It’s finally happening! The 28th UN Climate Change Conference in Dubai kicks off today, Thursday. Each day from today, we will report on key developments, provide background information and explain the details of the COP process. Bernhard Pötter, Alexandra Endres and Lukas Scheid are on site and will report from Dubai for the next two weeks (plus x).

Numerous important issues will occupy us over the next 14 days: Will the global community be able to reach a good compromise at the Global Stocktake, which will determine climate policy in the coming years? What progress will the countries achieve on climate financing? Will COP President Al Jaber bring about an “Only Nixon Could Go To China” moment and surprise us with breakthroughs? How will the debates surrounding the Gaza war affect the conference and the climate movement?

In today’s interview, German climate activist Luisa Neubauer speaks about the dangers of climate resignation, what she expects from German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and why the Friday for Future dispute over the proper stance on the Gaza war is unlikely to be a factor at the COP. Bernhard Pötter analyzes the positions of various country factions at the Global Stocktake on progress in climate action. Once again, it is clear that the room for compromise is limited.

The interview was conducted in German.

Ms. Neubauer, could you imagine Greta Thunberg appearing again at the next Fridays for Future climate strike in Germany?

The question does not currently arise.

What would have to happen?

Anyone in Germany can invite Greta Thunberg, it’s not up to me, and that’s a good thing.

Differing positions on the Gaza war have resulted in friction between the German and international Fridays for Future groups. Will there be reconciliation talks at COP28?

I am cautious with my expectations of the climate conference, both politically and interpersonally. The conference does not have the reputation of being the most salutary place for exhausted activists. However, we will, of course, talk a lot about what happened and how we can reunite.

Will there be joint campaigns by the young protest movement?

Of course, there will be campaigns and protests, but how exactly and in what form, I don’t know yet. But it’s not as if we in Germany, in particular, have problems with what is being said internationally. From an international perspective, Germany’s stance is a particular problem.

Are the German Fridays internationally isolated?

Not really, our partners from Austria, Switzerland, France and others are also close to our position. The normative mean of the international climate movement is somewhere else when it comes to this issue.

What happened in the past six weeks? Has a rift appeared that has been there for some time?

Since I became involved in the international movement, there has been a mistrust of white European climate activists: How serious are we about climate justice? I can understand that, in principle. False promises have been made for too long by generations before us. And that has now been proven true again in the eyes of some: That when things get tough, we don’t stand by our partners and friends. But even outside the climate movement, we are seeing how uncomprehending and disappointed people are looking at the German position on Israel and Gaza. Even among international organizations: In the past, people didn’t want to work for USAid, now we hear of a similar attitude towards German organizations.

What is the reason for this mistrust?

Many feel abandoned by how Germany is navigating the crisis. Many see the support of civil society in Gaza as a secondary concern. The climate movement is a small projection screen for this. But there is a second factor behind this mistrust: We Fridays in Germany, particularly, are pragmatically socialized in the activist trade because we realized early on that we can make a difference and change things. I also saw this with activists who prevented a dam in Cambodia. They went to prison for it and were awarded the Alternative Nobel Prize – but they prevented the dam. They are totally oriented towards realpolitik. Suppose your own system gives you the impression that you can’t win no matter what and even small advances seem hopeless. In that case, your own radicalism becomes more identity-forming than the actual organizing.

But hasn’t the international climate justice movement long since embraced the official positions of the Global South vis-à-vis the Global North? When it says “system change, not climate change” and is associated with a fundamental rejection of policies from the capitalist Global North?

That was not the case for us. We are also calling for “system change” in Germany, if by “system” we mean exploitative conditions, for example. We are continuing to work on breaking up these North-South fronts by stating that we are telling a new story of young people who do not allow themselves to be divided by a clearly exploitative past.

But isn’t that what’s happening right now – that you’re dividing yourselves?

The risk is there.

What needs to happen for this rift to stop widening?

I don’t have a simple solution for this. We certainly need to raise awareness of the historical responsibility that not only rests on Germany’s shoulders, but is a global responsibility. This also means recognizing anti-Semitism and acknowledging Israel’s right to exist. But we are also called upon to find a genuine and appropriate political approach to the situation in Gaza. I can understand why Germany is accused of not taking a clear enough stand to put an end to the dying in Gaza. It would be an important step if we, as Germany, could manage to work towards a lasting ceasefire to protect civilians.

Is the climate movement in Dubai so preoccupied with itself that it is no longer a driving force?

This attitude does surprise me: Nobody has been interested in the international movement for the last three years. Now, you could get the impression that international work is our linchpin. The international climate movement is huge, Fridays for Future is a relatively small part of it. We are very big in Germany, but seldom in other countries. Of course, there will be activists from other countries doing their thing. I don’t think the debate within the Fridays will make such a difference. Only a fraction of Fridays are going to the COP. And we also believe that any reconciliation processes may not have to happen exclusively in the two weeks when we have the chance to influence international climate democracy.

You say the Fridays are not so relevant that their problems will influence the conference?

The sentiment is relevant, but it’s not a Fridays issue, it’s a global issue. It has less to do with the climate movement than with global civil society. It is currently in a different place than the German raison d’état. I don’t want to downplay what we are doing, but international dynamics are more powerful than we are. However, there is one difference: We, as the German Fridays for Future movement, have always been able to set a lot in motion at the COPs: We know our way around, we have considerable capacities, we know the craft, and we can apply it well. A year ago at the COP in Egypt, we were able to accompany large parts of the protests. We were able to open up these spaces well, partly because we are privileged as people with a German passport. That will be more difficult now. We have been put in a situation where cooperation is always associated with explanatory and mediation work. That contradicts the rush-hour logic of a climate conference.

How important are the conferences? Many are skeptical.

There are huge deficits, but there is currently no alternative. There is a media reflex to exaggerate the COP as the singular highlight of the year. But the fifty weeks between the COPs are just as important as the two weeks at the COP. And what has not been achieved beforehand can’t be ironed out there. But we need places where we can come together as a civil society.

You say that Fridays have been talked down in Germany. Where do you see that?

For the past two or three years, there has been significant public surprise that it is not so easy to do climate activism in Germany. Yes, of course, we lose sometimes. Because we are in such a huge crisis for which no solution has been found over the last 50 years. We can’t just turn it around in a few years and surf away on a green tide. We started out as FFF in an incredible climate hype, which was a total exception even back then. But we wouldn’t need a climate movement if we didn’t have hard times.

Why has the mood in Germany turned so much against climate action in the last year?

There are many explanations for this. One reason is certainly that some chancellor thought he could outsource the climate problem to one party and even just one ministry. And if half of Germany then lashes out at this minister, then that is not the chancellor’s problem. But if you can’t make climate demonstratively a top priority, then the whole thing will fall apart. He would have to enforce a minimum ecological discipline in the cabinet so we don’t negotiate whether we meet the climate targets. And if you cannot propose a better plan for the current situation, then you have no right to make proposals. If you don’t do all this, as Chancellor Scholz has failed to do, we end up at a point where the existential crisis of our time is turned into a private problem for [German Economy Minister] Robert Habeck. And confidence and trust in the German government and democracy are lost in the process and resignation takes hold of this society.

How do you fight this resignation?

Most people mean well. And do their best. That often looks very different, and that’s okay. If resignation is the beginning of the end, and politically speaking, the greatest threat to climate and democracy, because it is those who resign themselves who will allow a shift to the right and a climate crisis – then the fight against my own resignation is a very trivial part of my daily activism. And in the next step, all doors are open if we just look closely.

Click here for all previously published articles on COP28.

Delegations will face tough negotiations on the key decision of COP28 on the Global Stocktake (GST). After all, each country and group’s ideas on what consequences should be drawn from the first global stocktake on climate action differ significantly. In some cases, they even oppose each other directly. This is revealed by an overview of the proposals that 23 UN states and country groups and around 50 international organizations have submitted to the UNFCCC Climate Change Secretariat. Table.Media has analyzed the documents.

For the first time since the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015, the Global Stocktake reviews the achievements in climate action made since and how to move forward. In September, the findings from the “technical dialog” were summarized. The UNFCCC Secretariat then summed up the results from its perspective. Now, a document must be presented at COP28, which will form the basis for a decision.

The papers to date have shown great consensus when it comes to identifying gaps in climate action to date. But there is also a lot of agreement on other issues:

On other issues, ideas and perspectives differ widely. This is revealed by an overview of the key players and their priorities.

The position of the G77 and China is presented by the current chair, Cuba. It is largely in line with the well-known positions of this large alliance of developing countries in the UN (now around 130 states). Its sub-groups such as LDCs or Basic as well as large countries such as China or India also echo many of these positions:

The group around Brazil, South Africa, India and China (BASIC) sees itself as the leading group of the G77/China. And against the backdrop of geopolitical tensions and the expansion of the BRICS group, which also includes Russia, they are much more self-confident. BASIC’s demands are formulated much more sharply than the G77 declaration. To them, the climate crisis is “the biggest test for humanity is the appalling legacy of colonization and imperialism of the last five centuries.”

The African countries attach great importance to the declaration linking the sustainable development of their continent with climate goals. Progress on achieving SDGs must be made and the outcome of the GST must under no circumstances “deepen the under-development of African countries.” The primary goal must be to help the 600 million people in Africa without access to electricity and the 900 million without clean water. They also demand to:

Saudi Arabia finds itself in several roles. As a dominant oil producer, current prices secure significant profits, and as a traditional blocker in negotiations, tactically acting wisely. The country also aims to play a more important global role and take a significant position in the future of a decarbonized economy. The kingdom’s demands include:

Russia traditionally keeps a low profile at the conferences. Especially since the attack on Ukraine, the delegates do not seek the big stage, but are always present in the process. Their demands are shaped by the fact that the Russian economy relies heavily on the export of gas and oil. Therefore:

China is perhaps the most powerful player in climate negotiations. The superpower pursues its own goals, suffers from climate impacts, and aggressively promotes renewable expansion domestically. Simultaneously, it depends on the fossil economic model and exports. The country still defines itself as a developing nation to hold together the negotiating group of G77/China. This role is increasingly under pressure, especially in financing matters related to the loss and damage fund. As the current largest carbon emitter, China wants:

The United States traditionally serves as China’s major adversary. Washington combines competition and cooperation with this political and economic rival. For the climate process to work, China and the US must see eye to eye. However, in the demands for the final decision of the COP28, the US government, which faces an election year, outlines its positions:

The European Union likes to see itself as a climate pioneer. The bloc of 27 states has reduced its carbon emissions by about 25 percent since 1990, aims for a 55 percent reduction by 2030 under the “Green Deal,” and targets net-zero emissions by 2050. EU member states are the largest financiers in international climate action and seek strategic alliances with emerging and developing countries. Therefore, the EU’s submission includes:

CAN International, a coalition of more than 1900 environmental and development organizations from 130 countries under the umbrella of the “Climate Action Network,” has been accompanying COPs from the beginning. The experts and lobbyists of these groups are now part of many country delegations. Germany’s climate envoy Jennifer Morgan and the Canadian environment minister Steven Guilbeault used to work here. CAN traditionally provides expertise and represents the voices of poor developing countries and conservation. Specifically, they demand from a statement on the GST:

The Least Developed Countries (LDCs) are often the most severely affected by the climate crisis due to their geographical location, weak institutions, economic structure, and low prosperity. Therefore, their demands are sometimes more extensive. They advocate for various elements in the statement, including:

Click here for all previously published articles on COP28.

Nov. 30, 10 a.m., UN Climate Change Global Innovation Hub, Zone B2

Opening UN Climate Change Global Innovation Hub COP 28 Info

30. November, 12.30 Uhr, Press Conference 2, Zone B6

Press conference Local Governments and Municipal Authorities COP28 Position and expectations for multilevel action and urbanization Info

Nov. 30, 3 p.m., OECD Virtual Pavilion

Discussion Greening global energy grids with AI and connectivity

Artificial intelligence can help achieve the climate targets for 2050. This panel discussion analyzes the relationship between AI, the Internet of Things (IoT) and underlying connectivity infrastructure, and their implications for efficient energy systems. Info

Nov. 30, 4 p.m., Meeting Room 3, Zone B1

Mandated Event Understanding the Effects of Response Measures to Support Just Transition and Economic Diversification: Case Studies Info

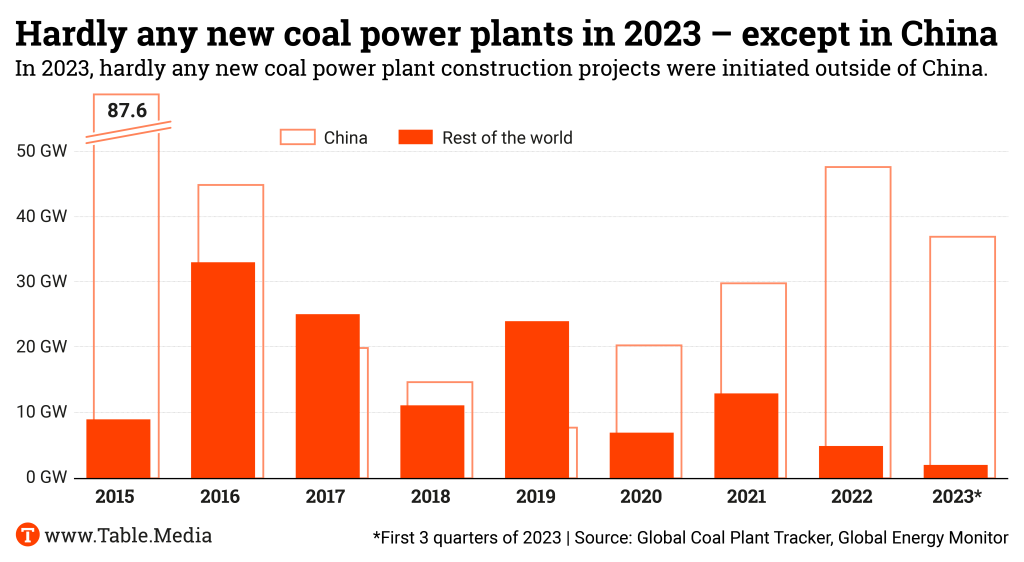

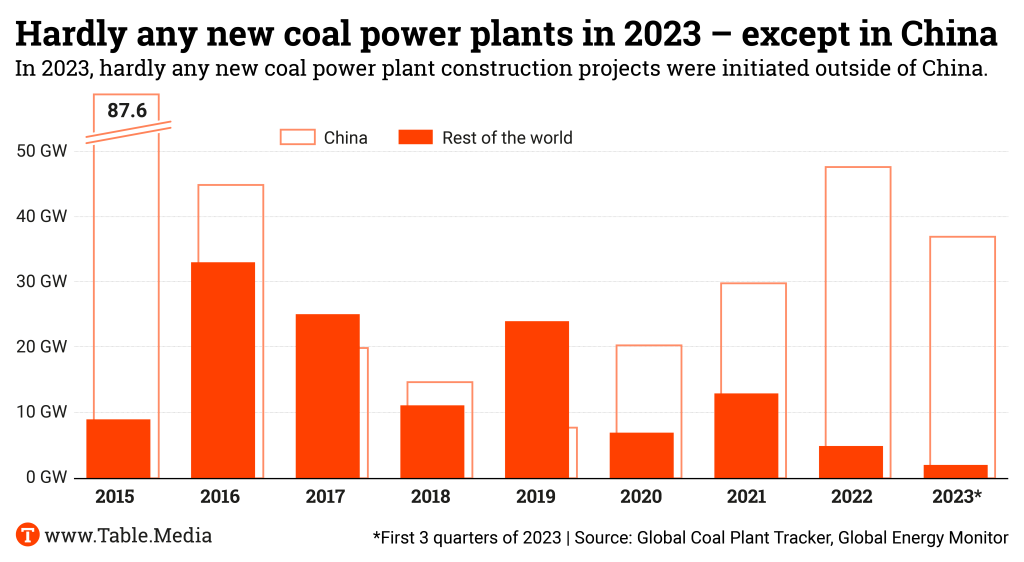

In the first nine months of 2023, there was hardly any new construction of coal-fired power plants worldwide – except in China, where the construction boom that began in 2022 continued. According to research by the Global Energy Monitor organization, outside of China, construction projects for new coal-fired power plants with a capacity of less than 2 gigawatts were started in only three other countries in the current year. This is well below the average of 16 gigawatts over the last eight years. However, in China, over 37 gigawatts of new coal capacity were started in the last nine months, which is well above the average of recent years.

Outside of China, there are currently 67 gigawatts under construction, some of which started construction before 2023. However, overall, fewer new coal-fired power plants are being permitted or planned outside of China, as long-term data from the Global Energy Monitor shows. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts a declining coal consumption for the coming years. nib

Sultan Al Jaber, president of COP28, denies that the United Arab Emirates wanted to use the climate conference to negotiate oil and gas deals. On Monday, the BBC and the Centre for Climate Reporting reported that Al Jaber had prepared for negotiations on fossil fuels with at least 15 countries. The reports cite leaked documents. They reportedly show, for example, preparations for talks with China on LNG shipments from Mozambique, Canada and Australia. The leaked documents refer to preparatory meetings with ministers from various countries.

Al Jaber called these reports “false, not true, incorrect and not accurate” and an attempt to undermine his presidency of the COP. Al Jaber’s COP presidency has been repeatedly criticized in the run-up to the conference. He holds several high-ranking positions in government and business, including Chairman of the Board of the state-owned oil giant Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC). Al Jaber sees himself as a mediator between the climate movement and the fossil fuel industry. We also discuss this controversy in today’s profile of the COP President. rtr/kul

From January to the beginning of November, significantly less Amazon rainforest was destroyed than in the first eleven months of the previous year. Forest destruction has decreased by 56 percent. The rate of deforestation fell in Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. These are the findings of an analysis by the forest monitoring program MAAP of the non-profit organization Amazon Conservation.

The Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, helps curb global warming as its trees absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide. The decline coincides with a change of government towards left-leaning presidents in Brazil and Colombia, who have stepped up forest conservation efforts since last year. Analysts attribute the decline largely to the stricter enforcement of environmental laws in Brazil, where a large part of the Amazon forest is located. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office on January 1. His predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, had advocated rainforest deforestation for mining, livestock farming and other purposes.

Experts say that success in curbing deforestation will give Amazon countries more leverage to push for conservation funding at COP28. At the climate conference 2021, more than 100 countries pledged to end global deforestation by 2030. So far, global data has not indicated this goal is within reach.

According to MAAP, 9,117 square kilometers less forest were destroyed in the Amazon region between January 1 and November 8 – an area the size of Puerto Rico. Carlos Nobre, a geoscientist at the University of São Paulo and co-founder of the Science Panel for the Amazon Research Collective, called the new deforestation data “wonderful news.” Deforestation thus fell to its lowest level since 2019, the first year accurate satellite data is available. rtr/nib/kul

Germany is one of the regions with the highest loss of water worldwide due to global warming. The annual losses amount to 2.5 cubic kilometers. By comparison, Lake Constance contains around 48 cubic kilometers of water. The new monitoring report on the “German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change” (DAS) shows that the consequences are far-reaching. For example, the past few years have been marked by severe regional droughts. In many places, groundwater levels fell to record lows. This resulted in a 15 to 20 percent drop in wheat and silage maize harvests in some years. Forests, especially spruce stands, suffered from the drought stress and died in some areas. The drought caused major forest fires, particularly in the northeastern federal states. In addition, heatwaves with temperatures of over 40 degrees Celsius north of Hamburg occurred for the first time, as well as far-reaching changes in the ecosystems in the sea and on land.

Federal Environment Minister Steffi Lemke spoke of the “devastating consequences of the climate crisis,” which “affect people’s health, ecosystems and the economy.” Lemke went on to say that local authorities are increasingly aware of their “crucial role” in preventive measures.

The Federal Government supports them under the Climate Change Act and the associated strategy. The President of the Federal Environment Agency, Dirk Messner, added with an optimistic assessment: “In addition to the damage, the report also shows that adaptations are working on the ground. The number of heat-related deaths has been reduced through targeted information campaigns.” The federal and state governments are also working on the sustainable management of water resources and soils. In the future, the federal government will submit a monitoring report on the DAS every four years, as required by the climate adaptation law. av

With her ambitious Bridgetown Agenda to reform the international financial architecture, Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley has become a powerful advocate for climate justice. But she is not the only world leader rising to meet the profound challenges we face today. A new generation of leaders from the Global South are making their voices heard.

Kenyan President William Ruto, for example, is forging a new path toward climate-positive growth in Africa: by taking advantage of its abundant natural resources and realizing its green-manufacturing potential, the continent could supply the developed world with goods and services to accelerate the clean-energy transition. In Latin America, Colombian President Gustavo Petro has called for a new Marshall Plan to finance global climate action. And Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, now in his third non-consecutive term as Brazil’s president, aims to tackle hunger, poverty, and inequality, promote sustainable development, and reform outdated global governance arrangements during his country’s G20 presidency in 2024.

After a decade of protectionism and fragmentation, these initiatives seek to build a global consensus around enacting sorely needed reforms. The post-COVID-19 world is currently experiencing what the G20 has called “cascading crises,” including a dramatic surge in energy and food prices, unmanageable debt burdens in the world’s poorest countries, and a record number of climate disasters. Developing countries need at least 1 trillion US dollars annually to make significant progress on the climate transition and to achieve their development goals. But the costs of inaction are even greater.

Our collective future hinges on a dramatic increase in funding, and the place to start is a levy on windfall revenues from fossil fuels. The global oil and gas industry’s revenues were around 4 trillion in 2022, according to Fatih Birol, the Executive Director of the International Energy Agency – an astonishing 2.5 trillion US dollars more than the average in recent years.

Where has this money come from? The short answer is consumers. Some of the world’s richest companies are raking in bumper profits from a cost-of-living crisis – largely fueled by high energy prices – that has disproportionately affected the poor and vulnerable. The largest beneficiaries of this effective tax on the global economy have been petrostates, whose total export revenues, when complemented by the export earnings of countries like Canada, Australia, Iraq, and Iran, totaled almost 1 trillion US dollars in 2022.

The biggest of these countries, whose per capita incomes are among the highest in the world, are well able to pay a voluntary levy on their exceptionally high hydrocarbon-export revenues into a global fund for sustainable development. A 3 percent tax on the 2022 export earnings of the United Arab Emirates (119 billion US dollars), Qatar (116 billion US dollars), Kuwait (98 billion US dollars), Norway (around 174 billion US dollars), and Saudi Arabia (311 billion US dollars) would raise roughly 25 billion US dollars in total – a sum not that much larger than what the Saudis alone have recently spent on soccer, golf, Formula One racing, and other sports deals.

It is fortuitous that this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) will be held in one of these countries, the UAE. Outlining his plan of action in July, COP28 president-designate Sultan Al Jaber named “fixing climate finance” as one of its four pillars, arguing that “all forms of finance must be more available, more accessible, and more affordable.” Similarly, he has called on donor countries with overdue pledges to “show me the money.”

But as president-designate, the UAE has the responsibility to take the lead. The best way to kickstart COP28 would be for Al Jaber – who is also the managing director and group CEO of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company – to announce that his country will contribute 3 billion US dollars of its windfall earnings to a global finance facility and that it will seek to persuade its wealthy Gulf neighbors to do likewise. More than half of the contributions could go to the loss and damage fund, which was agreed at COP27 but still has gained little initial funding, with the rest used as capital and grant funding for new facilities for climate mitigation and adaptation.

And the international community must use this levy to kickstart a wider financing program for the developing world, based on the principle that rich, historically large polluters with the capacity to pay should contribute more to help poorer countries adapt to global warming. Not only should aid budgets be raised, but the International Development Association, the World Bank’s financing facility for the poorest countries, must also receive a generous replenishment next year.

Providing 90 billion US dollars in concessional finance for low-income countries is at the heart of the proposals from the economist N.K. Singh and former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers in their two volumes of reports to the G20, the first proposed ahead of the recent G20 summit in New Delhi. As they argue, the system of multilateral development banks (MDBs) must increase its overall capacity, which means tripling its annual commitments to 300 billion US dollars in non-concessional finance for middle-income countries.

As part of their proposals, which include recapitalization of the World Bank itself, they favor the wider use of guarantees. High-income countries could and should provide such guarantees that will enable MDBs to borrow from capital markets on attractive terms.

Such initiatives, if properly managed, could mobilize private-sector lending, which is essential to meeting our climate objectives. And it is the combination of the levy and the use of guarantees that, if agreed at COP28, could be the platform for achieving 1 trillion US dollars in annual financial flows to developing countries by 2030.

Seventy-five years ago, under the original Marshall Plan, the United States lent 13.3 billion US dollars (169 billion US dollars in today’s money) to Europe for its postwar reconstruction. It was a remarkable act of global leadership that helped secure decades of stable economic growth and international cooperation.

While today’s world and the crises it faces are very different, the scale of the response must be equally ambitious. Countries in the Global South are charting a way forward. Now, their rich counterparts in the Global North must step up and provide the necessary funding. The money is there, but we need the political imagination and will to use it before the next crisis arrives.

Gordon Brown, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, is Special Envoy for Global Education at the United Nations. Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World by Gordon Brown, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Michael Spence, and Reid Lidow was published on September 28, 2023.

In cooperation with Project Syndicate, 2023.

The disapproval was strong, and it came swiftly, just two weeks after the United Arab Emirates (UAE) appointed Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber as COP28 President in early January 2023. In an open letter to UN Secretary-General António Guterres, more than 400 NGOs called for the appointment to be revoked. After all, Al Jaber, the CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC), is all sorts of things – but not a climate activist, they claimed.

As proof, they listed some facts: In the global ranking of the largest oil producers, ADNOC is in 12th place, and the company ranks 14th in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. And the UAE brought more lobbyists from the fossil fuel industry to the last climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh than any other nation.

It has not changed anything. When the Conference of Parties (COP) enters its 28th round today, a corporate CEO will be chairing it for the first time. By a fossil fuel CEO.

The fact that the 50-year-old would one day take on such a prominent role in world politics was not necessarily predetermined. He grew up in Umm al-Qaiwan, the smallest sheikdom in the United Arab Emirates, far away from the politically dominant Dubai and oil-rich Abu Dhabi. He studied chemical engineering and business administration in California and earned his PhD in economics in the UK. In between, in 1998, he joined the state oil company ADNOC, initially as a process and planning engineer in the natural gas division.

He quickly rose through the ranks there, moved to the state investment company Mubadala as a manager, founded Masdar, a renewable energy supplier, and was sent on a world tour by the then-new rulers. Their goal: promote the diversification of their economy and expand the green energy business. After visiting 15 countries on four continents, Al Jaber returned with a plan: Masdar City was to be built near Abu Dhabi Airport, a carbon-neutral city for 50,000 inhabitants, where young people would learn how to shape a sustainable future.

Since then, he has been given further responsibilities. In 2009, the then-UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon appointed him to his Advisory Group on Energy and Climate, in 2010, he became the UAE’s Special Envoy on Climate Change, in 2016, he became Chairman of the Board of ADNOC and in 2020, Minister of Industry. In the meantime, he also took on the position of head of the National Media Council and sits on several supervisory boards.

Al Jaber’s supporters also emphasize his commitment to the energy transition, attendance at previous climate conferences, and various insights and contacts in the business world. Frans Timmermans, for instance, pledged his full support when he was still EU Commissioner for Climate Action. John Kerry, United States Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, called him an “excellent choice”. Kerry sees him as a mediator between the worlds. “If he can’t get this done, if oil and gas won’t show up and do something real here, then the UAE will look really bad, and he knows it,” Kerry said. “They’re going to have to fight a little bit, but if they do, they could be the all-time catalyst,” a player that has flipped the switch at a crucial point.

Al Jaber openly supports the energy transition. “A phasedown of fossil fuels is inevitable, it is essential,” he told Time magazine. “We have to accept that.” At the same time, he explained that the world is not yet ready to abandon oil and gas completely. “We cannot unplug the world from the current energy system before we build a new energy system.”

Statements like these have critics wary. They have yet to see any evidence of a credible turnaround in the Arab oil world – on the contrary. They highlight the 150 billion US dollars that ADNOC alone wants to invest in its expansion. The company plans to increase its daily production from currently just under three million barrels to five million barrels by 2030.

And then there are media investigations. The Guardian reported that emails intended only for the conference organizers also ended up on ADNOC servers. The BBC discovered that UAE negotiators also planned to use the political talks during the COP for new business deals, i.e., the sale of oil and gas. According to Bloomberg, Masdar, which claims to be one of the largest renewable energy companies, only ranks 62nd in the world in terms of installed capacity. In addition, Masdar City will probably not be completed until 2030 at the earliest, and not 2016 as planned. So far, just a third of the planned city has been built.

In the run-up to the climate conference, Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber traveled a lot again, on an international “listening tour,” as it was called. He met Emmanuel Macron, Olaf Scholz, Pope Francis, John Kerry, King Charles and others. At COP28, he must continue this listening and sounding-out approach if he wants to lead the conference to success. So far, he has no experience moderating the interests of almost 200 countries.

His own goals – and those of the Emirates – could become a source of conflict in the process. Doing one thing and not abandoning the other has been the maxim so far: The petrostates intend to establish the renewable business – and further expand the fossil business before possibly scaling it back. Carbon capture and storage (CCS), the capture and underground storage of climate-damaging carbon dioxide, is supposed to help achieve this balancing act. The technology is supposed to legitimize the dirty burning of fossil fuels in the future.

The fact that the expensive, energy-intensive and underdeveloped CCS technology has only made a small contribution to the transformation so far does not seem to faze Al Jaber. He is betting on the future and that global market maturity will be achieved in a few years.

On the other hand, it will probably soon show whether he is actually interested in saving the world from climate change. The world will know more about Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber in two weeks. Marc Winkelmann

It’s finally happening! The 28th UN Climate Change Conference in Dubai kicks off today, Thursday. Each day from today, we will report on key developments, provide background information and explain the details of the COP process. Bernhard Pötter, Alexandra Endres and Lukas Scheid are on site and will report from Dubai for the next two weeks (plus x).

Numerous important issues will occupy us over the next 14 days: Will the global community be able to reach a good compromise at the Global Stocktake, which will determine climate policy in the coming years? What progress will the countries achieve on climate financing? Will COP President Al Jaber bring about an “Only Nixon Could Go To China” moment and surprise us with breakthroughs? How will the debates surrounding the Gaza war affect the conference and the climate movement?

In today’s interview, German climate activist Luisa Neubauer speaks about the dangers of climate resignation, what she expects from German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and why the Friday for Future dispute over the proper stance on the Gaza war is unlikely to be a factor at the COP. Bernhard Pötter analyzes the positions of various country factions at the Global Stocktake on progress in climate action. Once again, it is clear that the room for compromise is limited.

The interview was conducted in German.

Ms. Neubauer, could you imagine Greta Thunberg appearing again at the next Fridays for Future climate strike in Germany?

The question does not currently arise.

What would have to happen?

Anyone in Germany can invite Greta Thunberg, it’s not up to me, and that’s a good thing.

Differing positions on the Gaza war have resulted in friction between the German and international Fridays for Future groups. Will there be reconciliation talks at COP28?

I am cautious with my expectations of the climate conference, both politically and interpersonally. The conference does not have the reputation of being the most salutary place for exhausted activists. However, we will, of course, talk a lot about what happened and how we can reunite.

Will there be joint campaigns by the young protest movement?

Of course, there will be campaigns and protests, but how exactly and in what form, I don’t know yet. But it’s not as if we in Germany, in particular, have problems with what is being said internationally. From an international perspective, Germany’s stance is a particular problem.

Are the German Fridays internationally isolated?

Not really, our partners from Austria, Switzerland, France and others are also close to our position. The normative mean of the international climate movement is somewhere else when it comes to this issue.

What happened in the past six weeks? Has a rift appeared that has been there for some time?

Since I became involved in the international movement, there has been a mistrust of white European climate activists: How serious are we about climate justice? I can understand that, in principle. False promises have been made for too long by generations before us. And that has now been proven true again in the eyes of some: That when things get tough, we don’t stand by our partners and friends. But even outside the climate movement, we are seeing how uncomprehending and disappointed people are looking at the German position on Israel and Gaza. Even among international organizations: In the past, people didn’t want to work for USAid, now we hear of a similar attitude towards German organizations.

What is the reason for this mistrust?

Many feel abandoned by how Germany is navigating the crisis. Many see the support of civil society in Gaza as a secondary concern. The climate movement is a small projection screen for this. But there is a second factor behind this mistrust: We Fridays in Germany, particularly, are pragmatically socialized in the activist trade because we realized early on that we can make a difference and change things. I also saw this with activists who prevented a dam in Cambodia. They went to prison for it and were awarded the Alternative Nobel Prize – but they prevented the dam. They are totally oriented towards realpolitik. Suppose your own system gives you the impression that you can’t win no matter what and even small advances seem hopeless. In that case, your own radicalism becomes more identity-forming than the actual organizing.

But hasn’t the international climate justice movement long since embraced the official positions of the Global South vis-à-vis the Global North? When it says “system change, not climate change” and is associated with a fundamental rejection of policies from the capitalist Global North?

That was not the case for us. We are also calling for “system change” in Germany, if by “system” we mean exploitative conditions, for example. We are continuing to work on breaking up these North-South fronts by stating that we are telling a new story of young people who do not allow themselves to be divided by a clearly exploitative past.

But isn’t that what’s happening right now – that you’re dividing yourselves?

The risk is there.

What needs to happen for this rift to stop widening?

I don’t have a simple solution for this. We certainly need to raise awareness of the historical responsibility that not only rests on Germany’s shoulders, but is a global responsibility. This also means recognizing anti-Semitism and acknowledging Israel’s right to exist. But we are also called upon to find a genuine and appropriate political approach to the situation in Gaza. I can understand why Germany is accused of not taking a clear enough stand to put an end to the dying in Gaza. It would be an important step if we, as Germany, could manage to work towards a lasting ceasefire to protect civilians.

Is the climate movement in Dubai so preoccupied with itself that it is no longer a driving force?

This attitude does surprise me: Nobody has been interested in the international movement for the last three years. Now, you could get the impression that international work is our linchpin. The international climate movement is huge, Fridays for Future is a relatively small part of it. We are very big in Germany, but seldom in other countries. Of course, there will be activists from other countries doing their thing. I don’t think the debate within the Fridays will make such a difference. Only a fraction of Fridays are going to the COP. And we also believe that any reconciliation processes may not have to happen exclusively in the two weeks when we have the chance to influence international climate democracy.

You say the Fridays are not so relevant that their problems will influence the conference?

The sentiment is relevant, but it’s not a Fridays issue, it’s a global issue. It has less to do with the climate movement than with global civil society. It is currently in a different place than the German raison d’état. I don’t want to downplay what we are doing, but international dynamics are more powerful than we are. However, there is one difference: We, as the German Fridays for Future movement, have always been able to set a lot in motion at the COPs: We know our way around, we have considerable capacities, we know the craft, and we can apply it well. A year ago at the COP in Egypt, we were able to accompany large parts of the protests. We were able to open up these spaces well, partly because we are privileged as people with a German passport. That will be more difficult now. We have been put in a situation where cooperation is always associated with explanatory and mediation work. That contradicts the rush-hour logic of a climate conference.

How important are the conferences? Many are skeptical.

There are huge deficits, but there is currently no alternative. There is a media reflex to exaggerate the COP as the singular highlight of the year. But the fifty weeks between the COPs are just as important as the two weeks at the COP. And what has not been achieved beforehand can’t be ironed out there. But we need places where we can come together as a civil society.

You say that Fridays have been talked down in Germany. Where do you see that?

For the past two or three years, there has been significant public surprise that it is not so easy to do climate activism in Germany. Yes, of course, we lose sometimes. Because we are in such a huge crisis for which no solution has been found over the last 50 years. We can’t just turn it around in a few years and surf away on a green tide. We started out as FFF in an incredible climate hype, which was a total exception even back then. But we wouldn’t need a climate movement if we didn’t have hard times.

Why has the mood in Germany turned so much against climate action in the last year?

There are many explanations for this. One reason is certainly that some chancellor thought he could outsource the climate problem to one party and even just one ministry. And if half of Germany then lashes out at this minister, then that is not the chancellor’s problem. But if you can’t make climate demonstratively a top priority, then the whole thing will fall apart. He would have to enforce a minimum ecological discipline in the cabinet so we don’t negotiate whether we meet the climate targets. And if you cannot propose a better plan for the current situation, then you have no right to make proposals. If you don’t do all this, as Chancellor Scholz has failed to do, we end up at a point where the existential crisis of our time is turned into a private problem for [German Economy Minister] Robert Habeck. And confidence and trust in the German government and democracy are lost in the process and resignation takes hold of this society.

How do you fight this resignation?

Most people mean well. And do their best. That often looks very different, and that’s okay. If resignation is the beginning of the end, and politically speaking, the greatest threat to climate and democracy, because it is those who resign themselves who will allow a shift to the right and a climate crisis – then the fight against my own resignation is a very trivial part of my daily activism. And in the next step, all doors are open if we just look closely.

Click here for all previously published articles on COP28.

Delegations will face tough negotiations on the key decision of COP28 on the Global Stocktake (GST). After all, each country and group’s ideas on what consequences should be drawn from the first global stocktake on climate action differ significantly. In some cases, they even oppose each other directly. This is revealed by an overview of the proposals that 23 UN states and country groups and around 50 international organizations have submitted to the UNFCCC Climate Change Secretariat. Table.Media has analyzed the documents.

For the first time since the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015, the Global Stocktake reviews the achievements in climate action made since and how to move forward. In September, the findings from the “technical dialog” were summarized. The UNFCCC Secretariat then summed up the results from its perspective. Now, a document must be presented at COP28, which will form the basis for a decision.

The papers to date have shown great consensus when it comes to identifying gaps in climate action to date. But there is also a lot of agreement on other issues:

On other issues, ideas and perspectives differ widely. This is revealed by an overview of the key players and their priorities.

The position of the G77 and China is presented by the current chair, Cuba. It is largely in line with the well-known positions of this large alliance of developing countries in the UN (now around 130 states). Its sub-groups such as LDCs or Basic as well as large countries such as China or India also echo many of these positions:

The group around Brazil, South Africa, India and China (BASIC) sees itself as the leading group of the G77/China. And against the backdrop of geopolitical tensions and the expansion of the BRICS group, which also includes Russia, they are much more self-confident. BASIC’s demands are formulated much more sharply than the G77 declaration. To them, the climate crisis is “the biggest test for humanity is the appalling legacy of colonization and imperialism of the last five centuries.”

The African countries attach great importance to the declaration linking the sustainable development of their continent with climate goals. Progress on achieving SDGs must be made and the outcome of the GST must under no circumstances “deepen the under-development of African countries.” The primary goal must be to help the 600 million people in Africa without access to electricity and the 900 million without clean water. They also demand to:

Saudi Arabia finds itself in several roles. As a dominant oil producer, current prices secure significant profits, and as a traditional blocker in negotiations, tactically acting wisely. The country also aims to play a more important global role and take a significant position in the future of a decarbonized economy. The kingdom’s demands include:

Russia traditionally keeps a low profile at the conferences. Especially since the attack on Ukraine, the delegates do not seek the big stage, but are always present in the process. Their demands are shaped by the fact that the Russian economy relies heavily on the export of gas and oil. Therefore:

China is perhaps the most powerful player in climate negotiations. The superpower pursues its own goals, suffers from climate impacts, and aggressively promotes renewable expansion domestically. Simultaneously, it depends on the fossil economic model and exports. The country still defines itself as a developing nation to hold together the negotiating group of G77/China. This role is increasingly under pressure, especially in financing matters related to the loss and damage fund. As the current largest carbon emitter, China wants:

The United States traditionally serves as China’s major adversary. Washington combines competition and cooperation with this political and economic rival. For the climate process to work, China and the US must see eye to eye. However, in the demands for the final decision of the COP28, the US government, which faces an election year, outlines its positions:

The European Union likes to see itself as a climate pioneer. The bloc of 27 states has reduced its carbon emissions by about 25 percent since 1990, aims for a 55 percent reduction by 2030 under the “Green Deal,” and targets net-zero emissions by 2050. EU member states are the largest financiers in international climate action and seek strategic alliances with emerging and developing countries. Therefore, the EU’s submission includes:

CAN International, a coalition of more than 1900 environmental and development organizations from 130 countries under the umbrella of the “Climate Action Network,” has been accompanying COPs from the beginning. The experts and lobbyists of these groups are now part of many country delegations. Germany’s climate envoy Jennifer Morgan and the Canadian environment minister Steven Guilbeault used to work here. CAN traditionally provides expertise and represents the voices of poor developing countries and conservation. Specifically, they demand from a statement on the GST:

The Least Developed Countries (LDCs) are often the most severely affected by the climate crisis due to their geographical location, weak institutions, economic structure, and low prosperity. Therefore, their demands are sometimes more extensive. They advocate for various elements in the statement, including:

Click here for all previously published articles on COP28.

Nov. 30, 10 a.m., UN Climate Change Global Innovation Hub, Zone B2

Opening UN Climate Change Global Innovation Hub COP 28 Info

30. November, 12.30 Uhr, Press Conference 2, Zone B6

Press conference Local Governments and Municipal Authorities COP28 Position and expectations for multilevel action and urbanization Info

Nov. 30, 3 p.m., OECD Virtual Pavilion

Discussion Greening global energy grids with AI and connectivity

Artificial intelligence can help achieve the climate targets for 2050. This panel discussion analyzes the relationship between AI, the Internet of Things (IoT) and underlying connectivity infrastructure, and their implications for efficient energy systems. Info

Nov. 30, 4 p.m., Meeting Room 3, Zone B1

Mandated Event Understanding the Effects of Response Measures to Support Just Transition and Economic Diversification: Case Studies Info

In the first nine months of 2023, there was hardly any new construction of coal-fired power plants worldwide – except in China, where the construction boom that began in 2022 continued. According to research by the Global Energy Monitor organization, outside of China, construction projects for new coal-fired power plants with a capacity of less than 2 gigawatts were started in only three other countries in the current year. This is well below the average of 16 gigawatts over the last eight years. However, in China, over 37 gigawatts of new coal capacity were started in the last nine months, which is well above the average of recent years.

Outside of China, there are currently 67 gigawatts under construction, some of which started construction before 2023. However, overall, fewer new coal-fired power plants are being permitted or planned outside of China, as long-term data from the Global Energy Monitor shows. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts a declining coal consumption for the coming years. nib

Sultan Al Jaber, president of COP28, denies that the United Arab Emirates wanted to use the climate conference to negotiate oil and gas deals. On Monday, the BBC and the Centre for Climate Reporting reported that Al Jaber had prepared for negotiations on fossil fuels with at least 15 countries. The reports cite leaked documents. They reportedly show, for example, preparations for talks with China on LNG shipments from Mozambique, Canada and Australia. The leaked documents refer to preparatory meetings with ministers from various countries.

Al Jaber called these reports “false, not true, incorrect and not accurate” and an attempt to undermine his presidency of the COP. Al Jaber’s COP presidency has been repeatedly criticized in the run-up to the conference. He holds several high-ranking positions in government and business, including Chairman of the Board of the state-owned oil giant Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC). Al Jaber sees himself as a mediator between the climate movement and the fossil fuel industry. We also discuss this controversy in today’s profile of the COP President. rtr/kul

From January to the beginning of November, significantly less Amazon rainforest was destroyed than in the first eleven months of the previous year. Forest destruction has decreased by 56 percent. The rate of deforestation fell in Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. These are the findings of an analysis by the forest monitoring program MAAP of the non-profit organization Amazon Conservation.

The Amazon, the world’s largest rainforest, helps curb global warming as its trees absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide. The decline coincides with a change of government towards left-leaning presidents in Brazil and Colombia, who have stepped up forest conservation efforts since last year. Analysts attribute the decline largely to the stricter enforcement of environmental laws in Brazil, where a large part of the Amazon forest is located. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office on January 1. His predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, had advocated rainforest deforestation for mining, livestock farming and other purposes.

Experts say that success in curbing deforestation will give Amazon countries more leverage to push for conservation funding at COP28. At the climate conference 2021, more than 100 countries pledged to end global deforestation by 2030. So far, global data has not indicated this goal is within reach.

According to MAAP, 9,117 square kilometers less forest were destroyed in the Amazon region between January 1 and November 8 – an area the size of Puerto Rico. Carlos Nobre, a geoscientist at the University of São Paulo and co-founder of the Science Panel for the Amazon Research Collective, called the new deforestation data “wonderful news.” Deforestation thus fell to its lowest level since 2019, the first year accurate satellite data is available. rtr/nib/kul

Germany is one of the regions with the highest loss of water worldwide due to global warming. The annual losses amount to 2.5 cubic kilometers. By comparison, Lake Constance contains around 48 cubic kilometers of water. The new monitoring report on the “German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change” (DAS) shows that the consequences are far-reaching. For example, the past few years have been marked by severe regional droughts. In many places, groundwater levels fell to record lows. This resulted in a 15 to 20 percent drop in wheat and silage maize harvests in some years. Forests, especially spruce stands, suffered from the drought stress and died in some areas. The drought caused major forest fires, particularly in the northeastern federal states. In addition, heatwaves with temperatures of over 40 degrees Celsius north of Hamburg occurred for the first time, as well as far-reaching changes in the ecosystems in the sea and on land.

Federal Environment Minister Steffi Lemke spoke of the “devastating consequences of the climate crisis,” which “affect people’s health, ecosystems and the economy.” Lemke went on to say that local authorities are increasingly aware of their “crucial role” in preventive measures.

The Federal Government supports them under the Climate Change Act and the associated strategy. The President of the Federal Environment Agency, Dirk Messner, added with an optimistic assessment: “In addition to the damage, the report also shows that adaptations are working on the ground. The number of heat-related deaths has been reduced through targeted information campaigns.” The federal and state governments are also working on the sustainable management of water resources and soils. In the future, the federal government will submit a monitoring report on the DAS every four years, as required by the climate adaptation law. av

With her ambitious Bridgetown Agenda to reform the international financial architecture, Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley has become a powerful advocate for climate justice. But she is not the only world leader rising to meet the profound challenges we face today. A new generation of leaders from the Global South are making their voices heard.

Kenyan President William Ruto, for example, is forging a new path toward climate-positive growth in Africa: by taking advantage of its abundant natural resources and realizing its green-manufacturing potential, the continent could supply the developed world with goods and services to accelerate the clean-energy transition. In Latin America, Colombian President Gustavo Petro has called for a new Marshall Plan to finance global climate action. And Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, now in his third non-consecutive term as Brazil’s president, aims to tackle hunger, poverty, and inequality, promote sustainable development, and reform outdated global governance arrangements during his country’s G20 presidency in 2024.

After a decade of protectionism and fragmentation, these initiatives seek to build a global consensus around enacting sorely needed reforms. The post-COVID-19 world is currently experiencing what the G20 has called “cascading crises,” including a dramatic surge in energy and food prices, unmanageable debt burdens in the world’s poorest countries, and a record number of climate disasters. Developing countries need at least 1 trillion US dollars annually to make significant progress on the climate transition and to achieve their development goals. But the costs of inaction are even greater.

Our collective future hinges on a dramatic increase in funding, and the place to start is a levy on windfall revenues from fossil fuels. The global oil and gas industry’s revenues were around 4 trillion in 2022, according to Fatih Birol, the Executive Director of the International Energy Agency – an astonishing 2.5 trillion US dollars more than the average in recent years.

Where has this money come from? The short answer is consumers. Some of the world’s richest companies are raking in bumper profits from a cost-of-living crisis – largely fueled by high energy prices – that has disproportionately affected the poor and vulnerable. The largest beneficiaries of this effective tax on the global economy have been petrostates, whose total export revenues, when complemented by the export earnings of countries like Canada, Australia, Iraq, and Iran, totaled almost 1 trillion US dollars in 2022.

The biggest of these countries, whose per capita incomes are among the highest in the world, are well able to pay a voluntary levy on their exceptionally high hydrocarbon-export revenues into a global fund for sustainable development. A 3 percent tax on the 2022 export earnings of the United Arab Emirates (119 billion US dollars), Qatar (116 billion US dollars), Kuwait (98 billion US dollars), Norway (around 174 billion US dollars), and Saudi Arabia (311 billion US dollars) would raise roughly 25 billion US dollars in total – a sum not that much larger than what the Saudis alone have recently spent on soccer, golf, Formula One racing, and other sports deals.

It is fortuitous that this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) will be held in one of these countries, the UAE. Outlining his plan of action in July, COP28 president-designate Sultan Al Jaber named “fixing climate finance” as one of its four pillars, arguing that “all forms of finance must be more available, more accessible, and more affordable.” Similarly, he has called on donor countries with overdue pledges to “show me the money.”

But as president-designate, the UAE has the responsibility to take the lead. The best way to kickstart COP28 would be for Al Jaber – who is also the managing director and group CEO of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company – to announce that his country will contribute 3 billion US dollars of its windfall earnings to a global finance facility and that it will seek to persuade its wealthy Gulf neighbors to do likewise. More than half of the contributions could go to the loss and damage fund, which was agreed at COP27 but still has gained little initial funding, with the rest used as capital and grant funding for new facilities for climate mitigation and adaptation.

And the international community must use this levy to kickstart a wider financing program for the developing world, based on the principle that rich, historically large polluters with the capacity to pay should contribute more to help poorer countries adapt to global warming. Not only should aid budgets be raised, but the International Development Association, the World Bank’s financing facility for the poorest countries, must also receive a generous replenishment next year.

Providing 90 billion US dollars in concessional finance for low-income countries is at the heart of the proposals from the economist N.K. Singh and former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers in their two volumes of reports to the G20, the first proposed ahead of the recent G20 summit in New Delhi. As they argue, the system of multilateral development banks (MDBs) must increase its overall capacity, which means tripling its annual commitments to 300 billion US dollars in non-concessional finance for middle-income countries.

As part of their proposals, which include recapitalization of the World Bank itself, they favor the wider use of guarantees. High-income countries could and should provide such guarantees that will enable MDBs to borrow from capital markets on attractive terms.

Such initiatives, if properly managed, could mobilize private-sector lending, which is essential to meeting our climate objectives. And it is the combination of the levy and the use of guarantees that, if agreed at COP28, could be the platform for achieving 1 trillion US dollars in annual financial flows to developing countries by 2030.

Seventy-five years ago, under the original Marshall Plan, the United States lent 13.3 billion US dollars (169 billion US dollars in today’s money) to Europe for its postwar reconstruction. It was a remarkable act of global leadership that helped secure decades of stable economic growth and international cooperation.

While today’s world and the crises it faces are very different, the scale of the response must be equally ambitious. Countries in the Global South are charting a way forward. Now, their rich counterparts in the Global North must step up and provide the necessary funding. The money is there, but we need the political imagination and will to use it before the next crisis arrives.

Gordon Brown, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, is Special Envoy for Global Education at the United Nations. Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World by Gordon Brown, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Michael Spence, and Reid Lidow was published on September 28, 2023.

In cooperation with Project Syndicate, 2023.

The disapproval was strong, and it came swiftly, just two weeks after the United Arab Emirates (UAE) appointed Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber as COP28 President in early January 2023. In an open letter to UN Secretary-General António Guterres, more than 400 NGOs called for the appointment to be revoked. After all, Al Jaber, the CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC), is all sorts of things – but not a climate activist, they claimed.

As proof, they listed some facts: In the global ranking of the largest oil producers, ADNOC is in 12th place, and the company ranks 14th in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. And the UAE brought more lobbyists from the fossil fuel industry to the last climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh than any other nation.

It has not changed anything. When the Conference of Parties (COP) enters its 28th round today, a corporate CEO will be chairing it for the first time. By a fossil fuel CEO.

The fact that the 50-year-old would one day take on such a prominent role in world politics was not necessarily predetermined. He grew up in Umm al-Qaiwan, the smallest sheikdom in the United Arab Emirates, far away from the politically dominant Dubai and oil-rich Abu Dhabi. He studied chemical engineering and business administration in California and earned his PhD in economics in the UK. In between, in 1998, he joined the state oil company ADNOC, initially as a process and planning engineer in the natural gas division.

He quickly rose through the ranks there, moved to the state investment company Mubadala as a manager, founded Masdar, a renewable energy supplier, and was sent on a world tour by the then-new rulers. Their goal: promote the diversification of their economy and expand the green energy business. After visiting 15 countries on four continents, Al Jaber returned with a plan: Masdar City was to be built near Abu Dhabi Airport, a carbon-neutral city for 50,000 inhabitants, where young people would learn how to shape a sustainable future.

Since then, he has been given further responsibilities. In 2009, the then-UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon appointed him to his Advisory Group on Energy and Climate, in 2010, he became the UAE’s Special Envoy on Climate Change, in 2016, he became Chairman of the Board of ADNOC and in 2020, Minister of Industry. In the meantime, he also took on the position of head of the National Media Council and sits on several supervisory boards.

Al Jaber’s supporters also emphasize his commitment to the energy transition, attendance at previous climate conferences, and various insights and contacts in the business world. Frans Timmermans, for instance, pledged his full support when he was still EU Commissioner for Climate Action. John Kerry, United States Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, called him an “excellent choice”. Kerry sees him as a mediator between the worlds. “If he can’t get this done, if oil and gas won’t show up and do something real here, then the UAE will look really bad, and he knows it,” Kerry said. “They’re going to have to fight a little bit, but if they do, they could be the all-time catalyst,” a player that has flipped the switch at a crucial point.

Al Jaber openly supports the energy transition. “A phasedown of fossil fuels is inevitable, it is essential,” he told Time magazine. “We have to accept that.” At the same time, he explained that the world is not yet ready to abandon oil and gas completely. “We cannot unplug the world from the current energy system before we build a new energy system.”

Statements like these have critics wary. They have yet to see any evidence of a credible turnaround in the Arab oil world – on the contrary. They highlight the 150 billion US dollars that ADNOC alone wants to invest in its expansion. The company plans to increase its daily production from currently just under three million barrels to five million barrels by 2030.

And then there are media investigations. The Guardian reported that emails intended only for the conference organizers also ended up on ADNOC servers. The BBC discovered that UAE negotiators also planned to use the political talks during the COP for new business deals, i.e., the sale of oil and gas. According to Bloomberg, Masdar, which claims to be one of the largest renewable energy companies, only ranks 62nd in the world in terms of installed capacity. In addition, Masdar City will probably not be completed until 2030 at the earliest, and not 2016 as planned. So far, just a third of the planned city has been built.

In the run-up to the climate conference, Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber traveled a lot again, on an international “listening tour,” as it was called. He met Emmanuel Macron, Olaf Scholz, Pope Francis, John Kerry, King Charles and others. At COP28, he must continue this listening and sounding-out approach if he wants to lead the conference to success. So far, he has no experience moderating the interests of almost 200 countries.

His own goals – and those of the Emirates – could become a source of conflict in the process. Doing one thing and not abandoning the other has been the maxim so far: The petrostates intend to establish the renewable business – and further expand the fossil business before possibly scaling it back. Carbon capture and storage (CCS), the capture and underground storage of climate-damaging carbon dioxide, is supposed to help achieve this balancing act. The technology is supposed to legitimize the dirty burning of fossil fuels in the future.

The fact that the expensive, energy-intensive and underdeveloped CCS technology has only made a small contribution to the transformation so far does not seem to faze Al Jaber. He is betting on the future and that global market maturity will be achieved in a few years.

On the other hand, it will probably soon show whether he is actually interested in saving the world from climate change. The world will know more about Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber in two weeks. Marc Winkelmann