The Thursday of the second COP week is like a miniature climate crisis: The sins of the past now take their revenge. We could have started looking for solutions much earlier, we should have reached compromises much faster. But no, and now look where we are. Those who dawdled over the last few days now have to work at high pressure. All decisions have to be made simultaneously, and time, coffee and patience are running out.

Sharm el-Sheikh is no exception. It is Thursday evening and it is still not clear where things are headed. What about the “implementation COP” and a way to finance climate damage? Are there serious promises to cut emissions and provide money for the poorest? In this issue, you’ll see that when it comes to the hottest issue, “loss and damage” financing, for example, ideas are still very far apart.

And there are good proposals. For example, the promise made in Glasgow to quickly reduce methane, a climate killer. It would save money and greenhouse gases, and is feasible. However, we are sobered by the fact that not much has really happened. It is far too difficult to break out of familiar patterns such as industrial agriculture.

In any case, we are preparing for overtime and “over days” in Sharm el-Sheikh. It does not matter anymore now. So the rule is: stay awake! Our latest Climate.Table will help you with that.

The success or failure of the “implementation conference” will be determined by whether there is a compromise on the structure and financing of loss and damage (L+D). Negotiators call this the “landing zone” where ministers can reach agreement. As of Thursday evening, however, the positions are still far apart.

The developing countries’ proposal is a maximum demand of the Global South. It provides for:

With this, the developing countries under China’s leadership set down their ideas and demands. It is not a compromise paper: Many elements are unacceptable for the industrialized countries.

How far the demands differ from the ideas of the industrialized countries is shown in the report of the mediators (co-facilitators), which was published by the latter on Nov. 15. Chilean Environment Minister Maisa Rojas and German Climate Envoy Jennifer Morgan are leading these explorations. They have compiled the conflicting sides.

The difference is shown, for example, in the fact that the developing countries want to adopt an “ad hoc body (working group)” immediately. The opposing position calls for “no specific group” and only “activities that can collectively be called a work program.” The differences are most evident in the goal of negotiations by 2024:

In short, these are the different positions:

Between the maximum positions of “decide everything immediately” and “just decide to talk,” there must be a middle ground for a compromise. Traditionally, the EU makes such proposals. It also has made clear that it does not see “the fund as a panacea,” as EU Climate Commissioner Frans Timmermans puts it. German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock also says COP27 “might not be the place to decide on a fund.”

In contrast, the EU seeks a “Sharm el Sheikh work program” lasting two years, according to an internal draft available to Climate Table. According to this, a new fund could be created under the UN climate convention, outside the convention or under the Paris Agreement. Existing funds like the GCF should be strengthened and more money raised outside the convention. By March 2023, the work program should take stock of what L+D funding is already available, which gaps exist, how best to fill them, and what additional sources of money exist.

However, the current debate still has many unanswered questions. For example, it is completely unclear what exactly loss and damage means. Where is the distinction between loss and damage and other damage, if money is to be paid for it? It is also unclear which countries should actually receive money. All developing countries? Only the group of least developed countries, the LDCs?

Critics of a quick fund decision at COP27, such as the Environmental Integrity Group (IEG), also point out that it makes little sense to decide on an “empty shell” that cannot begin its work. They pointed to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which took about six to eight years for the money to flow. Money for L+D, however, needs to flow quickly, they said. In this view, individual projects such as the “Global Shield” are better suited for this. Or a “loss and damage window” could be opened at the GCF.

Finally, the explosive question of who should pay into such a fund looms in the background. The G77/China proposal is clear: the industrialized countries. But the latter point out that the world has changed drastically since 1992, back when the Framework Convention on Climate Change was adopted. In the meantime, emerging economies such as China, Korea, Mexico, Brazil and Indonesia have become powerful economies – and also major emitters. Not to mention oil countries like Saudi Arabia and their wealth from fossil fuels.

Many experts and negotiators believe that these issues need to be resolved first before embarking on the adventure of a new financial mechanism. On the other hand, this debate is long overdue. It could have started at the latest with the establishment of the Warsaw Mechanism WIM in 2013.

Care and urgency are needed among many delegates. Saleemul Huq, veteran of the negotiations, advisor to vulnerable countries, and expert at the think tank ICCCAD has his own simple proposal: “This COP27 decides to establish a Loss and Damage Finance Facility.” Just that one sentence. And by deliberately using the vague term “facility”, it can mean many things. And then we will sort out all the details by COP28 in one year.

Mr. Bohn, what is the first thing Lula must do after taking office to protect the Amazon forest?

First, he must restore the existing forest protection laws and tighten them. He must strengthen the control authorities that ensure that these laws are complied with, and which were weakened under the previous government of Jair Bolsonaro. The punishments for illegal logging should also be increased.

Is the enthusiasm with which Lula was received here justified?

I thought it was unusual for diplomatic circles. But of course, not only diplomats are here. And the indigenous population groups in particular, who are also represented here, have high hopes for Lula. He promised here at COP27 to set up a special ministry for Brazil’s indigenous population, which I very much welcome in principle. We know from various studies that these indigenous groups are particularly capable of managing their forest sustainably. Therefore, it is good if their voice is properly heard in the further development of forest protection by the government.

Lula has promised to protect forests, but Brazil is still supposed to remain an agricultural power. How does that fit together?

It depends on the definition of agricultural economy. What is not possible is for Brazil to remain the country with the most cattle and the largest beef production. First, because of the climate impact of methane. But also because cattle farming requires a lot of land.

How else should agriculture change?

Traditional agriculture in Brazil consists of monocultures, for example extensive soybean fields. Agroforestry would be an alternative. This usually involves trees that bind nitrogen in the soil. Underneath, you have fruit trees like mango, banana or papaya. And underneath that you have coffee, wheat, root tubers. That way, many different things can be grown on a given area of land. That also reduces land use.

What is the current condition of the Amazon forest?

There are areas that are still quite stable. But at the edges, some areas have now gone from being a carbon sink to a carbon source. Clearing by fire plays a role there, of course. But even apart from the fires, the question is whether the forest in these regions is already on the edge.

Could Lula reverse this with the right forest conservation policies?

Once an original rainforest has been felled, it will never grow again in that place. But a secondary forest can be created, perhaps with other species that can grow well there under the conditions of climate change, such as increasing drought. Such a freshly replanted forest will be a carbon sink for decades.

What are the benefits of the forest conservation cooperation agreement just signed by Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia?

The agreement allows the three countries to pull together in international negotiations. If they coordinate their efforts, they will carry weight. Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia collectively own more than half of the tropical rainforest. The fact that they are cooperating is definitely good. But there are no more concrete agreements at the moment.

And the Forest Climate Leader Partnership (FCLP), which was also signed here at COP27 and of which Germany is a member, suffers because precisely these three countries are not part of it. Negotiations are currently underway to determine whether they will join or whether cooperation will be organized in another way.

How do you rate the FCLP?

In the FCLP, regular meetings at the highest ministerial level have been agreed to coordinate cooperation. That is positive. It also takes into account the importance of indigenous and local groups, which I very much support. The problem is the total amount of money available to the FCLP. Germany is involved with two billion euros, which is one third of the amount earmarked for the Green Climate Fund.

Can these collaborations really stop the trend toward global deforestation?

I would say it is going in the right direction. But to evaluate the cooperations, we have to wait another two or three years. Only then will we see with our satellite measurements what is really happening. Last year, we observed a 6.3 percent decrease in deforestation. But deforestation has to drop by 10 percent every year to reach the Glasgow target and stop deforestation by 2030.

Friedrich Bohn is an ecosystem modeler with a focus on forest research at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research UFZ in Leipzig. At COP27, he currently monitors developments in forest conservation there – and witnessed the enthusiasm for Brazil’s future president Lula da Silva.

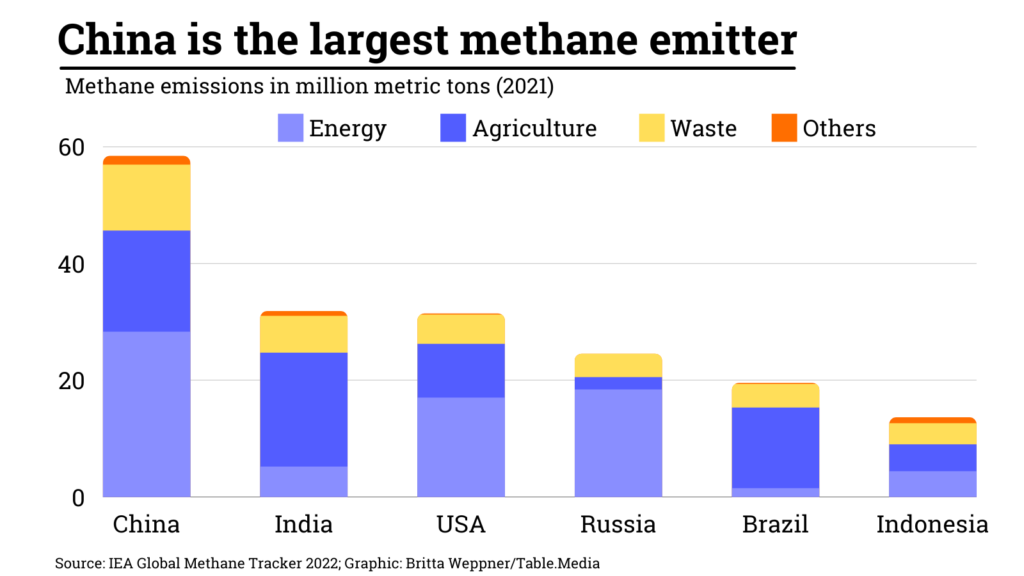

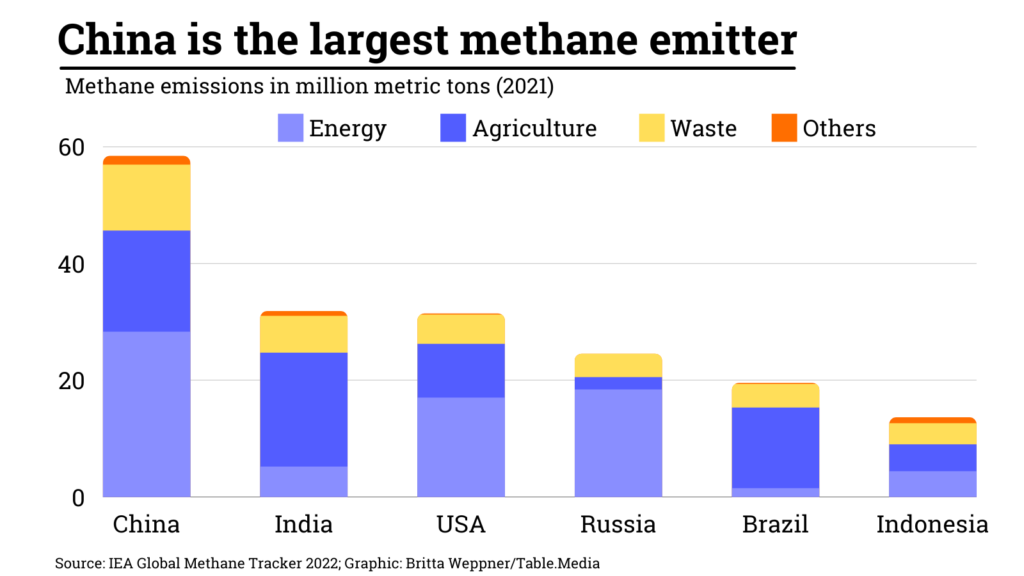

More than 150 countries have now signed the Global Methane Pledge; together they want to reduce methane emissions by 30 percent by 2030 compared to 2020. John Kerry made the announcement Thursday at a ministerial meeting at COP27. On Thursday, heavyweights Kerry and Frans Timmermans praised the efforts of participating nations.

But: So far, only 50 countries submitted an action plan on how to reduce emissions. And no global interim results or new strategies were presented at the event. Instead, two “pathways” for methane reduction in agriculture and in the waste sector were presented – they complement the Energy Pathway, adopted in June 2022.

Furthermore, the contents of these pathways known so far are very small-scale. For example, 70 million dollars are to be provided for research into the digestion process of livestock. In addition, small farmers in the Global South are to be supported in reducing methane emissions.

Frans Timmermans said, “our biggest challenge, as I gather in many countries, is in the agricultural sector.” Emissions from this politically sensitive sector have been largely left out of the equation. Yet the 15 largest meat and dairy companies produce more methane emissions than Germany or Russia, according to a new study. Only six of the companies fully disclose their emissions. None of the participating countries have adequate plans to reduce emissions in this sector.

Large methane emitters such as China, India and Russia are not part of the Global Methane Pledge. They account for 30 percent of global methane emissions. It is unlikely that Russia, which is internationally isolated, will join such an initiative in the coming years.

Although the US and China did agree in Glasgow to tighten controls on methane emissions, and both countries wanted to develop methane strategies, bilateral climate cooperation, which included the methane issue, was suspended by China after Nancy Pelosi’s Taiwan visit. The People’s Republic did develop a methane plan, which is expected to be published this year.

But China’s chief climate negotiator Xie Zhenhua said during the first week of the COP that China’s ability to control methane emissions remains “weak.” Accordingly, China’s goal is to improve its ability to monitor and track emissions.

On Thursday, EU climate czar Frans Timmermans still expressed the hope that China would join the Global Methane Pledge. But that did not happen and is unlikely for the next few years. Most of China’s methane emissions come from the coal sector. It is more costly and complex to reduce these emissions than in the oil and gas sector.

Energy security ranks high on China’s agenda, competing with environmental goals such as reducing methane emissions. “I expect it will take a few more years for methane to become more significant in practice,” Cory Combs, energy and climate expert at consulting firm Trivium China, told Climate.Table.

Over short periods, methane is a far more harmful greenhouse gas to the climate than carbon dioxide. However, it remains in the atmosphere for a shorter period of time:

The signatories to the Global Methane Pledge account for over half of global methane emissions. They have enacted some measures and regulations. But overall, some gaps remain. Under current policies, global methane emissions are expected to increase more than 15 percent by 2030 if regulations are not tightened.

There is criticism of the EU methane regulation, for example. It does not include emissions from imported fossil fuels. Yet these emissions account for 75 to 90 percent of European methane emissions (Climate.Table reported).

Organizations such as Methane Action, the EIA Climate Campaign and the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development call for a binding methane agreement. Progress on emissions reductions has been too slow, they say. “To keep 1.5 alive, we’ll need more than voluntary frameworks and preliminary plans,” says Daphne Wysham, chair of Methane Action. “We need a binding agreement, with targets and timetables for getting record-high atmospheric methane concentrations back down to preindustrial levels.”

With a new report and a new world map of peatlands, researchers and the UN Environment Programme UNEP draw attention to an often-forgotten threat to the climate: carbon emissions from drained wetlands. After all, peatlands are the world’s threatened and largely ignored carbon reservoirs. On only about four percent of land area, they store about one-third of the carbon bound in the soil.

The new Global Peatlands Assessment provides information on the condition of wetlands, including:

A new version of the first map of the world’s peatlands, produced by the Greifswald Moor Centrum, is also part of the new report. It warns against further draining peatlands and using them for conventional agriculture. So far, drainage contributes four percent of global carbon emissions, twice as much as Germany. If the present drainage rate is maintained, the report warns, 41 percent of the carbon budget remaining for the 1.5-degree limit will be used up.

As countermeasures, “harmful operations” such as drainage would have to be prevented and stopped in particular. The protection of these areas should be improved through financial incentives. Fair and gender-responsive practices should be supported, as well as the management of these areas by indigenous communities. bpo

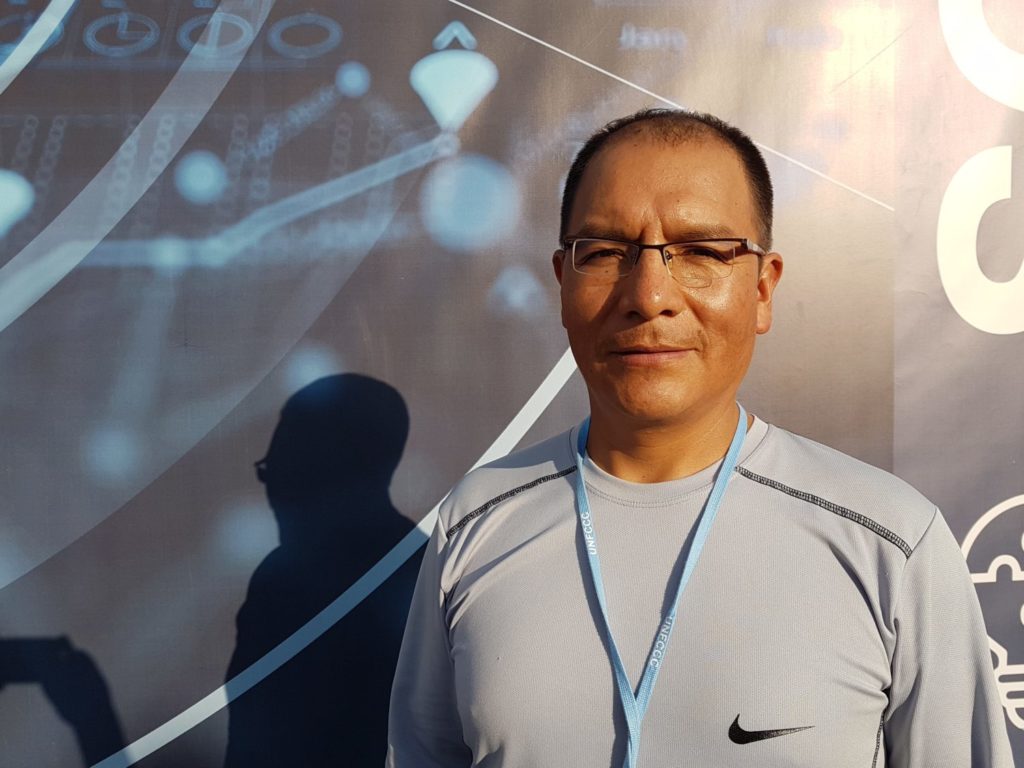

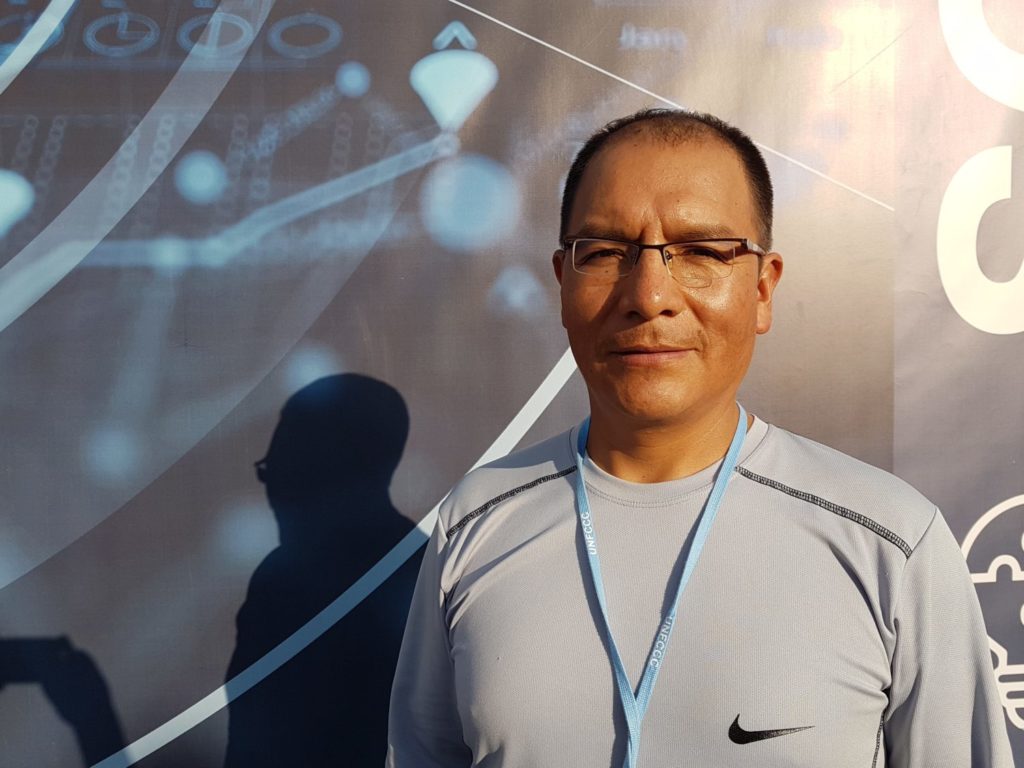

Saúl Luciano Lliuya took a three-and-a-half-day journey to get to COP27. Last Tuesday, early in the morning, the mountain guide left his home in the town of Huaraz in the Peruvian Andes. He traveled nine hours by bus to Lima. From there, he took a plane from Bogotá to Madrid to Istanbul, and finally to Sharm el-Sheikh. On Friday night, he arrived at the venue of the climate summit. For him, it is the third COP after Paris 2015 and Bonn 2017.

“I’m already thinking about how long the trip back will be,” Saúl says. But he hopes the hardship will be worth it. He wants to educate others at the climate summit and motivate them to do the same. Saúl Luciano Lliuya has sued a coal company that, according to the Carbon Majors Report, is responsible for about half a percent of industrial greenhouse gas emissions since 1988, making it one of the world’s largest emitters: the German company RWE.

In November 2015, shortly before the climate summit in Paris began, Saúl and his lawyer Roda Verheyen filed a lawsuit at the Essen Regional Court. Their argument: RWE is substantially responsible for global warming and its effects, which are already being felt in the Peruvian mountains today, for example through the melting of glaciers. Above Huaraz, the meltwater flows into a lagoon that continues to fill up. The lagoon is bordered by a dam. But the dam is in need of repair and has broken once already. Should this happen again, Saúl’s house in Huaraz could be flooded.

With his lawsuit, Saúl seeks to have RWE pay a share of the cost of the dam repair that corresponds to the company’s share of global emissions. He and his lawyer based their claim on an old paragraph from the German Civil Code, §1004 BGB. Roughly speaking, it states that if someone interferes with another’s use of their property, “the owner can demand that the interferer remove the interference.”

For Saúl and his lawyer, this means that if RWE endangers the mountain guide’s property, and that is exactly what happens due to the flood risk, RWE must pay for a remedy. Whether this is actually the case must now be decided by German courts.

Saúl took a lot of time before deciding to file the lawsuit. He discussed the matter with his family. Saúl is a reserved man who speaks softly and chooses his words carefully. Pushing himself into the center of attention is not his thing.

But for decades he has been observing what climate change is doing to the Andes. As a mountain guide, he sees the changes up close: The glaciers of his homeland are shrinking, the landscape is drying up, pools and waterfalls are disappearing, and with them the birds and frogs that used to live near them. As the glaciers melt, the mountains of Huaraz are losing their most beautiful part, the ice and snow, Saúl says. But if only the bare rock remains, such a mountain is like a face without a smile.

The mountains of his homeland have a special meaning for Saúl. That is why he goes to court for them. Far above between their peaks is where he feels most at home, he says. The mountains give him work, which, in turn, allows him to feed his family. Even when he is at home, he always keeps an eye on them, because the clouds that gather at their peaks – or stay away – tell him if rain is coming.

But if the drought now destroys the beauty of the nature around Huaraz, tourists might stay away. Then Saúl and the other mountain guides of the town would no longer have any work. At the same time, Huaraz’s supply of drinking water is in jeopardy due to the melting glacier. So far, a regular flow of meltwater supplied the city, and in winter, snowfall high above maintained the glacier. But with warming, the cycle of snowfall, glaciation and melting is out of balance, and the glaciers continue to shrink. At some point, they could disappear altogether.

Saúl says that there are already years with virtually no rain. “If temperatures continue to rise and there is no water, how can our plants survive?” Potatoes and corn grow in his family’s garden. Even in Sharm el-Sheikh, he worries about the well-being of his plants. A few days ago, he called his family from Egypt. “They told me it’s still not raining,” he says. “A month ago, we sowed corn. It needs water now to grow.”

With his lawsuit, Saúl demands 20,000 euros from RWE for dam repairs. This is only a portion of what would be required to protect Huaraz and Saúl’s house from the flood risk. Not much money for RWE. But for the company, there is more at stake: If the company were ordered by a court to comply with Saúl’s demand, it would set a precedent that could be followed by further lawsuits.

In the first instance, the Essen Regional Court did not even accept his lawsuit for the taking of evidence. But in the second instance, a small sensation happened: In November 2017, the Higher Regional Court of Hamm accepted the lawsuit for further hearing including the taking of evidence.

Since then, progress has been slow, partly due to the Covid pandemic. Because in order to adequately assess all the evidence, the court scheduled a trip to Huaraz that could not take place until May 2022 because of the pandemic. “The judge and the experts also visited the lagoon,” Saúl says. “I was very happy to see him there, taking photos. And happy that we could get an authority to visit Huaraz and the mountains to make them understand the problem.”

But since then, it has been back to waiting to see what the court will make of it. Meanwhile, the ice continues to melt in the mountains around Huaraz. “The glacier is disappearing,” says Saúl. “And so are the lagoons that already exist. Instead, new ones are being created from the meltwater higher up.”

Seeing that his lawsuit can’t prevent the loss fills him with pain. “You grieve for the mountains,” he says. “Even more so when, like me as a mountain guide, you see the glacier so often at your work.” Whether he has achieved enough with his lawsuit? He does not ask himself that question. “Something has to be done,” Saúl says. “Otherwise, you are left with the guilt.” Alexandra Endres

The Thursday of the second COP week is like a miniature climate crisis: The sins of the past now take their revenge. We could have started looking for solutions much earlier, we should have reached compromises much faster. But no, and now look where we are. Those who dawdled over the last few days now have to work at high pressure. All decisions have to be made simultaneously, and time, coffee and patience are running out.

Sharm el-Sheikh is no exception. It is Thursday evening and it is still not clear where things are headed. What about the “implementation COP” and a way to finance climate damage? Are there serious promises to cut emissions and provide money for the poorest? In this issue, you’ll see that when it comes to the hottest issue, “loss and damage” financing, for example, ideas are still very far apart.

And there are good proposals. For example, the promise made in Glasgow to quickly reduce methane, a climate killer. It would save money and greenhouse gases, and is feasible. However, we are sobered by the fact that not much has really happened. It is far too difficult to break out of familiar patterns such as industrial agriculture.

In any case, we are preparing for overtime and “over days” in Sharm el-Sheikh. It does not matter anymore now. So the rule is: stay awake! Our latest Climate.Table will help you with that.

The success or failure of the “implementation conference” will be determined by whether there is a compromise on the structure and financing of loss and damage (L+D). Negotiators call this the “landing zone” where ministers can reach agreement. As of Thursday evening, however, the positions are still far apart.

The developing countries’ proposal is a maximum demand of the Global South. It provides for:

With this, the developing countries under China’s leadership set down their ideas and demands. It is not a compromise paper: Many elements are unacceptable for the industrialized countries.

How far the demands differ from the ideas of the industrialized countries is shown in the report of the mediators (co-facilitators), which was published by the latter on Nov. 15. Chilean Environment Minister Maisa Rojas and German Climate Envoy Jennifer Morgan are leading these explorations. They have compiled the conflicting sides.

The difference is shown, for example, in the fact that the developing countries want to adopt an “ad hoc body (working group)” immediately. The opposing position calls for “no specific group” and only “activities that can collectively be called a work program.” The differences are most evident in the goal of negotiations by 2024:

In short, these are the different positions:

Between the maximum positions of “decide everything immediately” and “just decide to talk,” there must be a middle ground for a compromise. Traditionally, the EU makes such proposals. It also has made clear that it does not see “the fund as a panacea,” as EU Climate Commissioner Frans Timmermans puts it. German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock also says COP27 “might not be the place to decide on a fund.”

In contrast, the EU seeks a “Sharm el Sheikh work program” lasting two years, according to an internal draft available to Climate Table. According to this, a new fund could be created under the UN climate convention, outside the convention or under the Paris Agreement. Existing funds like the GCF should be strengthened and more money raised outside the convention. By March 2023, the work program should take stock of what L+D funding is already available, which gaps exist, how best to fill them, and what additional sources of money exist.

However, the current debate still has many unanswered questions. For example, it is completely unclear what exactly loss and damage means. Where is the distinction between loss and damage and other damage, if money is to be paid for it? It is also unclear which countries should actually receive money. All developing countries? Only the group of least developed countries, the LDCs?

Critics of a quick fund decision at COP27, such as the Environmental Integrity Group (IEG), also point out that it makes little sense to decide on an “empty shell” that cannot begin its work. They pointed to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which took about six to eight years for the money to flow. Money for L+D, however, needs to flow quickly, they said. In this view, individual projects such as the “Global Shield” are better suited for this. Or a “loss and damage window” could be opened at the GCF.

Finally, the explosive question of who should pay into such a fund looms in the background. The G77/China proposal is clear: the industrialized countries. But the latter point out that the world has changed drastically since 1992, back when the Framework Convention on Climate Change was adopted. In the meantime, emerging economies such as China, Korea, Mexico, Brazil and Indonesia have become powerful economies – and also major emitters. Not to mention oil countries like Saudi Arabia and their wealth from fossil fuels.

Many experts and negotiators believe that these issues need to be resolved first before embarking on the adventure of a new financial mechanism. On the other hand, this debate is long overdue. It could have started at the latest with the establishment of the Warsaw Mechanism WIM in 2013.

Care and urgency are needed among many delegates. Saleemul Huq, veteran of the negotiations, advisor to vulnerable countries, and expert at the think tank ICCCAD has his own simple proposal: “This COP27 decides to establish a Loss and Damage Finance Facility.” Just that one sentence. And by deliberately using the vague term “facility”, it can mean many things. And then we will sort out all the details by COP28 in one year.

Mr. Bohn, what is the first thing Lula must do after taking office to protect the Amazon forest?

First, he must restore the existing forest protection laws and tighten them. He must strengthen the control authorities that ensure that these laws are complied with, and which were weakened under the previous government of Jair Bolsonaro. The punishments for illegal logging should also be increased.

Is the enthusiasm with which Lula was received here justified?

I thought it was unusual for diplomatic circles. But of course, not only diplomats are here. And the indigenous population groups in particular, who are also represented here, have high hopes for Lula. He promised here at COP27 to set up a special ministry for Brazil’s indigenous population, which I very much welcome in principle. We know from various studies that these indigenous groups are particularly capable of managing their forest sustainably. Therefore, it is good if their voice is properly heard in the further development of forest protection by the government.

Lula has promised to protect forests, but Brazil is still supposed to remain an agricultural power. How does that fit together?

It depends on the definition of agricultural economy. What is not possible is for Brazil to remain the country with the most cattle and the largest beef production. First, because of the climate impact of methane. But also because cattle farming requires a lot of land.

How else should agriculture change?

Traditional agriculture in Brazil consists of monocultures, for example extensive soybean fields. Agroforestry would be an alternative. This usually involves trees that bind nitrogen in the soil. Underneath, you have fruit trees like mango, banana or papaya. And underneath that you have coffee, wheat, root tubers. That way, many different things can be grown on a given area of land. That also reduces land use.

What is the current condition of the Amazon forest?

There are areas that are still quite stable. But at the edges, some areas have now gone from being a carbon sink to a carbon source. Clearing by fire plays a role there, of course. But even apart from the fires, the question is whether the forest in these regions is already on the edge.

Could Lula reverse this with the right forest conservation policies?

Once an original rainforest has been felled, it will never grow again in that place. But a secondary forest can be created, perhaps with other species that can grow well there under the conditions of climate change, such as increasing drought. Such a freshly replanted forest will be a carbon sink for decades.

What are the benefits of the forest conservation cooperation agreement just signed by Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia?

The agreement allows the three countries to pull together in international negotiations. If they coordinate their efforts, they will carry weight. Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia collectively own more than half of the tropical rainforest. The fact that they are cooperating is definitely good. But there are no more concrete agreements at the moment.

And the Forest Climate Leader Partnership (FCLP), which was also signed here at COP27 and of which Germany is a member, suffers because precisely these three countries are not part of it. Negotiations are currently underway to determine whether they will join or whether cooperation will be organized in another way.

How do you rate the FCLP?

In the FCLP, regular meetings at the highest ministerial level have been agreed to coordinate cooperation. That is positive. It also takes into account the importance of indigenous and local groups, which I very much support. The problem is the total amount of money available to the FCLP. Germany is involved with two billion euros, which is one third of the amount earmarked for the Green Climate Fund.

Can these collaborations really stop the trend toward global deforestation?

I would say it is going in the right direction. But to evaluate the cooperations, we have to wait another two or three years. Only then will we see with our satellite measurements what is really happening. Last year, we observed a 6.3 percent decrease in deforestation. But deforestation has to drop by 10 percent every year to reach the Glasgow target and stop deforestation by 2030.

Friedrich Bohn is an ecosystem modeler with a focus on forest research at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research UFZ in Leipzig. At COP27, he currently monitors developments in forest conservation there – and witnessed the enthusiasm for Brazil’s future president Lula da Silva.

More than 150 countries have now signed the Global Methane Pledge; together they want to reduce methane emissions by 30 percent by 2030 compared to 2020. John Kerry made the announcement Thursday at a ministerial meeting at COP27. On Thursday, heavyweights Kerry and Frans Timmermans praised the efforts of participating nations.

But: So far, only 50 countries submitted an action plan on how to reduce emissions. And no global interim results or new strategies were presented at the event. Instead, two “pathways” for methane reduction in agriculture and in the waste sector were presented – they complement the Energy Pathway, adopted in June 2022.

Furthermore, the contents of these pathways known so far are very small-scale. For example, 70 million dollars are to be provided for research into the digestion process of livestock. In addition, small farmers in the Global South are to be supported in reducing methane emissions.

Frans Timmermans said, “our biggest challenge, as I gather in many countries, is in the agricultural sector.” Emissions from this politically sensitive sector have been largely left out of the equation. Yet the 15 largest meat and dairy companies produce more methane emissions than Germany or Russia, according to a new study. Only six of the companies fully disclose their emissions. None of the participating countries have adequate plans to reduce emissions in this sector.

Large methane emitters such as China, India and Russia are not part of the Global Methane Pledge. They account for 30 percent of global methane emissions. It is unlikely that Russia, which is internationally isolated, will join such an initiative in the coming years.

Although the US and China did agree in Glasgow to tighten controls on methane emissions, and both countries wanted to develop methane strategies, bilateral climate cooperation, which included the methane issue, was suspended by China after Nancy Pelosi’s Taiwan visit. The People’s Republic did develop a methane plan, which is expected to be published this year.

But China’s chief climate negotiator Xie Zhenhua said during the first week of the COP that China’s ability to control methane emissions remains “weak.” Accordingly, China’s goal is to improve its ability to monitor and track emissions.

On Thursday, EU climate czar Frans Timmermans still expressed the hope that China would join the Global Methane Pledge. But that did not happen and is unlikely for the next few years. Most of China’s methane emissions come from the coal sector. It is more costly and complex to reduce these emissions than in the oil and gas sector.

Energy security ranks high on China’s agenda, competing with environmental goals such as reducing methane emissions. “I expect it will take a few more years for methane to become more significant in practice,” Cory Combs, energy and climate expert at consulting firm Trivium China, told Climate.Table.

Over short periods, methane is a far more harmful greenhouse gas to the climate than carbon dioxide. However, it remains in the atmosphere for a shorter period of time:

The signatories to the Global Methane Pledge account for over half of global methane emissions. They have enacted some measures and regulations. But overall, some gaps remain. Under current policies, global methane emissions are expected to increase more than 15 percent by 2030 if regulations are not tightened.

There is criticism of the EU methane regulation, for example. It does not include emissions from imported fossil fuels. Yet these emissions account for 75 to 90 percent of European methane emissions (Climate.Table reported).

Organizations such as Methane Action, the EIA Climate Campaign and the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development call for a binding methane agreement. Progress on emissions reductions has been too slow, they say. “To keep 1.5 alive, we’ll need more than voluntary frameworks and preliminary plans,” says Daphne Wysham, chair of Methane Action. “We need a binding agreement, with targets and timetables for getting record-high atmospheric methane concentrations back down to preindustrial levels.”

With a new report and a new world map of peatlands, researchers and the UN Environment Programme UNEP draw attention to an often-forgotten threat to the climate: carbon emissions from drained wetlands. After all, peatlands are the world’s threatened and largely ignored carbon reservoirs. On only about four percent of land area, they store about one-third of the carbon bound in the soil.

The new Global Peatlands Assessment provides information on the condition of wetlands, including:

A new version of the first map of the world’s peatlands, produced by the Greifswald Moor Centrum, is also part of the new report. It warns against further draining peatlands and using them for conventional agriculture. So far, drainage contributes four percent of global carbon emissions, twice as much as Germany. If the present drainage rate is maintained, the report warns, 41 percent of the carbon budget remaining for the 1.5-degree limit will be used up.

As countermeasures, “harmful operations” such as drainage would have to be prevented and stopped in particular. The protection of these areas should be improved through financial incentives. Fair and gender-responsive practices should be supported, as well as the management of these areas by indigenous communities. bpo

Saúl Luciano Lliuya took a three-and-a-half-day journey to get to COP27. Last Tuesday, early in the morning, the mountain guide left his home in the town of Huaraz in the Peruvian Andes. He traveled nine hours by bus to Lima. From there, he took a plane from Bogotá to Madrid to Istanbul, and finally to Sharm el-Sheikh. On Friday night, he arrived at the venue of the climate summit. For him, it is the third COP after Paris 2015 and Bonn 2017.

“I’m already thinking about how long the trip back will be,” Saúl says. But he hopes the hardship will be worth it. He wants to educate others at the climate summit and motivate them to do the same. Saúl Luciano Lliuya has sued a coal company that, according to the Carbon Majors Report, is responsible for about half a percent of industrial greenhouse gas emissions since 1988, making it one of the world’s largest emitters: the German company RWE.

In November 2015, shortly before the climate summit in Paris began, Saúl and his lawyer Roda Verheyen filed a lawsuit at the Essen Regional Court. Their argument: RWE is substantially responsible for global warming and its effects, which are already being felt in the Peruvian mountains today, for example through the melting of glaciers. Above Huaraz, the meltwater flows into a lagoon that continues to fill up. The lagoon is bordered by a dam. But the dam is in need of repair and has broken once already. Should this happen again, Saúl’s house in Huaraz could be flooded.

With his lawsuit, Saúl seeks to have RWE pay a share of the cost of the dam repair that corresponds to the company’s share of global emissions. He and his lawyer based their claim on an old paragraph from the German Civil Code, §1004 BGB. Roughly speaking, it states that if someone interferes with another’s use of their property, “the owner can demand that the interferer remove the interference.”

For Saúl and his lawyer, this means that if RWE endangers the mountain guide’s property, and that is exactly what happens due to the flood risk, RWE must pay for a remedy. Whether this is actually the case must now be decided by German courts.

Saúl took a lot of time before deciding to file the lawsuit. He discussed the matter with his family. Saúl is a reserved man who speaks softly and chooses his words carefully. Pushing himself into the center of attention is not his thing.

But for decades he has been observing what climate change is doing to the Andes. As a mountain guide, he sees the changes up close: The glaciers of his homeland are shrinking, the landscape is drying up, pools and waterfalls are disappearing, and with them the birds and frogs that used to live near them. As the glaciers melt, the mountains of Huaraz are losing their most beautiful part, the ice and snow, Saúl says. But if only the bare rock remains, such a mountain is like a face without a smile.

The mountains of his homeland have a special meaning for Saúl. That is why he goes to court for them. Far above between their peaks is where he feels most at home, he says. The mountains give him work, which, in turn, allows him to feed his family. Even when he is at home, he always keeps an eye on them, because the clouds that gather at their peaks – or stay away – tell him if rain is coming.

But if the drought now destroys the beauty of the nature around Huaraz, tourists might stay away. Then Saúl and the other mountain guides of the town would no longer have any work. At the same time, Huaraz’s supply of drinking water is in jeopardy due to the melting glacier. So far, a regular flow of meltwater supplied the city, and in winter, snowfall high above maintained the glacier. But with warming, the cycle of snowfall, glaciation and melting is out of balance, and the glaciers continue to shrink. At some point, they could disappear altogether.

Saúl says that there are already years with virtually no rain. “If temperatures continue to rise and there is no water, how can our plants survive?” Potatoes and corn grow in his family’s garden. Even in Sharm el-Sheikh, he worries about the well-being of his plants. A few days ago, he called his family from Egypt. “They told me it’s still not raining,” he says. “A month ago, we sowed corn. It needs water now to grow.”

With his lawsuit, Saúl demands 20,000 euros from RWE for dam repairs. This is only a portion of what would be required to protect Huaraz and Saúl’s house from the flood risk. Not much money for RWE. But for the company, there is more at stake: If the company were ordered by a court to comply with Saúl’s demand, it would set a precedent that could be followed by further lawsuits.

In the first instance, the Essen Regional Court did not even accept his lawsuit for the taking of evidence. But in the second instance, a small sensation happened: In November 2017, the Higher Regional Court of Hamm accepted the lawsuit for further hearing including the taking of evidence.

Since then, progress has been slow, partly due to the Covid pandemic. Because in order to adequately assess all the evidence, the court scheduled a trip to Huaraz that could not take place until May 2022 because of the pandemic. “The judge and the experts also visited the lagoon,” Saúl says. “I was very happy to see him there, taking photos. And happy that we could get an authority to visit Huaraz and the mountains to make them understand the problem.”

But since then, it has been back to waiting to see what the court will make of it. Meanwhile, the ice continues to melt in the mountains around Huaraz. “The glacier is disappearing,” says Saúl. “And so are the lagoons that already exist. Instead, new ones are being created from the meltwater higher up.”

Seeing that his lawsuit can’t prevent the loss fills him with pain. “You grieve for the mountains,” he says. “Even more so when, like me as a mountain guide, you see the glacier so often at your work.” Whether he has achieved enough with his lawsuit? He does not ask himself that question. “Something has to be done,” Saúl says. “Otherwise, you are left with the guilt.” Alexandra Endres