When it comes to making business in China, we like to revel in nostalgia. Just like we do with the Western world, there is a sort of over-glorification of some distant “good old times”. But when exactly were these “good times?” Times, when the doors to the market opened without any government intervention, when friction with authorities and the public was nonexistent and Western companies could still rely on the rule of law? Hartmut Heine, our interview partner this Monday, tells us what manipulations and contortions were necessary to make a short Transrapid line a reality in Shanghai and how nerve-wracking it really was to do business with China in the past. But every technology has its time. Today, Heine wants to sell the Hyperloop, a modern form of the Maglev train inside a vacuum tube. He explains why it – somewhat paradoxically, has a better chance than conventional technology without a tube.

This example shows that something significant has changed since the first Transrapid line was introduced. “Back then, China had the big market and we had the technology,” says Heine. Today, China is technically on par and would prefer to serve its market itself. “We have to accept that the Chinese have their own ideas and want to implement them.”

The shift in technology is also creating new difficulties for individual mobility. Batteries for electric cars are filled to the brim with harmful chemicals. China is now inevitably taking a pioneering role in recycling: Lots of electric mobility equals lots of old batteries. Nico Beckert compares how the EU and China approach this upcoming problem.

Anyone who currently wants to travel from Europe to China has to face all manners of hoops and restrictions due to Covid. Many expatriates have therefore temporarily returned to their home country. In our new ‘Tools’ section, experts explain how to extend work permits from afar and what pitfalls lurk when it comes to residence permits. In future issues, our new ‘Tools’ section will answer questions regarding law, regulation and market access on a regular basis in China.Table.

I wish you a great and productive week!

Disclaimer: This interview was translated into English and is not considered an official translation by any party involved in the interview.

The Transrapid was already politically buried long ago, it was deemed undesirable. But now there are suddenly talks about the Transrapid 2.0, the Hyperloop, a magnetic levitation train that utilizes a vacuum tunnel to travel up to 800 kilometers per hour. How realistic is this?

It is very realistic. Climate change is forcing the world to reconsider because aircraft consume too much CO2 and the world is growing ever closer together. And with the Hyperloop, there is one key principle: The less air in the tunnel is, the less resistance the train meets, and as a result, less energy is being consumed. You can tell that this technology is once again gaining relevance by the fact that independent research and development is being carried out in the USA, in Europe, at Hardt Hyperloop, and in China, all at the same time. In the meantime, we have solved some of the technological problems that still existed with the Transrapid: Rail switches, for example, are now fully electronic and no longer mechanical. This means that they no longer require costly maintenance. They do not get stuck. This reduces operating costs.

And which nation is currently in the lead?

That is hard to say. What is clear, however, is that the Chinese are under the greatest pressure to act.

When will the first trains run in China?

Politicians already have fixed plans for the trains. A covered distance of 30,000 kilometers by 2060. The question is, how fast is it technologically feasible? It’s crystal-gazing, but I think in ten years these trains will be running in China. I think this timetable is realistic.

Does it make sense for Europeans to cooperate with China on this issue?

By all means. However, the Chinese will no longer just purchase a prototype; instead, they will work with European companies to get the technology ready for production. Nowadays, no country develops such a complex technology on its own. The pressure of climate change is too great for that. But now China is innovative enough to work with others on an equal level.

What is China’s greatest strength?

In addition to innovations power, it is Chinese politics that has the means and the skill to realize such projects – very quickly, if necessary. I can’t think of any country that has a similar capability. That’s why I’m still here. The way the Chinese think and act about the future is very impressive. Beijing sets a specific but ambitious goal: A traveling time from Beijing all the way south to Shenzhen in three and a half hours at 800 kilometers per hour. And then follows the implementation. The money is there. And so is the pressure to act. Many people must somehow get from A to B in an eco-friendly way.

Why should the Chinese cooperate with companies like Hardt?

Because we and other European companies have the know-how that China needs. With us, the train is operable much sooner. China’s companies will be able to meet the Chinese government’s plans more quickly. And we gain a reference project faster, so it’s a win-win situation for everyone. The first rail lines will cover a distance of 300 to 400 kilometers, which is half an hour’s travel time.

Isn’t this also a bit risky? The term technology theft comes to mind.

Nothing is without risk, but the opportunities far outweigh the risks. And where else should we build a facility, if not in China? And again, nowhere in the world, conditions are more favorable.

What about the US under Joe Biden? He is planning gigantic infrastructure projects.

The problem in the US is land. I personally negotiated a Transrapid project in the US. The Los Angeles-Las Vegas line to be exact. It fell through because of the price of land and the time it would take to negotiate the purchase of the land. At some point, it would no longer be profitable.

And in Europe?

In Germany, the main reason was political resistance. The Green party and the red-green government didn’t want this, but climate change is forcing them to reconsider as well. In this respect, signals in Europe are now much more favorable. The first important step will be the reaction of German politicians to the Chinese wish to remodel the old Transrapid test track in Lathen into a Hyperloop test track instead of building a new one. This would save us, the Europeans and the Chinese, a lot of time. Originally, the Chinese wanted to conduct tests in Shanghai on its Transrapid track outside operating hours. However, they were not allowed to do so. But at the same time, the political pressure to test this new technology in everyday operation is massive.

And how are the political signs in Germany?

I am confident that it will work out. But it won’t happen overnight. Germany will soon hold their elections, and then we’ll have to see what happens. Cooperation at EU level would be ideal. I no longer consider it wishful thinking, either. Us Europeans have something to offer. So do the Chinese. In this regard, it makes sense to join forces.

However, the political divide between the EU and China is greater than they have been in the last decades. China and the EU have imposed sanctions on each other. What are the impacts on a project such as this?

A closer look helps: Germany and certainly Chancellor Merkel have not been publicly challenged by the Chinese in this regard yet. I see the potential for negotiation here. In addition, both China and the EU face pressure from their economic sector. Businesses don’t want sanctions. There is a growing realization on both sides that sanctions are a dead end. And where there’s a will, there’s a way.

How did things even get this far?

Today Beijing is no longer putting up with things as it did 20 years ago, it has its own ideas and expresses them clearly and unambiguously. And suddenly there is a systemic competition between the West and China. The fronts are hardening, and we still have to get used to the fact that the Chinese no longer do what we think is right. That is why it was sensible to sign an investment agreement with the Chinese. Different ideas are now being discussed on a constructive and balanced level.

Is the agreement dead?

I do not think so. Despite all the political banter, the trend leans towards more cooperation, not less.

But isn’t it more difficult to cooperate with China today than it was 20 or even 30 years ago?

It is different. It was never easy to do business in China. We like to glorify the past. Back then, the Chinese had a big market, and we had the technology. The problem was technology theft. Today, they already own the technology and that’s why technology is generally better protected, but they also have a lot more pressure stemming from people’s expectations. This means the pressure to be more advanced is far greater. If European companies adapt to this, they can do very good business here. The Hyperloop will be proof of that.

Has the method of cooperation with China changed over the decades?

We have to accept that the Chinese have their own ideas and wish to implement them. We have to adjust to that. But in the end, it’s like anywhere else when it comes to making business. I have worked with Chinese people who were loyal and worked very hard. But there also is another kind of course. Distinguishing one from the other is what day-to-day work is all about. For this, you need cross-cultural competence.

Compared to today, wasn’t it much easier back then when it came to “levitating” the Transrapid?

In the beginning, nobody wanted the Transrapid. Thyssen-Krupp and Siemens had developed the train, but their business interests had changed over the years. Siemens preferred to sell its classic track trains in China, and for Thyssen, it was no longer a core business. That’s why they had already sold the marketing rights for Asia to a Japanese consortium. But they did nothing in China. When the rights were made available again, Eckhard Rohkamm, chairman of the board, whom I hold in high regard, told me: “Yes, you can go for it, but there’s no budget for it.” That’s another way of saying that you should drop the project. Especially since the Chinese were also skeptical because Germany had no route of reference in everyday operation. It wasn’t about cultural differences, for a start.

How did you spin the issue?

I was looking for a Chinese partner in politics who was enthusiastic about the subject. And that’s who I found: It was Zhu Rongji, then still vice-premier. As a trained electrical engineer and former mayor of Shanghai, he could well imagine a line from the airport to the city center. We talked about it time and time again, but it just didn’t come through. It wasn’t until Zhu became premier in 1998 that the negotiations gained momentum. And I knew I had put my money on the right man. Then, suddenly, there was an appointment with the Prime Minister for chairman Rohkamm. We were still skeptical. Would the appointment come about? And if it did, would anything of substance be discussed? Then, the 20-minute appointment lasted two and a half hours, and the prime minister didn’t come alone – he brought all ministers responsible with him. That’s when I knew: Now it’s getting serious.

And your chairman?

He remained skeptical and asked himself, not without good reason, whether we could deliver a marketable product at all. So I helped out a little. I made sure the press heard about the meeting. As a result, Thyssen’s stocks rose by 15 percent. For us, this was a clear signal to act.

And in China?

There, too, Premier Zhu had to fight down opposition from the rail track faction inside the ministry. He then drove to Lathen during a visit to Germany and took the mayor of Shanghai with him. After the demonstration, he publicly asked the mayor: “And? Do you want to buy the train?” He said yes – what else could he do – and the rest is history.

But that was only the first hurdle if I remember correctly.

Yes. Premier Zhu wanted us to finish the production plant while he was still Prime Minister. But that was only for two years. From a German point of view, it was impossible. But we managed to pull it off somehow. We did so with great effort and an enormous willingness to take risks, because we had sold a product in which we basically had no practical experience. For this reason, we had to rely on the Chinese customer turning a blind eye now and then. On December 31, 2002, then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and Premier Zhu officially inaugurated the Transrapid. There was a vase on the table, and it didn’t move at over 400 kilometers per hour. It was proof, that the Transrapid delivered on its promise.

Today, the train shakes a lot more, though.

But this has nothing to do with our technology. It is due to the fact that the rail was built too quickly. It has sunk over time in the marshy terrain.

Would such teamwork still be possible today? More and more German companies are reporting problems with their Chinese partners and politics.

But you also have to ask yourself why they have problems. Are they perhaps not flexible enough themselves? Are they no longer competitive? Can’t they adapt? The reason is not always that the Chinese have become more self-confident or are even outsmarting us. It’s always easier to point fingers. I personally believe that such teamwork is still conceivable today.

But don’t we need more cultural competence nowadays?

Certainly! You have to pay attention to what the Chinese have in mind. Back in the 1980s, when we started building cars or steel mills in China, we determined how it should be done. The Chinese didn’t have a clue back then. But it wasn’t easy to teach them either. Today they are well-educated, have their own experience and have their own ideas. It’s different, but not necessarily harder or easier. It is exciting regardless! That’s why I’m incredibly thrilled about the next big challenge, the Hyperloop. I really want to get it done. And then I’ll take it back a step. For now, anyway.

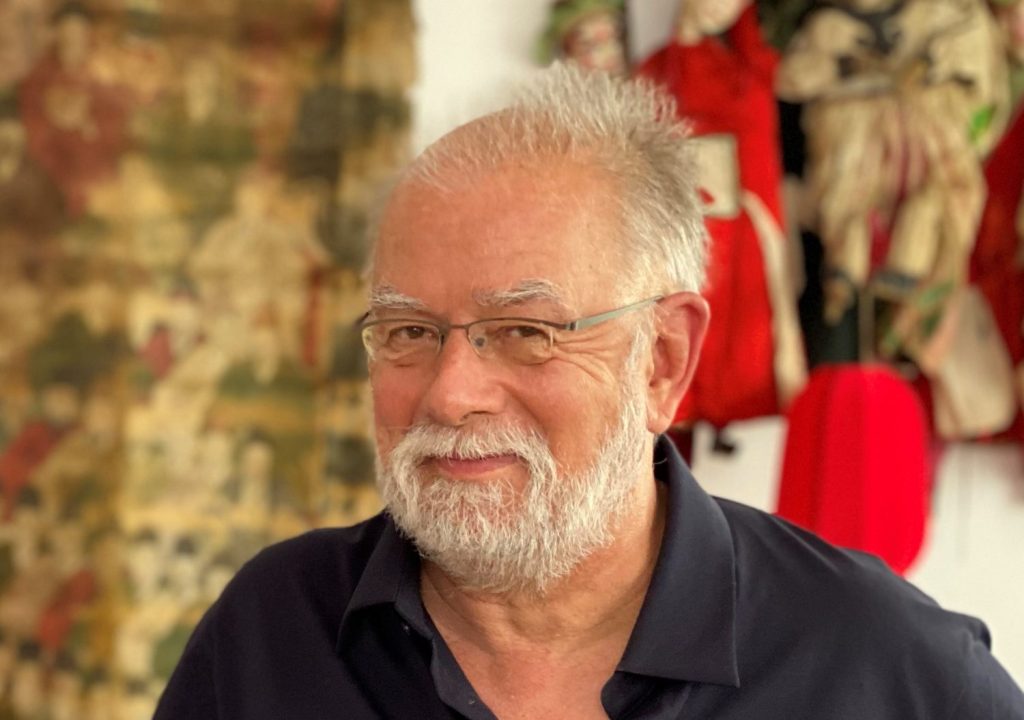

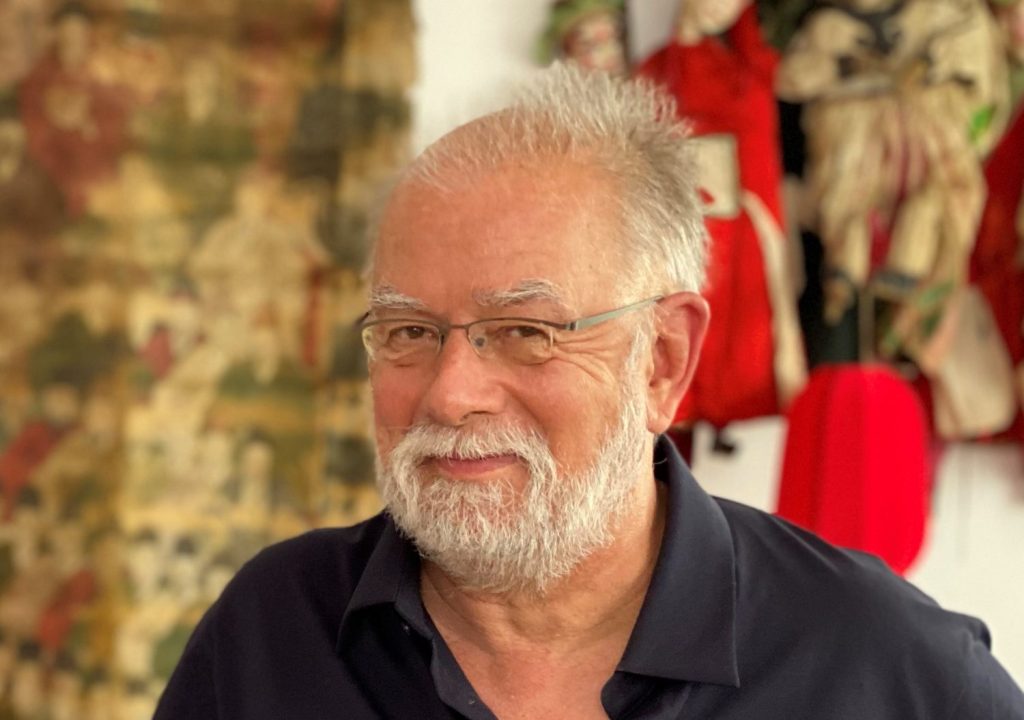

Hartmut Heine, 67, head of ThyssenKrupp China from 1989 to 2004, brought Chinese politics and German industry together at the same table and was in charge of the construction of the Transrapid in Shanghai. He has lived and worked in China for more than 40 years and was under contract at Salzgitter Stahl, Georgsmarienhütte and Siemens, among others. In 1984, he co-founded the German Chamber of Commerce and was a member of the board of the Deutsche Schule for over a decade. Today, he is heading the China department at Dutch Hyperloop manufacturer Hardt.

The boom in electric mobility in recent years will soon result in millions of used EV batteries. The car industry quantifies the service life of batteries to be eight to ten years. After that, the capacity of the storage modules and thus the range of the vehicles will have decreased to such an extent that the batteries will need to be replaced.

What happens to the millions of used EV batteries at the end of their lifecycle? So far, recycling in China is still sketchy at best. Yet these valuable raw materials urgently need to be recycled. The demand for battery raw materials will rise sharply as the demand of electric vehicles booms.

In China, the recycling challenge is urgent. As early as 2025, twelve times more used EV batteries will have to be recycled or put to other uses than in 2020, according to the Chinese Association of Automobile Manufacturers. That is seven times more used EV batteries than will be generated in the EU in the same timeframe.

Currently, many EV batteries in China still do not reach official recycling companies. Instead, they end up in landfills or at companies operating illegally. There, these batteries are recycled with outdated technology and low environmental standards, as Chinese media report. “Recycling systems for EV batteries must be developed more quickly,” China’s Premier Li Keqiang emphasized in a government report for the last People’s Congress in March.

On paper, Chinese regulations on recycling are textbook quality. In 2018 and 2019, the Chinese government issued regulations and guidelines to improve recycling. First, the Automobile- and battery industries were asked to jointly launch recycling pilot projects in 17 cities and regions and to establish “recycling service networks.” In 2018, the responsibility for battery collection, treatment and recycling was transferred to car manufacturers.

At the end of 2019, the government reaffirmed this responsibility of electric vehicle manufacturers and required them to set up “service points for recycling” EV batteries – but this task may also be outsourced to external service providers. These service points are responsible for collecting, storing as well as packaging and shipping of batteries. However, they are not allowed to dismantle the batteries themselves. Only 22 approved recycling companies are responsible.

Battery manufacturers, in turn, must provide information on the proper storage and disposal of batteries. Likewise, they are to coordinate on battery design to standardize recycling. A tracking system should be established to identify discarded batteries.

However, there is a “misalignment between policy rules and actual” recycling, stated Shanghai-based sustainability expert Richard Brubaker in an interview with China.Table. There are still “a number of bottlenecks in the collection and processing of expired EV batteries,” says the founder and managing director of sustainability-focused consultancy Collective Responsibility.

In addition: Battery recycling laws and regulations do have collection quotas. “However, collection practices do not meet these quotas,” Brubaker said. Nor do the guidelines contain regulations on how much of the valuable raw materials must be recovered during recycling. However, Brubaker says, task forces are looking into the introduction of such recovery quotas.

Brubaker sees “exciting developments” regarding the second life of retired EV batteries as energy storage and the collection of batteries for this purpose. However, there are problems here too: For safety reasons, China’s National Energy Administration has proposed a ban on the use of retired EV batteries as energy storage, as reported by business portal Caixin. In April, an explosion occurred at an energy storage facility, killing two firefighters.

The second life of expired batteries in smaller applications – for example in the field of telecommunications – would not be affected by this ban. But there is a lack of information on the condition of retired EV batteries. “Incomplete operational data makes it difficult to assess their safety, lifespan and adaptability,” Caixin quotes an industry official. Richard Brubaker confirms this assessment. Such information, however, is vital to the economic success of companies refurbishing batteries for a second life in storage applications.

The Chinese Communist Party is aware of the problem. In early July, the National Development and Reform Commission adopted the 14th ‘Five-Year Plan’ for the development of a Circular Economy. It states: “There is an urgent need to improve the capacity of high-quality recycling” in China. The establishment of ‘recycling service points’ by car manufacturers should be pushed forward. To prevent EV batteries from being recycled illegally, the overall tracking of batteries should be improved. Authorities announced a crackdown on illegal recyclers. A major part of the plan is a repetition of previous regulations. The plan does not specify any recycling figures.

The EU is already one step further. In December 2020, the EU Commission presented a comprehensive regulatory proposal on the recycling of (electric car) batteries and their second life. The proposal replaces an outdated EU directive from 2006 when lithium batteries did not play a major role. So far, there are no collection or recycling targets for such batteries. The Commission’s proposal aims to make batteries “an actual source for the recovery of valuable raw materials” in the future.

Regarding lithium batteries specifically, such as those used in electric cars, the EU believes there is “still much work to be done”. So far, it is estimated that only ten percent of the lithium contained in batteries is recycled. This quota is to be increased:

A quota for recycled materials of EV batteries is planned for 2030 – for example, four percent recycled lithium and nickel and twelve percent recycled cobalt. By 2035, these quotas will be raised further. In order to make EV batteries more useful as energy storage devices, the EU wants to establish a market for second-life batteries.

Kerstin Meyer of Agora Verkehrswende welcomes the EU Commission’s proposal. Anchoring recycling targets in law is “an important step in keeping more raw materials in the cycle”. The German Association of Waste Management, Water and Raw Materials also has words of praise for the proposals. The minimum input quota of recycled raw materials for new batteries creates “planning and investment security for the development of recycling infrastructure”, a spokesman told China.Table. However, the Commission must speed up the calculation process for recycling and recovery quotas. Only if the manner in which these proposed quotas are to be achieved are clear, the recycling infrastructure can be built in time, the association said.

The VDMA supports “the regulatory objectives for sustainable batteries pursued by the EU at its core”. However, the association also warns of the “danger of considerable additional bureaucracy” for its member companies. The companies face “enormous competitive disadvantages compared to non-European competitors“. Kerstin Meyer, project manager at the department of vehicles and engines, rejects this argument. “The EU should set high standards. International competition must not lead to a ‘race to the bottom‘ when it comes to recycling standards.”

The European Parliament is working on a proposal to reorient the EU’s China strategy. In a report now adopted by the EU Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee, MEPs propose a strategy consisting of a total of six key pillars, including an open dialogue on global challenges, commitment to human rights through economic-political measures and strengthening the EU’s geopolitical significance. In the report, MEPs stress that the ratification process of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) cannot begin until China lifts sanctions against MEPs and EU institutions. The EU Commission is urged to reintroduce investment protection into the CAI – no solution could be found to this issue during CAI negotiations. In addition, the European Parliament is pressing for progress on the investment agreement with Taiwan. At present, however, there are no signals for the official start of corresponding talks.

Overall, the proposals follow already known attempts of the European Parliament. The report is to be voted on in plenary in September. It remains to be seen what the EU Commission and member states will do with it. In October, the relationship with China is the topic at a special EU-internal summit. The last official EU-China strategy dates back to 2019.

The EU Parliament’s strategy proposal calls for a regular human rights dialogue between Brussels and Beijing, as well as the establishment of verifiable benchmarks for China’s progress on human rights. The report also urges that the European External Action Service (EEAS) be given a mandate and the necessary resources to counter Chinese disinformation campaigns with a dedicated StratCom task force for the Far East (as China.Table reported). ari

China’s restrictions on flights by Lufthansa triggers German backlash. The German Foreign Office expressed concerns about the measure taken and announced that it would now block flights by Chinese airlines. China justifies the cancellation of flight connections due to Covid concerns. Currently, in case an airline transports passengers to China, who are tested positive for Covid-19, the airline will be penalized. Chinese authorities prohibit penalized airlines from offering their respective route for a certain period of time. Since February, German airlines Condor and Lufthansa have already been affected by penalties.

According to a media report, the foreign ministry now suspects anti-competitive practices and is taking measures. “According to available information, there are no violations by German airlines against the infection control requirements of the Chinese authorities that could justify the suspension of flights,” the aviation platform Aerotelegraph quotes the foreign ministry. To counter this, Germany is now reciprocally suspending flights by Chinese airlines on the same route where German companies are facing restrictions. Which airlines and routes are affected by this are not specified for the time being. ari

On Friday, the Chinese emissions trading scheme launched (as China.Table reported). After more than a decade of preparation, the first emission rights were bought and sold. The price at the closure of trading was the equivalent of 6,90 euros per tonne of CO2. In European emissions trading, one tonne of CO2 now costs more than 50 euros.

A total of 2,162 companies from the energy and heating sector are participating in the first phase of China’s emissions trading scheme, as Chinese Environment Minister Huang Runqiu announced at the start of trading. Accordingly, this sector produces 4,5 gigatonnes of CO2 per year, which accounts for a good 40 percent of China’s total emissions. EU Climate Commissioner Frans Timmermanns congratulated China on the start of trading on Twitter.

Originally, Beijing had very ambitious targets for its emissions trade. However, these goals have been softened. Industrial sectors or air traffic do not have to participate in trading for the time being. There are also no fixed or even decreasing upper limits of CO2 certificates, as is the case with European emissions trading. Experts doubt whether trading in its current form can make any significant contribution at all to reducing China’s immense emissions. At the same time, there are still plans to extend emissions trading to other sectors. nib

The World Health Organization (WHO) has announced a new permanent task force to investigate and trace the origin of the Coronavirus. On Friday in Geneva, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus emphasized on inspecting the laboratories in Wuhan, China together with the examination of wildlife and animal markets. The WHO team, which was only allowed to travel to China in January after months of discussions, reported in late March that it was “likely to very likely” that the virus had transmitted from an animal to humans via an intermediate host. That the virus accidentally escaped from a lab and spread is also considered an “extremely unlikely pathway” (China.Table reported).

The U.S., however, addresses the hypothesis about the laboratory as an accident. It is viewed as a possibility at least in parts of the U.S. intelligence apparatus, says U.S. President Joe Biden in late May, while also ordering further testing. The intelligence service is to report at the end of August. Health Minister Jens Spahn had also recently called for further investigations into the origin of the virus. ari

TSMC, the Taiwanese global chip market leader, is concretizing its expansion plans. By 2023, 40,000 wafers per month are to be produced in their Chinese factory located in Nanjing. This corresponds to a capacity expansion of 60 percent. TSMC plans to invest 2.8 billion US dollars, as the company announced some time ago. The Nanjing plant will produce technologically less sophisticated 28-nanometer chips, which are nevertheless highly relevant to the automobile industry. TSMC has stated that the global shortage of automotive chips will be “significantly reduced” by this quarter, as business portal Caixin reported.

According to media reports, TSMC could also be planning a billion-dollar investment in Dresden. Accordingly, talks are being held about the potential construction of a chip factory near the Saxon capital. However, neither Dresden nor TSMC have confirmed these plans so far. The company is already advancing in the US: A factory planned in Arizona is expected to begin mass production in the first quarter of 2024. TSMC plans to invest a total of 12 billion US dollars in the US. TSMC is also pursuing plans to build its first chip factory in Japan. nib

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent travel bans, many expatriates who had returned to their home countries have been restricted from re-entering China. Therefore, renewing the Chinese work permits has become a complicated matter for those stranded.

Although the Chinese government has issued a temporary policy allowing foreigners to renew their work permits remotely, the process has not been completely resolved. There could certainly be difficulties in renewing foreigners’ residence permits and the expiration of the same around this time may only impede the second renewal of their work permits.

Moreover, in July, some local governments appear to have tightened rules on work permit applications with an eye to prevent people from setting up shell companies solely for visa purposes.

To help expatriates stranded overseas to renew their Chinese work permit, many local foreign offices have released a temporary policy. For example, on Feb 1, the Shanghai Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs has announced to introduce the implementation of the “no-visit” examination and approval for all matters related to the work permit for foreigners in Shanghai.

According to the policy, applicants for renewal of work permits are no longer required to bring the original application documents to the local foreign affairs office in China, but could renew them remotely by giving an undertaking on the authenticity of the documents.

The above policy has greatly assisted the process for foreigners’ work permit renewal; however, some issues have not been fully addressed.

Since there has been no policy update on residence permit renewal, foreigners still need to be present in China and provide their entry records for the renewal. In fact, a large number of foreigners got their work permits renewed, but, with the expired residence permits.

Things may become more complicated after 12 months when the work permit is needed to be renewed again. As there is still no change on rules regarding residence permit renewal, those who were unable to renew their residence permit last year, may not be able to renew their residence permit this year, either.

However, because a valid resident permit is one of the primary requirements for the renewal of a work permit, without a valid residence permit, expatriates stranded outside China may not be able to renew their work permits anymore.

Upon Dezan Shira’s confirmation with the Shenzhen foreign affair office staff, here are some solutions:

Applicants can reapply for the work permit as their first-time application, when they want to reenter China.

In this case, we suggest that you make the following preparations beforehand:

On top of the worrisome news, in July, the Guangdong province foreign affair office appears to have tightened rules on work permit application. This can be a big hurdle for start-up companies, since obtaining a work permit is often the first step towards sending employees to China.

Some first-time work permit applicants are now requested to provide additional documents that were never requested before, including (for your very general reference):

From our perspective, the purpose of tightening the rules on work permit applications is to ensure that applicants have a genuine need to work in China, and not otherwise. This is because during the pandemic, some foreigners set up companies in China, most likely, only for obtaining a work visa.

From our recent experience, it emerges that a company’s legal representative needs fewer supporting documents to receive the approval when compared to the other executive positions.

Why? Because the legal representative of a Chinese company will need to be present physically for some company-related procedures, like going to the bank for basic bank account setup, setting up a company tax account at the tax bureau, and completing the real-name authentication test.

However, the legal representative now needs to sign a labor contract, instead of simply uploading a business license. Additionally, the legal representative must have a job title in the company.

You should prepare more documents in advance to support the application, if you are not the legal representatives of the Chinese company.

In the recent work permit system feedback we received from the Guangzhou SAFEA, companies hiring foreigners must have made or are expected to make a written commitment on hiring Chinese employees, otherwise their foreign employees’ work permits may not be renewed or the applications won’t be processed.

This is also a way to ensure the company is operational (rather than a shell firm set up for visa purposes). If the company is obligated to hire Chinese employees, but, still has not done so, the work permit renewal could then also be rejected.

Shenzhen’s Safea seems to be following suit, urging companies to hire Chinese employees. For one-person companies established for visa purposes only, the renewal application could be a real challenge under the current circumstances.

This article first appeared in Asia Briefing, published by Dezan Shira Associates. The company advises international investors in Asia and has offices in China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore, Russia and Vietnam. Please contact them via info@dezanshira.com or their website www.dezanshira.com.

Shang Yanchun and Lu Man have left China’s sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corporation. Shang Yanchun headed one of two investment teams: the departments of technology, media and communications. Lu Man was a senior manager in the department of direct investment. According to Bloomberg, the fund is facing an “exodus of senior executives.” In the past five years, 20 team leaders and managing directors left the sovereign wealth fund.

What activities do you hate to be disturbed in? Maybe while “eat-ing” (吃饭ing – chīfàn-ing), “read-ing” (看书ing – kànshū-ing) or maybe while “rest-ing” (休息ing – xiūxi-ing)? When China’s “Generation Online” immerses itself completely in the moment, language and grammar boundaries become irrelevant. Chinese also has its own progressive form (吃饭 chīfàn = “to eat”, 正在吃饭 zhèngzài chīfàn = “to eat”/”to be eating”). But in Chinese Internet lingo, the English “ing” form has gained a certain “coolness”. China’s young Internet community – which is still familiar enough with the English suffix from grammar lessons in school – is now using the word suffix creatively, adding it not only to Chinese verbs but also to nouns for example and thus creating all kinds of new word creations.

These range from “amusement-ing” (娱乐ing – yúlè-ing) to “application-ing” (招聘ing – zhāopìn-ing) and “television-ing” (看电视ing – kàn diànshì-ing). Common to all forms is that they emphasize the progressive character of the action – by “ing”-in’, one is mentally and emotionally completely involved and enjoys the moment.

Incidentally, if you believe that a tonal language like Chinese is not suitable for anglicisms, then a conversation with today’s Chinese will prove you wrong fairly quickly. Thanks to influences by the Internet, the international working environment and the impactful entertainment industry, which likes to absorb foreign trends, Chinese people like to use English terms in everyday conversation without any warning.

China’s up-and-coming office workers (白领 báilǐng) paved the way by replacing many Chinese terms in their “office speak” with English placeholders, e.g. (我把link和proposal的PPT发到你的email, ok吗?) in the face of global corporate structures and communication channels. Today, it is not uncommon for anglicisms to find their way into everyday Chinese usage via a variety of nationally successful entertainment shows. Hip-hop and street dance formats, for example, made terms like “battle,” “diss,” “pick” and “freestyle” permanent vocabulary used in everyday life – even beyond the shows’ audiences. The Chinese language is ever-changing. A good reason to keep on learning – or in other words, keep on “xuéxí-ing”.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.

When it comes to making business in China, we like to revel in nostalgia. Just like we do with the Western world, there is a sort of over-glorification of some distant “good old times”. But when exactly were these “good times?” Times, when the doors to the market opened without any government intervention, when friction with authorities and the public was nonexistent and Western companies could still rely on the rule of law? Hartmut Heine, our interview partner this Monday, tells us what manipulations and contortions were necessary to make a short Transrapid line a reality in Shanghai and how nerve-wracking it really was to do business with China in the past. But every technology has its time. Today, Heine wants to sell the Hyperloop, a modern form of the Maglev train inside a vacuum tube. He explains why it – somewhat paradoxically, has a better chance than conventional technology without a tube.

This example shows that something significant has changed since the first Transrapid line was introduced. “Back then, China had the big market and we had the technology,” says Heine. Today, China is technically on par and would prefer to serve its market itself. “We have to accept that the Chinese have their own ideas and want to implement them.”

The shift in technology is also creating new difficulties for individual mobility. Batteries for electric cars are filled to the brim with harmful chemicals. China is now inevitably taking a pioneering role in recycling: Lots of electric mobility equals lots of old batteries. Nico Beckert compares how the EU and China approach this upcoming problem.

Anyone who currently wants to travel from Europe to China has to face all manners of hoops and restrictions due to Covid. Many expatriates have therefore temporarily returned to their home country. In our new ‘Tools’ section, experts explain how to extend work permits from afar and what pitfalls lurk when it comes to residence permits. In future issues, our new ‘Tools’ section will answer questions regarding law, regulation and market access on a regular basis in China.Table.

I wish you a great and productive week!

Disclaimer: This interview was translated into English and is not considered an official translation by any party involved in the interview.

The Transrapid was already politically buried long ago, it was deemed undesirable. But now there are suddenly talks about the Transrapid 2.0, the Hyperloop, a magnetic levitation train that utilizes a vacuum tunnel to travel up to 800 kilometers per hour. How realistic is this?

It is very realistic. Climate change is forcing the world to reconsider because aircraft consume too much CO2 and the world is growing ever closer together. And with the Hyperloop, there is one key principle: The less air in the tunnel is, the less resistance the train meets, and as a result, less energy is being consumed. You can tell that this technology is once again gaining relevance by the fact that independent research and development is being carried out in the USA, in Europe, at Hardt Hyperloop, and in China, all at the same time. In the meantime, we have solved some of the technological problems that still existed with the Transrapid: Rail switches, for example, are now fully electronic and no longer mechanical. This means that they no longer require costly maintenance. They do not get stuck. This reduces operating costs.

And which nation is currently in the lead?

That is hard to say. What is clear, however, is that the Chinese are under the greatest pressure to act.

When will the first trains run in China?

Politicians already have fixed plans for the trains. A covered distance of 30,000 kilometers by 2060. The question is, how fast is it technologically feasible? It’s crystal-gazing, but I think in ten years these trains will be running in China. I think this timetable is realistic.

Does it make sense for Europeans to cooperate with China on this issue?

By all means. However, the Chinese will no longer just purchase a prototype; instead, they will work with European companies to get the technology ready for production. Nowadays, no country develops such a complex technology on its own. The pressure of climate change is too great for that. But now China is innovative enough to work with others on an equal level.

What is China’s greatest strength?

In addition to innovations power, it is Chinese politics that has the means and the skill to realize such projects – very quickly, if necessary. I can’t think of any country that has a similar capability. That’s why I’m still here. The way the Chinese think and act about the future is very impressive. Beijing sets a specific but ambitious goal: A traveling time from Beijing all the way south to Shenzhen in three and a half hours at 800 kilometers per hour. And then follows the implementation. The money is there. And so is the pressure to act. Many people must somehow get from A to B in an eco-friendly way.

Why should the Chinese cooperate with companies like Hardt?

Because we and other European companies have the know-how that China needs. With us, the train is operable much sooner. China’s companies will be able to meet the Chinese government’s plans more quickly. And we gain a reference project faster, so it’s a win-win situation for everyone. The first rail lines will cover a distance of 300 to 400 kilometers, which is half an hour’s travel time.

Isn’t this also a bit risky? The term technology theft comes to mind.

Nothing is without risk, but the opportunities far outweigh the risks. And where else should we build a facility, if not in China? And again, nowhere in the world, conditions are more favorable.

What about the US under Joe Biden? He is planning gigantic infrastructure projects.

The problem in the US is land. I personally negotiated a Transrapid project in the US. The Los Angeles-Las Vegas line to be exact. It fell through because of the price of land and the time it would take to negotiate the purchase of the land. At some point, it would no longer be profitable.

And in Europe?

In Germany, the main reason was political resistance. The Green party and the red-green government didn’t want this, but climate change is forcing them to reconsider as well. In this respect, signals in Europe are now much more favorable. The first important step will be the reaction of German politicians to the Chinese wish to remodel the old Transrapid test track in Lathen into a Hyperloop test track instead of building a new one. This would save us, the Europeans and the Chinese, a lot of time. Originally, the Chinese wanted to conduct tests in Shanghai on its Transrapid track outside operating hours. However, they were not allowed to do so. But at the same time, the political pressure to test this new technology in everyday operation is massive.

And how are the political signs in Germany?

I am confident that it will work out. But it won’t happen overnight. Germany will soon hold their elections, and then we’ll have to see what happens. Cooperation at EU level would be ideal. I no longer consider it wishful thinking, either. Us Europeans have something to offer. So do the Chinese. In this regard, it makes sense to join forces.

However, the political divide between the EU and China is greater than they have been in the last decades. China and the EU have imposed sanctions on each other. What are the impacts on a project such as this?

A closer look helps: Germany and certainly Chancellor Merkel have not been publicly challenged by the Chinese in this regard yet. I see the potential for negotiation here. In addition, both China and the EU face pressure from their economic sector. Businesses don’t want sanctions. There is a growing realization on both sides that sanctions are a dead end. And where there’s a will, there’s a way.

How did things even get this far?

Today Beijing is no longer putting up with things as it did 20 years ago, it has its own ideas and expresses them clearly and unambiguously. And suddenly there is a systemic competition between the West and China. The fronts are hardening, and we still have to get used to the fact that the Chinese no longer do what we think is right. That is why it was sensible to sign an investment agreement with the Chinese. Different ideas are now being discussed on a constructive and balanced level.

Is the agreement dead?

I do not think so. Despite all the political banter, the trend leans towards more cooperation, not less.

But isn’t it more difficult to cooperate with China today than it was 20 or even 30 years ago?

It is different. It was never easy to do business in China. We like to glorify the past. Back then, the Chinese had a big market, and we had the technology. The problem was technology theft. Today, they already own the technology and that’s why technology is generally better protected, but they also have a lot more pressure stemming from people’s expectations. This means the pressure to be more advanced is far greater. If European companies adapt to this, they can do very good business here. The Hyperloop will be proof of that.

Has the method of cooperation with China changed over the decades?

We have to accept that the Chinese have their own ideas and wish to implement them. We have to adjust to that. But in the end, it’s like anywhere else when it comes to making business. I have worked with Chinese people who were loyal and worked very hard. But there also is another kind of course. Distinguishing one from the other is what day-to-day work is all about. For this, you need cross-cultural competence.

Compared to today, wasn’t it much easier back then when it came to “levitating” the Transrapid?

In the beginning, nobody wanted the Transrapid. Thyssen-Krupp and Siemens had developed the train, but their business interests had changed over the years. Siemens preferred to sell its classic track trains in China, and for Thyssen, it was no longer a core business. That’s why they had already sold the marketing rights for Asia to a Japanese consortium. But they did nothing in China. When the rights were made available again, Eckhard Rohkamm, chairman of the board, whom I hold in high regard, told me: “Yes, you can go for it, but there’s no budget for it.” That’s another way of saying that you should drop the project. Especially since the Chinese were also skeptical because Germany had no route of reference in everyday operation. It wasn’t about cultural differences, for a start.

How did you spin the issue?

I was looking for a Chinese partner in politics who was enthusiastic about the subject. And that’s who I found: It was Zhu Rongji, then still vice-premier. As a trained electrical engineer and former mayor of Shanghai, he could well imagine a line from the airport to the city center. We talked about it time and time again, but it just didn’t come through. It wasn’t until Zhu became premier in 1998 that the negotiations gained momentum. And I knew I had put my money on the right man. Then, suddenly, there was an appointment with the Prime Minister for chairman Rohkamm. We were still skeptical. Would the appointment come about? And if it did, would anything of substance be discussed? Then, the 20-minute appointment lasted two and a half hours, and the prime minister didn’t come alone – he brought all ministers responsible with him. That’s when I knew: Now it’s getting serious.

And your chairman?

He remained skeptical and asked himself, not without good reason, whether we could deliver a marketable product at all. So I helped out a little. I made sure the press heard about the meeting. As a result, Thyssen’s stocks rose by 15 percent. For us, this was a clear signal to act.

And in China?

There, too, Premier Zhu had to fight down opposition from the rail track faction inside the ministry. He then drove to Lathen during a visit to Germany and took the mayor of Shanghai with him. After the demonstration, he publicly asked the mayor: “And? Do you want to buy the train?” He said yes – what else could he do – and the rest is history.

But that was only the first hurdle if I remember correctly.

Yes. Premier Zhu wanted us to finish the production plant while he was still Prime Minister. But that was only for two years. From a German point of view, it was impossible. But we managed to pull it off somehow. We did so with great effort and an enormous willingness to take risks, because we had sold a product in which we basically had no practical experience. For this reason, we had to rely on the Chinese customer turning a blind eye now and then. On December 31, 2002, then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and Premier Zhu officially inaugurated the Transrapid. There was a vase on the table, and it didn’t move at over 400 kilometers per hour. It was proof, that the Transrapid delivered on its promise.

Today, the train shakes a lot more, though.

But this has nothing to do with our technology. It is due to the fact that the rail was built too quickly. It has sunk over time in the marshy terrain.

Would such teamwork still be possible today? More and more German companies are reporting problems with their Chinese partners and politics.

But you also have to ask yourself why they have problems. Are they perhaps not flexible enough themselves? Are they no longer competitive? Can’t they adapt? The reason is not always that the Chinese have become more self-confident or are even outsmarting us. It’s always easier to point fingers. I personally believe that such teamwork is still conceivable today.

But don’t we need more cultural competence nowadays?

Certainly! You have to pay attention to what the Chinese have in mind. Back in the 1980s, when we started building cars or steel mills in China, we determined how it should be done. The Chinese didn’t have a clue back then. But it wasn’t easy to teach them either. Today they are well-educated, have their own experience and have their own ideas. It’s different, but not necessarily harder or easier. It is exciting regardless! That’s why I’m incredibly thrilled about the next big challenge, the Hyperloop. I really want to get it done. And then I’ll take it back a step. For now, anyway.

Hartmut Heine, 67, head of ThyssenKrupp China from 1989 to 2004, brought Chinese politics and German industry together at the same table and was in charge of the construction of the Transrapid in Shanghai. He has lived and worked in China for more than 40 years and was under contract at Salzgitter Stahl, Georgsmarienhütte and Siemens, among others. In 1984, he co-founded the German Chamber of Commerce and was a member of the board of the Deutsche Schule for over a decade. Today, he is heading the China department at Dutch Hyperloop manufacturer Hardt.

The boom in electric mobility in recent years will soon result in millions of used EV batteries. The car industry quantifies the service life of batteries to be eight to ten years. After that, the capacity of the storage modules and thus the range of the vehicles will have decreased to such an extent that the batteries will need to be replaced.

What happens to the millions of used EV batteries at the end of their lifecycle? So far, recycling in China is still sketchy at best. Yet these valuable raw materials urgently need to be recycled. The demand for battery raw materials will rise sharply as the demand of electric vehicles booms.

In China, the recycling challenge is urgent. As early as 2025, twelve times more used EV batteries will have to be recycled or put to other uses than in 2020, according to the Chinese Association of Automobile Manufacturers. That is seven times more used EV batteries than will be generated in the EU in the same timeframe.

Currently, many EV batteries in China still do not reach official recycling companies. Instead, they end up in landfills or at companies operating illegally. There, these batteries are recycled with outdated technology and low environmental standards, as Chinese media report. “Recycling systems for EV batteries must be developed more quickly,” China’s Premier Li Keqiang emphasized in a government report for the last People’s Congress in March.

On paper, Chinese regulations on recycling are textbook quality. In 2018 and 2019, the Chinese government issued regulations and guidelines to improve recycling. First, the Automobile- and battery industries were asked to jointly launch recycling pilot projects in 17 cities and regions and to establish “recycling service networks.” In 2018, the responsibility for battery collection, treatment and recycling was transferred to car manufacturers.

At the end of 2019, the government reaffirmed this responsibility of electric vehicle manufacturers and required them to set up “service points for recycling” EV batteries – but this task may also be outsourced to external service providers. These service points are responsible for collecting, storing as well as packaging and shipping of batteries. However, they are not allowed to dismantle the batteries themselves. Only 22 approved recycling companies are responsible.

Battery manufacturers, in turn, must provide information on the proper storage and disposal of batteries. Likewise, they are to coordinate on battery design to standardize recycling. A tracking system should be established to identify discarded batteries.

However, there is a “misalignment between policy rules and actual” recycling, stated Shanghai-based sustainability expert Richard Brubaker in an interview with China.Table. There are still “a number of bottlenecks in the collection and processing of expired EV batteries,” says the founder and managing director of sustainability-focused consultancy Collective Responsibility.

In addition: Battery recycling laws and regulations do have collection quotas. “However, collection practices do not meet these quotas,” Brubaker said. Nor do the guidelines contain regulations on how much of the valuable raw materials must be recovered during recycling. However, Brubaker says, task forces are looking into the introduction of such recovery quotas.

Brubaker sees “exciting developments” regarding the second life of retired EV batteries as energy storage and the collection of batteries for this purpose. However, there are problems here too: For safety reasons, China’s National Energy Administration has proposed a ban on the use of retired EV batteries as energy storage, as reported by business portal Caixin. In April, an explosion occurred at an energy storage facility, killing two firefighters.

The second life of expired batteries in smaller applications – for example in the field of telecommunications – would not be affected by this ban. But there is a lack of information on the condition of retired EV batteries. “Incomplete operational data makes it difficult to assess their safety, lifespan and adaptability,” Caixin quotes an industry official. Richard Brubaker confirms this assessment. Such information, however, is vital to the economic success of companies refurbishing batteries for a second life in storage applications.

The Chinese Communist Party is aware of the problem. In early July, the National Development and Reform Commission adopted the 14th ‘Five-Year Plan’ for the development of a Circular Economy. It states: “There is an urgent need to improve the capacity of high-quality recycling” in China. The establishment of ‘recycling service points’ by car manufacturers should be pushed forward. To prevent EV batteries from being recycled illegally, the overall tracking of batteries should be improved. Authorities announced a crackdown on illegal recyclers. A major part of the plan is a repetition of previous regulations. The plan does not specify any recycling figures.

The EU is already one step further. In December 2020, the EU Commission presented a comprehensive regulatory proposal on the recycling of (electric car) batteries and their second life. The proposal replaces an outdated EU directive from 2006 when lithium batteries did not play a major role. So far, there are no collection or recycling targets for such batteries. The Commission’s proposal aims to make batteries “an actual source for the recovery of valuable raw materials” in the future.

Regarding lithium batteries specifically, such as those used in electric cars, the EU believes there is “still much work to be done”. So far, it is estimated that only ten percent of the lithium contained in batteries is recycled. This quota is to be increased:

A quota for recycled materials of EV batteries is planned for 2030 – for example, four percent recycled lithium and nickel and twelve percent recycled cobalt. By 2035, these quotas will be raised further. In order to make EV batteries more useful as energy storage devices, the EU wants to establish a market for second-life batteries.

Kerstin Meyer of Agora Verkehrswende welcomes the EU Commission’s proposal. Anchoring recycling targets in law is “an important step in keeping more raw materials in the cycle”. The German Association of Waste Management, Water and Raw Materials also has words of praise for the proposals. The minimum input quota of recycled raw materials for new batteries creates “planning and investment security for the development of recycling infrastructure”, a spokesman told China.Table. However, the Commission must speed up the calculation process for recycling and recovery quotas. Only if the manner in which these proposed quotas are to be achieved are clear, the recycling infrastructure can be built in time, the association said.

The VDMA supports “the regulatory objectives for sustainable batteries pursued by the EU at its core”. However, the association also warns of the “danger of considerable additional bureaucracy” for its member companies. The companies face “enormous competitive disadvantages compared to non-European competitors“. Kerstin Meyer, project manager at the department of vehicles and engines, rejects this argument. “The EU should set high standards. International competition must not lead to a ‘race to the bottom‘ when it comes to recycling standards.”

The European Parliament is working on a proposal to reorient the EU’s China strategy. In a report now adopted by the EU Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee, MEPs propose a strategy consisting of a total of six key pillars, including an open dialogue on global challenges, commitment to human rights through economic-political measures and strengthening the EU’s geopolitical significance. In the report, MEPs stress that the ratification process of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) cannot begin until China lifts sanctions against MEPs and EU institutions. The EU Commission is urged to reintroduce investment protection into the CAI – no solution could be found to this issue during CAI negotiations. In addition, the European Parliament is pressing for progress on the investment agreement with Taiwan. At present, however, there are no signals for the official start of corresponding talks.

Overall, the proposals follow already known attempts of the European Parliament. The report is to be voted on in plenary in September. It remains to be seen what the EU Commission and member states will do with it. In October, the relationship with China is the topic at a special EU-internal summit. The last official EU-China strategy dates back to 2019.

The EU Parliament’s strategy proposal calls for a regular human rights dialogue between Brussels and Beijing, as well as the establishment of verifiable benchmarks for China’s progress on human rights. The report also urges that the European External Action Service (EEAS) be given a mandate and the necessary resources to counter Chinese disinformation campaigns with a dedicated StratCom task force for the Far East (as China.Table reported). ari

China’s restrictions on flights by Lufthansa triggers German backlash. The German Foreign Office expressed concerns about the measure taken and announced that it would now block flights by Chinese airlines. China justifies the cancellation of flight connections due to Covid concerns. Currently, in case an airline transports passengers to China, who are tested positive for Covid-19, the airline will be penalized. Chinese authorities prohibit penalized airlines from offering their respective route for a certain period of time. Since February, German airlines Condor and Lufthansa have already been affected by penalties.

According to a media report, the foreign ministry now suspects anti-competitive practices and is taking measures. “According to available information, there are no violations by German airlines against the infection control requirements of the Chinese authorities that could justify the suspension of flights,” the aviation platform Aerotelegraph quotes the foreign ministry. To counter this, Germany is now reciprocally suspending flights by Chinese airlines on the same route where German companies are facing restrictions. Which airlines and routes are affected by this are not specified for the time being. ari

On Friday, the Chinese emissions trading scheme launched (as China.Table reported). After more than a decade of preparation, the first emission rights were bought and sold. The price at the closure of trading was the equivalent of 6,90 euros per tonne of CO2. In European emissions trading, one tonne of CO2 now costs more than 50 euros.

A total of 2,162 companies from the energy and heating sector are participating in the first phase of China’s emissions trading scheme, as Chinese Environment Minister Huang Runqiu announced at the start of trading. Accordingly, this sector produces 4,5 gigatonnes of CO2 per year, which accounts for a good 40 percent of China’s total emissions. EU Climate Commissioner Frans Timmermanns congratulated China on the start of trading on Twitter.

Originally, Beijing had very ambitious targets for its emissions trade. However, these goals have been softened. Industrial sectors or air traffic do not have to participate in trading for the time being. There are also no fixed or even decreasing upper limits of CO2 certificates, as is the case with European emissions trading. Experts doubt whether trading in its current form can make any significant contribution at all to reducing China’s immense emissions. At the same time, there are still plans to extend emissions trading to other sectors. nib

The World Health Organization (WHO) has announced a new permanent task force to investigate and trace the origin of the Coronavirus. On Friday in Geneva, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus emphasized on inspecting the laboratories in Wuhan, China together with the examination of wildlife and animal markets. The WHO team, which was only allowed to travel to China in January after months of discussions, reported in late March that it was “likely to very likely” that the virus had transmitted from an animal to humans via an intermediate host. That the virus accidentally escaped from a lab and spread is also considered an “extremely unlikely pathway” (China.Table reported).

The U.S., however, addresses the hypothesis about the laboratory as an accident. It is viewed as a possibility at least in parts of the U.S. intelligence apparatus, says U.S. President Joe Biden in late May, while also ordering further testing. The intelligence service is to report at the end of August. Health Minister Jens Spahn had also recently called for further investigations into the origin of the virus. ari

TSMC, the Taiwanese global chip market leader, is concretizing its expansion plans. By 2023, 40,000 wafers per month are to be produced in their Chinese factory located in Nanjing. This corresponds to a capacity expansion of 60 percent. TSMC plans to invest 2.8 billion US dollars, as the company announced some time ago. The Nanjing plant will produce technologically less sophisticated 28-nanometer chips, which are nevertheless highly relevant to the automobile industry. TSMC has stated that the global shortage of automotive chips will be “significantly reduced” by this quarter, as business portal Caixin reported.

According to media reports, TSMC could also be planning a billion-dollar investment in Dresden. Accordingly, talks are being held about the potential construction of a chip factory near the Saxon capital. However, neither Dresden nor TSMC have confirmed these plans so far. The company is already advancing in the US: A factory planned in Arizona is expected to begin mass production in the first quarter of 2024. TSMC plans to invest a total of 12 billion US dollars in the US. TSMC is also pursuing plans to build its first chip factory in Japan. nib

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent travel bans, many expatriates who had returned to their home countries have been restricted from re-entering China. Therefore, renewing the Chinese work permits has become a complicated matter for those stranded.

Although the Chinese government has issued a temporary policy allowing foreigners to renew their work permits remotely, the process has not been completely resolved. There could certainly be difficulties in renewing foreigners’ residence permits and the expiration of the same around this time may only impede the second renewal of their work permits.

Moreover, in July, some local governments appear to have tightened rules on work permit applications with an eye to prevent people from setting up shell companies solely for visa purposes.

To help expatriates stranded overseas to renew their Chinese work permit, many local foreign offices have released a temporary policy. For example, on Feb 1, the Shanghai Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs has announced to introduce the implementation of the “no-visit” examination and approval for all matters related to the work permit for foreigners in Shanghai.

According to the policy, applicants for renewal of work permits are no longer required to bring the original application documents to the local foreign affairs office in China, but could renew them remotely by giving an undertaking on the authenticity of the documents.

The above policy has greatly assisted the process for foreigners’ work permit renewal; however, some issues have not been fully addressed.

Since there has been no policy update on residence permit renewal, foreigners still need to be present in China and provide their entry records for the renewal. In fact, a large number of foreigners got their work permits renewed, but, with the expired residence permits.

Things may become more complicated after 12 months when the work permit is needed to be renewed again. As there is still no change on rules regarding residence permit renewal, those who were unable to renew their residence permit last year, may not be able to renew their residence permit this year, either.

However, because a valid resident permit is one of the primary requirements for the renewal of a work permit, without a valid residence permit, expatriates stranded outside China may not be able to renew their work permits anymore.

Upon Dezan Shira’s confirmation with the Shenzhen foreign affair office staff, here are some solutions:

Applicants can reapply for the work permit as their first-time application, when they want to reenter China.

In this case, we suggest that you make the following preparations beforehand:

On top of the worrisome news, in July, the Guangdong province foreign affair office appears to have tightened rules on work permit application. This can be a big hurdle for start-up companies, since obtaining a work permit is often the first step towards sending employees to China.

Some first-time work permit applicants are now requested to provide additional documents that were never requested before, including (for your very general reference):

From our perspective, the purpose of tightening the rules on work permit applications is to ensure that applicants have a genuine need to work in China, and not otherwise. This is because during the pandemic, some foreigners set up companies in China, most likely, only for obtaining a work visa.

From our recent experience, it emerges that a company’s legal representative needs fewer supporting documents to receive the approval when compared to the other executive positions.

Why? Because the legal representative of a Chinese company will need to be present physically for some company-related procedures, like going to the bank for basic bank account setup, setting up a company tax account at the tax bureau, and completing the real-name authentication test.

However, the legal representative now needs to sign a labor contract, instead of simply uploading a business license. Additionally, the legal representative must have a job title in the company.

You should prepare more documents in advance to support the application, if you are not the legal representatives of the Chinese company.

In the recent work permit system feedback we received from the Guangzhou SAFEA, companies hiring foreigners must have made or are expected to make a written commitment on hiring Chinese employees, otherwise their foreign employees’ work permits may not be renewed or the applications won’t be processed.

This is also a way to ensure the company is operational (rather than a shell firm set up for visa purposes). If the company is obligated to hire Chinese employees, but, still has not done so, the work permit renewal could then also be rejected.

Shenzhen’s Safea seems to be following suit, urging companies to hire Chinese employees. For one-person companies established for visa purposes only, the renewal application could be a real challenge under the current circumstances.

This article first appeared in Asia Briefing, published by Dezan Shira Associates. The company advises international investors in Asia and has offices in China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore, Russia and Vietnam. Please contact them via info@dezanshira.com or their website www.dezanshira.com.

Shang Yanchun and Lu Man have left China’s sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corporation. Shang Yanchun headed one of two investment teams: the departments of technology, media and communications. Lu Man was a senior manager in the department of direct investment. According to Bloomberg, the fund is facing an “exodus of senior executives.” In the past five years, 20 team leaders and managing directors left the sovereign wealth fund.

What activities do you hate to be disturbed in? Maybe while “eat-ing” (吃饭ing – chīfàn-ing), “read-ing” (看书ing – kànshū-ing) or maybe while “rest-ing” (休息ing – xiūxi-ing)? When China’s “Generation Online” immerses itself completely in the moment, language and grammar boundaries become irrelevant. Chinese also has its own progressive form (吃饭 chīfàn = “to eat”, 正在吃饭 zhèngzài chīfàn = “to eat”/”to be eating”). But in Chinese Internet lingo, the English “ing” form has gained a certain “coolness”. China’s young Internet community – which is still familiar enough with the English suffix from grammar lessons in school – is now using the word suffix creatively, adding it not only to Chinese verbs but also to nouns for example and thus creating all kinds of new word creations.

These range from “amusement-ing” (娱乐ing – yúlè-ing) to “application-ing” (招聘ing – zhāopìn-ing) and “television-ing” (看电视ing – kàn diànshì-ing). Common to all forms is that they emphasize the progressive character of the action – by “ing”-in’, one is mentally and emotionally completely involved and enjoys the moment.

Incidentally, if you believe that a tonal language like Chinese is not suitable for anglicisms, then a conversation with today’s Chinese will prove you wrong fairly quickly. Thanks to influences by the Internet, the international working environment and the impactful entertainment industry, which likes to absorb foreign trends, Chinese people like to use English terms in everyday conversation without any warning.

China’s up-and-coming office workers (白领 báilǐng) paved the way by replacing many Chinese terms in their “office speak” with English placeholders, e.g. (我把link和proposal的PPT发到你的email, ok吗?) in the face of global corporate structures and communication channels. Today, it is not uncommon for anglicisms to find their way into everyday Chinese usage via a variety of nationally successful entertainment shows. Hip-hop and street dance formats, for example, made terms like “battle,” “diss,” “pick” and “freestyle” permanent vocabulary used in everyday life – even beyond the shows’ audiences. The Chinese language is ever-changing. A good reason to keep on learning – or in other words, keep on “xuéxí-ing”.

Verena Menzel runs the online language school New Chinese in Beijing.