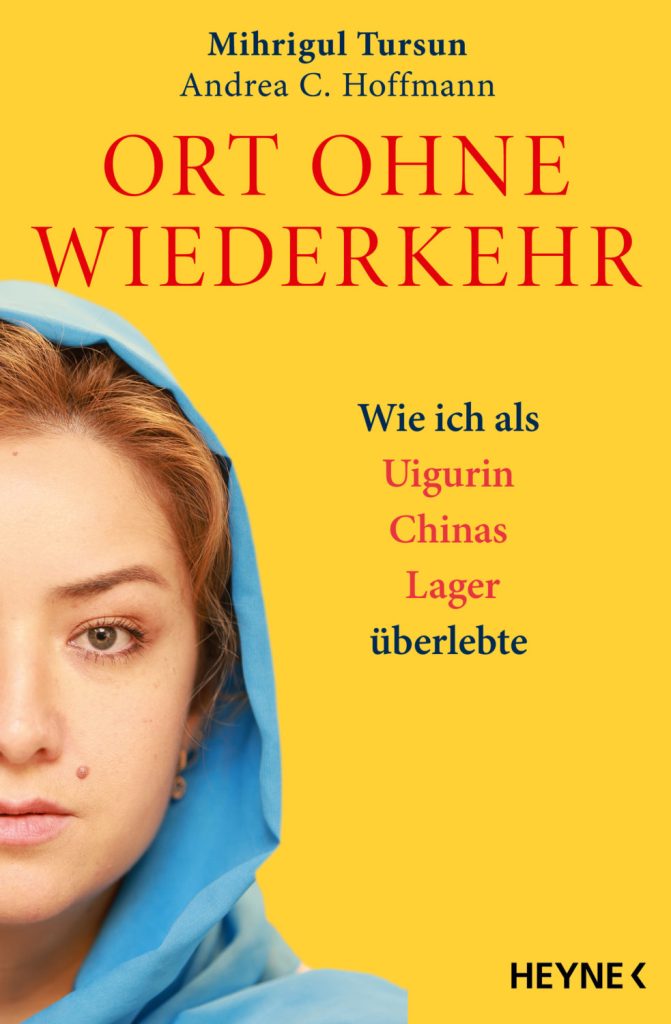

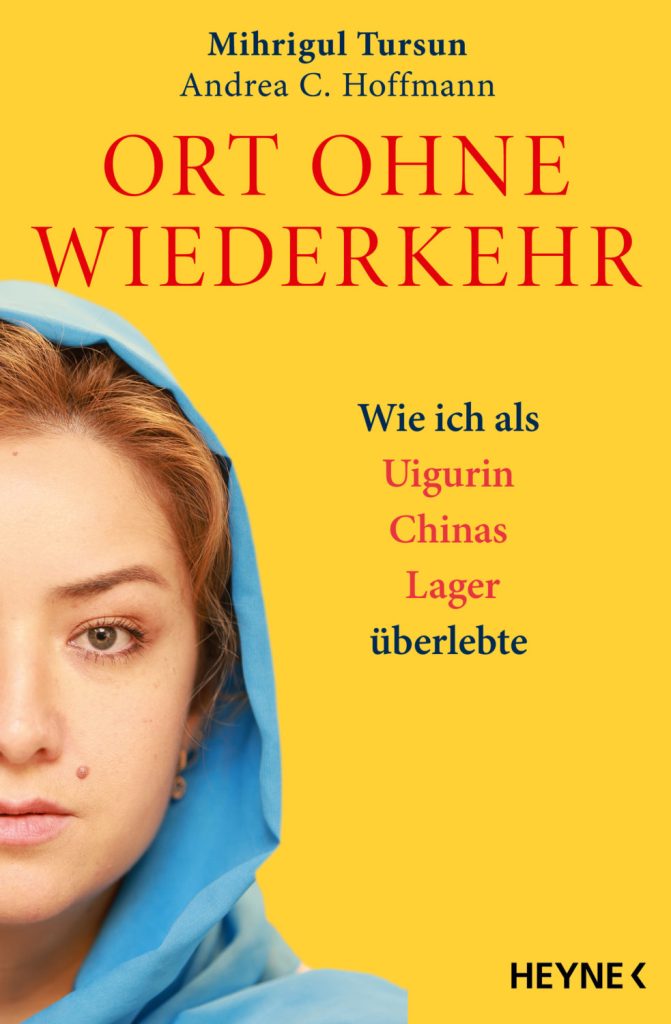

The eyewitness story of Mihrigul Tursun is currently shocking first readers. The Uyghur woman was detained in Xinjiang in one of these feared camps. One of her children died under unknown circumstances during this time. Tursun had attracted the suspicion of the authorities by studying abroad. She wrote about her experiences in her book, “Ort ohne Wiederkehr,” (Place of no return) which was published last week.

Such witness reports of the situation in Xinjiang are vital. After all, China is trying to keep the events in Xinjiang suppressed by all means. First, they denied the existence of camps. Then, they were merely for vocational training. Tursun’s book now makes clear: They were, at least in part, places of torture. In today’s interview, Marcel Grzanna spoke with Tursun about her experiences.

Today’s second topic revolves around a point of contention between the EU and China on climate protection. As part of its “Fit for 55” program, the EU wants to introduce a complicated CO2 border tax, the form of which is still being debated. It is intended to prevent products from countries with lower CO2 prices from entering the EU market too cheaply. Ning Wang has taken a closer look at the plans and explains where the conflicts lie. China is keeping a close eye on the project, fearing high costs.

Have a pleasant week!

The authorities in Xinjiang have accused Mihrigul Tursun: She thinks “too Uyghur.” She was three times detained in internment camps for several weeks, beaten and tortured with electric shocks. One of her babies died under unexplained circumstances in the care of the authorities. Meanwhile, her Egyptian husband applied 18 times for a visa at the Chinese embassy in Cairo until he was allowed to enter the country in 2018. In exchange for a promise not to go to court abroad over the dead child, Tursun was granted permission to return to Egypt. She eventually turned to the United States for help, where she sought asylum and testified before Congress. Now, together with German journalist Andrea C. Hoffmann, Tursun has written a book about her experiences. “Ort ohne Wiederkehr – wie ich als Uigurin Chinas Lager überlebte” (Place of No Return – How I Survived China’s Camps as a Uyghur, Heyne, 277 pp.) is a chilling testimony to Chinese human rights crimes in Xinjiang.

Ms. Tursun, what memories do you have of the 2008 Olympics?

At that time, I was very proud that China was hosting the Olympic Games, and I enjoyed watching the competitions on TV. I didn’t even know at that time that the Olympic Games always take place in a different place every four years. Through propaganda, I was firmly convinced that only China would ever be able to host such an event.

Why?

Because everything that was conveyed to us through state media about foreign countries consisted only of chaos and incompetence. Everywhere the world was bad, only in China was life safe and good. That was not only my opinion but the opinion of most people I knew. It wasn’t until I went abroad that I even realized that elsewhere in the world life can be worth living and other societies have perfectly good capabilities.

Next week, the Olympic Games will once again be held in Beijing. What do you feel today?

I look at these Games with disgust. I would like the whole world to boycott these Games. Once everyone has a better understanding of what exactly is happening in China, and especially in Xinjiang, then perhaps many will regret their participation in these Games later on.

There is indeed a growing awareness in democratic states of the catastrophe in Xinjiang. Last week, the French parliament condemned the human rights crimes there as genocide.

I truly cheered and am so grateful for this signal from the French. Here in Washington, people took to the streets waving French flags.

Germany has a hard time with the term genocide.

I hope that will change. Germany enjoys a very high status among the Uyghurs because we grew up with the quality seal “Made in Germany” in our heads. In our minds, Germany was a perfect country that did everything right.

Volkswagen’s CEO once denied any knowledge about camps in Xinjiang.

Making money is not everything. It comes and goes. At the end of life, the only question that remains is, what have you done for humanity in the world? At some point, Mr. Diess’ conscience will also ask him this question. He should be aware that he represents his country and shapes its image. Many people trust Germany. If he considers good business with China to be more important, that will also shake confidence in his country.

Why did you go public with your story?

I never cared about politics. I have always wondered why people don’t just live in peace. But the Chinese government has done horrible things to my family, my people, and me. They torture and kill us. During my total of three months of imprisonment, nine people died where I was held. Why are they doing this to us? I want an answer to that.

Are you afraid of Chinese revenge?

No, I am ready to die for it because I know I am doing the right thing. They took my child and my family. I lost my hope, my dreams, my health. I felt like I was dead. But my second life told me, take care of your other two children.

Were there any threats against you?

Yes, they threaten to lock up my entire family. My father called me. A voice in the background told him to talk. He told me to report to the Chinese embassy. They would help me there. There were also several incidents after I testified before the US Congress. I was being followed and I received messages. One time my cab was rammed by a stolen vehicle. The other driver took out a gun and pointed it at me. My cab driver put my head down and sped off. I reported all of these incidents to the FBI. That was two years ago now. There hasn’t been a threat since the book was published.

Are there moments when you can be carefree again?

No, I have not experienced that yet. I sometimes wish my doctor could erase my terrible memories so that I could live carefree again.

Do you have plans for the future?

I feel safe in the USA. I hope that my asylum application will be approved soon and I can then stay here with my family for the rest of my life.

The EU has adopted an ambitious climate program, the “European Green Deal”. Its goals are ambitious; by 2030, the EU plans to reduce CO2-equivalent emissions by 55 percent. By 2050, the EU wants to be climate neutral. But the path is complicated: The “Fit-for-55” package of measures is huge, and many measures are causing heated debates. Nevertheless, the majority of the package is still to be adopted in 2022.

Some issues have a major impact on the EU’s trading partners – and thus on China. The biggest issue in this respect is the planned Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The government in Beijing is looking at this project with great concern – also because the Chinese government does not quite know what is in store for its companies. The fear is that the EU’s new rules will increase the cost of importing Chinese goods.

CBAM is to prevent goods from countries with less restrictive emissions regulations and lower CO2 prices from competing with goods produced in Europe, which are more expensive due to a higher CO2 price. This is because more climate-damaging products could thus undercut the prices of their EU competitors. CBAM is thus closely linked to the European Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS), which sets the price of greenhouse gas emissions in Europe. In other words, from a European perspective, if China does not adequately price the CO2 emissions of its companies, then the EU will mark up imports.

In this way, the EU wants to ensure that it can achieve its climate targets without energy-intensive industries moving abroad. This process is known as “carbon leakage.” Companies simply relocate high-emission processes to other parts of the world in order to save money – without helping the climate. However, critics also fear that CBAM could lead to trade conflicts with other countries like China. (Europe.Table reported).

First, a brief explanation: The EU ETS operates according to the cap-and-trade principle. The EU distributes a fixed amount of emission allowances (cap) to companies according to certain criteria. Companies that reduce their emissions more than required can sell the remaining allowances on the market (trade). A price for the emission of CO2 is created. (Europe.Table reported).

The amount of the future CO2 border adjustment is to be based on the CO2 price of the ETS, which European companies have to pay on a weekly average for the acquisition of EU emission allowances. Companies from third countries are to be able to claim CO2 prices that they have to pay in their home country. The CBAM is to enter the pilot phase in 2023 and will be gradually implemented from 2026 to 2035.

In China’s ETS, the CO2 price is currently significantly lower (China.Table reported). There, the authorization to emit one ton of C02 currently costs the equivalent of around eight euros, while this price in the EU is 80 euros per ton. Chinese export companies will therefore probably have to pay a high CO2 tax in the future. And so it is no wonder that Beijing is showing little enthusiasm for CBAM (China.Table reported).

According to a study by Chatham House, China is one of five countries that will be most affected by CBAM. This is because China exports more goods and services to the EU than any other country in the world. In 2020, goods worth €586 billion were traded between China and the EU. That corresponded to 16 percent of the EU’s foreign trade, according to data from the German Federal Statistical Office. By comparison, the US was at 15 percent.

China is threatened with severe impacts, particularly in sectors with above-average emissions, especially in heavy industry. Take iron and steel, for example: China is the second-largest exporter to the EU in this sector, (according to data from 2015-2019). But also the energy-intensive aluminum industry would be strongly affected by a CO2 border adjustment (China.Table reported). As a result, experts expect great resistance from the People’s Republic, especially in these sectors.

But it is still difficult to determine the extent of any impacts, given the feud within the EU over the CBAM draft. “The Chinese side is not only concerned about what the CBAM system looks like in its early stages – but also how it might evolve,” says Lina Li, Senior Manager Carbon Markets and Pricing at environmental and climate consultancy Adelphi. The debate on expanding the scope of CBAM and including indirect emissions is causing particular concern among Chinese stakeholders, Li said. In its CBAM proposal, the EU Commission has named iron and steel, concrete, fertilizer, aluminum, and power generation as industries to be included. But EU Parliament recently proposed to also include organic chemicals, hydrogen, and polymers. (Europe.Table reported)

The financial impact of CBAM on China could thus increase significantly in the future, says Lina Li. According to a study by the Development Research Center of the State Council in Beijing, the EU’s CBAM plans could reduce China’s economic growth by up to 0.64 percentage points. That could cost millions of jobs in manufacturing. CBAM could increase the cost of exports to the EU by three percent, thus reducing exports of manufactured goods to the EU by 13 percent. In addition, if the CO2 price difference between the ETS of the country of origin, say China, and that of the EU ETS is significant, “then the costs for affected companies under the CBAM will grow.” And that is currently the case.

Few countries worry as much as China, according to Li. “We are having discussions with experts from Africa who fear CBAM could hit them hard. But the volumes from Africa are negligible,” Li tells China.Table. The US is also less concerned than China because its production has higher efficiency and lower emissions, she says.

And China’s ETS will not become compatible with the EU ETS, at least in the short term. Corinne Abele, Head of Foreign Trade at GTAI in Shanghai, estimates that the price of CO2 emissions in China will remain well below the price level of the European ETS. Linking the Chinese ETS with other international systems is therefore hardly possible for the time being.

The Chinese ETS also covers significantly fewer industries to date. So far, only a good 2,200 companies from the power sector are involved. However, two industrial sectors are expected to be added this year. According to Lina Li, the aluminum industry could be included as early as this year. Up to seven other sectors are to be added over the next five years:

This puts China in a good position to discuss bilateral agreements with the EU to mitigate impacts from CBAM, Li believes.

In a telephone conversation with former German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron in April 2020, China’s head of state and party Xi Jinping stressed that climate change should not be misused as an instrument for geopolitical negotiations. Representatives of affected industries remember this all too well. So much so, that immediately after the presentation of the EU climate package in summer 2021, the European aluminum industry speculated that China would find ways to undermine the CBAM at any cost. The details of CBAM will still require much negotiation within the EU – and presumably with China.

Olympic gold medalist Georg Hackl sees the Olympic Games in Beijing endangered by the Omicron wave. In an interview with the German Sunday newspaper, Die Welt am Sonntag, the 55-year-old doubted the Games could be held if parts of different teams had to be continuously isolated. He outlined the scenario of a positive test in the team immediately after arrival in Beijing. That would exclude entire teams from participating.

The head of the German snowboard federation, Michael Hölzl, also expects problems arising from the Covid situation in China. In a podcast, he warned that China could “take out” athletes with fake-positive covid tests to keep unwanted competition out of Games. The IOC, meanwhile, defended China’s testing policy. It said it was a legitimate goal to keep Omicron from entering the Olympic bubble.

China’s authorities are also concerned about the development of Covid. All residents of Beijing’s Fengtai district are currently required to undergo Covid tests. In Fengtai, six new Covid infections had been registered, with the infected also showing symptoms. Beijing registered a total of nine cases.

Beijing Games organizers also said on Sunday that they had identified 72 Covid cases among the 2,586 volunteers and staff. Those who tested positive arrived in China between Jan. 4 and Jan. 22. However, no cases occurred among the 171 athletes and officials who entered during that period. The Games begin on February 4th. fin/rtr

The US government will temporarily cancel 44 flights operated by Chinese carriers Air China, China Southern Airlines, China Eastern Airlines, and Xiamen Airlines from the United States to the People’s Republic. This was the US government’s response to the Chinese government’s decision to suspend flights operated by US airlines over covid concerns. The suspensions will begin on Jan. 30 with Xiamen Airlines’ scheduled flight from Los Angeles to Xiamen and continue through March 29, according to the DOT. Since December 31, Chinese authorities have suspended 20 United Airlines, 10 American Airlines and 14 Delta Air Lines flights after some passengers tested positive. rtr

A discussion on how to deal with Taiwan has also started in the Czech Republic. “We have to defend certain values such as freedom, democracy, and the rule of law,” says Nathalie Vogel of the European Values Center for Security Policy (EVC), a Prague-based think tank. Vogel is referring to a change in mood in the country. After the Czech Republic initially moved closer to China in the past decade as part of China’s Eastern Europe Initiative, skepticism is now on the rise. Its position on Taiwan is becoming the focus of debate in the country in the wake of the Lithuania affair.

Ten years ago, China’s leadership wanted to strengthen ties with Central and Eastern Europe through the annual “16 plus 1” format. And for a time, Beijing’s strategy seemed to pay off. All 16 countries were ready for greater economic cooperation. Hungary moved closer to the communist leadership in Beijing. Greece lobbied to be allowed to join the format. Sixteen became seventeen.

But disillusionment has long since set in. Many of the Chinese investment promises have not materialized. Some countries have clashed with China. Lithuania was the first of the 17 European countries to leave this format and is currently engaged in a heated dispute with Beijing over the name of the Taiwanese trade office in Vilnius. A similar dispute has broken out with Slovenia (China.Table reported).

Resentment against Beijing’s aggressive power policy is now also growing in the Czech Republic. “The Chinese people should know that genocide is being committed in their name in Xinjiang,” Vogel said in a video message. The Chinese should also learn “that all hostile activities against individual European states are considered a threat to the EU as a whole.” This would only cause one thing: “greater cohesion toward the People’s Republic.” The fact that a growing number of European states are expressing solidarity with Taiwan is “not the result of any dark forces in the West, but the result of Xi Jinping’s policies.”

Jakob Janda, Executive Director of the EVC, and currently in Taiwan for a research visit, called on analysts, policymakers and security agencies in Europe to learn from the island nation. Taiwan, he said, has had plenty of experience resisting pressure from the communist leadership in Beijing. Europeans could benefit from this experience.

In other news, Taiwan reported on Sunday the most serious violation of its air defense zone by Chinese military aircraft in weeks. 39 aircraft had been ordered not to enter the area, according to the Ministry of National Defense in Taipei. According to the statement, 34 fighter jets, one bomber, and other aircraft had been detected. This was the largest number in a single day since October 2021. Taiwan dispatched fighter jets to warn the Chinese invaders. In addition, missile systems had been deployed to monitor them. No shots had been fired. flee/rtr

The United States-China trade war started in 2018 and has never officially ended. So, which side has been “winning” it? Recent research offers an unambiguous answer: neither. US tariffs on Chinese goods led to higher import prices in the US in the affected product categories, and China’s retaliatory tariffs on US goods ended up hurting Chinese importers. Bilateral trade between the two countries has tanked. And because the US and China are the world’s two largest economies, many regard this development as a harbinger of the end of globalization.

Yet the “deglobalization” argument ignores the many “bystander” countries that were not directly targeted by the US or China. In a new paper investigating the effects of the trade war on these countries, my co-authors and I come to an unexpected conclusion: Many, but not all, of these bystander countries, have benefited from the trade war in the form of higher exports.

To be sure, one would expect exports from third countries (Mexico, Vietnam, Malaysia, etc.) to take the place of Chinese exports to the US. But what is surprising is that these countries increased their exports not only to the US but also to the rest of the world. In fact, global trade in the products affected by the trade war seems to have increased by 3% relative to global trade in the products not targeted by tariffs. That means the trade war did not just lead to reallocation of third-country exports to the US (or China); it also resulted in net trade creation.

Given that trade wars are not generally associated with this outcome, what accounts for it? One potential explanation is that some bystander countries saw the trade war as an opportunity to increase their presence in world markets. By investing in additional trade capacity or mobilizing existing idle capacity, they could increase their exports without increasing their prices.

Another explanation is that as bystander countries started exporting more to the US or China, their unit costs of production declined, because economies of scale allowed them to offer more at lower prices. Consistent with these explanations, our paper finds that the countries with the largest increases in global exports are those in which export prices are declining.

While the net effect of the trade war on the world economy was an increase in trade, there was enormous variation across countries. Some countries increased their exports significantly; some increased their exports to the US at the expense of their exports elsewhere (they reallocated trade); and some countries simply lost exports by selling less to the US and to the rest of the world. What accounts for these differences, and what could countries have done to ensure larger gains from the trade war?

Again, the answers are somewhat surprising. One might have guessed that the most important factor explaining countries’ differing experiences would be pre-trade-war specialization patterns. Countries such as Malaysia and Vietnam, for example, were lucky to be producing a heavily affected product category like machinery. Yet specialization patterns appear to have mattered little, judging by the big export winners of the trade war: South Africa, Turkey, Egypt, Romania, Mexico, Singapore, the Netherlands, Belgium, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic.

What mattered instead were two key country characteristics: participation in “deep” trade agreements (defined as regimes covering not only tariffs but also other measures of behind-the-border protection); and accumulated foreign direct investment. Countries that had a high pre-existing degree of international trade integration benefited the most. Trade agreements tend to reduce the fixed costs of expanding in foreign markets, and existing arrangements may have partly offset the uncertainty generated by the trade war. Similarly, higher FDI is a reliable proxy for greater social, political, and economic ties to foreign markets.

Supply-chain effects also may have played an important role. In a prescient policy briefing based on private conversations with executives at large multinationals, analysts at the Peterson Institute for International Economics predicted in 2016 that US tariffs would “set off a daisy chain of production shifts.”

If a company decided to shift production of a product targeted by Chinese tariffs to a third country, this would necessitate a reshuffling of other activities in the third country, affecting multiple other countries in turn. The exact pattern of these responses would have been hard to predict, given the complexity of modern supply chains. But a country’s degree of international integration appears to have been a decisive factor in a firm’s relocation decisions.

Returning to our initial question, then, the big winner of the trade war seems to be “bystander” countries with deep international ties. From the US perspective, the trade war did not lead to the advertised reshoring of economic activity, at least in the short to medium term. Instead, Chinese imports to the US were simply replaced by imports from other countries.

From the perspective of “bystander” countries, the trade war, ironically, demonstrated the importance of trade integration, especially deep trade agreements and FDI. Fortunately, the Sino-American trade war does not spell the end of globalization. Rather, it may mark the beginning of a new world trading system that no longer has the US or China at its center.

Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg, former Chief Economist of the World Bank Group and editor of the American Economic Review, is a Professor of Economics at Yale University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2022.

www.project-syndicate.org

Shawn Siu will become Executive Director of the troubled real estate group Evergrande. He replaces Lai Lixin. Evergrande is teetering on the brink of insolvency, which is also leading to a staff replacement. Siu comes from the group’s car division.

Webb Ding will become Managing Director of the China subsidiary of Swiss biopharma specialist Oculis on February 1. Oculis is headquartered in Lausanne. Ding has experience at Chinese subsidiaries of Fresenius and Novartis.

Yan Sibo, also known as Steven Yan, will become Managing Director of KHD Beijing, a subsidiary of the concrete group KHD Humboldt Wedag International based in Cologne, Germany. KHD is majority-owned by the Chinese defense group AVIC.

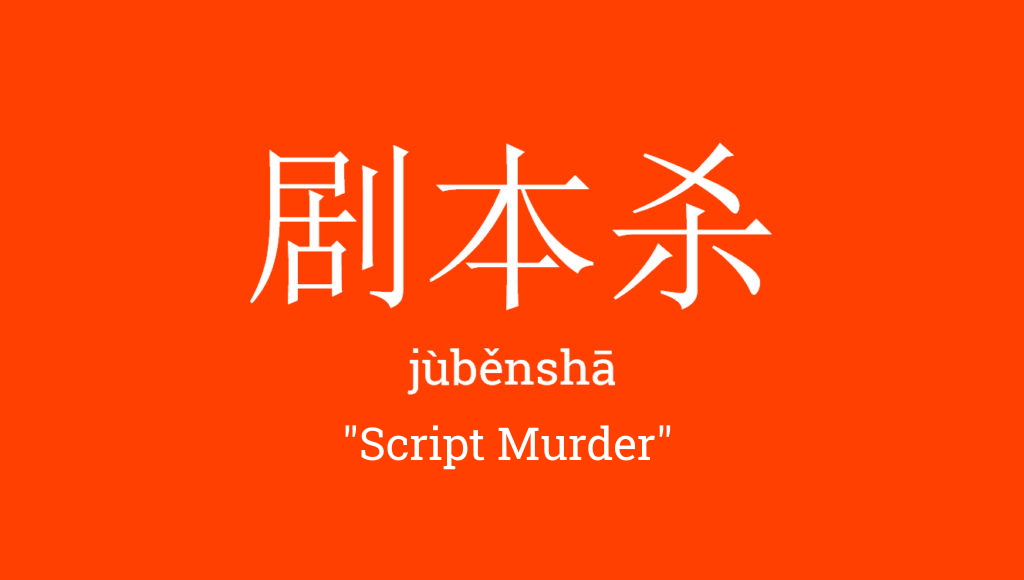

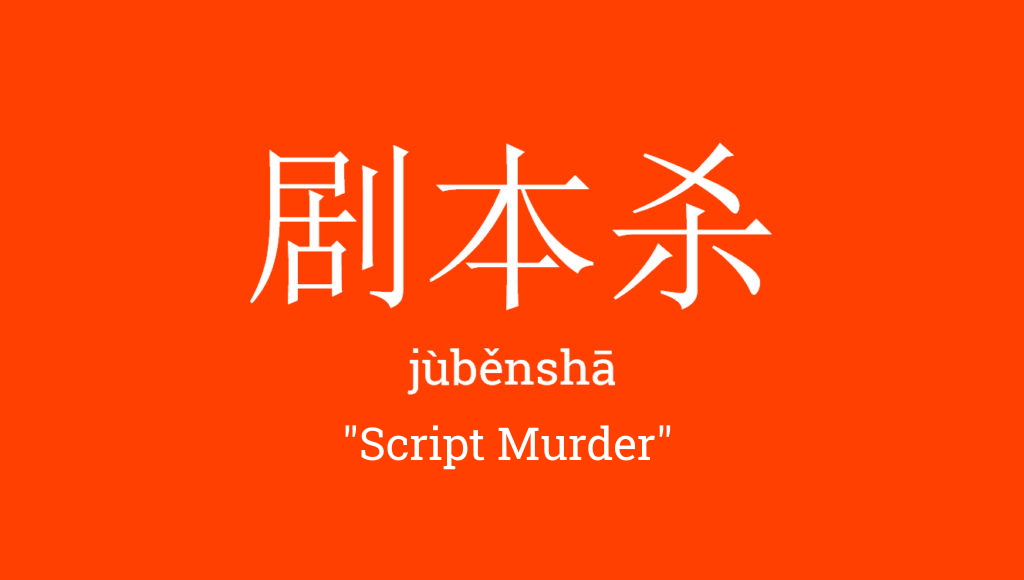

Scripted murder. What sounds like a sinister, bloody deed is actually a new genre in Chinese entertainment that also involves a lot of human interaction. 剧本杀 jùběnshā is the name of the trend in Chinese – made up of the words for “script” (剧本 jùběn) and “kill, murder” (杀 shā).

But at most, only times is getting killed – and in a creative and entertaining way – when young Chinese urbanites meet for a “murder plot“. Jubensha is a kind of enhanced answer to the detective game Cluedo from Great Britain, which already enjoyed great success in the West in the 1990s. In Germany, the classic game, which involves using clues to solve a fictitious murder, was celebrated both on television and as a board game. China has now been expanding the idea into a live role-playing game for several years. There is even a celebrity reality show with the same theme, “Who’s the Murder” (明星大侦探 míngxīng dà zhēntàn), which is going into its seventh season this year.

So business is booming. In metropolises such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Chengdu, new Jubensha experience rooms are popping up all the time, where people can meet to crack criminal cases together. The players gather in real life – a welcome change from the smartphone and computer game world – and run through the game together based on a script. The quality of the script determines the entertainment factor and how deep you ultimately have to dig into your pocket. A round of Jubensha takes two to three hours on average, and the price per head ranges from the equivalent of 10 to 20 euros (for simple plots) to several hundred euros (for particularly elaborate scenarios). The creative scope also varies depending on the script – there are “closed” and “open scripts” (封闭本 fēngbìběn vs. 开放本 kāifàngběn), each with a greater or lesser range of possible storylines.

The most common game variants include: Detective scripts (推理本 tuīlǐběn from 推理 tuīlǐ – “to draw a conclusion”. Task: locate the murderer in the room), team fight scripts (阵营本 zhènyíngběn from 阵营 zhènyíng – “camp, military grouping”. Here, different camps fight each other) or fantasy scripts (变格本 biàngéběn from 变格 biàngé – “change of form; declination”. In this, one may encounter the supernatural or find oneself in a science-fiction scenario). And then there are the adult scripts (小黄本 xiǎohuángběn – literally “little yellow scripts”. As is well known, “yellow” 黄 huáng is synonymous with anything raunchy in China; “yellow” scripts accordingly revolve around “passion, crime and sex”).

For those who also now developed a taste for blood, here are a few more “killer” Chinese vocabulary words (which, on closer inspection, turn out to be less bloodthirsty than they seem):

Verena Menzel runs the language school New Chinese in Beijing.

The eyewitness story of Mihrigul Tursun is currently shocking first readers. The Uyghur woman was detained in Xinjiang in one of these feared camps. One of her children died under unknown circumstances during this time. Tursun had attracted the suspicion of the authorities by studying abroad. She wrote about her experiences in her book, “Ort ohne Wiederkehr,” (Place of no return) which was published last week.

Such witness reports of the situation in Xinjiang are vital. After all, China is trying to keep the events in Xinjiang suppressed by all means. First, they denied the existence of camps. Then, they were merely for vocational training. Tursun’s book now makes clear: They were, at least in part, places of torture. In today’s interview, Marcel Grzanna spoke with Tursun about her experiences.

Today’s second topic revolves around a point of contention between the EU and China on climate protection. As part of its “Fit for 55” program, the EU wants to introduce a complicated CO2 border tax, the form of which is still being debated. It is intended to prevent products from countries with lower CO2 prices from entering the EU market too cheaply. Ning Wang has taken a closer look at the plans and explains where the conflicts lie. China is keeping a close eye on the project, fearing high costs.

Have a pleasant week!

The authorities in Xinjiang have accused Mihrigul Tursun: She thinks “too Uyghur.” She was three times detained in internment camps for several weeks, beaten and tortured with electric shocks. One of her babies died under unexplained circumstances in the care of the authorities. Meanwhile, her Egyptian husband applied 18 times for a visa at the Chinese embassy in Cairo until he was allowed to enter the country in 2018. In exchange for a promise not to go to court abroad over the dead child, Tursun was granted permission to return to Egypt. She eventually turned to the United States for help, where she sought asylum and testified before Congress. Now, together with German journalist Andrea C. Hoffmann, Tursun has written a book about her experiences. “Ort ohne Wiederkehr – wie ich als Uigurin Chinas Lager überlebte” (Place of No Return – How I Survived China’s Camps as a Uyghur, Heyne, 277 pp.) is a chilling testimony to Chinese human rights crimes in Xinjiang.

Ms. Tursun, what memories do you have of the 2008 Olympics?

At that time, I was very proud that China was hosting the Olympic Games, and I enjoyed watching the competitions on TV. I didn’t even know at that time that the Olympic Games always take place in a different place every four years. Through propaganda, I was firmly convinced that only China would ever be able to host such an event.

Why?

Because everything that was conveyed to us through state media about foreign countries consisted only of chaos and incompetence. Everywhere the world was bad, only in China was life safe and good. That was not only my opinion but the opinion of most people I knew. It wasn’t until I went abroad that I even realized that elsewhere in the world life can be worth living and other societies have perfectly good capabilities.

Next week, the Olympic Games will once again be held in Beijing. What do you feel today?

I look at these Games with disgust. I would like the whole world to boycott these Games. Once everyone has a better understanding of what exactly is happening in China, and especially in Xinjiang, then perhaps many will regret their participation in these Games later on.

There is indeed a growing awareness in democratic states of the catastrophe in Xinjiang. Last week, the French parliament condemned the human rights crimes there as genocide.

I truly cheered and am so grateful for this signal from the French. Here in Washington, people took to the streets waving French flags.

Germany has a hard time with the term genocide.

I hope that will change. Germany enjoys a very high status among the Uyghurs because we grew up with the quality seal “Made in Germany” in our heads. In our minds, Germany was a perfect country that did everything right.

Volkswagen’s CEO once denied any knowledge about camps in Xinjiang.

Making money is not everything. It comes and goes. At the end of life, the only question that remains is, what have you done for humanity in the world? At some point, Mr. Diess’ conscience will also ask him this question. He should be aware that he represents his country and shapes its image. Many people trust Germany. If he considers good business with China to be more important, that will also shake confidence in his country.

Why did you go public with your story?

I never cared about politics. I have always wondered why people don’t just live in peace. But the Chinese government has done horrible things to my family, my people, and me. They torture and kill us. During my total of three months of imprisonment, nine people died where I was held. Why are they doing this to us? I want an answer to that.

Are you afraid of Chinese revenge?

No, I am ready to die for it because I know I am doing the right thing. They took my child and my family. I lost my hope, my dreams, my health. I felt like I was dead. But my second life told me, take care of your other two children.

Were there any threats against you?

Yes, they threaten to lock up my entire family. My father called me. A voice in the background told him to talk. He told me to report to the Chinese embassy. They would help me there. There were also several incidents after I testified before the US Congress. I was being followed and I received messages. One time my cab was rammed by a stolen vehicle. The other driver took out a gun and pointed it at me. My cab driver put my head down and sped off. I reported all of these incidents to the FBI. That was two years ago now. There hasn’t been a threat since the book was published.

Are there moments when you can be carefree again?

No, I have not experienced that yet. I sometimes wish my doctor could erase my terrible memories so that I could live carefree again.

Do you have plans for the future?

I feel safe in the USA. I hope that my asylum application will be approved soon and I can then stay here with my family for the rest of my life.

The EU has adopted an ambitious climate program, the “European Green Deal”. Its goals are ambitious; by 2030, the EU plans to reduce CO2-equivalent emissions by 55 percent. By 2050, the EU wants to be climate neutral. But the path is complicated: The “Fit-for-55” package of measures is huge, and many measures are causing heated debates. Nevertheless, the majority of the package is still to be adopted in 2022.

Some issues have a major impact on the EU’s trading partners – and thus on China. The biggest issue in this respect is the planned Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The government in Beijing is looking at this project with great concern – also because the Chinese government does not quite know what is in store for its companies. The fear is that the EU’s new rules will increase the cost of importing Chinese goods.

CBAM is to prevent goods from countries with less restrictive emissions regulations and lower CO2 prices from competing with goods produced in Europe, which are more expensive due to a higher CO2 price. This is because more climate-damaging products could thus undercut the prices of their EU competitors. CBAM is thus closely linked to the European Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS), which sets the price of greenhouse gas emissions in Europe. In other words, from a European perspective, if China does not adequately price the CO2 emissions of its companies, then the EU will mark up imports.

In this way, the EU wants to ensure that it can achieve its climate targets without energy-intensive industries moving abroad. This process is known as “carbon leakage.” Companies simply relocate high-emission processes to other parts of the world in order to save money – without helping the climate. However, critics also fear that CBAM could lead to trade conflicts with other countries like China. (Europe.Table reported).

First, a brief explanation: The EU ETS operates according to the cap-and-trade principle. The EU distributes a fixed amount of emission allowances (cap) to companies according to certain criteria. Companies that reduce their emissions more than required can sell the remaining allowances on the market (trade). A price for the emission of CO2 is created. (Europe.Table reported).

The amount of the future CO2 border adjustment is to be based on the CO2 price of the ETS, which European companies have to pay on a weekly average for the acquisition of EU emission allowances. Companies from third countries are to be able to claim CO2 prices that they have to pay in their home country. The CBAM is to enter the pilot phase in 2023 and will be gradually implemented from 2026 to 2035.

In China’s ETS, the CO2 price is currently significantly lower (China.Table reported). There, the authorization to emit one ton of C02 currently costs the equivalent of around eight euros, while this price in the EU is 80 euros per ton. Chinese export companies will therefore probably have to pay a high CO2 tax in the future. And so it is no wonder that Beijing is showing little enthusiasm for CBAM (China.Table reported).

According to a study by Chatham House, China is one of five countries that will be most affected by CBAM. This is because China exports more goods and services to the EU than any other country in the world. In 2020, goods worth €586 billion were traded between China and the EU. That corresponded to 16 percent of the EU’s foreign trade, according to data from the German Federal Statistical Office. By comparison, the US was at 15 percent.

China is threatened with severe impacts, particularly in sectors with above-average emissions, especially in heavy industry. Take iron and steel, for example: China is the second-largest exporter to the EU in this sector, (according to data from 2015-2019). But also the energy-intensive aluminum industry would be strongly affected by a CO2 border adjustment (China.Table reported). As a result, experts expect great resistance from the People’s Republic, especially in these sectors.

But it is still difficult to determine the extent of any impacts, given the feud within the EU over the CBAM draft. “The Chinese side is not only concerned about what the CBAM system looks like in its early stages – but also how it might evolve,” says Lina Li, Senior Manager Carbon Markets and Pricing at environmental and climate consultancy Adelphi. The debate on expanding the scope of CBAM and including indirect emissions is causing particular concern among Chinese stakeholders, Li said. In its CBAM proposal, the EU Commission has named iron and steel, concrete, fertilizer, aluminum, and power generation as industries to be included. But EU Parliament recently proposed to also include organic chemicals, hydrogen, and polymers. (Europe.Table reported)

The financial impact of CBAM on China could thus increase significantly in the future, says Lina Li. According to a study by the Development Research Center of the State Council in Beijing, the EU’s CBAM plans could reduce China’s economic growth by up to 0.64 percentage points. That could cost millions of jobs in manufacturing. CBAM could increase the cost of exports to the EU by three percent, thus reducing exports of manufactured goods to the EU by 13 percent. In addition, if the CO2 price difference between the ETS of the country of origin, say China, and that of the EU ETS is significant, “then the costs for affected companies under the CBAM will grow.” And that is currently the case.

Few countries worry as much as China, according to Li. “We are having discussions with experts from Africa who fear CBAM could hit them hard. But the volumes from Africa are negligible,” Li tells China.Table. The US is also less concerned than China because its production has higher efficiency and lower emissions, she says.

And China’s ETS will not become compatible with the EU ETS, at least in the short term. Corinne Abele, Head of Foreign Trade at GTAI in Shanghai, estimates that the price of CO2 emissions in China will remain well below the price level of the European ETS. Linking the Chinese ETS with other international systems is therefore hardly possible for the time being.

The Chinese ETS also covers significantly fewer industries to date. So far, only a good 2,200 companies from the power sector are involved. However, two industrial sectors are expected to be added this year. According to Lina Li, the aluminum industry could be included as early as this year. Up to seven other sectors are to be added over the next five years:

This puts China in a good position to discuss bilateral agreements with the EU to mitigate impacts from CBAM, Li believes.

In a telephone conversation with former German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron in April 2020, China’s head of state and party Xi Jinping stressed that climate change should not be misused as an instrument for geopolitical negotiations. Representatives of affected industries remember this all too well. So much so, that immediately after the presentation of the EU climate package in summer 2021, the European aluminum industry speculated that China would find ways to undermine the CBAM at any cost. The details of CBAM will still require much negotiation within the EU – and presumably with China.

Olympic gold medalist Georg Hackl sees the Olympic Games in Beijing endangered by the Omicron wave. In an interview with the German Sunday newspaper, Die Welt am Sonntag, the 55-year-old doubted the Games could be held if parts of different teams had to be continuously isolated. He outlined the scenario of a positive test in the team immediately after arrival in Beijing. That would exclude entire teams from participating.

The head of the German snowboard federation, Michael Hölzl, also expects problems arising from the Covid situation in China. In a podcast, he warned that China could “take out” athletes with fake-positive covid tests to keep unwanted competition out of Games. The IOC, meanwhile, defended China’s testing policy. It said it was a legitimate goal to keep Omicron from entering the Olympic bubble.

China’s authorities are also concerned about the development of Covid. All residents of Beijing’s Fengtai district are currently required to undergo Covid tests. In Fengtai, six new Covid infections had been registered, with the infected also showing symptoms. Beijing registered a total of nine cases.

Beijing Games organizers also said on Sunday that they had identified 72 Covid cases among the 2,586 volunteers and staff. Those who tested positive arrived in China between Jan. 4 and Jan. 22. However, no cases occurred among the 171 athletes and officials who entered during that period. The Games begin on February 4th. fin/rtr

The US government will temporarily cancel 44 flights operated by Chinese carriers Air China, China Southern Airlines, China Eastern Airlines, and Xiamen Airlines from the United States to the People’s Republic. This was the US government’s response to the Chinese government’s decision to suspend flights operated by US airlines over covid concerns. The suspensions will begin on Jan. 30 with Xiamen Airlines’ scheduled flight from Los Angeles to Xiamen and continue through March 29, according to the DOT. Since December 31, Chinese authorities have suspended 20 United Airlines, 10 American Airlines and 14 Delta Air Lines flights after some passengers tested positive. rtr

A discussion on how to deal with Taiwan has also started in the Czech Republic. “We have to defend certain values such as freedom, democracy, and the rule of law,” says Nathalie Vogel of the European Values Center for Security Policy (EVC), a Prague-based think tank. Vogel is referring to a change in mood in the country. After the Czech Republic initially moved closer to China in the past decade as part of China’s Eastern Europe Initiative, skepticism is now on the rise. Its position on Taiwan is becoming the focus of debate in the country in the wake of the Lithuania affair.

Ten years ago, China’s leadership wanted to strengthen ties with Central and Eastern Europe through the annual “16 plus 1” format. And for a time, Beijing’s strategy seemed to pay off. All 16 countries were ready for greater economic cooperation. Hungary moved closer to the communist leadership in Beijing. Greece lobbied to be allowed to join the format. Sixteen became seventeen.

But disillusionment has long since set in. Many of the Chinese investment promises have not materialized. Some countries have clashed with China. Lithuania was the first of the 17 European countries to leave this format and is currently engaged in a heated dispute with Beijing over the name of the Taiwanese trade office in Vilnius. A similar dispute has broken out with Slovenia (China.Table reported).

Resentment against Beijing’s aggressive power policy is now also growing in the Czech Republic. “The Chinese people should know that genocide is being committed in their name in Xinjiang,” Vogel said in a video message. The Chinese should also learn “that all hostile activities against individual European states are considered a threat to the EU as a whole.” This would only cause one thing: “greater cohesion toward the People’s Republic.” The fact that a growing number of European states are expressing solidarity with Taiwan is “not the result of any dark forces in the West, but the result of Xi Jinping’s policies.”

Jakob Janda, Executive Director of the EVC, and currently in Taiwan for a research visit, called on analysts, policymakers and security agencies in Europe to learn from the island nation. Taiwan, he said, has had plenty of experience resisting pressure from the communist leadership in Beijing. Europeans could benefit from this experience.

In other news, Taiwan reported on Sunday the most serious violation of its air defense zone by Chinese military aircraft in weeks. 39 aircraft had been ordered not to enter the area, according to the Ministry of National Defense in Taipei. According to the statement, 34 fighter jets, one bomber, and other aircraft had been detected. This was the largest number in a single day since October 2021. Taiwan dispatched fighter jets to warn the Chinese invaders. In addition, missile systems had been deployed to monitor them. No shots had been fired. flee/rtr

The United States-China trade war started in 2018 and has never officially ended. So, which side has been “winning” it? Recent research offers an unambiguous answer: neither. US tariffs on Chinese goods led to higher import prices in the US in the affected product categories, and China’s retaliatory tariffs on US goods ended up hurting Chinese importers. Bilateral trade between the two countries has tanked. And because the US and China are the world’s two largest economies, many regard this development as a harbinger of the end of globalization.

Yet the “deglobalization” argument ignores the many “bystander” countries that were not directly targeted by the US or China. In a new paper investigating the effects of the trade war on these countries, my co-authors and I come to an unexpected conclusion: Many, but not all, of these bystander countries, have benefited from the trade war in the form of higher exports.

To be sure, one would expect exports from third countries (Mexico, Vietnam, Malaysia, etc.) to take the place of Chinese exports to the US. But what is surprising is that these countries increased their exports not only to the US but also to the rest of the world. In fact, global trade in the products affected by the trade war seems to have increased by 3% relative to global trade in the products not targeted by tariffs. That means the trade war did not just lead to reallocation of third-country exports to the US (or China); it also resulted in net trade creation.

Given that trade wars are not generally associated with this outcome, what accounts for it? One potential explanation is that some bystander countries saw the trade war as an opportunity to increase their presence in world markets. By investing in additional trade capacity or mobilizing existing idle capacity, they could increase their exports without increasing their prices.

Another explanation is that as bystander countries started exporting more to the US or China, their unit costs of production declined, because economies of scale allowed them to offer more at lower prices. Consistent with these explanations, our paper finds that the countries with the largest increases in global exports are those in which export prices are declining.

While the net effect of the trade war on the world economy was an increase in trade, there was enormous variation across countries. Some countries increased their exports significantly; some increased their exports to the US at the expense of their exports elsewhere (they reallocated trade); and some countries simply lost exports by selling less to the US and to the rest of the world. What accounts for these differences, and what could countries have done to ensure larger gains from the trade war?

Again, the answers are somewhat surprising. One might have guessed that the most important factor explaining countries’ differing experiences would be pre-trade-war specialization patterns. Countries such as Malaysia and Vietnam, for example, were lucky to be producing a heavily affected product category like machinery. Yet specialization patterns appear to have mattered little, judging by the big export winners of the trade war: South Africa, Turkey, Egypt, Romania, Mexico, Singapore, the Netherlands, Belgium, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic.

What mattered instead were two key country characteristics: participation in “deep” trade agreements (defined as regimes covering not only tariffs but also other measures of behind-the-border protection); and accumulated foreign direct investment. Countries that had a high pre-existing degree of international trade integration benefited the most. Trade agreements tend to reduce the fixed costs of expanding in foreign markets, and existing arrangements may have partly offset the uncertainty generated by the trade war. Similarly, higher FDI is a reliable proxy for greater social, political, and economic ties to foreign markets.

Supply-chain effects also may have played an important role. In a prescient policy briefing based on private conversations with executives at large multinationals, analysts at the Peterson Institute for International Economics predicted in 2016 that US tariffs would “set off a daisy chain of production shifts.”

If a company decided to shift production of a product targeted by Chinese tariffs to a third country, this would necessitate a reshuffling of other activities in the third country, affecting multiple other countries in turn. The exact pattern of these responses would have been hard to predict, given the complexity of modern supply chains. But a country’s degree of international integration appears to have been a decisive factor in a firm’s relocation decisions.

Returning to our initial question, then, the big winner of the trade war seems to be “bystander” countries with deep international ties. From the US perspective, the trade war did not lead to the advertised reshoring of economic activity, at least in the short to medium term. Instead, Chinese imports to the US were simply replaced by imports from other countries.

From the perspective of “bystander” countries, the trade war, ironically, demonstrated the importance of trade integration, especially deep trade agreements and FDI. Fortunately, the Sino-American trade war does not spell the end of globalization. Rather, it may mark the beginning of a new world trading system that no longer has the US or China at its center.

Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg, former Chief Economist of the World Bank Group and editor of the American Economic Review, is a Professor of Economics at Yale University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2022.

www.project-syndicate.org

Shawn Siu will become Executive Director of the troubled real estate group Evergrande. He replaces Lai Lixin. Evergrande is teetering on the brink of insolvency, which is also leading to a staff replacement. Siu comes from the group’s car division.

Webb Ding will become Managing Director of the China subsidiary of Swiss biopharma specialist Oculis on February 1. Oculis is headquartered in Lausanne. Ding has experience at Chinese subsidiaries of Fresenius and Novartis.

Yan Sibo, also known as Steven Yan, will become Managing Director of KHD Beijing, a subsidiary of the concrete group KHD Humboldt Wedag International based in Cologne, Germany. KHD is majority-owned by the Chinese defense group AVIC.

Scripted murder. What sounds like a sinister, bloody deed is actually a new genre in Chinese entertainment that also involves a lot of human interaction. 剧本杀 jùběnshā is the name of the trend in Chinese – made up of the words for “script” (剧本 jùběn) and “kill, murder” (杀 shā).

But at most, only times is getting killed – and in a creative and entertaining way – when young Chinese urbanites meet for a “murder plot“. Jubensha is a kind of enhanced answer to the detective game Cluedo from Great Britain, which already enjoyed great success in the West in the 1990s. In Germany, the classic game, which involves using clues to solve a fictitious murder, was celebrated both on television and as a board game. China has now been expanding the idea into a live role-playing game for several years. There is even a celebrity reality show with the same theme, “Who’s the Murder” (明星大侦探 míngxīng dà zhēntàn), which is going into its seventh season this year.

So business is booming. In metropolises such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Chengdu, new Jubensha experience rooms are popping up all the time, where people can meet to crack criminal cases together. The players gather in real life – a welcome change from the smartphone and computer game world – and run through the game together based on a script. The quality of the script determines the entertainment factor and how deep you ultimately have to dig into your pocket. A round of Jubensha takes two to three hours on average, and the price per head ranges from the equivalent of 10 to 20 euros (for simple plots) to several hundred euros (for particularly elaborate scenarios). The creative scope also varies depending on the script – there are “closed” and “open scripts” (封闭本 fēngbìběn vs. 开放本 kāifàngběn), each with a greater or lesser range of possible storylines.

The most common game variants include: Detective scripts (推理本 tuīlǐběn from 推理 tuīlǐ – “to draw a conclusion”. Task: locate the murderer in the room), team fight scripts (阵营本 zhènyíngběn from 阵营 zhènyíng – “camp, military grouping”. Here, different camps fight each other) or fantasy scripts (变格本 biàngéběn from 变格 biàngé – “change of form; declination”. In this, one may encounter the supernatural or find oneself in a science-fiction scenario). And then there are the adult scripts (小黄本 xiǎohuángběn – literally “little yellow scripts”. As is well known, “yellow” 黄 huáng is synonymous with anything raunchy in China; “yellow” scripts accordingly revolve around “passion, crime and sex”).

For those who also now developed a taste for blood, here are a few more “killer” Chinese vocabulary words (which, on closer inspection, turn out to be less bloodthirsty than they seem):

Verena Menzel runs the language school New Chinese in Beijing.