Petting piglets, sampling veggie sausages, driving tractors – this is what the “International Green Week” in Berlin means for hundreds of thousands of visitors. But at the world’s largest agricultural trade fair, serious matters are also discussed on stage and behind the scenes. For instance: Does bioenergy have a future in the energy transition? How can EU agricultural policy help reach climate goals? Lisa Kuner and Alexandra Endres have the answers in this Climate.Table.

But as always, we also look beyond our own backyard: With backgrounds on Japan’s G7 presidency, which lacks a climate focus; with the debate on whether Australia’s carbon offset mechanism further increases emissions instead of reducing them; with a surprisingly positive track record for US President Biden’s climate policy; and with an opinion piece on the overlooked dimension in environmental debates: Namely, that any progress requires recycling and less use of materials. And, as usual, with plenty of additional background information from the worlds of science, politics and business.

As always, we appreciate your comments, criticism and suggestions at climate@briefing.table.media.

The use of biofuels is becoming an increasingly volatile political issue. Associations are making serious accusations against Germany’s Environment Minister Lemke and Agriculture Minister Özdemir. Lemke is accused of being “responsible for failing to meet climate action targets in the transport sector,” the biofuel industry said on Wednesday. According to the associations, a plan by the Federal Ministry for the Environment “to gradually phase out biofuels from cultivated biomass” would make it impossible to achieve the climate targets in the transportation sector. On January 19, Lemke submitted a draft to stop government subsidies for biofuels to the departmental vote. The draft envisages a phase-out of biofuels from food crops and rapeseed in Germany by 2030.

So-called e-fuels are an indispensable element for immediately effective climate action, says Artur Auernhammer, Chairman of the German Bioenergy Association. Joachim Rukwied, President of the German Farmers’ Association, also said earlier this week that “politicians must get out of their ideological box. We can only achieve our greenhouse gas reduction quota if we add biofuels to the mix.”

The Deutsche Umwelthilfe (Environmental Action Germany) sees things quite differently and holds Volker Wissing responsible. The Minister of Transport should no longer block Lemke’s initiative. The “insanity” of state subsidies for biofuels must be “ended immediately,” says Sascha Müller-Kraenner, the CEO of Deutsche Umwelthilfe.

Why is bioenergy such a controversial topic? Where are the biggest disputes? So far, bioenergy in Germany has been used primarily in three forms:

The energy debate revolving around the war in Ukraine, the requirements of net zero, and the expiration of EEG subsidies are changing the bioenergy landscape.

The National Biomass Strategy (NABIS) is supposed to answer this question for Germany. Taking food security into account, it is intended to determine how biomass can make a sustainable contribution to the energy supply. The key points of NABIS were presented last fall. It includes the following guiding principles:

If the EU wants to become carbon-neutral by 2050, agriculture must also reduce its emissions as far down towards zero as possible. In Germany, the Climate Change Act sets reduction targets for the agricultural sector. And at the EU level, new, more climate-friendly regulations for the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) have been in force since the beginning of 2023.

The EU Commission calls the new rules the “most ambitious CAP ever from an environmental and climate perspective.” Accordingly, 40 percent of agricultural subsidies are “devoted to delivering benefits for the climate.”

But the target is not being met – at least in Germany. This is the conclusion of a study published by the German Environment Agency. In it, researchers from the Öko-Institut and the University of Rostock examined how climate-effective agricultural subsidies actually are.

The findings:

Just under eleven percent of the European Union’s greenhouse gas emissions originate from agriculture. That may not seem like much. But decarbonizing the agricultural sector is particularly difficult, says Pierre-Marie Aubert, Director of Agriculture and food policies at French sustainability think tank IDDRI: “It’s nearly impossible to get agricultural emissions to zero.”

That is not because of farmers’ lack of will, Aubert says. “It’s because we’re working with living organisms here.” The digestion process of cows releases methane, soils treated with nitrogen fertilizer emit nitrous oxide, and drained wetlands emit carbon dioxide. The climate-friendly transformation of agriculture is further complicated by the fact that climate protection cannot be viewed separately. Biodiversity conservation and food production would always have to be taken into account.

Since 2012, greenhouse gas emissions from the EU agricultural sector have been rising again, Aubert says. “Whatever farmers say, they are not doing enough.” Like other experts, he criticizes CAP reform as insufficient. Despite all the EU Commission’s pronouncements, he says, direct agricultural payments to farms are currently “barely linked to any climate conditions.”

To make agriculture more sustainable, Aubert recommends one thing above all: The number of farm animals must fall – not to zero, but drastically nonetheless. “That would be good for climate and species conservation, and we would still have enough to eat as it would reduce dramatically feed-food competition.”

The tricky part is that many people are employed in the livestock sector. According to Aubert, 40 to 50 percent of agricultural jobs depend on keeping livestock, and about 30 to 40 percent of jobs in the food industry, depending on the countries at the EU level.

In addition, Aubert says, policymakers should encourage wetland rewetting and more efficient nitrogen use. The authors of the UBA study come to similar conclusions. Relevant laws and regulations could be adapted “even in the short term,” they write. They also call for expanding “climate-relevant CAP measures and financial resources.” The current CAP funding period runs until 2027 when the next revision is due.

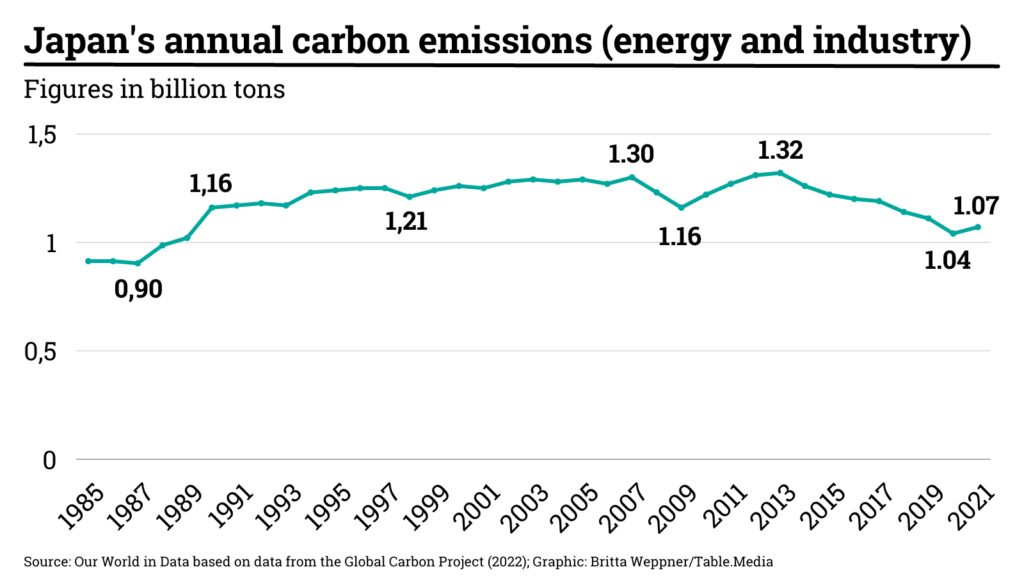

Shortly after assuming the G7 presidency, Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida visited France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States in preparation for the G7 summit in Hiroshima in May. The G7 accounts for 25 percent of global emissions but is historically responsible for 44 percent of greenhouse gases and as such, they bear a great deal of responsibility for climate change.

While climate was a topic in the meeting with global leaders, the Japanese prime minister rarely spoke about it. For him, it is one of many global issues. He did not make any concrete proposals. He seemed to characterize it as one of many global issues and did not specify his proposals during his visit

Kishida’s mind is occupied with national security, which is becoming increasingly severe with the war in Ukraine and Chinese hegemony, and with his personal agenda of nuclear arms abolition. Hiroshima is his hometown, where a nuclear bomb was used for the first time in history.

Japan once gaveled out the historical Kyoto Protocol, which made it legally binding to reduce emissions. However, post-Kyoto climate diplomacy of Japan has been lacking leadership, and much of it appears backward. At recent G7 meetings, Japan has argued differently from other countries, such as for the export of coal-fired power and against the phase-out of new gasoline cars.

Japan also has a unique interpretation of last year’s Leaders’ Communiqué. It committed to “achieving a fully or predominantly decarbonized power sector by 2035”. Ministers and officials in Japan explain “predominantly” means “at least half,” which shows the reluctance of phasing out fossil fuel-fired power even in the future.

In his speech at COP26 in Glasgow, Kishida said Japan will promote the transition to clean energy, especially in Asia, by converting existing thermal power plants to zero-emission using ammonia/hydrogen. But this technology would not yet prove to be economically feasible. NGOs awarded “Fossil of the day” to Japan, saying that his plan would not help to achieve the 1.5-degree goal.

Kishida skipped the COP27 – and instead launched the “Asia Zero Emissions Community Initiative” at the G20 summit in Indonesia, which was taking place at the same time. A Japanese government official said this initiative will be one of the highlights at the G7 meeting. “It is meaningless for only developed countries to compete with each other for climate targets. We must take care of the Global South. We need to launch something realistic”

However, Japan distanced itself from the “Climate Club” planned by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the “Just Energy Transition Partnerships” (JETP) with which the G7 wants to promote the energy transition in countries such as South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam. Although Japan is the leading nation in the JETP with Indonesia alongside the USA, the government is silent on the subject, for example also at COP27. The reason: JETPs aim to end fossil fuels in the energy sector, but Japan plans to prolong fossil fuels use back home and with the “Asia Zero” initiative.

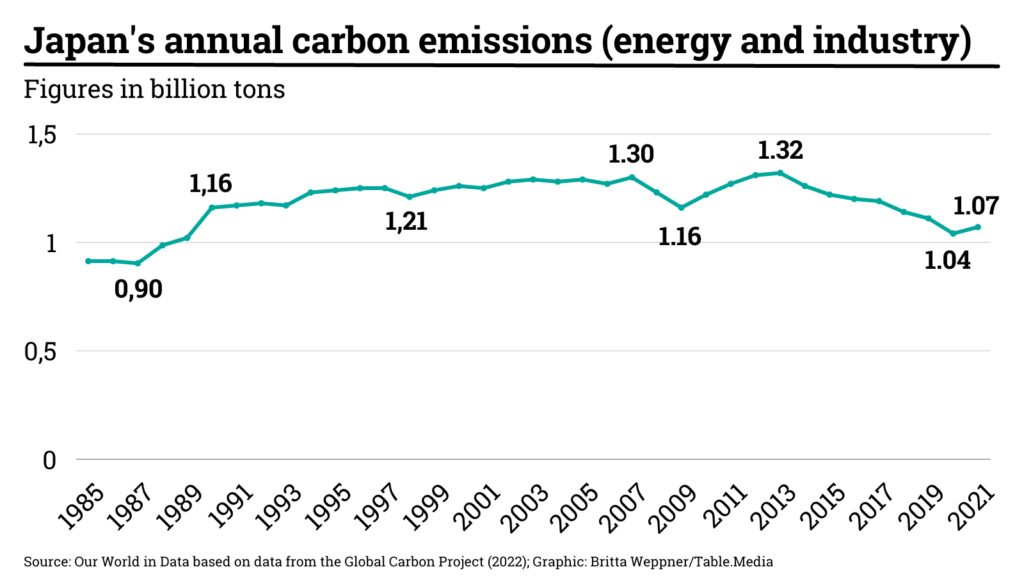

Japan has set the goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2050, reducing emissions by 46 percent by 2030. To achieve this, it is necessary to decarbonize the power sector, which as of FY2021 relies on fossil fuels for 73 percent of its electricity. The government has decided to increase renewable from 20 percent in FY2021 to 36-38 percent and nuclear from 6.9 percent to between 20 and 22 percent in the energy mix in 2030. However, this means that 40 percent of electricity will still be generated from fossil fuels in 2030, with almost half from coal. This largely filled the gap when Japan shut down 60 nuclear reactors in 2011 after the Fukushima nuclear accident.

Nuclear was the thorn in the side of Japan’s climate and energy policy. It divided public opinion. But with energy prices rising and energy supplies recently uncertain, polls now show a majority in favor of restarting the nuclear program for the first time. The government announced a plan to extend the operating life of reactors to 60 years and the development of new reactor types. Kishida had not mentioned this during the election campaign.

At the end of last year, the government proposed the basic policy of “Green Transformation.” It calls for “a shift from the fossil energy-centered industrial and social structure to a focus on clean energy,” but rather an emphasis on energy security. A return to nuclear power is included. It has laid out transition roadmaps for 22 areas, including hydrogen/ammonia, batteries, steel, and automobiles. To achieve this, the government plans to invest over 150 trillion yen (about one trillion euros). 20 trillion yen, about 140 billion euros, in new public bonds are to be issued. And it will be repaid through carbon pricing, including a levy on fossil fuel importers starting in 2028, and emissions trading among electric power companies.

NGOs are against government policy, saying that it will further increase dependence on nuclear and coal. In preparation for the G7, 350.org Japan sent a letter to the government. It called for “placing the climate crisis and energy issues on the key agenda.” And criticizing the Government’s reliance on technologies such as next-generation nuclear power, carbon capture and storage (CCS/CCUS), and ammonia/hydrogen co-firing of fossil fuels with thermal power as “false solutions,” they call for “steering away from fossil fuels in their true nature” By Keisuke Katori from Tokyo

In mid-January, the Australian federal government issued a report defending its own climate protection programme against criticism that the national CO2 offset mechanism hardly contributes to climate protection. This contradicts critics and whistleblowers. They claim that the program not only does not reduce emissions, it actually increases them, a criticism they continue to maintain. Whether Australia’s national offset mechanism for voluntary CO2 certificates is credible and effective remains hotly disputed.

Whistleblower and regulatory and environmental markets expert Andrew Macintosh, former head of the government’s Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee and now professor of environmental law at the Australian National University, published a series of reports. He found that at least 70 percent of the annual Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) – over 10 to 12 million tonnes of CO2 – did not deliver any actual or additional emissions reductions.

The ACCU is an important part of Australia’s climate protection policy known as The Safeguard Mechanism which essentially places caps (‘baselines’) on the country’s biggest emitters. It is intended to reduce emissions by requiring companies that do not meet their baseline to purchase offsets – carbon abatement credits in other areas of the economy – to account for the amount of emissions that exceed the agreed limit.

The government responded with the Chubb Report, which has now been presented. It was named after former chief scientist Ian Chubb. Their findings:

Ultimately, the Chubb panel rejected Macintosh’s claims that “the integrity of the system has been called into question”, that “the extent of emission reductions has been overstated”. The Chubb Panel admitted it had been presented with “some evidence supporting this view, but also evidence to the contrary”.

The government feels vindicated: In a press conference on Monday, climate change minister Chris Bowen said the system was “not as broken as has been claimed” and “fundamentally sound“.

The Chubb report is not transparent on a number of points: for example, it does not present the evidence to which it refers. It also does not address any of Macintosh’s criticisms of the integrity of the system. He, in turn, is disappointed: “The main section on these key methods is only five pages long, and it doesn’t address any of these issues. Is that good scientific practice? Not at all.”

Critics claim that many regeneration projects would have received CO2 credits without actually planting forests – or for regeneration that would have taken place anyway. Macintosh and his research team estimate that 165 projects have received CO2 credits for a total of 24.5 million Australian dollars, even though forest and replacement woody vegetation has declined by more than 60 000 hectares in total.

For Macintosh, the Chubb report did more harm than good because it fuelled industry opposition to voluntary certificates. “What we all wanted was an integrated system and there is a great opportunity to achieve that. We have a new government and a new emissions trading scheme to be introduced. The carbon markets have a great opportunity to deliver really good environmental outcomes. But if we don’t get all these things right, they will be lost.”

Don Butler, Chief Scientist in Queensland’s Land Restoration Fund and Professor of Law at the Australian National University whose work with Macintosh has challenged the Australian offsetting initiative, also says that “the administration of the method is a failure”. There are “obvious ways in which offsets can work, but at the systems level there seems to be some kind of failure globally“, he says. “It’s a complicated area where no one but the regulator has a strong interest in the integrity of the outcome,” he says.

The critics’ fear: The outcome of the Chubb review could bring higher emissions and formalise government greenwashing for fossil fuels. Only a small number of carbon credit developers would earn money from this.

Polly Hemming of the public policy think tank, The Australia Institute says: “The safeguard mechanism is not designed to drive decarbonisation. It’s designed to protect fossil fuels and funnel money to commercial carbon credit developers.”

Following Bowen’s statements, critics fear the allowances could guarantee the continued expansion of oil, gas and coal because they supposedly ‘offset’ their emissions. Australia currently has 114 new fossil fuel projects under development, including 72 new coal projects, 44 new gas and oil projects and several new gas basins which are actively supported by state and federal governments, including through large government subsidies. These projects would more than double Australia’s gas and coal production and introduce around 1.4 billion additional tonnes of CO2 emissions per year.

Jan. 31; 9.30 a.m., Online

Discussion Mercosur Trade Agreement – Will 2023 be the year it is finally ratified?

EU experts discuss the ratification of the EU-Mercosur agreement at EURACTIV’s event. Among other things, the agreement has not yet been able to enter into force due to sustainability concerns. Info and registration

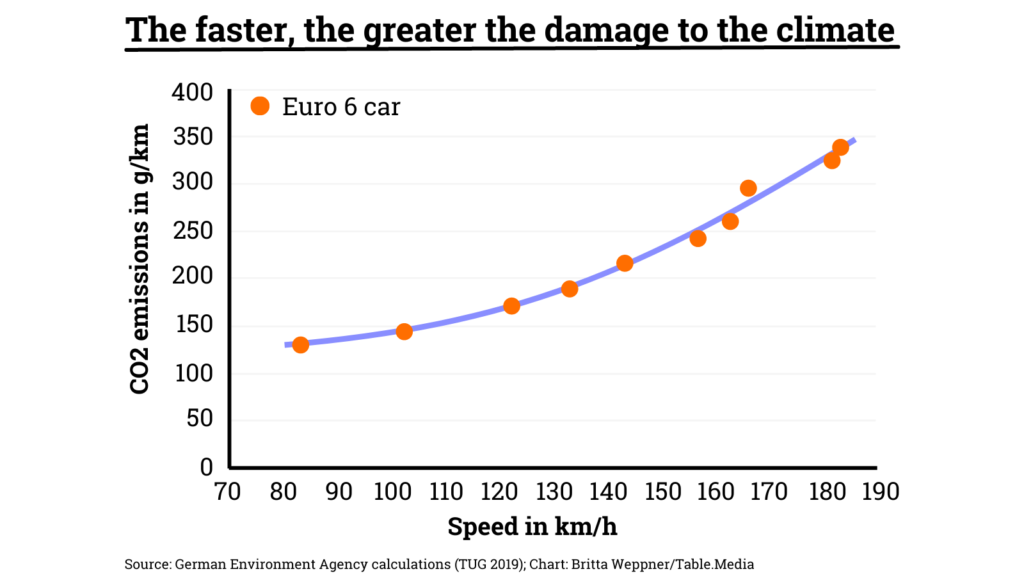

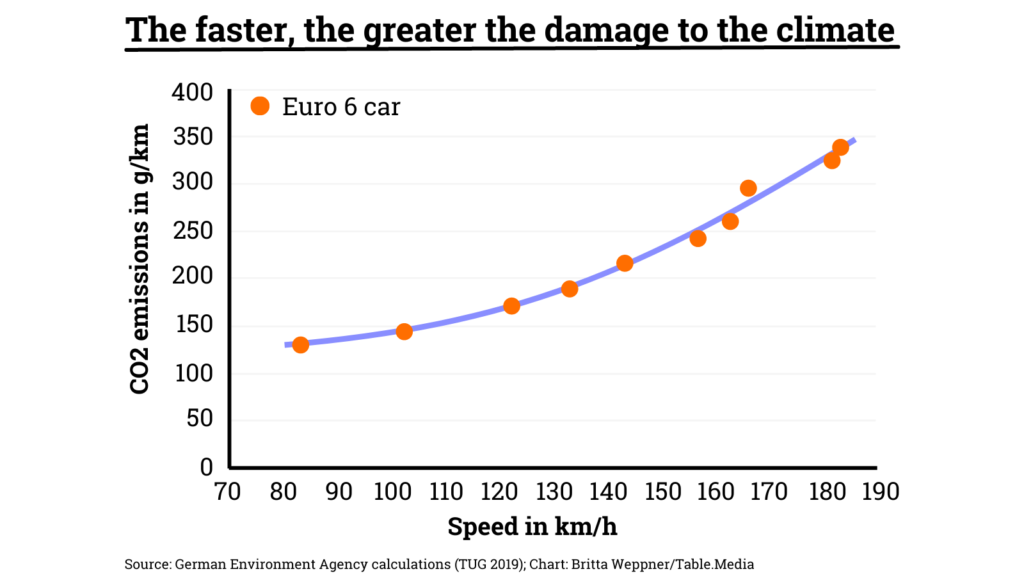

A speed limit of 120 km/h on highways and 80 km/h on country roads could save around 47 million metric tons of CO2 by 2030, according to new calculations by the German Environment Agency. This means that the climate mitigation effect of limiting the maximum permitted speed would be much more effective than previously thought. This is because emissions from internal combustion engines increase significantly above 130 km/h. The agency already pointed this out in 2020. nib

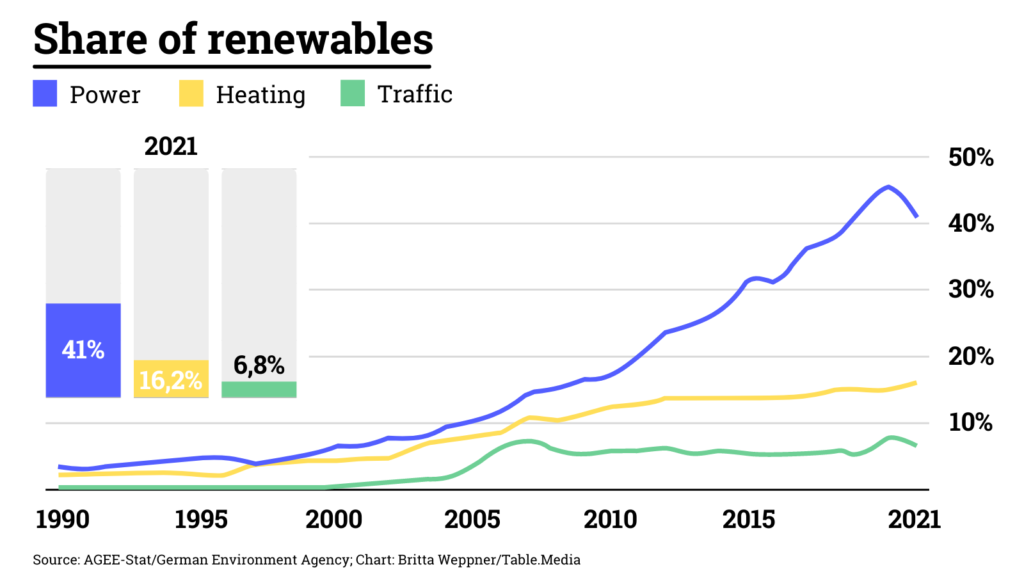

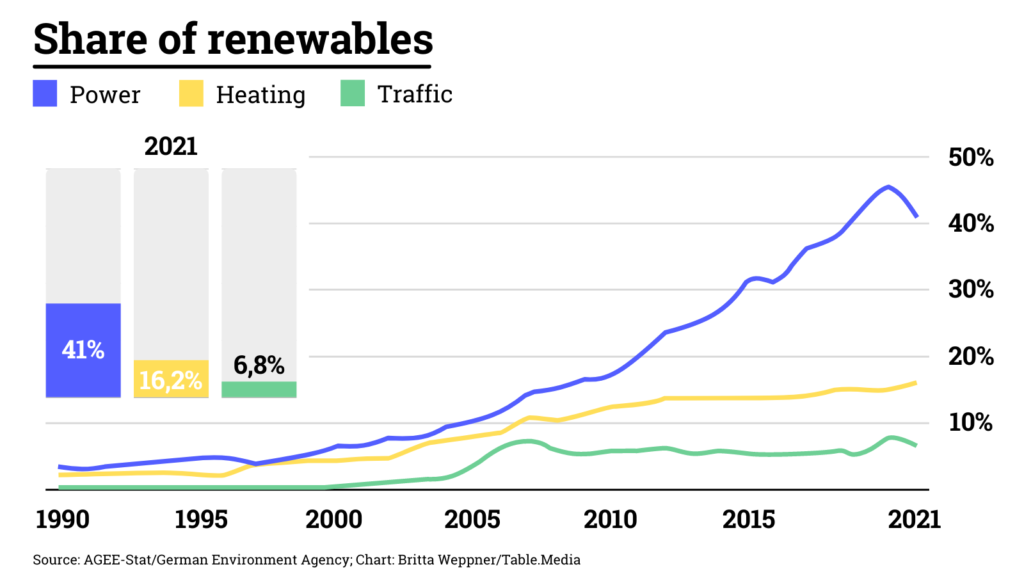

The heads of Germany’s five major environmental associations have joined the debate on energy security with far-reaching compromise proposals on the expansion of renewables. In a thesis paper entitled “Ein Booster für erneuerbare und grüne Infrastruktur” (A booster for renewable and green infrastructure), which Climate.Table has obtained in advance, they propose measures for a faster expansion of wind and solar energy, better funding for municipalities, and systemic safeguarding of nature conservation areas.

The authors of the paper are Kai Niebert (DNR), Jörg-Andreas Krüger (Nabu), Olaf Bandt (BUND), Martin Kaiser (Greenpeace) and Christoph Heinrich (WWF). The paper is a joint work by these association heads and has not been coordinated within their respective organizations. It has, therefore, not yet been distributed by their associations. Some of the proposals go beyond what is currently feasible within the associations.

The initiators reportedly presented the letter to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the relevant ministries. “The government has asked us for concrete proposals for the nature-compatible and accelerated expansion of renewable energies,” Kai Niebert told Climate.Table. “We hereby submit these ideas.”

Above all, the five association leaders propose:

The paper is to be issued in the next few days as a discussion basis. Among other things, the heads of the eco-associations want to use it to enter the current debate on whether, for example, road and highway planning should also be classified as “paramount public interest”. bpo

After two years in office, US President Joe Biden has been given a very good climate rating by the US think tank World Resources Institute. In a blog post, WRI Director Dan Lashof praised the Democratic president’s efforts. This means that the score has improved dramatically compared to last year – primarily due to the gigantic IRA investment program, which earmarks almost $370 billion for the expansion of green industries and infrastructure. “Congress finally delivered transformative legislation to tackle the climate crisis.”

The think tank praises Biden’s administration in particular for:

The WRI also sees “significant progress”:

WRI sees “some progress”:

The WRI does not see the government on the right track:

According to a report commissioned by Environmental Action Germany (DUH), the climate damage caused by imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) is massively underestimated. LNG imports from the USA fare particularly poorly. Here, methane leaks from fracking are particularly high. In some cases, methane losses of over ten percent occur. Gas production in Algeria and Nigeria leads to methane losses of over six percent of the gas produced. Norwegian pipeline gas has the lowest methane emissions. However, the data situation is “unsatisfactory almost everywhere” because methane emissions from the gas and oil industry have been neglected for a long time, the authors said.

Although climate gas has a shorter lifespan, it is about 80 times more harmful to the climate than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. According to DUH, methane leaks are more climate-damaging than burning gas for energy. The NGO calls to stop ignoring the “climate damage in the upstream chain of our gas supply.” “As long as we use natural gas that is harmful to the climate, the federal government [Germany] and companies must at least select the gas sources with the lowest emissions,” says DUH CEO Sascha Müller-Kraenner. nib

When asked what financial damage one ton of emitted carbon dioxide (CO2) causes, the German Federal Ministry of Transport gives very different answers. In its calculation of the economic benefit of investments in local rail transport, Volker Wissing’s (FDP) ministry drastically raised this figure last summer in order to better justify projects. Instead of the previous figure of €149, the climate damage per ton of CO2 is now set at €670. This means that, mathematically speaking, saving CO2 has become four-and-a-half times more valuable. The new value is even significantly greater than the carbon price demanded by Fridays for Future. The German Federal Environment Agency (UBA) calculates this higher value by valuing the damage caused by carbon emissions for future generations at the same level as for the current generation. This is not the case with currently used values.

This change allows the German government to co-finance more regional rail projects. This is only possible if the so-called “Standardized Assessment” indicates an economic benefit – and this is, of course, more likely to be the case if the reduction in CO2 emissions is worth more than it has been in the past. In particular, co-funding for the electrification of rail lines with low tunnels, which in the past often fell just short of the economic viability mark because of the high construction costs involved in enlarging tunnels, has been easier since. “When assessing economic viability, the factors of climate and environmental protection, modal shift and services of general interest, for example, now carry more weight,” Wissing explained last summer. And, “That is in keeping with the times.”

In long-distance transport, however, the German government’s calculations are not yet as “up-to-date”. Here, the federal government’s investments are based on the Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan – and this still puts the financial loss per ton of CO2 at just €145. This makes road projects seem more economical, while rail projects seem less so. The Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport has not yet decided whether the higher UBA value should also be used here in the future. One argument against the change is that planning security would be jeopardized if the currently valid transport infrastructure plan were changed. The argument in favor is that it is hard to imagine why a ton of carbon dioxide saved in local traffic should prevent four and a half times as much damage as in long-distance traffic. mkr

The European Central Bank (ECB) has unveiled statistical indicators to better analyze climate-related risks in the financial sector and monitor the green transition. “The indicators are a first step to help narrow the climate data gap, which is crucial to make further progress towards a climate-neutral economy,” said ECB Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel.

Risk indicators include sustainable financial instruments, carbon emissions from financial institutions, and physical risks from loan and securities portfolios.

“The experimental indicators on sustainable finance provide time-series information on outstanding amounts and financial transactions relating to issuances and holdings of sustainable debt instruments”. This is intended to help analysts understand both the financing needs of sustainable projects and the demand for these debt instruments as investment opportunities.

According to the ECB, the indicators for carbon emissions financed by the financial sector and the associated risks for the transition to a net zero economy cover two aspects: Total emissions financed by the financial sector and the financial sector’s involvement in emissions-intensive business. The indicators are intended to help analyze and assess the role of the financial sector in financing carbon-intensive business activities.

For this purpose, the financed emissions are considered in relation to total company value, as well as the carbon intensity of the product.

The ECB defines physical risks as consisting of three elements: Physical hazards, for example, to infrastructure, asset vulnerability and asset susceptibility to these hazards. The indicators are intended to assess the level of risk in individual portfolios and the expected losses.

The impact of natural events caused by climate change on the financial system is to be quantified using historical data and forecasts. In particular, the ECB focuses on natural events that have historically caused the greatest damage in the EU or that are projected to increase in the future. Climate-related natural events that have a more indirect impact on human health – heat waves, for example – are not yet included in this set of indicators. luk

It was a central campaign promise of Colombia’s leftist President Gustavo Petro to stop issuing new oil and gas licenses. But it now seems doubtful that he will be able to keep it. As the Guardian, among others, reports, there is also strong opposition within the government.

Petro has only a slim majority in parliament. In addition, according to the Guardian, an “increasingly bleak economic outlook and a series of policy U-turns from the government have put Petro’s ambitious environmentally friendly pledge in doubt”.

Colombia’s Energy and Mines Minister Irene Vélez confirmed Petro’s plans at the World Economic Forum in Davos: The government will no longer issue new oil and gas licenses, she said. The decision may be controversial, she said, but it is “a clear sign of our commitment in the fight against climate change.” She urged that immediate action be taken.

Petro backed his minister. During the election campaign, he had already announced plans to restructure the country’s economy in a “productive, but no longer extractivist” way. He intends to turn the domestic oil company Ecopetrol into a “major supplier of clean energy for Colombia and Latin America.

So far, Colombia’s economy and national budget have been heavily dependent on fossil fuels. The oil sector generates about one-third of the country’s export revenues, contributes two percent to economic output and around 12 percent to the national budget. This is one reason why Petro’s Finance Minister José Ocampo wants to stick to oil production, at least for the time being. Ocampo has already stated this publicly several times. In an interview with the Spanish daily El País last November, for example, he spoke of “15 years of transition” and did not rule out new oil and gas contracts.

Ocampo did not react to Minister Vélez’s recent remarks himself, but José Roberto Acosta, a high-ranking official in the Ministry of Finance, warned on Twitter that Colombia’s energy transition would take about 20 years. And Ecopetrol’s importance for the national budget would have to change. But that, too, would take time. ae

A field experiment conducted by three universities shows that CO2 labels on food prompted consumers to make more sustainable choices. Information regarding the carbon footprint of meals was displayed on menu displays to more than 8,000 cafeteria visitors. According to the scientists, the greatest effect was achieved when visitors were given information about the environmental costs in euros. This saved almost ten percent in emissions because consumers opted for meals with a lower CO2 footprint.

Accordingly, information on carbon emissions in grams or the share of dishes in the daily carbon budget of cafeteria patrons was less effective. In addition, environmental damage was conveyed by coding in traffic light colors.

“Our experiment makes it clear that information on the carbon footprint can lead to a change in consumer behavior,” says Thorsten Sellhorn, Professor of Accounting and Auditing at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. Companies could use this insight to “display CO2 figures for food or other products and services.” nib

Fewer executives in Germany take climate seriously than the global average. Only 19 percent believe that business takes the issue “very seriously”. Globally, the figure is 29 percent. These are the findings of the recently published CxO Sustainability Survey 2023 by management consultants Deloitte. The survey was conducted in the fall of 2022 and surveyed more than 2,000 board members worldwide, including 105 from Germany.

The report reveals: Executives in Germany are nowhere near as concerned about climate change as their colleagues in other countries. Only 48 percent feel concerned about climate change all or most of the time, compared with 62 percent of respondents in other countries. Consequently, aspects such as climate justice and a socially just transformation are also of comparatively little importance. Internationally, they are considered very important by 46 percent of executives, especially in the Global South. In Germany, this is the case for only 25 percent of top executives. This ranks them second to last out of 24 in a country comparison.

The most important issues for German companies are economic development (52 percent, global: 44 percent) and innovation (42 percent, global: 36 percent). Supply chain problems (Global: 33 percent) and climate change (Global: 42 percent) followed in third with 37 percent.

One explanation could be that executives in Germany feel significantly less pressure to change when it comes to climate change than managers elsewhere in the world. Only 58 percent of respondents feel the pressure to change from their business partners and consumers (global: 68 percent). Only 50 percent (globally: 68 percent) also feel pressured by the government and legislators. This fits well with the fact that only 51 percent of German executives stated that new regulations had prompted them to make greater sustainability efforts in the past year (global: 65 percent). ch

It was one of the biggest news stories on Jan. 12: The Swedish state-owned company LKAB stumbled upon more than one million tons of rare earths while searching for iron ore, more than four times the current annual global production.

Rare earths, these are 17 elements that are used in the production of permanent magnets for wind turbines, electric motors, fuel cells or light sources – in other words, for technologies that are indispensable in the climate transition. The elements are called neodymium, praseodymium, lanthanum or yttrium. Never before have they been found in such large quantities in Europe. The media attention was correspondingly great.

Up to now, Europe has obtained rare earths, which it urgently needs for a climate-friendly transformation, primarily from China. The dependence on the Asian country is great, although the rare earths – contrary to their name – are not so rare. For example, they are also found in Storkwitz in Saxony. But they are not extracted there because that would not be economically viable.

But unfortunately, the Swedish discovery is not a game changer that could help Europe reduce its dependence on China in this area, which is so vital for a more climate-friendly economy.

In the 2010s, 95 percent of the global production of rare earths was already mined in China. Their high technological value made them a potential bargaining chip even at that time. To this day, our supply of rare earths is dependent on China: Of the 280,000 metric tons of rare earths mined worldwide in 2021, 70 percent entered the market via China – either because they were mined in the country itself, or because China bought them before they were further used domestically or re-exported.

We need new procurement sources. But the Swedish discovery will only help us to a limited extent: The concentration of rare earths in the ore-bearing rock at the site is only 0.2 percent, as Jens Gutzmer says, head of the Helmholtz Institute for Resource Technology in Freiberg and one of the leading scientists in the field: Much lower than, for example, in the Mountain Pass mines (USA) with 3.8 percent or Bayan Obo (China), with three to five percent ore concentration. This means that a lot of rock has to be moved in the new deposits in order to extract relatively little rare earth. It makes mining expensive and the ecological damage high.

Even if the extraction of rare earths in Sweden were to reach a certain share of global production in the next 10 to 20 years, the question of their processing remains unresolved. Here, too, China currently holds a market share of 85 percent, according to the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources. And Chinese reserves of rare earths are estimated at up to 44 million tons.

So our dependence on China will remain – unless we learn to better utilize valuable raw materials such as rare earths. We would have the means to do so. Rare earths can be recycled, but although they are so important for future technologies, the circular economy for rare earths has so far only been poorly established in Europe. Time and again, the importance of rare earths for wind turbines or electric motors was pointed out, and thus for a successful energy transition.

And yet they are being wasted. This is very harmful to the climate, because mining and further processing of metals contribute between 10 and 15 percent to global carbon emissions.

Currently, the share of recycled material in the total use of rare earths in Germany is well below 10 percent. This means that more than 90 percent have to be obtained through mining. There are approaches such as substitution – there are actually wind turbines without rare earths – or expanding recycling, which receives too little attention.

The Critical Raw Materials Act announced by the EU Commission for March will have to set the right framework conditions here:

Fundamentally, the share of mining in metal use must be reduced – and with it the environmental destruction and human rights violations that so often accompany mining. Germany and Europe need a genuine raw materials transition that places the protection of people and the environment at the center of policy.

Under the current circumstances, the newly discovered Swedish deposits will be quickly used up – if they can be mined at all. Because one thing was completely lost in the media euphoria: The Sami, on whose land the rare earths were found, have not yet approved the extraction.

Michael Reckordt is Program Manager Raw Materials and Resource Justice at PowerShift – Verein für eine ökologisch-solidarische Energie-& Weltwirtschaft e.V. in Berlin.

Walburga Hemetsberger sees Europe as a pioneer in the energy transition and climate action. And defending this role is the goal – also in terms of competitiveness. The urgency to expand renewables is just as clear to her as competition “not only with China, but also with the USA and India.” As CEO of SolarPower Europe, she sums up her vision as follows: “For me, Europe means security and economic prosperity. And being innovative together.”

A native of Austria, she has been at home in Brussels for years. Before joining Europe’s solar energy association, she headed the Brussels office of Verbund AG, Austria’s largest energy utility, among others, and served as a member of the board of Hydrogen Europe. The 47-year-old studied Law and Business Administration in Innsbruck. This background sharpens her eye for the applicable legal framework in energy policy.

Even after 20 years in the EU headquarters city, Hemetsberger has not lost her Austrian dialect. Speaking just German is something she is now unaccustomed to due to her English-speaking work environment. She says, “I have always been a staunch European.” She started working for “the European cause” right after graduation.

She was won over by the versatility of photovoltaics: On roofs, in the form of large solar farms, and in agriculture. When it comes to PV, Europe has exceeded the association’s forecasts in 2022. Over the course of the year, 41.4 gigawatts were newly installed, according to SolarpowerEurope figures – enough to supply 12.4 million households with electricity.

“Solar energy is very democratic. Everyone can participate – on the roof of their own house or via civic involvement in the solar park. Everyone becomes an energy citizen and helps with the energy transition,” says Hemetsberger. She never tires of emphasizing that PV also makes sense in places with fewer hours of sunshine: “Together with wind, solar will be one of the two crucial technologies that will hopefully lead us out of the crisis.”

She sees the main obstacle currently in approval procedures, which are still too slow across Europe – especially in view of the huge interest in securing energy supplies. But Hemetsberger also acknowledges the small steps forward: She welcomes the options of Repowering, with which solar plants in Germany can henceforth be more easily outfitted with new, more efficient PV modules to increase the yield.

In her view, bringing workers into future-oriented technology fields is a huge opportunity. “The question is to what extent you can do that just through market-based mechanisms, or do you need steering instruments to bring the PV industry back here?” She hopes SolarPower Europe will bring solar manufacturing back to Europe. Walburga Hemetsberger knows, “Only if we produce gigawatts on a large scale in Europe can we be globally competitive at the end of the day.” Julia Klann

Petting piglets, sampling veggie sausages, driving tractors – this is what the “International Green Week” in Berlin means for hundreds of thousands of visitors. But at the world’s largest agricultural trade fair, serious matters are also discussed on stage and behind the scenes. For instance: Does bioenergy have a future in the energy transition? How can EU agricultural policy help reach climate goals? Lisa Kuner and Alexandra Endres have the answers in this Climate.Table.

But as always, we also look beyond our own backyard: With backgrounds on Japan’s G7 presidency, which lacks a climate focus; with the debate on whether Australia’s carbon offset mechanism further increases emissions instead of reducing them; with a surprisingly positive track record for US President Biden’s climate policy; and with an opinion piece on the overlooked dimension in environmental debates: Namely, that any progress requires recycling and less use of materials. And, as usual, with plenty of additional background information from the worlds of science, politics and business.

As always, we appreciate your comments, criticism and suggestions at climate@briefing.table.media.

The use of biofuels is becoming an increasingly volatile political issue. Associations are making serious accusations against Germany’s Environment Minister Lemke and Agriculture Minister Özdemir. Lemke is accused of being “responsible for failing to meet climate action targets in the transport sector,” the biofuel industry said on Wednesday. According to the associations, a plan by the Federal Ministry for the Environment “to gradually phase out biofuels from cultivated biomass” would make it impossible to achieve the climate targets in the transportation sector. On January 19, Lemke submitted a draft to stop government subsidies for biofuels to the departmental vote. The draft envisages a phase-out of biofuels from food crops and rapeseed in Germany by 2030.

So-called e-fuels are an indispensable element for immediately effective climate action, says Artur Auernhammer, Chairman of the German Bioenergy Association. Joachim Rukwied, President of the German Farmers’ Association, also said earlier this week that “politicians must get out of their ideological box. We can only achieve our greenhouse gas reduction quota if we add biofuels to the mix.”

The Deutsche Umwelthilfe (Environmental Action Germany) sees things quite differently and holds Volker Wissing responsible. The Minister of Transport should no longer block Lemke’s initiative. The “insanity” of state subsidies for biofuels must be “ended immediately,” says Sascha Müller-Kraenner, the CEO of Deutsche Umwelthilfe.

Why is bioenergy such a controversial topic? Where are the biggest disputes? So far, bioenergy in Germany has been used primarily in three forms:

The energy debate revolving around the war in Ukraine, the requirements of net zero, and the expiration of EEG subsidies are changing the bioenergy landscape.

The National Biomass Strategy (NABIS) is supposed to answer this question for Germany. Taking food security into account, it is intended to determine how biomass can make a sustainable contribution to the energy supply. The key points of NABIS were presented last fall. It includes the following guiding principles:

If the EU wants to become carbon-neutral by 2050, agriculture must also reduce its emissions as far down towards zero as possible. In Germany, the Climate Change Act sets reduction targets for the agricultural sector. And at the EU level, new, more climate-friendly regulations for the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) have been in force since the beginning of 2023.

The EU Commission calls the new rules the “most ambitious CAP ever from an environmental and climate perspective.” Accordingly, 40 percent of agricultural subsidies are “devoted to delivering benefits for the climate.”

But the target is not being met – at least in Germany. This is the conclusion of a study published by the German Environment Agency. In it, researchers from the Öko-Institut and the University of Rostock examined how climate-effective agricultural subsidies actually are.

The findings:

Just under eleven percent of the European Union’s greenhouse gas emissions originate from agriculture. That may not seem like much. But decarbonizing the agricultural sector is particularly difficult, says Pierre-Marie Aubert, Director of Agriculture and food policies at French sustainability think tank IDDRI: “It’s nearly impossible to get agricultural emissions to zero.”

That is not because of farmers’ lack of will, Aubert says. “It’s because we’re working with living organisms here.” The digestion process of cows releases methane, soils treated with nitrogen fertilizer emit nitrous oxide, and drained wetlands emit carbon dioxide. The climate-friendly transformation of agriculture is further complicated by the fact that climate protection cannot be viewed separately. Biodiversity conservation and food production would always have to be taken into account.

Since 2012, greenhouse gas emissions from the EU agricultural sector have been rising again, Aubert says. “Whatever farmers say, they are not doing enough.” Like other experts, he criticizes CAP reform as insufficient. Despite all the EU Commission’s pronouncements, he says, direct agricultural payments to farms are currently “barely linked to any climate conditions.”

To make agriculture more sustainable, Aubert recommends one thing above all: The number of farm animals must fall – not to zero, but drastically nonetheless. “That would be good for climate and species conservation, and we would still have enough to eat as it would reduce dramatically feed-food competition.”

The tricky part is that many people are employed in the livestock sector. According to Aubert, 40 to 50 percent of agricultural jobs depend on keeping livestock, and about 30 to 40 percent of jobs in the food industry, depending on the countries at the EU level.

In addition, Aubert says, policymakers should encourage wetland rewetting and more efficient nitrogen use. The authors of the UBA study come to similar conclusions. Relevant laws and regulations could be adapted “even in the short term,” they write. They also call for expanding “climate-relevant CAP measures and financial resources.” The current CAP funding period runs until 2027 when the next revision is due.

Shortly after assuming the G7 presidency, Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida visited France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States in preparation for the G7 summit in Hiroshima in May. The G7 accounts for 25 percent of global emissions but is historically responsible for 44 percent of greenhouse gases and as such, they bear a great deal of responsibility for climate change.

While climate was a topic in the meeting with global leaders, the Japanese prime minister rarely spoke about it. For him, it is one of many global issues. He did not make any concrete proposals. He seemed to characterize it as one of many global issues and did not specify his proposals during his visit

Kishida’s mind is occupied with national security, which is becoming increasingly severe with the war in Ukraine and Chinese hegemony, and with his personal agenda of nuclear arms abolition. Hiroshima is his hometown, where a nuclear bomb was used for the first time in history.

Japan once gaveled out the historical Kyoto Protocol, which made it legally binding to reduce emissions. However, post-Kyoto climate diplomacy of Japan has been lacking leadership, and much of it appears backward. At recent G7 meetings, Japan has argued differently from other countries, such as for the export of coal-fired power and against the phase-out of new gasoline cars.

Japan also has a unique interpretation of last year’s Leaders’ Communiqué. It committed to “achieving a fully or predominantly decarbonized power sector by 2035”. Ministers and officials in Japan explain “predominantly” means “at least half,” which shows the reluctance of phasing out fossil fuel-fired power even in the future.

In his speech at COP26 in Glasgow, Kishida said Japan will promote the transition to clean energy, especially in Asia, by converting existing thermal power plants to zero-emission using ammonia/hydrogen. But this technology would not yet prove to be economically feasible. NGOs awarded “Fossil of the day” to Japan, saying that his plan would not help to achieve the 1.5-degree goal.

Kishida skipped the COP27 – and instead launched the “Asia Zero Emissions Community Initiative” at the G20 summit in Indonesia, which was taking place at the same time. A Japanese government official said this initiative will be one of the highlights at the G7 meeting. “It is meaningless for only developed countries to compete with each other for climate targets. We must take care of the Global South. We need to launch something realistic”

However, Japan distanced itself from the “Climate Club” planned by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the “Just Energy Transition Partnerships” (JETP) with which the G7 wants to promote the energy transition in countries such as South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam. Although Japan is the leading nation in the JETP with Indonesia alongside the USA, the government is silent on the subject, for example also at COP27. The reason: JETPs aim to end fossil fuels in the energy sector, but Japan plans to prolong fossil fuels use back home and with the “Asia Zero” initiative.

Japan has set the goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2050, reducing emissions by 46 percent by 2030. To achieve this, it is necessary to decarbonize the power sector, which as of FY2021 relies on fossil fuels for 73 percent of its electricity. The government has decided to increase renewable from 20 percent in FY2021 to 36-38 percent and nuclear from 6.9 percent to between 20 and 22 percent in the energy mix in 2030. However, this means that 40 percent of electricity will still be generated from fossil fuels in 2030, with almost half from coal. This largely filled the gap when Japan shut down 60 nuclear reactors in 2011 after the Fukushima nuclear accident.

Nuclear was the thorn in the side of Japan’s climate and energy policy. It divided public opinion. But with energy prices rising and energy supplies recently uncertain, polls now show a majority in favor of restarting the nuclear program for the first time. The government announced a plan to extend the operating life of reactors to 60 years and the development of new reactor types. Kishida had not mentioned this during the election campaign.

At the end of last year, the government proposed the basic policy of “Green Transformation.” It calls for “a shift from the fossil energy-centered industrial and social structure to a focus on clean energy,” but rather an emphasis on energy security. A return to nuclear power is included. It has laid out transition roadmaps for 22 areas, including hydrogen/ammonia, batteries, steel, and automobiles. To achieve this, the government plans to invest over 150 trillion yen (about one trillion euros). 20 trillion yen, about 140 billion euros, in new public bonds are to be issued. And it will be repaid through carbon pricing, including a levy on fossil fuel importers starting in 2028, and emissions trading among electric power companies.

NGOs are against government policy, saying that it will further increase dependence on nuclear and coal. In preparation for the G7, 350.org Japan sent a letter to the government. It called for “placing the climate crisis and energy issues on the key agenda.” And criticizing the Government’s reliance on technologies such as next-generation nuclear power, carbon capture and storage (CCS/CCUS), and ammonia/hydrogen co-firing of fossil fuels with thermal power as “false solutions,” they call for “steering away from fossil fuels in their true nature” By Keisuke Katori from Tokyo

In mid-January, the Australian federal government issued a report defending its own climate protection programme against criticism that the national CO2 offset mechanism hardly contributes to climate protection. This contradicts critics and whistleblowers. They claim that the program not only does not reduce emissions, it actually increases them, a criticism they continue to maintain. Whether Australia’s national offset mechanism for voluntary CO2 certificates is credible and effective remains hotly disputed.

Whistleblower and regulatory and environmental markets expert Andrew Macintosh, former head of the government’s Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee and now professor of environmental law at the Australian National University, published a series of reports. He found that at least 70 percent of the annual Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) – over 10 to 12 million tonnes of CO2 – did not deliver any actual or additional emissions reductions.

The ACCU is an important part of Australia’s climate protection policy known as The Safeguard Mechanism which essentially places caps (‘baselines’) on the country’s biggest emitters. It is intended to reduce emissions by requiring companies that do not meet their baseline to purchase offsets – carbon abatement credits in other areas of the economy – to account for the amount of emissions that exceed the agreed limit.

The government responded with the Chubb Report, which has now been presented. It was named after former chief scientist Ian Chubb. Their findings:

Ultimately, the Chubb panel rejected Macintosh’s claims that “the integrity of the system has been called into question”, that “the extent of emission reductions has been overstated”. The Chubb Panel admitted it had been presented with “some evidence supporting this view, but also evidence to the contrary”.

The government feels vindicated: In a press conference on Monday, climate change minister Chris Bowen said the system was “not as broken as has been claimed” and “fundamentally sound“.

The Chubb report is not transparent on a number of points: for example, it does not present the evidence to which it refers. It also does not address any of Macintosh’s criticisms of the integrity of the system. He, in turn, is disappointed: “The main section on these key methods is only five pages long, and it doesn’t address any of these issues. Is that good scientific practice? Not at all.”

Critics claim that many regeneration projects would have received CO2 credits without actually planting forests – or for regeneration that would have taken place anyway. Macintosh and his research team estimate that 165 projects have received CO2 credits for a total of 24.5 million Australian dollars, even though forest and replacement woody vegetation has declined by more than 60 000 hectares in total.

For Macintosh, the Chubb report did more harm than good because it fuelled industry opposition to voluntary certificates. “What we all wanted was an integrated system and there is a great opportunity to achieve that. We have a new government and a new emissions trading scheme to be introduced. The carbon markets have a great opportunity to deliver really good environmental outcomes. But if we don’t get all these things right, they will be lost.”

Don Butler, Chief Scientist in Queensland’s Land Restoration Fund and Professor of Law at the Australian National University whose work with Macintosh has challenged the Australian offsetting initiative, also says that “the administration of the method is a failure”. There are “obvious ways in which offsets can work, but at the systems level there seems to be some kind of failure globally“, he says. “It’s a complicated area where no one but the regulator has a strong interest in the integrity of the outcome,” he says.

The critics’ fear: The outcome of the Chubb review could bring higher emissions and formalise government greenwashing for fossil fuels. Only a small number of carbon credit developers would earn money from this.

Polly Hemming of the public policy think tank, The Australia Institute says: “The safeguard mechanism is not designed to drive decarbonisation. It’s designed to protect fossil fuels and funnel money to commercial carbon credit developers.”

Following Bowen’s statements, critics fear the allowances could guarantee the continued expansion of oil, gas and coal because they supposedly ‘offset’ their emissions. Australia currently has 114 new fossil fuel projects under development, including 72 new coal projects, 44 new gas and oil projects and several new gas basins which are actively supported by state and federal governments, including through large government subsidies. These projects would more than double Australia’s gas and coal production and introduce around 1.4 billion additional tonnes of CO2 emissions per year.

Jan. 31; 9.30 a.m., Online

Discussion Mercosur Trade Agreement – Will 2023 be the year it is finally ratified?

EU experts discuss the ratification of the EU-Mercosur agreement at EURACTIV’s event. Among other things, the agreement has not yet been able to enter into force due to sustainability concerns. Info and registration

A speed limit of 120 km/h on highways and 80 km/h on country roads could save around 47 million metric tons of CO2 by 2030, according to new calculations by the German Environment Agency. This means that the climate mitigation effect of limiting the maximum permitted speed would be much more effective than previously thought. This is because emissions from internal combustion engines increase significantly above 130 km/h. The agency already pointed this out in 2020. nib

The heads of Germany’s five major environmental associations have joined the debate on energy security with far-reaching compromise proposals on the expansion of renewables. In a thesis paper entitled “Ein Booster für erneuerbare und grüne Infrastruktur” (A booster for renewable and green infrastructure), which Climate.Table has obtained in advance, they propose measures for a faster expansion of wind and solar energy, better funding for municipalities, and systemic safeguarding of nature conservation areas.

The authors of the paper are Kai Niebert (DNR), Jörg-Andreas Krüger (Nabu), Olaf Bandt (BUND), Martin Kaiser (Greenpeace) and Christoph Heinrich (WWF). The paper is a joint work by these association heads and has not been coordinated within their respective organizations. It has, therefore, not yet been distributed by their associations. Some of the proposals go beyond what is currently feasible within the associations.

The initiators reportedly presented the letter to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the relevant ministries. “The government has asked us for concrete proposals for the nature-compatible and accelerated expansion of renewable energies,” Kai Niebert told Climate.Table. “We hereby submit these ideas.”

Above all, the five association leaders propose:

The paper is to be issued in the next few days as a discussion basis. Among other things, the heads of the eco-associations want to use it to enter the current debate on whether, for example, road and highway planning should also be classified as “paramount public interest”. bpo

After two years in office, US President Joe Biden has been given a very good climate rating by the US think tank World Resources Institute. In a blog post, WRI Director Dan Lashof praised the Democratic president’s efforts. This means that the score has improved dramatically compared to last year – primarily due to the gigantic IRA investment program, which earmarks almost $370 billion for the expansion of green industries and infrastructure. “Congress finally delivered transformative legislation to tackle the climate crisis.”

The think tank praises Biden’s administration in particular for:

The WRI also sees “significant progress”:

WRI sees “some progress”:

The WRI does not see the government on the right track:

According to a report commissioned by Environmental Action Germany (DUH), the climate damage caused by imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) is massively underestimated. LNG imports from the USA fare particularly poorly. Here, methane leaks from fracking are particularly high. In some cases, methane losses of over ten percent occur. Gas production in Algeria and Nigeria leads to methane losses of over six percent of the gas produced. Norwegian pipeline gas has the lowest methane emissions. However, the data situation is “unsatisfactory almost everywhere” because methane emissions from the gas and oil industry have been neglected for a long time, the authors said.

Although climate gas has a shorter lifespan, it is about 80 times more harmful to the climate than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. According to DUH, methane leaks are more climate-damaging than burning gas for energy. The NGO calls to stop ignoring the “climate damage in the upstream chain of our gas supply.” “As long as we use natural gas that is harmful to the climate, the federal government [Germany] and companies must at least select the gas sources with the lowest emissions,” says DUH CEO Sascha Müller-Kraenner. nib

When asked what financial damage one ton of emitted carbon dioxide (CO2) causes, the German Federal Ministry of Transport gives very different answers. In its calculation of the economic benefit of investments in local rail transport, Volker Wissing’s (FDP) ministry drastically raised this figure last summer in order to better justify projects. Instead of the previous figure of €149, the climate damage per ton of CO2 is now set at €670. This means that, mathematically speaking, saving CO2 has become four-and-a-half times more valuable. The new value is even significantly greater than the carbon price demanded by Fridays for Future. The German Federal Environment Agency (UBA) calculates this higher value by valuing the damage caused by carbon emissions for future generations at the same level as for the current generation. This is not the case with currently used values.

This change allows the German government to co-finance more regional rail projects. This is only possible if the so-called “Standardized Assessment” indicates an economic benefit – and this is, of course, more likely to be the case if the reduction in CO2 emissions is worth more than it has been in the past. In particular, co-funding for the electrification of rail lines with low tunnels, which in the past often fell just short of the economic viability mark because of the high construction costs involved in enlarging tunnels, has been easier since. “When assessing economic viability, the factors of climate and environmental protection, modal shift and services of general interest, for example, now carry more weight,” Wissing explained last summer. And, “That is in keeping with the times.”

In long-distance transport, however, the German government’s calculations are not yet as “up-to-date”. Here, the federal government’s investments are based on the Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan – and this still puts the financial loss per ton of CO2 at just €145. This makes road projects seem more economical, while rail projects seem less so. The Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport has not yet decided whether the higher UBA value should also be used here in the future. One argument against the change is that planning security would be jeopardized if the currently valid transport infrastructure plan were changed. The argument in favor is that it is hard to imagine why a ton of carbon dioxide saved in local traffic should prevent four and a half times as much damage as in long-distance traffic. mkr

The European Central Bank (ECB) has unveiled statistical indicators to better analyze climate-related risks in the financial sector and monitor the green transition. “The indicators are a first step to help narrow the climate data gap, which is crucial to make further progress towards a climate-neutral economy,” said ECB Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel.

Risk indicators include sustainable financial instruments, carbon emissions from financial institutions, and physical risks from loan and securities portfolios.

“The experimental indicators on sustainable finance provide time-series information on outstanding amounts and financial transactions relating to issuances and holdings of sustainable debt instruments”. This is intended to help analysts understand both the financing needs of sustainable projects and the demand for these debt instruments as investment opportunities.

According to the ECB, the indicators for carbon emissions financed by the financial sector and the associated risks for the transition to a net zero economy cover two aspects: Total emissions financed by the financial sector and the financial sector’s involvement in emissions-intensive business. The indicators are intended to help analyze and assess the role of the financial sector in financing carbon-intensive business activities.

For this purpose, the financed emissions are considered in relation to total company value, as well as the carbon intensity of the product.

The ECB defines physical risks as consisting of three elements: Physical hazards, for example, to infrastructure, asset vulnerability and asset susceptibility to these hazards. The indicators are intended to assess the level of risk in individual portfolios and the expected losses.

The impact of natural events caused by climate change on the financial system is to be quantified using historical data and forecasts. In particular, the ECB focuses on natural events that have historically caused the greatest damage in the EU or that are projected to increase in the future. Climate-related natural events that have a more indirect impact on human health – heat waves, for example – are not yet included in this set of indicators. luk

It was a central campaign promise of Colombia’s leftist President Gustavo Petro to stop issuing new oil and gas licenses. But it now seems doubtful that he will be able to keep it. As the Guardian, among others, reports, there is also strong opposition within the government.

Petro has only a slim majority in parliament. In addition, according to the Guardian, an “increasingly bleak economic outlook and a series of policy U-turns from the government have put Petro’s ambitious environmentally friendly pledge in doubt”.

Colombia’s Energy and Mines Minister Irene Vélez confirmed Petro’s plans at the World Economic Forum in Davos: The government will no longer issue new oil and gas licenses, she said. The decision may be controversial, she said, but it is “a clear sign of our commitment in the fight against climate change.” She urged that immediate action be taken.

Petro backed his minister. During the election campaign, he had already announced plans to restructure the country’s economy in a “productive, but no longer extractivist” way. He intends to turn the domestic oil company Ecopetrol into a “major supplier of clean energy for Colombia and Latin America.

So far, Colombia’s economy and national budget have been heavily dependent on fossil fuels. The oil sector generates about one-third of the country’s export revenues, contributes two percent to economic output and around 12 percent to the national budget. This is one reason why Petro’s Finance Minister José Ocampo wants to stick to oil production, at least for the time being. Ocampo has already stated this publicly several times. In an interview with the Spanish daily El País last November, for example, he spoke of “15 years of transition” and did not rule out new oil and gas contracts.

Ocampo did not react to Minister Vélez’s recent remarks himself, but José Roberto Acosta, a high-ranking official in the Ministry of Finance, warned on Twitter that Colombia’s energy transition would take about 20 years. And Ecopetrol’s importance for the national budget would have to change. But that, too, would take time. ae

A field experiment conducted by three universities shows that CO2 labels on food prompted consumers to make more sustainable choices. Information regarding the carbon footprint of meals was displayed on menu displays to more than 8,000 cafeteria visitors. According to the scientists, the greatest effect was achieved when visitors were given information about the environmental costs in euros. This saved almost ten percent in emissions because consumers opted for meals with a lower CO2 footprint.

Accordingly, information on carbon emissions in grams or the share of dishes in the daily carbon budget of cafeteria patrons was less effective. In addition, environmental damage was conveyed by coding in traffic light colors.

“Our experiment makes it clear that information on the carbon footprint can lead to a change in consumer behavior,” says Thorsten Sellhorn, Professor of Accounting and Auditing at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. Companies could use this insight to “display CO2 figures for food or other products and services.” nib

Fewer executives in Germany take climate seriously than the global average. Only 19 percent believe that business takes the issue “very seriously”. Globally, the figure is 29 percent. These are the findings of the recently published CxO Sustainability Survey 2023 by management consultants Deloitte. The survey was conducted in the fall of 2022 and surveyed more than 2,000 board members worldwide, including 105 from Germany.

The report reveals: Executives in Germany are nowhere near as concerned about climate change as their colleagues in other countries. Only 48 percent feel concerned about climate change all or most of the time, compared with 62 percent of respondents in other countries. Consequently, aspects such as climate justice and a socially just transformation are also of comparatively little importance. Internationally, they are considered very important by 46 percent of executives, especially in the Global South. In Germany, this is the case for only 25 percent of top executives. This ranks them second to last out of 24 in a country comparison.

The most important issues for German companies are economic development (52 percent, global: 44 percent) and innovation (42 percent, global: 36 percent). Supply chain problems (Global: 33 percent) and climate change (Global: 42 percent) followed in third with 37 percent.

One explanation could be that executives in Germany feel significantly less pressure to change when it comes to climate change than managers elsewhere in the world. Only 58 percent of respondents feel the pressure to change from their business partners and consumers (global: 68 percent). Only 50 percent (globally: 68 percent) also feel pressured by the government and legislators. This fits well with the fact that only 51 percent of German executives stated that new regulations had prompted them to make greater sustainability efforts in the past year (global: 65 percent). ch

It was one of the biggest news stories on Jan. 12: The Swedish state-owned company LKAB stumbled upon more than one million tons of rare earths while searching for iron ore, more than four times the current annual global production.

Rare earths, these are 17 elements that are used in the production of permanent magnets for wind turbines, electric motors, fuel cells or light sources – in other words, for technologies that are indispensable in the climate transition. The elements are called neodymium, praseodymium, lanthanum or yttrium. Never before have they been found in such large quantities in Europe. The media attention was correspondingly great.

Up to now, Europe has obtained rare earths, which it urgently needs for a climate-friendly transformation, primarily from China. The dependence on the Asian country is great, although the rare earths – contrary to their name – are not so rare. For example, they are also found in Storkwitz in Saxony. But they are not extracted there because that would not be economically viable.

But unfortunately, the Swedish discovery is not a game changer that could help Europe reduce its dependence on China in this area, which is so vital for a more climate-friendly economy.

In the 2010s, 95 percent of the global production of rare earths was already mined in China. Their high technological value made them a potential bargaining chip even at that time. To this day, our supply of rare earths is dependent on China: Of the 280,000 metric tons of rare earths mined worldwide in 2021, 70 percent entered the market via China – either because they were mined in the country itself, or because China bought them before they were further used domestically or re-exported.

We need new procurement sources. But the Swedish discovery will only help us to a limited extent: The concentration of rare earths in the ore-bearing rock at the site is only 0.2 percent, as Jens Gutzmer says, head of the Helmholtz Institute for Resource Technology in Freiberg and one of the leading scientists in the field: Much lower than, for example, in the Mountain Pass mines (USA) with 3.8 percent or Bayan Obo (China), with three to five percent ore concentration. This means that a lot of rock has to be moved in the new deposits in order to extract relatively little rare earth. It makes mining expensive and the ecological damage high.

Even if the extraction of rare earths in Sweden were to reach a certain share of global production in the next 10 to 20 years, the question of their processing remains unresolved. Here, too, China currently holds a market share of 85 percent, according to the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources. And Chinese reserves of rare earths are estimated at up to 44 million tons.

So our dependence on China will remain – unless we learn to better utilize valuable raw materials such as rare earths. We would have the means to do so. Rare earths can be recycled, but although they are so important for future technologies, the circular economy for rare earths has so far only been poorly established in Europe. Time and again, the importance of rare earths for wind turbines or electric motors was pointed out, and thus for a successful energy transition.

And yet they are being wasted. This is very harmful to the climate, because mining and further processing of metals contribute between 10 and 15 percent to global carbon emissions.

Currently, the share of recycled material in the total use of rare earths in Germany is well below 10 percent. This means that more than 90 percent have to be obtained through mining. There are approaches such as substitution – there are actually wind turbines without rare earths – or expanding recycling, which receives too little attention.

The Critical Raw Materials Act announced by the EU Commission for March will have to set the right framework conditions here:

Fundamentally, the share of mining in metal use must be reduced – and with it the environmental destruction and human rights violations that so often accompany mining. Germany and Europe need a genuine raw materials transition that places the protection of people and the environment at the center of policy.

Under the current circumstances, the newly discovered Swedish deposits will be quickly used up – if they can be mined at all. Because one thing was completely lost in the media euphoria: The Sami, on whose land the rare earths were found, have not yet approved the extraction.

Michael Reckordt is Program Manager Raw Materials and Resource Justice at PowerShift – Verein für eine ökologisch-solidarische Energie-& Weltwirtschaft e.V. in Berlin.

Walburga Hemetsberger sees Europe as a pioneer in the energy transition and climate action. And defending this role is the goal – also in terms of competitiveness. The urgency to expand renewables is just as clear to her as competition “not only with China, but also with the USA and India.” As CEO of SolarPower Europe, she sums up her vision as follows: “For me, Europe means security and economic prosperity. And being innovative together.”

A native of Austria, she has been at home in Brussels for years. Before joining Europe’s solar energy association, she headed the Brussels office of Verbund AG, Austria’s largest energy utility, among others, and served as a member of the board of Hydrogen Europe. The 47-year-old studied Law and Business Administration in Innsbruck. This background sharpens her eye for the applicable legal framework in energy policy.

Even after 20 years in the EU headquarters city, Hemetsberger has not lost her Austrian dialect. Speaking just German is something she is now unaccustomed to due to her English-speaking work environment. She says, “I have always been a staunch European.” She started working for “the European cause” right after graduation.

She was won over by the versatility of photovoltaics: On roofs, in the form of large solar farms, and in agriculture. When it comes to PV, Europe has exceeded the association’s forecasts in 2022. Over the course of the year, 41.4 gigawatts were newly installed, according to SolarpowerEurope figures – enough to supply 12.4 million households with electricity.

“Solar energy is very democratic. Everyone can participate – on the roof of their own house or via civic involvement in the solar park. Everyone becomes an energy citizen and helps with the energy transition,” says Hemetsberger. She never tires of emphasizing that PV also makes sense in places with fewer hours of sunshine: “Together with wind, solar will be one of the two crucial technologies that will hopefully lead us out of the crisis.”

She sees the main obstacle currently in approval procedures, which are still too slow across Europe – especially in view of the huge interest in securing energy supplies. But Hemetsberger also acknowledges the small steps forward: She welcomes the options of Repowering, with which solar plants in Germany can henceforth be more easily outfitted with new, more efficient PV modules to increase the yield.

In her view, bringing workers into future-oriented technology fields is a huge opportunity. “The question is to what extent you can do that just through market-based mechanisms, or do you need steering instruments to bring the PV industry back here?” She hopes SolarPower Europe will bring solar manufacturing back to Europe. Walburga Hemetsberger knows, “Only if we produce gigawatts on a large scale in Europe can we be globally competitive at the end of the day.” Julia Klann