COP28 is slowly approaching the finishing line. Yesterday, COP President Al Jaber urged countries to work “harder,” be more flexible and make compromises. He intends to conclude the conference at 11 a.m. on Tuesday. But on the COP’s corridors, the first bets have already been made on how long COP will go into overtime this year.

The most heated debate currently revolves around phasing out fossil fuels. Many countries want to focus on “abatement,” i.e., continuing to use fossil fuels while reducing emissions. However, there is no clear definition of what “abatement” actually means. Lukas Scheid describes why a clear definition and universally applicable standards could lead to a CO2 bomb.

There are also heated debates about a global goal for adaptation to the impacts of the climate crisis. Countries are still arguing about how adaptation can be measured, what concrete sub-goals could look like, who should contribute, and how much to their financing. Alexandra Endres has compiled the details.

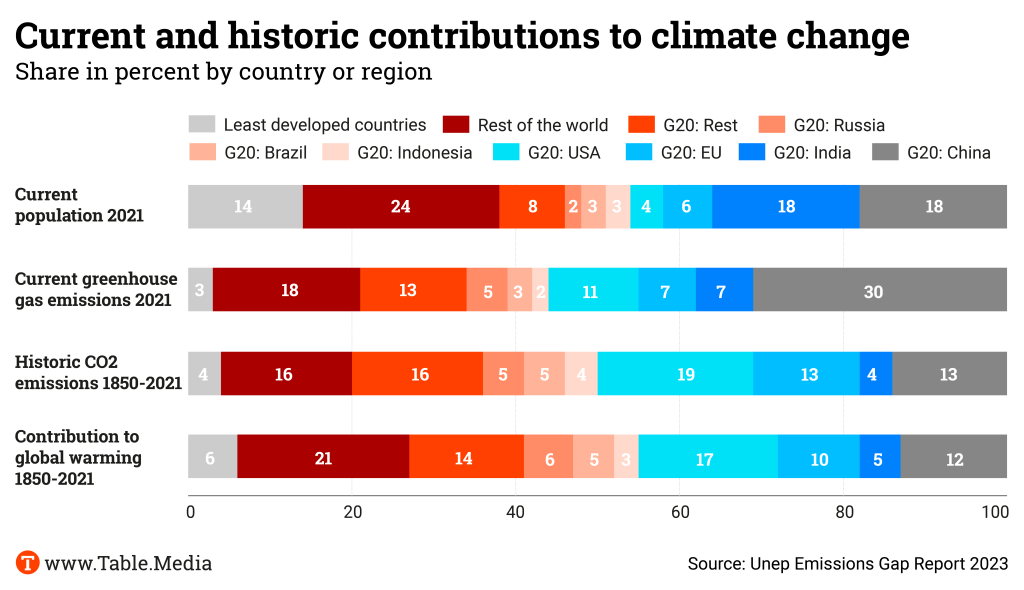

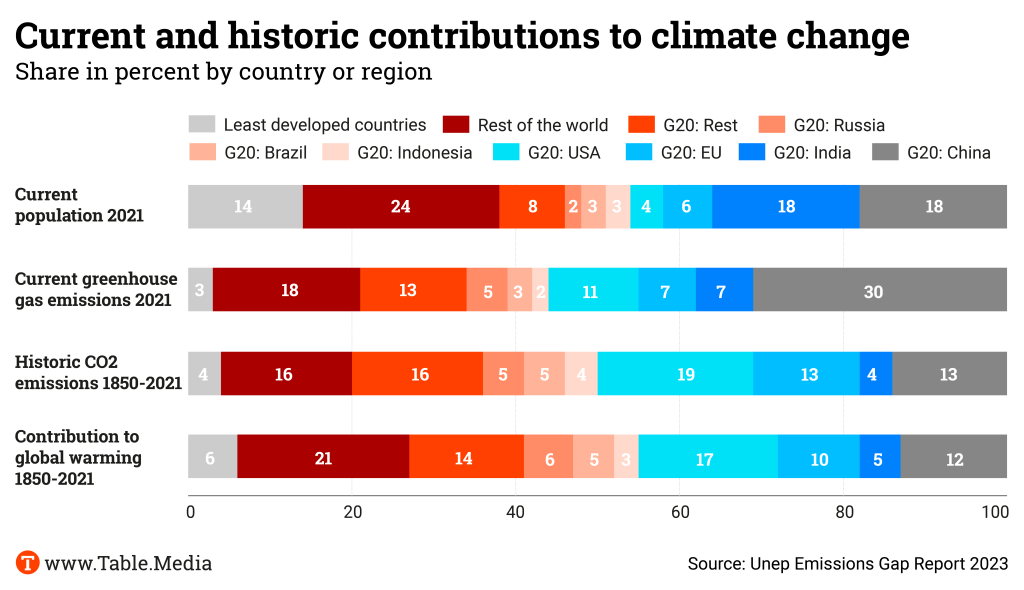

Climate conferences could take on a completely different dynamic in the near future. Several studies have now found that developing and emerging countries have historically contributed the most to the climate crisis – at least in absolute figures, reports Bernhard Pötter. So far, developed countries have had a special obligation because they have long emitted the most historic and per capita emissions.

Amidst the final negotiations at COP, a controversial study shows that emerging and developing countries drive global warming more than developed countries and their historical emissions. This shakes a core narrative of the UN climate process. The matter is correspondingly uncomfortable for many countries.

The signs are changing on a central question of global climate policy: According to a new study published in the scientific journal Nature, the countries of the Global South have now contributed more to global warming through their greenhouse gas emissions than developed countries. According to the Framework Convention on Climate Change (“Annex I”), the developed countries’ share of historical contributions to global warming between 1851 and 2021 is 44.8 percent. In contrast, the share of emerging and developing countries (“non-Annex I”) is 53.5 percent. The results of the study are consistent with UN and IPCC data.

This challenges a core message that has dominated global climate diplomacy in recent decades: The narrative that developed countries are the main culprits of the climate crisis – and that the rest of the world has contributed little to it. For instance, the G77/China proposal for a Global Stocktake resolution at COP28 speaks of “historical gaps in implementation of mitigation actions” and the “historical responsibility of developed countries to take leadership in climate action.” The argument underlying many UN resolutions is that developed countries must step up their climate efforts and provide financial support to developing countries as they have emitted the most CO2 and have become richer on average thanks to this fossil-fuelled growth.

But the claim that the Global North has historically been the biggest polluter has now been clearly disproven. The new study shows this because it uses comprehensive data: In addition to carbon emissions from fossil fuel combustion, it also calculates those from land use and forest destruction, which are otherwise often overlooked. It also highlights the climate effects of methane and nitrogen oxide emissions. The individual findings:

The figures look different if only emissions from the use of fossil fuels are considered: Here, the classic developed countries still account for the majority of emissions at 54.1 percent. When it comes to warming caused by emissions from land use (LULUCF), on the other hand, emerging and developing countries are clearly in the lead with 73 percent.

The question regarding the contributions to emissions and global warming is so politically sensitive in the UNFCCC process that it is not a popular topic to discuss openly. A chart in the 6th IPCC Assessment Report, for example, shows historical emissions from fossil sources and land use by country group. Here, too, the classic developed countries in North America, Europe and Japan/Oceania only account for 43 percent. However, ten percent are assigned to the “Eastern Europe and Western Central Asia” group, which does not correspond to the UNFCCC Annex categories. This makes a clear statement about which countries in this group are Annex or non-Annex countries impossible, as is a clear categorization of emissions into developed or developing countries.

Yet the data in the current paper is clear. According to William Lamb, emissions expert at the MCC Berlin and author of IPCC and UNEP reports on the subject, who was not involved in the current study, the contributions to warming between the two groups started to overlap around 2009. “Since then, the share of non-annex countries in global warming has been higher than the historical contributions of developed countries.” In 2009, the COP15 in Copenhagen failed because the global North and South could not agree on who should reduce how many emissions. “The calculation and presentation of these figures at the IPCC and UNEP are a deeply political matter for the country delegations and are also negotiated in this way,” Lamb told Table.Media. There has yet to be a major political debate on this issue.

The latest Unep Emissions Gap Report also examines the gap in the necessary emissions reductions: In 2022, global greenhouse gas emissions reached an all-time high of 57.4 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent, with an increase of 1.2 percent. However, the report also lists historical emissions and connects them to other equally important aspects: In addition to the volume of historical emissions and the contribution to warming, it also presents the per capita emissions of countries and country groups, for example. If the historical emissions of the G20 countries are broken down into developed and emerging countries, the trend of developed countries becoming less important is also evident.

For instance, China has revised its demands in its proposals for incorporating the Global Stocktake into the COP resolutions. Instead of blaming developed countries for the climate crisis overall, China now argues:

This shifts the debate from a purely quantitative question to a qualified consideration of emissions: for example, per capita or per country’s economic output. However, this shifts global responsibilities.

Click here for all previously published COP28 articles.

Time is running out for the new Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), which is to be adopted in Dubai. The delegations only received a foundation on which to negotiate the content three days before the end of the climate summit. The draft was presented on Sunday at 8.30 a.m. local time. Previously, the presidency had intervened – apparently out of concern that the GGA could fall by the wayside.

There is now very little time for substantive work on the text. The framework for the GGA needs to be adopted in Dubai so that it can be fleshed out by next year’s climate summit as planned.

The main disputes revolve around:

The discussions on Sunday evening were apparently so deadlocked that the ministers decided to address the matter in particular. The Arab countries were still opposed to the overall COP package – they had previously blocked the adaptation negotiations tracks in order to stall overall progress. However, there were also disagreements between developed and developing countries on the GGA framework.

African countries had already introduced the adaptation goal into the UN negotiation process ten years ago, and it was then mentioned in writing for the first time in Article 7 of the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015: The goal is to enhance “adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change.”

This is mainly in the interests of countries more vulnerable to the climate crisis than others. However, according to German Development Secretary Jochen Flasbarth in Dubai on Sunday, developed countries must prepare for a future with even more climate extremes: “The Global Goal on Adaptation is not just aimed at developing countries. The world as a whole is to become more resilient.”

The GGA is intended to create the basis for this in the form of a framework. It is to include an overarching goal that is concretized by – preferably measurable – sub-goals as well as instruments for practical implementation, review procedures and, if necessary, readjustment, as well as financing. A working group had been working on this for two years. It only presented some formulation proposals shortly before Dubai. This was another factor that slowed down the start of the GGA negotiations at COP28.

It will now be difficult to reach an agreement in time. One sticking point is funding. The more the climate crisis progresses the more the need for money for adaptation increases. The consequences of global warming are already more severe than expected, as the IPCC’s latest assessment report shows. However, instead of increasing, public funding for adaptation has recently decreased by 15 percent to 21 billion US dollars annually.

“It is about saving lives,” said Mohamed Adow, Director of the NGO Power Shift Africa, in Dubai, referring to the UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report, which estimates future financing needs for adaptation at 387 billion US dollars annually. According to negotiating circles, there was also a reference to the figure in an initial GGA draft text in Dubai. However, it is now absent from Sunday’s text.

It would be particularly important for developing countries to have concrete figures anchored in the GGA, as this would link funding very clearly to adaptation purposes. Adow warns of a “humanitarian crisis” if adaptation funding does not increase. The current GGA draft text falls short, he says. A GGA framework must be adopted in Dubai that gives vulnerable countries the necessary confidence “that they will receive sufficient financial support to adapt.”

However, unlike the developing countries, the developed countries would prefer to anchor adaptation financing in other negotiation tracks. One option would be in the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG), which will be adopted at the COP next year.

Another disputed demand is to stipulate in the GGA which countries should pay for adaptation. Among others, Germany is in favor of this. Adaptation funding “from classic donor countries” will increase from 20 billion in 2019 to 40 billion in 2025, said German State Secretary for Development Jochen Flasbarth in Dubai on Sunday. “That has already been decided. We stand by it.” A BMZ spokesperson said in response to a question about how the financing will look after 2025 in view of the increasing climate risks.

Flasbarth said that only holding classic developed countries financially responsible for adaptation would be “a strong relapse into the old, divided world” of the Annex I countries of the Kyoto Protocol and all other countries. However, this world had been left behind at COP28, Flasbarth said.

Developing countries also need more clarity about the sub-goals and indicators. The current draft text states that the goal of the GGA is to make the health sector, water supply, food security, infrastructure and ecosystems more resilient to climate impacts, among other things. Poverty reduction is to be strengthened and cultural assets better protected. However, it does not contain any concrete figures used to measure progress. The African Group and the G77, in particular, will demand them.

A two-year work program is currently being discussed to define the sub-goals, indicators, and review mechanisms more precisely. Developing countries see this critically: Such a two-year work program existed before Dubai. However, they feel that its preparatory work yielded inadequate and late results.

Some observers also fear that another two-year work program will delay decisions on funding. The German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) disagrees: “The proposal for a two-year work program relates to the development of indicators for measuring progress towards the various goals. This technical work does not automatically stand in the way of the discussion in the NCQG,” a spokesperson said.

Lastly, there is also disagreement about whether the GGA should become a standing agenda item at climate conferences. It is currently not – which means that, in the worst case, there will always have to be a constant struggle to ensure that the adaptation target continues to be discussed.

In any case, a global adaptation target is needed, which will be adopted at the COP, said Christoph Bals, Policy Director at the NGO Germanwatch. “We will have to see how far we get with the criteria below that, because the negotiations have been so destructive.” It is possible that “at least key points and a work program are possible, so that we have a definitive agreement by next year.”

In 2024, the “long-promised doubling of adaptation funding would then have to be transparently verified,” and “a significant increase would have to be decided” as part of the new NCQG financial target. ” Such a process would be what is still possible here.”

Apart from the lack of an adequate translation of the words “abated” and “unabated” in many languages, the exact definition of the terms is also still unclear in English. Since the 2021 G7 energy ministers meeting in the UK, diplomats have struggled to find the right wording concerning fossil fuels. At COP26 in Glasgow in the same year, when the decision was made to reduce unabated coal-fired power generation, the terms also found their way into the UN climate negotiations.

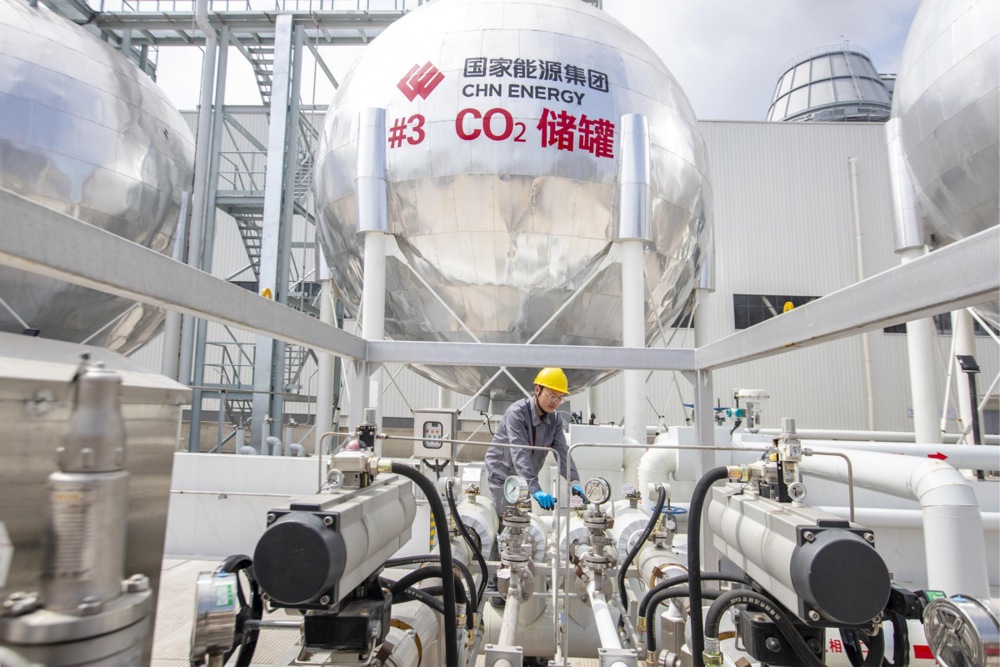

Negotiations in Dubai focus on fossil fuels – always with the question: is there a “phase-down/out” of fossil fuels or is the word “unabated” still in front of it? Most countries see “abatement” in the broadest sense as capturing carbon dioxide from the combustion of fossil fuels. Most greenhouse gases would not escape into the atmosphere and would not accelerate climate change. Instead, they would be captured technologically during combustion and stored or used (CCSU). The International Energy Agency (IEA) also uses this definition.

However, not everyone agrees on this use of the word. Japan, after all, is a G7 member and one of the countries with the highest global greenhouse gas emissions. It already considers its coal-fired power plants with partial ammonia co-firing as reduced fossil energy production. This does not necessarily include the use of CCS and coal would continue to be burned – only in “reduced” quantities and with fewer emissions due to ammonia firing.

US climate envoy John Kerry, a well-known fan of CCS, also vaguely defines the term. He sees reduction as achieving the Paris goals. However, Kerry also admits that it means “different things to different people” and that countries’ intentions are different.

It is not only the term “abatement” that is currently still undefined. The EU demand for an energy system “predominantly free of fossil fuels” is also not clearly defined. To some – including Germany – “predominantly” means close to 100 percent – meaning that CCS should only be used for residual emissions from hard-to-decarbonize industrial sectors. Others simply see “predominantly” as the majority – i.e., everything over 50 percent.

Alden Meyer, Senior Associate and climate policy expert at think tank E3G demands that the term be defined as quickly as possible. If everyone is left to decide for themselves what “abatement” means, then it would be “Wild West.” The risk is all the greater that vaguely defined reduction options distract from real emission reductions. His proposal: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the IEA present a generally valid definition by COP29 next year on which everyone can agree.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has already made a start. A footnote in the IPCC report from 2022 mentions a reduction rate through “abatement” of at least 90 percent for power plants and 50 to 80 percent for fugitive methane emissions. This refers to the entire life cycle of fossil fuels. This definition would mean that emissions from transportation and upstream emissions would also be considered. This would particularly limit backdoors for methane emissions considerably. A study by IPCC authors goes even further and recommends the term “abatement” only for carbon reductions of 90 to 95 percent and guaranteed permanent underground carbon storage.

It would almost entirely rule out the use of CCS for oil products, as most of the emissions are produced during local combustion, for example, in non-electric cars. There, carbon capture is hardly possible and, above all, not profitable. And LNG would hardly have a future if the IPCC footnote for “abatement” were universally valid. Only ten percent of emissions are generated during the production of LNG, around 90 percent during combustion by consumers.

However, defining “abated” for all countries could be extremely difficult. Even the footnote in the IPCC report was highly controversial during the coordination process with the governments of the signatory states. However, if the term cannot be clearly defined, this could result in enormous carbon backdoors.

With a capture rate of only 50 percent instead of 95 percent and excluding upstream methane emissions, 86 billion tons more greenhouse gases would be emitted by 2050. This is according to a study by Climate Analytics. This means that if the definition of “unabated fossil fuels” is unclear, twice the global carbon emissions of 2023 could end up in the atmosphere in the worst-case scenario.

A clear definition could simplify the climate negotiations. If all governments knew what is still allowed through “abatement,” the positions would be clearer. However, the countries preventing a clear definition are the same that oppose the fossil fuel phase-out.

Click here for all previously published COP28 articles.

Dec. 11, 10 a.m., The Women’s Pavilion – Humanitarian Hub

Panel discussion Greening the Humanitarian Response: A Sustainable Resilient and Accountable Approach in Displacement Settings

The side-event Greening the humanitarian response: A sustainable, resilient and accountable approach in displacement settings will explore how various climate-related initiatives within the humanitarian context can collectively address challenges related to natural resource management, mitigate multiple risks, ensure energy access, and navigate the complexities of displacement. Info

Dec. 11, 11 a.m., Panda Hub

Discussion Greening the chain – Towards sustainability along the steel supply chain

The steel industry is responsible for around seven percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Production is expected to continue to rise until 2050, meaning that emissions per tonne of steel must fall rapidly. high-level Government representatives will share their experiences of and views on Government action. The event will be co-hosted by WWF Australia, WWF Namibia and WWF India. Info

Dec. 11, 11:30 a.m., SE Room 8

Panel discussion The transformative power of law in promoting a just transition to a climate positive world

Law can contribute to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement and a just transition to a climate-friendly world. This event will discuss legal issues related to the climate agenda, including legal aspects of implementing nature-based solutions and human rights-based approaches. Info & Livestream

Dec. 11, 11:30 a.m., European Pavilion

Panel discussion Building climate neutral and resilient cities: a journey to implementation

Mayors from inspiring cities of the Global Covenant of Mayors – the world’s largest city alliance, will highlight their Climate Action Plans at all stages of their climate journey, outlining their transformative and inclusive local vision. This event is a unique opportunity to hear from local leaders on their mission to tackle change. Be part of the story of local action delivering global change. Info

Dec. 11, 3 p.m., SE Room 3

Discussion Just Industry Transition Partnerships – A proposal to link JETPs with sectoral cooperation

The discussion will focus on how countries in the Global South could also be better supported in the decarbonization of industry by expanding the concept of Just Energy Transition Partnerships. Info & Livestream

More than three billion US dollars have been pledged for the agriculture and food sector since the start of the COP. This figure does not include all the money that could flow into the sector. For example, the public-private partnership Africa and Middle East SAFE Initiative pledged an additional ten billion. These are to be leveraged from private capital, among other sources. SAFE stands for Scale-up Agriculture and Food Systems for Economic Development and the billions are to flow into food security and livelihoods in rural areas, among other things. The Global Green Growth Institute will coordinate the initiative.

The challenges for food and climate change are enormous: According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), disasters such as floods and droughts have caused 3.8 trillion dollars in crop and livestock losses over the last three decades. To maintain food security, research into climate-resistant plants is necessary. In addition, the sector’s high emissions are also to be reduced.

Analyses by the Climate Policy Initiative reveal a significant funding gap for the agri-food sector. While more than 500 billion US dollars went into the transformation of energy systems in 2021-2022, only 43 billion went into agriculture, land use change, forests and fisheries in the same period. kul

The COP28 pledges made so far to triple renewables, double energy efficiency and reduce methane emissions are not reducing emissions fast enough. According to an IEA analysis, fully meeting the COP pledges would only close the emissions gap to the 1.5-degree pathway by just over 30 percent by 2030. The IEA analysis confirms a report by the Climate Action Tracker, which came to similar conclusions.

So far, over 130 countries have joined the initiative to triple renewable energies and double energy efficiency. India and China are not members. Although China is well on tripling its renewable energy capacity by 2030, it refuses to commit to doubling its energy efficiency. In addition, 50 oil and gas companies have joined forces in the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter to reduce methane emissions to almost zero by 2030. nib

Liu Zhenmin has big shoes to fill. The 68-year-old will most likely become China’s new climate envoy and thus succeed climate czar Xie Zhenhua, who made a significant contribution to the Paris Climate Agreement with John Kerry. As a grey eminence, Xie has had a great deal of influence on Chinese climate policy.

However, career diplomat Liu Zhenmin also has years of experience in climate issues and was able to look over Xie’s shoulder for many years. In 2015, he was involved in the negotiations on the Paris Climate Agreement as Xie’s deputy in the Chinese delegation. Liu also claims to have already attended COP2 to COP5. And Liu was involved in negotiating the Kyoto Protocol as head of the Chinese delegation.

He can look back on more than 30 years of diplomatic experience. Until 2022, he was Under-Secretary-General for Economic and Social Affairs at the United Nations. He was responsible for the 2030 Agenda, advised António Guterres on development policy and climate issues, and participated in climate conferences with Guterres.

As Under-Secretary-General, he emphasized the “great contribution” the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative could make to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This blending of Chinese interests and the sustainable development agenda was poorly received in the West. However, his repeated criticism of the financial sector’s pursuit of short-term profits and his calls to restructure the financial system should fall on open ears in the climate community.

From 2013 to 2017, Liu was China’s Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs. At the time, he refuted former US President Donald Trump’s accusation that climate change was a hoax invented by the Chinese to weaken the USA. His clever retort: It was the US Republicans who started the climate negotiations in the late 1980s.

Liu has a law degree from Beijing University. He was born in August 1955 in Shanxi province, China’s largest coal-mining region, and is married. He is considered less powerful and less well-connected than his predecessor Xie. Xie held the rank of minister, while Liu was only vice minister. Xie previously worked at the National Development and Reform Commission of China (NDRC), which plays a key role in determining China’s climate policy. According to the assessment of the consulting agency Trivium China, career diplomat Liu has fewer connections to the most important climate decision-makers in the Chinese government and Communist Party.

As UN Under-Secretary-General, Liu wrote, climate change “is a threat multiplier, with the potential to worsen some of humanity’s greatest challenges, including health, poverty, hunger, inequality.” At a conference in September 2023, Liu called for the faster implementation of national climate targets (NDCs), a COP28 decision on climate adaptation and he called on developed countries to fulfill their climate finance commitments. Liu believes that trade barriers should be prevented. Market forces could contribute to climate action – an allusion to current trade policy differences between China and Western countries and CBAM. Nico Beckert

COP28 is slowly approaching the finishing line. Yesterday, COP President Al Jaber urged countries to work “harder,” be more flexible and make compromises. He intends to conclude the conference at 11 a.m. on Tuesday. But on the COP’s corridors, the first bets have already been made on how long COP will go into overtime this year.

The most heated debate currently revolves around phasing out fossil fuels. Many countries want to focus on “abatement,” i.e., continuing to use fossil fuels while reducing emissions. However, there is no clear definition of what “abatement” actually means. Lukas Scheid describes why a clear definition and universally applicable standards could lead to a CO2 bomb.

There are also heated debates about a global goal for adaptation to the impacts of the climate crisis. Countries are still arguing about how adaptation can be measured, what concrete sub-goals could look like, who should contribute, and how much to their financing. Alexandra Endres has compiled the details.

Climate conferences could take on a completely different dynamic in the near future. Several studies have now found that developing and emerging countries have historically contributed the most to the climate crisis – at least in absolute figures, reports Bernhard Pötter. So far, developed countries have had a special obligation because they have long emitted the most historic and per capita emissions.

Amidst the final negotiations at COP, a controversial study shows that emerging and developing countries drive global warming more than developed countries and their historical emissions. This shakes a core narrative of the UN climate process. The matter is correspondingly uncomfortable for many countries.

The signs are changing on a central question of global climate policy: According to a new study published in the scientific journal Nature, the countries of the Global South have now contributed more to global warming through their greenhouse gas emissions than developed countries. According to the Framework Convention on Climate Change (“Annex I”), the developed countries’ share of historical contributions to global warming between 1851 and 2021 is 44.8 percent. In contrast, the share of emerging and developing countries (“non-Annex I”) is 53.5 percent. The results of the study are consistent with UN and IPCC data.

This challenges a core message that has dominated global climate diplomacy in recent decades: The narrative that developed countries are the main culprits of the climate crisis – and that the rest of the world has contributed little to it. For instance, the G77/China proposal for a Global Stocktake resolution at COP28 speaks of “historical gaps in implementation of mitigation actions” and the “historical responsibility of developed countries to take leadership in climate action.” The argument underlying many UN resolutions is that developed countries must step up their climate efforts and provide financial support to developing countries as they have emitted the most CO2 and have become richer on average thanks to this fossil-fuelled growth.

But the claim that the Global North has historically been the biggest polluter has now been clearly disproven. The new study shows this because it uses comprehensive data: In addition to carbon emissions from fossil fuel combustion, it also calculates those from land use and forest destruction, which are otherwise often overlooked. It also highlights the climate effects of methane and nitrogen oxide emissions. The individual findings:

The figures look different if only emissions from the use of fossil fuels are considered: Here, the classic developed countries still account for the majority of emissions at 54.1 percent. When it comes to warming caused by emissions from land use (LULUCF), on the other hand, emerging and developing countries are clearly in the lead with 73 percent.

The question regarding the contributions to emissions and global warming is so politically sensitive in the UNFCCC process that it is not a popular topic to discuss openly. A chart in the 6th IPCC Assessment Report, for example, shows historical emissions from fossil sources and land use by country group. Here, too, the classic developed countries in North America, Europe and Japan/Oceania only account for 43 percent. However, ten percent are assigned to the “Eastern Europe and Western Central Asia” group, which does not correspond to the UNFCCC Annex categories. This makes a clear statement about which countries in this group are Annex or non-Annex countries impossible, as is a clear categorization of emissions into developed or developing countries.

Yet the data in the current paper is clear. According to William Lamb, emissions expert at the MCC Berlin and author of IPCC and UNEP reports on the subject, who was not involved in the current study, the contributions to warming between the two groups started to overlap around 2009. “Since then, the share of non-annex countries in global warming has been higher than the historical contributions of developed countries.” In 2009, the COP15 in Copenhagen failed because the global North and South could not agree on who should reduce how many emissions. “The calculation and presentation of these figures at the IPCC and UNEP are a deeply political matter for the country delegations and are also negotiated in this way,” Lamb told Table.Media. There has yet to be a major political debate on this issue.

The latest Unep Emissions Gap Report also examines the gap in the necessary emissions reductions: In 2022, global greenhouse gas emissions reached an all-time high of 57.4 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent, with an increase of 1.2 percent. However, the report also lists historical emissions and connects them to other equally important aspects: In addition to the volume of historical emissions and the contribution to warming, it also presents the per capita emissions of countries and country groups, for example. If the historical emissions of the G20 countries are broken down into developed and emerging countries, the trend of developed countries becoming less important is also evident.

For instance, China has revised its demands in its proposals for incorporating the Global Stocktake into the COP resolutions. Instead of blaming developed countries for the climate crisis overall, China now argues:

This shifts the debate from a purely quantitative question to a qualified consideration of emissions: for example, per capita or per country’s economic output. However, this shifts global responsibilities.

Click here for all previously published COP28 articles.

Time is running out for the new Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), which is to be adopted in Dubai. The delegations only received a foundation on which to negotiate the content three days before the end of the climate summit. The draft was presented on Sunday at 8.30 a.m. local time. Previously, the presidency had intervened – apparently out of concern that the GGA could fall by the wayside.

There is now very little time for substantive work on the text. The framework for the GGA needs to be adopted in Dubai so that it can be fleshed out by next year’s climate summit as planned.

The main disputes revolve around:

The discussions on Sunday evening were apparently so deadlocked that the ministers decided to address the matter in particular. The Arab countries were still opposed to the overall COP package – they had previously blocked the adaptation negotiations tracks in order to stall overall progress. However, there were also disagreements between developed and developing countries on the GGA framework.

African countries had already introduced the adaptation goal into the UN negotiation process ten years ago, and it was then mentioned in writing for the first time in Article 7 of the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015: The goal is to enhance “adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change.”

This is mainly in the interests of countries more vulnerable to the climate crisis than others. However, according to German Development Secretary Jochen Flasbarth in Dubai on Sunday, developed countries must prepare for a future with even more climate extremes: “The Global Goal on Adaptation is not just aimed at developing countries. The world as a whole is to become more resilient.”

The GGA is intended to create the basis for this in the form of a framework. It is to include an overarching goal that is concretized by – preferably measurable – sub-goals as well as instruments for practical implementation, review procedures and, if necessary, readjustment, as well as financing. A working group had been working on this for two years. It only presented some formulation proposals shortly before Dubai. This was another factor that slowed down the start of the GGA negotiations at COP28.

It will now be difficult to reach an agreement in time. One sticking point is funding. The more the climate crisis progresses the more the need for money for adaptation increases. The consequences of global warming are already more severe than expected, as the IPCC’s latest assessment report shows. However, instead of increasing, public funding for adaptation has recently decreased by 15 percent to 21 billion US dollars annually.

“It is about saving lives,” said Mohamed Adow, Director of the NGO Power Shift Africa, in Dubai, referring to the UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report, which estimates future financing needs for adaptation at 387 billion US dollars annually. According to negotiating circles, there was also a reference to the figure in an initial GGA draft text in Dubai. However, it is now absent from Sunday’s text.

It would be particularly important for developing countries to have concrete figures anchored in the GGA, as this would link funding very clearly to adaptation purposes. Adow warns of a “humanitarian crisis” if adaptation funding does not increase. The current GGA draft text falls short, he says. A GGA framework must be adopted in Dubai that gives vulnerable countries the necessary confidence “that they will receive sufficient financial support to adapt.”

However, unlike the developing countries, the developed countries would prefer to anchor adaptation financing in other negotiation tracks. One option would be in the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG), which will be adopted at the COP next year.

Another disputed demand is to stipulate in the GGA which countries should pay for adaptation. Among others, Germany is in favor of this. Adaptation funding “from classic donor countries” will increase from 20 billion in 2019 to 40 billion in 2025, said German State Secretary for Development Jochen Flasbarth in Dubai on Sunday. “That has already been decided. We stand by it.” A BMZ spokesperson said in response to a question about how the financing will look after 2025 in view of the increasing climate risks.

Flasbarth said that only holding classic developed countries financially responsible for adaptation would be “a strong relapse into the old, divided world” of the Annex I countries of the Kyoto Protocol and all other countries. However, this world had been left behind at COP28, Flasbarth said.

Developing countries also need more clarity about the sub-goals and indicators. The current draft text states that the goal of the GGA is to make the health sector, water supply, food security, infrastructure and ecosystems more resilient to climate impacts, among other things. Poverty reduction is to be strengthened and cultural assets better protected. However, it does not contain any concrete figures used to measure progress. The African Group and the G77, in particular, will demand them.

A two-year work program is currently being discussed to define the sub-goals, indicators, and review mechanisms more precisely. Developing countries see this critically: Such a two-year work program existed before Dubai. However, they feel that its preparatory work yielded inadequate and late results.

Some observers also fear that another two-year work program will delay decisions on funding. The German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) disagrees: “The proposal for a two-year work program relates to the development of indicators for measuring progress towards the various goals. This technical work does not automatically stand in the way of the discussion in the NCQG,” a spokesperson said.

Lastly, there is also disagreement about whether the GGA should become a standing agenda item at climate conferences. It is currently not – which means that, in the worst case, there will always have to be a constant struggle to ensure that the adaptation target continues to be discussed.

In any case, a global adaptation target is needed, which will be adopted at the COP, said Christoph Bals, Policy Director at the NGO Germanwatch. “We will have to see how far we get with the criteria below that, because the negotiations have been so destructive.” It is possible that “at least key points and a work program are possible, so that we have a definitive agreement by next year.”

In 2024, the “long-promised doubling of adaptation funding would then have to be transparently verified,” and “a significant increase would have to be decided” as part of the new NCQG financial target. ” Such a process would be what is still possible here.”

Apart from the lack of an adequate translation of the words “abated” and “unabated” in many languages, the exact definition of the terms is also still unclear in English. Since the 2021 G7 energy ministers meeting in the UK, diplomats have struggled to find the right wording concerning fossil fuels. At COP26 in Glasgow in the same year, when the decision was made to reduce unabated coal-fired power generation, the terms also found their way into the UN climate negotiations.

Negotiations in Dubai focus on fossil fuels – always with the question: is there a “phase-down/out” of fossil fuels or is the word “unabated” still in front of it? Most countries see “abatement” in the broadest sense as capturing carbon dioxide from the combustion of fossil fuels. Most greenhouse gases would not escape into the atmosphere and would not accelerate climate change. Instead, they would be captured technologically during combustion and stored or used (CCSU). The International Energy Agency (IEA) also uses this definition.

However, not everyone agrees on this use of the word. Japan, after all, is a G7 member and one of the countries with the highest global greenhouse gas emissions. It already considers its coal-fired power plants with partial ammonia co-firing as reduced fossil energy production. This does not necessarily include the use of CCS and coal would continue to be burned – only in “reduced” quantities and with fewer emissions due to ammonia firing.

US climate envoy John Kerry, a well-known fan of CCS, also vaguely defines the term. He sees reduction as achieving the Paris goals. However, Kerry also admits that it means “different things to different people” and that countries’ intentions are different.

It is not only the term “abatement” that is currently still undefined. The EU demand for an energy system “predominantly free of fossil fuels” is also not clearly defined. To some – including Germany – “predominantly” means close to 100 percent – meaning that CCS should only be used for residual emissions from hard-to-decarbonize industrial sectors. Others simply see “predominantly” as the majority – i.e., everything over 50 percent.

Alden Meyer, Senior Associate and climate policy expert at think tank E3G demands that the term be defined as quickly as possible. If everyone is left to decide for themselves what “abatement” means, then it would be “Wild West.” The risk is all the greater that vaguely defined reduction options distract from real emission reductions. His proposal: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the IEA present a generally valid definition by COP29 next year on which everyone can agree.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has already made a start. A footnote in the IPCC report from 2022 mentions a reduction rate through “abatement” of at least 90 percent for power plants and 50 to 80 percent for fugitive methane emissions. This refers to the entire life cycle of fossil fuels. This definition would mean that emissions from transportation and upstream emissions would also be considered. This would particularly limit backdoors for methane emissions considerably. A study by IPCC authors goes even further and recommends the term “abatement” only for carbon reductions of 90 to 95 percent and guaranteed permanent underground carbon storage.

It would almost entirely rule out the use of CCS for oil products, as most of the emissions are produced during local combustion, for example, in non-electric cars. There, carbon capture is hardly possible and, above all, not profitable. And LNG would hardly have a future if the IPCC footnote for “abatement” were universally valid. Only ten percent of emissions are generated during the production of LNG, around 90 percent during combustion by consumers.

However, defining “abated” for all countries could be extremely difficult. Even the footnote in the IPCC report was highly controversial during the coordination process with the governments of the signatory states. However, if the term cannot be clearly defined, this could result in enormous carbon backdoors.

With a capture rate of only 50 percent instead of 95 percent and excluding upstream methane emissions, 86 billion tons more greenhouse gases would be emitted by 2050. This is according to a study by Climate Analytics. This means that if the definition of “unabated fossil fuels” is unclear, twice the global carbon emissions of 2023 could end up in the atmosphere in the worst-case scenario.

A clear definition could simplify the climate negotiations. If all governments knew what is still allowed through “abatement,” the positions would be clearer. However, the countries preventing a clear definition are the same that oppose the fossil fuel phase-out.

Click here for all previously published COP28 articles.

Dec. 11, 10 a.m., The Women’s Pavilion – Humanitarian Hub

Panel discussion Greening the Humanitarian Response: A Sustainable Resilient and Accountable Approach in Displacement Settings

The side-event Greening the humanitarian response: A sustainable, resilient and accountable approach in displacement settings will explore how various climate-related initiatives within the humanitarian context can collectively address challenges related to natural resource management, mitigate multiple risks, ensure energy access, and navigate the complexities of displacement. Info

Dec. 11, 11 a.m., Panda Hub

Discussion Greening the chain – Towards sustainability along the steel supply chain

The steel industry is responsible for around seven percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Production is expected to continue to rise until 2050, meaning that emissions per tonne of steel must fall rapidly. high-level Government representatives will share their experiences of and views on Government action. The event will be co-hosted by WWF Australia, WWF Namibia and WWF India. Info

Dec. 11, 11:30 a.m., SE Room 8

Panel discussion The transformative power of law in promoting a just transition to a climate positive world

Law can contribute to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement and a just transition to a climate-friendly world. This event will discuss legal issues related to the climate agenda, including legal aspects of implementing nature-based solutions and human rights-based approaches. Info & Livestream

Dec. 11, 11:30 a.m., European Pavilion

Panel discussion Building climate neutral and resilient cities: a journey to implementation

Mayors from inspiring cities of the Global Covenant of Mayors – the world’s largest city alliance, will highlight their Climate Action Plans at all stages of their climate journey, outlining their transformative and inclusive local vision. This event is a unique opportunity to hear from local leaders on their mission to tackle change. Be part of the story of local action delivering global change. Info

Dec. 11, 3 p.m., SE Room 3

Discussion Just Industry Transition Partnerships – A proposal to link JETPs with sectoral cooperation

The discussion will focus on how countries in the Global South could also be better supported in the decarbonization of industry by expanding the concept of Just Energy Transition Partnerships. Info & Livestream

More than three billion US dollars have been pledged for the agriculture and food sector since the start of the COP. This figure does not include all the money that could flow into the sector. For example, the public-private partnership Africa and Middle East SAFE Initiative pledged an additional ten billion. These are to be leveraged from private capital, among other sources. SAFE stands for Scale-up Agriculture and Food Systems for Economic Development and the billions are to flow into food security and livelihoods in rural areas, among other things. The Global Green Growth Institute will coordinate the initiative.

The challenges for food and climate change are enormous: According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), disasters such as floods and droughts have caused 3.8 trillion dollars in crop and livestock losses over the last three decades. To maintain food security, research into climate-resistant plants is necessary. In addition, the sector’s high emissions are also to be reduced.

Analyses by the Climate Policy Initiative reveal a significant funding gap for the agri-food sector. While more than 500 billion US dollars went into the transformation of energy systems in 2021-2022, only 43 billion went into agriculture, land use change, forests and fisheries in the same period. kul

The COP28 pledges made so far to triple renewables, double energy efficiency and reduce methane emissions are not reducing emissions fast enough. According to an IEA analysis, fully meeting the COP pledges would only close the emissions gap to the 1.5-degree pathway by just over 30 percent by 2030. The IEA analysis confirms a report by the Climate Action Tracker, which came to similar conclusions.

So far, over 130 countries have joined the initiative to triple renewable energies and double energy efficiency. India and China are not members. Although China is well on tripling its renewable energy capacity by 2030, it refuses to commit to doubling its energy efficiency. In addition, 50 oil and gas companies have joined forces in the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter to reduce methane emissions to almost zero by 2030. nib

Liu Zhenmin has big shoes to fill. The 68-year-old will most likely become China’s new climate envoy and thus succeed climate czar Xie Zhenhua, who made a significant contribution to the Paris Climate Agreement with John Kerry. As a grey eminence, Xie has had a great deal of influence on Chinese climate policy.

However, career diplomat Liu Zhenmin also has years of experience in climate issues and was able to look over Xie’s shoulder for many years. In 2015, he was involved in the negotiations on the Paris Climate Agreement as Xie’s deputy in the Chinese delegation. Liu also claims to have already attended COP2 to COP5. And Liu was involved in negotiating the Kyoto Protocol as head of the Chinese delegation.

He can look back on more than 30 years of diplomatic experience. Until 2022, he was Under-Secretary-General for Economic and Social Affairs at the United Nations. He was responsible for the 2030 Agenda, advised António Guterres on development policy and climate issues, and participated in climate conferences with Guterres.

As Under-Secretary-General, he emphasized the “great contribution” the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative could make to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This blending of Chinese interests and the sustainable development agenda was poorly received in the West. However, his repeated criticism of the financial sector’s pursuit of short-term profits and his calls to restructure the financial system should fall on open ears in the climate community.

From 2013 to 2017, Liu was China’s Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs. At the time, he refuted former US President Donald Trump’s accusation that climate change was a hoax invented by the Chinese to weaken the USA. His clever retort: It was the US Republicans who started the climate negotiations in the late 1980s.

Liu has a law degree from Beijing University. He was born in August 1955 in Shanxi province, China’s largest coal-mining region, and is married. He is considered less powerful and less well-connected than his predecessor Xie. Xie held the rank of minister, while Liu was only vice minister. Xie previously worked at the National Development and Reform Commission of China (NDRC), which plays a key role in determining China’s climate policy. According to the assessment of the consulting agency Trivium China, career diplomat Liu has fewer connections to the most important climate decision-makers in the Chinese government and Communist Party.

As UN Under-Secretary-General, Liu wrote, climate change “is a threat multiplier, with the potential to worsen some of humanity’s greatest challenges, including health, poverty, hunger, inequality.” At a conference in September 2023, Liu called for the faster implementation of national climate targets (NDCs), a COP28 decision on climate adaptation and he called on developed countries to fulfill their climate finance commitments. Liu believes that trade barriers should be prevented. Market forces could contribute to climate action – an allusion to current trade policy differences between China and Western countries and CBAM. Nico Beckert