At the beginning of the new Silk Road was a speech by President Xi Jinping in Kazakhstan. At the time, no one would have guessed that his idea of connecting Central Asia would one day lead to an infrastructure project worth billions. Today, the new Silk Road (also known as the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI for short) has almost 150 member countries, where China is making varying levels of investment. The G7 countries have not joined the initiative. The only exception is Italy, which is currently considering leaving it.

Currently, the biggest BRI partners are not in Central Asia, but on the Arabian Peninsula. China has signed many significant contracts with them in recent months, explains Finn Mayer-Kuckuk in collaboration with Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI). One reason is the Gulf states’ interest in technologies related to the energy transition. And China is strong in this area. In the meantime, China is cooperating with Central Asia in transport infrastructure, as once planned, to revive old trade routes.

Xi explained his fascination with the ancient Silk Road at the time of his speech in 2013 by claiming to have heard the call of the camels from the desert. At first, no one took all his plans seriously, as Frank Sieren analyzes. Not even the state media got on board with the idea. It first had to get on the agenda of a party meeting for the CP grandees to realize that the project is important to Xi. By now, China has now more than achieved its goal of doubling trade with Silk Road partners.

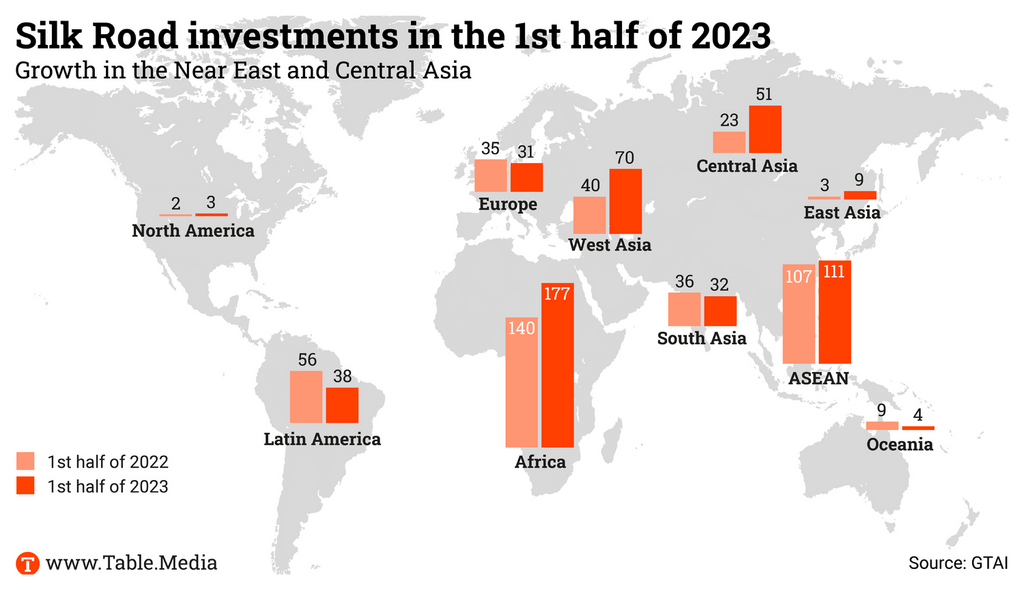

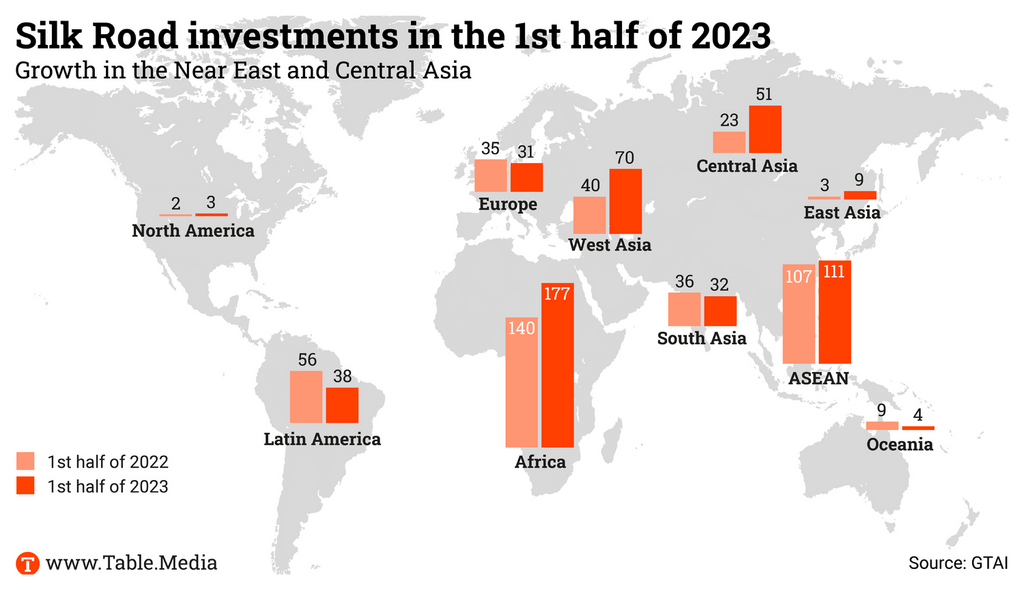

China’s activities along the new Silk Road (“Belt and Road” Initiative, BRI) have concentrated on the Middle East and Central Asia in the first half of the year. This is shown by the ongoing evaluation of Belt and Road investments by Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI). GTAI is the German government’s agency for foreign trade and location marketing.

The most important Silk Road partners are currently located on the Arabian Peninsula. The largest number of contracts have been signed with players in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. This fits in with the trend of increasing Chinese involvement in the Middle East. The trade relations are certainly reciprocal: Saudi Arabia is also heavily engaged in China. The country has also been involved in the BRICS Group since the end of August.

The background: Even the oil countries see the era of fossil energy sources ending. For this reason, they are interested in cooperating in the field of new industries related to the energy transition:

A total of 41 contracts were concluded with Arab partners. In the entire Middle East, the number of contracts concluded has increased from 40 to 70 since last year.

According to the GTAI, the Central Asia Summit in Xi’an in May also boosted BRI cooperation. As expected, the focus here continues to be on transport infrastructure. Most contracts in this area have been signed with partners from Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The current flagship project is a rail link from Kashgar in Xinjiang via Osh in Kyrgyzstan to Tashkent in Uzbekistan. The line had been planned since the 1990s and is now finally coming to fruition.

Construction of such large-scale projects is not only driven by the release of BRI funds by China and the development banks. Russia had long opposed the expansion of Chinese influence in the ex-Soviet republics. Since the beginning of the war, however, Moscow has been accommodating Beijing on many issues. This also made the Central Asia railway from Kashgar to Tashkent possible, a project Russia had long resisted.

While China’s construction companies once took on a decent share of these projects themselves, their business is now shrinking, as GTAI figures show. Despite the Silk Road activities, China’s construction companies have never managed to outpace their European competitors.

This year’s overall picture shows a shift in Silk Road activity away from South America and Europe towards the Middle East and Central Asia. A striking exception is a joint investment with Russia in Bolivia. There, battery specialist CATL is securing access to lithium. The Russian energy company Rosatom has been a co-investor here since this year.

It is 7 September 2013 at around half past ten in the morning. The hall is packed with students, politicians and journalists. “Nazarbayev University” is written in gold letters above the stage. Below it sits the person who gave the university its name, Nursultan Nazarbayev, President of Kazakhstan at the time. The lecture hall looks like a small, venerable parliament. Dark wood, dark walls. The heavy desks for the audience, arranged in a semicircle, ascend row by row towards the back of the room.

The university is located in Astana, the new capital of the largest Central Asian country, a city “younger than Google,” as Nazarbayev liked to emphasize. It celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2022. Before that, Kazakhstan’s largest city Almaty (Alma-Ata) had been the capital.

Standing at the podium that morning is Chinese President Xi Jinping dressed in a dark suit. He has only been in office for half a year at the time. “Shaanxi, my home province, is right at the starting point of the ancient Silk Road,” Xi says. “As I stand here and look back at that episode of history, I could almost hear the camel bells echoing in the mountains and see the wisp of smoke rising from the desert.” Kazakhstan played an important role in exchanges between East and West more than 2,100 years ago. “A near neighbor is better than a distant relative,” Xi flattered the Kazakhs.

For good reason: The country, with its population of 18 million, is geographically one of the ten largest countries in the world – and one of the 15 countries with the highest amount of mineral resources. And it shares a 1,900-kilometer border with China. Only the border with Russia is longer.

The Eurasian region must now reinvent itself and jointly build “an economy belt along the Silk Road,” Xi explains his plan. The speech in Astana is considered the starting signal for the New Silk Road. The day before, Xi just arrived from St. Petersburg, where he attended his first G20 summit as president. He did not mention a word about his plans for the Eurasian continent there.

Xi’s plan at the time was to more than double China’s trade volume with partner countries on the New Silk Road in about ten years. It even turned out to be an additional 110 percent. In the first half of 2023, trade is already at 964 billion US dollars. Despite the economic crisis, this represents a growth of 9.6 percent compared to the previous year, while trade with Europe has slumped by 4.9 percent and trade with the USA by over 14 percent.

Xi had already shown his geopolitical intentions by the order of his first foreign trips as Chinese president. His first trip was to Russia. Then Xi continued to tour the countries of Africa, with the 5th BRICS Summit in South Africa at the end. His second big trip was to Central Asia, then to the aforementioned G20 summit in St. Petersburg, then to Kazakhstan for the Silk Road speech – and finally to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Kyrgyzstan’s capital, Bishkek. Only then followed Europe (March 2014) and the USA (2015).

It was a clear signal that Xi does not want to follow behind the large established Western states, but wants to band together with the small emerging countries and collectively rebuild the global order as the majority of the world: “Let us join hands to carry on our traditional friendship and build a bright future together,” Xi then also beckoned in Astana.

In the beginning, Xi has a problem: His speech finds practically no global resonance. Even the party papers in China tend to compulsorily comment (“important speech”) on their party leader’s plan. At first, journalists and commentators seem to think the plan for a “joint economic belt” is a friendly gesture toward the Kazakhs.

Not much happens in the weeks after the speech. Most quickly forgot about the topic, although Xi gave another similar speech in front of the parliament in Jakarta a month later, in which he spoke of a maritime Silk Road.

But in the fall of 2013, the term “New Silk Road Economic Belt” appears in the document of the annual meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. It is the first under the leadership of the new state and party leader. Now it dawns on everyone: The project is important after all.

But it only gradually turns out that Xi Jinping is actually planning to build a series of economic belts from China to the West. Skepticism is high in China. Xi, however, is pushing the project with all propaganda force. Special pages appear in Chinese newspapers, one event after the next is organized. Funds are set up. The cities in western China have to get involved in constructing the New Silk Road.

In March 2014, Xi then travels to the German city of Duisburg, Europe’s largest inland port, as part of his first trip to the EU. Xi is there to welcome one of the first trains that would regularly travel from the Chinese metropolis of Chongqing and other cities to Duisburg. Today, up to 60 trains a week run between Duisburg and various Chinese destinations. However, the train runs are still subsidized by the Chinese government. A train can only carry a maximum of 60 containers per trip, while a single ship can carry up to 10,000 containers.

The BRI will not be China’s solo but an inspiring chorus, Xi emphasized in his speech in Astana. He said the countries along the New Silk Road must become more independent, secure and stable. These countries also realize: China does not give handouts. Nevertheless, after assessing the opportunities and risks, many believe that the opportunities ultimately outweigh the risks. By now, 149 countries are members of the Belt and Road Initiative. The UN has 193 member states.

The only country that is currently thinking about leaving is Italy. It is the only major Western developed nation, and the only G7 country in the BRI club. That is bitter for Beijing. Overall, however, Xi is much further ahead than initially planned. After all, the official title of his 2013 speech was: Xi wants to build a “Silk Road Economic Belt” with the “Central Asian countries.”

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

German Research Minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger also sees science as having a responsibility in collaborating and competing with China: The research community must ask itself what the “red lines” are for projects and how they can be drawn and maintained, she said on Tuesday evening at an event hosted by the German China think tank Merics on the subject of innovation. The liberal FDP politician also called for more self-confidence vis-à-vis China, including from the perspective of the political system. “We have something to offer,” Stark-Watzinger stressed. “Freedom is our greatest competitive advantage, which is why we must defend it.”

According to Stark-Watzinger, however, decision-making processes must still be accelerated in order to make innovations competitive. “Innovation policy is the best industrial policy we have,” said the minister. She also called for more sovereignty in key technologies. This was not a “luxury option” or “nice to have” but fundamental. Nevertheless, Stark-Watzinger spoke out against a decoupling from China. When it comes to innovation, de-risking is necessary, not decoupling or deglobalization. On the contrary: “It is more important than ever that we look for partners who share our values.”

Jakob Edler, Executive Director of the Fraunhofer Institute, also warned against simply severing all ties with China. Edler stressed that China is on its way to becoming a very strong science player. “China has autonomy on the one hand and is a strong international scientific player on the other. We have to take note of that.”

In a recent guest article in the German daily FAZ, Stark-Watzinger cautioned that Germany should not be naïve in its dealings with a regime that “proclaims the goal of transferring the results of civilian research into military applications and of achieving dominance in critical technologies.” ari

Huawei is now regularly supplied with a powerful chip in modern 7-nanometer technology by the Chinese semiconductor manufacturer SMIC. The recently unveiled Mate 60 Pro smartphone model uses a Kirin 9000 series processor, which proves China’s technical capabilities. In response to US sanctions in the semiconductor sector, China is currently gradually acquiring the necessary skills to manufacture high-performance chips itself. The new mobile phone will be launched later this month. Experts had disassembled the new model and identified the chip.

The Kirin 9000 is manufactured by the semiconductor specialist HiSilicon, owned by the Huawei Group. HiSilicon does not own any factories itself, but awards manufacturing contracts. Before the sanctions, it commissioned a lot of production from the Taiwanese global market leader TSMC. Now, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) from Shanghai is one of its main suppliers.

SMIC is a state-owned enterprise. It has a mandate from Beijing to master the technology for the necessary high-performance chips itself as soon as possible. While Huawei’s 7-nanometer processor is already considered cutting-edge performance for SMIC, TSMC, however, is already advancing into the three-nanometer range. And the rule for chips is the smaller, the more powerful. The latest iPhone and Samsung models already have a 4-nanometer chip. fin

The fate of the Uyghurs unites government and opposition factions in the German Bundestag. Derya Tuerk-Nachbaur (SPD), Peter Heidt (FDP), Boris Mijatović (Greens), Michael Brand and Norbert Altenkamp (both CDU) belong to the core group of MPs who want to raise awareness of the situation in Xinjiang province. Tuerk-Nachbaur spoke of a “creeping genocide before our eyes.” Even former UN Human Rights Commissioner Michelle Bachelet spoke of “ongoing crimes against humanity” in Xinjiang.

“Germany must show more responsibility,” the founding MPs demanded, and other parliamentarians want to join them. Peter Heidt explained that China is a decisive player in the global economy, and numerous German companies, such as VW, are represented there. “We don’t want them to leave the region, but we tell them: ‘Take notice!’” Fellow party member Ulrich Lechte added, “We want to raise awareness when VW builds a big plant there surrounded by 30 Uyghur camps.” The MPs will also discuss the informal Chinese police stations in Germany, which are meant to keep an eye on the Chinese opposition – including the Uyghurs.

The Friends of the Uyghurs support the careful distance that emerges from Germany’s recently announced China strategy. Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock emphasized it once again on Tuesday. At the annual meeting of German diplomats, she appealed to German companies to review their dependencies on China, “which in case of doubt could result in a broken neck.” Horand Knaup

TikTok has set up a center in Dublin to store data in Europe. The company is building two additional data centers in Ireland and Norway, Bloomberg reports. According to TikTok’s Vice-President Public Policy Europe, Theo Bertram, European user data is currently being migrated to the Dublin server farm.

The move is part of the company’s “Project Clover,” a series of privacy and security initiatives to address EU regulators’ concerns about the social media app. TikTok’s Project Clover aims to assure Europeans that the Chinese government cannot access their data. A similar program called “Project Texas” exists in the US.

Furthermore, TikTok has hired the British security firm NCC to audit its data controls and protection measures in Europe. TikTok committed to storing European user data locally in the future. By 2024, all European user data will be transferred to European locations. cyb

On Tuesday, Hong Kong’s highest court partially upheld an LGBTQ activist’s lawsuit seeking recognition of same-sex partnerships. However, it ruled unanimously against same-sex marriages. The Court of Appeal’s decision came after a five-year legal battle fought by imprisoned activist Jimmy Sham.

The judges denied Sham the constitutional right to same-sex marriage in Hong Kong, but gave the government two years to ensure rights such as access to hospitals or inheritance arrangements for same-sex couples. rtr

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has established a bureau for private sector development. The new NDRC bureau will be tasked with tracking and analyzing the state of private sector development, NDRC Vice Chair Cong Liang said at a press conference. It will also draft and coordinate measures to support the growth of private enterprises and investment. It will also help improve communication between private companies and the government.

The problems of the private sector, actually a growth and job engine, are weighing on the entire Chinese economy. That is why its situation has received renewed attention since July, as the business magazine Caixin reports. At that time, the Communist Party and the State Council jointly announced stronger support. This was followed by measures such as tax incentives or financial aid for projects. In addition, the NDRC recommended more than 700 private investment projects to the major state banks for financial support, according to Caixin. ck

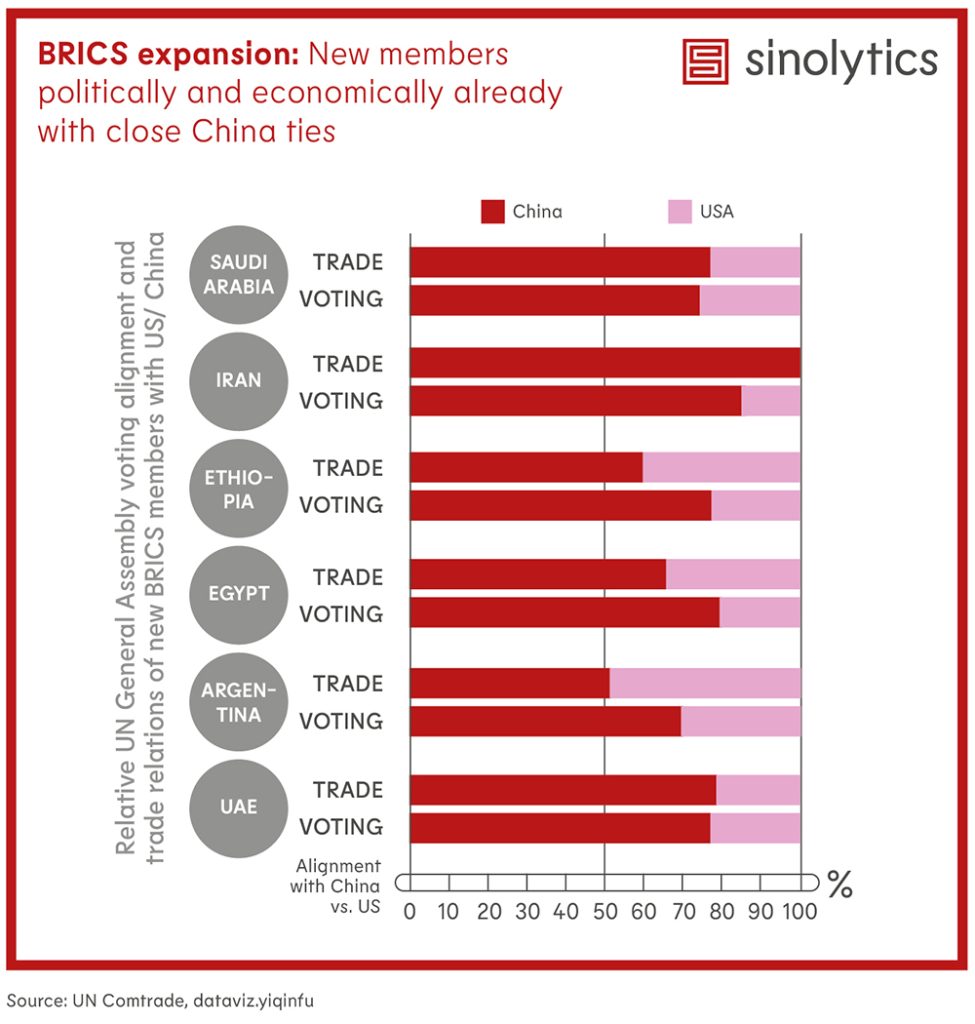

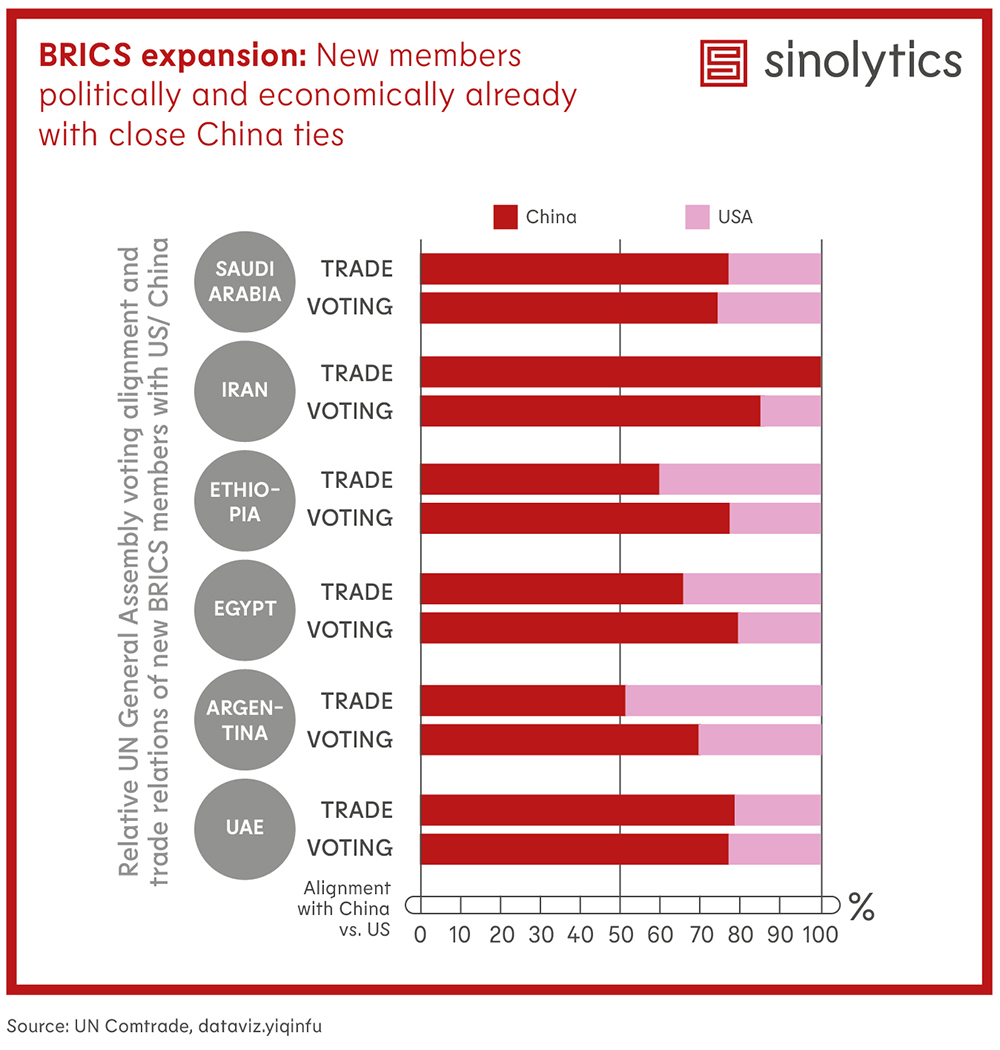

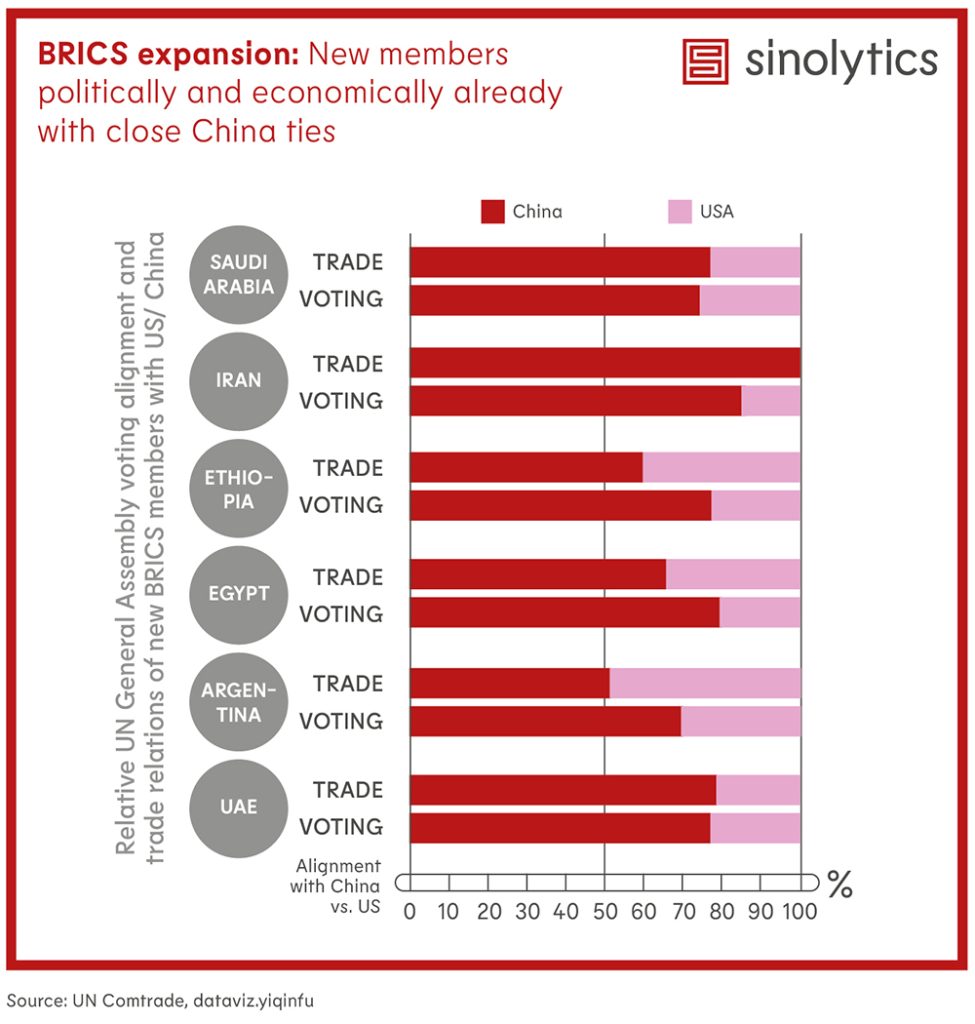

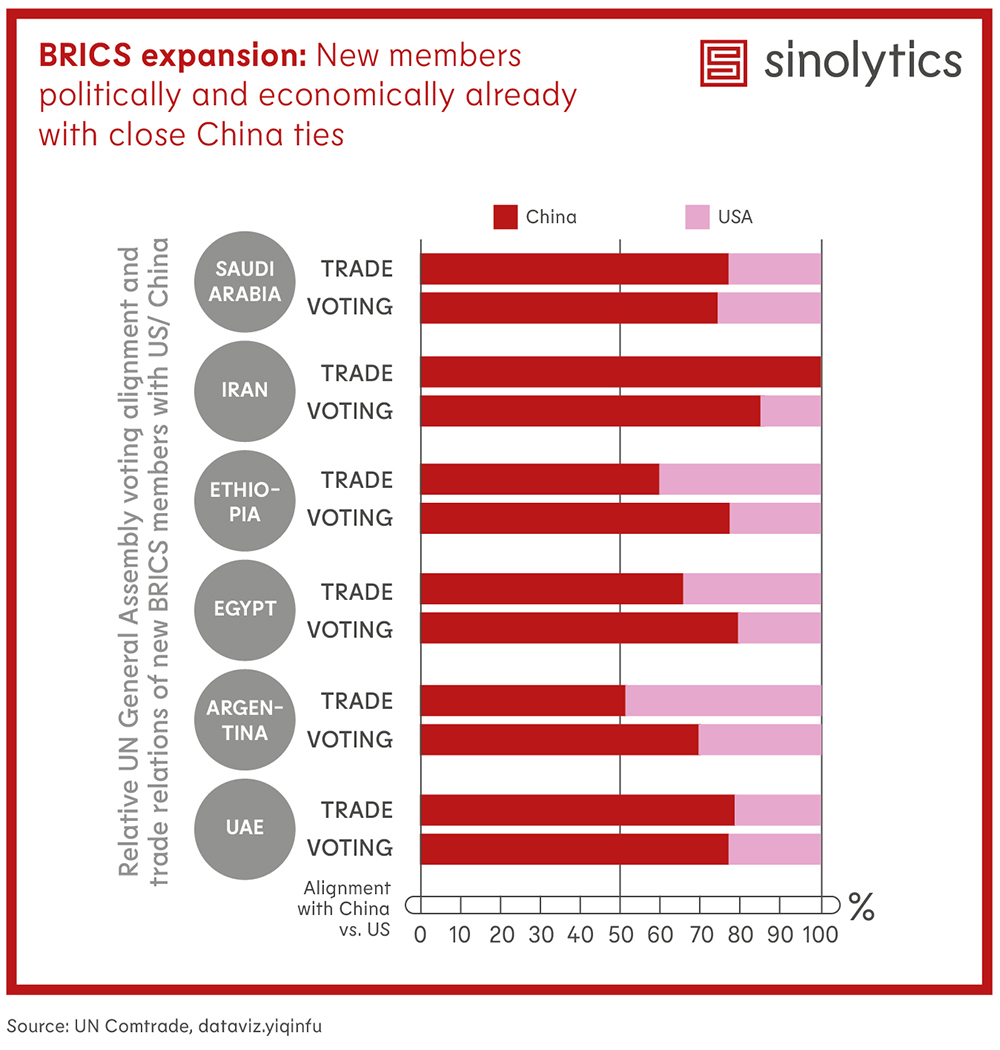

The West still hasn’t noticed that the reputation and appeal of the Western model have suffered. The BRICS expansion is an expression of the fact that the emerging and developing countries, in particular, are dissatisfied with the prevailing international order. They often have no voice or weight in international bodies. BRICS does not stand out because of its own actions, but because the West provides the impetus for them.

That is why it is not important that cohesion in the expanded group of nations is currently reduced to a few core aspects: Economy and finance, yes, but no common security strategy, for example. However, they are all united in their rejection of Western hegemony and the dollar as a reserve currency. This anti-Western sentiment resonates and appeals to many other countries as well. BRICS has picked up on a point that developing and emerging countries have long demanded: The West must change and acknowledge: US and European dominance will no longer be tolerated.

We are seeing the beginning of a global economic remapping in which China is the big winner. With still considerable growth rates and high demand for energy and raw materials, the country, like India, is extremely attractive for the BRICS group. Even though China often appears imperialistic itself, it is a kind of economic future promise for the BRICS countries.

We should not expect this club to disappear on its own anytime soon. China provides significant backing, and that makes BRICS interesting to other countries. Whether China will then have the cohesive power to unite the most diverse members and interests remains to be seen. Even if the expansion does not threaten the West at the moment, a shift is apparent.

How can, how should the West respond now? We must devise a different agenda for cooperation with emerging and developing countries. This includes the question: How do we deal with authoritarian regimes in the future while still safeguarding our own interests? What strategy do we have, for example, for the Middle East, a very difficult region of the world? And then, of course, Africa, the central focus for reorientation. To date, we have opened up far too few opportunities for a sustainable development path for this continent. China now brings hundreds of thousands of young people into its own vocational training programs for Africa. Surely, that shows what kind of appeal this model has. We, on the other hand, have failed to set an example in this area. To this day, there is no fully negotiated concept for the African Free Trade Area.

We should give impetus to the global economy, through cooperative relations, technological collaboration, fair trade, and giving emerging countries a say and representation in international organizations. And, of course, we must get a grip on our crises within Europe.

The initial reaction from German Foreign Minister Baerbock to the BRICS expansion shows how lacking in substance our foreign policy still is. Of course, we always have to talk to each other, especially when we disagree. But it is not just important to talk, but also how and about what. What do we want: systemic rivalry, strategic cooperation, de-risking? I don’t even see a discourse on that. To me, it shows that the debate on strategic foreign policy has not arrived in our ministries to this day. Illusions characterize it.

Robert Kappel is Professor Emeritus of African Economics at the University of Leipzig and a renowned Africa expert. Between 2004 and 2011, he was president of the German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA).

Christoph Nedopil Wang is the new director of the Asia Institute at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia. He replaces interim director Ian Hall, who remains professor of international relations at the institute. Nedopil Wang was previously director of the Green Finance and Development Center at Fudan University in Shanghai.

Timothy Xu has been appointed chair and CEO of Universal Music Greater China (UMGC). He succeeds longtime chairman Sunny Chang, who stepped down at the beginning of the year. Xu joins from Taihe Music Group, where he has been president and CEO since 2018. He previously served as Chairman & CEO Greater China at Sony Music Entertainment for four years.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Straight through the earth wall: Two people have been arrested in northern China after allegedly digging through the Great Wall of China. This was announced by local authorities. Their goal was to create a shortcut. The breach is said to be large enough to drive an excavator through, and the damage is “irreversible.” Construction of the structure took well over 2,000 years. While only old mud walls like the one in the photo are still visible in western China, the world-famous sections of the wall near Beijing date back to the Ming Dynasty (1386-1644). The wall was more than 20,000 kilometers in total length. In 1987, it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

At the beginning of the new Silk Road was a speech by President Xi Jinping in Kazakhstan. At the time, no one would have guessed that his idea of connecting Central Asia would one day lead to an infrastructure project worth billions. Today, the new Silk Road (also known as the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI for short) has almost 150 member countries, where China is making varying levels of investment. The G7 countries have not joined the initiative. The only exception is Italy, which is currently considering leaving it.

Currently, the biggest BRI partners are not in Central Asia, but on the Arabian Peninsula. China has signed many significant contracts with them in recent months, explains Finn Mayer-Kuckuk in collaboration with Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI). One reason is the Gulf states’ interest in technologies related to the energy transition. And China is strong in this area. In the meantime, China is cooperating with Central Asia in transport infrastructure, as once planned, to revive old trade routes.

Xi explained his fascination with the ancient Silk Road at the time of his speech in 2013 by claiming to have heard the call of the camels from the desert. At first, no one took all his plans seriously, as Frank Sieren analyzes. Not even the state media got on board with the idea. It first had to get on the agenda of a party meeting for the CP grandees to realize that the project is important to Xi. By now, China has now more than achieved its goal of doubling trade with Silk Road partners.

China’s activities along the new Silk Road (“Belt and Road” Initiative, BRI) have concentrated on the Middle East and Central Asia in the first half of the year. This is shown by the ongoing evaluation of Belt and Road investments by Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI). GTAI is the German government’s agency for foreign trade and location marketing.

The most important Silk Road partners are currently located on the Arabian Peninsula. The largest number of contracts have been signed with players in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. This fits in with the trend of increasing Chinese involvement in the Middle East. The trade relations are certainly reciprocal: Saudi Arabia is also heavily engaged in China. The country has also been involved in the BRICS Group since the end of August.

The background: Even the oil countries see the era of fossil energy sources ending. For this reason, they are interested in cooperating in the field of new industries related to the energy transition:

A total of 41 contracts were concluded with Arab partners. In the entire Middle East, the number of contracts concluded has increased from 40 to 70 since last year.

According to the GTAI, the Central Asia Summit in Xi’an in May also boosted BRI cooperation. As expected, the focus here continues to be on transport infrastructure. Most contracts in this area have been signed with partners from Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The current flagship project is a rail link from Kashgar in Xinjiang via Osh in Kyrgyzstan to Tashkent in Uzbekistan. The line had been planned since the 1990s and is now finally coming to fruition.

Construction of such large-scale projects is not only driven by the release of BRI funds by China and the development banks. Russia had long opposed the expansion of Chinese influence in the ex-Soviet republics. Since the beginning of the war, however, Moscow has been accommodating Beijing on many issues. This also made the Central Asia railway from Kashgar to Tashkent possible, a project Russia had long resisted.

While China’s construction companies once took on a decent share of these projects themselves, their business is now shrinking, as GTAI figures show. Despite the Silk Road activities, China’s construction companies have never managed to outpace their European competitors.

This year’s overall picture shows a shift in Silk Road activity away from South America and Europe towards the Middle East and Central Asia. A striking exception is a joint investment with Russia in Bolivia. There, battery specialist CATL is securing access to lithium. The Russian energy company Rosatom has been a co-investor here since this year.

It is 7 September 2013 at around half past ten in the morning. The hall is packed with students, politicians and journalists. “Nazarbayev University” is written in gold letters above the stage. Below it sits the person who gave the university its name, Nursultan Nazarbayev, President of Kazakhstan at the time. The lecture hall looks like a small, venerable parliament. Dark wood, dark walls. The heavy desks for the audience, arranged in a semicircle, ascend row by row towards the back of the room.

The university is located in Astana, the new capital of the largest Central Asian country, a city “younger than Google,” as Nazarbayev liked to emphasize. It celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2022. Before that, Kazakhstan’s largest city Almaty (Alma-Ata) had been the capital.

Standing at the podium that morning is Chinese President Xi Jinping dressed in a dark suit. He has only been in office for half a year at the time. “Shaanxi, my home province, is right at the starting point of the ancient Silk Road,” Xi says. “As I stand here and look back at that episode of history, I could almost hear the camel bells echoing in the mountains and see the wisp of smoke rising from the desert.” Kazakhstan played an important role in exchanges between East and West more than 2,100 years ago. “A near neighbor is better than a distant relative,” Xi flattered the Kazakhs.

For good reason: The country, with its population of 18 million, is geographically one of the ten largest countries in the world – and one of the 15 countries with the highest amount of mineral resources. And it shares a 1,900-kilometer border with China. Only the border with Russia is longer.

The Eurasian region must now reinvent itself and jointly build “an economy belt along the Silk Road,” Xi explains his plan. The speech in Astana is considered the starting signal for the New Silk Road. The day before, Xi just arrived from St. Petersburg, where he attended his first G20 summit as president. He did not mention a word about his plans for the Eurasian continent there.

Xi’s plan at the time was to more than double China’s trade volume with partner countries on the New Silk Road in about ten years. It even turned out to be an additional 110 percent. In the first half of 2023, trade is already at 964 billion US dollars. Despite the economic crisis, this represents a growth of 9.6 percent compared to the previous year, while trade with Europe has slumped by 4.9 percent and trade with the USA by over 14 percent.

Xi had already shown his geopolitical intentions by the order of his first foreign trips as Chinese president. His first trip was to Russia. Then Xi continued to tour the countries of Africa, with the 5th BRICS Summit in South Africa at the end. His second big trip was to Central Asia, then to the aforementioned G20 summit in St. Petersburg, then to Kazakhstan for the Silk Road speech – and finally to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Kyrgyzstan’s capital, Bishkek. Only then followed Europe (March 2014) and the USA (2015).

It was a clear signal that Xi does not want to follow behind the large established Western states, but wants to band together with the small emerging countries and collectively rebuild the global order as the majority of the world: “Let us join hands to carry on our traditional friendship and build a bright future together,” Xi then also beckoned in Astana.

In the beginning, Xi has a problem: His speech finds practically no global resonance. Even the party papers in China tend to compulsorily comment (“important speech”) on their party leader’s plan. At first, journalists and commentators seem to think the plan for a “joint economic belt” is a friendly gesture toward the Kazakhs.

Not much happens in the weeks after the speech. Most quickly forgot about the topic, although Xi gave another similar speech in front of the parliament in Jakarta a month later, in which he spoke of a maritime Silk Road.

But in the fall of 2013, the term “New Silk Road Economic Belt” appears in the document of the annual meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. It is the first under the leadership of the new state and party leader. Now it dawns on everyone: The project is important after all.

But it only gradually turns out that Xi Jinping is actually planning to build a series of economic belts from China to the West. Skepticism is high in China. Xi, however, is pushing the project with all propaganda force. Special pages appear in Chinese newspapers, one event after the next is organized. Funds are set up. The cities in western China have to get involved in constructing the New Silk Road.

In March 2014, Xi then travels to the German city of Duisburg, Europe’s largest inland port, as part of his first trip to the EU. Xi is there to welcome one of the first trains that would regularly travel from the Chinese metropolis of Chongqing and other cities to Duisburg. Today, up to 60 trains a week run between Duisburg and various Chinese destinations. However, the train runs are still subsidized by the Chinese government. A train can only carry a maximum of 60 containers per trip, while a single ship can carry up to 10,000 containers.

The BRI will not be China’s solo but an inspiring chorus, Xi emphasized in his speech in Astana. He said the countries along the New Silk Road must become more independent, secure and stable. These countries also realize: China does not give handouts. Nevertheless, after assessing the opportunities and risks, many believe that the opportunities ultimately outweigh the risks. By now, 149 countries are members of the Belt and Road Initiative. The UN has 193 member states.

The only country that is currently thinking about leaving is Italy. It is the only major Western developed nation, and the only G7 country in the BRI club. That is bitter for Beijing. Overall, however, Xi is much further ahead than initially planned. After all, the official title of his 2013 speech was: Xi wants to build a “Silk Road Economic Belt” with the “Central Asian countries.”

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

German Research Minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger also sees science as having a responsibility in collaborating and competing with China: The research community must ask itself what the “red lines” are for projects and how they can be drawn and maintained, she said on Tuesday evening at an event hosted by the German China think tank Merics on the subject of innovation. The liberal FDP politician also called for more self-confidence vis-à-vis China, including from the perspective of the political system. “We have something to offer,” Stark-Watzinger stressed. “Freedom is our greatest competitive advantage, which is why we must defend it.”

According to Stark-Watzinger, however, decision-making processes must still be accelerated in order to make innovations competitive. “Innovation policy is the best industrial policy we have,” said the minister. She also called for more sovereignty in key technologies. This was not a “luxury option” or “nice to have” but fundamental. Nevertheless, Stark-Watzinger spoke out against a decoupling from China. When it comes to innovation, de-risking is necessary, not decoupling or deglobalization. On the contrary: “It is more important than ever that we look for partners who share our values.”

Jakob Edler, Executive Director of the Fraunhofer Institute, also warned against simply severing all ties with China. Edler stressed that China is on its way to becoming a very strong science player. “China has autonomy on the one hand and is a strong international scientific player on the other. We have to take note of that.”

In a recent guest article in the German daily FAZ, Stark-Watzinger cautioned that Germany should not be naïve in its dealings with a regime that “proclaims the goal of transferring the results of civilian research into military applications and of achieving dominance in critical technologies.” ari

Huawei is now regularly supplied with a powerful chip in modern 7-nanometer technology by the Chinese semiconductor manufacturer SMIC. The recently unveiled Mate 60 Pro smartphone model uses a Kirin 9000 series processor, which proves China’s technical capabilities. In response to US sanctions in the semiconductor sector, China is currently gradually acquiring the necessary skills to manufacture high-performance chips itself. The new mobile phone will be launched later this month. Experts had disassembled the new model and identified the chip.

The Kirin 9000 is manufactured by the semiconductor specialist HiSilicon, owned by the Huawei Group. HiSilicon does not own any factories itself, but awards manufacturing contracts. Before the sanctions, it commissioned a lot of production from the Taiwanese global market leader TSMC. Now, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) from Shanghai is one of its main suppliers.

SMIC is a state-owned enterprise. It has a mandate from Beijing to master the technology for the necessary high-performance chips itself as soon as possible. While Huawei’s 7-nanometer processor is already considered cutting-edge performance for SMIC, TSMC, however, is already advancing into the three-nanometer range. And the rule for chips is the smaller, the more powerful. The latest iPhone and Samsung models already have a 4-nanometer chip. fin

The fate of the Uyghurs unites government and opposition factions in the German Bundestag. Derya Tuerk-Nachbaur (SPD), Peter Heidt (FDP), Boris Mijatović (Greens), Michael Brand and Norbert Altenkamp (both CDU) belong to the core group of MPs who want to raise awareness of the situation in Xinjiang province. Tuerk-Nachbaur spoke of a “creeping genocide before our eyes.” Even former UN Human Rights Commissioner Michelle Bachelet spoke of “ongoing crimes against humanity” in Xinjiang.

“Germany must show more responsibility,” the founding MPs demanded, and other parliamentarians want to join them. Peter Heidt explained that China is a decisive player in the global economy, and numerous German companies, such as VW, are represented there. “We don’t want them to leave the region, but we tell them: ‘Take notice!’” Fellow party member Ulrich Lechte added, “We want to raise awareness when VW builds a big plant there surrounded by 30 Uyghur camps.” The MPs will also discuss the informal Chinese police stations in Germany, which are meant to keep an eye on the Chinese opposition – including the Uyghurs.

The Friends of the Uyghurs support the careful distance that emerges from Germany’s recently announced China strategy. Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock emphasized it once again on Tuesday. At the annual meeting of German diplomats, she appealed to German companies to review their dependencies on China, “which in case of doubt could result in a broken neck.” Horand Knaup

TikTok has set up a center in Dublin to store data in Europe. The company is building two additional data centers in Ireland and Norway, Bloomberg reports. According to TikTok’s Vice-President Public Policy Europe, Theo Bertram, European user data is currently being migrated to the Dublin server farm.

The move is part of the company’s “Project Clover,” a series of privacy and security initiatives to address EU regulators’ concerns about the social media app. TikTok’s Project Clover aims to assure Europeans that the Chinese government cannot access their data. A similar program called “Project Texas” exists in the US.

Furthermore, TikTok has hired the British security firm NCC to audit its data controls and protection measures in Europe. TikTok committed to storing European user data locally in the future. By 2024, all European user data will be transferred to European locations. cyb

On Tuesday, Hong Kong’s highest court partially upheld an LGBTQ activist’s lawsuit seeking recognition of same-sex partnerships. However, it ruled unanimously against same-sex marriages. The Court of Appeal’s decision came after a five-year legal battle fought by imprisoned activist Jimmy Sham.

The judges denied Sham the constitutional right to same-sex marriage in Hong Kong, but gave the government two years to ensure rights such as access to hospitals or inheritance arrangements for same-sex couples. rtr

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has established a bureau for private sector development. The new NDRC bureau will be tasked with tracking and analyzing the state of private sector development, NDRC Vice Chair Cong Liang said at a press conference. It will also draft and coordinate measures to support the growth of private enterprises and investment. It will also help improve communication between private companies and the government.

The problems of the private sector, actually a growth and job engine, are weighing on the entire Chinese economy. That is why its situation has received renewed attention since July, as the business magazine Caixin reports. At that time, the Communist Party and the State Council jointly announced stronger support. This was followed by measures such as tax incentives or financial aid for projects. In addition, the NDRC recommended more than 700 private investment projects to the major state banks for financial support, according to Caixin. ck

The West still hasn’t noticed that the reputation and appeal of the Western model have suffered. The BRICS expansion is an expression of the fact that the emerging and developing countries, in particular, are dissatisfied with the prevailing international order. They often have no voice or weight in international bodies. BRICS does not stand out because of its own actions, but because the West provides the impetus for them.

That is why it is not important that cohesion in the expanded group of nations is currently reduced to a few core aspects: Economy and finance, yes, but no common security strategy, for example. However, they are all united in their rejection of Western hegemony and the dollar as a reserve currency. This anti-Western sentiment resonates and appeals to many other countries as well. BRICS has picked up on a point that developing and emerging countries have long demanded: The West must change and acknowledge: US and European dominance will no longer be tolerated.

We are seeing the beginning of a global economic remapping in which China is the big winner. With still considerable growth rates and high demand for energy and raw materials, the country, like India, is extremely attractive for the BRICS group. Even though China often appears imperialistic itself, it is a kind of economic future promise for the BRICS countries.

We should not expect this club to disappear on its own anytime soon. China provides significant backing, and that makes BRICS interesting to other countries. Whether China will then have the cohesive power to unite the most diverse members and interests remains to be seen. Even if the expansion does not threaten the West at the moment, a shift is apparent.

How can, how should the West respond now? We must devise a different agenda for cooperation with emerging and developing countries. This includes the question: How do we deal with authoritarian regimes in the future while still safeguarding our own interests? What strategy do we have, for example, for the Middle East, a very difficult region of the world? And then, of course, Africa, the central focus for reorientation. To date, we have opened up far too few opportunities for a sustainable development path for this continent. China now brings hundreds of thousands of young people into its own vocational training programs for Africa. Surely, that shows what kind of appeal this model has. We, on the other hand, have failed to set an example in this area. To this day, there is no fully negotiated concept for the African Free Trade Area.

We should give impetus to the global economy, through cooperative relations, technological collaboration, fair trade, and giving emerging countries a say and representation in international organizations. And, of course, we must get a grip on our crises within Europe.

The initial reaction from German Foreign Minister Baerbock to the BRICS expansion shows how lacking in substance our foreign policy still is. Of course, we always have to talk to each other, especially when we disagree. But it is not just important to talk, but also how and about what. What do we want: systemic rivalry, strategic cooperation, de-risking? I don’t even see a discourse on that. To me, it shows that the debate on strategic foreign policy has not arrived in our ministries to this day. Illusions characterize it.

Robert Kappel is Professor Emeritus of African Economics at the University of Leipzig and a renowned Africa expert. Between 2004 and 2011, he was president of the German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA).

Christoph Nedopil Wang is the new director of the Asia Institute at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia. He replaces interim director Ian Hall, who remains professor of international relations at the institute. Nedopil Wang was previously director of the Green Finance and Development Center at Fudan University in Shanghai.

Timothy Xu has been appointed chair and CEO of Universal Music Greater China (UMGC). He succeeds longtime chairman Sunny Chang, who stepped down at the beginning of the year. Xu joins from Taihe Music Group, where he has been president and CEO since 2018. He previously served as Chairman & CEO Greater China at Sony Music Entertainment for four years.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

Straight through the earth wall: Two people have been arrested in northern China after allegedly digging through the Great Wall of China. This was announced by local authorities. Their goal was to create a shortcut. The breach is said to be large enough to drive an excavator through, and the damage is “irreversible.” Construction of the structure took well over 2,000 years. While only old mud walls like the one in the photo are still visible in western China, the world-famous sections of the wall near Beijing date back to the Ming Dynasty (1386-1644). The wall was more than 20,000 kilometers in total length. In 1987, it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.