The Covid pandemic has also triggered mental problems, uncertainty, and crises of meaning in many Chinese. In addition, many suffer from stress and long working hours. This lead to a real run on meditation, rest, and mindfulness. And China wouldn’t be China if there weren’t a multitude of new mindfulness apps that are already competing fiercely with each other. Fabian Peltsch took a closer look at the Chinese meditation hype.

Away from jammed streets of the big city is also the name of the game for developers of electric air taxis: Several start-ups in the East and West are working on the dream of escaping the traffic chaos on the ground into the air. One of the most promising companies for flying cars is HT Aero, a subsidiary of EV company Xiaopeng Motors. Frank Sieren reports about the latest developments in this high-tech segment and HT Aero’s flying car, which also looks good on the road, and not just because of its four wheels.

Research and development are high on the agenda in innovation-crazy China. For many years, the government has been promoting this development through subsidies. However, they did not always have the desired effect. In today’s Opinion piece, Bettina Peters and Philipp Boeing from the Leibniz Center for European Economic Research explain the problems, developments, and reforms of Chinese innovation funding.

“Why is the West taking our traditional Chinese culture and is selling it back to us?” ranted Zeng Xianglong, a psychology professor at Beijing Normal University, in an interview mid-year. His angry comment was directed at mindfulness, a meditation practice focused on the present moment. This practice is also experiencing a boom in China. In wealthy metropolises such as Shanghai and Shenzhen, mindfulness studios have sprouted up in the past three years. Hundreds of mindfulness apps entice people with guided meditations, videos, or music tracks that are supposed to relax, alleviate anxiety or help you fall asleep. Even large Chinese corporations like Huawei and Didi Chuxing now offer their employees breathing exercises to reduce stress. The underlying idea behind this trend, which has been adopted from Silicon Valley, is that people who feel inner peace work more efficiently.

But Professor Zeng is right: The current trend is indeed coming from the West. But China is the birthplace of mindfulness. Mindfulness meditation has been practiced for centuries in Chinese Chan Buddhism. The communists initially saw individualistic introspection primarily as a superstition. During the Cultural Revolution, practitioners were openly attacked and Buddhist temples were destroyed.

Western-modern mindfulness meditation, largely stripped of its religious context, now traces its origins in part to the American scientist Jon Kabat Zinn. When the professor for molecular biology first traveled to China in 2011, he praised the positive reactions of the largely secular Chinese, saying: “It felt like the closing of a certain kind of karmic circle.”

Young Chinese regard traditional mindfulness exercises such as Tai Qi, Qi Gong, or calligraphy as a pastime for pensioners. To escape their stressful daily lives, younger people instead prefer to turn to a mindfulness app – even if it’s just in the form of a ten-minute headphone meditation on the subway. “If anything, the lack of a religious component adds to the popularity of mindfulness in China,” says Dalida Turkovic, who runs the Beijing Mindfulness Center near Beijing’s Lama Temple. The mindfulness instructor, who was originally a trained business coach, came to China in 1993. After her home country Yugoslavia fell apart, she suffered from depression for years. Through traditional Chinese martial arts, she eventually stumbled upon mindfulness meditation, which she says helped her out of the worst of her crisis. “Unlike traditional teachings like Qi Gong, the Western way of mindfulness strengthens psychological self-awareness,” the 52-year-old explains.

For many Chinese, mindfulness is nowadays above all a lifestyle. The market for Chinese mindfulness apps is thus highly competitive. Top dogs like Headspace or Calm in the West have not yet found their way to China. Platforms available in Chinese, such as Tide (潮汐) or Now Meditation (Now冥想), which was founded in 2016, offer content similar to their Western counterparts. However, they also offer workshops and in-depth courses at the in-house Mindfulness Academy for an additional fee.

In response to the Covid-19 outbreak, almost all start-ups introduced special relaxation exercises designed to alleviate the worst existential fears. “In these uncertain times, many Chinese have experienced crises of meaning,” says Dalida Turkovic of the Beijing Mindfulness Center. The lockdowns have also contributed to the uncertainty. “Many don’t believe that anything will change between now and the Olympics. A good opportunity to take a good look at oneself.”

The Covid pandemic has also thrown a spotlight on mental health in China. The World Health Organization estimates that around 54 million people in the People’s Republic suffer from depression, 41 million from anxiety, and 300 million from insomnia. Of course, economic pressures also play a role. Working six days a week from 9 AM to 9 PM has become the norm for many Chinese, especially in the tech industry (China.Table reported). This does not leave much time for dealing with problems and the search for meaning. The fact that Hou Xi, one of the co-founders of the Chengdu-based meditation app Ease, used to work as a banker for Goldman Sachs speaks volumes.

In Chinese society, mental health problems are still widely stigmatized. According to the World Mental Health Survey, a global survey conducted by the World Health Organization, 87 percent of concerned Chinese do not consult a doctor when they are struggling with mental health issues. The global average is 48 percent. Adjustment disorders or mild to moderate depression are usually not even classified as illnesses in China and accordingly remain untreated. In her book “Mental Health in China” (Polity Press, Cambridge, 2018), anthropologist Jie Yang argues that the taboos surrounding mental illness can be traced back to the collectivist Confucian heritage, but also to the Mao era when psychology was demonized as a “bourgeois pseudoscience”.

Online platforms such as Know Yourself (知我探索), Jiandan Xinli (简单心理) or Yi Xinli (壹心理) aim to close this gap in the Chinese healthcare system with a mixture of wellness, psychotherapy and spiritual search for meaning. Articles published on “Know Yourself” on topics such as “building self-confidence,” “self-care,” or “career pressure” are read several hundred thousand times on average. In addition, the Shanghai start-up recommends certified video therapists to its users. On WeChat alone, Know Yourself has around 2.8 million followers.

The Chinese call the trend towards psychological self-help Xinling Jitang (心灵鸡汤): “Chicken soup for the soul”, based on the eponymous US self-help guide, which also happens to be extremely popular in China. In China’s book market, self-help titles now account for an estimated one-third.

Beijing welcomes citizens’ initiative, as China still lacks mental health professionals. The World Health Organization (WHO) calculated in the last survey in 2017 that there are fewer than nine psychiatrists for every 100,000 Chinese. In its “Healthy China 2030” initiative, the Chinese government therefore explicitly recommended meditation as a method of dealing with lockdown stress.

Of course, there is also an economic factor to it: China wants to generate more and more of its economic growth in the service sector. Wellness offers are playing an increasingly important role in this. The turnover in the Chinese yoga market alone was estimated at ¥46.8 billion last year (€6.5 billion). The Shanghai-based mindfulness center “Creative Shelter” is even developing soundproof meditation chambers that, like the ubiquitous massage chairs in China, should one day be in every shopping mall. “Spiritual care can also bring economic benefits,” explains state broadcaster CCTV2.

The CCP, however, is likely to keep a close eye on the development of wellness and the mental health movement. In China’s history, spiritually tinged physical training has often led to open rebellion, for example, when the so-called Boxers rebelled against foreigners at the end of the Qing Dynasty or when the Red Turbans overthrew Mongol rule in the 14th century. The most recent case of a mass spiritual movement occurred in the 1990s. At that time, the meditating disciples of the Falun Gong wanted to tend to the spiritual needs of the many Chinese who were looking for support during the rapid social changes.

Initially, Falun Gong was supported by the government. However, when membership exceeded 70 million – more than the Communist Party had at the time – the movement was banned by the head of state Jiang Zemin as a “spiritual opiate” and a “danger to social stability”. Its members were subsequently rigorously persecuted. What “inner peace” is, and how to maintain it, is determined by the party alone. Fabian Peltsch

Visually, the electric flying vehicle, whose design was recently unveiled by Xpeng subsidiary HT Aero, looks like something out of a James Bond movie: In addition to its four wheels, the sleek, lightweight two-seater has two elongated rotor arms with a wingspan of a good 12 meters. When they are folded, the vehicle is a roadworthy sports car. Once they are unfolded, however, it becomes a passenger drone with vertical take-off ability. In addition to two airbags, it is also equipped with parachutes as a safety feature.

The vehicle, which doesn’t yet have a name, will have a steering wheel for road travel and a single lever for flight mode, Techcrunch magazine reports. According to the company, it will also have an advanced perception system that can fully assess the environment and weather conditions before takeoff.

The start of production is targeted for 2024. The design of the mini-aircraft is not yet final and could still be subject to change until it is fully ready for the market, the company explains. The price could probably be the equivalent of around €140,000.

Guangzhou-based startup HT Aero recently raised around $500 million in venture capital. The company speaks of the largest venture funding round to date for a startup in Asia’s passenger aviation sector. The large number of high-profile backers shows that investors have faith in this new market segment. The cash injection for HT Aero will mainly go towards research and development and recruiting new top talent, explains Zhao Deli, founder and president of the company.

This year alone, some $4.3 billion has been invested in flight car startups through August, according to Financial Times. US consultancy Morgan Stanley predicts that the market for flying cars will be worth $1.5 trillion in as little as 20 years. The consultancy Roland Berger expects around 160,000 commercial shuttle drones to be flying through the skies worldwide in 2050.

Through their road capability, flying cars differ from what has been developed so far under the name of air taxis. Some manufacturers are already testing taxis or flying drones. But these are not flying road cars with wheels so far. Instead, they take off vertically from fixed places. Whether HT Aero’s flying car, scheduled for 2024, will also be able to switch from driving to flying mode is still uncertain.

Xiaopeng and HT Aero have already unveiled several predecessor models that are also electric, including the manned Voyager X1 and X2. Both are still in development and have already successfully completed more than 10,000 test flights, according to a report in the trade magazine Elektrek. Road testing is expected to start in China later this year. According to the company, the X2 can handle a maximum take-off weight of 760 kg including two passengers, with a maximum flight duration of 35 minutes. The projected flight altitude is below 1000 meters.

Due to their limited range, for the time being, air taxis like these will initially find a primary use on short urban routes at low altitudes, such as shuttle services to the airport. But that’s exactly the type of use that is needed in China’s congested cities.

But the competition never sleeps. Numerous air taxi competitors include US start-up Joby Aviation, which is supported by Toyota, among others, and the German start-up Lilium from Weßling in Bavaria. Lilium counts Chinese tech giant Tencent among its investors.

In Europe, the Dutch company Pal-V is way out in front when it comes to flying cars with road capability. It plans to begin series production of its flying car Liberty this year – according to its own information, the first company in the world to do so. The aircraft has already been certified by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). A certification that is also accepted in China and the USA. The Liberty, a two-seater based on gyrocopter technology, can fly for four hours or 500 kilometers, but at the same time travel at 160 Km/h on the road with three wheels. With its rotors folded, it is no bigger than a normal car.

VW has also announced plans to launch a feasibility study in China on flying cars. The Wolfsburg-based company also wants to push ahead with its own investments and the hunt for a potential cooperation partner as soon as possible. In March, Chinese automaker Geely announced plans to bring a flying car to the Chinese market by 2024 as well. Onboard with the Chinese is the German startup Volocopter, which is headquartered in the Baden-Wurttemberg town of Bruchsal.

However, HT Aero’s biggest competitor in China is currently the company EHang, which also comes from Guangzhou. The startup, which has been listed on the stock exchange since 2019, has developed the EHang 184 passenger drone and the EHang 216 two-seater, two of the most sophisticated electric air taxi models to date. However, even EHang has yet to produce road-ready flying cars. The company claims to have sold 70 units of its “autonomous flying objects” last year. However, it may well be that EHang will also move quickly into flying car development: The focus of its know-how is on flying, not driving.

Xiaopeng Motors and HT Aero are planning mass production for the unnamed flying car as early as 2024. However, this seems very ambitious considering the regulatory hurdles and the lack of a uniform set of rules nationwide. Only a few provinces, such as Anhui and Jiangxi, have so far introduced pilot zones where air taxis are allowed to be tested throughout. In addition to technical issues, there is also the question of where air cars and air taxis are allowed to take off and land.

Unlike most developers, who mainly sell their air vehicles to companies, HT Aero wants to sell mainly to private customers. Company boss Zhao explains that HT Aero’s air taxis will also be used for aerial tours, police missions, or emergency rescues. Numerous bases on the ground will provide monitoring and remote control in case of an emergency. But the X2 first needs regulatory approval. Only then can the aircraft take to the skies.

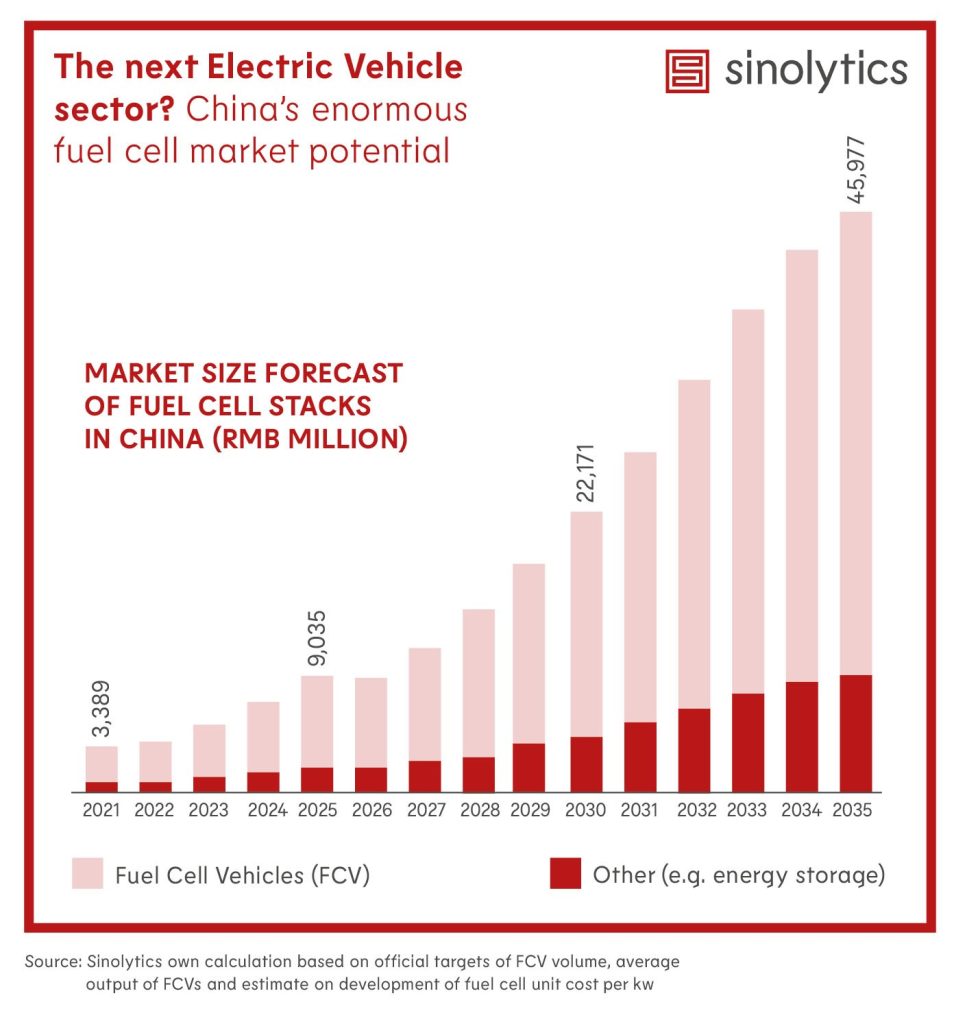

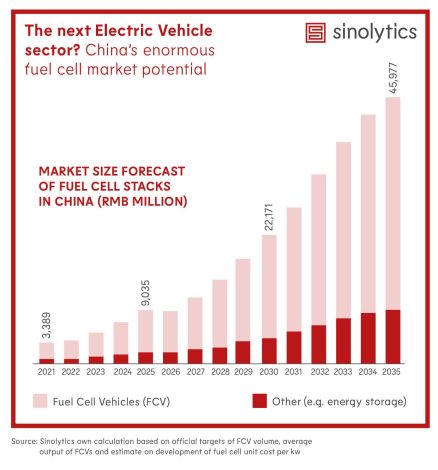

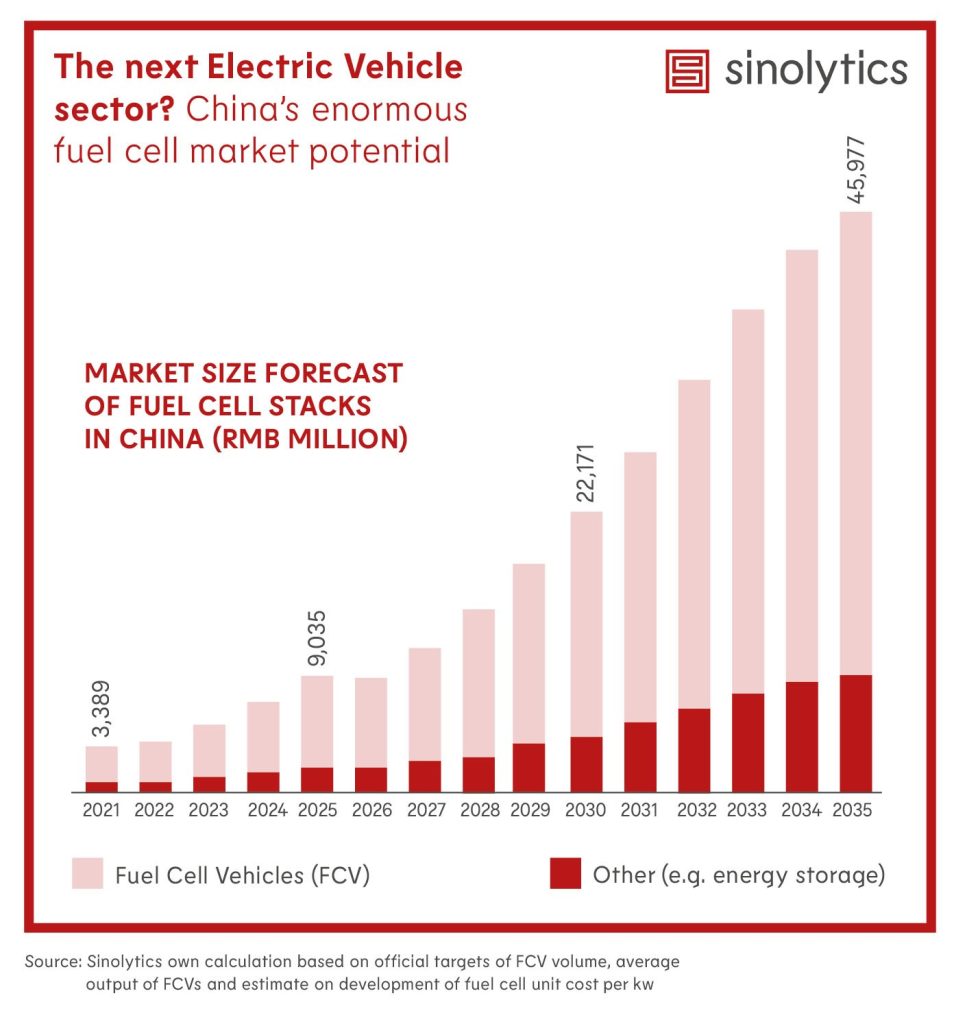

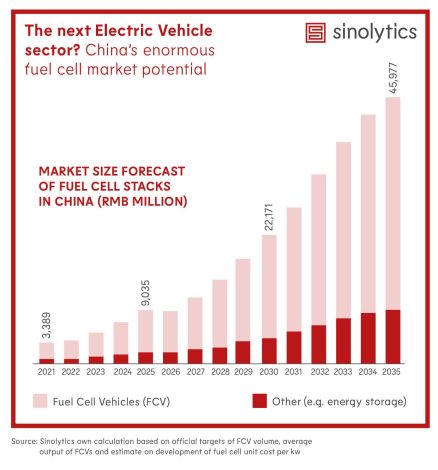

Sinolytics is a European consulting and analysis company that focuses entirely on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in China.

Greenland has withdrawn the license for an iron ore deposit near the capital Nuuk from a Chinese mining company. The reason was years of inactivity at the Isua site, the government announced on Monday. The Hong Kong-based company, called General Nice, also failed to make the agreed guarantee payments, it said. “We cannot accept that a license-holder repeatedly fails to meet agreed deadlines,” Greenland’s Resources Minister Naaja Nathanielsen said. The government announced it would offer the license to other interested companies after General Nice officially returned it, according to a Reuters report.

The deposit has been in the sights of Chinese interested parties for years, but in the end, they never became active. In 2013, British company London Mining was granted the mining license. The company wanted to hire around 2,000 Chinese workers to build the project and supply China with around 15 million tons of iron ore per year. But it failed to secure funding, and London Mining went bust. General Nice, a Chinese importer of coal and iron ore, took over in 2015.

Resource-rich Greenland and the Danish government have viewed Chinese investment with skepticism for years. When General Nice wanted to buy an abandoned naval station in Greenland from Denmark in 2016, Copenhagen vetoed the deal over security concerns, sources told Reuters at the time. In 2018, Greenland also rejected a bid by a Chinese state-owned bank and a state-owned construction company to finance and build two airports in Greenland. That year, the new government in Nuuk banned uranium mining on environmental grounds, effectively halting the development of the Kuannersuit mine. It is considered one of the world’s largest deposits of rare earth deposits. Chinese company Shenghe Resources had previously secured mining rights there. ck

Singapore’s former ambassador to the United Nations, Kishore Mahbubani, has warned of the chance of a nuclear war between the US and China. The Taiwan conflict could escalate if Washington does not adhere to its one-China policy, Mahbubani said at an event marking the 25th anniversary of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation’s Media Programme Asia in Singapore. China is “a rational actor in all fields, with one exception: on Taiwan, China is an emotional actor,” he said. Should Washington or Taipei, on the other hand, try to push through Taiwan’s independence, contrary to US President Joe Biden’s assurances, a “red line” would be crossed for Beijing, warns the high-profile, but in part also controversial political observer.

At the event, Mahbubani discussed the issue with former German magazine Spiegel chief Stefan Aust, who has just published a book on Xi Jinping. According to Aust, it is China that wants to change the status quo. Mahbubani disagreed, saying, “The Chinese will not go out and occupy Taiwan on their own.” Without external provocations, China would postpone such ambitions for a few more years until it was “the world’s largest economic power.” For the time after that, Mahbubani then suggested a willingness on Taipei’s part to rejoin the mainland after all.

The situation around Taiwan seems tense at the moment: From the Chinese side, the small and large provocations are piling up (China.Table reported), while Biden has used the word “independence” in connection with the island. His aides have interpreted the remark as an oversight. His staff has interpreted the remark as a misunderstanding. But Beijing could take the change in language as an indication of policy change. fin

Russian President Vladimir Putin has pledged his presence at the kick-off of the Winter Olympics in Beijing. “Xi invited his good friend Putin to attend the opening ceremony of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing,” a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman said Tuesday. This, he said, shows once again how deep the partnership between China and Russia is. “China and Russia have a fine tradition of celebrating major events together.”

Beijing is emphasizing the visit from Moscow in such a conspicuous manner because US President Joe Biden has already considered a diplomatic boycott of the Olympics due to human rights violations in China. The UK would potentially join such a boycott. This means that no official government delegation from either country would travel to Beijing. Putin, on the other hand, stressed that Sino-Russian relations are “stronger than ever”, according to state media reports. The Winter Games will be held in February 2022. fin

China is at risk of missing its own solar energy expansion target this year. Due to rising prices in solar supply chains, photovoltaic cells became more expensive in 2021 for the first time in eight years, Bloomberg reports. As a result, China has so far added only 29.3 gigawatts of solar capacity between January and October, the news agency reports, citing China’s National Energy Commission. This is far below the China Photovoltaic Industry Association’s annual projection of 55 to 65 gigawatts of new photovoltaic capacity.

China’s renewable energy developers often install large parts of their capacity at the end of the year to meet subsidy deadlines as well as their own targets, according to Bloomberg. This year, however, such a surge became less likely over the recent months: The government no longer offers subsidies for most large-scale solar installations, and the quota for rooftop solar subsidies had already been almost reached by the end of October. The world’s largest solar module manufacturer, Longi Green Energy Technology, expects only 40 to 45 gigawatts of new capacity in 2021, Bloomberg writes, citing analysts at Morgan Stanley.

For years, China has been installing more photovoltaic systems than any other country. State and party leader Xi Jinping had recently surprised with the announcement that he wanted to build 100 gigawatts of capacity for wind power and solar energy in China’s deserts. Parts of the projects are already under construction (China.Table reported). But the pace of expansion could now slow down. ck

Wuling, the joint venture between General Motors and Chinese carmaker SAIC, unveiled the “Nano” version of the Wuling Hongguang Mini EV on Monday. With a length of 2.50 meters and a wheelbase of 1.60 meters, the Nano EV is even smaller than the standard model. The car’s length is 42 centimeters shorter, while the wheelbase is 34 centimeters. The sleek two-seater comes with a 24-kilowatt electric motor. It is said to travel 305 kilometers on one battery charge. The company, which is based in Liuzhou in the southwest of China, has not yet given any information about the battery capacity.

The Wuling Hongguang Mini EV remains one of the best-selling EVs in China (China.Table reported). Between January and September, it accounted for more than a fifth of new registrations. The vehicle fills a gap in the People’s Republic. Many Chinese who previously only drove trikes and e-scooters now have enough purchasing power to afford a low-cost microcar as an entry-level vehicle. The driver airbags and parking sensors available in the Nano are downright luxuries for this clientele. Depending on features, the Nano costs between €6,300 and €8,300. Despite its smaller dimensions, this makes it more expensive than the standard model. The full-size Wuling Mini EV is available in China for as little as €4,000. fpe

Population growth in China has slowed. According to the latest Statistical Yearbook by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, there were 8.5 births per 1,000 people last year. This data shows that China’s birth rate in 2020 has dropped by the most since 1978. The Health Commission had already stated in July that the number of newborns in China could soon decline again. Official agencies did not want to comment on the reasons for the developments.

At the same time, census data was revised upward: A higher birth rate than previously estimated was recorded for the years from 2011 to 2017. He Yafu, an independent demographer, told Bloomberg that the change “likely reflects undercounting of births in previous years.” Experts had expressed surprise at the level of decline in China’s birth rate after the official population data was released earlier this year (China.Table reported). But many couples, especially in China’s big cities, no longer want a second child because of the high cost of living and education, although Beijing has been allowing families to have three children a few months back for fear of over aging.

Meanwhile, statistics released by the Ministry of Civil Affairs show that 5.88 million marriages were registered in the first three quarters of this year. According to state-run Global Times, this is a 17.5 percent drop from last year. But not only did the number of marriages fall during the pandemic, but the number of divorces also dropped. In the first half of this year, only 966,000 marriages were divorced – 50 percent less than in the same period last year. niw

Over the past two decades, business expenditure on research and development (BERD) has been the main driver of R&D growth in China. The annual BERD growth rate was consistently higher than the average growth rate of OECD countries. At the same time, government support for R&D spending in China officially reached only 4.3 percent between 2003 and 2018, well below the OECD average of 6.7 percent. To become more innovative, China’s R&D spending is expected to increase by at least 7 percent annually over the next five years, supported by government R&D subsidies. However, this is not enough: As a recent study by the ZEW (Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research) in Mannheim shows, R&D subsidy misuse has been widespread in China in the past and has long stood in the way of efficient use of state subsidies.

For this reason, a reorientation of China’s innovation and industrial policy was already accompanied by numerous measures in 2006, both to improve funding instruments and to curb their misuse. If such measures take even better effect in the future, China will become an increasingly innovative competitor on the global market and at the same time gain in popularity as an R&D location for foreign companies.

The share of subsidy beneficiaries among listed companies in China has increased enormously since the turn of the millennium: While it was 32 percent in 2001, it was already 90 percent in 2011. On average, about 10 percent of total government subsidies to enterprises were specifically earmarked for R&D activities. However, our study shows that about 42 percent of R&D subsidy beneficiaries spent all or at least part of these government funds on non-research purposes between 2001 and 2011. This form of subsidy abuse was measured by comparing the R&D expenditures published in each firm’s annual reports and R&D subsidies received. Overall, 53 percent of all subsidy payments earmarked for R&D went to other, i.e. non-research, purposes. For example, subsidies are often misappropriated to cross-subsidize non-R&D-related investments, which can also lead to rapid reductions in production costs and distort competition on international markets.

The study results indicate that R&D spending did increase as a result of subsidies, but the increase among subsidized companies could have been more than twice as high as it actually was. The government R&D subsidy also led to the increase in investment in fixed assets, employment, and sales among companies. Furthermore, the analysis also reveals optimization potential in the selection of eligible companies. So far, R&D subsidies had no effect on state-owned companies, and support for the high-tech sector should also be more differentiated in the future. According to study results, in addition to misuse of subsidies, payments occurring too frequently or at too high a rate could also lead to inefficiencies.

Further, we find that misuse is declining significantly over time, from 81 percent in 2001 to 18 percent in 2011. The Chinese government also achieved this decline through its “Medium- to Long-Term Plan for the Development of Science and Technology”. Through it, China has already been able to address some structural problems in its innovation system and implement necessary improvements. In addition, the administration of subsidy programs has been restructured in such a way that companies can now be selected more precisely and the use of subsidies can be better controlled. These reforms were already having a significant impact. However, in 2020 there was still extensive misuse of state support in semiconductor manufacturing, a key industry for the technological sovereignty China is striving for.

China has not yet proven that it is more capable of generating innovation and cutting-edge technology than the world’s leading innovation systems in the United States. However, if China succeeds in further improving the design and implementation of its innovation policy with the 14th Five-Year Plan, it can be expected that future business productivity will also increase, resulting in higher economic growth due to “Innovation Made in China”. Politics and business in the US and Europe should already be gearing up for a further intensification of competition, especially in high-tech sectors.

Bettina Peters is Deputy Head at ZEW’s “Economics of Innovation and Industrial Dynamics” Research Department, Honorary Professor in Innovation at the Faculty of Law, Economics, and Finance at the University of Luxembourg. Philipp Böing is Senior Researcher at ZEW

This article is part of the Global China Conversations event series of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). On Thursday, Philipp Böing, Senior Researcher at ZEW in Mannheim, and Wolfgang Krieger, Deputy Managing Director of the Federation of German Industries (BDI) in China, will discuss the topic: “Innovation Made in China” – How effective is Beijing’s innovation policy? China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

HSBC Asset Management has appointed Daisy Ho as its new Regional Chief Executive for the Asia Pacific and Hong Kong. Ho is based in Hong Kong and reports to Chief Executive Nicolas Moreau. Ho has more than 20 years of experience in the asset management industry at JP Morgan, AXA, and Hang Seng Bank, among others, and joins from Fidelity International, where she was most recently President for China.

June Wong has been elected Group President of Hong Kong-based asset management firm Value Partners. Wong has three decades of experience in the industry and is a member of the Advisory Committee of Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission regulator.

Ping-Pong Diplomacy in action: Two US-Chinese mixed teams train for the World Table Tennis Doubles Championships in Houston, Texas. The US and China are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the so-called Ping-Pong Diplomacy, which once ushered in a thaw between the two countries, thanks to historic teamwork. Pictured in front are US’s Lily Zhang and China’s Lin Gaoyuan. Playing in the background are China’s Wang Manyu and US’s Kanak Jha. The World Championships kicked off on Tuesday. The Wang/Jha duo could face German European champions Dang Qiu and Nina Mittelham in the second round of the competition.

The Covid pandemic has also triggered mental problems, uncertainty, and crises of meaning in many Chinese. In addition, many suffer from stress and long working hours. This lead to a real run on meditation, rest, and mindfulness. And China wouldn’t be China if there weren’t a multitude of new mindfulness apps that are already competing fiercely with each other. Fabian Peltsch took a closer look at the Chinese meditation hype.

Away from jammed streets of the big city is also the name of the game for developers of electric air taxis: Several start-ups in the East and West are working on the dream of escaping the traffic chaos on the ground into the air. One of the most promising companies for flying cars is HT Aero, a subsidiary of EV company Xiaopeng Motors. Frank Sieren reports about the latest developments in this high-tech segment and HT Aero’s flying car, which also looks good on the road, and not just because of its four wheels.

Research and development are high on the agenda in innovation-crazy China. For many years, the government has been promoting this development through subsidies. However, they did not always have the desired effect. In today’s Opinion piece, Bettina Peters and Philipp Boeing from the Leibniz Center for European Economic Research explain the problems, developments, and reforms of Chinese innovation funding.

“Why is the West taking our traditional Chinese culture and is selling it back to us?” ranted Zeng Xianglong, a psychology professor at Beijing Normal University, in an interview mid-year. His angry comment was directed at mindfulness, a meditation practice focused on the present moment. This practice is also experiencing a boom in China. In wealthy metropolises such as Shanghai and Shenzhen, mindfulness studios have sprouted up in the past three years. Hundreds of mindfulness apps entice people with guided meditations, videos, or music tracks that are supposed to relax, alleviate anxiety or help you fall asleep. Even large Chinese corporations like Huawei and Didi Chuxing now offer their employees breathing exercises to reduce stress. The underlying idea behind this trend, which has been adopted from Silicon Valley, is that people who feel inner peace work more efficiently.

But Professor Zeng is right: The current trend is indeed coming from the West. But China is the birthplace of mindfulness. Mindfulness meditation has been practiced for centuries in Chinese Chan Buddhism. The communists initially saw individualistic introspection primarily as a superstition. During the Cultural Revolution, practitioners were openly attacked and Buddhist temples were destroyed.

Western-modern mindfulness meditation, largely stripped of its religious context, now traces its origins in part to the American scientist Jon Kabat Zinn. When the professor for molecular biology first traveled to China in 2011, he praised the positive reactions of the largely secular Chinese, saying: “It felt like the closing of a certain kind of karmic circle.”

Young Chinese regard traditional mindfulness exercises such as Tai Qi, Qi Gong, or calligraphy as a pastime for pensioners. To escape their stressful daily lives, younger people instead prefer to turn to a mindfulness app – even if it’s just in the form of a ten-minute headphone meditation on the subway. “If anything, the lack of a religious component adds to the popularity of mindfulness in China,” says Dalida Turkovic, who runs the Beijing Mindfulness Center near Beijing’s Lama Temple. The mindfulness instructor, who was originally a trained business coach, came to China in 1993. After her home country Yugoslavia fell apart, she suffered from depression for years. Through traditional Chinese martial arts, she eventually stumbled upon mindfulness meditation, which she says helped her out of the worst of her crisis. “Unlike traditional teachings like Qi Gong, the Western way of mindfulness strengthens psychological self-awareness,” the 52-year-old explains.

For many Chinese, mindfulness is nowadays above all a lifestyle. The market for Chinese mindfulness apps is thus highly competitive. Top dogs like Headspace or Calm in the West have not yet found their way to China. Platforms available in Chinese, such as Tide (潮汐) or Now Meditation (Now冥想), which was founded in 2016, offer content similar to their Western counterparts. However, they also offer workshops and in-depth courses at the in-house Mindfulness Academy for an additional fee.

In response to the Covid-19 outbreak, almost all start-ups introduced special relaxation exercises designed to alleviate the worst existential fears. “In these uncertain times, many Chinese have experienced crises of meaning,” says Dalida Turkovic of the Beijing Mindfulness Center. The lockdowns have also contributed to the uncertainty. “Many don’t believe that anything will change between now and the Olympics. A good opportunity to take a good look at oneself.”

The Covid pandemic has also thrown a spotlight on mental health in China. The World Health Organization estimates that around 54 million people in the People’s Republic suffer from depression, 41 million from anxiety, and 300 million from insomnia. Of course, economic pressures also play a role. Working six days a week from 9 AM to 9 PM has become the norm for many Chinese, especially in the tech industry (China.Table reported). This does not leave much time for dealing with problems and the search for meaning. The fact that Hou Xi, one of the co-founders of the Chengdu-based meditation app Ease, used to work as a banker for Goldman Sachs speaks volumes.

In Chinese society, mental health problems are still widely stigmatized. According to the World Mental Health Survey, a global survey conducted by the World Health Organization, 87 percent of concerned Chinese do not consult a doctor when they are struggling with mental health issues. The global average is 48 percent. Adjustment disorders or mild to moderate depression are usually not even classified as illnesses in China and accordingly remain untreated. In her book “Mental Health in China” (Polity Press, Cambridge, 2018), anthropologist Jie Yang argues that the taboos surrounding mental illness can be traced back to the collectivist Confucian heritage, but also to the Mao era when psychology was demonized as a “bourgeois pseudoscience”.

Online platforms such as Know Yourself (知我探索), Jiandan Xinli (简单心理) or Yi Xinli (壹心理) aim to close this gap in the Chinese healthcare system with a mixture of wellness, psychotherapy and spiritual search for meaning. Articles published on “Know Yourself” on topics such as “building self-confidence,” “self-care,” or “career pressure” are read several hundred thousand times on average. In addition, the Shanghai start-up recommends certified video therapists to its users. On WeChat alone, Know Yourself has around 2.8 million followers.

The Chinese call the trend towards psychological self-help Xinling Jitang (心灵鸡汤): “Chicken soup for the soul”, based on the eponymous US self-help guide, which also happens to be extremely popular in China. In China’s book market, self-help titles now account for an estimated one-third.

Beijing welcomes citizens’ initiative, as China still lacks mental health professionals. The World Health Organization (WHO) calculated in the last survey in 2017 that there are fewer than nine psychiatrists for every 100,000 Chinese. In its “Healthy China 2030” initiative, the Chinese government therefore explicitly recommended meditation as a method of dealing with lockdown stress.

Of course, there is also an economic factor to it: China wants to generate more and more of its economic growth in the service sector. Wellness offers are playing an increasingly important role in this. The turnover in the Chinese yoga market alone was estimated at ¥46.8 billion last year (€6.5 billion). The Shanghai-based mindfulness center “Creative Shelter” is even developing soundproof meditation chambers that, like the ubiquitous massage chairs in China, should one day be in every shopping mall. “Spiritual care can also bring economic benefits,” explains state broadcaster CCTV2.

The CCP, however, is likely to keep a close eye on the development of wellness and the mental health movement. In China’s history, spiritually tinged physical training has often led to open rebellion, for example, when the so-called Boxers rebelled against foreigners at the end of the Qing Dynasty or when the Red Turbans overthrew Mongol rule in the 14th century. The most recent case of a mass spiritual movement occurred in the 1990s. At that time, the meditating disciples of the Falun Gong wanted to tend to the spiritual needs of the many Chinese who were looking for support during the rapid social changes.

Initially, Falun Gong was supported by the government. However, when membership exceeded 70 million – more than the Communist Party had at the time – the movement was banned by the head of state Jiang Zemin as a “spiritual opiate” and a “danger to social stability”. Its members were subsequently rigorously persecuted. What “inner peace” is, and how to maintain it, is determined by the party alone. Fabian Peltsch

Visually, the electric flying vehicle, whose design was recently unveiled by Xpeng subsidiary HT Aero, looks like something out of a James Bond movie: In addition to its four wheels, the sleek, lightweight two-seater has two elongated rotor arms with a wingspan of a good 12 meters. When they are folded, the vehicle is a roadworthy sports car. Once they are unfolded, however, it becomes a passenger drone with vertical take-off ability. In addition to two airbags, it is also equipped with parachutes as a safety feature.

The vehicle, which doesn’t yet have a name, will have a steering wheel for road travel and a single lever for flight mode, Techcrunch magazine reports. According to the company, it will also have an advanced perception system that can fully assess the environment and weather conditions before takeoff.

The start of production is targeted for 2024. The design of the mini-aircraft is not yet final and could still be subject to change until it is fully ready for the market, the company explains. The price could probably be the equivalent of around €140,000.

Guangzhou-based startup HT Aero recently raised around $500 million in venture capital. The company speaks of the largest venture funding round to date for a startup in Asia’s passenger aviation sector. The large number of high-profile backers shows that investors have faith in this new market segment. The cash injection for HT Aero will mainly go towards research and development and recruiting new top talent, explains Zhao Deli, founder and president of the company.

This year alone, some $4.3 billion has been invested in flight car startups through August, according to Financial Times. US consultancy Morgan Stanley predicts that the market for flying cars will be worth $1.5 trillion in as little as 20 years. The consultancy Roland Berger expects around 160,000 commercial shuttle drones to be flying through the skies worldwide in 2050.

Through their road capability, flying cars differ from what has been developed so far under the name of air taxis. Some manufacturers are already testing taxis or flying drones. But these are not flying road cars with wheels so far. Instead, they take off vertically from fixed places. Whether HT Aero’s flying car, scheduled for 2024, will also be able to switch from driving to flying mode is still uncertain.

Xiaopeng and HT Aero have already unveiled several predecessor models that are also electric, including the manned Voyager X1 and X2. Both are still in development and have already successfully completed more than 10,000 test flights, according to a report in the trade magazine Elektrek. Road testing is expected to start in China later this year. According to the company, the X2 can handle a maximum take-off weight of 760 kg including two passengers, with a maximum flight duration of 35 minutes. The projected flight altitude is below 1000 meters.

Due to their limited range, for the time being, air taxis like these will initially find a primary use on short urban routes at low altitudes, such as shuttle services to the airport. But that’s exactly the type of use that is needed in China’s congested cities.

But the competition never sleeps. Numerous air taxi competitors include US start-up Joby Aviation, which is supported by Toyota, among others, and the German start-up Lilium from Weßling in Bavaria. Lilium counts Chinese tech giant Tencent among its investors.

In Europe, the Dutch company Pal-V is way out in front when it comes to flying cars with road capability. It plans to begin series production of its flying car Liberty this year – according to its own information, the first company in the world to do so. The aircraft has already been certified by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). A certification that is also accepted in China and the USA. The Liberty, a two-seater based on gyrocopter technology, can fly for four hours or 500 kilometers, but at the same time travel at 160 Km/h on the road with three wheels. With its rotors folded, it is no bigger than a normal car.

VW has also announced plans to launch a feasibility study in China on flying cars. The Wolfsburg-based company also wants to push ahead with its own investments and the hunt for a potential cooperation partner as soon as possible. In March, Chinese automaker Geely announced plans to bring a flying car to the Chinese market by 2024 as well. Onboard with the Chinese is the German startup Volocopter, which is headquartered in the Baden-Wurttemberg town of Bruchsal.

However, HT Aero’s biggest competitor in China is currently the company EHang, which also comes from Guangzhou. The startup, which has been listed on the stock exchange since 2019, has developed the EHang 184 passenger drone and the EHang 216 two-seater, two of the most sophisticated electric air taxi models to date. However, even EHang has yet to produce road-ready flying cars. The company claims to have sold 70 units of its “autonomous flying objects” last year. However, it may well be that EHang will also move quickly into flying car development: The focus of its know-how is on flying, not driving.

Xiaopeng Motors and HT Aero are planning mass production for the unnamed flying car as early as 2024. However, this seems very ambitious considering the regulatory hurdles and the lack of a uniform set of rules nationwide. Only a few provinces, such as Anhui and Jiangxi, have so far introduced pilot zones where air taxis are allowed to be tested throughout. In addition to technical issues, there is also the question of where air cars and air taxis are allowed to take off and land.

Unlike most developers, who mainly sell their air vehicles to companies, HT Aero wants to sell mainly to private customers. Company boss Zhao explains that HT Aero’s air taxis will also be used for aerial tours, police missions, or emergency rescues. Numerous bases on the ground will provide monitoring and remote control in case of an emergency. But the X2 first needs regulatory approval. Only then can the aircraft take to the skies.

Sinolytics is a European consulting and analysis company that focuses entirely on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in China.

Greenland has withdrawn the license for an iron ore deposit near the capital Nuuk from a Chinese mining company. The reason was years of inactivity at the Isua site, the government announced on Monday. The Hong Kong-based company, called General Nice, also failed to make the agreed guarantee payments, it said. “We cannot accept that a license-holder repeatedly fails to meet agreed deadlines,” Greenland’s Resources Minister Naaja Nathanielsen said. The government announced it would offer the license to other interested companies after General Nice officially returned it, according to a Reuters report.

The deposit has been in the sights of Chinese interested parties for years, but in the end, they never became active. In 2013, British company London Mining was granted the mining license. The company wanted to hire around 2,000 Chinese workers to build the project and supply China with around 15 million tons of iron ore per year. But it failed to secure funding, and London Mining went bust. General Nice, a Chinese importer of coal and iron ore, took over in 2015.

Resource-rich Greenland and the Danish government have viewed Chinese investment with skepticism for years. When General Nice wanted to buy an abandoned naval station in Greenland from Denmark in 2016, Copenhagen vetoed the deal over security concerns, sources told Reuters at the time. In 2018, Greenland also rejected a bid by a Chinese state-owned bank and a state-owned construction company to finance and build two airports in Greenland. That year, the new government in Nuuk banned uranium mining on environmental grounds, effectively halting the development of the Kuannersuit mine. It is considered one of the world’s largest deposits of rare earth deposits. Chinese company Shenghe Resources had previously secured mining rights there. ck

Singapore’s former ambassador to the United Nations, Kishore Mahbubani, has warned of the chance of a nuclear war between the US and China. The Taiwan conflict could escalate if Washington does not adhere to its one-China policy, Mahbubani said at an event marking the 25th anniversary of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation’s Media Programme Asia in Singapore. China is “a rational actor in all fields, with one exception: on Taiwan, China is an emotional actor,” he said. Should Washington or Taipei, on the other hand, try to push through Taiwan’s independence, contrary to US President Joe Biden’s assurances, a “red line” would be crossed for Beijing, warns the high-profile, but in part also controversial political observer.

At the event, Mahbubani discussed the issue with former German magazine Spiegel chief Stefan Aust, who has just published a book on Xi Jinping. According to Aust, it is China that wants to change the status quo. Mahbubani disagreed, saying, “The Chinese will not go out and occupy Taiwan on their own.” Without external provocations, China would postpone such ambitions for a few more years until it was “the world’s largest economic power.” For the time after that, Mahbubani then suggested a willingness on Taipei’s part to rejoin the mainland after all.

The situation around Taiwan seems tense at the moment: From the Chinese side, the small and large provocations are piling up (China.Table reported), while Biden has used the word “independence” in connection with the island. His aides have interpreted the remark as an oversight. His staff has interpreted the remark as a misunderstanding. But Beijing could take the change in language as an indication of policy change. fin

Russian President Vladimir Putin has pledged his presence at the kick-off of the Winter Olympics in Beijing. “Xi invited his good friend Putin to attend the opening ceremony of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing,” a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman said Tuesday. This, he said, shows once again how deep the partnership between China and Russia is. “China and Russia have a fine tradition of celebrating major events together.”

Beijing is emphasizing the visit from Moscow in such a conspicuous manner because US President Joe Biden has already considered a diplomatic boycott of the Olympics due to human rights violations in China. The UK would potentially join such a boycott. This means that no official government delegation from either country would travel to Beijing. Putin, on the other hand, stressed that Sino-Russian relations are “stronger than ever”, according to state media reports. The Winter Games will be held in February 2022. fin

China is at risk of missing its own solar energy expansion target this year. Due to rising prices in solar supply chains, photovoltaic cells became more expensive in 2021 for the first time in eight years, Bloomberg reports. As a result, China has so far added only 29.3 gigawatts of solar capacity between January and October, the news agency reports, citing China’s National Energy Commission. This is far below the China Photovoltaic Industry Association’s annual projection of 55 to 65 gigawatts of new photovoltaic capacity.

China’s renewable energy developers often install large parts of their capacity at the end of the year to meet subsidy deadlines as well as their own targets, according to Bloomberg. This year, however, such a surge became less likely over the recent months: The government no longer offers subsidies for most large-scale solar installations, and the quota for rooftop solar subsidies had already been almost reached by the end of October. The world’s largest solar module manufacturer, Longi Green Energy Technology, expects only 40 to 45 gigawatts of new capacity in 2021, Bloomberg writes, citing analysts at Morgan Stanley.

For years, China has been installing more photovoltaic systems than any other country. State and party leader Xi Jinping had recently surprised with the announcement that he wanted to build 100 gigawatts of capacity for wind power and solar energy in China’s deserts. Parts of the projects are already under construction (China.Table reported). But the pace of expansion could now slow down. ck

Wuling, the joint venture between General Motors and Chinese carmaker SAIC, unveiled the “Nano” version of the Wuling Hongguang Mini EV on Monday. With a length of 2.50 meters and a wheelbase of 1.60 meters, the Nano EV is even smaller than the standard model. The car’s length is 42 centimeters shorter, while the wheelbase is 34 centimeters. The sleek two-seater comes with a 24-kilowatt electric motor. It is said to travel 305 kilometers on one battery charge. The company, which is based in Liuzhou in the southwest of China, has not yet given any information about the battery capacity.

The Wuling Hongguang Mini EV remains one of the best-selling EVs in China (China.Table reported). Between January and September, it accounted for more than a fifth of new registrations. The vehicle fills a gap in the People’s Republic. Many Chinese who previously only drove trikes and e-scooters now have enough purchasing power to afford a low-cost microcar as an entry-level vehicle. The driver airbags and parking sensors available in the Nano are downright luxuries for this clientele. Depending on features, the Nano costs between €6,300 and €8,300. Despite its smaller dimensions, this makes it more expensive than the standard model. The full-size Wuling Mini EV is available in China for as little as €4,000. fpe

Population growth in China has slowed. According to the latest Statistical Yearbook by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, there were 8.5 births per 1,000 people last year. This data shows that China’s birth rate in 2020 has dropped by the most since 1978. The Health Commission had already stated in July that the number of newborns in China could soon decline again. Official agencies did not want to comment on the reasons for the developments.

At the same time, census data was revised upward: A higher birth rate than previously estimated was recorded for the years from 2011 to 2017. He Yafu, an independent demographer, told Bloomberg that the change “likely reflects undercounting of births in previous years.” Experts had expressed surprise at the level of decline in China’s birth rate after the official population data was released earlier this year (China.Table reported). But many couples, especially in China’s big cities, no longer want a second child because of the high cost of living and education, although Beijing has been allowing families to have three children a few months back for fear of over aging.

Meanwhile, statistics released by the Ministry of Civil Affairs show that 5.88 million marriages were registered in the first three quarters of this year. According to state-run Global Times, this is a 17.5 percent drop from last year. But not only did the number of marriages fall during the pandemic, but the number of divorces also dropped. In the first half of this year, only 966,000 marriages were divorced – 50 percent less than in the same period last year. niw

Over the past two decades, business expenditure on research and development (BERD) has been the main driver of R&D growth in China. The annual BERD growth rate was consistently higher than the average growth rate of OECD countries. At the same time, government support for R&D spending in China officially reached only 4.3 percent between 2003 and 2018, well below the OECD average of 6.7 percent. To become more innovative, China’s R&D spending is expected to increase by at least 7 percent annually over the next five years, supported by government R&D subsidies. However, this is not enough: As a recent study by the ZEW (Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research) in Mannheim shows, R&D subsidy misuse has been widespread in China in the past and has long stood in the way of efficient use of state subsidies.

For this reason, a reorientation of China’s innovation and industrial policy was already accompanied by numerous measures in 2006, both to improve funding instruments and to curb their misuse. If such measures take even better effect in the future, China will become an increasingly innovative competitor on the global market and at the same time gain in popularity as an R&D location for foreign companies.

The share of subsidy beneficiaries among listed companies in China has increased enormously since the turn of the millennium: While it was 32 percent in 2001, it was already 90 percent in 2011. On average, about 10 percent of total government subsidies to enterprises were specifically earmarked for R&D activities. However, our study shows that about 42 percent of R&D subsidy beneficiaries spent all or at least part of these government funds on non-research purposes between 2001 and 2011. This form of subsidy abuse was measured by comparing the R&D expenditures published in each firm’s annual reports and R&D subsidies received. Overall, 53 percent of all subsidy payments earmarked for R&D went to other, i.e. non-research, purposes. For example, subsidies are often misappropriated to cross-subsidize non-R&D-related investments, which can also lead to rapid reductions in production costs and distort competition on international markets.

The study results indicate that R&D spending did increase as a result of subsidies, but the increase among subsidized companies could have been more than twice as high as it actually was. The government R&D subsidy also led to the increase in investment in fixed assets, employment, and sales among companies. Furthermore, the analysis also reveals optimization potential in the selection of eligible companies. So far, R&D subsidies had no effect on state-owned companies, and support for the high-tech sector should also be more differentiated in the future. According to study results, in addition to misuse of subsidies, payments occurring too frequently or at too high a rate could also lead to inefficiencies.

Further, we find that misuse is declining significantly over time, from 81 percent in 2001 to 18 percent in 2011. The Chinese government also achieved this decline through its “Medium- to Long-Term Plan for the Development of Science and Technology”. Through it, China has already been able to address some structural problems in its innovation system and implement necessary improvements. In addition, the administration of subsidy programs has been restructured in such a way that companies can now be selected more precisely and the use of subsidies can be better controlled. These reforms were already having a significant impact. However, in 2020 there was still extensive misuse of state support in semiconductor manufacturing, a key industry for the technological sovereignty China is striving for.

China has not yet proven that it is more capable of generating innovation and cutting-edge technology than the world’s leading innovation systems in the United States. However, if China succeeds in further improving the design and implementation of its innovation policy with the 14th Five-Year Plan, it can be expected that future business productivity will also increase, resulting in higher economic growth due to “Innovation Made in China”. Politics and business in the US and Europe should already be gearing up for a further intensification of competition, especially in high-tech sectors.

Bettina Peters is Deputy Head at ZEW’s “Economics of Innovation and Industrial Dynamics” Research Department, Honorary Professor in Innovation at the Faculty of Law, Economics, and Finance at the University of Luxembourg. Philipp Böing is Senior Researcher at ZEW

This article is part of the Global China Conversations event series of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). On Thursday, Philipp Böing, Senior Researcher at ZEW in Mannheim, and Wolfgang Krieger, Deputy Managing Director of the Federation of German Industries (BDI) in China, will discuss the topic: “Innovation Made in China” – How effective is Beijing’s innovation policy? China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

HSBC Asset Management has appointed Daisy Ho as its new Regional Chief Executive for the Asia Pacific and Hong Kong. Ho is based in Hong Kong and reports to Chief Executive Nicolas Moreau. Ho has more than 20 years of experience in the asset management industry at JP Morgan, AXA, and Hang Seng Bank, among others, and joins from Fidelity International, where she was most recently President for China.

June Wong has been elected Group President of Hong Kong-based asset management firm Value Partners. Wong has three decades of experience in the industry and is a member of the Advisory Committee of Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission regulator.

Ping-Pong Diplomacy in action: Two US-Chinese mixed teams train for the World Table Tennis Doubles Championships in Houston, Texas. The US and China are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the so-called Ping-Pong Diplomacy, which once ushered in a thaw between the two countries, thanks to historic teamwork. Pictured in front are US’s Lily Zhang and China’s Lin Gaoyuan. Playing in the background are China’s Wang Manyu and US’s Kanak Jha. The World Championships kicked off on Tuesday. The Wang/Jha duo could face German European champions Dang Qiu and Nina Mittelham in the second round of the competition.