Last month, two violent attacks on foreigners in very different parts of China caused shock. According to our author, this is no coincidence, despite the country’s sheer size – on the contrary, he holds the authorities’ hate speech largely responsible for the rampant xenophobia. The argument: Anyone who dares to be verbally abusive towards supposedly different people in what is probably the most sophisticated censorship system in the world knows that it is being more than tolerated. Today in China.Table, we explain what the government hopes to gain from antagonizing foreigners and how it tries to downplay these escalations to isolated cases.

In addition, Joern Petring goes into more detail in our preliminary report on next week’s Third Plenum, which will set the course for economic policy in the coming years, not just for China. It is about plans to cap the salaries of top executives at state-owned Chinese financial institutions. This plan has its critics, but also a lot of support among the population – after all, it is also a game of envy and prejudice.

Just before the Third Plenum, China’s government has once again sent out a signal that is likely to unsettle the economy. As part of President Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” campaign, Beijing apparently wants to cap the salaries of top bankers. As the Hong Kong newspaper South China Morning Post (SCMP) reported, citing sources familiar with the matter, annual salaries in the state-owned financial sector will be limited to around three million yuan (approx. 380,000 euros).

The government aims to combat “extravagance and hedonism” in the sector and reduce the wealth gap, the newspaper continued. The planned cap would apply to all brokerage houses, investment funds and banks in which the state has a stake. Private financial institutions will be exempt. The regulation would also apply retroactively. This means that employees who have earned more than three million yuan in recent years would probably have to pay back the excess money.

The timing of the measure is likely to raise eyebrows among business representatives. After all, the eagerly anticipated Third Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party begins next Monday (July 15) in Beijing. Observers do not expect the gathering, which only takes place every five years and at which important economic reforms are traditionally announced, to yield any actual reform breakthroughs this time. However, some optimists hope for announcements that will provide a tailwind for the economy and consumption.

However, the decision to restrict salaries could well find support among parts of the population. “The financial industry hasn’t done much to contribute to the real economy in recent years and the industry’s image isn’t that good among the public,” the SCMP quoted Shanghai fund manager Dai Ming as saying. “Judging from the public’s perspective, the pay cut and cap is justified and reasonable,” Shanghai banker Wang Chen was also quoted as saying. He added that the industry had done bad business in recent years and should now also cut salaries.

China’s financial sector is indeed going through difficult times. It has been hit by a three-year bear market on the Chinese stock exchanges and the collapse of the real estate market. Anti-corruption investigations are also ongoing in numerous banks. According to calculations by the financial service Bloomberg, at least 130 financial officials and executives were investigated or punished in 2023 alone.

Bloomberg further reports that some of the new salary rules are already being enforced. Large state-owned companies reportedly have already asked senior executives to waive their bonuses. In some cases, bankers have probably also had to pay back salaries from previous years. Accordingly, they were not allowed to exceed an upper limit of 2.9 million yuan annually.

Xi has been pushing the “common prosperity” campaign since around 2021. It aims to reduce income inequality in the country and achieve a fairer distribution of wealth. The term “common prosperity” (共同富裕, gòngtóng fùyù) describes a vision in which economic prosperity not only benefits a small elite, but is distributed more broadly across society.

Specifically, the campaign includes measures such as tax reforms, stronger regulations on large tech companies, real estate developers and banks, as well as the development of rural areas. The state is also investing more in education and healthcare. Some of these measures are also expected to be discussed at the Third Plenum. Companies are also encouraged to fulfill their social obligations and contribute more to society.

However, critics also see risks in the campaign. They warn that too much intervention in the private sector could slow down economic growth. Critics also warn that the campaign could be used to consolidate the Communist Party’s control over society.

Two recent attacks on foreigners in different parts of China last month have shone a spotlight on China’s nationalist propaganda. They sparked fierce criticism of xenophobic rhetoric from the authorities, which some blamed for the attacks – the condemnation of xenophobic rhetoric highlighted growing public resistance against government manipulation.

On June 10, four instructors from a US college were stabbed by a Chinese man in a park in Jilin, in Northeast China’s Jilin Province. On June 24, a 52-year-old Chinese man attacked a Japanese boy and his mother with a knife while the latter two were about to step on a bus for Japanese school children in Suzhou, a prosperous city next to Shanghai. Then, the assailant attempted to force himself into the bus to attack other passengers but was stopped by the conductor, Hu Youping, a 54-year-old local resident. The man stabbed her before being subdued by passers-by rushing to the scene to help.

The mother suffered minor injuries and the boy was taken to hospital, but his life was not in danger. According to official information, the bus driver succumbed to her stab wounds on June 26. The Japanese embassy in Beijing subsequently lowered the national flag to half-mast.

Government representatives tried to separate the two attacks from general xenophobia. The authorities emphasized that neither attack had a xenophobic background and that they were “isolated incidents.” At the same time, major social media platforms, obviously under authorities’ instructions, announced they would crack down on “extreme nationalism and speech instigating Sino-Japanese antagonism.” Nevertheless, the crackdown will certainly be half-hearted and short-lived as China under Xi Jinping will not change its hostility towards the West.

Many critics still linked them with hatred towards people of certain countries, especially Japan and the United States. “There is no reason that can explain the attacks other than the long-standing, pervasive deliberately negative portraying (of certain groups),” said one WeChat channel titled Jue Jing, which comments on current affairs. “If these attacks are isolated incidents, as the government said, then what about the many likes and cheers under the news of the attacks?” asked Xiang Dongliang, a liberal writer, on his WeChat channel.

China has probably the most sophisticated censoring system in the world. However, abusive posts and comments are ubiquitous and the censors turn a blind eye to them. The list of people that are targeted is long, including: Japanese, Americans, black people, Muslims, Indians, government critics, feminists and the LGBT community. The latest addition are Jews.

The underlying causes of the hatred include racism and sexism. But the most important factor is government policy. One example is Jews. For decades, China has maintained a good relationship with both the Arabic world and Israel. Jews were seen predominantly in China as being intelligent, tenacious and friendly to China.

After the breakout of the Gaza war last year, the Chinese government, after calculations, decided to abandon Israel, apparently to make its Middle-East policy fit better in its bid to become the leader of the Global South. Official media one-sidedly reported Israel’s brutality while playing down atrocities committed by Hamas. Waves of netizens’ verbal attacks on Jews immediately followed.

But the best example is still the anti-Japanese sentiment. Japan invaded China in the 1930s and 1940s, committing horrendous atrocities. Japan’s repentance didn’t go as far as Germany’s, but it did make great efforts to reconcile and gave China huge sums of economic and technological assistance from the late 1970s until the first decade of this century.

For its own political interests, the Chinese government didn’t want antagonism towards Japan, particularly in light of Japan’s alliance with the United States, China’s arch-rival. In 2023, the government’s effort to denigrate Japan reached a new level. When Japan decided to release treated radioactive water from the ruined Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the ocean, Chinese officials insisted it would contaminate the seawater, ignoring scientists’ endorsement of release. Posts defending the discharge were deleted; people arguing for the discharge were forced to apologize.

As a result of the government’s avowed hostility, Japan-bashing is among the top politically correct topics in the Chinese media. The Sino-Japanese War has been an evergreen theme for Chinese TV dramas. Chinese fans of Japanese culture were scolded by police for wearing kimonos. Chinese owners of Japanese cars were physically attacked.

Disinformation about Japan not only went unchecked but has actually become a lucrative business. A myriad of influencers used this topic to attract traffic and earn money. In early June, an influencer from Zhejiang Province published a video of himself urinating in the controversial Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, where Japanese nationalists commemorate their dead from the Second World War.

This year, the Japanese school in Suzhou became a target of Japanese haters. According to a bilateral agreement, the Japanese school was established to provide schooling to the children of employees working in Suzhou, which houses about 3000 Japanese companies. However, many on Chinese social media claimed the school was a base for training Japanese spies.

The attack in late June created a dilemma for the Chinese Government, which fears losing foreign investment but is also reluctant to back away from its anti-Japan attitude. Government officials were silent until the foreign ministry was asked on June 28 to comment. Spokeswoman Mao Ning opted to put the stress on the bus conductor, who she said personified the “bravery and kindness of the Chinese people.”

Chinese police usually quickly announce the identity and personal details of individuals committing public offenses. But in this case, they have been cautious. No personal information other than the attacker’s last name and age was given. Local police also spoke vaguely about their investigation, saying he was a troubled man going on an indiscriminate attack to vent his frustration, without providing further details. Liu Yi

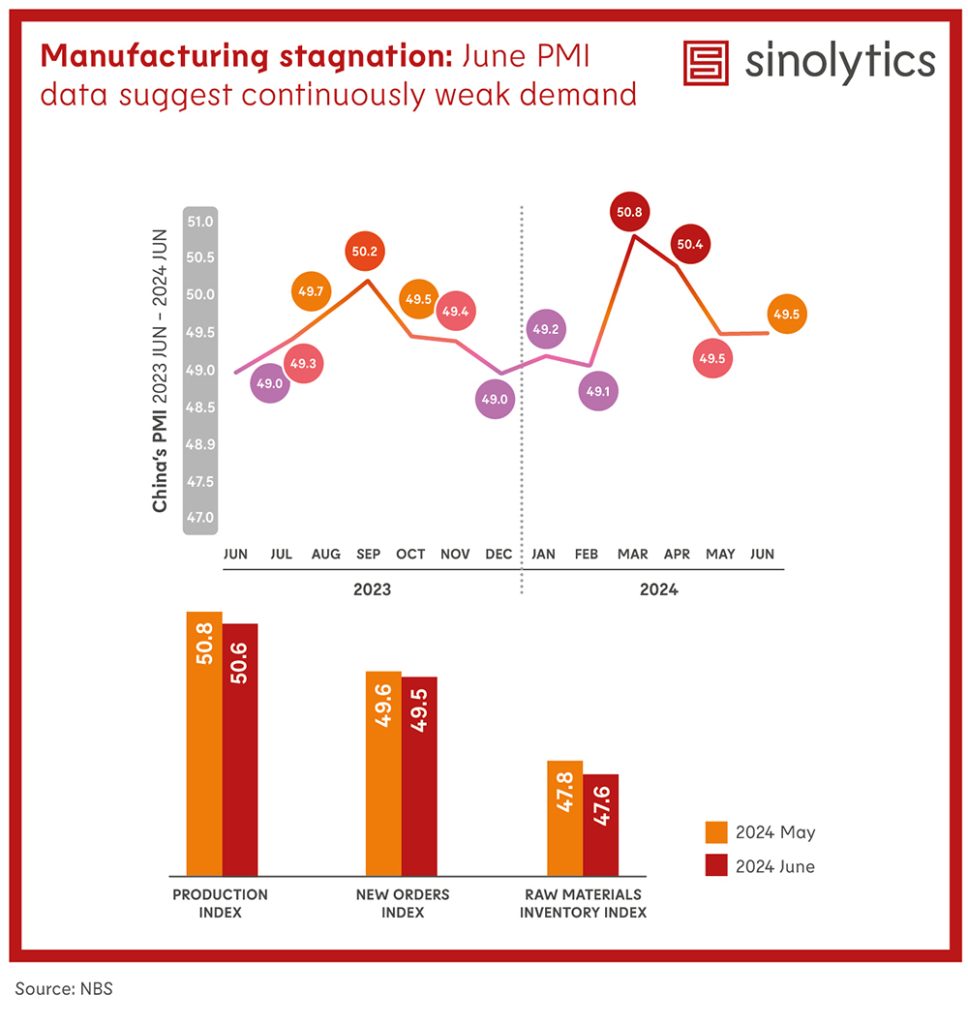

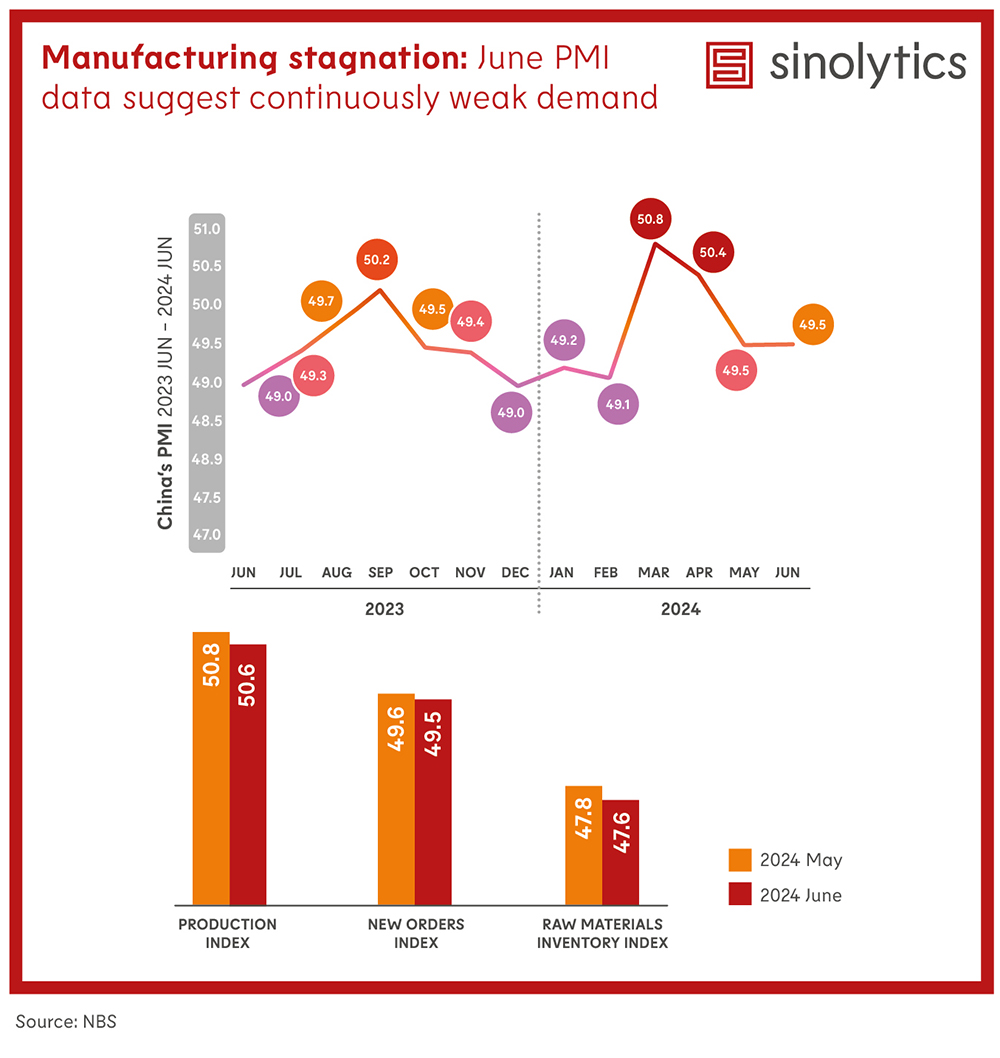

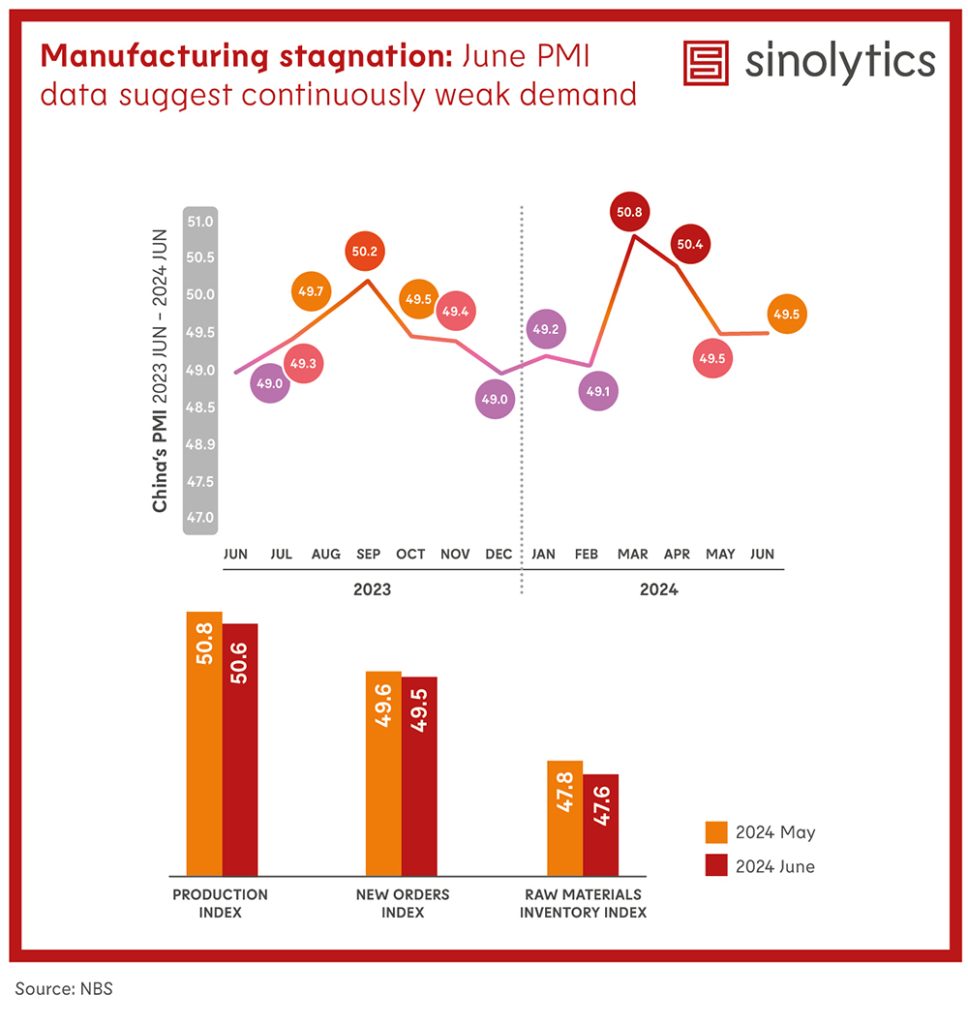

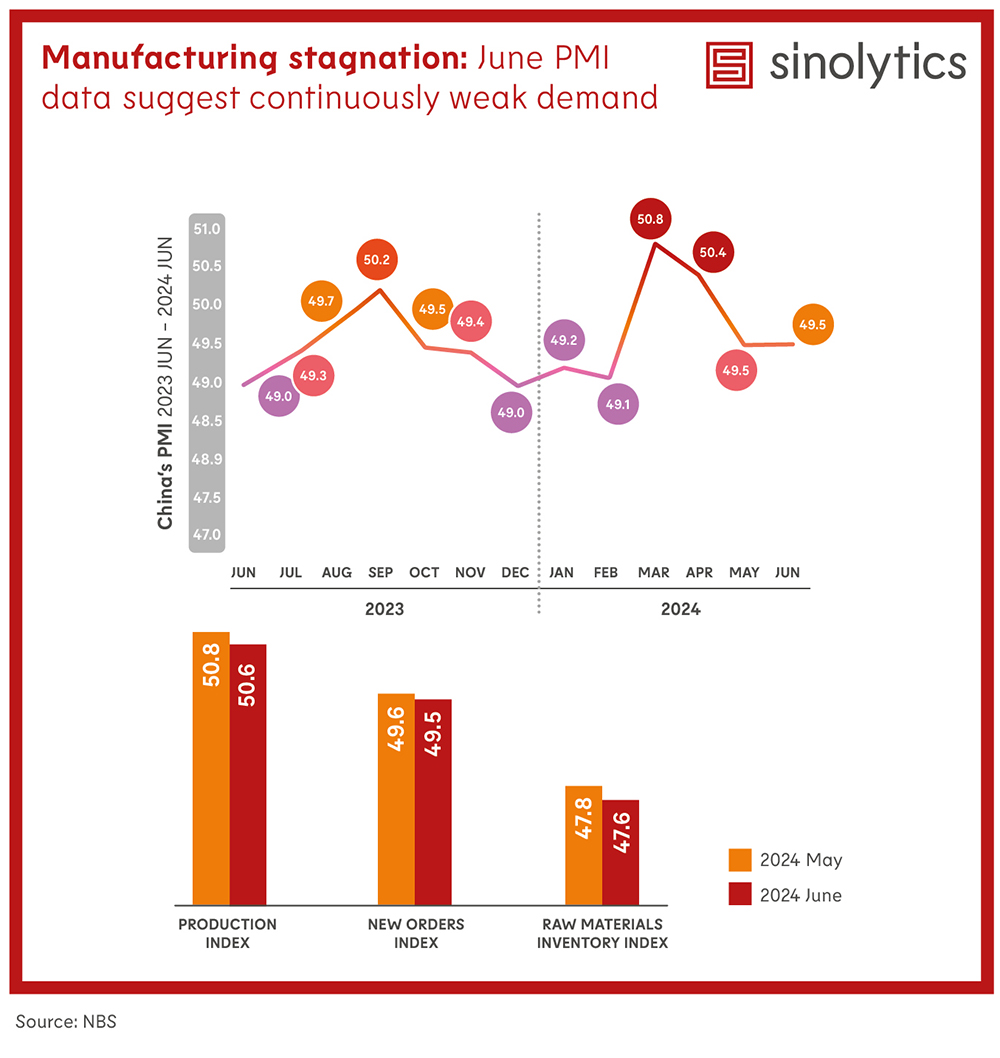

Sinolytics is a research-based business consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and specific business activities in the People’s Republic.

Emerging markets such as China, India and Brazil are contributing significantly more to the international financing of climate action measures than generally assumed. For example, a study shows that in 2020, China paid more than two billion US dollars in climate aid to other countries in the Global South, both directly and indirectly. Other G77 countries contribute hundreds of millions. This is according to an extensive study by the renowned British think tank Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

According to the study, the top ten contributors to climate financing (data from 2020) are industrialized countries, led by Japan, Germany, France and the USA. But China already ranks eleventh with 1.2 billion US dollars in direct payments. South Korea follows in 16th place, then India, Brazil, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Argentina, Mexico and Nigeria among the top 30. The ODI study counts China’s participation in international climate funds (1 million US dollars) and multilateral development banks (678 million US dollars) such as the World Bank in addition to China’s direct payments – and reaches a total of around two billion US dollars. This would make China the seventh-largest donor of international climate finance in 2017.

There are no official figures on the financial flows from emerging markets because under the climate framework convention, only industrialized countries are required to disclose their financial flows for financing, technology transfer and capacity building in poor countries. A study by the organization E3G estimates that China, for example, contributed over one billion US dollars annually to bilateral projects with countries of the Global South between 2013 and 2017, including Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects. However, climate payments account for only about two percent of total BRI investments. Nevertheless, the Chinese-controlled Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) announced plans to triple its climate financing to seven billion US dollars annually by 2030.

So far, only developed countries have committed themselves to international climate action payments. The 100 billion US dollars per year promised at COP21 from 2020 onwards were first reached and exceeded in 2022 with 116 billion, according to OECD calculations. At COP29 in Baku, the UN states want to adopt a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance. bpo

Optics specialist Carl Zeiss started operations at a new production facility in China worth 250 million yuan (around 32 million euros) on Monday, according to Caixin on Tuesday. The plant is located in an industrial park in Suzhou in the eastern Chinese province of Jiangsu and handles research and development, as well as the production of microscopes and optical measuring instruments, among other things.

The plant will primarily use the local supply chain to manufacture products for private and corporate customers based in China, said Maximilian Foerst, President and CEO of Zeiss China. Zeiss broke ground for the construction of the Suzhou plant in October 2022. The new plant is the company’s second site in Suzhou. According to Zeiss, it has been operating a component and accessory plant for surgical microscopes and slit lamps since 2009. Foerst described the move as a clear sign of the company’s long-term commitment to the Chinese market. cyb

According to a study, the use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) is nowhere as widespread as in China. A survey published on Tuesday by software company SAS and research firm Coleman Parker among 1,600 decision-makers from 16 countries and numerous industries found that 83 percent of companies in the People’s Republic use such technology. Generative AI – or GenAI – allows users to easily create text, images, music and computer code through voice commands.

In the United States, where the current AI hype began with the release of ChatGPT in late 2022, the share is 65 percent and the average for all respondents is 54 percent. The study also states that the People’s Republic is the world leader in AI surveillance. The software creates detailed profiles of people by linking and analyzing communication and movement data with other available information. In Europe, the “AI Act” will prohibit the use of AI for such purposes.

Just last week, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) announced that China had generated the most inventions in the field of GenAI in the last decade, more than six times as many as the second-placed USA. China also recently presented a draft generative AI regulation. rtr/cyb

In the first half of 2024, Chinese brands dominated the Israeli car market for the first time after overtaking the competition from Japan and South Korea. According to the official news agency Xinhua, Chinese brands even hold a two-thirds EV market share. In total, Chinese car manufacturers sold 34,602 gasoline cars and 26,803 electric cars between January and June. The Chinese companies are led by BYD, which sold 10,178 cars of its six models available in Israel. The Atto 3 SUV was the best-selling model in Israel and accounted for 71 percent of BYD sales.

The figures show how quickly Chinese car manufacturers can capture a market – even if Israel does differ from the EU as it does not have a large domestic car production. In terms of EVs, Chinese brands have already almost matched the sales figures for the entire year 2023 (29,402). This figure was also twice as high as sales in 2022. ck

For decades, Silicon Valley has been the world’s quintessential tech hub. But plenty of Asian cities – such as Bangalore, Penang, Shenzhen, Singapore, and Taipei – have been working to build similar innovation ecosystems. Shenzhen, located in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, has been particularly successful.

In 1979, as Deng Xiaoping was launching China’s “reform and opening up,” Shenzhen was a small fishing village, with a GDP of just 28 million US dollars, 37 percent of which came from primary industry. Today, Shenzhen is China’s leading innovation hub, with a GDP of nearly 500 billion US dollars, over 40 percent of which is generated by high-tech industries. Last year, high-tech products accounted for more than 50 percent of Shenzhen’s 348.4 billion US dollars in exports, and in the Global City Competitiveness Index, Shenzhen ranked seventh overall, and first in China.

Shenzhen’s transformation began in 1980, when Deng selected it as China’s first “special economic zone,” where an export-oriented economy would be developed. Firms in nearby Hong Kong – then a British colony and already a center for international trade and finance – quickly began shifting manufacturing to Shenzhen, where land and labor costs were low.

The resulting “front shop, back factory” model facilitated inflows of foreign direct investment and transfers of technology and know-how. By 1994, the FDI pouring into Shenzhen through Hong Kong-based companies accounted for nearly half of all FDI entering Guangdong province, and by 2005, the manufacturing sector accounted for 53 percent of Shenzhen’s GDP.

But Shenzhen’s transformation was just beginning. Following a 2006 government decision to promote high-tech industries and indigenous innovation in Shenzhen, investment in research and development there soared, from 3.3 percent of GDP in 2007 to 5.8 percent of GDP last year. That is even higher than the 5.6 percent reported in Israel – the country with the world’s highest R&D spending, relative to GDP.

Beyond R&D, Shenzhen invested heavily in building up its human capital. Leveraging its proximity to Hong Kong – with all the capital, talent, and market access it provided – Shenzhen developed an open, inclusive, and dynamic local innovation and business culture that appealed to talent from elsewhere in China and from abroad. Of Shenzhen’s 17.8 million permanent residents, more than 65 percent hail from outside the city.

Shenzhen also created a thriving local research ecosystem. Taking inspiration from Silicon Valley – which has nearby universities like Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley, to deliver a constant supply of top talent and cutting-edge research – Shenzhen offered world-class Chinese universities land and grants to establish local bases. Peking University, Tsinghua University, and the Chinese University of Hong Kong all have campuses in Shenzhen, and up to half of their students remain in the city to work after graduation.

Shenzhen had another key strength: a deep pool of manufacturers with the resources and capacity to build prototypes – crucial for testing the viability of new ideas or inventions. This helped to attract innovative firms, including Huawei (now valued at 128 billion US dollars), China Merchants Bank (with a market capitalization of 111.4 billion US dollars), and Ping An Financial Group, BYD, and Tencent, valued at 97.2 billion, 92.5 billion, and 443.74 billion US dollars respectively.

These five firms today rank among the top 20 companies in the country, by market value. And their promise is hardly exhausted. Consider Tencent, the world’s largest video-game publisher, the owner of the world’s top-grossing mobile game, and the developer and operator of WeChat, China’s largest and most innovative social-media platform. Tencent is also a leading venture-capital firm that has acquired or invested in more than 800 companies, both foreign and domestic. By taking stakes in innovative technology companies, from Tesla to Enflame and Zhipu (the artificial-intelligence chip startups), Tencent has established a foothold in the AI sector. In 2020, the firm announced that it would invest 70 billion US dollars in cloud computing, AI, and blockchain technology.

Beyond these established giants, Shenzhen is home to around 30 “unicorns” (unlisted companies founded after 2000 with a valuation of more than 1 billion US dollars) – almost as many as the world’s fifth-ranked country, Germany (36). One of them, the digital bank WeBank, ranks among the ten most valuable unicorns globally. It should thus not be surprising that Shenzhen boasts China’s second-largest stock market, with a total market capitalization of 4.29 trillion US dollars – larger than that of Hong Kong – and an electronic trading turnover of 1.39 trillion US dollars.

There is reason to think that Shenzhen’s economic future will be bright: its annual GDP growth, at 6 percent, outpaces that of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. But to maintain its growth and dynamism, Shenzhen will have to adapt to a rapidly changing global economic landscape, characterized by the proliferation of geopolitically motivated sanctions targeting China, especially its tech sector.

Effective adaptation is certainly possible. BYD, a world-leading electric-vehicle producer, is facing high tariffs from the United States and Europe, but it is still managing to make inroads into global markets with its cutting-edge battery technology. Huawei has weathered harsh US sanctions partly by building its own microchips and operating systems. The richness, flexibility, and business-friendly character of Shenzhen’s innovation ecosystem will enable more firms there to adapt to the challenges they face.

It helps that Shenzhen is situated within the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area, an integrated economic zone comprising nine cities and two special administrative regions. Cooperation with neighboring cities has enabled Shenzhen to deepen its links with the Global South. But now Shenzhen’s resilience as a leading manufacturing and innovation hub is facing its severest test, and its ability to make the most of these links will go a long way toward determining whether it passes.

Andrew Sheng is a distinguished fellow at the Asia Global Institute at the University of Hong Kong. Xiao Geng, Chairman of the Hong Kong Institution for International Finance, is a professor and Director of the Institute of Policy and Practice at the Shenzhen Finance Institute at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2024.

Jana Brokate has been Project Lead ChiKoN at Kiel University since June. ChiKoN, a funding measure supported by the BMBF, stands for “China Competence in the North.” Brokate lived in Beijing and Guangzhou for more than five years and worked as a project manager for AHK China, among other companies.

Shannon Ahuja has been Lead Customer Experience & Digital Ecosystem at VW China since June. For her new position, she is moving from Wolfsburg, where she most recently worked as Head of Customer Insights for the car manufacturer, to the Board Customer Committees and UX Strategy office in Beijing.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

“Are you giving me money? No? Then don’t bother me!” A young man hurled these words at an elderly passenger in the Shenyang subway after he had asked for his seat. A video of the visibly enraged passenger immediately went viral on China’s social media. Videos from Wuhan and Beijing also soon circulated, showing the clash of generations on the subway. These incidents sparked heated discussions in China, a country where respect for the elderly is traditionally held in high regard. In an online survey conducted by Sina News, over 93 percent of respondents said they did not feel obliged to give up their seats. They said that China’s young population is so overworked that it should be up to each person to decide whether they still have the strength to offer their seat out of politeness.

Last month, two violent attacks on foreigners in very different parts of China caused shock. According to our author, this is no coincidence, despite the country’s sheer size – on the contrary, he holds the authorities’ hate speech largely responsible for the rampant xenophobia. The argument: Anyone who dares to be verbally abusive towards supposedly different people in what is probably the most sophisticated censorship system in the world knows that it is being more than tolerated. Today in China.Table, we explain what the government hopes to gain from antagonizing foreigners and how it tries to downplay these escalations to isolated cases.

In addition, Joern Petring goes into more detail in our preliminary report on next week’s Third Plenum, which will set the course for economic policy in the coming years, not just for China. It is about plans to cap the salaries of top executives at state-owned Chinese financial institutions. This plan has its critics, but also a lot of support among the population – after all, it is also a game of envy and prejudice.

Just before the Third Plenum, China’s government has once again sent out a signal that is likely to unsettle the economy. As part of President Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” campaign, Beijing apparently wants to cap the salaries of top bankers. As the Hong Kong newspaper South China Morning Post (SCMP) reported, citing sources familiar with the matter, annual salaries in the state-owned financial sector will be limited to around three million yuan (approx. 380,000 euros).

The government aims to combat “extravagance and hedonism” in the sector and reduce the wealth gap, the newspaper continued. The planned cap would apply to all brokerage houses, investment funds and banks in which the state has a stake. Private financial institutions will be exempt. The regulation would also apply retroactively. This means that employees who have earned more than three million yuan in recent years would probably have to pay back the excess money.

The timing of the measure is likely to raise eyebrows among business representatives. After all, the eagerly anticipated Third Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party begins next Monday (July 15) in Beijing. Observers do not expect the gathering, which only takes place every five years and at which important economic reforms are traditionally announced, to yield any actual reform breakthroughs this time. However, some optimists hope for announcements that will provide a tailwind for the economy and consumption.

However, the decision to restrict salaries could well find support among parts of the population. “The financial industry hasn’t done much to contribute to the real economy in recent years and the industry’s image isn’t that good among the public,” the SCMP quoted Shanghai fund manager Dai Ming as saying. “Judging from the public’s perspective, the pay cut and cap is justified and reasonable,” Shanghai banker Wang Chen was also quoted as saying. He added that the industry had done bad business in recent years and should now also cut salaries.

China’s financial sector is indeed going through difficult times. It has been hit by a three-year bear market on the Chinese stock exchanges and the collapse of the real estate market. Anti-corruption investigations are also ongoing in numerous banks. According to calculations by the financial service Bloomberg, at least 130 financial officials and executives were investigated or punished in 2023 alone.

Bloomberg further reports that some of the new salary rules are already being enforced. Large state-owned companies reportedly have already asked senior executives to waive their bonuses. In some cases, bankers have probably also had to pay back salaries from previous years. Accordingly, they were not allowed to exceed an upper limit of 2.9 million yuan annually.

Xi has been pushing the “common prosperity” campaign since around 2021. It aims to reduce income inequality in the country and achieve a fairer distribution of wealth. The term “common prosperity” (共同富裕, gòngtóng fùyù) describes a vision in which economic prosperity not only benefits a small elite, but is distributed more broadly across society.

Specifically, the campaign includes measures such as tax reforms, stronger regulations on large tech companies, real estate developers and banks, as well as the development of rural areas. The state is also investing more in education and healthcare. Some of these measures are also expected to be discussed at the Third Plenum. Companies are also encouraged to fulfill their social obligations and contribute more to society.

However, critics also see risks in the campaign. They warn that too much intervention in the private sector could slow down economic growth. Critics also warn that the campaign could be used to consolidate the Communist Party’s control over society.

Two recent attacks on foreigners in different parts of China last month have shone a spotlight on China’s nationalist propaganda. They sparked fierce criticism of xenophobic rhetoric from the authorities, which some blamed for the attacks – the condemnation of xenophobic rhetoric highlighted growing public resistance against government manipulation.

On June 10, four instructors from a US college were stabbed by a Chinese man in a park in Jilin, in Northeast China’s Jilin Province. On June 24, a 52-year-old Chinese man attacked a Japanese boy and his mother with a knife while the latter two were about to step on a bus for Japanese school children in Suzhou, a prosperous city next to Shanghai. Then, the assailant attempted to force himself into the bus to attack other passengers but was stopped by the conductor, Hu Youping, a 54-year-old local resident. The man stabbed her before being subdued by passers-by rushing to the scene to help.

The mother suffered minor injuries and the boy was taken to hospital, but his life was not in danger. According to official information, the bus driver succumbed to her stab wounds on June 26. The Japanese embassy in Beijing subsequently lowered the national flag to half-mast.

Government representatives tried to separate the two attacks from general xenophobia. The authorities emphasized that neither attack had a xenophobic background and that they were “isolated incidents.” At the same time, major social media platforms, obviously under authorities’ instructions, announced they would crack down on “extreme nationalism and speech instigating Sino-Japanese antagonism.” Nevertheless, the crackdown will certainly be half-hearted and short-lived as China under Xi Jinping will not change its hostility towards the West.

Many critics still linked them with hatred towards people of certain countries, especially Japan and the United States. “There is no reason that can explain the attacks other than the long-standing, pervasive deliberately negative portraying (of certain groups),” said one WeChat channel titled Jue Jing, which comments on current affairs. “If these attacks are isolated incidents, as the government said, then what about the many likes and cheers under the news of the attacks?” asked Xiang Dongliang, a liberal writer, on his WeChat channel.

China has probably the most sophisticated censoring system in the world. However, abusive posts and comments are ubiquitous and the censors turn a blind eye to them. The list of people that are targeted is long, including: Japanese, Americans, black people, Muslims, Indians, government critics, feminists and the LGBT community. The latest addition are Jews.

The underlying causes of the hatred include racism and sexism. But the most important factor is government policy. One example is Jews. For decades, China has maintained a good relationship with both the Arabic world and Israel. Jews were seen predominantly in China as being intelligent, tenacious and friendly to China.

After the breakout of the Gaza war last year, the Chinese government, after calculations, decided to abandon Israel, apparently to make its Middle-East policy fit better in its bid to become the leader of the Global South. Official media one-sidedly reported Israel’s brutality while playing down atrocities committed by Hamas. Waves of netizens’ verbal attacks on Jews immediately followed.

But the best example is still the anti-Japanese sentiment. Japan invaded China in the 1930s and 1940s, committing horrendous atrocities. Japan’s repentance didn’t go as far as Germany’s, but it did make great efforts to reconcile and gave China huge sums of economic and technological assistance from the late 1970s until the first decade of this century.

For its own political interests, the Chinese government didn’t want antagonism towards Japan, particularly in light of Japan’s alliance with the United States, China’s arch-rival. In 2023, the government’s effort to denigrate Japan reached a new level. When Japan decided to release treated radioactive water from the ruined Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the ocean, Chinese officials insisted it would contaminate the seawater, ignoring scientists’ endorsement of release. Posts defending the discharge were deleted; people arguing for the discharge were forced to apologize.

As a result of the government’s avowed hostility, Japan-bashing is among the top politically correct topics in the Chinese media. The Sino-Japanese War has been an evergreen theme for Chinese TV dramas. Chinese fans of Japanese culture were scolded by police for wearing kimonos. Chinese owners of Japanese cars were physically attacked.

Disinformation about Japan not only went unchecked but has actually become a lucrative business. A myriad of influencers used this topic to attract traffic and earn money. In early June, an influencer from Zhejiang Province published a video of himself urinating in the controversial Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, where Japanese nationalists commemorate their dead from the Second World War.

This year, the Japanese school in Suzhou became a target of Japanese haters. According to a bilateral agreement, the Japanese school was established to provide schooling to the children of employees working in Suzhou, which houses about 3000 Japanese companies. However, many on Chinese social media claimed the school was a base for training Japanese spies.

The attack in late June created a dilemma for the Chinese Government, which fears losing foreign investment but is also reluctant to back away from its anti-Japan attitude. Government officials were silent until the foreign ministry was asked on June 28 to comment. Spokeswoman Mao Ning opted to put the stress on the bus conductor, who she said personified the “bravery and kindness of the Chinese people.”

Chinese police usually quickly announce the identity and personal details of individuals committing public offenses. But in this case, they have been cautious. No personal information other than the attacker’s last name and age was given. Local police also spoke vaguely about their investigation, saying he was a troubled man going on an indiscriminate attack to vent his frustration, without providing further details. Liu Yi

Sinolytics is a research-based business consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and specific business activities in the People’s Republic.

Emerging markets such as China, India and Brazil are contributing significantly more to the international financing of climate action measures than generally assumed. For example, a study shows that in 2020, China paid more than two billion US dollars in climate aid to other countries in the Global South, both directly and indirectly. Other G77 countries contribute hundreds of millions. This is according to an extensive study by the renowned British think tank Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

According to the study, the top ten contributors to climate financing (data from 2020) are industrialized countries, led by Japan, Germany, France and the USA. But China already ranks eleventh with 1.2 billion US dollars in direct payments. South Korea follows in 16th place, then India, Brazil, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Argentina, Mexico and Nigeria among the top 30. The ODI study counts China’s participation in international climate funds (1 million US dollars) and multilateral development banks (678 million US dollars) such as the World Bank in addition to China’s direct payments – and reaches a total of around two billion US dollars. This would make China the seventh-largest donor of international climate finance in 2017.

There are no official figures on the financial flows from emerging markets because under the climate framework convention, only industrialized countries are required to disclose their financial flows for financing, technology transfer and capacity building in poor countries. A study by the organization E3G estimates that China, for example, contributed over one billion US dollars annually to bilateral projects with countries of the Global South between 2013 and 2017, including Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects. However, climate payments account for only about two percent of total BRI investments. Nevertheless, the Chinese-controlled Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) announced plans to triple its climate financing to seven billion US dollars annually by 2030.

So far, only developed countries have committed themselves to international climate action payments. The 100 billion US dollars per year promised at COP21 from 2020 onwards were first reached and exceeded in 2022 with 116 billion, according to OECD calculations. At COP29 in Baku, the UN states want to adopt a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance. bpo

Optics specialist Carl Zeiss started operations at a new production facility in China worth 250 million yuan (around 32 million euros) on Monday, according to Caixin on Tuesday. The plant is located in an industrial park in Suzhou in the eastern Chinese province of Jiangsu and handles research and development, as well as the production of microscopes and optical measuring instruments, among other things.

The plant will primarily use the local supply chain to manufacture products for private and corporate customers based in China, said Maximilian Foerst, President and CEO of Zeiss China. Zeiss broke ground for the construction of the Suzhou plant in October 2022. The new plant is the company’s second site in Suzhou. According to Zeiss, it has been operating a component and accessory plant for surgical microscopes and slit lamps since 2009. Foerst described the move as a clear sign of the company’s long-term commitment to the Chinese market. cyb

According to a study, the use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) is nowhere as widespread as in China. A survey published on Tuesday by software company SAS and research firm Coleman Parker among 1,600 decision-makers from 16 countries and numerous industries found that 83 percent of companies in the People’s Republic use such technology. Generative AI – or GenAI – allows users to easily create text, images, music and computer code through voice commands.

In the United States, where the current AI hype began with the release of ChatGPT in late 2022, the share is 65 percent and the average for all respondents is 54 percent. The study also states that the People’s Republic is the world leader in AI surveillance. The software creates detailed profiles of people by linking and analyzing communication and movement data with other available information. In Europe, the “AI Act” will prohibit the use of AI for such purposes.

Just last week, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) announced that China had generated the most inventions in the field of GenAI in the last decade, more than six times as many as the second-placed USA. China also recently presented a draft generative AI regulation. rtr/cyb

In the first half of 2024, Chinese brands dominated the Israeli car market for the first time after overtaking the competition from Japan and South Korea. According to the official news agency Xinhua, Chinese brands even hold a two-thirds EV market share. In total, Chinese car manufacturers sold 34,602 gasoline cars and 26,803 electric cars between January and June. The Chinese companies are led by BYD, which sold 10,178 cars of its six models available in Israel. The Atto 3 SUV was the best-selling model in Israel and accounted for 71 percent of BYD sales.

The figures show how quickly Chinese car manufacturers can capture a market – even if Israel does differ from the EU as it does not have a large domestic car production. In terms of EVs, Chinese brands have already almost matched the sales figures for the entire year 2023 (29,402). This figure was also twice as high as sales in 2022. ck

For decades, Silicon Valley has been the world’s quintessential tech hub. But plenty of Asian cities – such as Bangalore, Penang, Shenzhen, Singapore, and Taipei – have been working to build similar innovation ecosystems. Shenzhen, located in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, has been particularly successful.

In 1979, as Deng Xiaoping was launching China’s “reform and opening up,” Shenzhen was a small fishing village, with a GDP of just 28 million US dollars, 37 percent of which came from primary industry. Today, Shenzhen is China’s leading innovation hub, with a GDP of nearly 500 billion US dollars, over 40 percent of which is generated by high-tech industries. Last year, high-tech products accounted for more than 50 percent of Shenzhen’s 348.4 billion US dollars in exports, and in the Global City Competitiveness Index, Shenzhen ranked seventh overall, and first in China.

Shenzhen’s transformation began in 1980, when Deng selected it as China’s first “special economic zone,” where an export-oriented economy would be developed. Firms in nearby Hong Kong – then a British colony and already a center for international trade and finance – quickly began shifting manufacturing to Shenzhen, where land and labor costs were low.

The resulting “front shop, back factory” model facilitated inflows of foreign direct investment and transfers of technology and know-how. By 1994, the FDI pouring into Shenzhen through Hong Kong-based companies accounted for nearly half of all FDI entering Guangdong province, and by 2005, the manufacturing sector accounted for 53 percent of Shenzhen’s GDP.

But Shenzhen’s transformation was just beginning. Following a 2006 government decision to promote high-tech industries and indigenous innovation in Shenzhen, investment in research and development there soared, from 3.3 percent of GDP in 2007 to 5.8 percent of GDP last year. That is even higher than the 5.6 percent reported in Israel – the country with the world’s highest R&D spending, relative to GDP.

Beyond R&D, Shenzhen invested heavily in building up its human capital. Leveraging its proximity to Hong Kong – with all the capital, talent, and market access it provided – Shenzhen developed an open, inclusive, and dynamic local innovation and business culture that appealed to talent from elsewhere in China and from abroad. Of Shenzhen’s 17.8 million permanent residents, more than 65 percent hail from outside the city.

Shenzhen also created a thriving local research ecosystem. Taking inspiration from Silicon Valley – which has nearby universities like Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley, to deliver a constant supply of top talent and cutting-edge research – Shenzhen offered world-class Chinese universities land and grants to establish local bases. Peking University, Tsinghua University, and the Chinese University of Hong Kong all have campuses in Shenzhen, and up to half of their students remain in the city to work after graduation.

Shenzhen had another key strength: a deep pool of manufacturers with the resources and capacity to build prototypes – crucial for testing the viability of new ideas or inventions. This helped to attract innovative firms, including Huawei (now valued at 128 billion US dollars), China Merchants Bank (with a market capitalization of 111.4 billion US dollars), and Ping An Financial Group, BYD, and Tencent, valued at 97.2 billion, 92.5 billion, and 443.74 billion US dollars respectively.

These five firms today rank among the top 20 companies in the country, by market value. And their promise is hardly exhausted. Consider Tencent, the world’s largest video-game publisher, the owner of the world’s top-grossing mobile game, and the developer and operator of WeChat, China’s largest and most innovative social-media platform. Tencent is also a leading venture-capital firm that has acquired or invested in more than 800 companies, both foreign and domestic. By taking stakes in innovative technology companies, from Tesla to Enflame and Zhipu (the artificial-intelligence chip startups), Tencent has established a foothold in the AI sector. In 2020, the firm announced that it would invest 70 billion US dollars in cloud computing, AI, and blockchain technology.

Beyond these established giants, Shenzhen is home to around 30 “unicorns” (unlisted companies founded after 2000 with a valuation of more than 1 billion US dollars) – almost as many as the world’s fifth-ranked country, Germany (36). One of them, the digital bank WeBank, ranks among the ten most valuable unicorns globally. It should thus not be surprising that Shenzhen boasts China’s second-largest stock market, with a total market capitalization of 4.29 trillion US dollars – larger than that of Hong Kong – and an electronic trading turnover of 1.39 trillion US dollars.

There is reason to think that Shenzhen’s economic future will be bright: its annual GDP growth, at 6 percent, outpaces that of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. But to maintain its growth and dynamism, Shenzhen will have to adapt to a rapidly changing global economic landscape, characterized by the proliferation of geopolitically motivated sanctions targeting China, especially its tech sector.

Effective adaptation is certainly possible. BYD, a world-leading electric-vehicle producer, is facing high tariffs from the United States and Europe, but it is still managing to make inroads into global markets with its cutting-edge battery technology. Huawei has weathered harsh US sanctions partly by building its own microchips and operating systems. The richness, flexibility, and business-friendly character of Shenzhen’s innovation ecosystem will enable more firms there to adapt to the challenges they face.

It helps that Shenzhen is situated within the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area, an integrated economic zone comprising nine cities and two special administrative regions. Cooperation with neighboring cities has enabled Shenzhen to deepen its links with the Global South. But now Shenzhen’s resilience as a leading manufacturing and innovation hub is facing its severest test, and its ability to make the most of these links will go a long way toward determining whether it passes.

Andrew Sheng is a distinguished fellow at the Asia Global Institute at the University of Hong Kong. Xiao Geng, Chairman of the Hong Kong Institution for International Finance, is a professor and Director of the Institute of Policy and Practice at the Shenzhen Finance Institute at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2024.

Jana Brokate has been Project Lead ChiKoN at Kiel University since June. ChiKoN, a funding measure supported by the BMBF, stands for “China Competence in the North.” Brokate lived in Beijing and Guangzhou for more than five years and worked as a project manager for AHK China, among other companies.

Shannon Ahuja has been Lead Customer Experience & Digital Ecosystem at VW China since June. For her new position, she is moving from Wolfsburg, where she most recently worked as Head of Customer Insights for the car manufacturer, to the Board Customer Committees and UX Strategy office in Beijing.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

“Are you giving me money? No? Then don’t bother me!” A young man hurled these words at an elderly passenger in the Shenyang subway after he had asked for his seat. A video of the visibly enraged passenger immediately went viral on China’s social media. Videos from Wuhan and Beijing also soon circulated, showing the clash of generations on the subway. These incidents sparked heated discussions in China, a country where respect for the elderly is traditionally held in high regard. In an online survey conducted by Sina News, over 93 percent of respondents said they did not feel obliged to give up their seats. They said that China’s young population is so overworked that it should be up to each person to decide whether they still have the strength to offer their seat out of politeness.