Olaf Scholz made his inaugural visit to Rome yesterday. There, the German Chancellor not only praised Prime Minister Mario Draghi’s competence but also agreed on a joint “action plan” for better cooperation, initially without giving details.

Who gets to discuss which parts of European climate policy is decided not least by Charles Michel. The President of the European Council put the energy crisis on the agenda of the heads of state and government, as he did at the summit last Thursday. The technical elements of the Fit for 55 package, on the other hand, are reserved for the less politically charged and technically experienced Environment Council.

Climate measures were also on the agenda there yesterday. Lukas Scheid took a closer look at how the member states want to cushion the social impact of European climate policy. But the financing is still largely unresolved. And some member states simply want less climate policy – then there would be no need for social compensation.

Following the meeting, European Commissioner for Environment Virginijus Sinkevičius revealed what the College of Commissioners will “most likely” deal with before the Christmas break: the delegated act on climate taxonomy. The confidential draft will then be submitted to experts for evaluation before the authority decides and publishes it. Read what this means for the Christmas plans of Olaf Scholz and the rest of us in Apéro.

On Wednesday, the authority is also expected to present the new climate and energy aid guidelines, known in the jargon as CEEAG. In today’s guest article, Michael Niese of the Wirtschaftsvereinigung Metalle explains why the competition authorities should not throw out the baby with the bathwater.

In any case, Germany’s and Europe’s climate targets will hardly be achievable without a massive expansion of solar energy. But this brings with it human rights problems, as the example of Xinjiang shows: From the region, where Beijing’s rulers brutally suppress the minority of the Uyghurs, comes about half of a raw material important for the production of solar panels. Nico Beckert has analyzed the trade-off between clean supply chains and clean sources of electricity.

Batteries should also become cleaner: The new Federal Minister of the Environment, Steffi Lemke (Greens), has called for an ambitious approach at EU level. Timo Landenberger explains what this means and how the goals are to be achieved.

Health is on everyone’s lips again these days – and the EU is also taking on a bigger role in the pandemic than it has been given so far by the member states. The new EU health authority Hera has now defined their rights to have a say, according to Eugenie Ankowitsch’s report.

In Brussels, he is considered influential, and now a successor has been found for Guntram Wolff, who is leaving in 2022, as head of the think tank Bruegel. It’s likely, but not yet clear, whether the Maltese Roberta Metsola will be the next president of the European Parliament. While the Liberals have already asked her for an interview, the Social Democrats in the EP have now announced a hearing for January – and among the Greens, a revolutionary mood is spreading.

The Fit for 55 package presented by the EU Commission in July contains a proposal to minimize the negative impact of climate protection measures on the civilian population. The Social Climate Fund (SCF) aims to support vulnerable households and micro-enterprises whose livelihoods would be threatened by the measures taken.

The Commission wants to make €72.2 billion available for this purpose from 2025, financed by expanding the emissions trading system to include the buildings and transport sectors – also known as ETS 2. Thus, part of the profits from the sale of emission rights would go either as direct payments to private households or as investment aid for emission avoidance to companies. The idea behind investment subsidies: Those who avoid emissions save cash, as emissions become more expensive due to a CO2 price.

In principle, the EU states agree that the social impact of climate policy must be kept as low as possible and that a support fund can achieve this. However, the Commission’s funding plans so far are bitterly resented by some member states. Extending the ETS to buildings and transport is not seen as the most popular part of the Fit for 55 package. Poland would prefer to scrap ETS 2 altogether. The government in Warsaw fears additional burdens for particularly vulnerable groups. However, Poland would like to have the climate social fund after all and demands that it not be linked to the revenues from ETS 2.

Austria’s Minister of the Environment Leonore Gewessler, on the other hand, emphasized this link at the Environment Council. Vienna supports the extension of the ETS to buildings and transport on the condition that ambitious standards are introduced for both sectors that lead to structural emission reductions and that consumers are not the only ones burdened by the CO2 price. Austria was rather skeptical about the exact design of the SCF, as it would mean an intervention in the EU’s multiannual financial framework and would require the member states’ own funds. The Commission proposal provides for the member states to make available the same amount as the EU Commission – i.e., an additional €72.2 billion. Gewessler suggested thinking about an “alternative financial construction” of the SCF.

The latter would also meet with approval in Budapest. The Hungarian government doesn’t want a social climate fund at all but would rather see the EU’s modernization fund strengthened with additional financial resources. But if the SCF does see the light of day, the member states’ flat-rate contribution of 50 percent should not be applied. Instead, Hungary said yesterday in Brussels, an individual national contribution should be made based on the level of development of the respective country. Budapest also wants to prevent a CO2 price for buildings and transport if possible.

The Czech Republic even fears for the acceptance of European climate policy among the population if prices in the transport and building sector rise due to ETS expansion. The SCF could be a solution, but the Commission’s proposal sounds very administration-intensive. Moreover, it is not known whether the SCF would actually be able to cushion the social challenges posed by rising CO2 prices, the Christian Democrat Czech Minister of the Environment Anna Hubáčková, who only took office last Friday, said on Monday.

Germany is considered the most vocal supporter of the Commission’s plans for ETS expansion. At the Environment Council, State Secretary Patrick Graichen from the new Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Change represented the German position in the debate on the Fit for 55 package (Federal Minister of the Environment Steffi Lemke spoke for the issues concerning nature and consumer protection).

Graichen stressed that the new federal government would bring new momentum to climate policy and explained that Germany is in favor of a CO2 minimum price of €60 per tonne, which would also apply to ETS 2. “The prices have to point in the right direction so that you can actually achieve the emission reductions that are needed,” said the State Secretary, explaining the demand. Graichen pleaded overall for an ambitious package with social compensation. How the social compensation could look like still has to be discussed.

The Commissioner responsible for the Fit for 55 projects and Executive Vice-President Frans Timmermans even showed himself open to alternatives to ETS expansion at the end of the exchange of views. However, he also made clear that these alternatives would have to put Europe just as much on track to meet the climate targets for 2030 and 2050. Timmermans defended the expansion of the ETS by saying that emissions are still rising only in the transport sector and falling too slowly in the buildings sector. The ETS has shown that it works and should therefore be extended. However, it is equally up to the Commission and the member states to ensure that no one is left behind as a result of the European climate plans, Timmermans said.

There were no negotiations at the Environment Council, so from January, it will be up to the French Presidency to unite the member states in their differing views on how the social balance to the climate protection plans will be shaped.

The new federal government has a number of plans for the expansion of renewable powers. It wants to mount solar power on “all suitable roofs”. By 2030, “around 200 gigawatts” of photovoltaic capacity are to be achieved. This means a quadrupling of the current capacity. To achieve this, the traffic light coalition wants to remove many “hurdles to expansion”. This is what the coalition agreement says.

The supply chain of the solar industry is one major hurdle that is not mentioned. A large part of the basic material of solar cells, polysilicon, is produced in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. However, there are accusations that this polysilicon is produced through forced labor by the Uyghur ethnic group. This poses considerable problems if ethical standards are to apply to this supply chain in the future.

Recently, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock announced a clearer policy against human rights violations in China. “If products from regions like Xinjiang, where forced labor is common practice, are blocked, that’s a big problem for an exporting country like China,” she said in an interview with taz and China.Table.

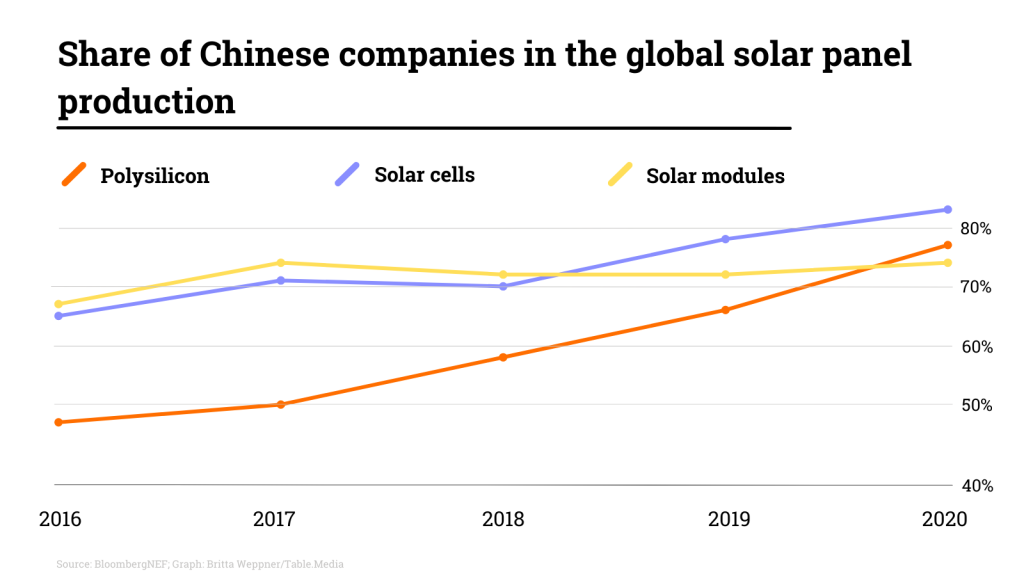

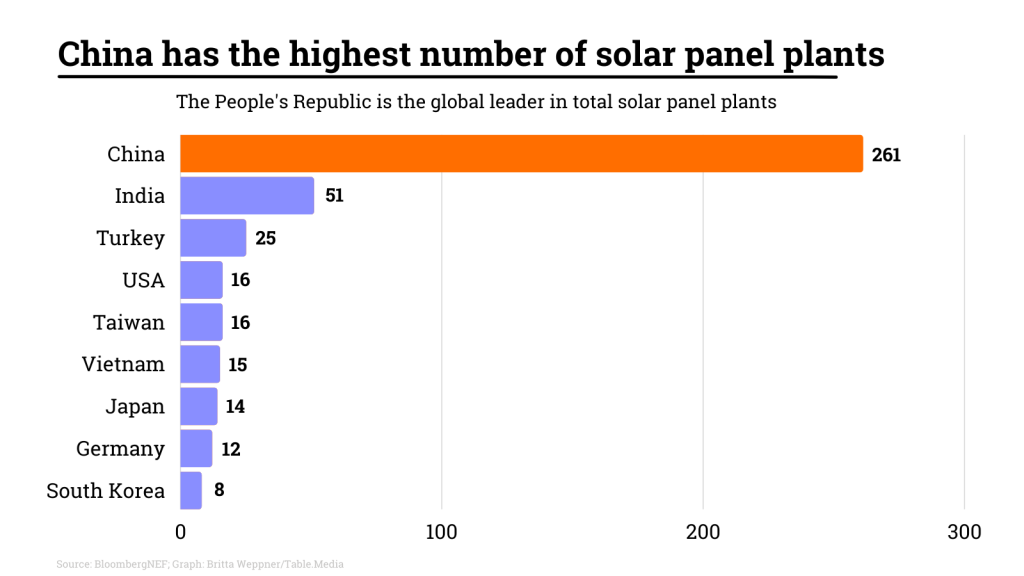

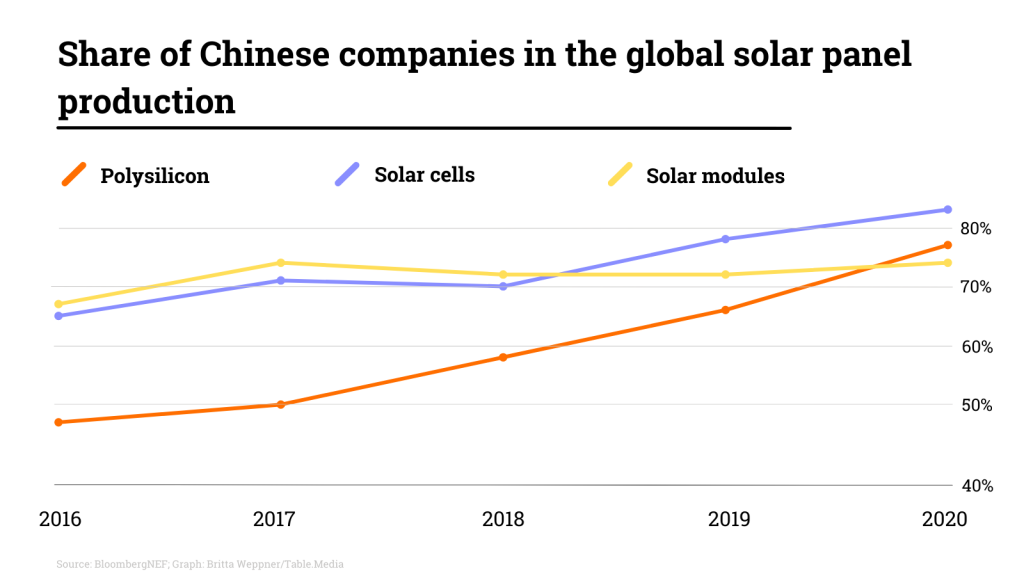

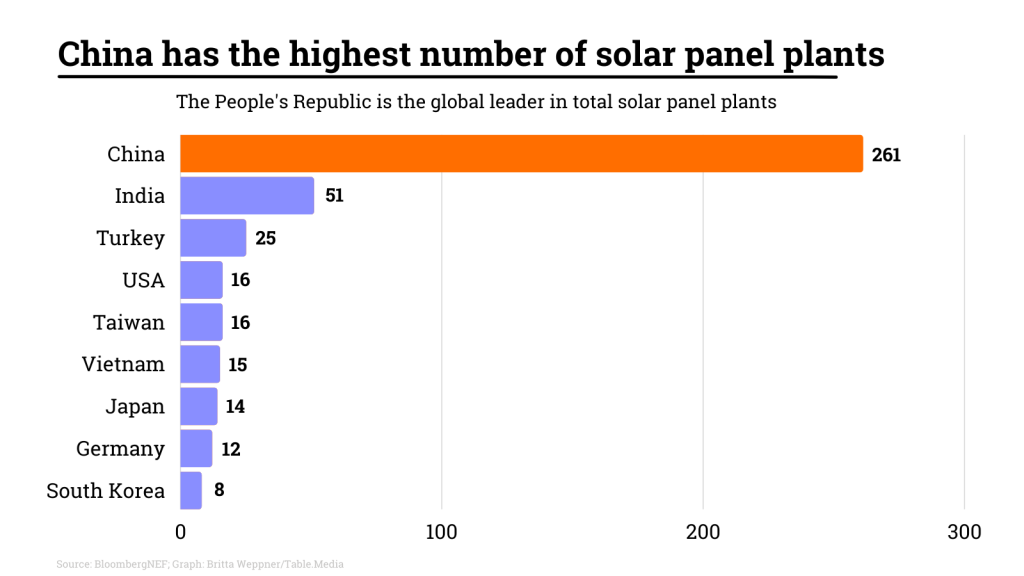

But it is not only China, who would then face a problem. The expansion of solar energy in Germany could also come to a grinding halt. Much of the polysilicon is processed directly in China. The People’s Republic is the global market leader in the solar sector and dominates all production steps. Worldwide, three out of four solar modules and 83 percent of solar cells are produced in China. China dominates 77 percent of the global market for polysilicon. Xinjiang again plays a special role here. An estimated 50 percent of global polysilicon production is located in the western Chinese region.

Large amounts of power are required for the production of polysilicon and its precursor silicon metal. Xinjiang has an abundance of it. There is hardly any other part of the country where power and process heat for the production of polysilicon is so cheap. Four of the world’s largest manufacturers have factories in Xinjiang, according to an analysis by Bloomberg. Three producers have been accused of using forced labor in their factories.

The allegations are based on reports by consulting firms Horizon Advisory and S&P Global Market Intelligence, as well as research by Xinjiang researcher Adrian Zenz. They independently conclude that hundreds of forced laborers are involved in the production of polysilicon. A Bloomberg research team was denied access to the factories. The journalists have not been allowed to examine the production and interpret this as a sign that the manufacturers have something to hide.

Other experts, however, give the all-clear in part. True, China’s global market share looks very high on paper. But a large part of it remains domestic. No other country installs as many solar modules as China. A large part of the domestic production is therefore not exported in the first place.

Moreover, the other half of China’s production is produced outside Xinjiang. Together with manufacturing in other regions of the world, there are enough solar modules to meet demand. “The US and Europe together accounted for about 30 percent of new global PV installations in 2020,” says market observer Johannes Bernreuter of consulting firm Bernreuter Research. “So arithmetically, there is enough polysilicon for the US and Europe right now that is not affected by Xinjiang.”

Surprisingly, neither the EU’s statistical authority (Eurostat) nor the Federal Statistical Office have any data on how many solar cells and modules Germany imports from China.

But when Western buyers acquire solar cells and modules from China, they have so far been faced with a problem: Polysilicon from various sources is mixed during production. It could very well be that basic material from Xinjiang is also included, which was produced through forced labor. However, Chinese manufacturers are adapting to the needs of the West. Some companies are likely producing Xinjiang-free segments and using them in their solar modules for export to the US and Europe, Bernreuter explains. “They can also provide plausible documents that the solar modules and cells do not contain any primary products from Xinjiang.”

This could mean that material flows could simply be split: Xinjiang-free products are manufactured for export. Solar modules, whose raw material is produced through forced labor, continue to be installed in China due to the high domestic demand. Western sanctions and boycotts of polysilicon from Xinjiang would thus have little effect. Bernreuter criticizes: “To put it bluntly: The West eases its conscience, but the Uyghurs are not better off.” However, one should not underestimate sanctions as a political signal, Bernreuter adds.

Another problem in the solar supply chain is the basic material for polysilicon: so-called metallurgical-grade silicon. The Chinese manufacturers of this highly pure silicon have no interest in transparency. So importers can hardly be sure that no forced labor is involved in the production of metallurgical-grade silicon. This is the reason why some Western and Asian manufacturers of polysilicon have already terminated their business relations with the largest producer of metallurgical silicon, Hoshine Silicon from Xinjiang. In addition, the US Customs Service has taken action against Hoshine. There is information that the company uses forced labor, the agency said. Products from Hoshine are confiscated by customs at US ports.

However, this by no means resolves the situation. The US is currently discussing additional measures to exclude forced labor in Xinjiang in imported products. As these go far beyond current measures, it would further reduce the number of basic materials that can be imported legally. Recently, the US House of Representatives and the Senate passed a bill that would place all products from Xinjiang under suspicion of being produced by forced labor.

This reverses the burden of proof. Imports would then be banned as long as the US government is not presented with verifiable evidence that forced labor was not involved in the production. US President Biden still has to approve the bill. Republicans accuse Biden of filibustering, stating that the law would make it harder to expand renewable power. Biden’s plans to expand solar power are similarly ambitious to those of the new German government. By 2050, about half of US electricity is to be generated by solar power. Currently, it is only four percent.

But experts say the US law could prove to be ineffective for the solar supply chain. If the US bill is signed into law next year, Chinese manufacturers will already be prepared. “We expect that solar wafer manufacturers, all of which are located in China, will then be able to separate supply chains for different markets,” says Jenny Chase of Bloomberg NEF, confirming the suspicions of polysilicon expert Bernreuter. Another question will be whether buyer countries will simply believe the suppliers’ claims of origin.

Solar supply chains are currently still so complex that it is difficult to manufacture truly Xinjiang-free solar modules and cells. Industry expert Bernreuter, therefore, advises the industry to play it safe and become less dependent on China. “There is no way around building new solar supply chains outside of China.” This could increase the price of the modules by about ten percent. “If environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) criteria are more than just lip service to them, investors and consumers must be prepared to pay this price,” says Bernreuter.

The new German government also indicated that it intends to take action. The German Foreign Office states that the government wants to “support a possible import ban on products from forced labor at the European level”. Likewise, the European supply chain law is to be “supported.” However, a clear stand against forced labor in Xinjiang sounds different.

Modernizing EU legislation on batteries was one of the key issues at a meeting of EU environment ministers in Brussels on Monday. With digitalization as well as the implementation of climate protection measures, the demand for batteries will continue to increase in the coming years, which is why the EU wants to adapt the regulations on production, use, recycling as well as disposal to its Green Deal targets.

A comprehensive approach that takes into account the entire life cycle of batteries is particularly important, said Federal Minister of the Environment Steffi Lemke in Brussels on Monday, calling on the EU Commission to take a committed approach. The Green politician stressed that a stricter product policy was one of the priorities of the new federal government. This also includes the extension of producer responsibility at EU level.

So far, EU policy regulation of batteries has been limited to their disposal. This is now to change as a result of the new regulation within the framework of the Circular Economy Action Plan. Among other things, concrete targets are envisaged for the content of recycled material and for the collection of batteries at the end of their life.

For example, the current collection rate is to gradually increase from 45 percent to 65 percent in 2025 and 70 percent in 2030 so that valuable materials such as lithium, nickel, or cobalt are not lost to the economy. In addition, the EU Commission’s proposal provides for the repurposing of batteries from electric cars, which could continue to be used as stationary energy storage systems, for example.

In addition to lower primary raw material consumption, Lemke also demanded “that batteries in consumer products must be replaceable and that the entire product does not always end up in the trash.” The right to repair planned by the EU Commission is equally a question of environmental protection and the protection of criminals.

There are also to be stricter specifications for the manufacturing process, including the extraction and use of critical raw materials. In order to document compliance with the criteria over the entire life cycle, the EU is planning to introduce a digital product passport, which should ensure greater transparency. “Consumers want to know how batteries are produced, where the raw materials come from, and how high the recycling percentage is,” Lemke said. Particularly in electromobility, the credible presentation of environmental benefits is also important.

In addition, the EU wants to create a level playing field with the new regulation. According to the Commission, binding and comparable requirements are essential for the development of a more sustainable and competitive battery industry in Europe and worldwide. The Parliament’s Environment Committee will vote on the Commission’s proposals in January, followed by the plenary in February. til

It had already been clear for some time that Guntram Wolff would be leaving after nine years as Bruegel director. The respected Brussels think tank has now announced his successor: Jeromin Zettelmeyer. In Berlin, the economist is still known as the former head of the economic policy department in the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy under Sigmar Gabriel (SPD).

Born in Malaga in 1964, Zettelmeyer is currently still working for the International Monetary Fund. There he is Deputy Director of the Strategy and Policy Review Department. He also began his career at the Washington institution in 1994. In 2008, he moved to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), then to the BMWi in 2014. Before returning to the IMF, he worked as a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE).

Zettelmeyer is scheduled to take over from his predecessor Guntram Wolff in September 2022. The former Commission and Bundesbank employee will then reach the maximum term as Bruegel director of nine years. Wolff is one of the most influential economists at EU level, having advised the Council of Finance Ministers, among others. tho

In the dispute over the emergency framework for medical countermeasures, which forms the legal basis for the work of the new European crisis authority Hera, the EU states have agreed on a common line. According to the agreement, there are still plans to set up a crisis unit to coordinate measures for crisis-related medical countermeasures at EU level. However, the Commission will have to share the leadership of the crisis unit with the respective Council Presidency. Member states have also decided that the Commission must consult the crisis unit before taking any action.

Member states should also be able to mandate the Commission to act as a central purchasing body. As soon as the Commission intends to conclude a contract, it must inform the member states concerned. They will then be able to comment on the drafts before the contract is concluded.

The insufficient right to a say, in the view of some EU countries, was the central point of criticism by the member states of the EU Commission’s proposal for a regulation. The Commission’s plans did not envisage Hera as an independent authority but as a Directorate-General within the EU Commission. Therefore, the member states feared a far-reaching loss of control over measures in the event of a crisis and insisted on a stronger role for themselves in the governance structure. The political agreement now reached in the Permanent Representatives Committee (Coreper1) is to be officially adopted in EPSCO at the beginning of next year.

Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, and the Netherlands did not agree to the proposal and entered a scrutiny reservation but did not achieve the necessary blocking minority.

As expected, the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology formally pre-announced the second “Important Project of Common European Interest” (IPCEI) in the field of microelectronics to the European Commission yesterday on behalf of the participating member states.

A total of 20 of the 27 member states have expressed interest in participating in this second IPCEI. About 90 companies from the semiconductor industry, from the fields of special electronics, precursors and chip design, have registered projects. The essential core of the IPCEIs is cross-border cooperation, which is intended to enable research and applications that might otherwise not be feasible.

However, the format is also attractive for participating companies because of the subsidies that are possible within this framework: Only in November did the EU Commission amend the rules for the assessment of IPCEIs under state aid law with effect from January 1st.

European Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton was predictably enthusiastic about the high level of interest in IPCEI Microelectronics II: The project will enable investment for large-scale, innovative industrial capacity building at all bottlenecks in the supply chain, address supply constraints and support innovation for Europe’s leadership in microchips, Breton said in a post on LinkedIn.

In it, Breton also emphasized the role of his planned Chips Act. The proposed legislation is intended to simplify massive investments in Europe in the area of semiconductor production, facilitate research and development and thus reduce dependence on other regions in critical areas. Breton also hopes for high-end chip production within the EU.

However, the Chips Act is slipping backwards piece by piece in the EU Commission’s planning for 2022: In the meantime, the French commissioner’s prestigious project is on the Commission’s non-binding project plan for the last session before the summer break in 2022. fst

The European Commission has approved the €900 million H2Global funding program. The German project to support hydrogen imports from third countries is in line with the EU state aid guidelines, the Brussels-based authority announced on Monday.

H2Global is a funding instrument of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs, Energy and Climate Protection. The program is intended to help meet the demand for green hydrogen in the EU, which is set to increase significantly in the medium term, and is focusing in particular on untapped potential from renewable energy sources outside the EU. Because in order to fully decarbonize industry, the transport sector, and the energy industry without jeopardizing the security of supply, the EU‘s own capacities will not be sufficient – the EU will have to rely on imports.

In doing so, H2Global aims to promote a rapid market ramp-up of green hydrogen and hydrogen-based PtX products such as ammonia or methanol by guaranteeing investment security for the market participants involved. Thus, long-term purchase contracts are to be concluded on the supply side and short-term resale contracts on the demand side. The difference between supply and demand prices is to be compensated via subsidies – similar to the concept of “contracts for difference”.

Commission Vice-President Margrethe Vestager welcomed the support program. “This will support projects that lead to significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in line with the EU’s environmental and climate objectives and help meet the growing demand for renewable hydrogen in the Union,” said the Commissioner for Competition in Brussels. til

Ahead of the upcoming election of the President of the Parliament, the S&D group in the European Parliament is planning a hearing of EPP candidate Roberta Metsola in the second week of January. The Maltese is controversial mainly because of her strict opposition to abortion (Europe.Table reported). “We expect commitments and clarifications on some important issues such as women’s rights, tax justice, the rule of law, and social justice,” said S&D chair Iratxe García.

Only after the hearing do the Socialists want to decide on their voting behavior. García stresses that a vote for Metsola would also depend on her political priorities for the mandate. These would have to be compatible with the priorities of the S&D, with 147 MEPs the second largest group in the European Parliament.

At the beginning of December, the Renew Group in the European Parliament set out three conditions to which it would attach its vote for the next President of Parliament. The group has also already interviewed Metsola. However, consultations on whether to support the EPP candidate were still ongoing, according to a MEP’s office when asked by Europe.Table. “My choice has not been made yet. We’ll see which candidates are on the ballot in the end,” Valérie Hayer, co-chair of the French Renew delegation, told Médiapart newspaper.

However, insiders judge the probability that the political groups will send new candidates into the race at this point as extremely low. The election is already planned for the January plenary week (17.-21.01.21). Nobody wants to risk a postponement, according to parliamentary circles.

According to a press spokeswoman, it is still open whether the Greens/EFA group will also question Metsola within the framework of a hearing. It is clear that they will talk to the different candidates – but the timing and format are still open, as well as the voting behavior of the group. David Cormand, chairman of the French delegation of the Greens/EFA group, is belligerent: He demands that his group takes the initiative to stop the election of EPP candidate Metsola. “It is not too late for the Greens/EFA, S&D, Renew, and GUE/NGL groups to join forces to find a common progressive counter-candidate,” Cormand tells Europe.Table. koj

State aid in the internal market is subject to strict control by the Directorate-General (DG) for Competition. This is a prerequisite for effective competition. Exceptions are justified if the aid pursues objectives of overriding European interests. Even in such cases, state support must be appropriate, necessary, and proportionate. The payments should be decreasing and limited in time, and the beneficiaries should make their own contribution. The coverage of current operating costs requires a special justification. So much for the theory.

But does this stand up to the challenges of practice? In order to allow the approval of aid according to objective criteria, the Directorate-General for Competition draws up so-called state aid guidelines. If the member states move within such a framework, approval is a formality. There are hardly any authorizations outside this framework – apart from exemptions for certain sectors.

The state aid practice for industries in international competition becomes more tricky. Due to the focus on the internal market, market distortions in global trade do not play a role. If member states pay aid to compensate for distortions on the world market, for example for globally traded raw materials, the Directorate-General for Competition only looks at possible distortions in the internal market as a possible side effect.

In the case of the Green Deal, the practice of subsidies threatens to put a spanner in the works of successful implementation: For example, the expansion of renewable energies is subsidized. But what happens to companies that produce materials and components for the green transformation? The basic materials industry, for example, whose products are needed in growing quantities around the world, receives hardly any direct support, even though CO2 costs distort international competition considerably. Production costs are rising particularly sharply in this sector of the economy. This is because materials for climate protection, batteries, and digitalization require a lot of energy, especially electricity.

For such energy-intensive industries, there should continue to be exemptions in the new climate, environment and energy aid guidelines. This is not about subsidies but about relief from costs that competitors in third countries do not have. But the Directorate-General for Competition had taken the general state aid principles too much to heart in its original draft published in the summer of 2021.

Under the premise of an own high contribution, decreasing aid intensity, and growing quid pro quos, the perspective is missing to produce basic and materials, such as non-ferrous (NF) metals, in the EU. This is because expenditure on electricity accounts for up to 40 percent of total costs. If levies for renewable energies and indirect costs in the electricity price are only allowed to be compensated proportionately and less and less each year, the burdens on the non-ferrous metals industry will skyrocket.

In the meantime, the Directorate-General for Competition has improved its draft. The aid intensity is to be increased again and, above all, the burden at company level of those sectors that are at particular risk is to be limited. This is the right step. After all, the transformation to green industry requires enormous amounts of electricity that comes from renewable sources and is available at internationally competitive prices. It is important to allow non-ferrous metal foundries – like all other non-ferrous metal industries – access as well. We propose to include in the scope all government electricity cost components that are directly related to the energy transition. This is because the costs for infrastructure – grids, storage facilities, redispatch, power plant reserves, etc. – also lead to additional costs for industry.

On the world market, individual private-sector companies are increasingly competing with states. China is pursuing a strategic industrial policy. The spectrum of market distortions is broad and is taken up by European trade policy. Anti-dumping and anti-subsidy tariffs offer partial protection. When assessing subsidies, it must be clear that the deep pockets of the Chinese state are being deliberately opened to capture the world market and subsequently make the Western world dependent on supplies from China. A current example is magnesium as an indispensable alloying metal for all aluminum applications.

State aid is only the second-best way to keep and expand the production of basic materials and commodities in the EU. Nevertheless, EU state aid policy should pay more attention to the goals of the Green Deal, securing the supply of raw materials and international market distortions. Billions of euros of investment in climate neutrality and our continent’s resilience must not be held back by state aid law. It is time to reform state aid law and its control.

Olaf Scholz considers the topic “completely overrated”, and yet it could keep the German chancellor and his staff on their toes over the holidays: the EU climate taxonomy. The College of Commissioners will “most likely” discuss the draft delegated act at its meeting before the Christmas break, European Commissioner for Environment Virginijus Sinkevičius said on Monday evening.

The interested public is not likely to see the draft for the time being. However, the draft will be consulted with representatives of the member states and experts from the Platform on Sustainable Finance. It will then be adopted by the Commission and published. According to European Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton, this could be in mid-January. The Council and the European Parliament then have four weeks to object – although the hurdles for doing so are very high.

In any case, there is no longer any genuine suspense. Hardly anyone doubts that the Commission’s proposal will classify nuclear power plants as green and gas as a transitional technology. The only question that is being doggedly negotiated is: with what restrictions? Until which end date does the classification for gas-fired power plants apply? What performance limits must be met, and how will they be calculated?

Technical details, no doubt, but they have kept the President of the Commission, the Federal Chancellor, and the President of the Republic busy in recent weeks. And will probably continue to occupy them over Christmas and New Year’s Eve. Everyone else, however, can leave this “completely overrated” topic behind for the time being. Till Hoppe

Olaf Scholz made his inaugural visit to Rome yesterday. There, the German Chancellor not only praised Prime Minister Mario Draghi’s competence but also agreed on a joint “action plan” for better cooperation, initially without giving details.

Who gets to discuss which parts of European climate policy is decided not least by Charles Michel. The President of the European Council put the energy crisis on the agenda of the heads of state and government, as he did at the summit last Thursday. The technical elements of the Fit for 55 package, on the other hand, are reserved for the less politically charged and technically experienced Environment Council.

Climate measures were also on the agenda there yesterday. Lukas Scheid took a closer look at how the member states want to cushion the social impact of European climate policy. But the financing is still largely unresolved. And some member states simply want less climate policy – then there would be no need for social compensation.

Following the meeting, European Commissioner for Environment Virginijus Sinkevičius revealed what the College of Commissioners will “most likely” deal with before the Christmas break: the delegated act on climate taxonomy. The confidential draft will then be submitted to experts for evaluation before the authority decides and publishes it. Read what this means for the Christmas plans of Olaf Scholz and the rest of us in Apéro.

On Wednesday, the authority is also expected to present the new climate and energy aid guidelines, known in the jargon as CEEAG. In today’s guest article, Michael Niese of the Wirtschaftsvereinigung Metalle explains why the competition authorities should not throw out the baby with the bathwater.

In any case, Germany’s and Europe’s climate targets will hardly be achievable without a massive expansion of solar energy. But this brings with it human rights problems, as the example of Xinjiang shows: From the region, where Beijing’s rulers brutally suppress the minority of the Uyghurs, comes about half of a raw material important for the production of solar panels. Nico Beckert has analyzed the trade-off between clean supply chains and clean sources of electricity.

Batteries should also become cleaner: The new Federal Minister of the Environment, Steffi Lemke (Greens), has called for an ambitious approach at EU level. Timo Landenberger explains what this means and how the goals are to be achieved.

Health is on everyone’s lips again these days – and the EU is also taking on a bigger role in the pandemic than it has been given so far by the member states. The new EU health authority Hera has now defined their rights to have a say, according to Eugenie Ankowitsch’s report.

In Brussels, he is considered influential, and now a successor has been found for Guntram Wolff, who is leaving in 2022, as head of the think tank Bruegel. It’s likely, but not yet clear, whether the Maltese Roberta Metsola will be the next president of the European Parliament. While the Liberals have already asked her for an interview, the Social Democrats in the EP have now announced a hearing for January – and among the Greens, a revolutionary mood is spreading.

The Fit for 55 package presented by the EU Commission in July contains a proposal to minimize the negative impact of climate protection measures on the civilian population. The Social Climate Fund (SCF) aims to support vulnerable households and micro-enterprises whose livelihoods would be threatened by the measures taken.

The Commission wants to make €72.2 billion available for this purpose from 2025, financed by expanding the emissions trading system to include the buildings and transport sectors – also known as ETS 2. Thus, part of the profits from the sale of emission rights would go either as direct payments to private households or as investment aid for emission avoidance to companies. The idea behind investment subsidies: Those who avoid emissions save cash, as emissions become more expensive due to a CO2 price.

In principle, the EU states agree that the social impact of climate policy must be kept as low as possible and that a support fund can achieve this. However, the Commission’s funding plans so far are bitterly resented by some member states. Extending the ETS to buildings and transport is not seen as the most popular part of the Fit for 55 package. Poland would prefer to scrap ETS 2 altogether. The government in Warsaw fears additional burdens for particularly vulnerable groups. However, Poland would like to have the climate social fund after all and demands that it not be linked to the revenues from ETS 2.

Austria’s Minister of the Environment Leonore Gewessler, on the other hand, emphasized this link at the Environment Council. Vienna supports the extension of the ETS to buildings and transport on the condition that ambitious standards are introduced for both sectors that lead to structural emission reductions and that consumers are not the only ones burdened by the CO2 price. Austria was rather skeptical about the exact design of the SCF, as it would mean an intervention in the EU’s multiannual financial framework and would require the member states’ own funds. The Commission proposal provides for the member states to make available the same amount as the EU Commission – i.e., an additional €72.2 billion. Gewessler suggested thinking about an “alternative financial construction” of the SCF.

The latter would also meet with approval in Budapest. The Hungarian government doesn’t want a social climate fund at all but would rather see the EU’s modernization fund strengthened with additional financial resources. But if the SCF does see the light of day, the member states’ flat-rate contribution of 50 percent should not be applied. Instead, Hungary said yesterday in Brussels, an individual national contribution should be made based on the level of development of the respective country. Budapest also wants to prevent a CO2 price for buildings and transport if possible.

The Czech Republic even fears for the acceptance of European climate policy among the population if prices in the transport and building sector rise due to ETS expansion. The SCF could be a solution, but the Commission’s proposal sounds very administration-intensive. Moreover, it is not known whether the SCF would actually be able to cushion the social challenges posed by rising CO2 prices, the Christian Democrat Czech Minister of the Environment Anna Hubáčková, who only took office last Friday, said on Monday.

Germany is considered the most vocal supporter of the Commission’s plans for ETS expansion. At the Environment Council, State Secretary Patrick Graichen from the new Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Change represented the German position in the debate on the Fit for 55 package (Federal Minister of the Environment Steffi Lemke spoke for the issues concerning nature and consumer protection).

Graichen stressed that the new federal government would bring new momentum to climate policy and explained that Germany is in favor of a CO2 minimum price of €60 per tonne, which would also apply to ETS 2. “The prices have to point in the right direction so that you can actually achieve the emission reductions that are needed,” said the State Secretary, explaining the demand. Graichen pleaded overall for an ambitious package with social compensation. How the social compensation could look like still has to be discussed.

The Commissioner responsible for the Fit for 55 projects and Executive Vice-President Frans Timmermans even showed himself open to alternatives to ETS expansion at the end of the exchange of views. However, he also made clear that these alternatives would have to put Europe just as much on track to meet the climate targets for 2030 and 2050. Timmermans defended the expansion of the ETS by saying that emissions are still rising only in the transport sector and falling too slowly in the buildings sector. The ETS has shown that it works and should therefore be extended. However, it is equally up to the Commission and the member states to ensure that no one is left behind as a result of the European climate plans, Timmermans said.

There were no negotiations at the Environment Council, so from January, it will be up to the French Presidency to unite the member states in their differing views on how the social balance to the climate protection plans will be shaped.

The new federal government has a number of plans for the expansion of renewable powers. It wants to mount solar power on “all suitable roofs”. By 2030, “around 200 gigawatts” of photovoltaic capacity are to be achieved. This means a quadrupling of the current capacity. To achieve this, the traffic light coalition wants to remove many “hurdles to expansion”. This is what the coalition agreement says.

The supply chain of the solar industry is one major hurdle that is not mentioned. A large part of the basic material of solar cells, polysilicon, is produced in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. However, there are accusations that this polysilicon is produced through forced labor by the Uyghur ethnic group. This poses considerable problems if ethical standards are to apply to this supply chain in the future.

Recently, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock announced a clearer policy against human rights violations in China. “If products from regions like Xinjiang, where forced labor is common practice, are blocked, that’s a big problem for an exporting country like China,” she said in an interview with taz and China.Table.

But it is not only China, who would then face a problem. The expansion of solar energy in Germany could also come to a grinding halt. Much of the polysilicon is processed directly in China. The People’s Republic is the global market leader in the solar sector and dominates all production steps. Worldwide, three out of four solar modules and 83 percent of solar cells are produced in China. China dominates 77 percent of the global market for polysilicon. Xinjiang again plays a special role here. An estimated 50 percent of global polysilicon production is located in the western Chinese region.

Large amounts of power are required for the production of polysilicon and its precursor silicon metal. Xinjiang has an abundance of it. There is hardly any other part of the country where power and process heat for the production of polysilicon is so cheap. Four of the world’s largest manufacturers have factories in Xinjiang, according to an analysis by Bloomberg. Three producers have been accused of using forced labor in their factories.

The allegations are based on reports by consulting firms Horizon Advisory and S&P Global Market Intelligence, as well as research by Xinjiang researcher Adrian Zenz. They independently conclude that hundreds of forced laborers are involved in the production of polysilicon. A Bloomberg research team was denied access to the factories. The journalists have not been allowed to examine the production and interpret this as a sign that the manufacturers have something to hide.

Other experts, however, give the all-clear in part. True, China’s global market share looks very high on paper. But a large part of it remains domestic. No other country installs as many solar modules as China. A large part of the domestic production is therefore not exported in the first place.

Moreover, the other half of China’s production is produced outside Xinjiang. Together with manufacturing in other regions of the world, there are enough solar modules to meet demand. “The US and Europe together accounted for about 30 percent of new global PV installations in 2020,” says market observer Johannes Bernreuter of consulting firm Bernreuter Research. “So arithmetically, there is enough polysilicon for the US and Europe right now that is not affected by Xinjiang.”

Surprisingly, neither the EU’s statistical authority (Eurostat) nor the Federal Statistical Office have any data on how many solar cells and modules Germany imports from China.

But when Western buyers acquire solar cells and modules from China, they have so far been faced with a problem: Polysilicon from various sources is mixed during production. It could very well be that basic material from Xinjiang is also included, which was produced through forced labor. However, Chinese manufacturers are adapting to the needs of the West. Some companies are likely producing Xinjiang-free segments and using them in their solar modules for export to the US and Europe, Bernreuter explains. “They can also provide plausible documents that the solar modules and cells do not contain any primary products from Xinjiang.”

This could mean that material flows could simply be split: Xinjiang-free products are manufactured for export. Solar modules, whose raw material is produced through forced labor, continue to be installed in China due to the high domestic demand. Western sanctions and boycotts of polysilicon from Xinjiang would thus have little effect. Bernreuter criticizes: “To put it bluntly: The West eases its conscience, but the Uyghurs are not better off.” However, one should not underestimate sanctions as a political signal, Bernreuter adds.

Another problem in the solar supply chain is the basic material for polysilicon: so-called metallurgical-grade silicon. The Chinese manufacturers of this highly pure silicon have no interest in transparency. So importers can hardly be sure that no forced labor is involved in the production of metallurgical-grade silicon. This is the reason why some Western and Asian manufacturers of polysilicon have already terminated their business relations with the largest producer of metallurgical silicon, Hoshine Silicon from Xinjiang. In addition, the US Customs Service has taken action against Hoshine. There is information that the company uses forced labor, the agency said. Products from Hoshine are confiscated by customs at US ports.

However, this by no means resolves the situation. The US is currently discussing additional measures to exclude forced labor in Xinjiang in imported products. As these go far beyond current measures, it would further reduce the number of basic materials that can be imported legally. Recently, the US House of Representatives and the Senate passed a bill that would place all products from Xinjiang under suspicion of being produced by forced labor.

This reverses the burden of proof. Imports would then be banned as long as the US government is not presented with verifiable evidence that forced labor was not involved in the production. US President Biden still has to approve the bill. Republicans accuse Biden of filibustering, stating that the law would make it harder to expand renewable power. Biden’s plans to expand solar power are similarly ambitious to those of the new German government. By 2050, about half of US electricity is to be generated by solar power. Currently, it is only four percent.

But experts say the US law could prove to be ineffective for the solar supply chain. If the US bill is signed into law next year, Chinese manufacturers will already be prepared. “We expect that solar wafer manufacturers, all of which are located in China, will then be able to separate supply chains for different markets,” says Jenny Chase of Bloomberg NEF, confirming the suspicions of polysilicon expert Bernreuter. Another question will be whether buyer countries will simply believe the suppliers’ claims of origin.

Solar supply chains are currently still so complex that it is difficult to manufacture truly Xinjiang-free solar modules and cells. Industry expert Bernreuter, therefore, advises the industry to play it safe and become less dependent on China. “There is no way around building new solar supply chains outside of China.” This could increase the price of the modules by about ten percent. “If environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) criteria are more than just lip service to them, investors and consumers must be prepared to pay this price,” says Bernreuter.

The new German government also indicated that it intends to take action. The German Foreign Office states that the government wants to “support a possible import ban on products from forced labor at the European level”. Likewise, the European supply chain law is to be “supported.” However, a clear stand against forced labor in Xinjiang sounds different.

Modernizing EU legislation on batteries was one of the key issues at a meeting of EU environment ministers in Brussels on Monday. With digitalization as well as the implementation of climate protection measures, the demand for batteries will continue to increase in the coming years, which is why the EU wants to adapt the regulations on production, use, recycling as well as disposal to its Green Deal targets.

A comprehensive approach that takes into account the entire life cycle of batteries is particularly important, said Federal Minister of the Environment Steffi Lemke in Brussels on Monday, calling on the EU Commission to take a committed approach. The Green politician stressed that a stricter product policy was one of the priorities of the new federal government. This also includes the extension of producer responsibility at EU level.

So far, EU policy regulation of batteries has been limited to their disposal. This is now to change as a result of the new regulation within the framework of the Circular Economy Action Plan. Among other things, concrete targets are envisaged for the content of recycled material and for the collection of batteries at the end of their life.

For example, the current collection rate is to gradually increase from 45 percent to 65 percent in 2025 and 70 percent in 2030 so that valuable materials such as lithium, nickel, or cobalt are not lost to the economy. In addition, the EU Commission’s proposal provides for the repurposing of batteries from electric cars, which could continue to be used as stationary energy storage systems, for example.

In addition to lower primary raw material consumption, Lemke also demanded “that batteries in consumer products must be replaceable and that the entire product does not always end up in the trash.” The right to repair planned by the EU Commission is equally a question of environmental protection and the protection of criminals.

There are also to be stricter specifications for the manufacturing process, including the extraction and use of critical raw materials. In order to document compliance with the criteria over the entire life cycle, the EU is planning to introduce a digital product passport, which should ensure greater transparency. “Consumers want to know how batteries are produced, where the raw materials come from, and how high the recycling percentage is,” Lemke said. Particularly in electromobility, the credible presentation of environmental benefits is also important.

In addition, the EU wants to create a level playing field with the new regulation. According to the Commission, binding and comparable requirements are essential for the development of a more sustainable and competitive battery industry in Europe and worldwide. The Parliament’s Environment Committee will vote on the Commission’s proposals in January, followed by the plenary in February. til

It had already been clear for some time that Guntram Wolff would be leaving after nine years as Bruegel director. The respected Brussels think tank has now announced his successor: Jeromin Zettelmeyer. In Berlin, the economist is still known as the former head of the economic policy department in the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy under Sigmar Gabriel (SPD).

Born in Malaga in 1964, Zettelmeyer is currently still working for the International Monetary Fund. There he is Deputy Director of the Strategy and Policy Review Department. He also began his career at the Washington institution in 1994. In 2008, he moved to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), then to the BMWi in 2014. Before returning to the IMF, he worked as a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE).

Zettelmeyer is scheduled to take over from his predecessor Guntram Wolff in September 2022. The former Commission and Bundesbank employee will then reach the maximum term as Bruegel director of nine years. Wolff is one of the most influential economists at EU level, having advised the Council of Finance Ministers, among others. tho

In the dispute over the emergency framework for medical countermeasures, which forms the legal basis for the work of the new European crisis authority Hera, the EU states have agreed on a common line. According to the agreement, there are still plans to set up a crisis unit to coordinate measures for crisis-related medical countermeasures at EU level. However, the Commission will have to share the leadership of the crisis unit with the respective Council Presidency. Member states have also decided that the Commission must consult the crisis unit before taking any action.

Member states should also be able to mandate the Commission to act as a central purchasing body. As soon as the Commission intends to conclude a contract, it must inform the member states concerned. They will then be able to comment on the drafts before the contract is concluded.

The insufficient right to a say, in the view of some EU countries, was the central point of criticism by the member states of the EU Commission’s proposal for a regulation. The Commission’s plans did not envisage Hera as an independent authority but as a Directorate-General within the EU Commission. Therefore, the member states feared a far-reaching loss of control over measures in the event of a crisis and insisted on a stronger role for themselves in the governance structure. The political agreement now reached in the Permanent Representatives Committee (Coreper1) is to be officially adopted in EPSCO at the beginning of next year.

Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, and the Netherlands did not agree to the proposal and entered a scrutiny reservation but did not achieve the necessary blocking minority.

As expected, the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology formally pre-announced the second “Important Project of Common European Interest” (IPCEI) in the field of microelectronics to the European Commission yesterday on behalf of the participating member states.

A total of 20 of the 27 member states have expressed interest in participating in this second IPCEI. About 90 companies from the semiconductor industry, from the fields of special electronics, precursors and chip design, have registered projects. The essential core of the IPCEIs is cross-border cooperation, which is intended to enable research and applications that might otherwise not be feasible.

However, the format is also attractive for participating companies because of the subsidies that are possible within this framework: Only in November did the EU Commission amend the rules for the assessment of IPCEIs under state aid law with effect from January 1st.

European Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton was predictably enthusiastic about the high level of interest in IPCEI Microelectronics II: The project will enable investment for large-scale, innovative industrial capacity building at all bottlenecks in the supply chain, address supply constraints and support innovation for Europe’s leadership in microchips, Breton said in a post on LinkedIn.

In it, Breton also emphasized the role of his planned Chips Act. The proposed legislation is intended to simplify massive investments in Europe in the area of semiconductor production, facilitate research and development and thus reduce dependence on other regions in critical areas. Breton also hopes for high-end chip production within the EU.

However, the Chips Act is slipping backwards piece by piece in the EU Commission’s planning for 2022: In the meantime, the French commissioner’s prestigious project is on the Commission’s non-binding project plan for the last session before the summer break in 2022. fst

The European Commission has approved the €900 million H2Global funding program. The German project to support hydrogen imports from third countries is in line with the EU state aid guidelines, the Brussels-based authority announced on Monday.

H2Global is a funding instrument of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs, Energy and Climate Protection. The program is intended to help meet the demand for green hydrogen in the EU, which is set to increase significantly in the medium term, and is focusing in particular on untapped potential from renewable energy sources outside the EU. Because in order to fully decarbonize industry, the transport sector, and the energy industry without jeopardizing the security of supply, the EU‘s own capacities will not be sufficient – the EU will have to rely on imports.

In doing so, H2Global aims to promote a rapid market ramp-up of green hydrogen and hydrogen-based PtX products such as ammonia or methanol by guaranteeing investment security for the market participants involved. Thus, long-term purchase contracts are to be concluded on the supply side and short-term resale contracts on the demand side. The difference between supply and demand prices is to be compensated via subsidies – similar to the concept of “contracts for difference”.

Commission Vice-President Margrethe Vestager welcomed the support program. “This will support projects that lead to significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in line with the EU’s environmental and climate objectives and help meet the growing demand for renewable hydrogen in the Union,” said the Commissioner for Competition in Brussels. til

Ahead of the upcoming election of the President of the Parliament, the S&D group in the European Parliament is planning a hearing of EPP candidate Roberta Metsola in the second week of January. The Maltese is controversial mainly because of her strict opposition to abortion (Europe.Table reported). “We expect commitments and clarifications on some important issues such as women’s rights, tax justice, the rule of law, and social justice,” said S&D chair Iratxe García.

Only after the hearing do the Socialists want to decide on their voting behavior. García stresses that a vote for Metsola would also depend on her political priorities for the mandate. These would have to be compatible with the priorities of the S&D, with 147 MEPs the second largest group in the European Parliament.

At the beginning of December, the Renew Group in the European Parliament set out three conditions to which it would attach its vote for the next President of Parliament. The group has also already interviewed Metsola. However, consultations on whether to support the EPP candidate were still ongoing, according to a MEP’s office when asked by Europe.Table. “My choice has not been made yet. We’ll see which candidates are on the ballot in the end,” Valérie Hayer, co-chair of the French Renew delegation, told Médiapart newspaper.

However, insiders judge the probability that the political groups will send new candidates into the race at this point as extremely low. The election is already planned for the January plenary week (17.-21.01.21). Nobody wants to risk a postponement, according to parliamentary circles.

According to a press spokeswoman, it is still open whether the Greens/EFA group will also question Metsola within the framework of a hearing. It is clear that they will talk to the different candidates – but the timing and format are still open, as well as the voting behavior of the group. David Cormand, chairman of the French delegation of the Greens/EFA group, is belligerent: He demands that his group takes the initiative to stop the election of EPP candidate Metsola. “It is not too late for the Greens/EFA, S&D, Renew, and GUE/NGL groups to join forces to find a common progressive counter-candidate,” Cormand tells Europe.Table. koj

State aid in the internal market is subject to strict control by the Directorate-General (DG) for Competition. This is a prerequisite for effective competition. Exceptions are justified if the aid pursues objectives of overriding European interests. Even in such cases, state support must be appropriate, necessary, and proportionate. The payments should be decreasing and limited in time, and the beneficiaries should make their own contribution. The coverage of current operating costs requires a special justification. So much for the theory.

But does this stand up to the challenges of practice? In order to allow the approval of aid according to objective criteria, the Directorate-General for Competition draws up so-called state aid guidelines. If the member states move within such a framework, approval is a formality. There are hardly any authorizations outside this framework – apart from exemptions for certain sectors.

The state aid practice for industries in international competition becomes more tricky. Due to the focus on the internal market, market distortions in global trade do not play a role. If member states pay aid to compensate for distortions on the world market, for example for globally traded raw materials, the Directorate-General for Competition only looks at possible distortions in the internal market as a possible side effect.

In the case of the Green Deal, the practice of subsidies threatens to put a spanner in the works of successful implementation: For example, the expansion of renewable energies is subsidized. But what happens to companies that produce materials and components for the green transformation? The basic materials industry, for example, whose products are needed in growing quantities around the world, receives hardly any direct support, even though CO2 costs distort international competition considerably. Production costs are rising particularly sharply in this sector of the economy. This is because materials for climate protection, batteries, and digitalization require a lot of energy, especially electricity.

For such energy-intensive industries, there should continue to be exemptions in the new climate, environment and energy aid guidelines. This is not about subsidies but about relief from costs that competitors in third countries do not have. But the Directorate-General for Competition had taken the general state aid principles too much to heart in its original draft published in the summer of 2021.

Under the premise of an own high contribution, decreasing aid intensity, and growing quid pro quos, the perspective is missing to produce basic and materials, such as non-ferrous (NF) metals, in the EU. This is because expenditure on electricity accounts for up to 40 percent of total costs. If levies for renewable energies and indirect costs in the electricity price are only allowed to be compensated proportionately and less and less each year, the burdens on the non-ferrous metals industry will skyrocket.

In the meantime, the Directorate-General for Competition has improved its draft. The aid intensity is to be increased again and, above all, the burden at company level of those sectors that are at particular risk is to be limited. This is the right step. After all, the transformation to green industry requires enormous amounts of electricity that comes from renewable sources and is available at internationally competitive prices. It is important to allow non-ferrous metal foundries – like all other non-ferrous metal industries – access as well. We propose to include in the scope all government electricity cost components that are directly related to the energy transition. This is because the costs for infrastructure – grids, storage facilities, redispatch, power plant reserves, etc. – also lead to additional costs for industry.

On the world market, individual private-sector companies are increasingly competing with states. China is pursuing a strategic industrial policy. The spectrum of market distortions is broad and is taken up by European trade policy. Anti-dumping and anti-subsidy tariffs offer partial protection. When assessing subsidies, it must be clear that the deep pockets of the Chinese state are being deliberately opened to capture the world market and subsequently make the Western world dependent on supplies from China. A current example is magnesium as an indispensable alloying metal for all aluminum applications.

State aid is only the second-best way to keep and expand the production of basic materials and commodities in the EU. Nevertheless, EU state aid policy should pay more attention to the goals of the Green Deal, securing the supply of raw materials and international market distortions. Billions of euros of investment in climate neutrality and our continent’s resilience must not be held back by state aid law. It is time to reform state aid law and its control.

Olaf Scholz considers the topic “completely overrated”, and yet it could keep the German chancellor and his staff on their toes over the holidays: the EU climate taxonomy. The College of Commissioners will “most likely” discuss the draft delegated act at its meeting before the Christmas break, European Commissioner for Environment Virginijus Sinkevičius said on Monday evening.

The interested public is not likely to see the draft for the time being. However, the draft will be consulted with representatives of the member states and experts from the Platform on Sustainable Finance. It will then be adopted by the Commission and published. According to European Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton, this could be in mid-January. The Council and the European Parliament then have four weeks to object – although the hurdles for doing so are very high.

In any case, there is no longer any genuine suspense. Hardly anyone doubts that the Commission’s proposal will classify nuclear power plants as green and gas as a transitional technology. The only question that is being doggedly negotiated is: with what restrictions? Until which end date does the classification for gas-fired power plants apply? What performance limits must be met, and how will they be calculated?

Technical details, no doubt, but they have kept the President of the Commission, the Federal Chancellor, and the President of the Republic busy in recent weeks. And will probably continue to occupy them over Christmas and New Year’s Eve. Everyone else, however, can leave this “completely overrated” topic behind for the time being. Till Hoppe