The new year begins – as it rarely does – with good news: Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions are believed to have fallen by almost ten percent last year – a good step towards meeting the Paris climate targets. However, a second glance, which Malte Kreutzfeldt and Nico Beckert have risked, shows this: Around half of the decline is not due to successful climate policy, but to last year’s poor economic situation. And that clouds the picture again.

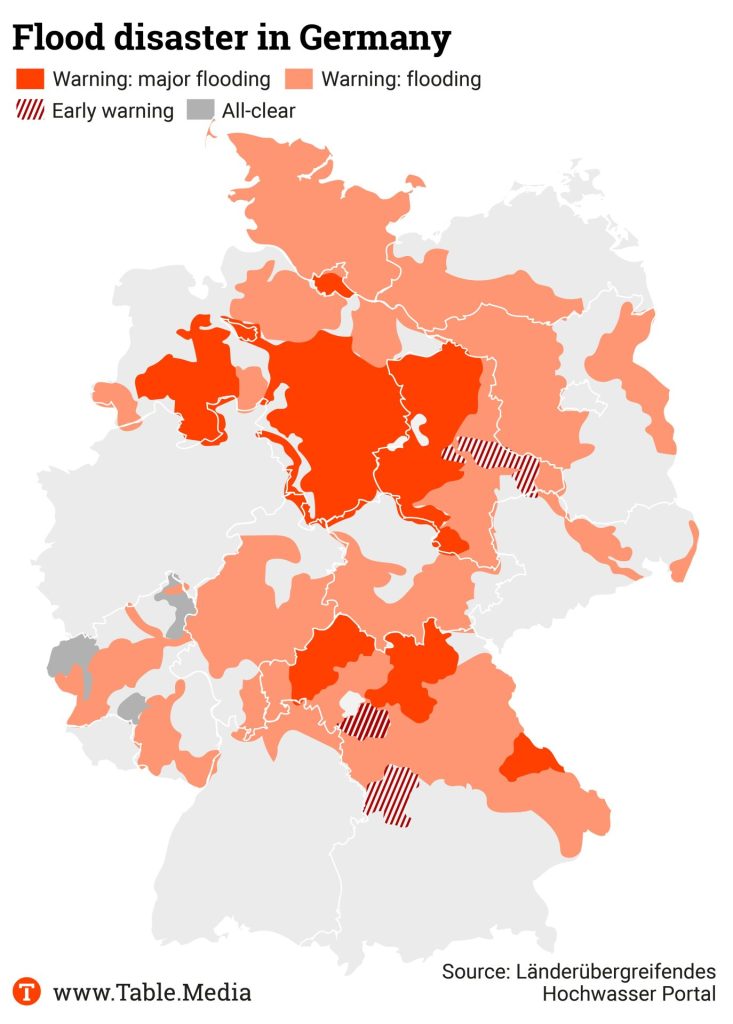

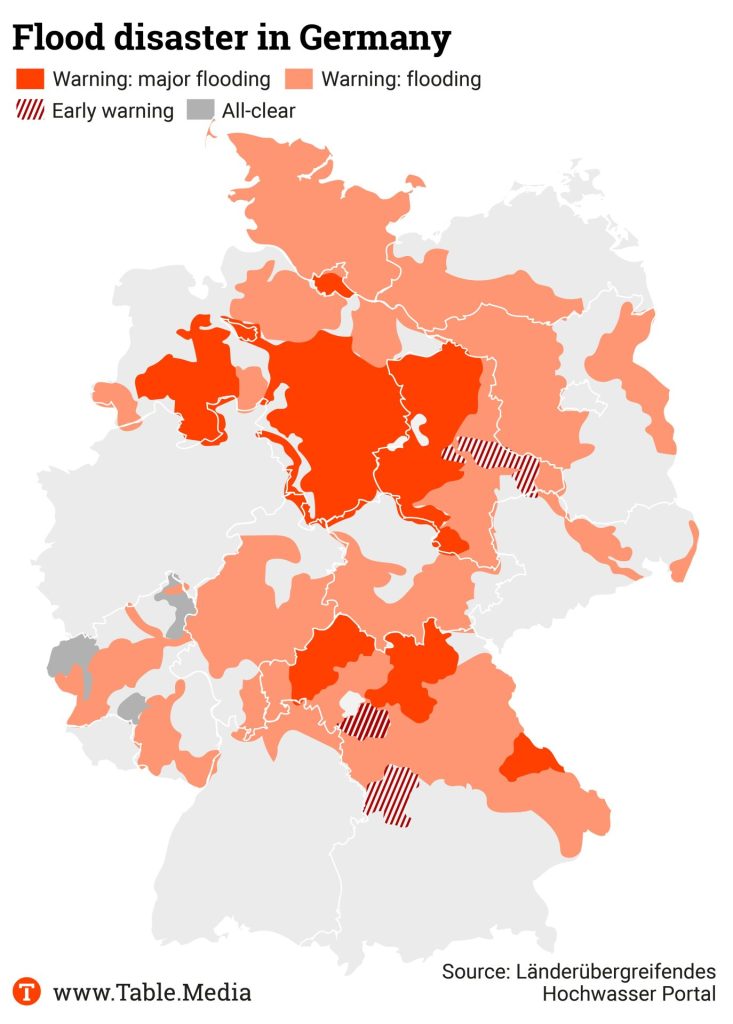

The outlook is also bleak in the flooded regions of northern Germany. Extreme rainfall, global warming and insufficient adaptation measures in recent decades have caused a flood disaster. As surprised as residents, aid workers and politicians are, the situation is by no means surprising for climate researchers, as Alexandra Endres and I found out: The situation is pretty much in line with the scenario that scientists have been warning about for a long time.

These examples show how important and successful a carefully planned and firmly implemented climate policy can be. There will be plenty of opportunities to do so again in 2024– as our outlook on important upcoming laws and decisions shows. We will stay tuned for you.

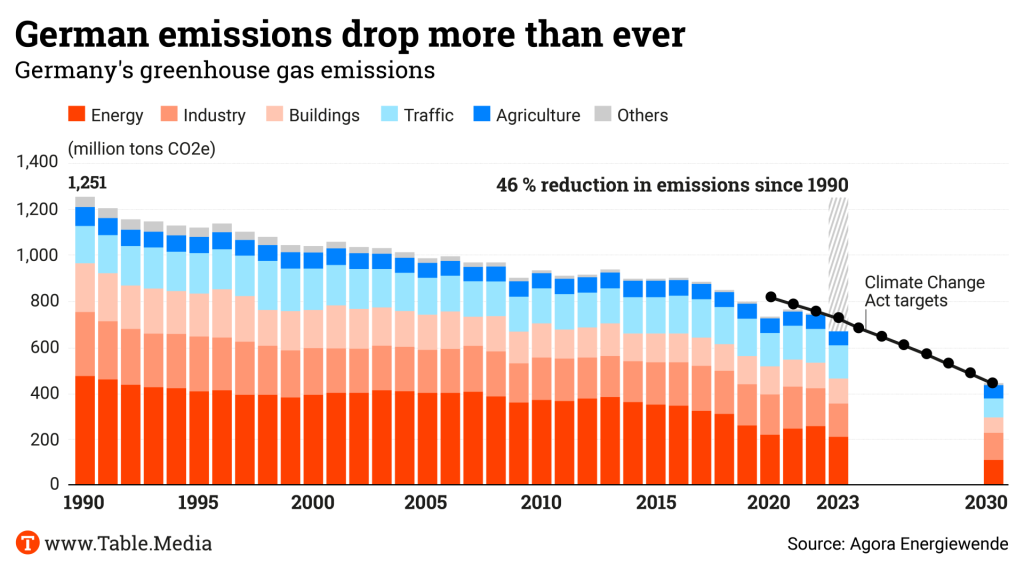

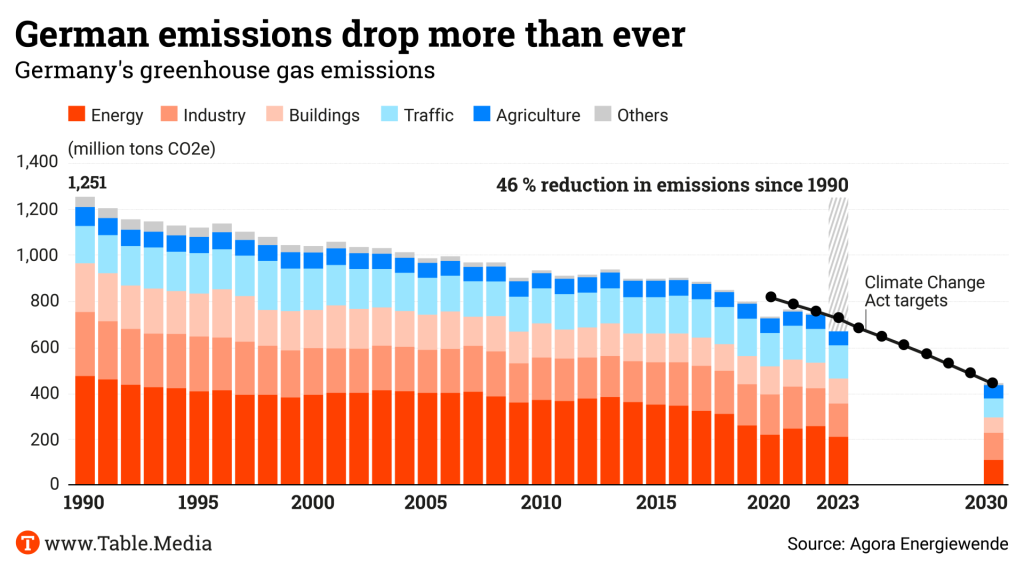

Germany’s carbon emissions fell by around ten percent in 2023 – more than in any year since they were recorded for the whole of Germany. This is revealed by an analysis published today by Agora Energiewende. This is significantly below the 2023 target. However, the think tank writes that there is still a “significant gap” in achieving the climate targets for 2030.

Last year, greenhouse gas emissions amounted to 673 million tons of CO2 equivalents. This is 73 million tons less than in the previous year and 49 million tons less than the target for 2023. Compared to the reference year 1990, the reduction is 46 percent.

However, the reasons for the drop are only partially positive:

While the overall target stipulated in the Climate Change Act for 2023 was achieved, the transport and building sectors again missed their targets. Emissions in the buildings sector decreased by three million tons to 109 million, missing the sector target by eight million. The transport sector saw a decrease of 3 million tons to 145 million tons, which is 12 million more than the target set in the Climate Change Act. Agora warns that Germany will probably have to compensate for this overshoot as early as 2024 by purchasing carbon credits from other EU countries – otherwise, it could face penalties. In the agricultural sector, emissions were 61 million tons and, therefore, six million tons below the target value – however, this was mainly because this target value was not adjusted to the calculation of nitrous oxide emissions, which has changed in the meantime.

“Germany needs an investment offensive to achieve the climate targets” by 2030, said Müller. He demands that public funds be provided for climate-neutral heating systems and the transformation of the industry. Expanding and converting the electricity, heating and hydrogen grids also requires “considerable investment.”

There have been significant shifts in electricity generation due to the combination of renewables expansion and imports. According to an analysis published on Tuesday by the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, around 55 percent of the electricity generated in Germany in 2023 came from renewable energy sources. Wind energy grew strongly, with generation 14 percent higher than the previous year. Photovoltaic systems, on the other hand, only produced 1.4 percent over 2022 due to weather conditions, despite a robust expansion. Around 11 percent of solar power was used directly by private consumers, i.e., was not fed into the grid.

Despite Germany’s exit from nuclear power, coal-fired power generation fell to a new low: At 126 terawatt hours, lignite and hard coal-fired power plants generated almost 30 percent less electricity than in 2022; the last time this figure was lower was in 1959. Nevertheless, the opposition party CDU/CSU sharply criticized the German government. Back in mid-December, CDU deputy leader Andreas Jung told German media that the government was giving Germany “a coal winter.”

This was due to a few low-wind days on which a considerable amount of coal was used to generate electricity. On the other hand, coal consumption in December as a whole was lower than it has been for years. When asked about this contradiction, Jung said that German carbon emissions were nevertheless higher “than they should be” due to the nuclear phase-out. In addition, the absolute figures must be compared to overall electricity consumption, which has fallen due to the economic downturn, he said. However, this does not change much: At 25 percent, coal-fired electricity also played a minor role in percentage terms in December compared to the same month in previous years.

The current flood disaster in northern and central Germany is in line with climate science predictions of possible extreme events in winter – namely in terms of their causes, course, and effects. The climate models predict more frequent heavy rainfall because warmer air absorbs more moisture. As rivers and wetlands are unable to drain or store unusually large volumes of water quickly enough, the likelihood of flooding increases. As climate change adaptation measures have not yet progressed sufficiently, extreme weather-related damage and losses are also increasing in Germany.

Friederike Otto, climatologist at Imperial College London and co-founder of the World Weather Attribution (WWA) research initiative, confirms to Table.Media: “There are no concrete figures yet, but this is clearly a signal of climate change.” Hardly any event has been better studied than winter rain in Northern Europe. “It’s wetter, and it’s getting wetter. This is not a natural disaster, but politics against people, for corporations and their very few profiteers.”

“What we are seeing fits well with the pattern set by the climate models,” says Fred Hattermann, head of the Hydroclimatic Risks working group at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). Extremely warm sea surfaces increase evaporation. The atmosphere worldwide is enriched with significantly more moisture than the average in recent decades. “For every degree Celsius of higher temperatures, the maximum capacity to absorb moisture increases by seven percent,” says Hattermann. In Germany, temperatures are now around two degrees higher than in pre-industrial times.

The precipitation over Saxony-Anhalt and Lower Saxony is determined by evaporation from the Atlantic, which set new heat records last year. “Our weather kitchen is the Atlantic,” says Hattermann. Just as the extremely warm Mediterranean led to drought and heavy rainfall over Southern Europe and North Africa in the summer of 2023 (climate models warned of this in detail), the air masses over Central Europe are now laden with moisture. “The water cycle changes with climate change, which is why old standards that predict ‘floods of the century,’ for instance, no longer apply. This only works in a system that doesn’t change.”

For example, forecasts by the German Weather Service predict generally warmer and wetter winters for Germany. Since 1881/82, winter precipitation has increased by around 25 percent across Germany and even more in some regions such as the north-west. For example, the current climate impact monitoring report by the state of Lower Saxony warns: “In the course of climate change, an increase in extreme rainfall events is expected, with corresponding consequences for flood conditions.” However, previous observations “have not yet shown any significant influence of climate change” on days with flooding, as the report published in November 2023 states a few pages later.

Meteorologist Daniela Jacob, Director of the Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS), which primarily conducts research into practical climate adaptation, says: “We have known for a long time that climate change is leading to more and heavier rainfall in the winter months, which can also be accompanied by repeated flooding. However, the extent of the current flooding is very unusual.” This “clearly shows how important it is to implement protection strategies quickly and comprehensively.”

PIK researcher Hattermann distinguishes between “soft” and “hard” measures to adapt to the new situation. Soft measures include improved weather and flood forecasts and early warnings that are also accepted by the population – for example, when it comes to evacuating towns and villages. Better insurance coverage is also part of this. The “hard” factors, for example, mean strengthening dykes before disasters occur. This also includes mobile protective walls and the creation of polders and flood plains.

According to the Federal Environment Agency (UBA), three aspects, in particular, are essential for effective and sustainable flood protection:

However, in a densely populated industrialized country like Germany, flooding cannot be avoided entirely, says Hattermann: “Our watercourses are too straightened for that.” The UBA also points out that flood waves today are much steeper and higher than in the past “due to soil sealing, river straightening and the cutting off of natural floodplains by embankments.”

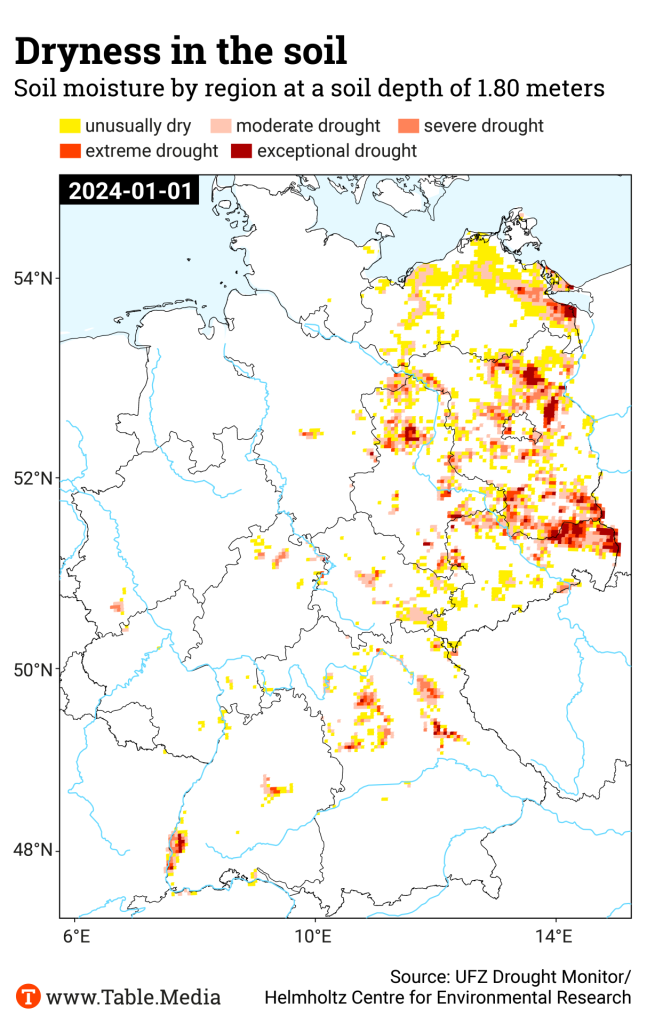

Hattermann says that things also become difficult when several factors come together: For example, a flood and further heavy rainfall over the headwaters of the affected river – or high water in the sea, which dams up the river water all the way inland. Prolonged drought also means hard, dried-out soils can absorb less water.

The Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMUV) also recognizes the need to prepare for future floods. “The current tense flood situation shows how important it is to take flood precautions and invest in preventive flood protection,” a spokesperson wrote in response to a question from Table.Media. The climate crisis will make the challenges even greater in the future, they added.

But in practice, prevention has not yet progressed very far. This is evident, for example, in the National Flood Control Program (NHSWP), jointly developed by the federal and state governments ten years ago following the floods on the Danube and Elbe. The spokesperson says it contains “measures to reduce water levels with a supra-regional effect.” Its “space-creating measures” – for example, flood polders or the relocation of dykes, on which the NHSWP focuses – would, according to the current state of planning, “reclaim a total area of almost 33,000 hectares for natural flood retention and create around one billion cubic meters of new retention volume.”

The BMUV estimates the financial volume of the NHSWP at six billion euros. An additional 500 million euros would be spent on measures such as coastal protection, although this is allocated by the Ministry of Agriculture. In itself, the NHSWP provides for sensible protective measures: For example, in a 2021 study, the UBA concluded that “all supra-regional measures planned by 2020 in the river basins of the Danube, Elbe and Rhine will make a significant contribution to lowering the peaks of floods on the major rivers.”

However, most of these measures have not yet been implemented. Only a tiny proportion of them are actually built. According to the BMUV, of the 168 space-clearing sub- and individual measures of the NHWSP, “around 39 percent are in the concept phase, 27 percent in the preliminary planning phase, 11 percent in the approval or tendering phase for construction and 15 percent in the construction phase”.

“Surely, some damage could have been avoided if more decisive action had been taken,” says adaptation researcher Jacob about the current flooding. The NHSWP plays a very important role in this.

At least Germany has, for the first time since the end of last year, a climate adaptation law. It passed the Bundesrat on December 15, is due to come into force in mid-2024, and will then require federal, state and local authorities to develop strategies and concepts for adapting to the effects of climate change.

There has actually been a “German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change” at the federal level since 2008. It provided a framework. It was followed by reports, analyses and municipal projects – but it did not result in a coherent strategy that regulates climate adaptation in Germany across the various federal levels. Last summer, research by German media even concluded that only a quarter of municipalities had a climate change adaptation strategy.

One problem is financing: Climate action is not a mandatory municipal responsibility. The extent to which a municipality engages in climate action often depends on the political will of mayors or municipal councils. This is why the Conference of Environment Ministers currently discusses reliable funding for climate action and adaptation.

The new Adaptation Act is now set to introduce an overarching strategy for adapting to climate change tailored to local risks. For the first time, it also obliges the German government to present measurable climate adaptation targets. According to the BMUV, the government’s adaptation strategy and targets will be ready by the end of 2024.

From a conceptual perspective, Germany has “done its homework through various overarching policy instruments such as the Flood Protection Program, the Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change, the Climate Action Program and the National Water Strategy,” the UBA said. In the coming years, these concepts, strategies and programs must be implemented quickly, “even in a tight budgetary situation.”

Climate researcher Jacob says: “The consequences of climate change and possibilities for adaptation have been discussed in Germany for around 20 years.” There has also been progress: Information at all spatial levels, climate impact assessments, public and private advisory institutions, and many very good discussions and approaches to adaptation plans. “But plans alone are not enough.”

In many places, it is clear how the weather and climate could change, and there are lists of possible adaptation options. However, the decision to implement the solutions is lacking, even though the knowledge is available. “Extremely long approval processes and a lack of money often hinder implementation. And unfortunately, adapting against the consequences of climate change does not always seem to be at the top of the priority list.”

Date: January 1, 2024

On January 1, 2024, the 2nd amendment to Germany’s Building Energy Act (GEG) and the Heat Planning Act (WPG) came into force. The GEG is a core component of Germany’s heating transition. It lays the legal foundation for the transition to renewable energies and thus, the decarbonization of the heating sector. It will be implemented in stages:

The funding provided by the German government for decarbonizing the heating sector was approved at the end of 2023. However, the funds for 2024 will not be definitively approved until the budget debates in late January.

Date: Beginning of 2024 (budget debate)

The German government abruptly suspended the environmental bonus for the private purchase of new electric vehicles on December 18, 2023. The bonus was supposed to total 4,500 euros from January 1, 2024, for fully electric cars with a net list price of up to 45,000 euros and was actually not due to expire until 2024. The planned federal contribution to the environmental bonus was 3,000 euros, while manufacturers were to contribute 1,500 euros.

The reason for the sudden decision was the ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court on the special funds and the resulting cutbacks in the Climate and Transformation Fund and the 2024 federal budget adopted by the German government.

It remains unclear whether the subsidy will expire completely. In the meantime, the SPD party in the Bundestag has called for follow-up funding for the program. Several manufacturers have now announced that they may be willing to bear the missing share of the government’s environmental bonus themselves.

Date: soon

Germany plans to put climate contracts out to tender for energy-intensive industries impacted by high energy prices but still awaits approval from the EU Commission. These so-called climate contracts, also known as “Carbon Contracts for Difference,” are intended to use public money to hedge the risks of corporate investments in greener technologies and production methods.

Date: Spring/Fall

The reform and financial resources of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) will continue to keep international policymakers busy. The Bank has set itself the goal of facilitating more green investment. The debt crisis will remain an important issue, particularly at the IMF. Many developing countries have no money to finance the energy transition. The World Bank has already taken initial steps to free up funds – but its head, Ajay Banga, has made it clear that the institution urgently needs more capital for this. The World Bank and IMF’s spring meeting in 2024 and the annual meeting in the fall will likely discuss where the funds could come from.

Date: mid-2024

The Federal Climate Change Adaptation Act (KAnG) was passed at the end of 2023. It is set to come into force in mid-2024. With this law, Germany provides a common framework for climate adaptation at federal, state and local levels. The aim is to ensure that climate adaptation concepts are developed at all federal levels in Germany and comprehensive climate mitigation measures are taken.

Date: End of October 2024

The “other COP” is likely to take place in Colombia at the end of October: COP16 on biodiversity. Following the success of the 2022 agreement in Montréal, the next step is to determine how its implementation progresses and how the links to the climate process – for example, the conservation of forests, peatlands and oceans – can be strengthened.

Date: November 2024

Climate financing could become one of the hottest topics this year. If the OECD’s preliminary forecast is correct, developed countries will reach the 100 billion US dollars in financial aid for developing countries that were promised for 2022 two years later. That would be an excellent start to COP29 in November. A decision on how climate financing will continue after 2025 is expected to be made in Azerbaijan.

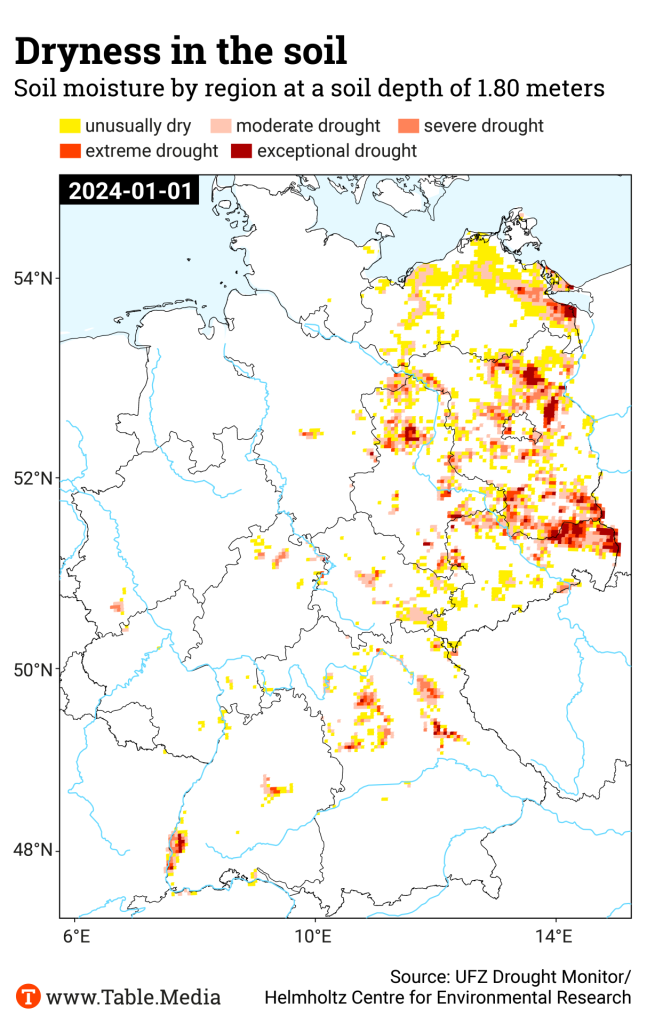

At a time when large parts of northern Germany are flooded, this data is surprising: But according to data from the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research UFZ’s “Drought Monitor,” the soil 1.80 meters below the surface is actually still dry to the point of extreme drought in large parts of Germany. In eastern and northeastern parts of the country, in particular, the deep soil still stores far too little water despite heavy rainfall in recent weeks.

This results from the last few years, which have seen significantly less precipitation in these regions than the long-term average. So, while the water requirements of agriculture just below the surface are currently being well met, deep-rooted trees continue to face a problem. The recovery and regeneration of groundwater are also affected by the lack of water at depth. bpo

In the UK, fossil-fueled electricity production fell by 22 percent last year compared to 2022. Only 104 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity were produced from coal, oil and gas – the lowest figure in 66 years, as reported by Carbon Brief. In 2008, electricity production from fossil sources was still around 300 TWh. Since then, renewables have increased six-fold and electricity demand has fallen by 21 percent. The electricity mix in 2023 was as follows:

The government has set a target of covering around 95 percent of electricity from low-carbon sources by 2030. According to Bloomberg, electricity production from nuclear power also fell to a 42-year low. One reactor was shut down, while others were partially offline for maintenance. The government plans to add 24 gigawatts of nuclear capacity by the middle of the millennium, with costs estimated at 190 billion US dollars. nib

The unusual drought in the Amazon region continues, even though the rainy season should have started in December. This heightens concerns that the ecosystem could reach a tipping point as a result of heat, drought and deforestation, beyond which it would be irreversibly altered. The region’s rain cycle could collapse. The consequences would also affect Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. The rainforest would turn into a savannah.

The impact on the global climate would be severe. According to a scientific overview report from 2021, the soils and plants of the rainforest store around 150 to 200 billion tons of carbon. That is the equivalent of around 550 to 734 billion tons of CO2. A considerable proportion of this would gradually be released once a tipping point is passed.

Science has long been discussing the danger. Just last October, a study published in Science Advances provided new indications that the critical point could soon be reached. However, it remains unclear when exactly the rainforest will pass a tipping point. Researchers also debate whether the entire rainforest may become a savannah or whether there are different regional tipping points.

The Science Media Center Germany has compiled opinions from researchers on the debate. A selection:

Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon region has recently decreased significantly, as has deforestation in neighboring Colombia. However, the pressure on the forest remains high: In Brazil, for instance, due to infrastructure projects, restricted land rights for the indigenous population and, in general, the balance of power in Congress. The think tank Insight Crime warns that political instability and illegal activities in the countries of the Amazon region are also endangering the forest. ae

The German Emissions Trading Authority (DEHSt) is reportedly examining allegations of irregularities in a biodiesel project in China. German biofuel manufacturers had previously criticized that Upstream Emission Reduction Certificates (UER) issued by DEHSt to some international companies for their emission reduction projects in China were allegedly based on false information.

UER certificates are granted for low-emission production of biofuels, such as the use of renewable energy. There is now an investigation into a project in China, as reported by Nikkei Asia on Wednesday. The DEHSt has not yet disclosed the specific project under investigation, according to the report.

Allegations of fraud concerning biodiesel from China have been ongoing for some time. The European Commission also initiated an investigation in late December. German manufacturers and producers from other European countries accuse Chinese manufacturers of deception: Chinese companies are alleged to purchase biodiesel containing palm oil from other Asian countries, relabel it and sell it to Europe. In Germany, for example, the use of palm oil in biodiesel is no longer allowed. The European Commission is also investigating the biodiesel business from China for dumping prices. ari

Even as a young boy, Nick Nuttall dreamed of a career as a musician. However, it wasn’t until the summer of 2023 that his first solo album was released. What happened in between: his equally strong enthusiasm for climate and environmental issues. Nuttall worked for several decades as an environmental correspondent for The Times and head of press at the UNFCCC and the UN Environment Program (UNEP). “Just Because Some Bad Wind Blows” is the title of his album. It’s about the climate, he explains, even if the term is deliberately left out: He didn’t want to produce a cheesy song about saving the world, but he didn’t want to produce something hopeless either.

Nick Nuttall was born and raised in Rochdale in northern England. His whole family was musical, but his father was not convinced by the idea of becoming a pop star. So Nuttall enrolled at university and studied marine biology because of the nature documentaries he loved watching on TV. “I spent the first twelve months dissecting fish,” says Nuttall. He switched to studying psychology. After graduating, he came to the US city of Denver on an exchange program, where he founded a new band and landed his first “mini-hit.” Then, the oil crisis hit.

“Suddenly, the Americans were importing tiny, fuel-efficient cars,” says Nick Nuttall, laughing. “That’s what happens when CO2 gets a price.” However, he, too, experienced turbulent economic times. His band’s second album flopped. He briefly worked as a stockbroker to pay off the debts. However, he didn’t enjoy the job: “I felt like I was in a casino.” He was all the more relieved when he was offered the opportunity to write for a financial newsletter. At the end of the 1980s, he became a writer for “The Times,” where he was first a science and then environment correspondent – “a stroke of luck” for Nuttall.

He was in the right place at the right time when environmental policy left its niche. Nuttall reported on the first World Climate Conference in 1995 and the Kyoto Protocol two years later. One day, his phone rang in the newsroom, and it was Klaus Töpfer. The former German environment minister was head of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) at the time. “I was late with a text and hung up quickly,” recalls Nuttall. Töpfer wanted to offer him a job. However, in the end, they found each other and the Brit became his press spokesman in 2001. Over the next few years, Nuttall traveled the world for the UN program, organized the annual World Environment Day, and learned a lot.

“It’s really fascinating how each country finds different solutions to its climate and environmental challenges,” says Nick Nuttall. The change of perspective from the program’s base in Nairobi was incredibly educational. A few years later, he moved to the UN Climate Change Secretariat in Bonn and became its spokesperson. Nuttall describes his communication strategy as follows: “You shouldn’t make people afraid of losing something. There is a lot to gain, such as clean air.” The search for a positive climate narrative continues to drive the 65-year-old. He currently works for the climate action platform “We don’t have time” and finally finds more time to make music. Paul Meerkamp

The new year begins – as it rarely does – with good news: Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions are believed to have fallen by almost ten percent last year – a good step towards meeting the Paris climate targets. However, a second glance, which Malte Kreutzfeldt and Nico Beckert have risked, shows this: Around half of the decline is not due to successful climate policy, but to last year’s poor economic situation. And that clouds the picture again.

The outlook is also bleak in the flooded regions of northern Germany. Extreme rainfall, global warming and insufficient adaptation measures in recent decades have caused a flood disaster. As surprised as residents, aid workers and politicians are, the situation is by no means surprising for climate researchers, as Alexandra Endres and I found out: The situation is pretty much in line with the scenario that scientists have been warning about for a long time.

These examples show how important and successful a carefully planned and firmly implemented climate policy can be. There will be plenty of opportunities to do so again in 2024– as our outlook on important upcoming laws and decisions shows. We will stay tuned for you.

Germany’s carbon emissions fell by around ten percent in 2023 – more than in any year since they were recorded for the whole of Germany. This is revealed by an analysis published today by Agora Energiewende. This is significantly below the 2023 target. However, the think tank writes that there is still a “significant gap” in achieving the climate targets for 2030.

Last year, greenhouse gas emissions amounted to 673 million tons of CO2 equivalents. This is 73 million tons less than in the previous year and 49 million tons less than the target for 2023. Compared to the reference year 1990, the reduction is 46 percent.

However, the reasons for the drop are only partially positive:

While the overall target stipulated in the Climate Change Act for 2023 was achieved, the transport and building sectors again missed their targets. Emissions in the buildings sector decreased by three million tons to 109 million, missing the sector target by eight million. The transport sector saw a decrease of 3 million tons to 145 million tons, which is 12 million more than the target set in the Climate Change Act. Agora warns that Germany will probably have to compensate for this overshoot as early as 2024 by purchasing carbon credits from other EU countries – otherwise, it could face penalties. In the agricultural sector, emissions were 61 million tons and, therefore, six million tons below the target value – however, this was mainly because this target value was not adjusted to the calculation of nitrous oxide emissions, which has changed in the meantime.

“Germany needs an investment offensive to achieve the climate targets” by 2030, said Müller. He demands that public funds be provided for climate-neutral heating systems and the transformation of the industry. Expanding and converting the electricity, heating and hydrogen grids also requires “considerable investment.”

There have been significant shifts in electricity generation due to the combination of renewables expansion and imports. According to an analysis published on Tuesday by the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, around 55 percent of the electricity generated in Germany in 2023 came from renewable energy sources. Wind energy grew strongly, with generation 14 percent higher than the previous year. Photovoltaic systems, on the other hand, only produced 1.4 percent over 2022 due to weather conditions, despite a robust expansion. Around 11 percent of solar power was used directly by private consumers, i.e., was not fed into the grid.

Despite Germany’s exit from nuclear power, coal-fired power generation fell to a new low: At 126 terawatt hours, lignite and hard coal-fired power plants generated almost 30 percent less electricity than in 2022; the last time this figure was lower was in 1959. Nevertheless, the opposition party CDU/CSU sharply criticized the German government. Back in mid-December, CDU deputy leader Andreas Jung told German media that the government was giving Germany “a coal winter.”

This was due to a few low-wind days on which a considerable amount of coal was used to generate electricity. On the other hand, coal consumption in December as a whole was lower than it has been for years. When asked about this contradiction, Jung said that German carbon emissions were nevertheless higher “than they should be” due to the nuclear phase-out. In addition, the absolute figures must be compared to overall electricity consumption, which has fallen due to the economic downturn, he said. However, this does not change much: At 25 percent, coal-fired electricity also played a minor role in percentage terms in December compared to the same month in previous years.

The current flood disaster in northern and central Germany is in line with climate science predictions of possible extreme events in winter – namely in terms of their causes, course, and effects. The climate models predict more frequent heavy rainfall because warmer air absorbs more moisture. As rivers and wetlands are unable to drain or store unusually large volumes of water quickly enough, the likelihood of flooding increases. As climate change adaptation measures have not yet progressed sufficiently, extreme weather-related damage and losses are also increasing in Germany.

Friederike Otto, climatologist at Imperial College London and co-founder of the World Weather Attribution (WWA) research initiative, confirms to Table.Media: “There are no concrete figures yet, but this is clearly a signal of climate change.” Hardly any event has been better studied than winter rain in Northern Europe. “It’s wetter, and it’s getting wetter. This is not a natural disaster, but politics against people, for corporations and their very few profiteers.”

“What we are seeing fits well with the pattern set by the climate models,” says Fred Hattermann, head of the Hydroclimatic Risks working group at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). Extremely warm sea surfaces increase evaporation. The atmosphere worldwide is enriched with significantly more moisture than the average in recent decades. “For every degree Celsius of higher temperatures, the maximum capacity to absorb moisture increases by seven percent,” says Hattermann. In Germany, temperatures are now around two degrees higher than in pre-industrial times.

The precipitation over Saxony-Anhalt and Lower Saxony is determined by evaporation from the Atlantic, which set new heat records last year. “Our weather kitchen is the Atlantic,” says Hattermann. Just as the extremely warm Mediterranean led to drought and heavy rainfall over Southern Europe and North Africa in the summer of 2023 (climate models warned of this in detail), the air masses over Central Europe are now laden with moisture. “The water cycle changes with climate change, which is why old standards that predict ‘floods of the century,’ for instance, no longer apply. This only works in a system that doesn’t change.”

For example, forecasts by the German Weather Service predict generally warmer and wetter winters for Germany. Since 1881/82, winter precipitation has increased by around 25 percent across Germany and even more in some regions such as the north-west. For example, the current climate impact monitoring report by the state of Lower Saxony warns: “In the course of climate change, an increase in extreme rainfall events is expected, with corresponding consequences for flood conditions.” However, previous observations “have not yet shown any significant influence of climate change” on days with flooding, as the report published in November 2023 states a few pages later.

Meteorologist Daniela Jacob, Director of the Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS), which primarily conducts research into practical climate adaptation, says: “We have known for a long time that climate change is leading to more and heavier rainfall in the winter months, which can also be accompanied by repeated flooding. However, the extent of the current flooding is very unusual.” This “clearly shows how important it is to implement protection strategies quickly and comprehensively.”

PIK researcher Hattermann distinguishes between “soft” and “hard” measures to adapt to the new situation. Soft measures include improved weather and flood forecasts and early warnings that are also accepted by the population – for example, when it comes to evacuating towns and villages. Better insurance coverage is also part of this. The “hard” factors, for example, mean strengthening dykes before disasters occur. This also includes mobile protective walls and the creation of polders and flood plains.

According to the Federal Environment Agency (UBA), three aspects, in particular, are essential for effective and sustainable flood protection:

However, in a densely populated industrialized country like Germany, flooding cannot be avoided entirely, says Hattermann: “Our watercourses are too straightened for that.” The UBA also points out that flood waves today are much steeper and higher than in the past “due to soil sealing, river straightening and the cutting off of natural floodplains by embankments.”

Hattermann says that things also become difficult when several factors come together: For example, a flood and further heavy rainfall over the headwaters of the affected river – or high water in the sea, which dams up the river water all the way inland. Prolonged drought also means hard, dried-out soils can absorb less water.

The Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMUV) also recognizes the need to prepare for future floods. “The current tense flood situation shows how important it is to take flood precautions and invest in preventive flood protection,” a spokesperson wrote in response to a question from Table.Media. The climate crisis will make the challenges even greater in the future, they added.

But in practice, prevention has not yet progressed very far. This is evident, for example, in the National Flood Control Program (NHSWP), jointly developed by the federal and state governments ten years ago following the floods on the Danube and Elbe. The spokesperson says it contains “measures to reduce water levels with a supra-regional effect.” Its “space-creating measures” – for example, flood polders or the relocation of dykes, on which the NHSWP focuses – would, according to the current state of planning, “reclaim a total area of almost 33,000 hectares for natural flood retention and create around one billion cubic meters of new retention volume.”

The BMUV estimates the financial volume of the NHSWP at six billion euros. An additional 500 million euros would be spent on measures such as coastal protection, although this is allocated by the Ministry of Agriculture. In itself, the NHSWP provides for sensible protective measures: For example, in a 2021 study, the UBA concluded that “all supra-regional measures planned by 2020 in the river basins of the Danube, Elbe and Rhine will make a significant contribution to lowering the peaks of floods on the major rivers.”

However, most of these measures have not yet been implemented. Only a tiny proportion of them are actually built. According to the BMUV, of the 168 space-clearing sub- and individual measures of the NHWSP, “around 39 percent are in the concept phase, 27 percent in the preliminary planning phase, 11 percent in the approval or tendering phase for construction and 15 percent in the construction phase”.

“Surely, some damage could have been avoided if more decisive action had been taken,” says adaptation researcher Jacob about the current flooding. The NHSWP plays a very important role in this.

At least Germany has, for the first time since the end of last year, a climate adaptation law. It passed the Bundesrat on December 15, is due to come into force in mid-2024, and will then require federal, state and local authorities to develop strategies and concepts for adapting to the effects of climate change.

There has actually been a “German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change” at the federal level since 2008. It provided a framework. It was followed by reports, analyses and municipal projects – but it did not result in a coherent strategy that regulates climate adaptation in Germany across the various federal levels. Last summer, research by German media even concluded that only a quarter of municipalities had a climate change adaptation strategy.

One problem is financing: Climate action is not a mandatory municipal responsibility. The extent to which a municipality engages in climate action often depends on the political will of mayors or municipal councils. This is why the Conference of Environment Ministers currently discusses reliable funding for climate action and adaptation.

The new Adaptation Act is now set to introduce an overarching strategy for adapting to climate change tailored to local risks. For the first time, it also obliges the German government to present measurable climate adaptation targets. According to the BMUV, the government’s adaptation strategy and targets will be ready by the end of 2024.

From a conceptual perspective, Germany has “done its homework through various overarching policy instruments such as the Flood Protection Program, the Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change, the Climate Action Program and the National Water Strategy,” the UBA said. In the coming years, these concepts, strategies and programs must be implemented quickly, “even in a tight budgetary situation.”

Climate researcher Jacob says: “The consequences of climate change and possibilities for adaptation have been discussed in Germany for around 20 years.” There has also been progress: Information at all spatial levels, climate impact assessments, public and private advisory institutions, and many very good discussions and approaches to adaptation plans. “But plans alone are not enough.”

In many places, it is clear how the weather and climate could change, and there are lists of possible adaptation options. However, the decision to implement the solutions is lacking, even though the knowledge is available. “Extremely long approval processes and a lack of money often hinder implementation. And unfortunately, adapting against the consequences of climate change does not always seem to be at the top of the priority list.”

Date: January 1, 2024

On January 1, 2024, the 2nd amendment to Germany’s Building Energy Act (GEG) and the Heat Planning Act (WPG) came into force. The GEG is a core component of Germany’s heating transition. It lays the legal foundation for the transition to renewable energies and thus, the decarbonization of the heating sector. It will be implemented in stages:

The funding provided by the German government for decarbonizing the heating sector was approved at the end of 2023. However, the funds for 2024 will not be definitively approved until the budget debates in late January.

Date: Beginning of 2024 (budget debate)

The German government abruptly suspended the environmental bonus for the private purchase of new electric vehicles on December 18, 2023. The bonus was supposed to total 4,500 euros from January 1, 2024, for fully electric cars with a net list price of up to 45,000 euros and was actually not due to expire until 2024. The planned federal contribution to the environmental bonus was 3,000 euros, while manufacturers were to contribute 1,500 euros.

The reason for the sudden decision was the ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court on the special funds and the resulting cutbacks in the Climate and Transformation Fund and the 2024 federal budget adopted by the German government.

It remains unclear whether the subsidy will expire completely. In the meantime, the SPD party in the Bundestag has called for follow-up funding for the program. Several manufacturers have now announced that they may be willing to bear the missing share of the government’s environmental bonus themselves.

Date: soon

Germany plans to put climate contracts out to tender for energy-intensive industries impacted by high energy prices but still awaits approval from the EU Commission. These so-called climate contracts, also known as “Carbon Contracts for Difference,” are intended to use public money to hedge the risks of corporate investments in greener technologies and production methods.

Date: Spring/Fall

The reform and financial resources of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) will continue to keep international policymakers busy. The Bank has set itself the goal of facilitating more green investment. The debt crisis will remain an important issue, particularly at the IMF. Many developing countries have no money to finance the energy transition. The World Bank has already taken initial steps to free up funds – but its head, Ajay Banga, has made it clear that the institution urgently needs more capital for this. The World Bank and IMF’s spring meeting in 2024 and the annual meeting in the fall will likely discuss where the funds could come from.

Date: mid-2024

The Federal Climate Change Adaptation Act (KAnG) was passed at the end of 2023. It is set to come into force in mid-2024. With this law, Germany provides a common framework for climate adaptation at federal, state and local levels. The aim is to ensure that climate adaptation concepts are developed at all federal levels in Germany and comprehensive climate mitigation measures are taken.

Date: End of October 2024

The “other COP” is likely to take place in Colombia at the end of October: COP16 on biodiversity. Following the success of the 2022 agreement in Montréal, the next step is to determine how its implementation progresses and how the links to the climate process – for example, the conservation of forests, peatlands and oceans – can be strengthened.

Date: November 2024

Climate financing could become one of the hottest topics this year. If the OECD’s preliminary forecast is correct, developed countries will reach the 100 billion US dollars in financial aid for developing countries that were promised for 2022 two years later. That would be an excellent start to COP29 in November. A decision on how climate financing will continue after 2025 is expected to be made in Azerbaijan.

At a time when large parts of northern Germany are flooded, this data is surprising: But according to data from the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research UFZ’s “Drought Monitor,” the soil 1.80 meters below the surface is actually still dry to the point of extreme drought in large parts of Germany. In eastern and northeastern parts of the country, in particular, the deep soil still stores far too little water despite heavy rainfall in recent weeks.

This results from the last few years, which have seen significantly less precipitation in these regions than the long-term average. So, while the water requirements of agriculture just below the surface are currently being well met, deep-rooted trees continue to face a problem. The recovery and regeneration of groundwater are also affected by the lack of water at depth. bpo

In the UK, fossil-fueled electricity production fell by 22 percent last year compared to 2022. Only 104 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity were produced from coal, oil and gas – the lowest figure in 66 years, as reported by Carbon Brief. In 2008, electricity production from fossil sources was still around 300 TWh. Since then, renewables have increased six-fold and electricity demand has fallen by 21 percent. The electricity mix in 2023 was as follows:

The government has set a target of covering around 95 percent of electricity from low-carbon sources by 2030. According to Bloomberg, electricity production from nuclear power also fell to a 42-year low. One reactor was shut down, while others were partially offline for maintenance. The government plans to add 24 gigawatts of nuclear capacity by the middle of the millennium, with costs estimated at 190 billion US dollars. nib

The unusual drought in the Amazon region continues, even though the rainy season should have started in December. This heightens concerns that the ecosystem could reach a tipping point as a result of heat, drought and deforestation, beyond which it would be irreversibly altered. The region’s rain cycle could collapse. The consequences would also affect Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. The rainforest would turn into a savannah.

The impact on the global climate would be severe. According to a scientific overview report from 2021, the soils and plants of the rainforest store around 150 to 200 billion tons of carbon. That is the equivalent of around 550 to 734 billion tons of CO2. A considerable proportion of this would gradually be released once a tipping point is passed.

Science has long been discussing the danger. Just last October, a study published in Science Advances provided new indications that the critical point could soon be reached. However, it remains unclear when exactly the rainforest will pass a tipping point. Researchers also debate whether the entire rainforest may become a savannah or whether there are different regional tipping points.

The Science Media Center Germany has compiled opinions from researchers on the debate. A selection:

Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon region has recently decreased significantly, as has deforestation in neighboring Colombia. However, the pressure on the forest remains high: In Brazil, for instance, due to infrastructure projects, restricted land rights for the indigenous population and, in general, the balance of power in Congress. The think tank Insight Crime warns that political instability and illegal activities in the countries of the Amazon region are also endangering the forest. ae

The German Emissions Trading Authority (DEHSt) is reportedly examining allegations of irregularities in a biodiesel project in China. German biofuel manufacturers had previously criticized that Upstream Emission Reduction Certificates (UER) issued by DEHSt to some international companies for their emission reduction projects in China were allegedly based on false information.

UER certificates are granted for low-emission production of biofuels, such as the use of renewable energy. There is now an investigation into a project in China, as reported by Nikkei Asia on Wednesday. The DEHSt has not yet disclosed the specific project under investigation, according to the report.

Allegations of fraud concerning biodiesel from China have been ongoing for some time. The European Commission also initiated an investigation in late December. German manufacturers and producers from other European countries accuse Chinese manufacturers of deception: Chinese companies are alleged to purchase biodiesel containing palm oil from other Asian countries, relabel it and sell it to Europe. In Germany, for example, the use of palm oil in biodiesel is no longer allowed. The European Commission is also investigating the biodiesel business from China for dumping prices. ari

Even as a young boy, Nick Nuttall dreamed of a career as a musician. However, it wasn’t until the summer of 2023 that his first solo album was released. What happened in between: his equally strong enthusiasm for climate and environmental issues. Nuttall worked for several decades as an environmental correspondent for The Times and head of press at the UNFCCC and the UN Environment Program (UNEP). “Just Because Some Bad Wind Blows” is the title of his album. It’s about the climate, he explains, even if the term is deliberately left out: He didn’t want to produce a cheesy song about saving the world, but he didn’t want to produce something hopeless either.

Nick Nuttall was born and raised in Rochdale in northern England. His whole family was musical, but his father was not convinced by the idea of becoming a pop star. So Nuttall enrolled at university and studied marine biology because of the nature documentaries he loved watching on TV. “I spent the first twelve months dissecting fish,” says Nuttall. He switched to studying psychology. After graduating, he came to the US city of Denver on an exchange program, where he founded a new band and landed his first “mini-hit.” Then, the oil crisis hit.

“Suddenly, the Americans were importing tiny, fuel-efficient cars,” says Nick Nuttall, laughing. “That’s what happens when CO2 gets a price.” However, he, too, experienced turbulent economic times. His band’s second album flopped. He briefly worked as a stockbroker to pay off the debts. However, he didn’t enjoy the job: “I felt like I was in a casino.” He was all the more relieved when he was offered the opportunity to write for a financial newsletter. At the end of the 1980s, he became a writer for “The Times,” where he was first a science and then environment correspondent – “a stroke of luck” for Nuttall.

He was in the right place at the right time when environmental policy left its niche. Nuttall reported on the first World Climate Conference in 1995 and the Kyoto Protocol two years later. One day, his phone rang in the newsroom, and it was Klaus Töpfer. The former German environment minister was head of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) at the time. “I was late with a text and hung up quickly,” recalls Nuttall. Töpfer wanted to offer him a job. However, in the end, they found each other and the Brit became his press spokesman in 2001. Over the next few years, Nuttall traveled the world for the UN program, organized the annual World Environment Day, and learned a lot.

“It’s really fascinating how each country finds different solutions to its climate and environmental challenges,” says Nick Nuttall. The change of perspective from the program’s base in Nairobi was incredibly educational. A few years later, he moved to the UN Climate Change Secretariat in Bonn and became its spokesperson. Nuttall describes his communication strategy as follows: “You shouldn’t make people afraid of losing something. There is a lot to gain, such as clean air.” The search for a positive climate narrative continues to drive the 65-year-old. He currently works for the climate action platform “We don’t have time” and finally finds more time to make music. Paul Meerkamp