmarked Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the rough terrain of the Himalayas. Many had interpreted this as a thaw. But the new map now shows the state of Arunachal Pradesh, long claimed by China, as a separate territory with a new name of “Zangnan” (藏南), meaning southern Tibet. The mountainous region of Aksai Chin in western Tibet is also designated as part of China. Although China conquered the region in the 1962 border war, India has never renounced its claim.

On Thursday, it also became known that Xi will likely not attend the G20 summit in India – another affront. Satellite images from the Himalayas also reveal that China is building several bunkers on its side of the LAC to protect itself from Indian attacks. In 2020, fighting last broke out near Aksai Chin, leaving two dozen people dead on the LAC, and in 2022, troops from both sides attacked each other with batons and other equipment.

Neighboring states reacted with outrage to the map. “Absurd claims do not lead to other people’s territories becoming yours,” commented Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar. “Simply presenting maps with parts of India doesn’t mean anything.”

The Philippines, Malaysia and Taiwan have also rejected the map. Malaysia lodged a diplomatic protest against China, saying the map shows parts of the country’s exclusive economic zone off the Borneo island provinces of Sabah and Sarawak as Chinese. On Thursday, China’s foreign office spokesman Wang Wenbin coldly called for all parties to view the map in an “objective and rational” manner. Whatever he means by that, Beijing is unlikely to have made friends with the map. ck

The number of candidates for the position of outgoing Asia Director Gunnar Wiegand at the European External Action Service (EEAS) is shrinking. In the closer race for the position are Wiegand’s current deputy, Paola Pampaloni, Swedish diplomat Niclas Kvarnström and Latvian diplomat Baiba Braže, as confirmed by EU sources on Thursday. Accordingly, a decision on the appointment is to be made by mid-September.

While Pampaloni would continue the EEAS’s existing China policy, Kvarnström and Braže would presumably represent changes in the EU’s approach toward Beijing. Kvarnström currently heads the Asia-Pacific department at the Swedish Foreign Office and could bring a greater focus to the EEAS’s Indo-Pacific agenda. Braže was deputy secretary-general at NATO until July and could thus bring a stronger security policy angle. She has not previously worked with an Asia focus. ari

On Thursday, several Chinese metropolises announced measures to stabilize the teetering real estate market. Shortly before, Guangzhou was the first city to announce that it would relax previously applicable rules for granting mortgages.

On Thursday, the central bank and financial regulator announced plans to cut interest rates on existing mortgage loans for first-time home buyers starting Sept. 25. Simultaneously, several major cities – including Beijing, Shenzhen and Wuhan – announced plans to relax previously applicable mortgage lending rules. Homebuyers can now benefit from preferential loans regardless of their previous creditworthiness. In turn, the eastern province of Jiangsu wants to lower the down payment rate for first-time homebuyers. Critics believe the responses to the rampant real estate crisis are overdue.

China’s mortgage loans totaled 38.6 trillion yuan (4.9 trillion euros) at the end of June. This represents about 17 percent of banks’ total loan portfolio. The cut in interest rates is likely to increase pressure on banks’ profit margins. Three of China’s largest financial institutions announced in their interim financial statements that their net interest margins – a key benchmark for profitability – had already fallen in the past second quarter.

Also on Thursday, ailing real estate group Evergrande announced it would not be able to make payments on investment products this month due to liquidity problems. The company’s shares dropped to valuations in the cents range as recently as Monday. rtr / jul

In music, solo performances of instruments such as Erhu (二胡) or Pipa (琵琶) are still purely Chinese. But when it comes to orchestra, it’s another story. Traditionally, musicians in a group instrumental show play the same notes simultaneously. In the middle of last century, however, the Western concept of harmony was borrowed. Ancient ballads were re-arranged and new pieces were created using Western composing techniques. In addition, while the orchestras are composed of almost all traditional instruments, they also use Western double basses because no Chinese instrument can provide the music with a solid underlying support.

In dancing, performers of the so-called Chinese dance are trained in the Western classical way. The so-called Chinese dance works’ only differences from ballet are, number one: They tell Chinese stories; number two: female dancers don’t stand on their toes.

Classical Chinese fine artworks were rarely painted with a single perspective, if perspective was employed at all. Now, few stick to the old way. Students applying for programs of Chinese painting in schools of fine arts are also tested on Western-style sketches as well as skills using Chinese inks and brushes.

Of all the major traditional Chinese art forms still in existence today, the West had the least influence on calligraphy and Xiqu (戏曲), traditional Chinese opera.

Xiqu stands out remarkably to stay almost totally immune to Western influence. Some reforms were conducted regarding dramaturgy, the orchestra’s composition, performers’ physical movements and scene design, especially for the propaganda Peking Opera “Model Works” which dominated all Chinese stages during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). But the changes were later on all abandoned, except for some remnants in scene design. The stylized movements, the dance, the speech, and most importantly, the singing, are pretty much the same as in the old days.

Xiqu does not just mean Peking Opera. Almost all the 34 provinces have at least one local form of opera, some provinces have more than one, and some local Xiqu forms, like the Peking Opera, also have cross-provincial, even national influence, such as Yueju (越剧), which originated from Zhejiang, and Yuju (豫剧), from Henan. An estimated total of 150 forms of Xiqu are performed regularly in different parts of China.

Critics first claimed in the 1920s and 1930s that the “outdated” art form would go naturally into historical dustbins as China modernized itself.

The Republic of China was just founded on the ruins of the decrepit Qing dynasty. Intellectuals and revolutionists’ reflections on the aggression and humiliation the Chinese experienced since the Opium War (1840-1842) led to some radical ideas on how to make China stronger, which included the introduction of communism and revamping the Chinese culture. Critical voices against Xiqu included such big names as the great writer Lu Xun (鲁迅1881 – 1936), a famously scathing critic of traditional Chinese culture.

The next round of pessimism over Xiqu came in the 1980s. Emerging from the insane Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), when a nation of 800 million saw only 15 “revolutionary Peking operas” and about 20 films, the country was again on the path of modernization. In parallel to political thawing and economic reforms, hundreds of new and formerly banned films – both Chinese and foreign – television, pop music and other forms of the performing arts swept over a revitalized nation.

After being banned for over ten years, traditional Chinese operas were allowed to be performed again. But after an initial euphoria, their audience declined rapidly and sharply. It was assumed that only older people liked them and that Xiqu would die with these people. But the Chinese operas survived. They did not gain a large audience, but at least they gained a younger audience who came to appreciate the beauty of this purely Chinese gem. Today, more than 10,000 private troupes of different Xiqu forms are actively giving performances in the country, as compared to more than 100 groups for speaking drama.

Government support also plays a role. As the Chinese government gets richer, it also becomes keener to promote things representing the Chinese identity. The public funding goes mainly to the official Xiqu groups and Xiqu schools. Interestingly, but sadly, the image of Xiqu performers is less glamorous than that of artists of Western music. Children attending these opera schools are almost all from less wealthy families.

Still, the value of Chinese opera is recognized internationally. Kunqu (昆曲), the ancient, elegant opera form and prototype of all other Xiqu forms, including the Peking Opera, was put by UNESCO on the list of the Masterpieces of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, in 2001, and the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, in 2008.

In the Peony Pavilion, the most well-known Kunqu piece, the heroine Du Liniang croons at the scene in the spring garden: “A riot of deep purple and bright red, what pity on the ruins they overspread!” The days when traditional Chinese opera singers could cause a scene of riot are long gone, but the unique color and sound it contributes to humanity still shine on.

All sections of the new Guiyang-Nanning high-speed rail line have been in operation since Thursday. In numbers: 482 km of track, 148 switches, a top speed of 350 kilometers per hour. A small section of it is seen here from the air – near Duyun, the capital of Qiannan County in southwest China.