Beijing propagates its image of China through sport, culture and language – but increasingly directly through advertisements in Western newspapers as well. More and more frequently, inserts are appearing in renowned foreign media. The goal: building more credibility and sympathy. Marcel Grzanna has traced the origins of CCP’s advertisements, which also appear throughout German and US media. His discovery: China’s state propaganda is delivered directly to the breakfast table with the newspaper.

Once upon a time, pictures of Mao Zedong taking a swim at the beach surfaced. Xi Jinping will hardly allow himself to be photographed in a similar situation. Our columnist Johnny Erling explains why China’s leadership nevertheless meets at a seaside resort, and why it is sometimes a venue for far-reaching geopolitical consequences. The popular beach of Beidaihe – just two hours by train northeast of Beijing – is also an important site for personnel decisions within the party. A generational shift is in store for the CCP. Except for Xi Jinping himself, who holds his office for life. Hardly any other member of the Chinese political elite will be allowed to travel to Beidaihe forever – at least not to the part of the beach cordoned off and reserved for the political nobility.

Have a restful weekend.

For years, the U.S. branch of China’s news agency Xinhua had successfully evaded its compulsory registration as a foreign outlet in the United States. Despite initial demands in 2018 by the Department of Justice in Washington, it took until early May this year before the state-run medium complied with the legal framework. U.S. authorities, who classify Xinhua as an advocacy group for the Chinese state and thus brand it a propaganda tool, can now finally track in detail how much money flows from the People’s Republic to financially support Xinhua’s activities throughout the US. Between March last year and April 2021, transactions amounted to around 8.6 million US dollars.

China Daily and foreign TV station CGTN, which equally represent and market the Communist Party line around the globe, missed their registration deadline and only filed as foreign missions last year. Through the extensive delay of the bureaucratic procedures, the People’s Republic was able to conceal the financial volume of its propaganda in the United States for a long time.

All Chinese institutions currently registered as foreign missions under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) received around 64 million US dollars from China last year. Almost six and a half times more than in 2016, back when the three media houses were not yet registered. No other country in the world spends this much on its lobbying efforts in the US. Most of it goes to influencing public opinion. According to the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP), an independent non-profit research organization in Washington dedicated to uncovering cash streams within US politics, Xinhua, China Daily and CGTN accounted for 80 percent of the US$64 million expenses. FARA has been in effect since 1938 when it was implemented by the US government to counter Nazi propaganda from Germany.

But what actually happens with the money? Conservative US media report that China Daily is a client of numerous newspapers and magazines, which in the past had placed ads or produced its own inserts in exchange for payments of six- to seven-figure dollar sums. Time Magazine, the Financial Times, Foreign Policy Magazine, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal are mentioned by name.

The publishers concerned are not particularly keen to talk about moneyed political clients from the authoritarian-ruled second-largest economy. After all, there is a risk of reputational damage among readers who consider it inappropriate that a government accused of genocide in Xinjiang and which has broken its contractual promises to preserve democratic civil rights in Hong Kong should be given a platform to write history as it sees fit.

This applies to the USA as well as to Germany. The Handelsblatt Media Group, for example, asks for understanding “that we do not comment on your questions”. This is because the Handelsblatt is one of China Daily’s many propaganda mouthpieces. At irregular intervals, the renowned business newspaper is accompanied by the insert “China Watch”. The multi-page product has the classic appearance of an ordinary newspaper.

Recently, readers of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) were also confronted with Chinese propaganda when the news agency Xinhua placed a full-page advertisement in mid-July to mark the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party. Although the content was marked as an advertisement, its layout did not look like an editorial piece by accident. The publisher of the Süddeutsche Zeitung also accepted similar requests from Chinese media in the past because it did not want to miss out on revenue. German leading media are especially valuable for Chinese propaganda because they offer a reputable guise. This boosts credibility.

The publishers always emphasize that their editorial and advertising departments work independently. “Political advertisements and pieces with strong opinions are always a balancing act for a publishing house, which we decide on after internal review. As it happened in this particular case. Ultimately, however, we gave priority to the free expression of opinion,” FAZ GmbH commented in a statement explaining its course of decision. Of course, FAZ GmbH reviews the advertising subjects and refuses those that obviously violate applicable law. “To prevent critical or provocative advertisements through a kind of preemptive censorship would at least be incompatible with our understanding of a legitimate and free expression of opinion in our democracy.”

Among China critics, this statement is not well received at all. “The justification of the FAZ makes matters even worse. The Xinhua ad praises 100 years of the CCP, but hides the millions of deaths at the hands of the CCP. This is neither ‘provocative’ nor ‘critical’, but simply an inhumane historical lie,” discerns Kai Müller of the International Campaign for Tibet (ICT).

China’s propaganda cleverly exploits those basic principles, whose very same application is severely punished in the People’s Republic. At the same time, the authors benefit from the fact that publishers around the world are under pressure and are in urgent need of advertisers. The Chinese government thus kills two birds with one stone, because in addition to spreading its narratives, it pushes the free media to the brink of a credibility crisis. A desirable goal for the Chinese government, which accuses foreign journalists of lies and distortions on a regular basis. Western media are a powerful and indispensable manifestation of democratic systems, after all. It’s a stroke of luck for Beijing, that a very part of this media creates a platform for a regime that labels democratic values as poison and opposes them bitterly.

The German Journalists’ Association (DJV) is also “not particularly happy” about the placement of such advertisements, but stresses that it is not an editorial decision whether an advertisement is published or not. It is the responsibility of the advertising departments of publishing houses. “We assume that the publishers’ legal advisors are aware of the ad contents prior to publishing and review them for possible contradictions to international law and human rights,” the association stated. For its part, the association does not fear any damage to the reputation of German journalism.

The fact that the quality of said ads or inserts does not meet journalistic standards of leading media hardly impacts the desired effect. Instead, the Chinese government intends to plant its message into the subconscious of the recipients through the permanent repetition of narratives. Without critical assessment, it is then able to solidify itself as legitimate arguments and change points of view. If this happens, the propaganda has already achieved its goal.

However, the US branch of Xinhua clearly downplays its ties to the Chinese Communist Party in its FARA application, even though, like China Daily or CGTN, Xinhua is controlled by the CCP. According to Chinese law, Xinhua is considered a ‘public institution’ subject to state supervision but operates as a separate legal entity. Only a “small portion of its operating funds” is financed by the Chinese government. “Xinhua is increasingly relying on its

own commercial and subscription revenues to sustain its global news operations,” the application states.

However, the millions sent from back home suggest that the revenue is apparently far from sufficient, calling into question the agency’s business model. If it isn’t propaganda, why doesn’t Xinhua decide to pack up under such business conditions?

In Germany, Xinhua also makes generous gestures that run counter to a profitable business. The agency provides its services to local editorial offices, in part, free of charge.

The border dispute between India and China has escalated once again over the recent months. In July, India began to increase its military presence in eastern Ladakh in the Himalayas, a region that overlaps with Kashmir and Tibet, by more than 50,000 soldiers to around 200,000. India is also said to have moved additional combat aircraft and advanced artillery to the region. According to Indian sources, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army has now also moved additional units to the Himalayas.

Indian intelligence and military officials speak of an increase in Chinese troop strength to around 50,000, most of whom are said to have been redeployed from Tibet to the high plains. The number is a significant leap: in June 2020, reports spoke of only around 15,000 troops in the area. At that time, a deadly confrontation between the two nations had taken place there in the Galwan Valley. Twenty Indian and four Chinese soldiers were killed.

Other developments are further fuelling the conflict: Since the beginning of July, a Chinese high-speed train has been operating for the first time, connecting Chengdu via Lhasa to the Arunachal Pradesh region, which both India and China lay claim on. This will reduce the travel distance from Chengdu to Lhasa alone from 48 hours to 13 hours. “If a scenario of a crisis happens at the China-India border, the railway will provide a great convenience for China’s delivery of strategic materials,” said Qian Feng, research director of the National Strategy Institute at Beijing’s Tsinghua University.

For years, China has been expanding its infrastructure along the border to Tibet in the Himalayas, including roads and runways for aircraft. Beijing is said to have invested almost 150 billion US dollars. India has also built over 1500 kilometers of roads between March 2018 and 2020, most of them in the states of Jammu, Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh.

The biggest problem for the balance of power: India increasingly finds itself on the economic defensive against China. Overall, India is lagging behind the People’s Republic in areas of infrastructure, education, health and international competitiveness, while the influence of the Chinese economy in India is growing.

For at least 750 years, the Indian economy stood superior to the Chinese. It was about 1750, 100 years later, when the West took the lead. Then, in the 1980s, China overtook India in economic power. In 1990, India’s gross domestic product (GDP) reached just over US$326 billion, while China’s GDP amounted to 396 billion U.S. dollars. In 2019, the last normal year before the pandemic, nearly 20 million tourists visited India. And more than 60 million came to China.

China has more than 60 million students, whereas India has less than 20 million. India owns nine brands in the top 500 global brands – China can boast 73. The market capitalization of stock exchanges in China is 2.2 times higher than in India. There is also a massive gap in the technologization of its societies: China has four times more televisions than India and as many as ten times more mobile phones. The People’s Republic has 188 cars per 1000 citizens, the US has 838. In India, it is only 20.

In 2020, China’s share of the global gross domestic product was 18.3 percent, adjusted for purchasing power. India, on the other hand, only had 6.7 percent. Could India still catch up to the leader? Hardly. If India were to grow at a whopping eight percent by 2041 and China just four percent, China would be at $5,300 billion – and India would still be more than 20 percent smaller at $4,000 billion.

The military balances also develop in accordance with the slow economic growth. According to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), China spends more than $260 billion annually on its military, while India spends only about $71 billion.

Military exercises by the Chinese navy in the Indian Ocean have also been a cause for concern in India for some time. India owns 150 warships and submarines and one aircraft carrier. In contrast, the People’s Republic of China has more than 350 warships and more than 50 submarines and two aircraft carriers, according to the latest military and security report by the US Department of Defense.

Economically, Beijing is also working ever more closely with India’s neighbors – with both enemies and allies – as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka welcome China’s engagement because it creates a counterweight to India’s neighbor in the region and creates more negotiating leverage to defend their own interests.

Pakistan, India’s hated adversary, particularly benefits from China’s investments – including in the expansion of its army. Most recently, India refused to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free trade agreement, because of China’s regional power ambitions. The member nations Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and the ten ASEAN states Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Brunei, Laos, Cambodia and Singapore only reached an agreement with China after long negotiations.

However, the Indians feared that Chinese products would flood the Indian market as a result of the massively lowered tariffs and local suppliers would be permanently put out of business as a result. India has already reacted with economic sanctions against China after the border dispute of last year. 59 Chinese apps such as WeChat and TikTok have been banned in the country for endangering India’s “national security and sovereignty”, authorities claimed.

In some respects, however, India is ahead of the People’s Republic, at least in terms of numbers: India will replace China as the world’s most populous country in the next decade. And unlike the Chinese, Indians are young. The proportion of the working-age population will remain high. Whether this will be an advantage or even a disadvantage in times of digitalization and automation is not yet clear.

To counter China’s expansion, India has been pushing economic partnerships and developed closer ties to the US in recent years. India, as a global powerhouse and security guarantor in the region, is the US’ most important partner in the Indo-Pacific region, US State Department spokesperson Ned Price said in February. However, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) tells a different story: While India’s FDI in the crisis year 2020 amounted to around 64 billion US dollars, according to UNCTAD, 149 billion US dollars went to China – without even including Hong Kong.

In order to avoid a geopolitical conflagration, Delhi and Beijing agreed in 1996 to ban the use of live ammunition in the border area. The partly unsettled course of the 3,500-kilometer-long Sino-Indian border has been a recurrent source of conflict since the border war of 1962, which China won without gaining any significant territory.

For the two Asian nuclear powers, it is not only a matter of principle but also of strategic control of resources, above all water. Important glaciers are located in the region. An official state border does not exist. Everything that is written dates back to British colonial times. Even in Mao’s time, the People’s Republic no longer recognized these border demarcations as binding.

On June 25, representatives of India and China held another round of diplomatic talks on the border dispute, but so far they have failed to produce any actual results. The effort shows, however, that neither side is interested in a war. The political and economic costs would be too high.

Congestion at China’s two main container ports of Shanghai and Ningbo worsens in the wake of the Covid related closure of a terminal. Around forty container ships were waiting at the outer anchorage off Ningbo Zhoushan Port on Thursday. It was about ten more than at the start of the week, news agency Reuters reported. Work was completely suspended at the Meidong terminal from Wednesday on after a worker tested positive for Covid-19. Restrictions were imposed on workers and ships at other terminals in Ningbo.

The first shipping companies reacted to the closure in Ningbo: French shipping line CMA CGM announced on Thursday that some ships would be diverted to Shanghai or port calls in Ningbo would simply be skipped, according to Reuters. According to a company statement, Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd expected delays to some planned sailings due to the temporary closure of the Meidong terminal.

Ports in Shanghai, which is located close to Ningbo, experienced the highest congestion in at least three years. About 30 ships were waiting for clearance outside the port of Yangshan, a major container terminal in Shanghai.

The important container traffic in and out of China has suffered several blows in recent months: At the end of July, the handling volume at eastern Chinese ports dropped, as they had to temporarily suspend operations due to typhoon In-Fa. At the end of May and June, the Chinese commercial port of Yantian was already closed due to Covid infections. The groundings of the container ship “Ever Given” in the Suez Canal in March also had massively impacted global container traffic.

If the closure of the port in Ningbo continues, world trade could suffer more than it had during the closure of the Port in Yantian. According to the Chinese Ministry of Transport, Ningbo handled 18.7 million containers in the first seven months of the year, more than any other port in the People’s Republic. ari

Since Beijing declared the National Security Law for Hong Kong last summer, 89,200 people have left the former British crown colony. According to government data released Thursday, the exodus has led to a 1.2 percent drop in the total population of about 7.39 million people.

Even before Hong Kong’s security law took effect last June, Hong Kong residents and expats were leaving the city because they saw no secure future. In the second half of 2019, for example, 50,000 people already emigrated from Hong Kong after the occasional brutal street protests.

Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s chief executive, said in late July that people were emigrating for a wide variety of personal reasons and that the city still offered “unlimited opportunities” after the implementation of the National Security Act and with support from mainland China. niw

Chinese authorities have singled out mahjong venues as a high transmission site in the recent Covid wave in the country. As a result, tens of thousands of the mahjong parlors across the country have now been closed, as news agency Bloomberg reported on Thursday. In the province of Jiangsu alone, more than 45,000 mahjong and card games venues have now been affected by the shutdown. Authorities in Beijing and at least four other provinces with elevated Covid numbers – Henan, Zhejiang, Hunan and Heilongjiang – followed suit.

According to the report, a 64-year-old woman in Yangzhou had spread the delta variant of the virus at a mahjong parlor. The woman had previously visited a relative in Nanjing, which was known to harbor a Covid cluster. She had then been to several mahjong venues in Yangzhou before testing positive for Covid-19, the report added. Mahjong is especially popular among the older demographic in China.

The virus cluster in Yangzhou had therefore also predominantly affected older people. Around 70 percent of those infected were older than 60, Bloomberg reported. According to the report, about two-thirds of the registered infections were attributable to the mahjong venues. In addition, the vaccination rate among the elderly in Yangzhou is only around 40 percent. Of the 448 people infected with Covid in the area, 23 had shown severe symptoms. Twelve infected are currently in critical condition. ari

Recent changes to procurement guidelines in China will hit medical equipment manufacturers such as Siemens, GE Healthcare and Philips the hardest, according to new details. Beijing had instructed local authorities to rely on more locally produced goods when procuring MRI and X-ray equipment, as well as surgical endoscopes and PCR testing equipment. Of the 315 product categories affected, 200 alone are located in the medical sector, according to details of the public procurement regulation recently published by Nikkei Asia.

Large foreign manufacturers such as Siemens, GE and Philips are at risk of losing sales as a result, the report continued. The regulation is also said to be aimed at forcing high-tech companies in the healthcare sector to relocate their production to China. A representative of an unnamed foreign trade association had told Nikkei that manufacturers fear that if they move production now, “technologies could fall into the hands of Chinese competitors.”

These new rules are based on regulations issued by China’s Ministry of Finance and Industry in May (as reported by China.Table). The new rules stipulate that domestically produced goods must account for 25 to 100 percent of public contracts, depending on the product category. According to the newspaper, it remains unclear whether the new regulation will also affect purchases by state-owned enterprises, hospitals and local authorities. nib

Chinese premium electric car manufacturer Nio plans to establish its own brand to compete on the mass market. This will put the company in direct competition with manufacturers such as Volkswagen and Toyota. “The relationship between Nio and our new mass brand will be similar to that between Audi and Volkswagen, or Lexus and Toyota,” company CEO William Li announced. Up until now, Nio, as a premium manufacturer of SUV vehicles ranging in the price range of equivalent to around 40,000 euros, mainly built cars for the same target group as Audi, BMW or Tesla.

On Thursday, Li said that Nio is preparing to launch two new models next year. In addition to the previously announced ET7 sedan, a more affordable model than Nio’s current ones is to be released. The new models, however, are not expected to compete in the lower end of the market, which is dominated by the Hongguang Mini of SAIC-GM-Wuling Automobile Co., whose vehicles cost the equivalent of 3,850 euros. niw

China’s top-level authorities have adopted a “five-year blueprint” to strengthen regulatory control over key economic sectors. The Communist Party Central Committee and the State Council released a policy document on the regulation of multiple fields, including digital economy, IT companies operating in the financial sector, artificial intelligence, Big Data, cloud computing, and food and drugs, as the Financial Times and Bloomberg reported.

The authorities’ goal is to ensure that “new business models develop in a healthy manner.” Beijing sees an “urgent need” for additional laws to regulate the education sector and resolving antitrust issues, as well as in the area of national security.

“We can’t draw too much insight about enforcement and the potential shape of crackdowns from one document or another,” Graham Webster, who leads the DigiChina project at the Stanford University Cyber Policy Center, told Bloomberg. A representative of consulting firm AgencyChina told the news agency that he believes the announcement gives investors a bitter insight into “future regulatory hotspots.” Uncertainty is deterring investors, he added.

This was further confirmed by Global fund managers to Reuters. “I think investors just don’t like the uncertainty of not knowing what’s the next shoe to drop,” said Mark Haefele, chief investment officer at UBS Global Wealth Management. Other fund managers see the crackdown of recent weeks and months as a “transitionary phase” rather than a change in policy, according to Reuters. Overall, foreign investors hold $800 billion worth of Chinese stocks and bonds. A year ago, this figure was 40 percent lower, according to the Financial Times. nib

Party chief Wang Dongfeng (王东峰) is the most powerful man in Beijing’s neighboring province of Hebei. He personally inspected all police checkpoints on July 30 on the roads leading to the sea at Beidaihe. China’s famous seaside resort, a 280-kilometer highway drive from Beijing, falls under the jurisdiction of his province. Wang expressed satisfaction with the checkpoints, which are equipped with cutting-edge high-tech. He considered them “key defense points to guarantee China’s social harmony and stability,” adding that combined air and ground defense and the use of science and technology such as “facial surveillance and artificial intelligence” can ward off threats. Wang was probably thinking particularly of protecting China’s State and Party leader Xi Jinping. Because Xi’s name is mentioned a total of seven times in the report on provincial leader Wang by Hebei Daily, published on August 2nd.

For those who didn’t know, Xi and his inner circle were on their way to Beidaihe for their annual summer break. This is where Beijing’s elite retreat every year to their villas hidden among pine and cedar forests on the Lotus Mountain above a western beach closed off to them. The political elite is the real target of the submissive report in the Hebei daily. China’s top leaders are so paranoid when it comes to their security and secrecy that they don’t even disclose if, how long and where they are vacationing. They just disappear off the face of the earth. Only the Foreign Ministry provides a little insight: on July 30, it made the following announcement on its website: “We are taking a summer break (暑期) from August 2 to 13.” This is the period when China’s leaders take a vacation.

But for those who read between the lines, the report on the party chief’s inspection is the first of two indirect clues Beijing’s party elite uses every year to publicly announce its departure to Beidaihe. This was revealed on August 10 by the well-connected news website Duowei Xinwen. So far, the second hint has always come shortly after their arrival at the seaside resort. Since 2000, China’s party leadership has granted a group of selected Chinese scientists a one-week special vacation in Beidaihe each year. China’s party chief personally sends two trusted subordinates of his politoffice to greet them on his behalf. This year, the well-established announcement procedures that the leaders gather at Beidaihe was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic – as it was in 2020. By 2019, China’s Party leadership had hosted a total of 19 such groups annually, the People’s Daily reported.

Why is it important to know China’s leaders are vacationing with their families in Beidaihe? The town, with a population of 80,000, not only serves as a place for them to relax, but also provides a backdrop for them to confer informally before their autumn conferences. Any indication of this is not only closely observed by the entire country, but also by hordes of officials from the government, ministries, and military who are also vacation in Beidaihe, but are housed separately from China’s elite in hundreds of distant guesthouses and spa’s, and, despite their close proximity, learn nothing new.

Whenever Beijing’s leaders take their vacation by the sea, it traditionally causes high political waves, the fringes of which are felt not until much later. Mao Zedong was a master at this, spending his summer holidays in Beidaihe a total of eleven times from 1954 onwards. For this purpose, he had his entire party court, government and military follow him from Beijing from July to August to continue their work in Beidaihe. Soon, the seaside resort was called “Xiadu” (夏都) – the summer capital of China. This was until 2003, when then-party leader Hu Jintao had ordered that no more official party meetings and government conferences were to be held in Beidaihe. The summer resort, which had also been open to normal tourists since 1979, nevertheless never became a real holiday destination.

Under Mao, dozens of momentous decisions for China’s development were made in Beidaihe. Western mockers called it a place where not only the country’s top shots but also its socialism repeatedly went under. Revolutionary Mao saw his swimming in the sea as an act of resistance against all currents that did not suit him. In August 1958, he decided in Beidaihe that China’s society was ripe for a Great Leap Forward “into communism”. Tens of millions of people starved to death as a result. At Beidaihe, he made plans for his invasion of Taiwan, which led to the artillery bombardment of Taiwan’s Qinmen Island on August 23, 1958 (the Quemoy Crisis) and almost started a world war. In August 1962, from Beidaihe, he propagated his terrible doctrine of never-ending class struggle, which became the theoretical justification for his murderous Cultural Revolution. Successor Deng Xiaoping set the tone for his reforms at Beidaihe. He demanded that China would “learn to swim in the sea of the market economy” as a metaphor for solving the socialism Mao had run down.

What Xi is currently hammering out with his closest confidants won’t be known for a few years. However, nothing good can be expected. China’s current policies are not only facing international opposition. Xi is heading for his difficult 20th party congress next year, where a generational change in the party leadership is on the agenda. Almost all are expected to retire, save for him, since he already constitutionally secured his continued stay in office. Xi alone will then turn the personnel carousel.

With Beijing not disclosing any details, speculation is running wild: Even the outward atmosphere in Beidaihe is tense as never before, a Japanese reporter told news agency Nikkei. When he arrived in Beidaihe on July 23, a week prior to the expected arrival of the party elite, his car was searched and he was falsely accused of illegally breaking through barriers. After he was allowed to continue, he was constantly tailed by two police cars.

Once upon a time, the mysterious Beidaihe and what Beijing’s leaders were up to there, was considered an indicator of China’s politics. It still is, just less measurable.

In autumn 2021, Roland Busch (56) will take over the chairmanship of the Asien-Pazifik-Ausschuss der Deutschen Wirtschaft (APA) – (Asia-Pacific Committee of German Business). Busch holds the position of Chairman of the Managing Board of Siemens AG. He succeeds Joe Kaeser, Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Siemens Energy AG. Each individual country in the Asia-Pacific economic region also offers great opportunities for the German economy, Busch said. “Raising these potentials is what I want to work for as APA chairman,” Busch said during the announcement of his appointment.

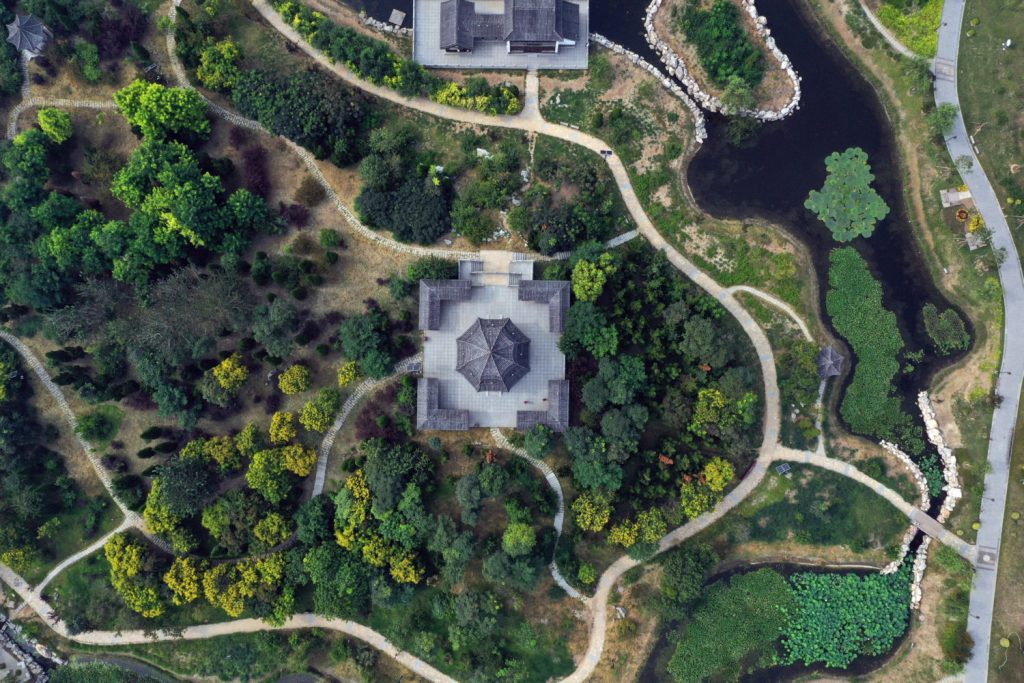

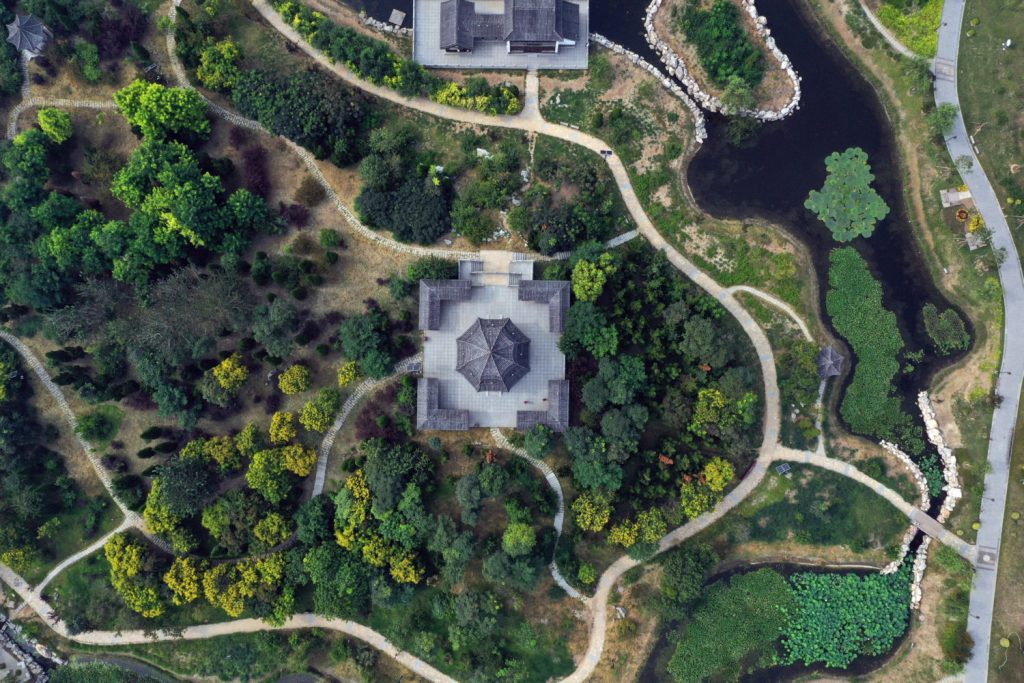

Hejian is to become greener. In the city in the northern Chinese province of Hebei, more than 20 new parks have been laid out in recent years. The green spaces were created as part of an ecological development initiative by the city.

Beijing propagates its image of China through sport, culture and language – but increasingly directly through advertisements in Western newspapers as well. More and more frequently, inserts are appearing in renowned foreign media. The goal: building more credibility and sympathy. Marcel Grzanna has traced the origins of CCP’s advertisements, which also appear throughout German and US media. His discovery: China’s state propaganda is delivered directly to the breakfast table with the newspaper.

Once upon a time, pictures of Mao Zedong taking a swim at the beach surfaced. Xi Jinping will hardly allow himself to be photographed in a similar situation. Our columnist Johnny Erling explains why China’s leadership nevertheless meets at a seaside resort, and why it is sometimes a venue for far-reaching geopolitical consequences. The popular beach of Beidaihe – just two hours by train northeast of Beijing – is also an important site for personnel decisions within the party. A generational shift is in store for the CCP. Except for Xi Jinping himself, who holds his office for life. Hardly any other member of the Chinese political elite will be allowed to travel to Beidaihe forever – at least not to the part of the beach cordoned off and reserved for the political nobility.

Have a restful weekend.

For years, the U.S. branch of China’s news agency Xinhua had successfully evaded its compulsory registration as a foreign outlet in the United States. Despite initial demands in 2018 by the Department of Justice in Washington, it took until early May this year before the state-run medium complied with the legal framework. U.S. authorities, who classify Xinhua as an advocacy group for the Chinese state and thus brand it a propaganda tool, can now finally track in detail how much money flows from the People’s Republic to financially support Xinhua’s activities throughout the US. Between March last year and April 2021, transactions amounted to around 8.6 million US dollars.

China Daily and foreign TV station CGTN, which equally represent and market the Communist Party line around the globe, missed their registration deadline and only filed as foreign missions last year. Through the extensive delay of the bureaucratic procedures, the People’s Republic was able to conceal the financial volume of its propaganda in the United States for a long time.

All Chinese institutions currently registered as foreign missions under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) received around 64 million US dollars from China last year. Almost six and a half times more than in 2016, back when the three media houses were not yet registered. No other country in the world spends this much on its lobbying efforts in the US. Most of it goes to influencing public opinion. According to the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP), an independent non-profit research organization in Washington dedicated to uncovering cash streams within US politics, Xinhua, China Daily and CGTN accounted for 80 percent of the US$64 million expenses. FARA has been in effect since 1938 when it was implemented by the US government to counter Nazi propaganda from Germany.

But what actually happens with the money? Conservative US media report that China Daily is a client of numerous newspapers and magazines, which in the past had placed ads or produced its own inserts in exchange for payments of six- to seven-figure dollar sums. Time Magazine, the Financial Times, Foreign Policy Magazine, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal are mentioned by name.

The publishers concerned are not particularly keen to talk about moneyed political clients from the authoritarian-ruled second-largest economy. After all, there is a risk of reputational damage among readers who consider it inappropriate that a government accused of genocide in Xinjiang and which has broken its contractual promises to preserve democratic civil rights in Hong Kong should be given a platform to write history as it sees fit.

This applies to the USA as well as to Germany. The Handelsblatt Media Group, for example, asks for understanding “that we do not comment on your questions”. This is because the Handelsblatt is one of China Daily’s many propaganda mouthpieces. At irregular intervals, the renowned business newspaper is accompanied by the insert “China Watch”. The multi-page product has the classic appearance of an ordinary newspaper.

Recently, readers of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) were also confronted with Chinese propaganda when the news agency Xinhua placed a full-page advertisement in mid-July to mark the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party. Although the content was marked as an advertisement, its layout did not look like an editorial piece by accident. The publisher of the Süddeutsche Zeitung also accepted similar requests from Chinese media in the past because it did not want to miss out on revenue. German leading media are especially valuable for Chinese propaganda because they offer a reputable guise. This boosts credibility.

The publishers always emphasize that their editorial and advertising departments work independently. “Political advertisements and pieces with strong opinions are always a balancing act for a publishing house, which we decide on after internal review. As it happened in this particular case. Ultimately, however, we gave priority to the free expression of opinion,” FAZ GmbH commented in a statement explaining its course of decision. Of course, FAZ GmbH reviews the advertising subjects and refuses those that obviously violate applicable law. “To prevent critical or provocative advertisements through a kind of preemptive censorship would at least be incompatible with our understanding of a legitimate and free expression of opinion in our democracy.”

Among China critics, this statement is not well received at all. “The justification of the FAZ makes matters even worse. The Xinhua ad praises 100 years of the CCP, but hides the millions of deaths at the hands of the CCP. This is neither ‘provocative’ nor ‘critical’, but simply an inhumane historical lie,” discerns Kai Müller of the International Campaign for Tibet (ICT).

China’s propaganda cleverly exploits those basic principles, whose very same application is severely punished in the People’s Republic. At the same time, the authors benefit from the fact that publishers around the world are under pressure and are in urgent need of advertisers. The Chinese government thus kills two birds with one stone, because in addition to spreading its narratives, it pushes the free media to the brink of a credibility crisis. A desirable goal for the Chinese government, which accuses foreign journalists of lies and distortions on a regular basis. Western media are a powerful and indispensable manifestation of democratic systems, after all. It’s a stroke of luck for Beijing, that a very part of this media creates a platform for a regime that labels democratic values as poison and opposes them bitterly.

The German Journalists’ Association (DJV) is also “not particularly happy” about the placement of such advertisements, but stresses that it is not an editorial decision whether an advertisement is published or not. It is the responsibility of the advertising departments of publishing houses. “We assume that the publishers’ legal advisors are aware of the ad contents prior to publishing and review them for possible contradictions to international law and human rights,” the association stated. For its part, the association does not fear any damage to the reputation of German journalism.

The fact that the quality of said ads or inserts does not meet journalistic standards of leading media hardly impacts the desired effect. Instead, the Chinese government intends to plant its message into the subconscious of the recipients through the permanent repetition of narratives. Without critical assessment, it is then able to solidify itself as legitimate arguments and change points of view. If this happens, the propaganda has already achieved its goal.

However, the US branch of Xinhua clearly downplays its ties to the Chinese Communist Party in its FARA application, even though, like China Daily or CGTN, Xinhua is controlled by the CCP. According to Chinese law, Xinhua is considered a ‘public institution’ subject to state supervision but operates as a separate legal entity. Only a “small portion of its operating funds” is financed by the Chinese government. “Xinhua is increasingly relying on its

own commercial and subscription revenues to sustain its global news operations,” the application states.

However, the millions sent from back home suggest that the revenue is apparently far from sufficient, calling into question the agency’s business model. If it isn’t propaganda, why doesn’t Xinhua decide to pack up under such business conditions?

In Germany, Xinhua also makes generous gestures that run counter to a profitable business. The agency provides its services to local editorial offices, in part, free of charge.

The border dispute between India and China has escalated once again over the recent months. In July, India began to increase its military presence in eastern Ladakh in the Himalayas, a region that overlaps with Kashmir and Tibet, by more than 50,000 soldiers to around 200,000. India is also said to have moved additional combat aircraft and advanced artillery to the region. According to Indian sources, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army has now also moved additional units to the Himalayas.

Indian intelligence and military officials speak of an increase in Chinese troop strength to around 50,000, most of whom are said to have been redeployed from Tibet to the high plains. The number is a significant leap: in June 2020, reports spoke of only around 15,000 troops in the area. At that time, a deadly confrontation between the two nations had taken place there in the Galwan Valley. Twenty Indian and four Chinese soldiers were killed.

Other developments are further fuelling the conflict: Since the beginning of July, a Chinese high-speed train has been operating for the first time, connecting Chengdu via Lhasa to the Arunachal Pradesh region, which both India and China lay claim on. This will reduce the travel distance from Chengdu to Lhasa alone from 48 hours to 13 hours. “If a scenario of a crisis happens at the China-India border, the railway will provide a great convenience for China’s delivery of strategic materials,” said Qian Feng, research director of the National Strategy Institute at Beijing’s Tsinghua University.

For years, China has been expanding its infrastructure along the border to Tibet in the Himalayas, including roads and runways for aircraft. Beijing is said to have invested almost 150 billion US dollars. India has also built over 1500 kilometers of roads between March 2018 and 2020, most of them in the states of Jammu, Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh.

The biggest problem for the balance of power: India increasingly finds itself on the economic defensive against China. Overall, India is lagging behind the People’s Republic in areas of infrastructure, education, health and international competitiveness, while the influence of the Chinese economy in India is growing.

For at least 750 years, the Indian economy stood superior to the Chinese. It was about 1750, 100 years later, when the West took the lead. Then, in the 1980s, China overtook India in economic power. In 1990, India’s gross domestic product (GDP) reached just over US$326 billion, while China’s GDP amounted to 396 billion U.S. dollars. In 2019, the last normal year before the pandemic, nearly 20 million tourists visited India. And more than 60 million came to China.

China has more than 60 million students, whereas India has less than 20 million. India owns nine brands in the top 500 global brands – China can boast 73. The market capitalization of stock exchanges in China is 2.2 times higher than in India. There is also a massive gap in the technologization of its societies: China has four times more televisions than India and as many as ten times more mobile phones. The People’s Republic has 188 cars per 1000 citizens, the US has 838. In India, it is only 20.

In 2020, China’s share of the global gross domestic product was 18.3 percent, adjusted for purchasing power. India, on the other hand, only had 6.7 percent. Could India still catch up to the leader? Hardly. If India were to grow at a whopping eight percent by 2041 and China just four percent, China would be at $5,300 billion – and India would still be more than 20 percent smaller at $4,000 billion.

The military balances also develop in accordance with the slow economic growth. According to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), China spends more than $260 billion annually on its military, while India spends only about $71 billion.

Military exercises by the Chinese navy in the Indian Ocean have also been a cause for concern in India for some time. India owns 150 warships and submarines and one aircraft carrier. In contrast, the People’s Republic of China has more than 350 warships and more than 50 submarines and two aircraft carriers, according to the latest military and security report by the US Department of Defense.

Economically, Beijing is also working ever more closely with India’s neighbors – with both enemies and allies – as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka welcome China’s engagement because it creates a counterweight to India’s neighbor in the region and creates more negotiating leverage to defend their own interests.

Pakistan, India’s hated adversary, particularly benefits from China’s investments – including in the expansion of its army. Most recently, India refused to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free trade agreement, because of China’s regional power ambitions. The member nations Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and the ten ASEAN states Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Brunei, Laos, Cambodia and Singapore only reached an agreement with China after long negotiations.

However, the Indians feared that Chinese products would flood the Indian market as a result of the massively lowered tariffs and local suppliers would be permanently put out of business as a result. India has already reacted with economic sanctions against China after the border dispute of last year. 59 Chinese apps such as WeChat and TikTok have been banned in the country for endangering India’s “national security and sovereignty”, authorities claimed.

In some respects, however, India is ahead of the People’s Republic, at least in terms of numbers: India will replace China as the world’s most populous country in the next decade. And unlike the Chinese, Indians are young. The proportion of the working-age population will remain high. Whether this will be an advantage or even a disadvantage in times of digitalization and automation is not yet clear.

To counter China’s expansion, India has been pushing economic partnerships and developed closer ties to the US in recent years. India, as a global powerhouse and security guarantor in the region, is the US’ most important partner in the Indo-Pacific region, US State Department spokesperson Ned Price said in February. However, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) tells a different story: While India’s FDI in the crisis year 2020 amounted to around 64 billion US dollars, according to UNCTAD, 149 billion US dollars went to China – without even including Hong Kong.

In order to avoid a geopolitical conflagration, Delhi and Beijing agreed in 1996 to ban the use of live ammunition in the border area. The partly unsettled course of the 3,500-kilometer-long Sino-Indian border has been a recurrent source of conflict since the border war of 1962, which China won without gaining any significant territory.

For the two Asian nuclear powers, it is not only a matter of principle but also of strategic control of resources, above all water. Important glaciers are located in the region. An official state border does not exist. Everything that is written dates back to British colonial times. Even in Mao’s time, the People’s Republic no longer recognized these border demarcations as binding.

On June 25, representatives of India and China held another round of diplomatic talks on the border dispute, but so far they have failed to produce any actual results. The effort shows, however, that neither side is interested in a war. The political and economic costs would be too high.

Congestion at China’s two main container ports of Shanghai and Ningbo worsens in the wake of the Covid related closure of a terminal. Around forty container ships were waiting at the outer anchorage off Ningbo Zhoushan Port on Thursday. It was about ten more than at the start of the week, news agency Reuters reported. Work was completely suspended at the Meidong terminal from Wednesday on after a worker tested positive for Covid-19. Restrictions were imposed on workers and ships at other terminals in Ningbo.

The first shipping companies reacted to the closure in Ningbo: French shipping line CMA CGM announced on Thursday that some ships would be diverted to Shanghai or port calls in Ningbo would simply be skipped, according to Reuters. According to a company statement, Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd expected delays to some planned sailings due to the temporary closure of the Meidong terminal.

Ports in Shanghai, which is located close to Ningbo, experienced the highest congestion in at least three years. About 30 ships were waiting for clearance outside the port of Yangshan, a major container terminal in Shanghai.

The important container traffic in and out of China has suffered several blows in recent months: At the end of July, the handling volume at eastern Chinese ports dropped, as they had to temporarily suspend operations due to typhoon In-Fa. At the end of May and June, the Chinese commercial port of Yantian was already closed due to Covid infections. The groundings of the container ship “Ever Given” in the Suez Canal in March also had massively impacted global container traffic.

If the closure of the port in Ningbo continues, world trade could suffer more than it had during the closure of the Port in Yantian. According to the Chinese Ministry of Transport, Ningbo handled 18.7 million containers in the first seven months of the year, more than any other port in the People’s Republic. ari

Since Beijing declared the National Security Law for Hong Kong last summer, 89,200 people have left the former British crown colony. According to government data released Thursday, the exodus has led to a 1.2 percent drop in the total population of about 7.39 million people.

Even before Hong Kong’s security law took effect last June, Hong Kong residents and expats were leaving the city because they saw no secure future. In the second half of 2019, for example, 50,000 people already emigrated from Hong Kong after the occasional brutal street protests.

Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s chief executive, said in late July that people were emigrating for a wide variety of personal reasons and that the city still offered “unlimited opportunities” after the implementation of the National Security Act and with support from mainland China. niw

Chinese authorities have singled out mahjong venues as a high transmission site in the recent Covid wave in the country. As a result, tens of thousands of the mahjong parlors across the country have now been closed, as news agency Bloomberg reported on Thursday. In the province of Jiangsu alone, more than 45,000 mahjong and card games venues have now been affected by the shutdown. Authorities in Beijing and at least four other provinces with elevated Covid numbers – Henan, Zhejiang, Hunan and Heilongjiang – followed suit.

According to the report, a 64-year-old woman in Yangzhou had spread the delta variant of the virus at a mahjong parlor. The woman had previously visited a relative in Nanjing, which was known to harbor a Covid cluster. She had then been to several mahjong venues in Yangzhou before testing positive for Covid-19, the report added. Mahjong is especially popular among the older demographic in China.

The virus cluster in Yangzhou had therefore also predominantly affected older people. Around 70 percent of those infected were older than 60, Bloomberg reported. According to the report, about two-thirds of the registered infections were attributable to the mahjong venues. In addition, the vaccination rate among the elderly in Yangzhou is only around 40 percent. Of the 448 people infected with Covid in the area, 23 had shown severe symptoms. Twelve infected are currently in critical condition. ari

Recent changes to procurement guidelines in China will hit medical equipment manufacturers such as Siemens, GE Healthcare and Philips the hardest, according to new details. Beijing had instructed local authorities to rely on more locally produced goods when procuring MRI and X-ray equipment, as well as surgical endoscopes and PCR testing equipment. Of the 315 product categories affected, 200 alone are located in the medical sector, according to details of the public procurement regulation recently published by Nikkei Asia.

Large foreign manufacturers such as Siemens, GE and Philips are at risk of losing sales as a result, the report continued. The regulation is also said to be aimed at forcing high-tech companies in the healthcare sector to relocate their production to China. A representative of an unnamed foreign trade association had told Nikkei that manufacturers fear that if they move production now, “technologies could fall into the hands of Chinese competitors.”

These new rules are based on regulations issued by China’s Ministry of Finance and Industry in May (as reported by China.Table). The new rules stipulate that domestically produced goods must account for 25 to 100 percent of public contracts, depending on the product category. According to the newspaper, it remains unclear whether the new regulation will also affect purchases by state-owned enterprises, hospitals and local authorities. nib

Chinese premium electric car manufacturer Nio plans to establish its own brand to compete on the mass market. This will put the company in direct competition with manufacturers such as Volkswagen and Toyota. “The relationship between Nio and our new mass brand will be similar to that between Audi and Volkswagen, or Lexus and Toyota,” company CEO William Li announced. Up until now, Nio, as a premium manufacturer of SUV vehicles ranging in the price range of equivalent to around 40,000 euros, mainly built cars for the same target group as Audi, BMW or Tesla.

On Thursday, Li said that Nio is preparing to launch two new models next year. In addition to the previously announced ET7 sedan, a more affordable model than Nio’s current ones is to be released. The new models, however, are not expected to compete in the lower end of the market, which is dominated by the Hongguang Mini of SAIC-GM-Wuling Automobile Co., whose vehicles cost the equivalent of 3,850 euros. niw

China’s top-level authorities have adopted a “five-year blueprint” to strengthen regulatory control over key economic sectors. The Communist Party Central Committee and the State Council released a policy document on the regulation of multiple fields, including digital economy, IT companies operating in the financial sector, artificial intelligence, Big Data, cloud computing, and food and drugs, as the Financial Times and Bloomberg reported.

The authorities’ goal is to ensure that “new business models develop in a healthy manner.” Beijing sees an “urgent need” for additional laws to regulate the education sector and resolving antitrust issues, as well as in the area of national security.

“We can’t draw too much insight about enforcement and the potential shape of crackdowns from one document or another,” Graham Webster, who leads the DigiChina project at the Stanford University Cyber Policy Center, told Bloomberg. A representative of consulting firm AgencyChina told the news agency that he believes the announcement gives investors a bitter insight into “future regulatory hotspots.” Uncertainty is deterring investors, he added.

This was further confirmed by Global fund managers to Reuters. “I think investors just don’t like the uncertainty of not knowing what’s the next shoe to drop,” said Mark Haefele, chief investment officer at UBS Global Wealth Management. Other fund managers see the crackdown of recent weeks and months as a “transitionary phase” rather than a change in policy, according to Reuters. Overall, foreign investors hold $800 billion worth of Chinese stocks and bonds. A year ago, this figure was 40 percent lower, according to the Financial Times. nib

Party chief Wang Dongfeng (王东峰) is the most powerful man in Beijing’s neighboring province of Hebei. He personally inspected all police checkpoints on July 30 on the roads leading to the sea at Beidaihe. China’s famous seaside resort, a 280-kilometer highway drive from Beijing, falls under the jurisdiction of his province. Wang expressed satisfaction with the checkpoints, which are equipped with cutting-edge high-tech. He considered them “key defense points to guarantee China’s social harmony and stability,” adding that combined air and ground defense and the use of science and technology such as “facial surveillance and artificial intelligence” can ward off threats. Wang was probably thinking particularly of protecting China’s State and Party leader Xi Jinping. Because Xi’s name is mentioned a total of seven times in the report on provincial leader Wang by Hebei Daily, published on August 2nd.

For those who didn’t know, Xi and his inner circle were on their way to Beidaihe for their annual summer break. This is where Beijing’s elite retreat every year to their villas hidden among pine and cedar forests on the Lotus Mountain above a western beach closed off to them. The political elite is the real target of the submissive report in the Hebei daily. China’s top leaders are so paranoid when it comes to their security and secrecy that they don’t even disclose if, how long and where they are vacationing. They just disappear off the face of the earth. Only the Foreign Ministry provides a little insight: on July 30, it made the following announcement on its website: “We are taking a summer break (暑期) from August 2 to 13.” This is the period when China’s leaders take a vacation.

But for those who read between the lines, the report on the party chief’s inspection is the first of two indirect clues Beijing’s party elite uses every year to publicly announce its departure to Beidaihe. This was revealed on August 10 by the well-connected news website Duowei Xinwen. So far, the second hint has always come shortly after their arrival at the seaside resort. Since 2000, China’s party leadership has granted a group of selected Chinese scientists a one-week special vacation in Beidaihe each year. China’s party chief personally sends two trusted subordinates of his politoffice to greet them on his behalf. This year, the well-established announcement procedures that the leaders gather at Beidaihe was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic – as it was in 2020. By 2019, China’s Party leadership had hosted a total of 19 such groups annually, the People’s Daily reported.

Why is it important to know China’s leaders are vacationing with their families in Beidaihe? The town, with a population of 80,000, not only serves as a place for them to relax, but also provides a backdrop for them to confer informally before their autumn conferences. Any indication of this is not only closely observed by the entire country, but also by hordes of officials from the government, ministries, and military who are also vacation in Beidaihe, but are housed separately from China’s elite in hundreds of distant guesthouses and spa’s, and, despite their close proximity, learn nothing new.

Whenever Beijing’s leaders take their vacation by the sea, it traditionally causes high political waves, the fringes of which are felt not until much later. Mao Zedong was a master at this, spending his summer holidays in Beidaihe a total of eleven times from 1954 onwards. For this purpose, he had his entire party court, government and military follow him from Beijing from July to August to continue their work in Beidaihe. Soon, the seaside resort was called “Xiadu” (夏都) – the summer capital of China. This was until 2003, when then-party leader Hu Jintao had ordered that no more official party meetings and government conferences were to be held in Beidaihe. The summer resort, which had also been open to normal tourists since 1979, nevertheless never became a real holiday destination.

Under Mao, dozens of momentous decisions for China’s development were made in Beidaihe. Western mockers called it a place where not only the country’s top shots but also its socialism repeatedly went under. Revolutionary Mao saw his swimming in the sea as an act of resistance against all currents that did not suit him. In August 1958, he decided in Beidaihe that China’s society was ripe for a Great Leap Forward “into communism”. Tens of millions of people starved to death as a result. At Beidaihe, he made plans for his invasion of Taiwan, which led to the artillery bombardment of Taiwan’s Qinmen Island on August 23, 1958 (the Quemoy Crisis) and almost started a world war. In August 1962, from Beidaihe, he propagated his terrible doctrine of never-ending class struggle, which became the theoretical justification for his murderous Cultural Revolution. Successor Deng Xiaoping set the tone for his reforms at Beidaihe. He demanded that China would “learn to swim in the sea of the market economy” as a metaphor for solving the socialism Mao had run down.

What Xi is currently hammering out with his closest confidants won’t be known for a few years. However, nothing good can be expected. China’s current policies are not only facing international opposition. Xi is heading for his difficult 20th party congress next year, where a generational change in the party leadership is on the agenda. Almost all are expected to retire, save for him, since he already constitutionally secured his continued stay in office. Xi alone will then turn the personnel carousel.

With Beijing not disclosing any details, speculation is running wild: Even the outward atmosphere in Beidaihe is tense as never before, a Japanese reporter told news agency Nikkei. When he arrived in Beidaihe on July 23, a week prior to the expected arrival of the party elite, his car was searched and he was falsely accused of illegally breaking through barriers. After he was allowed to continue, he was constantly tailed by two police cars.

Once upon a time, the mysterious Beidaihe and what Beijing’s leaders were up to there, was considered an indicator of China’s politics. It still is, just less measurable.

In autumn 2021, Roland Busch (56) will take over the chairmanship of the Asien-Pazifik-Ausschuss der Deutschen Wirtschaft (APA) – (Asia-Pacific Committee of German Business). Busch holds the position of Chairman of the Managing Board of Siemens AG. He succeeds Joe Kaeser, Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Siemens Energy AG. Each individual country in the Asia-Pacific economic region also offers great opportunities for the German economy, Busch said. “Raising these potentials is what I want to work for as APA chairman,” Busch said during the announcement of his appointment.

Hejian is to become greener. In the city in the northern Chinese province of Hebei, more than 20 new parks have been laid out in recent years. The green spaces were created as part of an ecological development initiative by the city.