Germany’s new government has only been in office for a few days – and several conflicts with China are already on the horizon. In the first case, German companies, such as the automotive supplier Continental, are caught between the fronts in what was a solely political dispute at first. This is why, at the beginning of the week, the Federation of German Industries warned Beijing of a “disastrous own goal“. The German Chamber of Commerce in China even addressed a letter to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce. For the latest developments, please see our News section.

The second case is about the grand plans of the new German government: Expanding solar power – and simultaneously ensuring human rights in global supply chains. A difficult task. After all, there has long been no way past the global market leader China in the solar power sector. And, according to experts, the People’s Republic produces the raw material for solar panels in Xinjiang under forced labor. In such cases, discussions about sanctions quickly emerge. But they lead to a dead-end, as Nico Beckert analyses.

And even sport is not immune to political conflict. For the first time, Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai has spoken about her allegations of sexual assault against a senior party official. Marcel Grzanna has taken a closer look at the interview. To him, the tennis player’s statements seem like pretend subterfuge. This makes Peng Shuai’s case seem like the latest part in the history of how the Chinese government deals with its dissidents, activists, and critics.

The new federal government has a number of plans for the expansion of renewable powers. It wants to mount solar power on “all suitable roofs”. By 2030, “around 200 gigawatts” of photovoltaic capacity are to be achieved. This means a quadrupling of the current capacity. To achieve this, the traffic light coalition wants to remove many “hurdles to expansion”. This is what the coalition agreement says.

One major hurdle that is not mentioned, is the supply chain of the solar industry. A large part of the basic material of solar cells, polysilicon, is produced in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. However, there are accusations that this polysilicon is produced through forced labor by the Uyghur ethnic group. This poses considerable problems if ethical standards are to apply to this supply chain in the future.

Recently, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock announced a clearer policy against human rights violations in China. “If products from regions like Xinjiang, where forced labor is common practice, are blocked, that’s a big problem for an exporting country like China,” she said in an interview with taz and China.Table.

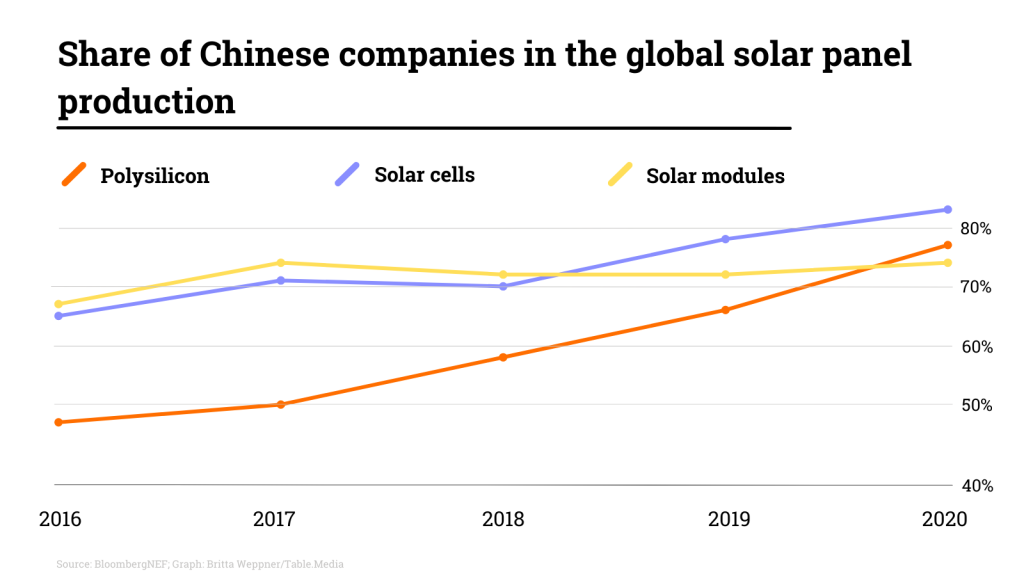

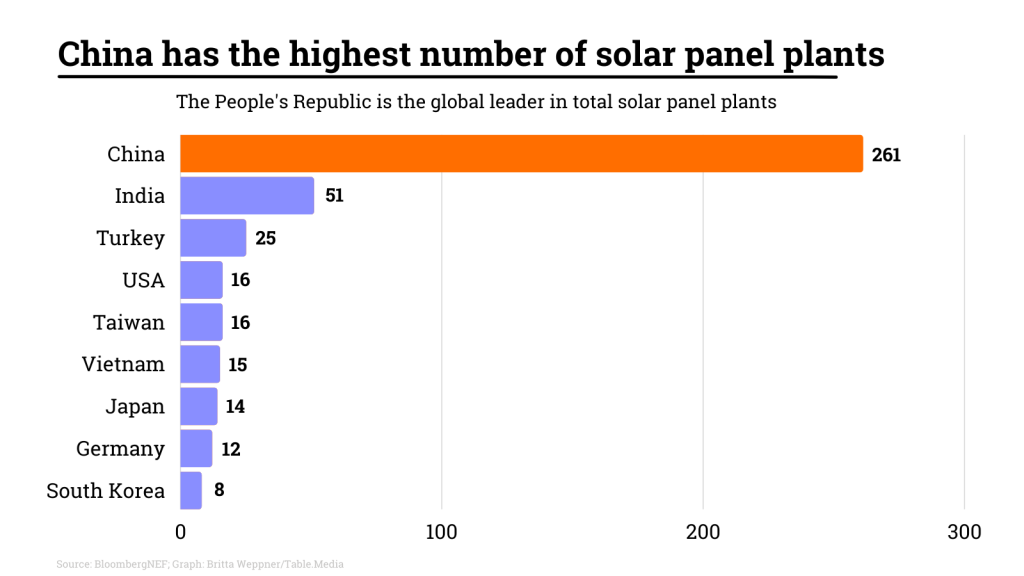

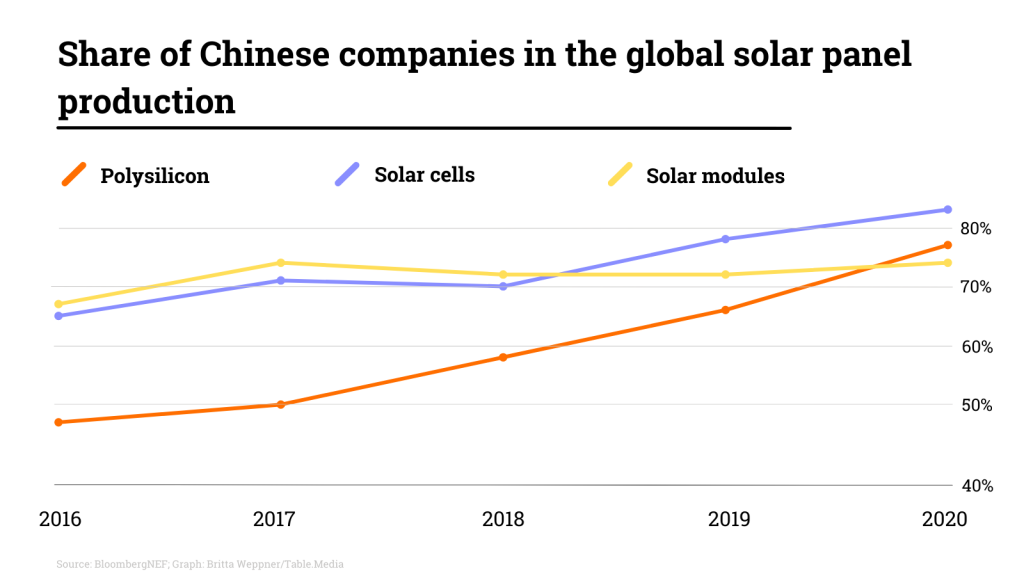

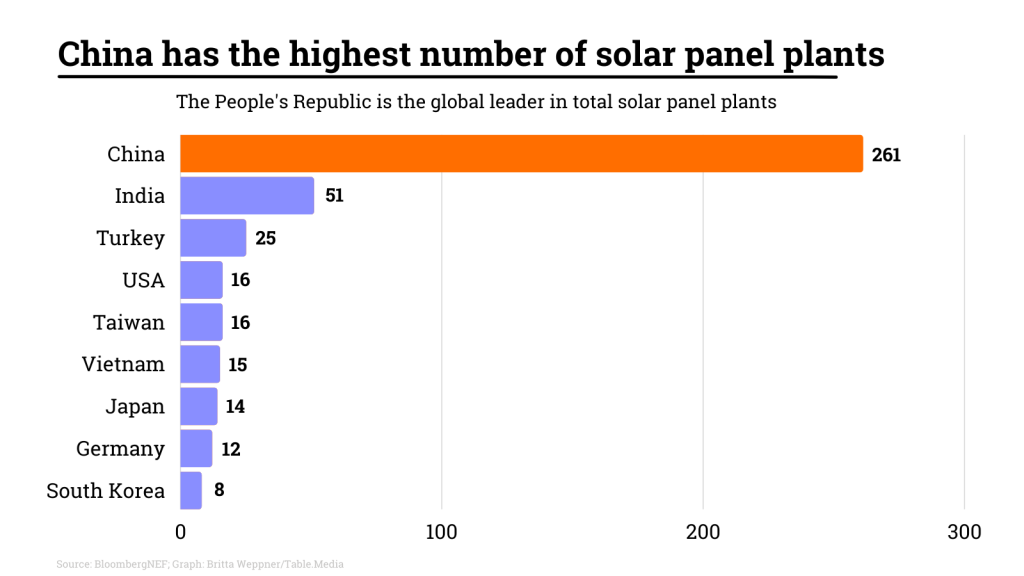

But it is not only China, who would then face a problem. The expansion of solar energy in Germany could also come to a grinding halt. Much of the polysilicon is processed directly in China. The People’s Republic is the global market leader in the solar sector and dominates all production steps. Worldwide, three out of four solar modules and 83 percent of solar cells are produced in China. China dominates 77 percent of the global market for polysilicon. Xinjiang again plays a special role here. An estimated 50 percent of global polysilicon production is located in the western Chinese region.

Large amounts of power are required for the production of polysilicon and its precursor silicon metal. Xinjiang has an abundance of it. There is hardly any other part of the country where power and process heat for the production of polysilicon is so cheap. Four of the world’s largest manufacturers have factories in Xinjiang, according to an analysis by Bloomberg. Three producers have been accused of using forced labor in their factories.

The allegations are based on reports by consulting firms Horizon Advisory and S&P Global Market Intelligence, as well as research by Xinjiang researcher Adrian Zenz. They independently conclude that hundreds of forced laborers are involved in the production of polysilicon. A Bloomberg research team was denied access to the factories. The journalists have not been allowed to examine the production and interpret this as a sign that the manufacturers have something to hide.

Other experts, however, give the all-clear in part. True, China’s global market share looks very high on paper. But a large part of it remains domestic. No other country installs as many solar modules as China. A large part of the domestic production is therefore not exported in the first place.

Moreover, the other half of China’s production is produced outside Xinjiang. Together with manufacturing in other regions of the world, there are enough solar modules to meet demand. “The US and Europe together accounted for about 30 percent of new global PV installations in 2020,” says market observer Johannes Bernreuter of consulting firm Bernreuter Research. “So arithmetically, there is enough polysilicon for the US and Europe right now that is not affected by Xinjiang.”

Surprisingly, neither the EU’s statistical authority (Eurostat) nor the Federal Statistical Office have any data on how many solar cells and modules Germany imports from China.

But when Western buyers acquire solar cells and modules from China, they have so far been faced with a problem: polysilicon from various sources is mixed during production. It could very well be that basic material from Xinjiang is also included, which was produced through forced labor. However, Chinese manufacturers are adapting to the needs of the West. Some companies are likely producing Xinjiang-free segments and using them in their solar modules for export to the US and Europe, Bernreuter explains. “They can also provide plausible documents that the solar modules and cells do not contain any primary products from Xinjiang.”

This could mean that material flows could simply be split: Xinjiang-free products are manufactured for export. Solar modules, whose raw material is produced through forced labor, continue to be installed in China due to the high domestic demand. Western sanctions and boycotts of polysilicon from Xinjiang would thus have little effect. Bernreuter criticizes: “To put it bluntly: The West eases its conscience, but the Uyghurs are not better off.” However, one should not underestimate sanctions as a political signal, Bernreuter adds.

Another problem in the solar supply chain is the basic material for polysilicon: so-called metallurgical-grade silicon. The Chinese manufacturers of this highly pure silicon have no interest in transparency. So importers can hardly be sure that no forced labor is involved in the production of metallurgical-grade silicon. This is the reason why some Western and Asian manufacturers of polysilicon have already terminated their business relations with the largest producer of metallurgical silicon, Hoshine Silicon from Xinjiang. In addition, the US Customs Service has taken action against Hoshine. There is information that the company uses forced labor, the agency said. Products from Hoshine are confiscated by customs at US ports.

However, this by no means resolves the situation. The US is currently discussing additional measures to exclude forced labor in Xinjiang in imported products. As these go far beyond current measures, it would further reduce the number of basic materials that can be imported legally. Recently, the US House of Representatives and the Senate passed a bill that would place all products from Xinjiang under suspicion of being produced by forced labor (China.Table reported).

This reverses the burden of proof. Imports would then be banned as long as the US government is not presented with verifiable evidence that forced labor was not involved in the production. US President Biden still has to approve the bill. Republicans accuse Biden of filibustering, stating that the law would make it harder to expand renewable power. Biden’s plans to expand solar power are similarly ambitious to those of the new German government. By 2050, about half of US electricity is to be generated by solar power. Currently, it is only four percent.

But experts say the US law could prove to be ineffective for the solar supply chain. If the US bill is signed into law next year, Chinese manufacturers will already be prepared. “We expect that solar wafer manufacturers, all of which are located in China, will then be able to separate supply chains for different markets,” says Jenny Chase of Bloomberg NEF, confirming the suspicions of polysilicon expert Bernreuter. Another question will be whether buyer countries will simply believe the suppliers’ claims of origin.

Solar supply chains are currently still so complex that it is difficult to manufacture truly Xinjiang-free solar modules and cells. Industry expert Bernreuter, therefore, advises the industry to play it safe and become less dependent on China. “There is no way around building new solar supply chains outside of China.” This could increase the price of the modules by about ten percent. “If environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) criteria are more than just lip service to them, investors and consumers must be prepared to pay this price,” says Bernreuter.

The new German government also signaled China.Table that it intends to take action. The German Foreign Office states that the government wants to “support a possible import ban on products from forced labor at the European level”. Likewise, the European supply chain law is to be “supported.” However, a clear stand against forced labor in Xinjiang sounds different.

World-class Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai has distanced herself from her rape allegations against former Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli. A roughly four-minute-long video from last Sunday, which has been circulating on social media since the start of the week, shows the 35-year-old talking to a Singaporean journalist. In it, Peng stated that “I have never said that I wrote that anyone sexually assaulted me”.

The statement is the opposite of what has escalated into a global political issue since early November. At that time, Peng had accused former government official Zhang on short message service Weibo of forcing her to have sex. After 30 minutes, the post was deleted again. After that, the athlete even disappeared for several weeks. As a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, Zhang belonged to the Communist Party’s innermost circle of power until 2017.

“About the Weibo [post], it’s a private matter. There seems to have been a lot of misinterpretation from the public,” Peng said on Sunday. The interview, which supposedly was not planned, was her first public verbal statement about what had happened. Previously, only written statements had surfaced, but it was not clear whether Peng had written it herself.

She confirmed to the reporter of the daily newspaper Lianhe Zaobao, that she had indeed written the letter to the head of the Women’s Tennis Association WTA, Steve Simon. In the letter, Peng asked Simon to respect her privacy after the official threatened consequences for China as a tennis venue and demanded clarification from the Chinese authorities. Peng admitted that she had drafted the letter in Chinese before it was translated into English. She explained that her English was not good enough.

But the new video is also not convincing many skeptics. Peng looks around nervously at times, responds to several questions saying she didn’t understand them properly, and when it came to the most important part of the interview, she chooses her words very slowly and carefully. The WTA commented that “these appearances do not alleviate or address the WTA’s significant concerns about her wellbeing and ability to communicate without censorship or coercion.”

The poor track record of the way the Chinese government deals with dissidents, activists, or critics in its own country causes doubts. The human rights organization Safeguard Defenders referred to a 2018 publication entitled “Scripted and Staged”, which examines similar cases in which the accused first disappeared and then publicly apologized after their reappearance.

Safeguard director Peter Dahlin also questioned Peng’s claim that her English language skills were not good enough to write to the WTA director in English. He posted a video of a press conference in which the former Wimbledon doubles champion responds to journalists’ questions in fluent English.

Human rights lawyer Teng Biao, who was once tortured while being detained by Chinese security authorities and now lives in exile in the US, also doubts that Peng’s statements were voluntary. On Twitter, Biao wrote: “The world has been discussing it for 47 days, nobody was able to reach her out except the Party/its puppets. Needs 47 days to say she’d been misunderstood?”

Especially since Peng claims in the video, which was made in Shanghai on the sidelines of a promotional event for February’s Winter Olympics in Beijing, that she was able to “move freely”, it begs the question of why she did not appear in public sooner to prevent an escalation.

After all, her case was the breaking point for numerous Western governments. Led by the US, nearly two dozen Western nations have already announced that they will not send a delegation to the Olympics.

At the same time, the WTA has suspended all its tournaments in the People’s Republic and Hong Kong until further notice. So Peng could have done some early damage control if she was indeed free to move and express herself as she now claims. Instead, tensions between China and many democratic countries intensified while she remained silent.

Wang Yaqiu of Human Rights Watch (HRW) even doubts that the interview with the Singaporean journalist was a coincidence. “So, after 48 days, Peng Shuai unexpectedly encountered a journalist from a pro-Beijing newspaper and then casually answered her questions about an event that garnered huge international attention. Wow, so natural, very real, everyone now believes it. Congratulations, the CCP!” Wang wrote on Twitter.

The Chinese side, on the other hand, tried to bolster the credibility of the statement. Former editor-in-chief and current chief columnist of the state-run Global Times newspaper, Hu Xijin, wrote “Peng Shuai firmly opposed use of ‘sexual assault’ to interpret what she described in her post, and denied she thought she was sexually assaulted. The outside world should respect this basic attitude of her.” In plain English, this means that Peng never saw herself as a victim of sexual assault, but that third parties merely misinterpreted her post.

German business representatives are taking an increasingly critical stance in the trade conflict between Lithuania and China, thus also increasing the pressure on Berlin. The Federation of German Industries (BDI) is now accusing Beijing of scoring a “disastrous own goal”. “China’s latest measures against Lithuania are having the effect of a trade boycott with repercussions for the entire EU,” the BDI announced. “Imports from China that are needed in German production facilities in Lithuania and exports from Germany to China that contain Lithuanian components are also affected” This action shows that China is willing to “economically decouple itself from politically disagreeable partners”. Nevertheless, it would be important to maintain economic relations with China at a high level.

The German Chamber of Commerce in China also intervened: “A quick solution” must be found “to enable the smooth import of products and parts from the entire EU to China, as well as export to the EU”, the statement reads. The chamber also wrote to China’s Ministry of Commerce. “For some time now, we have been concerned about the increasing politicization of economic relations. De facto trade barriers, such as we are now seeing about imports and exports from Lithuania, do more harm than good.”

China has been blocking imports from Lithuania since the beginning of the month. The EU state disappeared from the customs system. Since last week, German automotive companies cooperating with Lithuanian suppliers have also been affected (China.Table reported), including Continental and, according to FT, Lippstadt-based Hella.

The EU stated that it is currently gathering material for a possible complaint to the World Trade Organization. Gathering the necessary information will not be easy, however, as China has never officially spoken of a blockade of Lithuania in its customs system. Moreover, companies that now speak out against the People’s Republic fear long-term exclusion from the Chinese market or other reprisals. ari

Pro-Beijing candidates achieved an overwhelming victory in Sunday’s parliamentary election in Hong Kong. 82 of the 90 parliamentary seats are now in the hands of forces loyal to Beijing. Only one seat was won by a Beijing critic.

For many, however, the first election since the suppression of the democracy movement was a charade. Under a controversial new electoral system, almost all pro-democracy representatives were excluded from the election, and only “patriots” loyal to Beijing were allowed to run. As a result, the majority of Hong Kong’s voters stayed away from Sunday’s election in protest. According to official figures, only around 30 percent of eligible voters cast their ballots – about half as many as in the previous parliamentary election in 2016. According to observers, the people of Hong Kong sent a signal against China’s restrictions on democracy with the lowest voter turnout since 1997.

Under the new electoral system, only 20 of the 90 members of the Legislative Council were directly elected. 40 were chosen by an electoral committee loyal to Beijing, and 30 others by interest groups also close to the Chinese central government. All 153 candidates were also screened for “patriotism” and political loyalty to Beijing before voting.

As a result, the main pro-democracy parties did not field candidates. Dozens of prominent opposition figures – including many who had won seats in parliament in the last election – were detained, barred from voting, or fled the city for violations of the so-called National Security Law.

Despite this, Hong Kong’s chief executive Carrie Lam praised the ballot on Monday. The ballot was “fair, impartial and open” and the entire breadth of society was represented in the new parliament. Lam rejected criticism of the election system and the pre-selection of candidates. When 1.3 million people vote, she said, it could not be said to have been an election that was not supported by citizens. “People still need time to get used to the new election system,” Lam said.

Beijing struck a similar tone on Monday. The document, “Hong Kong: Democratic Progress Under the Framework of One Country, Two Systems,” praised the election and the new electoral system as an improved system that would guarantee the long-term development of democracy in Hong Kong. Looking ahead, it says: “We will continue to take more solid steps to advance democracy in the right direction with greater confidence.” rad

China’s “Queen of Livestreaming” must pay a fine in the millions for tax evasion. Blogger Viya, whose real name is Huang Wei, was ordered to pay ¥1.3 billion (€180 million), Reuters reported Monday, citing China’s tax authorities. She is alleged to have misreported her income in 2019 and 2020, among other things. The 36-year-old publicly apologized: She is accused of falsely declaring her income in 2019 and 2020, among other things. The 36-year-old publicly apologized: “I’m deeply sorry about my violations of the tax laws and regulations,” she said on her Weibo account. “I thoroughly accept the punishment made by the tax authorities.”

Viya rose to fame through her live sales streams on Taobao. During the online shopping day known as Singles’ Day in November, she sold products worth a total of ¥8.5 billion in just one evening, according to media reports.

Viya is just the latest case of a publicly denounced celebrity. The Beijing government is currently cracking down not only on tech companies and platforms but also on celebrities who the CCP deems not to be complying with the rules (China.Table reported). Crackdowns on tax evasion had already ended the careers of other well-known entertainment personalities. ari/rtr

China’s central bank has cut a key interest rate to inject more liquidity into the country’s shaky financial markets. The Prime Lending Rate (LPR) fell to 3.8 percent from 3.85 percent. It was the first rate cut by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) in nearly two years. Chinese monetary policy is thus running counter to the trend in the US. There, the central bank is aiming to increase the interest rate level due to inflation. The reason for the PBoC’s interest rate cut is said to be the continuing uncertainties in the Chinese real estate market. After the residential construction group Evergrande, its competitor Kaisa is also experiencing increasing difficulties. fin

She wore fashionable glasses, had subtly applied lipstick, and looked directly into the camera. That was one of the last impressions of Hayrigul Niyaz on social media before she disappeared. She had returned from studying abroad in Turkey shortly before and had opened a travel agency in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. Her stay in Turkey was apparently reason enough for the Chinese authorities to arrest her. Police officers showed up at her home and took her away. That was in 2017.

Her brother Memeteli, who is a refugee in Germany, suspects that she is being held in a prison or internment camp. The rest of the family also has no contact with her and knows nothing about her whereabouts. The organization Amnesty International is now campaigning worldwide for the release of Hayrigul Niyaz.

Hayrigul Niyaz was born and grew up in the city of Toksu on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Unlike in the provincial capital of Urumqi, for example, the Uyghurs still make up the majority of the population there. This is a thorn in the side of the government in Beijing, which is why it encourages the influx of Han Chinese into the region. Niyaz, however, was drawn away from Toksu early on. She made it to the open world: she went to study at Marmara University in Istanbul.

Hayrigul Niyaz, who is 35 years old today, is considered a cheerful person by her peers. She enjoys traveling and skiing. In addition to Uyghur and Mandarin, she also speaks Russian, English, and Turkish. She wanted to use this international experience when she returned to China in 2016 and opened her own business in Urumqi.

Her sudden disappearance now sheds light on the injustices of the police state in Xinjiang. “We are typical Uyghurs, religion is part of our identity, but we are not ultra-religious people,” Memeteli says. It’s not about religion for the leadership in Beijing, he says, but about eradicating Uyghur identity.

What is fairly certain is that Hayrigul Niyaz has no legal counsel. She also has no access to communication. In April 2020, her brother spoke to family members in Xinjiang. But the conversation was arranged and monitored by the police. When Memeteli refused to give authorities additional information about his sister, they responded with threats. Since then, all contact has been severed – including with the other family members.

Like Hayrigul Niyaz and her family, many Uyghurs are currently suffering. The UN Human Rights Committee suspects that the Chinese authorities have temporarily detained hundreds of thousands of people in internment and re-education camps over the past four years. The Chinese leadership does not publish official figures. The communist leadership in Beijing officially accuses only some Uyghur groups of separatism and terrorism. But for a long time now, around ten million Uyghurs in the province of Xinjiang have been under general suspicion. Felix Lee

Jean-Philippe Parain will take over responsibility for the sales regions Asia-Pacific, Eastern Europe, Middle East, and Africa at BMW from April 1, 2022. He succeeds Hendrik von Kuenheim.

Ritu Chandy, previously Regional CEO for Asia Pacific at BMW Financial Services, will become Head of Group Finance at BMW from April 1.

Although China’s New Year is in February, preparations are already in full swing in the People’s Republic. In Loudi, in the province of Hunan, several red lanterns are hung for drying to light up the Year of the Tiger.

Germany’s new government has only been in office for a few days – and several conflicts with China are already on the horizon. In the first case, German companies, such as the automotive supplier Continental, are caught between the fronts in what was a solely political dispute at first. This is why, at the beginning of the week, the Federation of German Industries warned Beijing of a “disastrous own goal“. The German Chamber of Commerce in China even addressed a letter to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce. For the latest developments, please see our News section.

The second case is about the grand plans of the new German government: Expanding solar power – and simultaneously ensuring human rights in global supply chains. A difficult task. After all, there has long been no way past the global market leader China in the solar power sector. And, according to experts, the People’s Republic produces the raw material for solar panels in Xinjiang under forced labor. In such cases, discussions about sanctions quickly emerge. But they lead to a dead-end, as Nico Beckert analyses.

And even sport is not immune to political conflict. For the first time, Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai has spoken about her allegations of sexual assault against a senior party official. Marcel Grzanna has taken a closer look at the interview. To him, the tennis player’s statements seem like pretend subterfuge. This makes Peng Shuai’s case seem like the latest part in the history of how the Chinese government deals with its dissidents, activists, and critics.

The new federal government has a number of plans for the expansion of renewable powers. It wants to mount solar power on “all suitable roofs”. By 2030, “around 200 gigawatts” of photovoltaic capacity are to be achieved. This means a quadrupling of the current capacity. To achieve this, the traffic light coalition wants to remove many “hurdles to expansion”. This is what the coalition agreement says.

One major hurdle that is not mentioned, is the supply chain of the solar industry. A large part of the basic material of solar cells, polysilicon, is produced in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. However, there are accusations that this polysilicon is produced through forced labor by the Uyghur ethnic group. This poses considerable problems if ethical standards are to apply to this supply chain in the future.

Recently, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock announced a clearer policy against human rights violations in China. “If products from regions like Xinjiang, where forced labor is common practice, are blocked, that’s a big problem for an exporting country like China,” she said in an interview with taz and China.Table.

But it is not only China, who would then face a problem. The expansion of solar energy in Germany could also come to a grinding halt. Much of the polysilicon is processed directly in China. The People’s Republic is the global market leader in the solar sector and dominates all production steps. Worldwide, three out of four solar modules and 83 percent of solar cells are produced in China. China dominates 77 percent of the global market for polysilicon. Xinjiang again plays a special role here. An estimated 50 percent of global polysilicon production is located in the western Chinese region.

Large amounts of power are required for the production of polysilicon and its precursor silicon metal. Xinjiang has an abundance of it. There is hardly any other part of the country where power and process heat for the production of polysilicon is so cheap. Four of the world’s largest manufacturers have factories in Xinjiang, according to an analysis by Bloomberg. Three producers have been accused of using forced labor in their factories.

The allegations are based on reports by consulting firms Horizon Advisory and S&P Global Market Intelligence, as well as research by Xinjiang researcher Adrian Zenz. They independently conclude that hundreds of forced laborers are involved in the production of polysilicon. A Bloomberg research team was denied access to the factories. The journalists have not been allowed to examine the production and interpret this as a sign that the manufacturers have something to hide.

Other experts, however, give the all-clear in part. True, China’s global market share looks very high on paper. But a large part of it remains domestic. No other country installs as many solar modules as China. A large part of the domestic production is therefore not exported in the first place.

Moreover, the other half of China’s production is produced outside Xinjiang. Together with manufacturing in other regions of the world, there are enough solar modules to meet demand. “The US and Europe together accounted for about 30 percent of new global PV installations in 2020,” says market observer Johannes Bernreuter of consulting firm Bernreuter Research. “So arithmetically, there is enough polysilicon for the US and Europe right now that is not affected by Xinjiang.”

Surprisingly, neither the EU’s statistical authority (Eurostat) nor the Federal Statistical Office have any data on how many solar cells and modules Germany imports from China.

But when Western buyers acquire solar cells and modules from China, they have so far been faced with a problem: polysilicon from various sources is mixed during production. It could very well be that basic material from Xinjiang is also included, which was produced through forced labor. However, Chinese manufacturers are adapting to the needs of the West. Some companies are likely producing Xinjiang-free segments and using them in their solar modules for export to the US and Europe, Bernreuter explains. “They can also provide plausible documents that the solar modules and cells do not contain any primary products from Xinjiang.”

This could mean that material flows could simply be split: Xinjiang-free products are manufactured for export. Solar modules, whose raw material is produced through forced labor, continue to be installed in China due to the high domestic demand. Western sanctions and boycotts of polysilicon from Xinjiang would thus have little effect. Bernreuter criticizes: “To put it bluntly: The West eases its conscience, but the Uyghurs are not better off.” However, one should not underestimate sanctions as a political signal, Bernreuter adds.

Another problem in the solar supply chain is the basic material for polysilicon: so-called metallurgical-grade silicon. The Chinese manufacturers of this highly pure silicon have no interest in transparency. So importers can hardly be sure that no forced labor is involved in the production of metallurgical-grade silicon. This is the reason why some Western and Asian manufacturers of polysilicon have already terminated their business relations with the largest producer of metallurgical silicon, Hoshine Silicon from Xinjiang. In addition, the US Customs Service has taken action against Hoshine. There is information that the company uses forced labor, the agency said. Products from Hoshine are confiscated by customs at US ports.

However, this by no means resolves the situation. The US is currently discussing additional measures to exclude forced labor in Xinjiang in imported products. As these go far beyond current measures, it would further reduce the number of basic materials that can be imported legally. Recently, the US House of Representatives and the Senate passed a bill that would place all products from Xinjiang under suspicion of being produced by forced labor (China.Table reported).

This reverses the burden of proof. Imports would then be banned as long as the US government is not presented with verifiable evidence that forced labor was not involved in the production. US President Biden still has to approve the bill. Republicans accuse Biden of filibustering, stating that the law would make it harder to expand renewable power. Biden’s plans to expand solar power are similarly ambitious to those of the new German government. By 2050, about half of US electricity is to be generated by solar power. Currently, it is only four percent.

But experts say the US law could prove to be ineffective for the solar supply chain. If the US bill is signed into law next year, Chinese manufacturers will already be prepared. “We expect that solar wafer manufacturers, all of which are located in China, will then be able to separate supply chains for different markets,” says Jenny Chase of Bloomberg NEF, confirming the suspicions of polysilicon expert Bernreuter. Another question will be whether buyer countries will simply believe the suppliers’ claims of origin.

Solar supply chains are currently still so complex that it is difficult to manufacture truly Xinjiang-free solar modules and cells. Industry expert Bernreuter, therefore, advises the industry to play it safe and become less dependent on China. “There is no way around building new solar supply chains outside of China.” This could increase the price of the modules by about ten percent. “If environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) criteria are more than just lip service to them, investors and consumers must be prepared to pay this price,” says Bernreuter.

The new German government also signaled China.Table that it intends to take action. The German Foreign Office states that the government wants to “support a possible import ban on products from forced labor at the European level”. Likewise, the European supply chain law is to be “supported.” However, a clear stand against forced labor in Xinjiang sounds different.

World-class Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai has distanced herself from her rape allegations against former Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli. A roughly four-minute-long video from last Sunday, which has been circulating on social media since the start of the week, shows the 35-year-old talking to a Singaporean journalist. In it, Peng stated that “I have never said that I wrote that anyone sexually assaulted me”.

The statement is the opposite of what has escalated into a global political issue since early November. At that time, Peng had accused former government official Zhang on short message service Weibo of forcing her to have sex. After 30 minutes, the post was deleted again. After that, the athlete even disappeared for several weeks. As a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, Zhang belonged to the Communist Party’s innermost circle of power until 2017.

“About the Weibo [post], it’s a private matter. There seems to have been a lot of misinterpretation from the public,” Peng said on Sunday. The interview, which supposedly was not planned, was her first public verbal statement about what had happened. Previously, only written statements had surfaced, but it was not clear whether Peng had written it herself.

She confirmed to the reporter of the daily newspaper Lianhe Zaobao, that she had indeed written the letter to the head of the Women’s Tennis Association WTA, Steve Simon. In the letter, Peng asked Simon to respect her privacy after the official threatened consequences for China as a tennis venue and demanded clarification from the Chinese authorities. Peng admitted that she had drafted the letter in Chinese before it was translated into English. She explained that her English was not good enough.

But the new video is also not convincing many skeptics. Peng looks around nervously at times, responds to several questions saying she didn’t understand them properly, and when it came to the most important part of the interview, she chooses her words very slowly and carefully. The WTA commented that “these appearances do not alleviate or address the WTA’s significant concerns about her wellbeing and ability to communicate without censorship or coercion.”

The poor track record of the way the Chinese government deals with dissidents, activists, or critics in its own country causes doubts. The human rights organization Safeguard Defenders referred to a 2018 publication entitled “Scripted and Staged”, which examines similar cases in which the accused first disappeared and then publicly apologized after their reappearance.

Safeguard director Peter Dahlin also questioned Peng’s claim that her English language skills were not good enough to write to the WTA director in English. He posted a video of a press conference in which the former Wimbledon doubles champion responds to journalists’ questions in fluent English.

Human rights lawyer Teng Biao, who was once tortured while being detained by Chinese security authorities and now lives in exile in the US, also doubts that Peng’s statements were voluntary. On Twitter, Biao wrote: “The world has been discussing it for 47 days, nobody was able to reach her out except the Party/its puppets. Needs 47 days to say she’d been misunderstood?”

Especially since Peng claims in the video, which was made in Shanghai on the sidelines of a promotional event for February’s Winter Olympics in Beijing, that she was able to “move freely”, it begs the question of why she did not appear in public sooner to prevent an escalation.

After all, her case was the breaking point for numerous Western governments. Led by the US, nearly two dozen Western nations have already announced that they will not send a delegation to the Olympics.

At the same time, the WTA has suspended all its tournaments in the People’s Republic and Hong Kong until further notice. So Peng could have done some early damage control if she was indeed free to move and express herself as she now claims. Instead, tensions between China and many democratic countries intensified while she remained silent.

Wang Yaqiu of Human Rights Watch (HRW) even doubts that the interview with the Singaporean journalist was a coincidence. “So, after 48 days, Peng Shuai unexpectedly encountered a journalist from a pro-Beijing newspaper and then casually answered her questions about an event that garnered huge international attention. Wow, so natural, very real, everyone now believes it. Congratulations, the CCP!” Wang wrote on Twitter.

The Chinese side, on the other hand, tried to bolster the credibility of the statement. Former editor-in-chief and current chief columnist of the state-run Global Times newspaper, Hu Xijin, wrote “Peng Shuai firmly opposed use of ‘sexual assault’ to interpret what she described in her post, and denied she thought she was sexually assaulted. The outside world should respect this basic attitude of her.” In plain English, this means that Peng never saw herself as a victim of sexual assault, but that third parties merely misinterpreted her post.

German business representatives are taking an increasingly critical stance in the trade conflict between Lithuania and China, thus also increasing the pressure on Berlin. The Federation of German Industries (BDI) is now accusing Beijing of scoring a “disastrous own goal”. “China’s latest measures against Lithuania are having the effect of a trade boycott with repercussions for the entire EU,” the BDI announced. “Imports from China that are needed in German production facilities in Lithuania and exports from Germany to China that contain Lithuanian components are also affected” This action shows that China is willing to “economically decouple itself from politically disagreeable partners”. Nevertheless, it would be important to maintain economic relations with China at a high level.

The German Chamber of Commerce in China also intervened: “A quick solution” must be found “to enable the smooth import of products and parts from the entire EU to China, as well as export to the EU”, the statement reads. The chamber also wrote to China’s Ministry of Commerce. “For some time now, we have been concerned about the increasing politicization of economic relations. De facto trade barriers, such as we are now seeing about imports and exports from Lithuania, do more harm than good.”

China has been blocking imports from Lithuania since the beginning of the month. The EU state disappeared from the customs system. Since last week, German automotive companies cooperating with Lithuanian suppliers have also been affected (China.Table reported), including Continental and, according to FT, Lippstadt-based Hella.

The EU stated that it is currently gathering material for a possible complaint to the World Trade Organization. Gathering the necessary information will not be easy, however, as China has never officially spoken of a blockade of Lithuania in its customs system. Moreover, companies that now speak out against the People’s Republic fear long-term exclusion from the Chinese market or other reprisals. ari

Pro-Beijing candidates achieved an overwhelming victory in Sunday’s parliamentary election in Hong Kong. 82 of the 90 parliamentary seats are now in the hands of forces loyal to Beijing. Only one seat was won by a Beijing critic.

For many, however, the first election since the suppression of the democracy movement was a charade. Under a controversial new electoral system, almost all pro-democracy representatives were excluded from the election, and only “patriots” loyal to Beijing were allowed to run. As a result, the majority of Hong Kong’s voters stayed away from Sunday’s election in protest. According to official figures, only around 30 percent of eligible voters cast their ballots – about half as many as in the previous parliamentary election in 2016. According to observers, the people of Hong Kong sent a signal against China’s restrictions on democracy with the lowest voter turnout since 1997.

Under the new electoral system, only 20 of the 90 members of the Legislative Council were directly elected. 40 were chosen by an electoral committee loyal to Beijing, and 30 others by interest groups also close to the Chinese central government. All 153 candidates were also screened for “patriotism” and political loyalty to Beijing before voting.

As a result, the main pro-democracy parties did not field candidates. Dozens of prominent opposition figures – including many who had won seats in parliament in the last election – were detained, barred from voting, or fled the city for violations of the so-called National Security Law.

Despite this, Hong Kong’s chief executive Carrie Lam praised the ballot on Monday. The ballot was “fair, impartial and open” and the entire breadth of society was represented in the new parliament. Lam rejected criticism of the election system and the pre-selection of candidates. When 1.3 million people vote, she said, it could not be said to have been an election that was not supported by citizens. “People still need time to get used to the new election system,” Lam said.

Beijing struck a similar tone on Monday. The document, “Hong Kong: Democratic Progress Under the Framework of One Country, Two Systems,” praised the election and the new electoral system as an improved system that would guarantee the long-term development of democracy in Hong Kong. Looking ahead, it says: “We will continue to take more solid steps to advance democracy in the right direction with greater confidence.” rad

China’s “Queen of Livestreaming” must pay a fine in the millions for tax evasion. Blogger Viya, whose real name is Huang Wei, was ordered to pay ¥1.3 billion (€180 million), Reuters reported Monday, citing China’s tax authorities. She is alleged to have misreported her income in 2019 and 2020, among other things. The 36-year-old publicly apologized: She is accused of falsely declaring her income in 2019 and 2020, among other things. The 36-year-old publicly apologized: “I’m deeply sorry about my violations of the tax laws and regulations,” she said on her Weibo account. “I thoroughly accept the punishment made by the tax authorities.”

Viya rose to fame through her live sales streams on Taobao. During the online shopping day known as Singles’ Day in November, she sold products worth a total of ¥8.5 billion in just one evening, according to media reports.

Viya is just the latest case of a publicly denounced celebrity. The Beijing government is currently cracking down not only on tech companies and platforms but also on celebrities who the CCP deems not to be complying with the rules (China.Table reported). Crackdowns on tax evasion had already ended the careers of other well-known entertainment personalities. ari/rtr

China’s central bank has cut a key interest rate to inject more liquidity into the country’s shaky financial markets. The Prime Lending Rate (LPR) fell to 3.8 percent from 3.85 percent. It was the first rate cut by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) in nearly two years. Chinese monetary policy is thus running counter to the trend in the US. There, the central bank is aiming to increase the interest rate level due to inflation. The reason for the PBoC’s interest rate cut is said to be the continuing uncertainties in the Chinese real estate market. After the residential construction group Evergrande, its competitor Kaisa is also experiencing increasing difficulties. fin

She wore fashionable glasses, had subtly applied lipstick, and looked directly into the camera. That was one of the last impressions of Hayrigul Niyaz on social media before she disappeared. She had returned from studying abroad in Turkey shortly before and had opened a travel agency in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. Her stay in Turkey was apparently reason enough for the Chinese authorities to arrest her. Police officers showed up at her home and took her away. That was in 2017.

Her brother Memeteli, who is a refugee in Germany, suspects that she is being held in a prison or internment camp. The rest of the family also has no contact with her and knows nothing about her whereabouts. The organization Amnesty International is now campaigning worldwide for the release of Hayrigul Niyaz.

Hayrigul Niyaz was born and grew up in the city of Toksu on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Unlike in the provincial capital of Urumqi, for example, the Uyghurs still make up the majority of the population there. This is a thorn in the side of the government in Beijing, which is why it encourages the influx of Han Chinese into the region. Niyaz, however, was drawn away from Toksu early on. She made it to the open world: she went to study at Marmara University in Istanbul.

Hayrigul Niyaz, who is 35 years old today, is considered a cheerful person by her peers. She enjoys traveling and skiing. In addition to Uyghur and Mandarin, she also speaks Russian, English, and Turkish. She wanted to use this international experience when she returned to China in 2016 and opened her own business in Urumqi.

Her sudden disappearance now sheds light on the injustices of the police state in Xinjiang. “We are typical Uyghurs, religion is part of our identity, but we are not ultra-religious people,” Memeteli says. It’s not about religion for the leadership in Beijing, he says, but about eradicating Uyghur identity.

What is fairly certain is that Hayrigul Niyaz has no legal counsel. She also has no access to communication. In April 2020, her brother spoke to family members in Xinjiang. But the conversation was arranged and monitored by the police. When Memeteli refused to give authorities additional information about his sister, they responded with threats. Since then, all contact has been severed – including with the other family members.

Like Hayrigul Niyaz and her family, many Uyghurs are currently suffering. The UN Human Rights Committee suspects that the Chinese authorities have temporarily detained hundreds of thousands of people in internment and re-education camps over the past four years. The Chinese leadership does not publish official figures. The communist leadership in Beijing officially accuses only some Uyghur groups of separatism and terrorism. But for a long time now, around ten million Uyghurs in the province of Xinjiang have been under general suspicion. Felix Lee

Jean-Philippe Parain will take over responsibility for the sales regions Asia-Pacific, Eastern Europe, Middle East, and Africa at BMW from April 1, 2022. He succeeds Hendrik von Kuenheim.

Ritu Chandy, previously Regional CEO for Asia Pacific at BMW Financial Services, will become Head of Group Finance at BMW from April 1.

Although China’s New Year is in February, preparations are already in full swing in the People’s Republic. In Loudi, in the province of Hunan, several red lanterns are hung for drying to light up the Year of the Tiger.