Robert Habeck spent Thursday in South Korea. And he didn’t want this visit to be seen as just a stopover on his way to China, reports Finn Mayer-Kuckuk, who is accompanying the German Economy Minister on his Asia visit. The Vice-Chancellor’s mission is: de-risking. Find out in today’s China.Table how successful he was in South Korea in soliciting cooperation and what he can expect from the difficult talks in China.

However, another high-level political encounter should cause the Europeans far more concern: Putin’s visit to North Korea culminated in an invocation of brotherhood in arms and a mutual military defense agreement in the event of “armed aggression.” Michael Radunski analyzes the impact of the friendship between the two despots and China’s position on this.

Economy Minister Robert Habeck is currently visiting South Korea – and insists that his visit to Seoul is not just a stopover on his way to Beijing, but has its own meaning and purpose. During his one-day stay in the South Korean capital, he met with Prime Minister Han Duck-soo. The Vice-Chancellor mainly focused on the close ties between North Korea and Russia.

This makes Russia’s war against Ukraine acutely dangerous for South Korea. After all, Russia could supply North Korea with modern technology in return for the mass production of ammunition. This would make North Korea’s highly equipped army even stronger – at a time when its threats against the South are becoming increasingly aggressive. “Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine is not just a localized war,” Habeck said after the talks with the Prime Minister. “Concern in South Korea is growing.”

This is why Habeck increasingly regards South Korea as a close partner among the democratically-minded countries that support Ukraine. Although South Korea does not directly supply weapons to Ukraine, it is at least involved in the ring exchange, in which it supplies weapons to countries that directly supply Ukraine.

Beforehand, the Minister spent some time in a hot and dusty palace complex, listening to a German professor explain the initial contacts between Germany and Korea. What seemed like a sightseeing visit was actually a valuable introduction to the region’s geopolitical dynamics. The palace was deliberately destroyed during the Japanese occupation between 1910 and 1945 and is currently being gradually restored.

The Japanese occupiers had the Korean queen beheaded by assassins. Hearing such stories on the spot helps understand the irreconcilable relationship between the neighboring countries. So sweating in the hot and humid weather may even have been worth it.

Habeck also visited a quantum nanoscience research center. This was part of his mission to find alternatives to China in key fields. In this case, it is about research cooperation and access to advanced technologies. Germany does not want to be dependent on China (and preferably not too reliant on the United States either) for the next generation of future technology. It needs new partners. Like South Korea.

Overall, the Minister tried to breathe life into his mission of risk minimization during the visit. During the talks, he emphasized the strong interest of German companies in expanding their business in South Korea. Speaking to Han, he called for more cooperation with German SMEs.

One example should particularly please him as climate minister: The energy group RWE is currently trying to get a foot in the door for the construction of offshore wind farms. “The entire wind sector in South Korea is still surprisingly underdeveloped,” says David Jones, head of RWE Renewables in Seoul and head of the offshore division in Korea.

So far, nuclear power has been the big alternative to coal and oil. The country’s ambitious expansion targets are barely achievable. Therefore, Jones is hoping for a tailwind from the government if he wants to give the industry a boost in cooperation with local partners. So far, many projects have failed due to red tape. According to Jones, the construction of offshore wind farms is far less complicated in Europe.

On Friday, after a visit to the border with North Korea, he will continue his trip to China. Here, he will hold trade talks on Saturday. They will be characterized by contradictory goals, because Germany’s varying interests are intermingled with the EU’s activities:

His Chinese dialogue partners will be testing Habeck, who will be visiting Beijing for the first time: Is he a potential representative of Chinese interests in the EU like Olaf Scholz? Or is he as uncompromising as his party colleague and Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock? Is he embracing his traditional role as German Economy Minister, or will his actions be dominated by his Green Party influences?

Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un have signed a comprehensive strategic partnership treaty in Pyongyang. Putin traveled to North Korea on Wednesday for the first time in a quarter of a century to deepen relations personally.

At first glance, the new treaty appears to be tailored to current needs: Russia needs more ammunition for its war in Ukraine, and isolated North Korea has gained a powerful partner to ensure the security of the Kim regime. However, a closer look reveals that the scope of the agreement is much more far-reaching and could pose a threat to the security of the USA and Europe.

Firstly, the direct effects. North Korea’s state media published the treaty on Thursday. Article IV states that should one of the two countries “get into a state of war due to an armed aggression,” the other “shall immediately provide military and other assistance with all the means at its disposal.” As Russia is already at war, it can be assumed that North Korea will significantly step up its military support in the coming weeks and months.

The deliveries are already considerable: US intelligence agencies believe that Russia has received more than 10,000 shipping containers – the equivalent of around 260,000 tons – of ammunition or other military equipment from North Korea since September. In addition, Russian forces have fired several North Korean missiles at Ukraine, says Pak Jung, an insider expert on North Korea.

Pak, a long-time CIA analyst, has written a book about ruler Kim Jong-un and is now the deputy US special representative for North Korea. Pak clarifies: “North Korea is not doing this for free. There’s almost certainly things that North Korea wants in return, and we’re concerned about what might be going on to the other side. We also worry about what North Korea could be learning from Russia’s use of these weapons and ballistic missiles on the battlefield and how that might embolden or and help North Korea even further advance their weapons program.”

This brings us to the long-term consequences. Kim Jong-un has already spoken of an “alliance” between North Korea and Russia. Things are probably not quite there yet, but the specific points should be enough to raise concerns in the West. For example, Putin said in Pyongyang that Russia “does not rule out military-technical cooperation with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in accordance with the document signed today.”

Putin is being vague, leaving many questions unanswered:

North Korea’s interests are apparent. The Kim regime is working hard on its nuclear weapons and missile program. Everything is subordinated to this, with the result that while the population suffers hardship and hunger, Kim’s weapons experts have made remarkable progress. However, they have not yet been able to develop a warhead that can survive re-entry into the atmosphere. It is the missing piece of the puzzle that actually poses a serious threat to Europe and the United States. Russia has this technological know-how. But will it pass it on to Pyongyang?

Probably not. Or not yet. Because at the meeting between Putin and Kim in Pyongyang, there is also an invisible elephant in the room: China. Both Russia and North Korea need China’s support. Neither Putin nor Kim Jong-un can afford to antagonize Beijing’s ruler Xi Jinping. The leadership in Beijing will be watching closely to see how far the new partnership between Russia and North Korea progresses. Xi will certainly not tolerate the old Soviet-era strategy, when Pyongyang alternately played Beijing and Moscow off against each other.

The current “division of labor,” on the other hand, is very much in Beijing’s interest: China supplies Russia with what it needs to keep its war economy running. When it comes to direct arms supplies, however, Beijing is not (yet) prepared to cross a red line. “That’s why North Korea – which, unlike China, has no trade to lose with the West and does not want to present itself in international politics as a peace mediator or Europe’s favored partner – is now taking on the role of arms supplier,” Joel Atkinson, Professor of China Studies at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul, told Table.Briefings.

This division of labor reflects the big shared goal of North Korea, Russia and China: Their rejection of a Western-dominated world under the auspices of the United States.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg reacted with corresponding concern. “We need to be aware that authoritarian powers are aligning more and more. They are supporting each other in a way we haven’t seen before,” he said in Ottawa on Wednesday. North Korea had supplied Russia with “an enormous amount of ammunition,” while China and Iran were also supporting Russia militarily in the war against Ukraine.

For this reason, NATO intends to work more closely with its allies in the Asia-Pacific region. To this end, the heads of government of Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea have been invited to the NATO summit in Washington next month.

Meanwhile, Putin has traveled from North Korea to Vietnam, a country that is very flexible with its “bamboo policy.” Observers say potential arms deliveries are also on the agenda in Hanoi. In addition to Deputy Defense Minister Alexander Fomin, Putin’s delegation also includes the head of the Russian authority for military-technical cooperation, Dmitry Shugaev, and the director of the arms company Rosoboronexport, Alexander Mikheyev.

A recent investigation by the German non-profit site Correctiv, which examined the ties between professors at RWTH Aachen University and China, has reignited the debate about relations between German research institutions and the People’s Republic.

“The findings describe the tip of the iceberg. As far as investigative research is concerned, other countries, such as the UK and the United States, are now far ahead of us. It is high time that all universities in Germany were subjected to an independent investigation,” Andreas Fulda, political scientist and China expert at the University of Nottingham, demanded in response to a question from Table.Briefings.

In its report, the investigative team details several isolated cases of researchers at RWTH Aachen University maintaining ties to universities belonging to the “Seven Sons” or the National University for Defense Technology (NUDT). According to the Australian think tank ASPI, this is a group of seven Chinese universities listed as civilian universities but with close ties to the military and arms industry.

The report follows a series of similar investigations, such as an earlier one by Correctiv, the German newspaper FAZ, or US expert Jeffrey Stoff. All reports suggest that German academic institutions are, or at least were, too naive in their handling of cooperation with China. According to the latest Correctiv report, at least 19 of about 100 professors in the RWTH faculties of mechanical and electrical engineering are believed to have cooperated with researchers from the “Seven Sons” or NUDT.

Andreas Fulda says it cannot be assumed that RWTH is an isolated case. “Technical universities in the STEM fields are of particular interest to the Chinese Communist Party.” Findings from basic and applied research would help the Chinese party leadership better control the population with technological innovations and advance the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army.

In response to a question from Table.Briefings, a spokesperson for RWTH Aachen University explained that some of the examples referred to by Correctiv were years ago and that review mechanisms and sensitivity had since changed. They further argue that other publications fell into the open-access category anyway and concerned publicly accessible developments in global basic research.

“The report cannot name any examples of goods transfers prohibited under export control law. We take supervision in accordance with the existing rules very seriously and constantly scrutinize our mechanisms,” a spokesperson said. The RWTH explained that there was a long tradition of cooperation with China and correspondingly standardized processes, an extensive network and awareness-raising measures for researchers – ranging from onboarding to specific seminars.

Furthermore, RWTH’s China office in Beijing “provides additional information and on-site China expertise.” The University says that it is also in constant contact with research alliances, partner universities and security authorities on this topic. It is actively involved in thematic working groups at German and European universities on legal, ethical and security aspects of international research, often with a particular reference to China.

The Correctiv report also criticizes the practice of setting up limited liability companies for professors to raise third-party funds for application-oriented research in return for profitable contracts from China. This structure is common transfer practice in many scientific fields. However, unlike university collaborations, funds that flow from Chinese companies via professors’ limited liability companies, for example, are not recorded.

Based on the investigation, the German Association of University Professors and Lecturers (DHV) urges the German federal and state governments to provide adequate basic research funding. In an interview with Correctiv, DHV spokesperson Matthias Jaroch calls this the “most effective means” against possible financial influence. Without sufficient basic funding, universities would have to rely on alternative funding sources. Jaroch also calls for the greatest possible transparency and the disclosure of all professors’ cooperation agreements.

Walter Rosenthal, President of the German Rectors’ Conference (HRK), declined to comment explicitly on the cases at RWTH Aachen University. However, he points out that scientists who are employed at universities are required to obtain permission to work at start-ups. “To do this, they submit an application for secondary employment to their universities, which must include the scope of the activity.” The universities then must evaluate these applications. Approval could then be granted with conditions.

In the debate, the academic community repeatedly refers to academic freedom and university autonomy. Recently, Anja Steinbeck, spokesperson for the universities in the HRK, and Joybrato Mukherjee, President of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), expressed these sentiments in conversations with Table.Briefings. The general tenor was that the government should not interfere. However, both also emphasized the responsibility of the institutions to deal intensively with the topic and to establish awareness-raising and supervisory measures.

The DAAD also declined to comment on the RWTH Aachen University. However, the DAAD believes that “scientific cooperation with China should be realistic: This means that universities should sharpen their scientific interests in dealing with China, recognize opportunities and risks and develop or expand clear review procedures and processes for existing or future collaborations.” China expertise should always be developed and expanded independently, the DAAD said.

For Andreas Fulda, the Correctiv research shows “that we unfortunately cannot rely on academic self-governance.” Even if there are justified reservations about state interference for historical reasons: “We now urgently need clear and applicable state transparency rules. However, due to German federalism and the weakness of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, I think it is rather unlikely that decisive action will be taken.”

However, the German Education Ministry sees progress in terms of the scientific institutions taking responsibility. “The guidelines developed and review processes initiated by the scientific organizations and universities for cooperation with China are an important step,” a spokesperson told Table.Briefings. “In cooperation with the relevant authorities, we will continue to increase the information and awareness of universities and research institutions and support the development of independent China expertise.”

June 24, 2024; 4 a.m. CEST (10:00 a.m. Beijing time)

EU SME Center/European Chamber: Working Group meeting (online): China’s Payment Landscape and How to Navigate It More

25.06.2024, 12:30 Uhr

Confucius Institute Heidelberg, film matinée (on site): “Of Color and Ink” (Zhang Weiming) with the director in attendance More

June 25, 2024; 10 a.m. Beijing time

German Chamber of Commerce Machinery Day (in Suzhou): Powering the Future: Digitalization and Sustainability in the Smart Manufacturing Industry More

June 27, 2024; 10 a.m. CEST (4 p.m. Beijing time)

Dezan Shira & Associates , Webinar: Compliance in China: New Company Law Impacts on Foreign-Invested Enterprises (FIEs) from Legal, Financial, and Tax Perspectives More

June 27, 2024; 11 a.m. CEST (5 p.m. Beijing time)

Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Global China Conversations #33: How (differently) have Chinese Firms invested in and changed Africa? More

June 27, 2024; 2:30 p.m. CEST (8:30 p.m. Beijing time)

CNBW – Working Group Sino-German Corporate Communications (online) Navigating China’s E-Commerce Frontier: Insights and Strategies with Damian Maib More

July 1, 2024; 4 p.m. Beijing time

EU SME Center, SME Roundtable in Guangzhou: Insights into China’s Policy Updates More

A survey has found that 73 percent of Chinese EV manufacturers have experienced a drop in sales in the European market due to the EU investigation into state subsidies. The Chinese Chamber of Commerce in Brussels presented the survey on Wednesday in cooperation with the state-run China Economic Information Service. 67 percent of the companies stated that the EU investigation had affected their brand’s reputation. According to the Chamber of Commerce, the survey was conducted in May and April this year among more than 30 manufacturers and suppliers in the Chinese EV industry.

The survey found that the investigation had a negative impact on cooperation with European partners: 82 percent of respondents were less confident about future investments in Europe. Accordingly, 83 percent of the companies surveyed stated that European dealers and leasing companies were less optimistic about the prospects for cooperation. Around two-thirds (67 percent) of respondents said that the European market was still of crucial importance and that they wanted to build production facilities in Europe within the next five years.

In the report, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce criticizes the EU Commission’s actions and claims it has deliberately overestimated the market share of Chinese EVs in Europe. Last week, the Brussels authority announced extra tariffs of up to 38.1 percent on Chinese EVs. In response, Beijing announced an anti-dumping investigation into European pork earlier this week. Both sides repeatedly emphasized that they wanted to resolve the conflict through negotiations. ari

Polish President Andrzej Duda will pay a state visit to China from June 22 to June 26 at the invitation of Chinese President Xi Jinping. This was announced by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying on Thursday.

At the regular press conference of the Chinese Foreign Ministry, it was announced that Andrzej Duda would meet with several top Chinese politicians during his stay in China. In addition to Xi, these include Premier Li Qiang and the Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, Zhao Leji. cyb

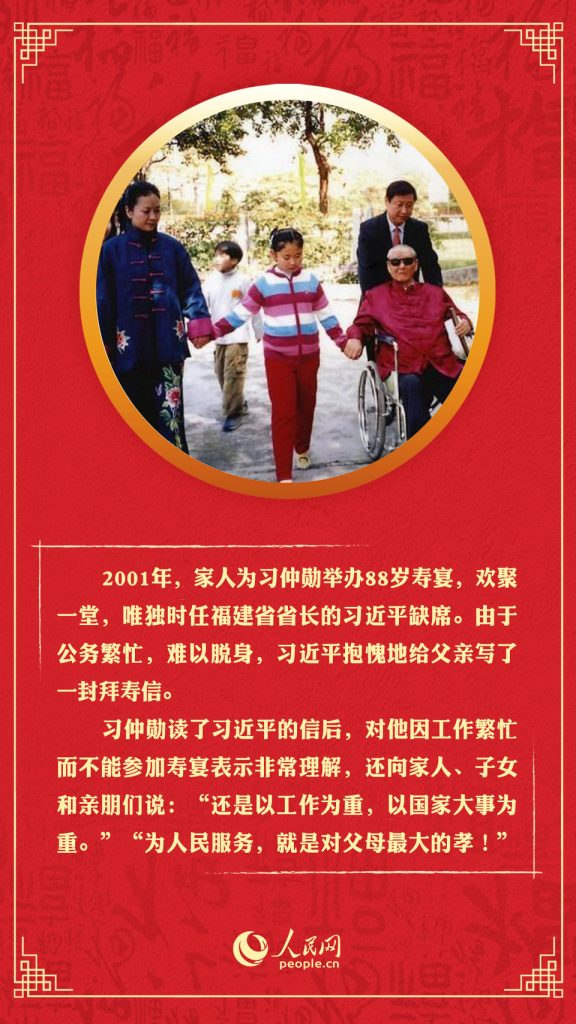

How was the life of a high-ranking party functionary and revolutionary, who many Chinese observers claim became a market reformer after years of persecution by Mao while remaining an upstanding communist? The man in question is not Deng Xiaoping but Xi Zhongxun, who is even better known as the father of China’s now sole ruling Communist Party leader, Xi Jinping.

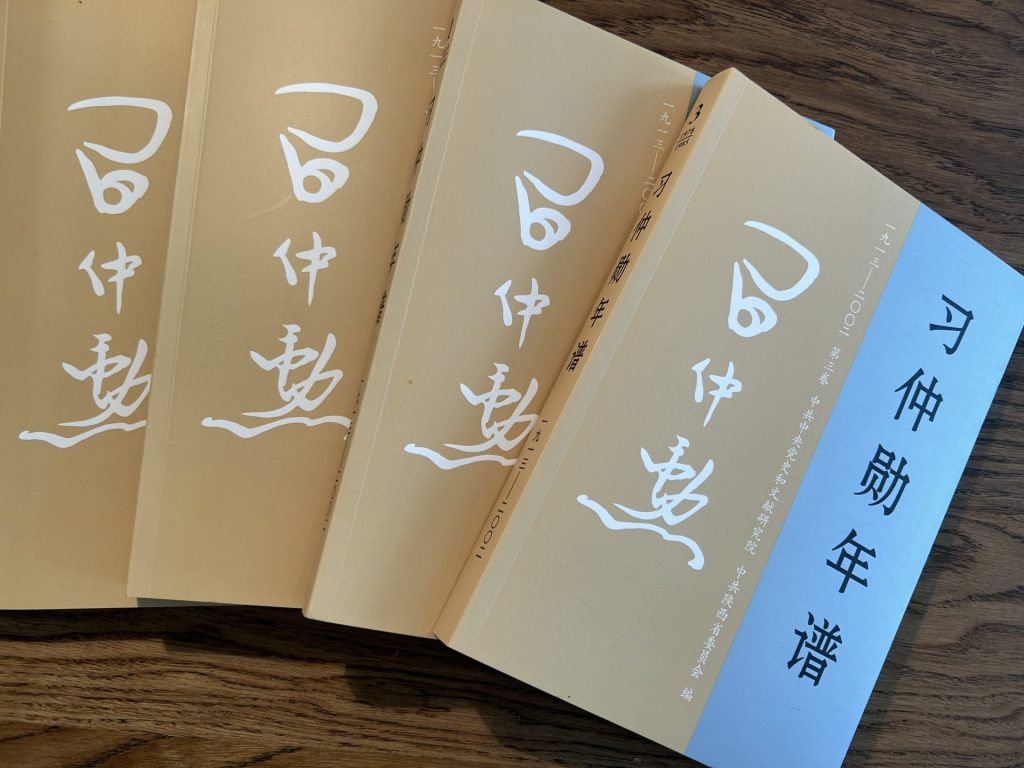

The massive four-volume, 1448-page chronicle of Xi Zhongxun (习仲勋年谱) promises to hold answers. It begins with his birth on October 15, 1913, and ends with his death on May 24, 2002. According to the news agency Xinhua, it is so important “that we can unite even more closely around comrade and Party core, Xi Jinping.” 更加紧密地团结在以习近平同志为核心的党中央周围.

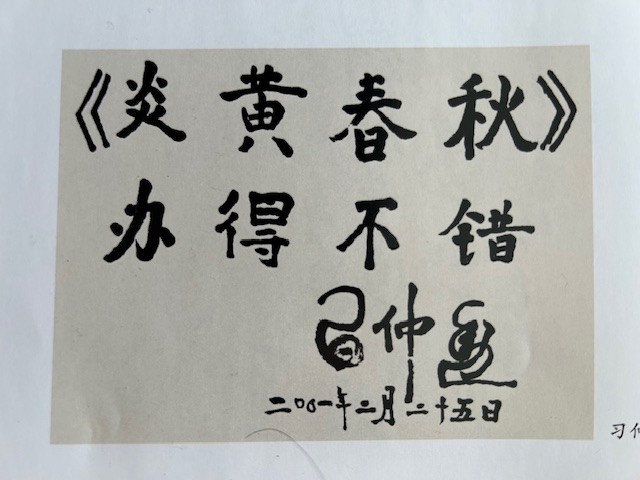

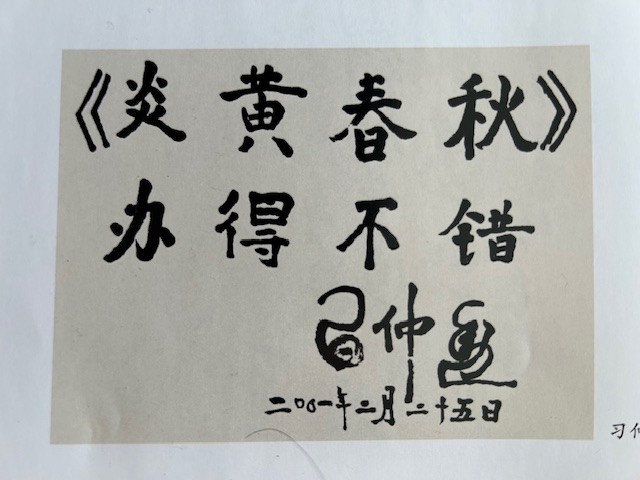

When reading Chinese propaganda, it is important to read between the lines; when reading Party chronicles, you should pay attention to what they don’t tell you. When friends brought me this hefty biography, weighing more than two kilograms, I opened the page for February 25, 2001. Like a logbook, it reads: Xi Zhongxun writes a calligraphy for the Longmen traditional school: “A great place. Cradle of many Chinese talents.”

However, on that day, the then 88-year-old scribbled a much more significant dedication: To mark the tenth anniversary of the magazine “Yanhuang Chunqiu,” which, as a forum for internal Party debates, had dedicated itself to critically re-examining the past, he calligraphed: “Yanhuang Chunqiu is well-made.” The magazine’s publishing director and authors used to be high-ranking party officials loyal to Mao before they were unfairly persecuted by his tyranny.

That was precisely what happened to Xi. As a communist guerrilla leader in 1930s Shaanxi, he was instrumental in helping a grateful Mao and his Long March troops survive. He rose in Mao’s favor and later became vice premier of the People’s Republic. But then the Chairman, sensing conspiracies everywhere, put him on the hit list. During the Cultural Revolution, Xi was particularly brutally persecuted. His entire family fell from grace.

When I learned in 2015 that China’s leadership was planning to close the critical magazine, I asked the editor-in-chief, Yang Jisheng, about it. He showed me the calligraphy of Xi’s father in his office. “This will protect us,” he hoped.

Yang was wrong. Barely a year later, dogmatists in Xi Jinping’s employ launched polemical attacks against Yanhuang Chunqiu. They claimed that the magazine was defaming Mao and China’s system to “capsize the socialist boat of the People’s Republic.” The magazine was immediately seized, and the entire editorial team was fired. I happened to personally witness the “end of a liberal legend” by the ideologues’ coup. No wonder it is forbidden to even mention Xi Zhongxun’s calligraphy nowadays.

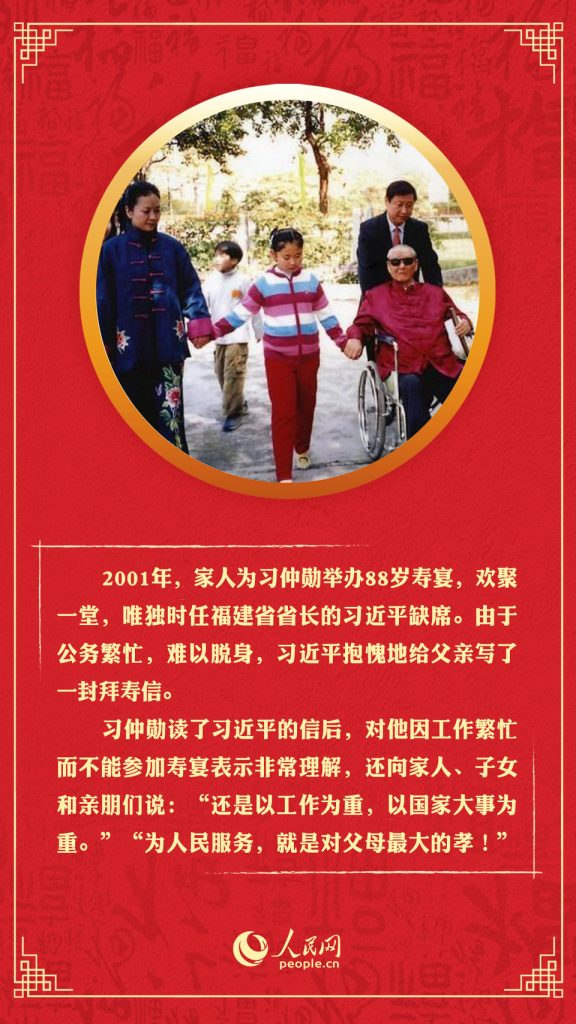

Despite all the censorship, the newly published chronicle remains a treasure trove for Party historians, who Beijing is increasingly denying access to archives. It also helps identify the contradictions in the personality of Xi Jinping, who was not always the ideological hardliner we know today. A letter he wrote to his father on his 88th birthday, dated October 15, 2001, has been published in full. It is partly known because China’s propaganda cites it as an example of Xi’s (Confucian) virtue of filial piety towards his father.

However, in the full letter, Xi also mentions other motives. He praises his father for “never having anyone persecuted throughout his life,” 一辈子没有整过人 and because he “never lied.” He also reminds him of the Cultural Revolution, during which his family was persecuted: “When people shouted at us on the street as ‘sons of dogs,’ I stood firm in my judgment. My father is a great hero.”

That sounds noble, but neither Xi Jinping nor his father are willing to critically reflect on Mao and his crimes. Both of them place the Party and the state before personal hardship. They do not see themselves as enlightened reformers and certainly not as liberal communists. Xi’s apple does not fall far from his father’s tree.

Hence, the new chronicle downplays Mao’s responsibility for his father’s persecution. Mao’s leftist followers, including intelligence chief Kang Sheng, are blamed for Xi Zhongxun losing Mao’s trust and being persecuted and exiled from 1962 to 1978. Their intrigues led the Chairman to believe in a conspiracy against him and an “anti-Mao clique” to which Xi Zhongxun belonged. He allegedly tried to manipulate the Party’s sentiment against Mao through a revolutionary novel about the guerrilla period, aiming to rehabilitate Mao’s once-defeated inner-party enemies.

Today, Xi Jinping has made any critical debate about Mao and especially his Cultural Revolution taboo. That is why the new chronicle is only allowed to cover the events of the worst years for Father Xi Zhongxun, from 1964 to 1977, until the fall of the Gang of Four, in just 21 of its almost 1500 pages. It recounts when and how often fanatical Red Guards violently abducted his father, who was working in a tractor factory in Luoyang, to their struggle and criticism sessions and tortured him for hours.

It gives a more factual account of Xi’s role as an effective reformer after his rehabilitation in 1978, whom Deng Xiaoping sent to Guangdong to support its modernization as provincial and Party leader. Many details about his help in politically rehabilitating tens of thousands of Guangdong officials who were victims of the Cultural Revolution or defusing a crisis surrounding the mass exodus of Chinese farmers to Hong Kong are new.

Xi Zhongxun also solved the injustice of the Canton dissidents sentenced to life. Under the pseudonym “Li Yizhe,” they gained worldwide fame for a sensational wall newspaper in which they called for democracy and the rule of law in 1974 while Mao was still alive. They were the forerunners of an extra-party opposition in China.

The book describes in detail how Xi was able to rehabilitate the authors of the wall newspapers and dozens of others involved in the case within his own Party bureaucracy and get them all released from prison. He met with the four LiYizhe oppositionists seven times in 1979 alone. However, he demanded they cease opposing the system and stop calling for Western-style “democracy and the legal system.”

He stood up for them, not because they opposed Mao and the system, but because they opposed Mao’s ultra-leftist followers. His father held Mao in high regard to the end and saw his own bitter fate as more of a random workplace accident. His son thinks no differently today.

The seemingly encyclopedic chronicle is not meant as historical source material. According to an unwritten rule, it is a status symbol of outstanding party leaders who have earned a place in the communist pantheon of Chinese revolutionaries since 1921.

So far, the honor of being portrayed in a dedicated Party chronicle has been bestowed upon less than a dozen former Communist Party bigwigs. Chen Jin, a deputy director of the Central Committee Research Office for Archival Documents, revealed in 2011 that apart from the unfinished chronicles of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, all other chronicles of eligible former CP leaders had been completed. 老一辈主要领导人官方传记基本出齐

But Xi Zhongxun is allowed to join this elite. His son probably played a role in this. For the time being, this chronicle is the final act with which Xi Jinping is righting the wrongs done to his father.

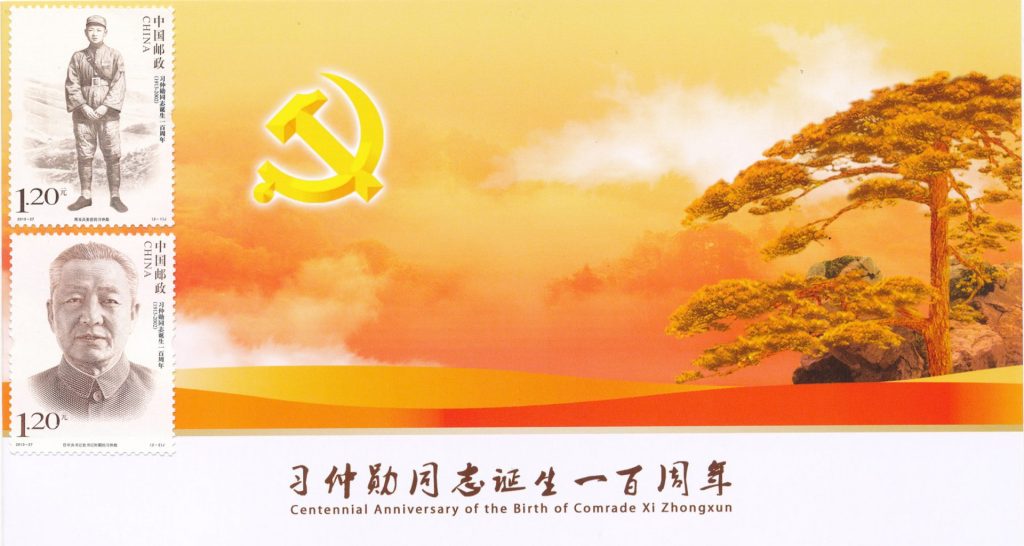

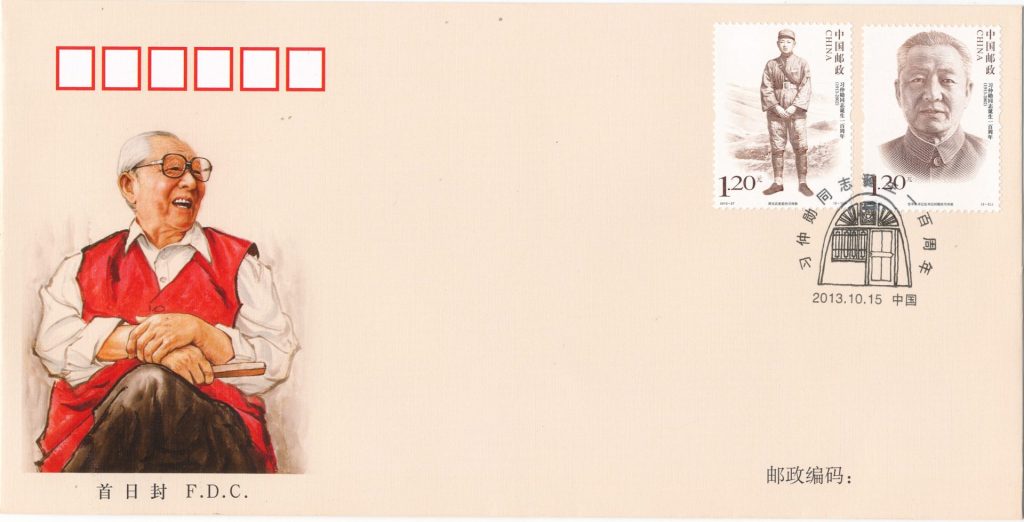

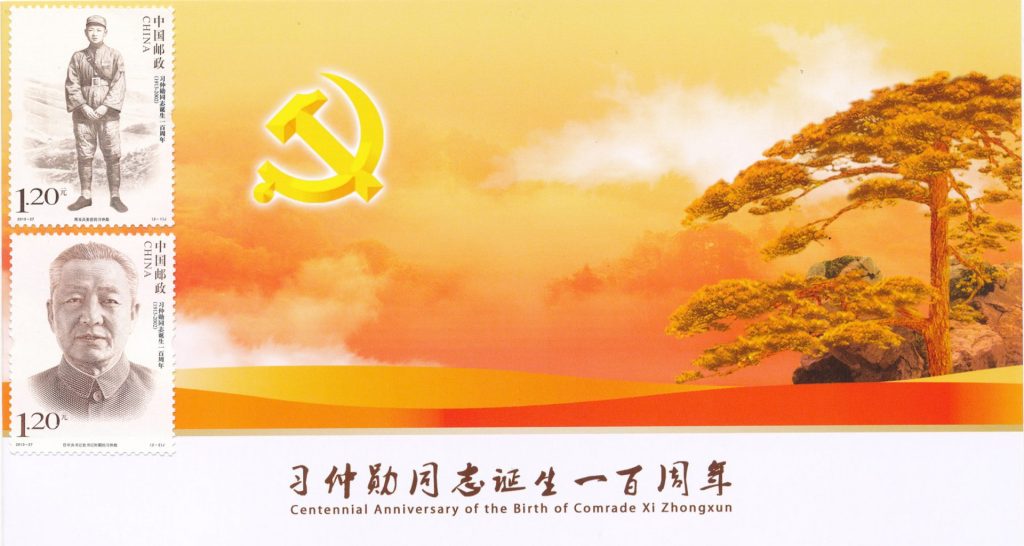

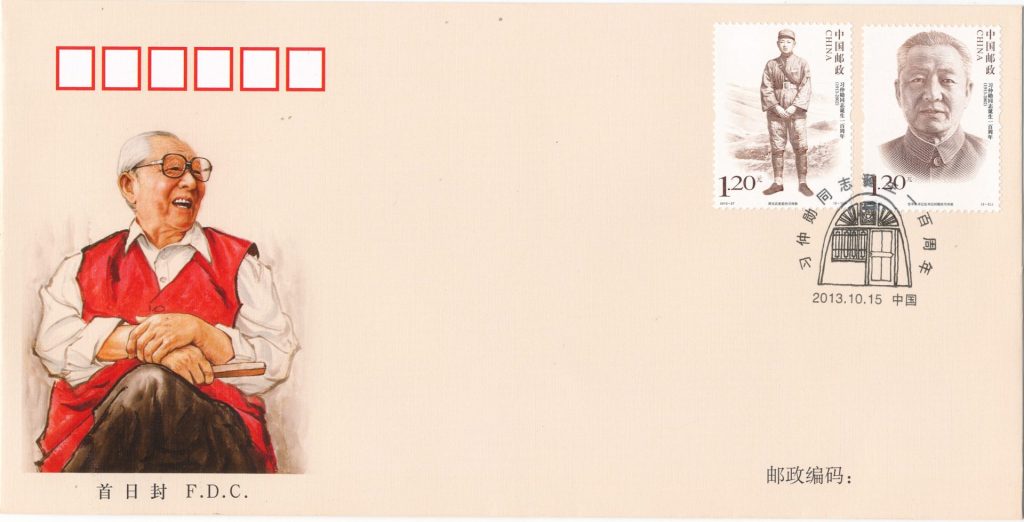

From 2002 to 2005, the Xi family erected a gigantic mausoleum for their father in his hometown of Fuping. Then, it was the state’s turn. Soon after his election as CP leader and president, Xi Jinping had his father’s 100th birthday celebrated in the Great Hall of the People on October 15, 2013. China’s postal service had to print special stamps for the occasion.

Coinciding with the planned publication of the new chronicle, state broadcaster CCTV aired its second six-part television documentary in December about Xi Zhongxun and a life dedicated to the Revolution. The series is aptly named 赤诚 “Total Devotion.” Here, too, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

Anton Melchers, the current CEO of Melchers Shanghai, will return to the German headquarters in Bremen in July as part of a strategic restructuring. His successor, Claus Toxvig, will take over the business in China.

Yudan Liu has been Director of China Desk at the auditing firm SW International in Frankfurt am Main since June. She was previously team leader of the China Desk at the banking consultancy Dornbach, also in Frankfurt.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Around 2006, China was the largest newspaper market in the world, and such newspaper kiosks were once commonplace in Shanghai’s urban landscape. Some of them were set up to create jobs for former employees of state-owned enterprises who were laid off as part of restructuring measures.

With the boom in online media, the number of kiosks across the country fell drastically, and the pandemic dealt a killing blow to many. In Shanghai, one of the last survivors on Wusong Road will finally close its shutters at the end of the year. Owner Jiang Jun will retire after three decades.

Robert Habeck spent Thursday in South Korea. And he didn’t want this visit to be seen as just a stopover on his way to China, reports Finn Mayer-Kuckuk, who is accompanying the German Economy Minister on his Asia visit. The Vice-Chancellor’s mission is: de-risking. Find out in today’s China.Table how successful he was in South Korea in soliciting cooperation and what he can expect from the difficult talks in China.

However, another high-level political encounter should cause the Europeans far more concern: Putin’s visit to North Korea culminated in an invocation of brotherhood in arms and a mutual military defense agreement in the event of “armed aggression.” Michael Radunski analyzes the impact of the friendship between the two despots and China’s position on this.

Economy Minister Robert Habeck is currently visiting South Korea – and insists that his visit to Seoul is not just a stopover on his way to Beijing, but has its own meaning and purpose. During his one-day stay in the South Korean capital, he met with Prime Minister Han Duck-soo. The Vice-Chancellor mainly focused on the close ties between North Korea and Russia.

This makes Russia’s war against Ukraine acutely dangerous for South Korea. After all, Russia could supply North Korea with modern technology in return for the mass production of ammunition. This would make North Korea’s highly equipped army even stronger – at a time when its threats against the South are becoming increasingly aggressive. “Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine is not just a localized war,” Habeck said after the talks with the Prime Minister. “Concern in South Korea is growing.”

This is why Habeck increasingly regards South Korea as a close partner among the democratically-minded countries that support Ukraine. Although South Korea does not directly supply weapons to Ukraine, it is at least involved in the ring exchange, in which it supplies weapons to countries that directly supply Ukraine.

Beforehand, the Minister spent some time in a hot and dusty palace complex, listening to a German professor explain the initial contacts between Germany and Korea. What seemed like a sightseeing visit was actually a valuable introduction to the region’s geopolitical dynamics. The palace was deliberately destroyed during the Japanese occupation between 1910 and 1945 and is currently being gradually restored.

The Japanese occupiers had the Korean queen beheaded by assassins. Hearing such stories on the spot helps understand the irreconcilable relationship between the neighboring countries. So sweating in the hot and humid weather may even have been worth it.

Habeck also visited a quantum nanoscience research center. This was part of his mission to find alternatives to China in key fields. In this case, it is about research cooperation and access to advanced technologies. Germany does not want to be dependent on China (and preferably not too reliant on the United States either) for the next generation of future technology. It needs new partners. Like South Korea.

Overall, the Minister tried to breathe life into his mission of risk minimization during the visit. During the talks, he emphasized the strong interest of German companies in expanding their business in South Korea. Speaking to Han, he called for more cooperation with German SMEs.

One example should particularly please him as climate minister: The energy group RWE is currently trying to get a foot in the door for the construction of offshore wind farms. “The entire wind sector in South Korea is still surprisingly underdeveloped,” says David Jones, head of RWE Renewables in Seoul and head of the offshore division in Korea.

So far, nuclear power has been the big alternative to coal and oil. The country’s ambitious expansion targets are barely achievable. Therefore, Jones is hoping for a tailwind from the government if he wants to give the industry a boost in cooperation with local partners. So far, many projects have failed due to red tape. According to Jones, the construction of offshore wind farms is far less complicated in Europe.

On Friday, after a visit to the border with North Korea, he will continue his trip to China. Here, he will hold trade talks on Saturday. They will be characterized by contradictory goals, because Germany’s varying interests are intermingled with the EU’s activities:

His Chinese dialogue partners will be testing Habeck, who will be visiting Beijing for the first time: Is he a potential representative of Chinese interests in the EU like Olaf Scholz? Or is he as uncompromising as his party colleague and Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock? Is he embracing his traditional role as German Economy Minister, or will his actions be dominated by his Green Party influences?

Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un have signed a comprehensive strategic partnership treaty in Pyongyang. Putin traveled to North Korea on Wednesday for the first time in a quarter of a century to deepen relations personally.

At first glance, the new treaty appears to be tailored to current needs: Russia needs more ammunition for its war in Ukraine, and isolated North Korea has gained a powerful partner to ensure the security of the Kim regime. However, a closer look reveals that the scope of the agreement is much more far-reaching and could pose a threat to the security of the USA and Europe.

Firstly, the direct effects. North Korea’s state media published the treaty on Thursday. Article IV states that should one of the two countries “get into a state of war due to an armed aggression,” the other “shall immediately provide military and other assistance with all the means at its disposal.” As Russia is already at war, it can be assumed that North Korea will significantly step up its military support in the coming weeks and months.

The deliveries are already considerable: US intelligence agencies believe that Russia has received more than 10,000 shipping containers – the equivalent of around 260,000 tons – of ammunition or other military equipment from North Korea since September. In addition, Russian forces have fired several North Korean missiles at Ukraine, says Pak Jung, an insider expert on North Korea.

Pak, a long-time CIA analyst, has written a book about ruler Kim Jong-un and is now the deputy US special representative for North Korea. Pak clarifies: “North Korea is not doing this for free. There’s almost certainly things that North Korea wants in return, and we’re concerned about what might be going on to the other side. We also worry about what North Korea could be learning from Russia’s use of these weapons and ballistic missiles on the battlefield and how that might embolden or and help North Korea even further advance their weapons program.”

This brings us to the long-term consequences. Kim Jong-un has already spoken of an “alliance” between North Korea and Russia. Things are probably not quite there yet, but the specific points should be enough to raise concerns in the West. For example, Putin said in Pyongyang that Russia “does not rule out military-technical cooperation with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in accordance with the document signed today.”

Putin is being vague, leaving many questions unanswered:

North Korea’s interests are apparent. The Kim regime is working hard on its nuclear weapons and missile program. Everything is subordinated to this, with the result that while the population suffers hardship and hunger, Kim’s weapons experts have made remarkable progress. However, they have not yet been able to develop a warhead that can survive re-entry into the atmosphere. It is the missing piece of the puzzle that actually poses a serious threat to Europe and the United States. Russia has this technological know-how. But will it pass it on to Pyongyang?

Probably not. Or not yet. Because at the meeting between Putin and Kim in Pyongyang, there is also an invisible elephant in the room: China. Both Russia and North Korea need China’s support. Neither Putin nor Kim Jong-un can afford to antagonize Beijing’s ruler Xi Jinping. The leadership in Beijing will be watching closely to see how far the new partnership between Russia and North Korea progresses. Xi will certainly not tolerate the old Soviet-era strategy, when Pyongyang alternately played Beijing and Moscow off against each other.

The current “division of labor,” on the other hand, is very much in Beijing’s interest: China supplies Russia with what it needs to keep its war economy running. When it comes to direct arms supplies, however, Beijing is not (yet) prepared to cross a red line. “That’s why North Korea – which, unlike China, has no trade to lose with the West and does not want to present itself in international politics as a peace mediator or Europe’s favored partner – is now taking on the role of arms supplier,” Joel Atkinson, Professor of China Studies at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul, told Table.Briefings.

This division of labor reflects the big shared goal of North Korea, Russia and China: Their rejection of a Western-dominated world under the auspices of the United States.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg reacted with corresponding concern. “We need to be aware that authoritarian powers are aligning more and more. They are supporting each other in a way we haven’t seen before,” he said in Ottawa on Wednesday. North Korea had supplied Russia with “an enormous amount of ammunition,” while China and Iran were also supporting Russia militarily in the war against Ukraine.

For this reason, NATO intends to work more closely with its allies in the Asia-Pacific region. To this end, the heads of government of Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea have been invited to the NATO summit in Washington next month.

Meanwhile, Putin has traveled from North Korea to Vietnam, a country that is very flexible with its “bamboo policy.” Observers say potential arms deliveries are also on the agenda in Hanoi. In addition to Deputy Defense Minister Alexander Fomin, Putin’s delegation also includes the head of the Russian authority for military-technical cooperation, Dmitry Shugaev, and the director of the arms company Rosoboronexport, Alexander Mikheyev.

A recent investigation by the German non-profit site Correctiv, which examined the ties between professors at RWTH Aachen University and China, has reignited the debate about relations between German research institutions and the People’s Republic.

“The findings describe the tip of the iceberg. As far as investigative research is concerned, other countries, such as the UK and the United States, are now far ahead of us. It is high time that all universities in Germany were subjected to an independent investigation,” Andreas Fulda, political scientist and China expert at the University of Nottingham, demanded in response to a question from Table.Briefings.

In its report, the investigative team details several isolated cases of researchers at RWTH Aachen University maintaining ties to universities belonging to the “Seven Sons” or the National University for Defense Technology (NUDT). According to the Australian think tank ASPI, this is a group of seven Chinese universities listed as civilian universities but with close ties to the military and arms industry.

The report follows a series of similar investigations, such as an earlier one by Correctiv, the German newspaper FAZ, or US expert Jeffrey Stoff. All reports suggest that German academic institutions are, or at least were, too naive in their handling of cooperation with China. According to the latest Correctiv report, at least 19 of about 100 professors in the RWTH faculties of mechanical and electrical engineering are believed to have cooperated with researchers from the “Seven Sons” or NUDT.

Andreas Fulda says it cannot be assumed that RWTH is an isolated case. “Technical universities in the STEM fields are of particular interest to the Chinese Communist Party.” Findings from basic and applied research would help the Chinese party leadership better control the population with technological innovations and advance the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army.

In response to a question from Table.Briefings, a spokesperson for RWTH Aachen University explained that some of the examples referred to by Correctiv were years ago and that review mechanisms and sensitivity had since changed. They further argue that other publications fell into the open-access category anyway and concerned publicly accessible developments in global basic research.

“The report cannot name any examples of goods transfers prohibited under export control law. We take supervision in accordance with the existing rules very seriously and constantly scrutinize our mechanisms,” a spokesperson said. The RWTH explained that there was a long tradition of cooperation with China and correspondingly standardized processes, an extensive network and awareness-raising measures for researchers – ranging from onboarding to specific seminars.

Furthermore, RWTH’s China office in Beijing “provides additional information and on-site China expertise.” The University says that it is also in constant contact with research alliances, partner universities and security authorities on this topic. It is actively involved in thematic working groups at German and European universities on legal, ethical and security aspects of international research, often with a particular reference to China.

The Correctiv report also criticizes the practice of setting up limited liability companies for professors to raise third-party funds for application-oriented research in return for profitable contracts from China. This structure is common transfer practice in many scientific fields. However, unlike university collaborations, funds that flow from Chinese companies via professors’ limited liability companies, for example, are not recorded.

Based on the investigation, the German Association of University Professors and Lecturers (DHV) urges the German federal and state governments to provide adequate basic research funding. In an interview with Correctiv, DHV spokesperson Matthias Jaroch calls this the “most effective means” against possible financial influence. Without sufficient basic funding, universities would have to rely on alternative funding sources. Jaroch also calls for the greatest possible transparency and the disclosure of all professors’ cooperation agreements.

Walter Rosenthal, President of the German Rectors’ Conference (HRK), declined to comment explicitly on the cases at RWTH Aachen University. However, he points out that scientists who are employed at universities are required to obtain permission to work at start-ups. “To do this, they submit an application for secondary employment to their universities, which must include the scope of the activity.” The universities then must evaluate these applications. Approval could then be granted with conditions.

In the debate, the academic community repeatedly refers to academic freedom and university autonomy. Recently, Anja Steinbeck, spokesperson for the universities in the HRK, and Joybrato Mukherjee, President of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), expressed these sentiments in conversations with Table.Briefings. The general tenor was that the government should not interfere. However, both also emphasized the responsibility of the institutions to deal intensively with the topic and to establish awareness-raising and supervisory measures.

The DAAD also declined to comment on the RWTH Aachen University. However, the DAAD believes that “scientific cooperation with China should be realistic: This means that universities should sharpen their scientific interests in dealing with China, recognize opportunities and risks and develop or expand clear review procedures and processes for existing or future collaborations.” China expertise should always be developed and expanded independently, the DAAD said.

For Andreas Fulda, the Correctiv research shows “that we unfortunately cannot rely on academic self-governance.” Even if there are justified reservations about state interference for historical reasons: “We now urgently need clear and applicable state transparency rules. However, due to German federalism and the weakness of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, I think it is rather unlikely that decisive action will be taken.”

However, the German Education Ministry sees progress in terms of the scientific institutions taking responsibility. “The guidelines developed and review processes initiated by the scientific organizations and universities for cooperation with China are an important step,” a spokesperson told Table.Briefings. “In cooperation with the relevant authorities, we will continue to increase the information and awareness of universities and research institutions and support the development of independent China expertise.”

June 24, 2024; 4 a.m. CEST (10:00 a.m. Beijing time)

EU SME Center/European Chamber: Working Group meeting (online): China’s Payment Landscape and How to Navigate It More

25.06.2024, 12:30 Uhr

Confucius Institute Heidelberg, film matinée (on site): “Of Color and Ink” (Zhang Weiming) with the director in attendance More

June 25, 2024; 10 a.m. Beijing time

German Chamber of Commerce Machinery Day (in Suzhou): Powering the Future: Digitalization and Sustainability in the Smart Manufacturing Industry More

June 27, 2024; 10 a.m. CEST (4 p.m. Beijing time)

Dezan Shira & Associates , Webinar: Compliance in China: New Company Law Impacts on Foreign-Invested Enterprises (FIEs) from Legal, Financial, and Tax Perspectives More

June 27, 2024; 11 a.m. CEST (5 p.m. Beijing time)

Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Global China Conversations #33: How (differently) have Chinese Firms invested in and changed Africa? More

June 27, 2024; 2:30 p.m. CEST (8:30 p.m. Beijing time)

CNBW – Working Group Sino-German Corporate Communications (online) Navigating China’s E-Commerce Frontier: Insights and Strategies with Damian Maib More

July 1, 2024; 4 p.m. Beijing time

EU SME Center, SME Roundtable in Guangzhou: Insights into China’s Policy Updates More

A survey has found that 73 percent of Chinese EV manufacturers have experienced a drop in sales in the European market due to the EU investigation into state subsidies. The Chinese Chamber of Commerce in Brussels presented the survey on Wednesday in cooperation with the state-run China Economic Information Service. 67 percent of the companies stated that the EU investigation had affected their brand’s reputation. According to the Chamber of Commerce, the survey was conducted in May and April this year among more than 30 manufacturers and suppliers in the Chinese EV industry.

The survey found that the investigation had a negative impact on cooperation with European partners: 82 percent of respondents were less confident about future investments in Europe. Accordingly, 83 percent of the companies surveyed stated that European dealers and leasing companies were less optimistic about the prospects for cooperation. Around two-thirds (67 percent) of respondents said that the European market was still of crucial importance and that they wanted to build production facilities in Europe within the next five years.

In the report, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce criticizes the EU Commission’s actions and claims it has deliberately overestimated the market share of Chinese EVs in Europe. Last week, the Brussels authority announced extra tariffs of up to 38.1 percent on Chinese EVs. In response, Beijing announced an anti-dumping investigation into European pork earlier this week. Both sides repeatedly emphasized that they wanted to resolve the conflict through negotiations. ari

Polish President Andrzej Duda will pay a state visit to China from June 22 to June 26 at the invitation of Chinese President Xi Jinping. This was announced by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying on Thursday.

At the regular press conference of the Chinese Foreign Ministry, it was announced that Andrzej Duda would meet with several top Chinese politicians during his stay in China. In addition to Xi, these include Premier Li Qiang and the Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, Zhao Leji. cyb

How was the life of a high-ranking party functionary and revolutionary, who many Chinese observers claim became a market reformer after years of persecution by Mao while remaining an upstanding communist? The man in question is not Deng Xiaoping but Xi Zhongxun, who is even better known as the father of China’s now sole ruling Communist Party leader, Xi Jinping.

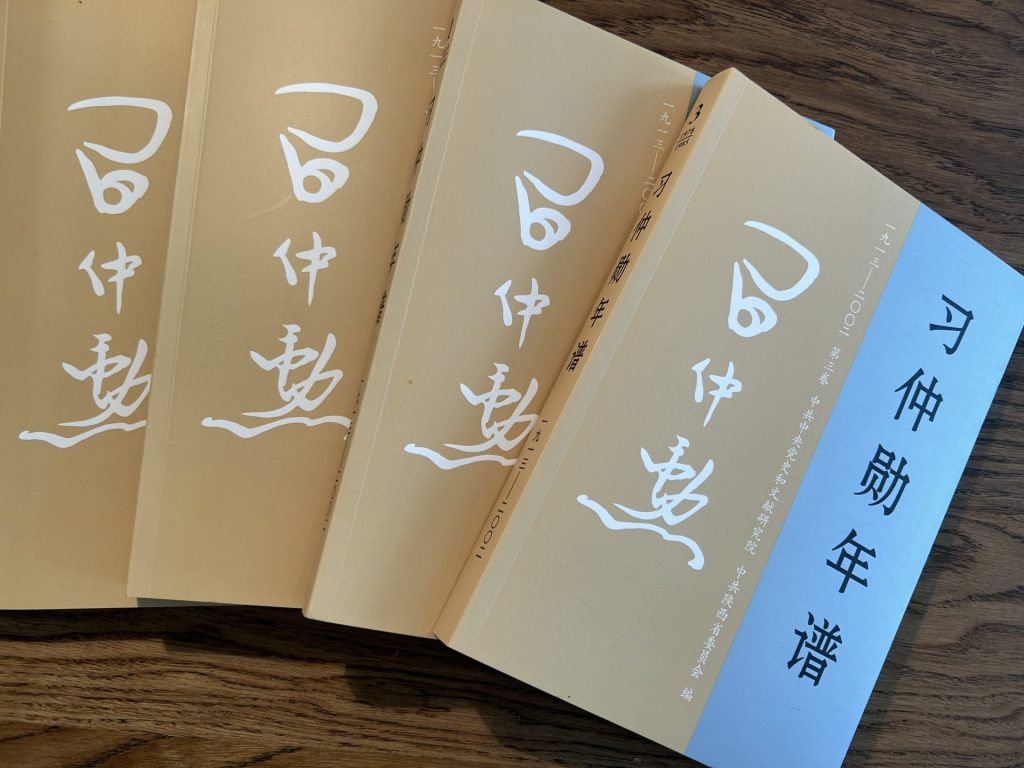

The massive four-volume, 1448-page chronicle of Xi Zhongxun (习仲勋年谱) promises to hold answers. It begins with his birth on October 15, 1913, and ends with his death on May 24, 2002. According to the news agency Xinhua, it is so important “that we can unite even more closely around comrade and Party core, Xi Jinping.” 更加紧密地团结在以习近平同志为核心的党中央周围.

When reading Chinese propaganda, it is important to read between the lines; when reading Party chronicles, you should pay attention to what they don’t tell you. When friends brought me this hefty biography, weighing more than two kilograms, I opened the page for February 25, 2001. Like a logbook, it reads: Xi Zhongxun writes a calligraphy for the Longmen traditional school: “A great place. Cradle of many Chinese talents.”

However, on that day, the then 88-year-old scribbled a much more significant dedication: To mark the tenth anniversary of the magazine “Yanhuang Chunqiu,” which, as a forum for internal Party debates, had dedicated itself to critically re-examining the past, he calligraphed: “Yanhuang Chunqiu is well-made.” The magazine’s publishing director and authors used to be high-ranking party officials loyal to Mao before they were unfairly persecuted by his tyranny.

That was precisely what happened to Xi. As a communist guerrilla leader in 1930s Shaanxi, he was instrumental in helping a grateful Mao and his Long March troops survive. He rose in Mao’s favor and later became vice premier of the People’s Republic. But then the Chairman, sensing conspiracies everywhere, put him on the hit list. During the Cultural Revolution, Xi was particularly brutally persecuted. His entire family fell from grace.

When I learned in 2015 that China’s leadership was planning to close the critical magazine, I asked the editor-in-chief, Yang Jisheng, about it. He showed me the calligraphy of Xi’s father in his office. “This will protect us,” he hoped.

Yang was wrong. Barely a year later, dogmatists in Xi Jinping’s employ launched polemical attacks against Yanhuang Chunqiu. They claimed that the magazine was defaming Mao and China’s system to “capsize the socialist boat of the People’s Republic.” The magazine was immediately seized, and the entire editorial team was fired. I happened to personally witness the “end of a liberal legend” by the ideologues’ coup. No wonder it is forbidden to even mention Xi Zhongxun’s calligraphy nowadays.

Despite all the censorship, the newly published chronicle remains a treasure trove for Party historians, who Beijing is increasingly denying access to archives. It also helps identify the contradictions in the personality of Xi Jinping, who was not always the ideological hardliner we know today. A letter he wrote to his father on his 88th birthday, dated October 15, 2001, has been published in full. It is partly known because China’s propaganda cites it as an example of Xi’s (Confucian) virtue of filial piety towards his father.

However, in the full letter, Xi also mentions other motives. He praises his father for “never having anyone persecuted throughout his life,” 一辈子没有整过人 and because he “never lied.” He also reminds him of the Cultural Revolution, during which his family was persecuted: “When people shouted at us on the street as ‘sons of dogs,’ I stood firm in my judgment. My father is a great hero.”

That sounds noble, but neither Xi Jinping nor his father are willing to critically reflect on Mao and his crimes. Both of them place the Party and the state before personal hardship. They do not see themselves as enlightened reformers and certainly not as liberal communists. Xi’s apple does not fall far from his father’s tree.

Hence, the new chronicle downplays Mao’s responsibility for his father’s persecution. Mao’s leftist followers, including intelligence chief Kang Sheng, are blamed for Xi Zhongxun losing Mao’s trust and being persecuted and exiled from 1962 to 1978. Their intrigues led the Chairman to believe in a conspiracy against him and an “anti-Mao clique” to which Xi Zhongxun belonged. He allegedly tried to manipulate the Party’s sentiment against Mao through a revolutionary novel about the guerrilla period, aiming to rehabilitate Mao’s once-defeated inner-party enemies.

Today, Xi Jinping has made any critical debate about Mao and especially his Cultural Revolution taboo. That is why the new chronicle is only allowed to cover the events of the worst years for Father Xi Zhongxun, from 1964 to 1977, until the fall of the Gang of Four, in just 21 of its almost 1500 pages. It recounts when and how often fanatical Red Guards violently abducted his father, who was working in a tractor factory in Luoyang, to their struggle and criticism sessions and tortured him for hours.

It gives a more factual account of Xi’s role as an effective reformer after his rehabilitation in 1978, whom Deng Xiaoping sent to Guangdong to support its modernization as provincial and Party leader. Many details about his help in politically rehabilitating tens of thousands of Guangdong officials who were victims of the Cultural Revolution or defusing a crisis surrounding the mass exodus of Chinese farmers to Hong Kong are new.

Xi Zhongxun also solved the injustice of the Canton dissidents sentenced to life. Under the pseudonym “Li Yizhe,” they gained worldwide fame for a sensational wall newspaper in which they called for democracy and the rule of law in 1974 while Mao was still alive. They were the forerunners of an extra-party opposition in China.

The book describes in detail how Xi was able to rehabilitate the authors of the wall newspapers and dozens of others involved in the case within his own Party bureaucracy and get them all released from prison. He met with the four LiYizhe oppositionists seven times in 1979 alone. However, he demanded they cease opposing the system and stop calling for Western-style “democracy and the legal system.”

He stood up for them, not because they opposed Mao and the system, but because they opposed Mao’s ultra-leftist followers. His father held Mao in high regard to the end and saw his own bitter fate as more of a random workplace accident. His son thinks no differently today.

The seemingly encyclopedic chronicle is not meant as historical source material. According to an unwritten rule, it is a status symbol of outstanding party leaders who have earned a place in the communist pantheon of Chinese revolutionaries since 1921.

So far, the honor of being portrayed in a dedicated Party chronicle has been bestowed upon less than a dozen former Communist Party bigwigs. Chen Jin, a deputy director of the Central Committee Research Office for Archival Documents, revealed in 2011 that apart from the unfinished chronicles of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, all other chronicles of eligible former CP leaders had been completed. 老一辈主要领导人官方传记基本出齐

But Xi Zhongxun is allowed to join this elite. His son probably played a role in this. For the time being, this chronicle is the final act with which Xi Jinping is righting the wrongs done to his father.

From 2002 to 2005, the Xi family erected a gigantic mausoleum for their father in his hometown of Fuping. Then, it was the state’s turn. Soon after his election as CP leader and president, Xi Jinping had his father’s 100th birthday celebrated in the Great Hall of the People on October 15, 2013. China’s postal service had to print special stamps for the occasion.

Coinciding with the planned publication of the new chronicle, state broadcaster CCTV aired its second six-part television documentary in December about Xi Zhongxun and a life dedicated to the Revolution. The series is aptly named 赤诚 “Total Devotion.” Here, too, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

Anton Melchers, the current CEO of Melchers Shanghai, will return to the German headquarters in Bremen in July as part of a strategic restructuring. His successor, Claus Toxvig, will take over the business in China.

Yudan Liu has been Director of China Desk at the auditing firm SW International in Frankfurt am Main since June. She was previously team leader of the China Desk at the banking consultancy Dornbach, also in Frankfurt.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Around 2006, China was the largest newspaper market in the world, and such newspaper kiosks were once commonplace in Shanghai’s urban landscape. Some of them were set up to create jobs for former employees of state-owned enterprises who were laid off as part of restructuring measures.

With the boom in online media, the number of kiosks across the country fell drastically, and the pandemic dealt a killing blow to many. In Shanghai, one of the last survivors on Wusong Road will finally close its shutters at the end of the year. Owner Jiang Jun will retire after three decades.