It’s a shame that dreams sometimes have to be so complicated! Xi Jinping’s vision of “common prosperity” is a noble goal, but unfortunately, the less-than-rosy reality stands in the way: Bank protests, meager growth figures, enraged real estate buyers, disappointed graduates slipping from college straight into record unemployment. The problems are piling up, as our author Fabian Kretschmer analyzes from Beijing. And all this just a few months before the Party Congress that is to usher in Xi Jinping’s third term in office.

And the gas issue is not exactly a dream either. China actually sits on huge shale gas deposits. These could help supply the country with power and offer an alternative to coal, which China’s energy supply still heavily depends on. But fracking is not only harmful to the environment, but it is also extremely difficult in China. Geographical conditions make it complicated, expensive, and could even cause earthquakes. In Sichuan, earthquakes damaged some 20,000 homes in 2019, killing two people and prompting protests. Still, China continues to rely on fracking. Nico Beckert analyzes its prospects.

Johnny Erling introduces you today to the heralds of diplomatic relations between the Federal Republic of Germany and China. A Chinese journalist and an opposition politician from the CDU initiated diplomatic contact 50 years ago: Gerhard Schroeder and Wang Shu. In the fall of 1972, Beijing and Bonn sealed their intentions in a communiqué with just one sentence. Something diplomats can only dream of today.

What has happened to several thousand small savers in China’s central province of Henan may have shaken their worldview to the core. For months, they have been unable to access their bank accounts after four regional banks froze them in the wake of an alleged speculation scandal (China.Table reported).

The banking scandal in Henan may only involve a relatively small sum in economic terms. Nevertheless, it has stirred up a primal fear among the population. Since the beginning of the country’s economic opening, society has been held together by a silent agreement: The Chinese willingly surrender their claim to a political say as long as the party leadership in Beijing ensures a steady rise of material living standards. And for decades, the plan worked perfectly: Between 1978, the beginning of Deng Xiaoping’s reform policy, and Xi Jinping’s inauguration in 2013, China’s gross domestic product increased more than 64-fold.

But the tide has turned completely in the wake of the dogmatic “zero-Covid” policy at the latest. Economic growth has virtually ground to a halt: Between April and June, the gross domestic product grew by only 0.4 percent year-on-year. Compared to the first quarter of the year, the world’s second-largest economy actually shrank by 2.6 percent. The immediate effects of the impending recession are beginning to show more and more clearly. In the overheated real estate sector, a central pillar of the domestic economy, a downward spiral is already impending: Currently, tens of thousands of Chinese are threatening to stop making their mortgage payments because their apartment buildings are sitting around unfinished. (China.Table reported).

At the same time, youth unemployment in China’s cities is at a record high: Almost one in five Chinese between the ages of 16 and 24 currently has no income. This year alone, with almost eleven million university graduates, more young people are entering the job market than ever before. Despite having good qualifications, many of them will have to settle for precarious odd jobs. According to a forecast by the US bank Merrill Lynch, youth unemployment could rise to as much as 23 percent this year. The economic predicament is to a large extent homemade. Beijing’s excessive regulatory wave against the tech industry, which after all has produced the country’s most internationally successful corporations, led to unprecedented mass layoffs last year.

Without doubt, Xi Jinping is facing the greatest challenge in his political career to date, shortly before the end of his second term in office. After all, the 69-year-old took office with the vision of making Chinese society fairer and more just. “Common prosperity” is the propagated paradigm shift touted by Xi in virtually every one of his speeches. The concept is also a reaction to the gold-rush mentality of the 2000s, when China’s gross domestic product grew by double-digit percentages, but at the same time corruption, excessive wealth and radical inequality surged.

But so far, Xi Jinping’s vision of “common prosperity” is nothing more than a vague expression. The measures announced by China’s head of state so far seem more populist than sustainable: Companies have been ordered to return more excess profits to the general public in the form of philanthropic donations, and banks are to curb the “excessive” salaries of their executive boards (China.Table reported).

Just how far the People’s Republic is from “common prosperity” was recently revealed by the latest data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China. More than 960 million of 1.4 billion Chinese live on a monthly income of less than ¥2,000, which is less than €290. The weak income share of the population of the gross domestic product also reveals the economic Achilles heel of the Chinese economy: The weakening domestic consumption.

This results in a correspondingly high risk that China could get caught in the so-called “middle income trap,” from which only a handful of former developing countries – first and foremost South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore – have managed to escape. The rapid growth of the People’s Republic of China was based not least on a cheap labor force, coupled with a government that massively invested its rich financial savings in infrastructure, technology and production capacities.

But this economic model will soon reach its limits: In order to achieve sustainable growth, the country would have to readjust its income distribution and thus boost domestic consumption. However, the necessary reforms would trigger a painful transition process, which the government, concerned about social stability, is probably right to fear.

But the window of opportunity for China is slowly closing: Demographic change is advancing rapidly, while the birth rate is at a record low. As a result, the flattening of annual growth rates is currently setting in far too early: After all, despite the remarkable rise of the People’s Republic of China, it has only reached one-third of the GDP per capita levels in South Korea and one-eighth of Switzerland’s. Fabian Kretschmer

Germany’s Minister of Finance, Christian Lindner, recently spoke out in favor of fracking in northern Germany. In some cases, he said, fracking is “reasonable”. The extraction of gas deposits in the North Sea is also “sensible and feasible,” Lindner told German media.

Fracking technology has brought the USA a gas boom. The country is now a net gas exporter. In Germany, the decision to lift the ban on this controversial extraction method has been under discussion for several weeks. The looming gas crisis following the Russian war in Ukraine has made the issue relevant once again. In China, fracking has been used for many years. Shale gas is expected to contribute to the country’s energy supply and reduce its dependence on coal. This would also benefit the country’s climate goals; after all, coal still dominates the electricity mix.

According to some estimates, China possesses the world’s largest shale gas reserves. In 2013, the US Department of Energy estimated that Chinese reserves were almost twice as large as those of the USA. A year earlier, authorities issued an ambitious target: Annual production was to rise to between 60 and 100 billion cubic meters by 2020. But the targets were missed by a wide margin. In 2020, only 20 billion cubic meters were extracted. Even the revised target of 30 billion was not achieved. Local protests are only one reason for this.

Sichuan has experienced earthquakes as a result of the fracking boom. The province has the largest exploitable deposits. Several incidents occurred in 2019. Thousands of residents in the region protested in front of the Rong district government building at the time. They blamed the fracking industry for the earthquakes. The quakes killed two people and injured 13. 20,000 buildings were damaged and nine collapsed entirely, the New York Times reported. Following the protests, fracking was suspended in the district. But authorities deny a link between the controversial gas extraction and the earthquakes.

More problems could also arise with water in the future. Fracking, which involves injecting a mixture of water, sand and chemicals into the rock under high pressure, requires a lot of water. Meanwhile, there is a shortage of water in some regions of Sichuan. In addition, the province is densely populated. The fracking industry can hardly avoid the local population. Conflicts are inevitable.

China has the largest treasure trove of shale gas – but has a hard time reaching it. The reserves lie at greater depths than in the USA. In the largest gas region in Sichuan, gas companies have to drill to depths of over 4,500 meters – about twice as deep as in the USA. This also increases production costs. According to consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, a deep shale well costs $9 million, two million more than a medium-depth drill. In addition, China’s deposits are not as concentrated as those in the US, and Sichuan is very mountainous. But fracking towers have to be placed on even ground, and pipelines are also difficult to build in the mountains.

All these challenges are driving up costs. According to PetroChina, shale gas fracking costs 20 to 30 percent more than extracting conventional resources. “Highly complex above and below-ground challenges mean that the Chinese shale gas journey will continue to look very different from that in the US,” says Zhang Xianhui of consulting firm Wood Mackenzie.

International oil and gas companies such as BP, ExxonMobil, Shell, ConocoPhillips and Eni have withdrawn from fracking shale gas in China over the years. In 2009, they entered the market with high hopes for a fracking boom. But reality quickly caught up with the companies. Fracking was simply not profitable. After the withdrawal of the international corporations, PetroChina and Sinopec have to bear the costs of the fracking infrastructure alone.

The only international cooperation still exists for so-called tight gas in the Ordos Plateau in northwestern China, which has to be fracked from dense rock strata. But here, too, are problems: Yields from individual wells are quite low, so thousands of holes need to be drilled and connected to pipelines and other infrastructure. That drives up costs.

Despite high hopes from authorities, the fracking boom in the People’s Republic has so far failed to materialize. In recent years, production has been increased to 23 billion cubic meters (2021). Various analysts estimate that China could reach production of 50 to 60 billion cubic meters in 2035. But some experts believe that this would already be the maximum.

Today, China already consumes 372 billion cubic meters of gas, Wood Mackenzie experts told China.Table. They assume that production could continue to rise after 2035. But fracking will continue to contribute only a small share of gas supply. Chinese production pales in comparison to the annual production of shale gas in the United States with approximately 700 billion cubic meters. However, every cubic meter of gas produced in China reduces dependence on foreign countries and contributes to the goal of energy security. But the problems for local residents affected by earthquakes remain. Cooperation Renxiu Zhao

The US intelligence agency CIA considers the likelihood of a violent incursion by Chinese forces into Taiwan to be high. It is not a question of “whether” Chinese leaders might decide to “use force to control Taiwan” in a few years, but rather “how and when they will do it,” CIA chief William Burns said on Wednesday at the Aspen Security Forum. “The risks of that become higher, it seems to us, the further into this decade that you get.”

The leadership in Beijing has learned its lessons from Russia’s “strategic failure” in Ukraine, Burns added. “You don’t achieve quick, decisive victories with underwhelming force.” In addition, China has learned that it must extensively safeguard its economy against sanctions. Burns, however, does not believe that Beijing is currently providing military assistance to Russia.

Chinese Ambassador to the United States Qin Gang told the forum in the Rocky Mountains that Beijing still seeks “peaceful reunification.” At the same time, he accused the United States of supporting “independence forces” in Taiwan. The US is “hollowing out and blurring” its commitment to Beijing’s “One-China” policy. “Only by adhering strictly to the one-China policy, only by joining hands to constrain and oppose Taiwan independence, can we have a peaceful reunification,” Qin said. fpe

HSBC Qianhai Securities has apparently become the first foreign lender in China to appoint a Party committee. This was reported by the Financial Times, citing two sources familiar with the decision. According to the report, the bank did not initially comment on the matter. However, informed individuals reportedly said that the committee has been set up in early July and does not have a management role.

HSBC Qianhai is the investment banking arm of HSBC in China. HSBC is headquartered in London, with a large part of its profits generated in Hong Kong. The financial institution plans to expand rapidly in mainland China as well. In April, it increased its stake in the Qianhai Securities joint venture from 51 to 90 percent.

HSBC’s decision could have an impact on other foreign banks in China. There is no word yet on Party committees at the other six foreign investment banks operating in China. Goldman Sachs, however, has already hired several Party members for senior positions, including the former head of its China unit, Fred Hu. And Swiss bank UBS also brought Fan Yang onto its team in 2020 as Head of Global Banking for Asia. She is the daughter of former Chinese Vice Premier Liu Yandong.

By law, companies in China are required to employ a Party cell of at least three employees who are members of the Communist Party. This also applies to foreign joint ventures. Among foreign financial institutions, however, the requirement has not yet been enforced. Party committees have a social function in companies, but can also serve the purpose of influencing strategic decisions. jul

Military engineers from Beijing have developed a smaller, less expensive version of Russia’s “Poseidon” underwater drone. Like its Russian counterpart, the weapon is powered by a disposable nuclear reactor, reports the South China Morning Post. It is designed to provide the torpedo with a range of 10,000 kilometers. That is roughly equivalent to the range of an intercontinental ballistic missile. AI technologies such as machine learning are expected to allow the weapon to attack targets underwater with little or no human involvement.

According to lead researcher Guo Jian of China’s Institute of Atomic Energy, there is a growing demand for small, high-speed, long-range unmanned underwater vehicles that can be used for reconnaissance, detection, attack and strategic strikes. The smaller size means the smart torpedo drone can be launched from almost any submarine or warship. Its low cost makes it suitable for mass production, unlike its Russian counterpart, and it could be deployed in veritable swarms, according to Ma Liang of the Navy Submarine Academy in Qingdao.

For their design, the project team removed expensive shielding materials. Only the critical components would still be protected from radiation. The engineers also replaced expensive rare-earth coatings inside the reactor core with inexpensive materials such as graphite. To further cut costs, the scientists also propose using commercially available tech components instead of military-grade products. fpe

China’s semiconductor manufacturer SMIC has made substantial progress in domestic semiconductor production despite US sanctions, according to an industry report. Reportedly, SMIC has been shipping its first 7 nm chips since last year. Although these are primarily used for niche products, they show that the People’s Republic semiconductor production is already more advanced than expected, analysts at TechInsights explained. “Despite not having access to the most advanced equipment technologies as a result of sanctions currently in place, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) appears to have used 7 nm technology to manufacture the MinerVa Bitcoin Miner system on chip (SoC),” the tech analysts wrote.

Since the end of 2020, the US has prohibited the unlicensed sale of equipment that can be used to manufacture semiconductors with 10 nm and above to the Chinese company. What is also interesting is that according to the analysts, the technology discovered from SMIC is probably a fairly close copy of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s (TSMC) N7 process. TSMC and SMIC were already in a clash some time ago over allegedly stolen technologies by the Chinese company.

SMIC’s surprising progress raises questions about the effectiveness of the US export control mechanism and whether Washington can actually thwart China’s ambitions to develop a domestic world-class chip industry. ari

Exactly 50 years ago, in the penultimate week of July 1972, Bonn and Beijing began to establish diplomatic relations. But not in a very straightforward way. And that was no accident. One of the people behind it was an opposition politician from the CDU and, on the Chinese side, a Xinhua journalist in Bonn. The unusual actors jumped over their shadows and, just eleven weeks later, the Federal Republic and the People’s Republic sealed their new relationship with an official document. It is also called the shortest communiqué in China’s diplomatic history.

Wang Shu (王殊) head of the news agency Xinhua (New China) office in Bonn, showed no sign of his nervousness. His meeting with CDU politician Gerhard Schroeder – not to be confused with his namesake from Lower Saxony and later German chancellor – had already lasted more than three hours. But the one phrase he was waiting for did not pass his interlocutor’s lips.

It was February 21, 1972, and an SPD-FDP coalition was governing the Federal Republic. Opposition man Schröder, who had once served as Foreign and Minister of Defense for the CDU/CSU, was presiding over the Bundestag’s Foreign Affairs Committee. “We talked about the global situation,” Wang recalled. “But all I could think was, ‘When is he going to ask me?’ It was already getting dark outside.” Eventually, he dropped all politeness. “I interrupted Schröder. Would he be interested in visiting China in the near future?” His counterpart immediately responded, “Very much so, and if possible during this summer break.”

When Wang told me the anecdote 25 years later in 1997, he shook with laughter and still pretended to be indignant: “Was that a waste of time! And only because Schroeder was too posh to ask first.”

Wang’s task was to find out whether an invitation to Schroeder would bring China closer to its goal of establishing diplomatic relations with Germany. Actually, Schroeder was not the right man since belonged to the opposition. The SPD-FDP coalition led by Willy Brandt, however, kept a low profile regarding contacts with China in order not to burden its “New Eastern Policy” of reconciliation with Moscow and East Berlin.

Beijing’s policy of fiercely attacking Moscow and playing rapprochement ping-pong with the United States sparked fantasies within the CDU/CSU to play the “China card”. Wang reported this back home. He particularly praised Schroeder. Wang told his superiors that he, as an old-school diplomat and ex-foreign minister, was competent and, as chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee, bipartisan enough to avoid upsetting the incumbent government if China invited him.

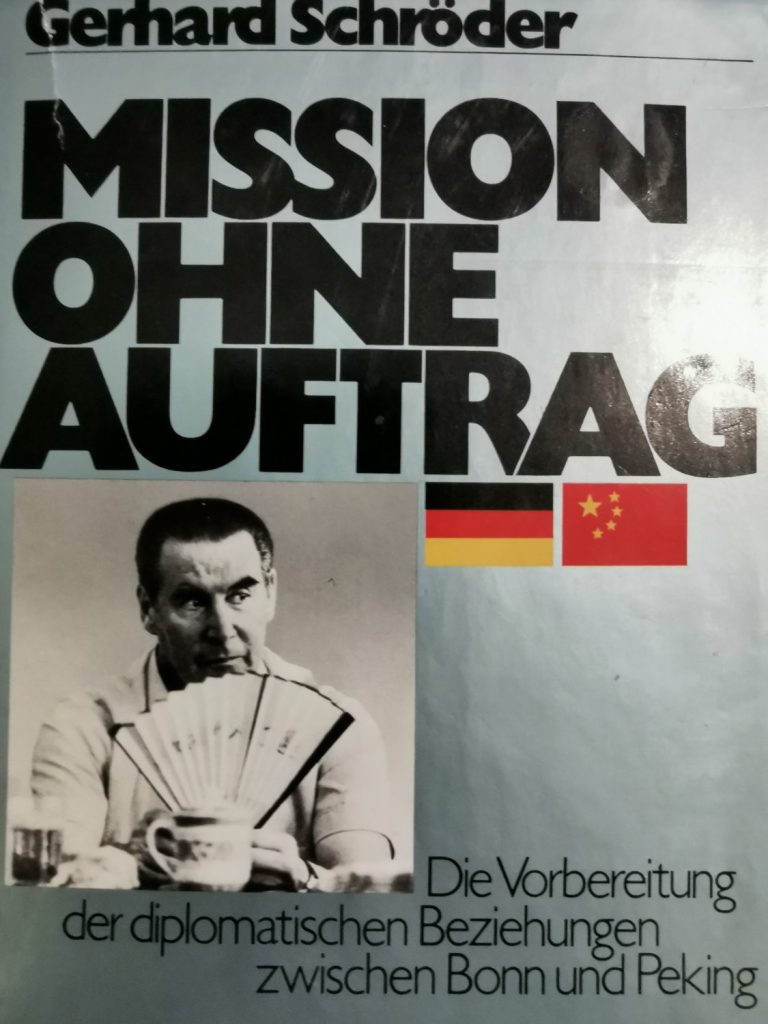

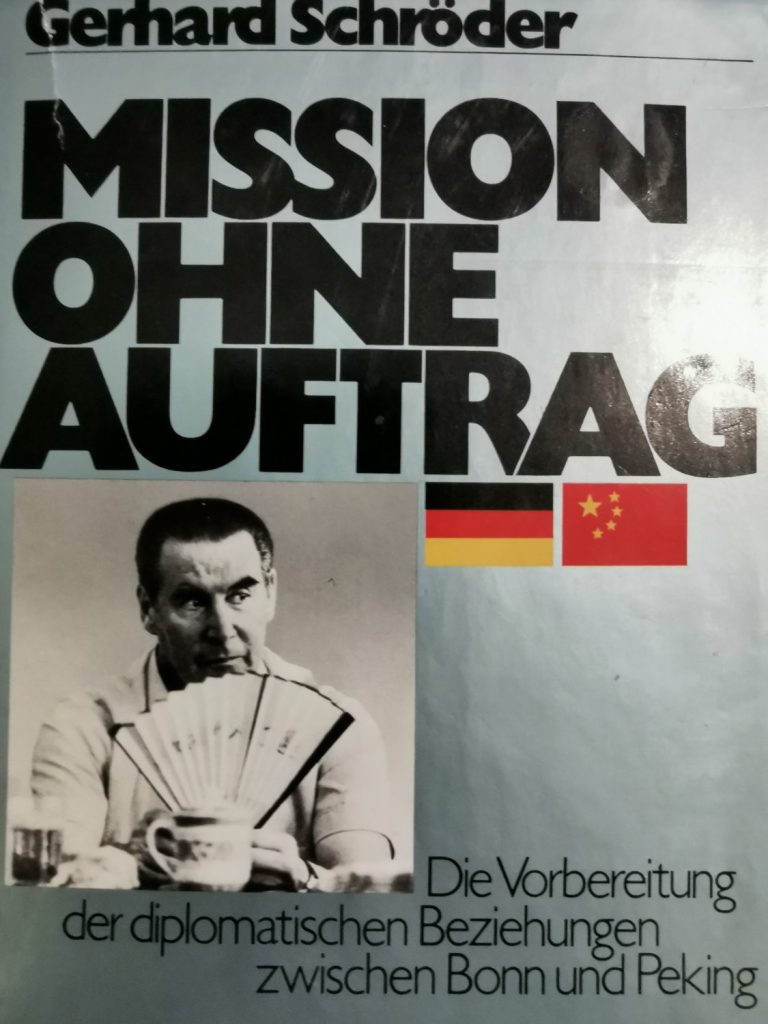

Wang established contact. He had no idea that Schroeder was also thinking about how to get an invitation. His wife Brigitte wrote in their memoirs, “Mission ohne Auftrag,” (Mission without task) published in 1988: “We will definitely go to China, my husband told me one day in January 1972.” No German politician had ever visited China before.

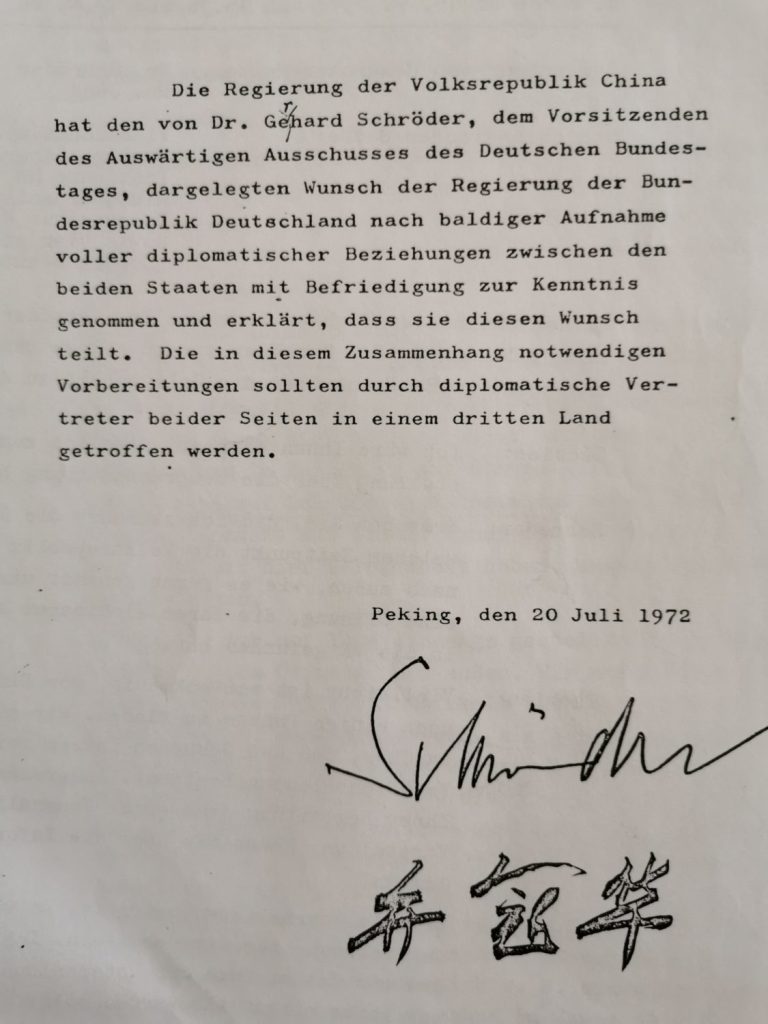

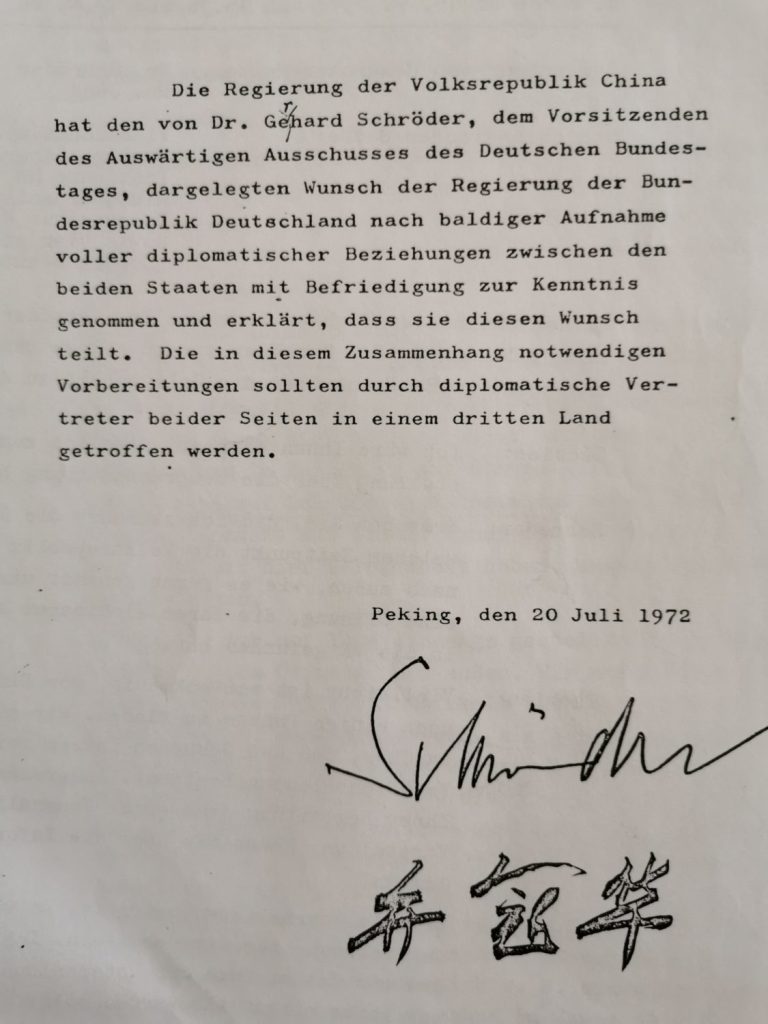

Five months later, on July 19, the couple sat face to face with Premier Zhou Enlai in Beijing. As Wang had hoped, Schroeder had informed Chancellor Brandt and Foreign Minister Scheel before the trip, and also obtained their approval for his confidential memorandum, which he intended to use as a blueprint for upcoming official negotiations. Zhou approved the draft. Schroeder and Vice Foreign Minister Qiao Guanhua signed it on July 20.

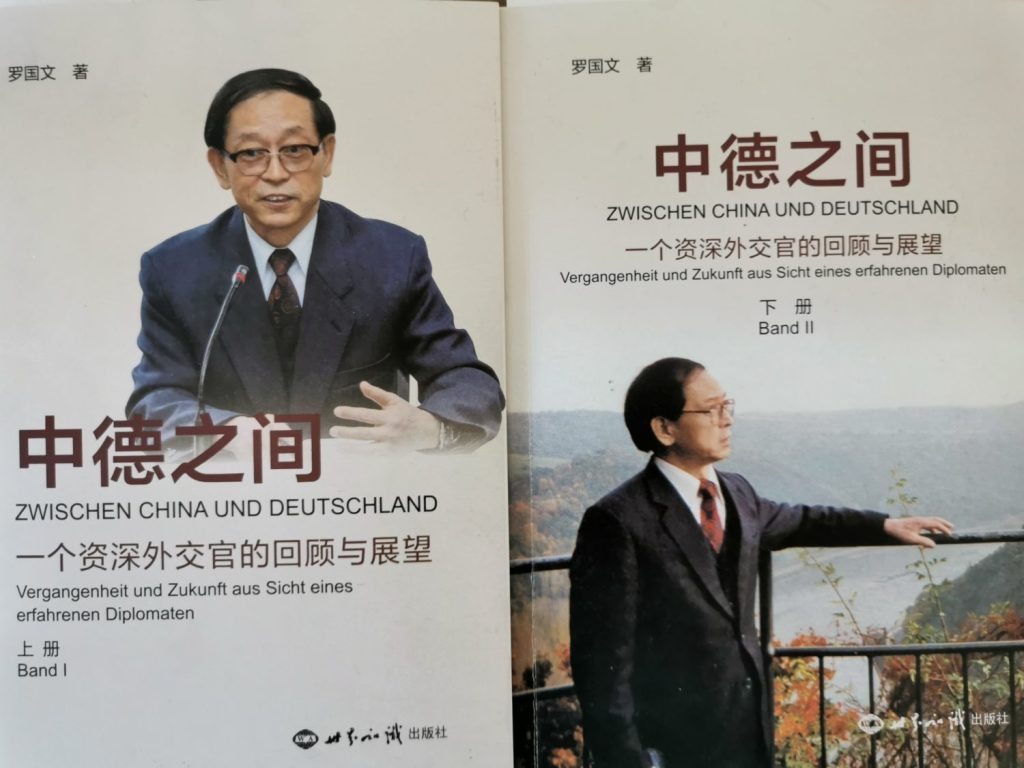

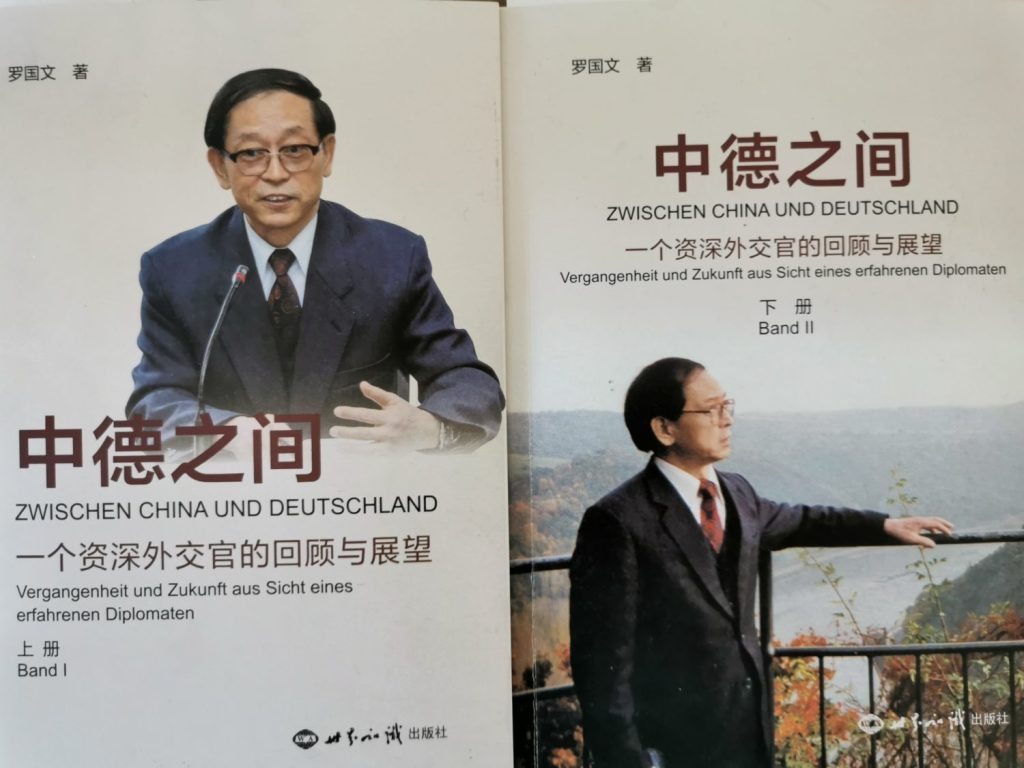

Thus began the countdown to the establishment of diplomatic ties, which led to the official treaty after 40 days and eight rounds of negotiations. On October 11, 1972, Foreign Minister Walter Scheel, who had traveled to Beijing, initialed it for the SPD-FDP coalition. Diplomat Luo Guowen 罗国文 calls the agreement “China’s Shortest Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations” (中德之间) in his new two-volume book, “Zwischen China und Deutschland” (Between China and Germany) (最短的建交公报).

It consists of only one sentence: “The Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany decided on October 11, 1972, to establish diplomatic relations and to exchange ambassadors within a short period of time.” The communiqué makes no mention of the “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence” nor the “One-China principle” regarding the Taiwan question. But neither was there a word on the Berlin issue. But Peking accepted Bonn’s claim to represent Berlin. It only agreed to a pragmatic solution. China had agreed to a text read aloud by the German side, according to which Bonn would represent West Berlin. Bonn was allowed to officially declare this exact statement.

Decades later, Scheel paid tribute to Wang Shu and Schroeder’s role as initiators: “Relations with China? We had to think about that very carefully. The fact that China chose Schroeder as an icebreaker was a good move: Before his trip, we had an extensive conversation with him. After his return, he visited me at my resort in Austria to talk about his impressions.”

Behind the haste and the simple procedure, there was – as we know today – also calculation, by Premier Zhou Enlai on behalf of Mao Zedong. After the admission of the People’s Republic to the UN in 1971 and after the spectacular visit of US President Nixon to Beijing in February 1972, the Chairman brooded over further liberalization to escape the Soviet menace. Mao’s motto was, “To the east, we open to Japan, to the west to Germany.” In September, Beijing and Tokyo established ties, and in October, it was Bonn’s turn.

Zhou urged Schroeder to do everything possible to ensure that Beijing could reach an agreement with Bonn on diplomatic relations before the federal election at the end of 1972. “For our countries, there is no question of normalization, but simply of establishing diplomatic relations.” He said this was different from the situation with Japan and did not touch on the Taiwan issue. For them, “it was crucial that Germany never had relations with Chiang Kai-shek. Adenauer is to thank for that.”

Today, the 70-page transcripts of Schroeder’s negotiations with Beijing are publicly available. They show how China’s diplomats persuaded him not to trust the Soviet Union: “We like to use a word for them that they are very angry about: the new czars,” Qiao said. They “don’t abide by any treaties.” Drastically, Zhou warned of Moscow’s “never-ending lust for expansion.” Beijing had “the impression that the current US administration understood this” China was prepared in case the Soviets moved against the East. But would Europe be if it went against the West? If “a false sense of security were to spread there in the wake of the ratification of the East treaties and the Berlin agreement, that would be very dangerous.” Zhou: “I’m telling you this because your party understands it, and don’t tell your government this because the SPD doesn’t understand it.”

How times change after 50 years. Today, Beijing under Xi Jinping’s leadership defends Putin’s war of aggression against Ukraine. While SPD Chancellor Olaf Scholz wrote in a guest article for the German daily FAZ on July 17: “Putin’s way of dealing with Ukraine and other countries in Eastern Europe bears neo-colonial features. Quite openly, he dreams of building a new empire based on the model of the Soviet Union or the Tsarist Empire.” And in his government declaration, he promises: Germany would have to align its “China policy with the China we find in reality”.

For journalist Wang Shu, who had worked as a correspondent in Asia and Africa for 20 years and only spoke a little English and French, everything was new when he was sent to Germany at the end of 1969. His advantage was that “I arrived without fixed opinions or ideological prejudices.” But that was also dangerous, under the suspicious eyes of his editors back home and in a poisoned domestic political atmosphere full of intrigue. When Wang told me this, his wife Yuan Jie interrupted us, “I was scared to death at the time”.

Unbeknownst to Wang, however, he had a powerful protector in Mao. He even scribbled on one of Wang’s reports, “He’s suitable as ambassador,” which Wang indeed became in Bonn in 1974. After the bloody border skirmish with the Soviet Union in 1969, the Chairman was contemplating the changed global situation, which had forced China to open up to the West. Wang’s reports came just in time then.

China knew more about the Germans than vice versa. In 1972, the Germans arrived in a country badly scarred by the Cultural Revolution. An unintentionally comical gaffe ensued. For his farewell banquet in October in the Great Hall of the People, Foreign Minister Scheel had flown in delicacies from Germany. The proud chef greeted all guests and wanted to know how they enjoyed the food, diplomat Luo recalls. However, with his white chef’s hat, he startled the Chinese guests, including high-ranking officials. It reminded them of the “high hats” the Red Guards once forced onto them. Luo uses a German word to describe the feeling in the Hall of the People at the time. He puts it in parentheses (shock).

It did not harm the ever rapidly developing ties.

Can Karagoez has been Short Term Specialist H6 at Daimler Truck China since June. Karagoez has worked in the company’s truck division for 12 years.

Vincent Teckseng Lim will be the new General Manager of China Airlines Vienna. Lim has been with China Airlines since the Vienna office opened in 2005. Since 2017, he served there as airport manager at Vienna-Schwechat Airport.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Rice with fish – a good combination. Not only on the plate: In Qingtian, Zhejiang Province, a farmer releases a fish into the flooded rice field. There, it can grow and eat pests along the way, while the rice plants provide it with cooling shade. And the land is used twice. In China, such co-cultures have existed for about 1,300 years. The method is apparently also good for the climate: Up to 17 percent of the world’s methane emissions are produced by rice cultivation. Fish could reduce these emissions by eating plankton that grows in the fields.

It’s a shame that dreams sometimes have to be so complicated! Xi Jinping’s vision of “common prosperity” is a noble goal, but unfortunately, the less-than-rosy reality stands in the way: Bank protests, meager growth figures, enraged real estate buyers, disappointed graduates slipping from college straight into record unemployment. The problems are piling up, as our author Fabian Kretschmer analyzes from Beijing. And all this just a few months before the Party Congress that is to usher in Xi Jinping’s third term in office.

And the gas issue is not exactly a dream either. China actually sits on huge shale gas deposits. These could help supply the country with power and offer an alternative to coal, which China’s energy supply still heavily depends on. But fracking is not only harmful to the environment, but it is also extremely difficult in China. Geographical conditions make it complicated, expensive, and could even cause earthquakes. In Sichuan, earthquakes damaged some 20,000 homes in 2019, killing two people and prompting protests. Still, China continues to rely on fracking. Nico Beckert analyzes its prospects.

Johnny Erling introduces you today to the heralds of diplomatic relations between the Federal Republic of Germany and China. A Chinese journalist and an opposition politician from the CDU initiated diplomatic contact 50 years ago: Gerhard Schroeder and Wang Shu. In the fall of 1972, Beijing and Bonn sealed their intentions in a communiqué with just one sentence. Something diplomats can only dream of today.

What has happened to several thousand small savers in China’s central province of Henan may have shaken their worldview to the core. For months, they have been unable to access their bank accounts after four regional banks froze them in the wake of an alleged speculation scandal (China.Table reported).

The banking scandal in Henan may only involve a relatively small sum in economic terms. Nevertheless, it has stirred up a primal fear among the population. Since the beginning of the country’s economic opening, society has been held together by a silent agreement: The Chinese willingly surrender their claim to a political say as long as the party leadership in Beijing ensures a steady rise of material living standards. And for decades, the plan worked perfectly: Between 1978, the beginning of Deng Xiaoping’s reform policy, and Xi Jinping’s inauguration in 2013, China’s gross domestic product increased more than 64-fold.

But the tide has turned completely in the wake of the dogmatic “zero-Covid” policy at the latest. Economic growth has virtually ground to a halt: Between April and June, the gross domestic product grew by only 0.4 percent year-on-year. Compared to the first quarter of the year, the world’s second-largest economy actually shrank by 2.6 percent. The immediate effects of the impending recession are beginning to show more and more clearly. In the overheated real estate sector, a central pillar of the domestic economy, a downward spiral is already impending: Currently, tens of thousands of Chinese are threatening to stop making their mortgage payments because their apartment buildings are sitting around unfinished. (China.Table reported).

At the same time, youth unemployment in China’s cities is at a record high: Almost one in five Chinese between the ages of 16 and 24 currently has no income. This year alone, with almost eleven million university graduates, more young people are entering the job market than ever before. Despite having good qualifications, many of them will have to settle for precarious odd jobs. According to a forecast by the US bank Merrill Lynch, youth unemployment could rise to as much as 23 percent this year. The economic predicament is to a large extent homemade. Beijing’s excessive regulatory wave against the tech industry, which after all has produced the country’s most internationally successful corporations, led to unprecedented mass layoffs last year.

Without doubt, Xi Jinping is facing the greatest challenge in his political career to date, shortly before the end of his second term in office. After all, the 69-year-old took office with the vision of making Chinese society fairer and more just. “Common prosperity” is the propagated paradigm shift touted by Xi in virtually every one of his speeches. The concept is also a reaction to the gold-rush mentality of the 2000s, when China’s gross domestic product grew by double-digit percentages, but at the same time corruption, excessive wealth and radical inequality surged.

But so far, Xi Jinping’s vision of “common prosperity” is nothing more than a vague expression. The measures announced by China’s head of state so far seem more populist than sustainable: Companies have been ordered to return more excess profits to the general public in the form of philanthropic donations, and banks are to curb the “excessive” salaries of their executive boards (China.Table reported).

Just how far the People’s Republic is from “common prosperity” was recently revealed by the latest data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China. More than 960 million of 1.4 billion Chinese live on a monthly income of less than ¥2,000, which is less than €290. The weak income share of the population of the gross domestic product also reveals the economic Achilles heel of the Chinese economy: The weakening domestic consumption.

This results in a correspondingly high risk that China could get caught in the so-called “middle income trap,” from which only a handful of former developing countries – first and foremost South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore – have managed to escape. The rapid growth of the People’s Republic of China was based not least on a cheap labor force, coupled with a government that massively invested its rich financial savings in infrastructure, technology and production capacities.

But this economic model will soon reach its limits: In order to achieve sustainable growth, the country would have to readjust its income distribution and thus boost domestic consumption. However, the necessary reforms would trigger a painful transition process, which the government, concerned about social stability, is probably right to fear.

But the window of opportunity for China is slowly closing: Demographic change is advancing rapidly, while the birth rate is at a record low. As a result, the flattening of annual growth rates is currently setting in far too early: After all, despite the remarkable rise of the People’s Republic of China, it has only reached one-third of the GDP per capita levels in South Korea and one-eighth of Switzerland’s. Fabian Kretschmer

Germany’s Minister of Finance, Christian Lindner, recently spoke out in favor of fracking in northern Germany. In some cases, he said, fracking is “reasonable”. The extraction of gas deposits in the North Sea is also “sensible and feasible,” Lindner told German media.

Fracking technology has brought the USA a gas boom. The country is now a net gas exporter. In Germany, the decision to lift the ban on this controversial extraction method has been under discussion for several weeks. The looming gas crisis following the Russian war in Ukraine has made the issue relevant once again. In China, fracking has been used for many years. Shale gas is expected to contribute to the country’s energy supply and reduce its dependence on coal. This would also benefit the country’s climate goals; after all, coal still dominates the electricity mix.

According to some estimates, China possesses the world’s largest shale gas reserves. In 2013, the US Department of Energy estimated that Chinese reserves were almost twice as large as those of the USA. A year earlier, authorities issued an ambitious target: Annual production was to rise to between 60 and 100 billion cubic meters by 2020. But the targets were missed by a wide margin. In 2020, only 20 billion cubic meters were extracted. Even the revised target of 30 billion was not achieved. Local protests are only one reason for this.

Sichuan has experienced earthquakes as a result of the fracking boom. The province has the largest exploitable deposits. Several incidents occurred in 2019. Thousands of residents in the region protested in front of the Rong district government building at the time. They blamed the fracking industry for the earthquakes. The quakes killed two people and injured 13. 20,000 buildings were damaged and nine collapsed entirely, the New York Times reported. Following the protests, fracking was suspended in the district. But authorities deny a link between the controversial gas extraction and the earthquakes.

More problems could also arise with water in the future. Fracking, which involves injecting a mixture of water, sand and chemicals into the rock under high pressure, requires a lot of water. Meanwhile, there is a shortage of water in some regions of Sichuan. In addition, the province is densely populated. The fracking industry can hardly avoid the local population. Conflicts are inevitable.

China has the largest treasure trove of shale gas – but has a hard time reaching it. The reserves lie at greater depths than in the USA. In the largest gas region in Sichuan, gas companies have to drill to depths of over 4,500 meters – about twice as deep as in the USA. This also increases production costs. According to consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, a deep shale well costs $9 million, two million more than a medium-depth drill. In addition, China’s deposits are not as concentrated as those in the US, and Sichuan is very mountainous. But fracking towers have to be placed on even ground, and pipelines are also difficult to build in the mountains.

All these challenges are driving up costs. According to PetroChina, shale gas fracking costs 20 to 30 percent more than extracting conventional resources. “Highly complex above and below-ground challenges mean that the Chinese shale gas journey will continue to look very different from that in the US,” says Zhang Xianhui of consulting firm Wood Mackenzie.

International oil and gas companies such as BP, ExxonMobil, Shell, ConocoPhillips and Eni have withdrawn from fracking shale gas in China over the years. In 2009, they entered the market with high hopes for a fracking boom. But reality quickly caught up with the companies. Fracking was simply not profitable. After the withdrawal of the international corporations, PetroChina and Sinopec have to bear the costs of the fracking infrastructure alone.

The only international cooperation still exists for so-called tight gas in the Ordos Plateau in northwestern China, which has to be fracked from dense rock strata. But here, too, are problems: Yields from individual wells are quite low, so thousands of holes need to be drilled and connected to pipelines and other infrastructure. That drives up costs.

Despite high hopes from authorities, the fracking boom in the People’s Republic has so far failed to materialize. In recent years, production has been increased to 23 billion cubic meters (2021). Various analysts estimate that China could reach production of 50 to 60 billion cubic meters in 2035. But some experts believe that this would already be the maximum.

Today, China already consumes 372 billion cubic meters of gas, Wood Mackenzie experts told China.Table. They assume that production could continue to rise after 2035. But fracking will continue to contribute only a small share of gas supply. Chinese production pales in comparison to the annual production of shale gas in the United States with approximately 700 billion cubic meters. However, every cubic meter of gas produced in China reduces dependence on foreign countries and contributes to the goal of energy security. But the problems for local residents affected by earthquakes remain. Cooperation Renxiu Zhao

The US intelligence agency CIA considers the likelihood of a violent incursion by Chinese forces into Taiwan to be high. It is not a question of “whether” Chinese leaders might decide to “use force to control Taiwan” in a few years, but rather “how and when they will do it,” CIA chief William Burns said on Wednesday at the Aspen Security Forum. “The risks of that become higher, it seems to us, the further into this decade that you get.”

The leadership in Beijing has learned its lessons from Russia’s “strategic failure” in Ukraine, Burns added. “You don’t achieve quick, decisive victories with underwhelming force.” In addition, China has learned that it must extensively safeguard its economy against sanctions. Burns, however, does not believe that Beijing is currently providing military assistance to Russia.

Chinese Ambassador to the United States Qin Gang told the forum in the Rocky Mountains that Beijing still seeks “peaceful reunification.” At the same time, he accused the United States of supporting “independence forces” in Taiwan. The US is “hollowing out and blurring” its commitment to Beijing’s “One-China” policy. “Only by adhering strictly to the one-China policy, only by joining hands to constrain and oppose Taiwan independence, can we have a peaceful reunification,” Qin said. fpe

HSBC Qianhai Securities has apparently become the first foreign lender in China to appoint a Party committee. This was reported by the Financial Times, citing two sources familiar with the decision. According to the report, the bank did not initially comment on the matter. However, informed individuals reportedly said that the committee has been set up in early July and does not have a management role.

HSBC Qianhai is the investment banking arm of HSBC in China. HSBC is headquartered in London, with a large part of its profits generated in Hong Kong. The financial institution plans to expand rapidly in mainland China as well. In April, it increased its stake in the Qianhai Securities joint venture from 51 to 90 percent.

HSBC’s decision could have an impact on other foreign banks in China. There is no word yet on Party committees at the other six foreign investment banks operating in China. Goldman Sachs, however, has already hired several Party members for senior positions, including the former head of its China unit, Fred Hu. And Swiss bank UBS also brought Fan Yang onto its team in 2020 as Head of Global Banking for Asia. She is the daughter of former Chinese Vice Premier Liu Yandong.

By law, companies in China are required to employ a Party cell of at least three employees who are members of the Communist Party. This also applies to foreign joint ventures. Among foreign financial institutions, however, the requirement has not yet been enforced. Party committees have a social function in companies, but can also serve the purpose of influencing strategic decisions. jul

Military engineers from Beijing have developed a smaller, less expensive version of Russia’s “Poseidon” underwater drone. Like its Russian counterpart, the weapon is powered by a disposable nuclear reactor, reports the South China Morning Post. It is designed to provide the torpedo with a range of 10,000 kilometers. That is roughly equivalent to the range of an intercontinental ballistic missile. AI technologies such as machine learning are expected to allow the weapon to attack targets underwater with little or no human involvement.

According to lead researcher Guo Jian of China’s Institute of Atomic Energy, there is a growing demand for small, high-speed, long-range unmanned underwater vehicles that can be used for reconnaissance, detection, attack and strategic strikes. The smaller size means the smart torpedo drone can be launched from almost any submarine or warship. Its low cost makes it suitable for mass production, unlike its Russian counterpart, and it could be deployed in veritable swarms, according to Ma Liang of the Navy Submarine Academy in Qingdao.

For their design, the project team removed expensive shielding materials. Only the critical components would still be protected from radiation. The engineers also replaced expensive rare-earth coatings inside the reactor core with inexpensive materials such as graphite. To further cut costs, the scientists also propose using commercially available tech components instead of military-grade products. fpe

China’s semiconductor manufacturer SMIC has made substantial progress in domestic semiconductor production despite US sanctions, according to an industry report. Reportedly, SMIC has been shipping its first 7 nm chips since last year. Although these are primarily used for niche products, they show that the People’s Republic semiconductor production is already more advanced than expected, analysts at TechInsights explained. “Despite not having access to the most advanced equipment technologies as a result of sanctions currently in place, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) appears to have used 7 nm technology to manufacture the MinerVa Bitcoin Miner system on chip (SoC),” the tech analysts wrote.

Since the end of 2020, the US has prohibited the unlicensed sale of equipment that can be used to manufacture semiconductors with 10 nm and above to the Chinese company. What is also interesting is that according to the analysts, the technology discovered from SMIC is probably a fairly close copy of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s (TSMC) N7 process. TSMC and SMIC were already in a clash some time ago over allegedly stolen technologies by the Chinese company.

SMIC’s surprising progress raises questions about the effectiveness of the US export control mechanism and whether Washington can actually thwart China’s ambitions to develop a domestic world-class chip industry. ari

Exactly 50 years ago, in the penultimate week of July 1972, Bonn and Beijing began to establish diplomatic relations. But not in a very straightforward way. And that was no accident. One of the people behind it was an opposition politician from the CDU and, on the Chinese side, a Xinhua journalist in Bonn. The unusual actors jumped over their shadows and, just eleven weeks later, the Federal Republic and the People’s Republic sealed their new relationship with an official document. It is also called the shortest communiqué in China’s diplomatic history.

Wang Shu (王殊) head of the news agency Xinhua (New China) office in Bonn, showed no sign of his nervousness. His meeting with CDU politician Gerhard Schroeder – not to be confused with his namesake from Lower Saxony and later German chancellor – had already lasted more than three hours. But the one phrase he was waiting for did not pass his interlocutor’s lips.

It was February 21, 1972, and an SPD-FDP coalition was governing the Federal Republic. Opposition man Schröder, who had once served as Foreign and Minister of Defense for the CDU/CSU, was presiding over the Bundestag’s Foreign Affairs Committee. “We talked about the global situation,” Wang recalled. “But all I could think was, ‘When is he going to ask me?’ It was already getting dark outside.” Eventually, he dropped all politeness. “I interrupted Schröder. Would he be interested in visiting China in the near future?” His counterpart immediately responded, “Very much so, and if possible during this summer break.”

When Wang told me the anecdote 25 years later in 1997, he shook with laughter and still pretended to be indignant: “Was that a waste of time! And only because Schroeder was too posh to ask first.”

Wang’s task was to find out whether an invitation to Schroeder would bring China closer to its goal of establishing diplomatic relations with Germany. Actually, Schroeder was not the right man since belonged to the opposition. The SPD-FDP coalition led by Willy Brandt, however, kept a low profile regarding contacts with China in order not to burden its “New Eastern Policy” of reconciliation with Moscow and East Berlin.

Beijing’s policy of fiercely attacking Moscow and playing rapprochement ping-pong with the United States sparked fantasies within the CDU/CSU to play the “China card”. Wang reported this back home. He particularly praised Schroeder. Wang told his superiors that he, as an old-school diplomat and ex-foreign minister, was competent and, as chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee, bipartisan enough to avoid upsetting the incumbent government if China invited him.

Wang established contact. He had no idea that Schroeder was also thinking about how to get an invitation. His wife Brigitte wrote in their memoirs, “Mission ohne Auftrag,” (Mission without task) published in 1988: “We will definitely go to China, my husband told me one day in January 1972.” No German politician had ever visited China before.

Five months later, on July 19, the couple sat face to face with Premier Zhou Enlai in Beijing. As Wang had hoped, Schroeder had informed Chancellor Brandt and Foreign Minister Scheel before the trip, and also obtained their approval for his confidential memorandum, which he intended to use as a blueprint for upcoming official negotiations. Zhou approved the draft. Schroeder and Vice Foreign Minister Qiao Guanhua signed it on July 20.

Thus began the countdown to the establishment of diplomatic ties, which led to the official treaty after 40 days and eight rounds of negotiations. On October 11, 1972, Foreign Minister Walter Scheel, who had traveled to Beijing, initialed it for the SPD-FDP coalition. Diplomat Luo Guowen 罗国文 calls the agreement “China’s Shortest Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations” (中德之间) in his new two-volume book, “Zwischen China und Deutschland” (Between China and Germany) (最短的建交公报).

It consists of only one sentence: “The Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany decided on October 11, 1972, to establish diplomatic relations and to exchange ambassadors within a short period of time.” The communiqué makes no mention of the “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence” nor the “One-China principle” regarding the Taiwan question. But neither was there a word on the Berlin issue. But Peking accepted Bonn’s claim to represent Berlin. It only agreed to a pragmatic solution. China had agreed to a text read aloud by the German side, according to which Bonn would represent West Berlin. Bonn was allowed to officially declare this exact statement.

Decades later, Scheel paid tribute to Wang Shu and Schroeder’s role as initiators: “Relations with China? We had to think about that very carefully. The fact that China chose Schroeder as an icebreaker was a good move: Before his trip, we had an extensive conversation with him. After his return, he visited me at my resort in Austria to talk about his impressions.”

Behind the haste and the simple procedure, there was – as we know today – also calculation, by Premier Zhou Enlai on behalf of Mao Zedong. After the admission of the People’s Republic to the UN in 1971 and after the spectacular visit of US President Nixon to Beijing in February 1972, the Chairman brooded over further liberalization to escape the Soviet menace. Mao’s motto was, “To the east, we open to Japan, to the west to Germany.” In September, Beijing and Tokyo established ties, and in October, it was Bonn’s turn.

Zhou urged Schroeder to do everything possible to ensure that Beijing could reach an agreement with Bonn on diplomatic relations before the federal election at the end of 1972. “For our countries, there is no question of normalization, but simply of establishing diplomatic relations.” He said this was different from the situation with Japan and did not touch on the Taiwan issue. For them, “it was crucial that Germany never had relations with Chiang Kai-shek. Adenauer is to thank for that.”

Today, the 70-page transcripts of Schroeder’s negotiations with Beijing are publicly available. They show how China’s diplomats persuaded him not to trust the Soviet Union: “We like to use a word for them that they are very angry about: the new czars,” Qiao said. They “don’t abide by any treaties.” Drastically, Zhou warned of Moscow’s “never-ending lust for expansion.” Beijing had “the impression that the current US administration understood this” China was prepared in case the Soviets moved against the East. But would Europe be if it went against the West? If “a false sense of security were to spread there in the wake of the ratification of the East treaties and the Berlin agreement, that would be very dangerous.” Zhou: “I’m telling you this because your party understands it, and don’t tell your government this because the SPD doesn’t understand it.”

How times change after 50 years. Today, Beijing under Xi Jinping’s leadership defends Putin’s war of aggression against Ukraine. While SPD Chancellor Olaf Scholz wrote in a guest article for the German daily FAZ on July 17: “Putin’s way of dealing with Ukraine and other countries in Eastern Europe bears neo-colonial features. Quite openly, he dreams of building a new empire based on the model of the Soviet Union or the Tsarist Empire.” And in his government declaration, he promises: Germany would have to align its “China policy with the China we find in reality”.

For journalist Wang Shu, who had worked as a correspondent in Asia and Africa for 20 years and only spoke a little English and French, everything was new when he was sent to Germany at the end of 1969. His advantage was that “I arrived without fixed opinions or ideological prejudices.” But that was also dangerous, under the suspicious eyes of his editors back home and in a poisoned domestic political atmosphere full of intrigue. When Wang told me this, his wife Yuan Jie interrupted us, “I was scared to death at the time”.

Unbeknownst to Wang, however, he had a powerful protector in Mao. He even scribbled on one of Wang’s reports, “He’s suitable as ambassador,” which Wang indeed became in Bonn in 1974. After the bloody border skirmish with the Soviet Union in 1969, the Chairman was contemplating the changed global situation, which had forced China to open up to the West. Wang’s reports came just in time then.

China knew more about the Germans than vice versa. In 1972, the Germans arrived in a country badly scarred by the Cultural Revolution. An unintentionally comical gaffe ensued. For his farewell banquet in October in the Great Hall of the People, Foreign Minister Scheel had flown in delicacies from Germany. The proud chef greeted all guests and wanted to know how they enjoyed the food, diplomat Luo recalls. However, with his white chef’s hat, he startled the Chinese guests, including high-ranking officials. It reminded them of the “high hats” the Red Guards once forced onto them. Luo uses a German word to describe the feeling in the Hall of the People at the time. He puts it in parentheses (shock).

It did not harm the ever rapidly developing ties.

Can Karagoez has been Short Term Specialist H6 at Daimler Truck China since June. Karagoez has worked in the company’s truck division for 12 years.

Vincent Teckseng Lim will be the new General Manager of China Airlines Vienna. Lim has been with China Airlines since the Vienna office opened in 2005. Since 2017, he served there as airport manager at Vienna-Schwechat Airport.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

Rice with fish – a good combination. Not only on the plate: In Qingtian, Zhejiang Province, a farmer releases a fish into the flooded rice field. There, it can grow and eat pests along the way, while the rice plants provide it with cooling shade. And the land is used twice. In China, such co-cultures have existed for about 1,300 years. The method is apparently also good for the climate: Up to 17 percent of the world’s methane emissions are produced by rice cultivation. Fish could reduce these emissions by eating plankton that grows in the fields.