Once again, everything came to a grinding halt shortly before the end of the conference in Dubai. We’ve seen it before: Saudi Arabia and the oil lobby regularly slow down the COP machine. On the one hand, they block ambitious formulations and targets. On the other hand, they have enforced the consensus principle, which slows down every decision. Bernhard Pötter reports on the underlying reasons.

A lot is being done in Dubai to convince developing countries to transition faster away from fossil fuels. “But many simply cannot afford the energy transition,” says Achim Steiner, head of the UN Development Program (UNDP), in today’s interview. Steiner calls for more concessionary loans – and explains what the Global North can learn from the South.

The main sticking point in the negotiations at COP28 is the energy package: Today’s background information takes another look at the goals of tripling renewable energies by 2030 and improving energy efficiency. Significant investment in power grids and far greater efforts to improve efficiency are needed to achieve this. And the wind sector would have to massively expand its production capacities.

Things are now getting exciting in Dubai. We expect a final decision to be made today, Wednesday, on if and what the outcome of COP28 will look like. We will then be back with all the interesting details for you.

The deadlock at COP28 in Dubai over a controversial final declaration on the Global Stocktake (GST) has rekindled an age-old debate in the UN climate negotiations: Why doesn’t COP vote by majority? And it draws attention to the countries of the Arab world, which are apparently among the biggest obstructionists at the conference. They are also the reason why the conferences do not make majority decisions.

Contrary to what is often believed, decisions at the COP do not have to be made unanimously – but by consensus. This means that not everyone has to agree, but no one is allowed to object openly. So much for the theory. The practice of the negotiations has shown: If it is late enough at the final plenary, if the assembly is ready for a decision and a stubborn country is not a political heavyweight, a COP president can sometimes bypass it. This is what happened to Bolivia on the last night of Cancún 2010 at COP16.

The COP does not decide by majority vote because, even after 31 years of the Framework Convention on Climate Change, it has not yet adopted any “rules and procedures” for this. Together with OPEC, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait prevented the first attempt to do so in 1995. Since then, climate conferences have made do with the lowest common denominator: the consensus principle. “Entrenching consensus was a master stroke of the fossil fuel lobby in the early days,” historian Joanna Depledge, a specialist on climate talks from Cambridge University, told the Associated Press. “By that I mean Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, backed by U.S.-based oil lobbyists. It was OPEC who insisted on consensus – and because no agreement could be reached on a voting rule, decision making is now indeed by consensus, by default.”

Attempts to change the rules also failed in 1996 and 2011. Such a democratic procedure would also not suit some big players such as the USA or China – surely a majority of countries could be found to force the USA to pay more climate aid by holding a vote, for example.

Recently, former US Vice President Al Gore and former Irish Prime Minister Mary Robinson have called for a change to majority voting. The background: Observers and delegates have reported that mainly countries of the Arab group around Saudi Arabia are resisting a resolution to end fossil fuels at COP28. It is said that around 80 to 85 percent of the countries at the COP would agree to phasing out fossil fuels in one form or another. However, a handful of countries are the reason why there is no consensus.

This is no surprise. Saudi Arabia, in particular, has a long history of delaying, watering down and blocking climate negotiations. With other petrostates and many partners from the oil and gas industry, the Saudis have earned a reputation as obstructionists at the COPs. They skillfully play with the rules of the UN and use their financial and geopolitical power.

The Arab group apparently also saw its interests threatened at COP28. In a letter, OPEC warned its members to prevent all formulations describing a fossil fuel phase-out at COP28. Observers saw this as a sign of weakness on the part of the oil cartel. Others said that the Arab countries had underestimated how serious COP28 would be about a genuine fossil fuel phase-out and that many had not prepared their economies for this.

Participants also reported that the Arab group blocked the negotiations on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) for a long time. The aim was to forge an alliance between the EU and the African countries, which would then also support the fossil fuel phase-out. Saudi Arabia is not the only one: Kuwait and Iraq also joined the front line of countries warning against reducing emissions too quickly.

In fact, the climate crisis and global warming pose a particular threat to the Arab states. Studies warn that the Gulf states could become partially uninhabitable in a few decades if global warming continues. A study by the G20 also sees serious problems for Saudi Arabia, particularly if global warming increases.

Yet the 22 countries of the Arab Group, which acts and negotiates together at the COPs, are very diverse. They include rich oil states and poor countries, monarchies and democracies, countries with extremely high numbers of refugees among their populations. The group is divided into the Gulf states, the Levant countries on the Mediterranean and North Africa. Alongside international and regional heavyweights such as Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Egypt and the UAE, there are also small petrostates such as Kuwait, Qatar and Oman. Countries such as Sudan, Jordan and Palestine have little international influence, but are tied to the big players through aid or common geopolitical interests in conflicts.

The relationship between COP host UAE and its large neighbor Saudi Arabia is also special. There is constant speculation about the extent of Riyadh’s influence over the UAE and, consequently, over the COP presidency’s course. The two countries are actually political and military allies, but are also in fierce economic competition. While the UAE scores points with COP28, the billions invested in renewables and the future city of Masdar, Saudi Arabia has its “Vision 2030.”

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman wants to lead his country into the future with Vision 2030: The idea is to diversify the economy. The Kingdom wants to be climate-neutral by 2060, albeit with CCS and continued oil and gas exports. However, the think tank project Climate Action Tracker gives Saudi Arabia the worst rating of “critically inadequate” because its climate plans are considered inadequate and the technology is considered the “wrong solution.”

Some observers also wonder if Saudi Arabia wants its rival and neighbor UAE to have a successful COP at all. According to a newspaper report, the relationship between the rulers, bin Salman on the Saudi side and his former mentor Mohammed bin Sayed in the UAE, has cooled considerably in recent times – apparently over a dispute about oil production quotas at OPEC.

Click here for all previously published COP28 articles.

Mr. Steiner, at last year’s COP27, you were very concerned about the debt crisis in developing countries. Has the situation improved since then?

No, it has become even more acute compared to last year because the interest rates on the largest capital markets have actually gone up. The developing countries’ costs for their interest payments have become even higher.

What does this mean for these countries?

The governments of some countries now spend more on interest payments on foreign debt than on their own country’s education and health sectors. Important national revenues flow into debt servicing instead of there. And there is a point at which these countries can no longer obtain money on the international capital markets. And the instruments of the IMF and World Bank have not yet been changed as promised to such an extent that they could solve this problem.

Many countries are still on the brink of insolvency. How are these countries supposed to invest in climate action?

We can already see this in the fact that investments have partially declined, especially in developing countries and in many other countries. The International Energy Agency (IEA) also tells us this. It is not because countries do not need more energy infrastructure or electricity supply, but simply because no money is available. Our data shows 48 countries are just one step away from insolvency. But if they openly admit this, their loan rates will go up again. This is a massive threat to an economy and a vicious circle.

Why is there no international debate about this debt trap?

It is not an acute threat to the global financial system because these are smaller economies. But that is short-sighted. Because when countries collapse financially, this can very quickly lead to socio-political extremes or tensions. Forty percent of the world’s poorest people live in these countries. This means that we have enormous social volatility.

In other words, the debate here at COP about reforming the World Bank and other institutions bypasses these countries because they are too small?

The grand reform of the international financial architecture is still pending. And what we currently have are the emergency instruments from the pandemic to disburse more money in the short term. The only problem is that the current solution is exacerbating the problem because the mountain of debt is growing. Here at the climate conference, we are trying to convince developing countries to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy of the future. But many simply cannot afford the energy transition. Financially speaking, they don’t have the leeway to make these investments. That is why these international financial institutions are so crucial for these countries.

What would be the best outcome for these countries?

The best thing would be a decision to drive forward the global energy transition and to ensure that it is financed, especially in poor countries. We need more “concessional,” in other words, low-interest loans. We must not forget that the poor countries themselves are already making amazing investments: China, India, Brazil, but also countries such as Uruguay, Kenya and Costa Rica. What we need here are investment partnerships where we, as the international community, i.e., the rich countries, allow these countries additional investment.

Many developing countries are indebted to China. What does that mean?

A little less than a third of all international debt is owed to China as a lender. I don’t want to point fingers, but rather ask: What does that do to a group like the G77? This is why calls to reform the international financial system are growing louder and louder. The UN Secretary-General has also called for this. And it was also a clear demand at the G20 recently. The USA, long skeptical, has also joined in. This means that reforms are now being implemented. The question is always, how far do you go? How far-reaching will the reforms be?

When it comes to climate policy, developed countries often claim to be frontrunners. But you say there are also role models in emerging and developing countries. Who are you thinking of?

I can give you dozens of examples. Take Uruguay: A nation with almost 95 percent of its electricity coming from renewables. That didn’t just fall out of the sky somewhere, it is the result of a consistent energy policy over the last 15 years. Now, the Ministry of Finance has analyzed how expensive the subsidies for diesel and petrol for local public transport are. And it turns out that it is cheaper to convert the country’s entire bus fleet to electric than to continue paying fossil fuel subsidies. In other words, they are converting now.

Can you give any other examples?

Costa Rica, for example, has increased its total forest area to almost 60 percent over the last few decades through consistent nature conservation and reforestation. Kenya, the country where I lived for ten years, started using geothermal energy in the Rift Valley back in the 1970s. Today, it is the backbone of an infrastructure network that provides well over 90 percent of the electricity supply from renewables. Fortunately, the country did not listen to external consultants at the time, who had advised against it.

What can developed countries learn from this?

The most important thing is that everyone now knows what climate change is and that it is forcing us to think and plan for a low-carbon future. We need to get off the high horse of thinking that the developed countries are the ones taking action. In India alone, over 400 gigawatts of renewable energy will probably be connected to the grid in the next seven to eight years. No other country has achieved this in such a short time. It will also be interesting when a country like Namibia, with the support of the German government, starts to develop renewable energies and green hydrogen – for energy supply and development at home and the export of ‘green hydrogen’ to Germany. A whole new market for the global energy industry is emerging here.

Many countries in Africa, in particular, say that they have a right to fossil fuel development because they have contributed nothing to climate change. Do these countries have a right to fossil fuel development?

Who wants to deny them this right? With what legitimacy? You have to realize that many of those calling for restrictions belong to the largest oil and gas producers in the world themselves: the United States, Canada, Norway, Great Britain. The US produces more oil and gas than any other country. Canada has recently issued new licenses and Norway continues to expand. Our task as the United Nations Development Program is to support African countries in developing their energy sector – that means first giving them the opportunity to decide for themselves.

What does that mean specifically?

I would be surprised if an African country still opts for fossil fuels today if it receives – for example – accompanying financing from abroad for renewables. This is the only way they can ensure sustainable industrialization. Kenya’s president says something about African climate change that the world should listen to much more closely. Africa will perhaps be the first continent that will first need a green energy infrastructure to enable its industrialization.

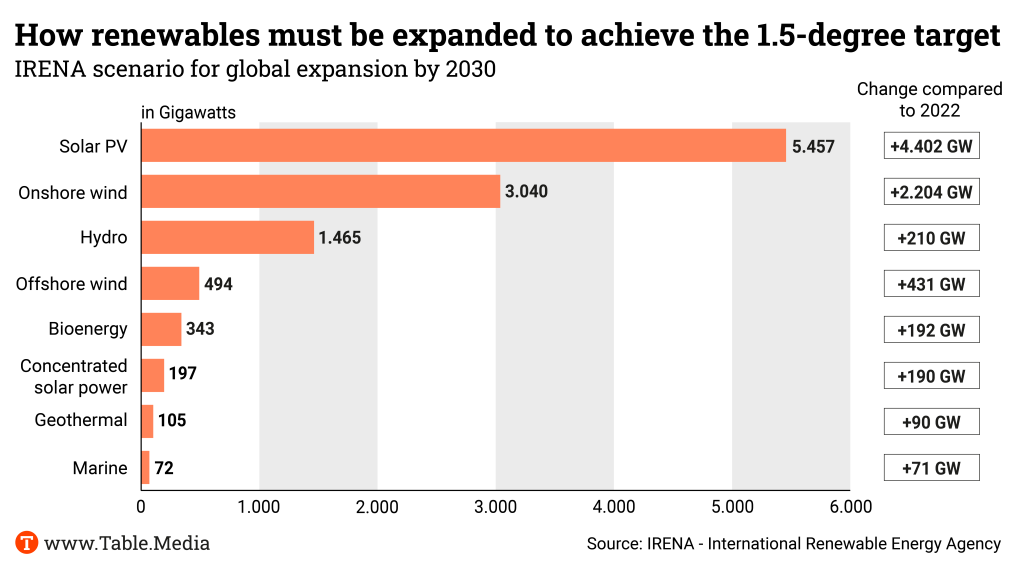

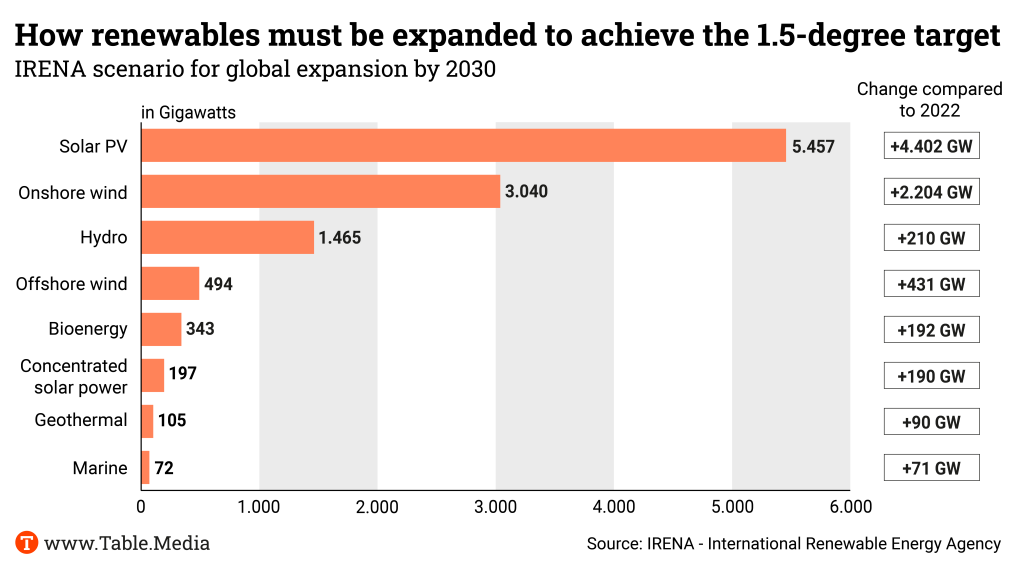

One of the most important goals of COP28 is a resolution to triple the capacity of renewable energies worldwide by 2030: From currently 3,600 gigawatts (2022), this would require increasing capacity to 11,000 GW (11 terawatts). So far, around 130 countries have signed up to the initiative to triple renewable energies and double energy efficiency.

The proposal addresses several problems at once:

According to the IEA, some 500 gigawatts of renewables will be generated in 2023, 69 percent more than last year. If this trend continues, the IEA believes a tripling is possible by 2030. If growth remains at 500 gigawatts annually, it will only double by 2030, according to analyses by energy think tank Ember.

According to IRENA, solar and wind energy will account for the largest share of the 11,000 gigawatts with almost 5,500 GW (solar) 3,000 GW (onshore wind), and just under 500 GW (offshore wind).

The implementation would require securing financing, particularly in emerging countries. A high debt burden and a sharp rise in interest rates make it difficult for many countries to raise the necessary capital for expansion. A monitoring mechanism such as annual monitoring is also needed, according to Ute Collier from IRENA and Dave Jones from Ember.

There are also technical hurdles: While the solar industry is developing quite well, the wind industry’s capacities are not yet sufficient for the target, the IEA warns. Political support is needed to expand production capacities. Approval procedures for the construction of wind power plants also need to be expedited and countries need to invest more in the expansion of power grids and a more flexible electricity system.

In addition to tripling renewables, doubling energy efficiency is also on the agenda of the COP host, the least-developed countries, the EU, the USA and many other countries. IRENA estimates that improving energy efficiency can achieve a quarter of the reduction in emissions by 2050. This could be achieved, for example, through the electrification of the transport and heating sectors as well as improved building insulation and more efficient technical systems.

The aim is to achieve an average annual efficiency improvement of four percent through 2030. This means that generating one euro of economic output would require four percent less energy each year. In 2022, the increase in efficiency was only two percent – in the five years before that, it was only one percent. With an improvement of four percent, primary energy consumption would decrease by ten percent by 2030 – with economic growth of 26 percent, as the IEA calculates.

At COP28, Norway announced it would invest 50 million US dollars in the Amazon Fund to preserve the Brazilian rainforest. This financial injection is also a recognition of Brazil’s ongoing efforts to end deforestation. In the first eleven months of President Ignacio Lula da Silva’s government, deforestation decreased by around 50 percent.

When deforestation rates skyrocketed under far-right president Jair Bolsonaro, donors froze the fund’s money. Deforestation is the largest source of greenhouse gases in Brazil.

Since Lula has been in office, around four billion Brazilian reais (around 750 million euros) have been pledged to the fund. Norway is by far the fund’s largest donor, followed by Germany. The German government already pledged 35 million euros in January. Money comes from the USA, the UK, the EU, Denmark and Switzerland, among others. The fund was set up in 2008 to mobilize additional resources for the conservation of rainforests. rtr/kul

The list of consequences of climate change felt in Senegal – and in many other African countries – is long: extreme rainfall, the destruction of sensitive ecosystems, droughts and food insecurity. The ocean is virtually devouring the Dakar Peninsula, swallowing up houses and hotels along the hundreds of kilometers of coastline.

With focus and a calm voice, 54-year-old Madeleine Diouf Sarr listed the problems in her country on the sidelines of an EU workshop on climate change and how to tackle it in 2012. Now, more than ten years later, the Senegalese woman has become a prominent figure on the climate stage.

Since January 2022 and until the end of the year, she has been the head of the Group of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and the first woman ever to hold this position. Sarr represents their interests at the COP28 international climate conference.

In Senegal, she oversees the projects under the Green Climate Fund as technical coordinator. Sarr also ensures that Senegal makes its contribution to the Paris Agreement. She now heads the Climate Change Department at the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MEDD).

Madeleine Diouf Sarr studied biology, environmental engineering and ecology at the University of Dakar, as well as in Grenoble, Nancy and Paris. She began her career at the Senegalese Ministry of the Environment. Over the years, she has worked on issues ranging from water and air pollution to coastal erosion and emissions trading.

Even though the 54-year-old has acquired the demeanor and voice of an experienced civil servant, she still fights for the concerns of the poorest countries as she did in the past. In her many public appearances, Sarr always comes across as professional and well-informed, but is otherwise very reserved.

Of the 46 least developed countries, 33 are on the African continent and nine in Asia. “We are dealing with a relentless reality: The least developed countries are home to over 14 percent of the world’s population, yet account for only one percent of emissions. Yet, we bear the greatest cost of the climate crisis. The disproportionate impact of the climate crisis on our people despite minimal responsibility is a grave injustice,” said Sarr a few weeks before COP28. As chief negotiator for the climate interests of the poorest countries, she and her fellow ministers have summarized their most important concerns in the Dakar Declaration.

At COP, Madeleine Diouf Sarr calls, above all, for a binding commitment from all countries worldwide to massively reduce carbon emissions as well as large-scale investment in renewables. “We must ensure that no one is left alone to deal with this crisis.” Sarr welcomes the Global Stocktake mechanism, as it highlights how much still needs to be done in the fight against climate change. Sarr also supports the idea of financial compensation payments – a loss and damage fund. Lucia Weiß from Dakar

Whales are not something you would expect to see in the Arabian desert – not even in a rich oil state whose fossil fuel resources make many absurdities possible. But in the middle of the COP grounds, sounds reminiscent of whale songs can actually be heard.

You know the situation: Another stressful day at the office, the computer kept crashing, important deadlines fell through, the coffee machine went on strike and your tasks were impossible to complete. Perhaps not quite as impossible as bringing about the final phase-out of all fossil fuels at a climate summit – but you can certainly think of an apt example from your own day-to-day job. But as soon as you get home after a hard day’s work and pop in a CD of your favorite whale songs, all the stress disappears, and you can devote yourself to your family duties.

The situation is very similar at this year’s COP. An open dome rises from the center of the summit area, which contains enormous loudspeakers inside. They emit gentle tunes day in and day out. Whoever falls under their spell is immediately hypnotized. Steps become slower, facial features more relaxed, and the world’s worries suddenly seem unimportant.

Rising emissions? Oil companies making obscene amounts of money and expanding their production in the middle of the climate crisis? Sinking islands? A draft COP final text that OPEC could have written? When we are close to the dome, we hardly care about such mundane matters. Instead of fretting, we smile, blissfully drifting away deep in our thoughts on the steadily rising sea level.

We ask ourselves only one thing: Why didn’t the COP presidency use such sedative sounds elsewhere long ago? Imagine oil and island states clashing during negotiations on the fossil fuel phase-out. Suddenly, a soothing tune plays, and Saudi Arabia, relaxed in the here and now and completely “unabated,” accepts the fossil fuel phase-out. Or African and developed countries are arguing about money for adaptation – and under the effect of the blissful sounds, the United States suddenly opens its pockets. (Speaking of opening pockets: We suspect this strategy could also be successfully applied elsewhere, and send our best regards to Berlin).

Our urgent appeal to the summit president: Your Excellency, remember the healing power of music! Direct the whale songs directly into the negotiating rooms and then close the doors until everyone inside is ready to make actual progress. Then perhaps this COP could bring a truly historic result for the climate after all. ae

Once again, everything came to a grinding halt shortly before the end of the conference in Dubai. We’ve seen it before: Saudi Arabia and the oil lobby regularly slow down the COP machine. On the one hand, they block ambitious formulations and targets. On the other hand, they have enforced the consensus principle, which slows down every decision. Bernhard Pötter reports on the underlying reasons.

A lot is being done in Dubai to convince developing countries to transition faster away from fossil fuels. “But many simply cannot afford the energy transition,” says Achim Steiner, head of the UN Development Program (UNDP), in today’s interview. Steiner calls for more concessionary loans – and explains what the Global North can learn from the South.

The main sticking point in the negotiations at COP28 is the energy package: Today’s background information takes another look at the goals of tripling renewable energies by 2030 and improving energy efficiency. Significant investment in power grids and far greater efforts to improve efficiency are needed to achieve this. And the wind sector would have to massively expand its production capacities.

Things are now getting exciting in Dubai. We expect a final decision to be made today, Wednesday, on if and what the outcome of COP28 will look like. We will then be back with all the interesting details for you.

The deadlock at COP28 in Dubai over a controversial final declaration on the Global Stocktake (GST) has rekindled an age-old debate in the UN climate negotiations: Why doesn’t COP vote by majority? And it draws attention to the countries of the Arab world, which are apparently among the biggest obstructionists at the conference. They are also the reason why the conferences do not make majority decisions.

Contrary to what is often believed, decisions at the COP do not have to be made unanimously – but by consensus. This means that not everyone has to agree, but no one is allowed to object openly. So much for the theory. The practice of the negotiations has shown: If it is late enough at the final plenary, if the assembly is ready for a decision and a stubborn country is not a political heavyweight, a COP president can sometimes bypass it. This is what happened to Bolivia on the last night of Cancún 2010 at COP16.

The COP does not decide by majority vote because, even after 31 years of the Framework Convention on Climate Change, it has not yet adopted any “rules and procedures” for this. Together with OPEC, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait prevented the first attempt to do so in 1995. Since then, climate conferences have made do with the lowest common denominator: the consensus principle. “Entrenching consensus was a master stroke of the fossil fuel lobby in the early days,” historian Joanna Depledge, a specialist on climate talks from Cambridge University, told the Associated Press. “By that I mean Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, backed by U.S.-based oil lobbyists. It was OPEC who insisted on consensus – and because no agreement could be reached on a voting rule, decision making is now indeed by consensus, by default.”

Attempts to change the rules also failed in 1996 and 2011. Such a democratic procedure would also not suit some big players such as the USA or China – surely a majority of countries could be found to force the USA to pay more climate aid by holding a vote, for example.

Recently, former US Vice President Al Gore and former Irish Prime Minister Mary Robinson have called for a change to majority voting. The background: Observers and delegates have reported that mainly countries of the Arab group around Saudi Arabia are resisting a resolution to end fossil fuels at COP28. It is said that around 80 to 85 percent of the countries at the COP would agree to phasing out fossil fuels in one form or another. However, a handful of countries are the reason why there is no consensus.

This is no surprise. Saudi Arabia, in particular, has a long history of delaying, watering down and blocking climate negotiations. With other petrostates and many partners from the oil and gas industry, the Saudis have earned a reputation as obstructionists at the COPs. They skillfully play with the rules of the UN and use their financial and geopolitical power.

The Arab group apparently also saw its interests threatened at COP28. In a letter, OPEC warned its members to prevent all formulations describing a fossil fuel phase-out at COP28. Observers saw this as a sign of weakness on the part of the oil cartel. Others said that the Arab countries had underestimated how serious COP28 would be about a genuine fossil fuel phase-out and that many had not prepared their economies for this.

Participants also reported that the Arab group blocked the negotiations on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) for a long time. The aim was to forge an alliance between the EU and the African countries, which would then also support the fossil fuel phase-out. Saudi Arabia is not the only one: Kuwait and Iraq also joined the front line of countries warning against reducing emissions too quickly.

In fact, the climate crisis and global warming pose a particular threat to the Arab states. Studies warn that the Gulf states could become partially uninhabitable in a few decades if global warming continues. A study by the G20 also sees serious problems for Saudi Arabia, particularly if global warming increases.

Yet the 22 countries of the Arab Group, which acts and negotiates together at the COPs, are very diverse. They include rich oil states and poor countries, monarchies and democracies, countries with extremely high numbers of refugees among their populations. The group is divided into the Gulf states, the Levant countries on the Mediterranean and North Africa. Alongside international and regional heavyweights such as Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Egypt and the UAE, there are also small petrostates such as Kuwait, Qatar and Oman. Countries such as Sudan, Jordan and Palestine have little international influence, but are tied to the big players through aid or common geopolitical interests in conflicts.

The relationship between COP host UAE and its large neighbor Saudi Arabia is also special. There is constant speculation about the extent of Riyadh’s influence over the UAE and, consequently, over the COP presidency’s course. The two countries are actually political and military allies, but are also in fierce economic competition. While the UAE scores points with COP28, the billions invested in renewables and the future city of Masdar, Saudi Arabia has its “Vision 2030.”

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman wants to lead his country into the future with Vision 2030: The idea is to diversify the economy. The Kingdom wants to be climate-neutral by 2060, albeit with CCS and continued oil and gas exports. However, the think tank project Climate Action Tracker gives Saudi Arabia the worst rating of “critically inadequate” because its climate plans are considered inadequate and the technology is considered the “wrong solution.”

Some observers also wonder if Saudi Arabia wants its rival and neighbor UAE to have a successful COP at all. According to a newspaper report, the relationship between the rulers, bin Salman on the Saudi side and his former mentor Mohammed bin Sayed in the UAE, has cooled considerably in recent times – apparently over a dispute about oil production quotas at OPEC.

Click here for all previously published COP28 articles.

Mr. Steiner, at last year’s COP27, you were very concerned about the debt crisis in developing countries. Has the situation improved since then?

No, it has become even more acute compared to last year because the interest rates on the largest capital markets have actually gone up. The developing countries’ costs for their interest payments have become even higher.

What does this mean for these countries?

The governments of some countries now spend more on interest payments on foreign debt than on their own country’s education and health sectors. Important national revenues flow into debt servicing instead of there. And there is a point at which these countries can no longer obtain money on the international capital markets. And the instruments of the IMF and World Bank have not yet been changed as promised to such an extent that they could solve this problem.

Many countries are still on the brink of insolvency. How are these countries supposed to invest in climate action?

We can already see this in the fact that investments have partially declined, especially in developing countries and in many other countries. The International Energy Agency (IEA) also tells us this. It is not because countries do not need more energy infrastructure or electricity supply, but simply because no money is available. Our data shows 48 countries are just one step away from insolvency. But if they openly admit this, their loan rates will go up again. This is a massive threat to an economy and a vicious circle.

Why is there no international debate about this debt trap?

It is not an acute threat to the global financial system because these are smaller economies. But that is short-sighted. Because when countries collapse financially, this can very quickly lead to socio-political extremes or tensions. Forty percent of the world’s poorest people live in these countries. This means that we have enormous social volatility.

In other words, the debate here at COP about reforming the World Bank and other institutions bypasses these countries because they are too small?

The grand reform of the international financial architecture is still pending. And what we currently have are the emergency instruments from the pandemic to disburse more money in the short term. The only problem is that the current solution is exacerbating the problem because the mountain of debt is growing. Here at the climate conference, we are trying to convince developing countries to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy of the future. But many simply cannot afford the energy transition. Financially speaking, they don’t have the leeway to make these investments. That is why these international financial institutions are so crucial for these countries.

What would be the best outcome for these countries?

The best thing would be a decision to drive forward the global energy transition and to ensure that it is financed, especially in poor countries. We need more “concessional,” in other words, low-interest loans. We must not forget that the poor countries themselves are already making amazing investments: China, India, Brazil, but also countries such as Uruguay, Kenya and Costa Rica. What we need here are investment partnerships where we, as the international community, i.e., the rich countries, allow these countries additional investment.

Many developing countries are indebted to China. What does that mean?

A little less than a third of all international debt is owed to China as a lender. I don’t want to point fingers, but rather ask: What does that do to a group like the G77? This is why calls to reform the international financial system are growing louder and louder. The UN Secretary-General has also called for this. And it was also a clear demand at the G20 recently. The USA, long skeptical, has also joined in. This means that reforms are now being implemented. The question is always, how far do you go? How far-reaching will the reforms be?

When it comes to climate policy, developed countries often claim to be frontrunners. But you say there are also role models in emerging and developing countries. Who are you thinking of?

I can give you dozens of examples. Take Uruguay: A nation with almost 95 percent of its electricity coming from renewables. That didn’t just fall out of the sky somewhere, it is the result of a consistent energy policy over the last 15 years. Now, the Ministry of Finance has analyzed how expensive the subsidies for diesel and petrol for local public transport are. And it turns out that it is cheaper to convert the country’s entire bus fleet to electric than to continue paying fossil fuel subsidies. In other words, they are converting now.

Can you give any other examples?

Costa Rica, for example, has increased its total forest area to almost 60 percent over the last few decades through consistent nature conservation and reforestation. Kenya, the country where I lived for ten years, started using geothermal energy in the Rift Valley back in the 1970s. Today, it is the backbone of an infrastructure network that provides well over 90 percent of the electricity supply from renewables. Fortunately, the country did not listen to external consultants at the time, who had advised against it.

What can developed countries learn from this?

The most important thing is that everyone now knows what climate change is and that it is forcing us to think and plan for a low-carbon future. We need to get off the high horse of thinking that the developed countries are the ones taking action. In India alone, over 400 gigawatts of renewable energy will probably be connected to the grid in the next seven to eight years. No other country has achieved this in such a short time. It will also be interesting when a country like Namibia, with the support of the German government, starts to develop renewable energies and green hydrogen – for energy supply and development at home and the export of ‘green hydrogen’ to Germany. A whole new market for the global energy industry is emerging here.

Many countries in Africa, in particular, say that they have a right to fossil fuel development because they have contributed nothing to climate change. Do these countries have a right to fossil fuel development?

Who wants to deny them this right? With what legitimacy? You have to realize that many of those calling for restrictions belong to the largest oil and gas producers in the world themselves: the United States, Canada, Norway, Great Britain. The US produces more oil and gas than any other country. Canada has recently issued new licenses and Norway continues to expand. Our task as the United Nations Development Program is to support African countries in developing their energy sector – that means first giving them the opportunity to decide for themselves.

What does that mean specifically?

I would be surprised if an African country still opts for fossil fuels today if it receives – for example – accompanying financing from abroad for renewables. This is the only way they can ensure sustainable industrialization. Kenya’s president says something about African climate change that the world should listen to much more closely. Africa will perhaps be the first continent that will first need a green energy infrastructure to enable its industrialization.

One of the most important goals of COP28 is a resolution to triple the capacity of renewable energies worldwide by 2030: From currently 3,600 gigawatts (2022), this would require increasing capacity to 11,000 GW (11 terawatts). So far, around 130 countries have signed up to the initiative to triple renewable energies and double energy efficiency.

The proposal addresses several problems at once:

According to the IEA, some 500 gigawatts of renewables will be generated in 2023, 69 percent more than last year. If this trend continues, the IEA believes a tripling is possible by 2030. If growth remains at 500 gigawatts annually, it will only double by 2030, according to analyses by energy think tank Ember.

According to IRENA, solar and wind energy will account for the largest share of the 11,000 gigawatts with almost 5,500 GW (solar) 3,000 GW (onshore wind), and just under 500 GW (offshore wind).

The implementation would require securing financing, particularly in emerging countries. A high debt burden and a sharp rise in interest rates make it difficult for many countries to raise the necessary capital for expansion. A monitoring mechanism such as annual monitoring is also needed, according to Ute Collier from IRENA and Dave Jones from Ember.

There are also technical hurdles: While the solar industry is developing quite well, the wind industry’s capacities are not yet sufficient for the target, the IEA warns. Political support is needed to expand production capacities. Approval procedures for the construction of wind power plants also need to be expedited and countries need to invest more in the expansion of power grids and a more flexible electricity system.

In addition to tripling renewables, doubling energy efficiency is also on the agenda of the COP host, the least-developed countries, the EU, the USA and many other countries. IRENA estimates that improving energy efficiency can achieve a quarter of the reduction in emissions by 2050. This could be achieved, for example, through the electrification of the transport and heating sectors as well as improved building insulation and more efficient technical systems.

The aim is to achieve an average annual efficiency improvement of four percent through 2030. This means that generating one euro of economic output would require four percent less energy each year. In 2022, the increase in efficiency was only two percent – in the five years before that, it was only one percent. With an improvement of four percent, primary energy consumption would decrease by ten percent by 2030 – with economic growth of 26 percent, as the IEA calculates.

At COP28, Norway announced it would invest 50 million US dollars in the Amazon Fund to preserve the Brazilian rainforest. This financial injection is also a recognition of Brazil’s ongoing efforts to end deforestation. In the first eleven months of President Ignacio Lula da Silva’s government, deforestation decreased by around 50 percent.

When deforestation rates skyrocketed under far-right president Jair Bolsonaro, donors froze the fund’s money. Deforestation is the largest source of greenhouse gases in Brazil.

Since Lula has been in office, around four billion Brazilian reais (around 750 million euros) have been pledged to the fund. Norway is by far the fund’s largest donor, followed by Germany. The German government already pledged 35 million euros in January. Money comes from the USA, the UK, the EU, Denmark and Switzerland, among others. The fund was set up in 2008 to mobilize additional resources for the conservation of rainforests. rtr/kul

The list of consequences of climate change felt in Senegal – and in many other African countries – is long: extreme rainfall, the destruction of sensitive ecosystems, droughts and food insecurity. The ocean is virtually devouring the Dakar Peninsula, swallowing up houses and hotels along the hundreds of kilometers of coastline.

With focus and a calm voice, 54-year-old Madeleine Diouf Sarr listed the problems in her country on the sidelines of an EU workshop on climate change and how to tackle it in 2012. Now, more than ten years later, the Senegalese woman has become a prominent figure on the climate stage.

Since January 2022 and until the end of the year, she has been the head of the Group of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and the first woman ever to hold this position. Sarr represents their interests at the COP28 international climate conference.

In Senegal, she oversees the projects under the Green Climate Fund as technical coordinator. Sarr also ensures that Senegal makes its contribution to the Paris Agreement. She now heads the Climate Change Department at the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MEDD).

Madeleine Diouf Sarr studied biology, environmental engineering and ecology at the University of Dakar, as well as in Grenoble, Nancy and Paris. She began her career at the Senegalese Ministry of the Environment. Over the years, she has worked on issues ranging from water and air pollution to coastal erosion and emissions trading.

Even though the 54-year-old has acquired the demeanor and voice of an experienced civil servant, she still fights for the concerns of the poorest countries as she did in the past. In her many public appearances, Sarr always comes across as professional and well-informed, but is otherwise very reserved.

Of the 46 least developed countries, 33 are on the African continent and nine in Asia. “We are dealing with a relentless reality: The least developed countries are home to over 14 percent of the world’s population, yet account for only one percent of emissions. Yet, we bear the greatest cost of the climate crisis. The disproportionate impact of the climate crisis on our people despite minimal responsibility is a grave injustice,” said Sarr a few weeks before COP28. As chief negotiator for the climate interests of the poorest countries, she and her fellow ministers have summarized their most important concerns in the Dakar Declaration.

At COP, Madeleine Diouf Sarr calls, above all, for a binding commitment from all countries worldwide to massively reduce carbon emissions as well as large-scale investment in renewables. “We must ensure that no one is left alone to deal with this crisis.” Sarr welcomes the Global Stocktake mechanism, as it highlights how much still needs to be done in the fight against climate change. Sarr also supports the idea of financial compensation payments – a loss and damage fund. Lucia Weiß from Dakar

Whales are not something you would expect to see in the Arabian desert – not even in a rich oil state whose fossil fuel resources make many absurdities possible. But in the middle of the COP grounds, sounds reminiscent of whale songs can actually be heard.

You know the situation: Another stressful day at the office, the computer kept crashing, important deadlines fell through, the coffee machine went on strike and your tasks were impossible to complete. Perhaps not quite as impossible as bringing about the final phase-out of all fossil fuels at a climate summit – but you can certainly think of an apt example from your own day-to-day job. But as soon as you get home after a hard day’s work and pop in a CD of your favorite whale songs, all the stress disappears, and you can devote yourself to your family duties.

The situation is very similar at this year’s COP. An open dome rises from the center of the summit area, which contains enormous loudspeakers inside. They emit gentle tunes day in and day out. Whoever falls under their spell is immediately hypnotized. Steps become slower, facial features more relaxed, and the world’s worries suddenly seem unimportant.

Rising emissions? Oil companies making obscene amounts of money and expanding their production in the middle of the climate crisis? Sinking islands? A draft COP final text that OPEC could have written? When we are close to the dome, we hardly care about such mundane matters. Instead of fretting, we smile, blissfully drifting away deep in our thoughts on the steadily rising sea level.

We ask ourselves only one thing: Why didn’t the COP presidency use such sedative sounds elsewhere long ago? Imagine oil and island states clashing during negotiations on the fossil fuel phase-out. Suddenly, a soothing tune plays, and Saudi Arabia, relaxed in the here and now and completely “unabated,” accepts the fossil fuel phase-out. Or African and developed countries are arguing about money for adaptation – and under the effect of the blissful sounds, the United States suddenly opens its pockets. (Speaking of opening pockets: We suspect this strategy could also be successfully applied elsewhere, and send our best regards to Berlin).

Our urgent appeal to the summit president: Your Excellency, remember the healing power of music! Direct the whale songs directly into the negotiating rooms and then close the doors until everyone inside is ready to make actual progress. Then perhaps this COP could bring a truly historic result for the climate after all. ae