Low-priced competition from the Far East has already been the downfall of several German industries. Televisions, cameras, solar cells, raw materials for antibiotics, toys. This pattern is so deeply rooted that fears about it quickly flare up. Now, the Chinese government is ramping up its subsidy machinery to pave the way to the EU for its own wind turbine manufacturers. Lush profits beckon in Europe. After all, the huge undertaking of breaking away from geopolitically and climate-politically damaging energy sources is in motion. But all is not lost for companies like Vestas and Gamesa, analyzes Nico Beckert. A 100-meter-long rotor for a wind turbine cannot simply be packed into a container like a solar cell.

China’s tough regulation of Internet companies (the “tech crackdown”) is also perceived as something rather sinister in the West. Isn’t the CP consolidating its power in this way? In fact, the motivations are very similar to those of Western regulators, for whom the power of individual companies goes too far. One example last year was Tencent, whose music streaming division has created a monopoly. Frank Sieren has taken a look at the impact of the breakup of the cartel of Tencent subsidiaries. As a result, there are now more pieces of the pie for everyone: Competitors have breathing room – and even for Tencent, things didn’t go as badly as feared.

Last year, Huawei made more profit than ever before. At first glance, this comes as a surprise. After all, US sanctions had brought the company’s smartphone division to its knees. But Huawei is not just a provider of electronics for end customers. You will find all background information on this surprising profit surge in our analysis.

The lockdown of Shanghai is also a topic today. DHL has suspended cargo operations at its Pudong hub. All citizens have to be tested twice. Only China is able to keep 26 million inhabitants of a bustling metropolis in their homes.

The European Union wants to expand renewable energies faster as a result of the Russian war in Ukraine. And wind power plays a major role. By 2030, 480 gigawatts of wind capacity are to be connected to the grid. Before the Ukraine shock, only 450 gigawatts were projected. The 2030 target has thus been increased by an additional 30 gigawatts.

So these are golden times for the European wind power industry – one might think. But the competition from China is pushing stronger on the global market and could profit from Europe’s wind power expansion. The European industry is therefore already warning of a loss of market share. However, a repeated disaster like the complete elimination of the German solar industry by overwhelming competitors from the Far East is not to be expected.

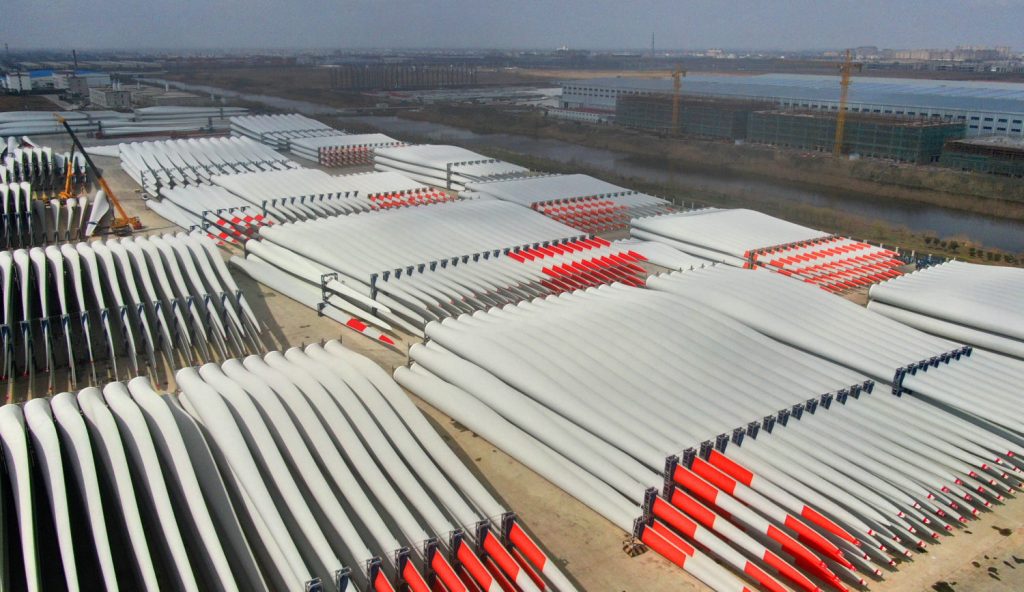

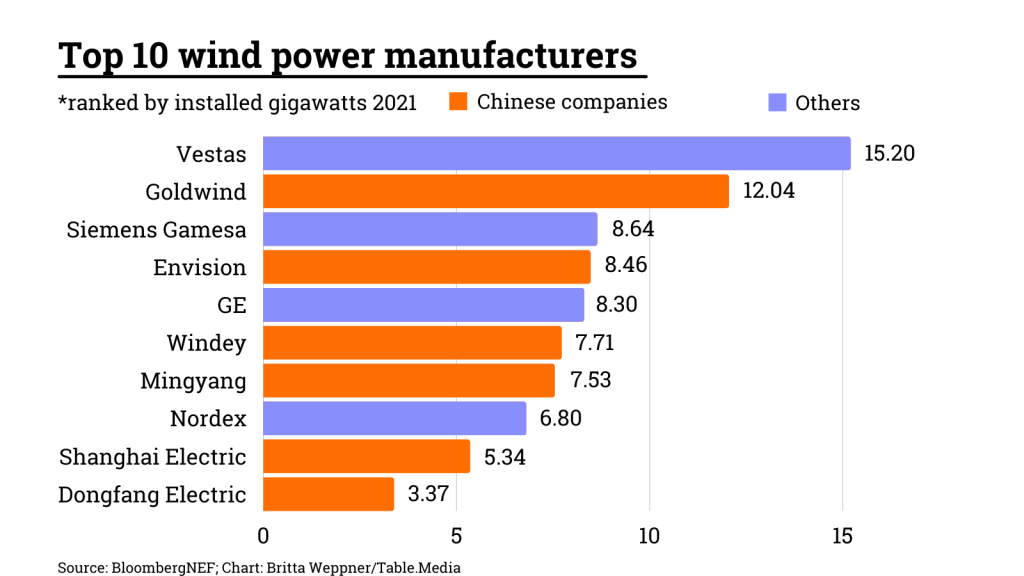

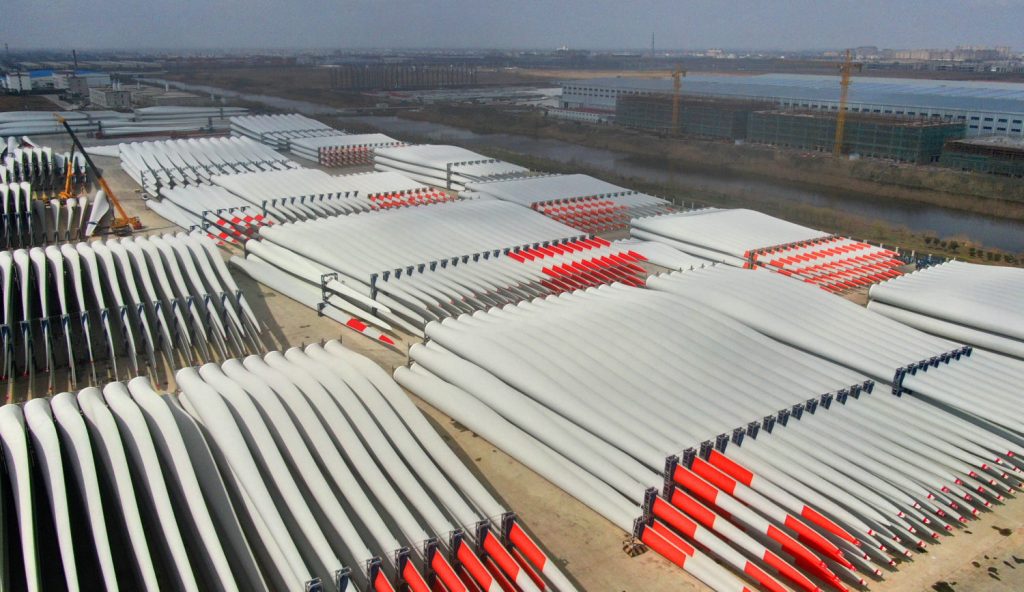

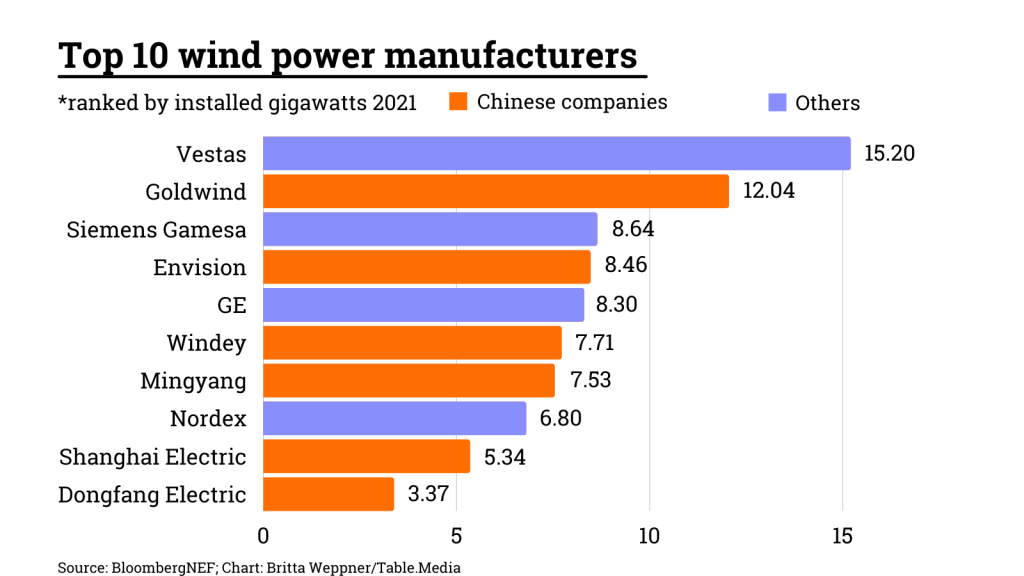

China’s wind industry has grown rapidly in recent years. Half of the wind turbine components manufactured worldwide are produced in China. Six of the ten largest manufacturers come from the People’s Republic. Since 2019, Europe’s annual imports of wind turbines from China have almost doubled from €211 million to €411 million last year. European competitors are faltering at the same time. Four of five European manufacturers reported losses last year. As a result, they are closing factories and cutting jobs. In Germany alone, more than 50,000 jobs have been lost in the wind industry over the past six years, according to industry data.

All signs point to the same fate for the European wind industry as for the solar industry. But this conclusion is premature. With Vestas and Siemens Gamesa, two of the world’s five largest wind companies are from Europe. And despite rising imports, China’s position has yet to gain a strong foothold in Europe. The majority of China’s huge production capacity is used for the People’s Republic’s own massive expansion of wind power. But it is precisely this massive expansion that is scaring Europe’s wind industry. A strong foundation at home also allows for international expansion. Chinese suppliers compete with unbeatable prices and have also caught up technologically.

Its large domestic market favors Chinese suppliers. “The sheer scale of its manufacturing capacity affords China a major competitive advantage” in the wind energy market, says Xiaoyang Li of research and consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. Industry representatives in Germany are also viewing the developments with concern. “In the largely closed-off but high-volume Chinese market, Chinese manufacturers have come close to European performance levels from a technological perspective,” says Wolfram Axthelm, Managing Director of the German WindEnergy Association. “We have seen in the past how Chinese companies penetrate new markets with government assistance.”

The situation in Europe is quite the opposite, according to the industry association Windeurope. “The small size of the market is really hurting the supply chain,” says an open letter from the association to EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. “The problem is not government ambition on climate action and renewables,” writes Christoph Zipf of Windeurope. “Europe is simply not permitting anything like the volumes that you and the national governments want to build.” As a result, the energy transition is being delayed.

Because demand in Europe is not sufficient, the sector is at a disadvantage against China. On the global market, the European industry is already losing market share to China. And Chinese suppliers are increasingly securing contracts to build wind farms in Europe – for example, in Italy, France, Croatia, and Serbia, the association writes.

A decision made by China’s Ministry of Finance could further widen the imbalances. The ministry recently allocated $63-billion to pay out promised subsidies more quickly. Most of the money will go to wind and solar power plant developers, Bloomberg reports. Subsidy debts had piled up in recent years as renewable energy expanded faster than the government could hand out the subsidy money. The payment arrears had affected the entire supply chain, according to an industry insider. The release of the funds would now give the industry a boost.

While Chinese companies are strengthening their competitiveness, European companies are losing market share in the People’s Republic. In 2021, construction projects by foreign wind turbine manufacturers have halved. Foreign companies’ costs for onshore turbines in China are nearly twice as high as those of domestic suppliers. Prices for Chinese wind turbines fell 24 percent in 2021, according to Wood Mackenzie. In 2022, they will drop by another 20 percent, the research and consulting firm predicts. In addition, there are regulations that “largely close off” the market to foreign companies, Axthelm says.

The increase in competitiveness favors the global expansion of Chinese suppliers. Wood Mackenzie analysts conclude that Chinese companies have so far focused on the domestic market, but are likely to compete more strongly on the global market in the coming years as they have been able to lower their prices, while European and US manufacturers are struggling with rising material costs.

Will wind turbine manufacturing relocate from Europe to China? That is unlikely. After all, the wind industry is very different from the solar industry. Solar module manufacturers manufacture a mass product that can easily be transported halfway around the globe. The wind industry is much more complex. Turbines include up to 8,000 components, writes Ilaria Mazzocco. “Wind turbine manufacturers are usually also directly involved in maintenance and installation,” says the China energy expert from the Center for Strategic & International Studies. Turbine manufacturers often maintain a local presence.

This is why some Chinese suppliers are also planning to set up production facilities in Europe. European manufacturers are taking this new competition seriously. Mazzocco believes it is unlikely that Chinese suppliers will completely push out other leading companies and existing supply chains. Regulations on local value creation also suggest otherwise.

Bloomberg NEF estimates that these regulations will become more important in the future and that “qualitative criteria” will play a greater role in awarding contracts. Price could therefore lose significance as a decisive factor. This is also supported by new EU guidelines for government aid for climate, environmental protection, and energy. They allow governments to place greater focus on other criteria, such as local value creation when awarding contracts.

Almost a year ago, Tencent already felt the new power of China’s antitrust authorities. Since then, the tech giant from Shenzhen in southern China, which owns several successful streaming services like Tencent Music, is no longer allowed to sign exclusive music licensing agreements for China with global record labels like Warner or Universal. The ban follows a decree by China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), which wants to prevent Tencent Music from further expanding its monopoly in the music industry.

Tencent Music Entertainment Group (TME), which began trading in New York in December 2018, operates three popular streaming platforms in China, QQ Music, KuGou Music and Kuwo Music. Together, these three platforms have a 71 percent market share in China. That is too much even by Western cartel standards. Therefore, Beijing has imposed strict new regulations: exclusive music licensing agreements had to be terminated within 30 days.

As a result, Tencent channels lost permission, for example, to market music by Jay Chou, probably Asia’s biggest pop star, exclusively in China. The Taiwanese singer and rapper has sold more than 30 million records in the past 20 years. That is only about 20 percent of what US rapper Kanye West has sold in the same period, but for Asia, this is still a remarkable number.

Tencent Music is no longer able to acquire the exclusive rights to the catalogs of Universal Music Group, Sony Music or Warner Music Group and then sell them to smaller platforms such as NetEase, Alibaba and Xiaomi. The stock market reacted swiftly: Within a year, the share price plunged by more than 80 percent, like all tech stocks that are affected by the wave of new antitrust laws with which antitrust authorities want to revive the market economy.

Now, almost exactly one year later, the consequences of the new policy are starting to show. The business collapse that investors feared has failed to materialize. The government intervention has not destroyed Tencent Music’s business model, and at the same time has given competitors more room to grow. This means that the industry as a whole continues to grow, and Tencent is benefiting from this. But the competition has more breathing room.

The number of paying Tencent users grew by more than 36 percent to over 76 million in 2021, despite antitrust regulations. Revenue grew by 7.2 percent to the equivalent of $4.9 billion, Tencent reported. The online music service even grew by more than 22 percent. Subscriptions by 33 percent. Tencent saw this overall increase even though it suffered a 7.6 percent drop in revenue last quarter. This was mainly the result of Covid-related lower revenues from clubbing and live streaming.

The crackdown has thus primarily sent Tencent’s share price plummeting, and it has yet to recover. The government has already taken appropriate measures (China.Table reported) and the share price has risen. But those who got in on Tencent Music’s 2018 IPO still lost more than half their investment.

In part, however, the lower valuation is justified. After all, the biggest winners of the reforms are the other 15 different audio streaming services with at least one million daily active users, which previously only had to compete for a market share of 30 percent and will now be able to massively expand.

NetEase is a prime example of how the new policy is already taking effect. NetEase Cloud Music is Tecent’s biggest competitor. In 2021, its revenues grew by nearly 43 percent, six times faster than top dog Tencent. The platform, founded in 2013, had 181 million monthly active users and a library of about 60 million tracks as of December last year.

Thanks to regulations, NetEase can better utilize its unique selling proposition against Tencent. Namely, its comment function, a very own social media feature. Around 25 percent of NetEase users comment below songs and artist pages, while 61 percent of users actively follow these comments. That’s a lot more than on Tencent.

Because many users not only listen to the music but also pour out their hearts in the process, NetEase is also known as the “streaming club of lonely hearts” among Chinese Internet users. In response, NetEase has even set up a “Healing Center” where listeners can find emotional support. The price models of Tencent and NetEase also differ. The annual subscription for NetEase Music costs the equivalent of about $26, which is slightly more than its competitor Tencent Music.

For years, NetEase Music executives had complained that they had to pay “two to three times the reasonable cost” for content under a sublicensing agreement with Tencent Music. Intervention by the National Copyright Administration (NCA) back in 2018 led to an agreement between the two companies to share up to 99 percent of their music content. However, the agreement turned out to be a sham. The remaining one percent included the most popular and top-selling artists. That is now over.

What is also politically interesting is that Chinese antitrust authorities were not bothered by Tencent Music’s international influence. In late 2017, Spotify and Tencent Music agreed to exchange shares between them. Spotify received a 9 percent stake in Tencent Music Entertainment Group, while Tencent also received a 9 percent stake in Spotify via two companies.

As a result, Spotify was profitable for the first time. Critics consider the mutual stake between the biggest player in China and the biggest player in the world to be a kind of cartel. Tencent has also owned ten percent of the American Universal Music Group since 2019. A year later, Tencent bought 5.2 percent of Warner Music Group. This means that the Chinese have a stake in the two leading US music and entertainment labels. Political decoupling pressure is not being felt in this sector, neither from Washington nor from Beijing.

The market prospects for China’s big players are promising. In the past ten years, the number of music streaming subscribers has increased by 80 percent. With the rise in the share of the middle class in the total population, this trend is expected to continue. Currently, there are still under 100 million subscribers. Only at 300 million, China would have the same ratio per capita as the USA.

It was the first major appearance of the daughter of Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei since September 2021, when Meng Wangzhou was released after three years of house arrest in Canada and returned to her home country amid huge media coverage. On Monday afternoon, she presented the annual report of the network equipment provider from Shenzhen in southern China as CFO.

Her appearance felt like a bold and defiant message to Canada and the United States. US courts had accused her of undermining sanctions against Iran. In return, China had detained two Canadian citizens for three years and charged them with rather vague charges of espionage. Shortly after Meng’s release for lack of evidence, the Canadians were also released.

Now Meng is back in business and presented surprisingly good financial figures. With a revenue of around $100 billion, Huawei achieved a remarkable profit margin of over 17 percent: $17.8 billion. And this is even though sales dropped significantly – by a whopping 29 percent – in what were politically challenging times for the company.

Meng cited several reasons for the revenue decline. US restrictions on the company hampered growth due to a lack of supplier parts. Added to this was the pressure from the pandemic. But there were also company-specific reasons. Most importantly: The collapse of the smartphone business – because the upgrade to 5G had been completed in China, demand had temporarily dropped in this sector.

The profit margin is all the more surprising because the share for R&D has also climbed by more than 22 percent to a good $22 billion. These investments cannot be monetized for at least a few years – if at all. Huawei’s CEO Guo Ping emphasized that the company also intends to further expand its R&D investments: “It makes a lot of economic sense to open up new technology areas instead of expanding old ones, even if the expense is high.”

CFO Meng, therefore, noted that “we are increasingly successful in dealing with uncertainties.” This was also reflected in the financial liabilities. Profits had not been generated on excessive debt, as is often the case in China. On the contrary, the debt to equity ratio was reduced to 57.8 percent.

Two factors are likely to have helped the bottom line. Huawei is not a state-owned company, even though it is said to maintain close ties to the state and the Party given its strategic importance. Moreover, it is not listed on the stock exchange. That is why the company is not pressured by quarterly figures or direct political influence. Management can afford to take its time in research and development.

CEO Guo identifies the search for new talent, scientific research, and the spirit of unity as the most important development goals. Huawei would rather break new technological ground than make a quick buck with small improvements to existing technology. A year ago, for example, the company managed to surprise the world with a complete system for autonomous driving. At a time when the smartphone division had collapsed due to US sanctions and Huawei had lost its position as the global market leader.

This strategy is a risky one because R&D does not automatically result in a breakthrough. To minimize the risks, Huawei does not place all its eggs in one basket, but conducts research in many different areas simultaneously. In this way, the company also achieved lucrative growth in smart wearables and smart screens, each of which grew by more than 30 percent year-on-year.

On the other hand, it was impossible to predict that Huawei’s smartphone operating system would not be of any international significance due to US sanctions. Having learned an important lesson, Meng also remains vague about the future direction of the company, leaving it at three keywords: digital transformation, artificial intelligence, and technology to reduce global carbon emissions. Frank Sieren

Standing in line for mass tests and take-out meals only: Shanghai’s 26 million citizens are coming to terms with the state of emergency. Starting Monday, the city government had surprisingly ordered a lockdown to stop the spread of Sars-CoV-2. After Omicron gained a foothold in the densely populated metropolis, concerns grew that the city could suffer a similar fate to Hong Kong. On Sunday alone, 3450 asymptomatic Covid cases were reported in Shanghai. Public life is being shut down in two stages until April 5 due to the rising number of new Covid infections. Bridges and tunnels have already been closed and highway traffic restricted.

Public transportation, such as subways and buses, have also stopped operating since Sunday evening. Apartment blocks have been cordoned off with yellow plastic walls. Police are urging citizens to comply with the regulations. A curfew is in effect for large parts of the city. Employees of most companies are only allowed to work from home.

Meanwhile, long queues have formed at testing centers. Every citizen is to be tested twice to detect infections in the population. “The Shanghai outbreak is characterized by regional clusters and infections spread across the city,” said Wu Fan of the city government’s pandemic task force. But the abruptly imposed lockdown has also led to problems. Delivery services are overwhelmed by the many orders, companies are without employees.

Many supermarket shelves are empty: Shortly before the start of the lockdown in Shanghai, many residents of the metropolis took advantage of the last chance before isolation to stock up on supplies. The lockdown is supposed to be limited to a few days. But the shopping frenzy of citizens indicates that they do not really trust the announcement and are preparing for a longer lockdown.

The lockdown may also affect more than 2,100 German companies that are operating there, according to the German Chamber of Commerce Abroad. ThyssenKrupp, for example, operates a local plant that manufactures steering systems and dampers for the automotive industry. Production will be continued, the company stated. The plant employs several hundred people.

Meanwhile, Deutsche Post has temporarily shut down its major air cargo hub at Pudong Airport. According to a company spokeswoman, this hub is one of four transshipment hubs in the DHL network in the region, with others in Hong Kong, Tokyo and Singapore. The company promised to keep its logistics customers informed about further developments.

German business fears that the Covid lockdown will primarily cause problems for already strained supply chains. “The mood among German businessmen is noticeably gloomy thanks to the new lockdown and already dampened growth expectations,” Volker Treier, Head of Foreign Trade at the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce (DIHK), told Reuters.

For now, however, the port of Shanghai is operating as usual. “This could limit damage to global supply chains,” said trade expert Vincent Stamer of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). “Problems in transporting goods to the port, however, could also manifest as longer shipping times of goods. fin/rtr/grz

China’s largest listed coal company, Shenhua Energy Co., wants to focus more on clean energy in the future. To this end, Shenhua wants to divert at least 40 percent of its annual investments into renewables until 2030.

Last year, Shenhua had invested just 0.08 percent of its spending on renewable energy. The company is part of the state-owned China Energy Investment Corp. which was the largest coal mining company in 2021, producing 570 million tons of coal. According to company data, Shenhua produced 177 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions from burning coal during the same period.

The Chinese government is expanding renewable energy capacity to peak CO2 emissions by 2030 at the latest. Despite the rapid growth of renewables, however, China remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels, with more than half of its power generated by coal-fired power plants.

Beijing recently announced plans to build five new coal-fired power plants (China.Table reported) and to increase the supply of coal. The decision was partly due to a widespread power shortage in the country in the fall of last year, when numerous companies and private households had to massively restrict their consumption.

By the same token, state-owned China Energy Investment is also the world’s second-largest renewable energy developer, with more than 41 gigawatts of power generation projects, according to data compiled by BloombergNEF. Most of its renewable projects to date have been through Longyuan Power Group Corp, another listed subsidiary. niw

The influx of disinformation from China to Europe has increased significantly in the past year. This is according to the 2021 activity report of the Strategic Communication Task Forces and Information Analysis Division. It is part of the European External Action Service (EEAS) and identifies foreign disinformation, lies and influence from abroad.

Above all, disinformation in connection with COVID-19 has increased. In many cases, their origin could be traced back to agencies “directly or indirectly linked to Chinese authorities.” Chinese officials and state-controlled media have spread allegations “that sow doubts about the origin of the virus and the safety of Western vaccines”.

Moreover, China had “promoted the underlying message that its own system of government is a better alternative to Western democracies” In the process, “there have been occasional alignments with and amplification of pro-Kremlin conspiracy narratives“ by Chinese actors. This trend has also been evident recently in the Ukraine war, the StratCom report said.

The manner of disinformation from the People’s Republic was often characterized by “harsh messaging through official channels.” There have also been attempts to silence critical voices or spread positive narratives about China via influencers. Especially in the Western Balkans, China has an increasing influence on media and social networks.

Most recently, the EU Parliament had called for tougher action against disinformation campaigns and foreign influence (China.Table reported). ari

Joern-Carsten Gottwald is mindful about what he says publicly about China. He is a member of the advisory board of Merics (Mercator Institute for China Studies), which has been placed on the Chinese government’s sanctions list. He is not interested in jeopardizing his partnerships.

As a professor of East Asian politics, the 51-year-old primarily focuses on bilateral relations between Europe and China. “We are actually on the way from a strategic partnership to a triad,” he says, picking up on a phrase that describes the complicated, since contradictory, relationship as partner, competitor and rival. This applies to many important issues: China, for instance, is a partner in global climate protection, a competitor in global markets, and a country that increasingly imposes alternative norms and values in international politics and challenges established democracies – like Germany.

As a scientist, Joern-Carsten Gottwald sees his task as bringing objectivity to this area of conflict. He also wants to show his students how important this is, especially in times of propaganda and fake news. “There has been an incredible change of sentiment in relations between China and the EU,” he says. In the 2000s and 2010s, there had been a China euphoria, which was naïve in many ways. And now, the threat posed by China is being exaggerated in many ways. “It’s important to maintain a certain sobriety in science, that is, not to be carried away by moods and currents in one direction or the other.”

His research involves, on the one hand, Chinese documents, which he tracks down, sifts through, evaluates, and then supplements with expert interviews. Normally, he also travels regularly to China to speak with as many stakeholders and decision-makers as possible. The latter has now become difficult – for political reasons and also because of the Covid pandemic, which makes cooperation with Chinese experts more difficult: Maintaining personal contacts now happens almost entirely virtual due to travel restrictions.

Online communication, for its part, brings its own problems, because platforms like Zoom are not one hundred percent safe. “I experience a certain caution about holding professional conversations with colleagues online or asking questions. The reason for this is the censorship of platforms and the stronger role of ideology in research in the People’s Republic of China,” explains the expert.

Academic teaching is also affected by these difficulties. Not just since a hacker attack on his university in May 2020 has Joern-Carsten Gottwald carefully pondered how he can protect his students from their statements being used against them during online events. Another problem is that fewer international students are now able to study in Bochum. And for German students, studying abroad in the region is mandatory per university regulations. They cannot be substituted by Zoom.

This is something that Joern-Carsten Gottwald knows from first-hand experience, of course. He stayed in Shanghai in 2013 and in Taiwan in 2019 as a visiting scholar, accompanied by his wife and children, who are now 16 and 18 years old. Personal interactions were also the reason that brought him to East Asia in the first place back in the 1990s: “I had already read a lot during my A-levels and then met a person who had studied Sinology. I particularly enjoyed Chinese philosophy,” he recalls. In the thirty years that have passed since then, his fascination with China has experienced some highs and lows. What never changed during that time, however, was his enthusiasm for Chinese food, the professor recounts with a wink: “Any kind of jiaozi can get me out of the deepest depression!” Janna Degener-Storr

Bernard Chan will become the new President of Museum M+ in Hong Kong. Chan is a member of the city’s Executive Council and thus one of the closest advisors to Chief Executive Carrie Lam. He will take up his post on April 1, succeeding Victor Lo, who is retiring after six years. Chan is currently also president of the Palace Museum, but will step down from this post toward the end of the year.

Julia Hu has been appointed the new Managing Director Asia of the British art auction house Bonhams, based in Hong Kong, in mid-March. Hu moved from competitor Christie’s, for which she had headed the China business for nine years. Under Hu’s leadership, Christie’s sales in China had grown considerably, both its auction segment and private sales.

Huaqing Innovation, a company from Shenzhen, is presenting this mini-drone at a defense trade exhibition in Malaysia. The “Kolibri” (蜂鸟) is designed to compete with its Norwegian model “Black Nano Hornet”. This tiny military device is 17 centimeters long and weighs 35 grams. It is intended to sneak undetected behind enemy lines and send images from there.

Low-priced competition from the Far East has already been the downfall of several German industries. Televisions, cameras, solar cells, raw materials for antibiotics, toys. This pattern is so deeply rooted that fears about it quickly flare up. Now, the Chinese government is ramping up its subsidy machinery to pave the way to the EU for its own wind turbine manufacturers. Lush profits beckon in Europe. After all, the huge undertaking of breaking away from geopolitically and climate-politically damaging energy sources is in motion. But all is not lost for companies like Vestas and Gamesa, analyzes Nico Beckert. A 100-meter-long rotor for a wind turbine cannot simply be packed into a container like a solar cell.

China’s tough regulation of Internet companies (the “tech crackdown”) is also perceived as something rather sinister in the West. Isn’t the CP consolidating its power in this way? In fact, the motivations are very similar to those of Western regulators, for whom the power of individual companies goes too far. One example last year was Tencent, whose music streaming division has created a monopoly. Frank Sieren has taken a look at the impact of the breakup of the cartel of Tencent subsidiaries. As a result, there are now more pieces of the pie for everyone: Competitors have breathing room – and even for Tencent, things didn’t go as badly as feared.

Last year, Huawei made more profit than ever before. At first glance, this comes as a surprise. After all, US sanctions had brought the company’s smartphone division to its knees. But Huawei is not just a provider of electronics for end customers. You will find all background information on this surprising profit surge in our analysis.

The lockdown of Shanghai is also a topic today. DHL has suspended cargo operations at its Pudong hub. All citizens have to be tested twice. Only China is able to keep 26 million inhabitants of a bustling metropolis in their homes.

The European Union wants to expand renewable energies faster as a result of the Russian war in Ukraine. And wind power plays a major role. By 2030, 480 gigawatts of wind capacity are to be connected to the grid. Before the Ukraine shock, only 450 gigawatts were projected. The 2030 target has thus been increased by an additional 30 gigawatts.

So these are golden times for the European wind power industry – one might think. But the competition from China is pushing stronger on the global market and could profit from Europe’s wind power expansion. The European industry is therefore already warning of a loss of market share. However, a repeated disaster like the complete elimination of the German solar industry by overwhelming competitors from the Far East is not to be expected.

China’s wind industry has grown rapidly in recent years. Half of the wind turbine components manufactured worldwide are produced in China. Six of the ten largest manufacturers come from the People’s Republic. Since 2019, Europe’s annual imports of wind turbines from China have almost doubled from €211 million to €411 million last year. European competitors are faltering at the same time. Four of five European manufacturers reported losses last year. As a result, they are closing factories and cutting jobs. In Germany alone, more than 50,000 jobs have been lost in the wind industry over the past six years, according to industry data.

All signs point to the same fate for the European wind industry as for the solar industry. But this conclusion is premature. With Vestas and Siemens Gamesa, two of the world’s five largest wind companies are from Europe. And despite rising imports, China’s position has yet to gain a strong foothold in Europe. The majority of China’s huge production capacity is used for the People’s Republic’s own massive expansion of wind power. But it is precisely this massive expansion that is scaring Europe’s wind industry. A strong foundation at home also allows for international expansion. Chinese suppliers compete with unbeatable prices and have also caught up technologically.

Its large domestic market favors Chinese suppliers. “The sheer scale of its manufacturing capacity affords China a major competitive advantage” in the wind energy market, says Xiaoyang Li of research and consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. Industry representatives in Germany are also viewing the developments with concern. “In the largely closed-off but high-volume Chinese market, Chinese manufacturers have come close to European performance levels from a technological perspective,” says Wolfram Axthelm, Managing Director of the German WindEnergy Association. “We have seen in the past how Chinese companies penetrate new markets with government assistance.”

The situation in Europe is quite the opposite, according to the industry association Windeurope. “The small size of the market is really hurting the supply chain,” says an open letter from the association to EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. “The problem is not government ambition on climate action and renewables,” writes Christoph Zipf of Windeurope. “Europe is simply not permitting anything like the volumes that you and the national governments want to build.” As a result, the energy transition is being delayed.

Because demand in Europe is not sufficient, the sector is at a disadvantage against China. On the global market, the European industry is already losing market share to China. And Chinese suppliers are increasingly securing contracts to build wind farms in Europe – for example, in Italy, France, Croatia, and Serbia, the association writes.

A decision made by China’s Ministry of Finance could further widen the imbalances. The ministry recently allocated $63-billion to pay out promised subsidies more quickly. Most of the money will go to wind and solar power plant developers, Bloomberg reports. Subsidy debts had piled up in recent years as renewable energy expanded faster than the government could hand out the subsidy money. The payment arrears had affected the entire supply chain, according to an industry insider. The release of the funds would now give the industry a boost.

While Chinese companies are strengthening their competitiveness, European companies are losing market share in the People’s Republic. In 2021, construction projects by foreign wind turbine manufacturers have halved. Foreign companies’ costs for onshore turbines in China are nearly twice as high as those of domestic suppliers. Prices for Chinese wind turbines fell 24 percent in 2021, according to Wood Mackenzie. In 2022, they will drop by another 20 percent, the research and consulting firm predicts. In addition, there are regulations that “largely close off” the market to foreign companies, Axthelm says.

The increase in competitiveness favors the global expansion of Chinese suppliers. Wood Mackenzie analysts conclude that Chinese companies have so far focused on the domestic market, but are likely to compete more strongly on the global market in the coming years as they have been able to lower their prices, while European and US manufacturers are struggling with rising material costs.

Will wind turbine manufacturing relocate from Europe to China? That is unlikely. After all, the wind industry is very different from the solar industry. Solar module manufacturers manufacture a mass product that can easily be transported halfway around the globe. The wind industry is much more complex. Turbines include up to 8,000 components, writes Ilaria Mazzocco. “Wind turbine manufacturers are usually also directly involved in maintenance and installation,” says the China energy expert from the Center for Strategic & International Studies. Turbine manufacturers often maintain a local presence.

This is why some Chinese suppliers are also planning to set up production facilities in Europe. European manufacturers are taking this new competition seriously. Mazzocco believes it is unlikely that Chinese suppliers will completely push out other leading companies and existing supply chains. Regulations on local value creation also suggest otherwise.

Bloomberg NEF estimates that these regulations will become more important in the future and that “qualitative criteria” will play a greater role in awarding contracts. Price could therefore lose significance as a decisive factor. This is also supported by new EU guidelines for government aid for climate, environmental protection, and energy. They allow governments to place greater focus on other criteria, such as local value creation when awarding contracts.

Almost a year ago, Tencent already felt the new power of China’s antitrust authorities. Since then, the tech giant from Shenzhen in southern China, which owns several successful streaming services like Tencent Music, is no longer allowed to sign exclusive music licensing agreements for China with global record labels like Warner or Universal. The ban follows a decree by China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), which wants to prevent Tencent Music from further expanding its monopoly in the music industry.

Tencent Music Entertainment Group (TME), which began trading in New York in December 2018, operates three popular streaming platforms in China, QQ Music, KuGou Music and Kuwo Music. Together, these three platforms have a 71 percent market share in China. That is too much even by Western cartel standards. Therefore, Beijing has imposed strict new regulations: exclusive music licensing agreements had to be terminated within 30 days.

As a result, Tencent channels lost permission, for example, to market music by Jay Chou, probably Asia’s biggest pop star, exclusively in China. The Taiwanese singer and rapper has sold more than 30 million records in the past 20 years. That is only about 20 percent of what US rapper Kanye West has sold in the same period, but for Asia, this is still a remarkable number.

Tencent Music is no longer able to acquire the exclusive rights to the catalogs of Universal Music Group, Sony Music or Warner Music Group and then sell them to smaller platforms such as NetEase, Alibaba and Xiaomi. The stock market reacted swiftly: Within a year, the share price plunged by more than 80 percent, like all tech stocks that are affected by the wave of new antitrust laws with which antitrust authorities want to revive the market economy.

Now, almost exactly one year later, the consequences of the new policy are starting to show. The business collapse that investors feared has failed to materialize. The government intervention has not destroyed Tencent Music’s business model, and at the same time has given competitors more room to grow. This means that the industry as a whole continues to grow, and Tencent is benefiting from this. But the competition has more breathing room.

The number of paying Tencent users grew by more than 36 percent to over 76 million in 2021, despite antitrust regulations. Revenue grew by 7.2 percent to the equivalent of $4.9 billion, Tencent reported. The online music service even grew by more than 22 percent. Subscriptions by 33 percent. Tencent saw this overall increase even though it suffered a 7.6 percent drop in revenue last quarter. This was mainly the result of Covid-related lower revenues from clubbing and live streaming.

The crackdown has thus primarily sent Tencent’s share price plummeting, and it has yet to recover. The government has already taken appropriate measures (China.Table reported) and the share price has risen. But those who got in on Tencent Music’s 2018 IPO still lost more than half their investment.

In part, however, the lower valuation is justified. After all, the biggest winners of the reforms are the other 15 different audio streaming services with at least one million daily active users, which previously only had to compete for a market share of 30 percent and will now be able to massively expand.

NetEase is a prime example of how the new policy is already taking effect. NetEase Cloud Music is Tecent’s biggest competitor. In 2021, its revenues grew by nearly 43 percent, six times faster than top dog Tencent. The platform, founded in 2013, had 181 million monthly active users and a library of about 60 million tracks as of December last year.

Thanks to regulations, NetEase can better utilize its unique selling proposition against Tencent. Namely, its comment function, a very own social media feature. Around 25 percent of NetEase users comment below songs and artist pages, while 61 percent of users actively follow these comments. That’s a lot more than on Tencent.

Because many users not only listen to the music but also pour out their hearts in the process, NetEase is also known as the “streaming club of lonely hearts” among Chinese Internet users. In response, NetEase has even set up a “Healing Center” where listeners can find emotional support. The price models of Tencent and NetEase also differ. The annual subscription for NetEase Music costs the equivalent of about $26, which is slightly more than its competitor Tencent Music.

For years, NetEase Music executives had complained that they had to pay “two to three times the reasonable cost” for content under a sublicensing agreement with Tencent Music. Intervention by the National Copyright Administration (NCA) back in 2018 led to an agreement between the two companies to share up to 99 percent of their music content. However, the agreement turned out to be a sham. The remaining one percent included the most popular and top-selling artists. That is now over.

What is also politically interesting is that Chinese antitrust authorities were not bothered by Tencent Music’s international influence. In late 2017, Spotify and Tencent Music agreed to exchange shares between them. Spotify received a 9 percent stake in Tencent Music Entertainment Group, while Tencent also received a 9 percent stake in Spotify via two companies.

As a result, Spotify was profitable for the first time. Critics consider the mutual stake between the biggest player in China and the biggest player in the world to be a kind of cartel. Tencent has also owned ten percent of the American Universal Music Group since 2019. A year later, Tencent bought 5.2 percent of Warner Music Group. This means that the Chinese have a stake in the two leading US music and entertainment labels. Political decoupling pressure is not being felt in this sector, neither from Washington nor from Beijing.

The market prospects for China’s big players are promising. In the past ten years, the number of music streaming subscribers has increased by 80 percent. With the rise in the share of the middle class in the total population, this trend is expected to continue. Currently, there are still under 100 million subscribers. Only at 300 million, China would have the same ratio per capita as the USA.

It was the first major appearance of the daughter of Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei since September 2021, when Meng Wangzhou was released after three years of house arrest in Canada and returned to her home country amid huge media coverage. On Monday afternoon, she presented the annual report of the network equipment provider from Shenzhen in southern China as CFO.

Her appearance felt like a bold and defiant message to Canada and the United States. US courts had accused her of undermining sanctions against Iran. In return, China had detained two Canadian citizens for three years and charged them with rather vague charges of espionage. Shortly after Meng’s release for lack of evidence, the Canadians were also released.

Now Meng is back in business and presented surprisingly good financial figures. With a revenue of around $100 billion, Huawei achieved a remarkable profit margin of over 17 percent: $17.8 billion. And this is even though sales dropped significantly – by a whopping 29 percent – in what were politically challenging times for the company.

Meng cited several reasons for the revenue decline. US restrictions on the company hampered growth due to a lack of supplier parts. Added to this was the pressure from the pandemic. But there were also company-specific reasons. Most importantly: The collapse of the smartphone business – because the upgrade to 5G had been completed in China, demand had temporarily dropped in this sector.

The profit margin is all the more surprising because the share for R&D has also climbed by more than 22 percent to a good $22 billion. These investments cannot be monetized for at least a few years – if at all. Huawei’s CEO Guo Ping emphasized that the company also intends to further expand its R&D investments: “It makes a lot of economic sense to open up new technology areas instead of expanding old ones, even if the expense is high.”

CFO Meng, therefore, noted that “we are increasingly successful in dealing with uncertainties.” This was also reflected in the financial liabilities. Profits had not been generated on excessive debt, as is often the case in China. On the contrary, the debt to equity ratio was reduced to 57.8 percent.

Two factors are likely to have helped the bottom line. Huawei is not a state-owned company, even though it is said to maintain close ties to the state and the Party given its strategic importance. Moreover, it is not listed on the stock exchange. That is why the company is not pressured by quarterly figures or direct political influence. Management can afford to take its time in research and development.

CEO Guo identifies the search for new talent, scientific research, and the spirit of unity as the most important development goals. Huawei would rather break new technological ground than make a quick buck with small improvements to existing technology. A year ago, for example, the company managed to surprise the world with a complete system for autonomous driving. At a time when the smartphone division had collapsed due to US sanctions and Huawei had lost its position as the global market leader.

This strategy is a risky one because R&D does not automatically result in a breakthrough. To minimize the risks, Huawei does not place all its eggs in one basket, but conducts research in many different areas simultaneously. In this way, the company also achieved lucrative growth in smart wearables and smart screens, each of which grew by more than 30 percent year-on-year.

On the other hand, it was impossible to predict that Huawei’s smartphone operating system would not be of any international significance due to US sanctions. Having learned an important lesson, Meng also remains vague about the future direction of the company, leaving it at three keywords: digital transformation, artificial intelligence, and technology to reduce global carbon emissions. Frank Sieren

Standing in line for mass tests and take-out meals only: Shanghai’s 26 million citizens are coming to terms with the state of emergency. Starting Monday, the city government had surprisingly ordered a lockdown to stop the spread of Sars-CoV-2. After Omicron gained a foothold in the densely populated metropolis, concerns grew that the city could suffer a similar fate to Hong Kong. On Sunday alone, 3450 asymptomatic Covid cases were reported in Shanghai. Public life is being shut down in two stages until April 5 due to the rising number of new Covid infections. Bridges and tunnels have already been closed and highway traffic restricted.

Public transportation, such as subways and buses, have also stopped operating since Sunday evening. Apartment blocks have been cordoned off with yellow plastic walls. Police are urging citizens to comply with the regulations. A curfew is in effect for large parts of the city. Employees of most companies are only allowed to work from home.

Meanwhile, long queues have formed at testing centers. Every citizen is to be tested twice to detect infections in the population. “The Shanghai outbreak is characterized by regional clusters and infections spread across the city,” said Wu Fan of the city government’s pandemic task force. But the abruptly imposed lockdown has also led to problems. Delivery services are overwhelmed by the many orders, companies are without employees.

Many supermarket shelves are empty: Shortly before the start of the lockdown in Shanghai, many residents of the metropolis took advantage of the last chance before isolation to stock up on supplies. The lockdown is supposed to be limited to a few days. But the shopping frenzy of citizens indicates that they do not really trust the announcement and are preparing for a longer lockdown.

The lockdown may also affect more than 2,100 German companies that are operating there, according to the German Chamber of Commerce Abroad. ThyssenKrupp, for example, operates a local plant that manufactures steering systems and dampers for the automotive industry. Production will be continued, the company stated. The plant employs several hundred people.

Meanwhile, Deutsche Post has temporarily shut down its major air cargo hub at Pudong Airport. According to a company spokeswoman, this hub is one of four transshipment hubs in the DHL network in the region, with others in Hong Kong, Tokyo and Singapore. The company promised to keep its logistics customers informed about further developments.

German business fears that the Covid lockdown will primarily cause problems for already strained supply chains. “The mood among German businessmen is noticeably gloomy thanks to the new lockdown and already dampened growth expectations,” Volker Treier, Head of Foreign Trade at the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce (DIHK), told Reuters.

For now, however, the port of Shanghai is operating as usual. “This could limit damage to global supply chains,” said trade expert Vincent Stamer of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). “Problems in transporting goods to the port, however, could also manifest as longer shipping times of goods. fin/rtr/grz

China’s largest listed coal company, Shenhua Energy Co., wants to focus more on clean energy in the future. To this end, Shenhua wants to divert at least 40 percent of its annual investments into renewables until 2030.

Last year, Shenhua had invested just 0.08 percent of its spending on renewable energy. The company is part of the state-owned China Energy Investment Corp. which was the largest coal mining company in 2021, producing 570 million tons of coal. According to company data, Shenhua produced 177 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions from burning coal during the same period.

The Chinese government is expanding renewable energy capacity to peak CO2 emissions by 2030 at the latest. Despite the rapid growth of renewables, however, China remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels, with more than half of its power generated by coal-fired power plants.

Beijing recently announced plans to build five new coal-fired power plants (China.Table reported) and to increase the supply of coal. The decision was partly due to a widespread power shortage in the country in the fall of last year, when numerous companies and private households had to massively restrict their consumption.

By the same token, state-owned China Energy Investment is also the world’s second-largest renewable energy developer, with more than 41 gigawatts of power generation projects, according to data compiled by BloombergNEF. Most of its renewable projects to date have been through Longyuan Power Group Corp, another listed subsidiary. niw

The influx of disinformation from China to Europe has increased significantly in the past year. This is according to the 2021 activity report of the Strategic Communication Task Forces and Information Analysis Division. It is part of the European External Action Service (EEAS) and identifies foreign disinformation, lies and influence from abroad.

Above all, disinformation in connection with COVID-19 has increased. In many cases, their origin could be traced back to agencies “directly or indirectly linked to Chinese authorities.” Chinese officials and state-controlled media have spread allegations “that sow doubts about the origin of the virus and the safety of Western vaccines”.

Moreover, China had “promoted the underlying message that its own system of government is a better alternative to Western democracies” In the process, “there have been occasional alignments with and amplification of pro-Kremlin conspiracy narratives“ by Chinese actors. This trend has also been evident recently in the Ukraine war, the StratCom report said.

The manner of disinformation from the People’s Republic was often characterized by “harsh messaging through official channels.” There have also been attempts to silence critical voices or spread positive narratives about China via influencers. Especially in the Western Balkans, China has an increasing influence on media and social networks.

Most recently, the EU Parliament had called for tougher action against disinformation campaigns and foreign influence (China.Table reported). ari

Joern-Carsten Gottwald is mindful about what he says publicly about China. He is a member of the advisory board of Merics (Mercator Institute for China Studies), which has been placed on the Chinese government’s sanctions list. He is not interested in jeopardizing his partnerships.

As a professor of East Asian politics, the 51-year-old primarily focuses on bilateral relations between Europe and China. “We are actually on the way from a strategic partnership to a triad,” he says, picking up on a phrase that describes the complicated, since contradictory, relationship as partner, competitor and rival. This applies to many important issues: China, for instance, is a partner in global climate protection, a competitor in global markets, and a country that increasingly imposes alternative norms and values in international politics and challenges established democracies – like Germany.

As a scientist, Joern-Carsten Gottwald sees his task as bringing objectivity to this area of conflict. He also wants to show his students how important this is, especially in times of propaganda and fake news. “There has been an incredible change of sentiment in relations between China and the EU,” he says. In the 2000s and 2010s, there had been a China euphoria, which was naïve in many ways. And now, the threat posed by China is being exaggerated in many ways. “It’s important to maintain a certain sobriety in science, that is, not to be carried away by moods and currents in one direction or the other.”

His research involves, on the one hand, Chinese documents, which he tracks down, sifts through, evaluates, and then supplements with expert interviews. Normally, he also travels regularly to China to speak with as many stakeholders and decision-makers as possible. The latter has now become difficult – for political reasons and also because of the Covid pandemic, which makes cooperation with Chinese experts more difficult: Maintaining personal contacts now happens almost entirely virtual due to travel restrictions.

Online communication, for its part, brings its own problems, because platforms like Zoom are not one hundred percent safe. “I experience a certain caution about holding professional conversations with colleagues online or asking questions. The reason for this is the censorship of platforms and the stronger role of ideology in research in the People’s Republic of China,” explains the expert.

Academic teaching is also affected by these difficulties. Not just since a hacker attack on his university in May 2020 has Joern-Carsten Gottwald carefully pondered how he can protect his students from their statements being used against them during online events. Another problem is that fewer international students are now able to study in Bochum. And for German students, studying abroad in the region is mandatory per university regulations. They cannot be substituted by Zoom.

This is something that Joern-Carsten Gottwald knows from first-hand experience, of course. He stayed in Shanghai in 2013 and in Taiwan in 2019 as a visiting scholar, accompanied by his wife and children, who are now 16 and 18 years old. Personal interactions were also the reason that brought him to East Asia in the first place back in the 1990s: “I had already read a lot during my A-levels and then met a person who had studied Sinology. I particularly enjoyed Chinese philosophy,” he recalls. In the thirty years that have passed since then, his fascination with China has experienced some highs and lows. What never changed during that time, however, was his enthusiasm for Chinese food, the professor recounts with a wink: “Any kind of jiaozi can get me out of the deepest depression!” Janna Degener-Storr

Bernard Chan will become the new President of Museum M+ in Hong Kong. Chan is a member of the city’s Executive Council and thus one of the closest advisors to Chief Executive Carrie Lam. He will take up his post on April 1, succeeding Victor Lo, who is retiring after six years. Chan is currently also president of the Palace Museum, but will step down from this post toward the end of the year.

Julia Hu has been appointed the new Managing Director Asia of the British art auction house Bonhams, based in Hong Kong, in mid-March. Hu moved from competitor Christie’s, for which she had headed the China business for nine years. Under Hu’s leadership, Christie’s sales in China had grown considerably, both its auction segment and private sales.

Huaqing Innovation, a company from Shenzhen, is presenting this mini-drone at a defense trade exhibition in Malaysia. The “Kolibri” (蜂鸟) is designed to compete with its Norwegian model “Black Nano Hornet”. This tiny military device is 17 centimeters long and weighs 35 grams. It is intended to sneak undetected behind enemy lines and send images from there.