At the end of last week, the Bundesrat approved the controversial amendment to the Climate Change Act (KSG), cementing its weakening despite all criticism and protests. Alexandra Endres and Malte Kreutzfeldt analyze for you why the recent climate rulings from Berlin remain relevant even after the weakening of the KSG. Additionally, you’ll read why climate activists are now appealing to the Federal President not to sign the law.

While Germany is weakening its climate action efforts, the EU is struggling to implement stronger climate action mandates in agriculture. So far, the industry has always successfully resisted. Lukas Scheid and Julia Dahm discuss what a CO2 price in the agricultural sector could look like. Looking at Europe, we also explain why carbon leakage remains a problem and what impact US tariffs on the battery industry could have.

Today, we also report on why necessary adjustments are hardly affordable for some population groups in Germany. In our viewpoint, experts Nicolás Aguila and Joscha Wullweber call for a green monetary policy from central banks.

Following recent rulings by the Higher Administrative Court (OVG) of Berlin-Brandenburg, experts believe that the federal government will need to tighten its climate policy. This remains true even with the recently passed amendment to the Climate Change Act, as key criticisms from the court remain unaddressed. Plaintiff’s attorney Remo Klinger cannot imagine the government ignoring the ruling; what would happen in that case is currently unclear.

On Thursday, the German Environmental Aid (DUH) won two lawsuits: In the first, the organization demanded a “sufficient climate action program” to avoid exceeding the sector-specific targets in energy, industry, buildings, agriculture, and transportation as mandated by the previous version of the Climate Change Act. In the second, they demanded a similar “sufficient climate action program” to achieve the targets in the land use sector (LULUCF), which involves natural sinks like forests, moors, meadows and pastures that annually absorb and store a specific amount of CO2 to offset harmful emissions.

The court found that the German government’s 2023 climate action program did not meet legal requirements in both cases. According to its ruling, the government is now obliged to supplement the climate action program so that

Additionally, the court stated that “the 2023 climate action program suffers from methodological deficiencies and is based on unrealistic assumptions in some parts.”

The precise legal consequences of the ruling remain unclear as the written judgment is yet to be released. It is generally expected that the federal government will appeal – as it did with an earlier OVG ruling last year that required immediate climate action plans for the building and transportation sectors.

A spokesperson for the BMWK left this question open on Friday. “We need to carefully examine and evaluate this ruling and its reasoning,” she stated. In the likely event of an appeal, the case would be heard by the Federal Administrative Court, and it would take some time before a final judgment is issued. Only then would the government be required to act.

By then, the new version of the Climate Change Act, which passed the Bundesrat on Friday, would already be in force and likely applied, according to Niklas Täuber, an environmental lawyer at FU Berlin and a research associate at the Competence Network “Future Challenges of Environmental Law”. “It is likely that a judgment will be based on the amended law,” Täuber told Table.Briefings.

Environmental lawyer Remo Klinger, who represented the DUH in the case, agrees. “I assume that in the appeal, the new law will apply because it concerns a program for the future,” Klinger told Table.Briefings. However, much would not change, as two of the three key grounds for the ruling are unaffected by the amendment. “The LULUCF target and the overall goal for 2030 remain unchanged.”

Therefore, the new law would only impact the failure to meet sector-specific targets. This point would become irrelevant, as the amendment removes their legal bindingness. However, the overarching emission target of a 65 percent reduction by 2030 and the LULUCF targets, which are clearly being missed, remain significant: Instead of storing 40 million tons of CO2 annually as stipulated by law, land-use changes are projected to release greenhouse gases after 2040.

In the proceedings, it will be crucial how the Federal Administrative Court evaluates the government’s emission projections for the years leading up to 2030. In its 2023 projection report, the government admitted a gap of about 200 million tons of CO2 equivalents. However, new projections from April 2024 suggest that achieving the overall target is possible. The OVG did not consider these, criticizing in its oral ruling that these did not account for the impact of the Federal Constitutional Court’s ruling on the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF) – i.e., the current projection report is too optimistic about the expected emission reductions.

The Expert Council for Climate Issues, appointed by the government, is currently examining the accuracy of these projections. However, Brigitte Knopf, the council’s deputy chair, stated during the OVG hearing that about half of the measures in the climate action program are financial support programs and the Constitutional Court ruling has now deprived them of funds. Therefore, the effectiveness of the government’s planned climate action measures is likely to be lower than previously assumed.

Regarding what needs to be done to comply with the ruling, environmental groups have clear ideas. To achieve the overall target by 2030, especially the transportation sector must take further action, according to DUH Co-Chief Resch. The responsible minister, Volker Wissing, must no longer “refuse measures like a speed limit on highways or stopping subsidies for environmentally harmful company cars.” Additionally, more funds are needed to meet the LULUCF targets. “Given the upcoming budget negotiations, we urge the government to finally eliminate climate- and environmentally harmful subsidies and to exclude important funding instruments like the Natural Climate Action Program from further cuts,” says Florian Schöne, managing director of the environmental umbrella organization DNR.

The recent rulings have also sparked discussions about what happens if the government does not comply with the court’s demand to tighten climate targets. Environmental lawyer Täuber believes that little will change without the necessary political will. “If a citizen does not comply with a court ruling, the state can enforce it with force if necessary,” says Täuber. “But if a court ruling obliges a state actor, such as the government in this case, and it does not comply, there are no comparable enforcement mechanisms.”

DUH attorney Klinger finds the question of what happens if the government ignores the ruling absurd. “As long as we do not have a populist government, I think this discussion is nonsense,” he says. “I naturally assume that the government will comply with supreme court decisions.”

What can happen if authorities do not comply was made clear a few years ago when the state of Bavaria refused to implement a ruling that required effective air pollution control through diesel driving bans. At that time, fines were initially imposed. However, this measure is “ultimately inconsequential,” as it merely shifts public funds “from one pot to another,” Täuber says.

A more severe measure, such as coercive detention against the responsible officials, is “difficult to enforce, if legally permissible at all, and certainly not politically feasible“. DUH lawyer Klinger does not want to speculate on this possibility, but he is well acquainted with the details: In the DUH’s case against the state of Bavaria, he was the one who had the legal feasibility of coercive detention examined and later applied for it.

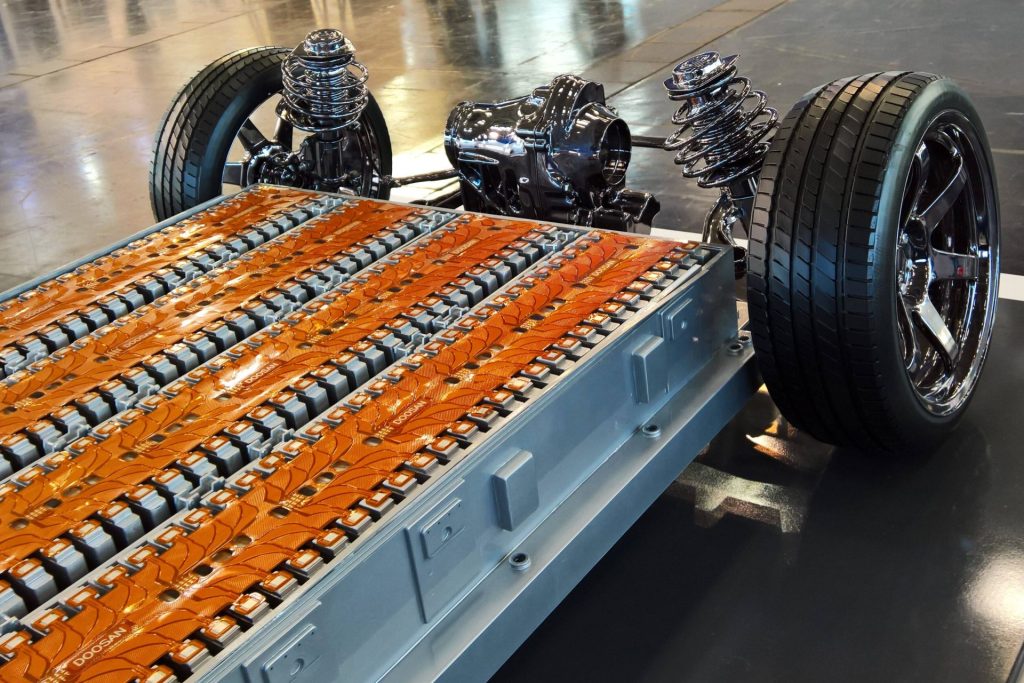

The US tariff increase on Chinese electric car batteries will likely shift Chinese exports to Europe. Last week, President Biden announced additional tariffs on Chinese electric car batteries, battery parts, electric vehicles and solar panels to counteract the flood of cheap Chinese overcapacities.

Tariffs on electric car batteries have tripled to 25 percent. In 2026, tariffs on lithium-ion batteries used in other applications, such as energy storage systems, will also be increased. “If Europe does not follow suit with similar tariffs, Chinese batteries will become even cheaper for Europe because the overcapacities have to go somewhere,” says Dirk Uwe Sauer, a professor at RWTH Aachen, to Table.Briefings.

For European manufacturers, this means even more competition. “For the efforts of ACC, Northvolt and VW/PowerCo to produce their own batteries in Europe, this will be a particular burden,” says Sauer. The start-up of new factories will coincide with a period of absolute price competition, making it especially difficult for newcomers.

The battery market already has massive overcapacity. China alone has production capacities sufficient to meet global demand. The country dominates all steps of the supply chain. Experts warn that overcapacity could continue to rise as companies in Europe, the USA, and China continue to invest billions.

By the end of 2025, there could be 7.9 terawatt-hours of global battery production capacity, according to BloombergNEF (BNEF) analysts. However, demand will only be 1.6 terawatt-hours. Even if many of these new factories do not move beyond the planning stage, “the market is heading for an even greater oversupply,” write BNEF experts.

Other experts also believe that the new US tariffs “could drive Chinese batteries to Europe,” as battery expert Andy Leyland of consultancy Benchmark Minerals wrote on Twitter. Earlier this year, Leyland was more optimistic about Western battery manufacturers. “The order books of [Western] companies like Northvolt, LG Chem, and Panasonic are well filled for years,” he wrote.

According to him, China is “in a problematic situation”. The country must export its overcapacities in “Chinese electric cars, electronics and batteries for energy storage,” says Leyland. The market for energy storage systems will experience a significant additional supply of batteries to complement solar and wind storage. “This is a nice boost for the energy transition,” Leyland believes.

Batteries are considered one of the most important future technologies. They are seen as the “new oil” and a “master key” to accelerating the transformation of the energy and transportation systems. Countries leading in the battery sector could achieve “great industrial gains” in the future, according to a recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA). Currently, China is still the leader in the battery industry. Europe, though still very dependent on China, is catching up thanks to government support and large investments.

Batteries are seen as a key technology for several reasons:

Currently, China dominates large parts of the battery supply chain:

The USA and Europe, however, are catching up and have established numerous factories in recent years. Many more are in the planning stage. According to the IEA, the USA and Europe could meet their battery demand with domestic production by 2030. According to the NGO Transport and Environment (T&E), this could be possible by 2026.

For critical components like cathodes and anodes, however, China’s dominance will likely continue, according to the IEA. T&E also criticizes that there are only two cathode factories in Europe, despite the continent’s potential to meet more than half of the demand through domestic production.

China’s market dominance is due to a long-term industrial policy and subsidies for battery manufacturers. Manufacturers in China are among the technological leaders and can produce large quantities at low prices due to lower energy and labor costs compared to Europe.

The success of European manufacturers in the market will also depend on politics. Europe has significant competitive disadvantages. In Europe, “both the capital expenditures (CAPEX) and operating costs (OPEX) for building and operating battery cell, component, and material factories” are particularly high, writes Transport and Environment. If Europe offered the same government support as the USA under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the annual operating costs for battery factories alone would amount to 2.6 billion euros, the organization calculates.

However, there are other ways to support the industry: “Environmental, social, and governance standards will be crucial in determining market winners and losers,” writes the IEA. T&E calls for a secure investment environment and adherence to phasing out internal combustion engines. Additionally, investment aids at the EU level and “stronger ‘Made in EU‘ requirements for public procurement, subsidies, and EU grants and loans for EV and battery manufacturers” are needed.

According to the European Commission, agriculture accounts for more than ten percent of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions. The sector’s emissions have not decreased in the past two decades. Addressing these emissions in light of the EU’s climate goals could become a significant issue in the upcoming legislative period.

The main controversy is whether and how to include agriculture in the mandatory EU emissions trading system. Currently, agriculture is the only climate-relevant sector whose emissions are not subject to pricing. However, this topic is divisive, even within the European Commission.

On one side is the Directorate-General for Climate Action (CLIMA). Last year, it sparked the debate by commissioning a study on CO2 pricing in agriculture and its value chain. The study is also intended to contribute to the political discussion surrounding the 2040 climate goal, according to DG CLIMA upon its publication in November.

The Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (AGRI) takes a more cautious approach. AGRI Director-General Wolfgang Burtscher recently acknowledged at an event in Brussels that the pressure to reduce agricultural emissions is high and that the debate on CO2 pricing is gaining momentum. However, he argued that emissions could also be reduced through incremental measures incentivized by the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

So far, this has not worked: A 2021 report by the European Court of Auditors concluded that despite substantial funding, the CAP has hardly contributed to emission reductions. The debate is also likely to be influenced by the political climate around farmer protests. In February, the Commission significantly softened the section on agriculture in its recommendation for the 2040 climate goal compared to earlier drafts. The idea of a mandatory emissions trading system is unpopular in the industry.

The German Farmers’ Association (DBV) argues in a position paper that inclusion in the statutory emissions trading system is “not feasible” due to the structure of agriculture, the nature of emissions based on natural processes and administrative hurdles. Instead, the industry favors voluntary compensation for CO2 sinks and positive financial incentives for emission reductions. Similarly, Peter Liese, MEP and rapporteur on emissions trading, wants to emphasize the benefits for farmers.

Nonetheless, DG CLIMA is not giving up: It has commissioned a new study to be developed starting mid-year. The results could be ready in time for the plans for the 2040 climate goal to be translated into law after the election, including an impact assessment for a CO2 price in agriculture.

The debate on how to price agricultural emissions to apply the polluter-pays principle to agriculture, as demanded by the European Court of Auditors, is in full swing. One option would be a CO2 tax – the most direct form of CO2 pricing. However, this is considered difficult to implement due to national sovereignty over tax matters.

It is conceivable to include agriculture in the existing EU emissions trading system for industrial plants. The market and structure already exist and legal implementation would be relatively straightforward. However, the agricultural sector consists of over nine million farms with emissions of around 400 million tons of CO2 equivalents. The impact of their inclusion on price stability in the ETS would be difficult to calculate and potentially counterproductive for climate action.

The incentive for emission reductions in sectors already covered by the ETS could decrease due to falling prices, warns Hugh McDonald, a fellow at the Ecologic Institute and one of the authors of the first study on CO2 pricing in agriculture for DG CLIMA. “Looking ahead to 2050 maybe it makes sense to have one price to rule them all. But I think what we’re talking about at the moment is the next 10 to 15 years.”

Additionally, there should be benefits for farmers and landowners, says McDonald. “Otherwise, it will be difficult to enforce this policy.” He refers to the reward for carbon dioxide removal through land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF). One possibility would be to link the pricing of emitted greenhouse gases with compensation for sequestered emissions.

Such a model would also address the demands of prominent economists and the European Court of Auditors to reward farmers for CO2 removal. And it seems Brussels is already considering this. The orders for the development of the two studies on an agricultural ETS came from the department within DG CLIMA responsible for CO2 removals, rather than the emissions trading experts.

The question is whether the two activities – emitting and removing – can be linked in a single system or need to be separated. McDonald believes that a separate system is more practical in the medium term. This way, there can be two distinct goals – one for emission reductions and one for CO2 removals. “The risk with a combined system is that it could be cheaper for farmers to buy low-quality removal certificates instead of reducing their own emissions.”

However, McDonald warns against focusing solely on an agricultural ETS. There are other political measures that are simpler and quicker to implement and thus more effective for reducing agricultural emissions. The economist still sees great potential in redesigning the 60 billion euros CAP subsidies as a climate action instrument. “Making changes in the Common Agricultural Policy is politically very difficult, but on a technical level we’ve already got a structure and all this money flowing into the scheme.”

A new system like an ETS, including compensation for CO2 removals, would have to compete with the vast sums from the CAP. Therefore, a redesign of the CAP would be inevitable if agricultural emissions are to be reduced, believes McDonald. This is also a task for the next legislative period: the Commission is expected to present initial ideas next year on what the CAP should look like after the current funding period ends. The current CAP runs until 2027 but could be extended.

Appeals from environmental organizations and CDU climate expert Andreas Jung were in vain: Following the Bundestag, the Bundesrat also approved the controversial amendment to the Climate Change Act (KSG). During the session on Friday, the state representatives refrained from calling for a mediation committee, which several environmental organizations had demanded beforehand.

Additionally, a formal error in the text of the law was discovered last week. The attempt to correct this without another vote was thwarted by the opposition from the Union. They had demanded that the vote in the Bundesrat be postponed and that the law be reconsidered in the Bundestag. Instead, the flawed law was adopted without debate in the Bundesrat. The error is to be corrected later in a separate procedure.

The final hurdle is now the required signature of the law by the Federal President. Normally, this is a mere formality; however, in this case, the German Environmental Aid (DUH) hopes that Frank-Walter Steinmeier will not sign the law due to the error and constitutional concerns.

In a letter to the federal president, DUH lawyer Remo Klinger details why, in his view, the amendment contradicts the climate ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court from 2021, which he helped secure. The letter concludes by stating, “Since the amendment is unconstitutional for the reasons mentioned here, we kindly ask you, Mr. Federal President, not to sign the law.” mkr

The use of “clean hydrogen” could lower the costs of worldwide decarbonization by 15 to 22 percent, as concluded by a recent study. Researchers achieved this result by further developing the Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM) and analyzing the costs and benefits of deploying hydrogen in 24 scenarios aiming for a climate-neutral energy system by 2050. These scenarios vary in assumptions regarding socio-economic development as well as the availability of hydrogen, batteries, and net-negative technologies (DACCS and BECCS).

Due to costly technical barriers, hydrogen is projected to only provide three to nine percent of the global energy supply by 2050. However, achieving climate neutrality in scenarios with hydrogen is more cost-effective than in scenarios without it. Particularly in sectors challenging to electrify, such as international shipping or heavy-duty trucking, its deployment leads to cost savings.

For researchers, “clean hydrogen” includes not only green hydrogen from renewables but also so-called “blue hydrogen”, where emissions are captured through CCS during production. However, many experts view this skeptically. Johan Lilliestam, Professor of Sustainability Transition Policy at Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg, comments, “From a climate perspective, blue hydrogen with CCS is not a reasonable solution.” Firstly, it cannot capture all CO2 emissions during production, and secondly, there are still issues with emissions from pipeline leaks. kul

To achieve the EU’s long-term climate goals, a carbon price is deemed more effective than regulatory climate action measures and subsidies guided by climate criteria. This is the outcome of a report by the Centre for European Policy (CEP). Emissions trading is considered environmentally effective, economically cost-efficient, socially acceptable, and politically stable even during crises.

Hence, the experts also recommend expanding the existing EU Emissions Trading System (ETS 1) for energy and industry to include the agricultural and land-use sectors (LULUCF). Additionally, ETS 1 should be merged with ETS 2 for building heating and transportation. While having two parallel systems might be sensible in the short term, it weakens incentives for emission reductions in the medium to long term due to different reduction paths and resulting carbon prices.

Moreover, the EU’s climate policy still lacks an effective and comprehensive system to prevent carbon leakage. The Fit-for-55 package does not ensure equal competitive conditions for European companies. European producers competing internationally will face a carbon price, while their international counterparts mostly will not. Therefore, resolving the carbon leakage dilemma should be “urgently placed at the top of the EU agenda for 2024-2029,” as advocated by CEP experts.

Unilateral trade measures like the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) are considered only the “second-best” solution and may even prove counterproductive. CBAM could be circumvented by importing processed products not covered by CBAM instead of raw materials subject to it. Instead, the EU should pursue multilateral solutions, such as international climate clubs or joint emissions trading systems with third countries. luk

According to the Polish government, sanctions on the import of fossil Russian energy carriers into the EU should be implemented more quickly and effectively. This was stated by Urszula Zielińska, State Secretary from the Polish Ministry of Climate and Environment, on Friday at the German-Polish Energy Transition Forum at the Foreign Office in Berlin.

In particular, the green State Secretary criticized that the import of processed oil products such as diesel from Russian crude oil through third countries like India and Turkey is still possible. “Under these circumstances, the EU’s climate policy, with the shift away from coal, natural gas and oil towards clean energy sources, has taken on a new dimension,” said the deputy of Minister Paulina Hennig-Kloska. Zielińska accused Russia of conducting disinformation campaigns on climate policy in Poland, Germany, and other EU countries.

One topic for cooperation mentioned by Udo Philipp, State Secretary from the German Ministry of Economic Affairs, is the construction of offshore wind farms. Poland has more experience in building foundations than Germany: “Through our coordination, we could also use infrastructure such as ports and ships more efficiently.” Poland also has potentials for hydrogen storage and demand flexibility. Regarding the latter point, the BMWK has already launched an initiative with France to better integrate renewable energy generation peaks into the European electricity market. ber

The Climate Neutrality Foundation is working towards assessing the social conditions in Germany concerning the climate transition and the consequences for selecting suitable policy instruments. Initial results were presented last week. They are based on 14 data categories (including age, income, property ownership) and 20 formed clusters.

Additionally, 16 different types of individuals (“personas”) were identified. The group classified as the “heat pump generation,” comprising three percent of the population, has built or purchased a house on the outskirts of a small town in the past 20 years. Their energy consumption is already low, and significant investments for the heat transition are not necessary. Due to their “good financial situation” with purchasing power, they have already begun transitioning to electric mobility.

The situation is entirely different for the “precarious rebuilding generation“, representing 15 percent of the population. On average, these individuals are 79 years old and reside in often very old single-family homes. Even with significant support programs, they cannot make their homes climate neutral on their own. Neither electric cars nor public transport are realistic alternatives for climate-neutral mobility for these individuals.

For citizens with poor adaptability, an expansion of public services, such as the expansion of district heating networks and public transportation, is necessary. Other important measures include:

There is a significant disparity in the adaptability of citizens between urban and rural areas, as well as between cities themselves (see chart). Accordingly, the regional needs for climate and mobility transition vary greatly. cd

Faced with the highest inflation in over four decades, the central banks of major economies have gradually increased interest rates and initiated a policy of quantitative tightening (QT) since 2022.

In our recent article, we argue that interest rate hikes do not address the environmental causes of inflation and can even exacerbate long-term inflation by making necessary investments for the green transition more expensive and thus delaying them.

Instead, a monetary policy framework is needed that can address both inflation and the environmental crisis. Fabio Panetta, the current Governor of the Bank of Italy and former ECB Board member, referred to such approaches as “greener and cheaper“.

Interest rate increases have a disproportionately high impact on sustainable investments compared to carbon-intensive investments. Sustainable investments are more capital-intensive, require greater upfront investment and need more debt financing. As a result, they are more sensitive to cost increases (especially borrowing costs) than their carbon-intensive competitors.

In addition, QT has also significantly reduced the potential of quantitative easing (QE) to support green investments through easier financing and lower borrowing costs. Higher interest rates can therefore delay the green transition by increasing the cost of sustainable investment. This policy is, therefore, not only short-sighted in terms of climate policy but also worsens the prospects for price stability.

Empirical studies show that the environmental crisis is also a source of inflation. ECB Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel names three types of shocks that can have an impact on prices:

The current macroeconomic environment requires a monetary policy approach that addresses the climate and environmental crisis while combating inflation. This is not only necessary for economic and environmental reasons, but is also in line with the main mandate of central banks.

Numerous tools are discussed in the literature for this purpose, including asset purchases, lending policies and financial regulations. A particularly promising approach is direct credit allocation, which was common in advanced economies in the past and is still used in some developing countries. Here, central banks steer credit allocation in a green direction. A variety of tools can be used for this purpose, benefiting banks, businesses, and governments, including:

Additionally, credit steering policies have been successfully used in the past to combat inflation.

Despite ample evidence that current inflation is due not only to fossilflation but also to supply-side factors like supply chain disruptions following COVID-19, the war in Ukraine, and rising corporate profits, central banks continue to base their monetary policies on conventional models. These models assume that inflation is mainly caused by excess aggregate demand.

If central banks do not consider other causes of inflation and the necessary countermeasures, they will not be able to control price increases with interest rate hikes. Moreover, they cause unnecessary harm to the economy by increasing unemployment and jeopardizing financial stability. The ECB has so far viewed environmental and climate factors primarily as risks to financial stability. Recently, however, it has begun to include the effects of these phenomena on price stability in its analysis. These considerations must now be translated into a new monetary policy.

With the worsening environmental and climate crisis, accelerating the green transition to a more sustainable future is becoming increasingly urgent. Simply changing the incentive structure within the same framework will not be sufficient to mobilize the financial resources needed for the green transformation. A sustainable reshaping of the state and financial system requires central banks to intervene more boldly and see themselves as agents of change. If the ECB took on such a role, it would be able to effectively and purposefully direct credit toward low-carbon or carbon-free investments, thereby significantly and decisively supporting the sustainable transformation.

Nicolás Aguila is a research associate at the University of Witten/Herdecke.

Joscha Wullweber is a Heisenberg Professor of Political Economy, Transformation and Sustainability and Director of the International Center for Sustainable and Just Transformation at the University of Witten/Herdecke.

At the end of last week, the Bundesrat approved the controversial amendment to the Climate Change Act (KSG), cementing its weakening despite all criticism and protests. Alexandra Endres and Malte Kreutzfeldt analyze for you why the recent climate rulings from Berlin remain relevant even after the weakening of the KSG. Additionally, you’ll read why climate activists are now appealing to the Federal President not to sign the law.

While Germany is weakening its climate action efforts, the EU is struggling to implement stronger climate action mandates in agriculture. So far, the industry has always successfully resisted. Lukas Scheid and Julia Dahm discuss what a CO2 price in the agricultural sector could look like. Looking at Europe, we also explain why carbon leakage remains a problem and what impact US tariffs on the battery industry could have.

Today, we also report on why necessary adjustments are hardly affordable for some population groups in Germany. In our viewpoint, experts Nicolás Aguila and Joscha Wullweber call for a green monetary policy from central banks.

Following recent rulings by the Higher Administrative Court (OVG) of Berlin-Brandenburg, experts believe that the federal government will need to tighten its climate policy. This remains true even with the recently passed amendment to the Climate Change Act, as key criticisms from the court remain unaddressed. Plaintiff’s attorney Remo Klinger cannot imagine the government ignoring the ruling; what would happen in that case is currently unclear.

On Thursday, the German Environmental Aid (DUH) won two lawsuits: In the first, the organization demanded a “sufficient climate action program” to avoid exceeding the sector-specific targets in energy, industry, buildings, agriculture, and transportation as mandated by the previous version of the Climate Change Act. In the second, they demanded a similar “sufficient climate action program” to achieve the targets in the land use sector (LULUCF), which involves natural sinks like forests, moors, meadows and pastures that annually absorb and store a specific amount of CO2 to offset harmful emissions.

The court found that the German government’s 2023 climate action program did not meet legal requirements in both cases. According to its ruling, the government is now obliged to supplement the climate action program so that

Additionally, the court stated that “the 2023 climate action program suffers from methodological deficiencies and is based on unrealistic assumptions in some parts.”

The precise legal consequences of the ruling remain unclear as the written judgment is yet to be released. It is generally expected that the federal government will appeal – as it did with an earlier OVG ruling last year that required immediate climate action plans for the building and transportation sectors.

A spokesperson for the BMWK left this question open on Friday. “We need to carefully examine and evaluate this ruling and its reasoning,” she stated. In the likely event of an appeal, the case would be heard by the Federal Administrative Court, and it would take some time before a final judgment is issued. Only then would the government be required to act.

By then, the new version of the Climate Change Act, which passed the Bundesrat on Friday, would already be in force and likely applied, according to Niklas Täuber, an environmental lawyer at FU Berlin and a research associate at the Competence Network “Future Challenges of Environmental Law”. “It is likely that a judgment will be based on the amended law,” Täuber told Table.Briefings.

Environmental lawyer Remo Klinger, who represented the DUH in the case, agrees. “I assume that in the appeal, the new law will apply because it concerns a program for the future,” Klinger told Table.Briefings. However, much would not change, as two of the three key grounds for the ruling are unaffected by the amendment. “The LULUCF target and the overall goal for 2030 remain unchanged.”

Therefore, the new law would only impact the failure to meet sector-specific targets. This point would become irrelevant, as the amendment removes their legal bindingness. However, the overarching emission target of a 65 percent reduction by 2030 and the LULUCF targets, which are clearly being missed, remain significant: Instead of storing 40 million tons of CO2 annually as stipulated by law, land-use changes are projected to release greenhouse gases after 2040.

In the proceedings, it will be crucial how the Federal Administrative Court evaluates the government’s emission projections for the years leading up to 2030. In its 2023 projection report, the government admitted a gap of about 200 million tons of CO2 equivalents. However, new projections from April 2024 suggest that achieving the overall target is possible. The OVG did not consider these, criticizing in its oral ruling that these did not account for the impact of the Federal Constitutional Court’s ruling on the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF) – i.e., the current projection report is too optimistic about the expected emission reductions.

The Expert Council for Climate Issues, appointed by the government, is currently examining the accuracy of these projections. However, Brigitte Knopf, the council’s deputy chair, stated during the OVG hearing that about half of the measures in the climate action program are financial support programs and the Constitutional Court ruling has now deprived them of funds. Therefore, the effectiveness of the government’s planned climate action measures is likely to be lower than previously assumed.

Regarding what needs to be done to comply with the ruling, environmental groups have clear ideas. To achieve the overall target by 2030, especially the transportation sector must take further action, according to DUH Co-Chief Resch. The responsible minister, Volker Wissing, must no longer “refuse measures like a speed limit on highways or stopping subsidies for environmentally harmful company cars.” Additionally, more funds are needed to meet the LULUCF targets. “Given the upcoming budget negotiations, we urge the government to finally eliminate climate- and environmentally harmful subsidies and to exclude important funding instruments like the Natural Climate Action Program from further cuts,” says Florian Schöne, managing director of the environmental umbrella organization DNR.

The recent rulings have also sparked discussions about what happens if the government does not comply with the court’s demand to tighten climate targets. Environmental lawyer Täuber believes that little will change without the necessary political will. “If a citizen does not comply with a court ruling, the state can enforce it with force if necessary,” says Täuber. “But if a court ruling obliges a state actor, such as the government in this case, and it does not comply, there are no comparable enforcement mechanisms.”

DUH attorney Klinger finds the question of what happens if the government ignores the ruling absurd. “As long as we do not have a populist government, I think this discussion is nonsense,” he says. “I naturally assume that the government will comply with supreme court decisions.”

What can happen if authorities do not comply was made clear a few years ago when the state of Bavaria refused to implement a ruling that required effective air pollution control through diesel driving bans. At that time, fines were initially imposed. However, this measure is “ultimately inconsequential,” as it merely shifts public funds “from one pot to another,” Täuber says.

A more severe measure, such as coercive detention against the responsible officials, is “difficult to enforce, if legally permissible at all, and certainly not politically feasible“. DUH lawyer Klinger does not want to speculate on this possibility, but he is well acquainted with the details: In the DUH’s case against the state of Bavaria, he was the one who had the legal feasibility of coercive detention examined and later applied for it.

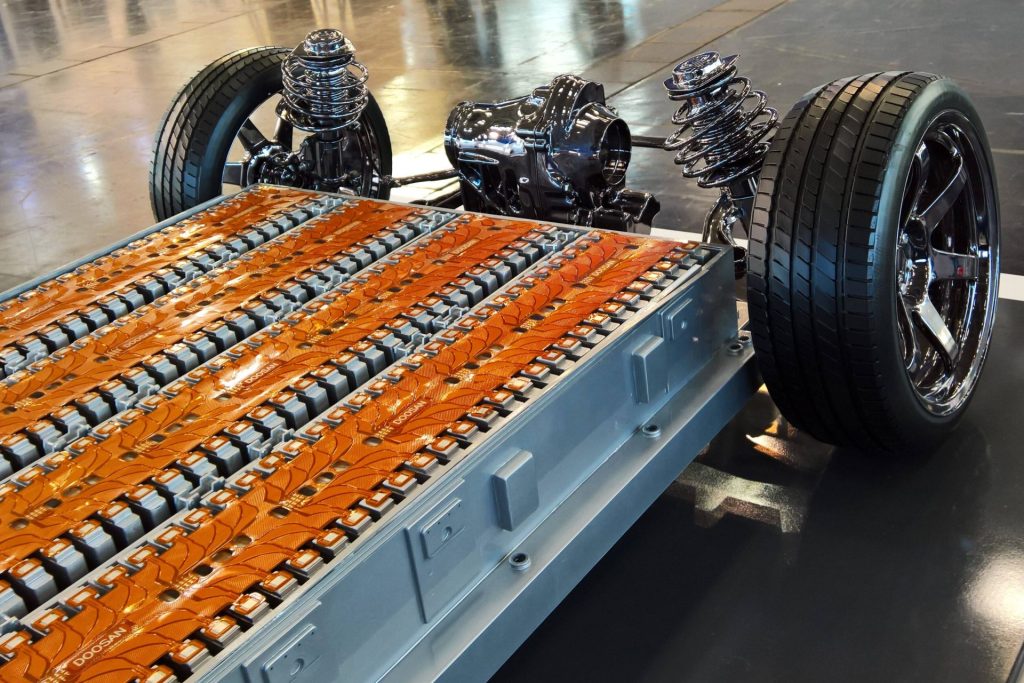

The US tariff increase on Chinese electric car batteries will likely shift Chinese exports to Europe. Last week, President Biden announced additional tariffs on Chinese electric car batteries, battery parts, electric vehicles and solar panels to counteract the flood of cheap Chinese overcapacities.

Tariffs on electric car batteries have tripled to 25 percent. In 2026, tariffs on lithium-ion batteries used in other applications, such as energy storage systems, will also be increased. “If Europe does not follow suit with similar tariffs, Chinese batteries will become even cheaper for Europe because the overcapacities have to go somewhere,” says Dirk Uwe Sauer, a professor at RWTH Aachen, to Table.Briefings.

For European manufacturers, this means even more competition. “For the efforts of ACC, Northvolt and VW/PowerCo to produce their own batteries in Europe, this will be a particular burden,” says Sauer. The start-up of new factories will coincide with a period of absolute price competition, making it especially difficult for newcomers.

The battery market already has massive overcapacity. China alone has production capacities sufficient to meet global demand. The country dominates all steps of the supply chain. Experts warn that overcapacity could continue to rise as companies in Europe, the USA, and China continue to invest billions.

By the end of 2025, there could be 7.9 terawatt-hours of global battery production capacity, according to BloombergNEF (BNEF) analysts. However, demand will only be 1.6 terawatt-hours. Even if many of these new factories do not move beyond the planning stage, “the market is heading for an even greater oversupply,” write BNEF experts.

Other experts also believe that the new US tariffs “could drive Chinese batteries to Europe,” as battery expert Andy Leyland of consultancy Benchmark Minerals wrote on Twitter. Earlier this year, Leyland was more optimistic about Western battery manufacturers. “The order books of [Western] companies like Northvolt, LG Chem, and Panasonic are well filled for years,” he wrote.

According to him, China is “in a problematic situation”. The country must export its overcapacities in “Chinese electric cars, electronics and batteries for energy storage,” says Leyland. The market for energy storage systems will experience a significant additional supply of batteries to complement solar and wind storage. “This is a nice boost for the energy transition,” Leyland believes.

Batteries are considered one of the most important future technologies. They are seen as the “new oil” and a “master key” to accelerating the transformation of the energy and transportation systems. Countries leading in the battery sector could achieve “great industrial gains” in the future, according to a recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA). Currently, China is still the leader in the battery industry. Europe, though still very dependent on China, is catching up thanks to government support and large investments.

Batteries are seen as a key technology for several reasons:

Currently, China dominates large parts of the battery supply chain:

The USA and Europe, however, are catching up and have established numerous factories in recent years. Many more are in the planning stage. According to the IEA, the USA and Europe could meet their battery demand with domestic production by 2030. According to the NGO Transport and Environment (T&E), this could be possible by 2026.

For critical components like cathodes and anodes, however, China’s dominance will likely continue, according to the IEA. T&E also criticizes that there are only two cathode factories in Europe, despite the continent’s potential to meet more than half of the demand through domestic production.

China’s market dominance is due to a long-term industrial policy and subsidies for battery manufacturers. Manufacturers in China are among the technological leaders and can produce large quantities at low prices due to lower energy and labor costs compared to Europe.

The success of European manufacturers in the market will also depend on politics. Europe has significant competitive disadvantages. In Europe, “both the capital expenditures (CAPEX) and operating costs (OPEX) for building and operating battery cell, component, and material factories” are particularly high, writes Transport and Environment. If Europe offered the same government support as the USA under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the annual operating costs for battery factories alone would amount to 2.6 billion euros, the organization calculates.

However, there are other ways to support the industry: “Environmental, social, and governance standards will be crucial in determining market winners and losers,” writes the IEA. T&E calls for a secure investment environment and adherence to phasing out internal combustion engines. Additionally, investment aids at the EU level and “stronger ‘Made in EU‘ requirements for public procurement, subsidies, and EU grants and loans for EV and battery manufacturers” are needed.

According to the European Commission, agriculture accounts for more than ten percent of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions. The sector’s emissions have not decreased in the past two decades. Addressing these emissions in light of the EU’s climate goals could become a significant issue in the upcoming legislative period.

The main controversy is whether and how to include agriculture in the mandatory EU emissions trading system. Currently, agriculture is the only climate-relevant sector whose emissions are not subject to pricing. However, this topic is divisive, even within the European Commission.

On one side is the Directorate-General for Climate Action (CLIMA). Last year, it sparked the debate by commissioning a study on CO2 pricing in agriculture and its value chain. The study is also intended to contribute to the political discussion surrounding the 2040 climate goal, according to DG CLIMA upon its publication in November.

The Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (AGRI) takes a more cautious approach. AGRI Director-General Wolfgang Burtscher recently acknowledged at an event in Brussels that the pressure to reduce agricultural emissions is high and that the debate on CO2 pricing is gaining momentum. However, he argued that emissions could also be reduced through incremental measures incentivized by the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

So far, this has not worked: A 2021 report by the European Court of Auditors concluded that despite substantial funding, the CAP has hardly contributed to emission reductions. The debate is also likely to be influenced by the political climate around farmer protests. In February, the Commission significantly softened the section on agriculture in its recommendation for the 2040 climate goal compared to earlier drafts. The idea of a mandatory emissions trading system is unpopular in the industry.

The German Farmers’ Association (DBV) argues in a position paper that inclusion in the statutory emissions trading system is “not feasible” due to the structure of agriculture, the nature of emissions based on natural processes and administrative hurdles. Instead, the industry favors voluntary compensation for CO2 sinks and positive financial incentives for emission reductions. Similarly, Peter Liese, MEP and rapporteur on emissions trading, wants to emphasize the benefits for farmers.

Nonetheless, DG CLIMA is not giving up: It has commissioned a new study to be developed starting mid-year. The results could be ready in time for the plans for the 2040 climate goal to be translated into law after the election, including an impact assessment for a CO2 price in agriculture.

The debate on how to price agricultural emissions to apply the polluter-pays principle to agriculture, as demanded by the European Court of Auditors, is in full swing. One option would be a CO2 tax – the most direct form of CO2 pricing. However, this is considered difficult to implement due to national sovereignty over tax matters.

It is conceivable to include agriculture in the existing EU emissions trading system for industrial plants. The market and structure already exist and legal implementation would be relatively straightforward. However, the agricultural sector consists of over nine million farms with emissions of around 400 million tons of CO2 equivalents. The impact of their inclusion on price stability in the ETS would be difficult to calculate and potentially counterproductive for climate action.

The incentive for emission reductions in sectors already covered by the ETS could decrease due to falling prices, warns Hugh McDonald, a fellow at the Ecologic Institute and one of the authors of the first study on CO2 pricing in agriculture for DG CLIMA. “Looking ahead to 2050 maybe it makes sense to have one price to rule them all. But I think what we’re talking about at the moment is the next 10 to 15 years.”

Additionally, there should be benefits for farmers and landowners, says McDonald. “Otherwise, it will be difficult to enforce this policy.” He refers to the reward for carbon dioxide removal through land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF). One possibility would be to link the pricing of emitted greenhouse gases with compensation for sequestered emissions.

Such a model would also address the demands of prominent economists and the European Court of Auditors to reward farmers for CO2 removal. And it seems Brussels is already considering this. The orders for the development of the two studies on an agricultural ETS came from the department within DG CLIMA responsible for CO2 removals, rather than the emissions trading experts.

The question is whether the two activities – emitting and removing – can be linked in a single system or need to be separated. McDonald believes that a separate system is more practical in the medium term. This way, there can be two distinct goals – one for emission reductions and one for CO2 removals. “The risk with a combined system is that it could be cheaper for farmers to buy low-quality removal certificates instead of reducing their own emissions.”

However, McDonald warns against focusing solely on an agricultural ETS. There are other political measures that are simpler and quicker to implement and thus more effective for reducing agricultural emissions. The economist still sees great potential in redesigning the 60 billion euros CAP subsidies as a climate action instrument. “Making changes in the Common Agricultural Policy is politically very difficult, but on a technical level we’ve already got a structure and all this money flowing into the scheme.”

A new system like an ETS, including compensation for CO2 removals, would have to compete with the vast sums from the CAP. Therefore, a redesign of the CAP would be inevitable if agricultural emissions are to be reduced, believes McDonald. This is also a task for the next legislative period: the Commission is expected to present initial ideas next year on what the CAP should look like after the current funding period ends. The current CAP runs until 2027 but could be extended.

Appeals from environmental organizations and CDU climate expert Andreas Jung were in vain: Following the Bundestag, the Bundesrat also approved the controversial amendment to the Climate Change Act (KSG). During the session on Friday, the state representatives refrained from calling for a mediation committee, which several environmental organizations had demanded beforehand.

Additionally, a formal error in the text of the law was discovered last week. The attempt to correct this without another vote was thwarted by the opposition from the Union. They had demanded that the vote in the Bundesrat be postponed and that the law be reconsidered in the Bundestag. Instead, the flawed law was adopted without debate in the Bundesrat. The error is to be corrected later in a separate procedure.

The final hurdle is now the required signature of the law by the Federal President. Normally, this is a mere formality; however, in this case, the German Environmental Aid (DUH) hopes that Frank-Walter Steinmeier will not sign the law due to the error and constitutional concerns.

In a letter to the federal president, DUH lawyer Remo Klinger details why, in his view, the amendment contradicts the climate ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court from 2021, which he helped secure. The letter concludes by stating, “Since the amendment is unconstitutional for the reasons mentioned here, we kindly ask you, Mr. Federal President, not to sign the law.” mkr

The use of “clean hydrogen” could lower the costs of worldwide decarbonization by 15 to 22 percent, as concluded by a recent study. Researchers achieved this result by further developing the Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM) and analyzing the costs and benefits of deploying hydrogen in 24 scenarios aiming for a climate-neutral energy system by 2050. These scenarios vary in assumptions regarding socio-economic development as well as the availability of hydrogen, batteries, and net-negative technologies (DACCS and BECCS).

Due to costly technical barriers, hydrogen is projected to only provide three to nine percent of the global energy supply by 2050. However, achieving climate neutrality in scenarios with hydrogen is more cost-effective than in scenarios without it. Particularly in sectors challenging to electrify, such as international shipping or heavy-duty trucking, its deployment leads to cost savings.

For researchers, “clean hydrogen” includes not only green hydrogen from renewables but also so-called “blue hydrogen”, where emissions are captured through CCS during production. However, many experts view this skeptically. Johan Lilliestam, Professor of Sustainability Transition Policy at Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg, comments, “From a climate perspective, blue hydrogen with CCS is not a reasonable solution.” Firstly, it cannot capture all CO2 emissions during production, and secondly, there are still issues with emissions from pipeline leaks. kul

To achieve the EU’s long-term climate goals, a carbon price is deemed more effective than regulatory climate action measures and subsidies guided by climate criteria. This is the outcome of a report by the Centre for European Policy (CEP). Emissions trading is considered environmentally effective, economically cost-efficient, socially acceptable, and politically stable even during crises.

Hence, the experts also recommend expanding the existing EU Emissions Trading System (ETS 1) for energy and industry to include the agricultural and land-use sectors (LULUCF). Additionally, ETS 1 should be merged with ETS 2 for building heating and transportation. While having two parallel systems might be sensible in the short term, it weakens incentives for emission reductions in the medium to long term due to different reduction paths and resulting carbon prices.

Moreover, the EU’s climate policy still lacks an effective and comprehensive system to prevent carbon leakage. The Fit-for-55 package does not ensure equal competitive conditions for European companies. European producers competing internationally will face a carbon price, while their international counterparts mostly will not. Therefore, resolving the carbon leakage dilemma should be “urgently placed at the top of the EU agenda for 2024-2029,” as advocated by CEP experts.

Unilateral trade measures like the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) are considered only the “second-best” solution and may even prove counterproductive. CBAM could be circumvented by importing processed products not covered by CBAM instead of raw materials subject to it. Instead, the EU should pursue multilateral solutions, such as international climate clubs or joint emissions trading systems with third countries. luk

According to the Polish government, sanctions on the import of fossil Russian energy carriers into the EU should be implemented more quickly and effectively. This was stated by Urszula Zielińska, State Secretary from the Polish Ministry of Climate and Environment, on Friday at the German-Polish Energy Transition Forum at the Foreign Office in Berlin.

In particular, the green State Secretary criticized that the import of processed oil products such as diesel from Russian crude oil through third countries like India and Turkey is still possible. “Under these circumstances, the EU’s climate policy, with the shift away from coal, natural gas and oil towards clean energy sources, has taken on a new dimension,” said the deputy of Minister Paulina Hennig-Kloska. Zielińska accused Russia of conducting disinformation campaigns on climate policy in Poland, Germany, and other EU countries.

One topic for cooperation mentioned by Udo Philipp, State Secretary from the German Ministry of Economic Affairs, is the construction of offshore wind farms. Poland has more experience in building foundations than Germany: “Through our coordination, we could also use infrastructure such as ports and ships more efficiently.” Poland also has potentials for hydrogen storage and demand flexibility. Regarding the latter point, the BMWK has already launched an initiative with France to better integrate renewable energy generation peaks into the European electricity market. ber

The Climate Neutrality Foundation is working towards assessing the social conditions in Germany concerning the climate transition and the consequences for selecting suitable policy instruments. Initial results were presented last week. They are based on 14 data categories (including age, income, property ownership) and 20 formed clusters.

Additionally, 16 different types of individuals (“personas”) were identified. The group classified as the “heat pump generation,” comprising three percent of the population, has built or purchased a house on the outskirts of a small town in the past 20 years. Their energy consumption is already low, and significant investments for the heat transition are not necessary. Due to their “good financial situation” with purchasing power, they have already begun transitioning to electric mobility.

The situation is entirely different for the “precarious rebuilding generation“, representing 15 percent of the population. On average, these individuals are 79 years old and reside in often very old single-family homes. Even with significant support programs, they cannot make their homes climate neutral on their own. Neither electric cars nor public transport are realistic alternatives for climate-neutral mobility for these individuals.

For citizens with poor adaptability, an expansion of public services, such as the expansion of district heating networks and public transportation, is necessary. Other important measures include:

There is a significant disparity in the adaptability of citizens between urban and rural areas, as well as between cities themselves (see chart). Accordingly, the regional needs for climate and mobility transition vary greatly. cd

Faced with the highest inflation in over four decades, the central banks of major economies have gradually increased interest rates and initiated a policy of quantitative tightening (QT) since 2022.

In our recent article, we argue that interest rate hikes do not address the environmental causes of inflation and can even exacerbate long-term inflation by making necessary investments for the green transition more expensive and thus delaying them.

Instead, a monetary policy framework is needed that can address both inflation and the environmental crisis. Fabio Panetta, the current Governor of the Bank of Italy and former ECB Board member, referred to such approaches as “greener and cheaper“.

Interest rate increases have a disproportionately high impact on sustainable investments compared to carbon-intensive investments. Sustainable investments are more capital-intensive, require greater upfront investment and need more debt financing. As a result, they are more sensitive to cost increases (especially borrowing costs) than their carbon-intensive competitors.

In addition, QT has also significantly reduced the potential of quantitative easing (QE) to support green investments through easier financing and lower borrowing costs. Higher interest rates can therefore delay the green transition by increasing the cost of sustainable investment. This policy is, therefore, not only short-sighted in terms of climate policy but also worsens the prospects for price stability.

Empirical studies show that the environmental crisis is also a source of inflation. ECB Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel names three types of shocks that can have an impact on prices:

The current macroeconomic environment requires a monetary policy approach that addresses the climate and environmental crisis while combating inflation. This is not only necessary for economic and environmental reasons, but is also in line with the main mandate of central banks.

Numerous tools are discussed in the literature for this purpose, including asset purchases, lending policies and financial regulations. A particularly promising approach is direct credit allocation, which was common in advanced economies in the past and is still used in some developing countries. Here, central banks steer credit allocation in a green direction. A variety of tools can be used for this purpose, benefiting banks, businesses, and governments, including:

Additionally, credit steering policies have been successfully used in the past to combat inflation.

Despite ample evidence that current inflation is due not only to fossilflation but also to supply-side factors like supply chain disruptions following COVID-19, the war in Ukraine, and rising corporate profits, central banks continue to base their monetary policies on conventional models. These models assume that inflation is mainly caused by excess aggregate demand.

If central banks do not consider other causes of inflation and the necessary countermeasures, they will not be able to control price increases with interest rate hikes. Moreover, they cause unnecessary harm to the economy by increasing unemployment and jeopardizing financial stability. The ECB has so far viewed environmental and climate factors primarily as risks to financial stability. Recently, however, it has begun to include the effects of these phenomena on price stability in its analysis. These considerations must now be translated into a new monetary policy.

With the worsening environmental and climate crisis, accelerating the green transition to a more sustainable future is becoming increasingly urgent. Simply changing the incentive structure within the same framework will not be sufficient to mobilize the financial resources needed for the green transformation. A sustainable reshaping of the state and financial system requires central banks to intervene more boldly and see themselves as agents of change. If the ECB took on such a role, it would be able to effectively and purposefully direct credit toward low-carbon or carbon-free investments, thereby significantly and decisively supporting the sustainable transformation.

Nicolás Aguila is a research associate at the University of Witten/Herdecke.

Joscha Wullweber is a Heisenberg Professor of Political Economy, Transformation and Sustainability and Director of the International Center for Sustainable and Just Transformation at the University of Witten/Herdecke.