What do journalists, students, and the UN Human Rights Commissioner have in common? They frequently hand in their required work only at the last minute. Michelle Bachelet made it particularly exciting. The outgoing UN Commissioner for Human Rights wanted to submit the report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang by August 31. At 11:52 p.m. on Wednesday night, the report went online eight minutes before the deadline.

Marcel Grzanna has taken a look at the paper. For the first time, the United Nations speak of “grave human rights violations” in the report. The Bachelet report lists what China did in Xinjiang: Set up camps and forced their inmates to work in factories, suppressed the Uighur birth rate with forced sterilizations, set up total surveillance, pushed back Islam, and destroyed mosques.

The Chilean politician thus surpassed the low expectations that civil rights groups had placed on her. Bachelet is considered China-friendly. Many observers had expected a smoothed report. Indeed she does not follow the reading of “cultural genocide,” but she names numerous crimes. She does so against the explicit protest from Beijing.

Now, a difficult task awaits Bachelet’s successor. Several names are currently circulating for the position. However, a rewarding task does not await the candidates. The pressure from Beijing on the office will not diminish in the coming years.

Increasing control is also playing havoc with the Hong Kong film industry. At times, it was one of the largest and most diverse in the world. But the National Security Act has now produced a censorship law as subsequent legislation, which destroyed the creative and rebellious film scene in Hong Kong, as Felix Lee writes. “Hong Kong films are now exclusively for China,” says US film expert Chris Berry. Many creatives moved from their native Hong Kong to Europe.

In our Heads column, we look back at the life of Mikhail Gorbachev. The Nobel Peace Prize winner died at the age of 91. The former President of the Soviet Union is viewed with contempt in Beijing, as Fabian Kretschmer writes. This is because Gorbachev is seen as a traitor to the communist idea who abandoned the giant empire of the Soviet Union to disintegration.

In the final minutes of her term, Michelle Bachelet delivered after all. On her last day of work, shortly before midnight on Wednesday, she published a report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang as the first High Commissioner for Human Rights in the history of the United Nations. Bachelet had not indicated whether the paper would actually still be published under her responsibility and against the will of the Chinese government.

It states that the actions of the Chinese government in Xinjiang “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.” The wording does not say whether such crimes are actually occurring. But the mere reference to it sends a strong signal from the High Commissioner, notably since it refers to “credible” allegations of torture.

So far, Bachelet has been true to her diplomatic style. She has repeatedly been accused of being too soft in her dealings with the leadership in Beijing. The report avoids the term “genocide,” which has been used by the US government and several parliaments of democratic countries, among others. But it very specifically addresses allegations of forced labor, forced sterilizations, and torture.

The UN questions whether the so-called graduates of the re-education program, which was declared an educational program, are in the camps voluntarily. However, determining how many people are affected by the lack of concrete data, is difficult. Estimates by Xinjiang researchers put the number of people who could be housed in the camps at around one million. The word “forced labor” is also used.

In addition, there is credible evidence “of violations of reproductive rights through the coercive enforcement of family planning policies since 2017,” the report says. It stated that women of Uyghur, as well as Kazakh origin, have had contraceptive coils inserted or were forcibly sterilized against their will. The measures are one reason for a significant drop in the birth rate in Xinjiang.

Elsewhere, the report describes how the regime subdues people. Tactics include starvation and injections of drugs, the High Commission notes. “Almost all interviewees described either injections, pills, or both” and “regular blood draws.” It adds, “Respondents were consistent in their descriptions of how the drugs administered made them sleepy.”

The report ties with the report by Special Rapporteur Tomoya Obokata, who deplored “forms of slavery” in Xinjiang a few weeks ago (China.Table reported). He also brings up the ongoing destruction of religious sites. Satellite images would show the destruction of mosques or their striking external changes.

“I had hoped, but not expected, that this report would articulate crimes against humanity or even the facts of genocide. It is an important paper, the first time the United Nations has officially acknowledged the existence of evidence of human rights crimes in Xinjiang,” said Zumretay Erkin, who is responsible for advocacy at the United Nations for the World Uyghur Congress (WUC).

Beijing could respond to the report in an annex. In 131 pages – nearly three times the length of the UN report itself – the Chinese government states that “the so-called assessment distorts China’s laws, wantonly smears and slanders China“. It says the report constitutes “interference in China’s internal affairs.” “This violates international principles of dialogue and cooperation,” Beijing stresses in its response.

For more than a year, the publication of the report had been repeatedly postponed. Bachelet had justified the latest delay by explaining that she wanted to integrate the impressions of her Xinjiang visit at the end of May into the document. However, the trip to Xinjiang was not an official investigation and was severely limited in scope. Beijing had justified this with strict Covid requirements. China was also granted the right to view and comment on the report in advance, a practice Bachelet said all member states are entitled to when they are the subject of a report by the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Opinions are divided on the report and Bachelet’s role, with numerous democratic states and nongovernmental organizations calling for its release. In opposition, dozens of countries in tow of the Chinese government had formed to treat torture, arbitrary arrests, and rape as China’s internal affair.

Bachelet has defended herself against accusations that she allowed herself to be appropriated by the Chinese government. In May, she had adopted the language of Chinese propaganda and, in the eyes of critics, thus downplayed the situation in Xinjiang. She spoke of training centers and measures against terrorism. She said she had not wanted to confront China, but to find a way to get Beijing to cooperate. It is still up to member states to respect and promote human rights in their own countries, she told Deutsche Welle recently.

“That this expression does not reflect the reality and the terrible human rights violations in internment camps must have been clear to Ms. Bachelet. The direct naming and condemnation of human rights violations committed must not fall victim to this,” demanded Renata Alt, Chairwoman of the Human Rights Committee in the German Bundestag.

Alt condemns “in the strongest possible terms” the fact that China exerted tremendous pressure before the publication, as Bachelet said the previous week. However, she was hardly surprised. That is why the FDP politician considers the report’s publication to be essential, “also for the credibility of the UN.”

Michael Polak agrees. He is a British-Australian lawyer who, on behalf of Uyghur lobby groups, filed a lawsuit a few days ago against responsible officials from Xinjiang for genocide in an Argentine court (China.Table reported). “In China, there is no legal system where victims can seek justice. That is why Ms. Bachelet’s positioning is so important. She is the last instance to which victims can turn,” says Polak.

Bachelet’s report symbolizes how, in the office’s nearly 30-year history, the role of the UN watchdog over human rights is now being tugged at. The systemic competition between democratic and autocratic states has long since reached the human rights arena. The People’s Republic wants to impose its definition of human rights on the world. A definition in which civil liberties are to be replaced in horse-trading by a right to economic development.

Bachelet’s successor is likely to be watched with corresponding attention internationally. After the Chilean unexpectedly declared her renunciation of a further term in office two weeks after her trip to China, the UN had little time to organize the successor. Several names are circulating, including that of Austrian Volker Türk.

Türk had only been appointed by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres as Undersecretary on his staff of advisors in January. Türk previously worked for 30 years at the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). For former UN staffer and whistleblower Emma Reilly, Türk would not be a good choice. “Much like Bachelet, he would not be particularly outspoken on human rights,” Reilly believes. The lawyer accuses Bachelet and Secretary-General Guterres of leaking the names of Uyghur dissidents to the Chinese government.

Latvian Ilze Brands Kehris and Croatian Ivan Šimonović are also said to be in the running to succeed her. Brands Kehris has been Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights in New York since 2020. Between 2017 and 2019, she was an independent expert member of the UN Human Rights Council. Šimonović, on the other hand, is Croatia’s acting representative to the United Nations. Rumors are circulating, however, that Russia might veto a Human Rights High Commissioner from an Eastern European state and therefore nominate a candidate from Africa or Asia.

Kenneth Roth recently provided the job description in an interview with AFP. Roth had been director of Human Rights Watch since 1993 and, like Bachelet, resigned Wednesday. “This is not a job for a nice, quiet diplomat, because a quiet diplomat has no leverage. Nobody listens to a quiet diplomat. Nobody changes their behavior because of a quiet diplomat,” Roth said.

Not long ago, films from Hong Kong enjoyed a legendary reputation. Alongside atmospherically dense productions and martial arts strips, political themes were included. In contrast to the mainland, the focus was on freedom, civil rights, and alternative lifestyles. One example is the film “Lost in Fumes” by filmmaker Nora Lam, in which she portrays the politician Edward Leung, who is in prison for his participation in democracy protests. Her work won a prize at the documentary film festival in Taiwan.

For the past year, however, the vital film scene that produced such works has been dead. Productions dealing with democracy protests and police violence will no longer come from Hong Kong in the foreseeable future. And neither will other films that displease the authorities. Since August 2021, a law that no longer allows films critical of the government has been in effect in the former film metropolis. The censorship law bans all content that the authorities interpret as calls “for secession, subversion, terrorism or collusion with foreign forces.” The law applies to new releases as well as older films. “Any film for public exhibition, past, present, and future will need to get approval,” Hong Kong’s Commerce Secretary Edward Yau confirmed when the law was declared a year ago.

The law has the feared devastating effect: “Independent films in Hong Kong are effectively dead,” says Chris Berry, a film scholar at the University of London who specializes in cinema from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The censorship law is part of the comprehensive National Security Law passed by the Chinese leadership in Beijing in July 2020, which has since criminalized just about everything in Hong Kong that criticizes Hong Kong’s government and the People’s Republic.

The consternation was all the greater because Hong Kong filmmakers stepped up their game shortly beforehand. The drama “No. 1 Chung Ying Street,” for example, won the top honor at the Osaka Asian Film Festival in Japan. In it, the respected Hong Kong director Derek Chiu compares the 1967 protests against the colonial power Great Britain with the 2014 and 2015 protests against China. This film is also no longer allowed in Hong Kong.

With the Security Law, the leadership in Beijing put an abrupt end to the democracy movement in Hong Kong because it allows the authorities to take harsh action against all activities that threaten the security of the People’s Republic in the opinion of the Chinese leadership. Particularly between 2014 and 2019, there were partially massive protests against Beijing’s influence and the erosion of Hong Kong’s autonomous status. Since its introduction, the new law has also affected research, education, and the media. It was only a matter of time before the law was extended to the arts – and thus also to Hong Kong cinema.

This comes as a shock to the once thriving cinema scene in the Chinese special administrative region. At some point, Hong Kong’s film industry was one of the largest and most diverse in the world. And it looks back on a lively tradition. After the Second World War, numerous Chinese filmmakers who had previously worked in Shanghai – until then “Hollywood of Asia” – came to Hong Kong. On the Chinese mainland, the communists were victorious, and actors and filmmakers were branded bourgeois and fled to Hong Kong. The flight of capital by wealthy investors also ensured the development of a film industry in the British crown colony.

Over the next few decades, the Hong Kong film industry initially catered to the clientele in Chinatowns in Southeast Asia and North America. Stars like Bruce Lee and his kung fu films quickly became popular in other circles as well. And Hong Kong film producers were busy. By the mid-1960s, they were producing more films than Germany and France combined. And while many national film industries fell into crisis in the 1970s, overrun by Hollywood blockbusters, the Hong Kong film studios continued to shoot diligently.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Hong Kong filmmakers also ventured into complicated genres: director John Woo, for example, became known worldwide with socially critical gangster films. Beginning in the 1990s, directors like Wong Kar-Wai also touched on subjects that were taboo in much of Asia: Homosexuality, mental illness, and family violence. Then came the preoccupation with democracy efforts. Inside the Hong Kong film industry, a separate indie scene emerged with filmmakers who made a name for themselves internationally.

At the same time, at least commercially, the film industry in the People’s Republic caught up rapidly in the course of the opening-up policy. Thus, Hong Kong’s film industry lost its importance. In the early 1990s, almost 250 films were completed in Hong Kong each year, but by the turn of the millennium, only a few dozen remained.

In 2003, help came from a law in China, of all places. In order to promote the domestic film industry, China still allows only a limited number of foreign films in Chinese cinemas. To help the Hong Kong film industry out of its crisis, the leadership in Beijing gave a green light for Hong Kong films to be considered domestic productions as well. A huge market opened up for the Hong Kong film industry.

However, anything to be shown in the People’s Republic must get past the censors. Hong Kong’s film industry has adapted to this and delivers adapted goods. Most producers in Hong Kong have therefore decided to forego critical themes. Since then, they have focused on shallow material such as historical dramas that sometimes cater to Chinese nationalism or action thrillers free of politics. “Mainland China is now one of the largest and most valuable cinema markets in the world, probably more valuable than the US,” says film expert Chris Berry. “Hong Kong films today are exclusively films for China.”

Some filmmakers in Hong Kong have maintained their artistic freedom for as long as possible. These included filmmakers such as Nora Lam and Derek Chiu. However, they pay a high price for their sincerity. With the new censorship law, their films will now no longer be shown in Hong Kong either. Until 2020, the indie scene still had a focal point in an annual documentary film festival presented by the independent organization Ying E Chi. Since 2020, that is dead, too. Ying E Chi’s website is blank.

Many critical filmmakers have therefore left Hong Kong in recent months. Around 80 of them have moved to London alone, estimates Kit Hung. The 45-year-old is a screenwriter and independent filmmaker living in London since late 2021. He won the Teddy Award at the Berlinale in 2009 with his semi-autobiographical film “Soundless Wind Chime,” among others. Nowadays, he teaches at the Film School of Westminster University in London. He still counts himself among those less affected. “Many have come to London and don’t know what to do,” he says, describing the situation of his colleagues. “All they know is that they can’t go back to Hong Kong.”

According to the digital association Bitkom, more and more cyber-attacks on German companies are coming from Russia and China. “The attackers are becoming increasingly professional and are more often in organized crime, with the demarcation between criminal gangs and state-controlled groups becoming increasingly difficult,” Bitkom President, Achim Berg, said in Berlin on Wednesday. In a survey of over 1,000 companies from all industries conducted by Bitkom, organized groups are now ranked number one. “In particular, attacks from Russia and China increased recently.”

It is estimated that companies have suffered losses of €203 billion. At the beginning of the year, they were asked about their cases in the past twelve months. The damage was still at a record €223 billion in last year’s survey. “This is no reason to sound the all-clear,” Berg said. Especially critical infrastructure operators are increasingly in the spotlight, he said. A few years ago, the annual damage was only half as high.

84 percent of companies said they had been affected by cyber-attacks – espionage, sabotage, or theft. From 61 percent of businesses, sensitive data had been stolen. “You can protect yourself, of course,” Berg said. But companies need to invest in protection measures. Large corporations are much more advanced in this respect than small and medium-sized businesses. Under no circumstances should ransoms be paid. Even then, stolen data is usually not returned completely. rtr/nib

Since US top leader Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, China’s People’s Liberation Army has held multiple military maneuvers in waters dangerously close to the island, including launching missiles. Now Taiwan’s army is returning the threads.

If Chinese aircraft and ships were to enter the twelve-mile zone off Taiwan’s coast, Taiwan had a “right to self-defense” and would move to “counter-attack,” said Lieutenant General Lin Wen-huang. They will continue to “do whatever it takes to protect our homes, our families, and our sovereignty,” a Taiwan Defense Ministry spokesman stressed. China’s recent military exercises violated the status quo in the Taiwan Strait, he said.

The lieutenant general specified that to repel the Chinese troops, Taiwan would use its naval and air forces as well as fire from the coast. The closer the invading aircraft and ships get to Taiwan, “the stronger our countermeasures will be.”

On Tuesday, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen had said at an air base that she had ordered the military to take necessary and strong countermeasures against China’s provocations. According to the armed forces, on Tuesday, Taiwanese soldiers fired warning shots at a Chinese military drone spotted over Kinmen Island, which belongs to Taiwan. rtr/flee

Russian gas giant Gazprom wants to press ahead with plans to build a second pipeline to China. Project preparations for the construction of the “Siberian Force 2” pipeline, which has been planned for years, are to start soon, Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller told the Interfax news agency. The second pipe to China would greatly increase the possibilities of Russian gas exports to the People’s Republic (China.Table reported).

The new pipeline could allow gas from the western fields of Siberia, traditionally destined for the European market, to flow to China for the first time. Gazprom also wants to expand the pipeline network within Russia. According to the Financial Times, “Siberian Force 2” will break ground in 2024. The Moscow Times reports that the pipeline is expected to be commissioned in 2030. nib

Following the agreement between the US and China on issues of supervision of listed companies (China.Table reported), the US authorities are now actually targeting Chinese companies. The news agency Reuters has learned that the regulators have already selected the retail groups Alibaba and JD.com as well as the gastro chain Yum China for an audit.

Alibaba and JD are two of China’s leading tech companies. Yum China owns the brands Kentucky Fried Chicken, Taco Bell, and Pizza Hut in China. According to the information, they are among the “first group” of Chinese companies to have their financials inspected in Hong Kong by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). The PCAOB is the auditor oversight body of the US. rtr/fin

Guangzhou is another metropolis that has expanded its Covid restrictions. The city of nearly 19 million near Hong Kong reported only five locally transmitted infections on Wednesday. Still, authorities ordered restaurants in certain areas to close until Saturday and canceled indoor events. Kindergartens and elementary, middle, and high schools must also remain closed, while fall semesters at universities are postponed. In addition, Bus and subway services are reduced.

The neighboring metropolis of Shenzhen has ordered the closure of entertainment and cultural establishments in at least four city districts with a total population of around nine million. Restaurants will also be unable to open for a few days, or only to a limited extent.

The province of Guangdong around the metropolises of Guangzhou and Shenzhen on the Pearl River Delta is China’s strongest export province. The combined economic output of Shenzhen and Guangzhou reached about €850 billion last year, which is about half of South Korea’s gross domestic product.

According to the financial firm Capital Economics, 41 cities are currently in the middle of Covid outbreaks. These cities represent 32 percent of China’s economic output. “For now, the resulting disruption appears modest, but the thread of damaging lockdowns is growing,” said economist Julian Evans-Pritchard of Capital Economics. “And even if they are avoided, we expect growth to remain subdued going forward.”

According to the Kiel Institute for Economic Research (IfW), even municipal lockdowns are already exacerbating bottlenecks in global supply chains. However, it said that the current measures in Shenzhen and other cities are not yet comparable to the drastic lockdown in Shanghai last spring. “But if Covid 19 cases continue to rise, a hard lockdown, especially in and around Shenzhen, could put a strain on supply chains and the Christmas shopping season,” warned IfW trade expert Vincent Stamer. “Many consumer goods for the German market are also produced there.” rtr/flee

In China, sympathy for Mikhail Gorbachev’s death is extremely reserved. Even more: The death of the 93-year-old is commented on with a good portion of malice and malicious joy. Commentator Wuwei Li writes to his almost 900,000 followers on Weibo that Gorbachev only deserves “contempt”: “He was a lame, incompetent, cowardly politician” who serves as a “deterrent example” for China. One could only “thank” him for this lesson. Wuwei’s cynical message to the former Soviet president is: “Have a nice trip!”

Hu Xijin, one of the country’s leading political publicists, describes Gorbachev on his Twitter account as “one of the most controversial leaders in the world”: He has gained great recognition in the West by “selling the interests of his homeland”. He is also responsible for the fact that “wars continue to break out” in the territory of the former Soviet Union – including Chechnya, Georgia, and Ukraine.

From “historical sinner” to “traitor” to “Communist Party killer,” the Chinese web is filled with negative superlatives about the former Soviet leader. But the fact is: hardly any other state apparatus has studied the Gorbachev case as carefully as the party cadres of the People’s Republic.

Head of state Xi Jinping in particular was downright traumatized by the demise of the Soviet Union. In early 2013, just shortly after taking office, the now 69-year-old gave in a secret speech about blaming “historical nihilism” and “ideological confusion” for the fall of the Soviet Union, as has since become known. The CPSU, he said, failed to honor its leaders Lenin and Stalin. Gorbachev, who brought Western democratic reforms to the country, was to blame.

At the time, Xi vowed not to repeat those “mistakes” – and in his first years as head of state, he tightened the ideological reins more than at any time since the rule of state founder Mao Zedong. He also condemned his party cadres to study the fall of the Soviet Union very carefully – as a deterrent example.

On the contrary, for China’s once vibrant civil society, Gorbachev was a real beacon of hope. When the Russians traveled to Beijing in May 1989, the students there were demonstrating on Tiananmen Square against corruption and for more political participation. At the time, the state guest said in a remarkable speech: “Economic reforms will not work unless they are supported by a radical transformation of the political system”.

However, China’s government under economic reformer Deng Xiaoping decided to take a different path: The protest movement was brutally crushed with tanks and soldiers. The official reaction of the Beijing Foreign Ministry on Wednesday was correspondingly short. Gorbachev had made a “positive contribution to the normalization of relations between China and the Soviet Union,” said spokesman Zhao Lijian soberly: “We express our condolences to his family on his death due to illness.” Fabian Kretschmer

Jorge Toledo Albiñana, the new EU Ambassador to China, takes office today, Thursday. He takes over from Nicolas Chapuis. The post of the Chinese ambassador, in turn, to the EU remains vacant. The position has been vacant since December. A replacement is not expected until after the party congress in October.

Li Fanrong is the new Chairman of the Board of Sinochem Holdings. Its subsidiary ChemChina includes tire manufacturers such as Pirelli, Aeolus, and Prometeon Tyre Group. Li succeeds Ning Gaoning.

Hong Hao becomes Head and Chief Researcher of Grow Investment Group’s Hong Kong office. He previously worked for Bocom, a subsidiary of China’s Bank of Communications, but was forced to resign as an analyst there due to speculative reports.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not send a note for our staff section to heads@table.media!

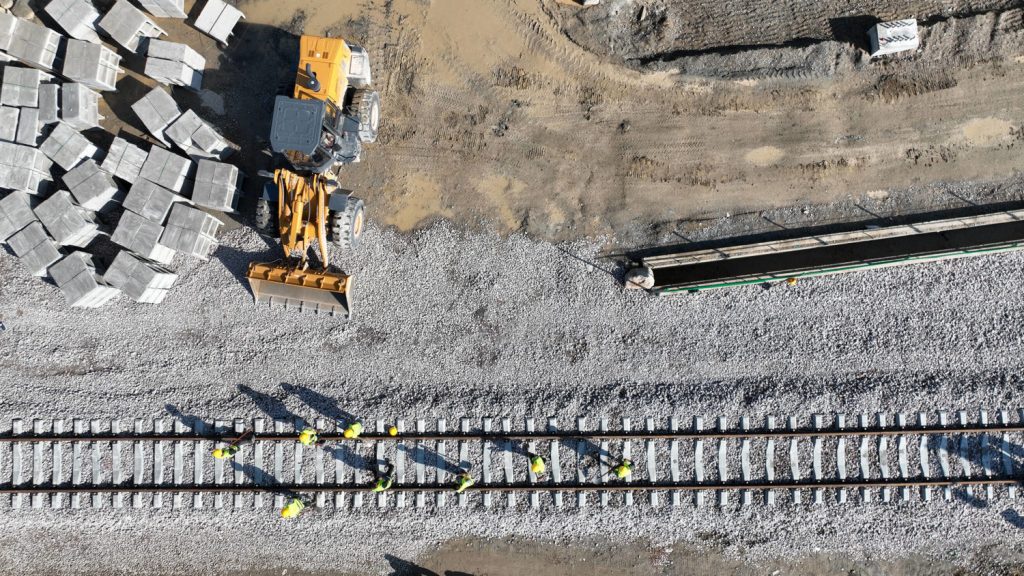

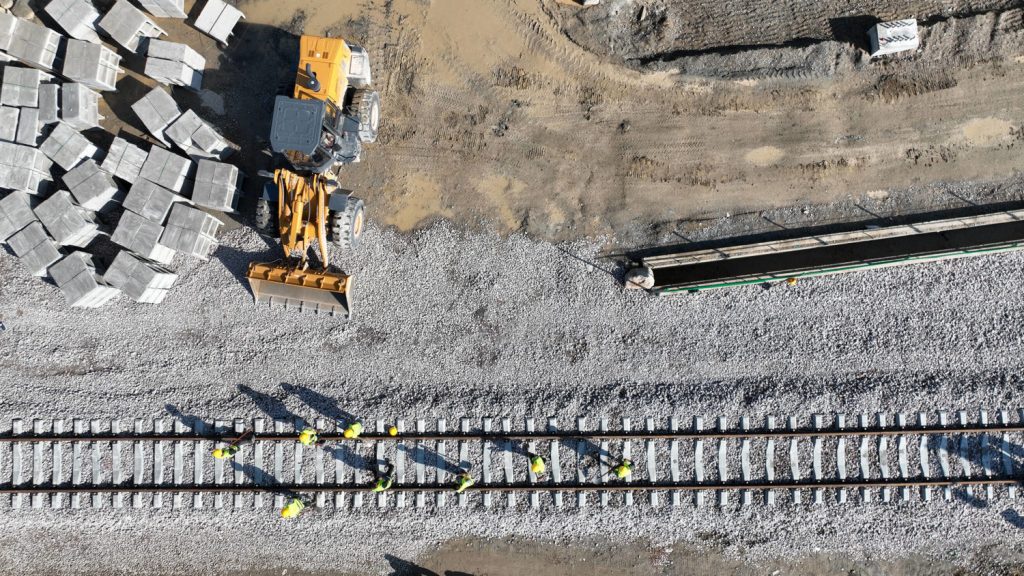

In the final meters: This week, workers placed the last missing rails for the Fuzhou-Xiamen line near Xiamen. The new line in Fujian province is intended to shorten commuting times between the two cities.

What do journalists, students, and the UN Human Rights Commissioner have in common? They frequently hand in their required work only at the last minute. Michelle Bachelet made it particularly exciting. The outgoing UN Commissioner for Human Rights wanted to submit the report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang by August 31. At 11:52 p.m. on Wednesday night, the report went online eight minutes before the deadline.

Marcel Grzanna has taken a look at the paper. For the first time, the United Nations speak of “grave human rights violations” in the report. The Bachelet report lists what China did in Xinjiang: Set up camps and forced their inmates to work in factories, suppressed the Uighur birth rate with forced sterilizations, set up total surveillance, pushed back Islam, and destroyed mosques.

The Chilean politician thus surpassed the low expectations that civil rights groups had placed on her. Bachelet is considered China-friendly. Many observers had expected a smoothed report. Indeed she does not follow the reading of “cultural genocide,” but she names numerous crimes. She does so against the explicit protest from Beijing.

Now, a difficult task awaits Bachelet’s successor. Several names are currently circulating for the position. However, a rewarding task does not await the candidates. The pressure from Beijing on the office will not diminish in the coming years.

Increasing control is also playing havoc with the Hong Kong film industry. At times, it was one of the largest and most diverse in the world. But the National Security Act has now produced a censorship law as subsequent legislation, which destroyed the creative and rebellious film scene in Hong Kong, as Felix Lee writes. “Hong Kong films are now exclusively for China,” says US film expert Chris Berry. Many creatives moved from their native Hong Kong to Europe.

In our Heads column, we look back at the life of Mikhail Gorbachev. The Nobel Peace Prize winner died at the age of 91. The former President of the Soviet Union is viewed with contempt in Beijing, as Fabian Kretschmer writes. This is because Gorbachev is seen as a traitor to the communist idea who abandoned the giant empire of the Soviet Union to disintegration.

In the final minutes of her term, Michelle Bachelet delivered after all. On her last day of work, shortly before midnight on Wednesday, she published a report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang as the first High Commissioner for Human Rights in the history of the United Nations. Bachelet had not indicated whether the paper would actually still be published under her responsibility and against the will of the Chinese government.

It states that the actions of the Chinese government in Xinjiang “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.” The wording does not say whether such crimes are actually occurring. But the mere reference to it sends a strong signal from the High Commissioner, notably since it refers to “credible” allegations of torture.

So far, Bachelet has been true to her diplomatic style. She has repeatedly been accused of being too soft in her dealings with the leadership in Beijing. The report avoids the term “genocide,” which has been used by the US government and several parliaments of democratic countries, among others. But it very specifically addresses allegations of forced labor, forced sterilizations, and torture.

The UN questions whether the so-called graduates of the re-education program, which was declared an educational program, are in the camps voluntarily. However, determining how many people are affected by the lack of concrete data, is difficult. Estimates by Xinjiang researchers put the number of people who could be housed in the camps at around one million. The word “forced labor” is also used.

In addition, there is credible evidence “of violations of reproductive rights through the coercive enforcement of family planning policies since 2017,” the report says. It stated that women of Uyghur, as well as Kazakh origin, have had contraceptive coils inserted or were forcibly sterilized against their will. The measures are one reason for a significant drop in the birth rate in Xinjiang.

Elsewhere, the report describes how the regime subdues people. Tactics include starvation and injections of drugs, the High Commission notes. “Almost all interviewees described either injections, pills, or both” and “regular blood draws.” It adds, “Respondents were consistent in their descriptions of how the drugs administered made them sleepy.”

The report ties with the report by Special Rapporteur Tomoya Obokata, who deplored “forms of slavery” in Xinjiang a few weeks ago (China.Table reported). He also brings up the ongoing destruction of religious sites. Satellite images would show the destruction of mosques or their striking external changes.

“I had hoped, but not expected, that this report would articulate crimes against humanity or even the facts of genocide. It is an important paper, the first time the United Nations has officially acknowledged the existence of evidence of human rights crimes in Xinjiang,” said Zumretay Erkin, who is responsible for advocacy at the United Nations for the World Uyghur Congress (WUC).

Beijing could respond to the report in an annex. In 131 pages – nearly three times the length of the UN report itself – the Chinese government states that “the so-called assessment distorts China’s laws, wantonly smears and slanders China“. It says the report constitutes “interference in China’s internal affairs.” “This violates international principles of dialogue and cooperation,” Beijing stresses in its response.

For more than a year, the publication of the report had been repeatedly postponed. Bachelet had justified the latest delay by explaining that she wanted to integrate the impressions of her Xinjiang visit at the end of May into the document. However, the trip to Xinjiang was not an official investigation and was severely limited in scope. Beijing had justified this with strict Covid requirements. China was also granted the right to view and comment on the report in advance, a practice Bachelet said all member states are entitled to when they are the subject of a report by the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Opinions are divided on the report and Bachelet’s role, with numerous democratic states and nongovernmental organizations calling for its release. In opposition, dozens of countries in tow of the Chinese government had formed to treat torture, arbitrary arrests, and rape as China’s internal affair.

Bachelet has defended herself against accusations that she allowed herself to be appropriated by the Chinese government. In May, she had adopted the language of Chinese propaganda and, in the eyes of critics, thus downplayed the situation in Xinjiang. She spoke of training centers and measures against terrorism. She said she had not wanted to confront China, but to find a way to get Beijing to cooperate. It is still up to member states to respect and promote human rights in their own countries, she told Deutsche Welle recently.

“That this expression does not reflect the reality and the terrible human rights violations in internment camps must have been clear to Ms. Bachelet. The direct naming and condemnation of human rights violations committed must not fall victim to this,” demanded Renata Alt, Chairwoman of the Human Rights Committee in the German Bundestag.

Alt condemns “in the strongest possible terms” the fact that China exerted tremendous pressure before the publication, as Bachelet said the previous week. However, she was hardly surprised. That is why the FDP politician considers the report’s publication to be essential, “also for the credibility of the UN.”

Michael Polak agrees. He is a British-Australian lawyer who, on behalf of Uyghur lobby groups, filed a lawsuit a few days ago against responsible officials from Xinjiang for genocide in an Argentine court (China.Table reported). “In China, there is no legal system where victims can seek justice. That is why Ms. Bachelet’s positioning is so important. She is the last instance to which victims can turn,” says Polak.

Bachelet’s report symbolizes how, in the office’s nearly 30-year history, the role of the UN watchdog over human rights is now being tugged at. The systemic competition between democratic and autocratic states has long since reached the human rights arena. The People’s Republic wants to impose its definition of human rights on the world. A definition in which civil liberties are to be replaced in horse-trading by a right to economic development.

Bachelet’s successor is likely to be watched with corresponding attention internationally. After the Chilean unexpectedly declared her renunciation of a further term in office two weeks after her trip to China, the UN had little time to organize the successor. Several names are circulating, including that of Austrian Volker Türk.

Türk had only been appointed by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres as Undersecretary on his staff of advisors in January. Türk previously worked for 30 years at the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). For former UN staffer and whistleblower Emma Reilly, Türk would not be a good choice. “Much like Bachelet, he would not be particularly outspoken on human rights,” Reilly believes. The lawyer accuses Bachelet and Secretary-General Guterres of leaking the names of Uyghur dissidents to the Chinese government.

Latvian Ilze Brands Kehris and Croatian Ivan Šimonović are also said to be in the running to succeed her. Brands Kehris has been Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights in New York since 2020. Between 2017 and 2019, she was an independent expert member of the UN Human Rights Council. Šimonović, on the other hand, is Croatia’s acting representative to the United Nations. Rumors are circulating, however, that Russia might veto a Human Rights High Commissioner from an Eastern European state and therefore nominate a candidate from Africa or Asia.

Kenneth Roth recently provided the job description in an interview with AFP. Roth had been director of Human Rights Watch since 1993 and, like Bachelet, resigned Wednesday. “This is not a job for a nice, quiet diplomat, because a quiet diplomat has no leverage. Nobody listens to a quiet diplomat. Nobody changes their behavior because of a quiet diplomat,” Roth said.

Not long ago, films from Hong Kong enjoyed a legendary reputation. Alongside atmospherically dense productions and martial arts strips, political themes were included. In contrast to the mainland, the focus was on freedom, civil rights, and alternative lifestyles. One example is the film “Lost in Fumes” by filmmaker Nora Lam, in which she portrays the politician Edward Leung, who is in prison for his participation in democracy protests. Her work won a prize at the documentary film festival in Taiwan.

For the past year, however, the vital film scene that produced such works has been dead. Productions dealing with democracy protests and police violence will no longer come from Hong Kong in the foreseeable future. And neither will other films that displease the authorities. Since August 2021, a law that no longer allows films critical of the government has been in effect in the former film metropolis. The censorship law bans all content that the authorities interpret as calls “for secession, subversion, terrorism or collusion with foreign forces.” The law applies to new releases as well as older films. “Any film for public exhibition, past, present, and future will need to get approval,” Hong Kong’s Commerce Secretary Edward Yau confirmed when the law was declared a year ago.

The law has the feared devastating effect: “Independent films in Hong Kong are effectively dead,” says Chris Berry, a film scholar at the University of London who specializes in cinema from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The censorship law is part of the comprehensive National Security Law passed by the Chinese leadership in Beijing in July 2020, which has since criminalized just about everything in Hong Kong that criticizes Hong Kong’s government and the People’s Republic.

The consternation was all the greater because Hong Kong filmmakers stepped up their game shortly beforehand. The drama “No. 1 Chung Ying Street,” for example, won the top honor at the Osaka Asian Film Festival in Japan. In it, the respected Hong Kong director Derek Chiu compares the 1967 protests against the colonial power Great Britain with the 2014 and 2015 protests against China. This film is also no longer allowed in Hong Kong.

With the Security Law, the leadership in Beijing put an abrupt end to the democracy movement in Hong Kong because it allows the authorities to take harsh action against all activities that threaten the security of the People’s Republic in the opinion of the Chinese leadership. Particularly between 2014 and 2019, there were partially massive protests against Beijing’s influence and the erosion of Hong Kong’s autonomous status. Since its introduction, the new law has also affected research, education, and the media. It was only a matter of time before the law was extended to the arts – and thus also to Hong Kong cinema.

This comes as a shock to the once thriving cinema scene in the Chinese special administrative region. At some point, Hong Kong’s film industry was one of the largest and most diverse in the world. And it looks back on a lively tradition. After the Second World War, numerous Chinese filmmakers who had previously worked in Shanghai – until then “Hollywood of Asia” – came to Hong Kong. On the Chinese mainland, the communists were victorious, and actors and filmmakers were branded bourgeois and fled to Hong Kong. The flight of capital by wealthy investors also ensured the development of a film industry in the British crown colony.

Over the next few decades, the Hong Kong film industry initially catered to the clientele in Chinatowns in Southeast Asia and North America. Stars like Bruce Lee and his kung fu films quickly became popular in other circles as well. And Hong Kong film producers were busy. By the mid-1960s, they were producing more films than Germany and France combined. And while many national film industries fell into crisis in the 1970s, overrun by Hollywood blockbusters, the Hong Kong film studios continued to shoot diligently.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Hong Kong filmmakers also ventured into complicated genres: director John Woo, for example, became known worldwide with socially critical gangster films. Beginning in the 1990s, directors like Wong Kar-Wai also touched on subjects that were taboo in much of Asia: Homosexuality, mental illness, and family violence. Then came the preoccupation with democracy efforts. Inside the Hong Kong film industry, a separate indie scene emerged with filmmakers who made a name for themselves internationally.

At the same time, at least commercially, the film industry in the People’s Republic caught up rapidly in the course of the opening-up policy. Thus, Hong Kong’s film industry lost its importance. In the early 1990s, almost 250 films were completed in Hong Kong each year, but by the turn of the millennium, only a few dozen remained.

In 2003, help came from a law in China, of all places. In order to promote the domestic film industry, China still allows only a limited number of foreign films in Chinese cinemas. To help the Hong Kong film industry out of its crisis, the leadership in Beijing gave a green light for Hong Kong films to be considered domestic productions as well. A huge market opened up for the Hong Kong film industry.

However, anything to be shown in the People’s Republic must get past the censors. Hong Kong’s film industry has adapted to this and delivers adapted goods. Most producers in Hong Kong have therefore decided to forego critical themes. Since then, they have focused on shallow material such as historical dramas that sometimes cater to Chinese nationalism or action thrillers free of politics. “Mainland China is now one of the largest and most valuable cinema markets in the world, probably more valuable than the US,” says film expert Chris Berry. “Hong Kong films today are exclusively films for China.”

Some filmmakers in Hong Kong have maintained their artistic freedom for as long as possible. These included filmmakers such as Nora Lam and Derek Chiu. However, they pay a high price for their sincerity. With the new censorship law, their films will now no longer be shown in Hong Kong either. Until 2020, the indie scene still had a focal point in an annual documentary film festival presented by the independent organization Ying E Chi. Since 2020, that is dead, too. Ying E Chi’s website is blank.

Many critical filmmakers have therefore left Hong Kong in recent months. Around 80 of them have moved to London alone, estimates Kit Hung. The 45-year-old is a screenwriter and independent filmmaker living in London since late 2021. He won the Teddy Award at the Berlinale in 2009 with his semi-autobiographical film “Soundless Wind Chime,” among others. Nowadays, he teaches at the Film School of Westminster University in London. He still counts himself among those less affected. “Many have come to London and don’t know what to do,” he says, describing the situation of his colleagues. “All they know is that they can’t go back to Hong Kong.”

According to the digital association Bitkom, more and more cyber-attacks on German companies are coming from Russia and China. “The attackers are becoming increasingly professional and are more often in organized crime, with the demarcation between criminal gangs and state-controlled groups becoming increasingly difficult,” Bitkom President, Achim Berg, said in Berlin on Wednesday. In a survey of over 1,000 companies from all industries conducted by Bitkom, organized groups are now ranked number one. “In particular, attacks from Russia and China increased recently.”

It is estimated that companies have suffered losses of €203 billion. At the beginning of the year, they were asked about their cases in the past twelve months. The damage was still at a record €223 billion in last year’s survey. “This is no reason to sound the all-clear,” Berg said. Especially critical infrastructure operators are increasingly in the spotlight, he said. A few years ago, the annual damage was only half as high.

84 percent of companies said they had been affected by cyber-attacks – espionage, sabotage, or theft. From 61 percent of businesses, sensitive data had been stolen. “You can protect yourself, of course,” Berg said. But companies need to invest in protection measures. Large corporations are much more advanced in this respect than small and medium-sized businesses. Under no circumstances should ransoms be paid. Even then, stolen data is usually not returned completely. rtr/nib

Since US top leader Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, China’s People’s Liberation Army has held multiple military maneuvers in waters dangerously close to the island, including launching missiles. Now Taiwan’s army is returning the threads.

If Chinese aircraft and ships were to enter the twelve-mile zone off Taiwan’s coast, Taiwan had a “right to self-defense” and would move to “counter-attack,” said Lieutenant General Lin Wen-huang. They will continue to “do whatever it takes to protect our homes, our families, and our sovereignty,” a Taiwan Defense Ministry spokesman stressed. China’s recent military exercises violated the status quo in the Taiwan Strait, he said.

The lieutenant general specified that to repel the Chinese troops, Taiwan would use its naval and air forces as well as fire from the coast. The closer the invading aircraft and ships get to Taiwan, “the stronger our countermeasures will be.”

On Tuesday, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen had said at an air base that she had ordered the military to take necessary and strong countermeasures against China’s provocations. According to the armed forces, on Tuesday, Taiwanese soldiers fired warning shots at a Chinese military drone spotted over Kinmen Island, which belongs to Taiwan. rtr/flee

Russian gas giant Gazprom wants to press ahead with plans to build a second pipeline to China. Project preparations for the construction of the “Siberian Force 2” pipeline, which has been planned for years, are to start soon, Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller told the Interfax news agency. The second pipe to China would greatly increase the possibilities of Russian gas exports to the People’s Republic (China.Table reported).

The new pipeline could allow gas from the western fields of Siberia, traditionally destined for the European market, to flow to China for the first time. Gazprom also wants to expand the pipeline network within Russia. According to the Financial Times, “Siberian Force 2” will break ground in 2024. The Moscow Times reports that the pipeline is expected to be commissioned in 2030. nib

Following the agreement between the US and China on issues of supervision of listed companies (China.Table reported), the US authorities are now actually targeting Chinese companies. The news agency Reuters has learned that the regulators have already selected the retail groups Alibaba and JD.com as well as the gastro chain Yum China for an audit.

Alibaba and JD are two of China’s leading tech companies. Yum China owns the brands Kentucky Fried Chicken, Taco Bell, and Pizza Hut in China. According to the information, they are among the “first group” of Chinese companies to have their financials inspected in Hong Kong by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). The PCAOB is the auditor oversight body of the US. rtr/fin

Guangzhou is another metropolis that has expanded its Covid restrictions. The city of nearly 19 million near Hong Kong reported only five locally transmitted infections on Wednesday. Still, authorities ordered restaurants in certain areas to close until Saturday and canceled indoor events. Kindergartens and elementary, middle, and high schools must also remain closed, while fall semesters at universities are postponed. In addition, Bus and subway services are reduced.

The neighboring metropolis of Shenzhen has ordered the closure of entertainment and cultural establishments in at least four city districts with a total population of around nine million. Restaurants will also be unable to open for a few days, or only to a limited extent.

The province of Guangdong around the metropolises of Guangzhou and Shenzhen on the Pearl River Delta is China’s strongest export province. The combined economic output of Shenzhen and Guangzhou reached about €850 billion last year, which is about half of South Korea’s gross domestic product.

According to the financial firm Capital Economics, 41 cities are currently in the middle of Covid outbreaks. These cities represent 32 percent of China’s economic output. “For now, the resulting disruption appears modest, but the thread of damaging lockdowns is growing,” said economist Julian Evans-Pritchard of Capital Economics. “And even if they are avoided, we expect growth to remain subdued going forward.”

According to the Kiel Institute for Economic Research (IfW), even municipal lockdowns are already exacerbating bottlenecks in global supply chains. However, it said that the current measures in Shenzhen and other cities are not yet comparable to the drastic lockdown in Shanghai last spring. “But if Covid 19 cases continue to rise, a hard lockdown, especially in and around Shenzhen, could put a strain on supply chains and the Christmas shopping season,” warned IfW trade expert Vincent Stamer. “Many consumer goods for the German market are also produced there.” rtr/flee

In China, sympathy for Mikhail Gorbachev’s death is extremely reserved. Even more: The death of the 93-year-old is commented on with a good portion of malice and malicious joy. Commentator Wuwei Li writes to his almost 900,000 followers on Weibo that Gorbachev only deserves “contempt”: “He was a lame, incompetent, cowardly politician” who serves as a “deterrent example” for China. One could only “thank” him for this lesson. Wuwei’s cynical message to the former Soviet president is: “Have a nice trip!”

Hu Xijin, one of the country’s leading political publicists, describes Gorbachev on his Twitter account as “one of the most controversial leaders in the world”: He has gained great recognition in the West by “selling the interests of his homeland”. He is also responsible for the fact that “wars continue to break out” in the territory of the former Soviet Union – including Chechnya, Georgia, and Ukraine.

From “historical sinner” to “traitor” to “Communist Party killer,” the Chinese web is filled with negative superlatives about the former Soviet leader. But the fact is: hardly any other state apparatus has studied the Gorbachev case as carefully as the party cadres of the People’s Republic.

Head of state Xi Jinping in particular was downright traumatized by the demise of the Soviet Union. In early 2013, just shortly after taking office, the now 69-year-old gave in a secret speech about blaming “historical nihilism” and “ideological confusion” for the fall of the Soviet Union, as has since become known. The CPSU, he said, failed to honor its leaders Lenin and Stalin. Gorbachev, who brought Western democratic reforms to the country, was to blame.

At the time, Xi vowed not to repeat those “mistakes” – and in his first years as head of state, he tightened the ideological reins more than at any time since the rule of state founder Mao Zedong. He also condemned his party cadres to study the fall of the Soviet Union very carefully – as a deterrent example.

On the contrary, for China’s once vibrant civil society, Gorbachev was a real beacon of hope. When the Russians traveled to Beijing in May 1989, the students there were demonstrating on Tiananmen Square against corruption and for more political participation. At the time, the state guest said in a remarkable speech: “Economic reforms will not work unless they are supported by a radical transformation of the political system”.

However, China’s government under economic reformer Deng Xiaoping decided to take a different path: The protest movement was brutally crushed with tanks and soldiers. The official reaction of the Beijing Foreign Ministry on Wednesday was correspondingly short. Gorbachev had made a “positive contribution to the normalization of relations between China and the Soviet Union,” said spokesman Zhao Lijian soberly: “We express our condolences to his family on his death due to illness.” Fabian Kretschmer

Jorge Toledo Albiñana, the new EU Ambassador to China, takes office today, Thursday. He takes over from Nicolas Chapuis. The post of the Chinese ambassador, in turn, to the EU remains vacant. The position has been vacant since December. A replacement is not expected until after the party congress in October.

Li Fanrong is the new Chairman of the Board of Sinochem Holdings. Its subsidiary ChemChina includes tire manufacturers such as Pirelli, Aeolus, and Prometeon Tyre Group. Li succeeds Ning Gaoning.

Hong Hao becomes Head and Chief Researcher of Grow Investment Group’s Hong Kong office. He previously worked for Bocom, a subsidiary of China’s Bank of Communications, but was forced to resign as an analyst there due to speculative reports.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not send a note for our staff section to heads@table.media!

In the final meters: This week, workers placed the last missing rails for the Fuzhou-Xiamen line near Xiamen. The new line in Fujian province is intended to shorten commuting times between the two cities.