On the fifth day of COP28 yesterday, the points of contention in the negotiations became increasingly clear: should the world phase out fossil fuels or just fossil emissions? The latter would lead to an important role for the controversial Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technology. Bernhard Pötter has taken a closer look at the lines of conflict in Dubai and outlines possible compromises for the final text. Nico Beckert breaks down the background to the fossil fuel phase-out for you. We also report on a new report by Climate Action Tracker, which describes CCS as a “sham solution” and strongly criticizes the current climate policy of states.

In keeping with Finance Day, we also take a look at money: Development Minister Svenja Schulze explains in an interview why private capital is needed for climate financing, and Lukas Scheid analyzes how international financial flows would have to be changed in order to meet the 1.5 degree target, according to a new report.

We also look at the criminalization of climate protests in Vietnam and around the world and what a gender-equitable climate policy could look like.

Ms Schulze, German Finance Minister Lindner has proposed cutting Germany’s international climate financing. Will Germany’s contribution to climate aid be lowered in the next budget?

Last year, we achieved a significant increase in international climate financing on a roughly constant budget. If we stick to our current plans, we will be able to maintain this level. If not, it will be more difficult.

How much resistance is there to the idea of mobilizing German money for development aid? Many surveys say: If we have to save money, let’s cut costs there.

The answer would probably be different if one were to ask: As an internationally integrated economy, should we really seal ourselves off? Should we really sever our partnerships with countries that we need to solve our shared problems? Development policy is expanding these partnerships that are vital for Germany. This is not a nice-to-have, but it is in Germany’s interest. That is why I am in favor of ensuring that we remain in a position to act even with a smaller national budget.

Here at the conference, the Emirates simply announced a climate investment fund of 30 billion dollars. And your government just revoked 60 billion for climate action. How does that make you feel as a minister?

I don’t see any connection there. We have a court ruling that we will comply with. But we are now at the COP to advance climate action here. We got off to a great start with the new fund for dealing with climate damage and the first donors. This has triggered what we hoped for, and the first pledges are now coming in, much faster and more substantially than expected. And we need more money if humanity wants to win the fight against climate change.

There is always talk of shifting trillions, not billions, from the fossil fuel economy to renewables. Where is this money supposed to come from?

Effective climate action can never be achieved with public money alone. Above all, private capital is needed. That’s why I believe it’s right for private investors to invest in climate action and talk about it at the COP. But we have to be careful. Not everything that is labeled climate action is also international climate financing in the narrower sense. At the COP, this primarily means supporting developing countries in their efforts against climate change.

How do you intend to increase the capital?

Germany has already introduced one idea for public capital: Our hybrid capital to the World Bank, where we provide 300 million euros so that the World Bank can organize up to 2.4 billion euros in low-cost capital for developing countries. These are effective levers because they allow us to cushion part of the risk with public money in order to mobilize private capital. But we need more of that.

Wouldn’t it make sense to generate additional income for countries to help tackle climate change, for example, through levies and taxes? There are ideas for levies on air traffic, fossil fuels and shipping.

We have been discussing this for a very long time and I’m very much in favor of it. But unfortunately, the global community is moving far too slowly because we need agreement between everyone. I’m not giving up, these are good ideas. But we know how difficult it was for Olaf Scholz to negotiate a global minimum tax back then. And that would be a new tax, something like that is difficult to achieve.

If you want to mobilize private capital for climate action, will it not primarily flow into emission reduction projects and, for example, energy projects that are business models? For instance, won’t adaptation measures fall by the wayside?

Exactly. That is why limited public funds must also be channeled more into adaptation. We are trying to divide our German climate financing roughly equally between mitigation and adaptation, which we manage well by international comparison. When it comes to mitigation, achieving a return on investment is indeed easier. If renewable energies are fed into a grid in a country with energy poverty, that could be a business model. We can use public money to help make these deals happen.

But, enabling farmers to build a dam is not a business model. Isn’t a big part of the financial debate bypassing the poorest of the poor? Shouldn’t this be public money?

We need both. With loss and damage, we are mainly talking about public money, I don’t see a business model there, either. But with the new loss and damage fund, we have managed to get the host country, the United Arab Emirates, to contribute. This is a breakthrough, as the UAE is considered a developing country under UN rules. Now, we are finally emerging from these old trenches. So far, it was often like this: The North wanted to talk about mitigation, the South about climate damage. Now, this front is finally breaking down.

So far, there is a one-off amount of around 600 million dollars in the loss and damage pot. However, up to 300 billion annually is needed. Is this the infamous drop in the ocean?

We need a lot more capital. That is why getting private money on board is all the more important wherever there are business models. This can relieve the pressure on tight public budgets. Obviously, the 0.7 percent of gross domestic product developed countries have pledged as funding for development will not solve the climate and biodiversity crisis or eradicate poverty and hunger. We must also channel the rest, all financial flows, into the proper, green channels. This must also be discussed at a COP in this way.

Do you see any progress? We only see much enthusiasm for private capital here.

It is still too early to tell. But we must harness the momentum of this conference for more public aid, more private investment and the right framework conditions.

The debate on phasing out fossil fuels and CCS is becoming the main dispute at COP28. On the one side, the oil and gas countries and COP President Sultan Al Jaber emphasize at every opportunity that they favor CCS as a way of reducing carbon emissions. On the other side, a united front of countries, scientists and think tanks favoring ambitious climate action are fighting for the strictest possible decision to phase out fossil fuels. They aim to prevent CCS from being included as an important solution in the final declaration.

The latest move in this battle comes from a new Oxford University study: It claims that an energy policy with a high proportion of CCS would result in additional costs of around 30 trillion dollars worldwide by 2050 – about one trillion more per year than a policy based on efficiency and renewables. According to the researchers, CCS has not become significantly cheaper than wind, solar and storage in the past 40 years. Economies that choose this path of decarbonization instead of renewables “risk being at a competitive disadvantage.”

Headwinds are also coming from the latest Climate Action Tracker, a think tank project that annually analyzes climate policy. It concludes that CCS is one of the wrong solutions, perpetuating the world’s dependence on fossil fuels.

Critics also cite the International Energy Agency (IEA). It has long supported the OECD’s fossil energy policy. However, its own report on CCS states that, although the technology is an important technology for net zero in “certain sectors and circumstances,” it is “not a way to retain the status quo.”

If fossil fuels continue to be used as they are now, the IEA estimates that a total of 32 billion tonnes of CO2 would have to be stored by 2050, 23 billion of which would be captured directly from the air (DAC). The energy required for this technology alone would be as high as global electricity consumption in 2022. Only 45 million tonnes of CO2 are currently stored each year – and three-quarters of this is used for more efficient oil and gas production (EOR).

This does not impress proponents of CCS. COP President Al Jaber has not yet shown a clear position. He has repeatedly emphasized that he does not see fossil fuels as the problem, but emissions – and that CCS must become “commercially viable.” However, he has also consistently mentioned that the era of fossil fuels is ending and that the industry needs to change its focus. Al Jaber likes to refer to the 1.5-degree limit as the “North Star” of the negotiations – and he also says that global emissions must be reduced by 43 percent by 2030.

Al Jaber has not yet explained how this can be accomplished in such a short time with the barely existing CCS capacities and in light of the IEA assessment. Instead, his remarks from November surfaced at the COP, claiming that there was no scientific basis for phasing out fossil fuels.

Renowned climate scientists Michael Mann and Jean Pascal van Ypersle reacted to this with an open letter in which they defined red lines “on behalf of the climate system”: “Humanity needs to agree on the phasing out of fossil fuels by 2050, and on stopping net deforestation at the same time,” they wrote.

By contrast, Al Jaber has received support from the oil industry. Exxon CEO Darren Woods confirmed Al Jaber’s opinion that society should “focus on the real problem, the emissions,” and not talk about phasing out fossil fuels. The “Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter” signed at COP28 by 50 companies, which account for 40 percent of global oil production, also lists investment in “renewables, low-carbon fuels and negative emissions technologies” among its key actions.

This conflict will be a hurdle in the tough negotiations on a final declaration that has now begun. If the conference is to be brought to a successful conclusion, a compromise must be reached on this issue. However, the positions of the various countries and groups differ significantly: The USA intends to keep its important oil and gas production alive with CCS and has invested up to three billion dollars in subsidies for this in the Inflation Reduction Act IRA investment package. On the other hand, island states and other small countries demand a fossil fuel phase-out without compromise. The EU has struggled to agree to accept CCS for the industry, but has otherwise called for an energy sector “predominantly free of fossil fuels well before 2050.” India, on the other hand, has no particular interest in CCS – but opposes possible indirect consequences for its coal industry. China has not made any significant statements on the issue.

Negotiators are currently eagerly searching for a formulation that is vague enough to allow some leeway but firm enough for progress. Some formulations on the table include:

However, existing texts will probably be used as a template for an agreement on the Global Stocktake decision. This has not been easy in the past. The G20 energy ministers failed to agree on this point this year. Negotiating circles claim that Saudi Arabia, in particular, exerted massive pressure.

The heads of government themselves gave an important indication of a possible compromise wording in their final document of the Climate Action Summit after the first two days of COP28. The wording found there is: “The phase down of fossil fuels in support of a transition consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C.” The heads of state and government could live with this. It remains to be seen whether it can serve as the basis for a viable compromise at COP28.

Non Thi To Nhien, Executive Director of the Vietnam Initiative for Energy Transition, was arrested in September for “appropriating documents.” The scientist had worked with various international organizations on energy transition issues.

This is just one of several cases in Vietnam in which climate activists end up in prison for alleged tax offenses. Last year, another case caused an international stir: Nguy Thi Khanh, who received the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2018 for her commitment to sustainable energy strategies, was jailed for alleged tax fraud. She was surprisingly released in May this year. In 2022, at least three other activists – Dang Dinh Bach, Mai Phan Loi and Bach Hung Duong – were arrested for alleged tax offenses.

Climate activists in Vietnam feel increasingly intimidated in this context. According to Human Rights Watch, the country’s communist regime uses vaguely worded tax laws against people who “threaten its power.” According to Project 88, a US-based NGO that campaigns for freedom of expression in Vietnam, there is evidence that activists are being silenced in this way. It found indications of “irregularities in criminal procedures.” The NGO claims that the Vietnamese Communist Party feels threatened by civil society actors.

These human rights violations are also concerning in connection with the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), which Vietnam signed last year with international partners, including the EU and the USA. Vietnam stands to receive more than 15 billion US dollars through the JETP to enable a “just energy transition.” Last Friday, Vietnam’s Prime Minister Phạm Minh Chính presented the Resource Mobilization Plan at COP28, which sets out exactly how the country intends to use the billions.

Hoang Thi Minh Hong, who was arrested in September, was involved in the implementation of the JETP. Javier Garate from the non-governmental organization Global Witness wants Western governments to exert more pressure in this context to safeguard the rights of activists in the country.

Climate activists around the world are increasingly reporting persecution, arrests and criminalization. According to Global Witness, 177 environmental activists were killed worldwide in 2022. Around 90 percent of these murders occurred in Latin America, with at least 39 people dying in the Amazon region. As the data situation for Africa is poor, there could have been even more murders there, Javier Garate from Global Witness told Table.Media. Moreover, the killings are only the tip of the iceberg; there are already frequent threats or violence before that.

The criminalization of environmental protests has recently become a global phenomenon and a frequently used tool to silence activists, said Mary Lawlor, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights. “Legal repression against climate activists is also a growing problem,” says Betsy Apple. She is the managing director of the US non-governmental organization Global Climate Legal Defense. Her organization supports people on almost every continent, for example, 16 activists in Uganda who are campaigning against the East African crude oil pipeline.

According to Apple, the criminalization of climate activism can take very different forms:

While it was mainly repressive states that tried to quell protests in the past, human rights lawyer Apple is now also seeing a wave of criminalization in Western democracies such as the USA, the UK and Germany. In Germany, for example, the public prosecutor’s office in Munich raided members of the “Last Generation” on charges of founding a criminal organization.

The fact that governments and police are increasingly reacting harshly and aggressively to protests is also because forms of protest have changed. For instance, civil disobedience is becoming a more regular form of protest for groups such as the “Last Generation” or “Just Stop Oil.”

Cases in the Global South and Europe or the USA can only be compared to a limited extent, says Garate from Global Witness. What is comparable is that it can also be observed in Europe that the law is deliberately construed against activists. However, there is a clear difference in whether and to what extent people can rely on the rule of law. “Legal systems in Western democracies are not perfect. But at least they are usually relatively independent,” Apple says, and you can appeal against arrests or sentences. However, this is hardly possible in countries like Vietnam. Garate, therefore, sees international treaties such as the Escazu Agreement, aimed explicitly at protecting environmentalists, as a step in the right direction.

Betsy Apple says it is vital that activists have access to legal advice as climate protest is increasingly criminalized. In the run-up to COP28, concerns were repeatedly raised about the extent to which protest would be possible. Lawyer Apple also sees a genuine risk of activists being exposed to repression or criminalization at the climate conference. That is why her organization has held webinars to prepare activists traveling to Dubai for the legal situation on the ground. During the climate conference, the NGO advises activists via online chat.

One of the biggest issues at COP28 is the debate on phasing out fossil fuels. At previous COPs, countries avoided this controversial topic. Only at COP26 and COP27 were fossil fuels debated more seriously.

Coal, oil and gas account for over 80 percent of the global energy supply. According to IEA data, this share will fall to 73 percent by 2030 – but that is not enough. In order to keep the 2-degree target within reach, a large part of fossil fuels – 80 percent of coal, 50 percent of gas reserves and 30 percent of oil reserves – must be abandoned. The IEA net-zero scenario shows that the use of fossil fuels must drop by around 80 percent by 2050 in order to keep the 1.5-degree target achievable.

By 2030, this will already require cutting:

The most influential countries are only willing to phase out “unabated” fossil fuels. COP President Al Jaber favors phasing out emissions – i.e., using the controversial CCS technology to capture and store CO2. The USA and the other G7 countries argue similarly.

Other large producers, including Russia and Saudi Arabia, strictly oppose restrictions on certain energy sources. China considers the phase-out “unrealistic.” The African group of states wants to continue using fossil fuels to advance their development.

By contrast, the group of least developed countries (LDCs), which are usually particularly vulnerable to climate change, support a phase-out. The EU plays a special role. The EU member states are only in favor of a general phase-out of unabated fossil fuels. However, in the energy sector, they aim for an energy sector “predominantly free of fossil fuels” – i.e., without the use of CCS. However, there is confusion about the word “predominantly.”

The use of CCS technology is also highly controversial. It is expensive, far from mature and will only be able to reduce some of the emissions.

Due to the opposition of countries such as Russia and Saudi Arabia, it is unlikely that a binding fossil fuel phase-out will be adopted at COP. It is more likely that frontrunner alliances such as the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA) will be formed, which agree on a voluntary phase-out. Other projects such as Just Energy Transition Partnerships or more detailed commitments to phase out fossil subsidies are also conceivable.

Dec. 5, 9 a.m., EU Pavilion

Discussion Localizing energy: cities and companies teaming up for the local energy transition

This event highlights successful public-private partnerships for energy efficiency, distributed energy solutions, and urban transport. It includes a roundtable discussion on accelerating local energy transition and emissions reduction. Info

Dec. 5, 9:30 a.m., Presidency Roundtable – Al Saih

Round table High Level Roundtable on Hydrogen

Hydrogen can make an important contribution to decarbonization. This High-Level Ministerial-CEO Roundtable on Hydrogen will mark the launch of the flagship COP28 initiatives designed to accelerate commercialisation of hydrogen projects facilitating the transition to net zero and unlock the climate and socio-economic benefits of cross-border supply chains. Info

Dec. 5, 3:30 p.m., Food Pavilion

Publication National actions for climate and food: Launch of new NDC guidance tool for agriculture and food systems

Food production is responsible for a significant proportion of emissions. Guidelines will be published at the event to help restructure green food systems and agriculture. Info

Dec. 5, 4 p.m., The Women’s Pavilion – Humanitarian Hub

Panel discussion Disability Rights and the Climate Crisis: Climate Disasters, Extreme Weather Events, and Humanitarian Response

This event focuses on the intersection of the rights of persons with disabilities, the climate crisis, and humanitarian response. It is organized by Human Rights Watch, New York University and the International Disability Alliance. Info

Dec. 5, 5:45 p.m., Resilience Hub

Award ceremony Global Center on Adaptation (GCA) 2023 Local Adaptation Champions Awards Ceremony

The Global Center on Adaptation (GCA) will announce the winners of the 2023 Local Adaptation Champions Awards. The awards recognize innovative, exemplary, inspiring and scalable local efforts that make vulnerable communities more climate resilient. Info

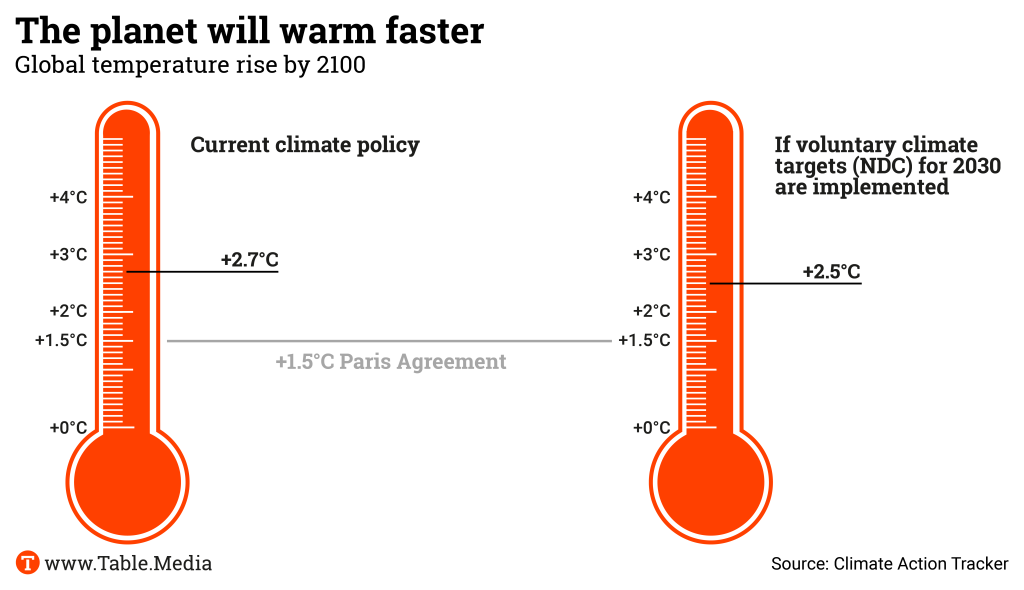

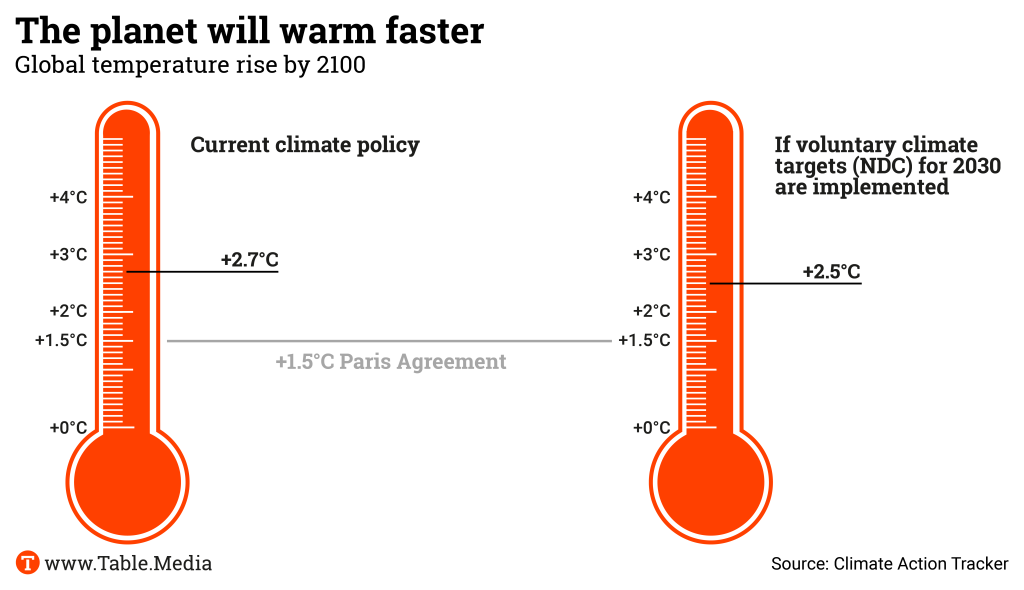

If all signatory countries to the Paris Climate Agreement implement their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) by 2030, our planet will warm by 2.5 degrees by 2100. This is the result of a new calculation by the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), published today at COP28. Last year, the CAT was still at 2.4 degrees warming.

If the actual climate policy of all countries is taken as the basis for the forecast instead of the climate targets, this even results in global warming of 2.7 degrees by 2100. This is the same result as two years ago. Back then, governments agreed to tighten their climate targets at COP26 in Glasgow.

But instead of effective climate policy, some governments have since been pushing pseudo-solutions such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) “to maintain the world’s dependence on fossil fuels,” the CAT analysts write. “Everywhere in these climate negotiations we hear the word ‘unabated’,” criticizes Niklas Höhne, co-founder of the New Climate Institute involved in the CAT and one of the authors of the new report. He demanded that governments “stop adopting false solutions such as carbon capture and storage with fossil fuels.”

CCS plays a key role in the negotiations in Dubai. Countries opposing an agreement on the global phase-out of all fossil fuels put their hopes in this technology.

The fact that the warming forecast by the CAT has actually increased slightly in this year’s report is largely due to the fact that it includes the current policy measures of countries with weak NDCs in its calculations. Accordingly, the measures lead to higher emissions than predicted in the past. One of the main drivers of the effect was Indonesia due to the expansion of its coal-fired power plants, which increased its emissions by 21 percent last year.

For the next NDCs, which have the year 2035 as a target, the CAT urges countries to:

International financial experts have called for drastically increasing international climate finance and made recommendations on how the increase can contribute to achieving the 1.5-degree target. In the second report of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (IHLEG), the authors call for this to be achieved by 2030:

These are not figures that can be plucked out of the air and then negotiated down, says Nicholas Stern, British professor of economics and IHLEG chairman. “When we talk about finance, we’re talking about finance with a purpose, the purpose is delivery on Paris.” The first thing is to release the investments in the first place.

Therefore, the IHLEG recommends “targeted” cooperation between countries, the private sector, multilateral development banks (MDBs) and private donors. This should create “investment pipelines” that increase the fiscal leeway of recipient countries. This would also require systemic reforms to the financial system, such as the role of MDBs, as well as debt relief measures.

This “simple legal instrument” of debt break clauses allows underinsured and uninsured countries to bridge a financing gap, said Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados and initiator of the Bridgetown Agenda, in Dubai on Monday. The countries would thus have the financial leeway they need and lenders would not be exposed to any risk.

But Mottley wants to go further to fund loss and damage and climate change adaptation. A tax on global financial services, set at a 0.1 percent rate, could raise 420 billion US dollars for it, “not 720 million where we are today.” 720 million is the amount that countries have pledged so far at COP28 for the loss and damage fund. If last year’s oil and gas profits (around four trillion US dollars) were then taxed at five percent, a further 200 billion would be available, Mottley continued.

On Monday, the UK, France, the World Bank, the African Development Bank Group, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the Inter-American Development Bank announced plans to expand the use of Climate Resilient Debt Clauses in their lending, according to the COP28 presidency. These clauses would trigger a debt break when countries are affected by natural disasters.

France and Japan are also said to have expressed their support for the African Development Bank to use the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing rights for climate and development, the presidency announced. Special drawing rights are foreign exchange reserves held by the IMF. Passing them on to development banks could also free up funds for climate financing in developing countries. luk

According to a Global Carbon Budget 2023 report published today, fossil carbon emissions will reach a new record high this year. Compared to 2022, they will increase by 1 percent to 36.8 billion tons. However, emissions have decreased in 26 countries, which account for just over a quarter of global carbon emissions. In other countries, the increase has slowed down. However, according to the 121 scientists involved in the Global Carbon Project, this will not achieve the necessary trend reversal towards net zero emissions.

China (+ +4 percent) and India (+ 8.2 percent), in particular, are responsible for increased fossil carbon emissions. China’s emissions from oil consumption and India’s coal emissions have increased by almost ten percent. At the same time, the EU’s fossil carbon emissions fell by 7. 4 percent and the USA’s by three percent. Consolidated data shows that India’s fossil fuel emissions have been higher than those of the EU since 2022 – although per capita emissions in the EU are three times higher than in India.

Unlike fossil fuel emissions, emissions from land use change, such as deforestation, appear to have been falling slightly for two decades, according to the report. This is due to less deforestation and more stable capacities for carbon sequestration through (re)afforestation. However, the trend is unconfirmed because data still shows considerable uncertainty. On average, emissions from land use change amounted to 4.7 billion tons of CO2 annually between 2013 and 2022. Brazil, Indonesia and the DR Congo account for 55 percent of these carbon emissions.

The current level of (re)afforestation cannot compensate for the additional carbon emissions caused by deforestation. The researchers came to this conclusion by calculating the emissions from permanent deforestation. On average, between 2013 and 2022, 4.2 billion tons of CO2 per year from deforestation are offset by 1.9 billion tons of CO2 saved from (re)afforestation over the same period. nh

By 2050, climate change could drive 159 million women and girls into poverty and cause additional hunger. The climate crisis does not affect genders equally: For instance, women are more frequently victims of violence or displacement after extreme weather events.

That is why UN Women published a Feminist Climate Justice report on Gender Equality Day at COP28. It calls for better consideration of the needs of the different genders in climate action. The report’s author, Laura Turquet, positively notes that gender justice and finance are being discussed on the same day at the climate conference – the implementation of women’s rights urgently needs more money.

In the report, UN Women makes concrete demands:

Hillary Clinton, former US presidential candidate, said at COP28 that the low proportion of women at the climate conference was a major concern. There is a “visible pushback” against women’s rights, adding that women’s concerns are not being heard enough. kul

Canada’s environment minister Steven Guilbeault arrives at this year’s COP28 conference in Dubai amid a tumultuous time at home. A recent federal audit found his government is not on track to meet its 2030 emissions reductions target. The long-awaited policy to put a cap on emissions from Canada’s oil and gas sector has yet to be announced and the industry continues to ramp up production.

But the minister is facing the most heat for his own government’s actions: weakening Canada’s carbon pricing system. By exempting home heating oil from the federal carbon tax for the next three years, he has angered his supporters and played into the rhetoric of the Conservative Party’s “axe the tax” campaign. There is speculation that Guilbeault might resign as critics call the signature policy “effectively dead.”

Despite this, at this year’s climate conference, Guilbeault says he will continue working with Canada’s partners on phasing out coal, reduce methane emissions, financing climate adaptation, and encouraging other countries to put a price on carbon.

“I love being environment minister,” he said at a virtual press conference on Nov. 16 responding to reporters’ questions about his possible resignation. “It’s a dream job for me.”

It’s not every day that a former Greenpeace bureau chief is chosen to craft a country’s climate policy. Guilbeault’s first act of protest occurred in his hometown of La Tuque, Quebec at the age of five when he climbed a tree that a developer intended to cut down. It was the beginning of a career in climate activism and finance that spanned decades.

In 2001, Guilbeault and another Greenpeace activist climbed Toronto’s CN Tower to unfurl a sign that criticized Canada’s failure to ratify the 1997 Kyoto protocol. The stunt saw him charged with public mischief. He stayed on at Greenpeace until 2007, when he returned to Équiterre, a Quebec-based environmental non-profit he co-founded a decade prior. In 2018, he left the organization to run for office.

When Guilbeault was chosen as Canada’s Environment and Climate Change Minister the following year, the decision sparked hope on the left and nervousness on the right. Now, nearly two years into the job, he is credited for creating Canada’s first climate change adaptation strategy, committing to an ambitious 2030 conservation goal, making large investments in the clean energy and transportation industries, and introducing a price on carbon. Krista Hessey

On the fifth day of COP28 yesterday, the points of contention in the negotiations became increasingly clear: should the world phase out fossil fuels or just fossil emissions? The latter would lead to an important role for the controversial Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technology. Bernhard Pötter has taken a closer look at the lines of conflict in Dubai and outlines possible compromises for the final text. Nico Beckert breaks down the background to the fossil fuel phase-out for you. We also report on a new report by Climate Action Tracker, which describes CCS as a “sham solution” and strongly criticizes the current climate policy of states.

In keeping with Finance Day, we also take a look at money: Development Minister Svenja Schulze explains in an interview why private capital is needed for climate financing, and Lukas Scheid analyzes how international financial flows would have to be changed in order to meet the 1.5 degree target, according to a new report.

We also look at the criminalization of climate protests in Vietnam and around the world and what a gender-equitable climate policy could look like.

Ms Schulze, German Finance Minister Lindner has proposed cutting Germany’s international climate financing. Will Germany’s contribution to climate aid be lowered in the next budget?

Last year, we achieved a significant increase in international climate financing on a roughly constant budget. If we stick to our current plans, we will be able to maintain this level. If not, it will be more difficult.

How much resistance is there to the idea of mobilizing German money for development aid? Many surveys say: If we have to save money, let’s cut costs there.

The answer would probably be different if one were to ask: As an internationally integrated economy, should we really seal ourselves off? Should we really sever our partnerships with countries that we need to solve our shared problems? Development policy is expanding these partnerships that are vital for Germany. This is not a nice-to-have, but it is in Germany’s interest. That is why I am in favor of ensuring that we remain in a position to act even with a smaller national budget.

Here at the conference, the Emirates simply announced a climate investment fund of 30 billion dollars. And your government just revoked 60 billion for climate action. How does that make you feel as a minister?

I don’t see any connection there. We have a court ruling that we will comply with. But we are now at the COP to advance climate action here. We got off to a great start with the new fund for dealing with climate damage and the first donors. This has triggered what we hoped for, and the first pledges are now coming in, much faster and more substantially than expected. And we need more money if humanity wants to win the fight against climate change.

There is always talk of shifting trillions, not billions, from the fossil fuel economy to renewables. Where is this money supposed to come from?

Effective climate action can never be achieved with public money alone. Above all, private capital is needed. That’s why I believe it’s right for private investors to invest in climate action and talk about it at the COP. But we have to be careful. Not everything that is labeled climate action is also international climate financing in the narrower sense. At the COP, this primarily means supporting developing countries in their efforts against climate change.

How do you intend to increase the capital?

Germany has already introduced one idea for public capital: Our hybrid capital to the World Bank, where we provide 300 million euros so that the World Bank can organize up to 2.4 billion euros in low-cost capital for developing countries. These are effective levers because they allow us to cushion part of the risk with public money in order to mobilize private capital. But we need more of that.

Wouldn’t it make sense to generate additional income for countries to help tackle climate change, for example, through levies and taxes? There are ideas for levies on air traffic, fossil fuels and shipping.

We have been discussing this for a very long time and I’m very much in favor of it. But unfortunately, the global community is moving far too slowly because we need agreement between everyone. I’m not giving up, these are good ideas. But we know how difficult it was for Olaf Scholz to negotiate a global minimum tax back then. And that would be a new tax, something like that is difficult to achieve.

If you want to mobilize private capital for climate action, will it not primarily flow into emission reduction projects and, for example, energy projects that are business models? For instance, won’t adaptation measures fall by the wayside?

Exactly. That is why limited public funds must also be channeled more into adaptation. We are trying to divide our German climate financing roughly equally between mitigation and adaptation, which we manage well by international comparison. When it comes to mitigation, achieving a return on investment is indeed easier. If renewable energies are fed into a grid in a country with energy poverty, that could be a business model. We can use public money to help make these deals happen.

But, enabling farmers to build a dam is not a business model. Isn’t a big part of the financial debate bypassing the poorest of the poor? Shouldn’t this be public money?

We need both. With loss and damage, we are mainly talking about public money, I don’t see a business model there, either. But with the new loss and damage fund, we have managed to get the host country, the United Arab Emirates, to contribute. This is a breakthrough, as the UAE is considered a developing country under UN rules. Now, we are finally emerging from these old trenches. So far, it was often like this: The North wanted to talk about mitigation, the South about climate damage. Now, this front is finally breaking down.

So far, there is a one-off amount of around 600 million dollars in the loss and damage pot. However, up to 300 billion annually is needed. Is this the infamous drop in the ocean?

We need a lot more capital. That is why getting private money on board is all the more important wherever there are business models. This can relieve the pressure on tight public budgets. Obviously, the 0.7 percent of gross domestic product developed countries have pledged as funding for development will not solve the climate and biodiversity crisis or eradicate poverty and hunger. We must also channel the rest, all financial flows, into the proper, green channels. This must also be discussed at a COP in this way.

Do you see any progress? We only see much enthusiasm for private capital here.

It is still too early to tell. But we must harness the momentum of this conference for more public aid, more private investment and the right framework conditions.

The debate on phasing out fossil fuels and CCS is becoming the main dispute at COP28. On the one side, the oil and gas countries and COP President Sultan Al Jaber emphasize at every opportunity that they favor CCS as a way of reducing carbon emissions. On the other side, a united front of countries, scientists and think tanks favoring ambitious climate action are fighting for the strictest possible decision to phase out fossil fuels. They aim to prevent CCS from being included as an important solution in the final declaration.

The latest move in this battle comes from a new Oxford University study: It claims that an energy policy with a high proportion of CCS would result in additional costs of around 30 trillion dollars worldwide by 2050 – about one trillion more per year than a policy based on efficiency and renewables. According to the researchers, CCS has not become significantly cheaper than wind, solar and storage in the past 40 years. Economies that choose this path of decarbonization instead of renewables “risk being at a competitive disadvantage.”

Headwinds are also coming from the latest Climate Action Tracker, a think tank project that annually analyzes climate policy. It concludes that CCS is one of the wrong solutions, perpetuating the world’s dependence on fossil fuels.

Critics also cite the International Energy Agency (IEA). It has long supported the OECD’s fossil energy policy. However, its own report on CCS states that, although the technology is an important technology for net zero in “certain sectors and circumstances,” it is “not a way to retain the status quo.”

If fossil fuels continue to be used as they are now, the IEA estimates that a total of 32 billion tonnes of CO2 would have to be stored by 2050, 23 billion of which would be captured directly from the air (DAC). The energy required for this technology alone would be as high as global electricity consumption in 2022. Only 45 million tonnes of CO2 are currently stored each year – and three-quarters of this is used for more efficient oil and gas production (EOR).

This does not impress proponents of CCS. COP President Al Jaber has not yet shown a clear position. He has repeatedly emphasized that he does not see fossil fuels as the problem, but emissions – and that CCS must become “commercially viable.” However, he has also consistently mentioned that the era of fossil fuels is ending and that the industry needs to change its focus. Al Jaber likes to refer to the 1.5-degree limit as the “North Star” of the negotiations – and he also says that global emissions must be reduced by 43 percent by 2030.

Al Jaber has not yet explained how this can be accomplished in such a short time with the barely existing CCS capacities and in light of the IEA assessment. Instead, his remarks from November surfaced at the COP, claiming that there was no scientific basis for phasing out fossil fuels.

Renowned climate scientists Michael Mann and Jean Pascal van Ypersle reacted to this with an open letter in which they defined red lines “on behalf of the climate system”: “Humanity needs to agree on the phasing out of fossil fuels by 2050, and on stopping net deforestation at the same time,” they wrote.

By contrast, Al Jaber has received support from the oil industry. Exxon CEO Darren Woods confirmed Al Jaber’s opinion that society should “focus on the real problem, the emissions,” and not talk about phasing out fossil fuels. The “Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter” signed at COP28 by 50 companies, which account for 40 percent of global oil production, also lists investment in “renewables, low-carbon fuels and negative emissions technologies” among its key actions.

This conflict will be a hurdle in the tough negotiations on a final declaration that has now begun. If the conference is to be brought to a successful conclusion, a compromise must be reached on this issue. However, the positions of the various countries and groups differ significantly: The USA intends to keep its important oil and gas production alive with CCS and has invested up to three billion dollars in subsidies for this in the Inflation Reduction Act IRA investment package. On the other hand, island states and other small countries demand a fossil fuel phase-out without compromise. The EU has struggled to agree to accept CCS for the industry, but has otherwise called for an energy sector “predominantly free of fossil fuels well before 2050.” India, on the other hand, has no particular interest in CCS – but opposes possible indirect consequences for its coal industry. China has not made any significant statements on the issue.

Negotiators are currently eagerly searching for a formulation that is vague enough to allow some leeway but firm enough for progress. Some formulations on the table include:

However, existing texts will probably be used as a template for an agreement on the Global Stocktake decision. This has not been easy in the past. The G20 energy ministers failed to agree on this point this year. Negotiating circles claim that Saudi Arabia, in particular, exerted massive pressure.

The heads of government themselves gave an important indication of a possible compromise wording in their final document of the Climate Action Summit after the first two days of COP28. The wording found there is: “The phase down of fossil fuels in support of a transition consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C.” The heads of state and government could live with this. It remains to be seen whether it can serve as the basis for a viable compromise at COP28.

Non Thi To Nhien, Executive Director of the Vietnam Initiative for Energy Transition, was arrested in September for “appropriating documents.” The scientist had worked with various international organizations on energy transition issues.

This is just one of several cases in Vietnam in which climate activists end up in prison for alleged tax offenses. Last year, another case caused an international stir: Nguy Thi Khanh, who received the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2018 for her commitment to sustainable energy strategies, was jailed for alleged tax fraud. She was surprisingly released in May this year. In 2022, at least three other activists – Dang Dinh Bach, Mai Phan Loi and Bach Hung Duong – were arrested for alleged tax offenses.

Climate activists in Vietnam feel increasingly intimidated in this context. According to Human Rights Watch, the country’s communist regime uses vaguely worded tax laws against people who “threaten its power.” According to Project 88, a US-based NGO that campaigns for freedom of expression in Vietnam, there is evidence that activists are being silenced in this way. It found indications of “irregularities in criminal procedures.” The NGO claims that the Vietnamese Communist Party feels threatened by civil society actors.

These human rights violations are also concerning in connection with the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), which Vietnam signed last year with international partners, including the EU and the USA. Vietnam stands to receive more than 15 billion US dollars through the JETP to enable a “just energy transition.” Last Friday, Vietnam’s Prime Minister Phạm Minh Chính presented the Resource Mobilization Plan at COP28, which sets out exactly how the country intends to use the billions.

Hoang Thi Minh Hong, who was arrested in September, was involved in the implementation of the JETP. Javier Garate from the non-governmental organization Global Witness wants Western governments to exert more pressure in this context to safeguard the rights of activists in the country.

Climate activists around the world are increasingly reporting persecution, arrests and criminalization. According to Global Witness, 177 environmental activists were killed worldwide in 2022. Around 90 percent of these murders occurred in Latin America, with at least 39 people dying in the Amazon region. As the data situation for Africa is poor, there could have been even more murders there, Javier Garate from Global Witness told Table.Media. Moreover, the killings are only the tip of the iceberg; there are already frequent threats or violence before that.

The criminalization of environmental protests has recently become a global phenomenon and a frequently used tool to silence activists, said Mary Lawlor, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights. “Legal repression against climate activists is also a growing problem,” says Betsy Apple. She is the managing director of the US non-governmental organization Global Climate Legal Defense. Her organization supports people on almost every continent, for example, 16 activists in Uganda who are campaigning against the East African crude oil pipeline.

According to Apple, the criminalization of climate activism can take very different forms:

While it was mainly repressive states that tried to quell protests in the past, human rights lawyer Apple is now also seeing a wave of criminalization in Western democracies such as the USA, the UK and Germany. In Germany, for example, the public prosecutor’s office in Munich raided members of the “Last Generation” on charges of founding a criminal organization.

The fact that governments and police are increasingly reacting harshly and aggressively to protests is also because forms of protest have changed. For instance, civil disobedience is becoming a more regular form of protest for groups such as the “Last Generation” or “Just Stop Oil.”

Cases in the Global South and Europe or the USA can only be compared to a limited extent, says Garate from Global Witness. What is comparable is that it can also be observed in Europe that the law is deliberately construed against activists. However, there is a clear difference in whether and to what extent people can rely on the rule of law. “Legal systems in Western democracies are not perfect. But at least they are usually relatively independent,” Apple says, and you can appeal against arrests or sentences. However, this is hardly possible in countries like Vietnam. Garate, therefore, sees international treaties such as the Escazu Agreement, aimed explicitly at protecting environmentalists, as a step in the right direction.

Betsy Apple says it is vital that activists have access to legal advice as climate protest is increasingly criminalized. In the run-up to COP28, concerns were repeatedly raised about the extent to which protest would be possible. Lawyer Apple also sees a genuine risk of activists being exposed to repression or criminalization at the climate conference. That is why her organization has held webinars to prepare activists traveling to Dubai for the legal situation on the ground. During the climate conference, the NGO advises activists via online chat.

One of the biggest issues at COP28 is the debate on phasing out fossil fuels. At previous COPs, countries avoided this controversial topic. Only at COP26 and COP27 were fossil fuels debated more seriously.

Coal, oil and gas account for over 80 percent of the global energy supply. According to IEA data, this share will fall to 73 percent by 2030 – but that is not enough. In order to keep the 2-degree target within reach, a large part of fossil fuels – 80 percent of coal, 50 percent of gas reserves and 30 percent of oil reserves – must be abandoned. The IEA net-zero scenario shows that the use of fossil fuels must drop by around 80 percent by 2050 in order to keep the 1.5-degree target achievable.

By 2030, this will already require cutting:

The most influential countries are only willing to phase out “unabated” fossil fuels. COP President Al Jaber favors phasing out emissions – i.e., using the controversial CCS technology to capture and store CO2. The USA and the other G7 countries argue similarly.

Other large producers, including Russia and Saudi Arabia, strictly oppose restrictions on certain energy sources. China considers the phase-out “unrealistic.” The African group of states wants to continue using fossil fuels to advance their development.

By contrast, the group of least developed countries (LDCs), which are usually particularly vulnerable to climate change, support a phase-out. The EU plays a special role. The EU member states are only in favor of a general phase-out of unabated fossil fuels. However, in the energy sector, they aim for an energy sector “predominantly free of fossil fuels” – i.e., without the use of CCS. However, there is confusion about the word “predominantly.”

The use of CCS technology is also highly controversial. It is expensive, far from mature and will only be able to reduce some of the emissions.

Due to the opposition of countries such as Russia and Saudi Arabia, it is unlikely that a binding fossil fuel phase-out will be adopted at COP. It is more likely that frontrunner alliances such as the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA) will be formed, which agree on a voluntary phase-out. Other projects such as Just Energy Transition Partnerships or more detailed commitments to phase out fossil subsidies are also conceivable.

Dec. 5, 9 a.m., EU Pavilion

Discussion Localizing energy: cities and companies teaming up for the local energy transition

This event highlights successful public-private partnerships for energy efficiency, distributed energy solutions, and urban transport. It includes a roundtable discussion on accelerating local energy transition and emissions reduction. Info

Dec. 5, 9:30 a.m., Presidency Roundtable – Al Saih

Round table High Level Roundtable on Hydrogen

Hydrogen can make an important contribution to decarbonization. This High-Level Ministerial-CEO Roundtable on Hydrogen will mark the launch of the flagship COP28 initiatives designed to accelerate commercialisation of hydrogen projects facilitating the transition to net zero and unlock the climate and socio-economic benefits of cross-border supply chains. Info

Dec. 5, 3:30 p.m., Food Pavilion

Publication National actions for climate and food: Launch of new NDC guidance tool for agriculture and food systems

Food production is responsible for a significant proportion of emissions. Guidelines will be published at the event to help restructure green food systems and agriculture. Info

Dec. 5, 4 p.m., The Women’s Pavilion – Humanitarian Hub

Panel discussion Disability Rights and the Climate Crisis: Climate Disasters, Extreme Weather Events, and Humanitarian Response

This event focuses on the intersection of the rights of persons with disabilities, the climate crisis, and humanitarian response. It is organized by Human Rights Watch, New York University and the International Disability Alliance. Info

Dec. 5, 5:45 p.m., Resilience Hub

Award ceremony Global Center on Adaptation (GCA) 2023 Local Adaptation Champions Awards Ceremony

The Global Center on Adaptation (GCA) will announce the winners of the 2023 Local Adaptation Champions Awards. The awards recognize innovative, exemplary, inspiring and scalable local efforts that make vulnerable communities more climate resilient. Info

If all signatory countries to the Paris Climate Agreement implement their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) by 2030, our planet will warm by 2.5 degrees by 2100. This is the result of a new calculation by the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), published today at COP28. Last year, the CAT was still at 2.4 degrees warming.

If the actual climate policy of all countries is taken as the basis for the forecast instead of the climate targets, this even results in global warming of 2.7 degrees by 2100. This is the same result as two years ago. Back then, governments agreed to tighten their climate targets at COP26 in Glasgow.

But instead of effective climate policy, some governments have since been pushing pseudo-solutions such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) “to maintain the world’s dependence on fossil fuels,” the CAT analysts write. “Everywhere in these climate negotiations we hear the word ‘unabated’,” criticizes Niklas Höhne, co-founder of the New Climate Institute involved in the CAT and one of the authors of the new report. He demanded that governments “stop adopting false solutions such as carbon capture and storage with fossil fuels.”

CCS plays a key role in the negotiations in Dubai. Countries opposing an agreement on the global phase-out of all fossil fuels put their hopes in this technology.

The fact that the warming forecast by the CAT has actually increased slightly in this year’s report is largely due to the fact that it includes the current policy measures of countries with weak NDCs in its calculations. Accordingly, the measures lead to higher emissions than predicted in the past. One of the main drivers of the effect was Indonesia due to the expansion of its coal-fired power plants, which increased its emissions by 21 percent last year.

For the next NDCs, which have the year 2035 as a target, the CAT urges countries to:

International financial experts have called for drastically increasing international climate finance and made recommendations on how the increase can contribute to achieving the 1.5-degree target. In the second report of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (IHLEG), the authors call for this to be achieved by 2030:

These are not figures that can be plucked out of the air and then negotiated down, says Nicholas Stern, British professor of economics and IHLEG chairman. “When we talk about finance, we’re talking about finance with a purpose, the purpose is delivery on Paris.” The first thing is to release the investments in the first place.

Therefore, the IHLEG recommends “targeted” cooperation between countries, the private sector, multilateral development banks (MDBs) and private donors. This should create “investment pipelines” that increase the fiscal leeway of recipient countries. This would also require systemic reforms to the financial system, such as the role of MDBs, as well as debt relief measures.

This “simple legal instrument” of debt break clauses allows underinsured and uninsured countries to bridge a financing gap, said Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados and initiator of the Bridgetown Agenda, in Dubai on Monday. The countries would thus have the financial leeway they need and lenders would not be exposed to any risk.

But Mottley wants to go further to fund loss and damage and climate change adaptation. A tax on global financial services, set at a 0.1 percent rate, could raise 420 billion US dollars for it, “not 720 million where we are today.” 720 million is the amount that countries have pledged so far at COP28 for the loss and damage fund. If last year’s oil and gas profits (around four trillion US dollars) were then taxed at five percent, a further 200 billion would be available, Mottley continued.

On Monday, the UK, France, the World Bank, the African Development Bank Group, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the Inter-American Development Bank announced plans to expand the use of Climate Resilient Debt Clauses in their lending, according to the COP28 presidency. These clauses would trigger a debt break when countries are affected by natural disasters.

France and Japan are also said to have expressed their support for the African Development Bank to use the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing rights for climate and development, the presidency announced. Special drawing rights are foreign exchange reserves held by the IMF. Passing them on to development banks could also free up funds for climate financing in developing countries. luk

According to a Global Carbon Budget 2023 report published today, fossil carbon emissions will reach a new record high this year. Compared to 2022, they will increase by 1 percent to 36.8 billion tons. However, emissions have decreased in 26 countries, which account for just over a quarter of global carbon emissions. In other countries, the increase has slowed down. However, according to the 121 scientists involved in the Global Carbon Project, this will not achieve the necessary trend reversal towards net zero emissions.

China (+ +4 percent) and India (+ 8.2 percent), in particular, are responsible for increased fossil carbon emissions. China’s emissions from oil consumption and India’s coal emissions have increased by almost ten percent. At the same time, the EU’s fossil carbon emissions fell by 7. 4 percent and the USA’s by three percent. Consolidated data shows that India’s fossil fuel emissions have been higher than those of the EU since 2022 – although per capita emissions in the EU are three times higher than in India.

Unlike fossil fuel emissions, emissions from land use change, such as deforestation, appear to have been falling slightly for two decades, according to the report. This is due to less deforestation and more stable capacities for carbon sequestration through (re)afforestation. However, the trend is unconfirmed because data still shows considerable uncertainty. On average, emissions from land use change amounted to 4.7 billion tons of CO2 annually between 2013 and 2022. Brazil, Indonesia and the DR Congo account for 55 percent of these carbon emissions.

The current level of (re)afforestation cannot compensate for the additional carbon emissions caused by deforestation. The researchers came to this conclusion by calculating the emissions from permanent deforestation. On average, between 2013 and 2022, 4.2 billion tons of CO2 per year from deforestation are offset by 1.9 billion tons of CO2 saved from (re)afforestation over the same period. nh

By 2050, climate change could drive 159 million women and girls into poverty and cause additional hunger. The climate crisis does not affect genders equally: For instance, women are more frequently victims of violence or displacement after extreme weather events.

That is why UN Women published a Feminist Climate Justice report on Gender Equality Day at COP28. It calls for better consideration of the needs of the different genders in climate action. The report’s author, Laura Turquet, positively notes that gender justice and finance are being discussed on the same day at the climate conference – the implementation of women’s rights urgently needs more money.

In the report, UN Women makes concrete demands:

Hillary Clinton, former US presidential candidate, said at COP28 that the low proportion of women at the climate conference was a major concern. There is a “visible pushback” against women’s rights, adding that women’s concerns are not being heard enough. kul

Canada’s environment minister Steven Guilbeault arrives at this year’s COP28 conference in Dubai amid a tumultuous time at home. A recent federal audit found his government is not on track to meet its 2030 emissions reductions target. The long-awaited policy to put a cap on emissions from Canada’s oil and gas sector has yet to be announced and the industry continues to ramp up production.

But the minister is facing the most heat for his own government’s actions: weakening Canada’s carbon pricing system. By exempting home heating oil from the federal carbon tax for the next three years, he has angered his supporters and played into the rhetoric of the Conservative Party’s “axe the tax” campaign. There is speculation that Guilbeault might resign as critics call the signature policy “effectively dead.”

Despite this, at this year’s climate conference, Guilbeault says he will continue working with Canada’s partners on phasing out coal, reduce methane emissions, financing climate adaptation, and encouraging other countries to put a price on carbon.

“I love being environment minister,” he said at a virtual press conference on Nov. 16 responding to reporters’ questions about his possible resignation. “It’s a dream job for me.”

It’s not every day that a former Greenpeace bureau chief is chosen to craft a country’s climate policy. Guilbeault’s first act of protest occurred in his hometown of La Tuque, Quebec at the age of five when he climbed a tree that a developer intended to cut down. It was the beginning of a career in climate activism and finance that spanned decades.

In 2001, Guilbeault and another Greenpeace activist climbed Toronto’s CN Tower to unfurl a sign that criticized Canada’s failure to ratify the 1997 Kyoto protocol. The stunt saw him charged with public mischief. He stayed on at Greenpeace until 2007, when he returned to Équiterre, a Quebec-based environmental non-profit he co-founded a decade prior. In 2018, he left the organization to run for office.

When Guilbeault was chosen as Canada’s Environment and Climate Change Minister the following year, the decision sparked hope on the left and nervousness on the right. Now, nearly two years into the job, he is credited for creating Canada’s first climate change adaptation strategy, committing to an ambitious 2030 conservation goal, making large investments in the clean energy and transportation industries, and introducing a price on carbon. Krista Hessey