A kingdom for a government: After the elections in Spain created unclear majority conditions, King Felipe VI last night proposed the head of the conservative People’s Party, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, to form a government.

With this, the head of state first tasked the numerical winner of the July 23 elections with forming a government. Feijóo’s Partido Popular (PP) won 16 more seats than the Socialists (PSOE) of incumbent Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez.

Nevertheless, it is questionable whether Feijóo can succeed. Currently, in addition to his party’s seats (137), the PP leader also has those of the right-wing populist party Vox (33) and two seats from smaller parties, for a total of 172 deputies. “My chances of forming a government are only four deputies away from an absolute majority,” Feijóo explained.

For his part, Pedro Sánchez predicted that the debate over Feijóo’s inauguration would be a failure. “If Feijóo wants to hit the wall of reality, that is his right and his decision,” he said. However, so far Sánchez also does not have the support needed to form a government.

Now the debate and vote in the House of Representatives is pending. The date is to be announced shortly. Who will govern Spain in the future still seems open despite the King’s decision.

Frans Timmermans is leaving the EU Commission with immediate effect to become the leading candidate of the Social Democrats and the Greens in the upcoming elections in the Netherlands. Responsibility for the Green Deal will be taken over by Slovakian Commission Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced on Tuesday. His focus will be less on new legislative proposals than on the implementation of the agreed plans and the dialogue with industry, farmers and forest owners.

The CDU politician is thus using the departure of climate czar Timmermans to send a signal to her critics in the EPP and the business community. These had called for a regulatory pause in view of the many laws on climate protection and biodiversity. It was time to focus on implementing the rules that had been adopted, von der Leyen said. “Our priority is strengthening clean innovation in industry, modernizing our grids and infrastructure for the energy transition, and access to critical raw materials.”

It is still unclear what the new work order means for the few legislative initiatives that the authority still wanted to present in the legislative period ending in 2024. In the pipeline are, in particular, a law on sustainable food systems and the reform of the chemicals legislation REACH, which is unpopular in the industry.

Šefčovič will initially coordinate the Green Deal in the Commission as Executive Vice-President, as Timmermans has done up to now, and at the same time be responsible for individual laws as Climate Commissioner. However, he will relinquish this second task when the Dutch government nominates a suitable candidate to succeed Timmermans. It is still open who The Hague will propose. The European Parliament also still has a say.

Šefčovič brings with him a wealth of experience; the 57-year-old diplomat is already serving his third term at the Brussels-based authority. He will continue to be responsible for relations with the United Kingdom and Switzerland, as well as with the European Parliament and the Council. His good contacts in the other EU institutions could help to moderate the trilogues on difficult dossiers such as renaturation legislation and pesticide regulation, according to the Commission. The former energy Commissioner also brings with him previous technical knowledge.

Timmermans will leave without having fully completed the Green Deal, his major project as Vice-President of the Commission. The 62-year-old is leaving the agency altogether to join Dutch politics, he announced this evening. Earlier, the party alliance of PvdA and GroenLinks said nearly 92 percent of its members had voted in favor of the Social Democrat as its top candidate for the Nov. 22 general election.

Von der Leyen thanked Timmermans for his commitment to the goal of making Europe the first climate-neutral continent. The articulate politician had lobbied hard for the comprehensive package of laws on climate protection, biodiversity and pollution control, and also represented the EU in international climate negotiations. Timmermans knew the ropes in Brussels since his first term in the Commission under Jean-Claude Juncker from 2014 to 2019.

Timmermans threw himself into the arguments with verve – and thus increasingly became a red rag for his critics, especially in the European People’s Party. The conflict manifested itself in the Nature Restoration Law, which the EPP tried to prevent – ultimately without success. The text was eventually narrowly passed by Parliament, but in a significantly weakened version.

Another controversial proposal, the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation (SUR), is still being negotiated. With the Pesticides Regulation, the Commission wants to halve the use of pesticides by 2030 and completely ban pesticides of particular ecological concern.

Also pending is the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED), through which the Commission aims to curb pollutant emissions from industrial facilities, including large livestock operations.

It was also previously planned that the EU executive would present its proposal for a Sustainable Food Systems Act in the third quarter of 2023. Originally billed as overarching legislation for the Farm to Fork strategy – the agriculture and food component of the Green Deal – environmentalists fear the proposal could end up focusing more on food safety. Till Hoppe and Claire Stam

Margrethe Vestager from Denmark is currently Vice-President of the EU Commission and responsible for competition, while Nadia Calviño from Spain is Finance Minister in Madrid. The other candidates are EIB Vice-President Teresa Czerwinska from Poland, EIB Vice-President Thomas Östros from Sweden and former Italian Minister of Economy Daniele Franco. All candidates must go through a selection process run by the Bank to determine whether they are suitable for the roles on the EIB’s Management Committee.

The assessment is carried out by an Advisory Committee on Appointments, which consists of five members who are independent of the EIB. According to information available to Table.Media, the screening process has now been completed for four candidates, with only the assessment of the Spaniard Calviño still pending. However, this is expected to be completed soon – a special meeting of the external panel in the first week of September is being negotiated. If the candidates are confirmed by their governments after submission of the overall assessment, the candidacies will be official.

For Vestager, according to the internal rules of the EU Commission, this would mean that she would have to rest her office from that point on. The first debate at the level of the EU finance ministers, who are also the bank’s governors, is scheduled for the informal meeting of ministers on Sept. 16 in Santiago de Compostela, Spain. However, according to the information, a decision is not yet expected for this debate.

However, an agreement on the Hoyer successor at the informal Ecofin meeting would be very ambitious, they said. More likely would be an agreement at the regular Ecofin a month later. This would be sufficient time for the bank to fill the top job in time for Jan. 1, 2024, due to the subsequent internal processes. The decision-making process has been moderated by Belgian Finance Minister Vincent van Peteghem, who is currently Chairman of the EIB’s Board of Directors.

Van Peteghem is reportedly pushing for a consensual solution. However, if no consensus is reached among the member states, the successor to Hoyer, who headed the EU’s main bank for twelve years, would have to be decided by a qualified majority. The new president would then have to unite 18 member states and 68 percent of the subscribed capital. However, there are certainly possibilities of reaching a consensual solution.

One option, for example, would be to leave Vestager in charge of the bank and install Calviño as “Executive Vice-President” along the lines of the Commission. Installing Calviño as a strong Vice-President with an important portfolio would be possible, as it is Spain’s turn to provide the member of the EIB’s Board of Directors from January. There are also other management personnel changes at the turn of the year. Bulgarian Lilyana Pavlova and Belgian Kris Peeters are leaving the governing body, while Nicola Beer is joining as a new German Vice-President.

The personnel changes offer a good starting position for a comprehensive reassignment of responsibilities. Who ultimately wins the race at the top is likely to shape the strategic direction of the bank over the coming years. In this context, the Dane Vestager is seen as having a technology-savvy approach, which goes hand in hand with higher risks and smaller financing volumes. Calviño, on the other hand, is associated with rather lower-risk, large-volume projects of the kind the bank used to finance with its extensive infrastructure projects.

The reason given is that it is currently worthwhile for a number of southern EU countries to finance projects via the bank instead of paying for them out of their own budgets, as the national refinancing costs are higher than those of the EIB. However, the future direction of EIB policy outside the EU remains open for both candidates. The outgoing president, Hoyer, has given high priority to the bank’s external presence and has set up a separate strategic unit within the bank, EIB Global, for this purpose. This unit is to play a leading role in project financing for EU foreign policy over time.

The 15th summit of the BRICS countries began on Tuesday at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg. It could herald a new era in which world politics can no longer ignore the BRICS movement. In addition to government representatives of the five member states Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, numerous other countries will be represented. The BRICS countries are expected to grow mightily: The inclusion of Argentina, Egypt, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia is considered assured, according to Reuters. More than 40 countries have shown interest in membership, including Iran, Ethiopia, Cuba, DR Congo and Kazakhstan. Twenty-two states have already submitted a formal application.

With what goal was BRICS founded?

Originally, Jim O’Neill, then an economist at the US investment bank Goldman Sachs, developed this concept more than 20 years ago. The BRICS countries had nothing in common politically, economically, culturally or historically. Yet it was supposed to unite rapid economic growth. That was indeed the case. Today, according to South African government figures, the five states account for 42 percent of the world’s population and 23 percent of the world’s economic output. This brings the BRICS countries closer to the developed countries in economic terms. The G7 group of the old industrialized nations – the USA, Germany, France, Italy, Great Britain, Canada and Japan – accounts for 44 percent of global economic output and ten percent of the world’s population.

What has brought about the discussion of BRICS enlargement?

The BRICS countries Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa seek an end to the existing world order and the dominance of the West, with the aim of becoming a counterweight in world politics. Based on their experience, they consider political relations with the powerful US to be unpredictable, especially due to the foreign policy doctrine according to which “democratic ideals” and a neoliberal economic policy are enforced by force if necessary.

What are China’s interests?

The war in Ukraine has greatly increased interest in BRICS, and Russia in particular is determined to use the group of states for its own benefit. Moscow sees a strengthened organization as a way to circumvent Western sanctions. It’s a similar story with China. With BRICS, Beijing is trying to build new structures in international politics. At the heart of its power ambitions is the “Global Security Strategy” unveiled last year. According to this concept, Beijing defines itself as a peace power that guarantees stability and development, in contrast to the US and its allies, who provoke wars and crises.

China derives conclusions from transatlantic unity for a possible conflict with Taiwan: While Beijing believes it cannot rely on Western, democratic states, it sees an opportunity in the Global South to avert isolation in the event of a conflict.

And what are Russia’s interests?

Russia wants to continue working on nothing less than a “democratization of international life,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov wrote in a guest article for the South African magazine Ubuntu at the start of the summit. Russia, he said, is working for “an architecture of international relations based on indivisible security as well as civilizational diversity and enabling equal developments for all members of the world community, without distinction”. Lavrov speaks of “tectonic shifts” in the world, of the loss of importance of the dollar, accuses the West collectively of racism, and sees a “fairer, multipolar world order emerging – thanks to BRICS and the expected expansion of the organization”.

The summit itself is at the same time a minor ignominy for Russia, because Russian President Vladimir Putin will only be present via video. Otherwise, South Africa would have had to arrest him during a visit and extradite him to the International Criminal Court. Putin did not take this risk. Lavrov wrote as little about this as he did about Ukraine, which Russia invaded. But Lavrov’s tenor was picked up by important Russian media, quoted experts in Russian newspapers praising the development of the multipolar world.

What is Africa’s position in this attempt at reordering?

For many African countries, the global confrontation between China, Russia and the USA offers an opportunity. They are being courted like never before, by the USA and Europe as well as by China and Russia. South Africa wants to take advantage of this momentum at the summit in Johannesburg. The country is primarily concerned with growth, sustainable development and inclusive multilateralism.

What makes BRICS attractive to new members?

The emerging countries in particular expect the BRICS to provide a counterweight to the multilateral institutions that emerged after the Second World War: above all the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. In these, the old powers of yesteryear have secured the greatest influence, so that the fast-growing countries in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa feel that they are not given enough consideration in these institutions.

In recent years, new institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank have emerged or existing ones such as the African Development Bank have been strengthened in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. But BRICS has emerged as the most powerful idea yet to challenge the existing world order.

Why are the BRICS countries striving for their own currency?

Dollar supremacy grants the US great privileges in the global economy. It can exclude countries such as Iran or Russia from access to US dollars. Also, central banks and governments almost inevitably have to invest at least part of their foreign exchange reserves in dollars. To do so, they usually buy US government bonds, the most liquid asset class in the world, and thus help finance the US government budget. Many BRICS countries refuse to do this.

However, the establishment of a new world reserve currency is likely to be the most ambitious project of the emerging countries. The new currency would have to be as liquid and as universally accepted as the dollar. Also, the issuer of a new world reserve currency would have to be a net debtor in the international financial markets to ensure that enough foreign exchange enters the world. Having a world currency also brings disadvantages. Under certain conditions, for example, there is the threat of uncontrolled inflation.

It is conceivable, however, that the BRICS will succeed in pushing back the dollar at certain points, for example in the trade of commodities such as oil or gold. Which currency – an existing one like the Chinese yuan or a new artificial currency – will benefit from this is an open question.

What is the role of the New Development Bank?

The New Development Bank (NDB) serves as a multilateral development bank for the BRICS countries, providing an alternative to the World Bank and IMF institutions. The idea for the bank stems from a proposal in 2012, when the BRICS countries first considered joint management of reserves. In 2014, the BRICS established the NDB and its sister institution, the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CAR). The current head of the NDB is the former president of Brazil, Dilma Roussef.

The NDB primarily finances development projects and infrastructure within the five BRICS countries and is thus intended as an alternative to Western-style development banks such as the World Bank. The CAR, on the other hand, is primarily intended as protection against international liquidity bottlenecks and is designed to protect the national currencies of the BRICS countries against global financial pressure. The $100 billion CAR is tasked with providing support in the event of actual or potential short-term balance of payments strains, making it primarily an alternative to the IMF.

Will this bank change international development assistance?

The New Development Bank could strengthen the role of the BRICS group in development policy and thus set new accents in international development aid. The BRICS countries see themselves in the tradition of the Bandung Conference, which took place in Indonesia in 1955 and from which the Non-Aligned Movement emerged. At that time, the participating countries were united by an anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist stance. This includes the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of a state. Thus, the BRICS countries today also reject a development policy of the kind pursued by the West, in which it uses financial support as leverage to impose political goals and values in the recipient countries. Christian von Hiller, Arne Schütte, Viktor Funk, Harald Prokosch

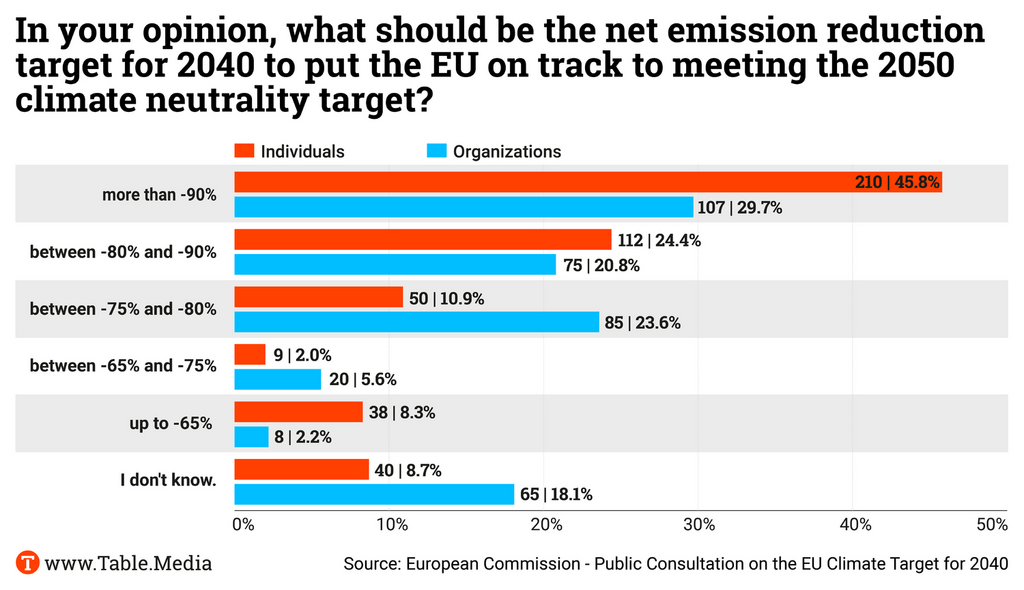

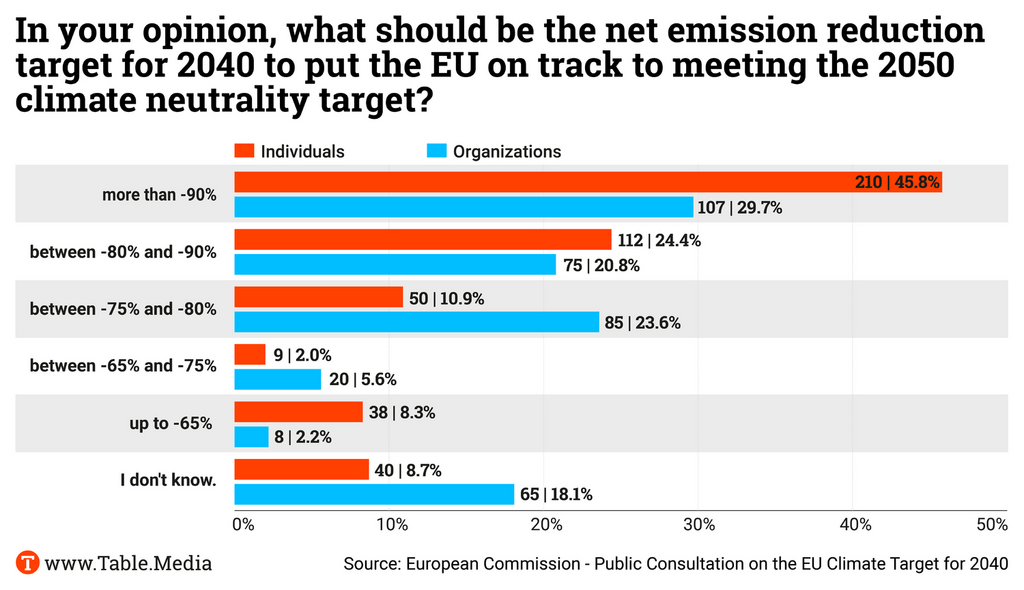

In the EU Commission’s consultation on the Union’s climate target for 2040, a majority of participants spoke out in favor of more speed in climate protection. The highest level of support for greater CO2 reductions was in the transport sector – both aviation and road transport. That’s according to a summary of feedback published by the Commission on Monday.

The consultation ran from the end of March to the end of June. A total of 879 responses were included in the summary, and further feedback was assigned to an individual campaign. Around 53 percent of the responses came from EU citizens, 28 percent from companies and trade associations. In a comparison of EU countries, the most responses came from Germany, at 27 percent.

With regard to the agricultural sector, a large majority of respondents believed that soft approaches such as information campaigns and more technical innovations were unsuitable for driving forward the transformation. If the EU were to introduce a CO2 price for the agricultural sector, a majority want it to be levied at the level of food companies or fertilizer manufacturers rather than farmers or consumers.

A majority also favored three separate climate change targets for greenhouse gas reduction, nature-based removals, and industrial CO2 removals from the atmosphere. There was a slight preference for nature-based removals. A split emerged on the question of the importance of CO2 removal in general for climate neutrality in 2050. Accordingly, science, the public sector and companies saw a high significance. ber

Due to insufficient climate protection in the transport and building sectors, Germany faces costs of between €15 and €30 billion by 2030, according to experts. The sum results on the one hand from the rules of the EU burden-sharing regulation, which regulates reduction targets for sectors not subject to emissions trading (ETS) for energy and industry. On Tuesday, the German Expert Council for Climate Issues also presented its opinion on the German government’s draft 2023 climate protection program.

According to the study, the transport sector remains mainly responsible for Germany emitting significantly more greenhouse gases than envisaged in the Climate Protection Act by 2030. Industry and buildings are also expected to exceed their budgets. Overall, the Effort Sharing targets will be missed by a wide margin, according to the forecast. By 2030, Germany will therefore exceed them by 152 to 299 metric tons of CO2.

This quantity would have to be purchased bilaterally from other member states that exceed their targets. The cost of the corresponding certificates has not yet been determined, but experts believe it is likely to be in the same order of magnitude as in emissions trading. Germany would then have to pay the said €15 to €30 billion. mkr

Ukraine has received another €1.5 billion aid loan from the EU. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced Tuesday that it will help the Russia-attacked country keep the state running and repair infrastructure. “We are doing everything we can to support Ukraine,” she said.

The money is part of a loan program of up to €18 billion euros agreed by EU member states last December for this year. With the financial aid, the EU wants to enable the Ukrainian state to continue paying wages and pensions. It will also guarantee the operation of hospitals, schools and emergency shelters for resettled people. In addition, the money can also be used to restore infrastructure destroyed by the Russian war of aggression. This includes, for example, power lines, water systems as well as roads and bridges.

Despite the ongoing war, the loans are tied to 20 reform commitments and reporting obligations. These relate, for example, to the rule of law and the fight against corruption. Ukraine has up to 35 years to repay the money, which is scheduled to begin in 2033. The interest costs will be borne by the EU member states.

According to EU figures released on Tuesday, total EU support to Ukraine since the beginning of the war now amounts to about €76 billion. This includes financial, humanitarian and military support to Ukraine from the EU, member states and European financial institutions. In addition, it takes into account EU funds made available to member states to provide for Ukrainian war refugees.

To support Ukraine in the coming years, von der Leyen most recently proposed the establishment of a new financing instrument. It is to be endowed with up to €50 billion for grants and loans for the period 2024 to 2027. dpa

Germany and Estonia want to cooperate more closely than before in the fight against the climate crisis and increasing disinformation campaigns by Russia. The report by the German government’s Council of Experts on Climate Issues shows that “we all have to do more together. Joining forces to do so is absolutely necessary, especially in the European Union,” Minister for Foreign Affairs Annalena Baerbock (Greens) said Tuesday after a meeting with Estonia’s Foreign Minister Margus Tsahkna in Berlin. “Because this decade will decide whether the global community can still prevent the worst of global warming.”

Baerbock said she was very pleased that Estonia had joined the German-Danish group of friends for ambitious EU climate diplomacy on Tuesday. With Tsahkna, she said, she had discussed how the Baltic Sea could be made “a better main driver of our shared renewable energy supply”. There is huge potential in the expansion of offshore wind power, she said.

Baerbock said that new paths also need to be taken with hydrogen. In the future, Germany will have to import about two-thirds of its demand for green hydrogen. The Federal Republic therefore has an enormous common interest in infrastructure in the Baltic Sea region that connects Germany, the Baltic States, Finland and Sweden. Tsahkna said his country has ambitious plans for a green energy transition. Here, he said, Germany could be a source of learning.

Referring to the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine, Tsahkna said he admired the support provided by Germany. Baerbock said that Germany and Estonia could learn from each other in the fight against Russian disinformation. Estonia is a pioneer in this regard. They had agreed to coordinate even more closely on this and to exchange their respective expertise. dpa

The specter of deindustrialization is haunting Germany and Europe. Regardless of whether the fear is justified or exaggerated, the climate and energy policy transformation is now recognizably at a critical point: Investments are flowing abroad and location decisions are increasingly being made against Germany and Europe. Contrary to what politicians like to sell, the industrial transformation to climate neutrality is not a foregone conclusion, because the path to it is unstable.

There is a temporary conflict of objectives between one-sided climate protection and international competitiveness: deindustrialization sets in faster than climate-neutral technologies can be made competitive by expanding infrastructures and renewable energies. Purely industrial policy or market liberal approaches miss the problem. In fact, at its core, it is a regulatory task.

Climate protection efforts – even initially unilateral ones – are right and essential, but they must not lead to a loss of the country’s own competitiveness or to a mere shift of emissions abroad. On the contrary, they must increase competitiveness in the medium term as a result of the transformation, because only this expectation will ultimately attract urgently needed private capital to the transformation. It would be a disservice to climate protection if German and European industry were to be robbed of their global competitiveness at precisely this stage.

Instead, industry must prove that climate protection is technologically feasible and at the same time economically advantageous – and not at the price of market foreclosure, but precisely for an industrialized country that is in international competition. National climate neutrality through deindustrialization is possible, but globally pointless. A climate-neutral industry that internalizes a global external effect as a matter of political will must not suffer a global competitive disadvantage as a result, especially in the early phase of transformation when the necessary investments are to be made.

When you build a house, it is not enough that it is stable in its finished state. The house can only be built if it is stable at every stage of construction. Analogously, energy transition and climate neutrality must not only be stable in a target state, but must be so in every phase of the industrial transformation. Industrial base structures can be destroyed in a phase of instability even before the new stable equilibrium is reached. This is because if the stability and dynamics of the transformation are higher elsewhere, today’s investments will be redirected to other locations. And what is lost today will not return any time soon.

The location decisions currently made will predetermine future global value chains. This is all the more true in an environment shaped by geo-economic and industrial policy. The USA’s Inflation Reduction Act has decisively changed the rules of the game for industrial and technological transformation for Europe – particularly with regard to access to critical raw materials, the resilience of strategic key industries and technological innovation capability. German and European industry is thus approaching a dangerous tipping point.

In the future, only an industry that produces in a climate-neutral manner will be competitive, and conversely, industry will only be able to be sustainably climate-neutral if it is competitive. On the way to the goal, however, there is a conflict of objectives between climate protection and competitiveness. If progress is an undirected process, the path to the future can be left to the market alone as a discovery process. But there is no time for that. Industry must be made climate-neutral within a few years, and climate-neutral production must be made competitive.

What is needed, therefore, is not a classic industrial policy but a reliable regulatory framework that sets appropriate incentives on the market and creates stable expectations in competition. To avoid misallocations and distortions, measures must be limited in time and linked to conditions from the outset – if only to meet the requirements of EU state aid law – above all to investments in green technologies and the expansion of renewable energies. For if the problem is not ultimately solved in a market economy, there is a risk, as many fear, of permanent subsidization and endless spirals of intervention.

A kingdom for a government: After the elections in Spain created unclear majority conditions, King Felipe VI last night proposed the head of the conservative People’s Party, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, to form a government.

With this, the head of state first tasked the numerical winner of the July 23 elections with forming a government. Feijóo’s Partido Popular (PP) won 16 more seats than the Socialists (PSOE) of incumbent Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez.

Nevertheless, it is questionable whether Feijóo can succeed. Currently, in addition to his party’s seats (137), the PP leader also has those of the right-wing populist party Vox (33) and two seats from smaller parties, for a total of 172 deputies. “My chances of forming a government are only four deputies away from an absolute majority,” Feijóo explained.

For his part, Pedro Sánchez predicted that the debate over Feijóo’s inauguration would be a failure. “If Feijóo wants to hit the wall of reality, that is his right and his decision,” he said. However, so far Sánchez also does not have the support needed to form a government.

Now the debate and vote in the House of Representatives is pending. The date is to be announced shortly. Who will govern Spain in the future still seems open despite the King’s decision.

Frans Timmermans is leaving the EU Commission with immediate effect to become the leading candidate of the Social Democrats and the Greens in the upcoming elections in the Netherlands. Responsibility for the Green Deal will be taken over by Slovakian Commission Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced on Tuesday. His focus will be less on new legislative proposals than on the implementation of the agreed plans and the dialogue with industry, farmers and forest owners.

The CDU politician is thus using the departure of climate czar Timmermans to send a signal to her critics in the EPP and the business community. These had called for a regulatory pause in view of the many laws on climate protection and biodiversity. It was time to focus on implementing the rules that had been adopted, von der Leyen said. “Our priority is strengthening clean innovation in industry, modernizing our grids and infrastructure for the energy transition, and access to critical raw materials.”

It is still unclear what the new work order means for the few legislative initiatives that the authority still wanted to present in the legislative period ending in 2024. In the pipeline are, in particular, a law on sustainable food systems and the reform of the chemicals legislation REACH, which is unpopular in the industry.

Šefčovič will initially coordinate the Green Deal in the Commission as Executive Vice-President, as Timmermans has done up to now, and at the same time be responsible for individual laws as Climate Commissioner. However, he will relinquish this second task when the Dutch government nominates a suitable candidate to succeed Timmermans. It is still open who The Hague will propose. The European Parliament also still has a say.

Šefčovič brings with him a wealth of experience; the 57-year-old diplomat is already serving his third term at the Brussels-based authority. He will continue to be responsible for relations with the United Kingdom and Switzerland, as well as with the European Parliament and the Council. His good contacts in the other EU institutions could help to moderate the trilogues on difficult dossiers such as renaturation legislation and pesticide regulation, according to the Commission. The former energy Commissioner also brings with him previous technical knowledge.

Timmermans will leave without having fully completed the Green Deal, his major project as Vice-President of the Commission. The 62-year-old is leaving the agency altogether to join Dutch politics, he announced this evening. Earlier, the party alliance of PvdA and GroenLinks said nearly 92 percent of its members had voted in favor of the Social Democrat as its top candidate for the Nov. 22 general election.

Von der Leyen thanked Timmermans for his commitment to the goal of making Europe the first climate-neutral continent. The articulate politician had lobbied hard for the comprehensive package of laws on climate protection, biodiversity and pollution control, and also represented the EU in international climate negotiations. Timmermans knew the ropes in Brussels since his first term in the Commission under Jean-Claude Juncker from 2014 to 2019.

Timmermans threw himself into the arguments with verve – and thus increasingly became a red rag for his critics, especially in the European People’s Party. The conflict manifested itself in the Nature Restoration Law, which the EPP tried to prevent – ultimately without success. The text was eventually narrowly passed by Parliament, but in a significantly weakened version.

Another controversial proposal, the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation (SUR), is still being negotiated. With the Pesticides Regulation, the Commission wants to halve the use of pesticides by 2030 and completely ban pesticides of particular ecological concern.

Also pending is the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED), through which the Commission aims to curb pollutant emissions from industrial facilities, including large livestock operations.

It was also previously planned that the EU executive would present its proposal for a Sustainable Food Systems Act in the third quarter of 2023. Originally billed as overarching legislation for the Farm to Fork strategy – the agriculture and food component of the Green Deal – environmentalists fear the proposal could end up focusing more on food safety. Till Hoppe and Claire Stam

Margrethe Vestager from Denmark is currently Vice-President of the EU Commission and responsible for competition, while Nadia Calviño from Spain is Finance Minister in Madrid. The other candidates are EIB Vice-President Teresa Czerwinska from Poland, EIB Vice-President Thomas Östros from Sweden and former Italian Minister of Economy Daniele Franco. All candidates must go through a selection process run by the Bank to determine whether they are suitable for the roles on the EIB’s Management Committee.

The assessment is carried out by an Advisory Committee on Appointments, which consists of five members who are independent of the EIB. According to information available to Table.Media, the screening process has now been completed for four candidates, with only the assessment of the Spaniard Calviño still pending. However, this is expected to be completed soon – a special meeting of the external panel in the first week of September is being negotiated. If the candidates are confirmed by their governments after submission of the overall assessment, the candidacies will be official.

For Vestager, according to the internal rules of the EU Commission, this would mean that she would have to rest her office from that point on. The first debate at the level of the EU finance ministers, who are also the bank’s governors, is scheduled for the informal meeting of ministers on Sept. 16 in Santiago de Compostela, Spain. However, according to the information, a decision is not yet expected for this debate.

However, an agreement on the Hoyer successor at the informal Ecofin meeting would be very ambitious, they said. More likely would be an agreement at the regular Ecofin a month later. This would be sufficient time for the bank to fill the top job in time for Jan. 1, 2024, due to the subsequent internal processes. The decision-making process has been moderated by Belgian Finance Minister Vincent van Peteghem, who is currently Chairman of the EIB’s Board of Directors.

Van Peteghem is reportedly pushing for a consensual solution. However, if no consensus is reached among the member states, the successor to Hoyer, who headed the EU’s main bank for twelve years, would have to be decided by a qualified majority. The new president would then have to unite 18 member states and 68 percent of the subscribed capital. However, there are certainly possibilities of reaching a consensual solution.

One option, for example, would be to leave Vestager in charge of the bank and install Calviño as “Executive Vice-President” along the lines of the Commission. Installing Calviño as a strong Vice-President with an important portfolio would be possible, as it is Spain’s turn to provide the member of the EIB’s Board of Directors from January. There are also other management personnel changes at the turn of the year. Bulgarian Lilyana Pavlova and Belgian Kris Peeters are leaving the governing body, while Nicola Beer is joining as a new German Vice-President.

The personnel changes offer a good starting position for a comprehensive reassignment of responsibilities. Who ultimately wins the race at the top is likely to shape the strategic direction of the bank over the coming years. In this context, the Dane Vestager is seen as having a technology-savvy approach, which goes hand in hand with higher risks and smaller financing volumes. Calviño, on the other hand, is associated with rather lower-risk, large-volume projects of the kind the bank used to finance with its extensive infrastructure projects.

The reason given is that it is currently worthwhile for a number of southern EU countries to finance projects via the bank instead of paying for them out of their own budgets, as the national refinancing costs are higher than those of the EIB. However, the future direction of EIB policy outside the EU remains open for both candidates. The outgoing president, Hoyer, has given high priority to the bank’s external presence and has set up a separate strategic unit within the bank, EIB Global, for this purpose. This unit is to play a leading role in project financing for EU foreign policy over time.

The 15th summit of the BRICS countries began on Tuesday at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg. It could herald a new era in which world politics can no longer ignore the BRICS movement. In addition to government representatives of the five member states Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, numerous other countries will be represented. The BRICS countries are expected to grow mightily: The inclusion of Argentina, Egypt, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia is considered assured, according to Reuters. More than 40 countries have shown interest in membership, including Iran, Ethiopia, Cuba, DR Congo and Kazakhstan. Twenty-two states have already submitted a formal application.

With what goal was BRICS founded?

Originally, Jim O’Neill, then an economist at the US investment bank Goldman Sachs, developed this concept more than 20 years ago. The BRICS countries had nothing in common politically, economically, culturally or historically. Yet it was supposed to unite rapid economic growth. That was indeed the case. Today, according to South African government figures, the five states account for 42 percent of the world’s population and 23 percent of the world’s economic output. This brings the BRICS countries closer to the developed countries in economic terms. The G7 group of the old industrialized nations – the USA, Germany, France, Italy, Great Britain, Canada and Japan – accounts for 44 percent of global economic output and ten percent of the world’s population.

What has brought about the discussion of BRICS enlargement?

The BRICS countries Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa seek an end to the existing world order and the dominance of the West, with the aim of becoming a counterweight in world politics. Based on their experience, they consider political relations with the powerful US to be unpredictable, especially due to the foreign policy doctrine according to which “democratic ideals” and a neoliberal economic policy are enforced by force if necessary.

What are China’s interests?

The war in Ukraine has greatly increased interest in BRICS, and Russia in particular is determined to use the group of states for its own benefit. Moscow sees a strengthened organization as a way to circumvent Western sanctions. It’s a similar story with China. With BRICS, Beijing is trying to build new structures in international politics. At the heart of its power ambitions is the “Global Security Strategy” unveiled last year. According to this concept, Beijing defines itself as a peace power that guarantees stability and development, in contrast to the US and its allies, who provoke wars and crises.

China derives conclusions from transatlantic unity for a possible conflict with Taiwan: While Beijing believes it cannot rely on Western, democratic states, it sees an opportunity in the Global South to avert isolation in the event of a conflict.

And what are Russia’s interests?

Russia wants to continue working on nothing less than a “democratization of international life,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov wrote in a guest article for the South African magazine Ubuntu at the start of the summit. Russia, he said, is working for “an architecture of international relations based on indivisible security as well as civilizational diversity and enabling equal developments for all members of the world community, without distinction”. Lavrov speaks of “tectonic shifts” in the world, of the loss of importance of the dollar, accuses the West collectively of racism, and sees a “fairer, multipolar world order emerging – thanks to BRICS and the expected expansion of the organization”.

The summit itself is at the same time a minor ignominy for Russia, because Russian President Vladimir Putin will only be present via video. Otherwise, South Africa would have had to arrest him during a visit and extradite him to the International Criminal Court. Putin did not take this risk. Lavrov wrote as little about this as he did about Ukraine, which Russia invaded. But Lavrov’s tenor was picked up by important Russian media, quoted experts in Russian newspapers praising the development of the multipolar world.

What is Africa’s position in this attempt at reordering?

For many African countries, the global confrontation between China, Russia and the USA offers an opportunity. They are being courted like never before, by the USA and Europe as well as by China and Russia. South Africa wants to take advantage of this momentum at the summit in Johannesburg. The country is primarily concerned with growth, sustainable development and inclusive multilateralism.

What makes BRICS attractive to new members?

The emerging countries in particular expect the BRICS to provide a counterweight to the multilateral institutions that emerged after the Second World War: above all the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. In these, the old powers of yesteryear have secured the greatest influence, so that the fast-growing countries in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa feel that they are not given enough consideration in these institutions.

In recent years, new institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank have emerged or existing ones such as the African Development Bank have been strengthened in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. But BRICS has emerged as the most powerful idea yet to challenge the existing world order.

Why are the BRICS countries striving for their own currency?

Dollar supremacy grants the US great privileges in the global economy. It can exclude countries such as Iran or Russia from access to US dollars. Also, central banks and governments almost inevitably have to invest at least part of their foreign exchange reserves in dollars. To do so, they usually buy US government bonds, the most liquid asset class in the world, and thus help finance the US government budget. Many BRICS countries refuse to do this.

However, the establishment of a new world reserve currency is likely to be the most ambitious project of the emerging countries. The new currency would have to be as liquid and as universally accepted as the dollar. Also, the issuer of a new world reserve currency would have to be a net debtor in the international financial markets to ensure that enough foreign exchange enters the world. Having a world currency also brings disadvantages. Under certain conditions, for example, there is the threat of uncontrolled inflation.

It is conceivable, however, that the BRICS will succeed in pushing back the dollar at certain points, for example in the trade of commodities such as oil or gold. Which currency – an existing one like the Chinese yuan or a new artificial currency – will benefit from this is an open question.

What is the role of the New Development Bank?

The New Development Bank (NDB) serves as a multilateral development bank for the BRICS countries, providing an alternative to the World Bank and IMF institutions. The idea for the bank stems from a proposal in 2012, when the BRICS countries first considered joint management of reserves. In 2014, the BRICS established the NDB and its sister institution, the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CAR). The current head of the NDB is the former president of Brazil, Dilma Roussef.

The NDB primarily finances development projects and infrastructure within the five BRICS countries and is thus intended as an alternative to Western-style development banks such as the World Bank. The CAR, on the other hand, is primarily intended as protection against international liquidity bottlenecks and is designed to protect the national currencies of the BRICS countries against global financial pressure. The $100 billion CAR is tasked with providing support in the event of actual or potential short-term balance of payments strains, making it primarily an alternative to the IMF.

Will this bank change international development assistance?

The New Development Bank could strengthen the role of the BRICS group in development policy and thus set new accents in international development aid. The BRICS countries see themselves in the tradition of the Bandung Conference, which took place in Indonesia in 1955 and from which the Non-Aligned Movement emerged. At that time, the participating countries were united by an anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist stance. This includes the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of a state. Thus, the BRICS countries today also reject a development policy of the kind pursued by the West, in which it uses financial support as leverage to impose political goals and values in the recipient countries. Christian von Hiller, Arne Schütte, Viktor Funk, Harald Prokosch

In the EU Commission’s consultation on the Union’s climate target for 2040, a majority of participants spoke out in favor of more speed in climate protection. The highest level of support for greater CO2 reductions was in the transport sector – both aviation and road transport. That’s according to a summary of feedback published by the Commission on Monday.

The consultation ran from the end of March to the end of June. A total of 879 responses were included in the summary, and further feedback was assigned to an individual campaign. Around 53 percent of the responses came from EU citizens, 28 percent from companies and trade associations. In a comparison of EU countries, the most responses came from Germany, at 27 percent.

With regard to the agricultural sector, a large majority of respondents believed that soft approaches such as information campaigns and more technical innovations were unsuitable for driving forward the transformation. If the EU were to introduce a CO2 price for the agricultural sector, a majority want it to be levied at the level of food companies or fertilizer manufacturers rather than farmers or consumers.

A majority also favored three separate climate change targets for greenhouse gas reduction, nature-based removals, and industrial CO2 removals from the atmosphere. There was a slight preference for nature-based removals. A split emerged on the question of the importance of CO2 removal in general for climate neutrality in 2050. Accordingly, science, the public sector and companies saw a high significance. ber

Due to insufficient climate protection in the transport and building sectors, Germany faces costs of between €15 and €30 billion by 2030, according to experts. The sum results on the one hand from the rules of the EU burden-sharing regulation, which regulates reduction targets for sectors not subject to emissions trading (ETS) for energy and industry. On Tuesday, the German Expert Council for Climate Issues also presented its opinion on the German government’s draft 2023 climate protection program.

According to the study, the transport sector remains mainly responsible for Germany emitting significantly more greenhouse gases than envisaged in the Climate Protection Act by 2030. Industry and buildings are also expected to exceed their budgets. Overall, the Effort Sharing targets will be missed by a wide margin, according to the forecast. By 2030, Germany will therefore exceed them by 152 to 299 metric tons of CO2.

This quantity would have to be purchased bilaterally from other member states that exceed their targets. The cost of the corresponding certificates has not yet been determined, but experts believe it is likely to be in the same order of magnitude as in emissions trading. Germany would then have to pay the said €15 to €30 billion. mkr

Ukraine has received another €1.5 billion aid loan from the EU. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced Tuesday that it will help the Russia-attacked country keep the state running and repair infrastructure. “We are doing everything we can to support Ukraine,” she said.

The money is part of a loan program of up to €18 billion euros agreed by EU member states last December for this year. With the financial aid, the EU wants to enable the Ukrainian state to continue paying wages and pensions. It will also guarantee the operation of hospitals, schools and emergency shelters for resettled people. In addition, the money can also be used to restore infrastructure destroyed by the Russian war of aggression. This includes, for example, power lines, water systems as well as roads and bridges.

Despite the ongoing war, the loans are tied to 20 reform commitments and reporting obligations. These relate, for example, to the rule of law and the fight against corruption. Ukraine has up to 35 years to repay the money, which is scheduled to begin in 2033. The interest costs will be borne by the EU member states.

According to EU figures released on Tuesday, total EU support to Ukraine since the beginning of the war now amounts to about €76 billion. This includes financial, humanitarian and military support to Ukraine from the EU, member states and European financial institutions. In addition, it takes into account EU funds made available to member states to provide for Ukrainian war refugees.

To support Ukraine in the coming years, von der Leyen most recently proposed the establishment of a new financing instrument. It is to be endowed with up to €50 billion for grants and loans for the period 2024 to 2027. dpa

Germany and Estonia want to cooperate more closely than before in the fight against the climate crisis and increasing disinformation campaigns by Russia. The report by the German government’s Council of Experts on Climate Issues shows that “we all have to do more together. Joining forces to do so is absolutely necessary, especially in the European Union,” Minister for Foreign Affairs Annalena Baerbock (Greens) said Tuesday after a meeting with Estonia’s Foreign Minister Margus Tsahkna in Berlin. “Because this decade will decide whether the global community can still prevent the worst of global warming.”

Baerbock said she was very pleased that Estonia had joined the German-Danish group of friends for ambitious EU climate diplomacy on Tuesday. With Tsahkna, she said, she had discussed how the Baltic Sea could be made “a better main driver of our shared renewable energy supply”. There is huge potential in the expansion of offshore wind power, she said.

Baerbock said that new paths also need to be taken with hydrogen. In the future, Germany will have to import about two-thirds of its demand for green hydrogen. The Federal Republic therefore has an enormous common interest in infrastructure in the Baltic Sea region that connects Germany, the Baltic States, Finland and Sweden. Tsahkna said his country has ambitious plans for a green energy transition. Here, he said, Germany could be a source of learning.

Referring to the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine, Tsahkna said he admired the support provided by Germany. Baerbock said that Germany and Estonia could learn from each other in the fight against Russian disinformation. Estonia is a pioneer in this regard. They had agreed to coordinate even more closely on this and to exchange their respective expertise. dpa

The specter of deindustrialization is haunting Germany and Europe. Regardless of whether the fear is justified or exaggerated, the climate and energy policy transformation is now recognizably at a critical point: Investments are flowing abroad and location decisions are increasingly being made against Germany and Europe. Contrary to what politicians like to sell, the industrial transformation to climate neutrality is not a foregone conclusion, because the path to it is unstable.

There is a temporary conflict of objectives between one-sided climate protection and international competitiveness: deindustrialization sets in faster than climate-neutral technologies can be made competitive by expanding infrastructures and renewable energies. Purely industrial policy or market liberal approaches miss the problem. In fact, at its core, it is a regulatory task.

Climate protection efforts – even initially unilateral ones – are right and essential, but they must not lead to a loss of the country’s own competitiveness or to a mere shift of emissions abroad. On the contrary, they must increase competitiveness in the medium term as a result of the transformation, because only this expectation will ultimately attract urgently needed private capital to the transformation. It would be a disservice to climate protection if German and European industry were to be robbed of their global competitiveness at precisely this stage.

Instead, industry must prove that climate protection is technologically feasible and at the same time economically advantageous – and not at the price of market foreclosure, but precisely for an industrialized country that is in international competition. National climate neutrality through deindustrialization is possible, but globally pointless. A climate-neutral industry that internalizes a global external effect as a matter of political will must not suffer a global competitive disadvantage as a result, especially in the early phase of transformation when the necessary investments are to be made.

When you build a house, it is not enough that it is stable in its finished state. The house can only be built if it is stable at every stage of construction. Analogously, energy transition and climate neutrality must not only be stable in a target state, but must be so in every phase of the industrial transformation. Industrial base structures can be destroyed in a phase of instability even before the new stable equilibrium is reached. This is because if the stability and dynamics of the transformation are higher elsewhere, today’s investments will be redirected to other locations. And what is lost today will not return any time soon.

The location decisions currently made will predetermine future global value chains. This is all the more true in an environment shaped by geo-economic and industrial policy. The USA’s Inflation Reduction Act has decisively changed the rules of the game for industrial and technological transformation for Europe – particularly with regard to access to critical raw materials, the resilience of strategic key industries and technological innovation capability. German and European industry is thus approaching a dangerous tipping point.

In the future, only an industry that produces in a climate-neutral manner will be competitive, and conversely, industry will only be able to be sustainably climate-neutral if it is competitive. On the way to the goal, however, there is a conflict of objectives between climate protection and competitiveness. If progress is an undirected process, the path to the future can be left to the market alone as a discovery process. But there is no time for that. Industry must be made climate-neutral within a few years, and climate-neutral production must be made competitive.

What is needed, therefore, is not a classic industrial policy but a reliable regulatory framework that sets appropriate incentives on the market and creates stable expectations in competition. To avoid misallocations and distortions, measures must be limited in time and linked to conditions from the outset – if only to meet the requirements of EU state aid law – above all to investments in green technologies and the expansion of renewable energies. For if the problem is not ultimately solved in a market economy, there is a risk, as many fear, of permanent subsidization and endless spirals of intervention.