Xi Jinping’s guiding idea for China is that of a future of “common prosperity”. However, in times of sluggish economic growth and high unemployment, many Chinese no longer believe in this Chinese dream, which states that everyone can make it. On the contrary, many fear slipping down the social ladder.

Margaret Hillenbrand, a professor at the University of Oxford, has written a book about the new precariat in China. This includes migrant workers as well as university graduates who cannot find a job. They no longer feel picked up by promises of a “harmonious society”, she says in an interview with Amelie Richter. Hillenbrand also describes how a kind of “zombie citizenship” is slowly emerging, consisting of people whose ability to speak, think, or act independently is denied from above.

Foreign companies also have a responsibility when it comes to protecting people from oppression and exclusion. Companies that have been active in the Xinjiang region, affected by forced labor, have been particularly scrutinized for a long time.

VW was able to breathe a sigh of relief after the publication of a special audit of its plant in Xinjiang. No visible evidence of forced labor was found, and the company’s stock rose. However, the findings of the inspectors paint a mixed picture, writes Finn Mayer-Kuckuk. VW must continue to conduct audits and establish a functioning complaint management system to maintain the trust of investors in the long term. Social standards in the supply chain are becoming increasingly important worldwide.

Professor Hillenbrand, you are writing about precarity in China. Can you give us a short overview of your book?

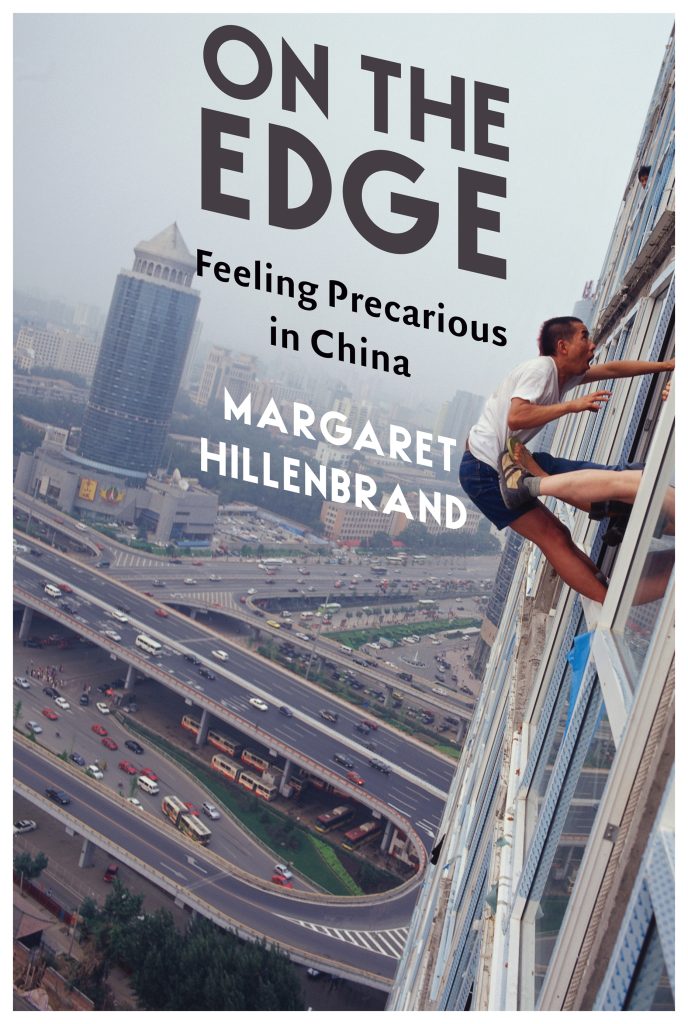

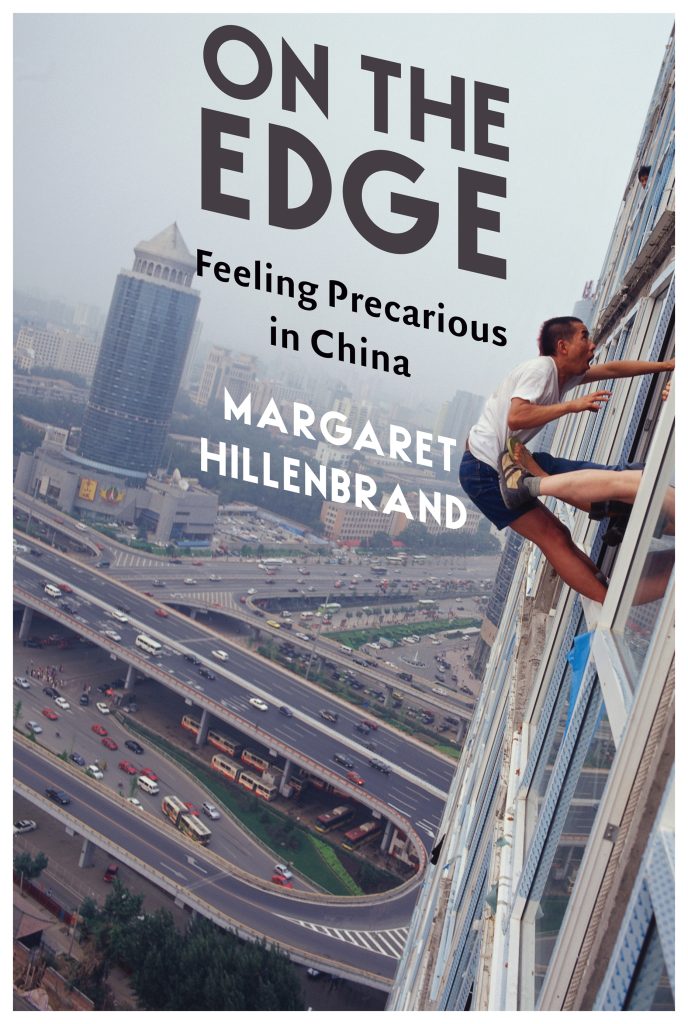

The key question that I’m trying to ask in the book is: What does it mean to feel precarious in 21st-century China? Since the millennium, precarity has been a crucial keyword of our times – and its traction as a term only intensified after the 2008 financial crash. But despite the fact that China was and is prime precarious, “precarity” just wasn’t a conceptual framework that people were using in connection with Chinese society at all until quite recently, and especially not in relation to cultural forms.

So what are we looking at exactly?

To understand what precarity feels like in China, we have to get grips with what it means to have an underclass between 300 and 400 million people strong – the largest such cohort in human history. The term precarity has typically been linked to disposability, casualization, inequality, workfare rather than welfare. But China’s underclass has endured much worse. They’ve borne the brunt of the unequal hukou system and the prejudicial suzhi regime, modes of governmental control that are fundamentally rooted in social segregation – so much so that I think these underclass experiences are better understood in terms of expulsion, even banishment. In the book, I try to develop a set of conceptual tools for thinking about this pathway from precarity to expulsion, with a particular focus on cultural practices.

The living situation of migrant workers can be called precarious and by now is quite well known. What does precarity mean beyond the migrant workers?

Examples of other social groups who are experiencing precarity right now include elite university graduates who can’t get their first job; IT employees who are caught in China’s 966 working culture (966工作制); and delivery workers in the country’s platform industries who are discovering that even the so-called flexibility of the gig economy is becoming illusory because they’re trapped by algorithms that mandate very harsh working conditions. But there are also bleaker examples further down the path to banishment (some of whom do include migrant workers): people who’ve experienced forced eviction; people who endure a hard grind yet have their wages denied, especially in the construction industry; people who are forced by high rental prices to live in shipping containers and disused defence shelters. These are also people who are experiencing precarity, even expulsion, in China right now.

In the book, you are introducing the term of “zombie citizenship”. What does that mean?

It’s a state of abject exile from the shelter of the law, in which a very substantial minority of Chinese people currently languish, even though they theoretically enjoy full, even privileged personhood under the law of the land. If you look at Article 1 of the Chinese Constitution, it states clearly that the People’s Republic of China is a socialist state under the people’s democratic dictatorship led by the working class and based on the alliance of workers and peasants. I felt that the term “zombie citizenship” was necessary because it captures the sense in which many working people in China are chained by toil yet simultaneously cut loose from the safeguards of the law – despite what that law articulates in black and white.

So, these people are alive, they exist on paper, but they do not experience full citizenship because of their situation without basic rights or a city hukou?

Yes. I should say, though, that I don’t use the term “zombie” to describe people. It’s a provocative, even inflammatory word: zombies are creatures raised from the grave, with no power of speech, thought, independent deed. So I use the term “zombie citizenship” instead to describe the state of civic half-life into which some people are pitched in our current precarious moment. What’s more, the fear of tumbling into zombie citizenship doesn’t just menace the underclass; it also afflicts those who at first sight seem far more secure. This terror of a life without core rights looms like a precipice, and the notion of the cliff edge is the second conceptual tool I use in the book.

You are also connecting culture to precarity. How are those two combined, especially now in the world digital age?

In the book, I argue that this fear of downward mobility has brewed social strife during the first two decades of this century up to the pandemic – and that culture is where this tension breaks cover. I look at a wide range of artistic forms through which people who are living on the edge vent their feelings of dread and distrust, contempt and fury. These are dark feelings which are basically taboo in China’s so-called “harmonious society”, in which “positive energy” is supposed to be the dominant affective tone. I looked at various materials for the book: poetry, migrant worker magazines, social media posts, short online videos, performance art, documentary film, installations, interviews, and so on. And as I dug deeper into this archive, I found again and again that these dark feelings are always very personal; they’re highly antagonistic.

What does that look like?

There’s always some kind of hostile stand-off going on here: between avant-garde artists and the desperate migrants they recruit for humiliating performance pieces; between unpaid construction workers threatening on camera to jump from a rooftop and their immoral bosses on the street below; between poets on the Foxconn factory floor and the multinationals who enforce sweatshop conditions; between users of a livestreaming app who eat excrement or set off firecrackers on their genitals and their so-called social betters who lecture them for being vulgar. These encounters are tense and abrasive. But in a society where active solidarity is often blocked, these moments of antagonism can also be another way of creating vital points of contact between people.

Did the pandemic accelerate precarity in China?

For people who were already marginalized, Covid tended to intensify that marginality. A key example is delivery drivers. They were the workers who were actually going out into deserted cities to make essential deliveries; yet they were often stigmatized as potential carriers of the virus. In other words, they were socially punished for performing a crucial public service, and their precarity, which was already quite intense before the outbreak, was further amplified under pandemic conditions.

But even people who were ostensibly much more secure sometimes saw a peremptory withdrawal of rights. A telling example of this occurred during the Shanghai lockdown of 2022. Shanghai is a beacon city full of elite professionals; but many of these people found themselves essentially incarcerated in their homes, unable to access freedoms that they’d previously taken for granted. They suddenly realised that their grip on basic rights was perhaps just as tenuous as those lower down the social ladder.

In the last five-year-plan, the CCP already announced that they want to make changes in the hukou system. Would that be an effective remedy against precarity?

There have been a lot of high-profile statements in the last few years which finally seem to promise the end of hukou-based social apartheid. On one level, these changes seem inevitable, since Xi Jinping’s flagship policy of “common prosperity” is fundamentally incompatible with the continuation of hukou. But quite a few of these policy initiatives have only really scratched the surface. In particular, decision-making about hukouremains too devolved and decentralized, with the result that these shifts don’t tackle the problem of hukou restrictions in top-tier mega-cities, which are still the destinations of choice for many rural migrants. That’s why there’s a lot of scepticism in the media, both inside and outside China, about whether these reforms to the hukou system will go deep and wide enough. And some commentators even argue that control over space in China’s cities is actually tightening through tough policies around grid governance, demolition, and eviction.

Margaret Hillenbrand is Professor of Modern Chinese Literature and Culture at the University of Oxford. Her research focusses on literary and visual studies in 20th– and 21st-century China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Japan, especially cultures of protest and secrecy. Her books include Negative Exposures: Knowing What Not to Know in Contemporary China (Duke University Press, 2020) and On the Edge: Feeling Precarious in China (Columbia University Press, 2023).

The results of a special audit of the Volkswagen plant in the Chinese region of Xinjiang have tipped the scale: Union Investment, the fund company, continues to categorize VW shares as “investable” for sustainable investments. “The publication of the audit is a step in the right direction,” says Henrik Pontzen, Head of Sustainability in Portfolio Management at Union Investment, to Table.Media. However, VW must conduct additional audits in the long term and establish a functioning complaint management system to gain the trust of investors.

The day after the inspectors’ findings were published, a mixed picture emerges:

Nevertheless, the independent auditors could only conduct their investigation at the Ürümqi plant. The overall context in the Xinjiang region is difficult to fathom due to the opacity of the Chinese system. The potential supply chain risks in China are, therefore, not yet over for VW.

Since 2012, VW has been operating a factory in Ürümqi in western China, which is controversial due to its proximity to systematic human rights violations against the Uyghur people. The consulting firm Loening – Human Rights & Responsible Business examined the conditions in the factory and found no abnormalities.

The former human rights commissioner of the German government, Markus Löning, founded this company ten years ago. Loening and his company have a good reputation. However, Loening himself emphasized when presenting the report: “The situation in China and Xinjiang and the challenges of data collection for audits are known.” His team primarily looked for violations of labor regulations among the 197 employees on-site. “We could not find any evidence or proof of forced labor among the employees,” says Loening.

Much depended on Loening’s judgment for VW. The classification as a sustainable investment by companies like Union Investment is important for Volkswagen’s financing capability. Competing company Deka Investment has already withdrawn from the stock. Companies like Volkswagen rely on such major investors to raise capital.

However, according to Union Investment, VW is not yet where it needs to be; there is still much to do. “In China, audits must not be a one-time exercise,” says Pontzen. “In addition, a functioning complaint management system must be established.” The “weak corporate governance” at VW also remains an Achilles’ heel. Corporate governance refers to good corporate management.

Despite the theoretical decision to be able to include VW shares in funds labeled as sustainable, this is currently not the case for any product at Union Investment. The securities firm is thus delaying the practical consequence of the classification as “investable”. “We will continue to critically accompany VW as an active shareholder,” announced Pontzen.

Union Investment distinguishes between investability according to Article 8 and Article 9 of the EU plan for sustainable finance (the so-called disclosure regulation):

The umbrella organization Critical Shareholders (DKA), which represents small investors in environmental, social, and governance issues, also expressed skepticism. Unlike Union Investment, DKA generally questions the value of such inspections. Considering the limited scope of the investigation, the value of future audits is questionable, said DKA Managing Director Tilman Massa to the Reuters news agency.

Companies involved in China’s business, like professional shareholders, are aware that attention to social standards in the supply chain is increasing. The collapse of the Rana Plaza textile factory in Bangladesh is considered a turning point in perception; since then, the happenings in the supply chain have become a criterion for the selection of stocks for an increasing number of funds.

The next major milestone will be the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Act, if and when it comes. It focuses on environmental, human rights, and social issues in suppliers. Unlike the German Supply Chain Act, it not only obliges consideration of direct business partners but the entire supply chain. This is likely to be very complex for the Chinese industry.

According to a report by the Italian newspaper Corriere della Serra on Wednesday, the Italian government has officially informed China about the end of its participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Rome reportedly confirmed the formal withdrawal from the BRI to Beijing in a verbal note at the beginning of the week. However, both sides intend to revive the strategic partnership that has existed between Italy and China for more than ten years, though it was never fully implemented, according to the report, citing the letter. There has been no official announcement from either Italy or China on this matter.

In 2019, Italy became the first and only G7 nation to formally join the BRI. The then-Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte and Chinese President Xi Jinping signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with great pomp and ceremony at Villa Madama. However, the MoU fell short of expectations in reality. The cooperation agreement is set to expire in March 2024. Therefore, Rome had to make a decision by the end of the year.

The formal withdrawal of EU member Italy will not be a topic for the EU-China summit taking place on Thursday in Beijing. It has been clear for some time that Rome intended to leave the BRI. According to journalist and China expert Giulia Pompili, Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni “decided in every way for a smooth exit from the Silk Road”. Pompili added that Meloni wanted to avoid a strong anti-China stance upsetting Beijing on the 10th anniversary of the start of the strategic project. However, the timing is politically interesting: Italy had until Dec. 22 to announce its withdrawal. According to Pompili, the fact that Rome took this step just a few days before the summit can also be seen as a message of support to EU representatives. ari

In politics and business, there is much talk about de-risking in dealing with China. However, apparently, little has been done. According to the German Institute for Economic Research (IW), German companies are not doing enough to reduce their one-sided dependencies on China. “De-risking has started, but we must not be under any illusions: too little is happening, even though time is of the essence,” said IW trade expert Juergen Matthes on Wednesday, according to the AFP news agency. Many companies are even increasing their imports from the People’s Republic instead of reducing them.

The IW study shows that out of 400 surveyed companies in North Rhine-Westphalia alone, 40 percent are dependent on products from China. About one-third of them expect that this dependence will not change in the future, and 48 percent even anticipate a growing importance of China.

It is actually the responsibility of companies to reduce critical dependencies, the IW told AFP. However, due to state subsidies, the Chinese industry remains a good and cheap trading partner. If companies want to remain competitive, they must partner with China. “There is a kind of market failure here,” said Matthes. From an overall economic and geostrategic perspective, it is urgently necessary to reduce dependencies.

If the companies’ attitude does not change soon, politics should create further incentives to reduce critical dependencies, Matthes demanded. flee

Germany and Taiwan are set to engage in closer civil society exchanges, according to the German foreign office. The German Institute Taipei and the Taipei Representation in Berlin plan to establish a new German-Taiwanese dialogue platform, as announced by the foreign office on Wednesday. The platform’s goal is to “promote vibrant civil society exchange, particularly in light of increased bilateral economic contacts”. The dialogue platform is expected to have twelve members on each side and will meet annually, alternating between Germany and Taiwan. Green Party European policy politician Reinhard Buetikofer will chair the German side. The platform’s work is expected to commence next year. ari

China’s automotive market showed growth again in November. According to the China Passenger Car Association (PCA), 2.06 million vehicles were delivered to customers last month, an increase of about a quarter compared to a year ago.

However, lockdowns in numerous Chinese regions contributed to a decline in demand for cars a year ago. Sales in November increased by one percent compared to October.

EVs continue to advance, with almost every third car sold being fully electric or plug-in hybrid. This represents almost a third more than a year ago, according to the information. flee

Prada aims to double its business in China, according to Gianfranco D’Attis, the CEO of the Italian brand, speaking to reporters in Shanghai. “We have many ambitions in China,” said the former Dior manager who took over at Prada in January. “This is also accompanied by an increase in our investments.”

D’Attis did not provide an exact timeframe for his plan but stated that the increased investments would not necessarily mean a significant increase in the number of stores opened in the country. “Not only is the number of stores important to us, but also the quality of the stores, larger stores with more categories, more localized products, more experiences, more hospitality, more events,” he said.

The Prada Group, which includes the classic English shoe manufacturer Church’s among its brands, reported a 10 percent increase in revenue for the third quarter in November, stating that strong sales in Asia and Europe helped offset weakness in North and South America. China is one of the world’s most important luxury markets. According to consulting firm Bain’s forecasts, China is expected to account for nearly 40 percent of global luxury sales by 2030. rtr

Leonie Suna-Kiefer first heard the Chinese language from tourists in her small hometown on Lake Constance. Even as a child, she was fascinated by Mandarin. After graduating from high school in 2012, she traveled to Thailand, Laos and finally to China. “I was intimidated, fascinated and full of curiosity about the unknown,” she recalls.

She also realized that her Germany-influenced perception of China did not align with what she experienced there. “I became aware that I had come to China with a certain arrogance, only to find that the country had developed in a completely different way and, from a technological perspective, was surpassing Germany.” Instead of bicycles, only electric scooters were seen on the streets of Chinese megacities.

Back in Germany, her interest was piqued – “and a certain ambition to master this seemingly unlearnable language”. In Cologne, she studied Chinese regional studies and wrote her master’s thesis on the Chinese Social Credit System. “It was important for me to open up a new perspective on the Social Credit System, to show how it is reported in Chinese media, and what role the system actually plays in people’s daily lives.”

Another focus was on developments in Chinese climate policy, which Suna-Kiefer continues to follow closely. During her studies, she spent a year in Chengdu at Sichuan University. “I fondly remember the teahouses, the incomparably spicy Sichuan cuisine and the open and lively mentality of the people,” she says.

What she would do with her studies later seemed clear to everyone else at least. “In business, China is becoming increasingly important; you’ll surely find something!” she was told back then. However, the young woman had a different wish. She wanted to build bridges between the civil societies of China and Germany.

Since last December, she has been in exactly the right place for that: as the China Program Manager at the Stiftung Asienhaus, an organization that, according to its own statement, is committed to the realization of human rights, strengthening societal and political participation, social justice and environmental protection. “This type of work in the China context was like finding a needle in a haystack for me.” Regarding climate change, she emphasizes that the major problems of our time can only be solved together. For this, cultivating and opening dialogue spaces is essential.

Looking back on her first year in the China program, Leonie Suna-Kiefer feels like it flew by in a flash. There was also a lot to do: writing newsletters, organizing events, writing publications, networking and teaching a course at the China Starter Academy, an offering from the China Education Network for young people. Additionally, she is working with her colleague Joanna Klabisch on a current project titled “The Climate Crisis, Global China and Civil Society Advocacy in Asia.” The project creates platforms for representatives from civil society, business and politics to exchange views on the impact of Chinese investments on the climate crisis in other Asian countries.

“It is currently a very polarized time for work in the China context,” emphasizes Suna-Kiefer. “There is an increasingly hardening of political fronts between China and the so-called ‘West.’ This also affects our work.” After the extreme isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, relationship-building must be conducted at all levels. Suna-Kiefer currently faces changed working and dialogue possibilities in and with China and conditions that are becoming increasingly restrictive. Leonie Suna-Kiefer: “The work is challenging, but we are doing everything to continue collaborating with China on the civil society level.” Svenja Napp

Laura Bonsaver is the new Associate Director of Mentorships at the British non-governmental organization Young China Watchers.

Vincent Lian has been Marketing Communications Specialist for Greater China at the Norwegian classification society DNV since November. He was previously a Marketing Consultant at La Décoration in Shanghai.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

McDonald’s China is once again targeting the affluent customer base of young “pet parents”. After launching a cat bed shaped like a burger box in 2021, which sold out immediately, the US fast-food chain has now introduced a cat carrier that resembles a takeaway paper bag. The handbag, available in three designs and intended to double as a cat bed, is limited to 500,000 pieces and can only be obtained in combination with an expensive combo meal. The cat carriers quickly went viral on social media, with the hashtag “McDonald’s cat bed” reaching 160 million views on Weibo alone.

Xi Jinping’s guiding idea for China is that of a future of “common prosperity”. However, in times of sluggish economic growth and high unemployment, many Chinese no longer believe in this Chinese dream, which states that everyone can make it. On the contrary, many fear slipping down the social ladder.

Margaret Hillenbrand, a professor at the University of Oxford, has written a book about the new precariat in China. This includes migrant workers as well as university graduates who cannot find a job. They no longer feel picked up by promises of a “harmonious society”, she says in an interview with Amelie Richter. Hillenbrand also describes how a kind of “zombie citizenship” is slowly emerging, consisting of people whose ability to speak, think, or act independently is denied from above.

Foreign companies also have a responsibility when it comes to protecting people from oppression and exclusion. Companies that have been active in the Xinjiang region, affected by forced labor, have been particularly scrutinized for a long time.

VW was able to breathe a sigh of relief after the publication of a special audit of its plant in Xinjiang. No visible evidence of forced labor was found, and the company’s stock rose. However, the findings of the inspectors paint a mixed picture, writes Finn Mayer-Kuckuk. VW must continue to conduct audits and establish a functioning complaint management system to maintain the trust of investors in the long term. Social standards in the supply chain are becoming increasingly important worldwide.

Professor Hillenbrand, you are writing about precarity in China. Can you give us a short overview of your book?

The key question that I’m trying to ask in the book is: What does it mean to feel precarious in 21st-century China? Since the millennium, precarity has been a crucial keyword of our times – and its traction as a term only intensified after the 2008 financial crash. But despite the fact that China was and is prime precarious, “precarity” just wasn’t a conceptual framework that people were using in connection with Chinese society at all until quite recently, and especially not in relation to cultural forms.

So what are we looking at exactly?

To understand what precarity feels like in China, we have to get grips with what it means to have an underclass between 300 and 400 million people strong – the largest such cohort in human history. The term precarity has typically been linked to disposability, casualization, inequality, workfare rather than welfare. But China’s underclass has endured much worse. They’ve borne the brunt of the unequal hukou system and the prejudicial suzhi regime, modes of governmental control that are fundamentally rooted in social segregation – so much so that I think these underclass experiences are better understood in terms of expulsion, even banishment. In the book, I try to develop a set of conceptual tools for thinking about this pathway from precarity to expulsion, with a particular focus on cultural practices.

The living situation of migrant workers can be called precarious and by now is quite well known. What does precarity mean beyond the migrant workers?

Examples of other social groups who are experiencing precarity right now include elite university graduates who can’t get their first job; IT employees who are caught in China’s 966 working culture (966工作制); and delivery workers in the country’s platform industries who are discovering that even the so-called flexibility of the gig economy is becoming illusory because they’re trapped by algorithms that mandate very harsh working conditions. But there are also bleaker examples further down the path to banishment (some of whom do include migrant workers): people who’ve experienced forced eviction; people who endure a hard grind yet have their wages denied, especially in the construction industry; people who are forced by high rental prices to live in shipping containers and disused defence shelters. These are also people who are experiencing precarity, even expulsion, in China right now.

In the book, you are introducing the term of “zombie citizenship”. What does that mean?

It’s a state of abject exile from the shelter of the law, in which a very substantial minority of Chinese people currently languish, even though they theoretically enjoy full, even privileged personhood under the law of the land. If you look at Article 1 of the Chinese Constitution, it states clearly that the People’s Republic of China is a socialist state under the people’s democratic dictatorship led by the working class and based on the alliance of workers and peasants. I felt that the term “zombie citizenship” was necessary because it captures the sense in which many working people in China are chained by toil yet simultaneously cut loose from the safeguards of the law – despite what that law articulates in black and white.

So, these people are alive, they exist on paper, but they do not experience full citizenship because of their situation without basic rights or a city hukou?

Yes. I should say, though, that I don’t use the term “zombie” to describe people. It’s a provocative, even inflammatory word: zombies are creatures raised from the grave, with no power of speech, thought, independent deed. So I use the term “zombie citizenship” instead to describe the state of civic half-life into which some people are pitched in our current precarious moment. What’s more, the fear of tumbling into zombie citizenship doesn’t just menace the underclass; it also afflicts those who at first sight seem far more secure. This terror of a life without core rights looms like a precipice, and the notion of the cliff edge is the second conceptual tool I use in the book.

You are also connecting culture to precarity. How are those two combined, especially now in the world digital age?

In the book, I argue that this fear of downward mobility has brewed social strife during the first two decades of this century up to the pandemic – and that culture is where this tension breaks cover. I look at a wide range of artistic forms through which people who are living on the edge vent their feelings of dread and distrust, contempt and fury. These are dark feelings which are basically taboo in China’s so-called “harmonious society”, in which “positive energy” is supposed to be the dominant affective tone. I looked at various materials for the book: poetry, migrant worker magazines, social media posts, short online videos, performance art, documentary film, installations, interviews, and so on. And as I dug deeper into this archive, I found again and again that these dark feelings are always very personal; they’re highly antagonistic.

What does that look like?

There’s always some kind of hostile stand-off going on here: between avant-garde artists and the desperate migrants they recruit for humiliating performance pieces; between unpaid construction workers threatening on camera to jump from a rooftop and their immoral bosses on the street below; between poets on the Foxconn factory floor and the multinationals who enforce sweatshop conditions; between users of a livestreaming app who eat excrement or set off firecrackers on their genitals and their so-called social betters who lecture them for being vulgar. These encounters are tense and abrasive. But in a society where active solidarity is often blocked, these moments of antagonism can also be another way of creating vital points of contact between people.

Did the pandemic accelerate precarity in China?

For people who were already marginalized, Covid tended to intensify that marginality. A key example is delivery drivers. They were the workers who were actually going out into deserted cities to make essential deliveries; yet they were often stigmatized as potential carriers of the virus. In other words, they were socially punished for performing a crucial public service, and their precarity, which was already quite intense before the outbreak, was further amplified under pandemic conditions.

But even people who were ostensibly much more secure sometimes saw a peremptory withdrawal of rights. A telling example of this occurred during the Shanghai lockdown of 2022. Shanghai is a beacon city full of elite professionals; but many of these people found themselves essentially incarcerated in their homes, unable to access freedoms that they’d previously taken for granted. They suddenly realised that their grip on basic rights was perhaps just as tenuous as those lower down the social ladder.

In the last five-year-plan, the CCP already announced that they want to make changes in the hukou system. Would that be an effective remedy against precarity?

There have been a lot of high-profile statements in the last few years which finally seem to promise the end of hukou-based social apartheid. On one level, these changes seem inevitable, since Xi Jinping’s flagship policy of “common prosperity” is fundamentally incompatible with the continuation of hukou. But quite a few of these policy initiatives have only really scratched the surface. In particular, decision-making about hukouremains too devolved and decentralized, with the result that these shifts don’t tackle the problem of hukou restrictions in top-tier mega-cities, which are still the destinations of choice for many rural migrants. That’s why there’s a lot of scepticism in the media, both inside and outside China, about whether these reforms to the hukou system will go deep and wide enough. And some commentators even argue that control over space in China’s cities is actually tightening through tough policies around grid governance, demolition, and eviction.

Margaret Hillenbrand is Professor of Modern Chinese Literature and Culture at the University of Oxford. Her research focusses on literary and visual studies in 20th– and 21st-century China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Japan, especially cultures of protest and secrecy. Her books include Negative Exposures: Knowing What Not to Know in Contemporary China (Duke University Press, 2020) and On the Edge: Feeling Precarious in China (Columbia University Press, 2023).

The results of a special audit of the Volkswagen plant in the Chinese region of Xinjiang have tipped the scale: Union Investment, the fund company, continues to categorize VW shares as “investable” for sustainable investments. “The publication of the audit is a step in the right direction,” says Henrik Pontzen, Head of Sustainability in Portfolio Management at Union Investment, to Table.Media. However, VW must conduct additional audits in the long term and establish a functioning complaint management system to gain the trust of investors.

The day after the inspectors’ findings were published, a mixed picture emerges:

Nevertheless, the independent auditors could only conduct their investigation at the Ürümqi plant. The overall context in the Xinjiang region is difficult to fathom due to the opacity of the Chinese system. The potential supply chain risks in China are, therefore, not yet over for VW.

Since 2012, VW has been operating a factory in Ürümqi in western China, which is controversial due to its proximity to systematic human rights violations against the Uyghur people. The consulting firm Loening – Human Rights & Responsible Business examined the conditions in the factory and found no abnormalities.

The former human rights commissioner of the German government, Markus Löning, founded this company ten years ago. Loening and his company have a good reputation. However, Loening himself emphasized when presenting the report: “The situation in China and Xinjiang and the challenges of data collection for audits are known.” His team primarily looked for violations of labor regulations among the 197 employees on-site. “We could not find any evidence or proof of forced labor among the employees,” says Loening.

Much depended on Loening’s judgment for VW. The classification as a sustainable investment by companies like Union Investment is important for Volkswagen’s financing capability. Competing company Deka Investment has already withdrawn from the stock. Companies like Volkswagen rely on such major investors to raise capital.

However, according to Union Investment, VW is not yet where it needs to be; there is still much to do. “In China, audits must not be a one-time exercise,” says Pontzen. “In addition, a functioning complaint management system must be established.” The “weak corporate governance” at VW also remains an Achilles’ heel. Corporate governance refers to good corporate management.

Despite the theoretical decision to be able to include VW shares in funds labeled as sustainable, this is currently not the case for any product at Union Investment. The securities firm is thus delaying the practical consequence of the classification as “investable”. “We will continue to critically accompany VW as an active shareholder,” announced Pontzen.

Union Investment distinguishes between investability according to Article 8 and Article 9 of the EU plan for sustainable finance (the so-called disclosure regulation):

The umbrella organization Critical Shareholders (DKA), which represents small investors in environmental, social, and governance issues, also expressed skepticism. Unlike Union Investment, DKA generally questions the value of such inspections. Considering the limited scope of the investigation, the value of future audits is questionable, said DKA Managing Director Tilman Massa to the Reuters news agency.

Companies involved in China’s business, like professional shareholders, are aware that attention to social standards in the supply chain is increasing. The collapse of the Rana Plaza textile factory in Bangladesh is considered a turning point in perception; since then, the happenings in the supply chain have become a criterion for the selection of stocks for an increasing number of funds.

The next major milestone will be the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Act, if and when it comes. It focuses on environmental, human rights, and social issues in suppliers. Unlike the German Supply Chain Act, it not only obliges consideration of direct business partners but the entire supply chain. This is likely to be very complex for the Chinese industry.

According to a report by the Italian newspaper Corriere della Serra on Wednesday, the Italian government has officially informed China about the end of its participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Rome reportedly confirmed the formal withdrawal from the BRI to Beijing in a verbal note at the beginning of the week. However, both sides intend to revive the strategic partnership that has existed between Italy and China for more than ten years, though it was never fully implemented, according to the report, citing the letter. There has been no official announcement from either Italy or China on this matter.

In 2019, Italy became the first and only G7 nation to formally join the BRI. The then-Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte and Chinese President Xi Jinping signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with great pomp and ceremony at Villa Madama. However, the MoU fell short of expectations in reality. The cooperation agreement is set to expire in March 2024. Therefore, Rome had to make a decision by the end of the year.

The formal withdrawal of EU member Italy will not be a topic for the EU-China summit taking place on Thursday in Beijing. It has been clear for some time that Rome intended to leave the BRI. According to journalist and China expert Giulia Pompili, Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni “decided in every way for a smooth exit from the Silk Road”. Pompili added that Meloni wanted to avoid a strong anti-China stance upsetting Beijing on the 10th anniversary of the start of the strategic project. However, the timing is politically interesting: Italy had until Dec. 22 to announce its withdrawal. According to Pompili, the fact that Rome took this step just a few days before the summit can also be seen as a message of support to EU representatives. ari

In politics and business, there is much talk about de-risking in dealing with China. However, apparently, little has been done. According to the German Institute for Economic Research (IW), German companies are not doing enough to reduce their one-sided dependencies on China. “De-risking has started, but we must not be under any illusions: too little is happening, even though time is of the essence,” said IW trade expert Juergen Matthes on Wednesday, according to the AFP news agency. Many companies are even increasing their imports from the People’s Republic instead of reducing them.

The IW study shows that out of 400 surveyed companies in North Rhine-Westphalia alone, 40 percent are dependent on products from China. About one-third of them expect that this dependence will not change in the future, and 48 percent even anticipate a growing importance of China.

It is actually the responsibility of companies to reduce critical dependencies, the IW told AFP. However, due to state subsidies, the Chinese industry remains a good and cheap trading partner. If companies want to remain competitive, they must partner with China. “There is a kind of market failure here,” said Matthes. From an overall economic and geostrategic perspective, it is urgently necessary to reduce dependencies.

If the companies’ attitude does not change soon, politics should create further incentives to reduce critical dependencies, Matthes demanded. flee

Germany and Taiwan are set to engage in closer civil society exchanges, according to the German foreign office. The German Institute Taipei and the Taipei Representation in Berlin plan to establish a new German-Taiwanese dialogue platform, as announced by the foreign office on Wednesday. The platform’s goal is to “promote vibrant civil society exchange, particularly in light of increased bilateral economic contacts”. The dialogue platform is expected to have twelve members on each side and will meet annually, alternating between Germany and Taiwan. Green Party European policy politician Reinhard Buetikofer will chair the German side. The platform’s work is expected to commence next year. ari

China’s automotive market showed growth again in November. According to the China Passenger Car Association (PCA), 2.06 million vehicles were delivered to customers last month, an increase of about a quarter compared to a year ago.

However, lockdowns in numerous Chinese regions contributed to a decline in demand for cars a year ago. Sales in November increased by one percent compared to October.

EVs continue to advance, with almost every third car sold being fully electric or plug-in hybrid. This represents almost a third more than a year ago, according to the information. flee

Prada aims to double its business in China, according to Gianfranco D’Attis, the CEO of the Italian brand, speaking to reporters in Shanghai. “We have many ambitions in China,” said the former Dior manager who took over at Prada in January. “This is also accompanied by an increase in our investments.”

D’Attis did not provide an exact timeframe for his plan but stated that the increased investments would not necessarily mean a significant increase in the number of stores opened in the country. “Not only is the number of stores important to us, but also the quality of the stores, larger stores with more categories, more localized products, more experiences, more hospitality, more events,” he said.

The Prada Group, which includes the classic English shoe manufacturer Church’s among its brands, reported a 10 percent increase in revenue for the third quarter in November, stating that strong sales in Asia and Europe helped offset weakness in North and South America. China is one of the world’s most important luxury markets. According to consulting firm Bain’s forecasts, China is expected to account for nearly 40 percent of global luxury sales by 2030. rtr

Leonie Suna-Kiefer first heard the Chinese language from tourists in her small hometown on Lake Constance. Even as a child, she was fascinated by Mandarin. After graduating from high school in 2012, she traveled to Thailand, Laos and finally to China. “I was intimidated, fascinated and full of curiosity about the unknown,” she recalls.

She also realized that her Germany-influenced perception of China did not align with what she experienced there. “I became aware that I had come to China with a certain arrogance, only to find that the country had developed in a completely different way and, from a technological perspective, was surpassing Germany.” Instead of bicycles, only electric scooters were seen on the streets of Chinese megacities.

Back in Germany, her interest was piqued – “and a certain ambition to master this seemingly unlearnable language”. In Cologne, she studied Chinese regional studies and wrote her master’s thesis on the Chinese Social Credit System. “It was important for me to open up a new perspective on the Social Credit System, to show how it is reported in Chinese media, and what role the system actually plays in people’s daily lives.”

Another focus was on developments in Chinese climate policy, which Suna-Kiefer continues to follow closely. During her studies, she spent a year in Chengdu at Sichuan University. “I fondly remember the teahouses, the incomparably spicy Sichuan cuisine and the open and lively mentality of the people,” she says.

What she would do with her studies later seemed clear to everyone else at least. “In business, China is becoming increasingly important; you’ll surely find something!” she was told back then. However, the young woman had a different wish. She wanted to build bridges between the civil societies of China and Germany.

Since last December, she has been in exactly the right place for that: as the China Program Manager at the Stiftung Asienhaus, an organization that, according to its own statement, is committed to the realization of human rights, strengthening societal and political participation, social justice and environmental protection. “This type of work in the China context was like finding a needle in a haystack for me.” Regarding climate change, she emphasizes that the major problems of our time can only be solved together. For this, cultivating and opening dialogue spaces is essential.

Looking back on her first year in the China program, Leonie Suna-Kiefer feels like it flew by in a flash. There was also a lot to do: writing newsletters, organizing events, writing publications, networking and teaching a course at the China Starter Academy, an offering from the China Education Network for young people. Additionally, she is working with her colleague Joanna Klabisch on a current project titled “The Climate Crisis, Global China and Civil Society Advocacy in Asia.” The project creates platforms for representatives from civil society, business and politics to exchange views on the impact of Chinese investments on the climate crisis in other Asian countries.

“It is currently a very polarized time for work in the China context,” emphasizes Suna-Kiefer. “There is an increasingly hardening of political fronts between China and the so-called ‘West.’ This also affects our work.” After the extreme isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, relationship-building must be conducted at all levels. Suna-Kiefer currently faces changed working and dialogue possibilities in and with China and conditions that are becoming increasingly restrictive. Leonie Suna-Kiefer: “The work is challenging, but we are doing everything to continue collaborating with China on the civil society level.” Svenja Napp

Laura Bonsaver is the new Associate Director of Mentorships at the British non-governmental organization Young China Watchers.

Vincent Lian has been Marketing Communications Specialist for Greater China at the Norwegian classification society DNV since November. He was previously a Marketing Consultant at La Décoration in Shanghai.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

McDonald’s China is once again targeting the affluent customer base of young “pet parents”. After launching a cat bed shaped like a burger box in 2021, which sold out immediately, the US fast-food chain has now introduced a cat carrier that resembles a takeaway paper bag. The handbag, available in three designs and intended to double as a cat bed, is limited to 500,000 pieces and can only be obtained in combination with an expensive combo meal. The cat carriers quickly went viral on social media, with the hashtag “McDonald’s cat bed” reaching 160 million views on Weibo alone.