In the debate about global climate financing, one question is hotly contested: Who, besides industrialized countries, should pay? The Global North argues that wealthy emerging and developing countries like China or the oil states, which have not participated so far, should also contribute. However, this premise is not entirely accurate, as surprising numbers and data we analyzed show: Almost all emerging countries are directly or indirectly engaged – and China is the eleventh largest donor for climate aid worldwide.

It’s also worth taking a closer look at financial data elsewhere: Oxfam has calculated how much of the 116 billion dollars in climate financing from wealthy countries actually counts as climate financing in the strict sense – and how much of it is granted to countries as subsidies or merely as loans. The result is sobering. Similarly, a look behind the scenes at the investments of institutional investors in fossil projects reveals that reality often looks worse than the advertising promises.

But this issue also offers signs of hope: We show how science is trying to reduce its own CO2 footprint. And new data suggests a trend: While there are more and more cars in Germany, they are being driven less. Bad news for the search for parking spaces, but potentially good news for the climate.

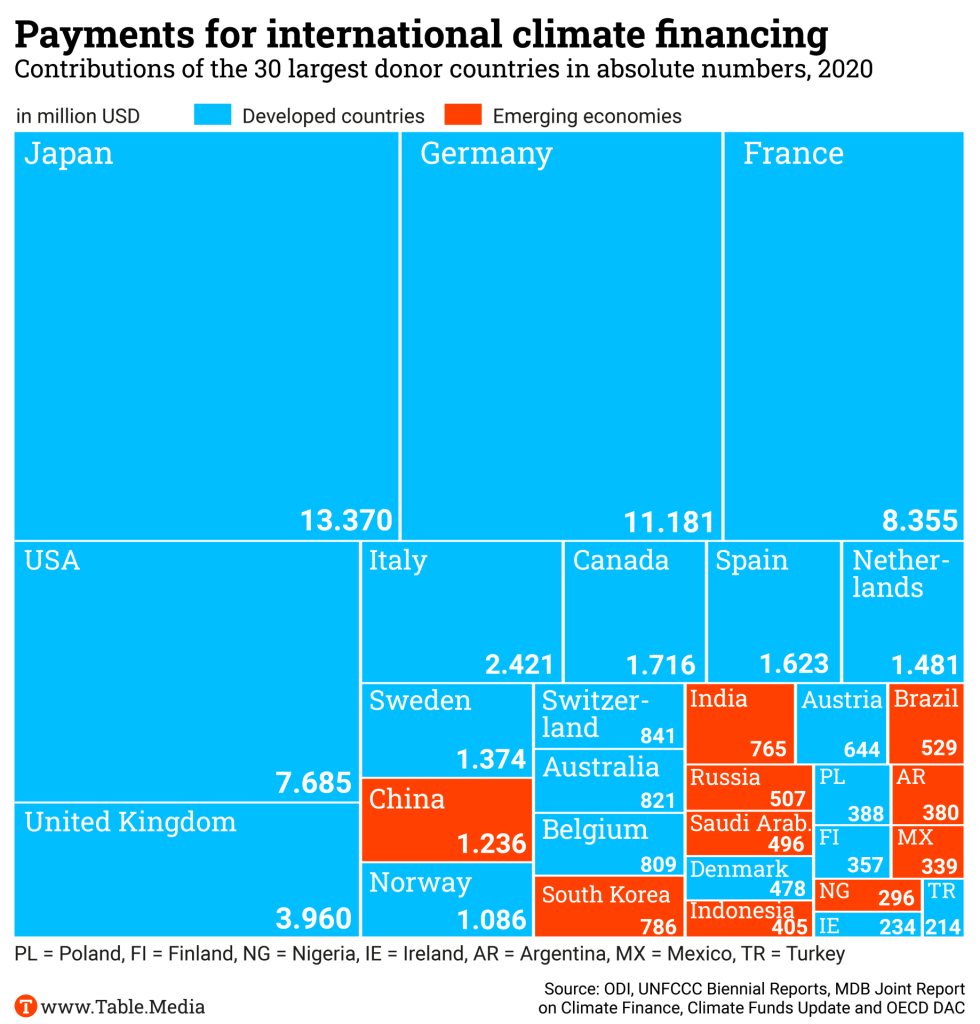

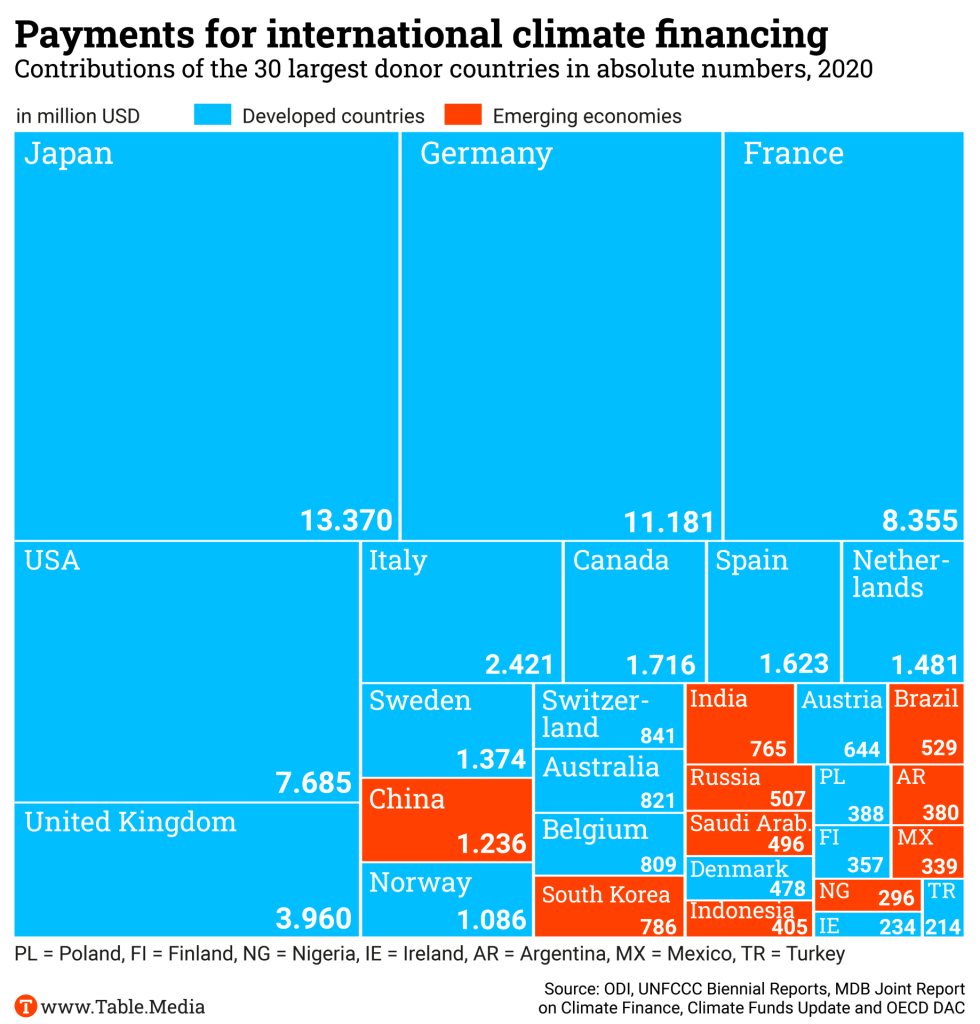

Emerging markets such as China, India and Brazil are contributing significantly more to the international financing of climate action measures than generally assumed. For example, a study shows that in 2020, China paid more than two billion US dollars in climate aid to other countries in the Global South, both directly and indirectly. Other G77 countries contribute hundreds of millions. This is according to an extensive study by the renowned British think tank Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

According to the study, the top ten contributors to climate financing (data from 2020) are industrialized countries, led by Japan, Germany, France and the USA. But China already ranks eleventh with 1.2 billion US dollars in direct payments. South Korea follows in 16th place, then India, Brazil, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Argentina, Mexico and Nigeria among the top 30.

These figures are particularly relevant because UN states want to agree on a new common goal for climate financing (NCQG) at COP29 in Baku. The topic of finance will also play a central role at the G20 Task Force meeting on Global Mobilization against Climate Change in Belém, Brazil, on July 11-12. So far, only industrialized countries have committed to international climate action payments. The 100 billion US dollars per year promised at COP21 from 2020 onwards were first reached and exceeded in 2022 with 116 billion, according to OECD calculations.

Due to the enormous financial needs for the NCQG from 2025 – estimates suggest about 2.4 trillion US dollars annually between 2026 and 2030 – industrialized countries are pushing for other nations to participate. The EU and the USA have repeatedly called on countries like China or the oil states to also contribute – something these countries have so far refused, arguing that they are not obliged and that the Global North has not fulfilled its promises.

There are no official figures on the financial flows from emerging markets because under the climate framework convention, only industrialized countries are required to disclose their financial flows for financing, technology transfer and capacity building in poor countries. A study by the organization E3G estimates that China contributed over a billion US dollars annually between 2013 and 2017 in bilateral projects with countries in the Global South, including public and private investments and aid payments mainly through the “New Silk Road” in the areas of energy, transportation, water, agriculture and disaster protection. However, climate payments account for only about two percent of total “Silk Road” investments, and only about ten percent of the targeted 3.1 billion for a special fund for South-South cooperation flowed in the first seven years. Nevertheless, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) under Chinese control has announced plans to triple its climate financing to seven billion US dollars annually by 2030.

The ODI study adds to the direct payments China’s contributions to international climate funds (one million) and multilateral development banks (678 million) like the World Bank – totaling just over two billion US dollars. According to the study, “China would rank as the seventh-largest payer of international climate finance in 2017, after Japan, Germany, France, the USA, the UK and Italy,” the authors conclude. Actual payments tend to be underestimated due to the lack of official data. Countries in the Global South do not officially disclose the size of their aid contributions. China, for example, has not officially promoted its payments, though Chinese representatives do mention these contributions in UN negotiations behind closed doors, according to negotiators.

Pressure on China is increasing ahead of COP29. The G77 states’ front against financial contributions was first broken at COP28 by the host United Arab Emirates, which, along with Germany, promised 100 million US dollars each for the Loss and Damage Fund. Even before that, poorer G77 countries had called on China to pay: at COP27, the AOSIS chair Antigua and Barbuda urged India and China to contribute. Ghana also expects China to be a payer.

ODI experts estimate total South-South cooperation from state funds at around 3.2 billion US dollars for 2020. “Practically all countries have contributed to climate finance through their voluntary contributions to development banks,” they say. Another 33 non-Annex II countries [non-OECD countries, editor’s note] have paid into multilateral climate funds. A per capita calculation of these contributions brings some new countries into the top 5: Monaco, Nauru, Norway, Tuvalu and Germany.

Science impacts the climate. Depending on the discipline, the individual “CO2 footprint” of researchers can be considerably larger than that of an average German citizen, which the Federal Statistical Office estimates at around eight tons per year (2020 data). Air travel is a significant contributor, as is the high electricity consumption of data centers, modeling and working with AI systems. Large infrastructures that require a lot of steel and concrete also negatively affect the climate balance.

A team led by Jürgen Knödlseder from the University of Toulouse calculated this using astronomers as an example. For the construction and operation of telescopes like “ALMA” or “La Silla”, as well as space-based observatories like “Hubble”, they come to a greenhouse gas emission of 37 tons per year per researcher, with a significant fluctuation range of 14 tons.

Climate action and sustainability are becoming increasingly important for the communities. The major research organizations have also set corresponding goals. For example, Fraunhofer aims to reduce its organization’s emissions by 55 percent by 2030 compared to 2020, and Fraunhofer aims to operate climate-neutrally by 2045. The Max Planck Society recently committed to halving its greenhouse gas emissions by 2029 compared to 2019. Many Helmholtz centers have set a timeline for when they want to achieve climate neutrality. These range from KIT Campus North (by 2030) to DLR, HZB, and DKFZ (2035) to MDC (2038) and GFZ (between 2030 and 2040).

The measures mentioned upon request by Table.Briefings are similar:

The goals of the organizations are ambitious, as is often heard from the institutes. They are also partly in a dilemma: They are researching solutions for a sustainable society, which include improved solar panels and batteries or climate-friendly aviation. Yet, this research still requires energy-intensive infrastructures today.

Short-term effective measures have largely been implemented, explains the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. The next steps are particularly challenging, especially regarding the transformation of properties, such as energy-efficient renovations, sustainability in the construction process, and new financing mechanisms. “For many of these projects, we need external support to improve our framework conditions. We are in a constructive discussion process with policymakers and funding bodies to accelerate renovation processes and simplify the corresponding rules. Such simplifications are necessary to complete our roadmap on time and achieve the climate goal in time.”

While the heads of institutes and organizations deal with the big lines of climate action, this does not absolve individual employees of their responsibility, says Jürgen Gerhards, a macrosociologist at FU Berlin. He has mainly focused on travel-related CO2 emissions. Under his leadership, the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities and the Young Academy published a paper in 2022 titled “Climate Action and Business Travel: Recommendations for Environmentally Friendly Travel Behavior in Science.”

In an interview with Table.Briefings, he differentiates between the motives and arguments of “insane” frequent flying. The motive, says Gerhards, is the desire to travel. A conference in Istanbul invites you to extend the weekend for private exploration. “This is promoted by providers who earn money with conferences. And because the individual researcher does not have to pay for this themselves but through third-party funds.” The argument is networking and exchange, which are important. “That is only partly true. You can easily reduce 60 percent of flight activities without any harm,” says Gerhards. Virtual meetings also have strong advantages: Parents of small children are not away for as long, and especially colleagues from the Global South, who sometimes have significant problems obtaining visas, can better participate in joint projects.

A special incentive to avoid flying is practiced at the University of Konstanz. It is voluntary for all working groups that want to participate. A fee is charged for each flight, which goes into a fund. At the end of the year, the “profit” is distributed, half going to all participating working groups, the other half depending on the reduction compared to a reference year in the individual groups. About two-thirds of the working groups participate, says Konstanz microsociologist Claudia Diehl, who is significantly involved in the project. She considers this a good sign. For her, it is crucial that the model was developed from within the university and not imposed by the administration. Her motivation: “If we can’t manage to act more sustainably at the university, how is society supposed to succeed?”

Similarly, astronomer Jörn Wilms from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg expresses this. He sees his field, with its pronounced internationalization and large infrastructures, as a suitable study object to show how to still conduct sustainable science. “Many meetings are now offered virtually or hybrid,” he says. In addition, consideration is given to where the participants come from, and a geographically convenient location is sought. Wilms also sees obstacles due to administrative requirements. “When procuring instruments, we are bound to the cheapest supplier, but they are mostly in the Far East,” he says. “The transports are an ecological disaster.”

Wilms is currently involved in a new edition of the “Astronomy Memorandum”, in which the professional community agrees on important goals. According to him, it should be clearly demanded there to also calculate a CO2 impact for projects. With this, the researcher hopes to create awareness among politicians and funding bodies for climate action possibilities: From climate-friendly concrete under telescopes to software improvements that make data processing more efficient and thus save energy.

Oxfam identifies only 35 billion dollars from international climate finance as actual support for poorer countries. According to Oxfam, more than two-thirds of the 116 billion dollars paid by industrialized countries in 2022 for climate finance, as reported by the OECD, cannot be considered genuine support. This is because they either need to be repaid or lack a clear climate focus.

Oxfam calculates genuine support by analyzing grants and interest concessions from climate finance loans. In contrast, the official OECD data includes the portion of loans given at market rates, which recipient countries are required to repay. Oxfam does not count this portion. It also estimates the proportion of climate finance that truly benefits climate efforts. According to Oxfam, their standards are “stricter, but not dramatically stricter” than those used by donor countries in their reporting.

In 2021, genuine support amounted to 25 billion dollars, while official OECD figures reported 89 billion dollars in climate finance.

Currently, there is no unified standard for reporting climate finance under the Paris Agreement. While the agreement encourages donor countries to voluntarily disclose the grant-equivalent portion of their climate finance, industrialized nations have strongly resisted mandatory reporting, according to Oxfam. Increased transparency and uniform reporting standards are crucial for the new Climate Finance Goal (NCQG), Oxfam emphasizes. nib

According to the EIB survey, Germans aged over 50 are more familiar with the causes, effects and potential solutions of climate change compared to younger demographics. Specifically, Germans aged 20 to 29 scored lower than those over 30. Moreover, compared to their peers in other EU countries, young Germans aged 20 to 29 performed less well.

Three-quarters of Germans attribute the main causes of climate change to “human activities such as deforestation, agriculture, industry and transportation”. The remainder attribute it to “extreme natural events such as volcanic eruptions and heatwaves” or to the ozone hole.

Regarding climate change mitigation measures, the EIB found differing perspectives. For instance, 43 percent of Germans surveyed believe that “lower speed limits on roads can mitigate climate change”, compared to a European average of 26 percent. Additionally, only a slim majority (53 percent, compared to 42 percent EU-wide) recognize that better-insulated buildings can help combat climate change.

In the EIB’s climate change knowledge test, which surveyed 30,000 people across 35 countries (EU, UK, USA, China, Japan, India and Canada), Germany ranks 10th among EU member states, slightly above the EU average. Finland, Luxembourg and Sweden performed the best. luk

The new Labour government in the UK plans to simplify the planning process for onshore wind turbines and eliminate two barriers that have severely restricted their expansion since 2015. The new Energy Minister, Ed Miliband, announced on Monday that:

The Labour government aims to double onshore wind capacity by 2030. Since 2017, the addition of new onshore wind turbines has declined sharply. nib

Currently, institutional investors have 4.3 billion dollars invested in bonds and stocks of companies involved in fossil energy projects. This amount comes from the financial research report “Investing in Climate Chaos“, conducted by the German NGO Urgewald and 13 partner organizations. The databases “Global Exit Coal List” and “Global Oil and Gas Exit List” list 7,500 institutional investors, including pension funds, insurers, asset managers, hedge funds, sovereign funds, foundation funds, and asset management subsidiaries of commercial banks.

Vanguard and Blackrock from the USA are significantly leading, each investing over 400 billion dollars in oil, gas, and coal businesses. Among the top ten largest investors listed by Urgewald, eight are based in the United States. Overall, more than 65 percent of investments in the compilation are from US companies.

“This demonstrates that US regulatory authorities have so far failed to effectively monitor and address the climate and transformation risks of major institutional investors,” said Alec Connon of the Stop the Money Pipeline campaign.

Germany ranks 10th globally. The largest German investor is Deutsche Bank with 25 billion dollars, ranked 30th on the global investor list, primarily due to its nearly 80 percent stake in DWS Asset Management. According to Urgewald, DWS continues to hold shares worth over 1 billion dollars in companies in this sector, despite its own coal policy.

A DWS spokesperson referred to the annual review of the coal policy when queried by Table.Briefings. DWS aims for a “complete cessation of coal use” in the EU and OECD countries by 2030, extending to all other countries by 2040.

German involvement in oil and gas is even greater, with Deutsche Bank and DWS together investing 23 billion dollars, closely followed by the Allianz Group and its subsidiaries Pimco and AGI. Urgewald criticizes investments, especially in ExxonMobil, which is expanding its fossil fuel operations and has sued activist shareholders proposing a change in direction.

The DWS spokesperson declined to comment on individual portfolio companies but stated that the company endeavors to “use our voting rights accordingly or express ourselves publicly at the respective annual general meetings in cases where we do not see progress through dialogue.” Ultimately, such companies could also be removed from “certain” product portfolios. av

In 2023, there were seven percent fewer cars on German highways compared to 2019, a trend observed in many major cities as well. Additionally, the traffic volume of long-distance trains increased by six percent. These findings are from an analysis conducted by the think tank Agora Verkehrswende, based on a report by the consulting firm KCW.

While the number of registered vehicles has significantly increased from 2019 to 2023, the study attributes the decrease in car traffic to several factors, including a decline in commuting between home and work post-pandemic. More people are now working at least partially from home. Furthermore, initiatives such as the introduction of the Germany Ticket and the rise in CO2 prices on fossil fuels have played roles.

Despite a slight increase in population and a steadily growing number of registered cars, car traffic has decreased compared to 2019, noted Wiebke Zimmer, Deputy Director of Agora Verkehrswende. “Traffic growth is not inevitable.” Public transportation, particularly rail travel, has seen an increase. While bus travel has seen fewer kilometers traveled compared to pre-pandemic levels, rail and train journeys have increased. Although there are currently fewer passengers than before the pandemic, they are traveling longer distances.

Agora Verkehrswende advocates for political support to sustain these positive trends. Measures could include:

With a “Power Plant Security Act” (KWSG), the Ministry for Economic Affairs aims to implement the construction of new climate-friendly power plants in several phases to ensure supply security. Overall, the government, with EU approval, can subsidize the construction of 12.5 GW of power plant capacity. This was announced by Economy Minister Robert Habeck following the government’s agreement on the federal budget for 2025. The new law is intended to prepare a capacity market for power plants that will regulate short-term power plant capacity offerings in the future.

The law is based on two pillars:

According to DUH’s survey, 186 out of 252 surveyed politicians use official vehicles emitting “significantly above the European fleet average of 95 g CO2/km”. Justice Minister Marco Buschmann (FDP), Education Minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger (FDP) and Transport Minister Volker Wissing (FDP) top the list with the most climate-damaging official vehicles, emitting between 184 and 205 g CO2/km. NRW Minister President Hendrik Wüst (CDU) and Berlin’s Regierender Bürgermeister Kai Wegner (CDU) fare even worse, emitting between 375 and 380 g CO2/km, according to DUH.

The most climate-friendly vehicles are driven by Development Minister Svenja Schulze (SPD) and Family Minister Lisa Paus (Grüne), whose vehicles emit less than 100 g CO2/km. DUH also notes positively that “the share of battery-electric official vehicles has increased to 34 percent“. Four out of nine federal ministers included in the survey drive fully electric vehicles: Schulze, Paus, Umweltministerin Steffi Lemke (Grüne) and Landwirtschaftsminister Cem Özdemir (Grüne). However, according to DUH, these EVs are often “grossly oversized” and consume a lot of electricity.

Criticism has been directed at the survey methodology. DUH assumes, for example, that plug-in hybrids are operated solely in combustion mode. Studies suggest this is often the case, but whether top politicians and their fleet managers actually follow this practice remains unclear. Additionally, some politicians have multiple official vehicles, but DUH only lists the vehicle with the highest emissions. The analysis also excludes many heavily armored official vehicles from evaluation. nib/dpa

The German government currently has no financing concepts for the multi-billion euro decarbonization of two-thirds of the German steel industry. This is according to the government’s response to a small inquiry from the Left party, as seen by Table.Briefings. So far, major steel companies have been provided with nearly seven billion euros in subsidies for the conversion. This is intended to replace one-third of the blast furnaces with electricity and hydrogen-based production facilities.

The remaining fossil-based steel capacities are to be decarbonized by 2045. The industry estimates an additional investment requirement of 20 billion euros for this. “Other ways of financing” need to be found for this, writes the government, “for example, by identifying additional (private) financing instruments“.

“The government does not know how to close the existing financing gap,” commented Left party MP Jörg Cézanne. He fears that without state funding, production capacities will be reduced. Therefore, “a clear political commitment to steel production in Germany, which must also be financially supported,” is needed.

State involvement in the steel transformation does not result from the subsidies. For instance, Thyssenkrupp’s steel subsidiary is planning to reduce capacities and jobs despite significant state funding. For new funding programs like “climate action contracts”, applicants must now make commitments or agreements with employee representatives to secure jobs.

“The concept of further funding with climate action contracts is right and important,” said Tilman von Berlepsch, climate-neutral industry advisor at the NGO Germanwatch. However, “continuity and reliability” in funding are needed “so that companies can invest and the survival of key industries with good unionized jobs can be ensured”. av

Following the 2019 European Parliament elections, Brussels was focused on climate action. Sustainability and transformation were the dominant themes. Von der Leyen’s response: The Green Deal. Five years later, everything seems different. Concerns about security, migration and deindustrialization are at the forefront. From a corporate perspective, however, the answer remains the same: The Green Deal must be continued and complemented by a green industrial deal. Otherwise, Europe’s industry risks falling behind.

According to MIT, $265 billion flowed into green technologies in the USA in 2023. This marked a 40 percent increase from the previous year when Joe Biden passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). $40 billion in state funds triggered $220 billion in private investments. Employment numbers rose, growth rates climbed and key technology development received a significant boost. This is expected to significantly enhance the country’s independence, resilience and security in the future.

Security, growth, climate action – a triad that Ursula von der Leyen also desires for her re-election to the EU Parliament on July 18. She must accommodate her alliance of the EPP, Social Democrats and Liberals and strengthen it with additional votes from the Greens or the ECR. The EU Council’s agreed agenda clearly focuses on security and competitiveness, points that could be well combined with a green industrial deal.

From the perspective of the Foundation for Climate Economy, a green industrial deal must focus on achieving climate targets. The planned interim climate target for 2040 plays a crucial role in guiding the path towards climate neutrality. Top priority must be given to the expansion of renewables, electrolyzers and networks. Alongside an integrated electricity market and a pragmatic approach to hydrogen ramp-up (better blue than nothing), this could alleviate high energy prices in the EU. It would also be beneficial for companies to have relief from reporting and due diligence obligations that tie up many resources.

However, none of this is possible without money. According to estimates by the Commission, achieving climate neutrality requires an investment surplus of more than $620 billion per year. Private capital could cover much of this, making the swift finalization of the European Capital Markets Union urgently necessary. The same applies to introducing a transformation category within the sustainable finance framework. Currently, investment goals are only labeled green if they are already low in CO2 emissions. To mobilize more capital for transformation, there also needs to be a label for companies with CO2 emissions and ambitious reduction strategies. Otherwise, industry will miss out on green capital providers.

On the other hand, when it comes to infrastructure spending, the transformation will also require government grants. For example, in the form of European climate action contracts that can cover start-up funding and operating costs to make green technologies directly competitive. If green leading markets are added, establishing an anticipated demand for clean technologies from the EU, a similar dynamic to that in the USA could unfold in Europe as well. Those looking to make their location fit for the challenges of the 21st century must invest heavily in industrial transformation rather than taking small steps. The IRA has set the example.

Sabine Nallinger is the CEO of the Foundation for Climate Economy, an independent CEO initiative promoting corporate climate action in Germany.

Özden Terli – Editor and presenter, ZDF weather department

Özden Terli is one of Germany’s most prominent weather forecasters. As an editor and presenter at the ZDF Weather Department, Terli is well-known to a broad audience. For many years, he has interpreted weather reports not just as information about sunshine and rain, but as science communication. The meteorology graduate educates his audience about the connections and consequences of the climate crisis in his show. He often faces backlash from the right-wing spectrum, attempting to silence him. According to Terli, many people, especially industry representatives, are more advanced than parts of the politics, which he claims are less focused on solving the climate crisis and more on distracting with non-issues.

Simon Evans – Deputy Editor, Carbon Brief

As the deputy editor of the specialized newsletter Carbon Brief, Simon Evans is among the world’s most important climate journalists. His areas of focus include British climate policy, international climate diplomacy, and myths surrounding electric vehicles. In 2022, Evans won the Press Gazette’s British Journalism Awards in the “Energy and Environment” category. He studied chemistry at the University of Oxford and later earned a doctorate in biochemistry from the University of Bristol.

Greta Thunberg – Swedish climate activist

She remains the global icon of the climate movement, although now controversial. As the founder of Fridays for Future, Greta Thunberg directed global attention to combating climate change in 2019, inspiring an entire generation of youth and prompting politics and business to engage constructively and proactively in effective climate action. She now primarily uses her prominence to draw attention to the war and suffering in Gaza. Thunberg has faced criticism for her anti-Israeli positions, which some argue stoke antisemitic sentiments.

Sven Egenter – Journalist and Editor-in-Chief, Clean Energy Wire

Sven Egenter is a journalist and managing director of the 2050 Media Projekt gGmbH, overseeing media projects like Clean Energy Wire (CLEW) and Climate Facts, focusing on energy and climate issues and connecting journalists in this field. Egenter spent twelve years with the Reuters news agency in Germany, the UK and Switzerland.

Vanessa Nakate – Ugandan climate activist

Ugandan activist Vanessa Nakate is a role model for the climate movement in Africa. She consistently highlights the injustices of Western policies, particularly regarding climate change. Nakate founded “Youth for Future Africa” and the African “Rise Up Movement”, advocating for rainforest protection in the Congo Basin. As a committed Christian, she criticizes neocolonial tendencies and calls for support for poorer nations in climate change mitigation, adaptation and compensation for damages and losses.

Ed King – Communications Director, Global Strategic Communication Council (GSCC)

Ed King is one of the most influential communicators in the international climate scene. At the GSCC think tank, he oversees strategic communication, synthesizing information from politics, media, UN bodies, business, science and NGOs in London. He crafts monthly or (during COPs) daily briefings providing critical insights for observers, negotiators and journalists to accelerate political decisions for climate action. King began his career as a reporter at the BBC and was among the founders of the climate website “Climate Home News“. He often enhances his analyses with parallels from the world of sports.

Ingmar Rentzhog – Founder and Chairman, “We dont have time”

Ingmar Rentzhog founded and leads the Swedish online platform “We don’t have time”, touted as the world’s largest media platform for climate action, spreading and discussing climate solutions and new ideas globally. Rentzhog studied mathematics and management and worked in financial consulting. He was a member of the Climate Reality Project, an advocacy organization founded by former US Vice President Al Gore. Since 2016, Rentzhog and his team from Stockholm have provided a platform for global climate discussions and enabled businesses to engage in economic and social innovations. The webcasts of “We don’t have time,” particularly during SB60 in Bonn, garnered 8.7 million views.

Carlos Nobre – Scientist

Brazilian scientist Carlos Nobre is a pioneer in research on the link between deforestation and climate warming, particularly focusing on the Amazon rainforest. He earned his doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and worked for over 35 years at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). Nobre was a lead author of various IPCC reports, including the 2007 report that received the Nobel Peace Prize. In an interview with Table.Media, he discussed the EU’s responsibility for deforestation in the rainforest.

Jenny Chase – Solar Analyst, Bloomberg NEF

Since 2005, Jenny Chase has worked as a solar analyst at Bloomberg NEF, a think tank providing data and analyses on the energy transition. Chase is one of the most respected observers of the solar sector, developing key economic and financial concepts on trade issues, price mechanisms and the integration of solar panels and batteries. She updated her book “Solar Power Finance Without the Jargon” in early 2024. Chase studied physics and natural sciences at the University of Cambridge.

Luisa Neubauer – Climate activist

Luisa Neubauer, 28, is the most prominent face of the climate movement in Germany. She gained fame through the Fridays for Future climate strikes in 2019. Neubauer has been a member of the Greens since 2017, though she claims to be inactive. Recently, she has faced challenges as the international climate justice movement clashed with Fridays for Future in Germany over their stance on the Gaza conflict. FFF in Germany is also fighting not to lose relevance. Personally, Neubauer endures a lot: She frequently experiences hate and sexist attacks.

In the debate about global climate financing, one question is hotly contested: Who, besides industrialized countries, should pay? The Global North argues that wealthy emerging and developing countries like China or the oil states, which have not participated so far, should also contribute. However, this premise is not entirely accurate, as surprising numbers and data we analyzed show: Almost all emerging countries are directly or indirectly engaged – and China is the eleventh largest donor for climate aid worldwide.

It’s also worth taking a closer look at financial data elsewhere: Oxfam has calculated how much of the 116 billion dollars in climate financing from wealthy countries actually counts as climate financing in the strict sense – and how much of it is granted to countries as subsidies or merely as loans. The result is sobering. Similarly, a look behind the scenes at the investments of institutional investors in fossil projects reveals that reality often looks worse than the advertising promises.

But this issue also offers signs of hope: We show how science is trying to reduce its own CO2 footprint. And new data suggests a trend: While there are more and more cars in Germany, they are being driven less. Bad news for the search for parking spaces, but potentially good news for the climate.

Emerging markets such as China, India and Brazil are contributing significantly more to the international financing of climate action measures than generally assumed. For example, a study shows that in 2020, China paid more than two billion US dollars in climate aid to other countries in the Global South, both directly and indirectly. Other G77 countries contribute hundreds of millions. This is according to an extensive study by the renowned British think tank Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

According to the study, the top ten contributors to climate financing (data from 2020) are industrialized countries, led by Japan, Germany, France and the USA. But China already ranks eleventh with 1.2 billion US dollars in direct payments. South Korea follows in 16th place, then India, Brazil, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Argentina, Mexico and Nigeria among the top 30.

These figures are particularly relevant because UN states want to agree on a new common goal for climate financing (NCQG) at COP29 in Baku. The topic of finance will also play a central role at the G20 Task Force meeting on Global Mobilization against Climate Change in Belém, Brazil, on July 11-12. So far, only industrialized countries have committed to international climate action payments. The 100 billion US dollars per year promised at COP21 from 2020 onwards were first reached and exceeded in 2022 with 116 billion, according to OECD calculations.

Due to the enormous financial needs for the NCQG from 2025 – estimates suggest about 2.4 trillion US dollars annually between 2026 and 2030 – industrialized countries are pushing for other nations to participate. The EU and the USA have repeatedly called on countries like China or the oil states to also contribute – something these countries have so far refused, arguing that they are not obliged and that the Global North has not fulfilled its promises.

There are no official figures on the financial flows from emerging markets because under the climate framework convention, only industrialized countries are required to disclose their financial flows for financing, technology transfer and capacity building in poor countries. A study by the organization E3G estimates that China contributed over a billion US dollars annually between 2013 and 2017 in bilateral projects with countries in the Global South, including public and private investments and aid payments mainly through the “New Silk Road” in the areas of energy, transportation, water, agriculture and disaster protection. However, climate payments account for only about two percent of total “Silk Road” investments, and only about ten percent of the targeted 3.1 billion for a special fund for South-South cooperation flowed in the first seven years. Nevertheless, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) under Chinese control has announced plans to triple its climate financing to seven billion US dollars annually by 2030.

The ODI study adds to the direct payments China’s contributions to international climate funds (one million) and multilateral development banks (678 million) like the World Bank – totaling just over two billion US dollars. According to the study, “China would rank as the seventh-largest payer of international climate finance in 2017, after Japan, Germany, France, the USA, the UK and Italy,” the authors conclude. Actual payments tend to be underestimated due to the lack of official data. Countries in the Global South do not officially disclose the size of their aid contributions. China, for example, has not officially promoted its payments, though Chinese representatives do mention these contributions in UN negotiations behind closed doors, according to negotiators.

Pressure on China is increasing ahead of COP29. The G77 states’ front against financial contributions was first broken at COP28 by the host United Arab Emirates, which, along with Germany, promised 100 million US dollars each for the Loss and Damage Fund. Even before that, poorer G77 countries had called on China to pay: at COP27, the AOSIS chair Antigua and Barbuda urged India and China to contribute. Ghana also expects China to be a payer.

ODI experts estimate total South-South cooperation from state funds at around 3.2 billion US dollars for 2020. “Practically all countries have contributed to climate finance through their voluntary contributions to development banks,” they say. Another 33 non-Annex II countries [non-OECD countries, editor’s note] have paid into multilateral climate funds. A per capita calculation of these contributions brings some new countries into the top 5: Monaco, Nauru, Norway, Tuvalu and Germany.

Science impacts the climate. Depending on the discipline, the individual “CO2 footprint” of researchers can be considerably larger than that of an average German citizen, which the Federal Statistical Office estimates at around eight tons per year (2020 data). Air travel is a significant contributor, as is the high electricity consumption of data centers, modeling and working with AI systems. Large infrastructures that require a lot of steel and concrete also negatively affect the climate balance.

A team led by Jürgen Knödlseder from the University of Toulouse calculated this using astronomers as an example. For the construction and operation of telescopes like “ALMA” or “La Silla”, as well as space-based observatories like “Hubble”, they come to a greenhouse gas emission of 37 tons per year per researcher, with a significant fluctuation range of 14 tons.

Climate action and sustainability are becoming increasingly important for the communities. The major research organizations have also set corresponding goals. For example, Fraunhofer aims to reduce its organization’s emissions by 55 percent by 2030 compared to 2020, and Fraunhofer aims to operate climate-neutrally by 2045. The Max Planck Society recently committed to halving its greenhouse gas emissions by 2029 compared to 2019. Many Helmholtz centers have set a timeline for when they want to achieve climate neutrality. These range from KIT Campus North (by 2030) to DLR, HZB, and DKFZ (2035) to MDC (2038) and GFZ (between 2030 and 2040).

The measures mentioned upon request by Table.Briefings are similar:

The goals of the organizations are ambitious, as is often heard from the institutes. They are also partly in a dilemma: They are researching solutions for a sustainable society, which include improved solar panels and batteries or climate-friendly aviation. Yet, this research still requires energy-intensive infrastructures today.

Short-term effective measures have largely been implemented, explains the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. The next steps are particularly challenging, especially regarding the transformation of properties, such as energy-efficient renovations, sustainability in the construction process, and new financing mechanisms. “For many of these projects, we need external support to improve our framework conditions. We are in a constructive discussion process with policymakers and funding bodies to accelerate renovation processes and simplify the corresponding rules. Such simplifications are necessary to complete our roadmap on time and achieve the climate goal in time.”

While the heads of institutes and organizations deal with the big lines of climate action, this does not absolve individual employees of their responsibility, says Jürgen Gerhards, a macrosociologist at FU Berlin. He has mainly focused on travel-related CO2 emissions. Under his leadership, the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities and the Young Academy published a paper in 2022 titled “Climate Action and Business Travel: Recommendations for Environmentally Friendly Travel Behavior in Science.”

In an interview with Table.Briefings, he differentiates between the motives and arguments of “insane” frequent flying. The motive, says Gerhards, is the desire to travel. A conference in Istanbul invites you to extend the weekend for private exploration. “This is promoted by providers who earn money with conferences. And because the individual researcher does not have to pay for this themselves but through third-party funds.” The argument is networking and exchange, which are important. “That is only partly true. You can easily reduce 60 percent of flight activities without any harm,” says Gerhards. Virtual meetings also have strong advantages: Parents of small children are not away for as long, and especially colleagues from the Global South, who sometimes have significant problems obtaining visas, can better participate in joint projects.

A special incentive to avoid flying is practiced at the University of Konstanz. It is voluntary for all working groups that want to participate. A fee is charged for each flight, which goes into a fund. At the end of the year, the “profit” is distributed, half going to all participating working groups, the other half depending on the reduction compared to a reference year in the individual groups. About two-thirds of the working groups participate, says Konstanz microsociologist Claudia Diehl, who is significantly involved in the project. She considers this a good sign. For her, it is crucial that the model was developed from within the university and not imposed by the administration. Her motivation: “If we can’t manage to act more sustainably at the university, how is society supposed to succeed?”

Similarly, astronomer Jörn Wilms from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg expresses this. He sees his field, with its pronounced internationalization and large infrastructures, as a suitable study object to show how to still conduct sustainable science. “Many meetings are now offered virtually or hybrid,” he says. In addition, consideration is given to where the participants come from, and a geographically convenient location is sought. Wilms also sees obstacles due to administrative requirements. “When procuring instruments, we are bound to the cheapest supplier, but they are mostly in the Far East,” he says. “The transports are an ecological disaster.”

Wilms is currently involved in a new edition of the “Astronomy Memorandum”, in which the professional community agrees on important goals. According to him, it should be clearly demanded there to also calculate a CO2 impact for projects. With this, the researcher hopes to create awareness among politicians and funding bodies for climate action possibilities: From climate-friendly concrete under telescopes to software improvements that make data processing more efficient and thus save energy.

Oxfam identifies only 35 billion dollars from international climate finance as actual support for poorer countries. According to Oxfam, more than two-thirds of the 116 billion dollars paid by industrialized countries in 2022 for climate finance, as reported by the OECD, cannot be considered genuine support. This is because they either need to be repaid or lack a clear climate focus.

Oxfam calculates genuine support by analyzing grants and interest concessions from climate finance loans. In contrast, the official OECD data includes the portion of loans given at market rates, which recipient countries are required to repay. Oxfam does not count this portion. It also estimates the proportion of climate finance that truly benefits climate efforts. According to Oxfam, their standards are “stricter, but not dramatically stricter” than those used by donor countries in their reporting.

In 2021, genuine support amounted to 25 billion dollars, while official OECD figures reported 89 billion dollars in climate finance.

Currently, there is no unified standard for reporting climate finance under the Paris Agreement. While the agreement encourages donor countries to voluntarily disclose the grant-equivalent portion of their climate finance, industrialized nations have strongly resisted mandatory reporting, according to Oxfam. Increased transparency and uniform reporting standards are crucial for the new Climate Finance Goal (NCQG), Oxfam emphasizes. nib

According to the EIB survey, Germans aged over 50 are more familiar with the causes, effects and potential solutions of climate change compared to younger demographics. Specifically, Germans aged 20 to 29 scored lower than those over 30. Moreover, compared to their peers in other EU countries, young Germans aged 20 to 29 performed less well.

Three-quarters of Germans attribute the main causes of climate change to “human activities such as deforestation, agriculture, industry and transportation”. The remainder attribute it to “extreme natural events such as volcanic eruptions and heatwaves” or to the ozone hole.

Regarding climate change mitigation measures, the EIB found differing perspectives. For instance, 43 percent of Germans surveyed believe that “lower speed limits on roads can mitigate climate change”, compared to a European average of 26 percent. Additionally, only a slim majority (53 percent, compared to 42 percent EU-wide) recognize that better-insulated buildings can help combat climate change.

In the EIB’s climate change knowledge test, which surveyed 30,000 people across 35 countries (EU, UK, USA, China, Japan, India and Canada), Germany ranks 10th among EU member states, slightly above the EU average. Finland, Luxembourg and Sweden performed the best. luk

The new Labour government in the UK plans to simplify the planning process for onshore wind turbines and eliminate two barriers that have severely restricted their expansion since 2015. The new Energy Minister, Ed Miliband, announced on Monday that:

The Labour government aims to double onshore wind capacity by 2030. Since 2017, the addition of new onshore wind turbines has declined sharply. nib

Currently, institutional investors have 4.3 billion dollars invested in bonds and stocks of companies involved in fossil energy projects. This amount comes from the financial research report “Investing in Climate Chaos“, conducted by the German NGO Urgewald and 13 partner organizations. The databases “Global Exit Coal List” and “Global Oil and Gas Exit List” list 7,500 institutional investors, including pension funds, insurers, asset managers, hedge funds, sovereign funds, foundation funds, and asset management subsidiaries of commercial banks.

Vanguard and Blackrock from the USA are significantly leading, each investing over 400 billion dollars in oil, gas, and coal businesses. Among the top ten largest investors listed by Urgewald, eight are based in the United States. Overall, more than 65 percent of investments in the compilation are from US companies.

“This demonstrates that US regulatory authorities have so far failed to effectively monitor and address the climate and transformation risks of major institutional investors,” said Alec Connon of the Stop the Money Pipeline campaign.

Germany ranks 10th globally. The largest German investor is Deutsche Bank with 25 billion dollars, ranked 30th on the global investor list, primarily due to its nearly 80 percent stake in DWS Asset Management. According to Urgewald, DWS continues to hold shares worth over 1 billion dollars in companies in this sector, despite its own coal policy.

A DWS spokesperson referred to the annual review of the coal policy when queried by Table.Briefings. DWS aims for a “complete cessation of coal use” in the EU and OECD countries by 2030, extending to all other countries by 2040.

German involvement in oil and gas is even greater, with Deutsche Bank and DWS together investing 23 billion dollars, closely followed by the Allianz Group and its subsidiaries Pimco and AGI. Urgewald criticizes investments, especially in ExxonMobil, which is expanding its fossil fuel operations and has sued activist shareholders proposing a change in direction.

The DWS spokesperson declined to comment on individual portfolio companies but stated that the company endeavors to “use our voting rights accordingly or express ourselves publicly at the respective annual general meetings in cases where we do not see progress through dialogue.” Ultimately, such companies could also be removed from “certain” product portfolios. av

In 2023, there were seven percent fewer cars on German highways compared to 2019, a trend observed in many major cities as well. Additionally, the traffic volume of long-distance trains increased by six percent. These findings are from an analysis conducted by the think tank Agora Verkehrswende, based on a report by the consulting firm KCW.

While the number of registered vehicles has significantly increased from 2019 to 2023, the study attributes the decrease in car traffic to several factors, including a decline in commuting between home and work post-pandemic. More people are now working at least partially from home. Furthermore, initiatives such as the introduction of the Germany Ticket and the rise in CO2 prices on fossil fuels have played roles.

Despite a slight increase in population and a steadily growing number of registered cars, car traffic has decreased compared to 2019, noted Wiebke Zimmer, Deputy Director of Agora Verkehrswende. “Traffic growth is not inevitable.” Public transportation, particularly rail travel, has seen an increase. While bus travel has seen fewer kilometers traveled compared to pre-pandemic levels, rail and train journeys have increased. Although there are currently fewer passengers than before the pandemic, they are traveling longer distances.

Agora Verkehrswende advocates for political support to sustain these positive trends. Measures could include:

With a “Power Plant Security Act” (KWSG), the Ministry for Economic Affairs aims to implement the construction of new climate-friendly power plants in several phases to ensure supply security. Overall, the government, with EU approval, can subsidize the construction of 12.5 GW of power plant capacity. This was announced by Economy Minister Robert Habeck following the government’s agreement on the federal budget for 2025. The new law is intended to prepare a capacity market for power plants that will regulate short-term power plant capacity offerings in the future.

The law is based on two pillars:

According to DUH’s survey, 186 out of 252 surveyed politicians use official vehicles emitting “significantly above the European fleet average of 95 g CO2/km”. Justice Minister Marco Buschmann (FDP), Education Minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger (FDP) and Transport Minister Volker Wissing (FDP) top the list with the most climate-damaging official vehicles, emitting between 184 and 205 g CO2/km. NRW Minister President Hendrik Wüst (CDU) and Berlin’s Regierender Bürgermeister Kai Wegner (CDU) fare even worse, emitting between 375 and 380 g CO2/km, according to DUH.

The most climate-friendly vehicles are driven by Development Minister Svenja Schulze (SPD) and Family Minister Lisa Paus (Grüne), whose vehicles emit less than 100 g CO2/km. DUH also notes positively that “the share of battery-electric official vehicles has increased to 34 percent“. Four out of nine federal ministers included in the survey drive fully electric vehicles: Schulze, Paus, Umweltministerin Steffi Lemke (Grüne) and Landwirtschaftsminister Cem Özdemir (Grüne). However, according to DUH, these EVs are often “grossly oversized” and consume a lot of electricity.

Criticism has been directed at the survey methodology. DUH assumes, for example, that plug-in hybrids are operated solely in combustion mode. Studies suggest this is often the case, but whether top politicians and their fleet managers actually follow this practice remains unclear. Additionally, some politicians have multiple official vehicles, but DUH only lists the vehicle with the highest emissions. The analysis also excludes many heavily armored official vehicles from evaluation. nib/dpa

The German government currently has no financing concepts for the multi-billion euro decarbonization of two-thirds of the German steel industry. This is according to the government’s response to a small inquiry from the Left party, as seen by Table.Briefings. So far, major steel companies have been provided with nearly seven billion euros in subsidies for the conversion. This is intended to replace one-third of the blast furnaces with electricity and hydrogen-based production facilities.

The remaining fossil-based steel capacities are to be decarbonized by 2045. The industry estimates an additional investment requirement of 20 billion euros for this. “Other ways of financing” need to be found for this, writes the government, “for example, by identifying additional (private) financing instruments“.

“The government does not know how to close the existing financing gap,” commented Left party MP Jörg Cézanne. He fears that without state funding, production capacities will be reduced. Therefore, “a clear political commitment to steel production in Germany, which must also be financially supported,” is needed.

State involvement in the steel transformation does not result from the subsidies. For instance, Thyssenkrupp’s steel subsidiary is planning to reduce capacities and jobs despite significant state funding. For new funding programs like “climate action contracts”, applicants must now make commitments or agreements with employee representatives to secure jobs.

“The concept of further funding with climate action contracts is right and important,” said Tilman von Berlepsch, climate-neutral industry advisor at the NGO Germanwatch. However, “continuity and reliability” in funding are needed “so that companies can invest and the survival of key industries with good unionized jobs can be ensured”. av

Following the 2019 European Parliament elections, Brussels was focused on climate action. Sustainability and transformation were the dominant themes. Von der Leyen’s response: The Green Deal. Five years later, everything seems different. Concerns about security, migration and deindustrialization are at the forefront. From a corporate perspective, however, the answer remains the same: The Green Deal must be continued and complemented by a green industrial deal. Otherwise, Europe’s industry risks falling behind.

According to MIT, $265 billion flowed into green technologies in the USA in 2023. This marked a 40 percent increase from the previous year when Joe Biden passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). $40 billion in state funds triggered $220 billion in private investments. Employment numbers rose, growth rates climbed and key technology development received a significant boost. This is expected to significantly enhance the country’s independence, resilience and security in the future.

Security, growth, climate action – a triad that Ursula von der Leyen also desires for her re-election to the EU Parliament on July 18. She must accommodate her alliance of the EPP, Social Democrats and Liberals and strengthen it with additional votes from the Greens or the ECR. The EU Council’s agreed agenda clearly focuses on security and competitiveness, points that could be well combined with a green industrial deal.

From the perspective of the Foundation for Climate Economy, a green industrial deal must focus on achieving climate targets. The planned interim climate target for 2040 plays a crucial role in guiding the path towards climate neutrality. Top priority must be given to the expansion of renewables, electrolyzers and networks. Alongside an integrated electricity market and a pragmatic approach to hydrogen ramp-up (better blue than nothing), this could alleviate high energy prices in the EU. It would also be beneficial for companies to have relief from reporting and due diligence obligations that tie up many resources.

However, none of this is possible without money. According to estimates by the Commission, achieving climate neutrality requires an investment surplus of more than $620 billion per year. Private capital could cover much of this, making the swift finalization of the European Capital Markets Union urgently necessary. The same applies to introducing a transformation category within the sustainable finance framework. Currently, investment goals are only labeled green if they are already low in CO2 emissions. To mobilize more capital for transformation, there also needs to be a label for companies with CO2 emissions and ambitious reduction strategies. Otherwise, industry will miss out on green capital providers.

On the other hand, when it comes to infrastructure spending, the transformation will also require government grants. For example, in the form of European climate action contracts that can cover start-up funding and operating costs to make green technologies directly competitive. If green leading markets are added, establishing an anticipated demand for clean technologies from the EU, a similar dynamic to that in the USA could unfold in Europe as well. Those looking to make their location fit for the challenges of the 21st century must invest heavily in industrial transformation rather than taking small steps. The IRA has set the example.

Sabine Nallinger is the CEO of the Foundation for Climate Economy, an independent CEO initiative promoting corporate climate action in Germany.

Özden Terli – Editor and presenter, ZDF weather department

Özden Terli is one of Germany’s most prominent weather forecasters. As an editor and presenter at the ZDF Weather Department, Terli is well-known to a broad audience. For many years, he has interpreted weather reports not just as information about sunshine and rain, but as science communication. The meteorology graduate educates his audience about the connections and consequences of the climate crisis in his show. He often faces backlash from the right-wing spectrum, attempting to silence him. According to Terli, many people, especially industry representatives, are more advanced than parts of the politics, which he claims are less focused on solving the climate crisis and more on distracting with non-issues.

Simon Evans – Deputy Editor, Carbon Brief

As the deputy editor of the specialized newsletter Carbon Brief, Simon Evans is among the world’s most important climate journalists. His areas of focus include British climate policy, international climate diplomacy, and myths surrounding electric vehicles. In 2022, Evans won the Press Gazette’s British Journalism Awards in the “Energy and Environment” category. He studied chemistry at the University of Oxford and later earned a doctorate in biochemistry from the University of Bristol.

Greta Thunberg – Swedish climate activist

She remains the global icon of the climate movement, although now controversial. As the founder of Fridays for Future, Greta Thunberg directed global attention to combating climate change in 2019, inspiring an entire generation of youth and prompting politics and business to engage constructively and proactively in effective climate action. She now primarily uses her prominence to draw attention to the war and suffering in Gaza. Thunberg has faced criticism for her anti-Israeli positions, which some argue stoke antisemitic sentiments.

Sven Egenter – Journalist and Editor-in-Chief, Clean Energy Wire

Sven Egenter is a journalist and managing director of the 2050 Media Projekt gGmbH, overseeing media projects like Clean Energy Wire (CLEW) and Climate Facts, focusing on energy and climate issues and connecting journalists in this field. Egenter spent twelve years with the Reuters news agency in Germany, the UK and Switzerland.

Vanessa Nakate – Ugandan climate activist

Ugandan activist Vanessa Nakate is a role model for the climate movement in Africa. She consistently highlights the injustices of Western policies, particularly regarding climate change. Nakate founded “Youth for Future Africa” and the African “Rise Up Movement”, advocating for rainforest protection in the Congo Basin. As a committed Christian, she criticizes neocolonial tendencies and calls for support for poorer nations in climate change mitigation, adaptation and compensation for damages and losses.

Ed King – Communications Director, Global Strategic Communication Council (GSCC)

Ed King is one of the most influential communicators in the international climate scene. At the GSCC think tank, he oversees strategic communication, synthesizing information from politics, media, UN bodies, business, science and NGOs in London. He crafts monthly or (during COPs) daily briefings providing critical insights for observers, negotiators and journalists to accelerate political decisions for climate action. King began his career as a reporter at the BBC and was among the founders of the climate website “Climate Home News“. He often enhances his analyses with parallels from the world of sports.

Ingmar Rentzhog – Founder and Chairman, “We dont have time”

Ingmar Rentzhog founded and leads the Swedish online platform “We don’t have time”, touted as the world’s largest media platform for climate action, spreading and discussing climate solutions and new ideas globally. Rentzhog studied mathematics and management and worked in financial consulting. He was a member of the Climate Reality Project, an advocacy organization founded by former US Vice President Al Gore. Since 2016, Rentzhog and his team from Stockholm have provided a platform for global climate discussions and enabled businesses to engage in economic and social innovations. The webcasts of “We don’t have time,” particularly during SB60 in Bonn, garnered 8.7 million views.

Carlos Nobre – Scientist

Brazilian scientist Carlos Nobre is a pioneer in research on the link between deforestation and climate warming, particularly focusing on the Amazon rainforest. He earned his doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and worked for over 35 years at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). Nobre was a lead author of various IPCC reports, including the 2007 report that received the Nobel Peace Prize. In an interview with Table.Media, he discussed the EU’s responsibility for deforestation in the rainforest.

Jenny Chase – Solar Analyst, Bloomberg NEF

Since 2005, Jenny Chase has worked as a solar analyst at Bloomberg NEF, a think tank providing data and analyses on the energy transition. Chase is one of the most respected observers of the solar sector, developing key economic and financial concepts on trade issues, price mechanisms and the integration of solar panels and batteries. She updated her book “Solar Power Finance Without the Jargon” in early 2024. Chase studied physics and natural sciences at the University of Cambridge.

Luisa Neubauer – Climate activist

Luisa Neubauer, 28, is the most prominent face of the climate movement in Germany. She gained fame through the Fridays for Future climate strikes in 2019. Neubauer has been a member of the Greens since 2017, though she claims to be inactive. Recently, she has faced challenges as the international climate justice movement clashed with Fridays for Future in Germany over their stance on the Gaza conflict. FFF in Germany is also fighting not to lose relevance. Personally, Neubauer endures a lot: She frequently experiences hate and sexist attacks.