After a day of rest, COP28 entered its second half yesterday. And it promises to be challenging: Bernhard Pötter explains the current state of negotiations and why the topic of adaptation is becoming a major point of contention.

There have been heated debates for a long time about the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – CBAM for short. China, India and other countries feel disadvantaged by the carbon border mechanism and fear for their exports. Lukas Scheid explains the legitimate concerns and the strategy to extract concessions from the EU.

Today at COP28, the focus is on “nature, land use and oceans“. In a background piece, we contextualize nature-based solutions and biodiversity in the context of climate action. Additionally, we take a look at the Climate Change Performance Index and highlight the biggest surprises in this year’s assessment of the climate policies of 63 countries. Unfortunately, there isn’t much positive news in this area.

We will continue to keep you updated on developments at COP28.

Serious negotiations have begun at COP28 with the arrival of ministers and the release of the new draft text for the final declaration at the beginning of the second week-and they are immediately threatened by a blockade on a side track. In the negotiations on the “Global Goal on Adaptation” (GGA) to climate change, according to negotiators and observers, it is doubtful whether there will be any result.

According to some negotiators, the delaying tactics of the Arab group in closed negotiations are to blame. However, Mohamed Adow of the NGO Power Shift Africa claims, “the US and other industrialized countries are the biggest blockers. They need to stop playing with the lives of some of the most vulnerable people.”

This dispute and a meager result in adaptation could complicate decisions on the central point – the fossil exit in the GST final document. Negotiators report that the adaptation issue, particularly important to the African group, has become an important side issue: European countries, for example, are trying to make offers to African countries on this topic. The hope is that by doing so, they can create a positive atmosphere for African countries to be more open in demanding a serious fossil exit in GST negotiations.

But these offers are not currently being negotiated, according to negotiators’ complaints. Delegates attribute this to delaying tactics, particularly evident in Wednesday’s talks: Many countries from the Arab group, such as Kuwait, spoke up, countries that rarely speak otherwise. Many expressed doubts about the negotiating text. Real text work did not happen, according to reports.

After a week of standstill, there is no or only a very general text for the adaptation goal. However, time is running out because COP28 is supposed to decide on the structure of the GGA, which is scheduled for decision at COP29. These points need to be clarified:

The tactical calculation behind the blockade, as delegates suspect: If the GGA fails, the failure will be blamed on industrialized countries. This is also because, in the financing strand, they have been very restrained in replenishing the UN Adaptation Fund: of the 300 million dollars needed by the end of the year, only about 133 million dollars has been raised so far. However, if the GGA negotiations fail, it will also be the end of an alliance of African countries and friends of a serious fossil exit.

The new text for the GST declaration is far from reaching an agreement. Instead of reducing options and making it clearer for ministers, the text has been expanded to 27 pages. The especially controversial section on fossil exit has become longer and more extensive. Now, there are a total of eight different versions of the exit, along with specific formulations for ending coal, fossil subsidies, and an expansion target in the EV sector.

Formulations for direct exit range from very ambitious versions (“phase-out based on the best scientific knowledge, IPCC 1.5-degree pathways, and the principles of the Paris Agreement”) to practically purely technological proposals (expanding low CO2 footprint technologies and CCS expansion by 2030).

COP President Al Jaber has now named the Sherpa pairs, who will assist him in negotiations on specific topics. These are the respective ministers, traditionally paired industrialized/developing countries:

In the GST round, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock will negotiate for the EU, it was announced on Friday. Baerbock arrived in Dubai yesterday and stated that she expects “heated arguments” in the debates on the fossil exit, but “it must be an exit from fossil fuels, not just emissions“. This positions her against the COP presidency’s line. Concentrating only on renewables and efficiency will not lead the conference to a 1.5-degree path.

On Friday, negotiators received support for an ambitious exit from business, politics, civil society, and science. An open letter with 800 signatories, including Richard Branson, Christiana Figueres, and Vanessa Nakate, called on Al Jaber to achieve a negotiating result for the GST that must be a historic legacy of COP28. This includes:

In numerous stages, panels and press briefings in Dubai, Europe faces criticism for its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – especially from the so-called BASIC countries (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China). The CBAM allegedly contradicts the principles of the Paris Climate Agreement of “equality and common but differentiated responsibilities”. In other words, the main contributors to climate change – the industrialized nations – should not shift their responsibility to act onto weaker developing countries, even though all must work together to curb global warming.

The EU defends itself, considering the COP the wrong forum to discuss trade policy and reaffirms that the CBAM has been strictly designed according to WTO criteria. From EU sources, there is suspicion that the BASIC accusations hide a negotiation strategy. It is not clear what the BASIC countries want in return. Still, they may be seeking an excuse not to work on effective carbon pricing. EU negotiators also state that the issue does not come up in the negotiation rooms but is limited to public statements by BASIC government representatives.

The CBAM was introduced to prevent European producers, who will have to pay the European CO2 price in the future, from being disadvantaged on the international market. To avoid carbon leakage, imports of cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers and electricity from outside the EU will be subject to a carbon tariff equal to the EU CO2 price from 2026. Unless foreign producers also pay a carbon surcharge in their own country. For the EU, the CBAM is also a means of incentivizing carbon pricing in other EU countries.

The BASIC countries see CBAM as “sanctions on low-carbon products” restricting technological investments and green trade. A corresponding proposal is included in the latest draft of the most important document of COP28 – the global stocktake- on the insistence of these countries. Although the criticism is not directed only at the EU CBAM but also at the EU Deforestation Law and the US Inflation Reduction Act, the central accusation against Europe is that CBAM prevents particularly developing countries from implementing decarbonization measures for their industries. This is because export products become more expensive due to the carbon surcharge, violating WTO rules and the Paris Climate Agreement, as foreign producers are disadvantaged in the EU market.

The accusation of violating WTO rules is not new. It arose while EU lawmakers were still negotiating the exact design of CBAM. Therefore, various countries and parliamentary groups within the EU insisted on a legal text along the WTO rules of treating foreign and domestic products equally and treating all trading partners equally. The result: All importers into the EU internal market must pay the same fee for the direct greenhouse gas emissions of their products, as European producers do.

While CBAM does create a level playing field, according to Linda Kalcher, founder of the Brussels-based think tank Strategic Perspectives, “not everyone can play equally”. Countries in the Global South understandably fear that CBAM will block their access to the EU internal market. For example, many African countries do not have the same financial means to decarbonize at the same pace as European producers, says Kalcher.

Another problem, according to Kalcher, is that the revenue from CBAM goes into the EU budget. Although there is a reference in the legal text that the EU should continue to provide funds for climate adaptation and emissions reduction in the least developed countries (LDCs) – also through CBAM funds – there is no obligation, let alone a defined share for this purpose. Whether the criticism of the BASIC countries was just a tactical maneuver or they actually demand constructive talks will be seen throughout the week, believes Kalcher.

Dutch Social Democrat Mohammed Chahim, CBAM rapporteur for the European Parliament, considers most of the criticism a misunderstanding. Even in Commission circles, there is little openness to criticism, as it involves working with false claims. Between 2026 and 2040, China is expected to export around 869 million tons of CBAM-liable goods to the EU, according to forecasts by S&P Global Commodity Insights. According to S&P, this would correspond to over 201 million tons of embedded CO2 emissions (CO2 equivalents) credited under CBAM.

Since only direct emissions – those from the production process itself – are covered by CBAM, the instrument’s impact on export prices is significantly lower than claimed by BASIC countries. Indirect emissions – those from electricity generation for the production process – are only affected by CBAM in limited cases.

Sven Harmeling, Coordinator for International Climate Policy at the aid organization CARE, considers the BASIC countries’ move a “call for attention”, not having the impact to significantly influence negotiations. However, he also points out that the EU has not explained how CBAM works well and offered little help to fulfill CBAM criteria.

EU Parliamentarian Chahim can understand why countries are concerned about the impact on their industries. Therefore, he is willing to discuss these concerns with everyone and is ready to adapt the law if necessary, he said in an interview with Table.Media.

Regenerative agriculture, re-wetting of moors or large-scale afforestation – all these fall under the category of “Nature-Based Solutions” (NBS). The idea is to use nature to advance climate solutions and build resilience. Many approaches also focus on how ecosystem services can be financially compensated, known as Payments for Ecosystem Services. The concept of NBS has been around for a while, but it gained prominence in climate negotiations since COP26 in Glasgow.

Ideally, such nature-based approaches combine various benefits, so they have ecological or social advantages in addition to climate protection. This could include linking poverty reduction and climate protection or mitigating the impacts of climate change by sequestering carbon, with simultaneous benefits for biodiversity conservation. Biodiversity conservation also poses significant challenges: Last year, at the Biodiversity COP15, countries agreed to protect 30 percent of the land and sea area by 2030. To achieve this, climate protection must be considered together with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Loss of biodiversity and the collapse of ecosystems worsen the impacts of the climate crisis and make adaptation and resilience more challenging. At the same time, the topic also offers opportunities: Nature-based approaches could save up to ten gigatons of CO2 per year. That’s about a quarter of current emissions and could slow global warming by 0.3 degrees. The issue is closely related to forest protection, for which we have also published another background.

Incorporating nature-based solutions and biodiversity conservation into the UNFCCC climate action process is not easy. This is partly because it is challenging to define clear categories and indicators for it. Nature or water and species protection are difficult to quantify. However, it is quite certain that biodiversity conservation also requires additional billions. The concept is challenging to grasp because it encompasses so many different ideas. NBS are considered particularly cost-effective because they combine various benefits.

An example of how nature-based solutions have already been integrated on a large scale is the REDD+ mechanism (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) from Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. This rewards developing countries for preserving forests instead of deforestation. The efficiency of the mechanism is controversial. Carbon markets and the trade of CO2 certificates are also part of NBS.

For years, it has been criticized that “nature-based” is not precisely defined enough. It is also criticized that the term is often equated with the compensation of CO2, which could make misleading promises. In addition, it allows for a lot of greenwashing. Some critics also express that nature-based solutions are based on the approach of giving nature an economic value.

Nature-based solutions and biodiversity are not discussed separately at COP but emerge as cross-cutting themes in other areas, such as food systems and agriculture. Possible outcomes include commitments to financing and demands for better support in maintaining ecosystems, especially in the Global South.

Dec. 9; 9 a.m, Al Waha Theatre

Event From Agreement to Action: Harnessing 30X30 to Tackle Climate Change

The event will address the intersection between climate change and biodiversity loss. It will discuss how to achieve the goal of providing 200 billion US dollars annually for the conservation of biodiversity by 2030. Info

Dec. 9; 11.30 a.m., SE Room 4

Side event The 2023 IMO GHG Strategy: defining the global level-playing-field for shipping decarbonization

At the side event, the International Maritime Organization and the International Renewable Energy Agency, among others, will discuss how shipping can be decarbonized. Info

Dec. 9; 2:30 p.m., Knowledge Stage

Panel discussion Forging a Sustainable Future for Oceans

The event will discuss how climate finance can be mobilized to protect the oceans. Nature-based solutions for the oceans will also be discussed. Info

Dec. 9; 3:30 p.m., European Pavilion

Panel discussion The role of Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms in promoting carbon pricing initiatives worldwide

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is designed to prevent the production of energy-intensive goods from being relocated to countries with lower environmental standards. At this event, experts from different regions will discuss how it affects carbon markets around the world. Info

Dec. 9; 4:30 p.m., Deutscher Pavilion

Discussion Nature-based Solutions meet Circular Economy: cascading use of biomass

At the event, Environment Minister Steffi Lemke and Agriculture Minister Cem Özdemir will talk about the intersection between nature-based solutions and the circular economy. Info

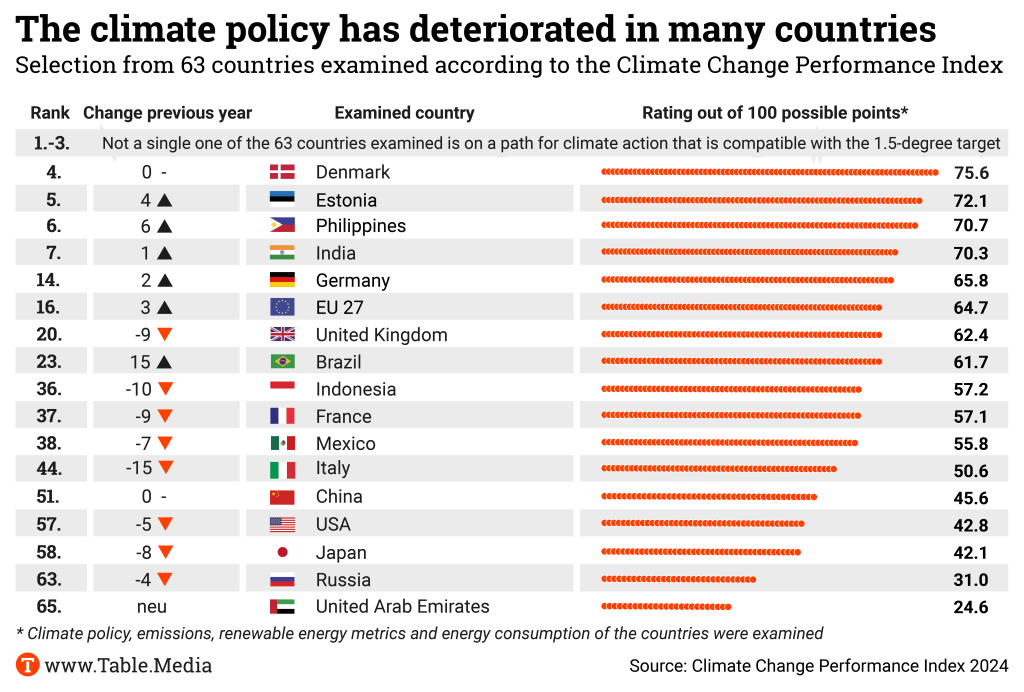

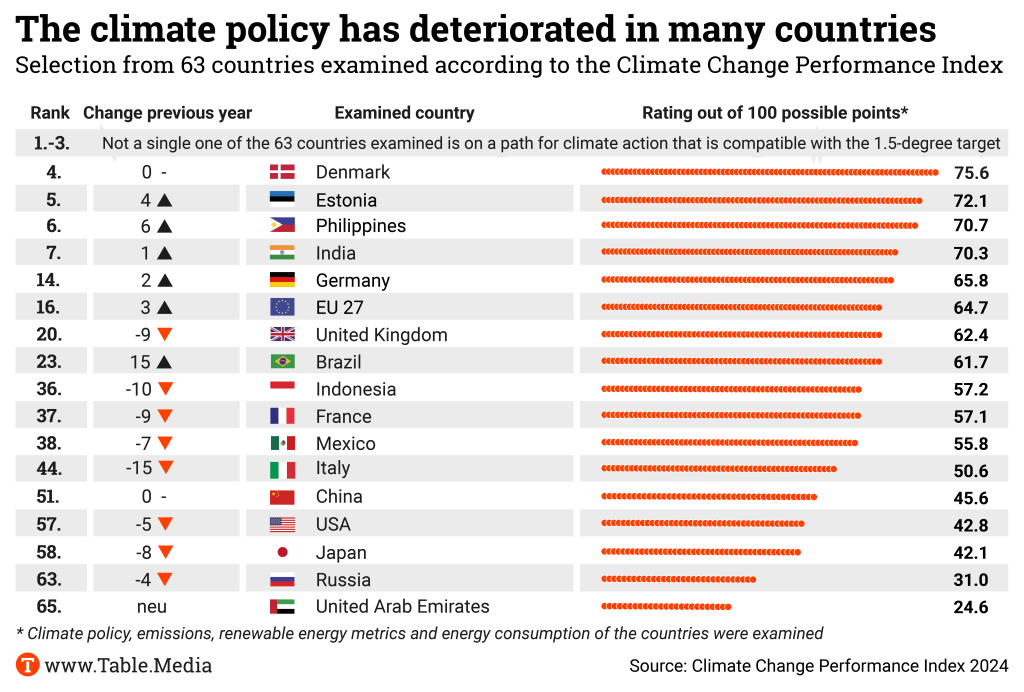

Climate policies have deteriorated in many countries, and the world is making little progress toward the Paris Climate Agreement goals. This is the conclusion of the new “Climate Change Performance Index 2024” by Germanwatch and the New Climate Institute. None of the 63 countries examined is on a path compatible with the 1.5-degree target. In the climate policy sub-rating, not a single country scores “good” for the first time. The index assessed the climate policy, emissions, renewable energy metrics, and energy consumption of the countries.

“We must now switch to emergency mode,” urged Niklas Höhne, climate researcher and co-founder of the New Climate Institute. Germany’s good ranking is due to the even worse performance of many other countries. Measured against the Paris Climate Agreement goals, Germany performs mediocre in all four categories. The government needs to do more in transport policy and the building sector. The faster expansion of renewable energy is positively evaluated.

The United States, China and the COP host, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), perform very poorly. In the United States and the UAE, per capita emissions are well above the global average. China has also exceeded the average. Positive aspects include US investments in economic restructuring (Inflation Reduction Act) and the expansion of renewables in China. In the UAE, renewable energy accounts for less than one percent of the energy mix, but new capacities are expected to come online soon.

One of the biggest climbers in this year’s ranking is Brazil. The new climate policy under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, with plans to halt deforestation, has a positive impact. However, the country is expanding coal, oil and gas production. One of the biggest losers is the United Kingdom. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak wants to increase oil production and even build a new coal mine. The country is now weak in the expansion of renewables.

India surprises with a positive performance. The country has very low per capita emissions. However, the rise in emissions could cause India to fall in future rankings. nib

Azerbaijan is set to host COP29 next year, following an agreement with competitor Armenia. The host for the next climate conference was uncertain for some time. Russia had declared it would veto any application from an EU country. The EU imposed sanctions on Moscow for its invasion of Ukraine.

Azerbaijan confirmed late on Thursday that it had reached an agreement with Armenia, allowing Baku to apply to host the COP29 talks without the risk of an Armenian veto. Armenia has agreed to support Azerbaijan’s bid to host COP29 and, in return, will receive membership in the COP Bureau of the Eastern European Group.

Some delegates at COP28 have expressed concerns about holding global climate negotiations in an oil-producing country for the second time in a row. Azerbaijan is an oil and gas producer and a member of OPEC+. “Despite Azerbaijan being rich in oil and gas, Azerbaijan’s strategic goals include diversification of energy and resources, particularly in the field of wind and solar energy,” said a spokesperson for the Azerbaijani Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Reuters. nib/rtr

Canada aims to reduce emissions from the oil and gas sector by 35 to 38 percent by 2030 compared to the 2019 reference level through a cap-and-trade system. The draft plan, presented at COP, outlines that companies exceeding emission limits can purchase offset certificates in the future. The emissions trading is expected to commence no earlier than 2026.

Under the new emissions trading system, Canada sets a cap not on production but on emissions from the oil and gas sector. The cap is intended to be gradually lowered over the years. The trading system would encompass all greenhouse gases and apply to oil and gas producers, offshore facilities, and LNG producers, covering approximately 85 percent of sector emissions.

Environmental organizations had advocated for an emission cap of 110 megatons by the end of the decade. According to current plans, the cap is likely to range between 106 and 112 megatons. Additionally, the oil and gas industry could emit an extra 25 megatons, offset through the purchase of offset certificates or contributions to a decarbonization fund.

While environmental groups welcome the plan, they emphasize the need for a substantial reduction in the cap post-2030. Representatives from Greenpeace Canada state that the draft contains “weak targets and loopholes“. NGOs also criticize that the trading system is likely to come into effect too late to achieve Canada’s national climate goals (NDCs). kul

Amid record heatwaves, intensifying and costly extreme weather events, and increasingly dire warnings that climate change is literally killing us, calls to abandon fossil fuels grow louder. But the fossil-fuel industry is doubling down with investments in new oil and gas projects and major corporate mergers, walking back climate pledges, and making false promises that they can keep pumping without polluting. We need to ditch fossil fuels. But how?

The answer is unlikely to emerge from this year’s petrostate-hosted United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai, which could deliver a political commitment to phase out fossil fuels but won’t chart the pathway to a fossil-free future. To address what UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called “the poisoned root of the climate crisis,” we must look beyond the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to forge new forums fit for this purpose.

The good news is that Guterres, the pope, numerous national governments, and bodies like the International Energy Agency have joined the growing global call for a phaseout of coal, oil, and gas. At the UN Climate Ambition Summit in September, governments acknowledged that the climate crisis is a fossil-fuel crisis. The question is not whether to move beyond oil and gas, but how.

The bad news is that the fossil-fuel industry, buoyed by record-breaking profits in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, seems impervious to such pressure. Worse, these colossal profits are being reinvested in more oil and gas development. As climate disasters intensify before our eyes, the industry responsible for nearly 90% of carbon dioxide emissions is betting that its dirty products will be a mainstay of the global economy for decades to come.

To force a change, we must expose the economic fragility that fossil-fuel dependence creates and its broader toll on human rights. Reliance on oil, gas, and coal makes communities more vulnerable to supply disruptions, affecting everything from heating and transportation to food prices. Such disruptions fall hardest on the most impoverished populations while boosting the industry’s profits.

It is worth recalling that fossil-fuel companies underperformed the market for the ten years preceding the war in Ukraine. That decade of decline reflected long-term energy-transition trends that the recent uptick in earnings has not changed. With fossil-fuel demand projected to peak globally by 2030, oil and gas remain a bad bet.

Part of the problem is that governments have responded to price volatility by increasing fossil-fuel subsidies, rather than imposing windfall taxes. They also have continued to approve new oil and gas projects, including offshore in protected ocean areas. Planned production is double what’s compatible with the target of limiting global warming to 1.5° Celsius above pre-industrial levels; there is simply no room for new oil and gas supply if the world is to avoid climate catastrophe.

Fossil fuels appear competitive with ever-cheaper renewables only because their production has been subsidized and their producers insulated from the costs associated with the damage they cause. The industry’s negative externalities, long borne by frontline communities, are now being imposed on people around the world in the form of wildfires, hurricanes, floods, and droughts. If we compelled fossil-fuel companies to shoulder the losses they long saw coming, and redirected public funds to renewable solutions, oil and gas assets would be exposed as the liabilities they are.

This points to another big problem: corporate capture. Although climate litigation is key to holding the industry accountable, the challenge is not just to make polluters pay for the harms they cause. We also must diminish their outsize influence on climate policy. Despite the best efforts of movements like Kick Big Polluters Out, the fossil-fuel industry not only has a seat at this year’s climate talks; it is at the head of the table.

There sits Sultan Al Jaber, the CEO of the United Arab Emirates’ national oil company, which is currently pursuing its own expansion plans. Al Jaber, COP28 president, is intent on portraying the fossil-fuel industry as the hero, not the villain, in the fight against climate change. Yet this is a well-known survival strategy for an industry in long-term decline. So, too, is the UAE’s advocacy of an “all of the above” approach that promotes renewables as a complement to fossil fuels, rather than a replacement for them, and that champions carbon capture and offsets, despite abundant evidence that neither leads to significant emissions reductions.

Contrary to what Al Jaber suggested earlier this year, the problem is not just with fossil-fuel emissions; it is with fossil fuels themselves. Focusing only on carbon ignores all the other negative effects of fossil fuels, including their impact on health, such as the eight million premature deaths from air pollution annually.

Though fossil fuels are overwhelmingly to blame for climate change, our UNFCCC-led climate regime has failed to address them, even before the industry was handed the gavel. For decades, the international body that should be leading the fossil-fuel phaseout has conspicuously avoided the issue. Neither the 1992 UN Climate Convention nor the 2015 Paris climate agreement mentions oil, gas, or coal.

This omission was not some casual oversight. It is a symptom of a deeper crisis in global climate governance. Because UNFCCC decisions require a consensus among 198 members, powerful countries can block progress and assure lowest-common-denominator outcomes, or none at all.

COP28 further underscores the need for alternative processes to manage the decline of fossil fuels, free from the influence of those who profit from them. Every day provides new reminders of why we need to phase out oil, gas, and coal. Fortunately, initiatives like the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, and the Global Parliamentarians’ Inquiry offer new ideas about how to do it. Governments must commit to a forum dedicated to fossil-fuel phaseout so the real work of ending the fossil-fuel era can begin.

Nikki Reisch is Director of the Climate and Energy Program at the Center for International Environmental Law.

In cooperation with Project Syndicate, 2023.

After a day of rest, COP28 entered its second half yesterday. And it promises to be challenging: Bernhard Pötter explains the current state of negotiations and why the topic of adaptation is becoming a major point of contention.

There have been heated debates for a long time about the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – CBAM for short. China, India and other countries feel disadvantaged by the carbon border mechanism and fear for their exports. Lukas Scheid explains the legitimate concerns and the strategy to extract concessions from the EU.

Today at COP28, the focus is on “nature, land use and oceans“. In a background piece, we contextualize nature-based solutions and biodiversity in the context of climate action. Additionally, we take a look at the Climate Change Performance Index and highlight the biggest surprises in this year’s assessment of the climate policies of 63 countries. Unfortunately, there isn’t much positive news in this area.

We will continue to keep you updated on developments at COP28.

Serious negotiations have begun at COP28 with the arrival of ministers and the release of the new draft text for the final declaration at the beginning of the second week-and they are immediately threatened by a blockade on a side track. In the negotiations on the “Global Goal on Adaptation” (GGA) to climate change, according to negotiators and observers, it is doubtful whether there will be any result.

According to some negotiators, the delaying tactics of the Arab group in closed negotiations are to blame. However, Mohamed Adow of the NGO Power Shift Africa claims, “the US and other industrialized countries are the biggest blockers. They need to stop playing with the lives of some of the most vulnerable people.”

This dispute and a meager result in adaptation could complicate decisions on the central point – the fossil exit in the GST final document. Negotiators report that the adaptation issue, particularly important to the African group, has become an important side issue: European countries, for example, are trying to make offers to African countries on this topic. The hope is that by doing so, they can create a positive atmosphere for African countries to be more open in demanding a serious fossil exit in GST negotiations.

But these offers are not currently being negotiated, according to negotiators’ complaints. Delegates attribute this to delaying tactics, particularly evident in Wednesday’s talks: Many countries from the Arab group, such as Kuwait, spoke up, countries that rarely speak otherwise. Many expressed doubts about the negotiating text. Real text work did not happen, according to reports.

After a week of standstill, there is no or only a very general text for the adaptation goal. However, time is running out because COP28 is supposed to decide on the structure of the GGA, which is scheduled for decision at COP29. These points need to be clarified:

The tactical calculation behind the blockade, as delegates suspect: If the GGA fails, the failure will be blamed on industrialized countries. This is also because, in the financing strand, they have been very restrained in replenishing the UN Adaptation Fund: of the 300 million dollars needed by the end of the year, only about 133 million dollars has been raised so far. However, if the GGA negotiations fail, it will also be the end of an alliance of African countries and friends of a serious fossil exit.

The new text for the GST declaration is far from reaching an agreement. Instead of reducing options and making it clearer for ministers, the text has been expanded to 27 pages. The especially controversial section on fossil exit has become longer and more extensive. Now, there are a total of eight different versions of the exit, along with specific formulations for ending coal, fossil subsidies, and an expansion target in the EV sector.

Formulations for direct exit range from very ambitious versions (“phase-out based on the best scientific knowledge, IPCC 1.5-degree pathways, and the principles of the Paris Agreement”) to practically purely technological proposals (expanding low CO2 footprint technologies and CCS expansion by 2030).

COP President Al Jaber has now named the Sherpa pairs, who will assist him in negotiations on specific topics. These are the respective ministers, traditionally paired industrialized/developing countries:

In the GST round, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock will negotiate for the EU, it was announced on Friday. Baerbock arrived in Dubai yesterday and stated that she expects “heated arguments” in the debates on the fossil exit, but “it must be an exit from fossil fuels, not just emissions“. This positions her against the COP presidency’s line. Concentrating only on renewables and efficiency will not lead the conference to a 1.5-degree path.

On Friday, negotiators received support for an ambitious exit from business, politics, civil society, and science. An open letter with 800 signatories, including Richard Branson, Christiana Figueres, and Vanessa Nakate, called on Al Jaber to achieve a negotiating result for the GST that must be a historic legacy of COP28. This includes:

In numerous stages, panels and press briefings in Dubai, Europe faces criticism for its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – especially from the so-called BASIC countries (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China). The CBAM allegedly contradicts the principles of the Paris Climate Agreement of “equality and common but differentiated responsibilities”. In other words, the main contributors to climate change – the industrialized nations – should not shift their responsibility to act onto weaker developing countries, even though all must work together to curb global warming.

The EU defends itself, considering the COP the wrong forum to discuss trade policy and reaffirms that the CBAM has been strictly designed according to WTO criteria. From EU sources, there is suspicion that the BASIC accusations hide a negotiation strategy. It is not clear what the BASIC countries want in return. Still, they may be seeking an excuse not to work on effective carbon pricing. EU negotiators also state that the issue does not come up in the negotiation rooms but is limited to public statements by BASIC government representatives.

The CBAM was introduced to prevent European producers, who will have to pay the European CO2 price in the future, from being disadvantaged on the international market. To avoid carbon leakage, imports of cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers and electricity from outside the EU will be subject to a carbon tariff equal to the EU CO2 price from 2026. Unless foreign producers also pay a carbon surcharge in their own country. For the EU, the CBAM is also a means of incentivizing carbon pricing in other EU countries.

The BASIC countries see CBAM as “sanctions on low-carbon products” restricting technological investments and green trade. A corresponding proposal is included in the latest draft of the most important document of COP28 – the global stocktake- on the insistence of these countries. Although the criticism is not directed only at the EU CBAM but also at the EU Deforestation Law and the US Inflation Reduction Act, the central accusation against Europe is that CBAM prevents particularly developing countries from implementing decarbonization measures for their industries. This is because export products become more expensive due to the carbon surcharge, violating WTO rules and the Paris Climate Agreement, as foreign producers are disadvantaged in the EU market.

The accusation of violating WTO rules is not new. It arose while EU lawmakers were still negotiating the exact design of CBAM. Therefore, various countries and parliamentary groups within the EU insisted on a legal text along the WTO rules of treating foreign and domestic products equally and treating all trading partners equally. The result: All importers into the EU internal market must pay the same fee for the direct greenhouse gas emissions of their products, as European producers do.

While CBAM does create a level playing field, according to Linda Kalcher, founder of the Brussels-based think tank Strategic Perspectives, “not everyone can play equally”. Countries in the Global South understandably fear that CBAM will block their access to the EU internal market. For example, many African countries do not have the same financial means to decarbonize at the same pace as European producers, says Kalcher.

Another problem, according to Kalcher, is that the revenue from CBAM goes into the EU budget. Although there is a reference in the legal text that the EU should continue to provide funds for climate adaptation and emissions reduction in the least developed countries (LDCs) – also through CBAM funds – there is no obligation, let alone a defined share for this purpose. Whether the criticism of the BASIC countries was just a tactical maneuver or they actually demand constructive talks will be seen throughout the week, believes Kalcher.

Dutch Social Democrat Mohammed Chahim, CBAM rapporteur for the European Parliament, considers most of the criticism a misunderstanding. Even in Commission circles, there is little openness to criticism, as it involves working with false claims. Between 2026 and 2040, China is expected to export around 869 million tons of CBAM-liable goods to the EU, according to forecasts by S&P Global Commodity Insights. According to S&P, this would correspond to over 201 million tons of embedded CO2 emissions (CO2 equivalents) credited under CBAM.

Since only direct emissions – those from the production process itself – are covered by CBAM, the instrument’s impact on export prices is significantly lower than claimed by BASIC countries. Indirect emissions – those from electricity generation for the production process – are only affected by CBAM in limited cases.

Sven Harmeling, Coordinator for International Climate Policy at the aid organization CARE, considers the BASIC countries’ move a “call for attention”, not having the impact to significantly influence negotiations. However, he also points out that the EU has not explained how CBAM works well and offered little help to fulfill CBAM criteria.

EU Parliamentarian Chahim can understand why countries are concerned about the impact on their industries. Therefore, he is willing to discuss these concerns with everyone and is ready to adapt the law if necessary, he said in an interview with Table.Media.

Regenerative agriculture, re-wetting of moors or large-scale afforestation – all these fall under the category of “Nature-Based Solutions” (NBS). The idea is to use nature to advance climate solutions and build resilience. Many approaches also focus on how ecosystem services can be financially compensated, known as Payments for Ecosystem Services. The concept of NBS has been around for a while, but it gained prominence in climate negotiations since COP26 in Glasgow.

Ideally, such nature-based approaches combine various benefits, so they have ecological or social advantages in addition to climate protection. This could include linking poverty reduction and climate protection or mitigating the impacts of climate change by sequestering carbon, with simultaneous benefits for biodiversity conservation. Biodiversity conservation also poses significant challenges: Last year, at the Biodiversity COP15, countries agreed to protect 30 percent of the land and sea area by 2030. To achieve this, climate protection must be considered together with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Loss of biodiversity and the collapse of ecosystems worsen the impacts of the climate crisis and make adaptation and resilience more challenging. At the same time, the topic also offers opportunities: Nature-based approaches could save up to ten gigatons of CO2 per year. That’s about a quarter of current emissions and could slow global warming by 0.3 degrees. The issue is closely related to forest protection, for which we have also published another background.

Incorporating nature-based solutions and biodiversity conservation into the UNFCCC climate action process is not easy. This is partly because it is challenging to define clear categories and indicators for it. Nature or water and species protection are difficult to quantify. However, it is quite certain that biodiversity conservation also requires additional billions. The concept is challenging to grasp because it encompasses so many different ideas. NBS are considered particularly cost-effective because they combine various benefits.

An example of how nature-based solutions have already been integrated on a large scale is the REDD+ mechanism (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) from Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. This rewards developing countries for preserving forests instead of deforestation. The efficiency of the mechanism is controversial. Carbon markets and the trade of CO2 certificates are also part of NBS.

For years, it has been criticized that “nature-based” is not precisely defined enough. It is also criticized that the term is often equated with the compensation of CO2, which could make misleading promises. In addition, it allows for a lot of greenwashing. Some critics also express that nature-based solutions are based on the approach of giving nature an economic value.

Nature-based solutions and biodiversity are not discussed separately at COP but emerge as cross-cutting themes in other areas, such as food systems and agriculture. Possible outcomes include commitments to financing and demands for better support in maintaining ecosystems, especially in the Global South.

Dec. 9; 9 a.m, Al Waha Theatre

Event From Agreement to Action: Harnessing 30X30 to Tackle Climate Change

The event will address the intersection between climate change and biodiversity loss. It will discuss how to achieve the goal of providing 200 billion US dollars annually for the conservation of biodiversity by 2030. Info

Dec. 9; 11.30 a.m., SE Room 4

Side event The 2023 IMO GHG Strategy: defining the global level-playing-field for shipping decarbonization

At the side event, the International Maritime Organization and the International Renewable Energy Agency, among others, will discuss how shipping can be decarbonized. Info

Dec. 9; 2:30 p.m., Knowledge Stage

Panel discussion Forging a Sustainable Future for Oceans

The event will discuss how climate finance can be mobilized to protect the oceans. Nature-based solutions for the oceans will also be discussed. Info

Dec. 9; 3:30 p.m., European Pavilion

Panel discussion The role of Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms in promoting carbon pricing initiatives worldwide

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is designed to prevent the production of energy-intensive goods from being relocated to countries with lower environmental standards. At this event, experts from different regions will discuss how it affects carbon markets around the world. Info

Dec. 9; 4:30 p.m., Deutscher Pavilion

Discussion Nature-based Solutions meet Circular Economy: cascading use of biomass

At the event, Environment Minister Steffi Lemke and Agriculture Minister Cem Özdemir will talk about the intersection between nature-based solutions and the circular economy. Info

Climate policies have deteriorated in many countries, and the world is making little progress toward the Paris Climate Agreement goals. This is the conclusion of the new “Climate Change Performance Index 2024” by Germanwatch and the New Climate Institute. None of the 63 countries examined is on a path compatible with the 1.5-degree target. In the climate policy sub-rating, not a single country scores “good” for the first time. The index assessed the climate policy, emissions, renewable energy metrics, and energy consumption of the countries.

“We must now switch to emergency mode,” urged Niklas Höhne, climate researcher and co-founder of the New Climate Institute. Germany’s good ranking is due to the even worse performance of many other countries. Measured against the Paris Climate Agreement goals, Germany performs mediocre in all four categories. The government needs to do more in transport policy and the building sector. The faster expansion of renewable energy is positively evaluated.

The United States, China and the COP host, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), perform very poorly. In the United States and the UAE, per capita emissions are well above the global average. China has also exceeded the average. Positive aspects include US investments in economic restructuring (Inflation Reduction Act) and the expansion of renewables in China. In the UAE, renewable energy accounts for less than one percent of the energy mix, but new capacities are expected to come online soon.

One of the biggest climbers in this year’s ranking is Brazil. The new climate policy under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, with plans to halt deforestation, has a positive impact. However, the country is expanding coal, oil and gas production. One of the biggest losers is the United Kingdom. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak wants to increase oil production and even build a new coal mine. The country is now weak in the expansion of renewables.

India surprises with a positive performance. The country has very low per capita emissions. However, the rise in emissions could cause India to fall in future rankings. nib

Azerbaijan is set to host COP29 next year, following an agreement with competitor Armenia. The host for the next climate conference was uncertain for some time. Russia had declared it would veto any application from an EU country. The EU imposed sanctions on Moscow for its invasion of Ukraine.

Azerbaijan confirmed late on Thursday that it had reached an agreement with Armenia, allowing Baku to apply to host the COP29 talks without the risk of an Armenian veto. Armenia has agreed to support Azerbaijan’s bid to host COP29 and, in return, will receive membership in the COP Bureau of the Eastern European Group.

Some delegates at COP28 have expressed concerns about holding global climate negotiations in an oil-producing country for the second time in a row. Azerbaijan is an oil and gas producer and a member of OPEC+. “Despite Azerbaijan being rich in oil and gas, Azerbaijan’s strategic goals include diversification of energy and resources, particularly in the field of wind and solar energy,” said a spokesperson for the Azerbaijani Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Reuters. nib/rtr

Canada aims to reduce emissions from the oil and gas sector by 35 to 38 percent by 2030 compared to the 2019 reference level through a cap-and-trade system. The draft plan, presented at COP, outlines that companies exceeding emission limits can purchase offset certificates in the future. The emissions trading is expected to commence no earlier than 2026.

Under the new emissions trading system, Canada sets a cap not on production but on emissions from the oil and gas sector. The cap is intended to be gradually lowered over the years. The trading system would encompass all greenhouse gases and apply to oil and gas producers, offshore facilities, and LNG producers, covering approximately 85 percent of sector emissions.

Environmental organizations had advocated for an emission cap of 110 megatons by the end of the decade. According to current plans, the cap is likely to range between 106 and 112 megatons. Additionally, the oil and gas industry could emit an extra 25 megatons, offset through the purchase of offset certificates or contributions to a decarbonization fund.

While environmental groups welcome the plan, they emphasize the need for a substantial reduction in the cap post-2030. Representatives from Greenpeace Canada state that the draft contains “weak targets and loopholes“. NGOs also criticize that the trading system is likely to come into effect too late to achieve Canada’s national climate goals (NDCs). kul

Amid record heatwaves, intensifying and costly extreme weather events, and increasingly dire warnings that climate change is literally killing us, calls to abandon fossil fuels grow louder. But the fossil-fuel industry is doubling down with investments in new oil and gas projects and major corporate mergers, walking back climate pledges, and making false promises that they can keep pumping without polluting. We need to ditch fossil fuels. But how?

The answer is unlikely to emerge from this year’s petrostate-hosted United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai, which could deliver a political commitment to phase out fossil fuels but won’t chart the pathway to a fossil-free future. To address what UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called “the poisoned root of the climate crisis,” we must look beyond the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to forge new forums fit for this purpose.

The good news is that Guterres, the pope, numerous national governments, and bodies like the International Energy Agency have joined the growing global call for a phaseout of coal, oil, and gas. At the UN Climate Ambition Summit in September, governments acknowledged that the climate crisis is a fossil-fuel crisis. The question is not whether to move beyond oil and gas, but how.

The bad news is that the fossil-fuel industry, buoyed by record-breaking profits in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, seems impervious to such pressure. Worse, these colossal profits are being reinvested in more oil and gas development. As climate disasters intensify before our eyes, the industry responsible for nearly 90% of carbon dioxide emissions is betting that its dirty products will be a mainstay of the global economy for decades to come.

To force a change, we must expose the economic fragility that fossil-fuel dependence creates and its broader toll on human rights. Reliance on oil, gas, and coal makes communities more vulnerable to supply disruptions, affecting everything from heating and transportation to food prices. Such disruptions fall hardest on the most impoverished populations while boosting the industry’s profits.

It is worth recalling that fossil-fuel companies underperformed the market for the ten years preceding the war in Ukraine. That decade of decline reflected long-term energy-transition trends that the recent uptick in earnings has not changed. With fossil-fuel demand projected to peak globally by 2030, oil and gas remain a bad bet.

Part of the problem is that governments have responded to price volatility by increasing fossil-fuel subsidies, rather than imposing windfall taxes. They also have continued to approve new oil and gas projects, including offshore in protected ocean areas. Planned production is double what’s compatible with the target of limiting global warming to 1.5° Celsius above pre-industrial levels; there is simply no room for new oil and gas supply if the world is to avoid climate catastrophe.

Fossil fuels appear competitive with ever-cheaper renewables only because their production has been subsidized and their producers insulated from the costs associated with the damage they cause. The industry’s negative externalities, long borne by frontline communities, are now being imposed on people around the world in the form of wildfires, hurricanes, floods, and droughts. If we compelled fossil-fuel companies to shoulder the losses they long saw coming, and redirected public funds to renewable solutions, oil and gas assets would be exposed as the liabilities they are.

This points to another big problem: corporate capture. Although climate litigation is key to holding the industry accountable, the challenge is not just to make polluters pay for the harms they cause. We also must diminish their outsize influence on climate policy. Despite the best efforts of movements like Kick Big Polluters Out, the fossil-fuel industry not only has a seat at this year’s climate talks; it is at the head of the table.

There sits Sultan Al Jaber, the CEO of the United Arab Emirates’ national oil company, which is currently pursuing its own expansion plans. Al Jaber, COP28 president, is intent on portraying the fossil-fuel industry as the hero, not the villain, in the fight against climate change. Yet this is a well-known survival strategy for an industry in long-term decline. So, too, is the UAE’s advocacy of an “all of the above” approach that promotes renewables as a complement to fossil fuels, rather than a replacement for them, and that champions carbon capture and offsets, despite abundant evidence that neither leads to significant emissions reductions.

Contrary to what Al Jaber suggested earlier this year, the problem is not just with fossil-fuel emissions; it is with fossil fuels themselves. Focusing only on carbon ignores all the other negative effects of fossil fuels, including their impact on health, such as the eight million premature deaths from air pollution annually.

Though fossil fuels are overwhelmingly to blame for climate change, our UNFCCC-led climate regime has failed to address them, even before the industry was handed the gavel. For decades, the international body that should be leading the fossil-fuel phaseout has conspicuously avoided the issue. Neither the 1992 UN Climate Convention nor the 2015 Paris climate agreement mentions oil, gas, or coal.

This omission was not some casual oversight. It is a symptom of a deeper crisis in global climate governance. Because UNFCCC decisions require a consensus among 198 members, powerful countries can block progress and assure lowest-common-denominator outcomes, or none at all.

COP28 further underscores the need for alternative processes to manage the decline of fossil fuels, free from the influence of those who profit from them. Every day provides new reminders of why we need to phase out oil, gas, and coal. Fortunately, initiatives like the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, and the Global Parliamentarians’ Inquiry offer new ideas about how to do it. Governments must commit to a forum dedicated to fossil-fuel phaseout so the real work of ending the fossil-fuel era can begin.

Nikki Reisch is Director of the Climate and Energy Program at the Center for International Environmental Law.

In cooperation with Project Syndicate, 2023.