For the first time, developed nations have delivered on their climate finance pledges to developing and emerging countries: Over 100 billion US dollars in 2022. The new OECD figures will be published shortly before the Bonn Climate Change Conference, which Climate.Table will report on in detail. Nico Beckert has analyzed who the big donors are, who is stingy and what this means for the negotiations in Bonn over the new climate finance target.

Meanwhile, oil giant ExxonMobil struggles to make profits in the fossil fuel sector. These are lower than last year. Exxon is also at odds with its own shareholders over whether efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions should be stepped up. Carbon capture will likely play a significant role here, as Exxon expects global demand for crude oil and natural gas to continue for the foreseeable future.

And in Germany, Economy Minister Robert Habeck is paving the way for carbon capture. According to the new CCS Act, carbon capture and storage will at least be permitted offshore in the future. The cabinet has also passed a new hydrogen bill; earlier in this week, the German government presented plans for green shipping.

And one piece of good news emerges from China: Emissions may have peaked and will now start to decline.

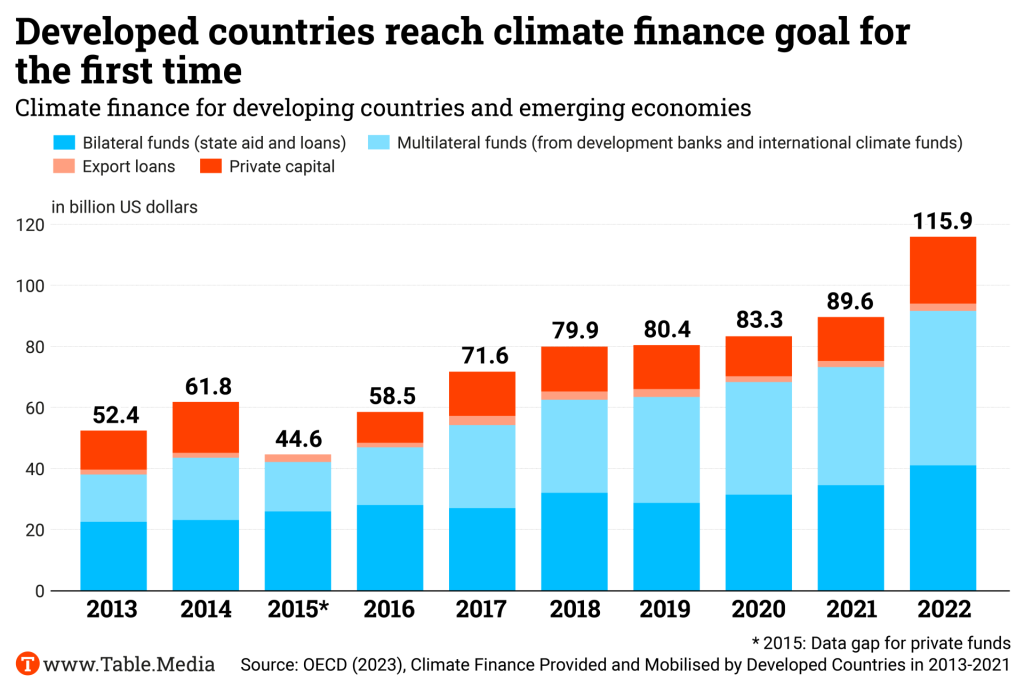

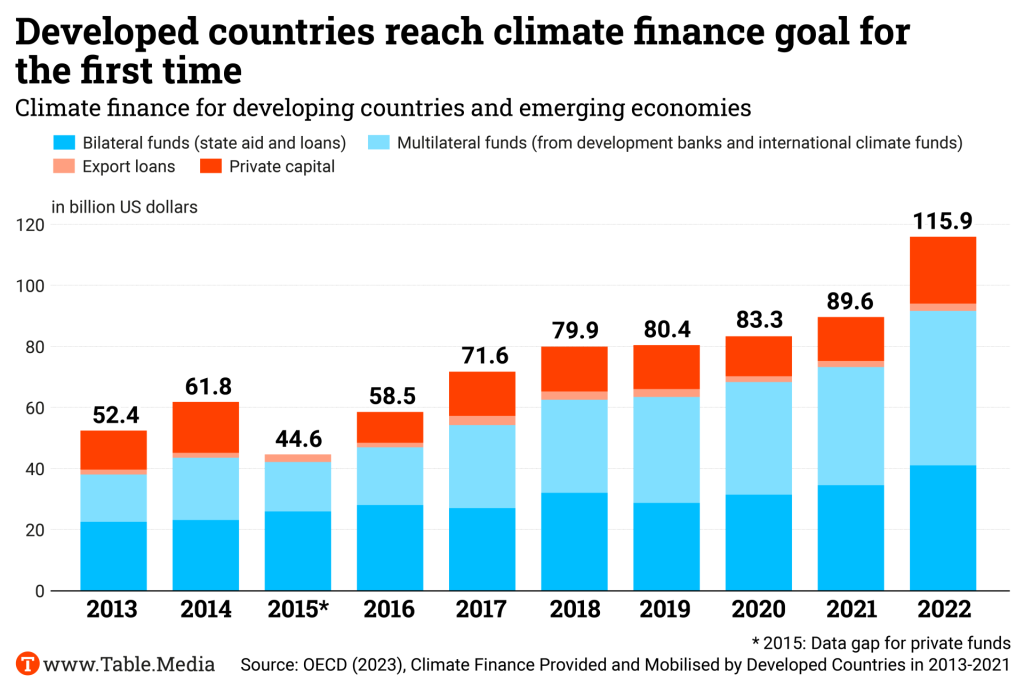

Shortly before the Bonn Climate Change Conference SB60 next week, positive news has come from climate finance: According to new OECD figures, developed countries mobilized 115.9 billion US dollars in climate finance for developing and emerging countries in 2022. This is the first time that the 100 billion target that developed countries exceeded the goals set for 2020 at COP15 in Copenhagen.

The money provided was 26.3 billion dollars higher than in 2021. However, there are unanswered questions about climate change adaptation, private funding, and the actual amount of climate financing. The OECD has recorded a decline in funding from multilateral climate funds.

“The growth in 2022 compared to 2021 is remarkable,” says Jan Kowalzig, climate finance expert at Oxfam. However, the level must be maintained and increased “to compensate for the under-fulfillment of the 100 billion targets accumulated in 2020 and 2021.” According to the OECD, countries are well on making up for this. “The significant increase in climate finance from private channels mobilized through public funds is particularly striking,” says David Ryfisch, Head of Sustainable Finance Flows at Germanwatch.

A new climate finance target (New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance – NCQG) for post-2025 will also be negotiated in Bonn. The big leap in fulfilling the 100 billion target could provide a tailwind.

However, Jan Kowalzig is unsure “how much of the 116 billion has actually contributed to climate action and adaptation, as the climate impact of some of the projects is often calculated too generously.” Although the figure is generally reliable, some projects with marginal climate impact are always included. The “big leap to 116 billion,” on the other hand, is most likely not the result of a “vague definition of climate action projects, but is probably due to actual growth.”

In 2022, 32.4 billion dollars flowed into the adaptation. This is also a new record. However, the share of adaptation funds, which should be approaching the 50 percent mark, of total spending decreased and is now only 28 percent of the 116 billion. In 2020, it was still at 34 percent. According to the OECD, developed countries are “about halfway towards meeting the call to double the provision of adaptation finance.”

This is where Kowalzig voices criticism: “In vulnerable countries in particular, this means that important programs for adapting livelihoods to climate change, securing harvests or protecting against disasters are either not being funded at all or only inadequately.” In addition, a lot of money flowed into several large adaptation projects in 2022. “It is unclear whether this is a one-off effect,” says Kowalzig, meaning whether the figure for 2022 is distorted or adaptation funding is moving permanently in the right direction.

Private funds saw the largest percentage jump. The developed countries could mobilize 21.9 billion dollars in private funds, 52 percent more than in 2021. “Firstly, the higher mobilization of private funds is very positive,” says Kowalzig. “However, there is no discernible trend for the future. The OECD does not explain the increase either.”

According to the OECD, the majority of private funds mobilized (48 percent) went to the energy sector. “This is also because renewable energies are becoming increasingly cheaper,” says David Ryfisch. “This means that public funds can better cushion residual investment risks.”

Bilateral and multilateral funds, for example, in the form of government grants or funds from development banks, account for the lion’s share of the 116 billion. Multilateral funds saw the biggest jump in absolute terms – from 38.7 billion to 50.6 billion. However, Ryfisch emphasizes that there is also “bad news” here: “The multilateral climate funds provided less climate financing than in the year before.” These funds are “particularly important for equitable climate financing” because developing countries have a say in how the funds are spent. “In 2023, for example, the Adaptation Fund fell well short of its mobilization target – i.e., the money provided by donors,” says Ryfisch.

The majority of public climate financing still flows in the form of loans. “This exacerbates the already overwhelming debt burden of many low-income countries,” Kowalzig from Oxfam criticizes. However, their share is decreasing slightly. In 2022, loans still accounted for more than 69 percent of public funding, compared to 74 percent in 2018.

Furthermore, 57 percent of private funds concentrated on just 20 recipient countries. According to the OECD, this is owed to large infrastructure projects requiring substantial funding. However, this uneven distribution of climate finance also includes multilateral and bilateral sources. 20 countries receive more funding from multilateral climate funds than the remaining 133 countries combined, the Boell Foundation criticizes.

57.6 billion dollars of the total amount went to low-income countries (11.1 billion) and low-middle-income countries (46.5 billion). The poorest countries receive the majority of the funds (64 percent) through grants. The low-middle-income countries saw the biggest jump.

“For the developed countries, the new figures naturally mean a lot of tailwind. They will argue that they have reached the 100 billion target,” says Jan Kowalzig from Oxfam. Achieving the target could also give new impetus to the debate about new donor countries. “Exceeding the 100 billion target – especially by 16 billion – takes the wind out of the sails of the countries that criticized developed countries for missing the 100 billion target,” says Ryfisch from Germanwatch. “China, the Gulf states and others can no longer retreat to the position that the developed countries should first meet their target before they themselves participate in international climate financing.”

According to reports, the negotiators want to publish concrete proposals for the NCQG for the first time in Bonn. However, many questions are still unclear:

ExxonMobil, the largest oil company in the United States, with a market capitalization of more than $500 billion, is hosting its annual shareholder meeting on Wednesday. In addition to internal issues, the company is currently engaged in a dispute with its own shareholders over its climate policy. The meeting ended after this issue of Climate.Table was published

The oil giant is facing a number of internal and external pressures. The company’s profits were down 28 percent in the first quarter of 2024 compared to the same time last year due in part to low natural gas prices and lower profits in oil refining.

Exxon is also in a messy legal fight with Chevron over the latter’s 53 billion US dollar acquisition of Hess Corporation. Exxon claims that under a prior agreement, it has the right of first refusal over Hess’s assets in Guyana, including a large offshore oil field. The case is currently under arbitration and the dispute may not conclude until next year.

But the biggest headache for Exxon at its shareholder meeting will likely be its own shareholders. The company went on the offensive earlier this year, suing two of its shareholders, Arjuna Capital and Follow This. The shareholder groups intend to bring climate-related measures to a vote at the meeting. They want to push the company to do more to mitigate climate change and limit its greenhouse gas emissions.

However, Exxon CEO Darren Woods said these groups were hijacking and abusing the voting process for publicly-traded companies. “These activists have no interest in the economic well-being of our company,” Woods said earlier this year at the CERAWeek by S&P Global energy conference in Houston, Texas.

The fight has exposed a rift among Exxon’s other stockholders. Officials from 19 states led by Republicans are urging investors to back Exxon’s management. Meanwhile, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) is urging Exxon to drop its lawsuits against Arjuna Capital and Follow This. CalPERs is the largest public pension fund in the US and has a 0.2 percent stake in Exxon.

Shareholders have succeeded in pushing Exxon on climate in the past. In 2017, they pressured the company to put a climate scientist, Susan Avery, on their board. However, Avery said earlier this year she would not stand for re-election to the post, and it’s not clear that Exxon is looking for another climate scientist to replace her. In 2021, investment firm Engine No. 1 managed to place two of its members on Exxon’s board to advocate for more action on climate change.

It’s hard to say whether these moves have led to any major shifts. Exxon’s oil production has been trending downward over the past decade, though it increased last year.

For its part, Exxon says that it’s doing more than ever to address climate change. Woods noted that he attended COP28 last year, marking the first time he’s been to an international climate negotiation meeting. Exxon began to publicly report its Scope 3 emissions in 2021, though the company has not committed to a reduction target. The company is now deploying carbon capture technology, preventing methane leaks, and developing hydrogen infrastructure, aiming to spend more than 20 billion US dollars between 2022 and 2027. Woods also praised the Inflation Reduction Act, the largest single US government investment to deal with climate change, because the law on paper is technology-neutral. “We’re going to need everything that works to drive emissions down,” Woods said.

But for Exxon, “everything” also includes more fossil fuels. The company is projecting that global oil and natural gas demand will continue to rise into the 2040s, so it’s counting on technologies like carbon capture to negate its impact on the climate and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

Environmental activists also note that Exxon understood its role in changing the global climate for decades, yet still sowed misinformation about warming and worked to block legislation behind the scenes. That track record makes it hard for climate campaigners to take Exxon’s climate work as a good-faith effort. That’s why they’re trying to flex their power as shareholders, to get into the rooms where decisions are made and force the company to make better ones for the climate.

June 2, Mexico

Elections Presidential elections in Mexico

Mexico is voting – and it is relatively certain that the country will have its first female president.

June 6-9

Elections European elections

The European Parliament elections will be held from June 6 to 9. Find all news, analyses and updates in our series on the European elections. Info

June 6-13, Bonn

Conference 60th Sessions of the UNFCCC Subsidiary Bodies

The SB60 conference of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) serves primarily as a preparatory conference for COP29 in November. Below we have compiled some highlights from the first few days. Info

June 3, Bonn

Conference Negotiations on NCQG

The negotiations on a New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance will be the focus of SB60 and COP29. Info

June 3, 11:45 a.m. CEST, Room Berlin

Side Event Water Resilient Food Systems

The SB60 side event, organized by the UNFCCC, aims to catalyze policy integration and foster stakeholder collaboration to actively promote water-resilient food systems while effectively addressing challenges related to climate change, desertification, and biodiversity conservation. Info

June 3, 1:15 p.m. CEST, Room Bonn

Side Event Operationalizing Article 6: A playbook for governments and crediting programmes

Over 50 countries have Article 6 agreements but the path to implementation is complex. Singapore, Verra and Gold Standard are launching a “playbook” with other countries to help standardize how governments and crediting programs can integrate robust carbon crediting into NDC implementation. Info

June 4, 4:15 p.m. CEST, Room Berlin

Side Event Making climate finance work for all: how to agree an ambitious NCQG

The event draws on new Alliance & ODI research providing a framework for burden sharing in the NCQG built on CBDR principle, ensuring developed countries provide their fair share and assessing the state of the contributor base while stressing the importance of a core of public grant-based finance. Info

June 6, 11:45 a.m. CEST, Room Berlin

Side Event Climate Justice and Gender Equality: Addressing the Intersectional Impacts of Climate Change

The event will foster collaboration among stakeholders – government, CSO, and faith-based groups – to boost gender-responsive resilience amidst climate-induced losses and damages. Info

June 7, Bonn

Briefing COP29 Presidential Briefing on Logistics

The COP 29 Logistics briefing will be held in Bonn in the Plenary New York, WCCB, Main Building. Info

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts that the Caribbean is in for a season with an exceptionally high number of hurricanes. The hurricane season between June 1 and November 30 could see up to 25 strong tropical cyclones, up to half of which forecasts predict could become hurricanes. An average season sees 14 tropical cyclones.

One of the main reasons is the already high ocean temperatures in the Atlantic, as the German newspaper FAZ explains. Currently, the water temperature in the area where hurricanes develop is around 1.3 degrees above average. This also means that the heat content of 41.8 kJ/cm² in the hurricane development area is at a record level at this time of year. Hurricanes draw their energy from the surface water, and the higher the temperatures, the higher the energy content. Heat contents of more than 40 kJ/cm² are generally not reached until the beginning of August. In addition to the high temperatures, the expected rapid change from El Niño to La Niña is another reason why the hurricane season is expected to be particularly active. kul

On Wednesday, the German Federal Cabinet passed a bill to enable the capture, storage and export of carbon dioxide in Germany. Compared to an earlier draft of the Carbon Capture and Storage Act (KSpG), the nature conservation requirements for potential carbon dioxide storage areas in the German North Sea have been tightened. For example, storage beneath marine conservation areas is now also to be ruled out if the borehole through which the CO₂ is to be injected is located outside these conservation areas. In addition, CCS drilling is also prohibited in an exclusion zone of eight kilometers around protected areas.

Environmental groups welcomed this amendment. “The BMUV has obviously made improvements,” commented energy expert Constantin Zerger from Environmental Action Germany. However, he also criticized the law’s provision empowering the Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action to lift the storage ban under marine conservation zones. However, according to the law, this is only possible if an evaluation proves beforehand that the storage capacities of the other marine areas in the German economic zone are not sufficient – which is unlikely in the coming years. Onshore storage will only be possible if a federal state authorizes it with its own law; given the massive protests in the past, this is also considered unlikely.

Environmental and climate protection organizations mainly criticize something else. Although the Ministry of Economic Affairs consistently emphasizes the importance of CCS for “difficult or unavoidable emissions” in its communication on the CSS Act, its use is not limited to industries such as cement or lime production. Instead, CCS is also permitted for carbon capture at gas-fired power plants, even though these emissions are not unavoidable and conversion to hydrogen is a better alternative from a climate perspective. In contrast, the law explicitly excludes the use of CCS at coal-fired power plants; the new draft clarifies that this also applies to combined heat and power plants.

“The use of carbon capture and storage in gas-fired power plants would harbor the massive risk of a fossil lock-in, making it extremely difficult to phase out natural gas-fired power generation,” Germanwatch expert Simon Wolf criticizes. “Carbon capture at power plants requires high initial investments, which are only profitable for operators if they can convert natural gas into electricity in the long term. However, this is incompatible with Germany’s climate targets.” Viviane Raddatz from WWF also calls for CCS to be ruled out for gas-fired power plants. The technology must be “limited to very few, currently unavoidable residual industrial emissions.”

Despite the approval, the Ministry of Economic Affairs is counting on the technology not being used there. This is because financial support for CCS has not yet been provided in this area. Without it, the technology would not have established itself on the market, said Economy Minister Robert Habeck at the presentation of the CCS key points in February. A recent FAQ paper from the Ministry is less clear: “According to the current status, much indicates that CCS will play a comparatively minor role in the energy sector.” The industry association BDEW also believes the question is still open. “The extent to which CCS can play a role for gas-fired power plants will depend on the costs, the infrastructure and the flexibility of the plants,” explained Managing Director Kerstin Andreae.

Whether the bill will pass the Bundestag in this form remains to be seen. The Free Democratic Party (FDP) has been pushing for the authorization of CCS for gas-fired power plants on the grounds of “technological openness.” The Social Democratic and The Green parliamentary groups, on the other hand, have so far rejected the use of CCS in the energy sector – and, therefore, also for gas-fired power plants.

Together with the CCS Act, the Cabinet also passed the Hydrogen Acceleration Act on Wednesday. It provides for significantly faster approval and planning processes for constructing hydrogen infrastructure. According to Habeck, this is “crucial for the decarbonization of industry.” Tobias Pforte-von Randow from the environmental umbrella organization DNR, however, criticized that the law “lumps together green and fossil hydrogen as well as simple electrolyzers and terminals for highly toxic ammonia.” mkr

The German government aims to develop a national action plan for green shipping. It will be drafted under the leadership of the Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport Affairs (BMDV) and the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK). The action plan will be developed in close cooperation with the maritime sector.

Last Tuesday, the areas covered by the action plan were presented at a presentation event at the Ministry of Transport:

The action plan is intended to support the transformation of the sector and strengthen its competitiveness and innovation expertise. The results will be presented at the upcoming National Maritime Conference planned for spring 2025. Last summer, the UN organization IMO, which is responsible for global shipping, decided that the global maritime industry must reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to zero by around 2050. Around three percent of global carbon emissions are caused by international shipping. dpa/kul

China’s carbon emissions fell by three percent in March compared to the same month last year. According to an analysis by the specialist service Carbon Brief based on official figures, the expansion of solar and wind energy, which accounted for 90 percent of the growth in electricity demand, was the main reason for the CO2 decline in March 2024. Another factor was the continued weak construction activity. As a result, steel production declined by eight percent and cement production by 22 percent in March 2024 year-on-year. Both sectors have extremely high carbon emissions. According to the report, oil demand also stalled in March.

Analyst Lauri Myllyvirta from the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air concluded that China’s emissions may have peaked. “A 2023 peak in China’s CO2 emissions is possible if the buildout of clean energy sources is kept at the record levels seen last year.” According to the official climate targets, Beijing only plans to reach this peak “by 2030.”

However, Myllyvirta says the downward trend is very recent. Emissions were still rising in January and February. But this also has to do with the comparison period: In January and February 2023, China’s economy was still pretty stagnant, and emissions with it. The post-Covid recovery did not kick in until March 2023, thus increasing the basis for the year-on-year comparison. ck

The potential of bicycles to help reduce Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions has been significantly underestimated so far. If its share of the traffic volume were increased from 13 percent to 45 percent, carbon emissions from local transportation could be reduced by 34 percent by 2035. However, if the current transport policy is maintained, this share would only increase from 13 to 15 percent. These are the findings of a study by the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research (Fraunhofer ISI), commissioned by the cycling club Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrrad-Club e.V. (ADFC).

The researchers have developed a model with three expansion stages for how Germany could establish itself as a cycling country. It provides for the following measures:

According to the study, the potential of bicycle traffic can only be fully exploited if these political measures are implemented. “If Germany is serious about achieving its climate targets and a high quality of life, the bicycle must be the new gold standard for everyday mobility,” says ADFC Federal Chairman Frank Masurat. By 2035, Germany could become a “world-leading ‘bicycle country plus’.”

The study found that there is still a lot of potential, especially in regional cities such as Karlsruhe or Göttingen. There, more than 60 percent of trips could be made by bicycle. Overall, a shift to bicycles could save 19 million tons of CO2 per year – which is equivalent to a third of emissions in local public transport. In comparison: According to the Federal Environment Agency, the transport sector caused 148 million tons of emissions in 2023. ag

Higher CO2 prices, stricter energy efficiency regulations and accelerated approval procedures for renewable energies are improving Europe’s energy security. A new report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) concludes that Europe’s commitment to climate action has had a positive impact on the continent’s energy independence.

Long before Russia launched its war of aggression against Ukraine, Europe “came to rely increasingly on imported energy from ever fewer suppliers.” The IMF analyzed that economic resilience to energy disruptions had been deteriorating for 13 years.

Europe’s climate legislation, the Fit for 55 package, reverses this decades-long deterioration in energy security. If the targets are met, energy security will improve by eight percent by 2030. If the climate action measures were also continued beyond 2030 as planned, this would result in further improvements, the authors write. luk

Despite rising carbon credit costs, the low-emission production of basic organic chemicals such as plastics, detergents, and paints will remain “considerably more expensive than with conventional processes” beyond 2045, according to a study by the Office of Technology Assessment at the German Bundestag (TAB). In the calculated low-carbon variants, basic chemicals are 26 to 50 percent more expensive than competing fossil-based products.

The main price drivers are the costs of green raw materials, particularly CO2-free hydrogen. In 2020, the production of basic organic chemicals caused around 4.5 percent of Germany’s industrial carbon emissions.

In the case of cement and steel, the study notes an earlier cost parity between conventional and low-carbon products. This point could be reached as early as 2030 for cement and 2035 for steel. In 2020, these two sectors emitted just under 38 percent of industrial carbon emissions in Germany.

The study estimates the additional investment required to decarbonize the three sectors at just under 15 billion euros. However, the German Cement Works Association recently calculated investment costs of 14 billion euros for a carbon pipeline network alone, through which carbon emissions, which are difficult to avoid in the cement sector, could be transported to underground storage facilities. av

For the first time, developed nations have delivered on their climate finance pledges to developing and emerging countries: Over 100 billion US dollars in 2022. The new OECD figures will be published shortly before the Bonn Climate Change Conference, which Climate.Table will report on in detail. Nico Beckert has analyzed who the big donors are, who is stingy and what this means for the negotiations in Bonn over the new climate finance target.

Meanwhile, oil giant ExxonMobil struggles to make profits in the fossil fuel sector. These are lower than last year. Exxon is also at odds with its own shareholders over whether efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions should be stepped up. Carbon capture will likely play a significant role here, as Exxon expects global demand for crude oil and natural gas to continue for the foreseeable future.

And in Germany, Economy Minister Robert Habeck is paving the way for carbon capture. According to the new CCS Act, carbon capture and storage will at least be permitted offshore in the future. The cabinet has also passed a new hydrogen bill; earlier in this week, the German government presented plans for green shipping.

And one piece of good news emerges from China: Emissions may have peaked and will now start to decline.

Shortly before the Bonn Climate Change Conference SB60 next week, positive news has come from climate finance: According to new OECD figures, developed countries mobilized 115.9 billion US dollars in climate finance for developing and emerging countries in 2022. This is the first time that the 100 billion target that developed countries exceeded the goals set for 2020 at COP15 in Copenhagen.

The money provided was 26.3 billion dollars higher than in 2021. However, there are unanswered questions about climate change adaptation, private funding, and the actual amount of climate financing. The OECD has recorded a decline in funding from multilateral climate funds.

“The growth in 2022 compared to 2021 is remarkable,” says Jan Kowalzig, climate finance expert at Oxfam. However, the level must be maintained and increased “to compensate for the under-fulfillment of the 100 billion targets accumulated in 2020 and 2021.” According to the OECD, countries are well on making up for this. “The significant increase in climate finance from private channels mobilized through public funds is particularly striking,” says David Ryfisch, Head of Sustainable Finance Flows at Germanwatch.

A new climate finance target (New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance – NCQG) for post-2025 will also be negotiated in Bonn. The big leap in fulfilling the 100 billion target could provide a tailwind.

However, Jan Kowalzig is unsure “how much of the 116 billion has actually contributed to climate action and adaptation, as the climate impact of some of the projects is often calculated too generously.” Although the figure is generally reliable, some projects with marginal climate impact are always included. The “big leap to 116 billion,” on the other hand, is most likely not the result of a “vague definition of climate action projects, but is probably due to actual growth.”

In 2022, 32.4 billion dollars flowed into the adaptation. This is also a new record. However, the share of adaptation funds, which should be approaching the 50 percent mark, of total spending decreased and is now only 28 percent of the 116 billion. In 2020, it was still at 34 percent. According to the OECD, developed countries are “about halfway towards meeting the call to double the provision of adaptation finance.”

This is where Kowalzig voices criticism: “In vulnerable countries in particular, this means that important programs for adapting livelihoods to climate change, securing harvests or protecting against disasters are either not being funded at all or only inadequately.” In addition, a lot of money flowed into several large adaptation projects in 2022. “It is unclear whether this is a one-off effect,” says Kowalzig, meaning whether the figure for 2022 is distorted or adaptation funding is moving permanently in the right direction.

Private funds saw the largest percentage jump. The developed countries could mobilize 21.9 billion dollars in private funds, 52 percent more than in 2021. “Firstly, the higher mobilization of private funds is very positive,” says Kowalzig. “However, there is no discernible trend for the future. The OECD does not explain the increase either.”

According to the OECD, the majority of private funds mobilized (48 percent) went to the energy sector. “This is also because renewable energies are becoming increasingly cheaper,” says David Ryfisch. “This means that public funds can better cushion residual investment risks.”

Bilateral and multilateral funds, for example, in the form of government grants or funds from development banks, account for the lion’s share of the 116 billion. Multilateral funds saw the biggest jump in absolute terms – from 38.7 billion to 50.6 billion. However, Ryfisch emphasizes that there is also “bad news” here: “The multilateral climate funds provided less climate financing than in the year before.” These funds are “particularly important for equitable climate financing” because developing countries have a say in how the funds are spent. “In 2023, for example, the Adaptation Fund fell well short of its mobilization target – i.e., the money provided by donors,” says Ryfisch.

The majority of public climate financing still flows in the form of loans. “This exacerbates the already overwhelming debt burden of many low-income countries,” Kowalzig from Oxfam criticizes. However, their share is decreasing slightly. In 2022, loans still accounted for more than 69 percent of public funding, compared to 74 percent in 2018.

Furthermore, 57 percent of private funds concentrated on just 20 recipient countries. According to the OECD, this is owed to large infrastructure projects requiring substantial funding. However, this uneven distribution of climate finance also includes multilateral and bilateral sources. 20 countries receive more funding from multilateral climate funds than the remaining 133 countries combined, the Boell Foundation criticizes.

57.6 billion dollars of the total amount went to low-income countries (11.1 billion) and low-middle-income countries (46.5 billion). The poorest countries receive the majority of the funds (64 percent) through grants. The low-middle-income countries saw the biggest jump.

“For the developed countries, the new figures naturally mean a lot of tailwind. They will argue that they have reached the 100 billion target,” says Jan Kowalzig from Oxfam. Achieving the target could also give new impetus to the debate about new donor countries. “Exceeding the 100 billion target – especially by 16 billion – takes the wind out of the sails of the countries that criticized developed countries for missing the 100 billion target,” says Ryfisch from Germanwatch. “China, the Gulf states and others can no longer retreat to the position that the developed countries should first meet their target before they themselves participate in international climate financing.”

According to reports, the negotiators want to publish concrete proposals for the NCQG for the first time in Bonn. However, many questions are still unclear:

ExxonMobil, the largest oil company in the United States, with a market capitalization of more than $500 billion, is hosting its annual shareholder meeting on Wednesday. In addition to internal issues, the company is currently engaged in a dispute with its own shareholders over its climate policy. The meeting ended after this issue of Climate.Table was published

The oil giant is facing a number of internal and external pressures. The company’s profits were down 28 percent in the first quarter of 2024 compared to the same time last year due in part to low natural gas prices and lower profits in oil refining.

Exxon is also in a messy legal fight with Chevron over the latter’s 53 billion US dollar acquisition of Hess Corporation. Exxon claims that under a prior agreement, it has the right of first refusal over Hess’s assets in Guyana, including a large offshore oil field. The case is currently under arbitration and the dispute may not conclude until next year.

But the biggest headache for Exxon at its shareholder meeting will likely be its own shareholders. The company went on the offensive earlier this year, suing two of its shareholders, Arjuna Capital and Follow This. The shareholder groups intend to bring climate-related measures to a vote at the meeting. They want to push the company to do more to mitigate climate change and limit its greenhouse gas emissions.

However, Exxon CEO Darren Woods said these groups were hijacking and abusing the voting process for publicly-traded companies. “These activists have no interest in the economic well-being of our company,” Woods said earlier this year at the CERAWeek by S&P Global energy conference in Houston, Texas.

The fight has exposed a rift among Exxon’s other stockholders. Officials from 19 states led by Republicans are urging investors to back Exxon’s management. Meanwhile, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) is urging Exxon to drop its lawsuits against Arjuna Capital and Follow This. CalPERs is the largest public pension fund in the US and has a 0.2 percent stake in Exxon.

Shareholders have succeeded in pushing Exxon on climate in the past. In 2017, they pressured the company to put a climate scientist, Susan Avery, on their board. However, Avery said earlier this year she would not stand for re-election to the post, and it’s not clear that Exxon is looking for another climate scientist to replace her. In 2021, investment firm Engine No. 1 managed to place two of its members on Exxon’s board to advocate for more action on climate change.

It’s hard to say whether these moves have led to any major shifts. Exxon’s oil production has been trending downward over the past decade, though it increased last year.

For its part, Exxon says that it’s doing more than ever to address climate change. Woods noted that he attended COP28 last year, marking the first time he’s been to an international climate negotiation meeting. Exxon began to publicly report its Scope 3 emissions in 2021, though the company has not committed to a reduction target. The company is now deploying carbon capture technology, preventing methane leaks, and developing hydrogen infrastructure, aiming to spend more than 20 billion US dollars between 2022 and 2027. Woods also praised the Inflation Reduction Act, the largest single US government investment to deal with climate change, because the law on paper is technology-neutral. “We’re going to need everything that works to drive emissions down,” Woods said.

But for Exxon, “everything” also includes more fossil fuels. The company is projecting that global oil and natural gas demand will continue to rise into the 2040s, so it’s counting on technologies like carbon capture to negate its impact on the climate and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

Environmental activists also note that Exxon understood its role in changing the global climate for decades, yet still sowed misinformation about warming and worked to block legislation behind the scenes. That track record makes it hard for climate campaigners to take Exxon’s climate work as a good-faith effort. That’s why they’re trying to flex their power as shareholders, to get into the rooms where decisions are made and force the company to make better ones for the climate.

June 2, Mexico

Elections Presidential elections in Mexico

Mexico is voting – and it is relatively certain that the country will have its first female president.

June 6-9

Elections European elections

The European Parliament elections will be held from June 6 to 9. Find all news, analyses and updates in our series on the European elections. Info

June 6-13, Bonn

Conference 60th Sessions of the UNFCCC Subsidiary Bodies

The SB60 conference of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) serves primarily as a preparatory conference for COP29 in November. Below we have compiled some highlights from the first few days. Info

June 3, Bonn

Conference Negotiations on NCQG

The negotiations on a New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance will be the focus of SB60 and COP29. Info

June 3, 11:45 a.m. CEST, Room Berlin

Side Event Water Resilient Food Systems

The SB60 side event, organized by the UNFCCC, aims to catalyze policy integration and foster stakeholder collaboration to actively promote water-resilient food systems while effectively addressing challenges related to climate change, desertification, and biodiversity conservation. Info

June 3, 1:15 p.m. CEST, Room Bonn

Side Event Operationalizing Article 6: A playbook for governments and crediting programmes

Over 50 countries have Article 6 agreements but the path to implementation is complex. Singapore, Verra and Gold Standard are launching a “playbook” with other countries to help standardize how governments and crediting programs can integrate robust carbon crediting into NDC implementation. Info

June 4, 4:15 p.m. CEST, Room Berlin

Side Event Making climate finance work for all: how to agree an ambitious NCQG

The event draws on new Alliance & ODI research providing a framework for burden sharing in the NCQG built on CBDR principle, ensuring developed countries provide their fair share and assessing the state of the contributor base while stressing the importance of a core of public grant-based finance. Info

June 6, 11:45 a.m. CEST, Room Berlin

Side Event Climate Justice and Gender Equality: Addressing the Intersectional Impacts of Climate Change

The event will foster collaboration among stakeholders – government, CSO, and faith-based groups – to boost gender-responsive resilience amidst climate-induced losses and damages. Info

June 7, Bonn

Briefing COP29 Presidential Briefing on Logistics

The COP 29 Logistics briefing will be held in Bonn in the Plenary New York, WCCB, Main Building. Info

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts that the Caribbean is in for a season with an exceptionally high number of hurricanes. The hurricane season between June 1 and November 30 could see up to 25 strong tropical cyclones, up to half of which forecasts predict could become hurricanes. An average season sees 14 tropical cyclones.

One of the main reasons is the already high ocean temperatures in the Atlantic, as the German newspaper FAZ explains. Currently, the water temperature in the area where hurricanes develop is around 1.3 degrees above average. This also means that the heat content of 41.8 kJ/cm² in the hurricane development area is at a record level at this time of year. Hurricanes draw their energy from the surface water, and the higher the temperatures, the higher the energy content. Heat contents of more than 40 kJ/cm² are generally not reached until the beginning of August. In addition to the high temperatures, the expected rapid change from El Niño to La Niña is another reason why the hurricane season is expected to be particularly active. kul

On Wednesday, the German Federal Cabinet passed a bill to enable the capture, storage and export of carbon dioxide in Germany. Compared to an earlier draft of the Carbon Capture and Storage Act (KSpG), the nature conservation requirements for potential carbon dioxide storage areas in the German North Sea have been tightened. For example, storage beneath marine conservation areas is now also to be ruled out if the borehole through which the CO₂ is to be injected is located outside these conservation areas. In addition, CCS drilling is also prohibited in an exclusion zone of eight kilometers around protected areas.

Environmental groups welcomed this amendment. “The BMUV has obviously made improvements,” commented energy expert Constantin Zerger from Environmental Action Germany. However, he also criticized the law’s provision empowering the Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action to lift the storage ban under marine conservation zones. However, according to the law, this is only possible if an evaluation proves beforehand that the storage capacities of the other marine areas in the German economic zone are not sufficient – which is unlikely in the coming years. Onshore storage will only be possible if a federal state authorizes it with its own law; given the massive protests in the past, this is also considered unlikely.

Environmental and climate protection organizations mainly criticize something else. Although the Ministry of Economic Affairs consistently emphasizes the importance of CCS for “difficult or unavoidable emissions” in its communication on the CSS Act, its use is not limited to industries such as cement or lime production. Instead, CCS is also permitted for carbon capture at gas-fired power plants, even though these emissions are not unavoidable and conversion to hydrogen is a better alternative from a climate perspective. In contrast, the law explicitly excludes the use of CCS at coal-fired power plants; the new draft clarifies that this also applies to combined heat and power plants.

“The use of carbon capture and storage in gas-fired power plants would harbor the massive risk of a fossil lock-in, making it extremely difficult to phase out natural gas-fired power generation,” Germanwatch expert Simon Wolf criticizes. “Carbon capture at power plants requires high initial investments, which are only profitable for operators if they can convert natural gas into electricity in the long term. However, this is incompatible with Germany’s climate targets.” Viviane Raddatz from WWF also calls for CCS to be ruled out for gas-fired power plants. The technology must be “limited to very few, currently unavoidable residual industrial emissions.”

Despite the approval, the Ministry of Economic Affairs is counting on the technology not being used there. This is because financial support for CCS has not yet been provided in this area. Without it, the technology would not have established itself on the market, said Economy Minister Robert Habeck at the presentation of the CCS key points in February. A recent FAQ paper from the Ministry is less clear: “According to the current status, much indicates that CCS will play a comparatively minor role in the energy sector.” The industry association BDEW also believes the question is still open. “The extent to which CCS can play a role for gas-fired power plants will depend on the costs, the infrastructure and the flexibility of the plants,” explained Managing Director Kerstin Andreae.

Whether the bill will pass the Bundestag in this form remains to be seen. The Free Democratic Party (FDP) has been pushing for the authorization of CCS for gas-fired power plants on the grounds of “technological openness.” The Social Democratic and The Green parliamentary groups, on the other hand, have so far rejected the use of CCS in the energy sector – and, therefore, also for gas-fired power plants.

Together with the CCS Act, the Cabinet also passed the Hydrogen Acceleration Act on Wednesday. It provides for significantly faster approval and planning processes for constructing hydrogen infrastructure. According to Habeck, this is “crucial for the decarbonization of industry.” Tobias Pforte-von Randow from the environmental umbrella organization DNR, however, criticized that the law “lumps together green and fossil hydrogen as well as simple electrolyzers and terminals for highly toxic ammonia.” mkr

The German government aims to develop a national action plan for green shipping. It will be drafted under the leadership of the Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport Affairs (BMDV) and the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK). The action plan will be developed in close cooperation with the maritime sector.

Last Tuesday, the areas covered by the action plan were presented at a presentation event at the Ministry of Transport:

The action plan is intended to support the transformation of the sector and strengthen its competitiveness and innovation expertise. The results will be presented at the upcoming National Maritime Conference planned for spring 2025. Last summer, the UN organization IMO, which is responsible for global shipping, decided that the global maritime industry must reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to zero by around 2050. Around three percent of global carbon emissions are caused by international shipping. dpa/kul

China’s carbon emissions fell by three percent in March compared to the same month last year. According to an analysis by the specialist service Carbon Brief based on official figures, the expansion of solar and wind energy, which accounted for 90 percent of the growth in electricity demand, was the main reason for the CO2 decline in March 2024. Another factor was the continued weak construction activity. As a result, steel production declined by eight percent and cement production by 22 percent in March 2024 year-on-year. Both sectors have extremely high carbon emissions. According to the report, oil demand also stalled in March.

Analyst Lauri Myllyvirta from the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air concluded that China’s emissions may have peaked. “A 2023 peak in China’s CO2 emissions is possible if the buildout of clean energy sources is kept at the record levels seen last year.” According to the official climate targets, Beijing only plans to reach this peak “by 2030.”

However, Myllyvirta says the downward trend is very recent. Emissions were still rising in January and February. But this also has to do with the comparison period: In January and February 2023, China’s economy was still pretty stagnant, and emissions with it. The post-Covid recovery did not kick in until March 2023, thus increasing the basis for the year-on-year comparison. ck

The potential of bicycles to help reduce Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions has been significantly underestimated so far. If its share of the traffic volume were increased from 13 percent to 45 percent, carbon emissions from local transportation could be reduced by 34 percent by 2035. However, if the current transport policy is maintained, this share would only increase from 13 to 15 percent. These are the findings of a study by the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research (Fraunhofer ISI), commissioned by the cycling club Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrrad-Club e.V. (ADFC).

The researchers have developed a model with three expansion stages for how Germany could establish itself as a cycling country. It provides for the following measures:

According to the study, the potential of bicycle traffic can only be fully exploited if these political measures are implemented. “If Germany is serious about achieving its climate targets and a high quality of life, the bicycle must be the new gold standard for everyday mobility,” says ADFC Federal Chairman Frank Masurat. By 2035, Germany could become a “world-leading ‘bicycle country plus’.”

The study found that there is still a lot of potential, especially in regional cities such as Karlsruhe or Göttingen. There, more than 60 percent of trips could be made by bicycle. Overall, a shift to bicycles could save 19 million tons of CO2 per year – which is equivalent to a third of emissions in local public transport. In comparison: According to the Federal Environment Agency, the transport sector caused 148 million tons of emissions in 2023. ag

Higher CO2 prices, stricter energy efficiency regulations and accelerated approval procedures for renewable energies are improving Europe’s energy security. A new report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) concludes that Europe’s commitment to climate action has had a positive impact on the continent’s energy independence.

Long before Russia launched its war of aggression against Ukraine, Europe “came to rely increasingly on imported energy from ever fewer suppliers.” The IMF analyzed that economic resilience to energy disruptions had been deteriorating for 13 years.

Europe’s climate legislation, the Fit for 55 package, reverses this decades-long deterioration in energy security. If the targets are met, energy security will improve by eight percent by 2030. If the climate action measures were also continued beyond 2030 as planned, this would result in further improvements, the authors write. luk

Despite rising carbon credit costs, the low-emission production of basic organic chemicals such as plastics, detergents, and paints will remain “considerably more expensive than with conventional processes” beyond 2045, according to a study by the Office of Technology Assessment at the German Bundestag (TAB). In the calculated low-carbon variants, basic chemicals are 26 to 50 percent more expensive than competing fossil-based products.

The main price drivers are the costs of green raw materials, particularly CO2-free hydrogen. In 2020, the production of basic organic chemicals caused around 4.5 percent of Germany’s industrial carbon emissions.

In the case of cement and steel, the study notes an earlier cost parity between conventional and low-carbon products. This point could be reached as early as 2030 for cement and 2035 for steel. In 2020, these two sectors emitted just under 38 percent of industrial carbon emissions in Germany.

The study estimates the additional investment required to decarbonize the three sectors at just under 15 billion euros. However, the German Cement Works Association recently calculated investment costs of 14 billion euros for a carbon pipeline network alone, through which carbon emissions, which are difficult to avoid in the cement sector, could be transported to underground storage facilities. av