Shortly before COP29, the debate surrounding carbon capture and storage (CCS) is picking up speed again: The UK wants to subsidize the sector with almost 22 billion pounds, following the example of other countries. Environmentalists warn of the dangers of CO2 storage. Nico Beckert analyzes the British subsidy program and shows in which sectors the use of CCS makes sense at all.

In this issue, we also take a critical look at the Deutschlandticket. According to a new study, the climate benefits could be largely negated by the recently agreed price increase. And there are currently some rather gloomy climate signals from the industry: We explain why oil and gas giant BP is withdrawing its climate targets and Thyssenkrupp is reconsidering investments in green steel. And energy economist Claudia Kemfert explains how fossil fuel companies are sabotaging communication on the energy transition.

A look at Africa offers some hope. Many mini-grids have been installed there in recent years – and unlike in the past, they are largely based on renewable energies rather than diesel generators, as Samuel Ajala reports. You can also read how Brazil wants to raise billions for forest protection and we will, last but not least, introduce you to Dan Jørgensen, who is to become EU Energy Commissioner.

Stay tuned!

One month before the next climate conference in Baku (COP29), one of the most controversial climate technologies is gaining new momentum: the capture and storage of CO2 (CCS). The UK wants to promote CCS projects with subsidies of almost 22 billion pounds. Norway has put a new CO2 storage facility into operation with the Northern Lights project. And many other countries have launched subsidy programs or are working on CCS strategies.

CCS was already one of the most hotly debated topics at COP28 in Dubai. However, environmentalists are warning of the major dangers. A new leak at a CCS project in the USA seems to confirm their concerns.

The British government plans to fund CCS projects with 21.7 billion pounds over the next 25 years, as announced on Friday. The government wants to use the money to subsidize two undersea CO2 storage facilities and the associated infrastructure as well as three projects to capture CO2: A gas-fired power plant, a waste incineration plant and a hydrogen production plant.

The first CO2 is to be stored from 2028. In the future, the storage projects will store 8.5 million tons of CO2 per year, as reported by the Financial Times. By way of comparison, the UK’s annual CO2 emissions are currently a good 320 million tons per year.

The capture and storage of CO2 has recently been promoted by many countries:

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the UK Climate Change Committee, which advises the government on climate issues, CCS is necessary to meet climate targets. However, according to the IEA and many critics, its use should be limited to those sectors that have few alternatives to CO2 reduction – known in technical jargon as “hard-to-abate” sectors.

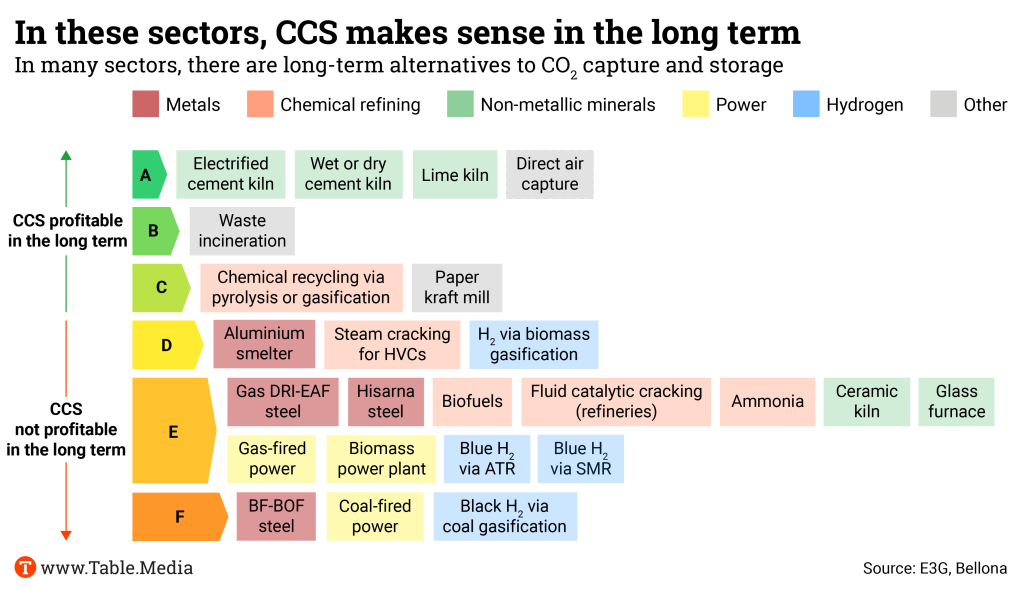

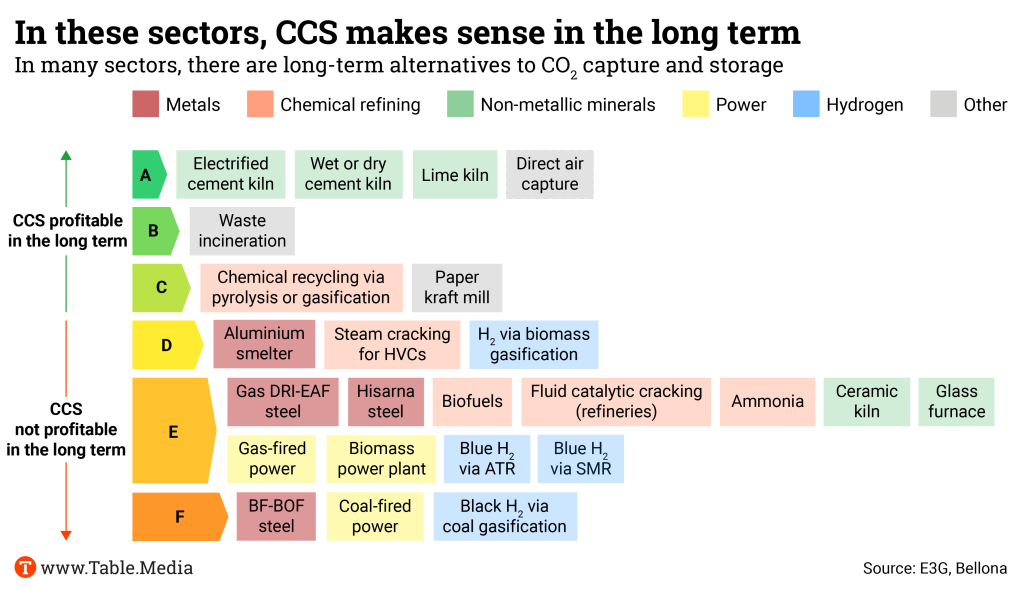

The British think tank E3G has developed a “CCS ladder” to show in which sectors the use of CCS would make the most sense and which sectors have more cost-effective alternatives. According to E3G, the use of CCS in gas-fired power plants, which the British government wants to support, is more of a “financial burden for the emitter”. The use of CCS in hydrogen production is also viewed critically. Doug Parr, political director of Greenpeace UK, criticizes: “Hydrogen from natural gas is not low-carbon and there is a danger that we are committing ourselves to second-rate solutions.”

In the short term (2030), CCS would therefore make sense for cement and lime production, some processes in the chemical industry, ammonia production, waste incineration, some hydrogen production processes and some applications in the steel sector, according to E3G. However, there will hardly be any significant storage capacities by 2030, as there are only very few CCS projects worldwide.

According to E3G, the use of CCS only makes economic sense in a few sectors in the long term, as there will be alternatives in many areas. The following sectors would therefore still have to rely on CCS in 2050:

However, as much as governments are subsidizing CCS as a supposed climate solution, the technology is still at the testing stage and problems regularly arise. In the USA, the agricultural company Archer-Daniels-Midland recently stopped storing CO2 from an ethanol factory underground. CO2 leaks had already occurred in March, and in September there were again problems with underground storage.

According to a recent Greenpeace study, many CCS projects have encountered similar problems:

Greenpeace criticizes the fact that CCS projects remain expensive as they can hardly be standardized. “Each project must analyze the individual geology of the storage site at great expense and develop tailor-made solutions“, the study says. The environmentalists criticize: If problems are already occurring “in the model country of Norway” in what is “probably the longest prepared CCS project in the world” (Sleipner), “one can imagine the risks that will be associated with CCS projects that are significantly larger and strongly profit-oriented”.

Decentralized small power grids based on photovoltaic power (“mini-grids”) are experiencing a boom worldwide. However, they are experiencing particularly strong growth in sub-Saharan Africa. There, the small grids supply people in remote areas with electricity and contribute to the fight against climate change.

This is according to a new report by the Sustainable Energy for All and Mini-Grids Partnership initiatives. According to the report, six times as many mini-grids were installed worldwide last year than in 2018 – a constant upward trend in mini-grid installations worldwide. The small grids are being used in Africa in particular.

Currently, 684 million people worldwide have no access to electricity. Mini-grids can help here, and they are becoming increasingly cleaner: according to the report, the proportion of diesel capacity in mini-grids fell from 42% to 29% between 2018 and 2024. In contrast, the share of solar systems rose from 14% to 59% in the same period.

“Over the past 15 years, funding for the mini-grid sector has increased significantly, with sub-Saharan Africa receiving the most funding from private investors, governments and development partners“, they say. The authors recommend continuing the success of mini-grids. Financial commitments and disbursements for mini-grids should continue to increase, including through:

Katlong Alex, energy analyst at the African Energy Council, explained in an interview with Table.Briefings that the rapid growth of mini-grid installations in sub-Saharan Africa represents a turning point for Africa. For Alex, they are “a practical solution to close the gap of unmet energy demand“. Decentralized access to energy eliminates the need for large investments in the power grid. “Recent advances in photovoltaic technology, battery storage systems and other mini-grid components have significantly reduced costs and increased reliability”, says Alex.

Why is sub-Saharan Africa leading the way in this development?

According to the report, the decline in diesel use in mini-grids is due to climate action efforts, rising operating costs for diesel and cheaper battery storage. The boom in photovoltaics (PV), on the other hand, is based on “advances in solar technology, affordability, scalability and supportive policy measures”. Added to this is the great potential for renewable energies: The continent is rich in renewable energy resources, especially solar, wind and hydropower. This is a solid foundation for the development of mini-grids based on renewables, says Desmond Dogara, Senior Manager of Energy Access at Clean Technology Hub, in an interview with Table.Briefings.

For energy transition expert Dogara, access to electricity enables local companies to work more efficiently and reduce costs by eliminating the need for diesel generators. “This boosts the local economy, creates jobs and increases income levels. Mini-grids provide households, schools and healthcare facilities in rural areas with a reliable supply of electricity.” This would have led to better educational opportunities, better healthcare and an overall higher standard of living.

The report also points to two important financial trends: total funding for mini-grids rose to over $2.5 billion in 2023. And private investment increased six-fold between 2015 and 2022 to almost $600 million. However, only 60 percent of the promised funds were actually disbursed. The rate varies greatly between donors. This makes it “necessary to monitor the process better and speed up disbursement”.

Increasingly, lenders are looking for guarantees to mitigate currency risk when investing in mini-grids. “These guarantees match revenues with financing costs, reducing the impact of exchange rate fluctuations. However, despite their importance, local currency financing remains limited as few lenders offer such options”, it says.

And the boom also has another disadvantage: according to Alex, solar modules, batteries and other valuable components are often at risk of theft and vandalism. This leads to higher costs and interruptions to the power supply. Monitoring and alarm systems could help to deter this.

The price increase for the Deutschlandticket could almost halve the climate benefit. This is the conclusion of a new scientific evaluation by scientists from the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC Berlin) as part of the Ariadne project. According to the scientists, the Deutschlandticket reduced CO2 emissions from the transport sector by “around 6.7 million tons” in the first year of its introduction (May 2023 to April 2024) – this corresponds to almost five percent of total CO2 emissions from the transport sector. The number of train journeys over 30 kilometers has “increased significantly” by 30 percent. Car use has decreased significantly – with a total of 7.6 percent fewer car kilometers driven.

However, the recently agreed price increase of nine euros to €58 from 2025 means that many people will switch back to the car, according to the forecast. According to Ariadne forecasts:

The researchers analyzed mobility data and created a model Germany for their study in which the Deutschlandticket was not introduced. This methodology makes it possible to actually investigate causal relationships and avoid factors that could influence the results in a before-and-after comparison. nib

The “foreseeable exceeding” of 1.5 degrees of global warming “should be communicated openly”. The German Climate Consortium (DKK) argues for this in a position paper, which is exclusively available to Table.Briefings. Such communication is important, as the “design of climate adaptation should be based on currently plausible temperature scenarios and prepare for them”. The DKK warns that the “political decisions taken so far to achieve climate policy goals” are “inadequate”. According to the largest network for the self-organization of German climate science, which currently has 27 member institutions, the “great social inequality” in particular stands in the way of decarbonization by 2050.

Shortly before the next climate conference (COP29) in Baku, the DKK criticizes above all the “still considerable investments in fossil fuels” such as coal and gas-fired power plants and new oil and gas reserves as well as climate-damaging subsidies. Net zero emissions are moving “further and further away”. According to DKK, it is possible to push the global temperature back below 1.5 degrees in the medium term (overshoot) after a rise above the 1.5-degree threshold through negative emissions. However, it is doubtful whether the technical and political conditions for the enormous CO2 removal associated with this are even in place. In addition, the subsequent reduction in temperature to 1.5 degrees after an overshoot would not reverse the negative consequences for nature and ecosystems. Destroyed glaciers and forests would not come back as a result. nib

The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) fund, proposed by Brazil at COP28, is in the final stages of conception and could raise up to four billion US dollars a year for rainforest conservation, according to one expert’s estimates. This was reported by the New York Times. The TFFF aims to provide economic incentives to protect forests and thus halt deforestation.

The Brazilian proposal envisages a fund worth $125 billion, which by some standards would make it the world’s largest pot of money for the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss. The Green Climate Fund, the world’s largest climate fund for financing projects in developing countries, has around half of the proposed capital.

The TFFF will work as follows:

Brazil wants to finalize the concept of the fund this year and also announce how it will be managed. It is to be introduced next year, but no firm financial commitments have yet been made. kul

Thyssenkrupp is considering discontinuing a three-billion-euro decarbonization project in Duisburg. The business plan of the steel division Thyssenkrupp Steel Europe (TKSE) – including plans to produce green steel – is to be reviewed. A halt to the hydrogen-based direct reduction project is also being discussed, Handelsblatt reported on Sunday, citing internal documents.

TKSE is facing a major transformation as part of the decarbonization process. So far, only a quarter of the capacities are on the state-subsidized transformation path, for which the traditional blast furnaces must be replaced by new plants. A new cost estimate is due soon for Duisburg, but Thyssenkrupp is still assuming that the direct reduction plant will be built.

The parent company Thyssenkrupp has long been in dispute over how much money the steel business needs to survive on its own – a dispute that led to the resignation of the division’s management at the end of August. The Czech billionaire Daniel Kretinsky’s acquisition of a 20 percent stake in TKSE could also make decarbonization more difficult. Among other things, Kretinsky owns several media outlets in the Czech News Center, which have repeatedly attracted attention with attacks against the climate movement and German climate policy. rtr/lb

The British oil company Beyond Petroleum (BP) is scaling back its energy transition strategy. BP is scrapping its goal of reducing oil and gas production by 2030. Instead, the company is aiming for new fossil fuel investments in the Middle East. CEO Murray Auchincloss is responding to unsettled investors. The share price had recently fallen.

When BP presented its strategy in 2020, it was the most ambitious in the sector. It envisaged reducing production by 40 percent by 2030 while rapidly expanding renewable energies. In February of last year, BP reduced the target to 25 percent and has now scrapped it altogether. BP is instead seeking new investments in the Middle East and the Gulf of Mexico to increase its oil and gas production, sources told Reuters. An updated strategy is to be presented at an investor meeting in February 2025.

BP remains committed to its goal of climate neutrality by 2050. In recent months, however, Auchincloss has halted investments in new offshore wind power and biofuel projects and reduced the number of low-carbon hydrogen projects from 30 to ten.

Rival Shell has also watered down its climate targets since CEO Wael Sawan took office in January, with Sawan selling off its power and renewables businesses and abandoning projects in offshore wind, biofuels and hydrogen. The change at both companies comes amid a renewed focus on energy security following Russia’s war of aggression, as well as supply chain issues and a sharp rise in renewable energy costs and interest rates. rtr/lb

Measures for sustainable food systems – such as the reduction of food waste or a diet based on plant-based protein – are rarely included in the countries’ national climate plans (NDCs). Other important measures for sustainable behavioral change, such as reducing air travel, are also often not mentioned. This is the conclusion of a recent working paper by the World Resources Institute (WRI), which analyzes behavioral change measures in the NDCs of the 20 countries with the highest emissions.

Accordingly, the promotion of electric vehicles, more public transport and energy savings in households are most frequently included in the NDCs. The measures prioritized in the NDCs often do not match the potential for emission reductions: For example, according to one study, a plant-based diet could reduce emissions from the food sector by up to 73 percent. Nevertheless, measures towards a food transition are rarely considered.

In the NDCs examined, behavioral changes are mostly promoted by improving infrastructure and services. The WRI also recommends the use of other instruments such as financial incentives or the improved provision of information, for example through energy certificates or labels. kul

Geopolitical instability and social inequality in the introduction of measures to curb climate change in Europe are the greatest challenges to achieving the European climate targets. A study by Brussels-based think tank Bruegel has examined the EU Commission’s target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 90 percent by 2040 compared to 1990 levels. The targets are technically feasible, as many clean technologies are already ready for the market and are more cost-effective.

However, the authors identify four main risks that could jeopardize the achievement of targets:

The authors therefore call for a climate and energy policy framework for 2040 that is resilient to such risks. The EU should place distributional issues at the center of its climate policy and develop an emissions reduction strategy that monitors geo-economic and technological risk factors. In addition, contingency plans are needed to prevent the aforementioned risks from jeopardizing climate targets. luk

In theory, successful communication is a simple four-stage process:

In 2008, Barack Obama demonstrated how political communication can succeed in this way in a democratic election campaign with his successful “Yes We Can” campaign.

Climate and energy transition communication has also been communicated in this way for decades. We look back on 50 years of climate research, which has shown practicable solutions to the threat of global warming. And we look back on 30 years of energy transition with impressive success stories – in 1994, Angela Merkel, then Minister of the Environment, predicted: “Sun, water and wind will not be able to cover more than four percent of our electricity needs in the long term”. Today, renewable energies account for over 60 percent of electricity generation in Germany.

But there can be no talk of success. Instead of confidence in the opportunities of a different climate future, resistance to any kind of ecological transformation has only grown. Germany is lagging behind many climate targets. “The Greens” are seen as the scapegoat for any kind of crisis. Climate activists are increasingly isolated and sometimes criminalized. This can’t just be due to a lack of positive images or target group-specific references. Instead of theorizing about the initial question “How can the energy transition be communicated successfully?”, we would therefore be better off talking about how and why energy transition communication is failing so terribly.

The answer is not actually new. However, the public is only gradually becoming aware of the perfidious methods used by a few very powerful profiteers of the fossil fuel industries to influence the political discourse worldwide.

In 2015, investigative media revealed that oil and gas companies like ExxonMobil knew decades ago that their product would have a catastrophic impact on the climate. But instead of warning the world and changing their business model, they spent billions to mislead the public and block climate action. They engaged in social “climate gaslighting” – a form of manipulative behavior that permanently fuels doubt about reality.

The perfidious methods of these “merchants of doubt” were first revealed by science historian Naomi Oreskes using the US tobacco industry as an example. The industry had been deceiving the public about the risks of smoking since the 1950s. As a result of Oreskes’ work, the companies involved were sued by the US government for organized crime and in August 2006 were found guilty of conspiracy to defraud for decades.

The same methods are also used by the fossil fuel industry, albeit with an expanded toolbox. A majority of the population is fundamentally in favor of climate protection. This is why people are now being unsettled by aggressive disruptive communication when it comes to specific political measures. Regardless of whether it’s the transport, energy or heating transition – the respective project is always “too immature”, “too expensive”, “too ideological”, “not marketable enough”, “too elitist”, too this, too that.

At the same time, discussions about factual issues are being shifted to emotional levels of conflict: Instead of (cheap) solar energy instead of (expensive) nuclear power, people are ranting about rich dentists and their photovoltaic-covered villas; instead of modern heat pumps versus outdated oil heating, the public is discussing allegedly arbitrary “heating bans”.

The fossil fuel players are not interested in a constructive dialog. Any debate is therefore as pointless as trying to play chess with a pigeon: It will just knock over all the pieces (the arguments), poop on the board (the discussion) and strut around as if it had won.

The master of this kind of pigeon chess is Vladimir Putin, whose power as president is primarily based on state revenues from Russia’s vast fossil resources. As the strongest opponent of a global climate policy, he uses perfidious methods to play off the diverse forces of open society against each other through propaganda and fake news. In this way, he secures his (market) power and weakens the defensive power of Western democracies. In doing so, he seeks alliances with other fossil autocrats in Iran, Venezuela, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan and does not shy away from wars that violate international law. The world is now paying the price for more extreme weather events and other climate catastrophes; it has to cope with more and more wars and refugees, while Big Oil & Gas is raking in record profits.

No. It’s no longer about climate or energy transition communication. It’s about politics and power. It’s about democracy. It’s about peace. And we finally need strategies to prevent all of this from failing.

Claudia Kemfert heads the Energy, Transport and Environment Department at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) and is Professor of Energy Economics and Energy Policy at Leuphana University Lüneburg. At this week’s annual conference of the Renewable Energy Research Association (FEVV), she will talk about why climate communication has often failed so far and how this can be improved.

Dan Jørgensen can sell politics well, says Linda Kalcher about the designated Energy Commissioner from Denmark. Kalcher is the founder of the Brussels think tank Strategic Perspectives and knows Jørgensen from his time as a Member of the European Parliament. His network extends far beyond Europe’s borders, which is why Jørgensen could possibly give the portfolio a stronger external impact.

As Energy Commissioner, his task will be to complete Europe’s Energy Union and make it independent of Russian energy supplies. He is to modernize the grid infrastructure and reduce energy prices, which would benefit both consumers and make the industry more competitive internationally. Not an easy task, but Jørgensen has experience with complicated challenges in the energy sector.

As Denmark’s Minister for Development, he co-managed Europe’s international energy partnerships. Previously, as Minister of Climate and Energy, he co-founded the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA) with Costa Rica during the UN Climate Conference in Glasgow (COP26) to promote the phase-out of fossil fuels in both industrialized and developing countries. At COP28 in Dubai, he negotiated on behalf of Denmark, alongside other European ministers, to include the phase-out of fossil fuels in the conference’s final document.

In his new role, Jørgensen will have to act within the EU rather than externally. But this will not make things any less complicated. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has also tasked him with driving forward the ramp-up of small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) and carbon capture and storage (CCS). The use and promotion of nuclear energy in particular is highly controversial in Europe. Jørgensen will have to mediate, especially between Paris and Berlin. In the past, he has already proven that he can achieve results in the role of broker.

At ministerial level, he led the talks on the global stocktake, the most important text of the last climate conference, in the run-up to COP28 in Dubai. Until his nomination as EU Commissioner, he also acted as a mediator for the new global climate finance target, the most important document of the next COP in Baku. The crux of these mediator roles – known as facilitators in COP jargon – is to mediate between diametrically opposed positions. “Jørgensen has always done this well”, confirms Kalcher. He is communicative, talks to all sides and is committed to finding solutions. Something his predecessor Kadri Simson was not exactly known for. He is also a workhorse, says Kalcher. “He starts at 6 in the morning and is only finished at 11 in the evening.”

He is less familiar with the second part of his portfolio. Jørgensen is also Housing Commissioner. Affordable housing, lower construction costs and the development of a pan-European investment platform are among his responsibilities there. He will have to learn the ropes. The implementation of von der Leyen’s plans also requires a great deal of skill with the competencies of the European institutions. This is because urban development and housing policy are in the hands of the member states.

Dan Jørgensen will work primarily with the designated Competition Commissioner Teresa Ribera and Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra. He knows both of them well. “They get on well together,” says Kalcher. At COP28 in Dubai, they negotiated side by side for Europe. In Brussels, they are now to work together on the decarbonization of European industry. Jørgensen will have to draw up plans for affordable energy prices and the electrification and supply of clean energy to industry. Lukas Knigge

Shortly before COP29, the debate surrounding carbon capture and storage (CCS) is picking up speed again: The UK wants to subsidize the sector with almost 22 billion pounds, following the example of other countries. Environmentalists warn of the dangers of CO2 storage. Nico Beckert analyzes the British subsidy program and shows in which sectors the use of CCS makes sense at all.

In this issue, we also take a critical look at the Deutschlandticket. According to a new study, the climate benefits could be largely negated by the recently agreed price increase. And there are currently some rather gloomy climate signals from the industry: We explain why oil and gas giant BP is withdrawing its climate targets and Thyssenkrupp is reconsidering investments in green steel. And energy economist Claudia Kemfert explains how fossil fuel companies are sabotaging communication on the energy transition.

A look at Africa offers some hope. Many mini-grids have been installed there in recent years – and unlike in the past, they are largely based on renewable energies rather than diesel generators, as Samuel Ajala reports. You can also read how Brazil wants to raise billions for forest protection and we will, last but not least, introduce you to Dan Jørgensen, who is to become EU Energy Commissioner.

Stay tuned!

One month before the next climate conference in Baku (COP29), one of the most controversial climate technologies is gaining new momentum: the capture and storage of CO2 (CCS). The UK wants to promote CCS projects with subsidies of almost 22 billion pounds. Norway has put a new CO2 storage facility into operation with the Northern Lights project. And many other countries have launched subsidy programs or are working on CCS strategies.

CCS was already one of the most hotly debated topics at COP28 in Dubai. However, environmentalists are warning of the major dangers. A new leak at a CCS project in the USA seems to confirm their concerns.

The British government plans to fund CCS projects with 21.7 billion pounds over the next 25 years, as announced on Friday. The government wants to use the money to subsidize two undersea CO2 storage facilities and the associated infrastructure as well as three projects to capture CO2: A gas-fired power plant, a waste incineration plant and a hydrogen production plant.

The first CO2 is to be stored from 2028. In the future, the storage projects will store 8.5 million tons of CO2 per year, as reported by the Financial Times. By way of comparison, the UK’s annual CO2 emissions are currently a good 320 million tons per year.

The capture and storage of CO2 has recently been promoted by many countries:

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the UK Climate Change Committee, which advises the government on climate issues, CCS is necessary to meet climate targets. However, according to the IEA and many critics, its use should be limited to those sectors that have few alternatives to CO2 reduction – known in technical jargon as “hard-to-abate” sectors.

The British think tank E3G has developed a “CCS ladder” to show in which sectors the use of CCS would make the most sense and which sectors have more cost-effective alternatives. According to E3G, the use of CCS in gas-fired power plants, which the British government wants to support, is more of a “financial burden for the emitter”. The use of CCS in hydrogen production is also viewed critically. Doug Parr, political director of Greenpeace UK, criticizes: “Hydrogen from natural gas is not low-carbon and there is a danger that we are committing ourselves to second-rate solutions.”

In the short term (2030), CCS would therefore make sense for cement and lime production, some processes in the chemical industry, ammonia production, waste incineration, some hydrogen production processes and some applications in the steel sector, according to E3G. However, there will hardly be any significant storage capacities by 2030, as there are only very few CCS projects worldwide.

According to E3G, the use of CCS only makes economic sense in a few sectors in the long term, as there will be alternatives in many areas. The following sectors would therefore still have to rely on CCS in 2050:

However, as much as governments are subsidizing CCS as a supposed climate solution, the technology is still at the testing stage and problems regularly arise. In the USA, the agricultural company Archer-Daniels-Midland recently stopped storing CO2 from an ethanol factory underground. CO2 leaks had already occurred in March, and in September there were again problems with underground storage.

According to a recent Greenpeace study, many CCS projects have encountered similar problems:

Greenpeace criticizes the fact that CCS projects remain expensive as they can hardly be standardized. “Each project must analyze the individual geology of the storage site at great expense and develop tailor-made solutions“, the study says. The environmentalists criticize: If problems are already occurring “in the model country of Norway” in what is “probably the longest prepared CCS project in the world” (Sleipner), “one can imagine the risks that will be associated with CCS projects that are significantly larger and strongly profit-oriented”.

Decentralized small power grids based on photovoltaic power (“mini-grids”) are experiencing a boom worldwide. However, they are experiencing particularly strong growth in sub-Saharan Africa. There, the small grids supply people in remote areas with electricity and contribute to the fight against climate change.

This is according to a new report by the Sustainable Energy for All and Mini-Grids Partnership initiatives. According to the report, six times as many mini-grids were installed worldwide last year than in 2018 – a constant upward trend in mini-grid installations worldwide. The small grids are being used in Africa in particular.

Currently, 684 million people worldwide have no access to electricity. Mini-grids can help here, and they are becoming increasingly cleaner: according to the report, the proportion of diesel capacity in mini-grids fell from 42% to 29% between 2018 and 2024. In contrast, the share of solar systems rose from 14% to 59% in the same period.

“Over the past 15 years, funding for the mini-grid sector has increased significantly, with sub-Saharan Africa receiving the most funding from private investors, governments and development partners“, they say. The authors recommend continuing the success of mini-grids. Financial commitments and disbursements for mini-grids should continue to increase, including through:

Katlong Alex, energy analyst at the African Energy Council, explained in an interview with Table.Briefings that the rapid growth of mini-grid installations in sub-Saharan Africa represents a turning point for Africa. For Alex, they are “a practical solution to close the gap of unmet energy demand“. Decentralized access to energy eliminates the need for large investments in the power grid. “Recent advances in photovoltaic technology, battery storage systems and other mini-grid components have significantly reduced costs and increased reliability”, says Alex.

Why is sub-Saharan Africa leading the way in this development?

According to the report, the decline in diesel use in mini-grids is due to climate action efforts, rising operating costs for diesel and cheaper battery storage. The boom in photovoltaics (PV), on the other hand, is based on “advances in solar technology, affordability, scalability and supportive policy measures”. Added to this is the great potential for renewable energies: The continent is rich in renewable energy resources, especially solar, wind and hydropower. This is a solid foundation for the development of mini-grids based on renewables, says Desmond Dogara, Senior Manager of Energy Access at Clean Technology Hub, in an interview with Table.Briefings.

For energy transition expert Dogara, access to electricity enables local companies to work more efficiently and reduce costs by eliminating the need for diesel generators. “This boosts the local economy, creates jobs and increases income levels. Mini-grids provide households, schools and healthcare facilities in rural areas with a reliable supply of electricity.” This would have led to better educational opportunities, better healthcare and an overall higher standard of living.

The report also points to two important financial trends: total funding for mini-grids rose to over $2.5 billion in 2023. And private investment increased six-fold between 2015 and 2022 to almost $600 million. However, only 60 percent of the promised funds were actually disbursed. The rate varies greatly between donors. This makes it “necessary to monitor the process better and speed up disbursement”.

Increasingly, lenders are looking for guarantees to mitigate currency risk when investing in mini-grids. “These guarantees match revenues with financing costs, reducing the impact of exchange rate fluctuations. However, despite their importance, local currency financing remains limited as few lenders offer such options”, it says.

And the boom also has another disadvantage: according to Alex, solar modules, batteries and other valuable components are often at risk of theft and vandalism. This leads to higher costs and interruptions to the power supply. Monitoring and alarm systems could help to deter this.

The price increase for the Deutschlandticket could almost halve the climate benefit. This is the conclusion of a new scientific evaluation by scientists from the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC Berlin) as part of the Ariadne project. According to the scientists, the Deutschlandticket reduced CO2 emissions from the transport sector by “around 6.7 million tons” in the first year of its introduction (May 2023 to April 2024) – this corresponds to almost five percent of total CO2 emissions from the transport sector. The number of train journeys over 30 kilometers has “increased significantly” by 30 percent. Car use has decreased significantly – with a total of 7.6 percent fewer car kilometers driven.

However, the recently agreed price increase of nine euros to €58 from 2025 means that many people will switch back to the car, according to the forecast. According to Ariadne forecasts:

The researchers analyzed mobility data and created a model Germany for their study in which the Deutschlandticket was not introduced. This methodology makes it possible to actually investigate causal relationships and avoid factors that could influence the results in a before-and-after comparison. nib

The “foreseeable exceeding” of 1.5 degrees of global warming “should be communicated openly”. The German Climate Consortium (DKK) argues for this in a position paper, which is exclusively available to Table.Briefings. Such communication is important, as the “design of climate adaptation should be based on currently plausible temperature scenarios and prepare for them”. The DKK warns that the “political decisions taken so far to achieve climate policy goals” are “inadequate”. According to the largest network for the self-organization of German climate science, which currently has 27 member institutions, the “great social inequality” in particular stands in the way of decarbonization by 2050.

Shortly before the next climate conference (COP29) in Baku, the DKK criticizes above all the “still considerable investments in fossil fuels” such as coal and gas-fired power plants and new oil and gas reserves as well as climate-damaging subsidies. Net zero emissions are moving “further and further away”. According to DKK, it is possible to push the global temperature back below 1.5 degrees in the medium term (overshoot) after a rise above the 1.5-degree threshold through negative emissions. However, it is doubtful whether the technical and political conditions for the enormous CO2 removal associated with this are even in place. In addition, the subsequent reduction in temperature to 1.5 degrees after an overshoot would not reverse the negative consequences for nature and ecosystems. Destroyed glaciers and forests would not come back as a result. nib

The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) fund, proposed by Brazil at COP28, is in the final stages of conception and could raise up to four billion US dollars a year for rainforest conservation, according to one expert’s estimates. This was reported by the New York Times. The TFFF aims to provide economic incentives to protect forests and thus halt deforestation.

The Brazilian proposal envisages a fund worth $125 billion, which by some standards would make it the world’s largest pot of money for the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss. The Green Climate Fund, the world’s largest climate fund for financing projects in developing countries, has around half of the proposed capital.

The TFFF will work as follows:

Brazil wants to finalize the concept of the fund this year and also announce how it will be managed. It is to be introduced next year, but no firm financial commitments have yet been made. kul

Thyssenkrupp is considering discontinuing a three-billion-euro decarbonization project in Duisburg. The business plan of the steel division Thyssenkrupp Steel Europe (TKSE) – including plans to produce green steel – is to be reviewed. A halt to the hydrogen-based direct reduction project is also being discussed, Handelsblatt reported on Sunday, citing internal documents.

TKSE is facing a major transformation as part of the decarbonization process. So far, only a quarter of the capacities are on the state-subsidized transformation path, for which the traditional blast furnaces must be replaced by new plants. A new cost estimate is due soon for Duisburg, but Thyssenkrupp is still assuming that the direct reduction plant will be built.

The parent company Thyssenkrupp has long been in dispute over how much money the steel business needs to survive on its own – a dispute that led to the resignation of the division’s management at the end of August. The Czech billionaire Daniel Kretinsky’s acquisition of a 20 percent stake in TKSE could also make decarbonization more difficult. Among other things, Kretinsky owns several media outlets in the Czech News Center, which have repeatedly attracted attention with attacks against the climate movement and German climate policy. rtr/lb

The British oil company Beyond Petroleum (BP) is scaling back its energy transition strategy. BP is scrapping its goal of reducing oil and gas production by 2030. Instead, the company is aiming for new fossil fuel investments in the Middle East. CEO Murray Auchincloss is responding to unsettled investors. The share price had recently fallen.

When BP presented its strategy in 2020, it was the most ambitious in the sector. It envisaged reducing production by 40 percent by 2030 while rapidly expanding renewable energies. In February of last year, BP reduced the target to 25 percent and has now scrapped it altogether. BP is instead seeking new investments in the Middle East and the Gulf of Mexico to increase its oil and gas production, sources told Reuters. An updated strategy is to be presented at an investor meeting in February 2025.

BP remains committed to its goal of climate neutrality by 2050. In recent months, however, Auchincloss has halted investments in new offshore wind power and biofuel projects and reduced the number of low-carbon hydrogen projects from 30 to ten.

Rival Shell has also watered down its climate targets since CEO Wael Sawan took office in January, with Sawan selling off its power and renewables businesses and abandoning projects in offshore wind, biofuels and hydrogen. The change at both companies comes amid a renewed focus on energy security following Russia’s war of aggression, as well as supply chain issues and a sharp rise in renewable energy costs and interest rates. rtr/lb

Measures for sustainable food systems – such as the reduction of food waste or a diet based on plant-based protein – are rarely included in the countries’ national climate plans (NDCs). Other important measures for sustainable behavioral change, such as reducing air travel, are also often not mentioned. This is the conclusion of a recent working paper by the World Resources Institute (WRI), which analyzes behavioral change measures in the NDCs of the 20 countries with the highest emissions.

Accordingly, the promotion of electric vehicles, more public transport and energy savings in households are most frequently included in the NDCs. The measures prioritized in the NDCs often do not match the potential for emission reductions: For example, according to one study, a plant-based diet could reduce emissions from the food sector by up to 73 percent. Nevertheless, measures towards a food transition are rarely considered.

In the NDCs examined, behavioral changes are mostly promoted by improving infrastructure and services. The WRI also recommends the use of other instruments such as financial incentives or the improved provision of information, for example through energy certificates or labels. kul

Geopolitical instability and social inequality in the introduction of measures to curb climate change in Europe are the greatest challenges to achieving the European climate targets. A study by Brussels-based think tank Bruegel has examined the EU Commission’s target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 90 percent by 2040 compared to 1990 levels. The targets are technically feasible, as many clean technologies are already ready for the market and are more cost-effective.

However, the authors identify four main risks that could jeopardize the achievement of targets:

The authors therefore call for a climate and energy policy framework for 2040 that is resilient to such risks. The EU should place distributional issues at the center of its climate policy and develop an emissions reduction strategy that monitors geo-economic and technological risk factors. In addition, contingency plans are needed to prevent the aforementioned risks from jeopardizing climate targets. luk

In theory, successful communication is a simple four-stage process:

In 2008, Barack Obama demonstrated how political communication can succeed in this way in a democratic election campaign with his successful “Yes We Can” campaign.

Climate and energy transition communication has also been communicated in this way for decades. We look back on 50 years of climate research, which has shown practicable solutions to the threat of global warming. And we look back on 30 years of energy transition with impressive success stories – in 1994, Angela Merkel, then Minister of the Environment, predicted: “Sun, water and wind will not be able to cover more than four percent of our electricity needs in the long term”. Today, renewable energies account for over 60 percent of electricity generation in Germany.

But there can be no talk of success. Instead of confidence in the opportunities of a different climate future, resistance to any kind of ecological transformation has only grown. Germany is lagging behind many climate targets. “The Greens” are seen as the scapegoat for any kind of crisis. Climate activists are increasingly isolated and sometimes criminalized. This can’t just be due to a lack of positive images or target group-specific references. Instead of theorizing about the initial question “How can the energy transition be communicated successfully?”, we would therefore be better off talking about how and why energy transition communication is failing so terribly.

The answer is not actually new. However, the public is only gradually becoming aware of the perfidious methods used by a few very powerful profiteers of the fossil fuel industries to influence the political discourse worldwide.

In 2015, investigative media revealed that oil and gas companies like ExxonMobil knew decades ago that their product would have a catastrophic impact on the climate. But instead of warning the world and changing their business model, they spent billions to mislead the public and block climate action. They engaged in social “climate gaslighting” – a form of manipulative behavior that permanently fuels doubt about reality.

The perfidious methods of these “merchants of doubt” were first revealed by science historian Naomi Oreskes using the US tobacco industry as an example. The industry had been deceiving the public about the risks of smoking since the 1950s. As a result of Oreskes’ work, the companies involved were sued by the US government for organized crime and in August 2006 were found guilty of conspiracy to defraud for decades.

The same methods are also used by the fossil fuel industry, albeit with an expanded toolbox. A majority of the population is fundamentally in favor of climate protection. This is why people are now being unsettled by aggressive disruptive communication when it comes to specific political measures. Regardless of whether it’s the transport, energy or heating transition – the respective project is always “too immature”, “too expensive”, “too ideological”, “not marketable enough”, “too elitist”, too this, too that.

At the same time, discussions about factual issues are being shifted to emotional levels of conflict: Instead of (cheap) solar energy instead of (expensive) nuclear power, people are ranting about rich dentists and their photovoltaic-covered villas; instead of modern heat pumps versus outdated oil heating, the public is discussing allegedly arbitrary “heating bans”.

The fossil fuel players are not interested in a constructive dialog. Any debate is therefore as pointless as trying to play chess with a pigeon: It will just knock over all the pieces (the arguments), poop on the board (the discussion) and strut around as if it had won.

The master of this kind of pigeon chess is Vladimir Putin, whose power as president is primarily based on state revenues from Russia’s vast fossil resources. As the strongest opponent of a global climate policy, he uses perfidious methods to play off the diverse forces of open society against each other through propaganda and fake news. In this way, he secures his (market) power and weakens the defensive power of Western democracies. In doing so, he seeks alliances with other fossil autocrats in Iran, Venezuela, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan and does not shy away from wars that violate international law. The world is now paying the price for more extreme weather events and other climate catastrophes; it has to cope with more and more wars and refugees, while Big Oil & Gas is raking in record profits.

No. It’s no longer about climate or energy transition communication. It’s about politics and power. It’s about democracy. It’s about peace. And we finally need strategies to prevent all of this from failing.

Claudia Kemfert heads the Energy, Transport and Environment Department at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) and is Professor of Energy Economics and Energy Policy at Leuphana University Lüneburg. At this week’s annual conference of the Renewable Energy Research Association (FEVV), she will talk about why climate communication has often failed so far and how this can be improved.

Dan Jørgensen can sell politics well, says Linda Kalcher about the designated Energy Commissioner from Denmark. Kalcher is the founder of the Brussels think tank Strategic Perspectives and knows Jørgensen from his time as a Member of the European Parliament. His network extends far beyond Europe’s borders, which is why Jørgensen could possibly give the portfolio a stronger external impact.

As Energy Commissioner, his task will be to complete Europe’s Energy Union and make it independent of Russian energy supplies. He is to modernize the grid infrastructure and reduce energy prices, which would benefit both consumers and make the industry more competitive internationally. Not an easy task, but Jørgensen has experience with complicated challenges in the energy sector.

As Denmark’s Minister for Development, he co-managed Europe’s international energy partnerships. Previously, as Minister of Climate and Energy, he co-founded the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA) with Costa Rica during the UN Climate Conference in Glasgow (COP26) to promote the phase-out of fossil fuels in both industrialized and developing countries. At COP28 in Dubai, he negotiated on behalf of Denmark, alongside other European ministers, to include the phase-out of fossil fuels in the conference’s final document.

In his new role, Jørgensen will have to act within the EU rather than externally. But this will not make things any less complicated. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has also tasked him with driving forward the ramp-up of small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) and carbon capture and storage (CCS). The use and promotion of nuclear energy in particular is highly controversial in Europe. Jørgensen will have to mediate, especially between Paris and Berlin. In the past, he has already proven that he can achieve results in the role of broker.

At ministerial level, he led the talks on the global stocktake, the most important text of the last climate conference, in the run-up to COP28 in Dubai. Until his nomination as EU Commissioner, he also acted as a mediator for the new global climate finance target, the most important document of the next COP in Baku. The crux of these mediator roles – known as facilitators in COP jargon – is to mediate between diametrically opposed positions. “Jørgensen has always done this well”, confirms Kalcher. He is communicative, talks to all sides and is committed to finding solutions. Something his predecessor Kadri Simson was not exactly known for. He is also a workhorse, says Kalcher. “He starts at 6 in the morning and is only finished at 11 in the evening.”

He is less familiar with the second part of his portfolio. Jørgensen is also Housing Commissioner. Affordable housing, lower construction costs and the development of a pan-European investment platform are among his responsibilities there. He will have to learn the ropes. The implementation of von der Leyen’s plans also requires a great deal of skill with the competencies of the European institutions. This is because urban development and housing policy are in the hands of the member states.

Dan Jørgensen will work primarily with the designated Competition Commissioner Teresa Ribera and Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra. He knows both of them well. “They get on well together,” says Kalcher. At COP28 in Dubai, they negotiated side by side for Europe. In Brussels, they are now to work together on the decarbonization of European industry. Jørgensen will have to draw up plans for affordable energy prices and the electrification and supply of clean energy to industry. Lukas Knigge