The “wolf-like nature” of the enemy makes it easy to fight them “bitterly and bloody”. When commonly used expressions degrade entire groups of people and incite hatred against them, they embed themselves in people’s minds. In today’s column, Johnny Erling warns about China’s ossified friend-foe speech. Propaganda introduced them under Mao and never adjusted them. In times of international strife, it’s a dangerous idea to label supposed enemies as animals and to leave no room for self-doubt. But China’s diplomats rather believe in the West’s “anti-Chinese chorus” than question the toxic terminology in their own country.

What does China hear about the war in Ukraine? On Tuesday, we already analyzed the picture painted by Chinese media. In today’s issue, Amelie Richter describes which reporters are traveling in Ukraine for China’s private and state channels and what drives them. Of course, there is no such thing as an objective portrayal of the war. This makes it all the more important to understand what interpretation of events is taking root in China. And this is also vital for assessing Beijing’s possible role in ending the invasion.

Meanwhile, the economic fallout continues to spread. In two other articles, we look at the growing disruptions to railway connections and the fear of Chinese companies of US sanctions. Julia Fiedler asked logistics experts if the Silk Road trains continue to roll. They do. But problems arise elsewhere. Insurers could cause problems if precious cargo travels through sanctioned Russian territory. The consequence: canceled freight transports.

The indirect effect of sanctions is also causing headaches for major Chinese corporations. They hesitate to fill the gap left by the withdrawal of Western companies, our Beijing team analyzes. The arrest of Huawei’s chief financial officer in connection with Iran sanctions has already shown the leverage the USA wields. And the entirety of Russia is economically weaker than some Chinese provinces. The anti-Putin alliance, on the other hand, dominates the global market.

The “Iron Silk Road” has long since become more than a romantic idea, it has become a reality in cargo transport between China and Europe. The pandemic even brought a real boom to rail transport. In 2021, goods worth almost €70 billion were transported from East to West by rail – 50 percent more than in 2020, and ten times as much as in 2016. The containers mainly contain machine parts, electronics, and other goods such as metal products, chemical products and clothing.

But the war in Ukraine has called the reliability of rail lines into question. So far, the problem is not so much the conflicts themselves. After all, the usual routes do not run through Ukraine anyway. Instead, the main concern is legal matters, such as sanctions and insurance coverage. “It wouldn’t be a surprise if companies that wanted to ship their goods by rail before the invasion now switched to the slower but more reliable sea route,” says Jacob Gunter, an economist at research institute Merics. Gunter sees uncertainty stemming from a rapidly changing geopolitical environment as a significant risk to rail transport. This, he says, will exacerbate supply chain problems, as many transport operations have recently shifted to rail.

The effects are already being felt in practice. Although trains have been running reliably so far, some companies are canceling their bookings for rail shipments, reports a spokesman for German port operator Duisburger Hafen AG. Its port is the second most important terminal for the Germany-China freight train connection after Hamburg. A common fear among companies is said to be that international insurers could cancel insurance coverage provided by Belarus and Russia, the spokesman said.

Sanctions are also a concern, according to the port company. At present, the sanctions against Russia are not overly impacting rail transport. However, uncertainty is growing among companies. The broader sanctions become, the more likely transports will be viewed with suspicion.

The concern about the effects of the sanctions is understandable. After all, shipments to Russia and Belarus have long been affected by the punitive measures imposed by Western countries. On the way from China to Germany, a large part of the most heavily frequented northern route passes right through Russia and from there via Belarus to Poland. Logistics company DHL now reports that train transports to both sanctioned countries have been suspended until further notice.

As a consequence, transit traffic is currently running from China to Europe and vice versa, while trains destined for major transit countries are suspended. A troubling situation. The German Freight Forwarding and Logistics Association (DSLV) notes that for this reason, more and more companies are searching for alternatives to the northern route. Companies are particularly interested in the southern route of the Silk Road to Turkey, which does not pass through Russian territory. However, this route to Germany takes much longer, as it includes ship transit. The logistics association expects a steady decline in transport. However, the situation is still very dynamic and can change at any time.

Even now, some companies continue to rely on transport by rail, but are closely monitoring the situation. Automotive supplier Conti has established various crisis teams to be able to quickly and accurately respond to any potential impacts on its supply chains. Corresponding contingency plans are said to be in place, which includes safety stocks and alternative suppliers. The aim is to help secure the supply of raw materials.

Rail transport has never been without problems: On the one hand, different track gauges slow down the speed. At border crossings, it can also come to a standstill, causing backlogs. At the China-Kazakhstan border, for example, there were delays of six days due to Covid measures. At the border with Mongolia, on the other hand, weak infrastructure is slowing things down, and at the border with Russia, a lack of carriages and resources on the part of the Russian railroads is preventing unimpeded travel. On top of that, there are political problems in countries along the route. Most recently, unrest in Kazakhstan in January was a factor of uncertainty for companies using this transport route. Company sources also report that corruption plays a role. High-priced goods are reported to have been lost on the way to China, which has contributed to a decision not to use rail.

As a result, more than 90 percent of Chinese goods coming to Europe are transported by ship. Overall, rail plays only a minor role in the movement of goods between China and Europe. In terms of volume, it only accounts for one percent. When considering the value of goods, it is at least three percent.

But especially for valuable goods such as electronic parts for cars, rail has firmly established itself as a mode of transport. The average speed is 32 kilometers per hour: That is still significantly faster than the sea route, and much cheaper than air cargo. “Rail has also become the fastest option for logistics because much of the air freight that is normally added to passenger flights between China and Europe came to a halt when China effectively closed its borders in early 2020,” says Merics economist Gunter.

However, rail is also politically relevant, especially for China. The extensive rail network of the new Silk Road, which connects China and Europe, is only a small part of the Belt and Road Initiative. But it is particularly important, as is evident by the large subsidies that flow to it. Xi Jinping’s prestige project is certainly impressive: A freight train now runs from China to Europe every 30 minutes. So far, more than 50,000 trips have been made. There are 78 connections to 180 cities located in 23 European countries. In addition to the transport of goods, building relationships and economic influence in partner countries play a major role.

The problems now arising on and along this route are tarnishing not only the positive image of reliable rail, but also future prospects of partnerships in Eastern Europe. “Beijing has warmed up relations with Kyiv somewhat in 2021, and the Presidents Zelenskyy and Xi have discussed the possibility of making Ukraine a ‘gateway to Europe’,” Gunter explains. ” China wanted to create an alternative rail entry point to the EU through Ukraine.” The goal was, among other things, to reduce dependence on Belarus and Lithuania. The small country had drawn Beijing’s anger by warming up to Taiwan (China.Table reported).

The Russian invasion, of course, has put these plans on hold. Xi’s joint declaration with Putin in February 2022, in which he declared a friendship with “no limits”, renders any cooperation between Kyiv and Beijing impossible for the time being. Should China downright rush to Russia’s aid, resuming projects would become even more difficult, Gunter believes. Julia Fiedler

Russia’s war in Ukraine is a constant topic in the German media. The situation is very different in China. There, the war plays a much smaller role in the media. The video footage and images shown there are strictly curated. There are only a few reports from Chinese journalists on the ground. In addition, journalists must adhere to strict rules.

There are certain guidelines for their reporting, a journalist told China.Table. Terms such as “invasion” are not allowed to be used. The 33-year-old works in Europe for Chinese media. Her work has also taken her to the border to Poland, where she reported about the situation of Ukrainian refugees. “Too much empathy and too much suffering of the people who fled are not really supposed to be shown,” she said about the reports in Chinese state media. She expressed surprise that she was told to do so many reports on refugees while she was at the border, and that she was sometimes allowed to report in a way that she would describe as “critical of Putin”.

“There are reports about how bad the situation is,” the journalist emphasizes. Many in China now get their information not only from state TV stations or newspapers, but also from social media or blogs run by freelance journalists. Naturally, all information is heavily controlled and censored, but the people are well aware of what is happening in Ukraine, believes the journalist, who has lived in Germany for several years.

Chinese journalists rarely share reports or pictures of their work in the war zone on social media. This makes the field report of Xinhua correspondent Lu Jinbo so special. According to Lu, on the evening of February 24, she was driving from Minsk in Belarus toward Kyiv to support a colleague there. He wrote a report for the state news agency about the grueling journey through the border area with blown-up bridges and other obstacles.

In the days following the launch of the Russian attack, various video footage by Lu in the Ukrainian capital appeared online. In one self-filmed sequence, he reports on a “special military operation” by Russia. The video was broadcast by Xinhua. Pictures of metro stations in Kyiv, where people are taking shelter, were also taken by Lu. Regarding the first round of negotiations between Ukraine and Russia in the border area to Belarus, the news agency published photos which, according to the author’s identification, were also shot by Lu.

The case of Chinese reporter Lu Yuguang also caused a stir among media professionals at the start of the war. Yuguang is a Moscow correspondent for the Chinese TV station Phoenix. A video posted on Weibo showed Lu with the Russian military as early as February 22 in southern Russia, a few kilometers from the border with Luhansk. In a live broadcast on February 24, the reporter can be seen with Chinese students at the Russian-Ukrainian border.

On March 2, Lu also interviewed Russian officer Denis Pushilin, head of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic,” about the progress of Russian “demilitarization” on the ground. In the videos, contrary to usual practice, the Chinese journalist does not wear any protective gear with clear press identification, instead, he also wears beige clothing. In contrast, in a video aired on March 6, Lu is wearing military protective gear. According to his own statements, he is in the heavily contested city of Mariupol.

It is unclear whether Lu is traveling with the Russian forces, meaning that he is “embedded”, in journalistic jargon. However, his reports so far suggest that he indeed is. Moreover, Lu himself is a former military man and is said to maintain close ties to the Russian army. He has already reported on both Chechen wars and has lived in Moscow for years. The fact that Lu is the only reporter to have this kind of close access to Russian soldiers led observers to speculate whether Beijing had been informed in advance about the Russian plans. However, there is no proof of this.

Aljoša Milenković, a correspondent for the Chinese international channel CGTN, was also given access to the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic”. In a car bearing the “Z” painted on its windows as a symbol of support for the invasion, he is taken to a village outside the city of Donetsk to join humanitarian relief efforts. He notes that signs are “still” in Ukrainian and people are using Ukrainian currency to pay for their bread – while the flag of the “DPR” (“Donetsk People’s Republic”) is already flying in front of the local school. Milenkovic reports of a large military presence in the region. These are said to be soldiers of the DPR; he has not seen “one Russian soldier”.

It can only be assumed that correspondents in the Russian-controlled region are more “welcome” because their reporting is pro-Russian. For some Western media, on the other hand, even reporting from Russia became increasingly difficult: Because of the new Russian law on “fake news,” German broadcasters ARD and ZDF had decided to temporarily suspend reporting from Moscow.

For Chinese correspondents, the Russian amendment to prevent the use of the words “war” and “invasion” was not a problem, estimates David Bandurski, who analyzes Chinese news reporting for the Chinese Media Project at the University of Hong Kong. “The journalists who are in Russia are almost certainly working for state media and are welcome in Moscow,” Badurski said. He believes they receive their information solely from Russian sources such as the news agency TASS, Russia Today, Sputnik and directly from the Russian government.

Badurski points to reports by state broadcaster CCTV that reflect a strictly pro-Russian narrative and portray Ukraine, along with NATO, as the aggressor. As an example, he cites a report by CCTV Moscow correspondent Yang Chun on the current situation. “It is based solely on information from the Russian government and uses archival footage.” He says this is a very typical example of reports currently being produced by Russia for broadcasters in the People’s Republic. Chinese state media would not actively report in any way. Instead, they adopt information from preferred agencies.

The fact that numerous US companies are withdrawing from Russia is good news for Chinese tech companies, at least at first glance. Russia not only connects the West and the East geographically. In recent years, it has also always been a country where Chinese companies successfully competed with Western companies. Now that the Americans are pulling out, the market share of Chinese suppliers will undoubtedly increase.

Chinese smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi, already second on the Russian sales rankings behind Samsung, is likely to benefit from the fact that Apple, previously number three in Russia, no longer plans to sell its products there. And after HP led the Russian computer business last year, Chinese group Lenovo, previously in second, is now likely to take the lead. US competitor Dell has ultimately also left Russia.

Still, Chinese companies are not quite celebrating the sudden withdrawal of American and European brands. “Russia’s entire economy is smaller than that of some Chinese provinces. Plus, its economy is crashing right now. People will buy less overall. I don’t see any profit for us there,” says an employee of a large tech company in Shenzhen in southern China.

It’s an assessment shared by many observers. “For most Chinese companies, Russia is just too small of a market for the business to be worth the risk of getting cut off from developed markets or being sanctioned itself,” an assessment by analyst firm Gavekal Dragonomics states.

Chinese companies know exactly what could happen to them if they were to pose as saviors of the Russian economy. Chinese tech company Huawei has already experienced firsthand what Washington is capable of once it has set its sights on a company. Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou spent years under Canadian house arrest because the US accused her of being involved in evading Iran sanctions. Huawei itself was blacklisted by Washington over alleged espionage charges and was crippled to the point where it is now barely able to produce smartphones.

Washington is clearly signaling these days that it would not hesitate to again severely punish Chinese companies. Companies that defy US sanctions on Russia could be cut off from American equipment and software needed to manufacture their products, US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo warned last week (China.Table reported). The US could severely punish any Chinese company that defies US sanctions by continuing to supply chips and other advanced technologies to Russia, Raimondo said in an interview with the New York Times.

Washington is threatening to blacklist companies like it did Huawei, should they try and circumvent the export restrictions on Russia. Raimondo has even already mentioned a potential target, Chinese chipmaker SMIC. If a company like SMIC was caught selling its chips to Russia, “we could essentially shut SMIC down because we prevent them from using our equipment and our software,” Raimondo was quoted as saying.

The Ukraine crisis will likely not provide Chinese tech companies with many opportunities. Rather, it will cause a lot of trouble for them, just like it does for Western companies. Should the crisis significantly impact the global economy, as is expected, this will not leave the already struggling Chinese economy unscathed. If consumption on the domestic market weakens, it will be a much bigger problem for Chinese companies than gaining a few market shares on a secondary market like Russia.

The Chinese state newspaper Global Times also seems to have understood these simple economic correlations in the meantime. An article that initially outlined possible opportunities for Chinese smartphone companies and carmakers in Russia has since been removed from the pro-government news website. Joern Petring/Gregor Koppenburg

US President Joe Biden and his counterpart Xi Jinping have agreed to discuss China-US relations over the phone. “The two leaders will discuss managing the competition between our two countries as well as Russia’s war against Ukraine and other issues of mutual concern,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said. The discussion is scheduled for Friday night to Saturday, Beijing time.

The call was decided on Monday in Rome during a seven-hour meeting between White House National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and top Chinese diplomat Yang Jiechi. The US insists that China will not circumvent Western sanctions on Russia, and threatened consequences for Chinese companies. Beijing, on the other hand, considers the punitive measures illegitimate. Meanwhile, Russia’s Minister of Finance announced that the country is counting on China to help it weather the impact of Western sanctions on its economy.

Biden and Xi last spoke in November. At that time, Biden stressed that the two great powers needed to establish guidelines to prevent their competition from turning into conflict. nib

Shanghai-based Envision Group has signed a battery module partnership with Mercedes-Benz for its EV production. Its subsidiary Envision AESC is to supply the batteries for all-electric SUVs EQS and EQE, which will be manufactured in the US state of Alabama. Renault, Nissan and Honda are among Envision’s customers. The Envision Group holds 80 percent of the company. Nissan owns the remaining 20 percent.

The company also announced plans for the construction of a second battery factory in the United States, without providing any details. By 2025, the company aims to reach an annual EV battery production capacity of 300 gigawatt-hours. Currently, Envision is the world’s ninth-largest battery manufacturer, with a 1.4 percent market share. Envision Group also manufactures wind turbines. nib

Tibetan singer Tsewang Norbu has succumbed to serious injuries after setting himself on fire. The International Campaign for Tibet (ICT) confirmed the death of the 25-year-old, who had set himself on fire outside the Potala Palace in Lhasa at the end of February (China.Table reported). ICT cited anonymous sources. Last week, the organization had still stated that there was no definite information whether Norbu had died.

Chinese officers had taken the critically injured man to the “People’s Hospital of the Tibet Autonomous Region,” shielded him from the public for days, and did not issue a public announcement following his death on the first weekend of March. The ICT has no information about what happened to his body.

Since 2009, 158 Tibetans have set themselves on fire in protest against the Chinese government’s occupation of the region and oppression of its people. Only about two dozen survived. grz

China’s environmental authority has reprimanded four companies for allegedly forging corporate CO2 reports. The data verification agencies had manipulated reports and falsified testing and emissions data, business portal Caixin reported. These agencies play an important role in China’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gasses by measuring and verifying companies’ CO2 emissions. This information is, in turn, important for China’s emissions trading and green finance sectors.

An industry analyst told Caixin that China’s high inspection requirements encourage CO2 fraud. Measuring emissions is said to involve high costs. As a result, companies would forge their statistics. External auditing agencies, in turn, are then forced to look closely to detect possible fraud.

Manipulation and forging of environmental inspections is not a new phenomenon in China. Last year, for example, the case of an auditor who allegedly prepared more than 1,600 environmental impact assessments in just four months came to light. However, assessing the environmental impact of construction projects, for example, is far more time-consuming. At the time, there were indications that her employer had sold the auditor’s credentials to other auditing companies, which allegedly carried out audits in her name. nib

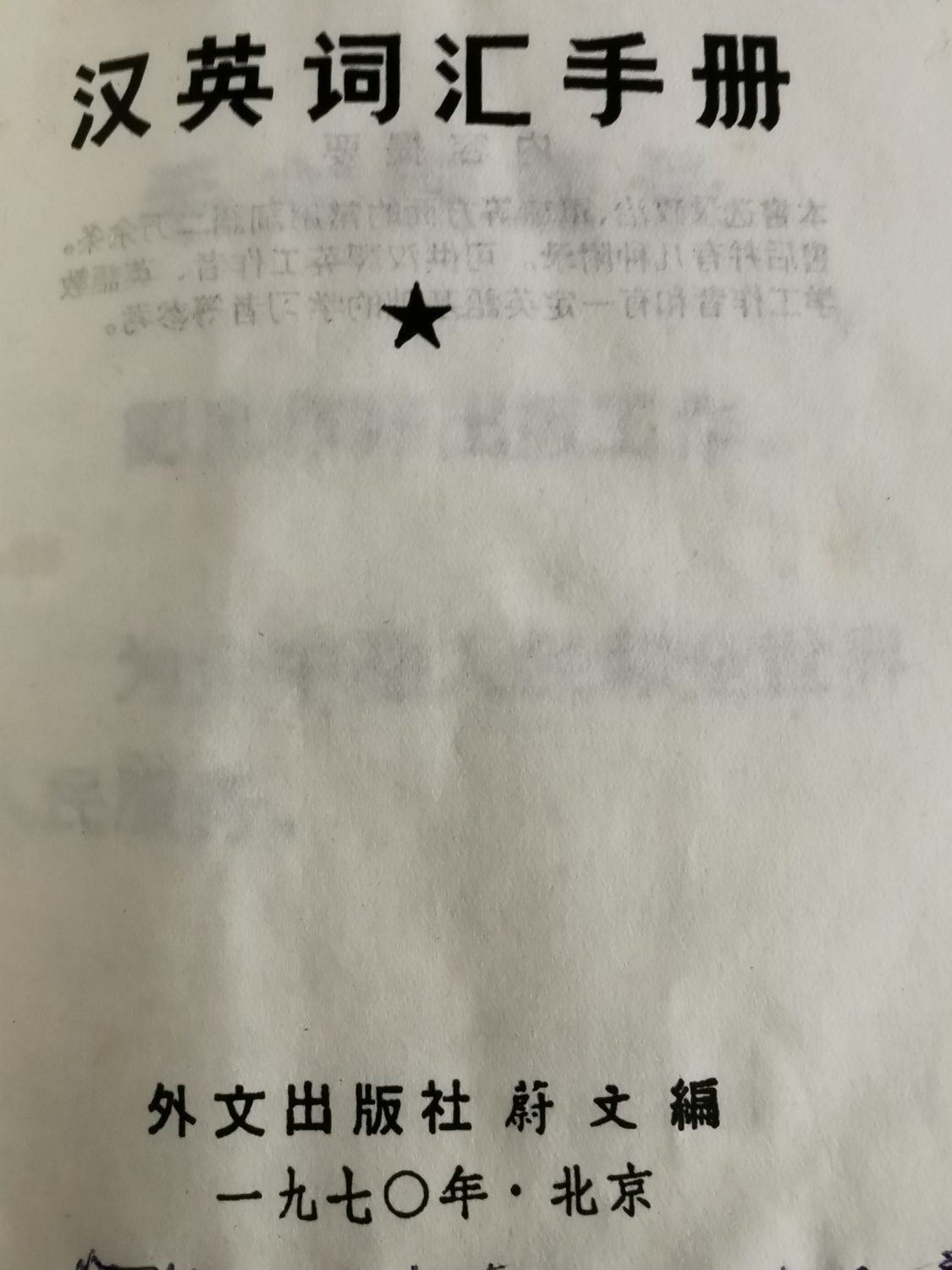

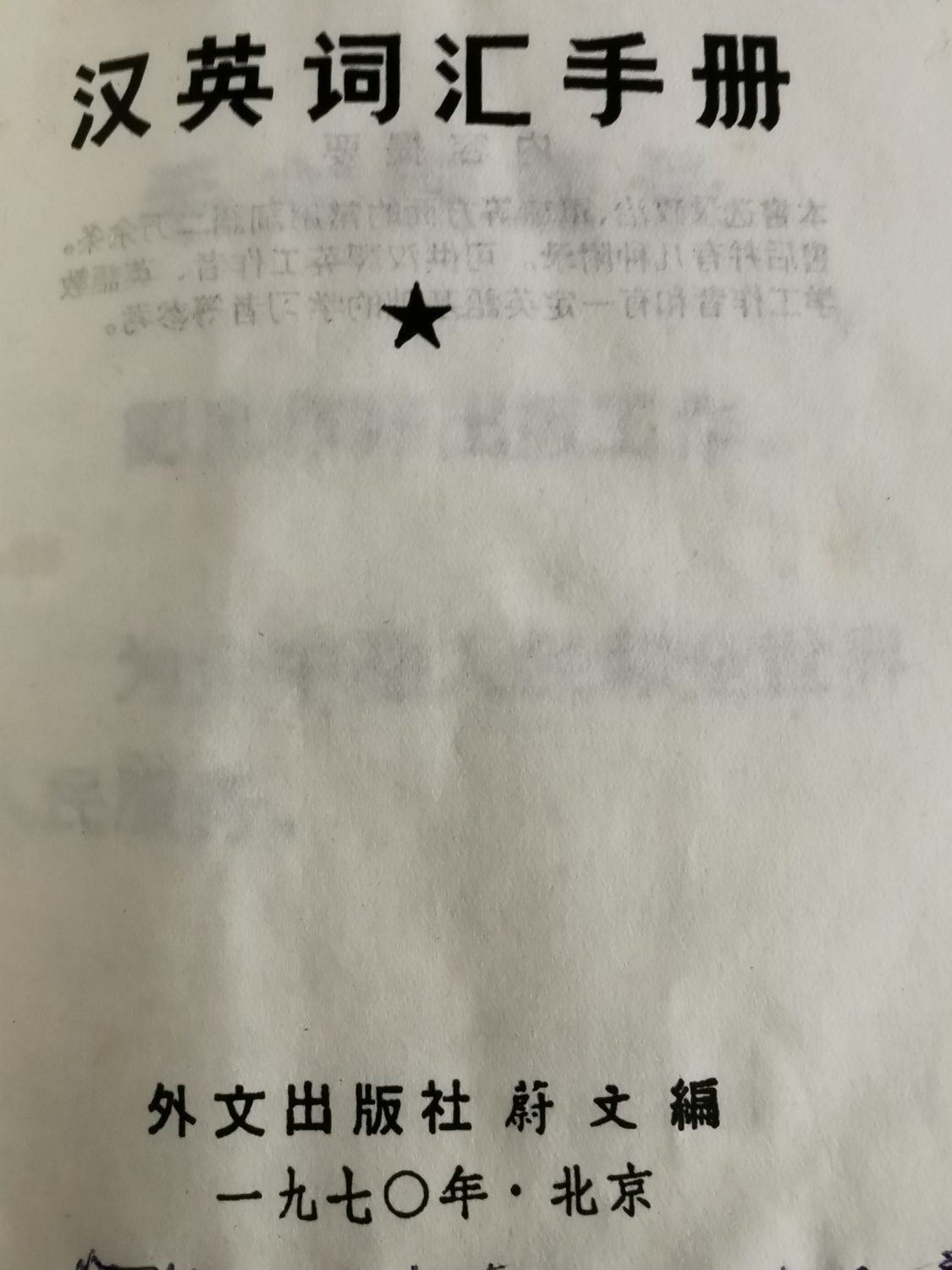

Recently, while cleaning out the basement where I stored my books that I brought back from my university years in China, I came across a “Handbook of Chinese-English Vocabulary” (汉英词汇手册). It was published in December 1970 during Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Its technical title already seemed unusual. With over 1,600 pages, the annotated dictionary became a major publishing feat. Commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Foreign Languages Press mobilized a group of language experts after the 9th Party Congress in 1969 to produce a reference guide for the self-expression of Cultural Revolutionary terminology. Beginning in January 1970, they compiled more than 20,000 expressions over eleven months, with examples of their use in ideology, politics, society, economics, and the military.

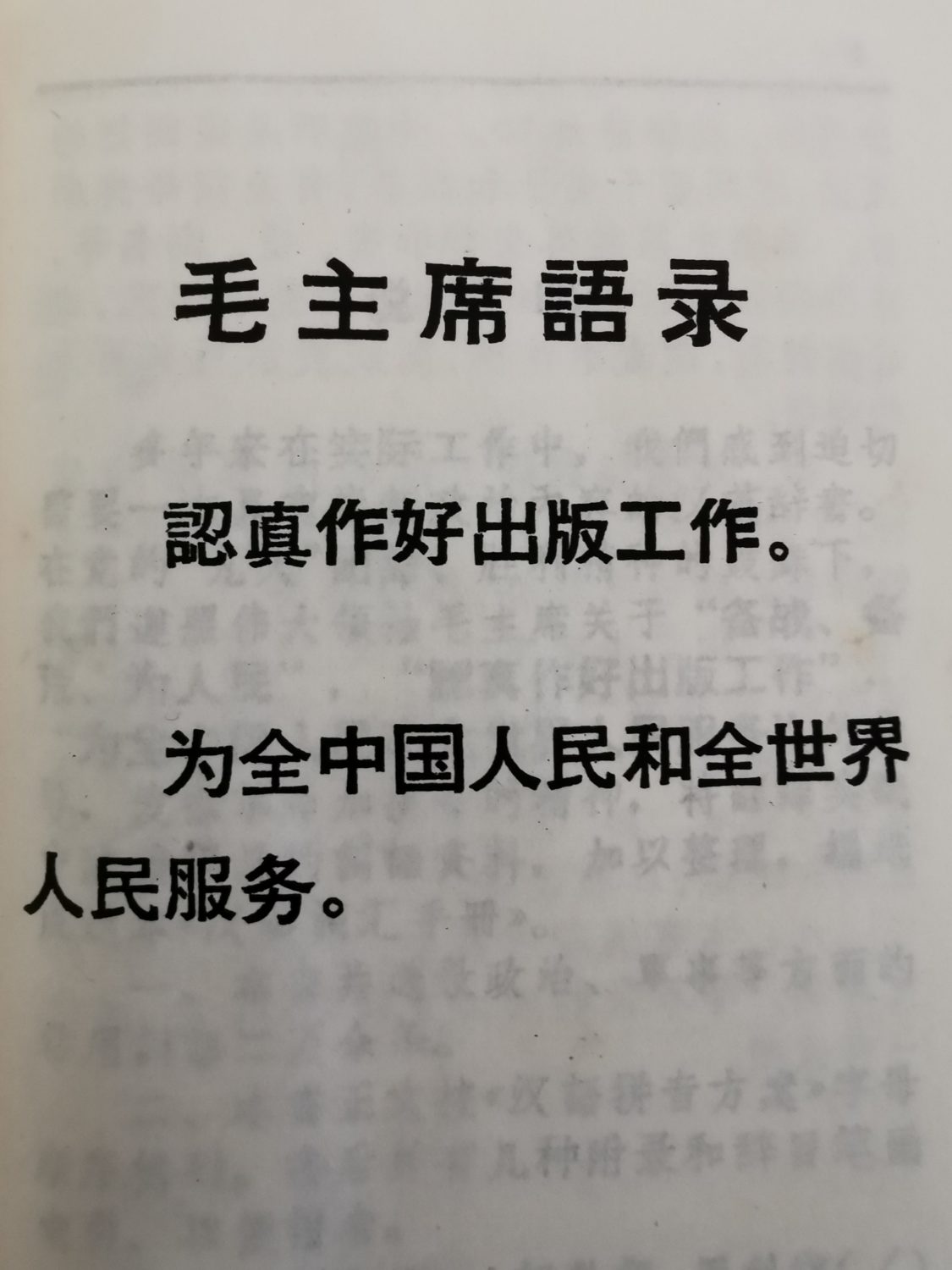

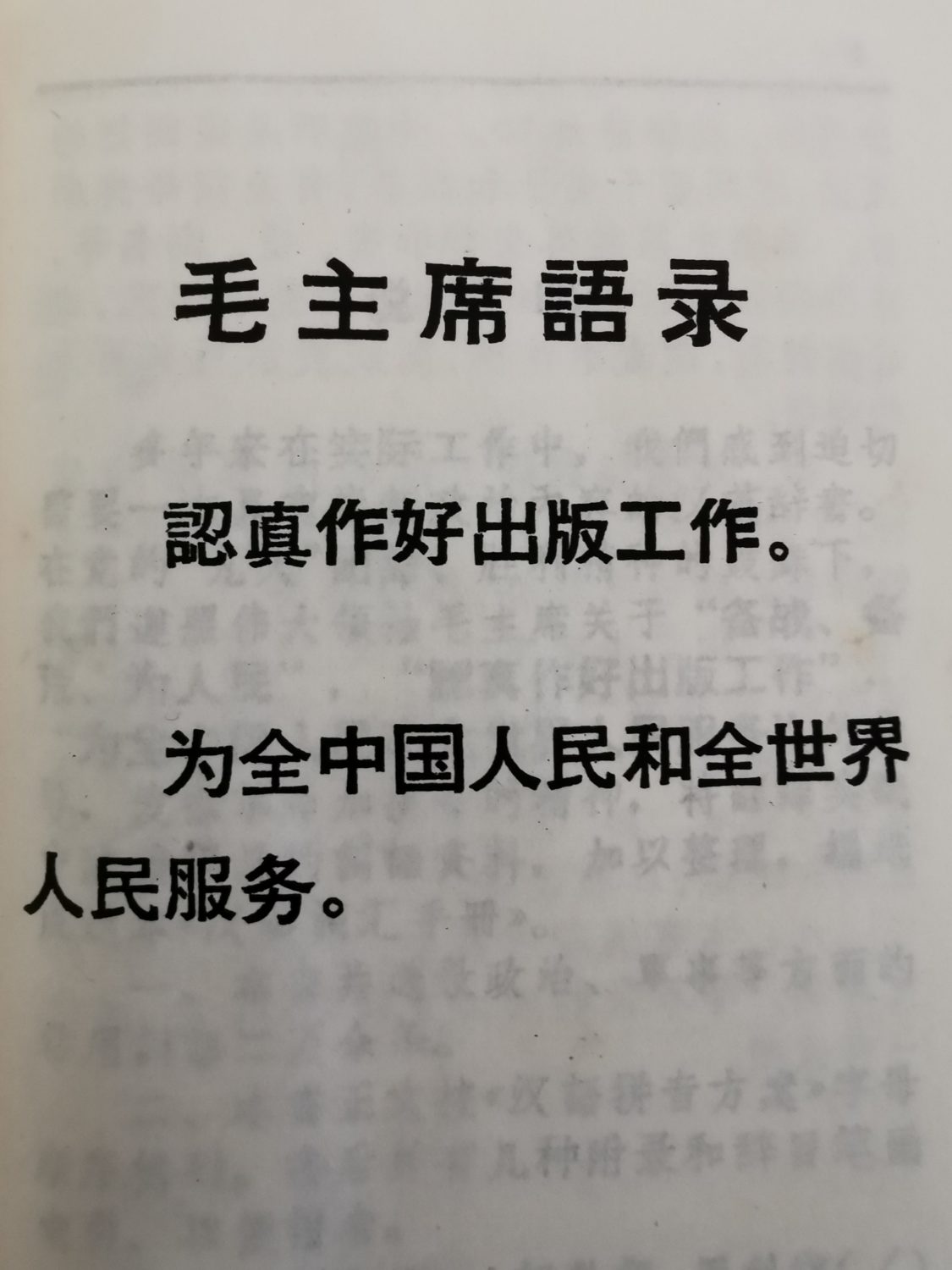

As was customary at the time, Mao slogans appeared on the first page. Instead of revolutionary calls, the Great Chairman demanded: “Do good publishing work” and “for the benefit of the Chinese people and the people of the whole world.” This was in line with Beijing’s desire to at least make foreign countries understand the terms the secluded nation was speaking and thinking in.

Because China’s leadership wanted to open its doors to the West out of fear of its enemy, the Soviet Union. In 1969, the two states had clashed for the first time at the Amur River. In early 1971, US National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger arrived in Beijing for secret negotiations.

The new dictionary was only a small signal of great change. Its hundreds of translated anti-Soviet terms reflected the deep rift with the Soviet Union. Mao’s propagandists called them “revisionist” and “social-imperialist” and their leaders “new tsars” with “Great Russian chauvinism” (大俄罗斯沙文主义). Example sentences mainly attacked Nikita Khrushchev.

Nowadays, the difference could not possibly be greater. Shortly before Moscow’s war of aggression on Ukraine, President Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin pledged a friendship with “no limits” and cooperation without “forbidden areas” in a 15-page agreement. Today’s linguistic hatred is once again directed against the USA.

The 1970 dictionary is a testimony of a bygone era. It was not reprinted after Mao’s death. Chinese under 40 who grew up in times of reform are bewildered by expressions ranging from “snake spirits and cattle devils”(牛鬼蛇神) to the “three Mao essays to be read at all times” (老三篇). Nor do they understand why, in old party jargon, rock ‘n’ roll was called the “dance of vagabonds” (阿飞舞). Instead, they are angered when Beijing’s ideologues polemically vilify their idols, fashion trends, or live streaming stars.

China’s poisoned officious language, which once spawned the grotesque word monstrosities of the Cultural Revolution, now uses different terms, but has not changed its nature. Even though the Cultural Revolution took inhumanity and hatred to extremes, the language has remained full of malice and polemics against opponents or dissidents. This also affects social media. A debate among expatriate Chinese in the US wonders why Chinese shitstorms exceed the Internet rage of other nations. This phenomenon also manifests in the aggression and absurd conspiracy theories of the so-called “wolf warriors” of the Foreign Ministry, who have abandoned any diplomatic restraint or courtesy and denounce any critical voices as an “anti-Chinese chorus” (反华大合唱), a term also present in the 1970 manual.

Cantonese reform philosopher Yuan Weishi (袁伟时) blames the ideologized school education in the People’s Republic, which he called “being raised with wolf milk”. China’s communists have manipulated both language and education to ideologically “brainwash” and ideologize society since the beginning of their rule, writes Yu Jie, an author and dissident now living in exile in the United States. He cites the linguistic research of analyst and novelist Victor Klemperer. He warned not to ignore the critical role that language plays in the creation of a totalitarian system.

But language serves this purpose in China. This is also the logic behind the ideological speeches of autocrat Xi Jinping, writes Yu in his study “From Maoism to Xiism.” Since Mao’s death, none of China’s leaders has quoted the Great Chairman as often as Xi.

Xi not only uses Mao’s language to expand his cult of personality and power, but also copies his methods. The chairman introduced “classes for Mao Zedong thought” (办毛泽东思想学习班), a term that appears in the 1970s dictionary. Xi now forces China’s ministries and commissions to run “Research Centers on Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想研究中心). Even his recent catchphrase: “The East is rising and West is declining” (东升西降) echoes Mao slogans: “the sun rises in the east – and sets in the west” (东方日盛,西方日衰), or “the east wind prevails over west wind” (东风压倒西风).

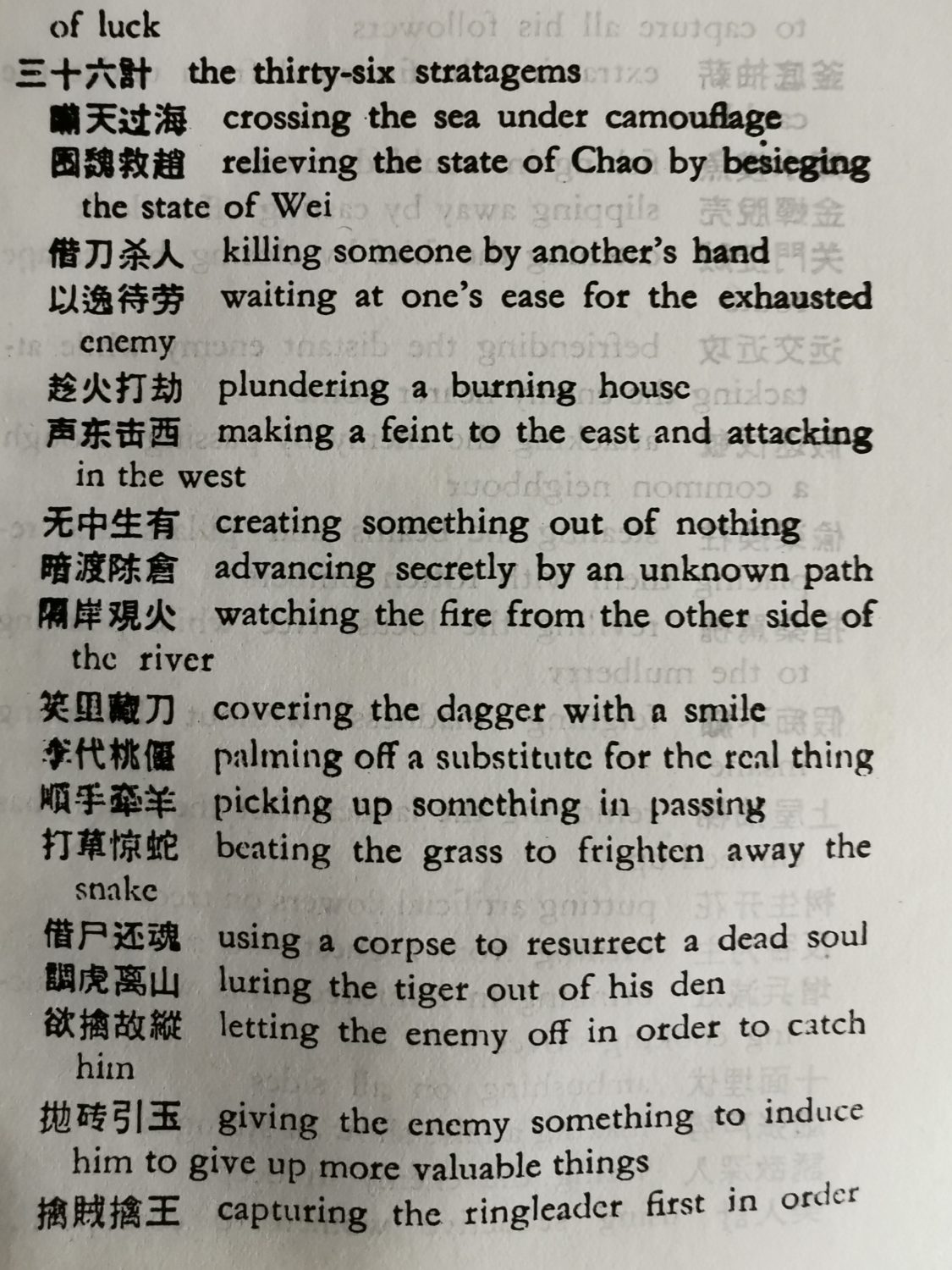

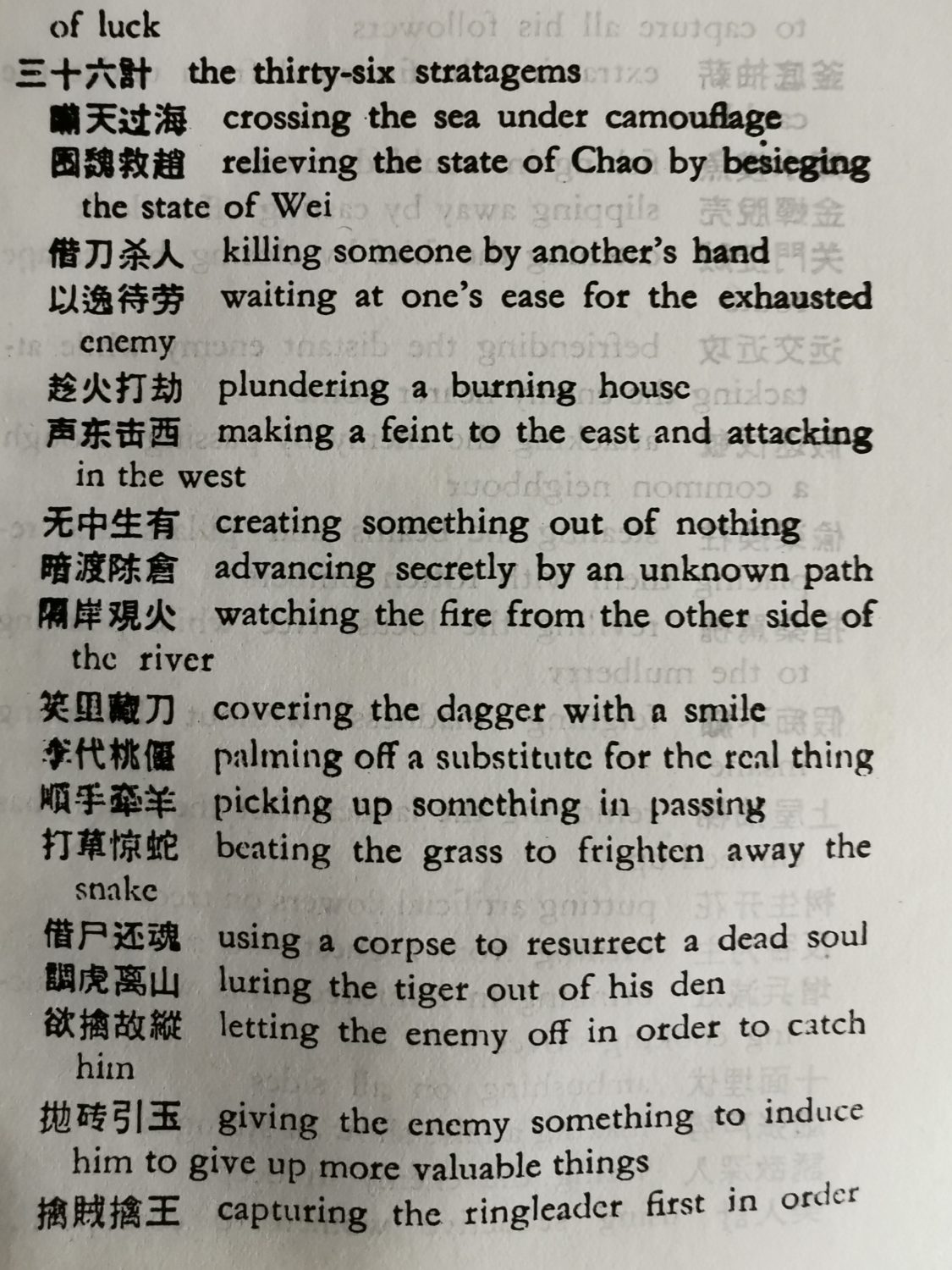

The 1970 dictionary first revealed the concept of the ancient Chinese Thirty-Six Stratagems (三十六计) to the outside world, which had been handed down for 3,000 years. Mao used them to conquer China and later assert his power. The reference book lists all 36 intrigues individually with English translation. It even reveals which stratagem was the most effective in guerrilla warfare: “Of the Thirty-Six Stratagems, fleeing is best” ( 三十六计走为上计).

Harro von Senger, a renowned sinologist and former professor of Chinese law who now lives in Switzerland and who also studied in Beijing during the mid-1970s, told me that he first found the word “stratagems” as a term for the life and survival lists in the 1970 dictionary. He has since written dozens of essays and translations on the Thirty-Six Stratagems, which have been published in 16 languages, most recently in January 2022 by a Ukrainian publishing house.

Reforms and modernization radically changed China overnight. In 2002, a series of books almost nostalgically recalled the hundreds of crafts that quietly disappeared in less than a generation along with their names. Gone were they – the scissors and knife grinder (磨刀人) who roamed the residential neighborhoods with loud chanting, the letter writer for others (代写书信), the briquette seller (卖炭) or feng shui geomancer (风水先生).

Everything changed, except China’s language. The need for reform was voiced by authors such as Ye Yanbing (叶延滨) in 2007. He called in vain for creating a dictionary on the inhumane language of the Cultural Revolution (文革说文解字), based on the classical explanatory encyclopedia for terms in ancient China.

Michael Kahn-Ackermann, a translator and the former director of the Beijing Goethe-Institut, says that there has never been a reappraisal of the contemporary literary language of Baihua (白话), which has existed for 100 years, much less “liberating a language that has become increasingly stereotyped since 1949.”

This issue haunted Chinese intellectuals after the end of the Cultural Revolution, says Kahn-Ackermann. A Cheng (阿城), for example, is still fighting for a humane language. Yu Hua (余华) addressed this in his book “China in Ten Words“. Others, such as the satirist Wang Shuo 王朔, tried to detoxify the official language through ironization.

If you flip through the 1970 dictionary, you will be shocked by the countless inhuman expressions that are used to this day, of the ” wolf-like nature” of the enemy (豺狼本性) who must be fought “bitterly and bloodily” (残酷的流血斗争).

The recent re-ideologization is further encrusting China’s language and thinking. How this will fit in with the modern superpower that China aspires to be is the same question that many other areas of China face, such as how innovation and initiative are to thrive under ever-stricter surveillance, control, and censorship. The answer is still missing.

Hans-Peter Friedrich will become the head of the German-Chinese parliamentary group, reports the Berlin website “The Pioneer”. Friedrich is a renowned expert on China and co-founder of the China-Brücke (China Bridge). He served as Vice President of the German Bundestag until the change of government.

Gary Liu, previously head of the South China Morning Post owned by Alibaba Group, is to lead an Alibaba start-up for the management of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). The group is thus looking for a new CEO for SCMP.

Cherry blossoms against a mountain panorama – the cherry orchard in the Guian New Area (Guizhou Province) is a tourist magnet with many charms.

The “wolf-like nature” of the enemy makes it easy to fight them “bitterly and bloody”. When commonly used expressions degrade entire groups of people and incite hatred against them, they embed themselves in people’s minds. In today’s column, Johnny Erling warns about China’s ossified friend-foe speech. Propaganda introduced them under Mao and never adjusted them. In times of international strife, it’s a dangerous idea to label supposed enemies as animals and to leave no room for self-doubt. But China’s diplomats rather believe in the West’s “anti-Chinese chorus” than question the toxic terminology in their own country.

What does China hear about the war in Ukraine? On Tuesday, we already analyzed the picture painted by Chinese media. In today’s issue, Amelie Richter describes which reporters are traveling in Ukraine for China’s private and state channels and what drives them. Of course, there is no such thing as an objective portrayal of the war. This makes it all the more important to understand what interpretation of events is taking root in China. And this is also vital for assessing Beijing’s possible role in ending the invasion.

Meanwhile, the economic fallout continues to spread. In two other articles, we look at the growing disruptions to railway connections and the fear of Chinese companies of US sanctions. Julia Fiedler asked logistics experts if the Silk Road trains continue to roll. They do. But problems arise elsewhere. Insurers could cause problems if precious cargo travels through sanctioned Russian territory. The consequence: canceled freight transports.

The indirect effect of sanctions is also causing headaches for major Chinese corporations. They hesitate to fill the gap left by the withdrawal of Western companies, our Beijing team analyzes. The arrest of Huawei’s chief financial officer in connection with Iran sanctions has already shown the leverage the USA wields. And the entirety of Russia is economically weaker than some Chinese provinces. The anti-Putin alliance, on the other hand, dominates the global market.

The “Iron Silk Road” has long since become more than a romantic idea, it has become a reality in cargo transport between China and Europe. The pandemic even brought a real boom to rail transport. In 2021, goods worth almost €70 billion were transported from East to West by rail – 50 percent more than in 2020, and ten times as much as in 2016. The containers mainly contain machine parts, electronics, and other goods such as metal products, chemical products and clothing.

But the war in Ukraine has called the reliability of rail lines into question. So far, the problem is not so much the conflicts themselves. After all, the usual routes do not run through Ukraine anyway. Instead, the main concern is legal matters, such as sanctions and insurance coverage. “It wouldn’t be a surprise if companies that wanted to ship their goods by rail before the invasion now switched to the slower but more reliable sea route,” says Jacob Gunter, an economist at research institute Merics. Gunter sees uncertainty stemming from a rapidly changing geopolitical environment as a significant risk to rail transport. This, he says, will exacerbate supply chain problems, as many transport operations have recently shifted to rail.

The effects are already being felt in practice. Although trains have been running reliably so far, some companies are canceling their bookings for rail shipments, reports a spokesman for German port operator Duisburger Hafen AG. Its port is the second most important terminal for the Germany-China freight train connection after Hamburg. A common fear among companies is said to be that international insurers could cancel insurance coverage provided by Belarus and Russia, the spokesman said.

Sanctions are also a concern, according to the port company. At present, the sanctions against Russia are not overly impacting rail transport. However, uncertainty is growing among companies. The broader sanctions become, the more likely transports will be viewed with suspicion.

The concern about the effects of the sanctions is understandable. After all, shipments to Russia and Belarus have long been affected by the punitive measures imposed by Western countries. On the way from China to Germany, a large part of the most heavily frequented northern route passes right through Russia and from there via Belarus to Poland. Logistics company DHL now reports that train transports to both sanctioned countries have been suspended until further notice.

As a consequence, transit traffic is currently running from China to Europe and vice versa, while trains destined for major transit countries are suspended. A troubling situation. The German Freight Forwarding and Logistics Association (DSLV) notes that for this reason, more and more companies are searching for alternatives to the northern route. Companies are particularly interested in the southern route of the Silk Road to Turkey, which does not pass through Russian territory. However, this route to Germany takes much longer, as it includes ship transit. The logistics association expects a steady decline in transport. However, the situation is still very dynamic and can change at any time.

Even now, some companies continue to rely on transport by rail, but are closely monitoring the situation. Automotive supplier Conti has established various crisis teams to be able to quickly and accurately respond to any potential impacts on its supply chains. Corresponding contingency plans are said to be in place, which includes safety stocks and alternative suppliers. The aim is to help secure the supply of raw materials.

Rail transport has never been without problems: On the one hand, different track gauges slow down the speed. At border crossings, it can also come to a standstill, causing backlogs. At the China-Kazakhstan border, for example, there were delays of six days due to Covid measures. At the border with Mongolia, on the other hand, weak infrastructure is slowing things down, and at the border with Russia, a lack of carriages and resources on the part of the Russian railroads is preventing unimpeded travel. On top of that, there are political problems in countries along the route. Most recently, unrest in Kazakhstan in January was a factor of uncertainty for companies using this transport route. Company sources also report that corruption plays a role. High-priced goods are reported to have been lost on the way to China, which has contributed to a decision not to use rail.

As a result, more than 90 percent of Chinese goods coming to Europe are transported by ship. Overall, rail plays only a minor role in the movement of goods between China and Europe. In terms of volume, it only accounts for one percent. When considering the value of goods, it is at least three percent.

But especially for valuable goods such as electronic parts for cars, rail has firmly established itself as a mode of transport. The average speed is 32 kilometers per hour: That is still significantly faster than the sea route, and much cheaper than air cargo. “Rail has also become the fastest option for logistics because much of the air freight that is normally added to passenger flights between China and Europe came to a halt when China effectively closed its borders in early 2020,” says Merics economist Gunter.

However, rail is also politically relevant, especially for China. The extensive rail network of the new Silk Road, which connects China and Europe, is only a small part of the Belt and Road Initiative. But it is particularly important, as is evident by the large subsidies that flow to it. Xi Jinping’s prestige project is certainly impressive: A freight train now runs from China to Europe every 30 minutes. So far, more than 50,000 trips have been made. There are 78 connections to 180 cities located in 23 European countries. In addition to the transport of goods, building relationships and economic influence in partner countries play a major role.

The problems now arising on and along this route are tarnishing not only the positive image of reliable rail, but also future prospects of partnerships in Eastern Europe. “Beijing has warmed up relations with Kyiv somewhat in 2021, and the Presidents Zelenskyy and Xi have discussed the possibility of making Ukraine a ‘gateway to Europe’,” Gunter explains. ” China wanted to create an alternative rail entry point to the EU through Ukraine.” The goal was, among other things, to reduce dependence on Belarus and Lithuania. The small country had drawn Beijing’s anger by warming up to Taiwan (China.Table reported).

The Russian invasion, of course, has put these plans on hold. Xi’s joint declaration with Putin in February 2022, in which he declared a friendship with “no limits”, renders any cooperation between Kyiv and Beijing impossible for the time being. Should China downright rush to Russia’s aid, resuming projects would become even more difficult, Gunter believes. Julia Fiedler

Russia’s war in Ukraine is a constant topic in the German media. The situation is very different in China. There, the war plays a much smaller role in the media. The video footage and images shown there are strictly curated. There are only a few reports from Chinese journalists on the ground. In addition, journalists must adhere to strict rules.

There are certain guidelines for their reporting, a journalist told China.Table. Terms such as “invasion” are not allowed to be used. The 33-year-old works in Europe for Chinese media. Her work has also taken her to the border to Poland, where she reported about the situation of Ukrainian refugees. “Too much empathy and too much suffering of the people who fled are not really supposed to be shown,” she said about the reports in Chinese state media. She expressed surprise that she was told to do so many reports on refugees while she was at the border, and that she was sometimes allowed to report in a way that she would describe as “critical of Putin”.

“There are reports about how bad the situation is,” the journalist emphasizes. Many in China now get their information not only from state TV stations or newspapers, but also from social media or blogs run by freelance journalists. Naturally, all information is heavily controlled and censored, but the people are well aware of what is happening in Ukraine, believes the journalist, who has lived in Germany for several years.

Chinese journalists rarely share reports or pictures of their work in the war zone on social media. This makes the field report of Xinhua correspondent Lu Jinbo so special. According to Lu, on the evening of February 24, she was driving from Minsk in Belarus toward Kyiv to support a colleague there. He wrote a report for the state news agency about the grueling journey through the border area with blown-up bridges and other obstacles.

In the days following the launch of the Russian attack, various video footage by Lu in the Ukrainian capital appeared online. In one self-filmed sequence, he reports on a “special military operation” by Russia. The video was broadcast by Xinhua. Pictures of metro stations in Kyiv, where people are taking shelter, were also taken by Lu. Regarding the first round of negotiations between Ukraine and Russia in the border area to Belarus, the news agency published photos which, according to the author’s identification, were also shot by Lu.

The case of Chinese reporter Lu Yuguang also caused a stir among media professionals at the start of the war. Yuguang is a Moscow correspondent for the Chinese TV station Phoenix. A video posted on Weibo showed Lu with the Russian military as early as February 22 in southern Russia, a few kilometers from the border with Luhansk. In a live broadcast on February 24, the reporter can be seen with Chinese students at the Russian-Ukrainian border.

On March 2, Lu also interviewed Russian officer Denis Pushilin, head of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic,” about the progress of Russian “demilitarization” on the ground. In the videos, contrary to usual practice, the Chinese journalist does not wear any protective gear with clear press identification, instead, he also wears beige clothing. In contrast, in a video aired on March 6, Lu is wearing military protective gear. According to his own statements, he is in the heavily contested city of Mariupol.

It is unclear whether Lu is traveling with the Russian forces, meaning that he is “embedded”, in journalistic jargon. However, his reports so far suggest that he indeed is. Moreover, Lu himself is a former military man and is said to maintain close ties to the Russian army. He has already reported on both Chechen wars and has lived in Moscow for years. The fact that Lu is the only reporter to have this kind of close access to Russian soldiers led observers to speculate whether Beijing had been informed in advance about the Russian plans. However, there is no proof of this.

Aljoša Milenković, a correspondent for the Chinese international channel CGTN, was also given access to the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic”. In a car bearing the “Z” painted on its windows as a symbol of support for the invasion, he is taken to a village outside the city of Donetsk to join humanitarian relief efforts. He notes that signs are “still” in Ukrainian and people are using Ukrainian currency to pay for their bread – while the flag of the “DPR” (“Donetsk People’s Republic”) is already flying in front of the local school. Milenkovic reports of a large military presence in the region. These are said to be soldiers of the DPR; he has not seen “one Russian soldier”.

It can only be assumed that correspondents in the Russian-controlled region are more “welcome” because their reporting is pro-Russian. For some Western media, on the other hand, even reporting from Russia became increasingly difficult: Because of the new Russian law on “fake news,” German broadcasters ARD and ZDF had decided to temporarily suspend reporting from Moscow.

For Chinese correspondents, the Russian amendment to prevent the use of the words “war” and “invasion” was not a problem, estimates David Bandurski, who analyzes Chinese news reporting for the Chinese Media Project at the University of Hong Kong. “The journalists who are in Russia are almost certainly working for state media and are welcome in Moscow,” Badurski said. He believes they receive their information solely from Russian sources such as the news agency TASS, Russia Today, Sputnik and directly from the Russian government.

Badurski points to reports by state broadcaster CCTV that reflect a strictly pro-Russian narrative and portray Ukraine, along with NATO, as the aggressor. As an example, he cites a report by CCTV Moscow correspondent Yang Chun on the current situation. “It is based solely on information from the Russian government and uses archival footage.” He says this is a very typical example of reports currently being produced by Russia for broadcasters in the People’s Republic. Chinese state media would not actively report in any way. Instead, they adopt information from preferred agencies.

The fact that numerous US companies are withdrawing from Russia is good news for Chinese tech companies, at least at first glance. Russia not only connects the West and the East geographically. In recent years, it has also always been a country where Chinese companies successfully competed with Western companies. Now that the Americans are pulling out, the market share of Chinese suppliers will undoubtedly increase.

Chinese smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi, already second on the Russian sales rankings behind Samsung, is likely to benefit from the fact that Apple, previously number three in Russia, no longer plans to sell its products there. And after HP led the Russian computer business last year, Chinese group Lenovo, previously in second, is now likely to take the lead. US competitor Dell has ultimately also left Russia.

Still, Chinese companies are not quite celebrating the sudden withdrawal of American and European brands. “Russia’s entire economy is smaller than that of some Chinese provinces. Plus, its economy is crashing right now. People will buy less overall. I don’t see any profit for us there,” says an employee of a large tech company in Shenzhen in southern China.

It’s an assessment shared by many observers. “For most Chinese companies, Russia is just too small of a market for the business to be worth the risk of getting cut off from developed markets or being sanctioned itself,” an assessment by analyst firm Gavekal Dragonomics states.

Chinese companies know exactly what could happen to them if they were to pose as saviors of the Russian economy. Chinese tech company Huawei has already experienced firsthand what Washington is capable of once it has set its sights on a company. Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou spent years under Canadian house arrest because the US accused her of being involved in evading Iran sanctions. Huawei itself was blacklisted by Washington over alleged espionage charges and was crippled to the point where it is now barely able to produce smartphones.

Washington is clearly signaling these days that it would not hesitate to again severely punish Chinese companies. Companies that defy US sanctions on Russia could be cut off from American equipment and software needed to manufacture their products, US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo warned last week (China.Table reported). The US could severely punish any Chinese company that defies US sanctions by continuing to supply chips and other advanced technologies to Russia, Raimondo said in an interview with the New York Times.

Washington is threatening to blacklist companies like it did Huawei, should they try and circumvent the export restrictions on Russia. Raimondo has even already mentioned a potential target, Chinese chipmaker SMIC. If a company like SMIC was caught selling its chips to Russia, “we could essentially shut SMIC down because we prevent them from using our equipment and our software,” Raimondo was quoted as saying.

The Ukraine crisis will likely not provide Chinese tech companies with many opportunities. Rather, it will cause a lot of trouble for them, just like it does for Western companies. Should the crisis significantly impact the global economy, as is expected, this will not leave the already struggling Chinese economy unscathed. If consumption on the domestic market weakens, it will be a much bigger problem for Chinese companies than gaining a few market shares on a secondary market like Russia.

The Chinese state newspaper Global Times also seems to have understood these simple economic correlations in the meantime. An article that initially outlined possible opportunities for Chinese smartphone companies and carmakers in Russia has since been removed from the pro-government news website. Joern Petring/Gregor Koppenburg

US President Joe Biden and his counterpart Xi Jinping have agreed to discuss China-US relations over the phone. “The two leaders will discuss managing the competition between our two countries as well as Russia’s war against Ukraine and other issues of mutual concern,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said. The discussion is scheduled for Friday night to Saturday, Beijing time.

The call was decided on Monday in Rome during a seven-hour meeting between White House National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and top Chinese diplomat Yang Jiechi. The US insists that China will not circumvent Western sanctions on Russia, and threatened consequences for Chinese companies. Beijing, on the other hand, considers the punitive measures illegitimate. Meanwhile, Russia’s Minister of Finance announced that the country is counting on China to help it weather the impact of Western sanctions on its economy.

Biden and Xi last spoke in November. At that time, Biden stressed that the two great powers needed to establish guidelines to prevent their competition from turning into conflict. nib

Shanghai-based Envision Group has signed a battery module partnership with Mercedes-Benz for its EV production. Its subsidiary Envision AESC is to supply the batteries for all-electric SUVs EQS and EQE, which will be manufactured in the US state of Alabama. Renault, Nissan and Honda are among Envision’s customers. The Envision Group holds 80 percent of the company. Nissan owns the remaining 20 percent.

The company also announced plans for the construction of a second battery factory in the United States, without providing any details. By 2025, the company aims to reach an annual EV battery production capacity of 300 gigawatt-hours. Currently, Envision is the world’s ninth-largest battery manufacturer, with a 1.4 percent market share. Envision Group also manufactures wind turbines. nib

Tibetan singer Tsewang Norbu has succumbed to serious injuries after setting himself on fire. The International Campaign for Tibet (ICT) confirmed the death of the 25-year-old, who had set himself on fire outside the Potala Palace in Lhasa at the end of February (China.Table reported). ICT cited anonymous sources. Last week, the organization had still stated that there was no definite information whether Norbu had died.

Chinese officers had taken the critically injured man to the “People’s Hospital of the Tibet Autonomous Region,” shielded him from the public for days, and did not issue a public announcement following his death on the first weekend of March. The ICT has no information about what happened to his body.

Since 2009, 158 Tibetans have set themselves on fire in protest against the Chinese government’s occupation of the region and oppression of its people. Only about two dozen survived. grz

China’s environmental authority has reprimanded four companies for allegedly forging corporate CO2 reports. The data verification agencies had manipulated reports and falsified testing and emissions data, business portal Caixin reported. These agencies play an important role in China’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gasses by measuring and verifying companies’ CO2 emissions. This information is, in turn, important for China’s emissions trading and green finance sectors.

An industry analyst told Caixin that China’s high inspection requirements encourage CO2 fraud. Measuring emissions is said to involve high costs. As a result, companies would forge their statistics. External auditing agencies, in turn, are then forced to look closely to detect possible fraud.

Manipulation and forging of environmental inspections is not a new phenomenon in China. Last year, for example, the case of an auditor who allegedly prepared more than 1,600 environmental impact assessments in just four months came to light. However, assessing the environmental impact of construction projects, for example, is far more time-consuming. At the time, there were indications that her employer had sold the auditor’s credentials to other auditing companies, which allegedly carried out audits in her name. nib

Recently, while cleaning out the basement where I stored my books that I brought back from my university years in China, I came across a “Handbook of Chinese-English Vocabulary” (汉英词汇手册). It was published in December 1970 during Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Its technical title already seemed unusual. With over 1,600 pages, the annotated dictionary became a major publishing feat. Commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Foreign Languages Press mobilized a group of language experts after the 9th Party Congress in 1969 to produce a reference guide for the self-expression of Cultural Revolutionary terminology. Beginning in January 1970, they compiled more than 20,000 expressions over eleven months, with examples of their use in ideology, politics, society, economics, and the military.

As was customary at the time, Mao slogans appeared on the first page. Instead of revolutionary calls, the Great Chairman demanded: “Do good publishing work” and “for the benefit of the Chinese people and the people of the whole world.” This was in line with Beijing’s desire to at least make foreign countries understand the terms the secluded nation was speaking and thinking in.

Because China’s leadership wanted to open its doors to the West out of fear of its enemy, the Soviet Union. In 1969, the two states had clashed for the first time at the Amur River. In early 1971, US National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger arrived in Beijing for secret negotiations.

The new dictionary was only a small signal of great change. Its hundreds of translated anti-Soviet terms reflected the deep rift with the Soviet Union. Mao’s propagandists called them “revisionist” and “social-imperialist” and their leaders “new tsars” with “Great Russian chauvinism” (大俄罗斯沙文主义). Example sentences mainly attacked Nikita Khrushchev.

Nowadays, the difference could not possibly be greater. Shortly before Moscow’s war of aggression on Ukraine, President Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin pledged a friendship with “no limits” and cooperation without “forbidden areas” in a 15-page agreement. Today’s linguistic hatred is once again directed against the USA.

The 1970 dictionary is a testimony of a bygone era. It was not reprinted after Mao’s death. Chinese under 40 who grew up in times of reform are bewildered by expressions ranging from “snake spirits and cattle devils”(牛鬼蛇神) to the “three Mao essays to be read at all times” (老三篇). Nor do they understand why, in old party jargon, rock ‘n’ roll was called the “dance of vagabonds” (阿飞舞). Instead, they are angered when Beijing’s ideologues polemically vilify their idols, fashion trends, or live streaming stars.

China’s poisoned officious language, which once spawned the grotesque word monstrosities of the Cultural Revolution, now uses different terms, but has not changed its nature. Even though the Cultural Revolution took inhumanity and hatred to extremes, the language has remained full of malice and polemics against opponents or dissidents. This also affects social media. A debate among expatriate Chinese in the US wonders why Chinese shitstorms exceed the Internet rage of other nations. This phenomenon also manifests in the aggression and absurd conspiracy theories of the so-called “wolf warriors” of the Foreign Ministry, who have abandoned any diplomatic restraint or courtesy and denounce any critical voices as an “anti-Chinese chorus” (反华大合唱), a term also present in the 1970 manual.

Cantonese reform philosopher Yuan Weishi (袁伟时) blames the ideologized school education in the People’s Republic, which he called “being raised with wolf milk”. China’s communists have manipulated both language and education to ideologically “brainwash” and ideologize society since the beginning of their rule, writes Yu Jie, an author and dissident now living in exile in the United States. He cites the linguistic research of analyst and novelist Victor Klemperer. He warned not to ignore the critical role that language plays in the creation of a totalitarian system.

But language serves this purpose in China. This is also the logic behind the ideological speeches of autocrat Xi Jinping, writes Yu in his study “From Maoism to Xiism.” Since Mao’s death, none of China’s leaders has quoted the Great Chairman as often as Xi.

Xi not only uses Mao’s language to expand his cult of personality and power, but also copies his methods. The chairman introduced “classes for Mao Zedong thought” (办毛泽东思想学习班), a term that appears in the 1970s dictionary. Xi now forces China’s ministries and commissions to run “Research Centers on Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想研究中心). Even his recent catchphrase: “The East is rising and West is declining” (东升西降) echoes Mao slogans: “the sun rises in the east – and sets in the west” (东方日盛,西方日衰), or “the east wind prevails over west wind” (东风压倒西风).

The 1970 dictionary first revealed the concept of the ancient Chinese Thirty-Six Stratagems (三十六计) to the outside world, which had been handed down for 3,000 years. Mao used them to conquer China and later assert his power. The reference book lists all 36 intrigues individually with English translation. It even reveals which stratagem was the most effective in guerrilla warfare: “Of the Thirty-Six Stratagems, fleeing is best” ( 三十六计走为上计).

Harro von Senger, a renowned sinologist and former professor of Chinese law who now lives in Switzerland and who also studied in Beijing during the mid-1970s, told me that he first found the word “stratagems” as a term for the life and survival lists in the 1970 dictionary. He has since written dozens of essays and translations on the Thirty-Six Stratagems, which have been published in 16 languages, most recently in January 2022 by a Ukrainian publishing house.

Reforms and modernization radically changed China overnight. In 2002, a series of books almost nostalgically recalled the hundreds of crafts that quietly disappeared in less than a generation along with their names. Gone were they – the scissors and knife grinder (磨刀人) who roamed the residential neighborhoods with loud chanting, the letter writer for others (代写书信), the briquette seller (卖炭) or feng shui geomancer (风水先生).

Everything changed, except China’s language. The need for reform was voiced by authors such as Ye Yanbing (叶延滨) in 2007. He called in vain for creating a dictionary on the inhumane language of the Cultural Revolution (文革说文解字), based on the classical explanatory encyclopedia for terms in ancient China.

Michael Kahn-Ackermann, a translator and the former director of the Beijing Goethe-Institut, says that there has never been a reappraisal of the contemporary literary language of Baihua (白话), which has existed for 100 years, much less “liberating a language that has become increasingly stereotyped since 1949.”

This issue haunted Chinese intellectuals after the end of the Cultural Revolution, says Kahn-Ackermann. A Cheng (阿城), for example, is still fighting for a humane language. Yu Hua (余华) addressed this in his book “China in Ten Words“. Others, such as the satirist Wang Shuo 王朔, tried to detoxify the official language through ironization.

If you flip through the 1970 dictionary, you will be shocked by the countless inhuman expressions that are used to this day, of the ” wolf-like nature” of the enemy (豺狼本性) who must be fought “bitterly and bloodily” (残酷的流血斗争).

The recent re-ideologization is further encrusting China’s language and thinking. How this will fit in with the modern superpower that China aspires to be is the same question that many other areas of China face, such as how innovation and initiative are to thrive under ever-stricter surveillance, control, and censorship. The answer is still missing.

Hans-Peter Friedrich will become the head of the German-Chinese parliamentary group, reports the Berlin website “The Pioneer”. Friedrich is a renowned expert on China and co-founder of the China-Brücke (China Bridge). He served as Vice President of the German Bundestag until the change of government.

Gary Liu, previously head of the South China Morning Post owned by Alibaba Group, is to lead an Alibaba start-up for the management of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). The group is thus looking for a new CEO for SCMP.

Cherry blossoms against a mountain panorama – the cherry orchard in the Guian New Area (Guizhou Province) is a tourist magnet with many charms.