On Tuesday, the global public paid particular attention to US President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address. Xi Jinping’s keynote speech, on the other hand, attracted less attention from the world public but all the more from us at China.Table. Xi spoke rather unwieldily in the old CP manner, but even if his rhetoric was nowhere near as dazzling as Biden’s, there were good reasons to listen to him carefully.

This is what our author in Beijing, Fabian Kretschmer, did. Xi warns against “Westernization” and praises the Chinese way as a guide for the Global South in his speech. This does not sound at all conciliatory toward the West, as some observers had recently hoped, but rather like a declaration of war.

Our second text is also about the “Chinese world order”. Fabian Peltsch spoke with Canadian history professor David Ownby, who is intensively engaged in the sociopolitical debates among China’s intellectuals. These are surprisingly lively.

Even as lively as the debates among German sinologists when it comes to cooperation with institutions in the People’s Republic? While some demand maximum transparency, others fear potentially endangering critical minds in China, as Marcel Grzanna describes the dispute.

Both sides agree on one point: More China expertise is needed, especially in those research areas that have so far paid little attention to the political situation. This debate could change that.

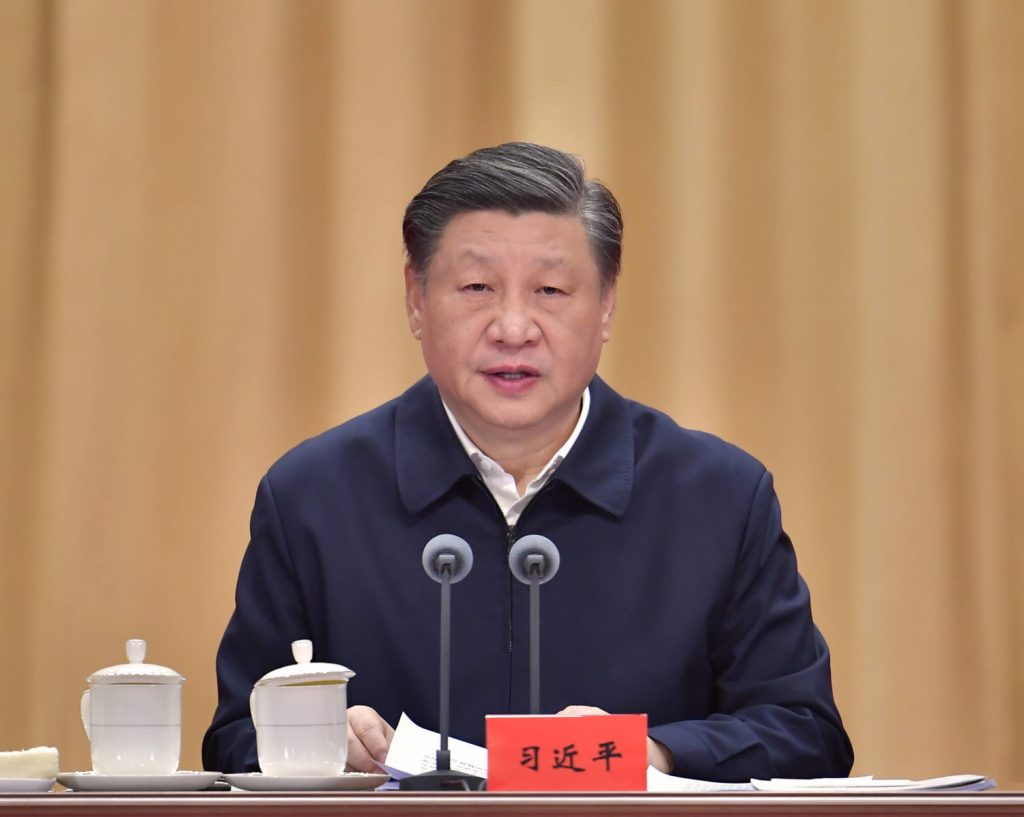

When the 69-year-old state and party leader Xi Jinping delivers his first keynote speech in a long time, the world public has good reason to listen more closely. After all, Xi outlines China’s political thrust for the next few years – just one month before he will begin his third term in office at the National People’s Congress.

On Tuesday, dressed as always in a white shirt and dark blue work jacket, he appeared before his leading cadres at the Central Party School of the Chinese Communist Party. Xi’s core message bristled with self-confidence: China had “debunked the myth that modernization equals Westernization.” What’s more, the Chinese way serves as a model for the developing countries of the Global South.

The People’s Republic has been trying to export its autocratic model of government abroad for several years. A paradigm shift can be observed in the argumentation of the state leadership: Beijing used to reject concepts such as “democracy” and “human rights” as Eurocentric, but it has now appropriated them for itself.

Thus, the Chinese leadership simply claims that it represents a better, “holistic democracy” and also promotes human rights much more strongly than, for example, the United States. In particular, the right to economic development is emphasized; after all, no other country in the world has lifted so many people out of poverty in such a short time as China.

In any case, Xi said in his speech, since coming to power in 1949, the Communist Party has completed an industrialization process in just a few decades that would have taken the “developed countries of the West several hundred years”.

The impudence Xi displays certainly seems strange in view of the current news situation. Just last weekend, the balloon affair caused US Secretary of State Antony Blinken to cancel his long-awaited visit to Beijing. Even if Xi can hardly be held directly responsible for this foreign-policy embarrassment, he is indirectly very much so: After all, he has shaped a system in which hierarchies and ideological control have become increasingly strict – and criticism can only be formulated with difficulty.

One of the immediate consequences is an increased susceptibility to mistakes, as the dogmatic adherence to the radical zero-Covid strategy has impressively exposed. The ideologically motivated, scientifically unsubstantiated lockdowns have massively slowed down the national economy, especially in the previous year.

Still, Xi is convinced that China’s state officials must continue to work to find a more “efficient” way than capitalism and to make society more equitable. What sounds noble on paper looks less rosy in reality: Most recently, Xi’s erratic economic policies have contributed to higher youth unemployment after massive regulation of the country’s leading tech companies, for example. Whether the People’s Republic will succeed in getting a grip on the massive inequality without throttling the entire national economy remains an open question.

For Xi Jinping, however, one goal stands above all others – the Communist Party’s claim to power: “Only through unswerving adherence to leadership by the party” could the country have a “bright future”. Without the party, however, the country would “lose its soul”. Fabian Kretschmer

Foreign countries perceive social debates in China primarily through the state media’s synchronized propaganda. It may therefore come as a surprise to many that there is also a lively culture of discourse in China. It eludes state constraints and tries to find philosophical solutions for Chinese issues beyond Marx and Mao.

David Ownby, a history professor at the University of Montreal, has set out to publicize China’s intellectual life outside the People’s Republic. To this end, he has launched the online project “Reading the China Dream“, which regularly translates selected texts by contemporary Chinese thinkers into English.

“China is the world’s second-largest economy and the main competitor to the US. Yet hardly anyone knows that there are active, relatively independent intellectuals who have interesting things to say about China and the world,” Ownby tells China.Table in an interview. China’s intellectuals are on the cutting edge, he says.

Their approaches and theories, he says, are more similar to those of Western philosophers than we think. “Even intellectuals who hate American hegemony argue against it in largely Western terms,” Ownby says. Because many of them can’t be understood as dissidents, their works are hardly received outside China, he laments. “I think this represents a huge gap in our knowledge” – a blind spot in our worldview.

Although topics such as Taiwan’s sovereignty or a critique of the Communist Party’s claim to power are taboo, China’s thinkers can still negotiate many issues publicly. “Many of them are looking for new ways to tell China’s story,” Ownby says.

A popular philosophical concept, for example, is Tianxia 天下, the order “under one sky,” which was described as determining the fate of the world as early as during the Zhou Dynasty 3,000 years ago. Contemporary thinkers such as Zhao Tingyang, Liang Zhiping and Xu Jilin attempt to apply the idea to the present. They see Tianxia not in terms of China nationalistically but in terms of a global political order. According to their interpretation, Tianxia contains the peaceful coexistence of all peoples with great mutual benefit.

In demarcation from the “imperialist exploitation” of the most recent Western-influenced world history, the concept fits in perfectly with Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative. But the latter instead babbles about “win-win” and a “community of humanity’s destiny“. Ownby believes that the newly conceived Tianxia concept has long been accepted in the party’s inner circle of power.

Most Chinese intellectuals are not easily instrumentalized. The party jargon of the rulers seems outdated, even embarrassing to many, says Onwby. Within the history of Chinese ideas, they prefer to refer to thinkers like Kang Youwei rather than Mao Zedong. Kang was a mastermind of reforms to modernize China in the late 19th century. He advocated for the preservation of traditions in the modern world – following Japan’s example.

Xi Jinping, on the other hand, whose thoughts are now a compulsory program at Chinese universities, sees himself as an important thinker. However, the majority of modern Chinese philosophers do not consider the head of state to be his equal.

But intellectuals exploit Xi’s ambitions for their own purposes, Ownby says. They, therefore, also discuss essays by Xi or members of the Central Committee. If they have to, they sometimes switch to party jargon to do so. The best example is Cai Xia 蔡霞, a retired professor from the Central Party School in Beijing. Cai has delivered a solid defense of liberal democratic values – but in the language of the Chinese Communist Party.

Many intellectuals also find the aggressively lecturing wolf warrior attitude of Chinese diplomats and journalists “repulsive,” Ownby believes. “I don’t see much overt pacifism, but there are many liberals who are deeply concerned about populism and nationalism in China.” They all have in common that they want their thoughts to provide Chinese solutions to Chinese problems and perhaps even establish an ideology that is more convincing to the people than the stale underbelly of “Chinese-style socialism”.

For example, Yao Yang, an economist at Peking University, has been working for several years on a concept he calls “Confucian liberalism” – a modernized version of Confucian texts that he believes is an improvement on the liberalism practiced in the West.

How can Germany itself build up more China competence and approach research cooperation with the People’s Republic less naively? The possible answers to these questions repeatedly lead to intense debates within the German China and sinology scene. Most recently, the proposal to introduce a central register for research cooperation with partners from autocratically ruled states met with criticism.

The business ethicist Alicia Hennig and the political scientist Andreas Fulda had brought the idea for a central register of researchers into play during an interview with the German news magazine Der Spiegel. While proponents see the greatest possible transparency as an important means of preventing the appropriation of German research and its misuse, opponents fear a vulnerability with drastic consequences for those involved.

“Transparency is important, especially in cooperation with the People’s Republic of China, but it must have limits,” says Bjoern Alpermann from the University of Wuerzburg. The sinologist and Xinjiang expert believes that a duty of disclosure would potentially endanger critical minds among Chinese colleagues in particular. He himself has already concealed the names of Chinese co-authors or collaborators of his work in the past for fear of exposing them to the arbitrariness of the power apparatus.

For their part, proponents of the register put forward good arguments. Hennig warns that “a lack of transparency could lead to the concealment of undesirable links to the Chinese military or the Communist Party”. When collaborating with Chinese researchers, it must be taken into account that the “entire Chinese education sector should exclusively serve the goals of the party,” Hennig had warned in a position paper in China.Table.

According to Hennig, potential Chinese research partners are selected based on their patriotic qualifications. It is illusory to assume independence, especially since Chinese laws require all citizens of the country to cooperate with intelligence services.

However, there is disagreement about the definition of transparency. Fulda had said in Der Spiegel, “You would have to disclose the terms of any cooperation.” Compromises would have to be documented and verifiable. However, an “absolute understanding of transparency” should not be derived from this. Hennig herself concedes that no one could seriously want 100 percent transparency. For Alpermann, this raises the question of which cooperations should be disclosed to whom in concrete terms. And who would have the right to check them?

Alpermann fears that a register would even provide the Chinese security authorities with starting points “to exert pressure on German scientists”. Such “relational repression” is common practice in China, he says. Should there be self-censorship in China research, this would further aggravate the situation.

The debate is being conducted in a decidedly emotional manner, partly because there is a latent accusation that too much vested interest within China research is clouding a clear view of the risks. “The current China debate in Germany is too strongly shaped by people with agendas,” according to Der Spiegel. Economic sinologist Doris Fischer of the University of Wuerzburg just rolled her eyes when she read the interview, she commented on social media.

Alpermann disagrees with the accusation that sinology in Germany has been infiltrated too far, especially since it is not substantiated. Those who, like Hennig and Fulda, call for China expertise oriented toward democratic values are insinuating that all sinologists who work at universities or in the public sector are violating their oath of office to the free democratic basic order. “That is simply slander,” Alpermann says.

But despite all the controversy, proponents and opponents of a central registry agree that in science, all autocracies must generally be handled more cautiously in the future. Alpermann sees the risks, particularly in scientific and technical disciplines, whose findings could flow into control or surveillance tools, for example. Hennig and Fulda, on the other hand, also point to the risks in the humanities and social science fields, whose findings could involuntarily provide ideological support for the Chinese regime.

The dilemma is to find a middle ground that considers both sides’ arguments. “We have not yet addressed the specific parameters of such a registry. These would have to be collectively debated and negotiated. So any excitement about this is premature,” according to Hennig.

But in any case, it should by no means be just about China research. It does help to gain a better understanding of the People’s Republic and to generate political measures on this basis. But all research collaborations in all disciplines are affected by the problem. This is because there is very rarely sufficient China expertise available. Yet it is precisely this expertise that is needed to assess the risks involved in collaborations with the Chinese side and to develop guidelines for overcoming these risks.

Following the launch of a Chinese surveillance balloon suspected of being used for espionage purposes over US territory, US President Joe Biden issued a stark warning to the leadership in Beijing. “If China threatens our sovereignty, we will act to protect our country. And we did,” Biden said during his official State of the Union address in Washington Tuesday night.

He called on Republicans and Democrats to be more united in his speech to both chambers of the US Congress. “Let’s be clear: Winning the competition should unite all of us.” But he said he was determined to work with China where US interests could be advanced for the good of the world. He said he has made it clear to Chinese President Xi Jinping in the past that the US seeks competition, not conflict.

China’s leadership nevertheless reacted angrily. “It is not the practice of a responsible country to slander a country or restrict the country’s legitimate development rights under the pretext of competition,” said Mao Ning, spokeswoman for the Foreign Ministry in Beijing. China is not afraid of competition with the US, she said, but is “opposed to the whole relationship between China and the US being defined in terms of competition.” flee

According to the Pentagon, it had sought talks with Beijing immediately after the alleged Chinese spy balloon was shot down. However, the Chinese leadership rejected the offer. This was confirmed by the spokesman of the US Department of Defense, Pat Ryder, on Tuesday.

He said the Pentagon regrets the rejection. “We believe that maintaining open lines of communication between the United States and the People’s Republic of China is important to managing the relationship responsibly,” Ryder continued. At moments like this, he said, communication between the two countries’ militaries is especially important.

As reported by the Washington Post, the balloon is part of an extensive surveillance program. Such balloons have for years collected information on military installations in countries and areas of strategic interest to China, the newspaper reported, citing US intelligence circles. These included Japan, India, Vietnam, Taiwan and the Philippines, for example. The balloons would operate in part from the coast of the southern Chinese island of Hainan. They have been spotted over five continents so far, he said.

“What the Chinese have done is taken an unbelievably old technology, and basically married it with modern communications and observation capabilities to try to glean intelligence on other nations’ militaries,” the Washington Post quotes an unnamed US government official as saying.

The US State Department has sent detailed information about the surveillance balloons to each US embassy to share with allies and partners, according to the newspaper. “There has been great interest in this on the part of our allies and partners,” the government official said. flee

Despite all political warnings of excessive dependence, German trade with China rose to a record level last year. Goods worth around €298 billion were traded between the two countries. This is an increase of around 21 percent compared to 2021, according to current data from the Federal Statistical Office. The statistics authority thus confirms data from Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI), which was already available last week.

The People’s Republic thus remained Germany’s most important trading partner for the seventh year in succession, followed by the USA (around €248 billion) and the Netherlands (just under €234 billion). “Trade flows don’t change overnight,” commented Max Zenglein, chief economist at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics). “The country will remain our most important trading partner for quite some time.”

In 2022, goods worth €191 billion were imported from the People’s Republic, a good third more than in 2021. Germany mainly buys electronics and electrical engineering in China, but also textiles/clothing, machinery and chemical products. Exports of goods “Made in Germany” to China, on the other hand, increased by only 3.1 percent to around €107 billion. Germany’s trade balance with the People’s Republic thus shows a deficit of around €84 billion.

“China is important as an export market but far less important than it appears in the public perception. The United States is much more important for German exporters,” Zenglein said. “Exports to China are exhausted; no more big jumps are to be expected. We have reached a plateau here.”

Politicians and scientists are nevertheless alarmed in view of the strong interdependence in some areas. “The main problem is Germany’s dependence on China for critical raw materials, which are needed for the transition to cleaner energy and transport,” Lukas Menkhoff, head of the global economy department at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), told Reuters. Germany imports about two-thirds of so-called rare earth metals from China. The metals are indispensable in batteries, semiconductors, and magnets in electric cars. rtr

Car sales have fallen significantly despite the holidays surrounding the Chinese New Year. According to the industry association PCA, 1.29 million vehicles were sold in January, about 38 percent fewer than in the same month last year. PCA announced the figures on Wednesday.

More environmentally friendly cars, in particular, sold poorly. Sales of EVs and plug-in hybrids fell by more than 48 percent compared with December. The association explained this, among other things, with the discontinuation of subsidies for some EVs. Many customers had, therefore, already brought forward their purchases to the final quarter of 2022.

In addition, people in China were able to travel freely for the Chinese New Year for the first time since 2020 after Covid restrictions were lifted on Dec. 7. Many production lines were stopped for longer than usual. flee

Marc Matten’s interest in China began with a visit to a flea market in the 1990s. While still in school, he stumbled across a book by Edgar Snow, the US journalist who recorded his encounter with Mao Zedong in the world-famous bestseller “Red Star Over China”. Matten was fascinated. “A little later, when our city library was sorting out old holdings, I took everything that had to do with China.”

After graduating from high school, Matten studied sinology, Japanese studies and economics in Bonn, traveling to Changchun and Tokyo. In the beginning, he says, mainly “mundane reasons” brought him to China. “I was lured by the economic growth and the prospect of a corporate career.”

In Changchun, he hoped to land an internship at VW, but then his interest changed radically and he began to study modern Chinese history. He wrote his master’s thesis on the nationalism of Chinese students in Japan, and in 2009 he received his doctorate with a dissertation on the limits of Chinese in the foundation of a national identity in China at the beginning of the 20th century.

To this day, Matten’s research is guided by how ideas of different origins shape debates in and about China. How are nationalism, emancipation, freedom, and in general, the world as a concept of order discussed in China? What influence did modernization currents in the 20th century have on this? “Eurocentrism has long defined the so-called West as the norm, whether in terms of democracy, human rights or social structures. To me, this view is too simplistic.”

Even at the end of the Qing dynasty, he said, it was evident that Western ideas were not simply adopted. “Instead, narratives from the past were often reactivated, for example, to establish the nation as a political order or to proclaim the renaissance of Confucianism.”

Since earning his doctorate, Matten has been teaching the contemporary history of China at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. He regrets that there is still too little knowledge about China in Germany and Europe: “In my seminars, I talk about the asymmetry of not knowing – historians in Germany know less about Chinese history than vice versa, and the same is true for the disciplines of philosophy, religious studies, political science.” We need to read and hear significantly more about China, he stresses, “especially from Chinese voices”. But there’s a catch to all this: the language barrier. “There’s a lack of translations, and we sinologists should get on that, too.”

Whether Matten himself will get around to translating anytime soon is uncertain. In addition to his teaching, he works on a project on how to write global history from a non-Western perspective. “Party historians in China like to argue that there is such a thing as global history with Chinese characteristics, but what form it should take is unclear.” This debate will keep us busy in the coming years, Matten is sure. Svenja Napp

Klaus Buechele has been the new Senior Manager for Quality Assurance for Audi at FAW-Volkswagen in Changchun since the beginning of the month. Buechele was previously Head of Mobility Service at Audi AG in Neckarsulm.

Zhang Yuzhuo is the new party secretary of the State Council’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, replacing Hao Peng. Zhang had only taken over as head of the China Association for Science and Technology (CAST) in August 2021. Prior to that, he was chairman of Sinopec, China’s largest natural gas and oil company, for just under a year and a half.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Hot pot in a tube: At this restaurant in Chongqing, diners can simmer their outdoor hot pot in converted and illuminated cement tubes.

On Tuesday, the global public paid particular attention to US President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address. Xi Jinping’s keynote speech, on the other hand, attracted less attention from the world public but all the more from us at China.Table. Xi spoke rather unwieldily in the old CP manner, but even if his rhetoric was nowhere near as dazzling as Biden’s, there were good reasons to listen to him carefully.

This is what our author in Beijing, Fabian Kretschmer, did. Xi warns against “Westernization” and praises the Chinese way as a guide for the Global South in his speech. This does not sound at all conciliatory toward the West, as some observers had recently hoped, but rather like a declaration of war.

Our second text is also about the “Chinese world order”. Fabian Peltsch spoke with Canadian history professor David Ownby, who is intensively engaged in the sociopolitical debates among China’s intellectuals. These are surprisingly lively.

Even as lively as the debates among German sinologists when it comes to cooperation with institutions in the People’s Republic? While some demand maximum transparency, others fear potentially endangering critical minds in China, as Marcel Grzanna describes the dispute.

Both sides agree on one point: More China expertise is needed, especially in those research areas that have so far paid little attention to the political situation. This debate could change that.

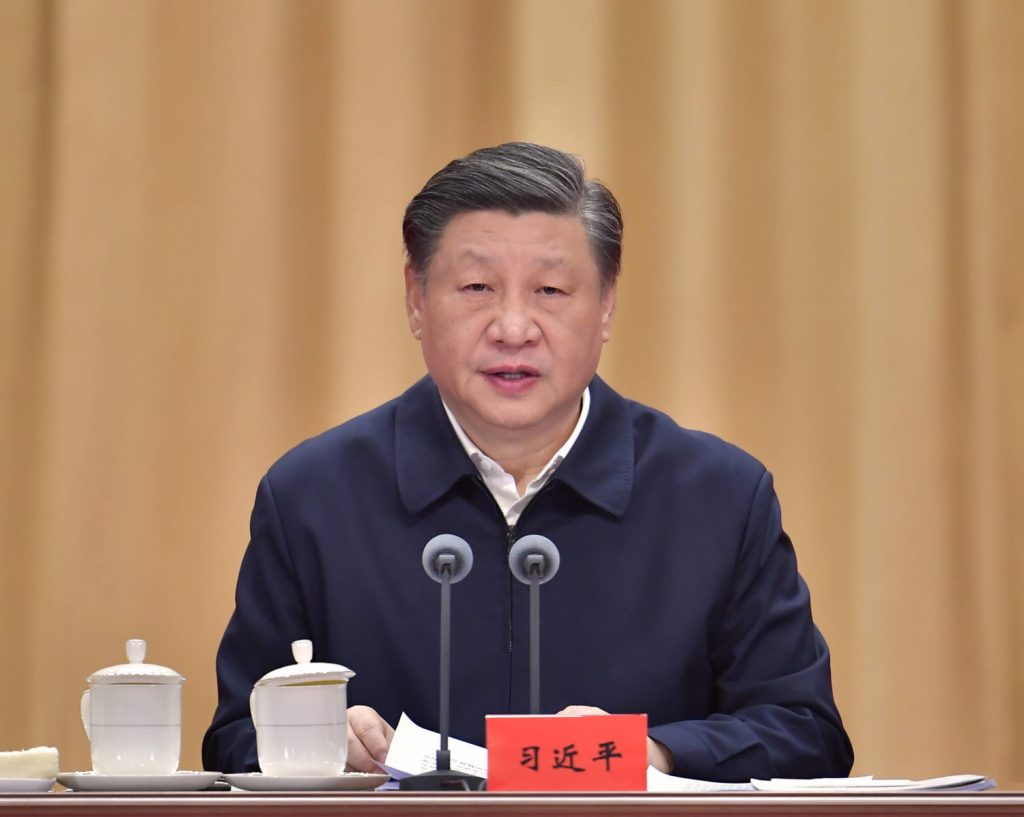

When the 69-year-old state and party leader Xi Jinping delivers his first keynote speech in a long time, the world public has good reason to listen more closely. After all, Xi outlines China’s political thrust for the next few years – just one month before he will begin his third term in office at the National People’s Congress.

On Tuesday, dressed as always in a white shirt and dark blue work jacket, he appeared before his leading cadres at the Central Party School of the Chinese Communist Party. Xi’s core message bristled with self-confidence: China had “debunked the myth that modernization equals Westernization.” What’s more, the Chinese way serves as a model for the developing countries of the Global South.

The People’s Republic has been trying to export its autocratic model of government abroad for several years. A paradigm shift can be observed in the argumentation of the state leadership: Beijing used to reject concepts such as “democracy” and “human rights” as Eurocentric, but it has now appropriated them for itself.

Thus, the Chinese leadership simply claims that it represents a better, “holistic democracy” and also promotes human rights much more strongly than, for example, the United States. In particular, the right to economic development is emphasized; after all, no other country in the world has lifted so many people out of poverty in such a short time as China.

In any case, Xi said in his speech, since coming to power in 1949, the Communist Party has completed an industrialization process in just a few decades that would have taken the “developed countries of the West several hundred years”.

The impudence Xi displays certainly seems strange in view of the current news situation. Just last weekend, the balloon affair caused US Secretary of State Antony Blinken to cancel his long-awaited visit to Beijing. Even if Xi can hardly be held directly responsible for this foreign-policy embarrassment, he is indirectly very much so: After all, he has shaped a system in which hierarchies and ideological control have become increasingly strict – and criticism can only be formulated with difficulty.

One of the immediate consequences is an increased susceptibility to mistakes, as the dogmatic adherence to the radical zero-Covid strategy has impressively exposed. The ideologically motivated, scientifically unsubstantiated lockdowns have massively slowed down the national economy, especially in the previous year.

Still, Xi is convinced that China’s state officials must continue to work to find a more “efficient” way than capitalism and to make society more equitable. What sounds noble on paper looks less rosy in reality: Most recently, Xi’s erratic economic policies have contributed to higher youth unemployment after massive regulation of the country’s leading tech companies, for example. Whether the People’s Republic will succeed in getting a grip on the massive inequality without throttling the entire national economy remains an open question.

For Xi Jinping, however, one goal stands above all others – the Communist Party’s claim to power: “Only through unswerving adherence to leadership by the party” could the country have a “bright future”. Without the party, however, the country would “lose its soul”. Fabian Kretschmer

Foreign countries perceive social debates in China primarily through the state media’s synchronized propaganda. It may therefore come as a surprise to many that there is also a lively culture of discourse in China. It eludes state constraints and tries to find philosophical solutions for Chinese issues beyond Marx and Mao.

David Ownby, a history professor at the University of Montreal, has set out to publicize China’s intellectual life outside the People’s Republic. To this end, he has launched the online project “Reading the China Dream“, which regularly translates selected texts by contemporary Chinese thinkers into English.

“China is the world’s second-largest economy and the main competitor to the US. Yet hardly anyone knows that there are active, relatively independent intellectuals who have interesting things to say about China and the world,” Ownby tells China.Table in an interview. China’s intellectuals are on the cutting edge, he says.

Their approaches and theories, he says, are more similar to those of Western philosophers than we think. “Even intellectuals who hate American hegemony argue against it in largely Western terms,” Ownby says. Because many of them can’t be understood as dissidents, their works are hardly received outside China, he laments. “I think this represents a huge gap in our knowledge” – a blind spot in our worldview.

Although topics such as Taiwan’s sovereignty or a critique of the Communist Party’s claim to power are taboo, China’s thinkers can still negotiate many issues publicly. “Many of them are looking for new ways to tell China’s story,” Ownby says.

A popular philosophical concept, for example, is Tianxia 天下, the order “under one sky,” which was described as determining the fate of the world as early as during the Zhou Dynasty 3,000 years ago. Contemporary thinkers such as Zhao Tingyang, Liang Zhiping and Xu Jilin attempt to apply the idea to the present. They see Tianxia not in terms of China nationalistically but in terms of a global political order. According to their interpretation, Tianxia contains the peaceful coexistence of all peoples with great mutual benefit.

In demarcation from the “imperialist exploitation” of the most recent Western-influenced world history, the concept fits in perfectly with Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative. But the latter instead babbles about “win-win” and a “community of humanity’s destiny“. Ownby believes that the newly conceived Tianxia concept has long been accepted in the party’s inner circle of power.

Most Chinese intellectuals are not easily instrumentalized. The party jargon of the rulers seems outdated, even embarrassing to many, says Onwby. Within the history of Chinese ideas, they prefer to refer to thinkers like Kang Youwei rather than Mao Zedong. Kang was a mastermind of reforms to modernize China in the late 19th century. He advocated for the preservation of traditions in the modern world – following Japan’s example.

Xi Jinping, on the other hand, whose thoughts are now a compulsory program at Chinese universities, sees himself as an important thinker. However, the majority of modern Chinese philosophers do not consider the head of state to be his equal.

But intellectuals exploit Xi’s ambitions for their own purposes, Ownby says. They, therefore, also discuss essays by Xi or members of the Central Committee. If they have to, they sometimes switch to party jargon to do so. The best example is Cai Xia 蔡霞, a retired professor from the Central Party School in Beijing. Cai has delivered a solid defense of liberal democratic values – but in the language of the Chinese Communist Party.

Many intellectuals also find the aggressively lecturing wolf warrior attitude of Chinese diplomats and journalists “repulsive,” Ownby believes. “I don’t see much overt pacifism, but there are many liberals who are deeply concerned about populism and nationalism in China.” They all have in common that they want their thoughts to provide Chinese solutions to Chinese problems and perhaps even establish an ideology that is more convincing to the people than the stale underbelly of “Chinese-style socialism”.

For example, Yao Yang, an economist at Peking University, has been working for several years on a concept he calls “Confucian liberalism” – a modernized version of Confucian texts that he believes is an improvement on the liberalism practiced in the West.

How can Germany itself build up more China competence and approach research cooperation with the People’s Republic less naively? The possible answers to these questions repeatedly lead to intense debates within the German China and sinology scene. Most recently, the proposal to introduce a central register for research cooperation with partners from autocratically ruled states met with criticism.

The business ethicist Alicia Hennig and the political scientist Andreas Fulda had brought the idea for a central register of researchers into play during an interview with the German news magazine Der Spiegel. While proponents see the greatest possible transparency as an important means of preventing the appropriation of German research and its misuse, opponents fear a vulnerability with drastic consequences for those involved.

“Transparency is important, especially in cooperation with the People’s Republic of China, but it must have limits,” says Bjoern Alpermann from the University of Wuerzburg. The sinologist and Xinjiang expert believes that a duty of disclosure would potentially endanger critical minds among Chinese colleagues in particular. He himself has already concealed the names of Chinese co-authors or collaborators of his work in the past for fear of exposing them to the arbitrariness of the power apparatus.

For their part, proponents of the register put forward good arguments. Hennig warns that “a lack of transparency could lead to the concealment of undesirable links to the Chinese military or the Communist Party”. When collaborating with Chinese researchers, it must be taken into account that the “entire Chinese education sector should exclusively serve the goals of the party,” Hennig had warned in a position paper in China.Table.

According to Hennig, potential Chinese research partners are selected based on their patriotic qualifications. It is illusory to assume independence, especially since Chinese laws require all citizens of the country to cooperate with intelligence services.

However, there is disagreement about the definition of transparency. Fulda had said in Der Spiegel, “You would have to disclose the terms of any cooperation.” Compromises would have to be documented and verifiable. However, an “absolute understanding of transparency” should not be derived from this. Hennig herself concedes that no one could seriously want 100 percent transparency. For Alpermann, this raises the question of which cooperations should be disclosed to whom in concrete terms. And who would have the right to check them?

Alpermann fears that a register would even provide the Chinese security authorities with starting points “to exert pressure on German scientists”. Such “relational repression” is common practice in China, he says. Should there be self-censorship in China research, this would further aggravate the situation.

The debate is being conducted in a decidedly emotional manner, partly because there is a latent accusation that too much vested interest within China research is clouding a clear view of the risks. “The current China debate in Germany is too strongly shaped by people with agendas,” according to Der Spiegel. Economic sinologist Doris Fischer of the University of Wuerzburg just rolled her eyes when she read the interview, she commented on social media.

Alpermann disagrees with the accusation that sinology in Germany has been infiltrated too far, especially since it is not substantiated. Those who, like Hennig and Fulda, call for China expertise oriented toward democratic values are insinuating that all sinologists who work at universities or in the public sector are violating their oath of office to the free democratic basic order. “That is simply slander,” Alpermann says.

But despite all the controversy, proponents and opponents of a central registry agree that in science, all autocracies must generally be handled more cautiously in the future. Alpermann sees the risks, particularly in scientific and technical disciplines, whose findings could flow into control or surveillance tools, for example. Hennig and Fulda, on the other hand, also point to the risks in the humanities and social science fields, whose findings could involuntarily provide ideological support for the Chinese regime.

The dilemma is to find a middle ground that considers both sides’ arguments. “We have not yet addressed the specific parameters of such a registry. These would have to be collectively debated and negotiated. So any excitement about this is premature,” according to Hennig.

But in any case, it should by no means be just about China research. It does help to gain a better understanding of the People’s Republic and to generate political measures on this basis. But all research collaborations in all disciplines are affected by the problem. This is because there is very rarely sufficient China expertise available. Yet it is precisely this expertise that is needed to assess the risks involved in collaborations with the Chinese side and to develop guidelines for overcoming these risks.

Following the launch of a Chinese surveillance balloon suspected of being used for espionage purposes over US territory, US President Joe Biden issued a stark warning to the leadership in Beijing. “If China threatens our sovereignty, we will act to protect our country. And we did,” Biden said during his official State of the Union address in Washington Tuesday night.

He called on Republicans and Democrats to be more united in his speech to both chambers of the US Congress. “Let’s be clear: Winning the competition should unite all of us.” But he said he was determined to work with China where US interests could be advanced for the good of the world. He said he has made it clear to Chinese President Xi Jinping in the past that the US seeks competition, not conflict.

China’s leadership nevertheless reacted angrily. “It is not the practice of a responsible country to slander a country or restrict the country’s legitimate development rights under the pretext of competition,” said Mao Ning, spokeswoman for the Foreign Ministry in Beijing. China is not afraid of competition with the US, she said, but is “opposed to the whole relationship between China and the US being defined in terms of competition.” flee

According to the Pentagon, it had sought talks with Beijing immediately after the alleged Chinese spy balloon was shot down. However, the Chinese leadership rejected the offer. This was confirmed by the spokesman of the US Department of Defense, Pat Ryder, on Tuesday.

He said the Pentagon regrets the rejection. “We believe that maintaining open lines of communication between the United States and the People’s Republic of China is important to managing the relationship responsibly,” Ryder continued. At moments like this, he said, communication between the two countries’ militaries is especially important.

As reported by the Washington Post, the balloon is part of an extensive surveillance program. Such balloons have for years collected information on military installations in countries and areas of strategic interest to China, the newspaper reported, citing US intelligence circles. These included Japan, India, Vietnam, Taiwan and the Philippines, for example. The balloons would operate in part from the coast of the southern Chinese island of Hainan. They have been spotted over five continents so far, he said.

“What the Chinese have done is taken an unbelievably old technology, and basically married it with modern communications and observation capabilities to try to glean intelligence on other nations’ militaries,” the Washington Post quotes an unnamed US government official as saying.

The US State Department has sent detailed information about the surveillance balloons to each US embassy to share with allies and partners, according to the newspaper. “There has been great interest in this on the part of our allies and partners,” the government official said. flee

Despite all political warnings of excessive dependence, German trade with China rose to a record level last year. Goods worth around €298 billion were traded between the two countries. This is an increase of around 21 percent compared to 2021, according to current data from the Federal Statistical Office. The statistics authority thus confirms data from Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI), which was already available last week.

The People’s Republic thus remained Germany’s most important trading partner for the seventh year in succession, followed by the USA (around €248 billion) and the Netherlands (just under €234 billion). “Trade flows don’t change overnight,” commented Max Zenglein, chief economist at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics). “The country will remain our most important trading partner for quite some time.”

In 2022, goods worth €191 billion were imported from the People’s Republic, a good third more than in 2021. Germany mainly buys electronics and electrical engineering in China, but also textiles/clothing, machinery and chemical products. Exports of goods “Made in Germany” to China, on the other hand, increased by only 3.1 percent to around €107 billion. Germany’s trade balance with the People’s Republic thus shows a deficit of around €84 billion.

“China is important as an export market but far less important than it appears in the public perception. The United States is much more important for German exporters,” Zenglein said. “Exports to China are exhausted; no more big jumps are to be expected. We have reached a plateau here.”

Politicians and scientists are nevertheless alarmed in view of the strong interdependence in some areas. “The main problem is Germany’s dependence on China for critical raw materials, which are needed for the transition to cleaner energy and transport,” Lukas Menkhoff, head of the global economy department at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), told Reuters. Germany imports about two-thirds of so-called rare earth metals from China. The metals are indispensable in batteries, semiconductors, and magnets in electric cars. rtr

Car sales have fallen significantly despite the holidays surrounding the Chinese New Year. According to the industry association PCA, 1.29 million vehicles were sold in January, about 38 percent fewer than in the same month last year. PCA announced the figures on Wednesday.

More environmentally friendly cars, in particular, sold poorly. Sales of EVs and plug-in hybrids fell by more than 48 percent compared with December. The association explained this, among other things, with the discontinuation of subsidies for some EVs. Many customers had, therefore, already brought forward their purchases to the final quarter of 2022.

In addition, people in China were able to travel freely for the Chinese New Year for the first time since 2020 after Covid restrictions were lifted on Dec. 7. Many production lines were stopped for longer than usual. flee

Marc Matten’s interest in China began with a visit to a flea market in the 1990s. While still in school, he stumbled across a book by Edgar Snow, the US journalist who recorded his encounter with Mao Zedong in the world-famous bestseller “Red Star Over China”. Matten was fascinated. “A little later, when our city library was sorting out old holdings, I took everything that had to do with China.”

After graduating from high school, Matten studied sinology, Japanese studies and economics in Bonn, traveling to Changchun and Tokyo. In the beginning, he says, mainly “mundane reasons” brought him to China. “I was lured by the economic growth and the prospect of a corporate career.”

In Changchun, he hoped to land an internship at VW, but then his interest changed radically and he began to study modern Chinese history. He wrote his master’s thesis on the nationalism of Chinese students in Japan, and in 2009 he received his doctorate with a dissertation on the limits of Chinese in the foundation of a national identity in China at the beginning of the 20th century.

To this day, Matten’s research is guided by how ideas of different origins shape debates in and about China. How are nationalism, emancipation, freedom, and in general, the world as a concept of order discussed in China? What influence did modernization currents in the 20th century have on this? “Eurocentrism has long defined the so-called West as the norm, whether in terms of democracy, human rights or social structures. To me, this view is too simplistic.”

Even at the end of the Qing dynasty, he said, it was evident that Western ideas were not simply adopted. “Instead, narratives from the past were often reactivated, for example, to establish the nation as a political order or to proclaim the renaissance of Confucianism.”

Since earning his doctorate, Matten has been teaching the contemporary history of China at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. He regrets that there is still too little knowledge about China in Germany and Europe: “In my seminars, I talk about the asymmetry of not knowing – historians in Germany know less about Chinese history than vice versa, and the same is true for the disciplines of philosophy, religious studies, political science.” We need to read and hear significantly more about China, he stresses, “especially from Chinese voices”. But there’s a catch to all this: the language barrier. “There’s a lack of translations, and we sinologists should get on that, too.”

Whether Matten himself will get around to translating anytime soon is uncertain. In addition to his teaching, he works on a project on how to write global history from a non-Western perspective. “Party historians in China like to argue that there is such a thing as global history with Chinese characteristics, but what form it should take is unclear.” This debate will keep us busy in the coming years, Matten is sure. Svenja Napp

Klaus Buechele has been the new Senior Manager for Quality Assurance for Audi at FAW-Volkswagen in Changchun since the beginning of the month. Buechele was previously Head of Mobility Service at Audi AG in Neckarsulm.

Zhang Yuzhuo is the new party secretary of the State Council’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, replacing Hao Peng. Zhang had only taken over as head of the China Association for Science and Technology (CAST) in August 2021. Prior to that, he was chairman of Sinopec, China’s largest natural gas and oil company, for just under a year and a half.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Hot pot in a tube: At this restaurant in Chongqing, diners can simmer their outdoor hot pot in converted and illuminated cement tubes.