China’s one-child policy is one of the biggest social interventions by a government in the post-war period. The result is well known: China has successfully curbed the dynamic growth of its population. However, the consequences of the government’s birth control policy are so immense that it has long since become a massive problem. The demographic trend is alarming, and the consequences are dramatic.

Beijing wants to use Chinese pragmatism to reverse the trend. Many women of childbearing age receive telephone calls from their neighborhood committee encouraging them to become pregnant. The Communist Party naturally provides the recommended vitamins for expectant mothers free of charge.

The past has shown that the government has indeed managed to decisively intervene in population growth – if necessary through forced abortions or forced sterilizations. But how will the government get its citizens to have sex at the right time, wonders Angela Köckritz.

China applies a different kind of influence in the Philippines. Beijing attempts to persuade the country’s decision-makers to adopt a pro-China stance. To this end, it relies on investments and manipulation tactics. The authors of today’s opinion piece recommend that the West, particularly the US, should offer the Philippines alternatives to prevent the country from becoming more authoritarian: strategic aid, for example. This would not only strengthen Philippine sovereignty, but also strengthen America’s network of alliances in the Indo-Pacific.

Recently, many married Chinese women in their twenties and thirties have been receiving calls from their neighborhood committees. “When was the last time you had your period?” the person on the other end of the line wants to know. Or: “Are you planning to have a baby?” Or: “Your child is almost two years old now. You could get pregnant again.” You are welcome to pick up free folic acid tablets from the neighborhood committee. A small gift from the party. Doctors recommend that women who want to have children take the vitamin to prevent birth defects.

The calls happen very regularly – in the obvious hope of not letting any ovulation go to waste. They reveal the desperation with which the Chinese government is trying to tackle the huge demographic crisis. According to the latest United Nations forecast, China is expected to lose half of its population by the end of the century, making it the largest population loss in the world.

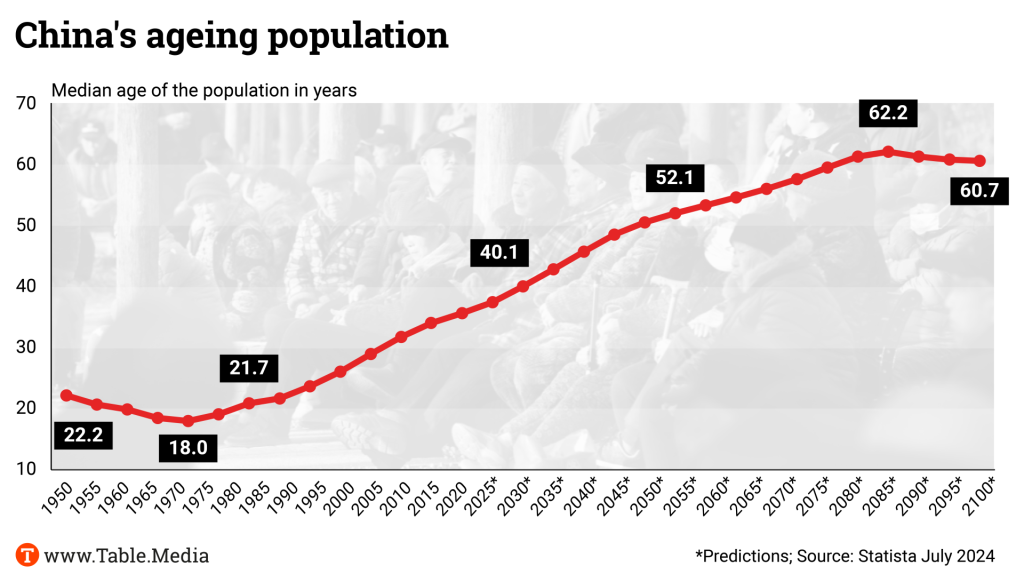

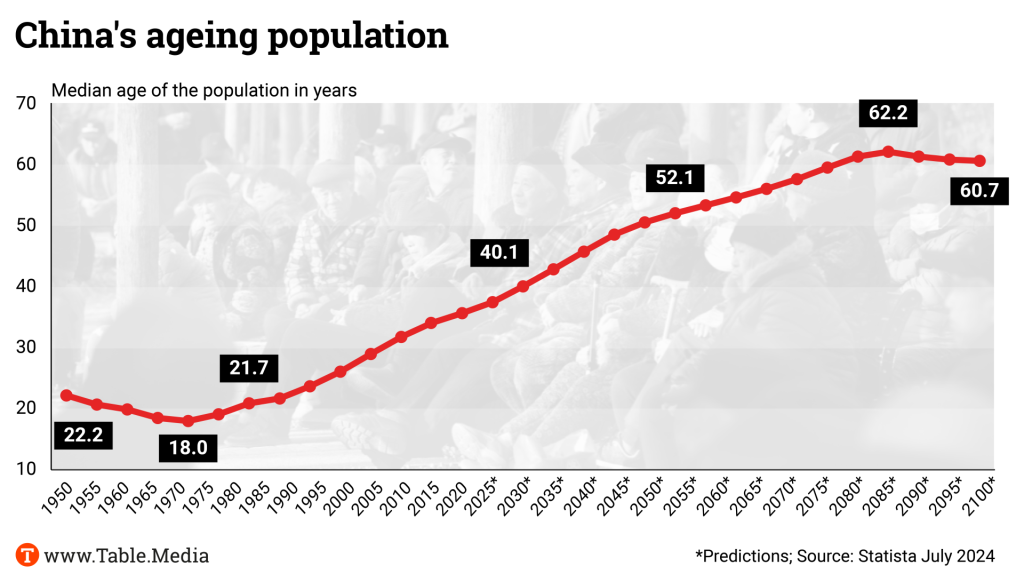

In 2100, only around 550 million people could still be living in China, which would be the same number as in the 1950s. The only difference is that the Chinese will be much older then. In 1950, the average Chinese person was around 22 years old. The same as in 1985. In 2050, the average age will rise to 52. In 2085, it is expected to be 62.

The Chinese government is in the eye of the hurricane, as the population is set to decline dramatically over the next three decades. In the next decade alone, around 300 million Chinese who are currently 50 to 60 years old will retire. This age group makes up the largest population group in China. Their number is almost as large as the total American population of 335 million.

Will this make China a superpower of the elderly? Or, to put it the other way around: Can a country of the elderly be a superpower in the long term? In 2014, Xi urged his party to “prepare for a long-term struggle for international order.” For him, China’s rise to become the dominant superpower is an irreversible “trend of human development” determined by the “inherent laws” of scientific socialism. But who will bear the future costs that a superpower must shoulder in order to secure its power? As recently as the 1990s, for every person in China aged 65 or over, there were ten people of working age. By 2050, the ratio will have fallen drastically. By then, there will only be 1.6 people per capita over 65.

Demographic experts see China as a giant laboratory. Nowhere else in the world has a state intervened so profoundly in the privacy of its citizens as the People’s Republic with its one-child policy. Nowhere else has there been a comparable social experiment of this magnitude.

During the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong called on his people to have children. “As long as there are people, every kind of miracle can be performed,” he called out to his compatriots during the Cultural Revolution. The population grew by around 20 million every year. The Communist Party soon counted too many people for the country’s limited resources – especially for the rapid economic growth that Deng Xiaoping had been striving for since 1978.

It was not only the Communist Party that was concerned with the fear of overpopulation in those years – it was an international trend. In 1968, American entomologist Paul Ehrlich published a book that soon became a worldwide bestseller, “The Population Bomb.” Ehrlich had predicted a mass extinction in the 1970s, “in which hundreds of millions would starve to death” if humanity failed to drastically reduce their numbers.

His words led to alarmism worldwide. Millions of women were sterilized, often against their will. In the Philippines, birth control pills were dropped from helicopters onto remote villages. International organizations funded countless programs to stop population growth.

However, nowhere were the consequences more profound than in China, where the Communist Party imposed the so-called one-child policy nationwide in 1980. “We didn’t realize at the time how far-reaching the consequences would be,” says one of the demographers who advised the government at the time. The policy was highly effective, partly because party and government agencies rigorously enforced it. “When I started working in hospitals in the 2000s after studying gynecology, most of my work was abortions,” says a Beijing woman. “Many women had to have abortions against their will because otherwise they or their husbands would have lost their jobs.”

The family planners had always assumed that the birth rate would plummet as soon as the party ended the one-child policy. In fact, however, the consequences were more dramatic than the party had hoped: In a country that for millennia celebrated the abundance of children, citizens today no longer want to have many children, even if they are allowed to.

When the government initiated the end of the one-child policy in 2016, the birth rate did not rebound. On the contrary: In the eight years since 2016, births in China have fallen by half. It now stands at around one child per woman, far below the 2.1 children needed to keep demographics in balance. More than 65 percent of Chinese people now live in cities; life is expensive, stress is high, and the pressure on children and parents is enormous. The rate of first marriages has also more than halved.

Scientists and family planners ponder why citizens do not want to have children – and how they can be persuaded to do so. Some Chinese scientists believe that the propaganda has been more successful than intended. They believe that citizens have internalized the ideal of the one-child family to such an extent that they only want one child – no matter what subsidies or tax rebates are offered to entice them. China would therefore be caught in the low fertility gap, i.e., a dynamic in which the low fertility of one generation leads directly to the low fertility of the next. The result of the 2021 China General Social Survey, in which 48.3 percent of young women born after 1995 stated that they only wanted to have one child or none at all, could point to this conclusion.

Others believe that young Chinese would have more children if only it were made easier for them. This is the conclusion of a very different survey, one that was highly controversial in China, according to which 80 percent of Chinese university students consider two children to be ideal – which does not mean that they will have that many children one day (the discrepancy between the two surveys could be a warning sign to treat Chinese survey results with caution in general).

Meanwhile, the government is trying with all its might to persuade the people to have children. In the process, it is resorting to conventional instruments used in other countries with varying degrees of success: Maternity leave, tax breaks, subsidies, investments in daycare centers, healthcare and education or facilitated real estate loans for families. Officials in Zhejiang province reportedly offered women subsidies of 100,000 renminbi for the birth of a second child, the equivalent of more than 13,000 euros. Although there is no official policy on this, the officials are said to have stated that they would find the money. In October, The State Council stated that it was working on a plan to create a “birth-friendly society” as part of a larger stimulus program.

And then there are all those instruments that seem rather unconventional from a Western perspective. For example, a massive education and propaganda campaign. Last year, Xi Jinping called for “a new culture of marriage and childbirth.” Since then, the media, party, and government institutions have been rushing to follow the General Secretary’s words. They sing the praises of traditional family values and redesign school textbooks – the cover that once featured a one-child family now shows the same family with two children and a pregnant mother. In December, a publication by the National Health Commission called on universities to offer “marriage and love education courses.” It is the same health commission that once warned women that pregnancy was damaging their intelligence. Now, it preaches to them that having children will make them smarter.

This does not go down well everywhere. Many Chinese citizens mock the campaign, especially many women. Some observers believe that only China – if at all – can succeed in initiating a demographic turnaround. After all, what other country would have the money, capacity, opportunities and personnel to pursue a policy of similar determination? Others doubt it. Just like elsewhere, family planners in China have found that it is much easier to stop people from having children than to encourage them to have them. Once upon a time, the party could force women to have abortions or even forcibly sterilize them. But how is a government going to get its citizens to have sex at the right time?

Indonesia becomes a full BRICS member. This was announced on Monday by BRICS member Brazil, which holds the bloc’s presidency in 2025. “Indonesia shares with the other members of the group support for the reform of global governance institutions, and contributes positively to the deepening of cooperation in the Global South,” the Brazilian government said. Beijing immediately welcomed Brazil’s announcement and congratulated Indonesia as a “major developing country and important force in the Global South.” According to the Chinese government, this development serves the common interests of the BRICS countries.

The Southeast Asian state’s accession to the BRICS Group is not without controversy: US President-elect Donald Trump had threatened to double tariffs if the BRICS group pursues its goal of creating an alternative to the US dollar. At the BRICS meeting in October, chaired by Russia, the bloc of states had announced plans to reshape the international monetary and financial system and challenge the dominance of the US dollar.

Since January 1, eight other countries have also joined the BRICS Group as partner countries:

With the inclusion of these partner countries, 9 of the 20 most populous countries in the world now belong to BRICS. ari/rtr

The Chinese government has announced an action plan to combat dementia. By 2030, it aims to achieve seven goals to reduce the risk of the disease and enable early treatment. The goals include a monitoring and prevention system that will allow people at risk to be screened early on. In addition, the number of specialized dementia care personnel will be increased to 15 million by 2030 and half of all care institutions will be geared towards dementia.

More than 16 million people in China currently suffer from dementia. That is almost one-third of the world’s dementia sufferers. This number is likely to increase further in the coming years, as China’s elderly population is growing rapidly. By 2035, China is expected to have 400 million people over the age of 60. This is roughly equivalent to the total population of the USA and the UK combined. The aging population poses increasing challenges for China’s economy and social policy. rtr/ek

The Serbian military is now able to defend its airspace with the Chinese FK-3 air defense missile system. The Serbian Ministry of Defense announced at the beginning of the year that the system is now operational. It includes a command vehicle, missile launchers, radar equipment and logistics vehicles. Serbian military representatives speak of a “milestone in air defense.”

Serbia purchased the FK-3 missile system as part of an agreement signed in 2019. The contract reaffirmed the military cooperation between the two countries, which heavily focuses on defense technology and strategic partnerships.

The FK-3 is said to be highly maneuverable, which makes it particularly suitable for protecting critical military and civilian infrastructure. It is designed to destroy targets at long range, but can also operate in environments where speed and mobility are crucial. grz

The US government has reported a Chinese hacker attack against Guam’s critical infrastructure. The remote Pacific island is an important US military outpost. Guam is located in relative proximity to China, Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines – making the base crucial in the event of a military conflict over Taiwan.

According to a Bloomberg report, the cyberattack called “Volt Typhoon” aimed to infiltrate critical infrastructure systems such as water supply, power generation and communications in order to sabotage US military and civilian relief operations in the event of a conflict.

Lately, a whole series of Chinese cyberattacks on American targets have become public. Most recently, Chinese hackers managed to hack into the US Department of the Treasury. They also infiltrated the email accounts of US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo and attempted similar attacks on representatives of the US State Department. A Chinese hacker group called Salt Typhoon also managed to penetrate at least nine American telecommunications companies.

Chinese cyberattacks have also been a headache for the Taiwanese government. According to a report by the Taiwanese National Security Bureau, the government’s service network registered an average of 2.4 million attacks per day last year, twice as many as in the previous year. According to the agency, most of these came from China and were mainly directed against telecommunications, transportation and defense. The Chinese government denies all allegations. aiko

Volkswagen and the Chinese electric car manufacturer Xpeng continue to expand their partnership regarding charging infrastructure. According to a letter of intent by VW, customers of both manufacturers will be able to charge their electric cars in 420 Chinese cities in the future by opening up the respective fast charging networks to each other’s customers. A total of 20,000 charging stations are involved. 13,000 of these will be operated by CAMS, a joint venture between Volkswagen, FAW and JAC.

Volkswagen acquired a 4.99 percent stake in Xpeng in 2023 for around 700 million dollars. The manufacturers plan to develop two electric models by 2026. VW also wants to work with Xpeng to develop faster charging stations. Like all German car manufacturers, Volkswagen is under pressure: the company has fallen behind EV manufacturers such as BYD in China. In Germany, too, consolidated profit has recently plummeted. rtr/ek

The US has placed China’s tech giant Tencent and battery manufacturer CATL on a list of companies suspected of working with the Chinese military. This is according to an announcement by the US Department of Defense on Monday. The list includes further new entries: Chip maker Changxin Memory Technologies Inc (CXMT), telecom equipment maker Quectel Wireless and drone maker Autel Robotics, according to a document released on Monday.

The annually updated list of Chinese military companies, formally mandated under U.S. law as the “Section 1260H list,” designated 134 companies. A Quectel spokesperson said the company “does not work with the military in any country and will ask the Pentagon to reconsider its designation, which clearly has been made in error.” The other companies and the Chinese embassy in Washington did not respond to requests or did not immediately comment. rtr/ari

In April 2024, a spokesperson for former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte suggested that the Philippines and China had entered into an undisclosed “gentleman’s agreement” between 2016 and 2022. China would not challenge the status quo in the West Philippine Sea, and the Philippines would send only basic supplies to its personnel and facilities on the Ayungin Shoal. But now, the Philippines is emerging as an essential player in resisting China’s strategic ambitions in the region, with President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr.’s administration asserting Philippine maritime claims through naval confrontations and new legislation.

This comes at a time when the country is facing a quieter, but equally serious, threat at home. The recent, high-profile case of Alice Guo – a former mayor accused of graft, money laundering, and espionage – shows how domestic corruption leaves the Philippines vulnerable to Chinese infiltration and subterfuge. How the Philippines navigates this challenge could shape not only its future but also the broader stability of Southeast Asia.

In addition to conducting aggressive military maneuvers in the surrounding seas, China is also pursuing strategic investments and subtler forms of manipulation to push Philippine leaders (at all levels of government) into a more China-friendly stance. This is in keeping with its global strategy of building influence through investments targeting other countries’ elites, clandestine business alliances, and economic incentives. As the Philippines approaches critical elections in 2025 and 2028, China will try to befriend or otherwise gain sway over anyone who is open to its overtures.

Given these efforts, one cannot rule out a future Philippine government that adopts China’s own model of governance, state control, and mass surveillance. Such a government might not only consult China’s authoritarian playbook to quash dissent; he or she could also leverage China’s resources and international political support to evade scrutiny and accountability. Institutions meant to serve the Philippine people would become tools for monitoring and restricting opponents and critics, and China will have secured itself a valuable foothold in Southeast Asia.

China has been stepping up its information operations globally, using the Philippines as a testing ground for tactics designed to propagate anti-American narratives and build pro-Chinese sentiment. Through platforms like Facebook and TikTok, which many Filipinos rely on for news, Chinese accounts amplify content that casts doubt on Philippine-US relations and erodes social trust within Philippine society.

By exploiting internal instability, Chinese influence operations aim to distract Philippine authorities from China’s own aggression in the surrounding seas. One potential source of disruption is the lead-up to the elections in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). Should an ongoing peace process there falter, the region would inevitably demand much more of the national government’s attention and resources.

What can be done? Even if US investments do not match the scale of China’s infrastructure projects in the Philippines, Western strategic aid can help by presenting a clear alternative to China’s debt-driven model. Such a strategy would not only support Philippine sovereignty but also strengthen America’s network of alliances in the Indo-Pacific.

Specifically, to counter Chinese interference, the US and its allies should direct investments and support to advance four priorities:

1. Fight corruption: Since corruption is a national-security threat, they should fund programs to ensure disclosures of “beneficial ownership” (who ultimately owns private businesses), debt transparency, and the integrity of public procurement and tendering processes. This would not only create a level playing field for all businesses; it would also help safeguard Philippine institutions and political processes from covert foreign manipulation.

2. Protect elections: the integrity of elections must be strengthened. Long-term election monitoring can help expose and counter covert foreign influence efforts and misuses of resources, ensuring transparency beyond Election Day. If sufficiently supported, citizen-led observation efforts can reinforce the sense that the process is fair, making electoral institutions more resilient against external pressures.

3. Secure the peace process in BARMM: The Philippines’ allies need to protect the BARMM peace process, such as by funding initiatives that strengthen local governance and security institutions in the region. The peace process, and the country more broadly, would benefit from enhanced information security, including targeted support for local initiatives to improve the public’s digital news literacy.

4. Strengthen cybersecurity: The Philippines needs help countering Chinese surveillance of its citizens and officials. US support for cybersecurity and programs to protect digital rights can frustrate Chinese influence tactics and provide more transparency on major digital platforms.

A stable, democratic Philippines is vital to US interests and regional security. America and its Indo-Pacific partners and allies must do more to help the country build resilience against Chinese aggression not only in its territorial waters, but also in its politics.

Adam Nelson is Senior Program Director for the Asia-Pacific at the National Democratic Institute. May Butoy is the Country Representative for the Philippines at the National Democratic Institute.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2025.

Editor’s note: Discussing China today means – more than ever – holding controversial debates. We aim to reflect the diversity of opinions to give you an insight into the breadth of the debate. Opinions do not reflect the views of the editorial team.

Li Nan is the new Vice President of the Technical Division at Porsche China. Li previously held senior positions at Mercedes-Benz. Based on his experience in infotainment, big data and artificial intelligence, he will be responsible for driving forward product development at Porsche. He will be based in Shanghai.

Ella Cao is the new China correspondent at Reuters with a focus on agriculture. Cao has already been working for the news agency for three years, most recently in the “Breaking News” team. She will continue to be based in Beijing.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

You really have to envy a bird’s perspective on the world. This picture from December shows an observation tower in the Huanghai Forest Park – a large, ecological, artificially created area in the city of Dongtai in Jiangsu Province in eastern China. In the 1960s, a forest area of 2,500 hectares was created on a total area of 3,000 hectares. It is popular with tourists and is regarded as the region’s “green oxygen bar.”

China’s one-child policy is one of the biggest social interventions by a government in the post-war period. The result is well known: China has successfully curbed the dynamic growth of its population. However, the consequences of the government’s birth control policy are so immense that it has long since become a massive problem. The demographic trend is alarming, and the consequences are dramatic.

Beijing wants to use Chinese pragmatism to reverse the trend. Many women of childbearing age receive telephone calls from their neighborhood committee encouraging them to become pregnant. The Communist Party naturally provides the recommended vitamins for expectant mothers free of charge.

The past has shown that the government has indeed managed to decisively intervene in population growth – if necessary through forced abortions or forced sterilizations. But how will the government get its citizens to have sex at the right time, wonders Angela Köckritz.

China applies a different kind of influence in the Philippines. Beijing attempts to persuade the country’s decision-makers to adopt a pro-China stance. To this end, it relies on investments and manipulation tactics. The authors of today’s opinion piece recommend that the West, particularly the US, should offer the Philippines alternatives to prevent the country from becoming more authoritarian: strategic aid, for example. This would not only strengthen Philippine sovereignty, but also strengthen America’s network of alliances in the Indo-Pacific.

Recently, many married Chinese women in their twenties and thirties have been receiving calls from their neighborhood committees. “When was the last time you had your period?” the person on the other end of the line wants to know. Or: “Are you planning to have a baby?” Or: “Your child is almost two years old now. You could get pregnant again.” You are welcome to pick up free folic acid tablets from the neighborhood committee. A small gift from the party. Doctors recommend that women who want to have children take the vitamin to prevent birth defects.

The calls happen very regularly – in the obvious hope of not letting any ovulation go to waste. They reveal the desperation with which the Chinese government is trying to tackle the huge demographic crisis. According to the latest United Nations forecast, China is expected to lose half of its population by the end of the century, making it the largest population loss in the world.

In 2100, only around 550 million people could still be living in China, which would be the same number as in the 1950s. The only difference is that the Chinese will be much older then. In 1950, the average Chinese person was around 22 years old. The same as in 1985. In 2050, the average age will rise to 52. In 2085, it is expected to be 62.

The Chinese government is in the eye of the hurricane, as the population is set to decline dramatically over the next three decades. In the next decade alone, around 300 million Chinese who are currently 50 to 60 years old will retire. This age group makes up the largest population group in China. Their number is almost as large as the total American population of 335 million.

Will this make China a superpower of the elderly? Or, to put it the other way around: Can a country of the elderly be a superpower in the long term? In 2014, Xi urged his party to “prepare for a long-term struggle for international order.” For him, China’s rise to become the dominant superpower is an irreversible “trend of human development” determined by the “inherent laws” of scientific socialism. But who will bear the future costs that a superpower must shoulder in order to secure its power? As recently as the 1990s, for every person in China aged 65 or over, there were ten people of working age. By 2050, the ratio will have fallen drastically. By then, there will only be 1.6 people per capita over 65.

Demographic experts see China as a giant laboratory. Nowhere else in the world has a state intervened so profoundly in the privacy of its citizens as the People’s Republic with its one-child policy. Nowhere else has there been a comparable social experiment of this magnitude.

During the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong called on his people to have children. “As long as there are people, every kind of miracle can be performed,” he called out to his compatriots during the Cultural Revolution. The population grew by around 20 million every year. The Communist Party soon counted too many people for the country’s limited resources – especially for the rapid economic growth that Deng Xiaoping had been striving for since 1978.

It was not only the Communist Party that was concerned with the fear of overpopulation in those years – it was an international trend. In 1968, American entomologist Paul Ehrlich published a book that soon became a worldwide bestseller, “The Population Bomb.” Ehrlich had predicted a mass extinction in the 1970s, “in which hundreds of millions would starve to death” if humanity failed to drastically reduce their numbers.

His words led to alarmism worldwide. Millions of women were sterilized, often against their will. In the Philippines, birth control pills were dropped from helicopters onto remote villages. International organizations funded countless programs to stop population growth.

However, nowhere were the consequences more profound than in China, where the Communist Party imposed the so-called one-child policy nationwide in 1980. “We didn’t realize at the time how far-reaching the consequences would be,” says one of the demographers who advised the government at the time. The policy was highly effective, partly because party and government agencies rigorously enforced it. “When I started working in hospitals in the 2000s after studying gynecology, most of my work was abortions,” says a Beijing woman. “Many women had to have abortions against their will because otherwise they or their husbands would have lost their jobs.”

The family planners had always assumed that the birth rate would plummet as soon as the party ended the one-child policy. In fact, however, the consequences were more dramatic than the party had hoped: In a country that for millennia celebrated the abundance of children, citizens today no longer want to have many children, even if they are allowed to.

When the government initiated the end of the one-child policy in 2016, the birth rate did not rebound. On the contrary: In the eight years since 2016, births in China have fallen by half. It now stands at around one child per woman, far below the 2.1 children needed to keep demographics in balance. More than 65 percent of Chinese people now live in cities; life is expensive, stress is high, and the pressure on children and parents is enormous. The rate of first marriages has also more than halved.

Scientists and family planners ponder why citizens do not want to have children – and how they can be persuaded to do so. Some Chinese scientists believe that the propaganda has been more successful than intended. They believe that citizens have internalized the ideal of the one-child family to such an extent that they only want one child – no matter what subsidies or tax rebates are offered to entice them. China would therefore be caught in the low fertility gap, i.e., a dynamic in which the low fertility of one generation leads directly to the low fertility of the next. The result of the 2021 China General Social Survey, in which 48.3 percent of young women born after 1995 stated that they only wanted to have one child or none at all, could point to this conclusion.

Others believe that young Chinese would have more children if only it were made easier for them. This is the conclusion of a very different survey, one that was highly controversial in China, according to which 80 percent of Chinese university students consider two children to be ideal – which does not mean that they will have that many children one day (the discrepancy between the two surveys could be a warning sign to treat Chinese survey results with caution in general).

Meanwhile, the government is trying with all its might to persuade the people to have children. In the process, it is resorting to conventional instruments used in other countries with varying degrees of success: Maternity leave, tax breaks, subsidies, investments in daycare centers, healthcare and education or facilitated real estate loans for families. Officials in Zhejiang province reportedly offered women subsidies of 100,000 renminbi for the birth of a second child, the equivalent of more than 13,000 euros. Although there is no official policy on this, the officials are said to have stated that they would find the money. In October, The State Council stated that it was working on a plan to create a “birth-friendly society” as part of a larger stimulus program.

And then there are all those instruments that seem rather unconventional from a Western perspective. For example, a massive education and propaganda campaign. Last year, Xi Jinping called for “a new culture of marriage and childbirth.” Since then, the media, party, and government institutions have been rushing to follow the General Secretary’s words. They sing the praises of traditional family values and redesign school textbooks – the cover that once featured a one-child family now shows the same family with two children and a pregnant mother. In December, a publication by the National Health Commission called on universities to offer “marriage and love education courses.” It is the same health commission that once warned women that pregnancy was damaging their intelligence. Now, it preaches to them that having children will make them smarter.

This does not go down well everywhere. Many Chinese citizens mock the campaign, especially many women. Some observers believe that only China – if at all – can succeed in initiating a demographic turnaround. After all, what other country would have the money, capacity, opportunities and personnel to pursue a policy of similar determination? Others doubt it. Just like elsewhere, family planners in China have found that it is much easier to stop people from having children than to encourage them to have them. Once upon a time, the party could force women to have abortions or even forcibly sterilize them. But how is a government going to get its citizens to have sex at the right time?

Indonesia becomes a full BRICS member. This was announced on Monday by BRICS member Brazil, which holds the bloc’s presidency in 2025. “Indonesia shares with the other members of the group support for the reform of global governance institutions, and contributes positively to the deepening of cooperation in the Global South,” the Brazilian government said. Beijing immediately welcomed Brazil’s announcement and congratulated Indonesia as a “major developing country and important force in the Global South.” According to the Chinese government, this development serves the common interests of the BRICS countries.

The Southeast Asian state’s accession to the BRICS Group is not without controversy: US President-elect Donald Trump had threatened to double tariffs if the BRICS group pursues its goal of creating an alternative to the US dollar. At the BRICS meeting in October, chaired by Russia, the bloc of states had announced plans to reshape the international monetary and financial system and challenge the dominance of the US dollar.

Since January 1, eight other countries have also joined the BRICS Group as partner countries:

With the inclusion of these partner countries, 9 of the 20 most populous countries in the world now belong to BRICS. ari/rtr

The Chinese government has announced an action plan to combat dementia. By 2030, it aims to achieve seven goals to reduce the risk of the disease and enable early treatment. The goals include a monitoring and prevention system that will allow people at risk to be screened early on. In addition, the number of specialized dementia care personnel will be increased to 15 million by 2030 and half of all care institutions will be geared towards dementia.

More than 16 million people in China currently suffer from dementia. That is almost one-third of the world’s dementia sufferers. This number is likely to increase further in the coming years, as China’s elderly population is growing rapidly. By 2035, China is expected to have 400 million people over the age of 60. This is roughly equivalent to the total population of the USA and the UK combined. The aging population poses increasing challenges for China’s economy and social policy. rtr/ek

The Serbian military is now able to defend its airspace with the Chinese FK-3 air defense missile system. The Serbian Ministry of Defense announced at the beginning of the year that the system is now operational. It includes a command vehicle, missile launchers, radar equipment and logistics vehicles. Serbian military representatives speak of a “milestone in air defense.”

Serbia purchased the FK-3 missile system as part of an agreement signed in 2019. The contract reaffirmed the military cooperation between the two countries, which heavily focuses on defense technology and strategic partnerships.

The FK-3 is said to be highly maneuverable, which makes it particularly suitable for protecting critical military and civilian infrastructure. It is designed to destroy targets at long range, but can also operate in environments where speed and mobility are crucial. grz

The US government has reported a Chinese hacker attack against Guam’s critical infrastructure. The remote Pacific island is an important US military outpost. Guam is located in relative proximity to China, Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines – making the base crucial in the event of a military conflict over Taiwan.

According to a Bloomberg report, the cyberattack called “Volt Typhoon” aimed to infiltrate critical infrastructure systems such as water supply, power generation and communications in order to sabotage US military and civilian relief operations in the event of a conflict.

Lately, a whole series of Chinese cyberattacks on American targets have become public. Most recently, Chinese hackers managed to hack into the US Department of the Treasury. They also infiltrated the email accounts of US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo and attempted similar attacks on representatives of the US State Department. A Chinese hacker group called Salt Typhoon also managed to penetrate at least nine American telecommunications companies.

Chinese cyberattacks have also been a headache for the Taiwanese government. According to a report by the Taiwanese National Security Bureau, the government’s service network registered an average of 2.4 million attacks per day last year, twice as many as in the previous year. According to the agency, most of these came from China and were mainly directed against telecommunications, transportation and defense. The Chinese government denies all allegations. aiko

Volkswagen and the Chinese electric car manufacturer Xpeng continue to expand their partnership regarding charging infrastructure. According to a letter of intent by VW, customers of both manufacturers will be able to charge their electric cars in 420 Chinese cities in the future by opening up the respective fast charging networks to each other’s customers. A total of 20,000 charging stations are involved. 13,000 of these will be operated by CAMS, a joint venture between Volkswagen, FAW and JAC.

Volkswagen acquired a 4.99 percent stake in Xpeng in 2023 for around 700 million dollars. The manufacturers plan to develop two electric models by 2026. VW also wants to work with Xpeng to develop faster charging stations. Like all German car manufacturers, Volkswagen is under pressure: the company has fallen behind EV manufacturers such as BYD in China. In Germany, too, consolidated profit has recently plummeted. rtr/ek

The US has placed China’s tech giant Tencent and battery manufacturer CATL on a list of companies suspected of working with the Chinese military. This is according to an announcement by the US Department of Defense on Monday. The list includes further new entries: Chip maker Changxin Memory Technologies Inc (CXMT), telecom equipment maker Quectel Wireless and drone maker Autel Robotics, according to a document released on Monday.

The annually updated list of Chinese military companies, formally mandated under U.S. law as the “Section 1260H list,” designated 134 companies. A Quectel spokesperson said the company “does not work with the military in any country and will ask the Pentagon to reconsider its designation, which clearly has been made in error.” The other companies and the Chinese embassy in Washington did not respond to requests or did not immediately comment. rtr/ari

In April 2024, a spokesperson for former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte suggested that the Philippines and China had entered into an undisclosed “gentleman’s agreement” between 2016 and 2022. China would not challenge the status quo in the West Philippine Sea, and the Philippines would send only basic supplies to its personnel and facilities on the Ayungin Shoal. But now, the Philippines is emerging as an essential player in resisting China’s strategic ambitions in the region, with President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr.’s administration asserting Philippine maritime claims through naval confrontations and new legislation.

This comes at a time when the country is facing a quieter, but equally serious, threat at home. The recent, high-profile case of Alice Guo – a former mayor accused of graft, money laundering, and espionage – shows how domestic corruption leaves the Philippines vulnerable to Chinese infiltration and subterfuge. How the Philippines navigates this challenge could shape not only its future but also the broader stability of Southeast Asia.

In addition to conducting aggressive military maneuvers in the surrounding seas, China is also pursuing strategic investments and subtler forms of manipulation to push Philippine leaders (at all levels of government) into a more China-friendly stance. This is in keeping with its global strategy of building influence through investments targeting other countries’ elites, clandestine business alliances, and economic incentives. As the Philippines approaches critical elections in 2025 and 2028, China will try to befriend or otherwise gain sway over anyone who is open to its overtures.

Given these efforts, one cannot rule out a future Philippine government that adopts China’s own model of governance, state control, and mass surveillance. Such a government might not only consult China’s authoritarian playbook to quash dissent; he or she could also leverage China’s resources and international political support to evade scrutiny and accountability. Institutions meant to serve the Philippine people would become tools for monitoring and restricting opponents and critics, and China will have secured itself a valuable foothold in Southeast Asia.

China has been stepping up its information operations globally, using the Philippines as a testing ground for tactics designed to propagate anti-American narratives and build pro-Chinese sentiment. Through platforms like Facebook and TikTok, which many Filipinos rely on for news, Chinese accounts amplify content that casts doubt on Philippine-US relations and erodes social trust within Philippine society.

By exploiting internal instability, Chinese influence operations aim to distract Philippine authorities from China’s own aggression in the surrounding seas. One potential source of disruption is the lead-up to the elections in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). Should an ongoing peace process there falter, the region would inevitably demand much more of the national government’s attention and resources.

What can be done? Even if US investments do not match the scale of China’s infrastructure projects in the Philippines, Western strategic aid can help by presenting a clear alternative to China’s debt-driven model. Such a strategy would not only support Philippine sovereignty but also strengthen America’s network of alliances in the Indo-Pacific.

Specifically, to counter Chinese interference, the US and its allies should direct investments and support to advance four priorities:

1. Fight corruption: Since corruption is a national-security threat, they should fund programs to ensure disclosures of “beneficial ownership” (who ultimately owns private businesses), debt transparency, and the integrity of public procurement and tendering processes. This would not only create a level playing field for all businesses; it would also help safeguard Philippine institutions and political processes from covert foreign manipulation.

2. Protect elections: the integrity of elections must be strengthened. Long-term election monitoring can help expose and counter covert foreign influence efforts and misuses of resources, ensuring transparency beyond Election Day. If sufficiently supported, citizen-led observation efforts can reinforce the sense that the process is fair, making electoral institutions more resilient against external pressures.

3. Secure the peace process in BARMM: The Philippines’ allies need to protect the BARMM peace process, such as by funding initiatives that strengthen local governance and security institutions in the region. The peace process, and the country more broadly, would benefit from enhanced information security, including targeted support for local initiatives to improve the public’s digital news literacy.

4. Strengthen cybersecurity: The Philippines needs help countering Chinese surveillance of its citizens and officials. US support for cybersecurity and programs to protect digital rights can frustrate Chinese influence tactics and provide more transparency on major digital platforms.

A stable, democratic Philippines is vital to US interests and regional security. America and its Indo-Pacific partners and allies must do more to help the country build resilience against Chinese aggression not only in its territorial waters, but also in its politics.

Adam Nelson is Senior Program Director for the Asia-Pacific at the National Democratic Institute. May Butoy is the Country Representative for the Philippines at the National Democratic Institute.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2025.

Editor’s note: Discussing China today means – more than ever – holding controversial debates. We aim to reflect the diversity of opinions to give you an insight into the breadth of the debate. Opinions do not reflect the views of the editorial team.

Li Nan is the new Vice President of the Technical Division at Porsche China. Li previously held senior positions at Mercedes-Benz. Based on his experience in infotainment, big data and artificial intelligence, he will be responsible for driving forward product development at Porsche. He will be based in Shanghai.

Ella Cao is the new China correspondent at Reuters with a focus on agriculture. Cao has already been working for the news agency for three years, most recently in the “Breaking News” team. She will continue to be based in Beijing.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

You really have to envy a bird’s perspective on the world. This picture from December shows an observation tower in the Huanghai Forest Park – a large, ecological, artificially created area in the city of Dongtai in Jiangsu Province in eastern China. In the 1960s, a forest area of 2,500 hectares was created on a total area of 3,000 hectares. It is popular with tourists and is regarded as the region’s “green oxygen bar.”