We feel the same way: Just before Christmas, we don’t want to be confronted with all the misery of global climate action again. That is why we searched for stories that would offer encouragement and spread a bit of hope. At first, we thought this would become a small section of this Climate.Table. Then it turned out – despite all the caution about greenwashing: There is indeed halfway positive news.

This is also thanks to the rather successful end of the Biodiversity Conference COP15 in Montreal. We analyze what impact COP15 will have on global climate action. And climate expert Hans-Otto Poertner explains what the conference accomplished, what is still missing, and what it means for Germany.

We have also compiled positive trends from the year 2022. And on top of that, the latest reports that just dropped on our desk: The rapid growth of electric buses worldwide, Indonesia’s surprising success in forest conservation, the incredible advance of renewables, and the negotiations for a new global plastics agreement.

This Christmas issue also comes with special selections for relaxed reading and listening: Journalistic articles that look at solutions surrounding the climate crisis. And a selection of podcasts to top it all off.

And if all the darkness drags you down as it does us, take comfort in the fact that the days are getting longer again. The light is coming back. And after taking a short breather next week, we will be back at the beginning of January with a comprehensive outlook on an exciting year 2023.

Have a restful time and a healthy New Year.

Mr. Poertner, how does the result of the biodiversity COP15 benefit the global climate?

Climate action and biodiversity conservation go hand in hand. Both crises, climate change and species extinction, threaten the very existence of humankind and many other species. Among other things, the natural environment is a tremendous carbon sink. Almost one-third of global man-made emissions can be traced back to agriculture and forestry. When we destroy forests, drain peatlands, and use fields so intensively that soils degrade, we release that carbon. Additionally, excessive factory farming causes massive emissions of nitrogen oxides and methane. And species-rich ecosystems are far more resilient to climate change than others.

Against this background, what is your assessment of the decisions made in Montreal?

The most prominent target agreed upon in Montreal states that 30 percent of the global land and 30 percent of the global ocean should each be protected by 2030. That makes sense because healthy ecosystems require a certain amount of land. But the 30 percent is a provisional average. Actually, such a protection quota needs to be specified and adjusted for each ecosystem individually.

Can you give an example?

Take the Amazon region with its extensive rainforest. It is of tremendous importance for biodiversity and at the same time a great carbon sink. The forest generates its own climate, especially the cycle of evaporation and precipitation, and thus sustains itself. However, for the water cycle to function, it is necessary to maintain more like 80 percent of the forest area. 30 percent is not enough.

In 2010, UN biodiversity targets were already adopted once. None of them were achieved. Why should it work this time?

It is always difficult to implement such targets. This is demonstrated not least with the 1.5-degree limit set by the Paris climate agreement. The IPCC repeatedly stated how important it is not to exceed this threshold. Nevertheless, the debate is now raging as to whether the target can even be met. This is a disaster. I think the same thing will happen with the biodiversity targets, partly because the agreement is not legally binding. We should have talked much more about implementation right from the start – in Paris as well as now in Montreal.

What would it look like to talk specifically about implementation?

It is very important, for example, that soils remain healthy and fertile, because they are the foundation of our existence. But our agriculture often does the opposite: Through the use of pesticides, the spreading of liquid manure and fertilizers, plowing, clearing and disturbance of the water balance as well as erosion, the soils dry out and degrade. That means, gradually, the organic material disappears from the soil. This harms the climate, and in extreme cases, the soil is ultimately unfit for agricultural use.

Should we use protected natural areas for economic purposes at all?

This is often unavoidable, because mankind populated just about every ecosystem on earth. In these cases, along with respect for biodiversity, we also need sustainable uses. In the first joint report of IPCC and IPBES, we proposed the concept of a mosaic approach for this purpose: Very well protected spaces must be connected by corridors and adjacent to sustainably used spaces. In this way, species can migrate, which is important for genetic exchange. We need such migration corridors all the more with climate change, because the climate zones are shifting and many animal and also plant species can only escape the less favorable living conditions by migrating.

What could such a mosaic look like in Germany?

Germany already has various types of protected areas. To some extent, however, this is also deceptive labeling: Just think of the intensively used Wadden Sea. Certainly, we could expand the intensively protected areas toward 30 percent, use them sustainably in some cases, and interconnect them, but in my opinion, implementation also involves challenges. For the 30 percent target now adopted, we would have to renaturalize our already degraded soils and ecosystems. And we would also have to be prepared to abandon or relocate infrastructure if necessary.

What does that mean, for example for road construction?

Germany should stop building new Autobahns. It is no longer appropriate and contradicts the 30 percent target set in Montreal. Strengthening the existing transport network should be sufficient. We need to reduce individual traffic and motorized traffic on our roads, not increase it further.

What must German policymakers do now to better protect biodiversity?

First of all, the different agencies will have to talk to each other. We need to think about protecting biodiversity as part of climate action, and vice versa, because the loss of biodiversity drives climate change, and vice versa. Then we have to rethink spatial planning in such a way that it becomes clear which ecosystems we want to protect in which regions, and also make a contribution to biodiversity protection at the international level. Subsidies must be redirected to serve sustainability. Agriculture must be transformed so that it is resilient to climate change, and in such a way that climate action and biodiversity benefit. And humans, of course, too.

By 2025, as part of the funding of 200 billion dollars per year, 20 billion dollars will flow from industrialized countries to poor countries each year. Do you think this distribution is fair?

I think that when it comes to conserving biodiversity, each country has an obligation to restore and protect its own natural areas. We can contribute by no longer buying products that require the clearing of rainforests. One example I have in mind is our meat consumption and our factory farming, which relies on soy from South America. In global climate policy, there is the idea of ‘Common But Differentiated Responsibilities’, which states that primarily industrialized countries are obliged to protect the climate and finance it. In biodiversity conservation, I do not think this is quite as justified. And in the meantime, emerging countries like China should also make their contribution to climate and climate policy. After all, around 60 percent of global emissions now come from the so-called developing countries. Economic development should also be linked exclusively to the use of renewables. This, too, serves both climate action and the conservation of biodiversity.

Many countries in the Global South demand money from industrialized countries to preserve their natural environment. Is this justified?

It goes without saying that we have to help countries that are not as well positioned materially. And of course, the countries with the most resources should be the first to do so. Ultimately, it is in the interest of the entire global community to preserve ecosystems, especially if they are large carbon sinks like the Amazon, for example. But the deciding factor is that the motivation for nature conservation must come from the countries themselves. They must wish to conserve their natural resources. If they don’t, then the most generous financial aid will be useless. The mentality of saying: We provide the biodiversity and others should pay for it because they have a special obligation to protect the climate because of their history – I don’t believe that is sustainable in the long term. Humanity is facing a planetary crisis, and it has to be tackled together as a global community. We are all in the same boat!

Hans-Otto Poertner is an ecologist, climate scientist and co-chair of IPCC Working Group II since 2015. He heads the Department of Integrative Ecophysiology at the Alfred Wegner Institute.

In mid-December, the energy companies Saudi Aramco and Total announced a gigantic project: With an investment of 11 billion dollars, the Saudi and French companies plan the complex “Amiral” on the east coast of Saudi Arabia, one of the largest petrochemical factories in the world. Here, 7,000 workers will soon produce, among other things, the basic materials for carbon fibers, lubricants, detergents and car tires. In parallel, the chemical company Ineos is constructing a new ethane cracker in the Belgian port of Antwerp for 3 billion dollars.

The petrochemical industry is expanding worldwide. At the same time, however, it becomes increasingly clear how crucial the industrial policy surrounding plastic is for climate action as well. After all, the substance is not only so dangerous to the environment as waste, that the UN Environment Program Unep warns about plastic and its significant and growing contribution to global emissions.

An international plastics treaty, which was launched in early December with initial meetings in Uruguay, is supposed to solve these problems. The next negotiations on the “Plastic Treaty” are also crucial to the Paris climate agreement and the remaining carbon budget.

In 2015, plastic was responsible for 4.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. The forecast: The share could triple by 2100. This means that by 2050, more than 10 percent of the remaining global carbon budget for plastic could be used up, according to calculations by the Center for International Environmental Law. Emissions occur in all seven steps of the life cycle of plastic:

90 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the plastics cycle are generated during the extraction and conversion of fossil raw materials. The so-called cracking process, where intermediate products for plastic production are created from crude oil, requires particularly large amounts of energy. Damage to local ecosystems and the global climate coincide at the latest during disposal.

Incineration generates the highest emissions and is expected to increase over the next few years. Production also continues to rise. Over 400 million tons of plastic are produced every year. Current projections assume that production will double in the next 20 years.

How could emissions from the plastics sector be reduced? This was modeled in a recent study in the Nature journal: If the conditions of

would be met, the sector could even become a net carbon sink by 2100.

So far, however, there has been no mention of this in the planned plastics treaty. If all goes well, such a legally binding treaty will be signed by UN member states in 2024 in order to tackle the global plastics problem. The first meeting of the relevant Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee, INC-1, took place at the beginning of December. About 2,000 delegates from 160 countries initially exchanged views in Uruguay on the scope and rules of the negotiations. Two conflict lines have already emerged:

Saudi Arabia and the United States spoke out right at the start in favor of a bottom-up agreement on plastic waste. A coalition of 40 negotiating parties, including the EU, host Uruguay and the United Arab Emirates, on the other hand, not only want to regulate waste, but start at the source – and reduce production to a sustainable level. They want to rely on a circular economy and bans on toxic chemicals. To this end, a global basis and internationally binding targets are to be formulated. The next round of negotiations, INC-2, is scheduled for May 2023 in Paris.

Crude oil and natural gas extracted during fracking are the basis for global plastics production. About 98 percent of disposable plastic products are still obtained from these fossil feedstocks. 12 percent of crude oil is converted into petrochemicals. The share is growing. But the main product from oil is and remains fossil fuels.

While discussions regarding the plastics treaty still focus on how decisions are to be made in the first place, the EU is already one step ahead. Since July 2021, the Single-Use Plastic Directive has been in force, which bans several products made of single-use plastic and is intended to initiate the transition to a circular economy. At the end of November, the EU Commission implemented two other key aspects of the Circular Economy Action Plan: A revision of the Packaging Directive to reduce packaging waste in EU countries by 15 percent by 2040 compared to 2018. And a non-binding guideline for bioplastics, which specifies under which circumstances bioplastics make ecological sense.

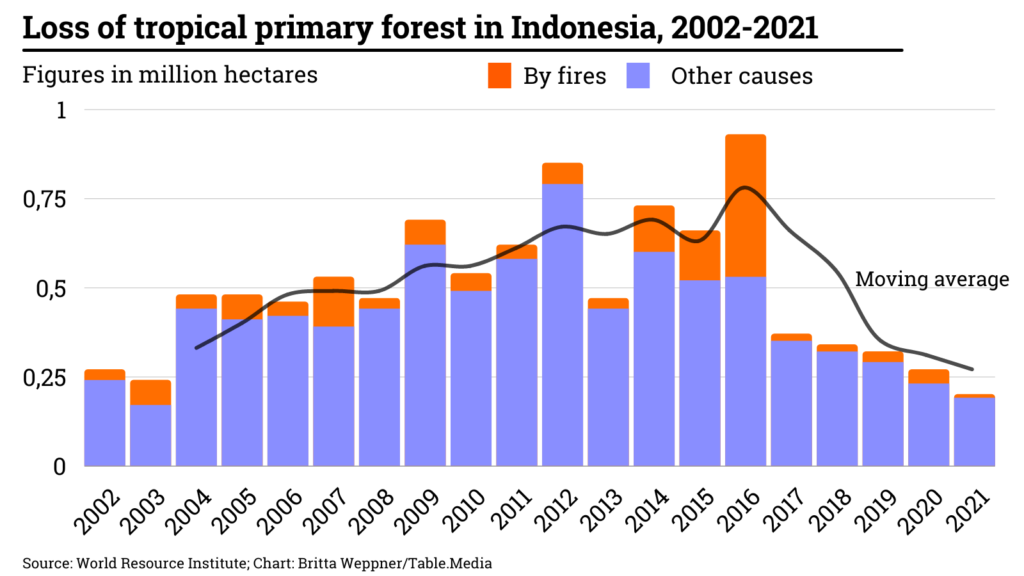

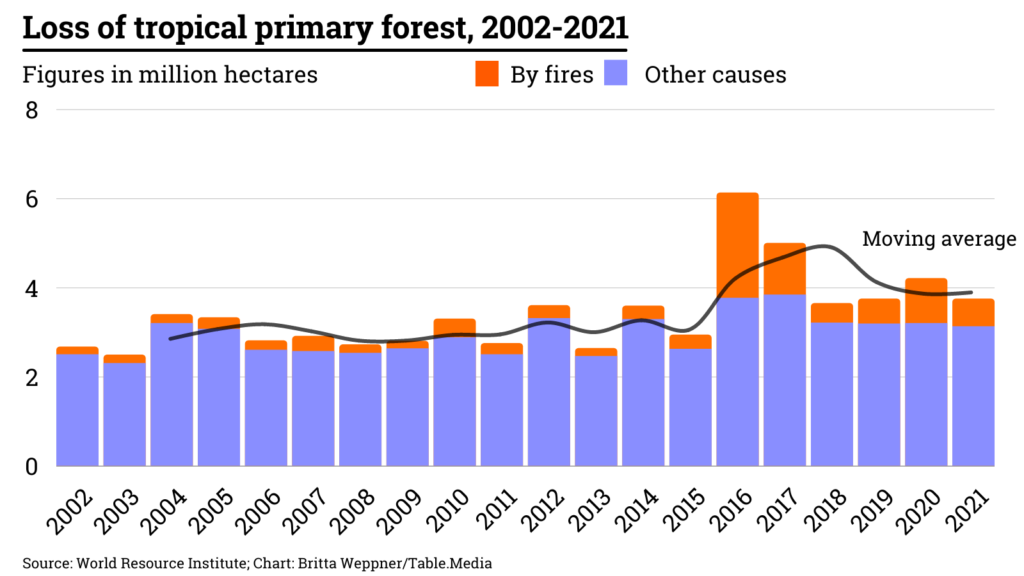

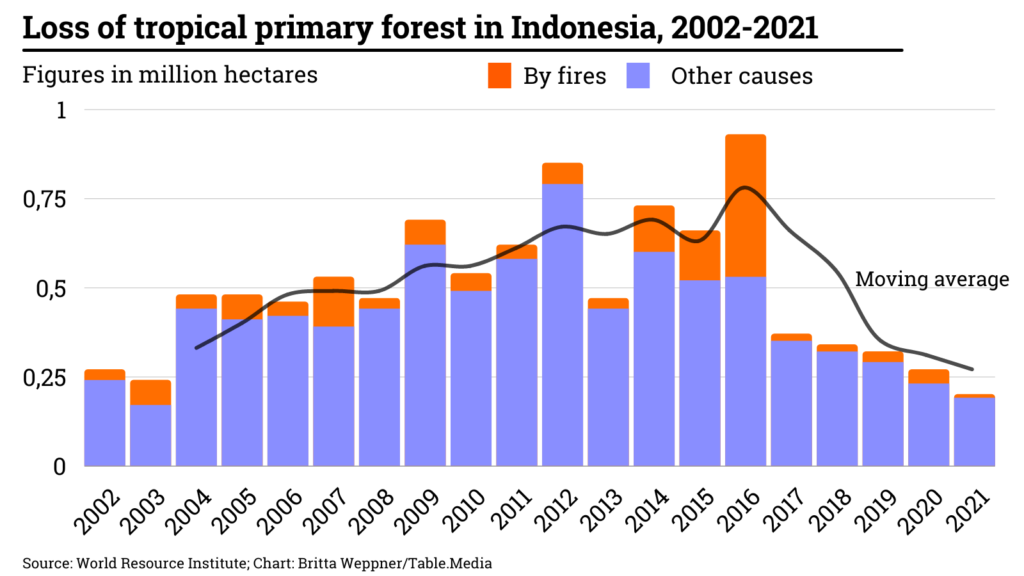

Indonesia seems to be succeeding in something that other countries find difficult: Over the past five years, deforestation has slowed sharply. Mikaela Weisse and Elisabeth Goldman of the World Resources Institute (WRI) analyzed the data released in spring and see it as a reason to celebrate.

For a long time, Indonesia was one of the countries where deforestation was a particularly big problem: Between 2002 and 2021, 10 million hectares of virgin forest were destroyed there – only Brazil had more in the same period. The main reason for this was the large amount of land required for the palm oil industry.

The background: More than half of the world’s tropical rainforest is located on the territory of Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia. How well the three countries manage to protect the forest is, therefore, particularly important for the global climate. According to WRI data, Indonesia currently still has around 84 million hectares of tropical virgin forest. In the DR Congo, the figure is around 99 million hectares, and in Brazil around 315 million hectares.

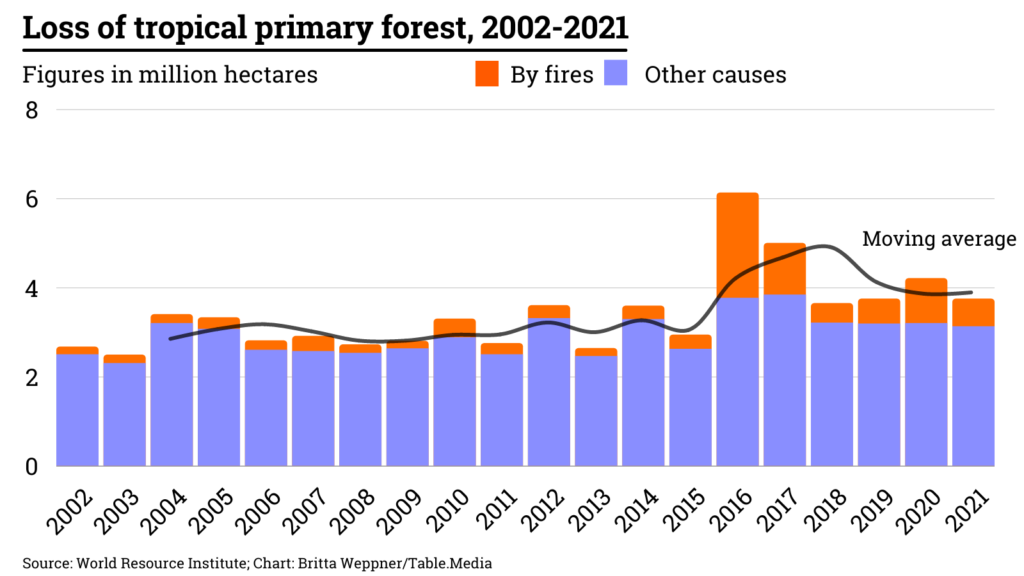

But although tropical forests are an important carbon sink, their destruction is progressing rapidly. Some 11.1 million hectares of forest were lost in the tropics in 2021, according to the Global Forest Watch (GFW) initiative. Of these, 3.75 million hectares were virgin forests. Their loss alone released 2.5 gigatons of carbon emissions, almost as much as India releases into the atmosphere in a year.

This makes the news of success from Indonesia all the more important for the global climate. Deforestation has not been stopped, but it has decreased more than elsewhere.

WRI sees two main reasons for this: Voluntary commitments by the industry and stricter policies.

To meet the Glasgow Declaration on Forest Conservation, deforestation rates worldwide must fall much faster than they have so far, say experts like Friedrich Bohn of the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) in Leipzig. For WRI experts Weisse and Goldman, Indonesia gives cause for hope. The rapidly declining deforestation rates are “a massive success that did not seem likely five years ago.”

One lesson is that industry commitments can work when combined with clear legal requirements from the government and strict controls. To be sure, the means to truly enforce forest conservation are often lacking, writes Frances Seymour, Distinguished Senior Fellow at WRI on Tropical Forests. “But the biggest limiting factor is the lack of political will.”

Brazil and Indonesia are “two of the most interesting departures” from the pattern of steady forest loss in the tropics, according to Seymour – Brazil in a negative way, Indonesia in a positive way. Both showed, in their own ways, how “government policy and corporate restraint” could work.

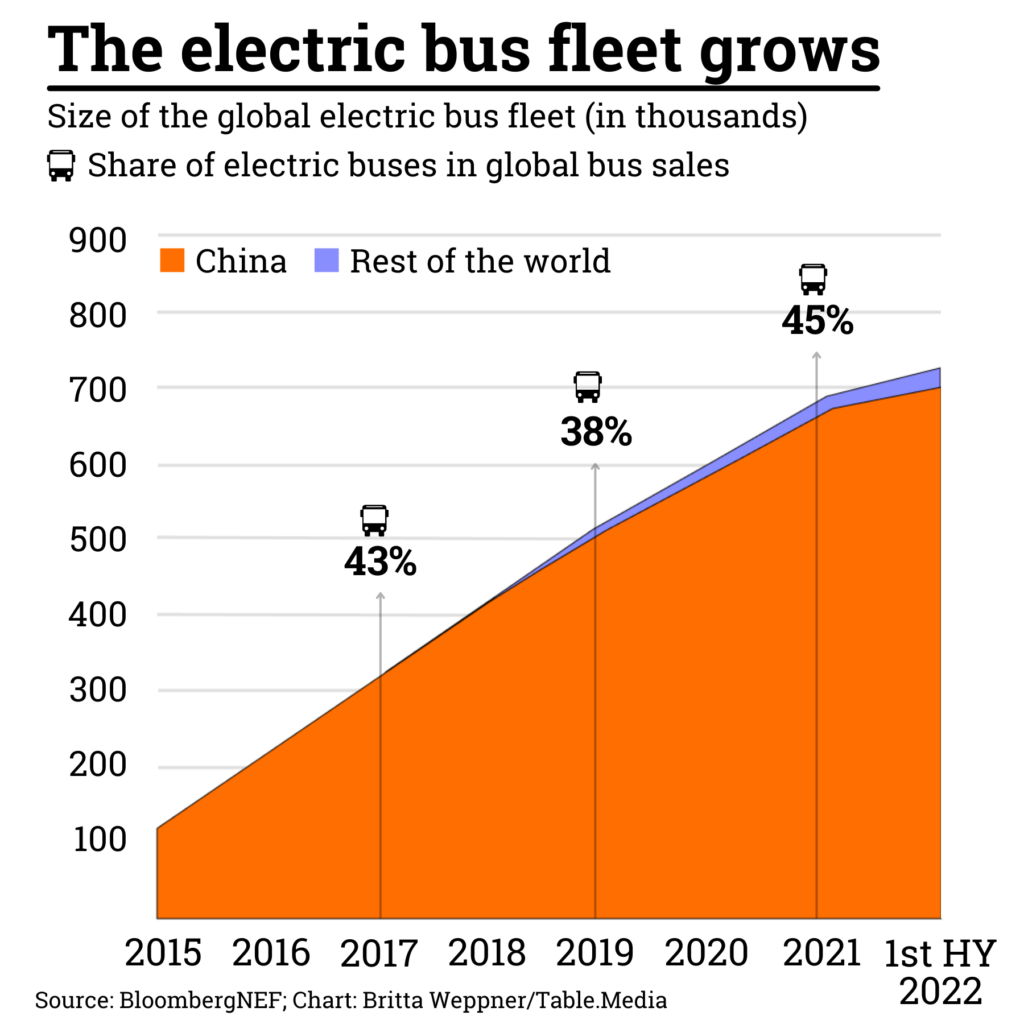

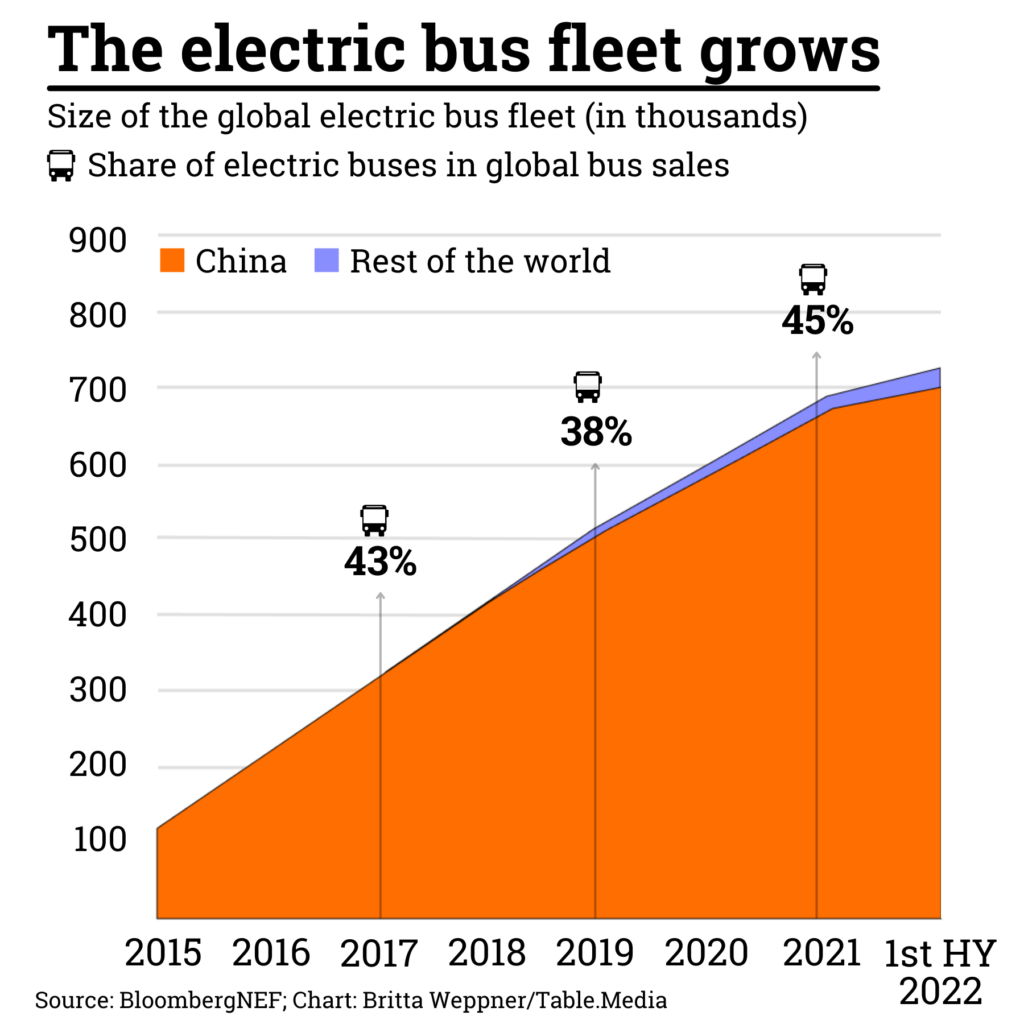

Electric buses have become a sales hit in recent years. In 2013, they accounted for just two percent of new bus sales. By 2021, almost every second bus sold was electric (45 percent). Their share of the global bus fleet has risen to 19 percent.

The trend in electric buses is one of the few silver linings in the “State of Climate Action 2022” analysis by climate NGOs and think tanks. Sales are going in the right direction to help the sector contribute to the 1.5-degree target. But they need to be stepped up further.

The Chinese electric bus boom is the result of subsidies, regulations, infrastructure construction, pilot programs, and an active industrial policy.

Since 2009, subsidies are being offered at the national and levels level:

Subsidies have since been reduced. They also served to boost the industry. After all, China’s government also promoted EVs for industrial policy reasons. The subsidies were therefore partly coupled to technical parameters such as energy consumption and battery range. In addition, financial aid was available for the development and research of electric buses. The Chinese company “Build your dreams” (BYD) is now the global market leader for electric buses and started production in Europe in 2017.

Many Chinese cities have also provided the necessary charging infrastructure. Bus depots and bus stops have been fitted with charging points.

Environmental regulations have also contributed to the success of electric buses. To reduce urban air pollution, the number of diesel vehicles and subsidies for internal combustion buses have been reduced. Since 2015, the number of conventional buses has fallen by an average of ten percent per year, according to GIZ.

Electric buses can yield major benefits for the climate. If they are operated with 100 percent renewable energies, “electric buses emit only 15 percent of the emissions of a diesel bus in the most favorable case,” as a study commissioned by the city of Zurich shows. Even buses with the largest batteries emit only 25 percent of the greenhouse gases of comparable diesel buses over their entire life cycle.

In China’s booming market, however, the climate benefit is much smaller. Coal-fired power still dominates the electricity mix too. EVs manufactured in China in 2022, calculated over their life cycle and a distance of 250,000 kilometers, will save 27 percent in carbon emissions compared to internal combustion vehicles, according to the think tank BloombergNEF (BNEF). The numbers will hardly be better for electric buses. However, the expansion of renewables in the People’s Republic will greatly improve the emission footprint of electric buses, according to BNEF analysts.

The EU member states have agreed on minimum targets for clean buses in 2021. Depending on the member state and economic strength, between August 2021 and 2025, 24 and 45 percent of all newly procured public buses must be “clean” – half of which must be emission-free. Vehicles that run on gas or synthetic fuels are also considered clean buses. Countries such as France and the Netherlands have set themselves more ambitious targets. They only want to buy zero-emissions buses after 2025.

Some lessons can be drawn from China’s electric bus success:

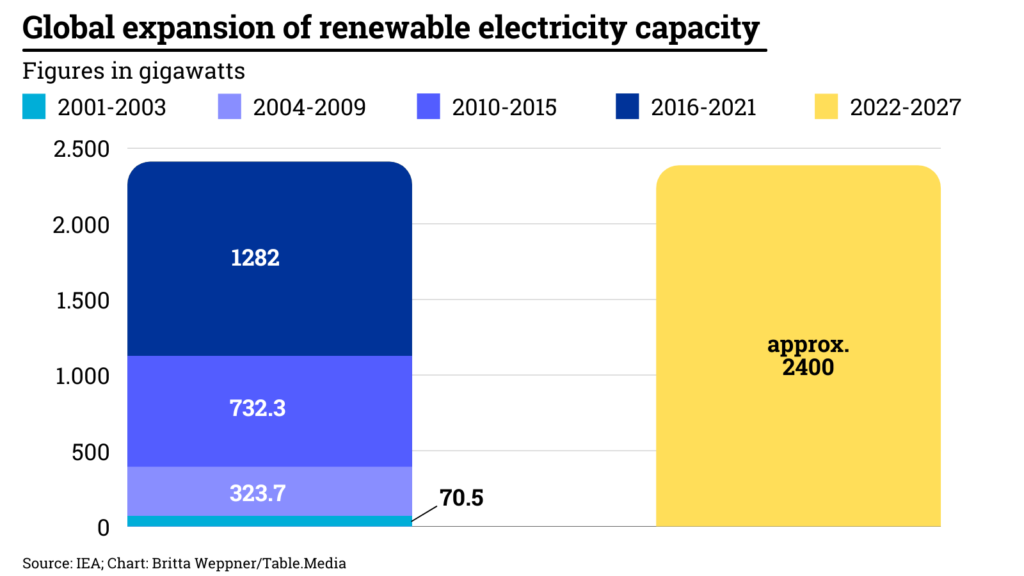

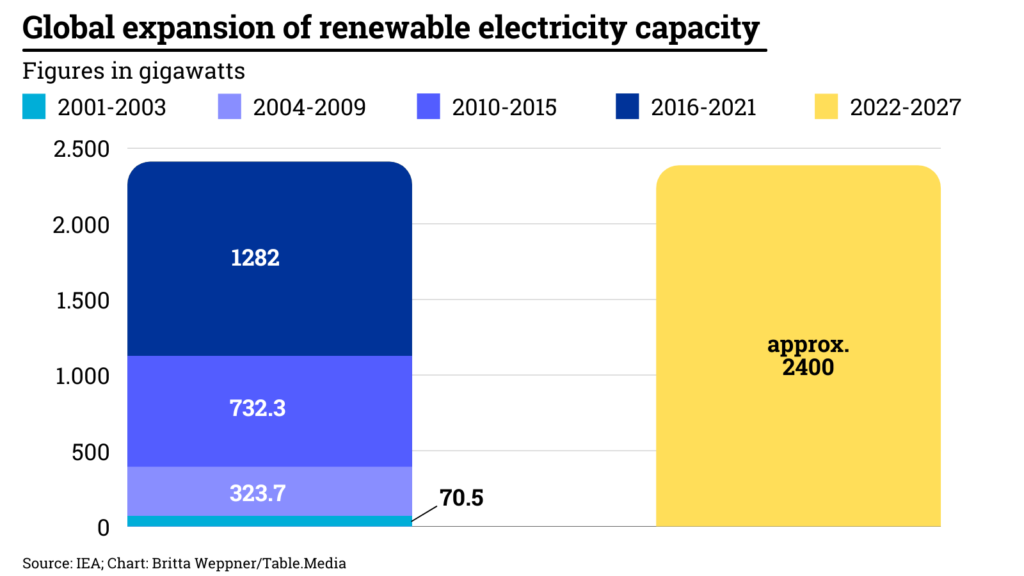

After two decades of rapid growth, renewables are poised to dominate the electricity market worldwide. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that in the next five years to 2027 alone, as much electricity capacity will be added from renewables worldwide as has been created in the last 20 years: around 2,400 gigawatts.

This is roughly equivalent to the total installed capacity of China – by far the largest producer of green electricity. Beyond renewables, according to the IEA’s medium scenario, there will be hardly any (10 percent) other additions to power plants.

According to the IEA figures, the solar industry, in particular, will expand strongly. In the five years to 2027, capacity is expected to practically triple from today’s level to around 1500 GW. In 2026, according to these estimates, photovoltaics will thus overtake the installed capacity of gas-fired power plants for the first time and coal one year later. Onshore wind capacity is expected to grow to 570 GW. The electricity harvest from offshore wind could increase six-fold to 600 TWh by 2030 compared to 2018.

The good news for the world’s climate is that the expansion of renewables is saving the atmosphere a lot of CO2: In 2021, the expansion of renewables alone accounted for around 220 million metric tons. The rapid expansion also means that China, the EU, and the US will reach their previously planned climate targets for 2030 earlier than previously announced.

Rapidly falling prices have now made solar and wind, in particular, competitive with fossil fuels in almost all parts of the world. Since 2010, for example, the cost of solar energy has fallen by 80 percent. The cost of batteries has also fallen by 97 percent over the past 30 years.

At the same time, government requirements and quotas for renewables are putting pressure. Climate action and air pollution control policies are important levers to pave the way for renewables.

But the current push for renewables has been triggered by Russia’s war of aggression on Ukraine, according to the IEA. “The first truly global energy crisis, triggered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, has created an unprecedented momentum for renewables,” says IEA chief Fatih Birol. The war highlighted how Europe, in particular, was exposed by its energy supply chains. And at the same time, he says, it drove up prices for fossil fuels to the point where renewables were paying off. By spring 2021, even green hydrogen produced with scarce green electricity in Germany was cheaper than hydrogen produced with gas.

The economic dynamics of renewables have long been massively underestimated by many experts. Even the IEA, today at the forefront of renewables advocates, has long doubted the green success story. From today’s perspective, even ambitious scenarios like Greenpeace’s 2015 “Energy Revolution” look tentative. The Ukraine war, in turn, shows how sudden political decisions can set in motion a dynamic that was previously considered unthinkable. Forecasts are only as good as the world doesn’t move in completely new directions.

Finally, even amid the general enthusiasm about the triumph of renewables, important questions remain unanswered:

The US Congress proposes the government in Washington provide one billion dollars of climate money for poor countries, reports the New York Times. The sum is significantly below President Joe Biden’s pledge, who said in 2024 the United States would provide 11.4 billion dollars “to ensure developing nations can transition to clean energy and adapt to a warming planet.”

According to the report, members of Congress are expected to vote this week on the proposal, which is part of a larger funding package totaling 1.7 trillion dollars. Democrats originally had wanted to earmark 3.4 billion for international climate programs as part of the package. Republicans rejected this.

“The Republicans are poised to assume control of the House in January,” the newspaper writes, “further dimming prospects for additional climate funds for at least the next two years.” Congress has now cut the president’s climate aid request for the second year in a row, the report added. Activists commented that the inability of Biden’s administration to meet its own goals hurts US credibility in the world. ae

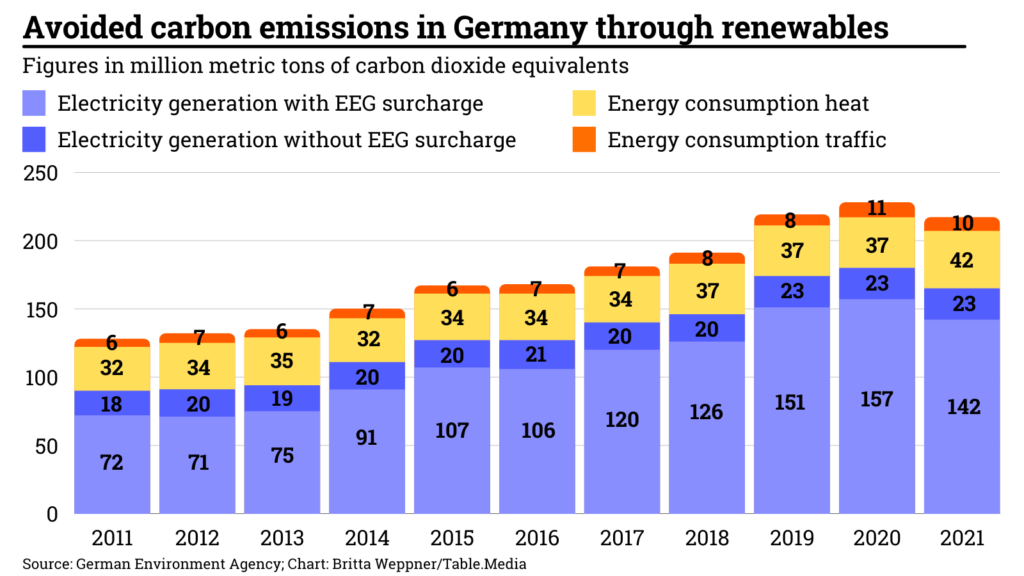

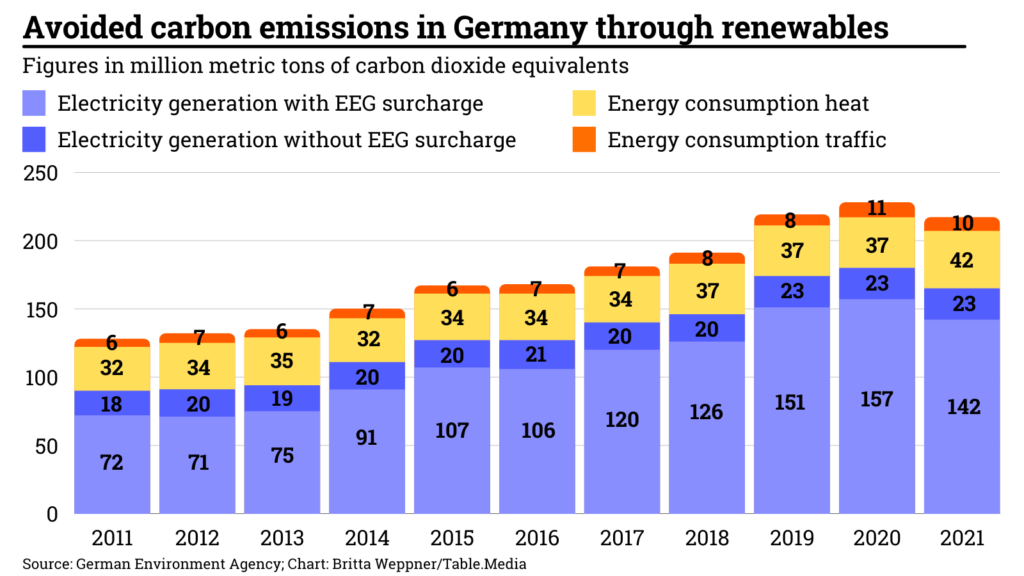

The use of renewables prevented greenhouse gas emissions totaling 217 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in Germany in 2021. This is roughly equivalent to the amount of greenhouse gases emitted annually by Austria, Switzerland, Ireland and Portugal combined. This is according to the emissions balance of renewables recently published by the German Federal Environment Agency (UBA).

“The results of the emissions balance show that the expansion of renewable energies contributes significantly to achieving the climate action goals in Germany,” the authority writes. In all consumption sectors, “fossil fuels are increasingly being replaced by renewable energies.”

CO2 avoidance comes

The calculations not only took into account the directly avoided emissions, but also the emissions from the upstream chain, such as the installation of plants or the procurement of fuels, according to UBA. Elaborate simulations also showed that about 80 percent of the carbon reduction was achieved by replacing fossil-fuel power plants in Germany, with only about 18 percent at foreign power plants.

The statistics also show that the use of renewables in the electricity sector is most effective in reducing carbon emissions. This is because although electricity accounted for only half of renewable electricity in 2021, at 233 TWh, it was responsible for 76 percent of carbon reductions. Electricity, heat and transport, on the other hand, required the other half of green electricity but delivered only 24 percent of the climate protection effect.

UBA’s latest data is for 2021, the first year in which less carbon was avoided by renewables after steady growth in the previous ten years. The reason, according to UBA, was less favorable weather conditions for the solar and wind sectors. bpo

Why did the concentration of methane in the atmosphere increase by 50 percent between 2019 and 2020, even though the economy in large parts of the world came to a virtual standstill due to the Covid pandemic? That has long puzzled researchers around the world. Now, a team of scientists has discovered clues pointing to solving the question.

In a study published in the Nature journal, they wrote that just under half of the increase, about 47 percent (with a variation of plus/minus 16 percent), was due to higher natural emissions, primarily from wetlands. The other half, around 53 percent (range of variation plus/minus 10 percent), was due to lower hydroxyl concentrations in the troposphere.

Hydroxyl (OH) reacts with gases in the atmosphere, including methane. This produces soluble compounds that can then be washed out of the atmosphere, so to speak. OH is therefore also known as the atmosphere’s cleaning agent. In 2020, the OH concentration in the troposphere decreased by about 1.6 percent compared to 2019, the researchers write.

Hydroxyl can form, among other things, through reaction with nitrogen oxide in the atmosphere – and during the pandemic, anthropogenic nitrogen oxide emissions fell significantly. According to the study, this was a major reason for the lower OH concentration. Nitrogen emissions would therefore have to be taken into account in the implementation of the Global Methane Pledge.

The results also showed that methane emissions from wetlands are sensitive to climate change and could amplify themselves in the future, the researchers write. ae

This year, it could be said that Christmas arrived a bit early with the ground-breaking agreement, concluded at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, to establish a global fund to help developing countries and deal with the wide range of losses and damages caused by accelerating climate change. Small islands in the Pacific and the Caribbean, which emit less than one percent of greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, as well as larger climate-vulnerable developing nations like the Philippines, welcomed the agreement with joy and relief.

Confronted with rising sea levels, warming oceans and increasingly destructive storms leading to the irreparable damage and loss of coastal and farmland, coral reefs, homes and the resting places of ancestors, they had called for such a facility for nearly thirty years. These calls were largely unheeded by the powerful till now.

Bearing witness and often acting as first responders to climate disasters, churches have supported these cries for reparations, recognizing at the same time that non-economic losses and damages, such as the forfeiture of human lives and the erosion of ancient cultures and ways of living, cannot be valued nor be truly recompensed in monetary terms.

The World Council of Churches (WCC) – has released a statement ahead of COP27 that urged for a “loss and damage financing facility to compensate communities and countries on the frontline of climate impacts and to support their efforts in building resilience” – was among those who celebrated the COP27 decision to provide vital financial support to those suffering from climate change.

The creation of the fund is a testament not only to the unity of developing country governments, but also to churches, faith-based groups and other civil society organizations coming together to monitor and reshape global climate negotiations – all of whom worked relentlessly and concertedly to eventually overcome opposition from wealthier, high-polluting countries such as the United States and those from the European Union.

The new loss and damage fund offers a kernel of hope. But it is a fragile hope. Currently, the fund does not hold any money and is yet to be operationalized. Plenty of work needs to be put in to ensure that it is adequately resourced and meets the needs of communities and women and children on the ground.

The biggest questions are: How much is needed? What mechanisms should be developed so as to reach those most affected? And, most contentious of all, who will pay for it – even though, in response to the latter question, the 1992 UN Earth Summit held in Rio de Janeiro which created the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change had already enshrined the Polluters Pay Principle. These thorny issues around implementation are expected to be threshed out at the next COP.

Taken as a whole, the decisions reached at Sharm El-Sheikh remain far from commensurate to the sheer enormity of the existential challenge of climate change. The latest scientific reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warn us that the window of opportunity for limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C and preventing the most catastrophic consequences of climate change is closing rapidly.

Greenhouse gas emissions must start falling by 2025, be halved by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050. But interests in protecting corporate profit margins and meeting national growth targets prevailed such that COP27 failed to deliver stronger language on phasing out fossil fuels nor the necessary cuts in emissions, putting the planet on a calamitous trajectory of 2.4-2.8 C warming by the end of the century.

Yet in spite of these failures, Christmas stirs hope in many of us – the hope of good news made flesh, of co-creating more equitable and sustainable economic systems and societies underpinned by values of solidarity and compassion, of keeping alive the Paris goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 C and securing a chance for a liveable future for our children and grandchildren.

This hope is evident in the few but courageous women leaders in the COPs who have consistently spoken truth to power. It is tangible in the young climate activists who have taken to the COPs, the courts and the streets to hold their governments as well as corporations to account for their roles in causing or aggravating climate change. This hope is palpable in movements of farmers and Indigenous Peoples who are challenging unjust and unsustainable systems of production and consumption that are at the root of the climate crisis by practicing community-based agro-ecology and non-marketized ways of exchanging products and services.

And it is made visible by churches that not only conduct prophetic advocacy at the COPs but also seek to “walk the talk” by practicing climate-responsible finance and contributing to efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change in their daily operations. In other words and to paraphrase the young Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg: hope lies in the blossoming of transformative actions everywhere.

Perhaps we should not view the COPs merely as annual (expensive and carbon-intensive exercises) that gather delegates and stakeholders from all nations of the world to cobble together a global action plan to combat climate change. The COPs are potential spaces for deep dialogue. They represent opportunities for building just and loving relationships that transcend North-South, class, racial, gender and other social divides that aggravate vulnerabilities to climate change.

Reflecting on the theme of love, the most recent WCC Assembly which brought together over 4000 church representatives from all parts of the world in Karlsruhe, Germany last September, emphasized the following in the statement titled Living Planet: Seeking a Just and Sustainable Global Community:

“Christ’s love calls us to deep solidarity and a quest for justice for those who have contributed to this emergency the least, yet suffer the most, physically, existentially, and ecologically, through a transformation of systems and lifestyles.”

Ultimately, the Christmas message is about love and justice. The season celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ, the Saviour, who “will bring forth justice to the nations” (Isaiah 42: 1) and whose greatest teaching is to love “the least” amongst us by doing justice (Matthew 25:40). Today, as pointed out in a 2013 WCC statement, the “[v]ictims of climate change are the new face of the poor, the widow and the stranger (Deut. 10:17-18).”

Living out the spirit of Christmas in the context of global climate change negotiations demands from wealthier nations and more privileged societies at least two actions: acknowledgment of their historical responsibility for causing climate change through implementing sharp reductions in emissions in line with science; and a radical sharing of resources – finance and technology – with countries and communities in the forefront of climate impacts.

Such reparatory and restorative deeds embody the true meaning of Christmas. May this Christmas shine a light on the path of climate redemption.

Athena Peralta is the Programme Executive for Economic and Ecological Justice at the World Council of Churches. She is a citizen of the Philippines and lives in Switzerland.

In recent days, landmark decisions for European climate action have been made in Brussels. Expansion of renewables, reform of emissions trading, phasing out of combustion engines and higher forest sinks – the EU’s Directorate General for Climate Action (DG Clima) is involved in negotiations for the new or revised laws. Until 2021, Artur Runge-Metzger was its chairman. He has shaped European climate action for many years – and continues to do so today.

The Paris climate protection agreement was an important milestone in his career: Artur Runge-Metzger helped launch the agreement at the time. Between the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and the follow-up agreement in 2015, however, a lot of valuable time passed in the fight against climate change, according to the long-time EU official. As a former director in the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Climate Action, his focus until 2021 was climate strategy and international climate negotiations.

As a fellow, Runge-Metzger has been supporting the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change since the beginning of June 2022. The agricultural economist helps develop political strategies for sustainable agriculture. He also sits on the board of the Agora Energiewende think tank. After all, the fight against climate change has not yet been won, which is why he wants to stay involved.

For the climate negotiations, he said, it was particularly important to consider the heterogeneity of the member states within the EU. Especially in terms of energy endowment and prosperity. Outside Europe’s borders, the spread is much wider: on the one hand, developing countries whose contribution to climate change is low. And on the other, emerging economies with rising emissions, such as Mexico and India. It is precisely these that need to be committed to international climate action first. “I think many of the emerging countries have woken up in the last ten years to what climate change would actually mean for them,” says the 64-year-old.

Artur Runge-Metzger sees the general direction of climate action in recent years as positive. However, he has rarely been satisfied with the speed of implementation and decision-making in recent decades. “There’s a common theme in politics: waiting for the full and final decision on one matter before making any further decisions at all.” The EU needs to show that climate change can be tackled. And that it won’t cause a regression in development or prosperity for the population. “We are not dependent on fossil fuels. That’s something where Europe has to lead the way.”

Whether Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will advance or retard the EU on climate remains to be seen. Runge-Metzger is optimistic that transformations will be accelerated due to high energy prices. More money is being put into expanding solar and switching to heat pumps, he said. However, he sees difficulties in the expansion of renewable energies. A lack of planning certainty and excessively long approval processes hinder the rapid switchover. Processes need to be streamlined and staffing gaps closed. Politicians must exert more pressure here.

Artur Runge-Metzger regularly goes running and cycling to clear his head between his many tasks. He also says that the city center of his hometown, Brussels, with its Art Nouveau and Gothic buildings from the Middle Ages, helps him to relax.

In addition to the Paris Climate Agreement and other projects for the EU, Artur Runge-Metzger was particularly interested in agricultural projects at the beginning of his career. He wrote his dissertation on decision-making by smallholder households in West Africa and the use of new technologies. The first job for the EU Commission was a project on agricultural development in Zimbabwe. “I learned a lot there, for example, about biodiversity conservation.” The fact that he dedicated his career to climate action came as an opportunity after that, he says. In the Directorate-General for International Partnerships, he was in charge of the Environment Division. At the time, his focus was on international negotiations with developing countries. Artur Runge-Metzger wants a strong, free and democratic Europe. “A Europe that doesn’t just stop at the borders of the EU, but goes beyond.” Kim Fischer

We feel the same way: Just before Christmas, we don’t want to be confronted with all the misery of global climate action again. That is why we searched for stories that would offer encouragement and spread a bit of hope. At first, we thought this would become a small section of this Climate.Table. Then it turned out – despite all the caution about greenwashing: There is indeed halfway positive news.

This is also thanks to the rather successful end of the Biodiversity Conference COP15 in Montreal. We analyze what impact COP15 will have on global climate action. And climate expert Hans-Otto Poertner explains what the conference accomplished, what is still missing, and what it means for Germany.

We have also compiled positive trends from the year 2022. And on top of that, the latest reports that just dropped on our desk: The rapid growth of electric buses worldwide, Indonesia’s surprising success in forest conservation, the incredible advance of renewables, and the negotiations for a new global plastics agreement.

This Christmas issue also comes with special selections for relaxed reading and listening: Journalistic articles that look at solutions surrounding the climate crisis. And a selection of podcasts to top it all off.

And if all the darkness drags you down as it does us, take comfort in the fact that the days are getting longer again. The light is coming back. And after taking a short breather next week, we will be back at the beginning of January with a comprehensive outlook on an exciting year 2023.

Have a restful time and a healthy New Year.

Mr. Poertner, how does the result of the biodiversity COP15 benefit the global climate?

Climate action and biodiversity conservation go hand in hand. Both crises, climate change and species extinction, threaten the very existence of humankind and many other species. Among other things, the natural environment is a tremendous carbon sink. Almost one-third of global man-made emissions can be traced back to agriculture and forestry. When we destroy forests, drain peatlands, and use fields so intensively that soils degrade, we release that carbon. Additionally, excessive factory farming causes massive emissions of nitrogen oxides and methane. And species-rich ecosystems are far more resilient to climate change than others.

Against this background, what is your assessment of the decisions made in Montreal?

The most prominent target agreed upon in Montreal states that 30 percent of the global land and 30 percent of the global ocean should each be protected by 2030. That makes sense because healthy ecosystems require a certain amount of land. But the 30 percent is a provisional average. Actually, such a protection quota needs to be specified and adjusted for each ecosystem individually.

Can you give an example?

Take the Amazon region with its extensive rainforest. It is of tremendous importance for biodiversity and at the same time a great carbon sink. The forest generates its own climate, especially the cycle of evaporation and precipitation, and thus sustains itself. However, for the water cycle to function, it is necessary to maintain more like 80 percent of the forest area. 30 percent is not enough.

In 2010, UN biodiversity targets were already adopted once. None of them were achieved. Why should it work this time?

It is always difficult to implement such targets. This is demonstrated not least with the 1.5-degree limit set by the Paris climate agreement. The IPCC repeatedly stated how important it is not to exceed this threshold. Nevertheless, the debate is now raging as to whether the target can even be met. This is a disaster. I think the same thing will happen with the biodiversity targets, partly because the agreement is not legally binding. We should have talked much more about implementation right from the start – in Paris as well as now in Montreal.

What would it look like to talk specifically about implementation?

It is very important, for example, that soils remain healthy and fertile, because they are the foundation of our existence. But our agriculture often does the opposite: Through the use of pesticides, the spreading of liquid manure and fertilizers, plowing, clearing and disturbance of the water balance as well as erosion, the soils dry out and degrade. That means, gradually, the organic material disappears from the soil. This harms the climate, and in extreme cases, the soil is ultimately unfit for agricultural use.

Should we use protected natural areas for economic purposes at all?

This is often unavoidable, because mankind populated just about every ecosystem on earth. In these cases, along with respect for biodiversity, we also need sustainable uses. In the first joint report of IPCC and IPBES, we proposed the concept of a mosaic approach for this purpose: Very well protected spaces must be connected by corridors and adjacent to sustainably used spaces. In this way, species can migrate, which is important for genetic exchange. We need such migration corridors all the more with climate change, because the climate zones are shifting and many animal and also plant species can only escape the less favorable living conditions by migrating.

What could such a mosaic look like in Germany?

Germany already has various types of protected areas. To some extent, however, this is also deceptive labeling: Just think of the intensively used Wadden Sea. Certainly, we could expand the intensively protected areas toward 30 percent, use them sustainably in some cases, and interconnect them, but in my opinion, implementation also involves challenges. For the 30 percent target now adopted, we would have to renaturalize our already degraded soils and ecosystems. And we would also have to be prepared to abandon or relocate infrastructure if necessary.

What does that mean, for example for road construction?

Germany should stop building new Autobahns. It is no longer appropriate and contradicts the 30 percent target set in Montreal. Strengthening the existing transport network should be sufficient. We need to reduce individual traffic and motorized traffic on our roads, not increase it further.

What must German policymakers do now to better protect biodiversity?

First of all, the different agencies will have to talk to each other. We need to think about protecting biodiversity as part of climate action, and vice versa, because the loss of biodiversity drives climate change, and vice versa. Then we have to rethink spatial planning in such a way that it becomes clear which ecosystems we want to protect in which regions, and also make a contribution to biodiversity protection at the international level. Subsidies must be redirected to serve sustainability. Agriculture must be transformed so that it is resilient to climate change, and in such a way that climate action and biodiversity benefit. And humans, of course, too.

By 2025, as part of the funding of 200 billion dollars per year, 20 billion dollars will flow from industrialized countries to poor countries each year. Do you think this distribution is fair?

I think that when it comes to conserving biodiversity, each country has an obligation to restore and protect its own natural areas. We can contribute by no longer buying products that require the clearing of rainforests. One example I have in mind is our meat consumption and our factory farming, which relies on soy from South America. In global climate policy, there is the idea of ‘Common But Differentiated Responsibilities’, which states that primarily industrialized countries are obliged to protect the climate and finance it. In biodiversity conservation, I do not think this is quite as justified. And in the meantime, emerging countries like China should also make their contribution to climate and climate policy. After all, around 60 percent of global emissions now come from the so-called developing countries. Economic development should also be linked exclusively to the use of renewables. This, too, serves both climate action and the conservation of biodiversity.

Many countries in the Global South demand money from industrialized countries to preserve their natural environment. Is this justified?

It goes without saying that we have to help countries that are not as well positioned materially. And of course, the countries with the most resources should be the first to do so. Ultimately, it is in the interest of the entire global community to preserve ecosystems, especially if they are large carbon sinks like the Amazon, for example. But the deciding factor is that the motivation for nature conservation must come from the countries themselves. They must wish to conserve their natural resources. If they don’t, then the most generous financial aid will be useless. The mentality of saying: We provide the biodiversity and others should pay for it because they have a special obligation to protect the climate because of their history – I don’t believe that is sustainable in the long term. Humanity is facing a planetary crisis, and it has to be tackled together as a global community. We are all in the same boat!

Hans-Otto Poertner is an ecologist, climate scientist and co-chair of IPCC Working Group II since 2015. He heads the Department of Integrative Ecophysiology at the Alfred Wegner Institute.

In mid-December, the energy companies Saudi Aramco and Total announced a gigantic project: With an investment of 11 billion dollars, the Saudi and French companies plan the complex “Amiral” on the east coast of Saudi Arabia, one of the largest petrochemical factories in the world. Here, 7,000 workers will soon produce, among other things, the basic materials for carbon fibers, lubricants, detergents and car tires. In parallel, the chemical company Ineos is constructing a new ethane cracker in the Belgian port of Antwerp for 3 billion dollars.

The petrochemical industry is expanding worldwide. At the same time, however, it becomes increasingly clear how crucial the industrial policy surrounding plastic is for climate action as well. After all, the substance is not only so dangerous to the environment as waste, that the UN Environment Program Unep warns about plastic and its significant and growing contribution to global emissions.

An international plastics treaty, which was launched in early December with initial meetings in Uruguay, is supposed to solve these problems. The next negotiations on the “Plastic Treaty” are also crucial to the Paris climate agreement and the remaining carbon budget.

In 2015, plastic was responsible for 4.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. The forecast: The share could triple by 2100. This means that by 2050, more than 10 percent of the remaining global carbon budget for plastic could be used up, according to calculations by the Center for International Environmental Law. Emissions occur in all seven steps of the life cycle of plastic:

90 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the plastics cycle are generated during the extraction and conversion of fossil raw materials. The so-called cracking process, where intermediate products for plastic production are created from crude oil, requires particularly large amounts of energy. Damage to local ecosystems and the global climate coincide at the latest during disposal.

Incineration generates the highest emissions and is expected to increase over the next few years. Production also continues to rise. Over 400 million tons of plastic are produced every year. Current projections assume that production will double in the next 20 years.

How could emissions from the plastics sector be reduced? This was modeled in a recent study in the Nature journal: If the conditions of

would be met, the sector could even become a net carbon sink by 2100.

So far, however, there has been no mention of this in the planned plastics treaty. If all goes well, such a legally binding treaty will be signed by UN member states in 2024 in order to tackle the global plastics problem. The first meeting of the relevant Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee, INC-1, took place at the beginning of December. About 2,000 delegates from 160 countries initially exchanged views in Uruguay on the scope and rules of the negotiations. Two conflict lines have already emerged:

Saudi Arabia and the United States spoke out right at the start in favor of a bottom-up agreement on plastic waste. A coalition of 40 negotiating parties, including the EU, host Uruguay and the United Arab Emirates, on the other hand, not only want to regulate waste, but start at the source – and reduce production to a sustainable level. They want to rely on a circular economy and bans on toxic chemicals. To this end, a global basis and internationally binding targets are to be formulated. The next round of negotiations, INC-2, is scheduled for May 2023 in Paris.

Crude oil and natural gas extracted during fracking are the basis for global plastics production. About 98 percent of disposable plastic products are still obtained from these fossil feedstocks. 12 percent of crude oil is converted into petrochemicals. The share is growing. But the main product from oil is and remains fossil fuels.

While discussions regarding the plastics treaty still focus on how decisions are to be made in the first place, the EU is already one step ahead. Since July 2021, the Single-Use Plastic Directive has been in force, which bans several products made of single-use plastic and is intended to initiate the transition to a circular economy. At the end of November, the EU Commission implemented two other key aspects of the Circular Economy Action Plan: A revision of the Packaging Directive to reduce packaging waste in EU countries by 15 percent by 2040 compared to 2018. And a non-binding guideline for bioplastics, which specifies under which circumstances bioplastics make ecological sense.

Indonesia seems to be succeeding in something that other countries find difficult: Over the past five years, deforestation has slowed sharply. Mikaela Weisse and Elisabeth Goldman of the World Resources Institute (WRI) analyzed the data released in spring and see it as a reason to celebrate.

For a long time, Indonesia was one of the countries where deforestation was a particularly big problem: Between 2002 and 2021, 10 million hectares of virgin forest were destroyed there – only Brazil had more in the same period. The main reason for this was the large amount of land required for the palm oil industry.

The background: More than half of the world’s tropical rainforest is located on the territory of Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia. How well the three countries manage to protect the forest is, therefore, particularly important for the global climate. According to WRI data, Indonesia currently still has around 84 million hectares of tropical virgin forest. In the DR Congo, the figure is around 99 million hectares, and in Brazil around 315 million hectares.

But although tropical forests are an important carbon sink, their destruction is progressing rapidly. Some 11.1 million hectares of forest were lost in the tropics in 2021, according to the Global Forest Watch (GFW) initiative. Of these, 3.75 million hectares were virgin forests. Their loss alone released 2.5 gigatons of carbon emissions, almost as much as India releases into the atmosphere in a year.

This makes the news of success from Indonesia all the more important for the global climate. Deforestation has not been stopped, but it has decreased more than elsewhere.

WRI sees two main reasons for this: Voluntary commitments by the industry and stricter policies.

To meet the Glasgow Declaration on Forest Conservation, deforestation rates worldwide must fall much faster than they have so far, say experts like Friedrich Bohn of the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) in Leipzig. For WRI experts Weisse and Goldman, Indonesia gives cause for hope. The rapidly declining deforestation rates are “a massive success that did not seem likely five years ago.”

One lesson is that industry commitments can work when combined with clear legal requirements from the government and strict controls. To be sure, the means to truly enforce forest conservation are often lacking, writes Frances Seymour, Distinguished Senior Fellow at WRI on Tropical Forests. “But the biggest limiting factor is the lack of political will.”

Brazil and Indonesia are “two of the most interesting departures” from the pattern of steady forest loss in the tropics, according to Seymour – Brazil in a negative way, Indonesia in a positive way. Both showed, in their own ways, how “government policy and corporate restraint” could work.

Electric buses have become a sales hit in recent years. In 2013, they accounted for just two percent of new bus sales. By 2021, almost every second bus sold was electric (45 percent). Their share of the global bus fleet has risen to 19 percent.

The trend in electric buses is one of the few silver linings in the “State of Climate Action 2022” analysis by climate NGOs and think tanks. Sales are going in the right direction to help the sector contribute to the 1.5-degree target. But they need to be stepped up further.

The Chinese electric bus boom is the result of subsidies, regulations, infrastructure construction, pilot programs, and an active industrial policy.

Since 2009, subsidies are being offered at the national and levels level:

Subsidies have since been reduced. They also served to boost the industry. After all, China’s government also promoted EVs for industrial policy reasons. The subsidies were therefore partly coupled to technical parameters such as energy consumption and battery range. In addition, financial aid was available for the development and research of electric buses. The Chinese company “Build your dreams” (BYD) is now the global market leader for electric buses and started production in Europe in 2017.

Many Chinese cities have also provided the necessary charging infrastructure. Bus depots and bus stops have been fitted with charging points.

Environmental regulations have also contributed to the success of electric buses. To reduce urban air pollution, the number of diesel vehicles and subsidies for internal combustion buses have been reduced. Since 2015, the number of conventional buses has fallen by an average of ten percent per year, according to GIZ.

Electric buses can yield major benefits for the climate. If they are operated with 100 percent renewable energies, “electric buses emit only 15 percent of the emissions of a diesel bus in the most favorable case,” as a study commissioned by the city of Zurich shows. Even buses with the largest batteries emit only 25 percent of the greenhouse gases of comparable diesel buses over their entire life cycle.

In China’s booming market, however, the climate benefit is much smaller. Coal-fired power still dominates the electricity mix too. EVs manufactured in China in 2022, calculated over their life cycle and a distance of 250,000 kilometers, will save 27 percent in carbon emissions compared to internal combustion vehicles, according to the think tank BloombergNEF (BNEF). The numbers will hardly be better for electric buses. However, the expansion of renewables in the People’s Republic will greatly improve the emission footprint of electric buses, according to BNEF analysts.

The EU member states have agreed on minimum targets for clean buses in 2021. Depending on the member state and economic strength, between August 2021 and 2025, 24 and 45 percent of all newly procured public buses must be “clean” – half of which must be emission-free. Vehicles that run on gas or synthetic fuels are also considered clean buses. Countries such as France and the Netherlands have set themselves more ambitious targets. They only want to buy zero-emissions buses after 2025.

Some lessons can be drawn from China’s electric bus success:

After two decades of rapid growth, renewables are poised to dominate the electricity market worldwide. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that in the next five years to 2027 alone, as much electricity capacity will be added from renewables worldwide as has been created in the last 20 years: around 2,400 gigawatts.

This is roughly equivalent to the total installed capacity of China – by far the largest producer of green electricity. Beyond renewables, according to the IEA’s medium scenario, there will be hardly any (10 percent) other additions to power plants.

According to the IEA figures, the solar industry, in particular, will expand strongly. In the five years to 2027, capacity is expected to practically triple from today’s level to around 1500 GW. In 2026, according to these estimates, photovoltaics will thus overtake the installed capacity of gas-fired power plants for the first time and coal one year later. Onshore wind capacity is expected to grow to 570 GW. The electricity harvest from offshore wind could increase six-fold to 600 TWh by 2030 compared to 2018.

The good news for the world’s climate is that the expansion of renewables is saving the atmosphere a lot of CO2: In 2021, the expansion of renewables alone accounted for around 220 million metric tons. The rapid expansion also means that China, the EU, and the US will reach their previously planned climate targets for 2030 earlier than previously announced.

Rapidly falling prices have now made solar and wind, in particular, competitive with fossil fuels in almost all parts of the world. Since 2010, for example, the cost of solar energy has fallen by 80 percent. The cost of batteries has also fallen by 97 percent over the past 30 years.

At the same time, government requirements and quotas for renewables are putting pressure. Climate action and air pollution control policies are important levers to pave the way for renewables.

But the current push for renewables has been triggered by Russia’s war of aggression on Ukraine, according to the IEA. “The first truly global energy crisis, triggered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, has created an unprecedented momentum for renewables,” says IEA chief Fatih Birol. The war highlighted how Europe, in particular, was exposed by its energy supply chains. And at the same time, he says, it drove up prices for fossil fuels to the point where renewables were paying off. By spring 2021, even green hydrogen produced with scarce green electricity in Germany was cheaper than hydrogen produced with gas.

The economic dynamics of renewables have long been massively underestimated by many experts. Even the IEA, today at the forefront of renewables advocates, has long doubted the green success story. From today’s perspective, even ambitious scenarios like Greenpeace’s 2015 “Energy Revolution” look tentative. The Ukraine war, in turn, shows how sudden political decisions can set in motion a dynamic that was previously considered unthinkable. Forecasts are only as good as the world doesn’t move in completely new directions.

Finally, even amid the general enthusiasm about the triumph of renewables, important questions remain unanswered:

The US Congress proposes the government in Washington provide one billion dollars of climate money for poor countries, reports the New York Times. The sum is significantly below President Joe Biden’s pledge, who said in 2024 the United States would provide 11.4 billion dollars “to ensure developing nations can transition to clean energy and adapt to a warming planet.”

According to the report, members of Congress are expected to vote this week on the proposal, which is part of a larger funding package totaling 1.7 trillion dollars. Democrats originally had wanted to earmark 3.4 billion for international climate programs as part of the package. Republicans rejected this.

“The Republicans are poised to assume control of the House in January,” the newspaper writes, “further dimming prospects for additional climate funds for at least the next two years.” Congress has now cut the president’s climate aid request for the second year in a row, the report added. Activists commented that the inability of Biden’s administration to meet its own goals hurts US credibility in the world. ae

The use of renewables prevented greenhouse gas emissions totaling 217 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in Germany in 2021. This is roughly equivalent to the amount of greenhouse gases emitted annually by Austria, Switzerland, Ireland and Portugal combined. This is according to the emissions balance of renewables recently published by the German Federal Environment Agency (UBA).

“The results of the emissions balance show that the expansion of renewable energies contributes significantly to achieving the climate action goals in Germany,” the authority writes. In all consumption sectors, “fossil fuels are increasingly being replaced by renewable energies.”

CO2 avoidance comes

The calculations not only took into account the directly avoided emissions, but also the emissions from the upstream chain, such as the installation of plants or the procurement of fuels, according to UBA. Elaborate simulations also showed that about 80 percent of the carbon reduction was achieved by replacing fossil-fuel power plants in Germany, with only about 18 percent at foreign power plants.

The statistics also show that the use of renewables in the electricity sector is most effective in reducing carbon emissions. This is because although electricity accounted for only half of renewable electricity in 2021, at 233 TWh, it was responsible for 76 percent of carbon reductions. Electricity, heat and transport, on the other hand, required the other half of green electricity but delivered only 24 percent of the climate protection effect.

UBA’s latest data is for 2021, the first year in which less carbon was avoided by renewables after steady growth in the previous ten years. The reason, according to UBA, was less favorable weather conditions for the solar and wind sectors. bpo

Why did the concentration of methane in the atmosphere increase by 50 percent between 2019 and 2020, even though the economy in large parts of the world came to a virtual standstill due to the Covid pandemic? That has long puzzled researchers around the world. Now, a team of scientists has discovered clues pointing to solving the question.

In a study published in the Nature journal, they wrote that just under half of the increase, about 47 percent (with a variation of plus/minus 16 percent), was due to higher natural emissions, primarily from wetlands. The other half, around 53 percent (range of variation plus/minus 10 percent), was due to lower hydroxyl concentrations in the troposphere.

Hydroxyl (OH) reacts with gases in the atmosphere, including methane. This produces soluble compounds that can then be washed out of the atmosphere, so to speak. OH is therefore also known as the atmosphere’s cleaning agent. In 2020, the OH concentration in the troposphere decreased by about 1.6 percent compared to 2019, the researchers write.

Hydroxyl can form, among other things, through reaction with nitrogen oxide in the atmosphere – and during the pandemic, anthropogenic nitrogen oxide emissions fell significantly. According to the study, this was a major reason for the lower OH concentration. Nitrogen emissions would therefore have to be taken into account in the implementation of the Global Methane Pledge.

The results also showed that methane emissions from wetlands are sensitive to climate change and could amplify themselves in the future, the researchers write. ae

This year, it could be said that Christmas arrived a bit early with the ground-breaking agreement, concluded at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, to establish a global fund to help developing countries and deal with the wide range of losses and damages caused by accelerating climate change. Small islands in the Pacific and the Caribbean, which emit less than one percent of greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, as well as larger climate-vulnerable developing nations like the Philippines, welcomed the agreement with joy and relief.

Confronted with rising sea levels, warming oceans and increasingly destructive storms leading to the irreparable damage and loss of coastal and farmland, coral reefs, homes and the resting places of ancestors, they had called for such a facility for nearly thirty years. These calls were largely unheeded by the powerful till now.

Bearing witness and often acting as first responders to climate disasters, churches have supported these cries for reparations, recognizing at the same time that non-economic losses and damages, such as the forfeiture of human lives and the erosion of ancient cultures and ways of living, cannot be valued nor be truly recompensed in monetary terms.

The World Council of Churches (WCC) – has released a statement ahead of COP27 that urged for a “loss and damage financing facility to compensate communities and countries on the frontline of climate impacts and to support their efforts in building resilience” – was among those who celebrated the COP27 decision to provide vital financial support to those suffering from climate change.

The creation of the fund is a testament not only to the unity of developing country governments, but also to churches, faith-based groups and other civil society organizations coming together to monitor and reshape global climate negotiations – all of whom worked relentlessly and concertedly to eventually overcome opposition from wealthier, high-polluting countries such as the United States and those from the European Union.

The new loss and damage fund offers a kernel of hope. But it is a fragile hope. Currently, the fund does not hold any money and is yet to be operationalized. Plenty of work needs to be put in to ensure that it is adequately resourced and meets the needs of communities and women and children on the ground.

The biggest questions are: How much is needed? What mechanisms should be developed so as to reach those most affected? And, most contentious of all, who will pay for it – even though, in response to the latter question, the 1992 UN Earth Summit held in Rio de Janeiro which created the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change had already enshrined the Polluters Pay Principle. These thorny issues around implementation are expected to be threshed out at the next COP.

Taken as a whole, the decisions reached at Sharm El-Sheikh remain far from commensurate to the sheer enormity of the existential challenge of climate change. The latest scientific reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warn us that the window of opportunity for limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C and preventing the most catastrophic consequences of climate change is closing rapidly.

Greenhouse gas emissions must start falling by 2025, be halved by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050. But interests in protecting corporate profit margins and meeting national growth targets prevailed such that COP27 failed to deliver stronger language on phasing out fossil fuels nor the necessary cuts in emissions, putting the planet on a calamitous trajectory of 2.4-2.8 C warming by the end of the century.

Yet in spite of these failures, Christmas stirs hope in many of us – the hope of good news made flesh, of co-creating more equitable and sustainable economic systems and societies underpinned by values of solidarity and compassion, of keeping alive the Paris goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 C and securing a chance for a liveable future for our children and grandchildren.

This hope is evident in the few but courageous women leaders in the COPs who have consistently spoken truth to power. It is tangible in the young climate activists who have taken to the COPs, the courts and the streets to hold their governments as well as corporations to account for their roles in causing or aggravating climate change. This hope is palpable in movements of farmers and Indigenous Peoples who are challenging unjust and unsustainable systems of production and consumption that are at the root of the climate crisis by practicing community-based agro-ecology and non-marketized ways of exchanging products and services.

And it is made visible by churches that not only conduct prophetic advocacy at the COPs but also seek to “walk the talk” by practicing climate-responsible finance and contributing to efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change in their daily operations. In other words and to paraphrase the young Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg: hope lies in the blossoming of transformative actions everywhere.

Perhaps we should not view the COPs merely as annual (expensive and carbon-intensive exercises) that gather delegates and stakeholders from all nations of the world to cobble together a global action plan to combat climate change. The COPs are potential spaces for deep dialogue. They represent opportunities for building just and loving relationships that transcend North-South, class, racial, gender and other social divides that aggravate vulnerabilities to climate change.

Reflecting on the theme of love, the most recent WCC Assembly which brought together over 4000 church representatives from all parts of the world in Karlsruhe, Germany last September, emphasized the following in the statement titled Living Planet: Seeking a Just and Sustainable Global Community:

“Christ’s love calls us to deep solidarity and a quest for justice for those who have contributed to this emergency the least, yet suffer the most, physically, existentially, and ecologically, through a transformation of systems and lifestyles.”

Ultimately, the Christmas message is about love and justice. The season celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ, the Saviour, who “will bring forth justice to the nations” (Isaiah 42: 1) and whose greatest teaching is to love “the least” amongst us by doing justice (Matthew 25:40). Today, as pointed out in a 2013 WCC statement, the “[v]ictims of climate change are the new face of the poor, the widow and the stranger (Deut. 10:17-18).”

Living out the spirit of Christmas in the context of global climate change negotiations demands from wealthier nations and more privileged societies at least two actions: acknowledgment of their historical responsibility for causing climate change through implementing sharp reductions in emissions in line with science; and a radical sharing of resources – finance and technology – with countries and communities in the forefront of climate impacts.

Such reparatory and restorative deeds embody the true meaning of Christmas. May this Christmas shine a light on the path of climate redemption.

Athena Peralta is the Programme Executive for Economic and Ecological Justice at the World Council of Churches. She is a citizen of the Philippines and lives in Switzerland.

In recent days, landmark decisions for European climate action have been made in Brussels. Expansion of renewables, reform of emissions trading, phasing out of combustion engines and higher forest sinks – the EU’s Directorate General for Climate Action (DG Clima) is involved in negotiations for the new or revised laws. Until 2021, Artur Runge-Metzger was its chairman. He has shaped European climate action for many years – and continues to do so today.

The Paris climate protection agreement was an important milestone in his career: Artur Runge-Metzger helped launch the agreement at the time. Between the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and the follow-up agreement in 2015, however, a lot of valuable time passed in the fight against climate change, according to the long-time EU official. As a former director in the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Climate Action, his focus until 2021 was climate strategy and international climate negotiations.

As a fellow, Runge-Metzger has been supporting the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change since the beginning of June 2022. The agricultural economist helps develop political strategies for sustainable agriculture. He also sits on the board of the Agora Energiewende think tank. After all, the fight against climate change has not yet been won, which is why he wants to stay involved.

For the climate negotiations, he said, it was particularly important to consider the heterogeneity of the member states within the EU. Especially in terms of energy endowment and prosperity. Outside Europe’s borders, the spread is much wider: on the one hand, developing countries whose contribution to climate change is low. And on the other, emerging economies with rising emissions, such as Mexico and India. It is precisely these that need to be committed to international climate action first. “I think many of the emerging countries have woken up in the last ten years to what climate change would actually mean for them,” says the 64-year-old.

Artur Runge-Metzger sees the general direction of climate action in recent years as positive. However, he has rarely been satisfied with the speed of implementation and decision-making in recent decades. “There’s a common theme in politics: waiting for the full and final decision on one matter before making any further decisions at all.” The EU needs to show that climate change can be tackled. And that it won’t cause a regression in development or prosperity for the population. “We are not dependent on fossil fuels. That’s something where Europe has to lead the way.”

Whether Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will advance or retard the EU on climate remains to be seen. Runge-Metzger is optimistic that transformations will be accelerated due to high energy prices. More money is being put into expanding solar and switching to heat pumps, he said. However, he sees difficulties in the expansion of renewable energies. A lack of planning certainty and excessively long approval processes hinder the rapid switchover. Processes need to be streamlined and staffing gaps closed. Politicians must exert more pressure here.

Artur Runge-Metzger regularly goes running and cycling to clear his head between his many tasks. He also says that the city center of his hometown, Brussels, with its Art Nouveau and Gothic buildings from the Middle Ages, helps him to relax.

In addition to the Paris Climate Agreement and other projects for the EU, Artur Runge-Metzger was particularly interested in agricultural projects at the beginning of his career. He wrote his dissertation on decision-making by smallholder households in West Africa and the use of new technologies. The first job for the EU Commission was a project on agricultural development in Zimbabwe. “I learned a lot there, for example, about biodiversity conservation.” The fact that he dedicated his career to climate action came as an opportunity after that, he says. In the Directorate-General for International Partnerships, he was in charge of the Environment Division. At the time, his focus was on international negotiations with developing countries. Artur Runge-Metzger wants a strong, free and democratic Europe. “A Europe that doesn’t just stop at the borders of the EU, but goes beyond.” Kim Fischer