The Russian invasion of Ukraine continues to cast a shadow on everything else. Among other things, Europe and Russia have now closed-off each other’s airspace. The impacts are obvious: longer flight times, higher costs, and additional pressure on already heavily strained supply chains. After all, the air route to China has suddenly been extended by 1,200 kilometers. But even in this dispute, the old truism applies: When two quarrel, a third rejoices. Finn Mayer-Kuckuk explains why this third party is mostly Air China Cargo in this case, and how Asian airlines benefit from the European-Russian sanctions spiral.

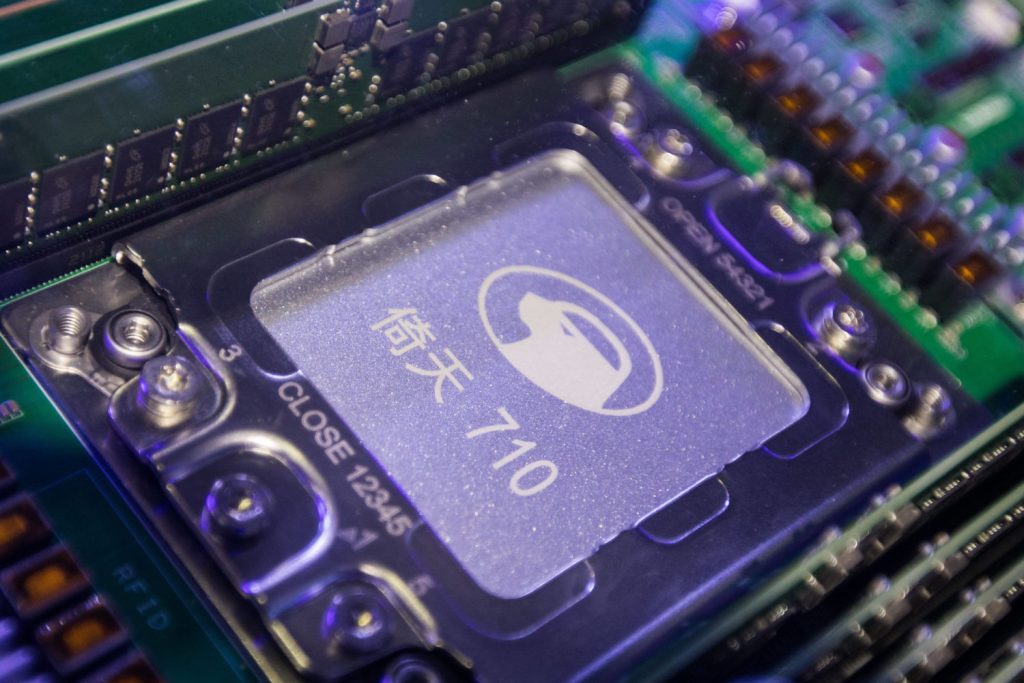

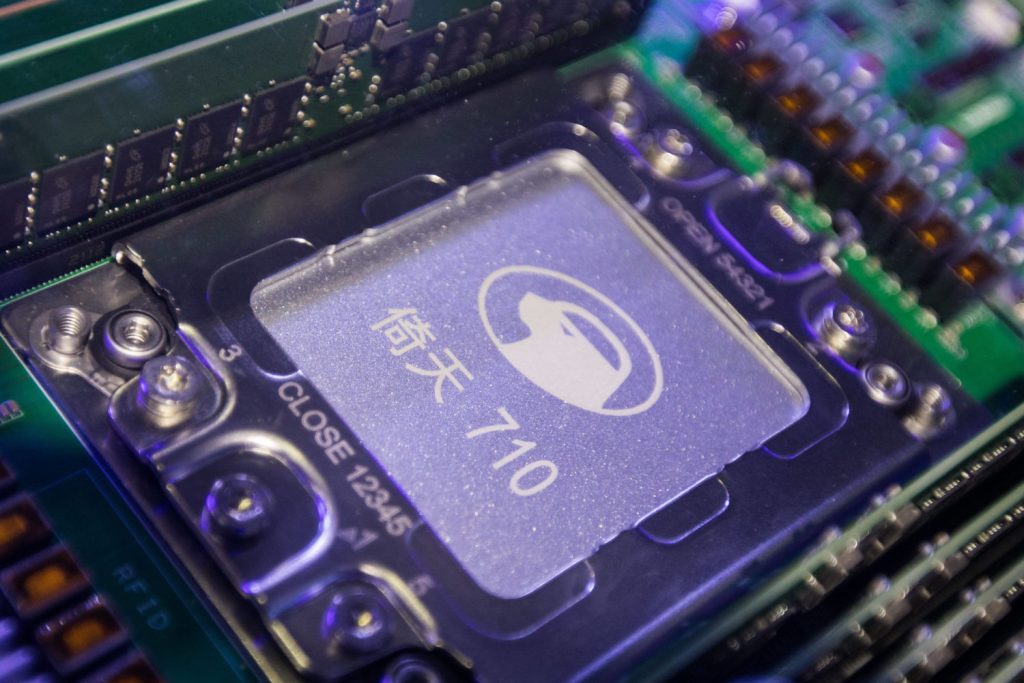

Our second analysis of today also examines the consequences of European sanctions against Russia. Specifically, it is about punitive measures in the high-tech sector. The focus is primarily on semiconductors, computers, mobile phones, and other high-tech commodities that Russia urgently requires to modernize its economy. Some Chinese semiconductors manufacturers now may hope to fill the gaps in the Russian tech market. But it will not be so easy. Ning Wang shows that both Beijing and Moscow should think carefully about undermining Europe’s high-tech sanctions this way.

Russian airspace has been closed to aircraft from the EU since Monday. Over the weekend, two Lufthansa flights to Seoul and to Tokyo were already forced to turn back mid-flight and return to Munich and Frankfurt, respectively. “Due to the ongoing dramatic developments in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Lufthansa will no longer use Russian airspace,” a spokeswoman said on Monday.

Lufthansa alone is now canceling 30 eastbound flights for which no other routes could be found or are no longer profitable due to lack of demand. The remaining aircraft are operating alternative routes south of Russian airspace. Swiss, the Group’s subsidiary, is also no longer flying over Russia. Over the weekend, the company still declared that it would be able to continue its Far East operations as usual due to Switzerland’s different rules.

This means that China is still accessible. However, the route will be around 1,200 kilometers, or one and a half hours, longer. “In terms of range, this is not a problem for the aircraft in use today,” says aviation expert Heinrich Großbongardt of the consultancy Expairtise in Hamburg. Flight service consultants did invest considerable extra work over the weekend to draw up the new schedules and routes. But flights to Asia can at least continue. A double blessing in disguise: Because of the pandemic, the routes were hardly busy anyway, which now makes it easier to manage the new situation. In normal operations, this would have led to chaos, believes Großbongardt.

Cargo routes are now more affected, which may also have an impact on supply chains. “Lufthansa Cargo will fly around Russian airspace via a southern routing,” the spokeswoman said. “This will make adjustments to the flight schedule and payload unavoidable.” In other words, aircraft won’t be able to carry as much cargo and will arrive later. By circumventing Russian airspace, most cargo flights to Asia are no longer economical, said Topi Manner, Finnair’s chief executive.

Großbongardt expects rising freight traffic costs as a result. Fully loaded cargo planes have less range. Asian flights then have to stop over in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, for example, for refueling. All this costs money and time. This will likely have an impact on shipping charges, pushing up already rising prices even further.

The logistics sector generally expects existing problems to intensify. The Port of Hamburg expects that Russian ships will soon no longer be allowed to dock in the EU. The railway connection along the new Silk Road to China is also interrupted or at least partially impaired. Road transport is also suffering. The war in Ukraine is increasing the shortage of truck drivers.

From a European perspective, however, the general competitive disadvantage for EU airlines weighs even more heavily. This is because Asian carriers are still able to cross Russian airspace. “Air China or Cathay Pacific fly practically the same old routes with a small detour around the actual conflict area,” says Großbongardt. Lufthansa, Air France-KLM, and British Airlines, on the other hand, have to take a huge detour.

Aviation expert Großbongardt does not expect any increased risk of incidents on the routes that remain open to Asian operators. Admittedly, civilian aircraft have been hit throughout aviation history. But in the current situation, aircraft will widely steer clear of the combat zones. However, these are distances of more than 1,000 kilometers – the equivalent of the distance between Frankfurt and Rome. No surface-to-air missile will stray that far.

Russian state-owned airline Aeroflot now has the biggest problem. In recent years, it has built up a strong reputation on Asian routes. Now it is being abruptly forced out of the market. Even if the flight bans last only a few weeks, the damage to its reputation will be considerable.

Großbongardt points out that the majority of Russia’s fleet is leased. It is owned by international providers. Since they will no longer receive money due to the financial embargo, they will cancel their contracts. Although a recall of the aircraft is not feasible at the moment, they can no longer be used. Their insurance coverage ends. All leases with Russian airlines would have to be canceled by March 28, Asian aircraft rental company BOC Aviation stated.

The pressure on Russia’s economy is growing. In addition to financial sanctions, Russia will no longer receive high-tech goods in the future. US President Joe Biden already spoke of sanctions on the day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that could permanently damage Russia’s economy. “Some of the most powerful impacts of our actions will come over time as we squeeze Russia’s access to finance and technology for strategic sectors of its economy and degrade its industrial capacity for years to come,” Biden said.

Since last weekend, it has been a done deal that not only the US but also Germany and several other countries will exclude a number of Russian banks and financial institutions from the international banking data system SWIFT. Financial experts around the world agree that this is the harshest sanction against Russia. Commodities from Russia can no longer be paid for. Trade with Western countries comes to a grinding halt, setting Russia back decades.

Foreign companies in Russia are likely to suffer losses in the billions if they have to restrict their economic activities in the country – or even abandon them altogether. Only China, as one of Russia’s few allies, wants to continue to maintain trade with Moscow.

In any case, China has still not taken a clear position against Putin’s war. Rather, Beijing’s Foreign Ministry’s statements sound monotonous and lack empathy for any values: “China opposes the use of sanctions to resolve issues and strongly condemns unilateral sanctions that have no basis in international law,” the Foreign Ministry quoted a statement by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on Sunday (China.Table reported).

The fear that Beijing’s trade with Russia could offset Western sanctions was already dispelled by the US government’s press secretary. “China cannot cover Russia for the impact caused by the US and European sanctions”, said Jen Psaki.

Her argument: China and Russia’s share of the global economy are far smaller than that of the G-7 countries, which include the US and Germany. According to World Bank figures, China and Russia accounted for 17.3 percent and 1.7 percent, respectively, of global GDP in 2020, compared to 45.8 percent of the G-7 countries.

Economic sanctions primarily involve semiconductors, computers, mobile phones, or high-tech commodities that Russia requires to “modernize its economy”, as EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen puts it. Accordingly, it is also clear that technology that could be directly used in the military sector or to support it will hardly be allowed to be exported to Russia in the future.

But how effective will the West’s high-tech sanctions be? The problem is quickly identified: It is China, which is one of the world’s leading producers of electronics, machinery, and other industrial goods. Around 70 percent of Russia’s chips are sourced from China. In return, Russia supplies power and food to China.

But the US is a leader in chip design and still holds the most patents in the sector. Whereas China is only one of many chip production sites. And, the fact that chips designed in the US are not delivered from China to Russia is ensured by the Foreign Product Direct Rule (FPDR) of the US government. This is because the FPDR indirectly imposes export restrictions on producers: If production depends significantly on US products, such as software, components, or chips, the final products also fall under the sanctions regime and require a separate US export license (Europe.Table reported).

“The actions of the Trump administration against Huawei could serve as a blueprint. There, the so-called Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) was applied. What is special about it, is its scope: It also affects technology produced abroad that contains a certain percentage of US technologies or was produced with the help of US software or equipment,” Sophie-Charlotte Fischer, a scientist at the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich and a specialist in sanctions regimes for high technologies, told Europe.Table.

Nevertheless, the US Semiconductor Association (SIA) does not see severe financial harm to the semiconductor sector from tech sanctions in general. “Russia [is] not a significant direct consumer of semiconductors,” says John Neuffer, CEO of SIA. Russia accounts for a mere 0.1 percent of global chip acquisitions, according to SIA data. US research company IDC also calculates that the Russian chip market has a trade value of only $50 billion in a global industry of $4.5 trillion.

Paul Triolo, head of technology policy at consulting firm Albright Stonebridge Group, told Politico that, while he is convinced China cannot cover Russia’s demand for advanced chips, he noted that Chinese companies have recently positioned themselves well enough to replace US or European cloud services and enterprise software.

And this option also poses difficult choices for both Beijing and Moscow: After all, such a step could make China a target for sanctions from Washington. Moreover, the People’s Republic itself is still dependent on chip imports, as the country is not yet able to manufacture them on its own (China.Table reported).

At the same time, the Russian government and its security apparatus have significant reservations about utilizing Chinese network technology and thus making themselves dependent. “The question is how dependent Russia wants to become on crucial Chinese technologies,” says Sophie-Charlotte Fischer, a specialist on sanctions regimes for high technologies (Europe.Table reported).

Just over a week after Russia launched its aggression against Ukraine, Beijing is still maintaining its political balancing act. China’s Foreign Ministry rejected sanctions against Russia after Western countries excluded some Russian banks from the international Swift payment system. “China does not support the use of sanctions to solve problems and is opposed to unilateral sanctions that have no basis in international law,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said on Monday.

China and Russia will “continue regular trade cooperation based on the spirit of mutual respect and equality, equality and mutual benefit,” Wang said. Wang did not directly address questions at the press conference in Beijing about how Swift sanctions might affect bilateral trade with Russia or whether China would increase purchases of Russian commodities such as gas and oil. He reiterated that, as NATO expands eastward, Russia’s concerns about security must be taken seriously and problems adequately resolved.

Wang stressed that China and Russia are “strategic partners” but not “allies”. China decides its position and policy on a case-by-case basis, Wang said. He also rejected the US’ call to designate the Russian invasion of Ukraine as such and condemn it.

Meanwhile, CCP media shared a statement from the Russian embassy in Beijing, BBC correspondent Stephen McDonell reported on Twitter. The statement said the Russian military’s invasion was based on the fact that “neo-Nazis” had seized power in Ukraine in 2014 and that the government in Kyiv had launched a war against its own people. Russian President Vladimir Putin also spreads this narrative via Russian propaganda.

State broadcasters CGTN and CCTV also spread the narrative that the US had provoked Russia with a possible NATO expansion and was now profiting from the crisis. In civil society, however, a first public opposition to the war emerged. A group of alumni from elite educational institutions Tsinghua, Dashan, Fudan and Peking Universities spoke out against Russian aggression in an open letter. “We Resolutely Oppose the Russian Invasion of Ukraine,” the letter said.

After the evacuation of Chinese citizens in Ukraine was put on hold for security reasons, Poland is now providing aid: Chinese citizens can enter the EU country without Schengen visas and stay there for 15 days to safely arrange their return home, the Polish embassy in Beijing announced on Weibo. ari/rtr

Chinese social media are fighting cynical jokes and remarks about the war in Ukraine on their platforms. The short message service Weibo has deleted 1,400 comments and temporarily or permanently suspended 262 accounts since Friday. The reasons were inappropriate comments by users whose insipidity had damaged the reputation of the Chinese nation. In addition to Weibo, TikTok parent Douyin also took action. The company deleted 6,400 short videos and 1,600 live streams.

Some comments allegedly supported further acts of war, while others users hoped that “beautiful Ukrainian women” would now flee to China. State media quoted lawyers and scholars who criticized such comments, while suggesting that “anti-Chinese forces” had accelerated the spread via Chinese platforms. Accounts with a connection to Taiwan, in particular, were responsible for the momentum, the accusation goes.

The Global Times reported that Chinese students in Ukraine had faced hostility over the weekend, in part because of comments made on Chinese social media. grz

Hong Kong is considering a Covid lockdown for the duration of the announced mass testing in March. Until now, the authorities had opposed this idea. On Monday, a change of course followed. To benefit as much as possible from the widespread testing, “we must reduce the flow of people to a certain extent,” says health minister Sophia Chan. Citizens are urged not to leave their homes.

Chan announced that the situation would be closely monitored in order to decide whether people could continue to go to work and whether the stock exchange would remain open. When making decisions, Hong Kong authorities would take the opinion of experts from the People’s Republic of China into account. Since last Thursday, the freedom of movement of unvaccinated individuals has been drastically restricted.

The number of positive cases has been rising rapidly for weeks, reaching new highs every day. On Monday, nearly 34,500 new infections were reported, and 87 people died in connection with the virus within the past 24 hours. The number of fatalities has risen to 851. In order to stem the tide, all 7.5 million residents are to be tested three times over a maximum of 21 days in March, following the Chinese model.

Meanwhile, warnings are coming from the People’s Republic that the city’s local health system could soon be overwhelmed. According to a representative of China’s National Health Commission, 9,000 medical workers are on standby to help carry out testing in Hong Kong. The city government had already reserved 20,000 hotel beds last week to quarantine infected individuals (China.Table reported).

Government chief executive Carrie Lam has canceled her trip to the National People’s Congress next weekend due to the tense situation. She announced that she wanted to focus entirely on crisis management within the city. grz

China is accelerating its program to support startups in industries such as chip manufacturing and biotechnology. About 3,000 startups will be designated as “Little Giant” this year to help drive local innovation, Xiao Yaqing, Minister of Industry and Information Technology, said in Beijing on Monday. This would bring the total number of government-backed startups to nearly 8,000. These companies are mainly located in the semiconductor, machinery, and pharmaceutical sectors. The program is part of China’s policy to challenge the US lead in these technologies.

The “Little Giant” designation provides startups with financial support from the government, such as tax cuts or more liberal loans. It also signals investors and employees that this company enjoys Beijing’s special support. Little Giant’s innovation capability, as well as its sales and profitability, have “improved significantly” compared to other companies, Xiao said.

The government announced its intention to help create a better supply chain environment for these companies, Xiao added. The aim is to encourage large companies to make their markets, technologies, and talents accessible to such startups. rad

On Monday, US cybersecurity company Symantec announced the discovery of a new Chinese hacking tool. It stated that the US government had been informed about the malware a month ago. Symantec calls the new tool “Daxin”.

“While the most recent known attacks involving Daxin occurred in November 2021, the earliest known sample of the malware dates from 2013,” Symantec’s report states. According to the report, Daxin targets have already included key non-Western government agencies in Asia and Africa, including some ministries of justice. “Daxin can be controlled from anywhere in the world once a computer is actually infected,” a Symantec spokesman told Reuters. “That’s what raises the bar from malware that we see coming out of groups operating from China.”

“It’s something we haven’t seen before,” said Clayton Romans, associate director with the U.S. Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). “This is the exact type of information we’re hoping to receive.” Romans stated that he was aware of affected organizations in the US, but there were infections around the world that the US government is helping to notify.

The Chinese side merely stated that China is also a victim of hacking and rejects all forms of cyberattacks. rad

“In China, it is frowned upon to speak positively about oneself,” says Christoph Schmitt. So he tells what others say about him: He is said to be an unusual business lawyer. That’s because he’s not only interested in legal paragraphs, he’s also a good listener and finds solutions. All these qualities are important when he drafts joint venture agreements between German and Chinese companies, for example. “After Xi Jinping’s monetary policy made foreign investments more difficult, numerous cooperations have taken their place, which have to be negotiated. In addition to regulating two-way German-Chinese trading, this is my daily doing,” says the 58-year-old.

Together with his seven-member strong German-Chinese team, Schmitt advises German companies that seek to gain a foothold in China – as well as Chinese companies that want to expand to Germany and thus often find their way into European trade. This involves a wide variety of questions, for example: Can a Chinese person who does not live in Germany become the managing director of a German company? What permits does he need to do business here? What aspects of competition law and what technical requirements does he have to take into account if he wants to launch products on the European market. And what kind of distribution system is recommended for a German entrepreneur in China?

Schmitt is very familiar with Chinese cultural customs, as he has been in the China business for 25 years and has already visited China more than 80 times. “German-Chinese business doesn’t happen by inviting German entrepreneurs to Shanghai and putting them in a restaurant with Chinese entrepreneurs,” he explains. Instead, it comes down to individuals who can carefully familiarize the two cultures with each other, he says. “Chinese entrepreneurs don’t talk business directly, but first ask where the other person’s daughter goes to school, which German entrepreneurs might find offensive,” he explains.

Another example: For German entrepreneurs, a letter of intent is a non-binding declaration without consequences that is commonly signed, while Chinese entrepreneurs perceive such a paper to be much more binding and handle it with greater caution. Schmitt sees his task in explaining the mindset of the opposite party and providing an understanding of what a letter of intent contains in legal terms and what reasons speak for or against signing such a document for both parties.

Naturally, Schmitt has to be familiar with Chinese politics and law, because both have a strong influence on what is possible for his clients from an entrepreneurial perspective. His excellent network helps him here, he says, both with the team of Chinese lawyers in his own firm and with cooperation partners in China: “We keep each other informed about new legislation and the latest case law. And we simply call each other when questions arise.”

These conversations usually take place in German or English. “It’s simply incredible how quickly the Chinese learn German. But learning Chinese is very difficult,” admits the family man. In a hotel, he can communicate more or less in Mandarin, but his Chinese skills are not yet sufficient for complex negotiations.

Incidentally, it was a client who took Schmitt, a native of the German city of Düsseldorf, to China decades ago. “He wanted to sell exhaust gas disposal systems for the microchip industry, and companies in Taiwan and China were already more advanced at that time,” he recalls. At that time, he founded a company in Hong Kong. Later, he began trading with mainland China. He established his first sales satellites, which enabled Schmitt to make his first contact with Chinese state-owned enterprises. From the 2000s onwards, a free middle class finally developed in China, which also showed interest in Europe and appreciated the work of the German lawyer as did German companies, which he successfully positioned in China. Janna Degener-Storr

Sebastian Moerler joined the Shanghai office of Boston Consulting Group in February. He is a member of the Principal Investors & Private Equity (PIPE) taskforce and leads commercial due diligence, strategy and portfolio optimization projects for large and mid-cap financial investors.

The 38th Ice Festival in Harbin has come to an end. For nearly two months, tourists and visitors were able to stroll through a city of ice. Now, spring can finally arrive, along with the warming sun.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine continues to cast a shadow on everything else. Among other things, Europe and Russia have now closed-off each other’s airspace. The impacts are obvious: longer flight times, higher costs, and additional pressure on already heavily strained supply chains. After all, the air route to China has suddenly been extended by 1,200 kilometers. But even in this dispute, the old truism applies: When two quarrel, a third rejoices. Finn Mayer-Kuckuk explains why this third party is mostly Air China Cargo in this case, and how Asian airlines benefit from the European-Russian sanctions spiral.

Our second analysis of today also examines the consequences of European sanctions against Russia. Specifically, it is about punitive measures in the high-tech sector. The focus is primarily on semiconductors, computers, mobile phones, and other high-tech commodities that Russia urgently requires to modernize its economy. Some Chinese semiconductors manufacturers now may hope to fill the gaps in the Russian tech market. But it will not be so easy. Ning Wang shows that both Beijing and Moscow should think carefully about undermining Europe’s high-tech sanctions this way.

Russian airspace has been closed to aircraft from the EU since Monday. Over the weekend, two Lufthansa flights to Seoul and to Tokyo were already forced to turn back mid-flight and return to Munich and Frankfurt, respectively. “Due to the ongoing dramatic developments in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Lufthansa will no longer use Russian airspace,” a spokeswoman said on Monday.

Lufthansa alone is now canceling 30 eastbound flights for which no other routes could be found or are no longer profitable due to lack of demand. The remaining aircraft are operating alternative routes south of Russian airspace. Swiss, the Group’s subsidiary, is also no longer flying over Russia. Over the weekend, the company still declared that it would be able to continue its Far East operations as usual due to Switzerland’s different rules.

This means that China is still accessible. However, the route will be around 1,200 kilometers, or one and a half hours, longer. “In terms of range, this is not a problem for the aircraft in use today,” says aviation expert Heinrich Großbongardt of the consultancy Expairtise in Hamburg. Flight service consultants did invest considerable extra work over the weekend to draw up the new schedules and routes. But flights to Asia can at least continue. A double blessing in disguise: Because of the pandemic, the routes were hardly busy anyway, which now makes it easier to manage the new situation. In normal operations, this would have led to chaos, believes Großbongardt.

Cargo routes are now more affected, which may also have an impact on supply chains. “Lufthansa Cargo will fly around Russian airspace via a southern routing,” the spokeswoman said. “This will make adjustments to the flight schedule and payload unavoidable.” In other words, aircraft won’t be able to carry as much cargo and will arrive later. By circumventing Russian airspace, most cargo flights to Asia are no longer economical, said Topi Manner, Finnair’s chief executive.

Großbongardt expects rising freight traffic costs as a result. Fully loaded cargo planes have less range. Asian flights then have to stop over in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, for example, for refueling. All this costs money and time. This will likely have an impact on shipping charges, pushing up already rising prices even further.

The logistics sector generally expects existing problems to intensify. The Port of Hamburg expects that Russian ships will soon no longer be allowed to dock in the EU. The railway connection along the new Silk Road to China is also interrupted or at least partially impaired. Road transport is also suffering. The war in Ukraine is increasing the shortage of truck drivers.

From a European perspective, however, the general competitive disadvantage for EU airlines weighs even more heavily. This is because Asian carriers are still able to cross Russian airspace. “Air China or Cathay Pacific fly practically the same old routes with a small detour around the actual conflict area,” says Großbongardt. Lufthansa, Air France-KLM, and British Airlines, on the other hand, have to take a huge detour.

Aviation expert Großbongardt does not expect any increased risk of incidents on the routes that remain open to Asian operators. Admittedly, civilian aircraft have been hit throughout aviation history. But in the current situation, aircraft will widely steer clear of the combat zones. However, these are distances of more than 1,000 kilometers – the equivalent of the distance between Frankfurt and Rome. No surface-to-air missile will stray that far.

Russian state-owned airline Aeroflot now has the biggest problem. In recent years, it has built up a strong reputation on Asian routes. Now it is being abruptly forced out of the market. Even if the flight bans last only a few weeks, the damage to its reputation will be considerable.

Großbongardt points out that the majority of Russia’s fleet is leased. It is owned by international providers. Since they will no longer receive money due to the financial embargo, they will cancel their contracts. Although a recall of the aircraft is not feasible at the moment, they can no longer be used. Their insurance coverage ends. All leases with Russian airlines would have to be canceled by March 28, Asian aircraft rental company BOC Aviation stated.

The pressure on Russia’s economy is growing. In addition to financial sanctions, Russia will no longer receive high-tech goods in the future. US President Joe Biden already spoke of sanctions on the day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that could permanently damage Russia’s economy. “Some of the most powerful impacts of our actions will come over time as we squeeze Russia’s access to finance and technology for strategic sectors of its economy and degrade its industrial capacity for years to come,” Biden said.

Since last weekend, it has been a done deal that not only the US but also Germany and several other countries will exclude a number of Russian banks and financial institutions from the international banking data system SWIFT. Financial experts around the world agree that this is the harshest sanction against Russia. Commodities from Russia can no longer be paid for. Trade with Western countries comes to a grinding halt, setting Russia back decades.

Foreign companies in Russia are likely to suffer losses in the billions if they have to restrict their economic activities in the country – or even abandon them altogether. Only China, as one of Russia’s few allies, wants to continue to maintain trade with Moscow.

In any case, China has still not taken a clear position against Putin’s war. Rather, Beijing’s Foreign Ministry’s statements sound monotonous and lack empathy for any values: “China opposes the use of sanctions to resolve issues and strongly condemns unilateral sanctions that have no basis in international law,” the Foreign Ministry quoted a statement by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on Sunday (China.Table reported).

The fear that Beijing’s trade with Russia could offset Western sanctions was already dispelled by the US government’s press secretary. “China cannot cover Russia for the impact caused by the US and European sanctions”, said Jen Psaki.

Her argument: China and Russia’s share of the global economy are far smaller than that of the G-7 countries, which include the US and Germany. According to World Bank figures, China and Russia accounted for 17.3 percent and 1.7 percent, respectively, of global GDP in 2020, compared to 45.8 percent of the G-7 countries.

Economic sanctions primarily involve semiconductors, computers, mobile phones, or high-tech commodities that Russia requires to “modernize its economy”, as EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen puts it. Accordingly, it is also clear that technology that could be directly used in the military sector or to support it will hardly be allowed to be exported to Russia in the future.

But how effective will the West’s high-tech sanctions be? The problem is quickly identified: It is China, which is one of the world’s leading producers of electronics, machinery, and other industrial goods. Around 70 percent of Russia’s chips are sourced from China. In return, Russia supplies power and food to China.

But the US is a leader in chip design and still holds the most patents in the sector. Whereas China is only one of many chip production sites. And, the fact that chips designed in the US are not delivered from China to Russia is ensured by the Foreign Product Direct Rule (FPDR) of the US government. This is because the FPDR indirectly imposes export restrictions on producers: If production depends significantly on US products, such as software, components, or chips, the final products also fall under the sanctions regime and require a separate US export license (Europe.Table reported).

“The actions of the Trump administration against Huawei could serve as a blueprint. There, the so-called Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) was applied. What is special about it, is its scope: It also affects technology produced abroad that contains a certain percentage of US technologies or was produced with the help of US software or equipment,” Sophie-Charlotte Fischer, a scientist at the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich and a specialist in sanctions regimes for high technologies, told Europe.Table.

Nevertheless, the US Semiconductor Association (SIA) does not see severe financial harm to the semiconductor sector from tech sanctions in general. “Russia [is] not a significant direct consumer of semiconductors,” says John Neuffer, CEO of SIA. Russia accounts for a mere 0.1 percent of global chip acquisitions, according to SIA data. US research company IDC also calculates that the Russian chip market has a trade value of only $50 billion in a global industry of $4.5 trillion.

Paul Triolo, head of technology policy at consulting firm Albright Stonebridge Group, told Politico that, while he is convinced China cannot cover Russia’s demand for advanced chips, he noted that Chinese companies have recently positioned themselves well enough to replace US or European cloud services and enterprise software.

And this option also poses difficult choices for both Beijing and Moscow: After all, such a step could make China a target for sanctions from Washington. Moreover, the People’s Republic itself is still dependent on chip imports, as the country is not yet able to manufacture them on its own (China.Table reported).

At the same time, the Russian government and its security apparatus have significant reservations about utilizing Chinese network technology and thus making themselves dependent. “The question is how dependent Russia wants to become on crucial Chinese technologies,” says Sophie-Charlotte Fischer, a specialist on sanctions regimes for high technologies (Europe.Table reported).

Just over a week after Russia launched its aggression against Ukraine, Beijing is still maintaining its political balancing act. China’s Foreign Ministry rejected sanctions against Russia after Western countries excluded some Russian banks from the international Swift payment system. “China does not support the use of sanctions to solve problems and is opposed to unilateral sanctions that have no basis in international law,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said on Monday.

China and Russia will “continue regular trade cooperation based on the spirit of mutual respect and equality, equality and mutual benefit,” Wang said. Wang did not directly address questions at the press conference in Beijing about how Swift sanctions might affect bilateral trade with Russia or whether China would increase purchases of Russian commodities such as gas and oil. He reiterated that, as NATO expands eastward, Russia’s concerns about security must be taken seriously and problems adequately resolved.

Wang stressed that China and Russia are “strategic partners” but not “allies”. China decides its position and policy on a case-by-case basis, Wang said. He also rejected the US’ call to designate the Russian invasion of Ukraine as such and condemn it.

Meanwhile, CCP media shared a statement from the Russian embassy in Beijing, BBC correspondent Stephen McDonell reported on Twitter. The statement said the Russian military’s invasion was based on the fact that “neo-Nazis” had seized power in Ukraine in 2014 and that the government in Kyiv had launched a war against its own people. Russian President Vladimir Putin also spreads this narrative via Russian propaganda.

State broadcasters CGTN and CCTV also spread the narrative that the US had provoked Russia with a possible NATO expansion and was now profiting from the crisis. In civil society, however, a first public opposition to the war emerged. A group of alumni from elite educational institutions Tsinghua, Dashan, Fudan and Peking Universities spoke out against Russian aggression in an open letter. “We Resolutely Oppose the Russian Invasion of Ukraine,” the letter said.

After the evacuation of Chinese citizens in Ukraine was put on hold for security reasons, Poland is now providing aid: Chinese citizens can enter the EU country without Schengen visas and stay there for 15 days to safely arrange their return home, the Polish embassy in Beijing announced on Weibo. ari/rtr

Chinese social media are fighting cynical jokes and remarks about the war in Ukraine on their platforms. The short message service Weibo has deleted 1,400 comments and temporarily or permanently suspended 262 accounts since Friday. The reasons were inappropriate comments by users whose insipidity had damaged the reputation of the Chinese nation. In addition to Weibo, TikTok parent Douyin also took action. The company deleted 6,400 short videos and 1,600 live streams.

Some comments allegedly supported further acts of war, while others users hoped that “beautiful Ukrainian women” would now flee to China. State media quoted lawyers and scholars who criticized such comments, while suggesting that “anti-Chinese forces” had accelerated the spread via Chinese platforms. Accounts with a connection to Taiwan, in particular, were responsible for the momentum, the accusation goes.

The Global Times reported that Chinese students in Ukraine had faced hostility over the weekend, in part because of comments made on Chinese social media. grz

Hong Kong is considering a Covid lockdown for the duration of the announced mass testing in March. Until now, the authorities had opposed this idea. On Monday, a change of course followed. To benefit as much as possible from the widespread testing, “we must reduce the flow of people to a certain extent,” says health minister Sophia Chan. Citizens are urged not to leave their homes.

Chan announced that the situation would be closely monitored in order to decide whether people could continue to go to work and whether the stock exchange would remain open. When making decisions, Hong Kong authorities would take the opinion of experts from the People’s Republic of China into account. Since last Thursday, the freedom of movement of unvaccinated individuals has been drastically restricted.

The number of positive cases has been rising rapidly for weeks, reaching new highs every day. On Monday, nearly 34,500 new infections were reported, and 87 people died in connection with the virus within the past 24 hours. The number of fatalities has risen to 851. In order to stem the tide, all 7.5 million residents are to be tested three times over a maximum of 21 days in March, following the Chinese model.

Meanwhile, warnings are coming from the People’s Republic that the city’s local health system could soon be overwhelmed. According to a representative of China’s National Health Commission, 9,000 medical workers are on standby to help carry out testing in Hong Kong. The city government had already reserved 20,000 hotel beds last week to quarantine infected individuals (China.Table reported).

Government chief executive Carrie Lam has canceled her trip to the National People’s Congress next weekend due to the tense situation. She announced that she wanted to focus entirely on crisis management within the city. grz

China is accelerating its program to support startups in industries such as chip manufacturing and biotechnology. About 3,000 startups will be designated as “Little Giant” this year to help drive local innovation, Xiao Yaqing, Minister of Industry and Information Technology, said in Beijing on Monday. This would bring the total number of government-backed startups to nearly 8,000. These companies are mainly located in the semiconductor, machinery, and pharmaceutical sectors. The program is part of China’s policy to challenge the US lead in these technologies.

The “Little Giant” designation provides startups with financial support from the government, such as tax cuts or more liberal loans. It also signals investors and employees that this company enjoys Beijing’s special support. Little Giant’s innovation capability, as well as its sales and profitability, have “improved significantly” compared to other companies, Xiao said.

The government announced its intention to help create a better supply chain environment for these companies, Xiao added. The aim is to encourage large companies to make their markets, technologies, and talents accessible to such startups. rad

On Monday, US cybersecurity company Symantec announced the discovery of a new Chinese hacking tool. It stated that the US government had been informed about the malware a month ago. Symantec calls the new tool “Daxin”.

“While the most recent known attacks involving Daxin occurred in November 2021, the earliest known sample of the malware dates from 2013,” Symantec’s report states. According to the report, Daxin targets have already included key non-Western government agencies in Asia and Africa, including some ministries of justice. “Daxin can be controlled from anywhere in the world once a computer is actually infected,” a Symantec spokesman told Reuters. “That’s what raises the bar from malware that we see coming out of groups operating from China.”

“It’s something we haven’t seen before,” said Clayton Romans, associate director with the U.S. Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). “This is the exact type of information we’re hoping to receive.” Romans stated that he was aware of affected organizations in the US, but there were infections around the world that the US government is helping to notify.

The Chinese side merely stated that China is also a victim of hacking and rejects all forms of cyberattacks. rad

“In China, it is frowned upon to speak positively about oneself,” says Christoph Schmitt. So he tells what others say about him: He is said to be an unusual business lawyer. That’s because he’s not only interested in legal paragraphs, he’s also a good listener and finds solutions. All these qualities are important when he drafts joint venture agreements between German and Chinese companies, for example. “After Xi Jinping’s monetary policy made foreign investments more difficult, numerous cooperations have taken their place, which have to be negotiated. In addition to regulating two-way German-Chinese trading, this is my daily doing,” says the 58-year-old.

Together with his seven-member strong German-Chinese team, Schmitt advises German companies that seek to gain a foothold in China – as well as Chinese companies that want to expand to Germany and thus often find their way into European trade. This involves a wide variety of questions, for example: Can a Chinese person who does not live in Germany become the managing director of a German company? What permits does he need to do business here? What aspects of competition law and what technical requirements does he have to take into account if he wants to launch products on the European market. And what kind of distribution system is recommended for a German entrepreneur in China?

Schmitt is very familiar with Chinese cultural customs, as he has been in the China business for 25 years and has already visited China more than 80 times. “German-Chinese business doesn’t happen by inviting German entrepreneurs to Shanghai and putting them in a restaurant with Chinese entrepreneurs,” he explains. Instead, it comes down to individuals who can carefully familiarize the two cultures with each other, he says. “Chinese entrepreneurs don’t talk business directly, but first ask where the other person’s daughter goes to school, which German entrepreneurs might find offensive,” he explains.

Another example: For German entrepreneurs, a letter of intent is a non-binding declaration without consequences that is commonly signed, while Chinese entrepreneurs perceive such a paper to be much more binding and handle it with greater caution. Schmitt sees his task in explaining the mindset of the opposite party and providing an understanding of what a letter of intent contains in legal terms and what reasons speak for or against signing such a document for both parties.

Naturally, Schmitt has to be familiar with Chinese politics and law, because both have a strong influence on what is possible for his clients from an entrepreneurial perspective. His excellent network helps him here, he says, both with the team of Chinese lawyers in his own firm and with cooperation partners in China: “We keep each other informed about new legislation and the latest case law. And we simply call each other when questions arise.”

These conversations usually take place in German or English. “It’s simply incredible how quickly the Chinese learn German. But learning Chinese is very difficult,” admits the family man. In a hotel, he can communicate more or less in Mandarin, but his Chinese skills are not yet sufficient for complex negotiations.

Incidentally, it was a client who took Schmitt, a native of the German city of Düsseldorf, to China decades ago. “He wanted to sell exhaust gas disposal systems for the microchip industry, and companies in Taiwan and China were already more advanced at that time,” he recalls. At that time, he founded a company in Hong Kong. Later, he began trading with mainland China. He established his first sales satellites, which enabled Schmitt to make his first contact with Chinese state-owned enterprises. From the 2000s onwards, a free middle class finally developed in China, which also showed interest in Europe and appreciated the work of the German lawyer as did German companies, which he successfully positioned in China. Janna Degener-Storr

Sebastian Moerler joined the Shanghai office of Boston Consulting Group in February. He is a member of the Principal Investors & Private Equity (PIPE) taskforce and leads commercial due diligence, strategy and portfolio optimization projects for large and mid-cap financial investors.

The 38th Ice Festival in Harbin has come to an end. For nearly two months, tourists and visitors were able to stroll through a city of ice. Now, spring can finally arrive, along with the warming sun.