There is currently more geopolitical activity than since the fall of the Berlin Wall. With its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has put itself on the sidelines of world politics, at least for Western countries. Europe now seeks independence of Russian energy exports as quickly as possible. Germany has woken up to a world that punishes excessive proximity to autocratic regimes. Germany’s China policy could also soon see a change of course.

About a week and a half ago, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz himself spoke of a “turning point“. He announced major changes in his speech to the Bundestag. The fact that Berlin has made a 180-degree turn in its defense policy in such a short time – a policy that had been laid down decades ago – has certainly not gone unnoticed in Beijing, analyze Christiane Kuehl and Amelie Richter. This now leads to many unanswered questions in the Chinese capital.

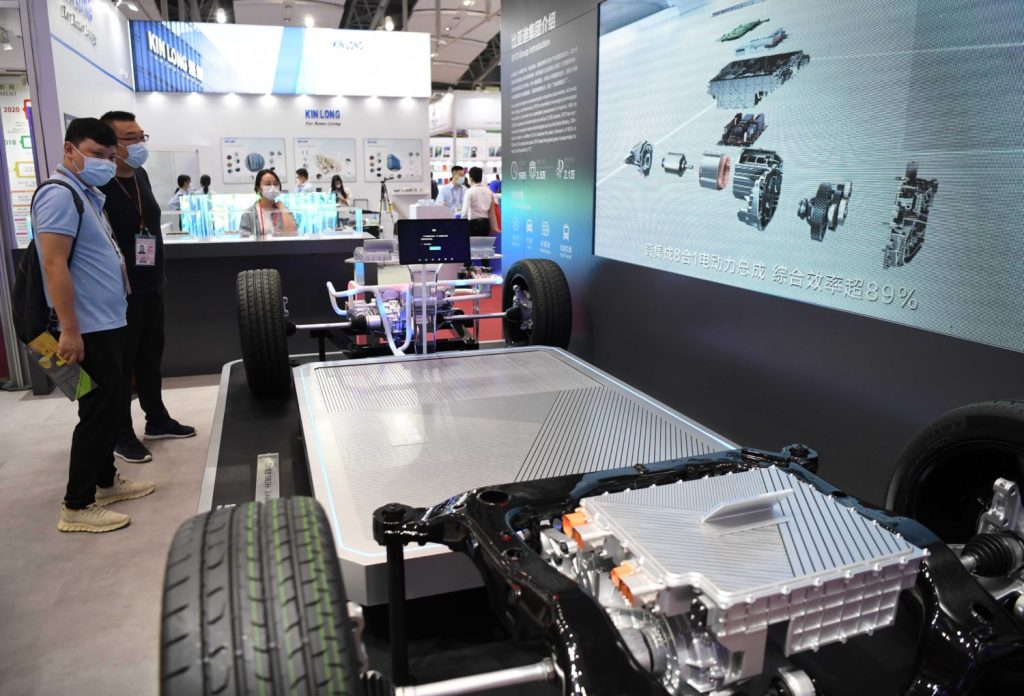

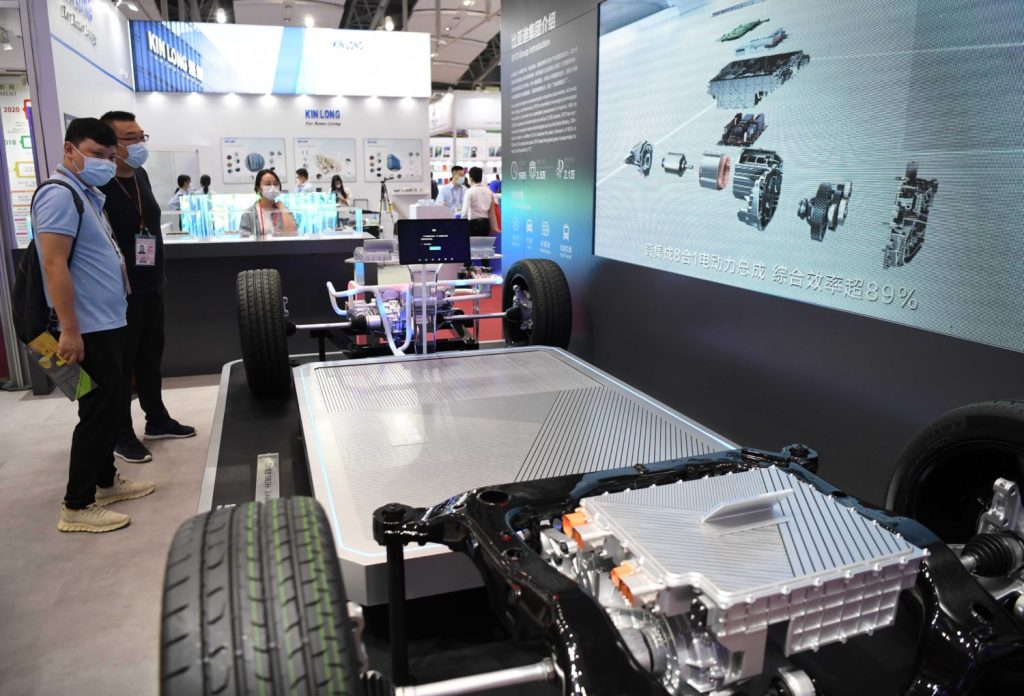

Meanwhile, politicians around the world are placing high hopes on electric cars. The electric drive is supposed to reduce emissions and help protect the climate. But the next shortage is already on the horizon: After the chip crisis, the automotive sector could soon face a battery shortage, as our Beijing team reports. Industry representatives hope to sell 5.5 million EVs on the Chinese market this year. But according to reports, there are only enough batteries to power 4.4 million cars. There is a risk of global supply shortages for EV batteries till 2030. So we may have to switch to bicycles or public transport to help protect the climate!

The China strategy of the new German traffic light coalition seems to be taking shape. The first details are already emerging and are causing debate from German China circles all the way to China itself. On Wednesday, the German newspaper Handelsblatt reported about a secret diplomatic cable from the German Embassy in Beijing. The report urged the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) to reconsider its projects in China. The state-owned GIZ primarily implements cooperations on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), for example in climate protection, the legal system or Industry 4.0.

The newspaper quotes from the report that projects “in areas where Germany and China are in strategic competition with each other” should be put to the test. A goal-oriented dialog is not always possible. It may be just a single report that is at issue here. But it is another signal that the new German government’s China policy could be about to take a turn.

This has also been noticed in China. Apparently, there is unease in Beijing about the “turning point” in German foreign policy, as proclaimed by Chancellor Olaf Scholz. EU sources in Beijing claim that the rapid change in German defense policy came as a “shock”. Berlin’s swing was perceived in China as a “game-changer” that no one in Beijing had expected. According to a report in the South China Morning Post, startled political scientists in Beijing are consulting German think tanks to find out what this turning point is all about.

Scholz recently announced a €100 billion special budget for the German Armed Forces during the Ukraine session of the Bundestag and vowed to provide the two percent of the gross domestic product long promised to NATO on defense with immediate effect. On the same day, Germany authorized arms shipments to Ukraine and supported the exclusion of Russian banks from the Swift system and the freezing of assets belonging to the Russian Central Bank in Europe. This would have been unthinkable just a few days earlier.

This turning point has certainly been noticed in China, says Pascal Abb, a researcher at the Leibniz Institute Hessian Foundation for Peace and Conflict Research (HSFK) in Frankfurt. This impression was also backed, among other things, from conversations with colleagues at Chinese think tanks.

With the financial boost for the Bundeswehr and arms deliveries to the conflict region of Ukraine, Germany has knocked down a pillar of its foreign and security policy that had remained unchanged for decades, says Abb. The fact that this happened in such a short time is now causing concern in Beijing that a change of thinking could also happen in other areas, estimates Abb, who focuses on China’s foreign policy and Chinese concepts of world order at the HSFK.

Until now, Germany was considered a state that cared more about market access for its car manufacturers than about geopolitics or human rights issues. China liked what it perceived as German pragmatism: separating economics from politics. Germany had previously been seen more as an economic policy player, says Abb, and encounters between the two sides had been “complementary rather than adversarial”. But with an expansion of defense policy, that could change.

Some of what awaits China was already foreshadowed in the election campaign and in the coalition agreement. During the election campaign, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock already called for a value-oriented foreign policy and called for a combination of “dialogue and toughness” in dealings with China. She is also relying more strongly than the previous government on a common EU line toward China. In previous years, however, Angela Merkel’s chancellery was usually responsible for China policy. Olaf Scholz has so far been seen more as a supporter of her course of economic cooperation. But all that has been, could now change.

The first changes are likely to show in the Foreign Ministry. It is currently drafting its new China strategy on Baerbock’s behest – and will certainly try to hold its own against the chancellor’s office in the process. “We’ve seen that Annalena Baerbock is a confident foreign minister, and the Foreign Office typically has a keen sense that economics and geopolitics are becoming increasingly intertwined,” says Jonathan Hackenbroich, an expert on foreign economic policy at the think tank European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

“The chancellor’s office will certainly take a more moderate position toward China,” Hackenbroich told China.Table. “But the important question is whether Scholz’s turning point refers to Europe and defense policy, or to the entire world order and thus also economic relations. China’s leverage over Germany would then of course be an important issue.” The leverage, that is its close economic ties, and the ever-increasing dependence of many major German companies on the Chinese market.

Abb and Hackenbroich believe that it will take some time before the new course in foreign policy is set. At present, of course, Berlin is primarily concerned with the crisis at hand, Hackenbroich says. “But there is obviously an awareness of the gravity of the changes.”

Regarding the Bundeswehr, Pascal Abb says, “The decisive question is in what larger foreign policy context these new capacities will be embedded.” In this regard, China had always favored closer EU cooperation toward strategic autonomy. The situation is different for transatlantic cooperation under US leadership, Abb believes. Should Germany, for example, use these new capacities to expand its involvement in the Indo-Pacific region, this would certainly be perceived negatively in Beijing, the expert is certain. Hackenbroich has a similar take: “The comparison between Ukraine and Taiwan comes up from time to time. It’s a different situation, but there are definitely some parallels.”

But the ECFR expert is certain of one thing: “The big question is whether the military turning point will also become a geo-economic turning point. That is the main question for German relations to China, which are mainly of economic nature.” It could very well be that the experience with the dependence of the German energy sector on Russia will prompt Berlin to take a new look at, for example, its possible dependence on the Chinese market, Hackenbroich says. “That’s something Beijing will be paying close attention to.” Amelie Richter/Christiane Kühl

Chinese buyers of EVs currently have to be very patient. Several manufacturers had to inform their customers about longer shipping times for new cars than they had originally promised. Chinese EV startup Xpeng first issued an apology to buyers in December and then again a few weeks ago for not being able to deliver its new P5 model on time. Tesla also reported delays in shipping out ordered Model 3s and Model Ys from its Shanghai plant.

The reason: In addition to the ongoing chip shortage, batteries for EVs are now also becoming scarce. “The EV market is growing at a torrid pace that keeps beating estimates by assemblers and component suppliers,” David Zhang, an automobiles industry researcher at the North China University of Technology, recently told Hong Kong newspaper South China Morning Post. “It will take time for key battery manufacturers to expand production capacity to meet demand,” said the researcher, who believes that the existing supply of batteries may only cover 4.4 million NEV vehicles in China this year.

This figure stands in stark contrast to the forecast by the Chinese automobile association CPCA, which expects 5.5 million shipped EVs for 2022. But even if the lack of batteries were to throw a wrench into the CPCA’s optimistic calculations, more than four million EVs sold would still be a substantial increase over the record year of 2021, when just under three million EVs were sold in China.

However, it is also clear that it will be impossible to meet the huge demand for the time being. The problems are likely to persist. A huge run on EVs is expected in the coming years, not only in China but in all major car markets around the world. But it will probably not be possible to produce them in sufficiently high quantities due to battery shortages.

A study by the German research institute Center Automotive Research (CAR) also came to the same conclusion last year. According to its study, 18.7 million fewer EVs could be produced globally between 2022 and 2029 than demand would allow due to the battery shortage. According to the study, a balance between supply and demand could not be achieved until 2030. The global car market in this decade is characterized by “two bottleneck factors,” deduces car expert Ferdinand Dudenhoeffer, head of the CAR Institute. On the one hand, there is a shortage of semiconductors, which will have an impact until early 2023. After that, problems with battery cells would increase.

While the current problems this winter are largely attributable to the fact that Chinese battery manufacturers underestimated the growth dynamics of the EV market and failed to increase their capacities in time, the battery shortage is likely to worsen in the coming years, mainly due to a shortage of the key raw material lithium.

In the past year alone, the lithium price has quadrupled and is currently continuing its climb – driven in part by uncertainties related to the Ukraine crisis, which is causing many commodity prices to skyrocket. “Rising prices of nickel, lithium and other materials threaten to slow and even temporarily reverse the long-term trend of falling costs of batteries,” believes Gregory Miller, an analyst at industry forecaster Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. Miller predicts that this year, the average price of lithium-ion battery cells could rise year-over-year for the first time ever. If carmakers pass on these costs, customers will not only have to wait longer for their new EV but will likely pay significantly higher prices for them as well.

The impending lithium shortage is currently also on the minds of political Beijing. Zeng Yuqun, Chairman of the largest Chinese battery manufacturer CATL, brought the topic as a deputy on the agenda of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, which is currently meeting in parallel to the People’s Congress in Beijing in the Great Hall of the People.

Zeng urged the Chinese government to strengthen China’s lithium supply chains in the face of shortages, as demand has intensified with the increasing introduction of EVs. China dominates lithium refining and industrial processes necessary to manufacture a battery. What it lacks, however, is a sufficient supply of its own lithium stocks. Here, China relies primarily on imports from countries such as Australia, Chile and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Joern Petring/Gregor Koppenburg

United States Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo has warned Chinese companies not to defy sanctions against Russia. The United States could “essentially shut” down Chinese chipmaker SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation) or other companies that continue to supply chips or high-tech goods to Russia, Raimondo told The New York Times. According to the report, the United States could cut off Chinese companies from US equipment and software required to manufacture their products. Russia sources about 70 percent of its chip supply from China (China.Table reported).

The US, EU and other Western countries had also imposed sanctions affecting the tech sector as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to the New York Times, the US export controls do not only apply to US manufacturers. Companies worldwide are affected if they use US software or technology to manufacture their products.

Russia “is certainly going to be courting other countries to do an end run around our sanctions and export controls,” Raimondo reportedly said. She added that the US could take “devastating” action against Chinese companies that defy Russian sanctions

Currently, Chinese companies and banks are still proceeding cautiously and observing Western sanctions against Russia. Some banks from the People’s Republic have stopped financing commodity imports from Russia (China.Table reported). Simultaneously, Beijing announced that Russian-Chinese trade will continue normally. China rejects Western sanctions against Russia. nib

China was responsible for a good third of global CO2 emissions last year. That is according to new figures from the International Energy Agency. These figures show that global emissions rose to a record level in 2021. After falling in the first year of the Covid pandemic, emissions rose all the more sharply in its second year. Although renewables saw their largest annual growth, more coal was burned than ever before. This climate-damaging energy source accounted for more than 40 percent of the total growth in global CO2 emissions in 2021.

CO2 emissions climbed faster in China than they fell in the rest of the world. The economic recovery in the People’s Republic following the Covid pandemic is particularly energy-intensive. Power demand increased by ten percent, outpacing economic growth of 8.4 percent. With demand growing so fast, the expansion of renewable energy could not keep pace. 56 percent of the increase in power demand was met by coal. Experts also expect China’s coal consumption and CO2 emissions to rise this year (China.Table reported).

The People’s Republic accounted for most of the global increase in emissions in the power and heat sector between 2019 and 2021. A small decrease in the rest of the world was not enough to offset the increase in China, resulting in an increase in emissions from the sector. In the industrial sector, however, the People’s Republic consumed less coal than in the pre-Covid year 2019.

China emitted 8.4 metric tons of CO2 per capita last year. In the USA, this figure is 14 metric tons, and in the EU, 6 metric tons. China has the highest emission intensity of GDP among major economies. Thus, to generate $1,000, China emits the most greenhouse gas. The emission intensity of China’s GDP has indeed dropped by 40 percent since 2000. However, the tremendous growth of the Chinese economy has caused absolute emissions to rise sharply. nib

China has announced humanitarian aid for Ukraine – but is limiting it to the small amount of ¥5 million (€720,000). Ukraine has requested “food and daily necessities,” a government spokesman said on Wednesday. Only supplying a small amount is in line with China’s deliberately ambiguous signals in the conflict. China has shown concern about the war on the one hand, but at the same time has reiterated its loyalty to Russia. fin

A member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (PCC) has proposed a law to promote the “reunification” with Taiwan. It would mandate state institutions to work toward the island’s “return to the motherland.” The proposal was put forward by MP Zhang Lianqi. The PCC can be described as the advisory chamber of the Chinese parliament. Along with the National People’s Congress, it is the other half of the “two sessions” 两会 currently convening in Beijing.

An anti-secession law has been in effect since 2005. It prohibits all efforts aimed at Taiwanese independence. Zhang now argues that the old law is too passive. The time is ripe to actively work toward “reunification,” he said. Zhang presented the draft law in the propaganda newspaper Global Times ahead of the start of the session.

Taiwan was never formally part of the People’s Republic. This would make the process not a reunification but an annexation from Taiwan’s perspective. The Global Times puts the proposal in the context of the arrival of an official American delegation to Taiwan. Thus, an escalation away from the status quo is currently taking place.

Fittingly, Taiwan followed up on Wednesday with a demand to participate in economic negotiations as part of the US government’s planned Indo-Pacific strategy. John Deng, Taiwan’s chief trade negotiator, made the proposal at an event hosted by the US think tank Brookings Institution. Participation in international structures strengthens Taiwan’s perception as a state in its own right. fin

Washington, London, Beijing, Brussels and now Berlin – Andrew Small has spent most of the past 20 years in power centers around the world. Currently, the US American is a Senior Transatlantic Fellow with the Asia Program of the German Marshall Fund of the United States – a program that he helped launch in 2006. His research focuses on relations between the People’s Republic of China and the United States and Europe, respectively, as well as on Chinese foreign and economic policy in general. It all began with a trip to China as a young adult.

“My first contact with China was as a teacher in Guangzhou in the late 1990s. That was before I went to university,” he recalls. “The first thing that drew me was the documentary about the Three Gorges Dam and the upcoming changes in the Yangtze River Valley. So the first thing I wanted to do was go out and see the China that was about to disappear.”

Small returned in the early 2000s, but by then, he was already working at a think tank in London. At that time, he realized that the think tanks were still focusing too much on the current state of domestic policy in the People’s Republic, but that there was no real outlook on the country’s growing global role, says Small.

He immersed himself deeper and deeper into bilateral relations between Europe and China, including accompanying exchanges between government delegations. ” In the process, I worked closely with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and decided that I wanted to work from Beijing rather than London. I moved there in 2005 and spent a couple of years in Beijing,” Small says. He was one of the few foreign think tank employees and thus had carved out his own little niche. Then, when organizations from the United States slowly wanted to set up their Beijing offices, there was no way around Small.

It often seems as if many players in the political arena have formed their own opinions about China by now. So where does that leave the role of think tanks and experts? “I think the influence of the people who understand the subject is very high, especially in the China context. I’m still struck by how dependent political leaders are on the experts,” Small says. Much of the work happens behind closed doors, partly due to the nature of the People’s Republic. The challenge for experts like Small is to use the knowledge gained about China and translate it into a trade or security policy context that will find an open ear among decision-makers.

So what is next for Small? He’s working on finishing his second book, which is currently taking up a lot of his time, he explains. “The book is basically about how this rift between China and most democratic powers came about,” he says. “The book deliberately does not look through the US-China prism. Instead, it deals with how the Chinese system ended up in a situation of rivalry and competition with the democratic, liberal and free-market framework.”

Once finished, Small will then return fully to the think tank work that has so long defined his career path, which is strongly tied to China. Constantin Eckner

Kaher Kazem has been appointed by General Motors as the new Executive Vice President of SAIC-GM. The GM joint venture in China is responsible for manufacturing and marketing the Buick, Cadillac and Chevrolet brands. Kazem, who currently holds the position of President and CEO of GM Korea, will take over the top management position of SAIC-GM in Shanghai starting June 1.

Lu Kang is the new Chinese ambassador to Indonesia. The former ministry spokesman succeeds Xiao Qian.

He Rulong has begun his post as China’s new ambassador to Iceland. He arrived in Reykjavík at the end of February, according to the Chinese Foreign Ministry. He succeeds Jin Zhijian.

Due to the Covid situation, US fast-food giant McDonald’s plans to temporarily close 38 stores in Hong Kong. Another 90 of the chain’s stores are also to close earlier than normal. In a Facebook post, McDonald’s explained that there were “unprecedented difficulties” due to a lack of workforce and supplies. The fast-food chain operates a total of 245 stores in the city. In addition to McDonald’s, other restaurant chains, including Pizza Hut, have also shortened their business hours due to the COVID-19 surge.

There is currently more geopolitical activity than since the fall of the Berlin Wall. With its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has put itself on the sidelines of world politics, at least for Western countries. Europe now seeks independence of Russian energy exports as quickly as possible. Germany has woken up to a world that punishes excessive proximity to autocratic regimes. Germany’s China policy could also soon see a change of course.

About a week and a half ago, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz himself spoke of a “turning point“. He announced major changes in his speech to the Bundestag. The fact that Berlin has made a 180-degree turn in its defense policy in such a short time – a policy that had been laid down decades ago – has certainly not gone unnoticed in Beijing, analyze Christiane Kuehl and Amelie Richter. This now leads to many unanswered questions in the Chinese capital.

Meanwhile, politicians around the world are placing high hopes on electric cars. The electric drive is supposed to reduce emissions and help protect the climate. But the next shortage is already on the horizon: After the chip crisis, the automotive sector could soon face a battery shortage, as our Beijing team reports. Industry representatives hope to sell 5.5 million EVs on the Chinese market this year. But according to reports, there are only enough batteries to power 4.4 million cars. There is a risk of global supply shortages for EV batteries till 2030. So we may have to switch to bicycles or public transport to help protect the climate!

The China strategy of the new German traffic light coalition seems to be taking shape. The first details are already emerging and are causing debate from German China circles all the way to China itself. On Wednesday, the German newspaper Handelsblatt reported about a secret diplomatic cable from the German Embassy in Beijing. The report urged the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) to reconsider its projects in China. The state-owned GIZ primarily implements cooperations on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), for example in climate protection, the legal system or Industry 4.0.

The newspaper quotes from the report that projects “in areas where Germany and China are in strategic competition with each other” should be put to the test. A goal-oriented dialog is not always possible. It may be just a single report that is at issue here. But it is another signal that the new German government’s China policy could be about to take a turn.

This has also been noticed in China. Apparently, there is unease in Beijing about the “turning point” in German foreign policy, as proclaimed by Chancellor Olaf Scholz. EU sources in Beijing claim that the rapid change in German defense policy came as a “shock”. Berlin’s swing was perceived in China as a “game-changer” that no one in Beijing had expected. According to a report in the South China Morning Post, startled political scientists in Beijing are consulting German think tanks to find out what this turning point is all about.

Scholz recently announced a €100 billion special budget for the German Armed Forces during the Ukraine session of the Bundestag and vowed to provide the two percent of the gross domestic product long promised to NATO on defense with immediate effect. On the same day, Germany authorized arms shipments to Ukraine and supported the exclusion of Russian banks from the Swift system and the freezing of assets belonging to the Russian Central Bank in Europe. This would have been unthinkable just a few days earlier.

This turning point has certainly been noticed in China, says Pascal Abb, a researcher at the Leibniz Institute Hessian Foundation for Peace and Conflict Research (HSFK) in Frankfurt. This impression was also backed, among other things, from conversations with colleagues at Chinese think tanks.

With the financial boost for the Bundeswehr and arms deliveries to the conflict region of Ukraine, Germany has knocked down a pillar of its foreign and security policy that had remained unchanged for decades, says Abb. The fact that this happened in such a short time is now causing concern in Beijing that a change of thinking could also happen in other areas, estimates Abb, who focuses on China’s foreign policy and Chinese concepts of world order at the HSFK.

Until now, Germany was considered a state that cared more about market access for its car manufacturers than about geopolitics or human rights issues. China liked what it perceived as German pragmatism: separating economics from politics. Germany had previously been seen more as an economic policy player, says Abb, and encounters between the two sides had been “complementary rather than adversarial”. But with an expansion of defense policy, that could change.

Some of what awaits China was already foreshadowed in the election campaign and in the coalition agreement. During the election campaign, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock already called for a value-oriented foreign policy and called for a combination of “dialogue and toughness” in dealings with China. She is also relying more strongly than the previous government on a common EU line toward China. In previous years, however, Angela Merkel’s chancellery was usually responsible for China policy. Olaf Scholz has so far been seen more as a supporter of her course of economic cooperation. But all that has been, could now change.

The first changes are likely to show in the Foreign Ministry. It is currently drafting its new China strategy on Baerbock’s behest – and will certainly try to hold its own against the chancellor’s office in the process. “We’ve seen that Annalena Baerbock is a confident foreign minister, and the Foreign Office typically has a keen sense that economics and geopolitics are becoming increasingly intertwined,” says Jonathan Hackenbroich, an expert on foreign economic policy at the think tank European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

“The chancellor’s office will certainly take a more moderate position toward China,” Hackenbroich told China.Table. “But the important question is whether Scholz’s turning point refers to Europe and defense policy, or to the entire world order and thus also economic relations. China’s leverage over Germany would then of course be an important issue.” The leverage, that is its close economic ties, and the ever-increasing dependence of many major German companies on the Chinese market.

Abb and Hackenbroich believe that it will take some time before the new course in foreign policy is set. At present, of course, Berlin is primarily concerned with the crisis at hand, Hackenbroich says. “But there is obviously an awareness of the gravity of the changes.”

Regarding the Bundeswehr, Pascal Abb says, “The decisive question is in what larger foreign policy context these new capacities will be embedded.” In this regard, China had always favored closer EU cooperation toward strategic autonomy. The situation is different for transatlantic cooperation under US leadership, Abb believes. Should Germany, for example, use these new capacities to expand its involvement in the Indo-Pacific region, this would certainly be perceived negatively in Beijing, the expert is certain. Hackenbroich has a similar take: “The comparison between Ukraine and Taiwan comes up from time to time. It’s a different situation, but there are definitely some parallels.”

But the ECFR expert is certain of one thing: “The big question is whether the military turning point will also become a geo-economic turning point. That is the main question for German relations to China, which are mainly of economic nature.” It could very well be that the experience with the dependence of the German energy sector on Russia will prompt Berlin to take a new look at, for example, its possible dependence on the Chinese market, Hackenbroich says. “That’s something Beijing will be paying close attention to.” Amelie Richter/Christiane Kühl

Chinese buyers of EVs currently have to be very patient. Several manufacturers had to inform their customers about longer shipping times for new cars than they had originally promised. Chinese EV startup Xpeng first issued an apology to buyers in December and then again a few weeks ago for not being able to deliver its new P5 model on time. Tesla also reported delays in shipping out ordered Model 3s and Model Ys from its Shanghai plant.

The reason: In addition to the ongoing chip shortage, batteries for EVs are now also becoming scarce. “The EV market is growing at a torrid pace that keeps beating estimates by assemblers and component suppliers,” David Zhang, an automobiles industry researcher at the North China University of Technology, recently told Hong Kong newspaper South China Morning Post. “It will take time for key battery manufacturers to expand production capacity to meet demand,” said the researcher, who believes that the existing supply of batteries may only cover 4.4 million NEV vehicles in China this year.

This figure stands in stark contrast to the forecast by the Chinese automobile association CPCA, which expects 5.5 million shipped EVs for 2022. But even if the lack of batteries were to throw a wrench into the CPCA’s optimistic calculations, more than four million EVs sold would still be a substantial increase over the record year of 2021, when just under three million EVs were sold in China.

However, it is also clear that it will be impossible to meet the huge demand for the time being. The problems are likely to persist. A huge run on EVs is expected in the coming years, not only in China but in all major car markets around the world. But it will probably not be possible to produce them in sufficiently high quantities due to battery shortages.

A study by the German research institute Center Automotive Research (CAR) also came to the same conclusion last year. According to its study, 18.7 million fewer EVs could be produced globally between 2022 and 2029 than demand would allow due to the battery shortage. According to the study, a balance between supply and demand could not be achieved until 2030. The global car market in this decade is characterized by “two bottleneck factors,” deduces car expert Ferdinand Dudenhoeffer, head of the CAR Institute. On the one hand, there is a shortage of semiconductors, which will have an impact until early 2023. After that, problems with battery cells would increase.

While the current problems this winter are largely attributable to the fact that Chinese battery manufacturers underestimated the growth dynamics of the EV market and failed to increase their capacities in time, the battery shortage is likely to worsen in the coming years, mainly due to a shortage of the key raw material lithium.

In the past year alone, the lithium price has quadrupled and is currently continuing its climb – driven in part by uncertainties related to the Ukraine crisis, which is causing many commodity prices to skyrocket. “Rising prices of nickel, lithium and other materials threaten to slow and even temporarily reverse the long-term trend of falling costs of batteries,” believes Gregory Miller, an analyst at industry forecaster Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. Miller predicts that this year, the average price of lithium-ion battery cells could rise year-over-year for the first time ever. If carmakers pass on these costs, customers will not only have to wait longer for their new EV but will likely pay significantly higher prices for them as well.

The impending lithium shortage is currently also on the minds of political Beijing. Zeng Yuqun, Chairman of the largest Chinese battery manufacturer CATL, brought the topic as a deputy on the agenda of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, which is currently meeting in parallel to the People’s Congress in Beijing in the Great Hall of the People.

Zeng urged the Chinese government to strengthen China’s lithium supply chains in the face of shortages, as demand has intensified with the increasing introduction of EVs. China dominates lithium refining and industrial processes necessary to manufacture a battery. What it lacks, however, is a sufficient supply of its own lithium stocks. Here, China relies primarily on imports from countries such as Australia, Chile and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Joern Petring/Gregor Koppenburg

United States Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo has warned Chinese companies not to defy sanctions against Russia. The United States could “essentially shut” down Chinese chipmaker SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation) or other companies that continue to supply chips or high-tech goods to Russia, Raimondo told The New York Times. According to the report, the United States could cut off Chinese companies from US equipment and software required to manufacture their products. Russia sources about 70 percent of its chip supply from China (China.Table reported).

The US, EU and other Western countries had also imposed sanctions affecting the tech sector as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to the New York Times, the US export controls do not only apply to US manufacturers. Companies worldwide are affected if they use US software or technology to manufacture their products.

Russia “is certainly going to be courting other countries to do an end run around our sanctions and export controls,” Raimondo reportedly said. She added that the US could take “devastating” action against Chinese companies that defy Russian sanctions

Currently, Chinese companies and banks are still proceeding cautiously and observing Western sanctions against Russia. Some banks from the People’s Republic have stopped financing commodity imports from Russia (China.Table reported). Simultaneously, Beijing announced that Russian-Chinese trade will continue normally. China rejects Western sanctions against Russia. nib

China was responsible for a good third of global CO2 emissions last year. That is according to new figures from the International Energy Agency. These figures show that global emissions rose to a record level in 2021. After falling in the first year of the Covid pandemic, emissions rose all the more sharply in its second year. Although renewables saw their largest annual growth, more coal was burned than ever before. This climate-damaging energy source accounted for more than 40 percent of the total growth in global CO2 emissions in 2021.

CO2 emissions climbed faster in China than they fell in the rest of the world. The economic recovery in the People’s Republic following the Covid pandemic is particularly energy-intensive. Power demand increased by ten percent, outpacing economic growth of 8.4 percent. With demand growing so fast, the expansion of renewable energy could not keep pace. 56 percent of the increase in power demand was met by coal. Experts also expect China’s coal consumption and CO2 emissions to rise this year (China.Table reported).

The People’s Republic accounted for most of the global increase in emissions in the power and heat sector between 2019 and 2021. A small decrease in the rest of the world was not enough to offset the increase in China, resulting in an increase in emissions from the sector. In the industrial sector, however, the People’s Republic consumed less coal than in the pre-Covid year 2019.

China emitted 8.4 metric tons of CO2 per capita last year. In the USA, this figure is 14 metric tons, and in the EU, 6 metric tons. China has the highest emission intensity of GDP among major economies. Thus, to generate $1,000, China emits the most greenhouse gas. The emission intensity of China’s GDP has indeed dropped by 40 percent since 2000. However, the tremendous growth of the Chinese economy has caused absolute emissions to rise sharply. nib

China has announced humanitarian aid for Ukraine – but is limiting it to the small amount of ¥5 million (€720,000). Ukraine has requested “food and daily necessities,” a government spokesman said on Wednesday. Only supplying a small amount is in line with China’s deliberately ambiguous signals in the conflict. China has shown concern about the war on the one hand, but at the same time has reiterated its loyalty to Russia. fin

A member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (PCC) has proposed a law to promote the “reunification” with Taiwan. It would mandate state institutions to work toward the island’s “return to the motherland.” The proposal was put forward by MP Zhang Lianqi. The PCC can be described as the advisory chamber of the Chinese parliament. Along with the National People’s Congress, it is the other half of the “two sessions” 两会 currently convening in Beijing.

An anti-secession law has been in effect since 2005. It prohibits all efforts aimed at Taiwanese independence. Zhang now argues that the old law is too passive. The time is ripe to actively work toward “reunification,” he said. Zhang presented the draft law in the propaganda newspaper Global Times ahead of the start of the session.

Taiwan was never formally part of the People’s Republic. This would make the process not a reunification but an annexation from Taiwan’s perspective. The Global Times puts the proposal in the context of the arrival of an official American delegation to Taiwan. Thus, an escalation away from the status quo is currently taking place.

Fittingly, Taiwan followed up on Wednesday with a demand to participate in economic negotiations as part of the US government’s planned Indo-Pacific strategy. John Deng, Taiwan’s chief trade negotiator, made the proposal at an event hosted by the US think tank Brookings Institution. Participation in international structures strengthens Taiwan’s perception as a state in its own right. fin

Washington, London, Beijing, Brussels and now Berlin – Andrew Small has spent most of the past 20 years in power centers around the world. Currently, the US American is a Senior Transatlantic Fellow with the Asia Program of the German Marshall Fund of the United States – a program that he helped launch in 2006. His research focuses on relations between the People’s Republic of China and the United States and Europe, respectively, as well as on Chinese foreign and economic policy in general. It all began with a trip to China as a young adult.

“My first contact with China was as a teacher in Guangzhou in the late 1990s. That was before I went to university,” he recalls. “The first thing that drew me was the documentary about the Three Gorges Dam and the upcoming changes in the Yangtze River Valley. So the first thing I wanted to do was go out and see the China that was about to disappear.”

Small returned in the early 2000s, but by then, he was already working at a think tank in London. At that time, he realized that the think tanks were still focusing too much on the current state of domestic policy in the People’s Republic, but that there was no real outlook on the country’s growing global role, says Small.

He immersed himself deeper and deeper into bilateral relations between Europe and China, including accompanying exchanges between government delegations. ” In the process, I worked closely with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and decided that I wanted to work from Beijing rather than London. I moved there in 2005 and spent a couple of years in Beijing,” Small says. He was one of the few foreign think tank employees and thus had carved out his own little niche. Then, when organizations from the United States slowly wanted to set up their Beijing offices, there was no way around Small.

It often seems as if many players in the political arena have formed their own opinions about China by now. So where does that leave the role of think tanks and experts? “I think the influence of the people who understand the subject is very high, especially in the China context. I’m still struck by how dependent political leaders are on the experts,” Small says. Much of the work happens behind closed doors, partly due to the nature of the People’s Republic. The challenge for experts like Small is to use the knowledge gained about China and translate it into a trade or security policy context that will find an open ear among decision-makers.

So what is next for Small? He’s working on finishing his second book, which is currently taking up a lot of his time, he explains. “The book is basically about how this rift between China and most democratic powers came about,” he says. “The book deliberately does not look through the US-China prism. Instead, it deals with how the Chinese system ended up in a situation of rivalry and competition with the democratic, liberal and free-market framework.”

Once finished, Small will then return fully to the think tank work that has so long defined his career path, which is strongly tied to China. Constantin Eckner

Kaher Kazem has been appointed by General Motors as the new Executive Vice President of SAIC-GM. The GM joint venture in China is responsible for manufacturing and marketing the Buick, Cadillac and Chevrolet brands. Kazem, who currently holds the position of President and CEO of GM Korea, will take over the top management position of SAIC-GM in Shanghai starting June 1.

Lu Kang is the new Chinese ambassador to Indonesia. The former ministry spokesman succeeds Xiao Qian.

He Rulong has begun his post as China’s new ambassador to Iceland. He arrived in Reykjavík at the end of February, according to the Chinese Foreign Ministry. He succeeds Jin Zhijian.

Due to the Covid situation, US fast-food giant McDonald’s plans to temporarily close 38 stores in Hong Kong. Another 90 of the chain’s stores are also to close earlier than normal. In a Facebook post, McDonald’s explained that there were “unprecedented difficulties” due to a lack of workforce and supplies. The fast-food chain operates a total of 245 stores in the city. In addition to McDonald’s, other restaurant chains, including Pizza Hut, have also shortened their business hours due to the COVID-19 surge.