The “common prosperity” for all Chinese is a colossal undertaking that is not only supposed to secure Xi Jinping a place in the history books, but above all, legitimize his lifelong tenure as head of state. However, how the leadership actually intends to accomplish the redistribution of wealth remains a relatively open question, writes Nico Beckert. In fact, the gap between the rich and the poor in the People’s Republic is growing ever-wider.

Wages are too low, educational opportunities between urban and rural areas are still insufficiently balanced, and even China’s slowly cooling economic growth can no longer cushion poverty. Structural change is needed. But reforms such as tax increases could also step on the toes of the system’s beneficiaries. The worst-case scenario: a “domestic destabilization of China”.

Contradictions are also visible in the current Winter Olympics. At every opportunity, its organizers are emphasizing the carbon neutrality of the huge sporting event. All Olympic venues will be powered by renewable energy, and every passenger vehicle will run on either hydrogen, natural gas, or electricity. But these measures for more sustainability are only convincing at first glance, explains Marcel Grzanna.

One particularly serious problem of the Olympics is the enormous amount of artificial snow. The irrigation of huge areas of farmland, in a region where water is scarce, has even been stopped to cover the barren brown terrain with snowy masses. The impact on the environment is difficult to determine – because, at the end of the day, the host cities are allowed to calculate their own sustainability assessment as they see fit.

“Common prosperity” will remain one of the highest goals on Beijing’s political agenda in the Year of the Tiger. At the end of the year, Xi wants to be re-elected as president. Everything indicates that he will capitalize on the fight against inequality in China before his re-election – at least verbally – in an effort to present himself as a man of the common people.

Xi has attached great importance to “shared prosperity.” In speeches, he warned of a possible “polarization” of society and an “unbridgeable gulf” caused by rising inequality (China.Table reported). So far, few substantial details have emerged about how the leadership intends to achieve “common prosperity.” What are the causes of inequality in China? And can they deduce the government’s plans?

Inequality in China has many facets. While some cruise through the big cities in luxury cars, others have to fight their way through the heavy traffic as poorly paid delivery men. While a small upper class hoards Rolex watches and Gucci bags, poverty and a lack of prospects often still dominate China’s rural areas: millions of children of migrant workers live separated from their parents and have hardly any chances of advancement (China.Table reported).

The rising inequality is also reflected in statistics. In the early 1990s, China’s upper ten percent held a good 40 to 50 percent of total wealth. By 2019, however, it was already 70 percent. According to official numbers, the Gini Coefficient for income is 0.47. Values as low as 0.4 are already considered a warning signal of excessive inequality.

The causes of inequality in China are manifold. “From the very beginning, China’s reform policy aimed to make a small group of people richer first,” says economist Wan-Hsin Liu of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). They were supposed to spur growth and create jobs and thus prosperity for millions. But while China’s rise is unprecedented, wealth remained unevenly distributed.

China’s low wages contribute to this inequality. Wages have indeed risen in recent years. But when it comes to the distribution of gross domestic product, workers in China still fare poorly. Compared to corporations or the state, they receive only a small percentage of economic output as wages or transfer payments. While the wage share of the GDP was still over 51 percent in the mid-1990s, it has since dropped to around 40 percent – and lower than in other emerging markets (China.Table reported).

China is facing a predicament here. After all, low wages are a major contributor to the country’s export strength. “China’s export competitiveness depends on ensuring that workers are allocated, whether by wages or social transfers, a relatively low share of what they produce,” writes Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University.

The situation is quite different at the upper end of the income spectrum. Politically well-connected citizens have profited from their connections for years, says Sebastian Heilmann, professor of Chinese politics and economics at Trier University. Through the privatization of public property, such as company shares and real estate, those who are well-connected have often been able to accumulate large fortunes, Heilmann says.

The household registration (hukou) system is another classic cause of inequality. It degrades over 200 million migrant workers to second-class citizens. They are largely excluded from urban social services such as health insurance, the pension system, and access to public schools. In the case of pensions, income inequality is particularly stark. People with city residence permits receive an average annual pension equivalent to €5,580. Migrant workers and residents in rural regions, on the other hand, only receive a pension of just under €280 on average – per year.

The hukou system perpetuates inequality by limiting access to quality education. Migrant workers are often unable to enroll their children in public, urban schools. They have to resort to expensive private schools, which are typically inferior to public schools. And if migrant workers leave their children in the villages, their educational prospects are even worse as the rural education system lags far behind (China.Table reported). More than 70 percent of urban school children are admitted to universities, compared to less than five percent of rural schoolchildren, as the consulting agency Trivium China recently calculated. Millions of children are thus denied any chance for advancement.

Around the world, governments use tax and welfare systems to reduce inequality to a certain degree. In China, these distribution mechanisms “have done little to counteract the ever-widening income disparities,” Liu said. In the People’s Republic, the bottom 50 percent of income earners pay more taxes than the top 50 percent, according to The Wire China. This is because indirect taxes such as value-added tax or consumption taxes dominate the Chinese tax system. However, they hit low-income earners particularly hard, as they have to spend a larger portion of their income on consumption.

Direct taxes on (high) wages and incomes, capital gains, or real estate, on the other hand, are low in China or are not levied at all. As a result, the tax system is indirectly one of the causes of inequality. “In reality, workers with a monthly salary of a few thousand yuan need to pay personal income tax, but those with millions of yuan worth of properties don’t need to do so,” Yi Xianrong, a former researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences told the South China Morning Post.

China’s social welfare system also does little to reduce inequality. Less than ten percent of unemployed people receive benefits from China’s unemployment insurance system. And the People’s Republic spends only two percent of its economic output on the country’s health care system – compared to about eight percent in developed countries. “State redistribution has hardly any effect on the Gini Index in China. By comparison, in Germany, government redistribution reduces the Gini Index by 0.19,” says Bin Yan, an advisor at the consulting firm Sinolytics.

Reforms to overcome inequality could fundamentally change China as we know it. That’s because to “overcome inequality, China needs far-reaching and long-term measures,” Liu says. Experts generally agree, however, that there will be only cautious initial reforms.

Liu assumes that gradual changes will be made to the tax system because “they are comparatively easier than reforms of the hukou system or the social and education system.” Inheritance and real estate taxes are already being discussed. Yan of Sinolytics also believes a gradual introduction of a real estate tax and a capital gains tax to be likely. The Sinolytics consultant also believes that an expansion of social benefits is possible, for example in public education and affordable housing. Campaigns to curb all forms of illegal income could be intensified in the future, Yan says.

Doris Fischer, Professor of China Business and Economics at the University of Würzburg, is skeptical about tax reforms. Instead, she says, Beijing emphasizes redistribution through philanthropy. “But charity leaves it up to companies to decide where to help. That has little to do with fundamental reform,” Fischer says. She speculates that there will be no welfare state beyond the provision of basic needs. That, she says, could not be gleaned from any “common prosperity” documents to date. So it will be more about food and a place to live rather than a decent quality of life for welfare recipients.

Pettis expects that Beijing will not raise wages to reduce inequality, as this would reduce the competitiveness of Chinese exports. However, he believes tax increases to be realistic. Businesses, he said, should be prepared that “Beijing will pass on what it deems to be the excess profits of businesses and the wealthy to middle- and working-class Chinese households in the form of fiscal transfers and donations from businesses and the wealthy.”

While Beijing is planning reforms to the household registration system, they are a “risky matter” that could “trigger large population shifts”, says Heilmann. For a true redistribution, “measures are needed that systematically curtail the access privileges of the state- and party-affiliated clientele.” That, too, would be a “risky move” for the CP. If Xi wants to get serious about redistribution, “he will encounter stubborn, and initially silent, resistance in the ranks of the political and economic elites.” This resistance could even jeopardize his position and contribute to a “domestic destabilization of China,” Heilmann believes.

Overall, Beijing has realized that “achieving common prosperity is a long-term goal,” Liu says. Beijing will proceed cautiously, she believes, but in the long run will nonetheless implement “reforms of varying intensity in many social, economic, institutional and political areas.”

The artificial snow on the hills of Yanqing and Zhangjiakou is emblematic of the discussion about the sustainability of the Winter Olympics in Beijing. Amidst barren brown landscapes, slopes and trails shine like a network of laser beams in the pitch black. Beijing may not be the first host city to create snow in winter, instead of shoveling it. But rarely has the political component been so important in the discussion about sustainability as in China’s case.

What may sound unfair, actually follows a stringent logic. Sustainability plays a much greater role now than it did just a few years ago. That is why there is a closer eye on Beijing, and why criticism is also a bit louder. The People’s Republic is also one of the world’s biggest environmental polluters. This reputation comes with it a special responsibility when hosting the Winter Olympics.

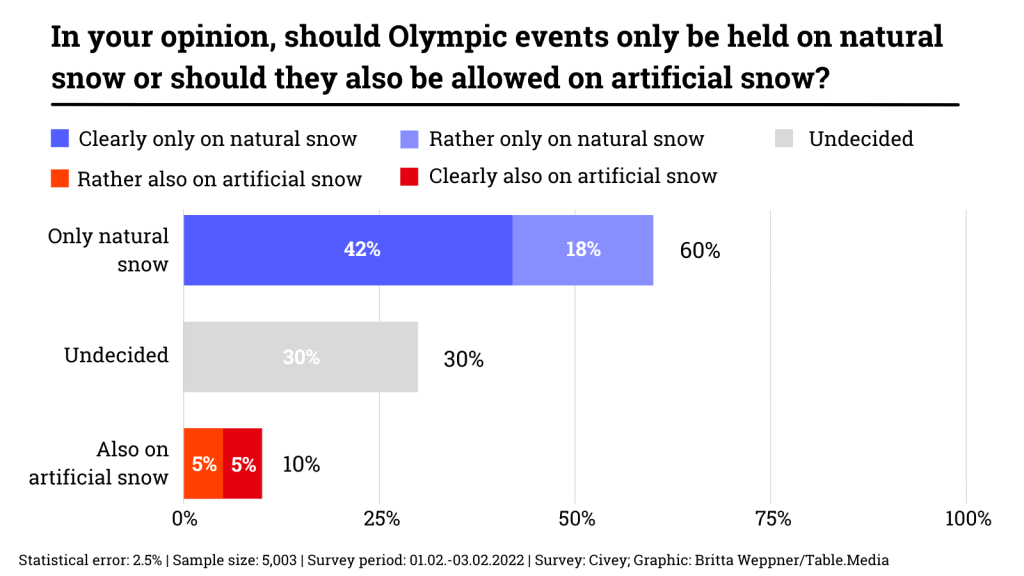

If it were up to the public, most observers would much prefer real snow anyway. In the bid for the Winter Olympics, 60 percent of German citizens would choose candidates whose climatic conditions naturally meet the requirements for skiing and cross-country skiing. Just one in ten considers artificial snow to be a good alternative. This was the result of a survey by the Berlin-based opinion and market research company Civey, which was commissioned by China.Table.

Interestingly, the disapproval of artificial snow is greatest in the over-65 age group (around 65 percent). By contrast, among 18- to 29-year-olds, only about half of those surveyed favor the real thing. What is remarkable here, is that the younger generation, in particular, is said to have a greater awareness of environmental issues than the older generation. However, artificial snow is apparently considered less of a problem for nature and more as a question of “realness”.

The amount of water used to realize the Olympics is undoubtedly enormous. The amount varies from 185 million liters to 1 billion liters. Either way, this is problematic because the region is already suffering from water shortages. In 2017, for example, residents of the Chinese capital had 136,000 liters of freshwater per capita. More recent figures are not available. The amount is roughly equivalent to the availability in the African state of Niger, on the edge of the Sahara. In Zhangjiakou, where the Alpine contests are held, it was at least 314,000 liters per capita.

In order to channel the water from Beijing to where it was needed for the production of snow, the organizers invested around €55 million in new pipelines. In Zhangjiakou, irrigation of huge stretches of farmland was stopped to conserve groundwater.

100 snow generators and 300 snow cannons produced the enormous artificial snow masses day in and day out since the end of November. A horror for the fauna of the region, which is supposed to be particularly protected according to the sustainability report of the organizing committee BOCOG. During operation, a snow cannon generates 60 to 80 decibels of noise. For months, however, several hundred of them were switched on at the same time, creating a hellish noise that must have terrified local wildlife at the very least.

Meanwhile, the Covid pandemic caused a better CO2 footprint for the Olympics. Since foreign visitors were not allowed in China, the volume of emissions was reduced by around 500,000 to 1.3 million tons. For the first time in the history of the Olympic Games, all venues are powered by renewable energies. However, this is more of a theoretical arithmetic game, as Michael Davidson from the University of California points out in the science magazine Nature.

Some venues of the 2008 Summer Games have been repurposed and are now being used again. The Watercube, where the swimming events were held 14 years ago, has now unofficially become an Icecube for curling events. The ice surfaces are cooled with natural carbon dioxide, creating a 20 percent compared to conventional technologies.

Without exception, all passenger vehicles used during the Olympics will be powered by hydrogen, electricity, or natural gas. Only 15 percent of the commercial vehicles required are equipped with combustion engines. Thanks to extensive reforestation projects in Beijing and Zhangjiakou, some 80,000 hectares of new forest land have been created since 2014. In this way, Beijing promises that the Winter Olympics will be carbon-neutral.

“We are very confident that we will be a truly carbon-neutral games,” says Liu Xinping, who is in charge of sustainability at the BOCOC. The Olympics sponsors are contributing around 600,000 metric tons of offsets. Nevertheless, 1.3 million tons of emissions for hosting the Olympics are only a tiny fraction of China’s emissions, which amount to 11 billion tons of CO2 per year. The People’s Republic is the world’s largest emitter of climate-damaging emissions.

However, the continued use of some venues is unlikely. The bobsleigh and luge track, which is said to have cost more than €2 billion to build, could be left to downright decay. The ski jumping venue in Zhangjiakou is also unlikely to be used as a World Cup ski jump. Well aware of this, the planners have laid out a soccer field in the outrun. And tourist use has also been prepared. A circular plateau is located above the jumps, where a restaurant is located.

The IOC, meanwhile, sees a new benchmark being set. Nevertheless, Beijing’s winter games are the first to have considered a broad range of emissions from the earliest stages of preparation, says Marie Sallois, a director of sustainable development at the IOC. Indirect sources of emissions, such as air travel, were also included in the calculation for the first time. The concept is to be used as a benchmark for future Olympic Games as well.

However, it remains problematic that the host cities specify their own sustainability lineups as they see fit. That’s why former Canadian 100-meter runner Seyi Smith, who is running for a spot on the IOC Athletes’ Commission where he wants to make sustainability a focus, is calling for independent third-party checks. “Systematic changes would need to come from the IOC and National Olympic Committees (…) We have to set actual goals,” Smith said on CBC Sports’ “Bring it in” web show.

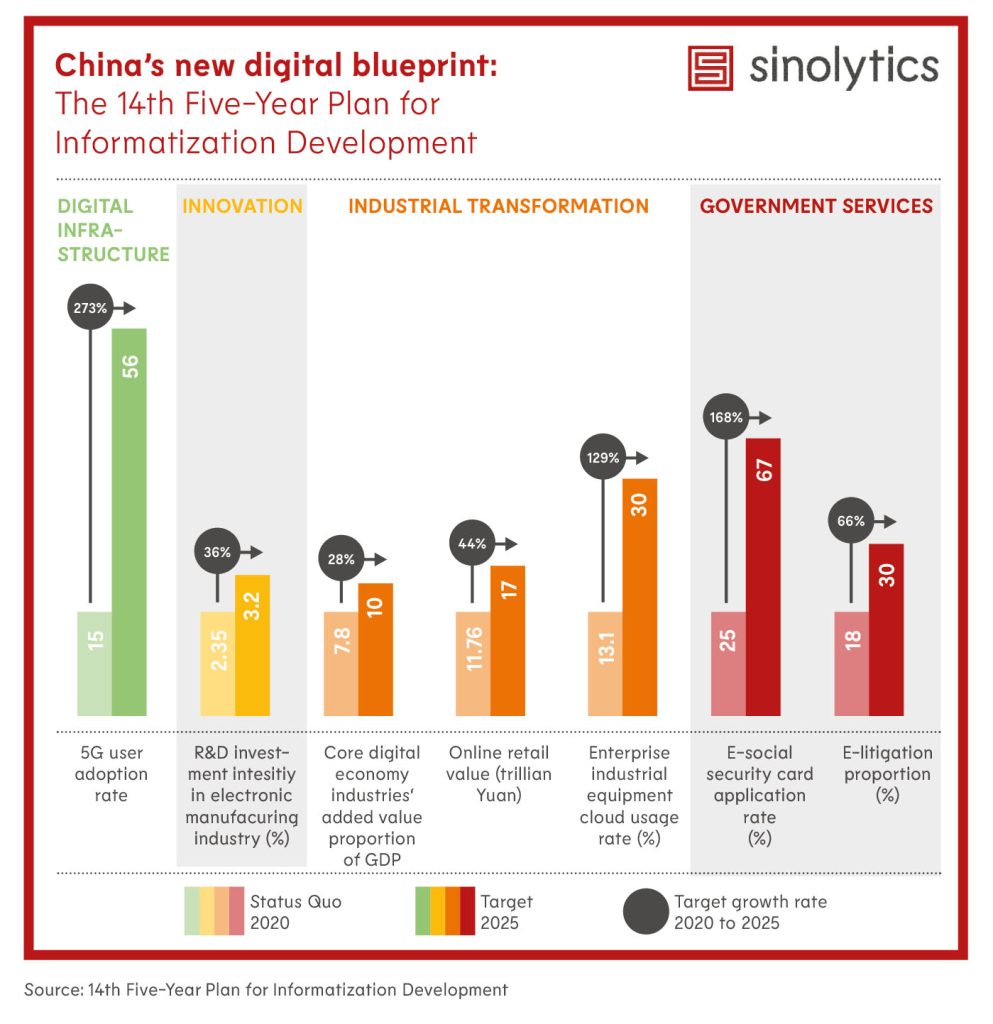

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in China.

The US has approved a potential $100 million arms deal of equipment and military services with Taiwan. Services will mainly be used to maintain and improve Taiwan’s Patriot missile defense system bought from the US, the Pentagon announced on Monday. The presidential office spokesman in Taipei stated that this would be the second arms delivery by the administration of US President Joe Biden, proving the “rock-solid” commitment to Taiwan. However, the plan to obtain new Patriot missiles from the US had already been decided during Donald Trump’s term. The prime contractors are Raytheon Technologies and Lockheed Martin, according to Pentagon data.

Beijing urged the US to cancel its supply plans. China strongly condemns the agreement, Foreign Office spokesman Zhao Lijian told the press in Beijing. China will “take all necessary measures to firmly safeguard its sovereignty, rights, and interests.” Increasing numbers of Chinese fighter jets entering Taiwan’s air defense identification zone (ADIZ) have recently increased tensions between China and Taiwan. fpe

In the coming weeks, the European Union will begin talks with China over its alleged violation of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules concerning its trade blockade of Lithuania. Beijing has agreed to the consultation request submitted by Brussels to the WTO in Geneva last month, the South China Morning Post reported, citing EU sources. Talks will have to begin within 30 days of the approval. “Consultations will be held and the EU is preparing for them,” SCMP quotes an EU spokesman as saying. If the talks fail to yield a solution, the EU may request a hearing at the WTO.

At the end of January, Brussels had turned to the WTO and filed a complaint against China (China.Table reported). Since the beginning of December, the People’s Republic has been blocking all Lithuanian goods. In mid-December, Beijing also increased pressure on German companies that wanted to export goods to China containing Lithuanian components. Beijing has so far denied any trade embargo on Lithuanian goods. ari

China has softened the climate targets for its steel sector. The sector is now not expected to reach peak CO2 emissions until 2030. That’s according to guidance issued by three ministries that regulate the sector. An earlier consultation document still spoke of an earlier date. Government advisers had argued for the period around 2025. The steel and iron industry is one of the largest CO2 emitters in the People’s Republic. Reducing CO2 emissions in this sector is crucial if China is to meet its climate targets. “To ensure nationwide peaking emissions before 2030, the steel industry would have to peak around 2025,” climate expert Liu Hongqiao wrote on Twitter.

Last year, the China Iron and Steel Association also set a target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions after 2025. According to industry figures, 30 percent less CO2 is to be emitted by 2030. Energy expert Yan Qin wrote on Twitter that the softening of the climate target was in line with recent statements by Xi Jinping. During a Politburo meeting in late January, Xi had said China’s climate targets should not come at the expense of economic development and the “everyday lives” of citizens (China.Table reported).

To curb the steel sector’s greenhouse gas emissions, the three ministries envisage the following measures:

If these measures are implemented, the sector’s CO2 emissions could peak earlier, experts say. “Unless steel output starts growing again dramatically, these measures will ensure a CO2 emission peak before 2025 – barring an increase in output, the increase in scrap input alone will deliver a 10% CO2 reduction by 2025 and get the sector on track to a 30% cut by 2030,” climate expert Lauri Myllyvirta said on Twitter.

However, Myllyvirta doubts whether the leadership in Beijing is actually willing to limit the growth of steel production and the construction sector. Both sectors are still too important for economic growth and jobs in China. nib

Because of the global semiconductor shortage, the EU Commission wants to monitor supply chains more closely in the future. The Brussels-based authority presented the corresponding “European Chips Act” on Tuesday. It provides for the creation of a new task force with representatives from the Commission, member states, and industry. The coordination mechanism is to gather “key intelligence from companies to map primary weaknesses and bottlenecks,” the EU Commission announced. The panel is to monitor market trends to identify potential supply bottlenecks as early as possible. In the event of crises and emergencies, the Commission is to be granted far-reaching intervention rights. Among other things, the legislation provides for export controls, such as those introduced by the EU for COVID-19 vaccines.

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton want to avoid a repeat of the dramatic shortages of semiconductors that have been causing problems for the automotive and electronics industries for months. “China is accelerating efforts to close its technological gap and, by 2025 it is estimated that it will have invested around USD 150 billion over the past decade in line with a series of plans and initiatives such as the ‘Made in China 2025′”, the EU Commission warned. Trade tensions between the US and China also further exacerbated supply shortages, “and it is believed that the fear of additional export bans by the US has led some Chinese companies to stockpile chips.”

In cooperation with global partners, contact with Taiwan will not be ruled out, the responsible EU commissioners emphasized during the presentation of the chip act. Taiwan is an important region, Breton said. Its expertise is welcome, he said. Europe is also open to doing business with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), said Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager.

In addition, the Commission wants to mobilize billions to more than double Europe’s share of global chip production to 20 percent by 2030. The lion’s share, around €30 billion, is to come from national budgets. The German government alone has already promised 10 billion in state aid. 12 billion is to come from EU funds such as the Horizon Europe research program. Up to 5 billion is to be mobilized via institutions such as the European Investment Bank.

To enable EU governments to attract new locations with the help of subsidies, the Commission wants to relax state aid controls. New factories that use technologies not previously available in Europe (“first of a kind in Europe”) are also to be subsidized. Up to now, subsidies have only been allowed for research and development projects up to series maturity, as part of an Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI). IPCEI projects are also costly to coordinate. The new procedure could speed up the approval process under state aid law. tho/ari

Monday and Tuesday have proven to be very successful for China: The athletes of the host won four medals, two gold, and two silver. In the medal table, China is now on rank three together with Germany (three times gold, two times silver). Freestyle star Eileen Gu won the much anticipated first gold on Tuesday. But there were other headlines, too: Nationalists spawned a veritable shit storm on social media against a figure skater who had an unfortunate fall. The comments were so vile that even the state censors had to intervene and remove the corresponding hashtags.

The Germans once dubbed their 2006 World Cup a “summer fairy tale” – a success story that was overshadowed years later by allegations of corruption. But it was a huge event that gave Germany a lot of “soft power”, both inside and outside the country.

Two years later, the People’s Republic of China wrote its own “summer fairy tale” when it hosted the Olympic Games in Beijing for the first time. Now, 14 years later, Beijing is going down in history as the first host city for both the Summer and Winter Olympics. It has been a long road for the country.

After the founding of the People’s Republic, it had turned its back on the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1958. It was not until 22 years later that it returned to the Olympic fold, entering the 1980 Winter Games in Lake Placid, USA, with a handful of athletes. The timing was no coincidence: After three decades of isolation under Mao Zedong’s iron rule, China was once again welcomed back in the broader international community in the late 1970s with Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door Policy.

With the economic upswing and its own image in the world improving, China also participated in the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles and won 32 medals, including 15 gold. The “shameful” track record without any Olympic medals had ended.

The growing number of medals inspired the Chinese government to bring the Olympic fire to their home country as well. The successful bid for 2008 had been submitted seven years earlier. 2001 was also the year China joined the World Trade Organization. The official slogan of the Olympics was “One World, One Dream,” but the true message was a different one: “Hello world, here we are, an emerging power. And we are here to stay.”

The Chinese government rolled out the red carpet for guests and dignitaries from around the world, including then-US President George W. Bush, his wife and daughter, and his father, former US President George H. W. Bush. The family attended the opening ceremony and watched the events. Bush met with Chinese President Hu Jintao and other high-ranking officials.

Bush said at the time, “In the long run, America better remain engaged with China, and understand that we can have a cooperative and constructive, yet candid relationship.” It was the prime of US-China relations. But things have changed a lot since then.

China proudly celebrated the perfectly staged Games as a huge success. Criticism of the hosting and boycott calls due to the suppression of the uprising in Tibet a few months earlier did not harm its rise. Especially since its economy was booming with double-digit growth rates, while the industrialized nations were groaning under the consequences of the global economic crisis.

From the Chinese perspective, the successful bid for 2022 under its new President Xi Jinping was another step towards the realization of the “Chinese dream”. Xi wants to strengthen the confidence of the Chinese people in their own culture and increase the country’s international influence. The question remains whether this will work.

Even though the 2022 Winter Olympics will most likely be a political success at home, it is a great challenge for the host country to create a winter fairy tale on the international stage that will have the world dreaming along. The controversies seem far too great. Numerous Western countries have announced a diplomatic boycott of the Olympics because they accuse China of committing genocide against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

Since its Olympic bid, China has seen greater change than many Chinese dared to dream of. GDP per capita has steadily increased to $10,500 in 2020 compared to $7000 in 2013. As of 2017, China’s economy is the largest in the world in terms of purchasing power parity. And according to the Chinese government, extreme poverty has been eliminated since the late 2000s. In recent years, China has surpassed many Western industrialized countries in infrastructure, telecommunications, AI technology, military armament, and space exploration.

For China, this is a vindication to appear more confident and self-assured, to voice ambitions, and to proudly highlight the efficacy of its authoritarian government system. In the West, China has become a strategic competitor-and the “quest” for global political community and recognition is now under different geopolitical auspices. In 2022, the world is more polarized, and Western perceptions of China have changed dramatically, causing the country to struggle in building “soft power”.

At the very least, it is rather likely that Beijing will achieve its domestic political goals. The Winter Olympics will boost the enormous potential of the winter sports consumer market, and the Olympics will further strengthen national pride.

But multinational companies seeking to use this global positioning opportunity to promote their own brands face a challenge: How to express enthusiasm for the Olympics without simultaneously provoking a backlash in the West and subsequently drawing criticism from politicians, human rights groups, and the media?

We believe that companies who master bridging the gap between China and the West will continue to prosper. Those that will not allow themselves to be pulled into the vicious circle of polarization will remain relevant across the gap and will not let the connection break down.

Claudia Kosser leads the Shanghai office and develops and executes integrated communications strategies for corporate positioning in China, cross-border M&A transactions, crisis mandates, or transformation and change projects. She has more than a decade of professional experience and opened Finsbury Glover Hering’s Shanghai office in 2019 after serving the company in Frankfurt and Hong Kong since 2011. She holds a Master in Communication Management from Leipzig University, and a Bachelor degree in European Studies from the University of Maastricht.

Mei Zhang is Managing Director at the Hong Kong office of Finsbury Glover Hering and has more than 25-years of professional experience in news media, public affairs, and international communications. During her career, she worked at Goldman Sachs and Citigroup, as well as CNN in Atlanta. She was a founding board member of the NGO Teach for China. She holds an M.A. in Mass Communications from Louisiana State University and a B.A. in International Journalism from Beijing Institute of International Relations.

In Collaboration with Tom Miller

Matthew Jung is taking over the position of General Manager for China at Jack Wolfskin. The 48-year-old US citizen has held executive positions in the Asia-Pacific region for 25 years, including for brands such as Converse and Nike. Jung succeeds Karen Chang, who will leave Jack Wolfskin in March 2022.

Christoph Schmidt has been Vice President of Sales at Bosch Power Tools in Shanghai since December. Schmidt previously worked for the German power tool company for almost four years as Director Business Development Emerging Markets.

The Big Air Shougang Park is currently causing heated debate on social media channels like Twitter. The 64-meter-high and 164-meter-long ski jump was built for the Winter Olympics in the middle of a decommissioned steel mill in Beijing’s western Shijingshan district. Critics say that dirty cooling towers instead of snow-covered mountains are typically Chinese. In the German Ruhr region, they would perhaps call it industrial chic.

The “common prosperity” for all Chinese is a colossal undertaking that is not only supposed to secure Xi Jinping a place in the history books, but above all, legitimize his lifelong tenure as head of state. However, how the leadership actually intends to accomplish the redistribution of wealth remains a relatively open question, writes Nico Beckert. In fact, the gap between the rich and the poor in the People’s Republic is growing ever-wider.

Wages are too low, educational opportunities between urban and rural areas are still insufficiently balanced, and even China’s slowly cooling economic growth can no longer cushion poverty. Structural change is needed. But reforms such as tax increases could also step on the toes of the system’s beneficiaries. The worst-case scenario: a “domestic destabilization of China”.

Contradictions are also visible in the current Winter Olympics. At every opportunity, its organizers are emphasizing the carbon neutrality of the huge sporting event. All Olympic venues will be powered by renewable energy, and every passenger vehicle will run on either hydrogen, natural gas, or electricity. But these measures for more sustainability are only convincing at first glance, explains Marcel Grzanna.

One particularly serious problem of the Olympics is the enormous amount of artificial snow. The irrigation of huge areas of farmland, in a region where water is scarce, has even been stopped to cover the barren brown terrain with snowy masses. The impact on the environment is difficult to determine – because, at the end of the day, the host cities are allowed to calculate their own sustainability assessment as they see fit.

“Common prosperity” will remain one of the highest goals on Beijing’s political agenda in the Year of the Tiger. At the end of the year, Xi wants to be re-elected as president. Everything indicates that he will capitalize on the fight against inequality in China before his re-election – at least verbally – in an effort to present himself as a man of the common people.

Xi has attached great importance to “shared prosperity.” In speeches, he warned of a possible “polarization” of society and an “unbridgeable gulf” caused by rising inequality (China.Table reported). So far, few substantial details have emerged about how the leadership intends to achieve “common prosperity.” What are the causes of inequality in China? And can they deduce the government’s plans?

Inequality in China has many facets. While some cruise through the big cities in luxury cars, others have to fight their way through the heavy traffic as poorly paid delivery men. While a small upper class hoards Rolex watches and Gucci bags, poverty and a lack of prospects often still dominate China’s rural areas: millions of children of migrant workers live separated from their parents and have hardly any chances of advancement (China.Table reported).

The rising inequality is also reflected in statistics. In the early 1990s, China’s upper ten percent held a good 40 to 50 percent of total wealth. By 2019, however, it was already 70 percent. According to official numbers, the Gini Coefficient for income is 0.47. Values as low as 0.4 are already considered a warning signal of excessive inequality.

The causes of inequality in China are manifold. “From the very beginning, China’s reform policy aimed to make a small group of people richer first,” says economist Wan-Hsin Liu of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). They were supposed to spur growth and create jobs and thus prosperity for millions. But while China’s rise is unprecedented, wealth remained unevenly distributed.

China’s low wages contribute to this inequality. Wages have indeed risen in recent years. But when it comes to the distribution of gross domestic product, workers in China still fare poorly. Compared to corporations or the state, they receive only a small percentage of economic output as wages or transfer payments. While the wage share of the GDP was still over 51 percent in the mid-1990s, it has since dropped to around 40 percent – and lower than in other emerging markets (China.Table reported).

China is facing a predicament here. After all, low wages are a major contributor to the country’s export strength. “China’s export competitiveness depends on ensuring that workers are allocated, whether by wages or social transfers, a relatively low share of what they produce,” writes Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University.

The situation is quite different at the upper end of the income spectrum. Politically well-connected citizens have profited from their connections for years, says Sebastian Heilmann, professor of Chinese politics and economics at Trier University. Through the privatization of public property, such as company shares and real estate, those who are well-connected have often been able to accumulate large fortunes, Heilmann says.

The household registration (hukou) system is another classic cause of inequality. It degrades over 200 million migrant workers to second-class citizens. They are largely excluded from urban social services such as health insurance, the pension system, and access to public schools. In the case of pensions, income inequality is particularly stark. People with city residence permits receive an average annual pension equivalent to €5,580. Migrant workers and residents in rural regions, on the other hand, only receive a pension of just under €280 on average – per year.

The hukou system perpetuates inequality by limiting access to quality education. Migrant workers are often unable to enroll their children in public, urban schools. They have to resort to expensive private schools, which are typically inferior to public schools. And if migrant workers leave their children in the villages, their educational prospects are even worse as the rural education system lags far behind (China.Table reported). More than 70 percent of urban school children are admitted to universities, compared to less than five percent of rural schoolchildren, as the consulting agency Trivium China recently calculated. Millions of children are thus denied any chance for advancement.

Around the world, governments use tax and welfare systems to reduce inequality to a certain degree. In China, these distribution mechanisms “have done little to counteract the ever-widening income disparities,” Liu said. In the People’s Republic, the bottom 50 percent of income earners pay more taxes than the top 50 percent, according to The Wire China. This is because indirect taxes such as value-added tax or consumption taxes dominate the Chinese tax system. However, they hit low-income earners particularly hard, as they have to spend a larger portion of their income on consumption.

Direct taxes on (high) wages and incomes, capital gains, or real estate, on the other hand, are low in China or are not levied at all. As a result, the tax system is indirectly one of the causes of inequality. “In reality, workers with a monthly salary of a few thousand yuan need to pay personal income tax, but those with millions of yuan worth of properties don’t need to do so,” Yi Xianrong, a former researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences told the South China Morning Post.

China’s social welfare system also does little to reduce inequality. Less than ten percent of unemployed people receive benefits from China’s unemployment insurance system. And the People’s Republic spends only two percent of its economic output on the country’s health care system – compared to about eight percent in developed countries. “State redistribution has hardly any effect on the Gini Index in China. By comparison, in Germany, government redistribution reduces the Gini Index by 0.19,” says Bin Yan, an advisor at the consulting firm Sinolytics.

Reforms to overcome inequality could fundamentally change China as we know it. That’s because to “overcome inequality, China needs far-reaching and long-term measures,” Liu says. Experts generally agree, however, that there will be only cautious initial reforms.

Liu assumes that gradual changes will be made to the tax system because “they are comparatively easier than reforms of the hukou system or the social and education system.” Inheritance and real estate taxes are already being discussed. Yan of Sinolytics also believes a gradual introduction of a real estate tax and a capital gains tax to be likely. The Sinolytics consultant also believes that an expansion of social benefits is possible, for example in public education and affordable housing. Campaigns to curb all forms of illegal income could be intensified in the future, Yan says.

Doris Fischer, Professor of China Business and Economics at the University of Würzburg, is skeptical about tax reforms. Instead, she says, Beijing emphasizes redistribution through philanthropy. “But charity leaves it up to companies to decide where to help. That has little to do with fundamental reform,” Fischer says. She speculates that there will be no welfare state beyond the provision of basic needs. That, she says, could not be gleaned from any “common prosperity” documents to date. So it will be more about food and a place to live rather than a decent quality of life for welfare recipients.

Pettis expects that Beijing will not raise wages to reduce inequality, as this would reduce the competitiveness of Chinese exports. However, he believes tax increases to be realistic. Businesses, he said, should be prepared that “Beijing will pass on what it deems to be the excess profits of businesses and the wealthy to middle- and working-class Chinese households in the form of fiscal transfers and donations from businesses and the wealthy.”

While Beijing is planning reforms to the household registration system, they are a “risky matter” that could “trigger large population shifts”, says Heilmann. For a true redistribution, “measures are needed that systematically curtail the access privileges of the state- and party-affiliated clientele.” That, too, would be a “risky move” for the CP. If Xi wants to get serious about redistribution, “he will encounter stubborn, and initially silent, resistance in the ranks of the political and economic elites.” This resistance could even jeopardize his position and contribute to a “domestic destabilization of China,” Heilmann believes.

Overall, Beijing has realized that “achieving common prosperity is a long-term goal,” Liu says. Beijing will proceed cautiously, she believes, but in the long run will nonetheless implement “reforms of varying intensity in many social, economic, institutional and political areas.”

The artificial snow on the hills of Yanqing and Zhangjiakou is emblematic of the discussion about the sustainability of the Winter Olympics in Beijing. Amidst barren brown landscapes, slopes and trails shine like a network of laser beams in the pitch black. Beijing may not be the first host city to create snow in winter, instead of shoveling it. But rarely has the political component been so important in the discussion about sustainability as in China’s case.

What may sound unfair, actually follows a stringent logic. Sustainability plays a much greater role now than it did just a few years ago. That is why there is a closer eye on Beijing, and why criticism is also a bit louder. The People’s Republic is also one of the world’s biggest environmental polluters. This reputation comes with it a special responsibility when hosting the Winter Olympics.

If it were up to the public, most observers would much prefer real snow anyway. In the bid for the Winter Olympics, 60 percent of German citizens would choose candidates whose climatic conditions naturally meet the requirements for skiing and cross-country skiing. Just one in ten considers artificial snow to be a good alternative. This was the result of a survey by the Berlin-based opinion and market research company Civey, which was commissioned by China.Table.

Interestingly, the disapproval of artificial snow is greatest in the over-65 age group (around 65 percent). By contrast, among 18- to 29-year-olds, only about half of those surveyed favor the real thing. What is remarkable here, is that the younger generation, in particular, is said to have a greater awareness of environmental issues than the older generation. However, artificial snow is apparently considered less of a problem for nature and more as a question of “realness”.

The amount of water used to realize the Olympics is undoubtedly enormous. The amount varies from 185 million liters to 1 billion liters. Either way, this is problematic because the region is already suffering from water shortages. In 2017, for example, residents of the Chinese capital had 136,000 liters of freshwater per capita. More recent figures are not available. The amount is roughly equivalent to the availability in the African state of Niger, on the edge of the Sahara. In Zhangjiakou, where the Alpine contests are held, it was at least 314,000 liters per capita.

In order to channel the water from Beijing to where it was needed for the production of snow, the organizers invested around €55 million in new pipelines. In Zhangjiakou, irrigation of huge stretches of farmland was stopped to conserve groundwater.

100 snow generators and 300 snow cannons produced the enormous artificial snow masses day in and day out since the end of November. A horror for the fauna of the region, which is supposed to be particularly protected according to the sustainability report of the organizing committee BOCOG. During operation, a snow cannon generates 60 to 80 decibels of noise. For months, however, several hundred of them were switched on at the same time, creating a hellish noise that must have terrified local wildlife at the very least.

Meanwhile, the Covid pandemic caused a better CO2 footprint for the Olympics. Since foreign visitors were not allowed in China, the volume of emissions was reduced by around 500,000 to 1.3 million tons. For the first time in the history of the Olympic Games, all venues are powered by renewable energies. However, this is more of a theoretical arithmetic game, as Michael Davidson from the University of California points out in the science magazine Nature.

Some venues of the 2008 Summer Games have been repurposed and are now being used again. The Watercube, where the swimming events were held 14 years ago, has now unofficially become an Icecube for curling events. The ice surfaces are cooled with natural carbon dioxide, creating a 20 percent compared to conventional technologies.

Without exception, all passenger vehicles used during the Olympics will be powered by hydrogen, electricity, or natural gas. Only 15 percent of the commercial vehicles required are equipped with combustion engines. Thanks to extensive reforestation projects in Beijing and Zhangjiakou, some 80,000 hectares of new forest land have been created since 2014. In this way, Beijing promises that the Winter Olympics will be carbon-neutral.

“We are very confident that we will be a truly carbon-neutral games,” says Liu Xinping, who is in charge of sustainability at the BOCOC. The Olympics sponsors are contributing around 600,000 metric tons of offsets. Nevertheless, 1.3 million tons of emissions for hosting the Olympics are only a tiny fraction of China’s emissions, which amount to 11 billion tons of CO2 per year. The People’s Republic is the world’s largest emitter of climate-damaging emissions.

However, the continued use of some venues is unlikely. The bobsleigh and luge track, which is said to have cost more than €2 billion to build, could be left to downright decay. The ski jumping venue in Zhangjiakou is also unlikely to be used as a World Cup ski jump. Well aware of this, the planners have laid out a soccer field in the outrun. And tourist use has also been prepared. A circular plateau is located above the jumps, where a restaurant is located.

The IOC, meanwhile, sees a new benchmark being set. Nevertheless, Beijing’s winter games are the first to have considered a broad range of emissions from the earliest stages of preparation, says Marie Sallois, a director of sustainable development at the IOC. Indirect sources of emissions, such as air travel, were also included in the calculation for the first time. The concept is to be used as a benchmark for future Olympic Games as well.

However, it remains problematic that the host cities specify their own sustainability lineups as they see fit. That’s why former Canadian 100-meter runner Seyi Smith, who is running for a spot on the IOC Athletes’ Commission where he wants to make sustainability a focus, is calling for independent third-party checks. “Systematic changes would need to come from the IOC and National Olympic Committees (…) We have to set actual goals,” Smith said on CBC Sports’ “Bring it in” web show.

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in China.

The US has approved a potential $100 million arms deal of equipment and military services with Taiwan. Services will mainly be used to maintain and improve Taiwan’s Patriot missile defense system bought from the US, the Pentagon announced on Monday. The presidential office spokesman in Taipei stated that this would be the second arms delivery by the administration of US President Joe Biden, proving the “rock-solid” commitment to Taiwan. However, the plan to obtain new Patriot missiles from the US had already been decided during Donald Trump’s term. The prime contractors are Raytheon Technologies and Lockheed Martin, according to Pentagon data.

Beijing urged the US to cancel its supply plans. China strongly condemns the agreement, Foreign Office spokesman Zhao Lijian told the press in Beijing. China will “take all necessary measures to firmly safeguard its sovereignty, rights, and interests.” Increasing numbers of Chinese fighter jets entering Taiwan’s air defense identification zone (ADIZ) have recently increased tensions between China and Taiwan. fpe

In the coming weeks, the European Union will begin talks with China over its alleged violation of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules concerning its trade blockade of Lithuania. Beijing has agreed to the consultation request submitted by Brussels to the WTO in Geneva last month, the South China Morning Post reported, citing EU sources. Talks will have to begin within 30 days of the approval. “Consultations will be held and the EU is preparing for them,” SCMP quotes an EU spokesman as saying. If the talks fail to yield a solution, the EU may request a hearing at the WTO.

At the end of January, Brussels had turned to the WTO and filed a complaint against China (China.Table reported). Since the beginning of December, the People’s Republic has been blocking all Lithuanian goods. In mid-December, Beijing also increased pressure on German companies that wanted to export goods to China containing Lithuanian components. Beijing has so far denied any trade embargo on Lithuanian goods. ari

China has softened the climate targets for its steel sector. The sector is now not expected to reach peak CO2 emissions until 2030. That’s according to guidance issued by three ministries that regulate the sector. An earlier consultation document still spoke of an earlier date. Government advisers had argued for the period around 2025. The steel and iron industry is one of the largest CO2 emitters in the People’s Republic. Reducing CO2 emissions in this sector is crucial if China is to meet its climate targets. “To ensure nationwide peaking emissions before 2030, the steel industry would have to peak around 2025,” climate expert Liu Hongqiao wrote on Twitter.

Last year, the China Iron and Steel Association also set a target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions after 2025. According to industry figures, 30 percent less CO2 is to be emitted by 2030. Energy expert Yan Qin wrote on Twitter that the softening of the climate target was in line with recent statements by Xi Jinping. During a Politburo meeting in late January, Xi had said China’s climate targets should not come at the expense of economic development and the “everyday lives” of citizens (China.Table reported).

To curb the steel sector’s greenhouse gas emissions, the three ministries envisage the following measures:

If these measures are implemented, the sector’s CO2 emissions could peak earlier, experts say. “Unless steel output starts growing again dramatically, these measures will ensure a CO2 emission peak before 2025 – barring an increase in output, the increase in scrap input alone will deliver a 10% CO2 reduction by 2025 and get the sector on track to a 30% cut by 2030,” climate expert Lauri Myllyvirta said on Twitter.

However, Myllyvirta doubts whether the leadership in Beijing is actually willing to limit the growth of steel production and the construction sector. Both sectors are still too important for economic growth and jobs in China. nib

Because of the global semiconductor shortage, the EU Commission wants to monitor supply chains more closely in the future. The Brussels-based authority presented the corresponding “European Chips Act” on Tuesday. It provides for the creation of a new task force with representatives from the Commission, member states, and industry. The coordination mechanism is to gather “key intelligence from companies to map primary weaknesses and bottlenecks,” the EU Commission announced. The panel is to monitor market trends to identify potential supply bottlenecks as early as possible. In the event of crises and emergencies, the Commission is to be granted far-reaching intervention rights. Among other things, the legislation provides for export controls, such as those introduced by the EU for COVID-19 vaccines.

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton want to avoid a repeat of the dramatic shortages of semiconductors that have been causing problems for the automotive and electronics industries for months. “China is accelerating efforts to close its technological gap and, by 2025 it is estimated that it will have invested around USD 150 billion over the past decade in line with a series of plans and initiatives such as the ‘Made in China 2025′”, the EU Commission warned. Trade tensions between the US and China also further exacerbated supply shortages, “and it is believed that the fear of additional export bans by the US has led some Chinese companies to stockpile chips.”

In cooperation with global partners, contact with Taiwan will not be ruled out, the responsible EU commissioners emphasized during the presentation of the chip act. Taiwan is an important region, Breton said. Its expertise is welcome, he said. Europe is also open to doing business with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), said Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager.

In addition, the Commission wants to mobilize billions to more than double Europe’s share of global chip production to 20 percent by 2030. The lion’s share, around €30 billion, is to come from national budgets. The German government alone has already promised 10 billion in state aid. 12 billion is to come from EU funds such as the Horizon Europe research program. Up to 5 billion is to be mobilized via institutions such as the European Investment Bank.

To enable EU governments to attract new locations with the help of subsidies, the Commission wants to relax state aid controls. New factories that use technologies not previously available in Europe (“first of a kind in Europe”) are also to be subsidized. Up to now, subsidies have only been allowed for research and development projects up to series maturity, as part of an Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI). IPCEI projects are also costly to coordinate. The new procedure could speed up the approval process under state aid law. tho/ari

Monday and Tuesday have proven to be very successful for China: The athletes of the host won four medals, two gold, and two silver. In the medal table, China is now on rank three together with Germany (three times gold, two times silver). Freestyle star Eileen Gu won the much anticipated first gold on Tuesday. But there were other headlines, too: Nationalists spawned a veritable shit storm on social media against a figure skater who had an unfortunate fall. The comments were so vile that even the state censors had to intervene and remove the corresponding hashtags.

The Germans once dubbed their 2006 World Cup a “summer fairy tale” – a success story that was overshadowed years later by allegations of corruption. But it was a huge event that gave Germany a lot of “soft power”, both inside and outside the country.

Two years later, the People’s Republic of China wrote its own “summer fairy tale” when it hosted the Olympic Games in Beijing for the first time. Now, 14 years later, Beijing is going down in history as the first host city for both the Summer and Winter Olympics. It has been a long road for the country.

After the founding of the People’s Republic, it had turned its back on the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1958. It was not until 22 years later that it returned to the Olympic fold, entering the 1980 Winter Games in Lake Placid, USA, with a handful of athletes. The timing was no coincidence: After three decades of isolation under Mao Zedong’s iron rule, China was once again welcomed back in the broader international community in the late 1970s with Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door Policy.

With the economic upswing and its own image in the world improving, China also participated in the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles and won 32 medals, including 15 gold. The “shameful” track record without any Olympic medals had ended.

The growing number of medals inspired the Chinese government to bring the Olympic fire to their home country as well. The successful bid for 2008 had been submitted seven years earlier. 2001 was also the year China joined the World Trade Organization. The official slogan of the Olympics was “One World, One Dream,” but the true message was a different one: “Hello world, here we are, an emerging power. And we are here to stay.”

The Chinese government rolled out the red carpet for guests and dignitaries from around the world, including then-US President George W. Bush, his wife and daughter, and his father, former US President George H. W. Bush. The family attended the opening ceremony and watched the events. Bush met with Chinese President Hu Jintao and other high-ranking officials.

Bush said at the time, “In the long run, America better remain engaged with China, and understand that we can have a cooperative and constructive, yet candid relationship.” It was the prime of US-China relations. But things have changed a lot since then.

China proudly celebrated the perfectly staged Games as a huge success. Criticism of the hosting and boycott calls due to the suppression of the uprising in Tibet a few months earlier did not harm its rise. Especially since its economy was booming with double-digit growth rates, while the industrialized nations were groaning under the consequences of the global economic crisis.

From the Chinese perspective, the successful bid for 2022 under its new President Xi Jinping was another step towards the realization of the “Chinese dream”. Xi wants to strengthen the confidence of the Chinese people in their own culture and increase the country’s international influence. The question remains whether this will work.

Even though the 2022 Winter Olympics will most likely be a political success at home, it is a great challenge for the host country to create a winter fairy tale on the international stage that will have the world dreaming along. The controversies seem far too great. Numerous Western countries have announced a diplomatic boycott of the Olympics because they accuse China of committing genocide against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

Since its Olympic bid, China has seen greater change than many Chinese dared to dream of. GDP per capita has steadily increased to $10,500 in 2020 compared to $7000 in 2013. As of 2017, China’s economy is the largest in the world in terms of purchasing power parity. And according to the Chinese government, extreme poverty has been eliminated since the late 2000s. In recent years, China has surpassed many Western industrialized countries in infrastructure, telecommunications, AI technology, military armament, and space exploration.

For China, this is a vindication to appear more confident and self-assured, to voice ambitions, and to proudly highlight the efficacy of its authoritarian government system. In the West, China has become a strategic competitor-and the “quest” for global political community and recognition is now under different geopolitical auspices. In 2022, the world is more polarized, and Western perceptions of China have changed dramatically, causing the country to struggle in building “soft power”.

At the very least, it is rather likely that Beijing will achieve its domestic political goals. The Winter Olympics will boost the enormous potential of the winter sports consumer market, and the Olympics will further strengthen national pride.

But multinational companies seeking to use this global positioning opportunity to promote their own brands face a challenge: How to express enthusiasm for the Olympics without simultaneously provoking a backlash in the West and subsequently drawing criticism from politicians, human rights groups, and the media?

We believe that companies who master bridging the gap between China and the West will continue to prosper. Those that will not allow themselves to be pulled into the vicious circle of polarization will remain relevant across the gap and will not let the connection break down.

Claudia Kosser leads the Shanghai office and develops and executes integrated communications strategies for corporate positioning in China, cross-border M&A transactions, crisis mandates, or transformation and change projects. She has more than a decade of professional experience and opened Finsbury Glover Hering’s Shanghai office in 2019 after serving the company in Frankfurt and Hong Kong since 2011. She holds a Master in Communication Management from Leipzig University, and a Bachelor degree in European Studies from the University of Maastricht.

Mei Zhang is Managing Director at the Hong Kong office of Finsbury Glover Hering and has more than 25-years of professional experience in news media, public affairs, and international communications. During her career, she worked at Goldman Sachs and Citigroup, as well as CNN in Atlanta. She was a founding board member of the NGO Teach for China. She holds an M.A. in Mass Communications from Louisiana State University and a B.A. in International Journalism from Beijing Institute of International Relations.

In Collaboration with Tom Miller

Matthew Jung is taking over the position of General Manager for China at Jack Wolfskin. The 48-year-old US citizen has held executive positions in the Asia-Pacific region for 25 years, including for brands such as Converse and Nike. Jung succeeds Karen Chang, who will leave Jack Wolfskin in March 2022.

Christoph Schmidt has been Vice President of Sales at Bosch Power Tools in Shanghai since December. Schmidt previously worked for the German power tool company for almost four years as Director Business Development Emerging Markets.

The Big Air Shougang Park is currently causing heated debate on social media channels like Twitter. The 64-meter-high and 164-meter-long ski jump was built for the Winter Olympics in the middle of a decommissioned steel mill in Beijing’s western Shijingshan district. Critics say that dirty cooling towers instead of snow-covered mountains are typically Chinese. In the German Ruhr region, they would perhaps call it industrial chic.