The number 13 is not to blame should Apple not be able to ship its new iPhone 13 model to customers on time next month. The reason lies in the labor shortage at Foxconn’s factories in China. The Taiwan-based company is Apple’s largest contract manufacturer. Migrant workers at Foxconn assemble 80 percent of Apple’s iPhones. But because the major industrial centers are less and less attractive to workers, they are now being lured with higher salaries and extra payments. Beijing also wants to better handle migration to the country in the future, as Frank Sieren analyses.

“Fight inequality!” – this could also be the slogan on German election posters. But it actually is the new program of China’s President Xi Jinping. His idea of the Chinese Dream lies in a more equal distribution of wealth. Finn Mayer-Kuckuk has looked into the details and sees a departure from Deng Xiaoping’s precept that “some should be allowed to get rich faster” in order to pull all others with them. The new goal is “shared prosperity for all,” and as equally distributed as possible.

Yan Mingfu, Mao’s former Russian interpreter and later vice-minister of civil affairs, has shed tears thinking back to his time in Qincheng Prison near Beijing. Johnny Erling spoke with him. He also conducted in-depth investigations to shed light on some myths surrounding the infamous prison, where Mao’s widow also served time. The prison is such a taboo that even China’s judiciary has no access to it.

Have a pleasant weekend!

China is still communist according to its title. Therefore, one question is particularly pressing there, and it is currently a concern for many other countries – including Germany and the US. The rich are getting richer much faster than the poor are gaining income. President Xi Jinping has now given China a direction to counteract this: China needs a more equal distribution of income growth, is his policy guideline, which state media proclaimed on Wednesday evening. Plans for more redistribution from the bottom to the top also resonate within his words.

In Party language, it read, “We should spare no effort to establish a ‘scientific’ public policy system that allows for fairer income distribution. In addition, Xi added, “the needs and opportunities of all must be coordinated according to financial sustainability.” Living standards should be strengthened “inclusively and from the bottom up.” A framework for development in which all can participate is needed. “Shared prosperity is the prosperity of all, […] not the wealth of a few,” Xi said. Common prosperity 共同富裕, in turn, is a precept of socialism.

Xi’s remarks on the occasion of the 10th meeting of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission mark a policy change. For he is addressing a sentiment of the great reformer Deng Xiaoping and for the first time explicitly invalidating it. The People’s Daily report on the meeting stresses that those present agreed on the historic course: The party had “broken the chains of the traditional system and allowed some people and some regions to get rich faster.” Those were Deng’s words. Some were supposed to “get rich faster” and pull along everyone else. But things are different now under Xi, the commission stresses. The Central Commission now “focuses on the steady realization of common prosperity.” By focusing on the prosperity and happiness of all Chinese people, the party is securing the foundation of its rule, the People’s Daily candidly reports on the meeting.

Regardless of the party’s phrases, a change in course was long overdue. The problem is not that the lower income brackets are not making gains. In fact, with an average annual increase of 4.5 percent, the poorer half of the population has seen very decent income gains in recent decades. But for the top 0.1 percent, the increase was more than twice as high, with 9.4 percent. Both income curves are steeply climbing, but the super-rich are exponentially outpacing ordinary people. Their wealth now reaches astronomic heights.

Around two million families in China own more than ten million yuan (the equivalent of more than 1.3 million euros). Last year, they spent more than three trillion yuan (just under 400 billion euros). China now has more dollar billionaires than the US, depending on how you look at it – and that’s saying something, after all, the latter is considered the breeding ground of capitalism, with inequality running in its DNA. Even there, the chasm between rich and poor is considered a scandal that President Joe Biden aims to fix. And under socialism, such levels of inequality should be even less acceptable.

But in his speech, Xi raises another point that is very important to his compatriots. He continues to hold out the prospect of them being able to work their way up and become rich themselves. In this regard, the Chinese Dream resembles the American Dream. As an element of personal freedom, the opportunity for advancement through diligence is likely to continue to be an extremely important underlying psychological trait in China. From the perspective of economic planners, it also provides motivation to work hard. The only problem is that rising inequality (as reported by China.Table) has recently tended to reduce opportunities rather than create them. This is because capital accumulates where capital is already present. “We should reopen the channel for upward social mobility,” Xi stresses.

The global phenomenon of inequality is now firmly studied. In 2014, the French economist Thomas Piketty brought it back into the discussion by shifting the focus from income to capital. Unlike in the post-war decades in Germany or the decades after Deng’s reforms in China, citizens with honest employment did not have many chances of economic ascent. This is because capital tends to multiply itself at a breathtaking rate without much intervention. The reason, according to Piketty, is a lack of taxation on wealth. The central banks have been fuelling the trend since 2008. The rapid expansion of money floods markets with capital. This drives up valuations of stocks, other company shares and real estate holdings. But such assets are usually only owned by the already wealthy.

This is the reason why in Germany, too, economists and sociologists are intensively investigating this phenomenon. After all, it questions the basic assumptions of a social market economy and meritocracy. However, China, as a nominal socialist society, has to work a lot harder to at least restore a feeling of equality. The common people are well aware of how the millionaires and billionaires are settling into their ivory towers and ensuring the unfettered transfer of their wealth to their children – who just got lucky to have been born into privilege. Karl Marx would spin in his grave at the sight of this kind of socialism.

A good part of China’s current policy dates back to the attempt of handling these contradictions. The crackdown on tech companies is not just aimed at their institutional power as collectors of data, but also at the iron grip on the wealth of their founders, all of whom are now billionaires. An “important speech” by Xi like the one against inequality generally marks the beginning of a long campaign. “Shared prosperity” will become a continually repeated phrase in the months and years to come. And before the end, many billionaires will find themselves in prison – if the leadership intends to make an example of the rich.

.

September will see the release of the iPhone 13. And Apple wants to ship around 130 to 150 million devices by the end of the year. And the US company still produces the majority of them in China, with most of them being assembled at Foxconn in the central Chinese city of Zhengzhou. There, the mega-factory of the Taiwanese contract manufacturer, which employs around 250,000 people, is responsible for the production of around 80 percent of all iPhones worldwide. The problem: fewer and fewer workers are willing to work at the assembly line.

According to China’s latest census, the proportion of the population between the ages of 15 and 59 in the working-age group has dropped from more than 70 percent a decade ago to 63.4 percent this year. On the one hand, this is leading to a steady rise in wages. For another, workers can afford to be pickier. They no longer have to take every job.

To counter this increasing labor shortage, Apple and Foxconn recently introduced a new bonus system. Through it, new employees who remain in the iPhone assembly – the so-called Innovative Product Enclosure Business Group (iPEBG) – for at least 90 days, will receive an additional payment of the equivalent of 1,251 euros. An additional 92 euros will be paid to those who successfully recruit an employee for the company. Foxconn has already made use of this method and others like it in the past.

Foxconn is not the only Apple supplier in China to try and attract new workers this way. Lens Technology, which supplies Apple with touch screens, and Luxshare Precision, which specializes in electronic connectors, have created similar incentives. Lens Technology, for example, increased its signing bonus from 656 euros in February to 1,311 euros in May, nearly doubling the amount. Luxshare Precision, for its part, doubled its internal referral bonus at its Dongguan plant in southern China’s Guangdong Province from 328 euros in April to 656 euros at the end of May. The company also announced a return bonus of 489 euros for former employees who have already left the company.

Despite the US trade dispute, Apple has added more Chinese suppliers to its supply chains over the last three years than from any other country. The confidence may also be due to the fact that China has overcome the Covid pandemic relatively unscathed. In contrast, production at Foxconn’s iPhone factory in India plummeted by more than 50 percent due to rising COVID-19 infections.

But not only Foxconn is suffering from a labor shortage. Several provinces and cities have also raised minimum wages significantly this year. In China’s capital Beijing, the monthly minimum wage is now 2,320 yuan, around 305 euros. The last rounds of adjustments took place in 2017 and 2018.

In 2010, when Foxconn began operations of its factory in Zhengzhou, the per capita income of employees, most of whom are migrant workers from the countryside, was still the equivalent of about 1,200 euros. Today, according to official statistics, it ranges at over 3,200 euros. Their income has thus almost tripled within ten years. In the same period, the minimum wage in the city has risen from 105 euros per month ten years ago to 250 euros per month last year.

With an increase in the minimum wage, Beijing’s leadership is also controlling migration. Years ago, minimum wages were raised by 15 percent a year in some cases. This forced factories in labor-intensive industries to move their production to the backcountry, where most of the workers hail from. In the particularly developed province of Guangdong, this has led to the creation of open space for the economically much more interesting high-tech industry, which, however, requires fewer workers. By now, this is called “reverse migration”.

Two phenomena come together in this development: In one, companies are relocating their production facilities to poorer provinces, which are mainly located in western China. In the second, the remaining migrant workers are forced to go back because they were unable to afford the cost of living in many booming regions, despite the increased wages. At the end of March this year, China’s Bureau of Statistics recorded 2.64 million fewer migrant workers than the previous year. Another reason: migrant workers are getting older. Around a quarter are now over 50 years old. Ten years ago, there were only half as many. At this age, issues such as health insurance become more important. This is more affordable in their home villages, where they are registered. “Reverse migration will increase in the coming years,” suspects Dan Wang, chief economist at Hang Seng Bank in Shanghai.

Many returnees have long since stopped working in the factories being relocated there. Many go into the service sector. They work in shops, become small traders on online platforms or drivers for the delivery platforms in the countryside.

The central government in Beijing is quite happy with this development. To ensure that the returnees are not disappointed but remain in their regions, Beijing is strengthening their rights, and working conditions in the new industrial centers are being improved. Most recently, Chinese authorities have pushed for fair wages, increased insurance coverage and reduction of deadlines for delivery service workers. Tech giants such as Meituan and Alibaba’s Ele.me were impacted by this. State regulators had recently cited them to a meeting.

Another reason is the digitalization of the economy, which makes decentralization more possible. On employment platforms such as Alibaba’s Qingtuanshe, far more open positions in third- and fourth-tier cities in rural parts of China are available than ever before, including occupations as livestream salespersons offering products via videos, for example. Fifty million rural residents alone have received access to the internet in the past year.

The digital economy now accounts for a third of China’s economic power. “More influencers are needed in the mid-price segment,” says Jialu Shan, a researcher at the International Institute for Management Development in Lausanne, Switzerland. However, it remains to be seen how many people the online industry can absorb, especially since this business requires different skills than working on an assembly line. Latest figures prove that the transition is not an easy one. Yang Xin, an analyst at the Chinese investment bank CICC, recently noted in a report that unemployment among unskilled workers has increased significantly.

The Hamburger Hafen und Logistik AG (HHLA) is negotiating with the Chinese state shipping company Cosco about a stake in the Hamburg container terminal Tollerort. “Negotiations are at an advanced stage,” says HHLA’s Chief Executive Officer Angela Titzrath. “I expect that we will soon reach an agreement,” she told the Club of Hamburg Business Journalists. Chinese shipping company Cosco is owned by the Chinese state and operates port terminals as well as shipping lines, and has been trying to invest in a Port of Hamburg terminal for some time. According to German newspaper Die Welt, Cosco wants to acquire 35 percent of the Tollerort terminal.

As ports in Germany are considered critical infrastructure, stakes by foreign investors may only be approved under certain conditions. Currently, an investment review is already said to be underway in accordance with the Foreign Trade and Payments Act. Chinese imports and exports already account for around 30 percent of container traffic in Hamburg.

Hamburg’s First Mayor Peter Tschentscher (SPD) supports Cosco’s planned investment: “There are no political guidelines for this, but what makes sense from a business perspective must also be possible in practice and has to be done,” Tschentscher said in July. The City of Hamburg owns more than two-thirds of HHLA’s shares.

The trade union Verdi is critical of this deal. “Potential problems do not primarily stem from the nationality of the investor. Rather, such a step strengthens the influence of shipowners over local logistics conditions,” Verdi announced in July. According to the statement, this would lead to“competitive conditions in shipping and handling being increasingly determined by a small, globally active group of shipowners” – with consequences for working conditions on ships and in ports. “The jobs at and throughout the port of Hamburg are our priority,” said Natale Fontana, the union’s head of the department of transport. niw

The U.S. Department of Transportation is limiting the number of passengers airlines are allowed to fly into the U.S. from China. The rules will be in place for four weeks. The capacity of flights will be curtailed to 40 percent. This latest move only is less linked to infection control than to the ongoing dispute between the two nations. China, for its part, had curtailed flights from America to its own soil in early August. The reason was passengers on a U.S. flight who tested positive for COVID-19 upon arrival. The reaction is part of the “safeguards” China has put in place to prevent any outside introduction of the virus.

However, Washington considered the unilateral restriction on passenger capacity as a distortion of competition. After all, Chinese airlines were able to continue to fill their seats without limit. US carriers such as United Airlines welcomed the backlash. The US argues that the positive tests were not independently verified. fin

Detained Hong Kong democracy activist Andy Li has pleaded guilty to violating the National Security Act, incriminating movement figurehead Jimmy Lai in the process. The 30-year-old, who used crowdfunding platforms to organize donations from overseas for the 2019 protest movement, and a 29-year-old co-defendant confessed in a court on Thursday to “colluding with foreign forces”, one of four offenses under the security law. In exchange for the confession, prosecutors dropped two other charges.

The case takes on special significance because Li accused publisher Jimmy Lai of incitement during his testimony. Lai was the most influential supporter of the democracy movement. He, too, has been in custody for months awaiting the start of his trial. Through his now-defunct newspaper Apple Daily, Lai spent 26 years countered Beijing’s creeping influence and fought for the preservation of civil rights in the city. Andy Li’s testimony heavily incriminates the 76-year-old. In a later trial against Lai, Li could serve as a prosecution witness. However, a corresponding declaration of intent by the procuratorate has not yet been made.

In talks with news agency Reuters, Andy Li’s sister complained about the lack of transparency of the trial against her brother. Neither had the family been informed of the defendant’s whereabouts since last March, nor had they been told whether and how Andy Li had chosen his lawyer. The case has “a significant resemblance to how a case is handled in the Chinese legal system,” Li’s sister said. The handling, she said, was unusual for the Hong Kong courts “as we know it.” In fact, the judges responsible had been arranged at the request of Hong Kong’s political leadership. However, the city government denies any involvement.

Li’s case was particularly remarkable because, together with eleven other activists, he had attempted to flee from Hong Kong to Taiwan in a speedboat in August 2020. The plan failed. Instead, the Chinese coast guard intercepted the fugitives. A Chinese court handed down prison sentences ranging from seven months to three years. Eight members of the group, including Li, had been extradited to Hong Kong authorities in March this year after seven months. Li was subsequently placed in a psychiatric ward without his family’s knowledge. Thursday’s appearance in court marked his first public presence, although the hearing was held on camera. The court adjourned the trial against Li and his co-defendant until Jan. 3. Despite the confession, the two men face several years in prison. grz

Beijing wants to speed up Tibet’s cultural assimilation into China. On the 70th anniversary of China’s invasion of Tibet, Wang Yang, a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Communist Party of China, said efforts were needed at every level to ensure that all Tibetans could speak and write standard Chinese and share cultural symbols and images with the Chinese nation.

State media report that Wang spoke to a select audience at the Potala Palace in Lhasa, the former seat of the Dalai Lama, who remains in exile. In the version of Chinese leadership, the inhabitants of Tibet were peacefully liberated from the oppression of theocracy. However, the international community accuses the Chinese leadership of suppressing Buddhist culture. niw

In northern Beijing, about 35 kilometers from the city, hides Qincheng, the country’s notorious special prison. All party leaders from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping have had their political opponents disappear there since 1960. No journalist was allowed to glimpse behind its walls. China’s judiciary is also kept out. Qincheng answers only to the Ministry of State Security. It’s a reminder that in China, too, the revolution eats its children.

In the past, the people of Beijing told a political joke about the secretive detention center for prominent figures: “Why are you here?” one inmate asks another in the courtyard, “Because I was against Jiang Qing (Mao Zedong’s wife). And you?” “Because I supported her.” A woman standing next to them adds, “And I’m here because I’m Jiang Qing.”

There is only one detail wrong with the joke: all prisoners in Qincheng are kept in solitary confinement. They can’t even meet in the yard. US-American Sidney Rittenberg experienced it first hand. As the only foreigner, he was imprisoned by the Cultural Revolutionaries in Qincheng for nine years. He was not released until November 1977. That summer, he overheard a woman in a cell chanting praises to Chairman Mao. He recognized the voice. It was Jiang Qing.

Mao’s widow had been arrested during a Beijing palace coup after the death of her husband in October 1976. While Mao remained untouchable as a figurehead until today, all his crimes were blamed on his wife. In April1977, she was imprisoned in Qincheng and sentenced to death in a show trial in 1981. The sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment in Qincheng. Jiang Qing took her own life on May 14, 1991.

Rittenberg knew her well. Mao and his wife had used the radical leftist foreign cultural revolutionary as their activist, letting him rise in ranks. His subsequent fall was all the harder. In his biography, “The Man who stayed behind” (Simon & Schuster), he describes how Mao’s henchmen arrested him at midnight. The arrest warrant was “signed by all 16 members of the Proletarian Headquarters, including Mao, Zhou Enlai and Jiang Qing.”

As prisoner number 32 admitted to Qincheng in 1968, Rittenberg became prisoner 6832. Mao’s former Russian interpreter Yan Mingfu had already been placed behind bars for half a year under number 67124 as the 124th prisoner admitted in 1967. Accused of being a spy for Moscow, Yan remained in prison until 1975. Two decades later, I interviewed him in Beijing. Back then, he was a minister. He told me that just a few meters from his cell, his father Yan Baohuang was also imprisoned as prisoner 67100. Yan didn’t know this. Once at night, he heard someone coughing, just like his father always had. Only after his release did Yan learn that it was indeed his father, who died soon after. His ashes were tossed away. The minister cried when he told me about the cruelties in Qincheng.

Father and son were inhumanely treated by Mao and Jiang Qing, whom they had served faithfully for decades, as were countless others. At the height of the Cultural Revolutionary chaos, half of the 502 prisoners were companions of Mao, as his former secretary Li Rui recalled. Because of critical words, he made an early enemy of the dictator, who sensed enemies at every corner, and was eventually placed in solitary confinement in Qincheng for eight years. “Nearly 30 died, 20 were crippled, over 60 went insane,” he revealed in the May 2015 issue of Yanhuang Chunjiu magazine. Li Rui survived and remained sane because he secretly wrote 400 poems with a tincture made of iodine. As early as 1955, Mao had demanded for him to build a special prison for his perceived opponents

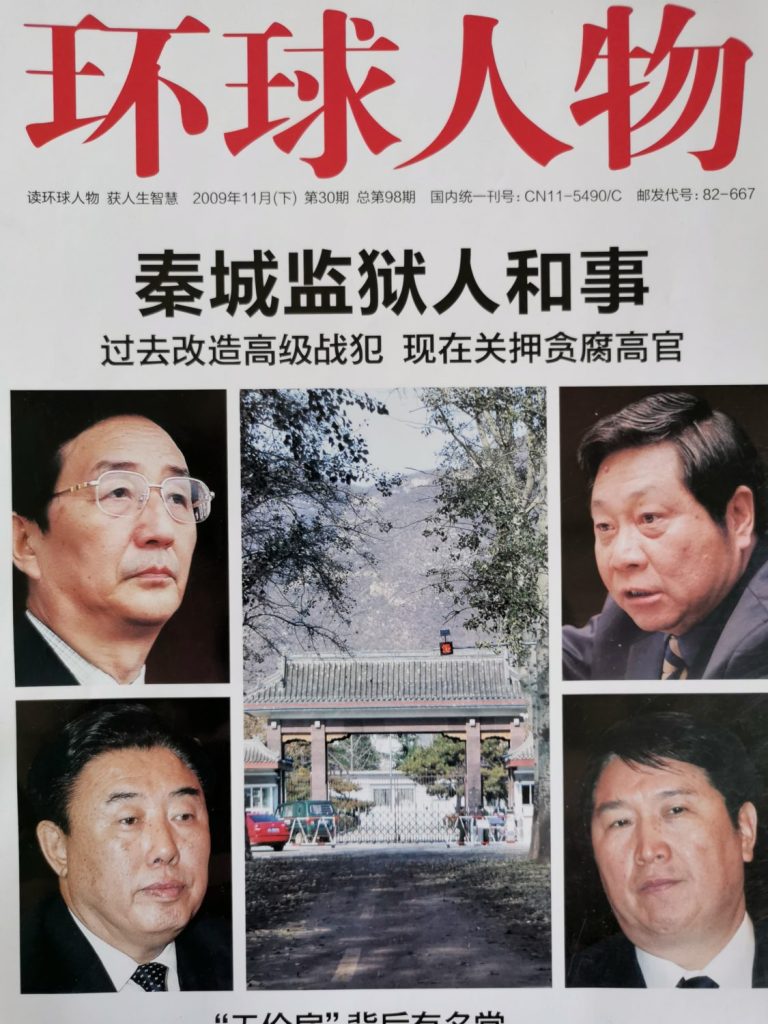

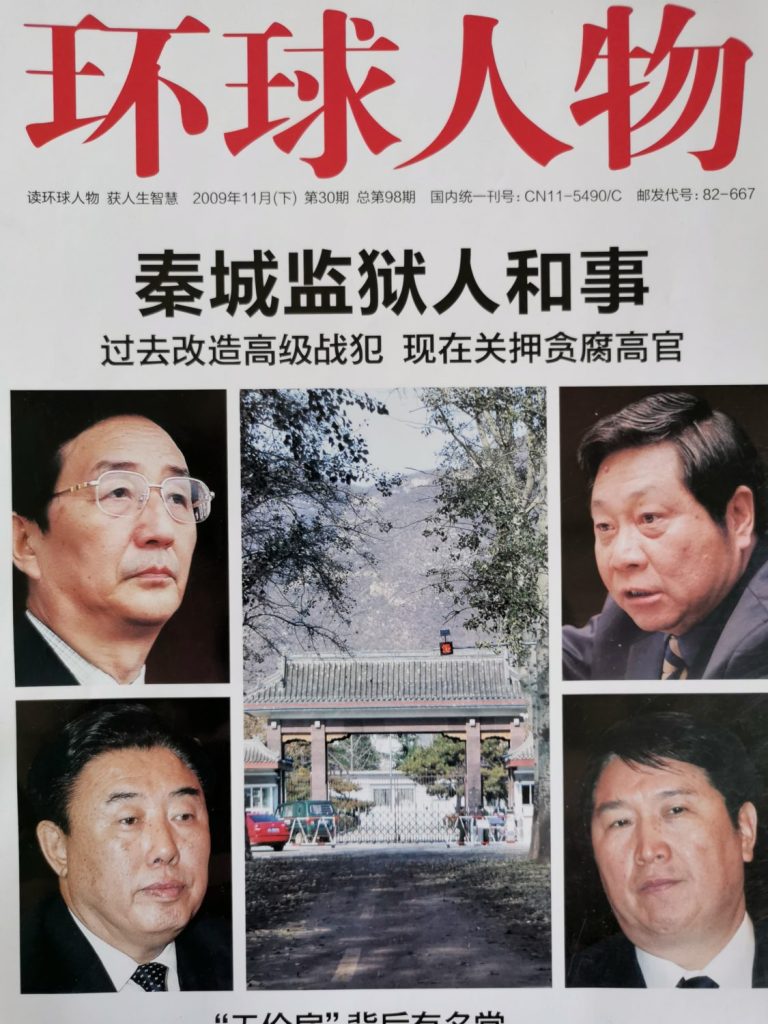

As a grotesque footnote to Cultural Revolutionary history, Li Rui notes that Feng Qiqing, the former vice-mayor of Beijing who supervised the construction of the prison for Mao, was arrested in 1968 as a “bourgeois reactionary” and also imprisoned in Qincheng until 1975. With the help of Soviet experts, modeled after Stalin’s Sukhanovka Prison, four three-story, alphabetically separated detention buildings were built, each with its own interrogation rooms and a surrounding five-meter high wall. In 1960, the new prison was put into service. In 2009, the Global People Magazine, published by the People’s Daily, first printed a 12-page exposé on Qincheng as its cover story. In fact, the prison should have been number 157 among the 156 aid projects for China in cooperation with Moscow. Because of the secrecy, this did not happen.

Global People has featured inmates incarcerated since 1960. It began with hundreds of high-ranking Kuomintang military officers, war criminals and spies in the 1960s. Then came the losers of power struggles within the party. First, the most prominent victims of Mao’s campaigns such as the 1957 anti-rights movement and his Cultural Revolution ended up in Qincheng. Then, after Mao’s death, the alleged conspirators of the “Lin Biao clique” and the “Gang of Four around Mao’s widow.” In the 1990s, prominent dissidents such as Wei Jingsheng to student leader of June 4th, Wang Dan were also imprisoned, as were Party leaders and Politburo members from Shanghai and Beijing. At the time of the Cultural Revolution, the prison already had to be expanded by six new buildings.

The first comprehensive report on Qincheng was authored by journalist Yuan Ling, who interviewed some 100 former inmates and spent more than ten years researching for his Chinese book on the prison (袁凌:秦城监狱). Yuan Ling calls Qincheng the result of a “joint birth of the Soviet system with China’s authoritative system of people’s democratic dictatorship.” (它是苏维埃体制与人民民主专政权威的共同产儿.) He found no publisher in mainland China; in Hong Kong, only a small printing house dared to publish it in 2016.

This is because since Xi Jinping took office in late 2012, Qincheng has found a new use. It is widely known as the “cage for tigers” because dozens of once-famous party politicians, provincial governors, People’s Congress leaders, military brass, or CEOs of big corporations and banks from all over the country have a rendezvous behind bars. Xi had them all arrested overnight, ousted, and later formally convicted of horrendous corruption. Afterward, they all ended up in Qincheng. Many illustrious names are found among the inmates, such as Chongqing’s party leader Bo Xilai, ex-security czar Zhou Yongkang, high-ranking generals like Guo Boxiong, or CCP chief advisors like Ling Jihua.

Current reports about the prison are confidential. All that is known is that the fallen ex-elite are now housed in more comfortable, larger single cells and are better cared for than in the past. But Qincheng, to which China’s judiciary has no access, remains a place where revolution eats its own children. Once again, it is as secretive and shrouded as it had been in the past.

Hui Ka Yan, the founder of troubled real estate group Evergrande, is stepping down as chairman of Hengda Real Estate. Hui is thus drawing the consequences of a series of failed ventures on the financial market. Hengda is the most important part of the Evergrande company network in the People’s Republic. He is succeeded by Zhao Changlong. Until 2017, Zhao already held the position of chairman. He simultaneously steps up as CEO and will exert extensive control over Hengda during the crisis.

Chinese athletes arriving in Tokyo, where the Paralympics will be held starting Tuesday. On Thursday, the host city of Tokyo reported 5534 new infections, the second-highest level since the outbreak of the pandemic.

The number 13 is not to blame should Apple not be able to ship its new iPhone 13 model to customers on time next month. The reason lies in the labor shortage at Foxconn’s factories in China. The Taiwan-based company is Apple’s largest contract manufacturer. Migrant workers at Foxconn assemble 80 percent of Apple’s iPhones. But because the major industrial centers are less and less attractive to workers, they are now being lured with higher salaries and extra payments. Beijing also wants to better handle migration to the country in the future, as Frank Sieren analyses.

“Fight inequality!” – this could also be the slogan on German election posters. But it actually is the new program of China’s President Xi Jinping. His idea of the Chinese Dream lies in a more equal distribution of wealth. Finn Mayer-Kuckuk has looked into the details and sees a departure from Deng Xiaoping’s precept that “some should be allowed to get rich faster” in order to pull all others with them. The new goal is “shared prosperity for all,” and as equally distributed as possible.

Yan Mingfu, Mao’s former Russian interpreter and later vice-minister of civil affairs, has shed tears thinking back to his time in Qincheng Prison near Beijing. Johnny Erling spoke with him. He also conducted in-depth investigations to shed light on some myths surrounding the infamous prison, where Mao’s widow also served time. The prison is such a taboo that even China’s judiciary has no access to it.

Have a pleasant weekend!

China is still communist according to its title. Therefore, one question is particularly pressing there, and it is currently a concern for many other countries – including Germany and the US. The rich are getting richer much faster than the poor are gaining income. President Xi Jinping has now given China a direction to counteract this: China needs a more equal distribution of income growth, is his policy guideline, which state media proclaimed on Wednesday evening. Plans for more redistribution from the bottom to the top also resonate within his words.

In Party language, it read, “We should spare no effort to establish a ‘scientific’ public policy system that allows for fairer income distribution. In addition, Xi added, “the needs and opportunities of all must be coordinated according to financial sustainability.” Living standards should be strengthened “inclusively and from the bottom up.” A framework for development in which all can participate is needed. “Shared prosperity is the prosperity of all, […] not the wealth of a few,” Xi said. Common prosperity 共同富裕, in turn, is a precept of socialism.

Xi’s remarks on the occasion of the 10th meeting of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission mark a policy change. For he is addressing a sentiment of the great reformer Deng Xiaoping and for the first time explicitly invalidating it. The People’s Daily report on the meeting stresses that those present agreed on the historic course: The party had “broken the chains of the traditional system and allowed some people and some regions to get rich faster.” Those were Deng’s words. Some were supposed to “get rich faster” and pull along everyone else. But things are different now under Xi, the commission stresses. The Central Commission now “focuses on the steady realization of common prosperity.” By focusing on the prosperity and happiness of all Chinese people, the party is securing the foundation of its rule, the People’s Daily candidly reports on the meeting.

Regardless of the party’s phrases, a change in course was long overdue. The problem is not that the lower income brackets are not making gains. In fact, with an average annual increase of 4.5 percent, the poorer half of the population has seen very decent income gains in recent decades. But for the top 0.1 percent, the increase was more than twice as high, with 9.4 percent. Both income curves are steeply climbing, but the super-rich are exponentially outpacing ordinary people. Their wealth now reaches astronomic heights.

Around two million families in China own more than ten million yuan (the equivalent of more than 1.3 million euros). Last year, they spent more than three trillion yuan (just under 400 billion euros). China now has more dollar billionaires than the US, depending on how you look at it – and that’s saying something, after all, the latter is considered the breeding ground of capitalism, with inequality running in its DNA. Even there, the chasm between rich and poor is considered a scandal that President Joe Biden aims to fix. And under socialism, such levels of inequality should be even less acceptable.

But in his speech, Xi raises another point that is very important to his compatriots. He continues to hold out the prospect of them being able to work their way up and become rich themselves. In this regard, the Chinese Dream resembles the American Dream. As an element of personal freedom, the opportunity for advancement through diligence is likely to continue to be an extremely important underlying psychological trait in China. From the perspective of economic planners, it also provides motivation to work hard. The only problem is that rising inequality (as reported by China.Table) has recently tended to reduce opportunities rather than create them. This is because capital accumulates where capital is already present. “We should reopen the channel for upward social mobility,” Xi stresses.

The global phenomenon of inequality is now firmly studied. In 2014, the French economist Thomas Piketty brought it back into the discussion by shifting the focus from income to capital. Unlike in the post-war decades in Germany or the decades after Deng’s reforms in China, citizens with honest employment did not have many chances of economic ascent. This is because capital tends to multiply itself at a breathtaking rate without much intervention. The reason, according to Piketty, is a lack of taxation on wealth. The central banks have been fuelling the trend since 2008. The rapid expansion of money floods markets with capital. This drives up valuations of stocks, other company shares and real estate holdings. But such assets are usually only owned by the already wealthy.

This is the reason why in Germany, too, economists and sociologists are intensively investigating this phenomenon. After all, it questions the basic assumptions of a social market economy and meritocracy. However, China, as a nominal socialist society, has to work a lot harder to at least restore a feeling of equality. The common people are well aware of how the millionaires and billionaires are settling into their ivory towers and ensuring the unfettered transfer of their wealth to their children – who just got lucky to have been born into privilege. Karl Marx would spin in his grave at the sight of this kind of socialism.

A good part of China’s current policy dates back to the attempt of handling these contradictions. The crackdown on tech companies is not just aimed at their institutional power as collectors of data, but also at the iron grip on the wealth of their founders, all of whom are now billionaires. An “important speech” by Xi like the one against inequality generally marks the beginning of a long campaign. “Shared prosperity” will become a continually repeated phrase in the months and years to come. And before the end, many billionaires will find themselves in prison – if the leadership intends to make an example of the rich.

.

September will see the release of the iPhone 13. And Apple wants to ship around 130 to 150 million devices by the end of the year. And the US company still produces the majority of them in China, with most of them being assembled at Foxconn in the central Chinese city of Zhengzhou. There, the mega-factory of the Taiwanese contract manufacturer, which employs around 250,000 people, is responsible for the production of around 80 percent of all iPhones worldwide. The problem: fewer and fewer workers are willing to work at the assembly line.

According to China’s latest census, the proportion of the population between the ages of 15 and 59 in the working-age group has dropped from more than 70 percent a decade ago to 63.4 percent this year. On the one hand, this is leading to a steady rise in wages. For another, workers can afford to be pickier. They no longer have to take every job.

To counter this increasing labor shortage, Apple and Foxconn recently introduced a new bonus system. Through it, new employees who remain in the iPhone assembly – the so-called Innovative Product Enclosure Business Group (iPEBG) – for at least 90 days, will receive an additional payment of the equivalent of 1,251 euros. An additional 92 euros will be paid to those who successfully recruit an employee for the company. Foxconn has already made use of this method and others like it in the past.

Foxconn is not the only Apple supplier in China to try and attract new workers this way. Lens Technology, which supplies Apple with touch screens, and Luxshare Precision, which specializes in electronic connectors, have created similar incentives. Lens Technology, for example, increased its signing bonus from 656 euros in February to 1,311 euros in May, nearly doubling the amount. Luxshare Precision, for its part, doubled its internal referral bonus at its Dongguan plant in southern China’s Guangdong Province from 328 euros in April to 656 euros at the end of May. The company also announced a return bonus of 489 euros for former employees who have already left the company.

Despite the US trade dispute, Apple has added more Chinese suppliers to its supply chains over the last three years than from any other country. The confidence may also be due to the fact that China has overcome the Covid pandemic relatively unscathed. In contrast, production at Foxconn’s iPhone factory in India plummeted by more than 50 percent due to rising COVID-19 infections.

But not only Foxconn is suffering from a labor shortage. Several provinces and cities have also raised minimum wages significantly this year. In China’s capital Beijing, the monthly minimum wage is now 2,320 yuan, around 305 euros. The last rounds of adjustments took place in 2017 and 2018.

In 2010, when Foxconn began operations of its factory in Zhengzhou, the per capita income of employees, most of whom are migrant workers from the countryside, was still the equivalent of about 1,200 euros. Today, according to official statistics, it ranges at over 3,200 euros. Their income has thus almost tripled within ten years. In the same period, the minimum wage in the city has risen from 105 euros per month ten years ago to 250 euros per month last year.

With an increase in the minimum wage, Beijing’s leadership is also controlling migration. Years ago, minimum wages were raised by 15 percent a year in some cases. This forced factories in labor-intensive industries to move their production to the backcountry, where most of the workers hail from. In the particularly developed province of Guangdong, this has led to the creation of open space for the economically much more interesting high-tech industry, which, however, requires fewer workers. By now, this is called “reverse migration”.

Two phenomena come together in this development: In one, companies are relocating their production facilities to poorer provinces, which are mainly located in western China. In the second, the remaining migrant workers are forced to go back because they were unable to afford the cost of living in many booming regions, despite the increased wages. At the end of March this year, China’s Bureau of Statistics recorded 2.64 million fewer migrant workers than the previous year. Another reason: migrant workers are getting older. Around a quarter are now over 50 years old. Ten years ago, there were only half as many. At this age, issues such as health insurance become more important. This is more affordable in their home villages, where they are registered. “Reverse migration will increase in the coming years,” suspects Dan Wang, chief economist at Hang Seng Bank in Shanghai.

Many returnees have long since stopped working in the factories being relocated there. Many go into the service sector. They work in shops, become small traders on online platforms or drivers for the delivery platforms in the countryside.

The central government in Beijing is quite happy with this development. To ensure that the returnees are not disappointed but remain in their regions, Beijing is strengthening their rights, and working conditions in the new industrial centers are being improved. Most recently, Chinese authorities have pushed for fair wages, increased insurance coverage and reduction of deadlines for delivery service workers. Tech giants such as Meituan and Alibaba’s Ele.me were impacted by this. State regulators had recently cited them to a meeting.

Another reason is the digitalization of the economy, which makes decentralization more possible. On employment platforms such as Alibaba’s Qingtuanshe, far more open positions in third- and fourth-tier cities in rural parts of China are available than ever before, including occupations as livestream salespersons offering products via videos, for example. Fifty million rural residents alone have received access to the internet in the past year.

The digital economy now accounts for a third of China’s economic power. “More influencers are needed in the mid-price segment,” says Jialu Shan, a researcher at the International Institute for Management Development in Lausanne, Switzerland. However, it remains to be seen how many people the online industry can absorb, especially since this business requires different skills than working on an assembly line. Latest figures prove that the transition is not an easy one. Yang Xin, an analyst at the Chinese investment bank CICC, recently noted in a report that unemployment among unskilled workers has increased significantly.

The Hamburger Hafen und Logistik AG (HHLA) is negotiating with the Chinese state shipping company Cosco about a stake in the Hamburg container terminal Tollerort. “Negotiations are at an advanced stage,” says HHLA’s Chief Executive Officer Angela Titzrath. “I expect that we will soon reach an agreement,” she told the Club of Hamburg Business Journalists. Chinese shipping company Cosco is owned by the Chinese state and operates port terminals as well as shipping lines, and has been trying to invest in a Port of Hamburg terminal for some time. According to German newspaper Die Welt, Cosco wants to acquire 35 percent of the Tollerort terminal.

As ports in Germany are considered critical infrastructure, stakes by foreign investors may only be approved under certain conditions. Currently, an investment review is already said to be underway in accordance with the Foreign Trade and Payments Act. Chinese imports and exports already account for around 30 percent of container traffic in Hamburg.

Hamburg’s First Mayor Peter Tschentscher (SPD) supports Cosco’s planned investment: “There are no political guidelines for this, but what makes sense from a business perspective must also be possible in practice and has to be done,” Tschentscher said in July. The City of Hamburg owns more than two-thirds of HHLA’s shares.

The trade union Verdi is critical of this deal. “Potential problems do not primarily stem from the nationality of the investor. Rather, such a step strengthens the influence of shipowners over local logistics conditions,” Verdi announced in July. According to the statement, this would lead to“competitive conditions in shipping and handling being increasingly determined by a small, globally active group of shipowners” – with consequences for working conditions on ships and in ports. “The jobs at and throughout the port of Hamburg are our priority,” said Natale Fontana, the union’s head of the department of transport. niw

The U.S. Department of Transportation is limiting the number of passengers airlines are allowed to fly into the U.S. from China. The rules will be in place for four weeks. The capacity of flights will be curtailed to 40 percent. This latest move only is less linked to infection control than to the ongoing dispute between the two nations. China, for its part, had curtailed flights from America to its own soil in early August. The reason was passengers on a U.S. flight who tested positive for COVID-19 upon arrival. The reaction is part of the “safeguards” China has put in place to prevent any outside introduction of the virus.

However, Washington considered the unilateral restriction on passenger capacity as a distortion of competition. After all, Chinese airlines were able to continue to fill their seats without limit. US carriers such as United Airlines welcomed the backlash. The US argues that the positive tests were not independently verified. fin

Detained Hong Kong democracy activist Andy Li has pleaded guilty to violating the National Security Act, incriminating movement figurehead Jimmy Lai in the process. The 30-year-old, who used crowdfunding platforms to organize donations from overseas for the 2019 protest movement, and a 29-year-old co-defendant confessed in a court on Thursday to “colluding with foreign forces”, one of four offenses under the security law. In exchange for the confession, prosecutors dropped two other charges.

The case takes on special significance because Li accused publisher Jimmy Lai of incitement during his testimony. Lai was the most influential supporter of the democracy movement. He, too, has been in custody for months awaiting the start of his trial. Through his now-defunct newspaper Apple Daily, Lai spent 26 years countered Beijing’s creeping influence and fought for the preservation of civil rights in the city. Andy Li’s testimony heavily incriminates the 76-year-old. In a later trial against Lai, Li could serve as a prosecution witness. However, a corresponding declaration of intent by the procuratorate has not yet been made.

In talks with news agency Reuters, Andy Li’s sister complained about the lack of transparency of the trial against her brother. Neither had the family been informed of the defendant’s whereabouts since last March, nor had they been told whether and how Andy Li had chosen his lawyer. The case has “a significant resemblance to how a case is handled in the Chinese legal system,” Li’s sister said. The handling, she said, was unusual for the Hong Kong courts “as we know it.” In fact, the judges responsible had been arranged at the request of Hong Kong’s political leadership. However, the city government denies any involvement.

Li’s case was particularly remarkable because, together with eleven other activists, he had attempted to flee from Hong Kong to Taiwan in a speedboat in August 2020. The plan failed. Instead, the Chinese coast guard intercepted the fugitives. A Chinese court handed down prison sentences ranging from seven months to three years. Eight members of the group, including Li, had been extradited to Hong Kong authorities in March this year after seven months. Li was subsequently placed in a psychiatric ward without his family’s knowledge. Thursday’s appearance in court marked his first public presence, although the hearing was held on camera. The court adjourned the trial against Li and his co-defendant until Jan. 3. Despite the confession, the two men face several years in prison. grz

Beijing wants to speed up Tibet’s cultural assimilation into China. On the 70th anniversary of China’s invasion of Tibet, Wang Yang, a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Communist Party of China, said efforts were needed at every level to ensure that all Tibetans could speak and write standard Chinese and share cultural symbols and images with the Chinese nation.

State media report that Wang spoke to a select audience at the Potala Palace in Lhasa, the former seat of the Dalai Lama, who remains in exile. In the version of Chinese leadership, the inhabitants of Tibet were peacefully liberated from the oppression of theocracy. However, the international community accuses the Chinese leadership of suppressing Buddhist culture. niw

In northern Beijing, about 35 kilometers from the city, hides Qincheng, the country’s notorious special prison. All party leaders from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping have had their political opponents disappear there since 1960. No journalist was allowed to glimpse behind its walls. China’s judiciary is also kept out. Qincheng answers only to the Ministry of State Security. It’s a reminder that in China, too, the revolution eats its children.

In the past, the people of Beijing told a political joke about the secretive detention center for prominent figures: “Why are you here?” one inmate asks another in the courtyard, “Because I was against Jiang Qing (Mao Zedong’s wife). And you?” “Because I supported her.” A woman standing next to them adds, “And I’m here because I’m Jiang Qing.”

There is only one detail wrong with the joke: all prisoners in Qincheng are kept in solitary confinement. They can’t even meet in the yard. US-American Sidney Rittenberg experienced it first hand. As the only foreigner, he was imprisoned by the Cultural Revolutionaries in Qincheng for nine years. He was not released until November 1977. That summer, he overheard a woman in a cell chanting praises to Chairman Mao. He recognized the voice. It was Jiang Qing.

Mao’s widow had been arrested during a Beijing palace coup after the death of her husband in October 1976. While Mao remained untouchable as a figurehead until today, all his crimes were blamed on his wife. In April1977, she was imprisoned in Qincheng and sentenced to death in a show trial in 1981. The sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment in Qincheng. Jiang Qing took her own life on May 14, 1991.

Rittenberg knew her well. Mao and his wife had used the radical leftist foreign cultural revolutionary as their activist, letting him rise in ranks. His subsequent fall was all the harder. In his biography, “The Man who stayed behind” (Simon & Schuster), he describes how Mao’s henchmen arrested him at midnight. The arrest warrant was “signed by all 16 members of the Proletarian Headquarters, including Mao, Zhou Enlai and Jiang Qing.”

As prisoner number 32 admitted to Qincheng in 1968, Rittenberg became prisoner 6832. Mao’s former Russian interpreter Yan Mingfu had already been placed behind bars for half a year under number 67124 as the 124th prisoner admitted in 1967. Accused of being a spy for Moscow, Yan remained in prison until 1975. Two decades later, I interviewed him in Beijing. Back then, he was a minister. He told me that just a few meters from his cell, his father Yan Baohuang was also imprisoned as prisoner 67100. Yan didn’t know this. Once at night, he heard someone coughing, just like his father always had. Only after his release did Yan learn that it was indeed his father, who died soon after. His ashes were tossed away. The minister cried when he told me about the cruelties in Qincheng.

Father and son were inhumanely treated by Mao and Jiang Qing, whom they had served faithfully for decades, as were countless others. At the height of the Cultural Revolutionary chaos, half of the 502 prisoners were companions of Mao, as his former secretary Li Rui recalled. Because of critical words, he made an early enemy of the dictator, who sensed enemies at every corner, and was eventually placed in solitary confinement in Qincheng for eight years. “Nearly 30 died, 20 were crippled, over 60 went insane,” he revealed in the May 2015 issue of Yanhuang Chunjiu magazine. Li Rui survived and remained sane because he secretly wrote 400 poems with a tincture made of iodine. As early as 1955, Mao had demanded for him to build a special prison for his perceived opponents

As a grotesque footnote to Cultural Revolutionary history, Li Rui notes that Feng Qiqing, the former vice-mayor of Beijing who supervised the construction of the prison for Mao, was arrested in 1968 as a “bourgeois reactionary” and also imprisoned in Qincheng until 1975. With the help of Soviet experts, modeled after Stalin’s Sukhanovka Prison, four three-story, alphabetically separated detention buildings were built, each with its own interrogation rooms and a surrounding five-meter high wall. In 1960, the new prison was put into service. In 2009, the Global People Magazine, published by the People’s Daily, first printed a 12-page exposé on Qincheng as its cover story. In fact, the prison should have been number 157 among the 156 aid projects for China in cooperation with Moscow. Because of the secrecy, this did not happen.

Global People has featured inmates incarcerated since 1960. It began with hundreds of high-ranking Kuomintang military officers, war criminals and spies in the 1960s. Then came the losers of power struggles within the party. First, the most prominent victims of Mao’s campaigns such as the 1957 anti-rights movement and his Cultural Revolution ended up in Qincheng. Then, after Mao’s death, the alleged conspirators of the “Lin Biao clique” and the “Gang of Four around Mao’s widow.” In the 1990s, prominent dissidents such as Wei Jingsheng to student leader of June 4th, Wang Dan were also imprisoned, as were Party leaders and Politburo members from Shanghai and Beijing. At the time of the Cultural Revolution, the prison already had to be expanded by six new buildings.

The first comprehensive report on Qincheng was authored by journalist Yuan Ling, who interviewed some 100 former inmates and spent more than ten years researching for his Chinese book on the prison (袁凌:秦城监狱). Yuan Ling calls Qincheng the result of a “joint birth of the Soviet system with China’s authoritative system of people’s democratic dictatorship.” (它是苏维埃体制与人民民主专政权威的共同产儿.) He found no publisher in mainland China; in Hong Kong, only a small printing house dared to publish it in 2016.

This is because since Xi Jinping took office in late 2012, Qincheng has found a new use. It is widely known as the “cage for tigers” because dozens of once-famous party politicians, provincial governors, People’s Congress leaders, military brass, or CEOs of big corporations and banks from all over the country have a rendezvous behind bars. Xi had them all arrested overnight, ousted, and later formally convicted of horrendous corruption. Afterward, they all ended up in Qincheng. Many illustrious names are found among the inmates, such as Chongqing’s party leader Bo Xilai, ex-security czar Zhou Yongkang, high-ranking generals like Guo Boxiong, or CCP chief advisors like Ling Jihua.

Current reports about the prison are confidential. All that is known is that the fallen ex-elite are now housed in more comfortable, larger single cells and are better cared for than in the past. But Qincheng, to which China’s judiciary has no access, remains a place where revolution eats its own children. Once again, it is as secretive and shrouded as it had been in the past.

Hui Ka Yan, the founder of troubled real estate group Evergrande, is stepping down as chairman of Hengda Real Estate. Hui is thus drawing the consequences of a series of failed ventures on the financial market. Hengda is the most important part of the Evergrande company network in the People’s Republic. He is succeeded by Zhao Changlong. Until 2017, Zhao already held the position of chairman. He simultaneously steps up as CEO and will exert extensive control over Hengda during the crisis.

Chinese athletes arriving in Tokyo, where the Paralympics will be held starting Tuesday. On Thursday, the host city of Tokyo reported 5534 new infections, the second-highest level since the outbreak of the pandemic.