The term “climate terrorists” has been chosen as Germany’s “non-word” for 2022. This term does not refer to those who upset the physical and ecological balance of planet Earth. Rather, it refers to people who use civil disobedience to defend themselves against the destruction of our livelihoods.

The current conflict over this is escalating in Germany’s Rhenish lignite mining region. The occupation and eviction of the village of Lützerath will shape the debate in Germany in the coming days and weeks. We hope that the disputes will remain peaceful, even though many people on both sides of the conflict feel powerless. We look at the issue in this week’s Climate.Table – and will delve deeper into the international significance of the German coal debate in the time ahead.

In the Swiss mountains, on the other hand, people who are far from powerless will be meeting starting next week. For a few years now, the leaders of politics and business have been talking about the climate at the World Economic Forum in Davos. But does that change anything? Three years ago, it seemed like it would: BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, called for serious climate action in its investments. Climate.Table describes what became of it. We also introduce the club of billionaires who have made climate action a personal and professional hobby. And we give a voice to an economist who wants to use Davos for true climate action.

There are other important developments as well: We detail the international effort to rebuild Pakistan, which aims to make the climate change-ravaged country more resilient than before – and could be a blueprint for the hotly debated loss and damage policy. And we tell a bizarre story from Switzerland: The new environment minister, Albert Rösti, now must advance a climate law that he opposed as an MP and against which he and his party, the SVP, have organized a referendum for the summer of 2023. This has now come back to haunt him as a member of the government.

Things remain exciting. And we will stay tuned. Enjoy reading, we look forward to your feedback.

Fink’s 2020 letter to CEOs was a big surprise. The BlackRock chairman warned that climate risks are increasingly becoming investment risks. In plain: Investments in fossil industries are becoming less attractive as they risk losing value in the future. Soon, therefore, there will be a “significant reallocation of capital.” Sustainable investing is the “strongest foundation for client portfolios going forward.” But a stocktaking after three years reveals meager results: BlackRock continues to invest in fossil-fuel industries, approves few climate motions at shareholder meetings, and the dominant business model of passive funds hampers important leverage.

Blackrock wanted to make sustainability the “new standard for investing.” The asset manager:

Blackrock claims to manage “around USD 490 billion in ESG funds“. In 2020, the figure was still a good 200 billion; in 2021, it reached a peak of 509 billion. Just over 6 percent of Blackrock’s managed assets are thus invested in ESG funds. About 25 percent of assets are invested in companies or government-issued assets that have targets to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions (“science-based targets” or equivalent). By 2030, this share is expected to grow to 75 percent as more companies set such targets.

But the climate benefits of many supposedly green funds are limited, says Jan Fichtner, who researches sustainable finance and index funds at the University of Amsterdam. “Many Blackrock funds are now ESG integration funds. But our research shows they’re little different from traditional index funds. They exclude coal companies, but oil and gas companies continue to appear in the funds.”

BlackRock’s divestment from coal is also insufficient. The company can still invest in 80 percent of all companies that operate coal mines or power plants. BlackRock’s exclusion criteria leave too much leeway. BlackRock has not set any specific targets at all for the oil and gas industry. When the Texas pension fund tried to withdraw its investments, BlackRock confessed that the firm was probably the largest investor in fossil fuels. It wanted “to see these companies succeed and prosper.”

BlackRock stresses that many emerging economies continue to rely on fossil fuels. Governments and companies would have to ensure that people continue to have access to reliable and cheap energy. The energy transition will take decades, according to BlackRock. Some developments show it could go faster. Western nations have agreed with initial partner countries on Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETP), which would also involve private backers. Investments in fossil industries and raw materials are also not compatible with the 1.5-degree target.

BlackRock’s coal exclusion does not apply to the company’s passive funds. These account for an immense share of managed assets. In contrast to actively managed funds, the assets are only invested passively, for example in all shares of a stock index. BlackRock’s iShares division now manages over two trillion US dollars in assets in such funds. In addition, trillions more are held in index funds for institutional investors.

The funds are long-term investments. Passive funds can only sell their stake in fossil companies if they leave the stock index that the fund copies. Thus, BlackRock cannot force respective companies to become more sustainable by threatening to sell the shares.

The asset firm wants to overcome this passivity by exercising its voting rights more actively at annual general meetings. Activists welcomed this as a “180-degree turn“. Whereas in 2020 the company approved just 12 percent of all ESG proposals (proposals with an environmental and social focus) at annual general meetings, the figure was as high as 40 percent in 2021. Between June 2021 and 2022, however, the approval rate dropped to 22 percent. The company still lags behind many of its competitors when it comes to approving climate-related motions, as an analysis by ShareAction shows.

Recently, BlackRock argued, more proposals have been too restrictive and interfered too much with the management of the respective companies. The company opposes proposals that called for a phase-out of fossil fuels. And although BlackRock is demanding more transparency from companies regarding climate risks and plans, the asset firm is lobbying against US rules on Scope3 emissions disclosure.

Critics are also critical of BlackRock’s promise to launch more ESG funds. What sounds like a contradiction is rooted in the design of many funds. Sustainable ETFs, for example, would only buy stocks that are already being traded on the stock market, says Tariq Fancy, a former top executive who was in charge of ESG at BlackRock. “Investing in such a fund does not provide additional capital to more sustainable companies or causes,” Fancy says. Fichtner adds, “Many ESG funds cannot invest in capital raises at all. Especially with passive funds, that’s not possible, since they only replicate an index.”

BlackRock itself repeatedly insists that it only manages clients’ money and that it has a statutory “fiduciary duty” to invest the money in the interests of its clients, that is, profitably. Excluding the fossil industries would run counter to this. Between the lines, this means: If customers do not want green investments, our hands are tied.

But are BlackRock’s hands somewhat tied due to competition? If BlackRock were the first asset manager to completely exit fossil fuels, many clients could simply migrate to other providers. For these reasons, it is illusory for BlackRock and other asset managers to bring about a green transformation on their own, says Fancy. Instead, calls for government regulations such as carbon pricing to make fossil fuel industries more expensive. Then investments would no longer be worthwhile and financial flows would be directed much faster to green industries, says former BlackRock sustainability chief Tariq Fancy.

As UN Special Envoy on Climate Ambition and Solutions, the US billionaire is one of the most important links between politics, business and civil society in the United States. Bloomberg made his fortune (currently estimated at about 80 billion dollars) as an investor and owner of his financial information service Bloomberg and a TV station. He was mayor of New York City between 2002 and 2013, after which he became active in climate action. At the UN level, he pushes climate action in business and finance. Bloomberg has used at least 1.5 billion dollars of his private capital to date to fund political campaigns and environmental groups – including the “America’s Pledge” campaign by US business and civil society when US President Donald Trump withdrew the country from the Paris Agreement in 2017. His foundation funds activism for renewables and against fossil fuels, among other causes.

The founder of Amazon and currently the richest man in the world with a wealth of around 170 billion, Jeff Bezos, is funding climate and sustainability goals by 2030 to the tune of ten billion dollars through his “Earth Fund“. And it could become even more if he donates his fortune to charity, as previously announced. Bezos also owns the leading US daily newspaper “Washington Post,” which recently massively expanded its climate coverage. And, together with other corporations and the US government, he is pushing the controversial US Energy Transition Accelerator initiative, which aims to help companies offset their carbon emissions through deals with developing countries.

Marc Benioff is one of his many partners in this effort. The founder of the tech company Salesforce and a mere single-digit billionaire (eight billion dollars) has not only bought the renowned TIME magazine and founded his own ocean research and conservation institute in his home state of California. He has also announced that he will donate 300 million dollars for ecosystem restoration and climate justice.

Bill Gates is also seeking his own path between political lobbying and high-tech enthusiasm for climate action. With his company Breakthrough Energy, the Microsoft founder (129 billion) is heavily investing in technologies that are supposed to solve the climate crisis: Lab meat, fusion and nuclear energy, carbon removal and storage. According to media reports, Gates made sure that US President Biden’s long-controversial Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) investment package was passed in 2022 against much opposition. Many of the technologies supported by Gates are given tax incentives under the IRA. Gates announced plans to reinvest profits from his companies in climate action.

The IRA was also helped into existence by Australian multi-billionaire Andrew Forrest (fortune 18 billion dollars, according to Forbes) – among other things, through a meeting with Democratic US Senator Joe Manchin, who had blocked the bill for a long time. Forrest made his money from lucrative mining in Australia with the Fortescue Metal Group. He blamed the devastating fires in Australia less on climate change and more on poor forest management. He does not deny climate change, but calls for adaptation and restructuring above all. And he sees great economic potential in the production of green hydrogen – which, in turn, Biden’s IRA program would subsidize so heavily in the United States that it could be available cheaper and faster than anywhere else in the world. Forrest struck a deal with Germany’s E.on Group in 2022 for the rapid delivery of large quantities of green hydrogen from Australia – with up to 50 billion dollars expected by 2030.

US billionaire Tom Steyer (1.5 billion dollars) also handles big numbers: The hedge fund manager plans to raise 40 billion dollars with a climate fund for investments in green future technologies. The Democrat ran for the US presidency in 2020 with far-reaching ideas on climate action and social justice. He paid for the more than $340 million campaign from his own funds. He is considered one of the most important financiers of the US Democratic Party and regularly gives large sums of money to environmental and climate groups as well.

Investor John Doerr (12 billion dollars) has also invested in California: He gave more than a billion dollars to the elite Stanford University, which has used the money to establish a “Sustainability School” in his name. This donation, which is gargantuan even by US standards (only Michael Bloomberg has given more to a university), is to be used to research ways to overcome the climate crisis – although critics complain that it is also financed by money from the fossil fuel industry.

In Australia, billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes (12 billion dollars) is fighting the fossil fuel industry with a rich man’s trick: Buy out coal company AGL and quickly shut down the coal business in Australia – while making a buck in the process. Cannon-Brookes, who earned his money with the software Atlassiantlassian, is considered an unconventional thinker who is also planning a 120-square-kilometer solar farm in Australia.

US heiress Aileen Getty is channeling a share of the billions from the oil business that made her family rich into climate action. She supports the Climate Emergency Fund, which finances, among others, the Just Stop Oil campaign and the “Last Generation”. Getty defends the actions of symbolically attacking paintings. Her family sold its shares in the oil business 40 years ago “and I instead vowed to use my resources to take every means to protect life on Earth,” Getty writes.

The Japanese billionaire Masayoshi Son (21 billion dollars) has had many successes and several failures to his name. He ultimately became rich with the software company SoftBank and, after the nuclear disaster in Fukushima in 2011, founded the Renewable Energy Institute in Japan, of which he acts as Chair in addition to his function as a member of the SoftBank board of directors. The institute’s mission: To build a “society based on renewable energy,” to develop technology and business models for this goal, and to network business, research and civil society nationally and internationally.

India’s richest person, Mukesh Ambani, is also now betting on climate-friendly technologies with his billion-dollar fortune. Ambani, the tenth-richest person in the world with a fortune of 90 billion dollars according to the Forbes list, announced in 2022 that his company would invest 76 billion dollars in the Indian solar revolution. Ambani’s company, Reliance Industries, made it big as an oil and energy company. He owns a house with its own hospital and private car showroom and financed his daughter’s wedding with 100 million dollars.

Sir Richard Branson, with a fortune of 2.3 billion dollars, is also part of the climate billionaires. The founder of the “Virgin” chain, which included a record label, megastores, an airline, hotels, telecoms companies and a cruise operator, calls innovations and new technologies the key to solving the climate crisis, just like Bill Gates, for example. Branson announced in 2006 that he would spend a total of three billion dollars on climate action over the next decade, but it is unclear whether it was more than 400 million. The eccentric technophile (like Jeff Bezos) has his own company for space flights, which generate high levels of carbon emissions.

The commitment of business elites to climate change does not meet with universal approval. The accusation is that they often accumulate their wealth by doing business that is harmful to the climate, and that they are more concerned with the show effect or the implementation of their own economic goals. Unlike elected politicians, they act in their own interests and on their own behalf and cannot be held accountable for their actions; if they fail, they cannot be removed from office.

And for some, it is the super-rich who set a bad example. When it comes to their lifestyles with extremely high energy and material consumption, their personal emissions are “several thousand times” higher than the average of ordinary people on earth, criticizes the aid organization Oxfam in an expert report. And their companies’ investments, such as those of energy and cement companies, have an even greater carbon footprint. According to Oxfam, the 125 billionaires at the top of the Forbes list are responsible for carbon dioxide emissions of 393 million tons – one million times more than the average person, who emits around three tons a year.

In December, Rösti was elected by parliament to head the Swiss Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications DETEC. Given his previous role, however, it is unlikely that he will step up climate protection in Switzerland as environment minister. He now has to represent a law that his own party wants to bring down and against which, as a parliamentarian, he initiated a referendum.

Rösti is no stranger to this issue: As president of the association of fuel importers (Avenergy, formerly Swissoil), he has already played a key role in ensuring that the Swiss population rejected a carbon law at the ballot in 2021. The law envisaged:

The law was narrowly rejected with 51.6 percent of votes. And came as a surprise, as all parties except the SVP were in favor of it. A strong mobilization of the population in rural areas contributed to this.

A period of confusion then followed. Subsequently, the state government presented a less ambitious proposal for a new carbon law at the end of last year. It:

However, the goal of the new law remains the same as that of the failed bill: To halve carbon emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels.

In parallel, a non-partisan committee provided more impetus to Swiss climate policy with their “Initiative for a Healthy Climate”, known as the “Glacier Initiative”. The initiative calls for an almost complete ban on imports of fossil fuels from 2050.

Parliament has drafted a counter-proposal. It provides for:

After this draft law, the “Glacier Initiative” withdrew under conditions. The reason: A law would be implemented much faster than via a referendum.

But now the SVP, the party of the new climate and energy minister Albert Rösti, has collected enough signatures for a referendum against this law – and the SVP’s referendum committee included none other than Albert Rösti himself. So the Swiss will vote again in mid-2023 on the way forward in climate policy.

The Swiss government is based on the principle of collegiality: All seven members of the Federal Council represent the opinion of the entire government, to the public, and defend it in the voting campaigns. Albert Rösti will therefore have to defend a climate protection law right at the beginning of his term in office, which his party wants to prevent and which he actively opposed himself while he was still a member of parliament.

However, his options are limited: He will not be able to turn Switzerland’s climate policy upside down, as his proposals will have to find a majority in the Federal Council. And when asked whether he wanted to play party politics or follow the principle of collegiality, he said chose the principle of collegiality after his election. Climate protection, he said, “plays an important role.” Decarbonization was necessary, but “enough electricity must be produced.”

The leader of the Green Party, Aline Trede said: “I am not afraid of Mr. Rösti in the Uvek. But we will keep a close eye on what he does, and especially, what he doesn’t do.” And Marcel Hanggi of the Glacier Initiative Committee said, “We expect Federal Councillor Rösti to represent the climate protection bill regardless of his party opinion. After all, Switzerland has committed to the 1.5-degree target with the Paris Agreement.”

Rösti can slow down progress by making less ambitious motions. But he cannot slow things down too much either: Under the Paris climate protection agreement, Switzerland has committed to cutting carbon emissions in half by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. And the country is already behind schedule, having failed to meet its previous target of minus 20 percent by 2020. And even with the measures in the planned new carbon law and even the government’s counter-proposal, which the SVP referendum is now seeking to overturn, Switzerland will likely miss its Paris goals. Priscilla Imboden from Zurich

The international funding commitments far exceeded Pakistan’s expectations of roughly 8.15 billion dollars: While the government had expected about 8.15 billion dollars in aid for reconstruction, the January 9 Geneva conference resulted in funding pledges of more than 9 billion dollars. The money, from nearly 40 donor countries, multilateral banks, and agencies, will be used to help with recovering from last summer’s extreme monsoons and floods.

The sheer scale of damage and humanitarian crisis affecting 33 million people of whom nearly half are children has rallied the global community around Pakistan. Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif was clear that his country is not capable of handling reconstruction on its own. Speaking at the high-level inaugural session of the conference, he said, “For recovery and reconstruction, the minimum requirement is 16.3 billion dollars. Half of it is proposed to be met from domestic resources and the other half from development partners and friends.”

The conference is the first run of a model for providing climate finance to address loss and damage. The onus of providing funds is still on the “donor-developed” countries, but there is a plan to match the use of the funds.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres said, “We also need to right a fundamental wrong. Pakistan is doubly victimized by climate chaos and a morally bankrupt global financial system. We need creative ways for developing countries to access debt relief and concessional financing when they need it most. Above all, we need to be honest about the brutal injustice of loss and damage suffered by developing countries because of climate change.” Much more than 16 billion would be needed in the longer term.

Housing, agriculture and livestock, transport and communication were the sectors most impacted by the floods. In terms of regions, the province of Sindh was the worst affected, followed by Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Punjab.

A Disaster Needs Assessment by UNDP and the World Bank (PDNA) estimated total damages to exceed 14.9 billion dollars, and total economic losses of about 15.2 billion dollars. Funding required for a resilient rehabilitation and reconstruction is estimated to be at least 16.3 billion dollars. This estimate does not include investments required to support Pakistan’s adaptation to climate change and overall resilience to future climate shocks.

At the conference in Geneva, Pakistan presented its plan for reconstruction: The Resilient Recovery, Rehabilitation and Reconstruction (4RF) Framework provides:

The plan proposes interventions prioritized

They include reforms in political structures, investments/programs for recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction, and institutional effectiveness. So far, however, many details remain unclear.

Besides the financial commitment, the conference agreed to a structured process of support for Pakistan’s resilient recovery. Key elements of the plan include project preparation, developing a financing plan, enhancing capacity and long-term resilience.

These interventions will span four strategic recovery objectives:

Projects include plans to designate areas protected against flooding, new building codes, flood-proof police stations and prisons, and better collection of meteorological data and early warning systems.

The plans thus meet the demand of UN Secretary-General António Guterres. Guterres stressed at the conference that reconstruction efforts must go beyond repairing the damage caused by the floods. Efforts must include “initiatives to address daunting social, environmental and economic challenges. Reconstructing homes and buildings. Re-designing public infrastructure – including roads, bridges, schools and hospitals. Jump-starting jobs and agriculture.”

Nearly half of the 9 billion dollars pledged came from the Islamic Development Bank (4.2 billion dollars), another 2 billion dollars were committed by the World Bank and Saudi Arabia pledged 1 billion dollars, the European Union and China were among the other major donors.

Taking to social media, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Sharif said “the world witnessed yesterday how the nations can come together in a show of solidarity to create a model of win-win partnership to lift suffering humanity out of tragedy”.

As Pakistan transitions into long-term reconstruction, priorities should include financing the most immediate and time-critical components of the 4RF including urgent social expenditures aimed at preventing health crises, mitigating the impact of winter as well as the rains in the next monsoon season and restoring livelihoods. The process must focus on building resilience and increasing Pakistan’s capacity to withstand future shocks.

Part of the program also includes a detailed financing plan, which also provides for fostering public-private partnerships. A facility will be established, or the UNDP-supported Project Preparation Facility already established within Pakistan’s Ministry of Finance will be reinforced, with a dedicated fund to finance the professional development by qualified consultants of viable projects selected from the 4RF framework, for official, private and public-private financing and/or investment. An “International Partners’ Support Group to Pakistan’s Resilient Recovery, Rehabilitation and Reconstruction” will be established under the leadership of the Pakistani government. The Group will assist Pakistan develop concrete plans and projects and help secure financial and other commitments of support for the implementation of these plans and projects over the coming years.

Jan. 12; 2 p.m. – online

Webinar Engaging citizens as decision makers in clean energy transitions

The International Energy Agency’s webinar will explore key issues in social dialogue and citizen engagement as part of decision making processes. Info

Jan. 16-20; Davos

Summit World Economic Forum

The Annual Meeting will convene leaders from government, business, and civil society to address the state of the world and discuss priorities for the year ahead. Info

In an open letter to the government of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, several climate scientists call for a halt to the eviction of Lützerath. As the researchers of Scientists for Future write in their letter addressed to Minister-President Hendrik Wüst, Minister for Economic Affairs Mona Neubaur and Minister of the Interior Herbert Reul, the village has “become a symbol”. They cite “substantial scientific doubts about the acute necessity of an evacuation.” A moratorium would offer “the opportunity for a transparent dialog process with all those affected” and would significantly increase the credibility of German climate policy.

In October 2022, the government of North Rhine-Westphalia, the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology and the German energy company RWE agreed to bring forward the phase-out of coal in North Rhine-Westphalia to 2030. In return, larger quantities of lignite may be mined in the short term. Part of the agreement is that the area of Lützerath may be mined.

On the question of whether the coal under Lützerath really still needs to be mined, various expert reports have come to different conclusions. The government of North Rhine-Westphalia relies on calculations according to which mining is necessary to guarantee Germany’s energy security. Scientists for Future points to several expert opinions that disagree with this.

Manfred Fischedick, Scientific Director of the Wuppertal Institute, calls the decision for or against Lützerath one “between plague and cholera”. If Lützerath were to be preserved, other towns would have to make way for the open pit mine. In addition to energy and climate policy aspects, Fischedick also cites water management and open pit planning factors as reasons:

“The state government has understandably chosen to preserve villages where people still live today,” Fischedick said.

To ensure that Germany achieves its climate targets, however, Lützerath is not the decisive factor, but the European Union’s emissions trading system, says Ottmar Edenhofer, Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “As long as the cap on greenhouse gas emissions remains really hard and falls, and the carbon price is effective, we can temporarily burn more coal – because this leads to emissions savings elsewhere,” Edenhofer says. Even if Lützerath is excavated: Coal has no future. ae

Scientists from the Global South are hardly represented in the author teams of the most important climate studies. This is the result of a survey by Carbon Brief. According to the survey, the 25 climate studies that receive the most media attention were predominantly written by men from the Global North:

The ten climate studies with the widest reach in traditional and social media show the breadth of the climate crisis. They deal with:

More than eight million new jobs will be created worldwide in the field of green technologies by 2030. This is according to a new Energy Technology Perspectives 2023 analysis by the IEA, which was published today. If countries meet their climate targets by 2030, the market for green products such as solar panels, wind turbines, EV batteries, heat pumps and electrolyzers for hydrogen will increase:

However, the IEA warns that the supply chains and production of these goods are concentrated in a few countries. China dominates manufacturing for all the technologies listed. The three largest producing countries account for at least 70 percent of production for all technologies listed. There is also a sizeable geographic concentration for feedstocks, such as lithium and cobalt.

“As we have seen with Europe’s reliance on Russian gas, when you depend too much on one company, one country or one trade route – you risk paying a heavy price if there is disruption,” IEA Chairman Fatih Birol said. Birol said he is therefore pleased that many countries are investing in building production capacity. However, competition must remain fair, he added. The IEA report also stresses the importance of global trade in green technology goods. nib

Instead of capturing carbon, regenerating rainforests on recently cleared land releases carbon for at least ten years. This is the result of a recent study published in the scientific journal PNAS.

For the study, researchers led by Maria Mills of the University of Leicester examined eleven areas in Malaysia that had previously been deforested to varying degrees. Their results contradict the widely accepted theory that young forests absorb and bind a comparatively large amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere due to their strong growth.

Deforested areas on which forests regrow are generally regarded as important carbon sinks. Tropical rainforests, in particular, are considered to have an important role in offsetting global emissions from fossil fuels. The PNAS study now shows: Once not just the carbon footprint of regenerating plants is considered but also the emissions from decaying deadwood and the respiration of the soil, the balance changes.

The study demonstrates how important it is to include all components of an ecosystem in the carbon balance. When it comes to the carbon footprint of forests, the longevity of the products derived from their wood also plays a role. If wood is used as a building material, for example, carbon remains bound in it for a long time. If it is burned, carbon is quickly released back into the atmosphere.

The very first priority for the climate must be to stop further deforestation of natural forests, Almut Arneth, ecosystem scientist at KIT Karlsruhe who was not involved in the study, commented on the study’s publication. “Climate change has required rapid, massive reductions in fossil emissions for years, but this still isn’t happening. The whole debate about the additional expected contribution of forests through reforestation tends to distract from this.” ae

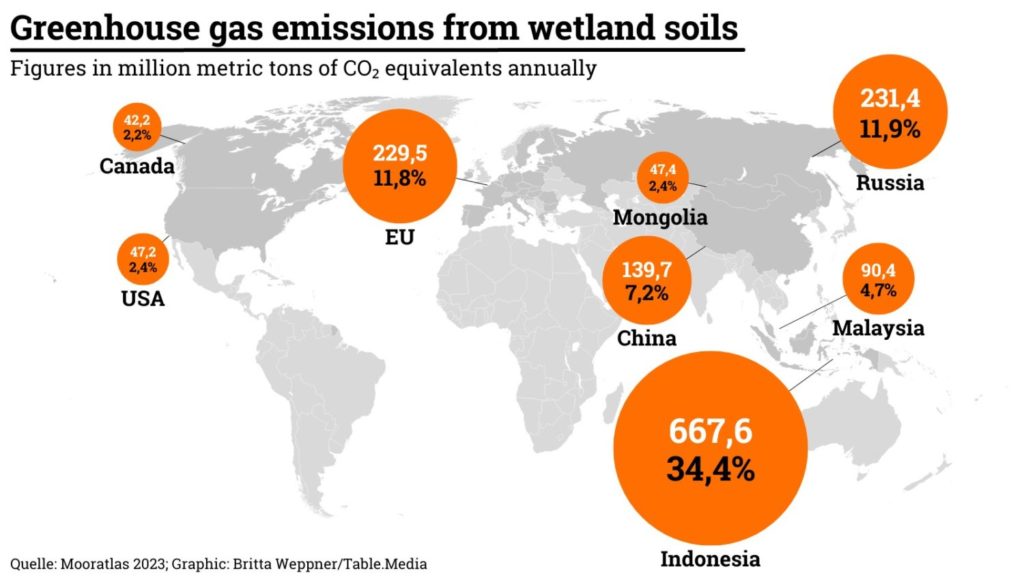

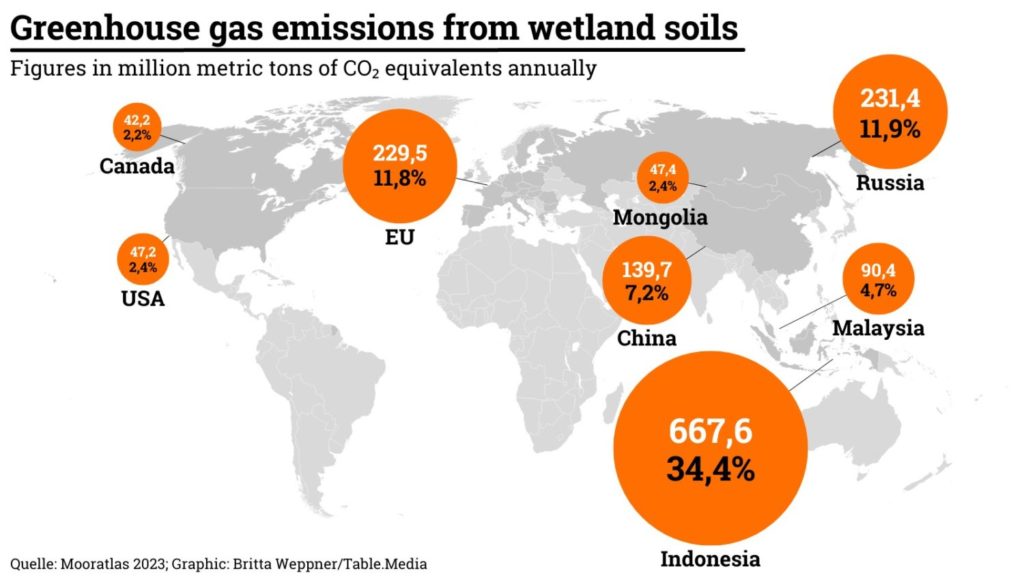

The good news first: Worldwide, 88 percent of all wetlands are still largely untouched. They thus store around 600 billion metric tons of carbon on just 3 percent of land area – twice as much as is bound in the biomass of all forests, which cover a total of 27 percent of land mass. However, their loss is rapid: Every year, 500,000 hectares of wetlands are being drained, creating an enormous global climate issue. This is according to the new “Mooratlas” presented this week by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND) and the Michael Succow Foundation.

The atlas presents extensive information and numerous charts and diagrams about the “wet climate protectors” and their role in global warming. For example, over 1.9 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalents are emitted from drained wetlands worldwide, 90 percent of which is carbon. Together with greenhouse gases from peat fires, this amounts to 2.5 to 3 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases annually – about as much as India’s carbon emissions.

Emissions vary by country: By far the largest source of gases from dried westlands is Indonesia, followed by Russia and the EU. Although drained wetlands make up less than half of one percent of the global land mass, they account for about 4 percent of man-made emissions.

In Germany, the situation of the wetlands is critical. Most of Germany’s original marshland has been drained for pasture or arable land. Today, only about four percent of Germany’s land mass, 1.8 million hectares, is still covered by wetlands. However, they generate about 53 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents annually, about 7 percent of Germany’s total greenhouse emissions.

Germany’s goal of net zero by 2045 can only be achieved with “very consistent peatland protection,” the atlas warns. This means that 50,000 hectares would have to be rewetted every year. That is equivalent to the area of Lake Constance. So far, however, only 2,000 hectares per year have been rewetted. bpo

“We are not, and will not be, a ‘climate policymaker.’” US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome H. Powell has clearly rejected the idea that central banks should use their available resources to actively drive the transformation toward a climate-friendly economy. This was reported by several media outlets. Powell was speaking at a conference of the Swedish central bank.

The Fed would have to focus on its original mission of keeping inflation low, overseeing the banking system and promoting a healthy labor market, Powell said. “It is essential that we stick to our statutory goals and authorities, and that we resist the temptation to broaden our scope to other important social issues of the day,” he said.

Leading central bankers around the world disagree on the role of central banks in the transformation. Some are calling for more commitment to climate policy. One of their leading representatives is Mark Carney, former head of the Bank of England (BoE).

In the US, according to the New York Times and Financial Times, Democrats are urging the Federal Reserve to engage more in climate policy, while Republicans fear the central bank could overreach its mandate. Powell now said that without an explicit statutory mandate, it would be “inappropriate” for the Fed to use its tools “to promote a greener economy or to achieve other climate-based goals.”

Reinsurer Munich Re expects losses from natural disasters to rise worldwide in the coming years. In 2022, floods, storms, forest fires and other natural disasters caused economic losses of 270 billion dollars, the company announced on Tuesday. That puts the year in line with the “loss-intensive” past five years. The most expensive disaster, at 100 billion dollars, was Hurricane Ian, which hit the US East Coast at the end of September 2022.

Insurance companies increasingly bear the costs of natural disasters: Of the 270 billion in total losses on the balance sheet, around 120 billion were insured. Two factors are important here: Natural cycles such as La Niña favor hurricanes in North America, floods in Australia, heat and drought in China, or heavier monsoons in South Asia. Climate change enhances these weather extremes, sometimes amplifying the effects.

Munich Re has been documenting losses from natural disasters for decades because they influence risk management. The reinsurer considers itself a pioneer in analyzing the effects of anthropogenic global warming and thus climate change. The past eight years have been the warmest ever, and the associated higher energy content in the atmosphere is changing risk assessments, it said. Although individual loss events could not be attributed to climate change alone, analyzing long-term trends of meteorological data in conjunction with insurance and socioeconomic data provides important clues to changing risks from severe weather hazards. dpa/tse

Once again, the rich and important are gathering in Davos, along with those who want to be around them. Once again, climate is high on the agenda at the World Economic Forum. And once again, it is easy to joke about it.

Billionaires on private jets; corporate CEOs with a fiduciary obligation to their shareholders praising social entrepreneurship: Of all people, the global elite – who by definition benefit the most from the status quo – are calling for radical change in Davos. Cynicism seems appropriate.

Davos alone cannot save the climate, but neither can it be done without Davos. Because this is where the powerful of big business influence global transformation – just as they do in other places. At COP27, for example, the more than 600 registered lobbyists from the oil and gas industry at the UN climate talks in Sharm el-Sheikh are, for me, one thing above all: A sign that there actually is a lot at stake. Does anyone really believe that all the Exxons and Saudi Aramcos of this world would not exert any influence on climate policy if there were no COP27?

Corporate leaders and their financiers have always been strongly represented in Davos, as have the most prominent exponents from civil society and politics. Climate has played a role for quite some time. Representatives of environmental groups and climate research were in Davos even before Greta Thunberg warned all celebrities present in 2019: “Our house is on fire!”

To what extent the participants of the forum agree with this assessment is a different question. It is now clear to (almost) everyone that climate action is not a question of “if” but of “when” and “how”. It is also clear that those who profit from climate pollution basically only need to delay. They, too, are in Davos just as they are, for example, at COP27. It is clearly part of their strategy to use these meetings as a prominent backdrop for their lip service.

The task for the rest of us is to counteract. There is a fine line between productive corporate commitment and pure greenwashing; There are plenty of delay tactics. But they all boil down to a similar argument: “No need for radical steps now. New technology will do the trick.”

It has long been clear that this is only partially true. Of course, we need new technologies in the fight against climate change. But just sitting back and waiting for them is not enough. For them to have an impact, they must of course be backed by political steps – including radical ones.

One example: Solar power is now the cheapest electricity source in history, as the International Energy Agency declared back in 2020. And yes, dear naysayers, that includes the fact that the sun never shines for 24 hours between the polar circles. And yet the world is still heavily reliant on fossil fuels – in part because more than 90 percent of global coal-fired power capacity is insulated from market competition by long-term contracts that often span twenty years or more.

Another example: Existing infrastructure can be used for comparatively eco-friendly liquid fuels, so-called e-fuels. This makes it more difficult to introduce electricity-based solutions, such as battery-powered electromobility or electricity-powered heating systems, even though these use energy five times more efficiently in purely physical terms.

So the so-called free market, in which the best technology will prevail on its own, is a myth. When every ton of coal and every barrel of oil costs more in external costs than they add in value to GDP, it is clear that market forces are pointing in the wrong direction. It is important to state this so directly. Even if it may not please those who rake in fat private profits from burning fossil fuels while society bears the costs.

This is where the high-level talks at Davos meet the harsh reality of interest politics. Because in the end, of course, Davos is all about politics, too – and thus about the question of how someone who wants to campaign for climate action in Davos can make the greatest possible impact. Ultimately, the goal must be to find starting points to initiate real change.

Davos is a particularly effective place to pull the levers to this end, because it is where people who have the money and the power to really make a difference come together. This already starts with their arrival. How about, for example, only granting landing permission to private jets that run exclusively on sustainable fuel?

At first, this may sound like greenwashing, perhaps even a bad joke. But sustainable fuels are just one example of the technological optimism that characterizes the Davos meetings and the new technologies we need to halt climate change.

Without sustainable fuels, it will be impossible to make global air travel carbon-neutral. These fuels are still very expensive: For a transatlantic flight in economy class, the surcharge is around 300 euros. Very few customers voluntarily pay that much. And yet sustainable fuels are the airlines’ great hope.

That’s why policymakers are needed to push the necessary investments in new technologies. Now. Only then will they become cheaper, as the example of solar power shows. And as was initially the case with solar power, the wealthy – precisely those who are meeting in Davos – are needed here, too, to be the first to apply technologies that are still relatively expensive.

Of course, night trains and high-speed trains would be preferable to taking the plane, but some distances cannot be covered by trains. In the end, as so often, it is about finding the right balance between behavioral changes and new technologies, individual steps and political changes, energy savings and investments in low-carbon energy sources. It is about the great transformation.

It is almost impossible to predict who will emerge as the winner from this transformation and then be in Davos in ten, twenty, or thirty years’ time. But it is clear that there will always be such a meeting somewhere. All the more important to use it for the climate. And with a bit of luck, the forum will contribute a little bit to making sure that Davos will still be cold and snowy at this time of year thirty years from now.

Gernot Wagner is a climate economist at Columbia Business School and the author of “Geoengineering: The Gamble” (Polity, 2021).

Earlier this week, Jochen Flasbarth put a lot of money on the table: Germany is providing 84 million euros to help crisis-stricken Pakistan cope with the consequences of climate change. In 2021, heavy rains, made more likely by global warming, had flooded ten percent of the country and deprived two million people of their homes. At the UN donor conference in Geneva, the State Secretary in the German Development Ministry BMZ said: “The example of Pakistan shows that we don’t just talk about climate damage and its financing in the abstract at climate conferences, but also take concrete action when things get serious.”

This is what keeps driving the 60-year-old in his professional life: Take concrete action and reduce risks with foresight. He is no longer responsible for climate protection, but the BMZ finances many climate projects. So Flasbarth remains an important player. “The crucial thing is that we support Pakistan, not only in its immediate reconstruction, but also in adapting better and sustainably to climate change. We want to work together so that the next time there’s a climate shock, the damage will be smaller or avoided altogether.”

Flasbarth represents the Development Ministry, but he remains a specialist in all climate issues. For a long time, he was in charge of international relations at the Environment Ministry. At the climate COPs and, in December, at the biodiversity COP in Montreal, Jochen “Flashbart,” as many on the international stage call him, is a highly esteemed interlocutor. He not only negotiates on Germany’s behalf, but has been and continues to be called upon by COP presidents to act as a firefighter on particularly sensitive issues: Sometimes calming Turkey here, sometimes preparing a report on the hot issue of climate finances there. Many in the international climate circus consider Flasbarth to be Germany’s real environment minister.

Climate action runs like a thread through his biography. At the age of 11, Jochen Flasbarth searched in the garden for the great auk, an extinct seabird from the penguin family. Some 40 years later, he negotiated the key agreement in Paris in which the United Nations agreed on climate action. And in the meantime, he has reached many big issues of environmental policy. At COP15, he is once again involved in international species conservation – because the crises in climate and biodiversity are closely intertwined with development policy.

Initially, the economist Flasbarth remained in civil society, then as a high-ranking civil servant in the Federal Environment Ministry. Then he moved to the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) with Minister Svenja Schulze.

Flasbarth grew up in the industrial town of Duisburg-Rheinhausen. As a teenager, he protested against a landfill, then joined the Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union NABU. “At that time, it was still called the German Association for the Protection of Birds – and it was exactly what it was called,” says Flasbarth. In the 1980s, the association became politicized and Flasbarth made a name for himself, becoming NABU president at the age of 29.

But Flasbarth does not want to stay in this post forever. In 2003, he was appointed department head of the Federal Ministry for the Environment. “Many people were surprised at the time,” says Flasbarth, “but this level is totally underestimated from the outside.” Flasbarth also rose through the ranks at the ministry, heading the Federal Environment Agency and eventually becoming state secretary in 2013. Climate policy remains his topic at the BMZ, and it is from here that the majority of foreign German climate funding flows.

Flasbarth is not someone who stays quietly in the background. Even as state secretary, he sees himself as a public figure. In a three-hour interview, he lets journalist Thilo Jung pester him, and on Twitter he sometimes defends his colleague Jennifer Morgan at the Foreign Office whenever a critical article is published in German magazine Der Spiegel. “I was always lucky that the ministers were okay with it,” says Flasbarth.

He also defends the German government from criticism by climate activists – partly because he knows differently from international negotiations: “Germany has always had a better reputation worldwide than at home.” Flasbarth has experienced that first-hand. International negotiations are often tricky because of the unanimity principle. “Nothing works as soon as someone says no,” says Flasbarth. The fact that a breakthrough was actually achieved in Paris was due, among other things, to then-French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius and his preparation, he says. In the meantime, he himself belongs to the small circles where decisions are made at the last minute. Jana Hemmersmeier/bpo

The term “climate terrorists” has been chosen as Germany’s “non-word” for 2022. This term does not refer to those who upset the physical and ecological balance of planet Earth. Rather, it refers to people who use civil disobedience to defend themselves against the destruction of our livelihoods.

The current conflict over this is escalating in Germany’s Rhenish lignite mining region. The occupation and eviction of the village of Lützerath will shape the debate in Germany in the coming days and weeks. We hope that the disputes will remain peaceful, even though many people on both sides of the conflict feel powerless. We look at the issue in this week’s Climate.Table – and will delve deeper into the international significance of the German coal debate in the time ahead.

In the Swiss mountains, on the other hand, people who are far from powerless will be meeting starting next week. For a few years now, the leaders of politics and business have been talking about the climate at the World Economic Forum in Davos. But does that change anything? Three years ago, it seemed like it would: BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, called for serious climate action in its investments. Climate.Table describes what became of it. We also introduce the club of billionaires who have made climate action a personal and professional hobby. And we give a voice to an economist who wants to use Davos for true climate action.

There are other important developments as well: We detail the international effort to rebuild Pakistan, which aims to make the climate change-ravaged country more resilient than before – and could be a blueprint for the hotly debated loss and damage policy. And we tell a bizarre story from Switzerland: The new environment minister, Albert Rösti, now must advance a climate law that he opposed as an MP and against which he and his party, the SVP, have organized a referendum for the summer of 2023. This has now come back to haunt him as a member of the government.

Things remain exciting. And we will stay tuned. Enjoy reading, we look forward to your feedback.

Fink’s 2020 letter to CEOs was a big surprise. The BlackRock chairman warned that climate risks are increasingly becoming investment risks. In plain: Investments in fossil industries are becoming less attractive as they risk losing value in the future. Soon, therefore, there will be a “significant reallocation of capital.” Sustainable investing is the “strongest foundation for client portfolios going forward.” But a stocktaking after three years reveals meager results: BlackRock continues to invest in fossil-fuel industries, approves few climate motions at shareholder meetings, and the dominant business model of passive funds hampers important leverage.

Blackrock wanted to make sustainability the “new standard for investing.” The asset manager:

Blackrock claims to manage “around USD 490 billion in ESG funds“. In 2020, the figure was still a good 200 billion; in 2021, it reached a peak of 509 billion. Just over 6 percent of Blackrock’s managed assets are thus invested in ESG funds. About 25 percent of assets are invested in companies or government-issued assets that have targets to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions (“science-based targets” or equivalent). By 2030, this share is expected to grow to 75 percent as more companies set such targets.

But the climate benefits of many supposedly green funds are limited, says Jan Fichtner, who researches sustainable finance and index funds at the University of Amsterdam. “Many Blackrock funds are now ESG integration funds. But our research shows they’re little different from traditional index funds. They exclude coal companies, but oil and gas companies continue to appear in the funds.”

BlackRock’s divestment from coal is also insufficient. The company can still invest in 80 percent of all companies that operate coal mines or power plants. BlackRock’s exclusion criteria leave too much leeway. BlackRock has not set any specific targets at all for the oil and gas industry. When the Texas pension fund tried to withdraw its investments, BlackRock confessed that the firm was probably the largest investor in fossil fuels. It wanted “to see these companies succeed and prosper.”

BlackRock stresses that many emerging economies continue to rely on fossil fuels. Governments and companies would have to ensure that people continue to have access to reliable and cheap energy. The energy transition will take decades, according to BlackRock. Some developments show it could go faster. Western nations have agreed with initial partner countries on Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETP), which would also involve private backers. Investments in fossil industries and raw materials are also not compatible with the 1.5-degree target.

BlackRock’s coal exclusion does not apply to the company’s passive funds. These account for an immense share of managed assets. In contrast to actively managed funds, the assets are only invested passively, for example in all shares of a stock index. BlackRock’s iShares division now manages over two trillion US dollars in assets in such funds. In addition, trillions more are held in index funds for institutional investors.

The funds are long-term investments. Passive funds can only sell their stake in fossil companies if they leave the stock index that the fund copies. Thus, BlackRock cannot force respective companies to become more sustainable by threatening to sell the shares.

The asset firm wants to overcome this passivity by exercising its voting rights more actively at annual general meetings. Activists welcomed this as a “180-degree turn“. Whereas in 2020 the company approved just 12 percent of all ESG proposals (proposals with an environmental and social focus) at annual general meetings, the figure was as high as 40 percent in 2021. Between June 2021 and 2022, however, the approval rate dropped to 22 percent. The company still lags behind many of its competitors when it comes to approving climate-related motions, as an analysis by ShareAction shows.

Recently, BlackRock argued, more proposals have been too restrictive and interfered too much with the management of the respective companies. The company opposes proposals that called for a phase-out of fossil fuels. And although BlackRock is demanding more transparency from companies regarding climate risks and plans, the asset firm is lobbying against US rules on Scope3 emissions disclosure.

Critics are also critical of BlackRock’s promise to launch more ESG funds. What sounds like a contradiction is rooted in the design of many funds. Sustainable ETFs, for example, would only buy stocks that are already being traded on the stock market, says Tariq Fancy, a former top executive who was in charge of ESG at BlackRock. “Investing in such a fund does not provide additional capital to more sustainable companies or causes,” Fancy says. Fichtner adds, “Many ESG funds cannot invest in capital raises at all. Especially with passive funds, that’s not possible, since they only replicate an index.”

BlackRock itself repeatedly insists that it only manages clients’ money and that it has a statutory “fiduciary duty” to invest the money in the interests of its clients, that is, profitably. Excluding the fossil industries would run counter to this. Between the lines, this means: If customers do not want green investments, our hands are tied.

But are BlackRock’s hands somewhat tied due to competition? If BlackRock were the first asset manager to completely exit fossil fuels, many clients could simply migrate to other providers. For these reasons, it is illusory for BlackRock and other asset managers to bring about a green transformation on their own, says Fancy. Instead, calls for government regulations such as carbon pricing to make fossil fuel industries more expensive. Then investments would no longer be worthwhile and financial flows would be directed much faster to green industries, says former BlackRock sustainability chief Tariq Fancy.

As UN Special Envoy on Climate Ambition and Solutions, the US billionaire is one of the most important links between politics, business and civil society in the United States. Bloomberg made his fortune (currently estimated at about 80 billion dollars) as an investor and owner of his financial information service Bloomberg and a TV station. He was mayor of New York City between 2002 and 2013, after which he became active in climate action. At the UN level, he pushes climate action in business and finance. Bloomberg has used at least 1.5 billion dollars of his private capital to date to fund political campaigns and environmental groups – including the “America’s Pledge” campaign by US business and civil society when US President Donald Trump withdrew the country from the Paris Agreement in 2017. His foundation funds activism for renewables and against fossil fuels, among other causes.

The founder of Amazon and currently the richest man in the world with a wealth of around 170 billion, Jeff Bezos, is funding climate and sustainability goals by 2030 to the tune of ten billion dollars through his “Earth Fund“. And it could become even more if he donates his fortune to charity, as previously announced. Bezos also owns the leading US daily newspaper “Washington Post,” which recently massively expanded its climate coverage. And, together with other corporations and the US government, he is pushing the controversial US Energy Transition Accelerator initiative, which aims to help companies offset their carbon emissions through deals with developing countries.

Marc Benioff is one of his many partners in this effort. The founder of the tech company Salesforce and a mere single-digit billionaire (eight billion dollars) has not only bought the renowned TIME magazine and founded his own ocean research and conservation institute in his home state of California. He has also announced that he will donate 300 million dollars for ecosystem restoration and climate justice.

Bill Gates is also seeking his own path between political lobbying and high-tech enthusiasm for climate action. With his company Breakthrough Energy, the Microsoft founder (129 billion) is heavily investing in technologies that are supposed to solve the climate crisis: Lab meat, fusion and nuclear energy, carbon removal and storage. According to media reports, Gates made sure that US President Biden’s long-controversial Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) investment package was passed in 2022 against much opposition. Many of the technologies supported by Gates are given tax incentives under the IRA. Gates announced plans to reinvest profits from his companies in climate action.

The IRA was also helped into existence by Australian multi-billionaire Andrew Forrest (fortune 18 billion dollars, according to Forbes) – among other things, through a meeting with Democratic US Senator Joe Manchin, who had blocked the bill for a long time. Forrest made his money from lucrative mining in Australia with the Fortescue Metal Group. He blamed the devastating fires in Australia less on climate change and more on poor forest management. He does not deny climate change, but calls for adaptation and restructuring above all. And he sees great economic potential in the production of green hydrogen – which, in turn, Biden’s IRA program would subsidize so heavily in the United States that it could be available cheaper and faster than anywhere else in the world. Forrest struck a deal with Germany’s E.on Group in 2022 for the rapid delivery of large quantities of green hydrogen from Australia – with up to 50 billion dollars expected by 2030.

US billionaire Tom Steyer (1.5 billion dollars) also handles big numbers: The hedge fund manager plans to raise 40 billion dollars with a climate fund for investments in green future technologies. The Democrat ran for the US presidency in 2020 with far-reaching ideas on climate action and social justice. He paid for the more than $340 million campaign from his own funds. He is considered one of the most important financiers of the US Democratic Party and regularly gives large sums of money to environmental and climate groups as well.

Investor John Doerr (12 billion dollars) has also invested in California: He gave more than a billion dollars to the elite Stanford University, which has used the money to establish a “Sustainability School” in his name. This donation, which is gargantuan even by US standards (only Michael Bloomberg has given more to a university), is to be used to research ways to overcome the climate crisis – although critics complain that it is also financed by money from the fossil fuel industry.

In Australia, billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes (12 billion dollars) is fighting the fossil fuel industry with a rich man’s trick: Buy out coal company AGL and quickly shut down the coal business in Australia – while making a buck in the process. Cannon-Brookes, who earned his money with the software Atlassiantlassian, is considered an unconventional thinker who is also planning a 120-square-kilometer solar farm in Australia.

US heiress Aileen Getty is channeling a share of the billions from the oil business that made her family rich into climate action. She supports the Climate Emergency Fund, which finances, among others, the Just Stop Oil campaign and the “Last Generation”. Getty defends the actions of symbolically attacking paintings. Her family sold its shares in the oil business 40 years ago “and I instead vowed to use my resources to take every means to protect life on Earth,” Getty writes.

The Japanese billionaire Masayoshi Son (21 billion dollars) has had many successes and several failures to his name. He ultimately became rich with the software company SoftBank and, after the nuclear disaster in Fukushima in 2011, founded the Renewable Energy Institute in Japan, of which he acts as Chair in addition to his function as a member of the SoftBank board of directors. The institute’s mission: To build a “society based on renewable energy,” to develop technology and business models for this goal, and to network business, research and civil society nationally and internationally.

India’s richest person, Mukesh Ambani, is also now betting on climate-friendly technologies with his billion-dollar fortune. Ambani, the tenth-richest person in the world with a fortune of 90 billion dollars according to the Forbes list, announced in 2022 that his company would invest 76 billion dollars in the Indian solar revolution. Ambani’s company, Reliance Industries, made it big as an oil and energy company. He owns a house with its own hospital and private car showroom and financed his daughter’s wedding with 100 million dollars.

Sir Richard Branson, with a fortune of 2.3 billion dollars, is also part of the climate billionaires. The founder of the “Virgin” chain, which included a record label, megastores, an airline, hotels, telecoms companies and a cruise operator, calls innovations and new technologies the key to solving the climate crisis, just like Bill Gates, for example. Branson announced in 2006 that he would spend a total of three billion dollars on climate action over the next decade, but it is unclear whether it was more than 400 million. The eccentric technophile (like Jeff Bezos) has his own company for space flights, which generate high levels of carbon emissions.

The commitment of business elites to climate change does not meet with universal approval. The accusation is that they often accumulate their wealth by doing business that is harmful to the climate, and that they are more concerned with the show effect or the implementation of their own economic goals. Unlike elected politicians, they act in their own interests and on their own behalf and cannot be held accountable for their actions; if they fail, they cannot be removed from office.

And for some, it is the super-rich who set a bad example. When it comes to their lifestyles with extremely high energy and material consumption, their personal emissions are “several thousand times” higher than the average of ordinary people on earth, criticizes the aid organization Oxfam in an expert report. And their companies’ investments, such as those of energy and cement companies, have an even greater carbon footprint. According to Oxfam, the 125 billionaires at the top of the Forbes list are responsible for carbon dioxide emissions of 393 million tons – one million times more than the average person, who emits around three tons a year.

In December, Rösti was elected by parliament to head the Swiss Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications DETEC. Given his previous role, however, it is unlikely that he will step up climate protection in Switzerland as environment minister. He now has to represent a law that his own party wants to bring down and against which, as a parliamentarian, he initiated a referendum.

Rösti is no stranger to this issue: As president of the association of fuel importers (Avenergy, formerly Swissoil), he has already played a key role in ensuring that the Swiss population rejected a carbon law at the ballot in 2021. The law envisaged:

The law was narrowly rejected with 51.6 percent of votes. And came as a surprise, as all parties except the SVP were in favor of it. A strong mobilization of the population in rural areas contributed to this.

A period of confusion then followed. Subsequently, the state government presented a less ambitious proposal for a new carbon law at the end of last year. It:

However, the goal of the new law remains the same as that of the failed bill: To halve carbon emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels.

In parallel, a non-partisan committee provided more impetus to Swiss climate policy with their “Initiative for a Healthy Climate”, known as the “Glacier Initiative”. The initiative calls for an almost complete ban on imports of fossil fuels from 2050.

Parliament has drafted a counter-proposal. It provides for:

After this draft law, the “Glacier Initiative” withdrew under conditions. The reason: A law would be implemented much faster than via a referendum.

But now the SVP, the party of the new climate and energy minister Albert Rösti, has collected enough signatures for a referendum against this law – and the SVP’s referendum committee included none other than Albert Rösti himself. So the Swiss will vote again in mid-2023 on the way forward in climate policy.

The Swiss government is based on the principle of collegiality: All seven members of the Federal Council represent the opinion of the entire government, to the public, and defend it in the voting campaigns. Albert Rösti will therefore have to defend a climate protection law right at the beginning of his term in office, which his party wants to prevent and which he actively opposed himself while he was still a member of parliament.

However, his options are limited: He will not be able to turn Switzerland’s climate policy upside down, as his proposals will have to find a majority in the Federal Council. And when asked whether he wanted to play party politics or follow the principle of collegiality, he said chose the principle of collegiality after his election. Climate protection, he said, “plays an important role.” Decarbonization was necessary, but “enough electricity must be produced.”

The leader of the Green Party, Aline Trede said: “I am not afraid of Mr. Rösti in the Uvek. But we will keep a close eye on what he does, and especially, what he doesn’t do.” And Marcel Hanggi of the Glacier Initiative Committee said, “We expect Federal Councillor Rösti to represent the climate protection bill regardless of his party opinion. After all, Switzerland has committed to the 1.5-degree target with the Paris Agreement.”

Rösti can slow down progress by making less ambitious motions. But he cannot slow things down too much either: Under the Paris climate protection agreement, Switzerland has committed to cutting carbon emissions in half by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. And the country is already behind schedule, having failed to meet its previous target of minus 20 percent by 2020. And even with the measures in the planned new carbon law and even the government’s counter-proposal, which the SVP referendum is now seeking to overturn, Switzerland will likely miss its Paris goals. Priscilla Imboden from Zurich

The international funding commitments far exceeded Pakistan’s expectations of roughly 8.15 billion dollars: While the government had expected about 8.15 billion dollars in aid for reconstruction, the January 9 Geneva conference resulted in funding pledges of more than 9 billion dollars. The money, from nearly 40 donor countries, multilateral banks, and agencies, will be used to help with recovering from last summer’s extreme monsoons and floods.

The sheer scale of damage and humanitarian crisis affecting 33 million people of whom nearly half are children has rallied the global community around Pakistan. Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif was clear that his country is not capable of handling reconstruction on its own. Speaking at the high-level inaugural session of the conference, he said, “For recovery and reconstruction, the minimum requirement is 16.3 billion dollars. Half of it is proposed to be met from domestic resources and the other half from development partners and friends.”

The conference is the first run of a model for providing climate finance to address loss and damage. The onus of providing funds is still on the “donor-developed” countries, but there is a plan to match the use of the funds.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres said, “We also need to right a fundamental wrong. Pakistan is doubly victimized by climate chaos and a morally bankrupt global financial system. We need creative ways for developing countries to access debt relief and concessional financing when they need it most. Above all, we need to be honest about the brutal injustice of loss and damage suffered by developing countries because of climate change.” Much more than 16 billion would be needed in the longer term.

Housing, agriculture and livestock, transport and communication were the sectors most impacted by the floods. In terms of regions, the province of Sindh was the worst affected, followed by Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Punjab.

A Disaster Needs Assessment by UNDP and the World Bank (PDNA) estimated total damages to exceed 14.9 billion dollars, and total economic losses of about 15.2 billion dollars. Funding required for a resilient rehabilitation and reconstruction is estimated to be at least 16.3 billion dollars. This estimate does not include investments required to support Pakistan’s adaptation to climate change and overall resilience to future climate shocks.

At the conference in Geneva, Pakistan presented its plan for reconstruction: The Resilient Recovery, Rehabilitation and Reconstruction (4RF) Framework provides:

The plan proposes interventions prioritized

They include reforms in political structures, investments/programs for recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction, and institutional effectiveness. So far, however, many details remain unclear.

Besides the financial commitment, the conference agreed to a structured process of support for Pakistan’s resilient recovery. Key elements of the plan include project preparation, developing a financing plan, enhancing capacity and long-term resilience.

These interventions will span four strategic recovery objectives:

Projects include plans to designate areas protected against flooding, new building codes, flood-proof police stations and prisons, and better collection of meteorological data and early warning systems.

The plans thus meet the demand of UN Secretary-General António Guterres. Guterres stressed at the conference that reconstruction efforts must go beyond repairing the damage caused by the floods. Efforts must include “initiatives to address daunting social, environmental and economic challenges. Reconstructing homes and buildings. Re-designing public infrastructure – including roads, bridges, schools and hospitals. Jump-starting jobs and agriculture.”

Nearly half of the 9 billion dollars pledged came from the Islamic Development Bank (4.2 billion dollars), another 2 billion dollars were committed by the World Bank and Saudi Arabia pledged 1 billion dollars, the European Union and China were among the other major donors.

Taking to social media, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Sharif said “the world witnessed yesterday how the nations can come together in a show of solidarity to create a model of win-win partnership to lift suffering humanity out of tragedy”.

As Pakistan transitions into long-term reconstruction, priorities should include financing the most immediate and time-critical components of the 4RF including urgent social expenditures aimed at preventing health crises, mitigating the impact of winter as well as the rains in the next monsoon season and restoring livelihoods. The process must focus on building resilience and increasing Pakistan’s capacity to withstand future shocks.

Part of the program also includes a detailed financing plan, which also provides for fostering public-private partnerships. A facility will be established, or the UNDP-supported Project Preparation Facility already established within Pakistan’s Ministry of Finance will be reinforced, with a dedicated fund to finance the professional development by qualified consultants of viable projects selected from the 4RF framework, for official, private and public-private financing and/or investment. An “International Partners’ Support Group to Pakistan’s Resilient Recovery, Rehabilitation and Reconstruction” will be established under the leadership of the Pakistani government. The Group will assist Pakistan develop concrete plans and projects and help secure financial and other commitments of support for the implementation of these plans and projects over the coming years.

Jan. 12; 2 p.m. – online

Webinar Engaging citizens as decision makers in clean energy transitions

The International Energy Agency’s webinar will explore key issues in social dialogue and citizen engagement as part of decision making processes. Info

Jan. 16-20; Davos

Summit World Economic Forum

The Annual Meeting will convene leaders from government, business, and civil society to address the state of the world and discuss priorities for the year ahead. Info

In an open letter to the government of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, several climate scientists call for a halt to the eviction of Lützerath. As the researchers of Scientists for Future write in their letter addressed to Minister-President Hendrik Wüst, Minister for Economic Affairs Mona Neubaur and Minister of the Interior Herbert Reul, the village has “become a symbol”. They cite “substantial scientific doubts about the acute necessity of an evacuation.” A moratorium would offer “the opportunity for a transparent dialog process with all those affected” and would significantly increase the credibility of German climate policy.

In October 2022, the government of North Rhine-Westphalia, the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology and the German energy company RWE agreed to bring forward the phase-out of coal in North Rhine-Westphalia to 2030. In return, larger quantities of lignite may be mined in the short term. Part of the agreement is that the area of Lützerath may be mined.

On the question of whether the coal under Lützerath really still needs to be mined, various expert reports have come to different conclusions. The government of North Rhine-Westphalia relies on calculations according to which mining is necessary to guarantee Germany’s energy security. Scientists for Future points to several expert opinions that disagree with this.

Manfred Fischedick, Scientific Director of the Wuppertal Institute, calls the decision for or against Lützerath one “between plague and cholera”. If Lützerath were to be preserved, other towns would have to make way for the open pit mine. In addition to energy and climate policy aspects, Fischedick also cites water management and open pit planning factors as reasons:

“The state government has understandably chosen to preserve villages where people still live today,” Fischedick said.

To ensure that Germany achieves its climate targets, however, Lützerath is not the decisive factor, but the European Union’s emissions trading system, says Ottmar Edenhofer, Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “As long as the cap on greenhouse gas emissions remains really hard and falls, and the carbon price is effective, we can temporarily burn more coal – because this leads to emissions savings elsewhere,” Edenhofer says. Even if Lützerath is excavated: Coal has no future. ae

Scientists from the Global South are hardly represented in the author teams of the most important climate studies. This is the result of a survey by Carbon Brief. According to the survey, the 25 climate studies that receive the most media attention were predominantly written by men from the Global North:

The ten climate studies with the widest reach in traditional and social media show the breadth of the climate crisis. They deal with:

More than eight million new jobs will be created worldwide in the field of green technologies by 2030. This is according to a new Energy Technology Perspectives 2023 analysis by the IEA, which was published today. If countries meet their climate targets by 2030, the market for green products such as solar panels, wind turbines, EV batteries, heat pumps and electrolyzers for hydrogen will increase:

However, the IEA warns that the supply chains and production of these goods are concentrated in a few countries. China dominates manufacturing for all the technologies listed. The three largest producing countries account for at least 70 percent of production for all technologies listed. There is also a sizeable geographic concentration for feedstocks, such as lithium and cobalt.

“As we have seen with Europe’s reliance on Russian gas, when you depend too much on one company, one country or one trade route – you risk paying a heavy price if there is disruption,” IEA Chairman Fatih Birol said. Birol said he is therefore pleased that many countries are investing in building production capacity. However, competition must remain fair, he added. The IEA report also stresses the importance of global trade in green technology goods. nib