COP28 is over – and as soon as the gavel dropped, there was discussion about whether the COP had achieved a “historic result” and heralded the “end of the fossil fuel era” – or it only achieved “the bare minimum.” Lukas Scheid took a close look at the final text and categorizes the most important results.

Because – spoiler – climate resolutions passed by UN bodies are sometimes both historic and insufficient, even more so in this case: It really does herald the end of fossil fuels – but only if the majority believe in it, analyzes Bernhard Pötter. He asked around in the corridors of COP to find out how this result came about and explains how a weak agreement on paper is supposed to become strong in reality.

The COP was actually supposed to deliver progress in climate adaptation. But the results are sobering, writes Alexandra Endres. The demands of the most vulnerable African countries were barely heard. There were agreements on some definitions, but important questions on financing and tangible goals were postponed later.

We have also collected reactions from climate science, think tanks, NGOs and international organizations.

After two weeks of the COP marathon, it’s now time for the Climate.Table “phase down.” We’ll be back on Thursday before Christmas with the last issue for this year.

The first Global Stocktake – an evaluation of progress towards the goals of the Paris Agreement – has been adopted. Progress has been made in mitigating climate change, adapting to changing climatic conditions and the means available to realize the Paris goals. However, the 21-page document, which all 197 signatory states have agreed to, states that we are not yet on the right path to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

In Dubai, countries have now committed to accelerating action “on the basis of the best available science” before the end of the decade. What these measures will look like was the most disputed issue at COP28 until the very end, particularly when it came to the role of fossil fuels: the “UAE Consensus,” as COP President Sultan Al Jaber dubbed the paper, envisages the following:

This is the first time that fossil fuels as a whole have been included in the final text of a UN climate conference, even if it is not the phase-out of fossil fuels that the EU had called for. The opposition from some Arab countries led by Saudi Arabia was too strong, and reaching an agreement on a hard fossil fuel phase-out was not possible in Dubai. After weeks of discussions, the term “phase-out” was already politically burnt out. And so, an alternative was needed that Saudi Arabia could also agree to in order to save face.

Many consider the now agreed “transition away from fossil fuels” nearly equivalent to a phase-out. Moreover, there is no restriction on the transition, for example, by adding the controversial term “unabated fossil fuels,” which is often used as a synonym for fossil fuels without CCS. Li Shuo, climate expert at the Asia Society Policy Institute think tank, believes that the signal the Dubai agreement sends is, in any case, more important than the exact semantic differentiation of terms.

EU Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra considers the resolution in Dubai to be “the beginning of a phase out.” Christoph Bals, Political Director of Germanwatch, also believes that the agreed wording clearly sets out the global goal: A future free of fossil fuels.

What is particularly important here is the context in which the transition away from fossil fuels has been embedded in paragraph 28d. Firstly, there is the chapeau – the introductory sentence of the paragraph. In it, the countries recognize that greenhouse gases must be reduced as quickly as possible to not exceed 1.5 degrees of global warming. This highlights the need for short-term measures to reduce emissions: Expanding renewables and increasing energy efficiency.

Although the signatory states also agreed to promote CCS and nuclear power, measures are to be taken to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels in this “critical decade.” Both CCS and nuclear energy are not expected to be sufficiently available in this decade to reduce emissions in the energy sector significantly. This means that the short-term goals of the Global Stocktake can only be achieved by drastically reducing the consumption and production of fossil fuels while simultaneously ramping up renewables.

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock emphasized at the conclusion of COP28: “Anyone who can do the maths knows that investments in fossil fuels are not profitable in the long term.” While renewables played no role in the main text of COP21 in Paris in 2015, the world has now decided.

But Dubai failed to repeat a Paris moment. The joy is clouded by the fact that “transition fuels” will continue to play a role in the energy transition. In other words, gas. However, Alden Meyer, Senior Associate and climate policy expert at think tank E3G, emphasizes that gas is not a bridging technology, but a fossil fuel. He was, therefore, not entirely satisfied with the text.

In the closing plenary of the COP, Samoa criticized on behalf of the group of island states that there was only talk of an end to “inefficient” subsidies for fossil fuels, with the term “inefficient” not being defined in this context. The Samoan delegate also criticized that the call to reach the global emissions peak by 2025 at the latest was not included in the text.

But above all, the question of how developing countries will be supported in the energy transition remains unanswered in Dubai. The text also does not specify any obligations for developed nations or richer countries to decarbonize faster than others. While COP may have reached an agreement on the fossil fuel phase-out, it does not provide a plan to fund it, commented Mohamed Adow from Power Shift Africa. “If rich countries truly want to see a fossil fuel phase out they need to find creative ways to actually fund it.” Developing countries will not be able to manage the phase-out, Adow said.

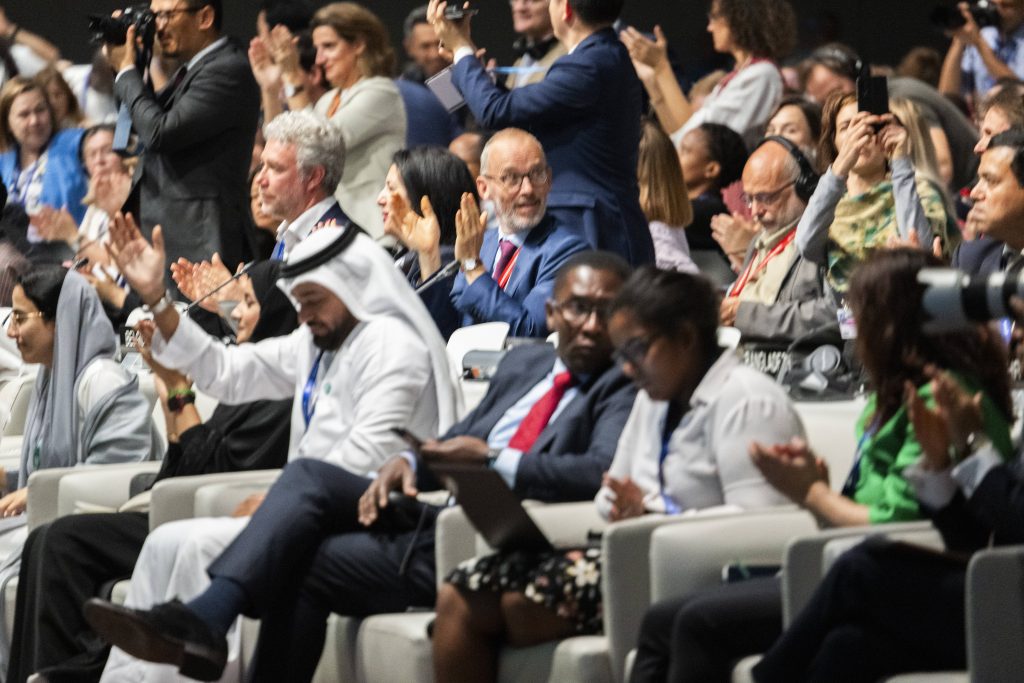

At 11.09 on Wednesday morning, COP28 President Sultan Al Jaber opened the pivotal session of the Dubai Climate Change Conference. In the Al Hairat plenary, he presented his proposal for the main final document on the Global Stocktake (GST) to the overtired delegates of COP28. Just as Laurent Fabius, then President of the 2015 Paris Agreement, did, Al Jaber briefly looked around the room, said: “Hearing no objection, it is so decided” – and banged his gavel down. The hall rose to cheers and a standing ovation. The long-disputed agreement, the “UAE Consensus,” had been accepted.

At 11:12 a.m., after this surprise coup, Al Jaber began his speech. He praised the agreement he had negotiated as a “historic achievement” and a “basis for transformative change” that would move “the world in the right direction.” This marked the start of the second and much longer process that will shape the world of climate diplomacy over the coming years: Trying to talk political and economic strength into a weak international agreement.

After all, it takes a lot of effort to actually recognize what many people wish to see in the document: The phase-out of fossil fuels; the chance to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, effective help for adapting to change and compensation for climate damage, a fairer distribution of money, technology and life prospects.

Practically all speakers present made this effort to take a consistently positive view. In his final appearance on the big stage, US climate envoy John Kerry spoke of a “clear, unambiguous message” that fossil fuels are not the future. German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock celebrated a “day of great joy” that seals the end of the fossil fuel era.

Coal exporter Australia praised the text, Zambia said the agreement breathed “climate love,” Switzerland liked it, India supported it, and China spoke of a “global irreversible trend towards a green and low-carbon future.” Once Saudi Arabia congratulated the UAE and praised that harmful emissions were now really being tackled, namely with CO2 storage, it was finally clear that the Dubai declaration was supposed to go down in history as a great consensus and success.

The few who did not join the cheers came too late: The island nations only asked to speak after the gavel had fallen. They had missed the start of the meeting, which was pushed back, due to their own internal meeting. Samoa, chair of the island nations, then also explained the problems the vulnerable islands have with the formulations that will reduce CO2 emissions too little and too slowly – because their survival is already endangered. This did not dampen the good mood: The island states also gave a standing ovation.

The “UAE Consensus” is also a document that promises a lot without specifying much. It thus joins the ranks of all climate agreements since Paris: No binding rules. It is, instead, setting framework conditions, formulating goals, declaring intentions – and relying on new technologies, market forces, people’s protests and the insight of politicians and businesses to find the right course.

The Global Stocktake in Dubai has shown that past progress has been too slow, but the direction is partly right. Now, the new national climate plans (NDCs), due in two years, are expected to take up these ideas. After all, global carbon emissions must be practically halved in just seven years if the 1.5-degree target is still to be achieved. And to accomplish this in the NDCs, it is vital that as many countries as possible agree that this is the right path to take. Germany, for instance, has announced that it will continue to support emerging economies in the energy transition, for example, through Just Energy Transition Partnerships.

How can the 1.5-degree target be maintained? Contrary to what many claim, the Dubai document does not explicitly state that, based on scientific data, countries must phase out fossil fuels (see details here). Instead, it calls on countries to “contribute” to meeting the 1.5 degree target by, for example, tripling renewables, doubling efficiency and “transitioning away from fossil fuels in the energy system.” This strengthens all those who want to transition away from fossil fuels, is intended to show financial investors that risks are involved, and does not tell petrostates how long they can continue selling oil or when they have to switch to renewables. There is general enthusiasm for the resolution because it does not lay down any general rules.

The agreement is a huge success for the strategic interests of the COP host. They managed to bring a difficult conference to a successful conclusion and proved their worth as mediators between the Global North and South. The Emirates around Al Jaber had been working towards this for a long time, investing a lot of money and effort in this conference. The technical organization of the largest climate conference of all time with 100,000 visitors was excellent, Al Jaber and his team did a lot of things right. At least until the penultimate day, when they presented a text that was so unambitious that it left the conference puzzled:

The hectic last day of the conference did not yield any answers.

Unlike many other COP decisions, the Dubai deal did not come from any of the big climate policy powers. On the contrary, apart from their Sunnylands Agreement in the fall and an announcement of new long-term climate strategies, the United States and China kept a noticeably low profile. India made virtually no appearance; Brazil exerted hardly any influence. South Africa at least came up with the decisive term “transition away,” which brought about the breakthrough in fossil fuels.

But the agreement itself was driven by the EU and its allies with the island nations, Latin American countries such as Colombia and Chile and the most vulnerable on one side – and the oil states around Saudi Arabia on the other.

The agreement partly enshrines for the future what will happen anyway: Investments clearly show a departure from fossil fuels, with emissions peaking in the next few years. However, this shift away from fossil fuels is happening far too slowly, as Alden Meyer from the environmental organization E3G, an experienced COP observer, says: “This will accelerate what is happening. It will push fossil fuels out of the system.” But it’s up to the countries at home to decide how quickly.

The UAE Consensus also confirms something else, as many speakers pointed out at the conclusion: It proves that the multilateral UN system can achieve viable results despite exhausting debates and major conflicts of interest. Even if they constitute the “lowest common denominator,” as Meyer said. And it is also important to remember that the will to cooperate is crucial.

Adaptation to climate change only received its due political attention in Dubai towards the end of COP28. After the long blockade of the negotiating track, partly by the Arab countries, parties had very little time to work on the content of the text.

The summit’s final declaration on the framework for the Global Adaptation Goal (GGA) is correspondingly incomplete. In particular:

In this context, Maheen Shan, an adaptation expert at the environmental organization WWF, highlights the precarious financial situation of many countries. “Many developing countries are over-indebted. How can they reach their adaptation goals without sufficient funds? And without clear sub-targets, how can they measure progress and achieve the overarching goal?”

The adaptation text is “very weak,” said Shan. However, she welcomed the fact that nature was strongly represented in the document. Previous versions had placed less emphasis on the role of the environment for adaptation. “This is a start. Now, we need to build on it together.”

For a long time, it was uncertain whether an agreement could be reached at all, as some developing countries maintained the position that clear targets and sufficient financial and other support for adaptation were non-negotiable from their perspective. They refused a weak result for the adaptation target. Speaking for the African negotiating group shortly before the end of the summit, Zambia’s Environment Minister Collins Nzovu reiterated this.

The minister had called for:

One of the most important tasks at COP28 was to adopt such a framework, which, after two years of preparatory work, was supposed to concretize the global adaptation goal enshrined in Article 7 of the Paris Agreement and make it feasible. However, the preparatory working group only achieved results late, and then certain countries stalled the negotiations in Dubai.

In the end, the African developing countries still accepted the weak final documents on adaptation. The text on the GGA framework and the declaration on the Global Stocktake (GST) were adopted without objection in the final plenary session on Wednesday morning.

Nzovu even spoke of the “climate love” he felt in Dubai. At the same time, he made it clear that the African countries expect additional work on the GGA, which would guarantee the measurable sub-goals “that we are longing for.” Sierra Leone chose clearer words for the least developed countries: The current GGA, devoid of implementable commitments, is “not the ambition we had expected” and advocated for adaptation.” This was “just the start of a conversation on the GGA framework.”

Both documents, the GGA framework and the GST text, now set out seven areas in which adaptation is to be advanced “by 2030, and progressively beyond“:

The texts leave room for adding additional adaptation areas in the future.

In addition, it stipulates that by 2030, all countries must have:

By 2027, all countries are expected to possess early warning systems.

The development of concrete, measurable indicators will be postponed into the future. To this end, the COP will adopt a two-year work program. Parties and observers can submit submissions by March 2024, which the UNFCCC Secretariat will then summarize by May 2024. Further deliberations are to begin at the upcoming interim summit in Bonn in June 2024.

The goal is to draft recommendations that are to be discussed and adopted at the latest at COP30 in Belém, Brazil. For indicators, this is “far too little,” commented Rixa Schwarz, Co-Head of International Climate Policy at the NGO Germanwatch.

The documents only include rather vague formulations on funding. At least the text on the Global Stocktake refers to the figures from UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report – they had temporarily disappeared from the summit texts. Accordingly, the developing countries’ need for adaptation financing in 2030 will be between 215 and 387 billion US dollars. Therefore, COP recognizes that a lot of money will be needed to prepare particularly vulnerable countries and regions against the effects of climate change. However, it does not make concrete commitments or proposals about how the money could be raised.

Furthermore, the summit reiterates previous commitments, such as the promise by established developed countries to double their adaptation financing between 2019 and 2025. However, Germanwatch expert Schwarz criticized the lack of a clear pathway as to how this might happen.

Everything else relating to adaptation financing will be postponed until next year. A new climate finance goal, the “New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG),” is to be adopted at COP29. However, according to Schwarz, the link between the NCQG and adaptation financing is “too weak” in the COP28 documents. Yet this is “an extremely important point, that funding flows so that adaptation measures can be implemented.”

At the beginning of the conference, there was much talk in Dubai that lost trust had been regained through the swift adoption of the loss and damage fund. In the coming year, the aim will be to show particularly vulnerable countries that their positions are also reflected in the COP29 outcomes on adaptation.

International reactions to the final document of COP28 are mixed. Both OPEC and its opponent, the International Energy Agency (IEA), are pleased with the outcome. NGOs and think tanks speak in part of a “strong signal” but also complain about “loopholes” for fossil fuels. Climate scientists criticize that, although the results of the conference are important steps, they do not go far enough.

Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency (IEA), called the COP resolutions a “major outcome that clearly states the goal of transitioning away from fossil fuels in line with 1.5C.” However, “countries must act quickly on these ambitions with concrete policies.” Birol’s statements are very diplomatic. Just a few days ago, the IEA calculated that the COP pledges on tripling renewables, doubling energy efficiency and reducing methane emissions would not reduce global greenhouse gas emissions quickly enough overall.

OPEC and the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GEFC) congratulated the COP presidency for a “consensual and positive outcome.” The oil and gas industry wants to contribute to a “just, orderly and inclusive energy transition” – in particular by improving efficiency and developing and deploying advanced technologies such as carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS),” said Haitham Al Ghais and Mohamed Hamel, the Secretaries General of OPEC and GEFC. Further investments in oil and gas are necessary to meet future demand and “ensure global market stability.” Shortly before the conclusion of COP, OPEC had called on its members to block all formulations relating to fossil fuels in the summit’s final document.

Climate scientist Niklas Höhne, co-founder of the New Climate Institute, says: The conference is “a small step forward,” but “not the big step” that would have been necessary in view of the obvious climate crisis. Transitioning from fossil fuels is not the “necessary emergency brake.” The result is “not historic, only the bare minimum.” Only when countries translate the resolutions into national policies can it be decided whether the conference was a success.

According to Wolfgang Obergassel from the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy, the COP process needs to be viewed realistically. Too many countries are still pursuing fossil interests. Against this backdrop, “the past three climate summits have brought enormous progress,” namely putting fossil fuels “finally” on the agenda. Obergassel warns: “The more than 120 countries that have spoken out in favor of a clear decision to phase out the use of fossil fuels should follow up their words with action.”

Wilfried Rickels says that “by raising the NDCs – as called for in the resolutions – it is still possible to meet the 2-degree target“. According to the head of the Global Commons and Climate Policy Research Center at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, it is still too early to assess whether the 1.5-degree target is still achievable.

Christoph Bals, Policy Director of Germanwatch, says that the “climate conference sends a strong signal to the world.” The “transition away from coal, oil and gas” called for at a COP for the first time is an “important step.” However, accepting gas as a bridging technology could “open up large loopholes.”

Ani Dasgupta, President and CEO of the US-based World Resources Institute, described the final document as a “historic outcome” that “marks the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era.” However, he warned that technologies for capturing greenhouse gases (CCS) “should not be used as an excuse to slow the transition to renewables.”

Bill Hare from Climate Analytics also found many positive words: “The move away from fossil fuels is explicitly stated in a COP outcome – a first nail in the coffin for the fossil fuel industry.” However, the results in the energy sector are “weak.” He cited the lack of a commitment to reach the emissions peak by 2025, which is considered necessary to keep the 1.5-degree target within reach. Hare calls on governments to show more commitment: It is now up to them to “make their NDCs stronger than this agreement.”

Lavetanalagi Seru, Regional Coordinator of the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, criticized the COP outcome, saying it “falls short of climate justice and equity for our frontline communities” of the climate crisis. “This outcome continues to allow for dangerous distractions and loopholes, such as carbon capture, nuclear, and removal technologies.”

The final structure of global emissions trading under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement remains uncertain even after COP28. It had already become apparent that the negotiations in Dubai would fail, as the USA and the EU could not agree on how countries could trade carbon credits with each other.

Discussions on which standards and transparency rules apply to carbon reduction projects and the registration of credits (Article 6.2) will continue in the coming months. However, Gilles Dufrasne, Policy at Carbon Market Watch, sees this as more of a gain for the instrument’s integrity: “Trading carbon credits requires strong environmental and human rights guardrails.” The text on the table was unable to provide this. “It would have risked reproducing the mistakes of voluntary carbon markets, and by rejecting it, negotiators made the best out of a bad situation,” says Dufrasne.

Europe demands strict certification rules and wants business information of parties trading credits to be kept confidential only in exceptional cases. Other countries, including the United States, want to leave it up to companies to decide which information they disclose.

Environmentalists consider Article 6.2 to be about preventing greenwashing. A non-transparent certificate trading system, in which many credits are traded but hardly any real emissions are saved, could render the market a useless instrument for climate change. An integrated system with strict environmental standards and consequences for non-compliance, on the other hand, could help to accelerate the decarbonization of the private sector and make carbon reduction financially lucrative. luk

COP28 is over – and as soon as the gavel dropped, there was discussion about whether the COP had achieved a “historic result” and heralded the “end of the fossil fuel era” – or it only achieved “the bare minimum.” Lukas Scheid took a close look at the final text and categorizes the most important results.

Because – spoiler – climate resolutions passed by UN bodies are sometimes both historic and insufficient, even more so in this case: It really does herald the end of fossil fuels – but only if the majority believe in it, analyzes Bernhard Pötter. He asked around in the corridors of COP to find out how this result came about and explains how a weak agreement on paper is supposed to become strong in reality.

The COP was actually supposed to deliver progress in climate adaptation. But the results are sobering, writes Alexandra Endres. The demands of the most vulnerable African countries were barely heard. There were agreements on some definitions, but important questions on financing and tangible goals were postponed later.

We have also collected reactions from climate science, think tanks, NGOs and international organizations.

After two weeks of the COP marathon, it’s now time for the Climate.Table “phase down.” We’ll be back on Thursday before Christmas with the last issue for this year.

The first Global Stocktake – an evaluation of progress towards the goals of the Paris Agreement – has been adopted. Progress has been made in mitigating climate change, adapting to changing climatic conditions and the means available to realize the Paris goals. However, the 21-page document, which all 197 signatory states have agreed to, states that we are not yet on the right path to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

In Dubai, countries have now committed to accelerating action “on the basis of the best available science” before the end of the decade. What these measures will look like was the most disputed issue at COP28 until the very end, particularly when it came to the role of fossil fuels: the “UAE Consensus,” as COP President Sultan Al Jaber dubbed the paper, envisages the following:

This is the first time that fossil fuels as a whole have been included in the final text of a UN climate conference, even if it is not the phase-out of fossil fuels that the EU had called for. The opposition from some Arab countries led by Saudi Arabia was too strong, and reaching an agreement on a hard fossil fuel phase-out was not possible in Dubai. After weeks of discussions, the term “phase-out” was already politically burnt out. And so, an alternative was needed that Saudi Arabia could also agree to in order to save face.

Many consider the now agreed “transition away from fossil fuels” nearly equivalent to a phase-out. Moreover, there is no restriction on the transition, for example, by adding the controversial term “unabated fossil fuels,” which is often used as a synonym for fossil fuels without CCS. Li Shuo, climate expert at the Asia Society Policy Institute think tank, believes that the signal the Dubai agreement sends is, in any case, more important than the exact semantic differentiation of terms.

EU Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra considers the resolution in Dubai to be “the beginning of a phase out.” Christoph Bals, Political Director of Germanwatch, also believes that the agreed wording clearly sets out the global goal: A future free of fossil fuels.

What is particularly important here is the context in which the transition away from fossil fuels has been embedded in paragraph 28d. Firstly, there is the chapeau – the introductory sentence of the paragraph. In it, the countries recognize that greenhouse gases must be reduced as quickly as possible to not exceed 1.5 degrees of global warming. This highlights the need for short-term measures to reduce emissions: Expanding renewables and increasing energy efficiency.

Although the signatory states also agreed to promote CCS and nuclear power, measures are to be taken to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels in this “critical decade.” Both CCS and nuclear energy are not expected to be sufficiently available in this decade to reduce emissions in the energy sector significantly. This means that the short-term goals of the Global Stocktake can only be achieved by drastically reducing the consumption and production of fossil fuels while simultaneously ramping up renewables.

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock emphasized at the conclusion of COP28: “Anyone who can do the maths knows that investments in fossil fuels are not profitable in the long term.” While renewables played no role in the main text of COP21 in Paris in 2015, the world has now decided.

But Dubai failed to repeat a Paris moment. The joy is clouded by the fact that “transition fuels” will continue to play a role in the energy transition. In other words, gas. However, Alden Meyer, Senior Associate and climate policy expert at think tank E3G, emphasizes that gas is not a bridging technology, but a fossil fuel. He was, therefore, not entirely satisfied with the text.

In the closing plenary of the COP, Samoa criticized on behalf of the group of island states that there was only talk of an end to “inefficient” subsidies for fossil fuels, with the term “inefficient” not being defined in this context. The Samoan delegate also criticized that the call to reach the global emissions peak by 2025 at the latest was not included in the text.

But above all, the question of how developing countries will be supported in the energy transition remains unanswered in Dubai. The text also does not specify any obligations for developed nations or richer countries to decarbonize faster than others. While COP may have reached an agreement on the fossil fuel phase-out, it does not provide a plan to fund it, commented Mohamed Adow from Power Shift Africa. “If rich countries truly want to see a fossil fuel phase out they need to find creative ways to actually fund it.” Developing countries will not be able to manage the phase-out, Adow said.

At 11.09 on Wednesday morning, COP28 President Sultan Al Jaber opened the pivotal session of the Dubai Climate Change Conference. In the Al Hairat plenary, he presented his proposal for the main final document on the Global Stocktake (GST) to the overtired delegates of COP28. Just as Laurent Fabius, then President of the 2015 Paris Agreement, did, Al Jaber briefly looked around the room, said: “Hearing no objection, it is so decided” – and banged his gavel down. The hall rose to cheers and a standing ovation. The long-disputed agreement, the “UAE Consensus,” had been accepted.

At 11:12 a.m., after this surprise coup, Al Jaber began his speech. He praised the agreement he had negotiated as a “historic achievement” and a “basis for transformative change” that would move “the world in the right direction.” This marked the start of the second and much longer process that will shape the world of climate diplomacy over the coming years: Trying to talk political and economic strength into a weak international agreement.

After all, it takes a lot of effort to actually recognize what many people wish to see in the document: The phase-out of fossil fuels; the chance to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, effective help for adapting to change and compensation for climate damage, a fairer distribution of money, technology and life prospects.

Practically all speakers present made this effort to take a consistently positive view. In his final appearance on the big stage, US climate envoy John Kerry spoke of a “clear, unambiguous message” that fossil fuels are not the future. German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock celebrated a “day of great joy” that seals the end of the fossil fuel era.

Coal exporter Australia praised the text, Zambia said the agreement breathed “climate love,” Switzerland liked it, India supported it, and China spoke of a “global irreversible trend towards a green and low-carbon future.” Once Saudi Arabia congratulated the UAE and praised that harmful emissions were now really being tackled, namely with CO2 storage, it was finally clear that the Dubai declaration was supposed to go down in history as a great consensus and success.

The few who did not join the cheers came too late: The island nations only asked to speak after the gavel had fallen. They had missed the start of the meeting, which was pushed back, due to their own internal meeting. Samoa, chair of the island nations, then also explained the problems the vulnerable islands have with the formulations that will reduce CO2 emissions too little and too slowly – because their survival is already endangered. This did not dampen the good mood: The island states also gave a standing ovation.

The “UAE Consensus” is also a document that promises a lot without specifying much. It thus joins the ranks of all climate agreements since Paris: No binding rules. It is, instead, setting framework conditions, formulating goals, declaring intentions – and relying on new technologies, market forces, people’s protests and the insight of politicians and businesses to find the right course.

The Global Stocktake in Dubai has shown that past progress has been too slow, but the direction is partly right. Now, the new national climate plans (NDCs), due in two years, are expected to take up these ideas. After all, global carbon emissions must be practically halved in just seven years if the 1.5-degree target is still to be achieved. And to accomplish this in the NDCs, it is vital that as many countries as possible agree that this is the right path to take. Germany, for instance, has announced that it will continue to support emerging economies in the energy transition, for example, through Just Energy Transition Partnerships.

How can the 1.5-degree target be maintained? Contrary to what many claim, the Dubai document does not explicitly state that, based on scientific data, countries must phase out fossil fuels (see details here). Instead, it calls on countries to “contribute” to meeting the 1.5 degree target by, for example, tripling renewables, doubling efficiency and “transitioning away from fossil fuels in the energy system.” This strengthens all those who want to transition away from fossil fuels, is intended to show financial investors that risks are involved, and does not tell petrostates how long they can continue selling oil or when they have to switch to renewables. There is general enthusiasm for the resolution because it does not lay down any general rules.

The agreement is a huge success for the strategic interests of the COP host. They managed to bring a difficult conference to a successful conclusion and proved their worth as mediators between the Global North and South. The Emirates around Al Jaber had been working towards this for a long time, investing a lot of money and effort in this conference. The technical organization of the largest climate conference of all time with 100,000 visitors was excellent, Al Jaber and his team did a lot of things right. At least until the penultimate day, when they presented a text that was so unambitious that it left the conference puzzled:

The hectic last day of the conference did not yield any answers.

Unlike many other COP decisions, the Dubai deal did not come from any of the big climate policy powers. On the contrary, apart from their Sunnylands Agreement in the fall and an announcement of new long-term climate strategies, the United States and China kept a noticeably low profile. India made virtually no appearance; Brazil exerted hardly any influence. South Africa at least came up with the decisive term “transition away,” which brought about the breakthrough in fossil fuels.

But the agreement itself was driven by the EU and its allies with the island nations, Latin American countries such as Colombia and Chile and the most vulnerable on one side – and the oil states around Saudi Arabia on the other.

The agreement partly enshrines for the future what will happen anyway: Investments clearly show a departure from fossil fuels, with emissions peaking in the next few years. However, this shift away from fossil fuels is happening far too slowly, as Alden Meyer from the environmental organization E3G, an experienced COP observer, says: “This will accelerate what is happening. It will push fossil fuels out of the system.” But it’s up to the countries at home to decide how quickly.

The UAE Consensus also confirms something else, as many speakers pointed out at the conclusion: It proves that the multilateral UN system can achieve viable results despite exhausting debates and major conflicts of interest. Even if they constitute the “lowest common denominator,” as Meyer said. And it is also important to remember that the will to cooperate is crucial.

Adaptation to climate change only received its due political attention in Dubai towards the end of COP28. After the long blockade of the negotiating track, partly by the Arab countries, parties had very little time to work on the content of the text.

The summit’s final declaration on the framework for the Global Adaptation Goal (GGA) is correspondingly incomplete. In particular:

In this context, Maheen Shan, an adaptation expert at the environmental organization WWF, highlights the precarious financial situation of many countries. “Many developing countries are over-indebted. How can they reach their adaptation goals without sufficient funds? And without clear sub-targets, how can they measure progress and achieve the overarching goal?”

The adaptation text is “very weak,” said Shan. However, she welcomed the fact that nature was strongly represented in the document. Previous versions had placed less emphasis on the role of the environment for adaptation. “This is a start. Now, we need to build on it together.”

For a long time, it was uncertain whether an agreement could be reached at all, as some developing countries maintained the position that clear targets and sufficient financial and other support for adaptation were non-negotiable from their perspective. They refused a weak result for the adaptation target. Speaking for the African negotiating group shortly before the end of the summit, Zambia’s Environment Minister Collins Nzovu reiterated this.

The minister had called for:

One of the most important tasks at COP28 was to adopt such a framework, which, after two years of preparatory work, was supposed to concretize the global adaptation goal enshrined in Article 7 of the Paris Agreement and make it feasible. However, the preparatory working group only achieved results late, and then certain countries stalled the negotiations in Dubai.

In the end, the African developing countries still accepted the weak final documents on adaptation. The text on the GGA framework and the declaration on the Global Stocktake (GST) were adopted without objection in the final plenary session on Wednesday morning.

Nzovu even spoke of the “climate love” he felt in Dubai. At the same time, he made it clear that the African countries expect additional work on the GGA, which would guarantee the measurable sub-goals “that we are longing for.” Sierra Leone chose clearer words for the least developed countries: The current GGA, devoid of implementable commitments, is “not the ambition we had expected” and advocated for adaptation.” This was “just the start of a conversation on the GGA framework.”

Both documents, the GGA framework and the GST text, now set out seven areas in which adaptation is to be advanced “by 2030, and progressively beyond“:

The texts leave room for adding additional adaptation areas in the future.

In addition, it stipulates that by 2030, all countries must have:

By 2027, all countries are expected to possess early warning systems.

The development of concrete, measurable indicators will be postponed into the future. To this end, the COP will adopt a two-year work program. Parties and observers can submit submissions by March 2024, which the UNFCCC Secretariat will then summarize by May 2024. Further deliberations are to begin at the upcoming interim summit in Bonn in June 2024.

The goal is to draft recommendations that are to be discussed and adopted at the latest at COP30 in Belém, Brazil. For indicators, this is “far too little,” commented Rixa Schwarz, Co-Head of International Climate Policy at the NGO Germanwatch.

The documents only include rather vague formulations on funding. At least the text on the Global Stocktake refers to the figures from UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report – they had temporarily disappeared from the summit texts. Accordingly, the developing countries’ need for adaptation financing in 2030 will be between 215 and 387 billion US dollars. Therefore, COP recognizes that a lot of money will be needed to prepare particularly vulnerable countries and regions against the effects of climate change. However, it does not make concrete commitments or proposals about how the money could be raised.

Furthermore, the summit reiterates previous commitments, such as the promise by established developed countries to double their adaptation financing between 2019 and 2025. However, Germanwatch expert Schwarz criticized the lack of a clear pathway as to how this might happen.

Everything else relating to adaptation financing will be postponed until next year. A new climate finance goal, the “New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG),” is to be adopted at COP29. However, according to Schwarz, the link between the NCQG and adaptation financing is “too weak” in the COP28 documents. Yet this is “an extremely important point, that funding flows so that adaptation measures can be implemented.”

At the beginning of the conference, there was much talk in Dubai that lost trust had been regained through the swift adoption of the loss and damage fund. In the coming year, the aim will be to show particularly vulnerable countries that their positions are also reflected in the COP29 outcomes on adaptation.

International reactions to the final document of COP28 are mixed. Both OPEC and its opponent, the International Energy Agency (IEA), are pleased with the outcome. NGOs and think tanks speak in part of a “strong signal” but also complain about “loopholes” for fossil fuels. Climate scientists criticize that, although the results of the conference are important steps, they do not go far enough.

Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency (IEA), called the COP resolutions a “major outcome that clearly states the goal of transitioning away from fossil fuels in line with 1.5C.” However, “countries must act quickly on these ambitions with concrete policies.” Birol’s statements are very diplomatic. Just a few days ago, the IEA calculated that the COP pledges on tripling renewables, doubling energy efficiency and reducing methane emissions would not reduce global greenhouse gas emissions quickly enough overall.

OPEC and the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GEFC) congratulated the COP presidency for a “consensual and positive outcome.” The oil and gas industry wants to contribute to a “just, orderly and inclusive energy transition” – in particular by improving efficiency and developing and deploying advanced technologies such as carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS),” said Haitham Al Ghais and Mohamed Hamel, the Secretaries General of OPEC and GEFC. Further investments in oil and gas are necessary to meet future demand and “ensure global market stability.” Shortly before the conclusion of COP, OPEC had called on its members to block all formulations relating to fossil fuels in the summit’s final document.

Climate scientist Niklas Höhne, co-founder of the New Climate Institute, says: The conference is “a small step forward,” but “not the big step” that would have been necessary in view of the obvious climate crisis. Transitioning from fossil fuels is not the “necessary emergency brake.” The result is “not historic, only the bare minimum.” Only when countries translate the resolutions into national policies can it be decided whether the conference was a success.

According to Wolfgang Obergassel from the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy, the COP process needs to be viewed realistically. Too many countries are still pursuing fossil interests. Against this backdrop, “the past three climate summits have brought enormous progress,” namely putting fossil fuels “finally” on the agenda. Obergassel warns: “The more than 120 countries that have spoken out in favor of a clear decision to phase out the use of fossil fuels should follow up their words with action.”

Wilfried Rickels says that “by raising the NDCs – as called for in the resolutions – it is still possible to meet the 2-degree target“. According to the head of the Global Commons and Climate Policy Research Center at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, it is still too early to assess whether the 1.5-degree target is still achievable.

Christoph Bals, Policy Director of Germanwatch, says that the “climate conference sends a strong signal to the world.” The “transition away from coal, oil and gas” called for at a COP for the first time is an “important step.” However, accepting gas as a bridging technology could “open up large loopholes.”

Ani Dasgupta, President and CEO of the US-based World Resources Institute, described the final document as a “historic outcome” that “marks the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era.” However, he warned that technologies for capturing greenhouse gases (CCS) “should not be used as an excuse to slow the transition to renewables.”

Bill Hare from Climate Analytics also found many positive words: “The move away from fossil fuels is explicitly stated in a COP outcome – a first nail in the coffin for the fossil fuel industry.” However, the results in the energy sector are “weak.” He cited the lack of a commitment to reach the emissions peak by 2025, which is considered necessary to keep the 1.5-degree target within reach. Hare calls on governments to show more commitment: It is now up to them to “make their NDCs stronger than this agreement.”

Lavetanalagi Seru, Regional Coordinator of the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, criticized the COP outcome, saying it “falls short of climate justice and equity for our frontline communities” of the climate crisis. “This outcome continues to allow for dangerous distractions and loopholes, such as carbon capture, nuclear, and removal technologies.”

The final structure of global emissions trading under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement remains uncertain even after COP28. It had already become apparent that the negotiations in Dubai would fail, as the USA and the EU could not agree on how countries could trade carbon credits with each other.

Discussions on which standards and transparency rules apply to carbon reduction projects and the registration of credits (Article 6.2) will continue in the coming months. However, Gilles Dufrasne, Policy at Carbon Market Watch, sees this as more of a gain for the instrument’s integrity: “Trading carbon credits requires strong environmental and human rights guardrails.” The text on the table was unable to provide this. “It would have risked reproducing the mistakes of voluntary carbon markets, and by rejecting it, negotiators made the best out of a bad situation,” says Dufrasne.

Europe demands strict certification rules and wants business information of parties trading credits to be kept confidential only in exceptional cases. Other countries, including the United States, want to leave it up to companies to decide which information they disclose.

Environmentalists consider Article 6.2 to be about preventing greenwashing. A non-transparent certificate trading system, in which many credits are traded but hardly any real emissions are saved, could render the market a useless instrument for climate change. An integrated system with strict environmental standards and consequences for non-compliance, on the other hand, could help to accelerate the decarbonization of the private sector and make carbon reduction financially lucrative. luk