Chinese investors as a horror for the workforce – this distorted image is outdated. Works councils and trade unions experience the same joys and hardships with Chinese owners as with domestic owners, writes Christian Domke Seidel. He extensively asked around among employee representatives of companies under Chinese ownership. One finding is that American investors have much less sympathy for co-determination than those from China.

Parts of German sinology are faced with demands to reappraise their past. Marcel Grzanna writes about this today. Many senior China researchers were granted access to the country in the 1970s because they harbored great sympathies for Maoism. This gave them an information advantage. In today’s climate, however, there is a call for them to clearly distance themselves from the stance of that time.

Whether it is the minority stake of the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) in the Port of Hamburg and Logistics (HHLA) or the investments of Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL) in the German state of Thuringia – politics, the public and competitors are usually very critical of Chinese investors. From a geopolitical or macroeconomic perspective, there may be reasons for this. However, the employees of the affected companies have less to worry about. Trade unions and works councils generally have positive experiences with investors from the People’s Republic.

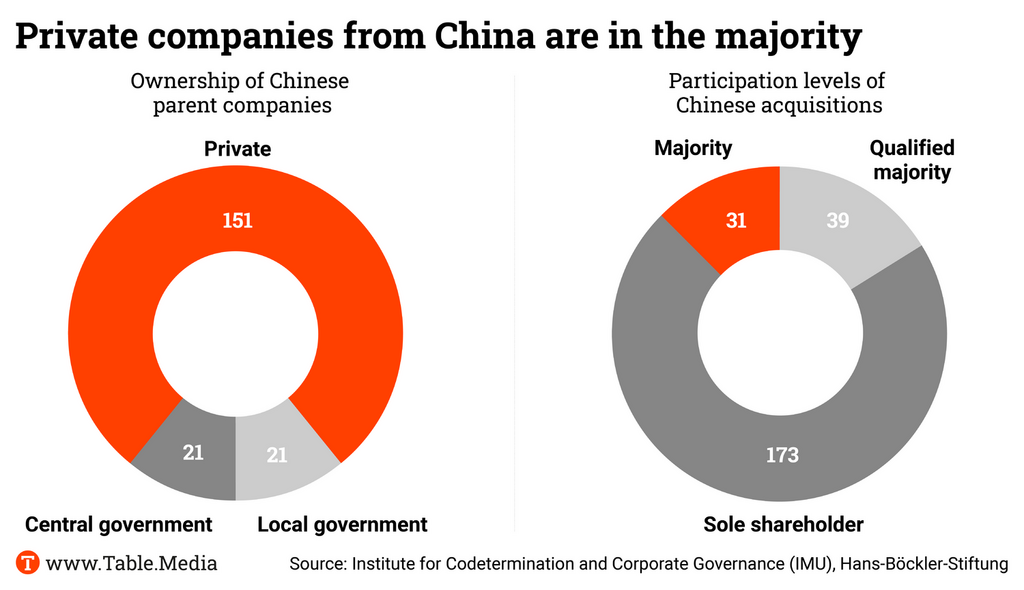

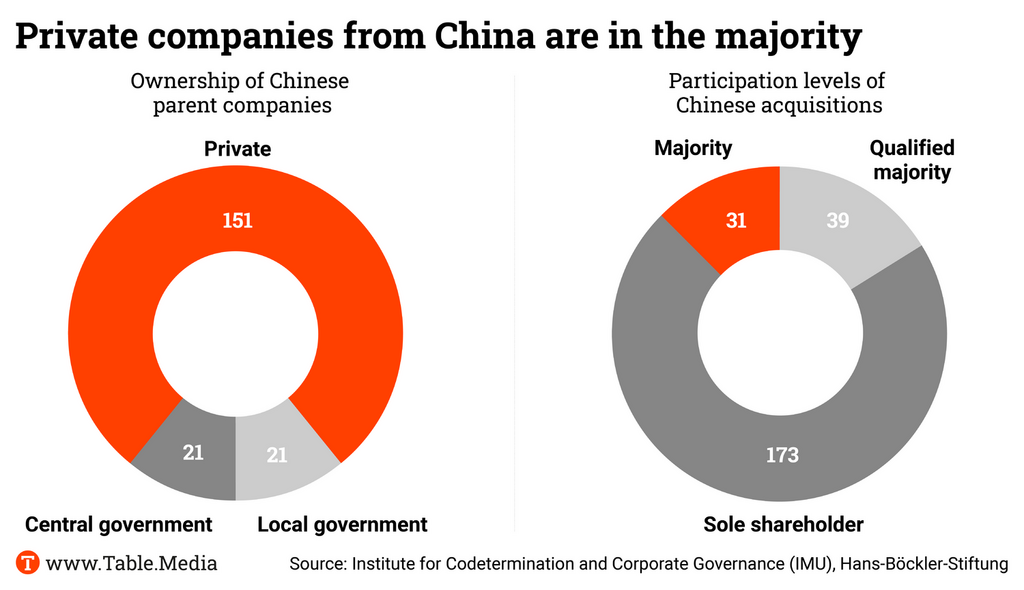

Yet the supposed gold rush of Chinese investors in Germany is over for now. Between 2011 and 2020, 193 investors acquired a total of 243 German companies either entirely or in part. With 48 takeovers, the year 2016 was the absolute peak, as the Institute for Co-determination and Corporate Governance of the Hans Boeckler Foundation calculated. In 2022, genuine greenfield start-ups exceeded takeovers of existing companies and facilities (brownfield) for the first time.

Trade unions, works councils and employees often expressed skepticism in the run-up to takeovers. Wrongly so, as hindsight now shows. “Chinese investors tend to have a long-term perspective on their investments, which is positive for the workforce. That’s different from more activist investors from other countries, who are strongly oriented towards the financial market, puff up the company and resell it quickly.” Romy Siegert told China.Table. She is responsible for transnational trade union policy at the German metalworkers’ union IG Metall and previously worked for four years at the Beijing branch of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

According to Siegert, three factors were important to investors when entering the market.

At least the first two aspects require a long-term perspective. The Chinese investors behaved accordingly in the negotiations. “In many cases, the takeovers included promises to secure production sites for several years. In addition, a lot of money flowed into the German subsidiaries for research and development,” Siegert explains, looking back.

The study “Chinesische Investitionen im Ruhrgebiet” (Chinese Investments in the Ruhr Area) by the Ruhr University Bochum comes to a similar conclusion. In it, an employee of ThyssenKrupp Tailored Blanks, a manufacturer of automotive sheet metal, which was sold to the Chinese WISCO in 2012, said: “If I had to choose between Chinese and Americans, I would rather choose Chinese. Americans are not concerned with workers’ rights, the Chinese accept them.”

However, trade unions and works councils have also done an enormous amount of information work during the various takeovers and investments. Chinese executives had to learn how German trade unions work, how they differ from works councils, and their rights and duties.

According to trade union sources, Chinese investors generally work with the legal framework they find – no matter where they are in the world. If there were hardly any co-determination and few labor laws, these instruments would not be introduced. For workers in Germany, this tends to be good news. For workers in many African countries, however, it is not. According to Siegert, Chinese investors are mainly afraid of bad publicity. They are interested in protecting the reputation of the company and the People’s Republic.

In most cases, the day-to-day work has not changed much either, Siegert analyzes. “Management structures rarely change directly during takeovers. Often, only a Chinese representative is appointed who is responsible for communication with the parent company. So the established co-determination structures – whether functionally better or worse – usually remain in place in interaction with corporate management.”

There have even been positive effects, especially in the manufacturing industry. For example, companies increased their production because Chinese investors (often) wanted to sell slimmed-down versions of the products on their domestic market or in developing countries.

André Merder and Till Pahmeier offer concrete insight into a company that Chinese investors have taken over. They are both members of the works council at Gotion Battery GmbH. The Chinese manufacturer acquired a Bosch plant in Goettingen in 2022. The two works councilors then spoke at the panel “New actors in the transformation to the EV: Challenge for co-determination through Chinese battery manufacturers,” held as part of the Hans Boeckler Foundation’s Labor.A platform.

The plant in question is about 70 years old. Under Bosch management, the approximately 240 employees still manufactured jump starters and generators for internal combustion engines. Starting in late 2023, the plant will produce batteries. This means the plant will be converted from a fairly manual production to a highly automated one. The upheaval is gigantic. The takeover is said to have been a mixture of a greenfield and a brownfield investment. In other words, a start-up and a takeover.

Suddenly, employees must be familiar with a high-voltage product’s dangers and requirements. “We don’t know the product and the processes. Da Gotion has been a good partner. There have been training programs in China to which many employees have been invited, and they have spent a long time on site,” Merder reports. On the other hand, the plant also had to undergo conversion work. All this costs time and money. Resources that Gotion is willing to invest.

While Bosch only promised to continue production at the plant until 2027, the Chinese investor now offers a long-term perspective. “The colleagues are very motivated. Because they now see a future that they didn’t see under Bosch,” Merder describes the mood. The works council supported the acquisition because of this future perspective, explains Pahmeier.

However, Stiegert reports that problems have emerged for the first time in the past two years. As economic development has slowed down in China, German subsidiaries also have to cut costs. But, there is often no direct communication between Chinese investors and workers’ representatives. This usually takes place via the German management. From IG Metall’s perspective, this is a problem.

This is one of the reasons why IG Metall founded the China-Invest Network. It unites workers’ representatives from companies with Chinese investors. It is about exchange and learning effects. This is particularly necessary with greenfield investments. Siegert observes that Chinese greenfield investments abroad are run with workers from the People’s Republic – for example, in Hungary. And the trade union does not like that at all.

German Sinology has a lot of work ahead of it. Understaffed, it cannot possibly meet the massive demand for China expertise in the face of rising demand. What’s more, the discipline is busy with itself at the moment.

Questions are circulating that shake its credibility. How independent is the discipline from the interests of the Chinese party-state? Is an overly critical approach towards the Communist Party prevented in German sinology? Has sinology sufficiently confronted its own Maoist past?

The issues are being emotionally debated because they strike at the very foundations of an elite discipline whose importance is increasing as China’s influence on global affairs grows, yet is increasingly ignored by young students. Part of the disciplinary body feels “unfairly pilloried” by those who accuse it of being compromised by a network that gives it better career opportunities.

The discussion about credibility is home-grown. Emeritus professors Thomas Heberer and Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer published a newspaper article about a trip to Xinjiang and recommended lifting EU sanctions against Chinese officials.

The duo earned widespread incomprehension, at least in Germany. Sinologist Kai Vogelsang from the University of Hamburg considers the “fatal misjudgments of the Chinese dictatorship,” such as those voiced by Heberer and Schmidt-Glintzer, in last weekend’s NZZ article not only an individual failure, but a surrender of sinology.

On the other hand, Chinese media saw the report as a confirmation of the Beijing government’s perspective that its crimes against humanity in Xinjiang are necessary. Most experts find it difficult to understand how two such seasoned Sinologists could have fallen months after their visit into the trap of an editorial team that wanted to see “hard theses” on such a delicate topic, one where Beijing is fighting tooth and nail to control the narrative.

For example, Heberer conducted intensive field research in the country long before China became the focus of attention as an economic partner. He developed an expertise in the discipline that continues to have an impact today. He benefited from connections to the Chinese party-state that had already been established in the 1970s through the Communist League of West Germany (KBW). Because of his deep understanding of the People’s Republic, he became an influential political advisor who accompanied German federal and state prime ministers on their trips to China.

As a young man in the 1970s, Heberer went to Beijing and worked for a local propaganda newspaper. In parallel, he researched ethnic minorities. By 1982, he had written several articles for the journal “Kommunismus und Klassenkampf,” the mouthpiece of the West German Communist League. In one article, he quoted Soviet dictator Josef Stalin with words of praise. So, he also owes his intimate knowledge of communist China to his ideological closeness to the system at the time.

All that was a long time ago. And Heberer was by no means the only one open to Maoism at that time. Take Reinhard Buetikofer, for example. The Green member of the European Parliament was also active in the KBW at that time. In the meantime, however, Buetikofer distanced himself from his youthful enthusiasm and is considered a critic of the Chinese party state.

Political scientist Andreas Fulda from the University of Nottingham sees no comparable distancing from Heberer. “I am not aware of any academic text in which he self-critically reflected on his political work in the 1970s and early 1980s. His later China science was blind to the dark side of Chinese autocracy and conveyed a false image of China for years,” says Fulda. He believes that the affair will lead to reforms in German sinology.

Sinologist Sascha Klotzbuecher from the University of Bratislava accuses his discipline of never having urged Heberer to distance himself more clearly and let the Communist Party’s wrongdoings flow into the country’s assessment, but instead to have “rallied around him.” Heberer explicitly pretended that field research required many years of cooperation with the authorities on the ground, which resulted in a strongly state-centric, technological-bureaucratic view. “The failure to recognize these potential conflicts of interest in this position and their roots remain a blind spot,” says Klotzbuecher.

Sinologist and Xinjiang expert Bjorn Alpermann, who has co-authored with Heberer in the past, says that it is no secret that Heberer once went to China as an enthusiastic Maoist. “Everyone knows that. And there were also always different opinions. But just because he used to be a Maoist doesn’t invalidate all of his academic work.” However, Alpermann also says that Heberer’s perspective on the People’s Republic constantly focuses on the progress of the party-state.

Heberer’s doctoral student, Christian Goebel, believes that any resulting original sin is a false conclusion. He says: “Just because I earned my PhD under Heberer, I don’t represent a certain position. Whenever we had different views, the discussion was productive and at eye level.”

Heberer’s past is widely known in the field of sinology. Outside the discipline, however, it is not. And that is the crux of the matter. After all, it is Heberer and other voices who strongly shape public perception in the China discourse with “unspeakable statements” (Goebel) like the one now about Xinjiang.

Sinologist and former director of the Confucius Institute at the FU Berlin, Mechthild Leutner, for example, repeatedly referred to the internment camps as vocational training and deradicalization centers in the German Bundestag. According to reports, Leutner was in Beijing with Heberer in the same month as Heberer and Schmidt-Glintzer’s Xinjiang trip in May 2023 to discuss political science research. Whether she also visited Xinjiang is unclear.

At any rate, Heberer defends himself. In an email to China.Table, he writes his latest publication has nothing to do with a need to confront the Maoist past of German sinology.

Schmidt-Glintzer also maintains good relations with Beijing. In 1984, he sat in the stands at Tiananmen Square when the People’s Republic celebrated its 35th national anniversary. Such recognition is certainly not bestowed on every Sinologist, only to those China considers a friend. He, too, faces the accusation of not considering the increasingly totalitarian form of government in his assessment of China.

In 2020, for instance, he described the infamous Document No. 9, an internal CCP strategy paper, as “exciting” and “no reason to be afraid.” The paper warns against Western values and their spread in China. Many China experts consider the document to be an indicator of the totalitarian tendencies of Xi Jinping’s regime.

Nevertheless, sinologist Vogelsang is convinced that a new generation of sinologists has grown up who “have theoretical acuity, conceptual precision and a critical eye” to prove that sinologists do not have to be “China-understanders” or “regime apologists” at all. “They just have to speak up,” Vogelsang demands.

Taiwan prosecutors said on Monday they are investigating accusations that people tried to interfere in the island’s submarine program and that details about it were leaked.

Huang Shu-kuang, who is leading the program, said a contractor who had not received the bid had leaked information to China. Taiwan’s Supreme Prosecutors Office, in a short statement, said Huang’s accusations had attracted “great attention” given the national security and defense implications. No details or names have yet been released.

Only last Thursday, Taiwan unveiled its first domestically developed submarine. It is Taiwan’s response to the growing threat from the People’s Republic. If secret information from the program leaked out – especially to China – it could be a severe setback to national security.

Beijing recently presented a plan for peaceful unification with Taiwan – with much pathos and emphasis on economic opportunities. However, Beijing is simultaneously sending more warships and fighter jets in Taiwan’s direction. rad

On Tuesday, the European Commission will reveal in which critical technologies it plans to pursue in de-risking relations with China. The list will be part of Brussels’ economic security strategy and will include microelectronics, quantum computing, robotics, artificial intelligence and biotechnology. The list is also intended to define an area for possible screening of outbound investments, which would follow the US model on investment restrictions, including semiconductors or AI.

In addition, two important China-related topics are on the agenda in the EU Parliament on Tuesday: First, the MEPs will formally vote on the Anti-Coercion Instrument. Secondly, the EU Commission must answer questions regarding trade relations with the People’s Republic. To this end, a debate with MEPs and a representative of the Commission is planned for 3 pm. ari

China’s reluctance to make new investments along the New Silk Road (Belt and Road Initiative, BRI) is apparently growing. According to the Japanese business newspaper Nikkei, China recently rejected Pakistan’s request for billions of dollars in new investment. The newspaper had insight into minutes of meetings between Pakistani and Chinese government representatives.

Pakistan reportedly requested new projects in the fields of energy supply and tourism. Among them was a power line between the port city of Gwadar and the country’s largest city, Karachi. China is said to have rejected them all.

Pakistan is among the most loyal Silk Road partners and has significantly benefited from Chinese investment. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is one of the most important Silk Road axes. However, China is currently slipping into a financial crisis and is already struggling to keep the yuan’s exchange rate reasonably stable. This could contribute to Silk Road weariness. fin

The World Trade Organization (WTO) recognizes an ominous fragmentation of global trade in goods. “We don’t see large-scale fragmentation yet, but there are early signs,” WTO chief Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala said Monday at an event in Geneva. She called the trend dangerous. It could also prove “very costly” in the end. “Let’s rethink globalization,” the Nigerian said.

With her comments, the WTO chief alluded to trends such as so-called friendshoring. This refers to the relocation of corporate processes to countries with similar values. For example, a number of Western corporations are looking for alternatives to China as a production country. The WTO chief also addressed “reshoring.” This term describes the relocation of production facilities from emerging countries back to developed countries. “Let us not do this,” Okonjo-Iweala commented on these two trends. rtr

The Chinese economy is underperforming relative to its growth potential. Not only are investment and consumption demand weaker than hoped, but the country is facing the challenge of two Ds: deflation and debt. While consumer-price inflation is close to negative territory, producer-price inflation has already been negative for a year. At the same time, the private and public sectors have accumulated massive debts, owing to higher spending during the pandemic and the broader response to the easy-money conditions of previous years.

The two Ds are a toxic combination. By increasing the real (inflation-adjusted) value of existing debt, deflation makes it harder for firms to secure additional financing, thereby raising the prospect of bankruptcies – a trend that is already discernible in China. Moreover, once the combination of debt and deflation becomes entrenched, it can generate a vicious cycle whereby lower demand leads to lower investment, lower output, lower income, and thus even lower demand.

This dangerous spiral has two implications for policymaking. To prevent deflationary expectations from becoming entrenched, increasing the inflation rate through aggregate-demand stimulus becomes an urgent necessity. But relying solely on more public or private borrowing is best avoided in favor of aggressive monetary easing – including the monetization of debt (meaning the central bank purchases and holds government bonds).

To be sure, Chinese authorities have pursued a variety of policies to boost the economy, including reducing mortgage interest rates, rescinding restrictions on real-estate firms’ access to funding, and implementing measures aimed at boosting domestic stock prices (with the hope that this will raise consumer spending). But these responses, so far, have not achieved the desired outcome.

Curiously, monetary-policy action – massive injection of more liquidity by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) – has not taken place. This restraint seems to reflect four considerations: a fear of triggering high inflation; perceived limited space for further monetary easing; a belief that monetary stimulus will have only a limited effect; and concerns about further renminbi depreciation against the US dollar and other key currencies.

But all four concerns are misplaced, given the current state of the Chinese economy. China should not be worried about inflation when it is already facing the opposite problem: a decline in prices and nominal wages across many sectors. If consumers and firms expect prices to fall in the future, they will delay purchases, further suppressing demand. Preempting the debt-deflation spiral must take priority.

Similarly, those who believe the scope for monetary easing was limited by already-low interest rates have it wrong. As Chinese financial authorities have now acknowledged, they can further reduce banks’ required reserve ratios, currently at 10.75 percent for large state-owned commercial banks and at 6 percent for other banks. Even though the required ratio for Chinese non-state-owned banks will fall to 4 percent starting on September 15, that is still high compared to the reserve ratios of 0 percent and 0.8 percent in the United States and Japan, respectively.

Moreover, like central banks in high-income countries after the 2008 financial crisis, the PBOC could still avail itself of quantitative easing, with large-scale purchases of government bonds giving commercial banks more liquidity for lending. If the goal is to achieve higher inflation – as is the case in China today – there is no mechanical limit on the additional stimulus that can be applied to the economy through this channel.

Some might doubt that monetary-policy easing will succeed in boosting aggregate demand, considering that the economy’s performance remained weak after previous cuts in the prime lending rate from 3.65 percent to 3.45 percent. But an insufficient increase in aggregate demand following a timid monetary stimulus is not proof that more aggressive easing would fail.

China needs the “whatever it takes” approach that the European Central Bank pursued a decade ago when it, too, was facing a debt-deflation spiral. The PBOC should publicly declare a strategy to monetize a big portion of government debt and to incentivize more private-equity investment.

To induce a general and coordinated increase in nominal wages, policymakers should consider a three-pronged approach featuring a reduction in employer contributions to the social-security fund in exchange for pay hikes; a fiscal transfer from the Ministry of Finance to the social-security fund, financed by long-term government bonds, to compensate for the lost contributions from firms; and monetization of that fiscal transfer by the PBOC (by buying and holding the government bonds). These measures can be reversed in the future, as needed, to combat inflation. For now, though, fighting the two Ds is much more important.

Finally, proposals for aggressive monetary easing tend to raise concerns about exchange-rate depreciation. The Chinese currency has lost about 5 percent of its value relative to the US dollar over the last 12 months, owing to asymmetric interest-rate changes in the US and China. The fear, now, is that additional renminbi depreciation could increase the expectation of further depreciation, triggering capital flight – a concern that has probably played some role in limiting the PBOC’s appetite for aggressive monetary easing.

But if the price of saving the economy from entrenched deflation is a weaker renminbi, it is a price worth paying – and could even serve as a useful adjustment mechanism by boosting foreign demand for Chinese products. Rather than trying to manage the exchange rate, which would artificially justify an expectation of depreciation, Chinese authorities should leave such adjustments to market forces. After all, a sufficiently sizable one-time depreciation would leave little room for further depreciation expectations.

China urgently needs to avoid entrenched deflationary expectations akin to what happened in Japan after the 1980s. It also urgently needs to restore business and household confidence, which is impossible without boosting aggregate demand. There is a strong case for immediate, aggressive monetary stimulus and a public commitment to halt the debt-deflation spiral.

Once China’s growth returns to the path of its growth potential, monetary policy can be normalized and the renminbi will naturally appreciate again.

Shang-Jin Wei, a former chief economist at the Asian Development Bank, is Professor of Finance and Economics at Columbia Business School and Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.

www.project-syndicate.org

Hou Angui is the new General Manager of China Baowu Steel, a major state-owned steel producer. He is also the group’s party secretary.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

The camel traffic jam is back. During Golden Week at the beginning of October, China’s domestic tourism is booming. In Dunhuang, a historic oasis town on the Old Silk Road, people gather to ride camels – so closely packed that traffic lights have been set up especially for the occasion. This is to prevent the caravans from stepping on each other’s hooves between the dunes.

Chinese investors as a horror for the workforce – this distorted image is outdated. Works councils and trade unions experience the same joys and hardships with Chinese owners as with domestic owners, writes Christian Domke Seidel. He extensively asked around among employee representatives of companies under Chinese ownership. One finding is that American investors have much less sympathy for co-determination than those from China.

Parts of German sinology are faced with demands to reappraise their past. Marcel Grzanna writes about this today. Many senior China researchers were granted access to the country in the 1970s because they harbored great sympathies for Maoism. This gave them an information advantage. In today’s climate, however, there is a call for them to clearly distance themselves from the stance of that time.

Whether it is the minority stake of the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) in the Port of Hamburg and Logistics (HHLA) or the investments of Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL) in the German state of Thuringia – politics, the public and competitors are usually very critical of Chinese investors. From a geopolitical or macroeconomic perspective, there may be reasons for this. However, the employees of the affected companies have less to worry about. Trade unions and works councils generally have positive experiences with investors from the People’s Republic.

Yet the supposed gold rush of Chinese investors in Germany is over for now. Between 2011 and 2020, 193 investors acquired a total of 243 German companies either entirely or in part. With 48 takeovers, the year 2016 was the absolute peak, as the Institute for Co-determination and Corporate Governance of the Hans Boeckler Foundation calculated. In 2022, genuine greenfield start-ups exceeded takeovers of existing companies and facilities (brownfield) for the first time.

Trade unions, works councils and employees often expressed skepticism in the run-up to takeovers. Wrongly so, as hindsight now shows. “Chinese investors tend to have a long-term perspective on their investments, which is positive for the workforce. That’s different from more activist investors from other countries, who are strongly oriented towards the financial market, puff up the company and resell it quickly.” Romy Siegert told China.Table. She is responsible for transnational trade union policy at the German metalworkers’ union IG Metall and previously worked for four years at the Beijing branch of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

According to Siegert, three factors were important to investors when entering the market.

At least the first two aspects require a long-term perspective. The Chinese investors behaved accordingly in the negotiations. “In many cases, the takeovers included promises to secure production sites for several years. In addition, a lot of money flowed into the German subsidiaries for research and development,” Siegert explains, looking back.

The study “Chinesische Investitionen im Ruhrgebiet” (Chinese Investments in the Ruhr Area) by the Ruhr University Bochum comes to a similar conclusion. In it, an employee of ThyssenKrupp Tailored Blanks, a manufacturer of automotive sheet metal, which was sold to the Chinese WISCO in 2012, said: “If I had to choose between Chinese and Americans, I would rather choose Chinese. Americans are not concerned with workers’ rights, the Chinese accept them.”

However, trade unions and works councils have also done an enormous amount of information work during the various takeovers and investments. Chinese executives had to learn how German trade unions work, how they differ from works councils, and their rights and duties.

According to trade union sources, Chinese investors generally work with the legal framework they find – no matter where they are in the world. If there were hardly any co-determination and few labor laws, these instruments would not be introduced. For workers in Germany, this tends to be good news. For workers in many African countries, however, it is not. According to Siegert, Chinese investors are mainly afraid of bad publicity. They are interested in protecting the reputation of the company and the People’s Republic.

In most cases, the day-to-day work has not changed much either, Siegert analyzes. “Management structures rarely change directly during takeovers. Often, only a Chinese representative is appointed who is responsible for communication with the parent company. So the established co-determination structures – whether functionally better or worse – usually remain in place in interaction with corporate management.”

There have even been positive effects, especially in the manufacturing industry. For example, companies increased their production because Chinese investors (often) wanted to sell slimmed-down versions of the products on their domestic market or in developing countries.

André Merder and Till Pahmeier offer concrete insight into a company that Chinese investors have taken over. They are both members of the works council at Gotion Battery GmbH. The Chinese manufacturer acquired a Bosch plant in Goettingen in 2022. The two works councilors then spoke at the panel “New actors in the transformation to the EV: Challenge for co-determination through Chinese battery manufacturers,” held as part of the Hans Boeckler Foundation’s Labor.A platform.

The plant in question is about 70 years old. Under Bosch management, the approximately 240 employees still manufactured jump starters and generators for internal combustion engines. Starting in late 2023, the plant will produce batteries. This means the plant will be converted from a fairly manual production to a highly automated one. The upheaval is gigantic. The takeover is said to have been a mixture of a greenfield and a brownfield investment. In other words, a start-up and a takeover.

Suddenly, employees must be familiar with a high-voltage product’s dangers and requirements. “We don’t know the product and the processes. Da Gotion has been a good partner. There have been training programs in China to which many employees have been invited, and they have spent a long time on site,” Merder reports. On the other hand, the plant also had to undergo conversion work. All this costs time and money. Resources that Gotion is willing to invest.

While Bosch only promised to continue production at the plant until 2027, the Chinese investor now offers a long-term perspective. “The colleagues are very motivated. Because they now see a future that they didn’t see under Bosch,” Merder describes the mood. The works council supported the acquisition because of this future perspective, explains Pahmeier.

However, Stiegert reports that problems have emerged for the first time in the past two years. As economic development has slowed down in China, German subsidiaries also have to cut costs. But, there is often no direct communication between Chinese investors and workers’ representatives. This usually takes place via the German management. From IG Metall’s perspective, this is a problem.

This is one of the reasons why IG Metall founded the China-Invest Network. It unites workers’ representatives from companies with Chinese investors. It is about exchange and learning effects. This is particularly necessary with greenfield investments. Siegert observes that Chinese greenfield investments abroad are run with workers from the People’s Republic – for example, in Hungary. And the trade union does not like that at all.

German Sinology has a lot of work ahead of it. Understaffed, it cannot possibly meet the massive demand for China expertise in the face of rising demand. What’s more, the discipline is busy with itself at the moment.

Questions are circulating that shake its credibility. How independent is the discipline from the interests of the Chinese party-state? Is an overly critical approach towards the Communist Party prevented in German sinology? Has sinology sufficiently confronted its own Maoist past?

The issues are being emotionally debated because they strike at the very foundations of an elite discipline whose importance is increasing as China’s influence on global affairs grows, yet is increasingly ignored by young students. Part of the disciplinary body feels “unfairly pilloried” by those who accuse it of being compromised by a network that gives it better career opportunities.

The discussion about credibility is home-grown. Emeritus professors Thomas Heberer and Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer published a newspaper article about a trip to Xinjiang and recommended lifting EU sanctions against Chinese officials.

The duo earned widespread incomprehension, at least in Germany. Sinologist Kai Vogelsang from the University of Hamburg considers the “fatal misjudgments of the Chinese dictatorship,” such as those voiced by Heberer and Schmidt-Glintzer, in last weekend’s NZZ article not only an individual failure, but a surrender of sinology.

On the other hand, Chinese media saw the report as a confirmation of the Beijing government’s perspective that its crimes against humanity in Xinjiang are necessary. Most experts find it difficult to understand how two such seasoned Sinologists could have fallen months after their visit into the trap of an editorial team that wanted to see “hard theses” on such a delicate topic, one where Beijing is fighting tooth and nail to control the narrative.

For example, Heberer conducted intensive field research in the country long before China became the focus of attention as an economic partner. He developed an expertise in the discipline that continues to have an impact today. He benefited from connections to the Chinese party-state that had already been established in the 1970s through the Communist League of West Germany (KBW). Because of his deep understanding of the People’s Republic, he became an influential political advisor who accompanied German federal and state prime ministers on their trips to China.

As a young man in the 1970s, Heberer went to Beijing and worked for a local propaganda newspaper. In parallel, he researched ethnic minorities. By 1982, he had written several articles for the journal “Kommunismus und Klassenkampf,” the mouthpiece of the West German Communist League. In one article, he quoted Soviet dictator Josef Stalin with words of praise. So, he also owes his intimate knowledge of communist China to his ideological closeness to the system at the time.

All that was a long time ago. And Heberer was by no means the only one open to Maoism at that time. Take Reinhard Buetikofer, for example. The Green member of the European Parliament was also active in the KBW at that time. In the meantime, however, Buetikofer distanced himself from his youthful enthusiasm and is considered a critic of the Chinese party state.

Political scientist Andreas Fulda from the University of Nottingham sees no comparable distancing from Heberer. “I am not aware of any academic text in which he self-critically reflected on his political work in the 1970s and early 1980s. His later China science was blind to the dark side of Chinese autocracy and conveyed a false image of China for years,” says Fulda. He believes that the affair will lead to reforms in German sinology.

Sinologist Sascha Klotzbuecher from the University of Bratislava accuses his discipline of never having urged Heberer to distance himself more clearly and let the Communist Party’s wrongdoings flow into the country’s assessment, but instead to have “rallied around him.” Heberer explicitly pretended that field research required many years of cooperation with the authorities on the ground, which resulted in a strongly state-centric, technological-bureaucratic view. “The failure to recognize these potential conflicts of interest in this position and their roots remain a blind spot,” says Klotzbuecher.

Sinologist and Xinjiang expert Bjorn Alpermann, who has co-authored with Heberer in the past, says that it is no secret that Heberer once went to China as an enthusiastic Maoist. “Everyone knows that. And there were also always different opinions. But just because he used to be a Maoist doesn’t invalidate all of his academic work.” However, Alpermann also says that Heberer’s perspective on the People’s Republic constantly focuses on the progress of the party-state.

Heberer’s doctoral student, Christian Goebel, believes that any resulting original sin is a false conclusion. He says: “Just because I earned my PhD under Heberer, I don’t represent a certain position. Whenever we had different views, the discussion was productive and at eye level.”

Heberer’s past is widely known in the field of sinology. Outside the discipline, however, it is not. And that is the crux of the matter. After all, it is Heberer and other voices who strongly shape public perception in the China discourse with “unspeakable statements” (Goebel) like the one now about Xinjiang.

Sinologist and former director of the Confucius Institute at the FU Berlin, Mechthild Leutner, for example, repeatedly referred to the internment camps as vocational training and deradicalization centers in the German Bundestag. According to reports, Leutner was in Beijing with Heberer in the same month as Heberer and Schmidt-Glintzer’s Xinjiang trip in May 2023 to discuss political science research. Whether she also visited Xinjiang is unclear.

At any rate, Heberer defends himself. In an email to China.Table, he writes his latest publication has nothing to do with a need to confront the Maoist past of German sinology.

Schmidt-Glintzer also maintains good relations with Beijing. In 1984, he sat in the stands at Tiananmen Square when the People’s Republic celebrated its 35th national anniversary. Such recognition is certainly not bestowed on every Sinologist, only to those China considers a friend. He, too, faces the accusation of not considering the increasingly totalitarian form of government in his assessment of China.

In 2020, for instance, he described the infamous Document No. 9, an internal CCP strategy paper, as “exciting” and “no reason to be afraid.” The paper warns against Western values and their spread in China. Many China experts consider the document to be an indicator of the totalitarian tendencies of Xi Jinping’s regime.

Nevertheless, sinologist Vogelsang is convinced that a new generation of sinologists has grown up who “have theoretical acuity, conceptual precision and a critical eye” to prove that sinologists do not have to be “China-understanders” or “regime apologists” at all. “They just have to speak up,” Vogelsang demands.

Taiwan prosecutors said on Monday they are investigating accusations that people tried to interfere in the island’s submarine program and that details about it were leaked.

Huang Shu-kuang, who is leading the program, said a contractor who had not received the bid had leaked information to China. Taiwan’s Supreme Prosecutors Office, in a short statement, said Huang’s accusations had attracted “great attention” given the national security and defense implications. No details or names have yet been released.

Only last Thursday, Taiwan unveiled its first domestically developed submarine. It is Taiwan’s response to the growing threat from the People’s Republic. If secret information from the program leaked out – especially to China – it could be a severe setback to national security.

Beijing recently presented a plan for peaceful unification with Taiwan – with much pathos and emphasis on economic opportunities. However, Beijing is simultaneously sending more warships and fighter jets in Taiwan’s direction. rad

On Tuesday, the European Commission will reveal in which critical technologies it plans to pursue in de-risking relations with China. The list will be part of Brussels’ economic security strategy and will include microelectronics, quantum computing, robotics, artificial intelligence and biotechnology. The list is also intended to define an area for possible screening of outbound investments, which would follow the US model on investment restrictions, including semiconductors or AI.

In addition, two important China-related topics are on the agenda in the EU Parliament on Tuesday: First, the MEPs will formally vote on the Anti-Coercion Instrument. Secondly, the EU Commission must answer questions regarding trade relations with the People’s Republic. To this end, a debate with MEPs and a representative of the Commission is planned for 3 pm. ari

China’s reluctance to make new investments along the New Silk Road (Belt and Road Initiative, BRI) is apparently growing. According to the Japanese business newspaper Nikkei, China recently rejected Pakistan’s request for billions of dollars in new investment. The newspaper had insight into minutes of meetings between Pakistani and Chinese government representatives.

Pakistan reportedly requested new projects in the fields of energy supply and tourism. Among them was a power line between the port city of Gwadar and the country’s largest city, Karachi. China is said to have rejected them all.

Pakistan is among the most loyal Silk Road partners and has significantly benefited from Chinese investment. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is one of the most important Silk Road axes. However, China is currently slipping into a financial crisis and is already struggling to keep the yuan’s exchange rate reasonably stable. This could contribute to Silk Road weariness. fin

The World Trade Organization (WTO) recognizes an ominous fragmentation of global trade in goods. “We don’t see large-scale fragmentation yet, but there are early signs,” WTO chief Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala said Monday at an event in Geneva. She called the trend dangerous. It could also prove “very costly” in the end. “Let’s rethink globalization,” the Nigerian said.

With her comments, the WTO chief alluded to trends such as so-called friendshoring. This refers to the relocation of corporate processes to countries with similar values. For example, a number of Western corporations are looking for alternatives to China as a production country. The WTO chief also addressed “reshoring.” This term describes the relocation of production facilities from emerging countries back to developed countries. “Let us not do this,” Okonjo-Iweala commented on these two trends. rtr

The Chinese economy is underperforming relative to its growth potential. Not only are investment and consumption demand weaker than hoped, but the country is facing the challenge of two Ds: deflation and debt. While consumer-price inflation is close to negative territory, producer-price inflation has already been negative for a year. At the same time, the private and public sectors have accumulated massive debts, owing to higher spending during the pandemic and the broader response to the easy-money conditions of previous years.

The two Ds are a toxic combination. By increasing the real (inflation-adjusted) value of existing debt, deflation makes it harder for firms to secure additional financing, thereby raising the prospect of bankruptcies – a trend that is already discernible in China. Moreover, once the combination of debt and deflation becomes entrenched, it can generate a vicious cycle whereby lower demand leads to lower investment, lower output, lower income, and thus even lower demand.

This dangerous spiral has two implications for policymaking. To prevent deflationary expectations from becoming entrenched, increasing the inflation rate through aggregate-demand stimulus becomes an urgent necessity. But relying solely on more public or private borrowing is best avoided in favor of aggressive monetary easing – including the monetization of debt (meaning the central bank purchases and holds government bonds).

To be sure, Chinese authorities have pursued a variety of policies to boost the economy, including reducing mortgage interest rates, rescinding restrictions on real-estate firms’ access to funding, and implementing measures aimed at boosting domestic stock prices (with the hope that this will raise consumer spending). But these responses, so far, have not achieved the desired outcome.

Curiously, monetary-policy action – massive injection of more liquidity by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) – has not taken place. This restraint seems to reflect four considerations: a fear of triggering high inflation; perceived limited space for further monetary easing; a belief that monetary stimulus will have only a limited effect; and concerns about further renminbi depreciation against the US dollar and other key currencies.

But all four concerns are misplaced, given the current state of the Chinese economy. China should not be worried about inflation when it is already facing the opposite problem: a decline in prices and nominal wages across many sectors. If consumers and firms expect prices to fall in the future, they will delay purchases, further suppressing demand. Preempting the debt-deflation spiral must take priority.

Similarly, those who believe the scope for monetary easing was limited by already-low interest rates have it wrong. As Chinese financial authorities have now acknowledged, they can further reduce banks’ required reserve ratios, currently at 10.75 percent for large state-owned commercial banks and at 6 percent for other banks. Even though the required ratio for Chinese non-state-owned banks will fall to 4 percent starting on September 15, that is still high compared to the reserve ratios of 0 percent and 0.8 percent in the United States and Japan, respectively.

Moreover, like central banks in high-income countries after the 2008 financial crisis, the PBOC could still avail itself of quantitative easing, with large-scale purchases of government bonds giving commercial banks more liquidity for lending. If the goal is to achieve higher inflation – as is the case in China today – there is no mechanical limit on the additional stimulus that can be applied to the economy through this channel.

Some might doubt that monetary-policy easing will succeed in boosting aggregate demand, considering that the economy’s performance remained weak after previous cuts in the prime lending rate from 3.65 percent to 3.45 percent. But an insufficient increase in aggregate demand following a timid monetary stimulus is not proof that more aggressive easing would fail.

China needs the “whatever it takes” approach that the European Central Bank pursued a decade ago when it, too, was facing a debt-deflation spiral. The PBOC should publicly declare a strategy to monetize a big portion of government debt and to incentivize more private-equity investment.

To induce a general and coordinated increase in nominal wages, policymakers should consider a three-pronged approach featuring a reduction in employer contributions to the social-security fund in exchange for pay hikes; a fiscal transfer from the Ministry of Finance to the social-security fund, financed by long-term government bonds, to compensate for the lost contributions from firms; and monetization of that fiscal transfer by the PBOC (by buying and holding the government bonds). These measures can be reversed in the future, as needed, to combat inflation. For now, though, fighting the two Ds is much more important.

Finally, proposals for aggressive monetary easing tend to raise concerns about exchange-rate depreciation. The Chinese currency has lost about 5 percent of its value relative to the US dollar over the last 12 months, owing to asymmetric interest-rate changes in the US and China. The fear, now, is that additional renminbi depreciation could increase the expectation of further depreciation, triggering capital flight – a concern that has probably played some role in limiting the PBOC’s appetite for aggressive monetary easing.

But if the price of saving the economy from entrenched deflation is a weaker renminbi, it is a price worth paying – and could even serve as a useful adjustment mechanism by boosting foreign demand for Chinese products. Rather than trying to manage the exchange rate, which would artificially justify an expectation of depreciation, Chinese authorities should leave such adjustments to market forces. After all, a sufficiently sizable one-time depreciation would leave little room for further depreciation expectations.

China urgently needs to avoid entrenched deflationary expectations akin to what happened in Japan after the 1980s. It also urgently needs to restore business and household confidence, which is impossible without boosting aggregate demand. There is a strong case for immediate, aggressive monetary stimulus and a public commitment to halt the debt-deflation spiral.

Once China’s growth returns to the path of its growth potential, monetary policy can be normalized and the renminbi will naturally appreciate again.

Shang-Jin Wei, a former chief economist at the Asian Development Bank, is Professor of Finance and Economics at Columbia Business School and Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.

www.project-syndicate.org

Hou Angui is the new General Manager of China Baowu Steel, a major state-owned steel producer. He is also the group’s party secretary.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

The camel traffic jam is back. During Golden Week at the beginning of October, China’s domestic tourism is booming. In Dunhuang, a historic oasis town on the Old Silk Road, people gather to ride camels – so closely packed that traffic lights have been set up especially for the occasion. This is to prevent the caravans from stepping on each other’s hooves between the dunes.