This is what happens when no one is really paying attention: At a meeting in Brussels in March, the EU Council of Ministers decided, among many other issues, on a new climate policy course: Instead of continuing to call for ending all fossil fuels without any ifs and buts, they now say: If the as-yet unproven technology of CO2 capture (CCS) is used for this purpose, that would also be okay. So maybe fossil fuels still have a future in a climate-neutral EU.

The next COP President Sultan Al-Jaber from the United Arab Emirates takes the same position. However, he receives criticism everywhere for it, while the Europeans get away with it so far. As soon as we discovered this, we quickly needed to write it down. This is another thing that climate conferences are useful for, as we have been noticing with our team in Bonn for a week now.

There are also exciting developments elsewhere: For example, the quiet revolution at the World Meteorological Organisation WMO: Instead of relying on insufficient data from many countries like in the past, measurements on greenhouse gases are now to be organized globally. And Ukraine is now calling for Russia’s expulsion from the UN for eco-terrorism after the destruction of the Kharkhova dam – as a high-ranking delegation member in Bonn tells us in an interview.

We are also in our second week at the climate conference in Bonn. And will continue to stay on it.

The European Union has committed in principle to the same course as the COP presidency from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and other oil states on a controversial issue at the next COP28: To use the controversial CCS technology as a loophole in the phase-out of fossil fuels. The EU now seeks a decision at COP28 that would allow this formulation. This became apparent on the sidelines of the Bonn Climate Change Conference. Irrespective of this, a new assessment by the think tank project “Climate Action Tracker” calls the EU’s climate policy “insufficient.”

On the path to climate neutrality, it will be possible to capture and store emissions not only from industrial processes but also from the energy sector, according to a decision by the EU Council of Ministers back in March. Up to now, the Europeans had rejected the use of CCS for the energy sector and, for example, demanded “a phase-down of fossil energies” at COP27 without mentioning CCS. The European position now only calls for an “energy system free of unabated fossil fuels.”

This decision, which has been barely known to the public, is not only a rapprochement with oil and gas producing countries such as the UAE or the United States. It also contradicts the German position. At the Petersberg Climate Dialogue, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock had clearly stated her disagreement with the next COP President, Sultan Ahmed Al-Jaber, on this point: “We have to get out of fossil fuels,” she said – while Al-Jaber stressed that the world has to come to terms with the realities. “Fossil fuels will continue to play a role.” The goal, he said, should be to “phase out emissions.”

State Secretary Jennifer Morgan also said she did not believe “CCS would get us there.” And Robert Habeck’s Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action is working on a German CCS management strategy whose clear stipulation is: CCS only for process emissions from the industrial sector – not as a way out for fossil fuels in the energy sector.

However, the new EU position now leaves this possibility open. An “energy system free of unabated fossil fuels” potentially also includes the application of CCS technology in electricity generation and for combustion in industry. The resolution is a little more concrete than Al-Jaber’s “phasing out emissions,” as it refers to an IPCC definition of “unabated fossil fuels” and a fossil peak well before 2050. Al-Jaber, on the other hand, used the EU term of an energy system “free of unabated fossil fuels” in a speech at the Bonn conference.

The EU Commission is aware that the decision gives fossil fuels the right to exist as fuels even in a climate-neutral EU. In any case, the plan is that even with the EU’s net-zero target, emissions from industry or agriculture will still be stored in nature or through CCS. In the debates for an opening to “unabated fuels,” countries such as Poland and Denmark, in particular, have exerted pressure, according to negotiating circles.

The EU’s change of course makes a compromise on this controversial issue at COP28 more likely. Many other influential countries whose economies still rely heavily on fossil fuels are openly or in secret striving for this goal: The oil states, the United States, but also China or European countries like Norway and Denmark, which are already working on CCS projects.

For the Climate Action Tracker (CAT) scientists, however, CCS is a “dangerous distraction.” CCS should not be used to reduce emissions in the energy sector because “far cheaper renewables are available,” says Claire Stockwell of the CAT project organization Climate Analytics. In its recent report mid-way to COP28, the EU does not score well either: Its continued investment in new fossil fuel infrastructure, especially LNG terminals and gas pipelines, “undermines the EU’s decarbonization efforts,” it says. CAT rates the EU’s climate policy as a whole as “insufficient” also because the EU has not yet raised its climate target (NDC) submitted to the UN as promised.

Generally, the main arguments of CCS critics are that the technology is more expensive than renewables, has not been tested on a large scale worldwide, and is too late to achieve the necessary 50% reduction in global emissions by 2030. But Alden Meyer, a climate expert at the think tank E3G, hopes that a possible COP28 declaration on the fossil flue end will at least define sectoral targets with the help of CCS: Then the addition of “unabated” would not be so problematic, says Meyer. Because then it would be clear that only the few sectors that are difficult to decarbonize could resort to technologies such as CCS.

Moreover, the EU would then have to assess the potential of CCS realistically, Meyer said. “If you recognize that CCS can prevent maybe only five percent of emissions, then it would be clear that the phase-down would be 95 fossil fuels of any kind.” In any case, the UAE, a strong proponent of CCS, plans to store only 2 percent of its emissions this way by 2030, according to CAT.

Meyer, therefore, demands that the EU clarify the role it attributes to CCS for the envisaged phase-down. But for this, a generally accepted definition of what counts as “abated fuel” is first needed. Last week, the Commission launched a public consultation on CCS to examine what role CCS can play in decarbonization by 2030, 2040 and 2050.

Experts from the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) also call for a debate on this issue. They note that CCS is being discussed in countries with high exports of fossil fuels as a means of safeguarding fossil fuel business models to ease the pressure to abandon fossil fuels. They assume that the overall potential of the technology is limited: By 2050, a total of 550 million tons of CO2 could be stored in the EU. Worldwide, the International Energy Agency (IEA) expects just over 5 billion tons in 2050.

What are the economic and ecological results of the disaster at the Kakhovka Dam?

This is a case of ecocide. President Zelenskyy was on Thursday in the region of flooding and the nearby regions, and he had a virtual meeting from Kryvyi Rih city with representatives of the global environmental protection community, including the Vice President from the EU Parliament, activist Greta Thunberg and others. He asked them to label this as ecocide. The region flooded is one of the biggest industrial and agricultural centers in Europe. There are many storage houses for chemicals and fertilizer in the Kherson oblast, also there is a lot of mining, and the biggest steel plant in Ukraine nearby this area in the Kryvyi Rih region. All of their dangerous materials are in the water now, and all of that will go into the Black Sea. It is an international disaster and an act of eco-terrorism by Russia.

How dangerous is the flooding?

The water reservoir at Kakhovka Dam is known as the “Kakhovka Sea.” The water level in the Kakhovka reservoir decreased by more than 4.7 meters since June 6. It has disrupted the water supply of about 1 million people in the area of Dnipropetrivska oblast, Zaporizhska oblast and Kryvyi Rih region. According to information from the Ministry of Environment Protection, more than 160,000 birds and more than 20,000 wild animals were threatened with death due to this disaster. About 17,000 people had to be evacuated.

How many people died? According to the media, about a dozen.

We do not know the exact number of victims, because people are still fleeing and evacuating the region, and we lack data. And the Russians still shoot into the process of evacuation. Russia occupies more than 60 percent of the flooded area. All in there are now 600 square kilometers flooded, it has become a desert – a desert of water. Because there are a lot of dangerous substances in the water, from chemical sites, sewers, industrial plants.

What economic damage do you see?

We cannot calculate this yet; we are in the middle of evacuating and saving people.

Vadym Sydiachenko works at the Department General for Economic Diplomacy at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. He is a member of the Ukrainian delegation to the SB58 conference in Bonn, Germany

The reservoir is also used to irrigate the fields. How much is that affected?

The water of the Kakhovka water reservoir is used for irrigation for all of Southern Ukraine. Also for Crimea, the Crimea Canal takes its water from the Kakhovka water reservoir. With this disaster, we lost our crops for this year in the Khersonska oblast and other southern regions. That is not only a problem for Ukraine, but also for the world. We export the grain to Africa and Asia and lots of countries faced the threat of food risks and famine now.

The Kakhovka Dam was also a hydroelectric power plant. What is the impact of the loss of this energy?

The hydropower plant Kakhovka with its 350-Megawatt capacity was part of six hydropower plants to substitute when Russia destroyed the coal/gas plant this winter. All in all, hydropower supplies about 8 percent of Ukrainian electricity. Now with Kakhovka gone, we have a shortage of electricity and have to take the region off the grid once in a while, a brown-out, so to speak

Is the nuclear power plant in Zaporizhzhia in danger?

The plant and the region are under Russian control. That is why they are totally responsible for that. After the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, there is no water supply to the cooling reservoirs of Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. That might be a problem with the cooling water, but they have reserves for some weeks. But we do not know what the situation at the nuclear station is right now.

How much does the environment suffer from the war?

Nature is suffering terribly. On top of humans and infrastructure, we are losing forests, wetlands, animals, protected areas, and water resources. The additional CO2 from the Ukraine military action alone is considered to be 40 million tons. If you calculate also secondary effects like burning houses, factories, and forests we come up to all amount 100 million tons of CO2 since the war began. Here at the conference, we talk about adaptation to climate change, but how can we adapt when our forests and wetlands are gone?

You claim that the Russians blew up the dam. Is there any proof of this?

First, Russia occupied the territory of the Kakhovka Dam and is completely responsible for this technical object. Second, Ukraine does not have the weapons to destroy a dam like this from a distance. One missile is not enough, it takes a long bombardment, which we do not have the planes for. It was possible to do only from the inside of the construction, in the structure of the dam. And for that, you need to have access to the dam. And Russia controls the area.

The climate conference here in Bonn is proceeding as normal, even though this war is raging in your home country. How do you deal with that?

It is not a normal conference, because our minds are at home. Every night over my home in Kyiv there is an air alarm and our anti-rocket system goes boom boom boom. We are tired when we go to work there, but the Russian terrorist attacks do not let us sleep.

How does it feel to be in the same room with the Russian delegation here?

We do not talk to them. How would you react when your neighbor next door every day tries to kill you and your family? Also, Russia is destroying all international relations. They block every work here like the finding of a new host country for COP29. That is just for destroying the UN system.

How should the UN respond, in your opinion?

We think they should be excluded from the UN for the terrorism against the peaceful people and ecocide in Ukraine. I would like to stress that it is not a war only between Russia and Ukraine, but it is a struggle between democratic countries and tyranny.

In Bonn and beyond, the global stocktake will be a politically fiercely debated assessment of global climate action. But the process faces a problem that has hardly been considered so far: Reliable data on greenhouse gas emissions, which are supposed to form the foundation of the debates, are often in short supply, as Table.Media has recently shown with China as an example.

The UN World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has now reacted to this. It has presented a new instrument called Global Greenhouse Gas Watch for more precise emission data. In the future, emissions will be centrally evaluated by measuring stations and satellites. The results of Global Greenhouse Gas Watch can be directly interlinked with the “central accounting” of the atmosphere. They will also facilitate cooperation between initiatives and projects, says Lars Peter Riishojgaard, responsible for integrated observation systems at the WMO.

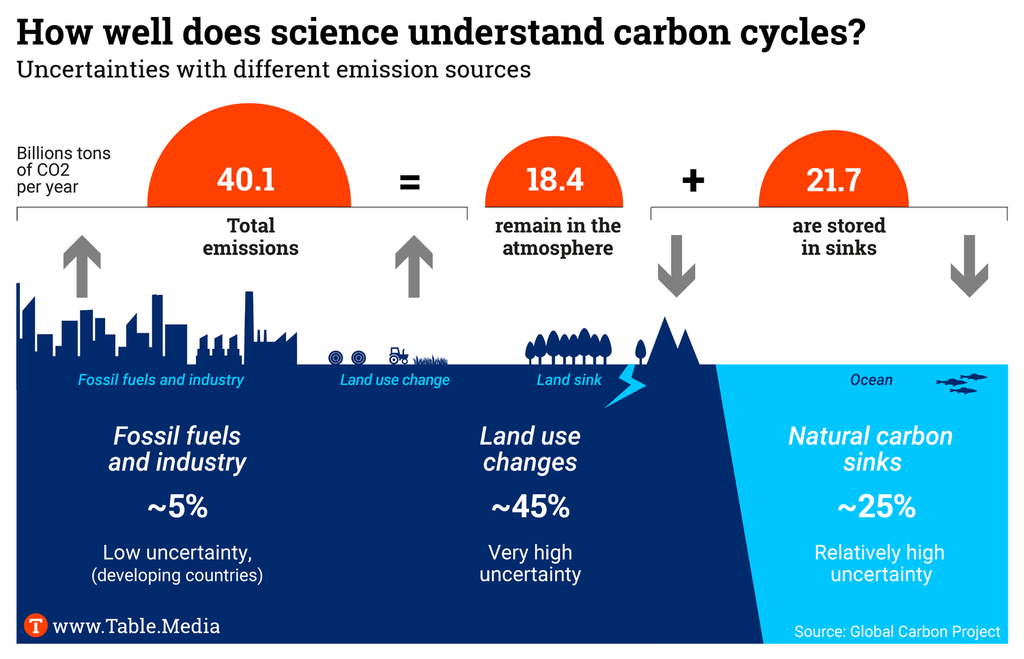

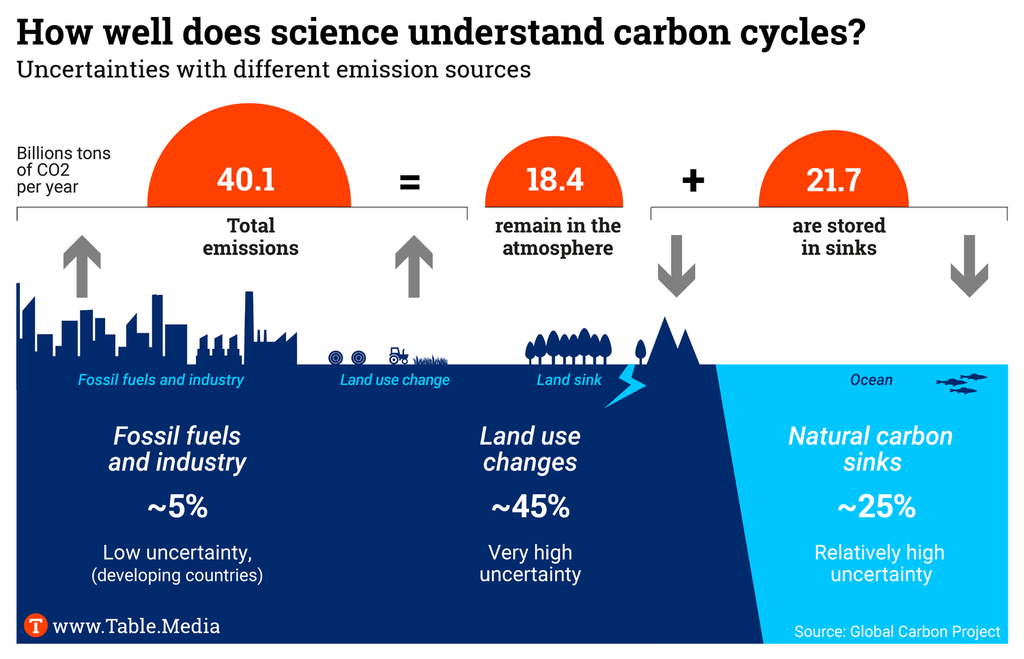

“We have a relatively good understanding of positive emissions,” says Riishojgaard. “But we know very little about negative emissions, for example, from reforestation or reducing deforestation.” Developing countries often do not collect reliable data on a regular basis. For example, in the case of land-use change, there is a high level of uncertainty about how carbon cycles work.

Many problems arise from the way emissions are measured:

If countries do not reliably prepare their national inventories, data quality suffers. A recent study shows that 69 developing countries have problems collecting reliable data on greenhouse gas emissions. Especially island states in the Pacific, African countries and Caribbean states struggle with data collection.

Another study cites an additional reason why emissions data from developing countries is often less reliable: the legal framework under the UNFCCC. The UNFCCC sets different standards for the quality of emissions data: Developed countries (Annex I), for example, must submit detailed and more regular reports on their emissions. Emerging and developing countries (Non-Annex I) must collect data less frequently. This makes the data difficult to compare – and means that discussions are often based on nearly decade-old data.

According to William Lamb of the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), these are not only countries with low emissions: “Even large emitters like China, India or Brazil do not have to renew their inventories every year.” Lars Peter Riishojgaard of the WMO points out other problems: There are far fewer measuring stations for greenhouse gases in the Global South than in the North.

MCC scientist Lamb adds another “huge problem“: “What we know about emissions from agriculture and land-use change is fraught with great uncertainty,” he says.

Wolfgang Obermeier, geographer at the LMU Munich, explains: “Emissions from land use changes cannot be observed directly. They overlap with natural developments and thus have to be calculated using models or statistical methods – there is a wide range of possibilities for this.

In addition, non-Annex I countries often only include forests in their land use change data, leaving out, for example, pastureland or the rewetting of peatlands, says Obermeier. Tighter monitoring, for example, by using satellite data, is needed to improve the quality of emissions data from land use.

The WMO now wants help with this through its “Global Greenhouse Gas Watch” instrument. It is supposed to implement an internationally coordinated top-down approach – as a supplement to the countries’ inventory data. From 2026 onwards, global greenhouse gas fluxes will be published monthly. The resolution will be relatively rough at the beginning with 100 by 100 kilometers but is to be improved to 1 by 1 kilometer by 2030. In addition to CO2, nitrous oxide and methane concentrations will also be mapped.

MCC scientist Lamb stresses that despite improved top-down analysis, it remains important for countries to fill their inventories bottom-up. “Data on fluorinated greenhouse gases can be collected very well through atmospheric measurements,” he says. “They have no natural sources.” But a top-down approach would not capture many details.

For CO₂, which can also be absorbed in natural processes, top-down measurement is difficult. Therefore, it is also necessary that national inventories of emissions data improve, Lam continues. On the one hand, developing countries must invest in building capacities. Especially for large emitters like Brazil, China or India, stricter rules by the UNFCCC would also help.

June 12, 11:45 a.m., Bonn Room

Discussion The GST and Ocean-based Carbon Dioxide Removal: opportunities, uncertainties, risks and future needs.

In order not to exceed warming of about 1.5 °C by 2050, both CO2 removal from the atmosphere and massive reductions in CO₂ emissions are needed. Increased uptake and removal of carbon in the ocean by targeting natural biological and geochemical processes offers opportunities for global inventory, but also poses uncertainties and risks. The side event will discuss whether and how this can be achieved. Info

June 12, 11:45 a.m., Kaminzimmer Room

Discussion Counting the impact of industrial farming on our climate

Industrial agriculture contributes to the climate crisis – for example, through land use change, deforestation or the excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides. The discussion with the Global Forest Coalition, among others, will focus on possible solutions. There will also be a vegan lunch. Info

June 12, 1:15 p.m., Berlin Room

Lecture Accelerating Climate and SDG Synergies as an Enabler for Just Transition

At this side event, UNFCCC and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs will present work on the Synergy Report on Climate Change and the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). Info

June 12, 2:45 p.m., Berlin Room

Discussion A GST that Counts for People: Integrating Health into the Global Stocktake

This event will focus on the links between health and climate change. Examples of intersectoral actions that benefit people and the planet will be presented. Tools and recommendations for incorporating health into the Global Stocktake (GST) will also be discussed. The event is organized by the World Health Organization and others. Info

June 13, 10:45 p.m., Kaminzimmer Room

Info Clarifying obligations and deterring harm: The power of international law to address the climate crisis

The discussion, hosted in part by the Climate Action Network (CAN), will consider how international law can help implement climate action. Info

June 13, 2:45 p.m., Bonn Room

Discussion Taking stock of global progress on nature-based solutions to climate change

Nature-based Solutions are one element of climate action. This side event will discuss how they can be strengthened in the future in connection with the global stocktaking. Info

June 13, 4:15 p.m., Berlin Room

Discussion Achieving sexual and reproductive rights and climate justice

This discussion provides an overview of the intersections between sexual and reproductive rights and climate justice. It also discusses how gender policy can be better integrated into climate policy. Info

June 14, 2:45 p.m., Berlin Room

Discussion Climate Finance for the Needs of Developing Countries

The UNFCCC presents progress and challenges from the Needs-Based Finance program. The program aims to mobilize climate finance resources for developing countries. Info

June 14, 2:45 p.m., Bonn Room

Discussion Reparations for Climate Debt and the road to Just Transition

The transition to a carbon-free future can only succeed if the Global South is compensated for the historic climate debts of the Global North – that is what many stakeholders from the Global South think. At this event, some of them discuss what such reparations could look like. Info

June 14, 4:15 p.m., Bonn Room

Discussion The Bridgetown Initiative – Fit to Finance Climate Justice?

The Bridgetown Initiative has gained significant traction since it was proposed at COP27. It was developed under the leadership of the Government of Barbados and is an innovative proposal to address some of the critical issues in climate finance. Can the initiative contribute to climate justice? Representatives of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and the Global Economy Forum, among others, will discuss this. Info

The CO2 budget still available to the world if global warming is to be limited to 1.5 degrees with a 50 percent probability has probably halved in the past three years. This is the conclusion of a recent study by an international research network. It was recently published in Earth System Science Data and presented at the UN Climate Change Conference SB 58 in Bonn.

The scientists estimate the remaining budget for the beginning of 2023 at about 250 gigatons. For their calculations, they used the methods of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In 2020, the IPCC had still estimated a budget of about 500 gigatons.

The remaining carbon budget “is becoming very small,” the authors wrote in their article – and it could be even smaller than they had calculated. Because according to the report, the estimates of the remaining budget assume that emissions of other greenhouse gases – in addition to CO2 – will also decrease in the future. But if they do not, they will drive up the global temperature rise further than expected. As a consequence, the remaining carbon budget decreases. ae

A team from the Data for Action Foundation has published an online dashboard that provides an overview of key climate change indicators. The indicators are to be updated annually.

The idea behind it: The IPCC’s Assessment Reports are published at fairly long intervals of several years. But given the rate at which the global climate system is changing, policymakers, climate diplomats and civil society need access to more up-to-date, solid scientific evidence. The dashboard’s indicators could thus also find their way into the global stocktake on climate action, which will also be discussed at SB 58.

Further results of the recent study:

Jan Minx, a climate scientist at the Mercator Research Institute for Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC) and one of the study’s authors, calls the results a “wake-up call.” The CO2 budget is likely to be exhausted in a few years, warns Piers Forster, Director of the Priestley Centre for Climate Futures Leeds and lead author of the study. Forster and other representatives of the research network appealed to international climate policymakers to urgently cut greenhouse gas emissions. ae

Many major cities and companies still do not have net zero targets and jeopardize national climate goals. This is the finding of the Net Zero Stocktake report published today. According to the study, more and more countries are embedding net zero climate targets in national laws and policies. So it is not just lip service, but net zero pledges are flowing into political processes, the study says.

However, large cities and companies lag behind in the implementation and credibility of net-zero targets, he said:

Milena Glimbovski has been one of the most well-known voices in German climate activism for years. In 2014, at the age of 24, she opened “Original Unverpackt,” one of the first shops in Germany to not use any packaging, and became a pioneer of the zero-waste movement. In 2017, she published her book “Ohne Wenn und Abfall.” Not long after, the Berlin Senate and the Chamber of Industry and Commerce named her Entrepreneur of the Year. In the meantime, Glimbovski was also the founder of a publishing house – the calendar “Ein guter Plan” (A Good Plan) created by her and her partner won numerous design and sustainability awards. And Deutsche Welle called her a “Climate Hero.”

But when climate heroism meets reality, disillusionment inevitably sets in. The deep focus on climate and environmental issues made Milena Glimbovski feel anxious and helpless. “I felt overwhelmed. Not only by the news, but by everything that had to be done,” says the now 33-year-old. “I couldn’t understand what was actually going to happen in Germany in the next few years. It scared me, especially when I had my son five years ago.”

Since then, she has worked intensively on ways to adapt to climate impacts. Now, she has published her book “Über Leben in der Klimakrise” (“On Living in the Climate Crisis”). In it, she criticizes the lack of preparation by politicians and businesses and identifies the structural and social levels at which climate adaptation is necessary. The list is long: flood protection, drinking water supply, sea-level rise, agriculture, energy, disaster prevention, urban planning, and migration. Numerous economic sectors will have to adapt: Logistics, the construction industry, tourism and the insurance sector are just a few examples.

A closer look also reveals that the different areas can conflict with each other, as Glimbovski shows with the example of the 2021 flood disaster in Germany: “Many insurance policies are designed in such a way that people have to rebuild the same house in the same place, otherwise the insurance company won’t pay. But those people would have to rebuild or move elsewhere.” It is a big problem that certain areas are designated as good building land even though they are in a flood hazard area. “That’s where economic interests were more important than people’s safety.”

Water is, unsurprisingly, one of the main themes of her book. In addition to improved flood protection, she calls for fundamental changes in agriculture, which has also suffered from massive drought in Germany for years. “The question is there: Does agriculture need water to produce food? Or does it need water to produce grain that goes to biogas plants or is used for animal feed?”

She advocates regenerative agriculture, which still exceeds the organic criteria and focuses primarily on the health of soils and plants. She believes this can help, especially in dry times. Studies, such as the most recent by the Boston Consulting Group and the Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU), suggest that switching to regenerative agriculture that does not deplete soils can lead to up to 60 percent higher yields after 6 to 10 years. Risks in supply chains could be reduced by about half in drought years, the study says. “It’s a long and expensive road,” Glimbovski admits. But the alternative, she says, is to let people starve. “We have no choice but to adapt agriculture if we want to feed ourselves safely, fairly, socially and healthily in the future. To do that, we must better protect soils, water and ecosystems.”

In addition to all the technical aspects of climate adaptation, Milena Glimbovski does not lose sight of another measure that she personally had so much difficulty in the beginning: The emotional and psychological coping with the climate crisis. “Psychology is so important to me because in my work, I kept noticing how it paralyzed me.” Writing the book, doing the research, talking to experts, and understanding what was actually happening psychologically helped her, she said. She deliberately consumes climate news only at a specific time of day. “I take breaks, talk to people about it, and have people around me who also take it seriously. It helps to have a sense of community.”

That’s why she would like to see more focus on the real-world consequences. “We need to talk about climate adaptation now,” she says. But does that mean that the fight against climate change is already lost? And that what matters most now is preparedness? She rejects such fatalism: “Both are a century-long task.” Mitigation is essential and every decimal point counts when it comes to temperature increases, she says. “But I’m also a realist, and I see: The climate crisis is here. And we have to learn to adapt.” Stefan Boes

This is what happens when no one is really paying attention: At a meeting in Brussels in March, the EU Council of Ministers decided, among many other issues, on a new climate policy course: Instead of continuing to call for ending all fossil fuels without any ifs and buts, they now say: If the as-yet unproven technology of CO2 capture (CCS) is used for this purpose, that would also be okay. So maybe fossil fuels still have a future in a climate-neutral EU.

The next COP President Sultan Al-Jaber from the United Arab Emirates takes the same position. However, he receives criticism everywhere for it, while the Europeans get away with it so far. As soon as we discovered this, we quickly needed to write it down. This is another thing that climate conferences are useful for, as we have been noticing with our team in Bonn for a week now.

There are also exciting developments elsewhere: For example, the quiet revolution at the World Meteorological Organisation WMO: Instead of relying on insufficient data from many countries like in the past, measurements on greenhouse gases are now to be organized globally. And Ukraine is now calling for Russia’s expulsion from the UN for eco-terrorism after the destruction of the Kharkhova dam – as a high-ranking delegation member in Bonn tells us in an interview.

We are also in our second week at the climate conference in Bonn. And will continue to stay on it.

The European Union has committed in principle to the same course as the COP presidency from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and other oil states on a controversial issue at the next COP28: To use the controversial CCS technology as a loophole in the phase-out of fossil fuels. The EU now seeks a decision at COP28 that would allow this formulation. This became apparent on the sidelines of the Bonn Climate Change Conference. Irrespective of this, a new assessment by the think tank project “Climate Action Tracker” calls the EU’s climate policy “insufficient.”

On the path to climate neutrality, it will be possible to capture and store emissions not only from industrial processes but also from the energy sector, according to a decision by the EU Council of Ministers back in March. Up to now, the Europeans had rejected the use of CCS for the energy sector and, for example, demanded “a phase-down of fossil energies” at COP27 without mentioning CCS. The European position now only calls for an “energy system free of unabated fossil fuels.”

This decision, which has been barely known to the public, is not only a rapprochement with oil and gas producing countries such as the UAE or the United States. It also contradicts the German position. At the Petersberg Climate Dialogue, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock had clearly stated her disagreement with the next COP President, Sultan Ahmed Al-Jaber, on this point: “We have to get out of fossil fuels,” she said – while Al-Jaber stressed that the world has to come to terms with the realities. “Fossil fuels will continue to play a role.” The goal, he said, should be to “phase out emissions.”

State Secretary Jennifer Morgan also said she did not believe “CCS would get us there.” And Robert Habeck’s Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action is working on a German CCS management strategy whose clear stipulation is: CCS only for process emissions from the industrial sector – not as a way out for fossil fuels in the energy sector.

However, the new EU position now leaves this possibility open. An “energy system free of unabated fossil fuels” potentially also includes the application of CCS technology in electricity generation and for combustion in industry. The resolution is a little more concrete than Al-Jaber’s “phasing out emissions,” as it refers to an IPCC definition of “unabated fossil fuels” and a fossil peak well before 2050. Al-Jaber, on the other hand, used the EU term of an energy system “free of unabated fossil fuels” in a speech at the Bonn conference.

The EU Commission is aware that the decision gives fossil fuels the right to exist as fuels even in a climate-neutral EU. In any case, the plan is that even with the EU’s net-zero target, emissions from industry or agriculture will still be stored in nature or through CCS. In the debates for an opening to “unabated fuels,” countries such as Poland and Denmark, in particular, have exerted pressure, according to negotiating circles.

The EU’s change of course makes a compromise on this controversial issue at COP28 more likely. Many other influential countries whose economies still rely heavily on fossil fuels are openly or in secret striving for this goal: The oil states, the United States, but also China or European countries like Norway and Denmark, which are already working on CCS projects.

For the Climate Action Tracker (CAT) scientists, however, CCS is a “dangerous distraction.” CCS should not be used to reduce emissions in the energy sector because “far cheaper renewables are available,” says Claire Stockwell of the CAT project organization Climate Analytics. In its recent report mid-way to COP28, the EU does not score well either: Its continued investment in new fossil fuel infrastructure, especially LNG terminals and gas pipelines, “undermines the EU’s decarbonization efforts,” it says. CAT rates the EU’s climate policy as a whole as “insufficient” also because the EU has not yet raised its climate target (NDC) submitted to the UN as promised.

Generally, the main arguments of CCS critics are that the technology is more expensive than renewables, has not been tested on a large scale worldwide, and is too late to achieve the necessary 50% reduction in global emissions by 2030. But Alden Meyer, a climate expert at the think tank E3G, hopes that a possible COP28 declaration on the fossil flue end will at least define sectoral targets with the help of CCS: Then the addition of “unabated” would not be so problematic, says Meyer. Because then it would be clear that only the few sectors that are difficult to decarbonize could resort to technologies such as CCS.

Moreover, the EU would then have to assess the potential of CCS realistically, Meyer said. “If you recognize that CCS can prevent maybe only five percent of emissions, then it would be clear that the phase-down would be 95 fossil fuels of any kind.” In any case, the UAE, a strong proponent of CCS, plans to store only 2 percent of its emissions this way by 2030, according to CAT.

Meyer, therefore, demands that the EU clarify the role it attributes to CCS for the envisaged phase-down. But for this, a generally accepted definition of what counts as “abated fuel” is first needed. Last week, the Commission launched a public consultation on CCS to examine what role CCS can play in decarbonization by 2030, 2040 and 2050.

Experts from the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) also call for a debate on this issue. They note that CCS is being discussed in countries with high exports of fossil fuels as a means of safeguarding fossil fuel business models to ease the pressure to abandon fossil fuels. They assume that the overall potential of the technology is limited: By 2050, a total of 550 million tons of CO2 could be stored in the EU. Worldwide, the International Energy Agency (IEA) expects just over 5 billion tons in 2050.

What are the economic and ecological results of the disaster at the Kakhovka Dam?

This is a case of ecocide. President Zelenskyy was on Thursday in the region of flooding and the nearby regions, and he had a virtual meeting from Kryvyi Rih city with representatives of the global environmental protection community, including the Vice President from the EU Parliament, activist Greta Thunberg and others. He asked them to label this as ecocide. The region flooded is one of the biggest industrial and agricultural centers in Europe. There are many storage houses for chemicals and fertilizer in the Kherson oblast, also there is a lot of mining, and the biggest steel plant in Ukraine nearby this area in the Kryvyi Rih region. All of their dangerous materials are in the water now, and all of that will go into the Black Sea. It is an international disaster and an act of eco-terrorism by Russia.

How dangerous is the flooding?

The water reservoir at Kakhovka Dam is known as the “Kakhovka Sea.” The water level in the Kakhovka reservoir decreased by more than 4.7 meters since June 6. It has disrupted the water supply of about 1 million people in the area of Dnipropetrivska oblast, Zaporizhska oblast and Kryvyi Rih region. According to information from the Ministry of Environment Protection, more than 160,000 birds and more than 20,000 wild animals were threatened with death due to this disaster. About 17,000 people had to be evacuated.

How many people died? According to the media, about a dozen.

We do not know the exact number of victims, because people are still fleeing and evacuating the region, and we lack data. And the Russians still shoot into the process of evacuation. Russia occupies more than 60 percent of the flooded area. All in there are now 600 square kilometers flooded, it has become a desert – a desert of water. Because there are a lot of dangerous substances in the water, from chemical sites, sewers, industrial plants.

What economic damage do you see?

We cannot calculate this yet; we are in the middle of evacuating and saving people.

Vadym Sydiachenko works at the Department General for Economic Diplomacy at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. He is a member of the Ukrainian delegation to the SB58 conference in Bonn, Germany

The reservoir is also used to irrigate the fields. How much is that affected?

The water of the Kakhovka water reservoir is used for irrigation for all of Southern Ukraine. Also for Crimea, the Crimea Canal takes its water from the Kakhovka water reservoir. With this disaster, we lost our crops for this year in the Khersonska oblast and other southern regions. That is not only a problem for Ukraine, but also for the world. We export the grain to Africa and Asia and lots of countries faced the threat of food risks and famine now.

The Kakhovka Dam was also a hydroelectric power plant. What is the impact of the loss of this energy?

The hydropower plant Kakhovka with its 350-Megawatt capacity was part of six hydropower plants to substitute when Russia destroyed the coal/gas plant this winter. All in all, hydropower supplies about 8 percent of Ukrainian electricity. Now with Kakhovka gone, we have a shortage of electricity and have to take the region off the grid once in a while, a brown-out, so to speak

Is the nuclear power plant in Zaporizhzhia in danger?

The plant and the region are under Russian control. That is why they are totally responsible for that. After the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, there is no water supply to the cooling reservoirs of Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. That might be a problem with the cooling water, but they have reserves for some weeks. But we do not know what the situation at the nuclear station is right now.

How much does the environment suffer from the war?

Nature is suffering terribly. On top of humans and infrastructure, we are losing forests, wetlands, animals, protected areas, and water resources. The additional CO2 from the Ukraine military action alone is considered to be 40 million tons. If you calculate also secondary effects like burning houses, factories, and forests we come up to all amount 100 million tons of CO2 since the war began. Here at the conference, we talk about adaptation to climate change, but how can we adapt when our forests and wetlands are gone?

You claim that the Russians blew up the dam. Is there any proof of this?

First, Russia occupied the territory of the Kakhovka Dam and is completely responsible for this technical object. Second, Ukraine does not have the weapons to destroy a dam like this from a distance. One missile is not enough, it takes a long bombardment, which we do not have the planes for. It was possible to do only from the inside of the construction, in the structure of the dam. And for that, you need to have access to the dam. And Russia controls the area.

The climate conference here in Bonn is proceeding as normal, even though this war is raging in your home country. How do you deal with that?

It is not a normal conference, because our minds are at home. Every night over my home in Kyiv there is an air alarm and our anti-rocket system goes boom boom boom. We are tired when we go to work there, but the Russian terrorist attacks do not let us sleep.

How does it feel to be in the same room with the Russian delegation here?

We do not talk to them. How would you react when your neighbor next door every day tries to kill you and your family? Also, Russia is destroying all international relations. They block every work here like the finding of a new host country for COP29. That is just for destroying the UN system.

How should the UN respond, in your opinion?

We think they should be excluded from the UN for the terrorism against the peaceful people and ecocide in Ukraine. I would like to stress that it is not a war only between Russia and Ukraine, but it is a struggle between democratic countries and tyranny.

In Bonn and beyond, the global stocktake will be a politically fiercely debated assessment of global climate action. But the process faces a problem that has hardly been considered so far: Reliable data on greenhouse gas emissions, which are supposed to form the foundation of the debates, are often in short supply, as Table.Media has recently shown with China as an example.

The UN World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has now reacted to this. It has presented a new instrument called Global Greenhouse Gas Watch for more precise emission data. In the future, emissions will be centrally evaluated by measuring stations and satellites. The results of Global Greenhouse Gas Watch can be directly interlinked with the “central accounting” of the atmosphere. They will also facilitate cooperation between initiatives and projects, says Lars Peter Riishojgaard, responsible for integrated observation systems at the WMO.

“We have a relatively good understanding of positive emissions,” says Riishojgaard. “But we know very little about negative emissions, for example, from reforestation or reducing deforestation.” Developing countries often do not collect reliable data on a regular basis. For example, in the case of land-use change, there is a high level of uncertainty about how carbon cycles work.

Many problems arise from the way emissions are measured:

If countries do not reliably prepare their national inventories, data quality suffers. A recent study shows that 69 developing countries have problems collecting reliable data on greenhouse gas emissions. Especially island states in the Pacific, African countries and Caribbean states struggle with data collection.

Another study cites an additional reason why emissions data from developing countries is often less reliable: the legal framework under the UNFCCC. The UNFCCC sets different standards for the quality of emissions data: Developed countries (Annex I), for example, must submit detailed and more regular reports on their emissions. Emerging and developing countries (Non-Annex I) must collect data less frequently. This makes the data difficult to compare – and means that discussions are often based on nearly decade-old data.

According to William Lamb of the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), these are not only countries with low emissions: “Even large emitters like China, India or Brazil do not have to renew their inventories every year.” Lars Peter Riishojgaard of the WMO points out other problems: There are far fewer measuring stations for greenhouse gases in the Global South than in the North.

MCC scientist Lamb adds another “huge problem“: “What we know about emissions from agriculture and land-use change is fraught with great uncertainty,” he says.

Wolfgang Obermeier, geographer at the LMU Munich, explains: “Emissions from land use changes cannot be observed directly. They overlap with natural developments and thus have to be calculated using models or statistical methods – there is a wide range of possibilities for this.

In addition, non-Annex I countries often only include forests in their land use change data, leaving out, for example, pastureland or the rewetting of peatlands, says Obermeier. Tighter monitoring, for example, by using satellite data, is needed to improve the quality of emissions data from land use.

The WMO now wants help with this through its “Global Greenhouse Gas Watch” instrument. It is supposed to implement an internationally coordinated top-down approach – as a supplement to the countries’ inventory data. From 2026 onwards, global greenhouse gas fluxes will be published monthly. The resolution will be relatively rough at the beginning with 100 by 100 kilometers but is to be improved to 1 by 1 kilometer by 2030. In addition to CO2, nitrous oxide and methane concentrations will also be mapped.

MCC scientist Lamb stresses that despite improved top-down analysis, it remains important for countries to fill their inventories bottom-up. “Data on fluorinated greenhouse gases can be collected very well through atmospheric measurements,” he says. “They have no natural sources.” But a top-down approach would not capture many details.

For CO₂, which can also be absorbed in natural processes, top-down measurement is difficult. Therefore, it is also necessary that national inventories of emissions data improve, Lam continues. On the one hand, developing countries must invest in building capacities. Especially for large emitters like Brazil, China or India, stricter rules by the UNFCCC would also help.

June 12, 11:45 a.m., Bonn Room

Discussion The GST and Ocean-based Carbon Dioxide Removal: opportunities, uncertainties, risks and future needs.

In order not to exceed warming of about 1.5 °C by 2050, both CO2 removal from the atmosphere and massive reductions in CO₂ emissions are needed. Increased uptake and removal of carbon in the ocean by targeting natural biological and geochemical processes offers opportunities for global inventory, but also poses uncertainties and risks. The side event will discuss whether and how this can be achieved. Info

June 12, 11:45 a.m., Kaminzimmer Room

Discussion Counting the impact of industrial farming on our climate

Industrial agriculture contributes to the climate crisis – for example, through land use change, deforestation or the excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides. The discussion with the Global Forest Coalition, among others, will focus on possible solutions. There will also be a vegan lunch. Info

June 12, 1:15 p.m., Berlin Room

Lecture Accelerating Climate and SDG Synergies as an Enabler for Just Transition

At this side event, UNFCCC and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs will present work on the Synergy Report on Climate Change and the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). Info

June 12, 2:45 p.m., Berlin Room

Discussion A GST that Counts for People: Integrating Health into the Global Stocktake

This event will focus on the links between health and climate change. Examples of intersectoral actions that benefit people and the planet will be presented. Tools and recommendations for incorporating health into the Global Stocktake (GST) will also be discussed. The event is organized by the World Health Organization and others. Info

June 13, 10:45 p.m., Kaminzimmer Room

Info Clarifying obligations and deterring harm: The power of international law to address the climate crisis

The discussion, hosted in part by the Climate Action Network (CAN), will consider how international law can help implement climate action. Info

June 13, 2:45 p.m., Bonn Room

Discussion Taking stock of global progress on nature-based solutions to climate change

Nature-based Solutions are one element of climate action. This side event will discuss how they can be strengthened in the future in connection with the global stocktaking. Info

June 13, 4:15 p.m., Berlin Room

Discussion Achieving sexual and reproductive rights and climate justice

This discussion provides an overview of the intersections between sexual and reproductive rights and climate justice. It also discusses how gender policy can be better integrated into climate policy. Info

June 14, 2:45 p.m., Berlin Room

Discussion Climate Finance for the Needs of Developing Countries

The UNFCCC presents progress and challenges from the Needs-Based Finance program. The program aims to mobilize climate finance resources for developing countries. Info

June 14, 2:45 p.m., Bonn Room

Discussion Reparations for Climate Debt and the road to Just Transition

The transition to a carbon-free future can only succeed if the Global South is compensated for the historic climate debts of the Global North – that is what many stakeholders from the Global South think. At this event, some of them discuss what such reparations could look like. Info

June 14, 4:15 p.m., Bonn Room

Discussion The Bridgetown Initiative – Fit to Finance Climate Justice?

The Bridgetown Initiative has gained significant traction since it was proposed at COP27. It was developed under the leadership of the Government of Barbados and is an innovative proposal to address some of the critical issues in climate finance. Can the initiative contribute to climate justice? Representatives of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and the Global Economy Forum, among others, will discuss this. Info

The CO2 budget still available to the world if global warming is to be limited to 1.5 degrees with a 50 percent probability has probably halved in the past three years. This is the conclusion of a recent study by an international research network. It was recently published in Earth System Science Data and presented at the UN Climate Change Conference SB 58 in Bonn.

The scientists estimate the remaining budget for the beginning of 2023 at about 250 gigatons. For their calculations, they used the methods of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In 2020, the IPCC had still estimated a budget of about 500 gigatons.

The remaining carbon budget “is becoming very small,” the authors wrote in their article – and it could be even smaller than they had calculated. Because according to the report, the estimates of the remaining budget assume that emissions of other greenhouse gases – in addition to CO2 – will also decrease in the future. But if they do not, they will drive up the global temperature rise further than expected. As a consequence, the remaining carbon budget decreases. ae

A team from the Data for Action Foundation has published an online dashboard that provides an overview of key climate change indicators. The indicators are to be updated annually.

The idea behind it: The IPCC’s Assessment Reports are published at fairly long intervals of several years. But given the rate at which the global climate system is changing, policymakers, climate diplomats and civil society need access to more up-to-date, solid scientific evidence. The dashboard’s indicators could thus also find their way into the global stocktake on climate action, which will also be discussed at SB 58.

Further results of the recent study:

Jan Minx, a climate scientist at the Mercator Research Institute for Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC) and one of the study’s authors, calls the results a “wake-up call.” The CO2 budget is likely to be exhausted in a few years, warns Piers Forster, Director of the Priestley Centre for Climate Futures Leeds and lead author of the study. Forster and other representatives of the research network appealed to international climate policymakers to urgently cut greenhouse gas emissions. ae

Many major cities and companies still do not have net zero targets and jeopardize national climate goals. This is the finding of the Net Zero Stocktake report published today. According to the study, more and more countries are embedding net zero climate targets in national laws and policies. So it is not just lip service, but net zero pledges are flowing into political processes, the study says.

However, large cities and companies lag behind in the implementation and credibility of net-zero targets, he said:

Milena Glimbovski has been one of the most well-known voices in German climate activism for years. In 2014, at the age of 24, she opened “Original Unverpackt,” one of the first shops in Germany to not use any packaging, and became a pioneer of the zero-waste movement. In 2017, she published her book “Ohne Wenn und Abfall.” Not long after, the Berlin Senate and the Chamber of Industry and Commerce named her Entrepreneur of the Year. In the meantime, Glimbovski was also the founder of a publishing house – the calendar “Ein guter Plan” (A Good Plan) created by her and her partner won numerous design and sustainability awards. And Deutsche Welle called her a “Climate Hero.”

But when climate heroism meets reality, disillusionment inevitably sets in. The deep focus on climate and environmental issues made Milena Glimbovski feel anxious and helpless. “I felt overwhelmed. Not only by the news, but by everything that had to be done,” says the now 33-year-old. “I couldn’t understand what was actually going to happen in Germany in the next few years. It scared me, especially when I had my son five years ago.”

Since then, she has worked intensively on ways to adapt to climate impacts. Now, she has published her book “Über Leben in der Klimakrise” (“On Living in the Climate Crisis”). In it, she criticizes the lack of preparation by politicians and businesses and identifies the structural and social levels at which climate adaptation is necessary. The list is long: flood protection, drinking water supply, sea-level rise, agriculture, energy, disaster prevention, urban planning, and migration. Numerous economic sectors will have to adapt: Logistics, the construction industry, tourism and the insurance sector are just a few examples.

A closer look also reveals that the different areas can conflict with each other, as Glimbovski shows with the example of the 2021 flood disaster in Germany: “Many insurance policies are designed in such a way that people have to rebuild the same house in the same place, otherwise the insurance company won’t pay. But those people would have to rebuild or move elsewhere.” It is a big problem that certain areas are designated as good building land even though they are in a flood hazard area. “That’s where economic interests were more important than people’s safety.”

Water is, unsurprisingly, one of the main themes of her book. In addition to improved flood protection, she calls for fundamental changes in agriculture, which has also suffered from massive drought in Germany for years. “The question is there: Does agriculture need water to produce food? Or does it need water to produce grain that goes to biogas plants or is used for animal feed?”

She advocates regenerative agriculture, which still exceeds the organic criteria and focuses primarily on the health of soils and plants. She believes this can help, especially in dry times. Studies, such as the most recent by the Boston Consulting Group and the Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU), suggest that switching to regenerative agriculture that does not deplete soils can lead to up to 60 percent higher yields after 6 to 10 years. Risks in supply chains could be reduced by about half in drought years, the study says. “It’s a long and expensive road,” Glimbovski admits. But the alternative, she says, is to let people starve. “We have no choice but to adapt agriculture if we want to feed ourselves safely, fairly, socially and healthily in the future. To do that, we must better protect soils, water and ecosystems.”

In addition to all the technical aspects of climate adaptation, Milena Glimbovski does not lose sight of another measure that she personally had so much difficulty in the beginning: The emotional and psychological coping with the climate crisis. “Psychology is so important to me because in my work, I kept noticing how it paralyzed me.” Writing the book, doing the research, talking to experts, and understanding what was actually happening psychologically helped her, she said. She deliberately consumes climate news only at a specific time of day. “I take breaks, talk to people about it, and have people around me who also take it seriously. It helps to have a sense of community.”

That’s why she would like to see more focus on the real-world consequences. “We need to talk about climate adaptation now,” she says. But does that mean that the fight against climate change is already lost? And that what matters most now is preparedness? She rejects such fatalism: “Both are a century-long task.” Mitigation is essential and every decimal point counts when it comes to temperature increases, she says. “But I’m also a realist, and I see: The climate crisis is here. And we have to learn to adapt.” Stefan Boes