We have been keeping count: You are reading the 500th issue of Europe.Table today. A good two years ago, on the morning of Aug. 3, 2021, we sent out the first issue. Back then, the circle of recipients was still manageable. Today, we reach thousands of readers, including many decision-makers in Brussels and Berlin. I can reveal one name: Ursula von der Leyen also reads us (as do her closest associates).

In this 500th issue, we are exceptionally changing our perspective: We are not, as usual, reporting soberly and objectively on European politics, but strictly subjectively from our everyday journalistic life. For example, about EU summits, whose news value is sometimes limited to the mirror fencing of some heads of state and government for the domestic audience. About marathon trialogues and nightly information gathering. About difficult-to-understand names for European legal acts. Or about men in gray suits and who they actually represent.

We hope this “peek into the workshop” brings you some interesting new insights. And maybe you’ll also enjoy our playlist, in which we’ve put together our soundtrack for Europe.

I wish you an enjoyable read and more beautiful summer days!

Every few weeks, the entrance hall of the Justus Lipsius building in Brussels becomes a newsroom: Hundreds of journalists bend over their laptops while their colleagues from the TV stations broadcast live from the stands. Notes on the specially lined-up tables reveal the origin: Asahi Shimbun from Japan is represented by two reporters. Al Jazeera is always there, as are Chinese agencies and broadcasters. In the course of a summit night, reporters repeatedly set up cameras on tripods. Correspondents from all over the world make announcements in languages that are not among the official languages of the EU.

The world is watching when Europe’s powerful meet. Next door, in the new Europa building, the heads of state and government walk along a rather long red carpet toward the waiting microphones and cameras. There, at the so-called doorstep, they place their messages. There, before the meetings even begin, they speak the sentences that will then run on the main news at home.

The crowds are large, but the news value of the summits is often manageable. But how do I, as a reporter, tell my audience (or my editorial team)? Most of us prefer to play the game. We make a lot of noise about little and gratefully pounce on every conflict, even if individual heads of government are only fighting it out in front of the mirror to please the home audience.

In the meantime, regular, informal, special and international summits are lined up like an alpine mountain range. It is obvious that there are not always hard decisions to report. Before the EU stumbled from one crisis to the next, the heads of state and government had met only four times a year. In February and March 2022, by contrast, they met four times in six weeks. Olaf Scholz and colleagues may like to exchange ideas frequently, even without deciding anything concrete. But the news value is sinking.

The second reason has a name: Charles Michel. Since the former Belgian Prime Minister became President of the Council, preparations and summits have often been chaotic. At the European Council at the end of June, Michel originally wanted to have the leaders discuss the reform of the Stability Pact – yet not even the finance ministers had bent over the many technical details. On the urgent advice of many government headquarters, he abandoned this plan.

Instead, Michel put Ukraine, China, competitiveness and migration on the agenda. Even the participants, however, did not know until the day before which questions he wanted to call on and when. Would he discuss China policy and EU competitiveness individually? Or both topics together? The debate would then have a different thrust, and the chiefs would need correspondingly different preparation by their sherpas.

Above all, Michel ignored warnings from Paris and Berlin, among others, that the summit would reignite the migration debate. Only shortly before, the interior ministers had negotiated a compromise that a majority could painfully support. So why rub salt into the wounds at the summit, especially since conclusions can only be adopted unanimously there?

Mateusz Morawiecki and Viktor Orbán did not miss a beat and turned the summit into a drama. This did little to change the substance and progress of the asylum package – but at least most journalists now had their story about this otherwise largely uneventful summit. The show must go on.

Statistically, most people are most productive early in the morning. Of course, there are also chronotypically nocturnal owls – but their numbers are limited. So one would also assume that concentrated work, constructiveness and the ability to compromise are more likely earlier in the day. Lack of sleep is known to put people in a bad mood.

This makes the scheduling of many trilogue negotiations all the more surprising. Often, when the EU Parliament, the Commission and the Council are heading for an agreement on a draft law, the last round of negotiations is scheduled for late in the evening. The idea: instead of negotiating through the whole day without any results, the negotiators are put under pressure to find a compromise by the advanced time of day. Who wants to sit all night in a stuffy conference room, drinking bad filter coffee and discussing with political opponents?

Compromise through sleep deprivation is particularly popular for controversial issues. Agreement is possible, but far from easy. Parliamentarians and member states must make concessions, some of them painful. And the Council, which is responsible for scheduling, apparently believes that this works best at night.

Between 6 and 8 p.m., things usually get underway. The negotiating teams have made final preparations over the course of the day. The Council Presidency agrees on possible compromise lines with the Permanent Representations of the Member States for the last time, and the parliamentary rapporteurs sound out where they want to be tough and where they see room for maneuver. After dinner, things get serious. Only the negotiators and their technical advisers are left in the room (and the secretariat, which puts the results of the negotiations on digital paper). No one knows how long they will sit here. But it is in their hands.

The Fit for 55 package has brought the negotiators particularly many night sessions. Whether it was the rules for charging infrastructure (AFIR), CO2 border adjustment (CBAM), CO2 reduction targets for member states (Effort Sharing) or the rules for sustainable marine fuels (Fuel-EU Maritime), agreement always came early in the morning.

And then there was the jumbo trilogue that brought agreement on the reform of the European Emissions Trading System (ETS) – and thus also on significant parts of the CBAM and the Climate Social Fund. An entire weekend was spent negotiating. Then, at 2 a.m. on Sunday night, the champagne corks popped. Beforehand, even a German state secretary was rung out of bed to end the German government’s resistance.

The trilogue on the Data Act shows that things can sometimes move quickly. While no agreement was in sight at 11 p.m., it was suddenly over shortly before midnight – the deal was done and everyone could go to bed. They were even quicker on the CO2 standards for passenger cars – better known as the combustion engine phase-out. Despite the controversy surrounding the issue, the agreement (which Federal Transport Minister Wissing later called into question again) came at 8:45 p.m.

Things went quite differently with the revision of the Renewable Energies Directive (RED III). The trilogue did not end until after 7 a.m. after a night of negotiations, which posed a problem for journalists. Normally, as a reporter, you are spoilt for choice: do you stay up late in the evening and hope for an early result so you can analyze the outcome before going to bed, or do you get up early and write quickly before most readers get up? In the case of RED, both would have been superfluous. For Europe.Table this was unfortunate, as our briefing is known to be published at 6 o’clock in the morning. Thus, the result came a few hours too late.

The nightly trilogues are also challenging for journalists. In a best case scenario, you have a contact in the negotiating circles and get an info as soon as an agreement is reached. Then you only have to find out the exact outcome of the negotiations to be able to analyze it. In some cases, however, you also have to rely on posts on X (formerly known as Tweets on Twitter) or press releases from the parties involved.

It’s not just trilogues that can last all night. Some council meetings can also drag on into the early hours of the morning. The Environment Council, for example, met until 2 a.m. at the end of June 2022. Council meetings start in the morning and should ideally end in the afternoon. But because the member states did not agree on the phasing out of internal combustion vehicles for quite some time, it went into overtime several times. Draft compromises circulated through the rooms and ministries in the capitals, and telephone lines between Brussels and Berlin ran hot until everyone was mostly happy in the end.

Since Council meetings usually include press conferences after the meeting and ministers give statements at so-called doorsteps, Frans Timmermans, Robert Habeck and Steffi Lemke appeared before the press that night. The journalists had held out, some had ordered pizza or had waited at home in front of the live broadcast until something stirred.

And all this just to give you, dear readers, the most important news from these nights of negotiations first thing in the morning, when Europe.Table flutters into your mailbox. Stay loyal to us and we’ll continue our night shifts for you.

What exactly is LULUCF, CBAM, CSAM, KARL and OLAF? The first thing everyone who deals with the European Union (EU) professionally needs to learn is the overwhelming flood of names and abbreviations. The Commission (COM) seems to take a real delight in inventing names and creating abbreviations for its acts, programs and institutions.

Actually, names help us to orient ourselves in the world. But the names of the EU are usually only understood by experts. They tend to exclude or scare people away rather than win them over to the issues and policies behind them.

The Green Deal is an exception. The catchy name says it all. “I can imagine something when hearing it”, explains Manfred Gotta. “The name also lends itself to headlines in the media. It settles better than an abbreviation.” Names are Gotta’s profession. For more than 40 years, he has been very successful in developing names for products and companies, creating value. With his creations Xetra, Megapearls or Twingo, almost everyone in Europe knows what is meant.

In contrast, Gotta says, abbreviations only work if people associate something emotional with them. For example, when it comes to the highly emotional topic of cars, people can remember that ABS is a braking system. But what are people supposed to do with LULUCF (Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry)?

The abbreviation AI for the hotly debated topic of artificial intelligence, on the other hand, no longer needs an explanation. Even people who can’t explain the abbreviation GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformers) talk about ChatGPT.

CSAM, for example, is different. With this, the EU wants to take action against “Child Sexual Abuse Materials (CSAM)” in order to better protect children on the Internet. What could be more emotional? Yet the acronym doesn’t work. Others call the legislative project chat control – and suddenly everyone in Germany knows what it’s all about – and recall the debate.

CSAM is therefore also an example of the fact that the Commission already takes sides or sets a direction with the naming, if it is not absolutely neutral. CSAM also shows that abbreviations do not work in all languages. And finally, the abbreviation also shows how easy it is to confuse legal acts, for example when one is called CSAM and the other CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism).

Yet CBAM, with the BAM at the end, at least has a powerful sound. “Bam, that’s what my grandchild always says when something falls down”, Gotta recalls. “It makes me think of a conflict situation rather than regulation to reduce emissions.” Besides the Green Deal, all the examples the editors sent to the expert fail.

Fit for 55? “What’s that supposed to be”, Gotta asks. “A gym or a gum?” He thinks a climate change package with a goal of reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030 “deserves a real name”. A name that can’t be misunderstood or even offensive, and that doesn’t bypass people.

He can’t just pull a name like that out of thin air. Thorough research is needed beforehand. “Professional branding”, Gotta says, “is composed of rational and non-rational values that are identically represented by the name nationally, European, or internationally.”

REACH, for example, sounds like a name, but it is an acronym (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals). This makes no sense as a name or as an abbreviation for a European regulation, since it does not evoke any association with a chemicals regulation in English and is understood differently in other countries.

Even the abbreviation KARL for the revision of the directive on the treatment of urban wastewater can be remembered by German native speakers. “But it’s superfluous”, says Gotta. For the general public, it is not interesting anyway, and if it is, the EU Wastewater Directive is still clearer. Especially since the directive is not called KARL but UWTTD in English. The European Anti-Fraud Office is called OLAF. This only makes sense in French: Office Européen De Lutte Antifraude.

But what makes a good name – apart from the fact that it has to work internationally? Why do names like Chiquita or Twingo work? “None of the names communicates through its phonetics, associations or content elements which area it comes from or what benefits it promises”, explains Gotta. Nevertheless, the names unmistakably represent a very specific product everywhere. “You have to create uniqueness“, explains Gotta.

The important thing, he says, is to cast a name first. “We learn names every day from childhood”, says the copywriter. And like a business card, he says, you can then translate its function in many languages under the name. “Then people all over Europe associate the same thing with that name.” For example, Tabasco is a hot chili sauce everywhere.

Finally, “Only the laws that are really important to people should be given a name”, Gotta advises the Commission. “Sounding names are especially easy to remember.” On that, a Dujardin.

Aug. 8, 2023; 9 a.m.-3:45 p.m., online

BMI, Seminar Sustainable public procurement

The Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (BMI) offers training for authorities and institutions at federal, state and local level on the basics, legal framework and implementation of sustainable procurement. INFO & REGISTRATION

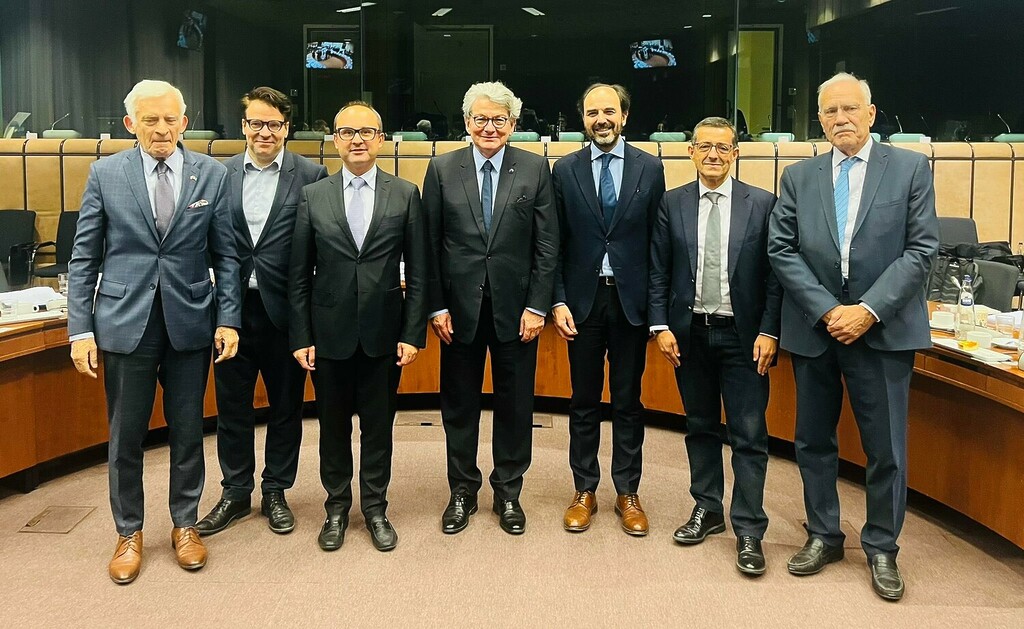

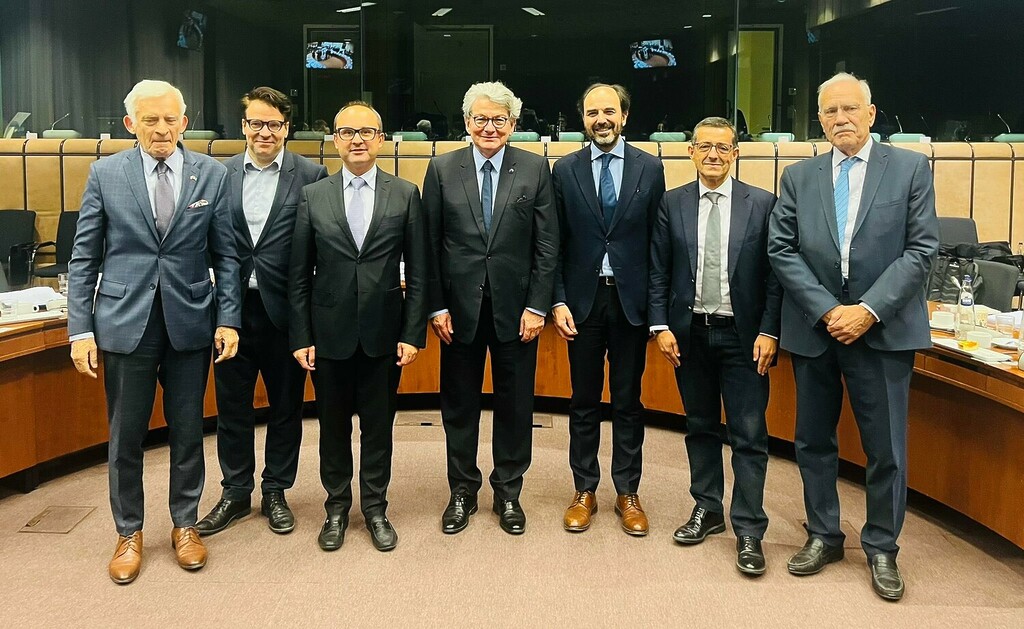

When I started writing about EU politics for Table.Media, I was surprised. In 2022, when photos of all-male groups in decision-making positions had long since reaped huge shitstorms, I attended events and panel discussions where only men spoke on stage. The only distinguishing feature between them was the various color variations of their ties.

“Well, with these topics, I guess that’s the way it is…”, I thought. Raw materials, circular economy – there just aren’t that many women in industry to report on. But why does this seem obvious to me? In a world that is undergoing rapid change in all areas of life, the clocks in the spectrum of political and economic contexts seem to tick much more slowly.

Following this impression, I asked my colleagues. The majority of our editorial team members actually see the perspectives of men more often considered in Europe.Table than those of women.

A feeling that also corresponds to the balance: Two-thirds of the people portrayed in Europe.Table so far are male. This section presents people whose function and work are – or should be – of interest to our readers. Certainly, there could be more women among them.

This picture reflects a global trend: Women are significantly less present in the media than men. The Global Media Monitoring Project regularly analyzes news from print, radio, television, the Internet and Twitter under the title “Who Makes the News?” The most recent evaluation of news coverage in Europe from 2020 showed that only 28 percent of the sources cited in traditional and digital media were women. Women were most likely to serve as sources in articles about gender-related topics. Women were least likely to be quoted in reports about politics and governments (22 percent). They were most likely to serve the purpose of providing eyewitness accounts or public opinion, rather than appearing as experts.

In the EU cosmos, the focus of our reporting, a lot has ostensibly changed in recent years: Ursula von der Leyen is the first woman to hold the most powerful EU post at the head of the Commission (and thus receives a lot of media attention). For the first time, the Commission has equal numbers of women and men, including for the first time a female Equal Opportunities Commissioner, Helena Dalli of Malta. The EU Parliament is also headed for the first time by a woman, Roberta Metsola.

But the figures behind the radiance of these publicly visible figures speak a different language: men continue to dominate leadership positions in the EU institutions. In the EU Parliament, the gender ratio is 60 to 40 percent.

In the largest companies in the EU, only one-third of management positions are held by women. Most executive boards now have at least one woman on them. But only under ten percent of CEOs are women. In a way, it seems logical that this is reflected in the media.

So what can we do to make our reporting more balanced? Of course, we have no influence on which person holds a particular office. EU Commissioners, MEPs, heads of state and government – they are all elected to their positions, whose role should also be legitimized from a journalistic perspective by their qualifications and not by their gender.

In view of the parity claim, the question arises as to whether the still predominant majority of male-occupied positions is also based on a traditional assessment of aptitude that assigns men per se greater competence in certain subject areas. This also seems to promote reporting that is different for men and women.

Journalists should therefore also ask themselves whether we report differently on female protagonists than on male ones. When female politicians make it into the headlines, it is often accompanied by sexism and stereotypes. Former Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin, for example, has become interesting to the media primarily because of her dance video. At a meeting Marin had with then-New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern last year, a journalist asked the two female politicians, “Are you just meeting because you’re similar in age and therefore have common interests?”

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) recently released a toolkit to raise awareness of just such issues and promote more gender-equitable political coverage. “The news media still has a long way to go to represent cisgender and transgender women in leadership in an appropriate way, and every single effort counts“, it says.

Journalists and editors also have the opportunity to ensure more balance when selecting experts for quotes, portraits and interviews. There are tools for this: LMU Munich, for example, uses the FemConsult database to place female scientists in leadership positions. The AcademiaNet database of the Robert Bosch Stiftung and Spektrum der Wissenschaft lists thousands of top female researchers from various disciplines.

Gender parity has not only a numerical dimension, as the European Institute for Gender Equality writes, but also a substantial one: It refers to the equal contribution of women and men to every dimension of life, private and public.

“There is a gender angle to every story”, every story has a gender dimension, writes the Global Media Monitoring Project. Even the big, current issues: Climate policy, raw materials supply, due diligence, digitalization. The UN Development Program reports, for example, that “the effects of climate change perpetuate and reinforce structural inequalities, such as those between women and men”.

Female and male journalists decide whose perspectives they present in their articles, which topics and people they help onto the public stage. This “gatekeeper” function and journalistic quality standards also call for a balance of male, female, more diverse perspectives. This includes a responsibility at the individual level. For all writers. And for me, too.

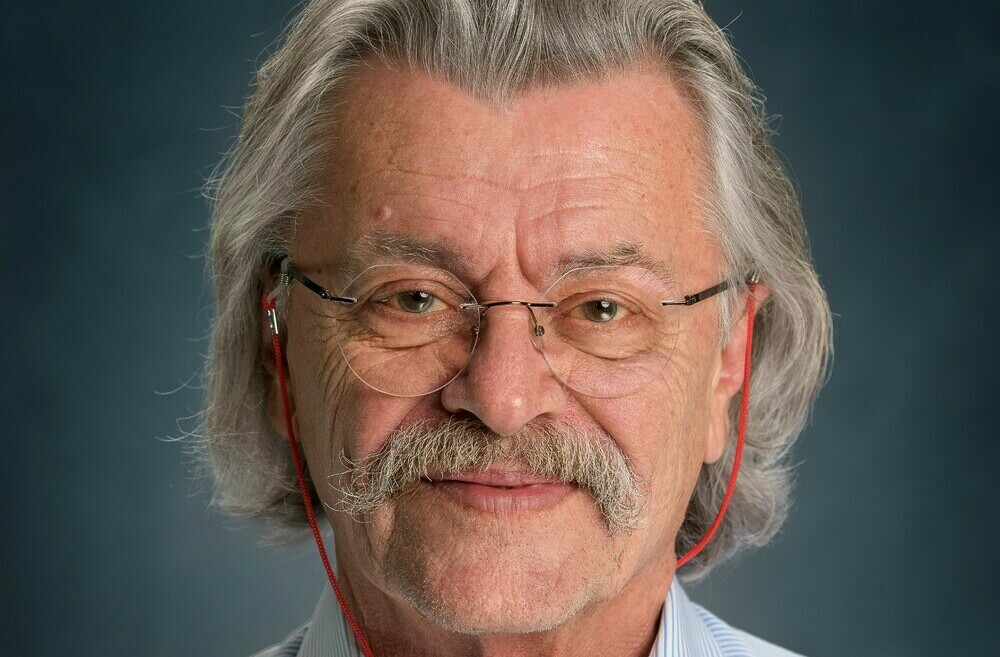

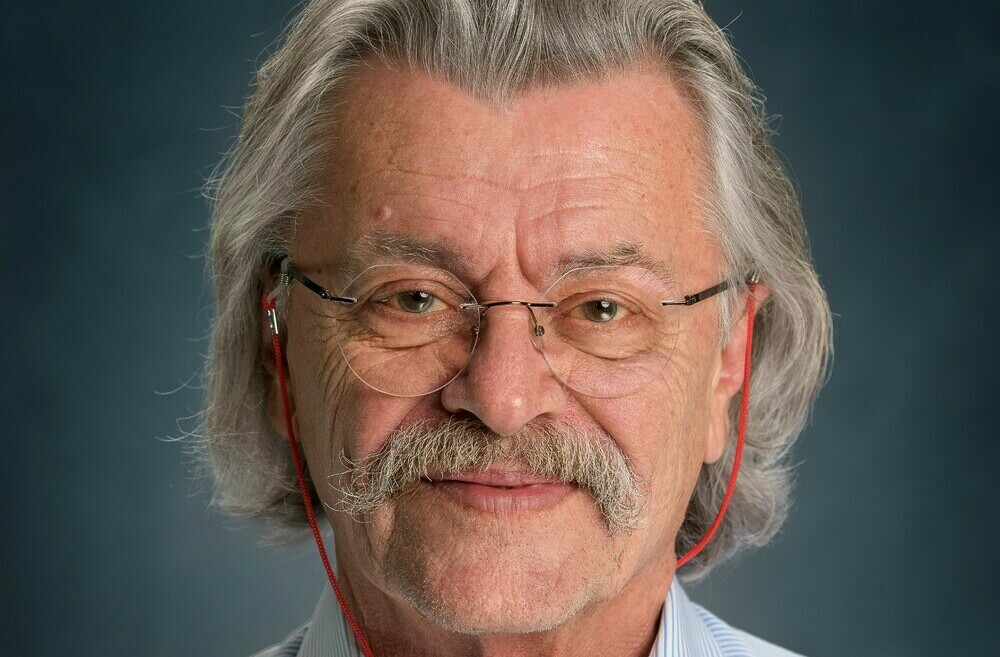

There is no one who has followed the events in the directly elected representation of the EU citizens from the beginning until today as closely as Bernd Posselt. He was there when the first directly elected EU Parliament met in Strasbourg on July 17, 1979. At that time he was 23 years old and assistant to Otto von Habsburg, the long-time MEP for the CSU and son of the last Austro-Hungarian emperor. Posselt himself moved into the European Parliament for the CSU in 1994 and was involved in the Foreign Affairs Committee and security policy issues.

He was a member of the house for 20 years. Since he missed re-election in 2014, he is the first on the CSU’s list of successors. Presumably, the 68-year-old, who was born in Pforzheim and is a trained journalist, will also end up in seventh place again on the CSU’s European list in the fall. Presumably, this will again be the first place to move up.

Posselt had to give up his access pass as a member of the European Parliament (MEP) almost ten years ago. But he has continued to be present ever since – especially during the Strasbourg session weeks. As an ex-MEP, he continues to have access to the House. But unlike other ex-MEPs, he has not used this access to influence his former colleagues as a lobbyist, but rather for political work. Posselt advises EPP parliamentary group leader Manfred Weber on foreign policy, writes books and monitors European politics. Since 1998, he has been head of the non-partisan Paneuropa Union, whose origins date back to the 1920s.

Somehow Posselt has not stopped being a deputy. He is present in Strasbourg, more present than many a deputy who has received a mandate from the voters. He is not allowed to vote and does not sit down in the plenum. But he is present and, apart from illness, has probably not missed a single sitting in Strasbourg since July 1979. Back then, when Posselt lost his seat in Parliament and still went to Strasbourg, articles appeared about it that bore mocking features.

“I’ve read all that”, Posselt reports. But he is sticking to his mission because – in his case, the expression is probably apt – he is inspired by the European idea like hardly any other politician. He joined the CSU when he was 20 years old. The occasion was Franz-Josef Strauß’s speech entitled “Europe can wait no longer”. Posselt says: “Millions of people are volunteering for Europe, why shouldn’t I do the same?”

Posselt was an assistant, then he became a Member of Parliament, meanwhile his role is best described as chronicler of the European Parliament at its headquarters in Strasbourg. There is no one who can tell more knowledgeably about its history. He has Louise Weiss’ speech at the ready, which the politician, journalist and feminist gave at the first session when she was a senior president: “She demanded that we don’t just need European tractor seats, but European people.”

Posselt’s parents came from the Sudetenland and Styria. He took an early interest in Eastern and Central Europe and can be proud of the fact that Putin banned him from entering Russia back in 2015 because of his commitment to human rights.

He is an expert on the architecture and building history of the Parliament. So he can tell about how at the Brussels seat of the Parliament the committees met partly in rented rooms. He vividly describes the symbolism that the legendary international office “architecturestudio” perpetuated in the Strasbourg Parliament building.

The building, which was occupied in 1999 after the election and cost €275 million at the time, stands very deliberately on the spot where the Alsatian Ill meets the canal that connects the Marne with the Rhine. “Three seas are accessible by water from here”, Posselt knows. The glass stands for the transparency of European democracy, he says. The plenary hall is designed like an amphitheater. At several points, visitors have a view of Strasbourg Cathedral.

Posselt also tells of May 1, 2004 and the first EU enlargement to the east. At that time, former Solidarność leader and later president of Poland, Lech Wałęsa, came to Strasbourg for the ceremony. “A pole for the Polish flag was erected at the main entrance to Parliament, made at the former Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk.” Visitors to the Parliament to this day will find the symbol of the formerly banned trade union, whose resistance ushered in the collapse of communism, on the pole.

Posselt is happy to share his knowledge. Although he is one of the few people who do not use a cell phone to this day, he is surprisingly easy to reach. Why he doesn’t have a cell phone? “I want to work creatively, so it would just get in the way.”

Europe is more than the EU. Much more. For us, Europe is also an attitude towards life. And how could we express that more beautifully and emotionally than with music? That’s why members of the Europe.Table editorial team have put together a playlist to mark our 500th issue, with our soundtrack for Europe.

We begin, naturally, with the “Ode to Joy“. Here we have chosen a recording of the London Symphony Orchestra. It is a pity that the British currently have little reason for joy. A colleague even confessed that occasionally tears come to their eyes when they hear the European anthem – but they will remain anonymous, of course.

Then we selected some of the tracks on our playlist by name, just as Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton did for the Raw Materials Act, for example. Breton is apparently convinced that he can communicate European laws better with musical accompaniment. He has already created playlists for various pieces of legislation. This inspired Leonie Düngefeld to select songs with the following words in the title:

Spain, which currently holds the Presidency, also created a playlist at the beginning of its term that we think is worth listening to.

We selected the remaining titles according to personal criteria. The first thing Clara Baldus thought of when she thought of Europe and music was the Eurovision Song Contest. That’s how Loreen with Euphoria ends up on our playlist.

Lukas Scheid likes to travel through Europe and through music he gets different ideas about his travel destinations. Thus, he had to listen to Vajze e bukur nga kurbeti by Bledar Alushaj on repeat while hitchhiking through Albania in a car. Since Albania is a candidate country, the song may serve as a musical sample.

Northern Macedonia is also applying. While Stakleni Noze by Funk Shui was playing, Lukas Scheid sat with young Macedonians over a beer in Mavrovo National Park. They played each other their favorite songs in the national language. Norway, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Sweden have also left their musical mark on his personal playlist. Europe Is Lost by Kae Tempest is the rap he listened to when he lived in the UK during the Brexit.

The background of Norwegian Erlend Øye, who founded the band Kings of Convenience in his native Bergen before starting his second band, Whitest Boy Alive, in Berlin, is downright pan-European. He has since emigrated to Sicily, where he focuses on his solo career, making guitar pop with the Sicilians of La Comitiva. This song La Prima Estate is about the freedom of the first summer after the Maturità, the Italian high school diploma. A recommendation from Leonard Schulz.

When he lived in Istanbul, he often heard musicians playing rembetiko, the “Greek blues.” The compilation Songs of Smyrna (today’s Izmir), with songs like Baxe Tsifliki, remind Leonard Schulz how closely the countries are linked culturally. And he often heard the brass band Fanfare Ciocărlia from Romania – represented here by Iag Bari – during the Balkan music boom in Berlin in the 00s.

When Markus Grabitz thinks of Europe musically, the song Göttingen by the French chansonnière Barbara comes to mind. It was written after a concert she gave in the early 1960s in the city, which had been unknown to her until then, and during which she came into contact with the Germans. It later became the anthem of reconciliation between the former hereditary enemies. She sings, “Let this time never return, and never more hate destroy the world, there are people I love living in Göttingen, in Göttingen…” Chancellor Gerhard Schröder incorporated a passage of the song’s lyrics into his speech on the 40th anniversary of the Élysée Treaties and received much applause for it. No one before or after Barbara has ever pronounced Göttingen so charmingly.

In Putain, Flemish rocker and singer-songwriter Arno Hintjens sings as a refrain: “Putain, putain, c’est vachement bien, nous sommes quand même tous des Européens.” In English, that means something along the lines of: “C-word, c-word, it’s true, we’re all Europeans despite everything.” He later rewrote the 2003 song to protest the Brexit that had been decided but not yet consummated, since then it has also had the verses: “Bye-bye Brexit, bye-bye Brexit, We’re still gonna eat fish & chips all.”

For Corinna Visser, freedom and borderless travel are among Europe’s most important achievements and strengths. She has experienced in other parts of the world what borders can do. That’s why, towards the end of the Europe.Table playlist, it gets cheesy again with Wind of Change by the Scorpions, then a bit weird with Brennerautobahn by Roy Bianco & Die Abbruzanti Boys and finally culinary with Carbonara by Spliff.

Then a look at our neighbors: The Spanish are currently very keen on the rapper Quevedo with Columbia. The French like C’est carré le S by Naps. Italy listens to Alfa with bellissimissima <3. Finally: Freedom by George Michael. Have a great time listening. The Editors

We have been keeping count: You are reading the 500th issue of Europe.Table today. A good two years ago, on the morning of Aug. 3, 2021, we sent out the first issue. Back then, the circle of recipients was still manageable. Today, we reach thousands of readers, including many decision-makers in Brussels and Berlin. I can reveal one name: Ursula von der Leyen also reads us (as do her closest associates).

In this 500th issue, we are exceptionally changing our perspective: We are not, as usual, reporting soberly and objectively on European politics, but strictly subjectively from our everyday journalistic life. For example, about EU summits, whose news value is sometimes limited to the mirror fencing of some heads of state and government for the domestic audience. About marathon trialogues and nightly information gathering. About difficult-to-understand names for European legal acts. Or about men in gray suits and who they actually represent.

We hope this “peek into the workshop” brings you some interesting new insights. And maybe you’ll also enjoy our playlist, in which we’ve put together our soundtrack for Europe.

I wish you an enjoyable read and more beautiful summer days!

Every few weeks, the entrance hall of the Justus Lipsius building in Brussels becomes a newsroom: Hundreds of journalists bend over their laptops while their colleagues from the TV stations broadcast live from the stands. Notes on the specially lined-up tables reveal the origin: Asahi Shimbun from Japan is represented by two reporters. Al Jazeera is always there, as are Chinese agencies and broadcasters. In the course of a summit night, reporters repeatedly set up cameras on tripods. Correspondents from all over the world make announcements in languages that are not among the official languages of the EU.

The world is watching when Europe’s powerful meet. Next door, in the new Europa building, the heads of state and government walk along a rather long red carpet toward the waiting microphones and cameras. There, at the so-called doorstep, they place their messages. There, before the meetings even begin, they speak the sentences that will then run on the main news at home.

The crowds are large, but the news value of the summits is often manageable. But how do I, as a reporter, tell my audience (or my editorial team)? Most of us prefer to play the game. We make a lot of noise about little and gratefully pounce on every conflict, even if individual heads of government are only fighting it out in front of the mirror to please the home audience.

In the meantime, regular, informal, special and international summits are lined up like an alpine mountain range. It is obvious that there are not always hard decisions to report. Before the EU stumbled from one crisis to the next, the heads of state and government had met only four times a year. In February and March 2022, by contrast, they met four times in six weeks. Olaf Scholz and colleagues may like to exchange ideas frequently, even without deciding anything concrete. But the news value is sinking.

The second reason has a name: Charles Michel. Since the former Belgian Prime Minister became President of the Council, preparations and summits have often been chaotic. At the European Council at the end of June, Michel originally wanted to have the leaders discuss the reform of the Stability Pact – yet not even the finance ministers had bent over the many technical details. On the urgent advice of many government headquarters, he abandoned this plan.

Instead, Michel put Ukraine, China, competitiveness and migration on the agenda. Even the participants, however, did not know until the day before which questions he wanted to call on and when. Would he discuss China policy and EU competitiveness individually? Or both topics together? The debate would then have a different thrust, and the chiefs would need correspondingly different preparation by their sherpas.

Above all, Michel ignored warnings from Paris and Berlin, among others, that the summit would reignite the migration debate. Only shortly before, the interior ministers had negotiated a compromise that a majority could painfully support. So why rub salt into the wounds at the summit, especially since conclusions can only be adopted unanimously there?

Mateusz Morawiecki and Viktor Orbán did not miss a beat and turned the summit into a drama. This did little to change the substance and progress of the asylum package – but at least most journalists now had their story about this otherwise largely uneventful summit. The show must go on.

Statistically, most people are most productive early in the morning. Of course, there are also chronotypically nocturnal owls – but their numbers are limited. So one would also assume that concentrated work, constructiveness and the ability to compromise are more likely earlier in the day. Lack of sleep is known to put people in a bad mood.

This makes the scheduling of many trilogue negotiations all the more surprising. Often, when the EU Parliament, the Commission and the Council are heading for an agreement on a draft law, the last round of negotiations is scheduled for late in the evening. The idea: instead of negotiating through the whole day without any results, the negotiators are put under pressure to find a compromise by the advanced time of day. Who wants to sit all night in a stuffy conference room, drinking bad filter coffee and discussing with political opponents?

Compromise through sleep deprivation is particularly popular for controversial issues. Agreement is possible, but far from easy. Parliamentarians and member states must make concessions, some of them painful. And the Council, which is responsible for scheduling, apparently believes that this works best at night.

Between 6 and 8 p.m., things usually get underway. The negotiating teams have made final preparations over the course of the day. The Council Presidency agrees on possible compromise lines with the Permanent Representations of the Member States for the last time, and the parliamentary rapporteurs sound out where they want to be tough and where they see room for maneuver. After dinner, things get serious. Only the negotiators and their technical advisers are left in the room (and the secretariat, which puts the results of the negotiations on digital paper). No one knows how long they will sit here. But it is in their hands.

The Fit for 55 package has brought the negotiators particularly many night sessions. Whether it was the rules for charging infrastructure (AFIR), CO2 border adjustment (CBAM), CO2 reduction targets for member states (Effort Sharing) or the rules for sustainable marine fuels (Fuel-EU Maritime), agreement always came early in the morning.

And then there was the jumbo trilogue that brought agreement on the reform of the European Emissions Trading System (ETS) – and thus also on significant parts of the CBAM and the Climate Social Fund. An entire weekend was spent negotiating. Then, at 2 a.m. on Sunday night, the champagne corks popped. Beforehand, even a German state secretary was rung out of bed to end the German government’s resistance.

The trilogue on the Data Act shows that things can sometimes move quickly. While no agreement was in sight at 11 p.m., it was suddenly over shortly before midnight – the deal was done and everyone could go to bed. They were even quicker on the CO2 standards for passenger cars – better known as the combustion engine phase-out. Despite the controversy surrounding the issue, the agreement (which Federal Transport Minister Wissing later called into question again) came at 8:45 p.m.

Things went quite differently with the revision of the Renewable Energies Directive (RED III). The trilogue did not end until after 7 a.m. after a night of negotiations, which posed a problem for journalists. Normally, as a reporter, you are spoilt for choice: do you stay up late in the evening and hope for an early result so you can analyze the outcome before going to bed, or do you get up early and write quickly before most readers get up? In the case of RED, both would have been superfluous. For Europe.Table this was unfortunate, as our briefing is known to be published at 6 o’clock in the morning. Thus, the result came a few hours too late.

The nightly trilogues are also challenging for journalists. In a best case scenario, you have a contact in the negotiating circles and get an info as soon as an agreement is reached. Then you only have to find out the exact outcome of the negotiations to be able to analyze it. In some cases, however, you also have to rely on posts on X (formerly known as Tweets on Twitter) or press releases from the parties involved.

It’s not just trilogues that can last all night. Some council meetings can also drag on into the early hours of the morning. The Environment Council, for example, met until 2 a.m. at the end of June 2022. Council meetings start in the morning and should ideally end in the afternoon. But because the member states did not agree on the phasing out of internal combustion vehicles for quite some time, it went into overtime several times. Draft compromises circulated through the rooms and ministries in the capitals, and telephone lines between Brussels and Berlin ran hot until everyone was mostly happy in the end.

Since Council meetings usually include press conferences after the meeting and ministers give statements at so-called doorsteps, Frans Timmermans, Robert Habeck and Steffi Lemke appeared before the press that night. The journalists had held out, some had ordered pizza or had waited at home in front of the live broadcast until something stirred.

And all this just to give you, dear readers, the most important news from these nights of negotiations first thing in the morning, when Europe.Table flutters into your mailbox. Stay loyal to us and we’ll continue our night shifts for you.

What exactly is LULUCF, CBAM, CSAM, KARL and OLAF? The first thing everyone who deals with the European Union (EU) professionally needs to learn is the overwhelming flood of names and abbreviations. The Commission (COM) seems to take a real delight in inventing names and creating abbreviations for its acts, programs and institutions.

Actually, names help us to orient ourselves in the world. But the names of the EU are usually only understood by experts. They tend to exclude or scare people away rather than win them over to the issues and policies behind them.

The Green Deal is an exception. The catchy name says it all. “I can imagine something when hearing it”, explains Manfred Gotta. “The name also lends itself to headlines in the media. It settles better than an abbreviation.” Names are Gotta’s profession. For more than 40 years, he has been very successful in developing names for products and companies, creating value. With his creations Xetra, Megapearls or Twingo, almost everyone in Europe knows what is meant.

In contrast, Gotta says, abbreviations only work if people associate something emotional with them. For example, when it comes to the highly emotional topic of cars, people can remember that ABS is a braking system. But what are people supposed to do with LULUCF (Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry)?

The abbreviation AI for the hotly debated topic of artificial intelligence, on the other hand, no longer needs an explanation. Even people who can’t explain the abbreviation GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformers) talk about ChatGPT.

CSAM, for example, is different. With this, the EU wants to take action against “Child Sexual Abuse Materials (CSAM)” in order to better protect children on the Internet. What could be more emotional? Yet the acronym doesn’t work. Others call the legislative project chat control – and suddenly everyone in Germany knows what it’s all about – and recall the debate.

CSAM is therefore also an example of the fact that the Commission already takes sides or sets a direction with the naming, if it is not absolutely neutral. CSAM also shows that abbreviations do not work in all languages. And finally, the abbreviation also shows how easy it is to confuse legal acts, for example when one is called CSAM and the other CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism).

Yet CBAM, with the BAM at the end, at least has a powerful sound. “Bam, that’s what my grandchild always says when something falls down”, Gotta recalls. “It makes me think of a conflict situation rather than regulation to reduce emissions.” Besides the Green Deal, all the examples the editors sent to the expert fail.

Fit for 55? “What’s that supposed to be”, Gotta asks. “A gym or a gum?” He thinks a climate change package with a goal of reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030 “deserves a real name”. A name that can’t be misunderstood or even offensive, and that doesn’t bypass people.

He can’t just pull a name like that out of thin air. Thorough research is needed beforehand. “Professional branding”, Gotta says, “is composed of rational and non-rational values that are identically represented by the name nationally, European, or internationally.”

REACH, for example, sounds like a name, but it is an acronym (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals). This makes no sense as a name or as an abbreviation for a European regulation, since it does not evoke any association with a chemicals regulation in English and is understood differently in other countries.

Even the abbreviation KARL for the revision of the directive on the treatment of urban wastewater can be remembered by German native speakers. “But it’s superfluous”, says Gotta. For the general public, it is not interesting anyway, and if it is, the EU Wastewater Directive is still clearer. Especially since the directive is not called KARL but UWTTD in English. The European Anti-Fraud Office is called OLAF. This only makes sense in French: Office Européen De Lutte Antifraude.

But what makes a good name – apart from the fact that it has to work internationally? Why do names like Chiquita or Twingo work? “None of the names communicates through its phonetics, associations or content elements which area it comes from or what benefits it promises”, explains Gotta. Nevertheless, the names unmistakably represent a very specific product everywhere. “You have to create uniqueness“, explains Gotta.

The important thing, he says, is to cast a name first. “We learn names every day from childhood”, says the copywriter. And like a business card, he says, you can then translate its function in many languages under the name. “Then people all over Europe associate the same thing with that name.” For example, Tabasco is a hot chili sauce everywhere.

Finally, “Only the laws that are really important to people should be given a name”, Gotta advises the Commission. “Sounding names are especially easy to remember.” On that, a Dujardin.

Aug. 8, 2023; 9 a.m.-3:45 p.m., online

BMI, Seminar Sustainable public procurement

The Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (BMI) offers training for authorities and institutions at federal, state and local level on the basics, legal framework and implementation of sustainable procurement. INFO & REGISTRATION

When I started writing about EU politics for Table.Media, I was surprised. In 2022, when photos of all-male groups in decision-making positions had long since reaped huge shitstorms, I attended events and panel discussions where only men spoke on stage. The only distinguishing feature between them was the various color variations of their ties.

“Well, with these topics, I guess that’s the way it is…”, I thought. Raw materials, circular economy – there just aren’t that many women in industry to report on. But why does this seem obvious to me? In a world that is undergoing rapid change in all areas of life, the clocks in the spectrum of political and economic contexts seem to tick much more slowly.

Following this impression, I asked my colleagues. The majority of our editorial team members actually see the perspectives of men more often considered in Europe.Table than those of women.

A feeling that also corresponds to the balance: Two-thirds of the people portrayed in Europe.Table so far are male. This section presents people whose function and work are – or should be – of interest to our readers. Certainly, there could be more women among them.

This picture reflects a global trend: Women are significantly less present in the media than men. The Global Media Monitoring Project regularly analyzes news from print, radio, television, the Internet and Twitter under the title “Who Makes the News?” The most recent evaluation of news coverage in Europe from 2020 showed that only 28 percent of the sources cited in traditional and digital media were women. Women were most likely to serve as sources in articles about gender-related topics. Women were least likely to be quoted in reports about politics and governments (22 percent). They were most likely to serve the purpose of providing eyewitness accounts or public opinion, rather than appearing as experts.

In the EU cosmos, the focus of our reporting, a lot has ostensibly changed in recent years: Ursula von der Leyen is the first woman to hold the most powerful EU post at the head of the Commission (and thus receives a lot of media attention). For the first time, the Commission has equal numbers of women and men, including for the first time a female Equal Opportunities Commissioner, Helena Dalli of Malta. The EU Parliament is also headed for the first time by a woman, Roberta Metsola.

But the figures behind the radiance of these publicly visible figures speak a different language: men continue to dominate leadership positions in the EU institutions. In the EU Parliament, the gender ratio is 60 to 40 percent.

In the largest companies in the EU, only one-third of management positions are held by women. Most executive boards now have at least one woman on them. But only under ten percent of CEOs are women. In a way, it seems logical that this is reflected in the media.

So what can we do to make our reporting more balanced? Of course, we have no influence on which person holds a particular office. EU Commissioners, MEPs, heads of state and government – they are all elected to their positions, whose role should also be legitimized from a journalistic perspective by their qualifications and not by their gender.

In view of the parity claim, the question arises as to whether the still predominant majority of male-occupied positions is also based on a traditional assessment of aptitude that assigns men per se greater competence in certain subject areas. This also seems to promote reporting that is different for men and women.

Journalists should therefore also ask themselves whether we report differently on female protagonists than on male ones. When female politicians make it into the headlines, it is often accompanied by sexism and stereotypes. Former Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin, for example, has become interesting to the media primarily because of her dance video. At a meeting Marin had with then-New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern last year, a journalist asked the two female politicians, “Are you just meeting because you’re similar in age and therefore have common interests?”

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) recently released a toolkit to raise awareness of just such issues and promote more gender-equitable political coverage. “The news media still has a long way to go to represent cisgender and transgender women in leadership in an appropriate way, and every single effort counts“, it says.

Journalists and editors also have the opportunity to ensure more balance when selecting experts for quotes, portraits and interviews. There are tools for this: LMU Munich, for example, uses the FemConsult database to place female scientists in leadership positions. The AcademiaNet database of the Robert Bosch Stiftung and Spektrum der Wissenschaft lists thousands of top female researchers from various disciplines.

Gender parity has not only a numerical dimension, as the European Institute for Gender Equality writes, but also a substantial one: It refers to the equal contribution of women and men to every dimension of life, private and public.

“There is a gender angle to every story”, every story has a gender dimension, writes the Global Media Monitoring Project. Even the big, current issues: Climate policy, raw materials supply, due diligence, digitalization. The UN Development Program reports, for example, that “the effects of climate change perpetuate and reinforce structural inequalities, such as those between women and men”.

Female and male journalists decide whose perspectives they present in their articles, which topics and people they help onto the public stage. This “gatekeeper” function and journalistic quality standards also call for a balance of male, female, more diverse perspectives. This includes a responsibility at the individual level. For all writers. And for me, too.

There is no one who has followed the events in the directly elected representation of the EU citizens from the beginning until today as closely as Bernd Posselt. He was there when the first directly elected EU Parliament met in Strasbourg on July 17, 1979. At that time he was 23 years old and assistant to Otto von Habsburg, the long-time MEP for the CSU and son of the last Austro-Hungarian emperor. Posselt himself moved into the European Parliament for the CSU in 1994 and was involved in the Foreign Affairs Committee and security policy issues.

He was a member of the house for 20 years. Since he missed re-election in 2014, he is the first on the CSU’s list of successors. Presumably, the 68-year-old, who was born in Pforzheim and is a trained journalist, will also end up in seventh place again on the CSU’s European list in the fall. Presumably, this will again be the first place to move up.

Posselt had to give up his access pass as a member of the European Parliament (MEP) almost ten years ago. But he has continued to be present ever since – especially during the Strasbourg session weeks. As an ex-MEP, he continues to have access to the House. But unlike other ex-MEPs, he has not used this access to influence his former colleagues as a lobbyist, but rather for political work. Posselt advises EPP parliamentary group leader Manfred Weber on foreign policy, writes books and monitors European politics. Since 1998, he has been head of the non-partisan Paneuropa Union, whose origins date back to the 1920s.

Somehow Posselt has not stopped being a deputy. He is present in Strasbourg, more present than many a deputy who has received a mandate from the voters. He is not allowed to vote and does not sit down in the plenum. But he is present and, apart from illness, has probably not missed a single sitting in Strasbourg since July 1979. Back then, when Posselt lost his seat in Parliament and still went to Strasbourg, articles appeared about it that bore mocking features.

“I’ve read all that”, Posselt reports. But he is sticking to his mission because – in his case, the expression is probably apt – he is inspired by the European idea like hardly any other politician. He joined the CSU when he was 20 years old. The occasion was Franz-Josef Strauß’s speech entitled “Europe can wait no longer”. Posselt says: “Millions of people are volunteering for Europe, why shouldn’t I do the same?”

Posselt was an assistant, then he became a Member of Parliament, meanwhile his role is best described as chronicler of the European Parliament at its headquarters in Strasbourg. There is no one who can tell more knowledgeably about its history. He has Louise Weiss’ speech at the ready, which the politician, journalist and feminist gave at the first session when she was a senior president: “She demanded that we don’t just need European tractor seats, but European people.”

Posselt’s parents came from the Sudetenland and Styria. He took an early interest in Eastern and Central Europe and can be proud of the fact that Putin banned him from entering Russia back in 2015 because of his commitment to human rights.

He is an expert on the architecture and building history of the Parliament. So he can tell about how at the Brussels seat of the Parliament the committees met partly in rented rooms. He vividly describes the symbolism that the legendary international office “architecturestudio” perpetuated in the Strasbourg Parliament building.

The building, which was occupied in 1999 after the election and cost €275 million at the time, stands very deliberately on the spot where the Alsatian Ill meets the canal that connects the Marne with the Rhine. “Three seas are accessible by water from here”, Posselt knows. The glass stands for the transparency of European democracy, he says. The plenary hall is designed like an amphitheater. At several points, visitors have a view of Strasbourg Cathedral.

Posselt also tells of May 1, 2004 and the first EU enlargement to the east. At that time, former Solidarność leader and later president of Poland, Lech Wałęsa, came to Strasbourg for the ceremony. “A pole for the Polish flag was erected at the main entrance to Parliament, made at the former Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk.” Visitors to the Parliament to this day will find the symbol of the formerly banned trade union, whose resistance ushered in the collapse of communism, on the pole.

Posselt is happy to share his knowledge. Although he is one of the few people who do not use a cell phone to this day, he is surprisingly easy to reach. Why he doesn’t have a cell phone? “I want to work creatively, so it would just get in the way.”

Europe is more than the EU. Much more. For us, Europe is also an attitude towards life. And how could we express that more beautifully and emotionally than with music? That’s why members of the Europe.Table editorial team have put together a playlist to mark our 500th issue, with our soundtrack for Europe.

We begin, naturally, with the “Ode to Joy“. Here we have chosen a recording of the London Symphony Orchestra. It is a pity that the British currently have little reason for joy. A colleague even confessed that occasionally tears come to their eyes when they hear the European anthem – but they will remain anonymous, of course.

Then we selected some of the tracks on our playlist by name, just as Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton did for the Raw Materials Act, for example. Breton is apparently convinced that he can communicate European laws better with musical accompaniment. He has already created playlists for various pieces of legislation. This inspired Leonie Düngefeld to select songs with the following words in the title:

Spain, which currently holds the Presidency, also created a playlist at the beginning of its term that we think is worth listening to.

We selected the remaining titles according to personal criteria. The first thing Clara Baldus thought of when she thought of Europe and music was the Eurovision Song Contest. That’s how Loreen with Euphoria ends up on our playlist.

Lukas Scheid likes to travel through Europe and through music he gets different ideas about his travel destinations. Thus, he had to listen to Vajze e bukur nga kurbeti by Bledar Alushaj on repeat while hitchhiking through Albania in a car. Since Albania is a candidate country, the song may serve as a musical sample.

Northern Macedonia is also applying. While Stakleni Noze by Funk Shui was playing, Lukas Scheid sat with young Macedonians over a beer in Mavrovo National Park. They played each other their favorite songs in the national language. Norway, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Sweden have also left their musical mark on his personal playlist. Europe Is Lost by Kae Tempest is the rap he listened to when he lived in the UK during the Brexit.

The background of Norwegian Erlend Øye, who founded the band Kings of Convenience in his native Bergen before starting his second band, Whitest Boy Alive, in Berlin, is downright pan-European. He has since emigrated to Sicily, where he focuses on his solo career, making guitar pop with the Sicilians of La Comitiva. This song La Prima Estate is about the freedom of the first summer after the Maturità, the Italian high school diploma. A recommendation from Leonard Schulz.

When he lived in Istanbul, he often heard musicians playing rembetiko, the “Greek blues.” The compilation Songs of Smyrna (today’s Izmir), with songs like Baxe Tsifliki, remind Leonard Schulz how closely the countries are linked culturally. And he often heard the brass band Fanfare Ciocărlia from Romania – represented here by Iag Bari – during the Balkan music boom in Berlin in the 00s.

When Markus Grabitz thinks of Europe musically, the song Göttingen by the French chansonnière Barbara comes to mind. It was written after a concert she gave in the early 1960s in the city, which had been unknown to her until then, and during which she came into contact with the Germans. It later became the anthem of reconciliation between the former hereditary enemies. She sings, “Let this time never return, and never more hate destroy the world, there are people I love living in Göttingen, in Göttingen…” Chancellor Gerhard Schröder incorporated a passage of the song’s lyrics into his speech on the 40th anniversary of the Élysée Treaties and received much applause for it. No one before or after Barbara has ever pronounced Göttingen so charmingly.

In Putain, Flemish rocker and singer-songwriter Arno Hintjens sings as a refrain: “Putain, putain, c’est vachement bien, nous sommes quand même tous des Européens.” In English, that means something along the lines of: “C-word, c-word, it’s true, we’re all Europeans despite everything.” He later rewrote the 2003 song to protest the Brexit that had been decided but not yet consummated, since then it has also had the verses: “Bye-bye Brexit, bye-bye Brexit, We’re still gonna eat fish & chips all.”

For Corinna Visser, freedom and borderless travel are among Europe’s most important achievements and strengths. She has experienced in other parts of the world what borders can do. That’s why, towards the end of the Europe.Table playlist, it gets cheesy again with Wind of Change by the Scorpions, then a bit weird with Brennerautobahn by Roy Bianco & Die Abbruzanti Boys and finally culinary with Carbonara by Spliff.

Then a look at our neighbors: The Spanish are currently very keen on the rapper Quevedo with Columbia. The French like C’est carré le S by Naps. Italy listens to Alfa with bellissimissima <3. Finally: Freedom by George Michael. Have a great time listening. The Editors