“The Winter Games are a huge publicity event for China,” says Hans-Martin Renn. The German architect helped design a ski jump in the host city of Zhangjiakou – a daring undertaking at times, as he told Marcel Grzanna in today’s interview. Before the planning conferences could even begin, not only phones had to be turned over, but even all ownership rights to the submitted designs.

However, Renn was well-prepared for the drinking spree with his Chinese business partners. He had poured down “all the water and soup on the table between toasts”. It paid off: In the end, his company’s concept won the bid. Now the ski jump stands tall in the mountains northwest of Beijing and will be the venue for the Winter Games on February 3.

As it is well known, the snow around the ski jump came from snow cannons, which in turn run on electricity. A most unfortunate fact, given the high priority placed on climate protection and air pollution control. Most of China’s power is still generated from coal, after all. It is fired by large and sluggish state-owned companies, still favored by the government in spite of crises and bottlenecks. If China wants to achieve its climate goals, this situation has to be broken up, writes Christiane Kuehl. A good start would be to effectively stop the planned construction of a whole series of new coal-fired power plants.

Meanwhile, China.Table has learned from well-informed circles in the capital who the new German ambassador to Beijing will be. The Foreign Ministry has chosen Miguel Berger. The high-ranking diplomat lost his position as Secretary of State in the party-political castling that followed the election. From the looks of it, he will be heading to the Far East – taking up a challenging post that requires a great deal of finesse.

Mr. Renn, is the construction of a ski jump in the Chinese province one of the last great adventures of our time?

There is some truth to that. But as is the case with many adventures, they are extremely exciting at first, but after a while everything becomes normal. In the end, it’s a task that has to be accomplished. Especially since there aren’t as many emotions involved as when we built the ski jump in Oberstdorf a few years ago. Of course, I have a completely different connection in this case. And I haven’t been back to China since the start of the pandemic anyway.

What was the tricky part of building the ski jump at Zhangjiakou?

My responsibility was to determine the profile of the ski jump and how it would fit into the landscape. My office has very good expertise in 3D planning. Furthermore, the assignment included the planning of all ski jumping-related issues such as infrastructure, construction and compliance with standards. The topography at 1700 meters above sea level was a challenge because the outrun of the ski jump is located in a hollow between two hills. But what concerned me much more was the question of what should happen to the village that was located in this hollow.

There probably haven’t been many options.

I was told that it was being removed. And in fact, a year later, there was no house left. The people supposedly got an apartment somewhere else and two years’ salary on top of that. But that could not have been much. The people’s economic status suggested as much.

You were involved in the planning of the facility as commission director and architect on behalf of the FIS. Who was sitting across from your panel of experts on the Chinese side?

They were representatives of the BOCOG organizing committee and Communist Party officials, both from provincial and district levels. Also, the future operator of the facility.

What’s it like to confer about ski jumps with people who have absolutely no idea what it involves?

The overall approach was highly professional, as was the case with the awarding of the architectural planning contract, where I was part of the jury. Each participant was provided with simultaneous translation into his or her national language as well as a personal minute-taker. What was new for me, however, was that we all had to hand over our cell phones at the door.

Why?

They probably wanted to ensure that communication would only take place via the state organs. If you look at the big picture, you can perhaps understand that. The Winter Games are a huge publicity event for China. Evidently, they leave nothing to chance.

Was the event classified as ‘top secret’?

Apparently, everything that took place in the room was a kind of intellectual government property and enjoyed the highest level of priority. This included that all facility designs brought in from all over the world became Chinese property. Everyone had to fully cede their intellectual property rights. This also included all architects of the rejected designs. That’s not really common practice. But those were rules that were clearly communicated from the very beginning.

Perhaps another ski jump will be built later elsewhere in China based on these confiscated designs.

That may be, but I consider confiscated to be the wrong word. Everyone involved was informed about this in advance and knew what they were getting into.

You could say that you were almost lucky you didn’t submit a design of your own.

Such a project would have been out of our office’s league. It may be tempting to take part in such a bid. But when you see how much effort the bidders put into their presentations alone, it was actually a relief not to have taken part.

Has nothing actually ever leaked to the outside world during the whole project?

I am not aware of this. That is even though all experts openly discussed their opinions on the drafts. But why certain decisions were made in the end is beyond me.

Could you give an example?

Well, I was the only one in a panel of about 25 experts who favored a design of the entire facility with a kind of circular walk. I really liked this urban idea of enclosing the ski jump, the biathlon facility and the cross-country ski trail with a kind of Chinese wall and providing them with different entrance areas.

And?

This exact design was selected, even though other designs received greater support.

Maybe because German cities are popular in China and you as a German represented this relation.

That may be. In any case, I noticed the high respect of the Chinese for “Made in Germany”. But also their disappointment about the diesel scandal that surfaced at the time. ‘We never thought the Germans would cheat,’ I was told, often and unprompted. I don’t think that the executives who were involved in this are aware of the damage they caused, even to this day.

China is facing criticism, including for its treatment of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Were there moments when you got a queasy feeling about helping the Chinese government build one of the Olympic monuments?

Of course, I asked myself that question. But in the end, I was also just a cog in the wheel. If I hadn’t done it, it would have been someone else. I am not responsible for the framework conditions. It’s not about making a profit, it’s about ensuring that the sport can be carried out properly. The thoughts I had when I set foot on Chinese soil for the first time were of a different sort. I noticed all the cameras and the thousands of police officers. It got me thinking about what would happen if you couldn’t leave the country.

The IOC praises the sustainability of the Olympic Games. What about the sustainability of the ski jump venue?

At least there were wind turbines everywhere on the way from Beijing to Zhangjiakou. That surprised me. As far as the construction of the venue is concerned, I am not aware of any particularly sustainable elements. It is possible that the ski jumping arena will also be used for other sports. A soccer field has been built in the out-run area. I think that sustainability should not be measured by whether any ski jumping takes place in the future, but rather if the many tourist investments around the sports facilities will be accepted. The ski jump has become a real tourist attraction. From the restaurant platform, people can then marvel at what sports are now possible in their country.

Did you also have to celebrate the successful sounding of the designs with the cadres in Chinese tradition?

Oh, yes. At some point, people stopped drinking from glasses and instead drank straight from the carafes. I sat right next to the future operator, a massive guy with Mongolian roots. Fortunately, I was mentally prepared for such a binge. I poured down all the water and soup available in between toasts. The next day, I was a hero to him. Others from the delegation, on the other hand, were not so lucky.

Welcome to China.

That’s just the culture there. At the Oktoberfest, business partners also drink jugs of beer and later dance on the tables.

Architect Hans-Martin Renn, 55, from Fischen in the German Allgäu region, is Chairman of the subcommittee for ski jumping hills of the International Ski Federation’s (FIS). When the organizers of the Winter Olympics in Beijing (February 4 to 20) asked the federation for assistance in designing a suitable venue for the Nordic skiing competitions of ski jumping and cross-country skiing as well as the biathlon, Renn traveled to the People’s Republic of China for the first time in 2017. With his architectural office, he also supported the construction of the venue in Zhangjiakou, China.

Smokestacks and solar farms, coal-fired power and wind power: In China’s power sector, too, the past and the future are wrestling with each other. The world is worried about a huge pipeline of planned coal-fired power plants in the country. And at the same time, China is building wind and solar power plants like no other country. In 2021, wind and solar farms accounted for more than half of the new power capacity connected to the grid – for the fifth year in a row. Photovoltaics, in particular, are booming, with China installing nearly 55 gigawatts, 14 percent more than in 2020, according to the National Energy Administration. Wind power, on the other hand, fell behind solar due to the expiration of subsidies for onshore wind farms. New wind capacity fell by a third compared to 2020, to just under 48 gigawatts. By comparison, just under 26 gigawatts of photovoltaic capacity were installed in the EU in 2021, also a record.

Beijing aims to achieve a total wind and solar capacity of 1,200 GW by 2030 – almost twice the capacity at the end of 2021 (635 GW). The share of non-fossil fuels in China’s total power consumption is expected to rise from 20 percent in 2020 to 25 percent by 2030. However, this also means that three-quarters of power will still be generated from fossil fuels in 2030. That, in turn, still means mainly: coal. Around 60 percent of China’s power still comes from coal.

Changing that is not so simple. Power plants are huge capital investments; new plants, in particular, could theoretically run for decades. Moreover, the coal-fired power sector is dominated by cumbersome state-owned companies that have supplied China with power for decades and maintain strong ties to local governments.

When China began its opening-up policy in the late 1970s, which sparked unprecedented economic growth, the country initially expanded the power sector based on the existing inefficient system at the time, which quickly was overwhelmed. The 1990s were marked by frequent regional power outages. As a result, the government began to restructure the sector. Power generation was partially opened up to private and foreign investors, and state-owned power giants were repeatedly restructured. Some of them floated subsidiaries or parts of their shares on the stock market, sometimes even in New York, such as Huaneng Power International.

Transmission and distribution of power, however, remains under state control to this day. Beijing gradually merged the country’s power grids, which had remained fragmented for decades. Today, the largest grid operators are the former monopoly State Grid Corporation and China Southern Power Grid.

In the People’s Republic, electricity rates are also traditionally controlled by the state. This contributed to the power crisis of 2021. Power producers were unable to pass on rapidly rising commodity prices to their customers and scaled back output. In October, the government reacted. Although it did not liberalize prices, it did loosen controls. Electricity rates for the industry were henceforth allowed to fluctuate by up to 20 percent on either side of a set benchmark. Previously, they were allowed to rise 10 percent or drop 15 percent. For agriculture and the residential sector, rates remained the same. Since then, market prices in many regions have risen to their regionally upper limit, for example in Hebei, Shaanxi, and Hainan.

Although the relaxation slightly eases the burden on power producers, it is by no means a revolution. The state remains in charge – and apparently does not want to burden its power-intensive industry with realistically high electricity rates. Many power plants will still operate at a loss, expects Yan Qin, Lead Carbon Analyst at data provider Refinitiv. The increase is not enough to fully offset the rise in fuel costs, he says. “Producers who are highly energy-intensive but not cost-competitive might be squeezed out of the market,” Penny Chen, Senior Director of Asia-Pacific corporates at Fitch, told South China Morning Post. “This is part of the overall structural reform for the economy to evolve towards more sustainable and higher-value-added businesses.”

Reforming the Chinese power sector is vital to achieving the country’s climate goals, most observers agree. That’s because power generators account for about 41 percent of China’s CO2 emissions, according to the China Electricity Council. The sector could achieve the CO2 turnaround as early as 2028, the CEC recommended last week – two years ahead of the previously targeted emissions peak in 2030. For 2022, however, the CEC first expects power consumption to grow by five to six percent. The International Energy Agency (IEA) then expects growth in power consumption to slow to 4.5 percent between 2022 and 2024 – due to greater energy efficiency and slower economic growth.

It is unclear how the growth in power consumption will be managed in the future. In 2021, many provinces were at risk of missing the power consumption targets issued by Beijing – and rationed power as a result. That was the second cause of the power crisis. In the future, Beijing no longer wants to base its climate-relevant targets for provinces or industries on absolute power consumption, but instead cap CO2 emissions (China.Table reported). But no details have been provided so far.

One problem for the transformation in China is the large number of company-owned power plants. These are located on company production sites to provide them with power. According to the Global Energy Monitor (GEM), 132 gigawatts (GW) of such coal-fired capacity were operated in China in January 2021, 13 percent of China’s total coal power capacity. 85 percent of this capacity supplies just three heavy industrial sectors, according to GEW: Aluminum, Iron and Steel, and Mining and Metals.

The problem: These power plants are particularly dirty and, in some cases, violate regulations. According to a study by the climate information service Carbon Brief, the government already branded these power plants for their reeking smokestacks during the smoggy winter of 2013 and banned new construction in protected areas such as the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Existing sites were ordered to switch from coal to gas. In 2015, Beijing decided to phase out its most polluting captive power plants. Many of these power plants were simply built before they received permits – with lower efficiency and higher pollutant emissions than public power plants. Plant management is also below the standard of public power plants and will be brought into line.

But these rules were never actually enforced, and the construction of corporate power plants continued unabated. In Shandong alone, 110 such power plants were built illegally between 2013 and 2017, according to Carbon Brief. Nine out of ten of these plants were built by two aluminum conglomerates alone, Weiqiao Pioneering Group and Xinfa Group. In 2020, Shandong closed 28 of these sites. But the problem remains. In October 2021, the Central Ecological and Environment Inspection Team (CEEIT) blamed factory power plants for China’s inability to meet its coal consumption targets.

Now, China is trying to contain such power plants with the help of the new Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). More than a third of the sites covered by the ETS belong to the group of problematic factory power plants. Of these, 105 are located in Shandong alone.

Because it was so difficult to close these power plants through administrative measures, “carbon pricing could be an efficient approach to solve the problem,” Carbon Brief quoted Chen Zhibin of consulting firm Sino-Carbon as saying. Li Lina of Adelphi told Carbon Brief that even the public power sector has pushed to include factory power plants in the CO2 market for “fair play” reasons. It remains to be seen how much effect this will have.

Apart from that, there are also numerous other problems. For example, despite some improvement in lifespan and transmission rates, the utilization rate of renewables is still insufficient. Total wind and solar power capacity accounted for only 9.5 percent of total power generation in 2020, although their combined installed capacity accounted for 18.8 percent of total capacity. Coal- and natural gas-fired power plants accounted for two-thirds of total capacity. In many places, they are given priority over green power. To change that, the provincial system that favors long-standing coal-fired power operators must be broken up. China is also investing in storage capacity for green power, which could also improve the situation.

The biggest threat to China’s climate targets, however, is the huge pipeline of new coal-fired power plants approved by many provinces. Various reports speak of hundreds of gigawatts. And it remains unclear if these power plants will be built – or if the government will ultimately stop them. There is much talk of a tug-of-war between Beijing and local governments. Hopefully, Beijing will emerge victoriously.

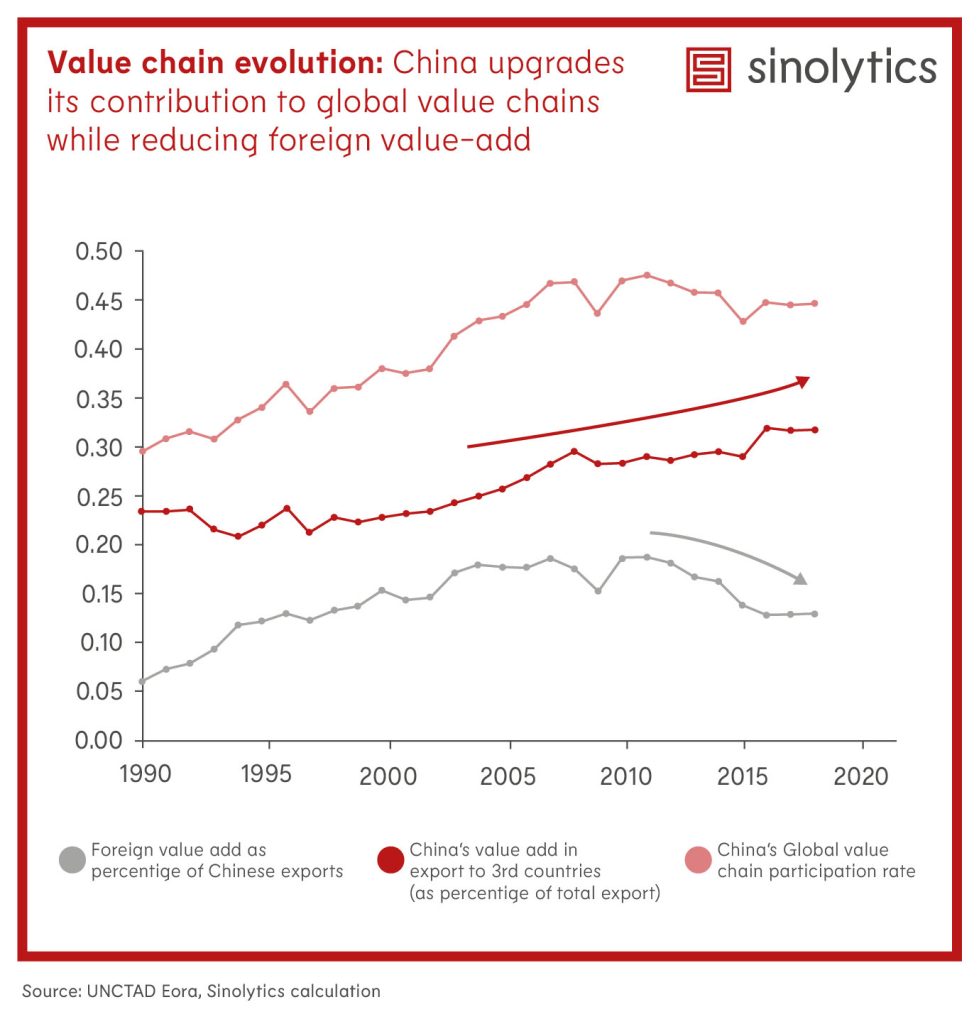

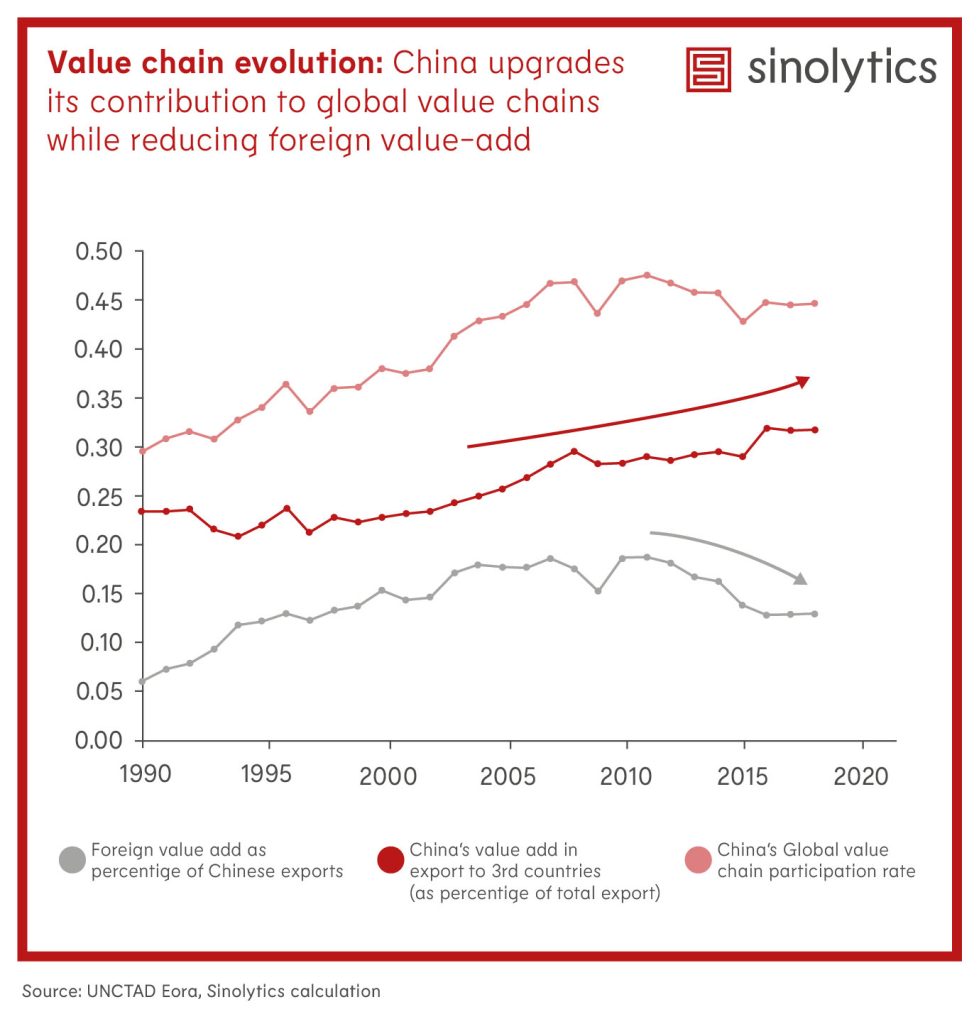

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in China.

Former Secretary of State Miguel Berger is to become the new German ambassador to China. This was reported to China.Table from political circles in Berlin. He succeeds Jan Hecker, who unexpectedly passed away in September (China.Table reported). The Federal Cabinet, i.e. the round of all ministers, is responsible for filling ambassadorial posts. It is made on the proposal of the Foreign Office. The ministry refused any comment on the appointment on Tuesday.

Berger would be a high-profile appointment for the important post in Beijing. He has previously held senior positions at the State Department dealing with numerous sensitive matters, including global trade, climate and energy, and Middle East policy. His career stints have included the United Nations and the Representative Office in the Palestinian Territories.

Berger was Secretary of State from May 2020 until shortly after the 2021 parliamentary elections. Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, however, appointed Andreas Michaelis to the post of state secretary, who had previously been Germany’s ambassador to London, immediately after taking office. Berger’s swift removal earned Baerbock some criticism, although it is not unusual for ministers to fill key positions with party associates after a change of government. Now Berger would again be given a suitably high position.

The embassy in Beijing is one of the most important German missions abroad, along with Washington and Paris. After Hecker’s death shortly before the election, it was expected that the old government would not immediately appoint a replacement and would leave the decision to its successor. fin

The takeover of the German semiconductor specialist Siltronic by the Taiwanese Globalwafers Group has fallen through. Globalwafers had obtained all the necessary approvals, including that of the Chinese competition authority. Only the approval of the German Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection had failed to materialize, preventing Siltronic’s acquisition. The deadline for submission passed on January 31. “It was not possible to complete all the necessary review steps as part of the investment review,” explained a ministry spokeswoman. “this applies in particular to the review of the antitrust approval by the Chinese authorities, which was only granted last week.”

Munich-based Siltronic is one of the leading manufacturers of silicon wafers for semiconductors and chips. The 4.4 billion euro deal would have made Globalwafers the world’s second-largest manufacturer and supplier of silicon wafers after Japan’s Shin Etsu Group (China.Table reported). However, the takeover would have required clearance from German authorities proving that foreign investment in domestic companies is not expected to harm public order and state security. Siltronic employs around 4000 people and has production facilities in Freiberg, Saxony, among other places. fpe

Analysts at the think tank European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) stated the EU needs to counter economic pressure from China more effectively. In a report published on Tuesday, ECFR recommends further steps in addition to the planned anti-coercion instrument (ACI). A single instrument alone can guarantee success, the analysts write. “The EU needs to develop a comprehensive agenda for the geo-economic era – including an ACI that, in grave cases of economic coercion, acts as both a deterrent and a measure of last resort.” ECFR had provided important impetus to the ACI development process with its own task force.

The economic coercion attempts against Europe are on a deeply concerning path, the experts wrote. Beijing would now interfere in the EU market as part of the diplomatic dispute with Lithuania. The report suggests the establishment of an “EU Resilience Office” that could monitor and assess potential economic coercion attempts by third countries. The report also advocates reforming the EU Blocking Statute to counter indirect sanctions from China.

The ACI has gained new urgency in light of the trade dispute between Lithuania and China. Brussels still wants to advance the new instrument during the French EU Council presidency. ari

The popular gay mobile dating app Grindr has been pulled from app stores in China. According to reports, Grindr had already been removed from Apple’s app store last Thursday. This was reported by Qimai, a research company specializing in mobile communications. The dating app was also no longer available on Android and on platforms operated by Chinese companies at the beginning of the week. In contrast, Grindr competitors such as the Chinese app Blued are still available for download.

For a while, Grindr was even Chinese. However, Beijing Kunlun Tech had sold the app to investors two years ago following pressure from US authorities. Washington feared that app data accumulated in the US could be misused and thus pose a threat to national security.

Homosexuality has no longer been a punishable offense in China since 1997. In the middle of last year, Li Ying became the first female soccer player in China to come out as homosexual (China.Table reported). However, same-sex marriage has still not been introduced and LGBTQ issues remain taboo. Homosexual love affairs are also not allowed to be shown in movies. Last Tuesday, China’s Internet authority announced a month-long campaign to crack down on rumors, pornography and other “sensitive web content.” The official goal is to “create a civilized, healthy, festive and auspicious online atmosphere.” rad

China has allowed certain cities and companies to test blockchain applications despite a blanket ban on crypto. According to a government statement, China has selected 15 pilot zones and identified several areas of application to “carry out the innovative application of blockchain” technology. The pilot zones include areas in China’s major cities of Beijing and Shanghai, as well as Guangzhou and Chengdu in the southern Guangdong and Sichuan provinces respectively, according to a statement on the Cyberspace Administration’s official WeChat social media account.

Apart from the pilot zones, 164 entities, including hospitals, universities, and companies such as SAIC-GM-Wuling Automobile Co., China National Offshore Oil Corp, Beijing Gas Group Co., and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Ltd were selected to carry out blockchain pilot projects. The entities will conduct the projects in fields such as manufacturing, energy, government and tax services, law, education, health, trade and finance, and cross-border finance.

All pilot zones should prioritize the adoption of blockchain software and hardware technologies and products with interoperability and sustainable development capabilities, the release said.

Chinese authorities have long considered Bitcoin and other digital currencies a threat to the stability of the Chinese economy (China.Table reported). Therefore, all crypto transactions have been declared illegal. rtr/ari

China has achieved an impressive economic catch-up since the 1980s. The number of people living in absolute poverty has fallen by almost 800 million, and the poverty rate (measured against an international poverty line of $1.90 per day) has dropped below 0.5 percent of the population.

But in order to further boost the population’s income, Beijing has to break new ground. After all, the key to success has so far been sustained economic growth and the integration of the Chinese economy into international value chains. China’s current situation, however, offers only meager prospects for growth and income gains for the poor.

On the one hand, China’s technological capabilities and the competitiveness of its leading companies are comparable to those of high-income countries, and its highest-performing schools and students are among the best in the world. But these capabilities are not broadly distributed. For example, the dispersion of productivity levels between Chinese companies is high. The average education level of the workforce is low compared to high-income countries, and access to proper education remains unequally distributed. China needs to pay more attention to these inequalities.

Market-oriented reforms could be an important catalyst for greater diffusion of technological skills and better access to high-quality services. For businesses, aligning conditions for access to finance and land could help promising small and medium-sized enterprises to grow and create the jobs of the future. Removing remaining hukou restrictions on labor mobility could facilitate access to better education and health services in urban areas for the current generation of school children, improving social mobility and economic opportunities. Over time, this would help reduce the risk of skilled labor shortages, including in the urban service sector, which is likely to drive future productivity growth.

China’s administrative capacity is an advantage in the transition to a high-income country, but the government’s role in aiding the poor and weak will have to change. China’s poverty line is below the level of most middle-income countries and is less than half of the $5.50 per day that is typical for such countries. Introducing a higher threshold would change the profile of the poor: At $5.50, about one-third of the roughly 180 million poor would live in urban areas, and many of them would be informal nonagricultural migrant workers. These groups are more likely to experience temporary poverty, associated with periods of unemployment and expenditures on health and education. Social policy would need to take these differences into account, just as targeted poverty reduction had been based on an evaluation of the needs of households in rural areas.

After eliminating absolute poverty, China has set 2035 as the target date for achieving common prosperity. This means providing all Chinese citizens with the opportunity to enjoy a reasonable living quality. Ensuring equal access to education, health care, and other services; using market signals and competition to promote innovation and technology diffusion; and repeatedly adjusting government policies to ensure that social transfers target key vulnerabilities and help China’s citizens manage the risks of rapid socioeconomic change – these are the lessons of the past 40 years. They will also continue to serve China on the path ahead.

Maria Ana Lugo is a Senior Economist at the Poverty and Equity Practice of the World Bank for China, Mongolia, and Korea, East Asia, and the Pacific Region. Martin Raiser is the Country Director for China and Mongolia, and Director for Korea. Ruslan Yemtsov is the Human Development Program Leader for China, Mongolia and Korea.

Martin Raiser will discuss the topic “After 40 years of poverty reduction in China: What are the challenges?” at the Global China Conversations of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel) on Thursday. China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

Gerald Tropper is the new Co-CFO at Beijing Foton Daimler Automotive in Beijing. Until December, Tropper was CFO for Daimler Truck China Ltd., also in Beijing.

Diana Vidal joined Formel D Group in Beijing as International Claims Manager at the beginning of the year. Vidal was previously a project assistant at the AHK in Beijing.

The tiger year has also reached the underwater: Here, female artists perform a mermaid dance at the aquarium in Hefei, East China’s Anhui province, to celebrate the Lunar New Year.

“The Winter Games are a huge publicity event for China,” says Hans-Martin Renn. The German architect helped design a ski jump in the host city of Zhangjiakou – a daring undertaking at times, as he told Marcel Grzanna in today’s interview. Before the planning conferences could even begin, not only phones had to be turned over, but even all ownership rights to the submitted designs.

However, Renn was well-prepared for the drinking spree with his Chinese business partners. He had poured down “all the water and soup on the table between toasts”. It paid off: In the end, his company’s concept won the bid. Now the ski jump stands tall in the mountains northwest of Beijing and will be the venue for the Winter Games on February 3.

As it is well known, the snow around the ski jump came from snow cannons, which in turn run on electricity. A most unfortunate fact, given the high priority placed on climate protection and air pollution control. Most of China’s power is still generated from coal, after all. It is fired by large and sluggish state-owned companies, still favored by the government in spite of crises and bottlenecks. If China wants to achieve its climate goals, this situation has to be broken up, writes Christiane Kuehl. A good start would be to effectively stop the planned construction of a whole series of new coal-fired power plants.

Meanwhile, China.Table has learned from well-informed circles in the capital who the new German ambassador to Beijing will be. The Foreign Ministry has chosen Miguel Berger. The high-ranking diplomat lost his position as Secretary of State in the party-political castling that followed the election. From the looks of it, he will be heading to the Far East – taking up a challenging post that requires a great deal of finesse.

Mr. Renn, is the construction of a ski jump in the Chinese province one of the last great adventures of our time?

There is some truth to that. But as is the case with many adventures, they are extremely exciting at first, but after a while everything becomes normal. In the end, it’s a task that has to be accomplished. Especially since there aren’t as many emotions involved as when we built the ski jump in Oberstdorf a few years ago. Of course, I have a completely different connection in this case. And I haven’t been back to China since the start of the pandemic anyway.

What was the tricky part of building the ski jump at Zhangjiakou?

My responsibility was to determine the profile of the ski jump and how it would fit into the landscape. My office has very good expertise in 3D planning. Furthermore, the assignment included the planning of all ski jumping-related issues such as infrastructure, construction and compliance with standards. The topography at 1700 meters above sea level was a challenge because the outrun of the ski jump is located in a hollow between two hills. But what concerned me much more was the question of what should happen to the village that was located in this hollow.

There probably haven’t been many options.

I was told that it was being removed. And in fact, a year later, there was no house left. The people supposedly got an apartment somewhere else and two years’ salary on top of that. But that could not have been much. The people’s economic status suggested as much.

You were involved in the planning of the facility as commission director and architect on behalf of the FIS. Who was sitting across from your panel of experts on the Chinese side?

They were representatives of the BOCOG organizing committee and Communist Party officials, both from provincial and district levels. Also, the future operator of the facility.

What’s it like to confer about ski jumps with people who have absolutely no idea what it involves?

The overall approach was highly professional, as was the case with the awarding of the architectural planning contract, where I was part of the jury. Each participant was provided with simultaneous translation into his or her national language as well as a personal minute-taker. What was new for me, however, was that we all had to hand over our cell phones at the door.

Why?

They probably wanted to ensure that communication would only take place via the state organs. If you look at the big picture, you can perhaps understand that. The Winter Games are a huge publicity event for China. Evidently, they leave nothing to chance.

Was the event classified as ‘top secret’?

Apparently, everything that took place in the room was a kind of intellectual government property and enjoyed the highest level of priority. This included that all facility designs brought in from all over the world became Chinese property. Everyone had to fully cede their intellectual property rights. This also included all architects of the rejected designs. That’s not really common practice. But those were rules that were clearly communicated from the very beginning.

Perhaps another ski jump will be built later elsewhere in China based on these confiscated designs.

That may be, but I consider confiscated to be the wrong word. Everyone involved was informed about this in advance and knew what they were getting into.

You could say that you were almost lucky you didn’t submit a design of your own.

Such a project would have been out of our office’s league. It may be tempting to take part in such a bid. But when you see how much effort the bidders put into their presentations alone, it was actually a relief not to have taken part.

Has nothing actually ever leaked to the outside world during the whole project?

I am not aware of this. That is even though all experts openly discussed their opinions on the drafts. But why certain decisions were made in the end is beyond me.

Could you give an example?

Well, I was the only one in a panel of about 25 experts who favored a design of the entire facility with a kind of circular walk. I really liked this urban idea of enclosing the ski jump, the biathlon facility and the cross-country ski trail with a kind of Chinese wall and providing them with different entrance areas.

And?

This exact design was selected, even though other designs received greater support.

Maybe because German cities are popular in China and you as a German represented this relation.

That may be. In any case, I noticed the high respect of the Chinese for “Made in Germany”. But also their disappointment about the diesel scandal that surfaced at the time. ‘We never thought the Germans would cheat,’ I was told, often and unprompted. I don’t think that the executives who were involved in this are aware of the damage they caused, even to this day.

China is facing criticism, including for its treatment of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Were there moments when you got a queasy feeling about helping the Chinese government build one of the Olympic monuments?

Of course, I asked myself that question. But in the end, I was also just a cog in the wheel. If I hadn’t done it, it would have been someone else. I am not responsible for the framework conditions. It’s not about making a profit, it’s about ensuring that the sport can be carried out properly. The thoughts I had when I set foot on Chinese soil for the first time were of a different sort. I noticed all the cameras and the thousands of police officers. It got me thinking about what would happen if you couldn’t leave the country.

The IOC praises the sustainability of the Olympic Games. What about the sustainability of the ski jump venue?

At least there were wind turbines everywhere on the way from Beijing to Zhangjiakou. That surprised me. As far as the construction of the venue is concerned, I am not aware of any particularly sustainable elements. It is possible that the ski jumping arena will also be used for other sports. A soccer field has been built in the out-run area. I think that sustainability should not be measured by whether any ski jumping takes place in the future, but rather if the many tourist investments around the sports facilities will be accepted. The ski jump has become a real tourist attraction. From the restaurant platform, people can then marvel at what sports are now possible in their country.

Did you also have to celebrate the successful sounding of the designs with the cadres in Chinese tradition?

Oh, yes. At some point, people stopped drinking from glasses and instead drank straight from the carafes. I sat right next to the future operator, a massive guy with Mongolian roots. Fortunately, I was mentally prepared for such a binge. I poured down all the water and soup available in between toasts. The next day, I was a hero to him. Others from the delegation, on the other hand, were not so lucky.

Welcome to China.

That’s just the culture there. At the Oktoberfest, business partners also drink jugs of beer and later dance on the tables.

Architect Hans-Martin Renn, 55, from Fischen in the German Allgäu region, is Chairman of the subcommittee for ski jumping hills of the International Ski Federation’s (FIS). When the organizers of the Winter Olympics in Beijing (February 4 to 20) asked the federation for assistance in designing a suitable venue for the Nordic skiing competitions of ski jumping and cross-country skiing as well as the biathlon, Renn traveled to the People’s Republic of China for the first time in 2017. With his architectural office, he also supported the construction of the venue in Zhangjiakou, China.

Smokestacks and solar farms, coal-fired power and wind power: In China’s power sector, too, the past and the future are wrestling with each other. The world is worried about a huge pipeline of planned coal-fired power plants in the country. And at the same time, China is building wind and solar power plants like no other country. In 2021, wind and solar farms accounted for more than half of the new power capacity connected to the grid – for the fifth year in a row. Photovoltaics, in particular, are booming, with China installing nearly 55 gigawatts, 14 percent more than in 2020, according to the National Energy Administration. Wind power, on the other hand, fell behind solar due to the expiration of subsidies for onshore wind farms. New wind capacity fell by a third compared to 2020, to just under 48 gigawatts. By comparison, just under 26 gigawatts of photovoltaic capacity were installed in the EU in 2021, also a record.

Beijing aims to achieve a total wind and solar capacity of 1,200 GW by 2030 – almost twice the capacity at the end of 2021 (635 GW). The share of non-fossil fuels in China’s total power consumption is expected to rise from 20 percent in 2020 to 25 percent by 2030. However, this also means that three-quarters of power will still be generated from fossil fuels in 2030. That, in turn, still means mainly: coal. Around 60 percent of China’s power still comes from coal.

Changing that is not so simple. Power plants are huge capital investments; new plants, in particular, could theoretically run for decades. Moreover, the coal-fired power sector is dominated by cumbersome state-owned companies that have supplied China with power for decades and maintain strong ties to local governments.

When China began its opening-up policy in the late 1970s, which sparked unprecedented economic growth, the country initially expanded the power sector based on the existing inefficient system at the time, which quickly was overwhelmed. The 1990s were marked by frequent regional power outages. As a result, the government began to restructure the sector. Power generation was partially opened up to private and foreign investors, and state-owned power giants were repeatedly restructured. Some of them floated subsidiaries or parts of their shares on the stock market, sometimes even in New York, such as Huaneng Power International.

Transmission and distribution of power, however, remains under state control to this day. Beijing gradually merged the country’s power grids, which had remained fragmented for decades. Today, the largest grid operators are the former monopoly State Grid Corporation and China Southern Power Grid.

In the People’s Republic, electricity rates are also traditionally controlled by the state. This contributed to the power crisis of 2021. Power producers were unable to pass on rapidly rising commodity prices to their customers and scaled back output. In October, the government reacted. Although it did not liberalize prices, it did loosen controls. Electricity rates for the industry were henceforth allowed to fluctuate by up to 20 percent on either side of a set benchmark. Previously, they were allowed to rise 10 percent or drop 15 percent. For agriculture and the residential sector, rates remained the same. Since then, market prices in many regions have risen to their regionally upper limit, for example in Hebei, Shaanxi, and Hainan.

Although the relaxation slightly eases the burden on power producers, it is by no means a revolution. The state remains in charge – and apparently does not want to burden its power-intensive industry with realistically high electricity rates. Many power plants will still operate at a loss, expects Yan Qin, Lead Carbon Analyst at data provider Refinitiv. The increase is not enough to fully offset the rise in fuel costs, he says. “Producers who are highly energy-intensive but not cost-competitive might be squeezed out of the market,” Penny Chen, Senior Director of Asia-Pacific corporates at Fitch, told South China Morning Post. “This is part of the overall structural reform for the economy to evolve towards more sustainable and higher-value-added businesses.”

Reforming the Chinese power sector is vital to achieving the country’s climate goals, most observers agree. That’s because power generators account for about 41 percent of China’s CO2 emissions, according to the China Electricity Council. The sector could achieve the CO2 turnaround as early as 2028, the CEC recommended last week – two years ahead of the previously targeted emissions peak in 2030. For 2022, however, the CEC first expects power consumption to grow by five to six percent. The International Energy Agency (IEA) then expects growth in power consumption to slow to 4.5 percent between 2022 and 2024 – due to greater energy efficiency and slower economic growth.

It is unclear how the growth in power consumption will be managed in the future. In 2021, many provinces were at risk of missing the power consumption targets issued by Beijing – and rationed power as a result. That was the second cause of the power crisis. In the future, Beijing no longer wants to base its climate-relevant targets for provinces or industries on absolute power consumption, but instead cap CO2 emissions (China.Table reported). But no details have been provided so far.

One problem for the transformation in China is the large number of company-owned power plants. These are located on company production sites to provide them with power. According to the Global Energy Monitor (GEM), 132 gigawatts (GW) of such coal-fired capacity were operated in China in January 2021, 13 percent of China’s total coal power capacity. 85 percent of this capacity supplies just three heavy industrial sectors, according to GEW: Aluminum, Iron and Steel, and Mining and Metals.

The problem: These power plants are particularly dirty and, in some cases, violate regulations. According to a study by the climate information service Carbon Brief, the government already branded these power plants for their reeking smokestacks during the smoggy winter of 2013 and banned new construction in protected areas such as the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Existing sites were ordered to switch from coal to gas. In 2015, Beijing decided to phase out its most polluting captive power plants. Many of these power plants were simply built before they received permits – with lower efficiency and higher pollutant emissions than public power plants. Plant management is also below the standard of public power plants and will be brought into line.

But these rules were never actually enforced, and the construction of corporate power plants continued unabated. In Shandong alone, 110 such power plants were built illegally between 2013 and 2017, according to Carbon Brief. Nine out of ten of these plants were built by two aluminum conglomerates alone, Weiqiao Pioneering Group and Xinfa Group. In 2020, Shandong closed 28 of these sites. But the problem remains. In October 2021, the Central Ecological and Environment Inspection Team (CEEIT) blamed factory power plants for China’s inability to meet its coal consumption targets.

Now, China is trying to contain such power plants with the help of the new Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). More than a third of the sites covered by the ETS belong to the group of problematic factory power plants. Of these, 105 are located in Shandong alone.

Because it was so difficult to close these power plants through administrative measures, “carbon pricing could be an efficient approach to solve the problem,” Carbon Brief quoted Chen Zhibin of consulting firm Sino-Carbon as saying. Li Lina of Adelphi told Carbon Brief that even the public power sector has pushed to include factory power plants in the CO2 market for “fair play” reasons. It remains to be seen how much effect this will have.

Apart from that, there are also numerous other problems. For example, despite some improvement in lifespan and transmission rates, the utilization rate of renewables is still insufficient. Total wind and solar power capacity accounted for only 9.5 percent of total power generation in 2020, although their combined installed capacity accounted for 18.8 percent of total capacity. Coal- and natural gas-fired power plants accounted for two-thirds of total capacity. In many places, they are given priority over green power. To change that, the provincial system that favors long-standing coal-fired power operators must be broken up. China is also investing in storage capacity for green power, which could also improve the situation.

The biggest threat to China’s climate targets, however, is the huge pipeline of new coal-fired power plants approved by many provinces. Various reports speak of hundreds of gigawatts. And it remains unclear if these power plants will be built – or if the government will ultimately stop them. There is much talk of a tug-of-war between Beijing and local governments. Hopefully, Beijing will emerge victoriously.

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in China.

Former Secretary of State Miguel Berger is to become the new German ambassador to China. This was reported to China.Table from political circles in Berlin. He succeeds Jan Hecker, who unexpectedly passed away in September (China.Table reported). The Federal Cabinet, i.e. the round of all ministers, is responsible for filling ambassadorial posts. It is made on the proposal of the Foreign Office. The ministry refused any comment on the appointment on Tuesday.

Berger would be a high-profile appointment for the important post in Beijing. He has previously held senior positions at the State Department dealing with numerous sensitive matters, including global trade, climate and energy, and Middle East policy. His career stints have included the United Nations and the Representative Office in the Palestinian Territories.

Berger was Secretary of State from May 2020 until shortly after the 2021 parliamentary elections. Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, however, appointed Andreas Michaelis to the post of state secretary, who had previously been Germany’s ambassador to London, immediately after taking office. Berger’s swift removal earned Baerbock some criticism, although it is not unusual for ministers to fill key positions with party associates after a change of government. Now Berger would again be given a suitably high position.

The embassy in Beijing is one of the most important German missions abroad, along with Washington and Paris. After Hecker’s death shortly before the election, it was expected that the old government would not immediately appoint a replacement and would leave the decision to its successor. fin

The takeover of the German semiconductor specialist Siltronic by the Taiwanese Globalwafers Group has fallen through. Globalwafers had obtained all the necessary approvals, including that of the Chinese competition authority. Only the approval of the German Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection had failed to materialize, preventing Siltronic’s acquisition. The deadline for submission passed on January 31. “It was not possible to complete all the necessary review steps as part of the investment review,” explained a ministry spokeswoman. “this applies in particular to the review of the antitrust approval by the Chinese authorities, which was only granted last week.”

Munich-based Siltronic is one of the leading manufacturers of silicon wafers for semiconductors and chips. The 4.4 billion euro deal would have made Globalwafers the world’s second-largest manufacturer and supplier of silicon wafers after Japan’s Shin Etsu Group (China.Table reported). However, the takeover would have required clearance from German authorities proving that foreign investment in domestic companies is not expected to harm public order and state security. Siltronic employs around 4000 people and has production facilities in Freiberg, Saxony, among other places. fpe

Analysts at the think tank European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) stated the EU needs to counter economic pressure from China more effectively. In a report published on Tuesday, ECFR recommends further steps in addition to the planned anti-coercion instrument (ACI). A single instrument alone can guarantee success, the analysts write. “The EU needs to develop a comprehensive agenda for the geo-economic era – including an ACI that, in grave cases of economic coercion, acts as both a deterrent and a measure of last resort.” ECFR had provided important impetus to the ACI development process with its own task force.

The economic coercion attempts against Europe are on a deeply concerning path, the experts wrote. Beijing would now interfere in the EU market as part of the diplomatic dispute with Lithuania. The report suggests the establishment of an “EU Resilience Office” that could monitor and assess potential economic coercion attempts by third countries. The report also advocates reforming the EU Blocking Statute to counter indirect sanctions from China.

The ACI has gained new urgency in light of the trade dispute between Lithuania and China. Brussels still wants to advance the new instrument during the French EU Council presidency. ari

The popular gay mobile dating app Grindr has been pulled from app stores in China. According to reports, Grindr had already been removed from Apple’s app store last Thursday. This was reported by Qimai, a research company specializing in mobile communications. The dating app was also no longer available on Android and on platforms operated by Chinese companies at the beginning of the week. In contrast, Grindr competitors such as the Chinese app Blued are still available for download.

For a while, Grindr was even Chinese. However, Beijing Kunlun Tech had sold the app to investors two years ago following pressure from US authorities. Washington feared that app data accumulated in the US could be misused and thus pose a threat to national security.

Homosexuality has no longer been a punishable offense in China since 1997. In the middle of last year, Li Ying became the first female soccer player in China to come out as homosexual (China.Table reported). However, same-sex marriage has still not been introduced and LGBTQ issues remain taboo. Homosexual love affairs are also not allowed to be shown in movies. Last Tuesday, China’s Internet authority announced a month-long campaign to crack down on rumors, pornography and other “sensitive web content.” The official goal is to “create a civilized, healthy, festive and auspicious online atmosphere.” rad

China has allowed certain cities and companies to test blockchain applications despite a blanket ban on crypto. According to a government statement, China has selected 15 pilot zones and identified several areas of application to “carry out the innovative application of blockchain” technology. The pilot zones include areas in China’s major cities of Beijing and Shanghai, as well as Guangzhou and Chengdu in the southern Guangdong and Sichuan provinces respectively, according to a statement on the Cyberspace Administration’s official WeChat social media account.

Apart from the pilot zones, 164 entities, including hospitals, universities, and companies such as SAIC-GM-Wuling Automobile Co., China National Offshore Oil Corp, Beijing Gas Group Co., and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Ltd were selected to carry out blockchain pilot projects. The entities will conduct the projects in fields such as manufacturing, energy, government and tax services, law, education, health, trade and finance, and cross-border finance.

All pilot zones should prioritize the adoption of blockchain software and hardware technologies and products with interoperability and sustainable development capabilities, the release said.

Chinese authorities have long considered Bitcoin and other digital currencies a threat to the stability of the Chinese economy (China.Table reported). Therefore, all crypto transactions have been declared illegal. rtr/ari

China has achieved an impressive economic catch-up since the 1980s. The number of people living in absolute poverty has fallen by almost 800 million, and the poverty rate (measured against an international poverty line of $1.90 per day) has dropped below 0.5 percent of the population.

But in order to further boost the population’s income, Beijing has to break new ground. After all, the key to success has so far been sustained economic growth and the integration of the Chinese economy into international value chains. China’s current situation, however, offers only meager prospects for growth and income gains for the poor.

On the one hand, China’s technological capabilities and the competitiveness of its leading companies are comparable to those of high-income countries, and its highest-performing schools and students are among the best in the world. But these capabilities are not broadly distributed. For example, the dispersion of productivity levels between Chinese companies is high. The average education level of the workforce is low compared to high-income countries, and access to proper education remains unequally distributed. China needs to pay more attention to these inequalities.

Market-oriented reforms could be an important catalyst for greater diffusion of technological skills and better access to high-quality services. For businesses, aligning conditions for access to finance and land could help promising small and medium-sized enterprises to grow and create the jobs of the future. Removing remaining hukou restrictions on labor mobility could facilitate access to better education and health services in urban areas for the current generation of school children, improving social mobility and economic opportunities. Over time, this would help reduce the risk of skilled labor shortages, including in the urban service sector, which is likely to drive future productivity growth.

China’s administrative capacity is an advantage in the transition to a high-income country, but the government’s role in aiding the poor and weak will have to change. China’s poverty line is below the level of most middle-income countries and is less than half of the $5.50 per day that is typical for such countries. Introducing a higher threshold would change the profile of the poor: At $5.50, about one-third of the roughly 180 million poor would live in urban areas, and many of them would be informal nonagricultural migrant workers. These groups are more likely to experience temporary poverty, associated with periods of unemployment and expenditures on health and education. Social policy would need to take these differences into account, just as targeted poverty reduction had been based on an evaluation of the needs of households in rural areas.

After eliminating absolute poverty, China has set 2035 as the target date for achieving common prosperity. This means providing all Chinese citizens with the opportunity to enjoy a reasonable living quality. Ensuring equal access to education, health care, and other services; using market signals and competition to promote innovation and technology diffusion; and repeatedly adjusting government policies to ensure that social transfers target key vulnerabilities and help China’s citizens manage the risks of rapid socioeconomic change – these are the lessons of the past 40 years. They will also continue to serve China on the path ahead.

Maria Ana Lugo is a Senior Economist at the Poverty and Equity Practice of the World Bank for China, Mongolia, and Korea, East Asia, and the Pacific Region. Martin Raiser is the Country Director for China and Mongolia, and Director for Korea. Ruslan Yemtsov is the Human Development Program Leader for China, Mongolia and Korea.

Martin Raiser will discuss the topic “After 40 years of poverty reduction in China: What are the challenges?” at the Global China Conversations of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel) on Thursday. China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

Gerald Tropper is the new Co-CFO at Beijing Foton Daimler Automotive in Beijing. Until December, Tropper was CFO for Daimler Truck China Ltd., also in Beijing.

Diana Vidal joined Formel D Group in Beijing as International Claims Manager at the beginning of the year. Vidal was previously a project assistant at the AHK in Beijing.

The tiger year has also reached the underwater: Here, female artists perform a mermaid dance at the aquarium in Hefei, East China’s Anhui province, to celebrate the Lunar New Year.