When buying a product, not only is quality important for the purchase decision, but also the message behind the brand name. Here, even the most modern EVs from China continue to have a disadvantage in international markets. This is shown by a survey by the opinion research institute Civey, especially conducted for China.Table. Only one-fifth of those surveyed would currently buy a Chinese vehicle brand. Frank Sieren analyses what this means for the market entry of Nio, Lynk or MG (yes, they are now Chinese too).

Space travel has become smaller and less complicated. Instead of government programs running into the billions, agile private companies are taking over an ever larger share of the business. Not only do German companies want to follow US pioneers like SpaceX into this lucrative market, but also Chinese ones. As always in China, initial enthusiasm leads to overinvestment, productive chaos and a mad race between provinces. We look at whether this will make satellite launches dirt cheap in the future.

This time, our columnist Johnny Erling tells us about how he got to the bottom of China’s most spectacular forgery. Between 1969 and 1970, construction workers secretly rebuilt the Tian’anmen Gate. As was customary in the Mao era, the project was surrounded by the utmost secrecy. China’s rulers were already demonstrating their power over what the people were allowed to know and what they were not.

So far, German consumers are still skeptical about Chinese EV brands, as a survey conducted by China.Table together with the opinion research institute Civey shows. 69 percent of those surveyed cannot yet imagine buying a car from a Chinese manufacturer. Only one-fifth would currently do so, the remaining participants are still undecided.

Skepticism is very similar across all age groups. Openness to China’s car brands is highest among 40- to 49-year-olds (at 23 percent) and lowest among seniors over 65 (19 percent). You can find out more about Civey’s digital market and opinion research here.

Despite their restraint, many surveyed participants think that Chinese car brands will be successful in the long term. 45 percent trust Chinese brands to gain a foothold in Germany. Only 42 percent do not believe in a successful market entry. The remaining survey participants were undecided.

The first task for Chinese manufacturers is thus to change the minds of these negative and undecided customers. They have good chances in the electric segment – where they can play on technical advantages such as higher digital affinity and access to good and cheap batteries. Moreover, this is where the cards are most likely to be reshuffled.

The experience of the South Korean manufacturer Kia, the last successful rise of an Asian, shows that the price argument can crack the market. Even when Toyota dared to enter the German market 50 years ago, the “rice cookers,” as Asian cars were called condescendingly, still earned ridicule. However, because the vehicles were not only offered at a reasonable price but were also very well built, they became established in the long term.

It is still far too early to decide who will win the race among the Chinese suppliers. However, one thing stands out: In terms of quality, Chinese cars are catching up to German manufacturers. Some brands like Lynk & Co, BYD, Nio, Wuling, Li Auto or Xpeng have caught up significantly.

And the European market is currently enticing like no other: Now, more EVs are registered in Europe than in China. In Germany, registrations of electric and partially electric passenger cars achieved the highest global growth rate last year, at around 395,000 units. This means that the market is ready for EVs. But is it also ready for Chinese EVs?

One of the flashiest Chinese EV brands to target the European market is Nio. The Shanghai-based company sold 43,728 EVs in China in 2020 – twice as many as the year before. Although the company, listed on the New York Stock Exchange, was founded only seven years ago, its market capitalization of about €75 billion exceeds that of Daimler or BMW. However, unlike Daimler and BMW, Nio is not yet making money.

In September, Nio plans to deliver the ES8 model in Norway (China.Table reported). This is an electric SUV from the premium segment. Norway already has the highest share of EVs in the world. In 2020, just over half of all newly registered vehicles in Norway were pure electric. A Nio flagship store is scheduled to open in Oslo in the third quarter, with the ET7 sedan to follow in 2022. Market entry in Germany is also planned for 2022. Around 150 of Nio’s more than 7000 employees already work in Europe.

The five-meter long ET7 with exchangeable batteries convinces with its good design. However, the curve dance is not its strength because Nio is quite stubborn. As is usual with Chinese cars, the steering also doesn’t feel as direct as in the European premium competition. The suspension is rather soft by European standards. However, all this is improvable. There are plenty of gadgets: The side windows can be raised and lowered by voice command.

The Chinese competitor Xpeng is already delivering to Norway. In December, around 100 units of the all-electric G3 SUV are said to have sold there. It is already very reminiscent of the Tesla S. The group plans to launch its P7 e-sedan on the European market later this year. Also planned is a European subsidiary. The P7 opens its door via facial recognition. If necessary, it can also be opened by fingerprint.

The Hongguang Mini EV from Wuling, currently China’s most successful EV, is also available in Europe in small numbers. Here it is imported by the Latvian Dartz Motorz Company and sold under the name Freze Nikrob EV. In 2022, the Wuling Mini EV Convertible unveiled at the Shanghai auto show should also be ready for export.

With the Elaris Finn, another electric two-seater is launching on the German market. The company of the same name, based in Grünstadt (Rhineland-Palatinate), sources its Mini from the manufacturer Dorcen in the Chinese province of Jintan. Minus all tax breaks and bonuses, the Elaris Finn is priced at €9,420. The city car has a bigger brother in the compact SUV class, the Elaris Leo. The workshop service is provided by the Euromaster chain.

MG, now Chinese, is, in a sense returning to Europe. The company was founded 100 years ago in Oxford, but since 2007 it has belonged to SAIC from Shanghai, one of China’s largest car manufacturers. With its compact electric SUV ZS EV, the company is making its e-launch in Europe. Cost: around €32,000. In the Euro NCAP crash test, the car received five stars – the maximum score. This is no longer unusual for Chinese cars. Two significantly larger E-SUVs are to follow in the course of the year. However, the Chinese models do not tie in with MG’s great times. They are practical and pleasing but confusable.

It is eagerly awaited to see how Lynk & Co’s vehicles perform in the European market (China.Table reported). The significant advantage of Lynk: You get a Volvo very cheaply. The car is based on the platform of a V40. Geely, the parent company of Lynk, bought Volvo in 2010. Interesting is the option to subscribe to the car instead of buying it. Generally, a subscription is worthwhile if the monthly price is less than 1.5 percent of the purchase price. Lynk is well in the running with 1.2 percent. The highlight: customers can share their car with other members – and earn money that way.

BYD also wants to launch in Europe this year. BYD is one of the largest EV manufacturers and one of the world’s largest battery manufacturers. BYD is about to launch three cars that are competitive in Europe. An SUV, the Tang, the Han, a sedan, and the AE-1, a compact car that was unveiled just a few weeks ago. All three cars have already been developed with the European market in mind and designed to world-class standards by former Audi designer Wolfgang Egger.

The Wuling Mini EV has a chance of being a surprise success if it does arrive on the market at a reasonable price after all EU standards have been met. In any case, the young customers in Shanghai and Beijing are not so different in their user behavior from young people in Berlin or Amsterdam. Collaboration: fin

Chinese space travel has made ever more significant leaps in recent years. The Zhurong rover is due to land on Mars before the end of May, and the first module of China’s space station has also been launched into Earth’s orbit. A string of major successes for the state space agency CNSA and its main contractors CASC and CAISC. These are the state companies that develop and manufacture rockets for space flights.

But China has also been taking off in the private space sector for several years. Spurred by the success of US companies SpaceX (Elon Musk), Virgin Galactic (Richard Branson), and Blue Origin (Jeff Bezos), Chinese entrepreneurs have set up a considerable number of similar companies.

The company’s founders were inspired by the names of major tech companies in the USA – or by science fiction series. One, for example, is called “Beijing Interstellar Glory Space Technology”, or iSpace for short. Another is called “Space Trek,” the most obviously copied name. The industry list also includes “Galactic Energy”, “C-Space” or an “Ultimate Nebula Co.”

These new players are each attacking different areas of the emerging business. iSpace and Galactic Energy, for example, focus on rocketry and satellite transportation, Ultimate Nebula Co wants to offer spaceflight consulting, while C-Space opened a research center in the Gobi Desert for a possible manned Mars mission.

Expectations are high worldwide for a huge emerging market. In 2019, the space industry turned over $366 billion (€302 billion), according to figures from the Cologne-based Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft (IW), and is growing fast. By the start of the next decade, the market could be as large as $1,400 billion. The new space ambitions in China are also relevant for Germany. A privately financed industry for rocket launches and small satellites is establishing itself there. The Nordholz airfield near Cuxhaven is already discussed as a site for a spaceport.

Besides the mining of raw materials on near-Earth celestial bodies and space tourism, both of which are still in the distant future, the main business is the construction of satellites and their placement in orbit. Satellite technology has changed a lot in the last few decades. These days, artificial celestial bodies no longer weigh tons or are as big as minibusses. Some of them weigh just 25 to 50 kilograms and do not necessarily have to be placed in a distant geostationary orbit but can operate in a near-Earth orbit.

As demand increases, satellites become cheaper because they can be mass-produced. Also, due to the shorter distance and the smaller weight, the price of transport decreases. In turn, smaller and thus much cheaper rockets are suitable.

Despite the Americans’ greater experience, experts do see market opportunities for Chinese challengers. James Zhang, CEO of the Luxembourg headquarters of Chinese company Spacety, recently told MIT Tech Review. China can “take advantage of the space industry’s new need for mass production of satellites and rockets alike.”

That’s why Chinese companies focus primarily on producing satellites cheaply and launching them into space just as cheaply. When iSpace became the first private Chinese company to successfully launch a rocket into space in 2019, several satellites were released. The company is taking a strong conceptual cue from SpaceX in that it also wants to use recyclable rocket stages. Galactic Energy, on the other hand, has already caused quite a stir among experts, as the Ceres and Pallas rockets they build are compact and can still carry considerable payloads.

If desired by the customer, the companies can also monitor the satellite in orbit. These are services particularly aimed at countries with only a small space travel budget but still require satellite technology.

The state sees the companies not as competition for its own space plans but as a complement to them. While state spaceflight pushes the boundaries of what is possible for China and grasps national prestige, commercial spaceflight has, on the one hand, the benefit for the government of opening up a pool of talent from which state spaceflight can also draw. On the other hand, companies are expected to make money. Privatization is part of the state’s strategy to develop in this area.

The Chinese government gave the starting signal in 2014, a year after the Head of State and Government, Xi Jinping, took the helm. Private spaceflight was identified as a key driver of innovation, and investment in this area was encouraged. In the recently published 14th Five-Year Plan, planners decided to build a spaceport designed specifically for commercial spaceflight.

There is also heavy investment at the provincial and municipal levels. In the last few months, there has been a flurry of reports of provinces wanting to invest in new space centers. For example, there is the Wenchang spaceport on Hainan Island, from which Long March 5 and Long March 7 rockets are launched. The latter wants to add another launch pad from which smaller commercial rockets can be launched. The city of Guangzhou has also formulated plans to form a commercial space hub. The main driver here is Chinese automaker Geely, which wants to locate its own aerospace division there. The company is specifically interested in satellite and communication technologies that will help expand a network for autonomous driving.

But how big the demand for space services from Chinese companies will actually turn out to be, depends on how much the Chinese companies are trusted. On the one hand, it’s about confidence in the company’s capabilities. The second launch of a Hyperbola rocket by iSpace failed in February. The company OneSpace also experienced significant setbacks. They join a host of companies whose rockets have so far exploded on launch.

On the other hand, it is questionable how independently the companies can ultimately operate from the Chinese government and military. There is still a lack of transparency. This relates specifically to the question of whether countries or companies are willing to have their satellites operated and monitored in space by Chinese companies. China will thus have to build trust in the world, which may take much longer than building a spaceport or a space station. Gregor Koppenburg/Joern Petring

German UN Ambassador Christoph Heusgen has called on the Chinese government to end the detention of Muslim Uyghurs in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Speaking at a virtual high-level meeting organized by the Permanent Mission of the Federal Republic of Germany to the United Nations, Heusgen said: “We appeal to China to respect the universal declaration of human rights and call on China to demolish the internment camps.”

Christoph Heusgen reminded China that all UN member states have an “unconditional obligation” to respect the Declaration of Human Rights. This was “clearly not the case” in Xinjiang. In his welcoming message, the diplomat thanked all the partners who officially supported the event, which lasted about an hour and a half, including the UN permanent missions of nine other EU states as well as the US, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Albania. Heusgen saw the lively participation as an indication of “the seriousness of the situation.”

He explicitly thanked all co-organizers “for coming together despite massive Chinese threats.” In the run-up to the event, China had called on UN members to boycott the “anti-Chinese event.”

The Chinese government is holding an estimated one million people in camps in Xinjiang against their will; most of them are Uyghurs. Meticulous research by human rights organizations, journalists, and academics reveals massive human rights crimes by the Chinese state. The US government calls the events genocide. China claims that people are receiving education to get better chances in the job market. Beijing categorically rejects any accusations of human rights crimes.

Human Rights Watch called on the UN to press China for access to an independent commission of inquiry. Heusgen took up the ball: “If they (the Chinese government) have nothing to hide, why don’t they grant access to the High Commissioner (for Human Rights)?” grz

Between 2017 and 2019, the number of births in Xinjiang is said to have fallen by 43 percent. This is derived by the Australian think tank Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) from official statistical data of the People’s Republic. If the figures are correct, then the particularly rapid decline in the birth rate supports the assumption that China is enforcing a rigid policy of population control in Xinjiang. According to the ASP, the decline was as high as 57 percent in regions where mostly Uyghurs live. The scientists speak of “family deplaning.”

Chinese officials, however, explain the development differently. The change in birth rates is related to good economic policy, a spokeswoman for the Foreign Ministry told the Reuters news agency. ASPI had falsified the data and concluded by the hair. In fact, the minority Uyghurs grew faster than the Han Chinese group in the same region during the period in question, she said. Population planning affects all ethnic groups there. fin

The state-owned oil and gas company Sinopec has signed a cooperation agreement with Great Wall Motors for the joint development of hydrogen car technologies. This includes the demonstration of hydrogen cars as well as the construction of filling stations for this vehicle technology. The two sides will “strengthen research cooperation in the fields of energy production, storage, transportation, refueling and utilization of gaseous and liquid hydrogen,” Great Wall Motors said in a statement.

In March, Great Wall Motors announced it would spend the equivalent of $465 million on hydrogen research – but without giving a time frame. Sinopec plans to build 1,000 hydrogen filling stations by 2025. Sinopec produced 3.5 million tons of hydrogen last year, 14 percent of China’s output. nib

These are still rumors – but they have been around for some time: VW considers producing the ID.3, the second model of its ID EV brand, in China at SAIC shortly. This was reported by several Chinese media on Wednesday. They show photos of an ID.3 prototype that is said to have been on a test drive in China. Youtube videos of alleged test drives of the car in Shanghai are also circulating. The SAIC VW joint venture in Shanghai is said to have expressed interest in manufacturing it. Volkswagen already produces two China versions of the ID.4 compact electric SUV on the MEB modular electric drive platform, the ID. 4 X with SAIC VW in Shanghai and the ID.4 Crozz with FAW VW in Foshan, southern China. The car directly attacks US competitor Tesla: According to the website Inside EVs, even the most expensive version of the ID.4 Crozz is cheaper than a standard Tesla Model 3 model.

The smaller ID.3 was initially only intended for Europe due to its hatchback shape and is rolling off the production line at the VW plant in Zwickau. But young people in China, once a country of sedans and SUVs, are increasingly warming up to this more compact type of car. It seems entirely plausible to bring ID.3 to China. Volkswagen Group China wants to sell up to 1.5 million EVs by 2025 with all its joint ventures.

The ID.3 rumors started back in November 2020, when Automobilwoche wrote about China’s plans for the ID.3. At the end of March, the Chinese portal Auto Sina reported that SAIC had confirmed the market launch of two other MEB EVs in China during test drives with the ID.4: that of the ID.3 and that of the ID.6. The electric seven-seater ID.6 was presented at the Shanghai auto show in April. It is initially intended for China only – and like ID.4, it will come in two versions. ck

Blackrock may launch an asset management unit in China. The world’s largest asset manager got the green light from the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission on Wednesday to set up a joint venture with China Construction Bank (CCB) and Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund Temasek. Blackrock will hold 50.1 percent, CCB 40 percent, and Temasek the remaining 9.9 percent, reports business portal Caixin.

Blackrock is one of the first Western asset managers in the Chinese market. It follows France’s Amundi Asset Management, Europe’s largest asset manager, and London-based Schroders PLC. The asset manager is also currently awaiting final approval to operate its own mutual fund company in China. The asset manager principally received permission in August last year. It would be the first wholly foreign-owned investment fund company in the People’s Republic.

Larry Fink, Chief Executive of Blackrock, said: “We are committed to investing in China to provide domestic assets for domestic investors.” The People’s Republic’s financial investment market accounted for $18.9 trillion and had grown by 10 percent between 2019 and 2020, the Financial Times reported. China opened its financial sector in April 2020 as part of a tentative trade agreement between China and the US. nib

According to a survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong, 42 percent of the expats surveyed are “considering or planning” to leave the former British colony. The given reason is Beijing’s increasing influence but also the strict quarantine rules due to the Covid pandemic.

62 percent of respondents said the National Security Law, in effect since last summer, was one reason they were considering leaving Hong Kong. The controversial law prohibits sedition, secession, and subversion against Beijing and allows Chinese state security to operate in Hong Kong as well.

In addition, the strict quarantine rules are causing resentment. 49 percent of respondents said strict quarantine rules made it difficult for them to travel and visit their families. Currently, travelers arriving in Hong Kong from abroad must spend up to 21 days in hotel quarantine at their own expense.

The financial metropolis of Hong Kong has been an attractive location for foreign companies and their employees. But uncertainty about the scope and interpretation of China’s security law made Hong Kong’s image suffer. According to the law, foreigners living and working in Hong Kong are to be covered by the security law and can be prosecuted for violations. niw

The Taiwanese graphics card manufacturer Gigabyte Technology faces calls for a boycott. This was triggered by a social media post by the company: It would rely on quality from Taiwan instead of sourcing “low quality at a cheap price” from contract manufacturers in the People’s Republic. That turned out to be a strategic mistake by the company, which sells much of its computer gaming accessories in the People’s Republic: Major online retailers JD.com and Suning demonstratively took the brand out of stock. The graphics card manufacturer apologized on Tuesday. fin

For decades complaints about brazen counterfeiting have been a constant topic of small talk among foreigners in Beijing. China’s judiciary now prosecutes intellectual property theft, but mainly where it involves protecting the innovations and patents of Chinese high-tech companies. Some defrauded businessmen believe that China’s pirates are even culturally encouraged. According to this legend, imitation is considered a special form of respect paid to the better product. Such nonsense is still propagated in brochures aimed at improving cross-cultural understanding of the Middle Kingdom.

One thing, however, is true: Over centuries, China’s traditional artisans acquired masterful copying techniques. Unfortunately, they have also perfected the art of passing off their imitations as genuine. A hundred years ago, sinologist Richard Wilhelm wrote: “In China, the ratio of fakes to genuine objects has been estimated at two to one. I consider this estimate very optimistic and would like to raise it at least to 999 to one, and still call this figure very modest.”

As early as 1800, Immanuel Kant knew how tricky China’s counterfeiters were. “They cheat in a very artistical way,” he said pointedly: “They can sew a torn piece of silk so nicely back together that the most attentive merchant does not notice it; and they patch up broken porcelain with copper wire pulled through in such a way that no one is initially aware of the breakage. He is not ashamed when he is affected by fraud but only in so far as he had thereby shown some clumsiness.”

As a correspondent, I often came across cases of incredible copying. Under Mao Zedong, China’s leadership succeeded at the most ingenious trickery in December 1969. By order of the Politburo, the 66-meter-long, 37-meter-wide, and 32-meter-high old Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tian’anmen), now the landmark of the People’s Republic, was torn down to its foundations and rebuilt. The operation, disguised as “Secret Project Number 1” (一号机密工程), lasted 112 days.

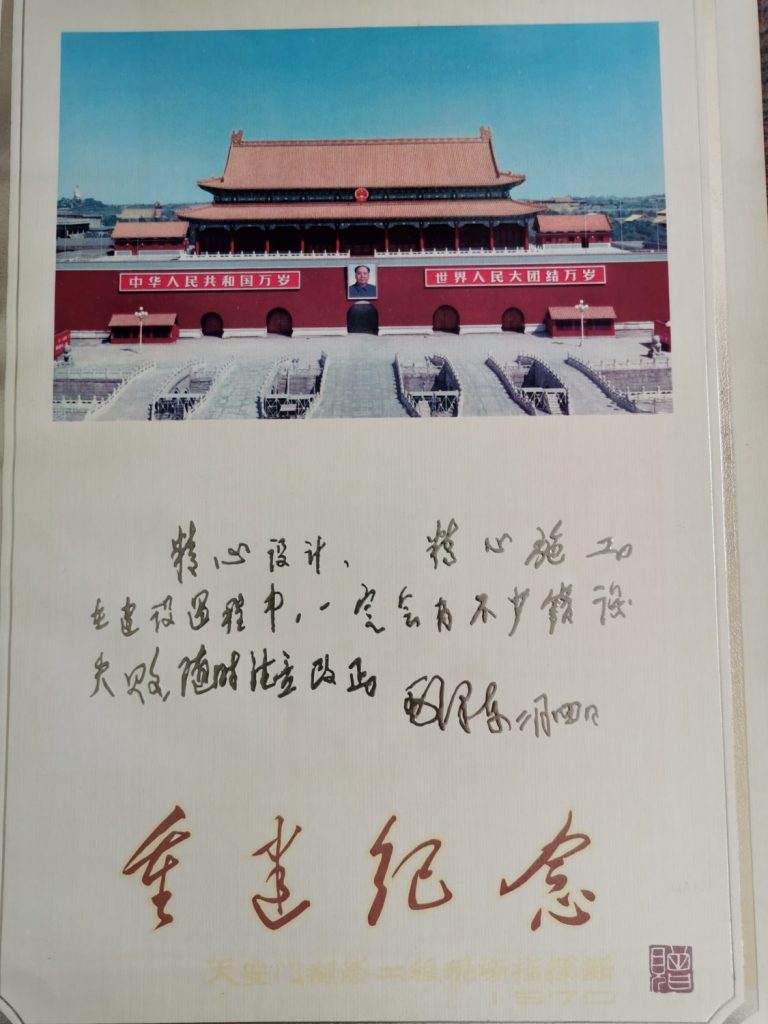

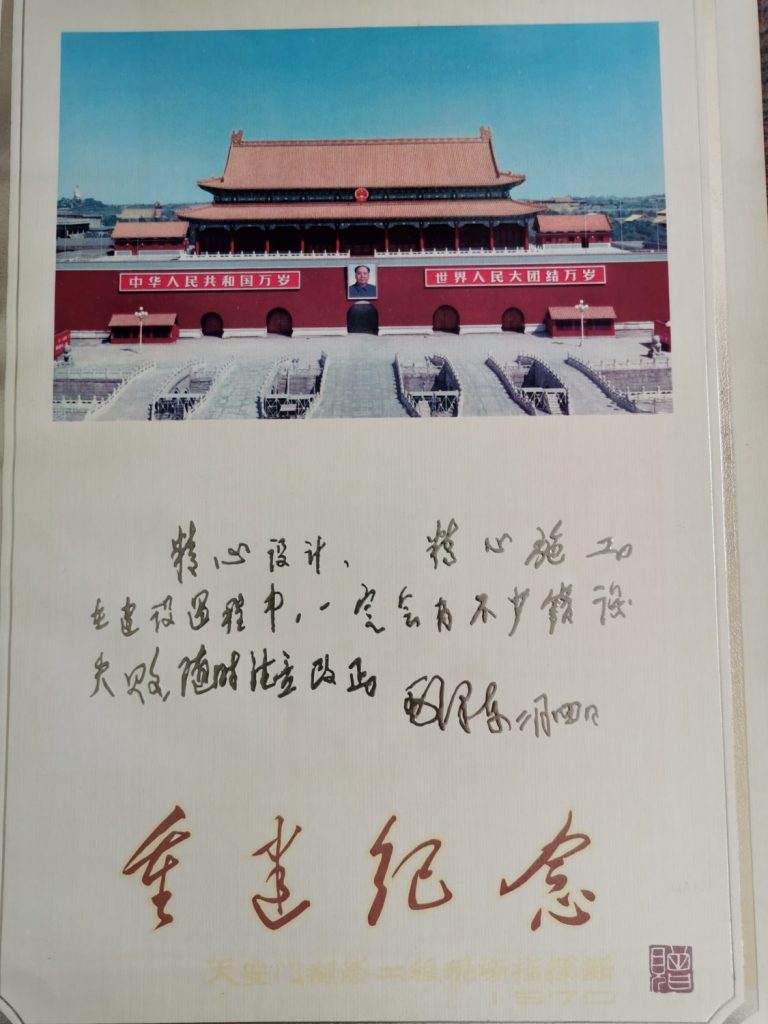

For a full 30 years, Beijing passed off its copy as the original. It was rather by chance that I discovered the secret. Around the year 2000, I found a document at an antique market in Beijing’s Baoguangsi Temple. It shows a photo of the Tian’anmen Gate and four characters: “In memory of the reconstruction.” In Mao’s handwriting, it reads, “Take great care in design and construction. There are bound to be mistakes and failures in construction. They must be corrected in time. Mao Zedong, February 4, 1970.”

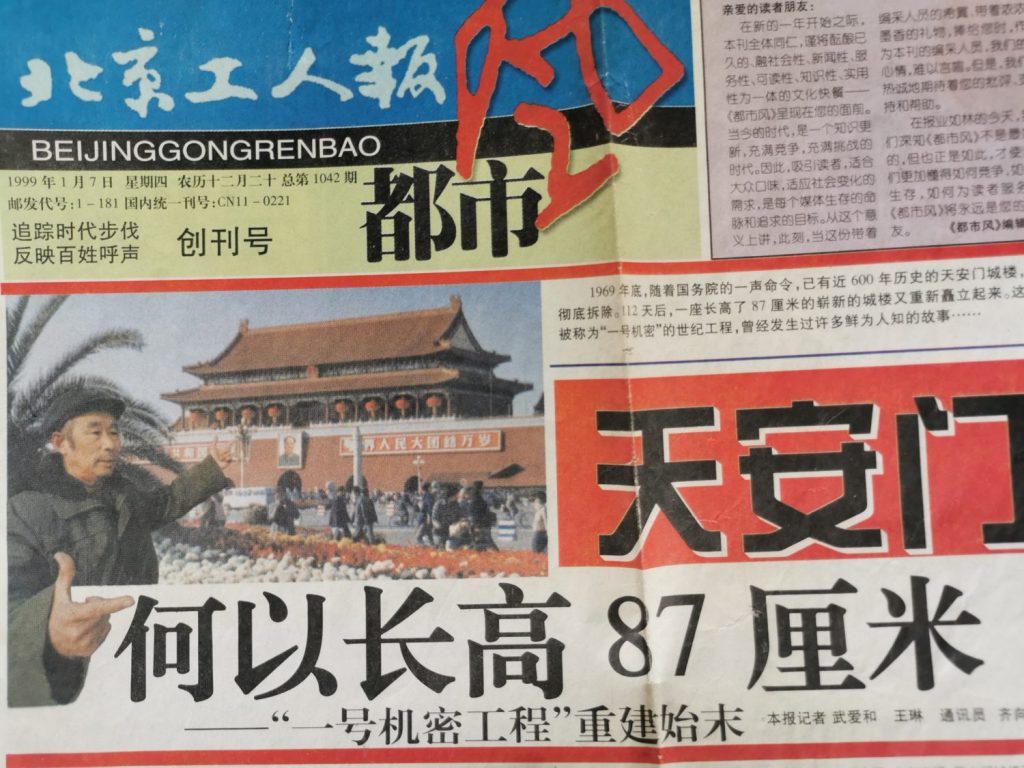

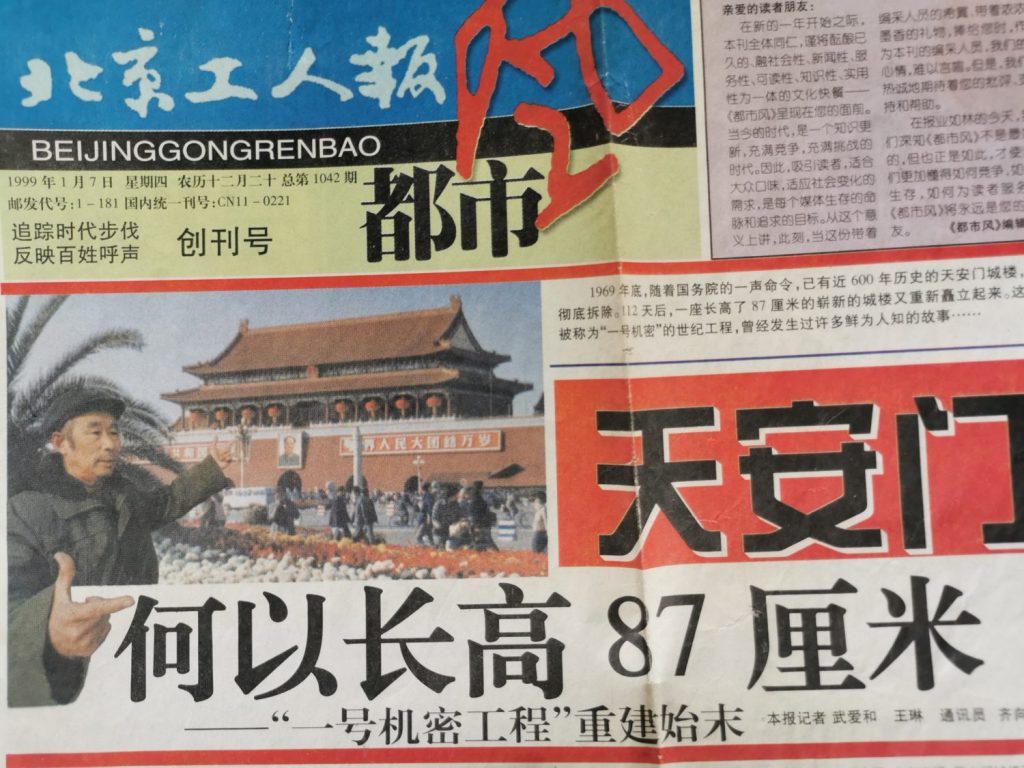

While researching, I came across the new Beijing newspaper “Capital Wind” (都市风). Its first issue appeared on Jan.7, 1999, under the headline, “Why is the Tian’anmen Gate 87 centimeters higher?” It revealed how the gate was dismantled in the winter of 1969 and rebuilt by April 1970. However, it was said to be 87 centimeters higher than the original because of bigger roof gables.

In 1969, China was on the brink of war with the Soviet Union. Mao wreaked havoc with his Cultural Revolution. Beijing, however, had another concern. Construction experts had alerted their leadership the year before that the Ming-era Tian’anmen was beyond repair. Its wooden structure, including 60 supporting pillars up to 12 meters high, was rotten, its foundations had sunk due to the falling water table, and the structure had been cracked by the 1966 earthquake in Xingtai, 300 kilometers away. In short – the highly symbolic gateway from which Mao had proclaimed the People’s Republic in 1949 was in danger of collapsing. In an emergency meeting, the Politburo agreed to demolish and rebuild it.

Logistically, the secret operation turned into a nightmare. From December 12 to 15, 1969, the “largest shell in the world” was first constructed from spar fir wood, glued together with woven mats of reed, and stabilized with steel pipes on the floor. Bamboo mats closed the roof as a lid. Inside, a network of hot water pipes fed from a boiler behind the gate ensured a working temperature of 18 degrees, while outside temperatures were below zero.

From the outside, the gate looked like a wrapped giant ark. In a comprehensive report on the covert operation, a rare photo was published by a Beijing daily newspaper in April 2016.

Even the construction manager at the time, Xu Xinmin, and experts in the imperial style of wooden construction, which did not require nails, such as Yao Laiquan, or the master carpenter Sun Yonglin, now reported. The demolition took seven days. Each beam was noted where it sat and how it once sat, and thousands of photos were taken. Up to 2,700 construction soldiers, including artisans, carpenters, painters, and joiners, camped in the parks behind the gate.

Mao demanded that no “customs be changed in the reconstruction.” The construction managers, who later received Mao’s certificate as a memento, obtained dry wood from old demolished Beijing city gates. Ebony was supplied by the army of China’s subtropical island of Hainan. They had huge supporting beams imported from Gabon and northern Borneo. Beijing spared no expense. For the murals alone, six kilos of gold leaf were needed. 216 factories and institutes from 21 provinces in China participated in the supply. No one was told what it was about.

China’s rulers demonstrated their absolute power to keep their projects secret for years and still bring them to success under the most adverse conditions. Beijing still understands this political art today.

For this, even Mao was willing to jump over his shadow. His socialist China adhered to ancient geomantic traditions when lucky charms were found during the demolition of the Tian’anmen Gate. They had been deposited centuries ago in a miniature cedar box in the exact center of the roof gables during the roofing ceremony. Mao had a 17-centimeter-high and 12-centimeter-wide jade-like marble stone inscribed in gold placed in the same spot: “Rebuilt: January to March 1970”.

It makes you want to dig out your old Gameboy from the attic – does it still work? A mural in Xi’an shows Nintendo plumber Mario in a distinctive pose.

When buying a product, not only is quality important for the purchase decision, but also the message behind the brand name. Here, even the most modern EVs from China continue to have a disadvantage in international markets. This is shown by a survey by the opinion research institute Civey, especially conducted for China.Table. Only one-fifth of those surveyed would currently buy a Chinese vehicle brand. Frank Sieren analyses what this means for the market entry of Nio, Lynk or MG (yes, they are now Chinese too).

Space travel has become smaller and less complicated. Instead of government programs running into the billions, agile private companies are taking over an ever larger share of the business. Not only do German companies want to follow US pioneers like SpaceX into this lucrative market, but also Chinese ones. As always in China, initial enthusiasm leads to overinvestment, productive chaos and a mad race between provinces. We look at whether this will make satellite launches dirt cheap in the future.

This time, our columnist Johnny Erling tells us about how he got to the bottom of China’s most spectacular forgery. Between 1969 and 1970, construction workers secretly rebuilt the Tian’anmen Gate. As was customary in the Mao era, the project was surrounded by the utmost secrecy. China’s rulers were already demonstrating their power over what the people were allowed to know and what they were not.

So far, German consumers are still skeptical about Chinese EV brands, as a survey conducted by China.Table together with the opinion research institute Civey shows. 69 percent of those surveyed cannot yet imagine buying a car from a Chinese manufacturer. Only one-fifth would currently do so, the remaining participants are still undecided.

Skepticism is very similar across all age groups. Openness to China’s car brands is highest among 40- to 49-year-olds (at 23 percent) and lowest among seniors over 65 (19 percent). You can find out more about Civey’s digital market and opinion research here.

Despite their restraint, many surveyed participants think that Chinese car brands will be successful in the long term. 45 percent trust Chinese brands to gain a foothold in Germany. Only 42 percent do not believe in a successful market entry. The remaining survey participants were undecided.

The first task for Chinese manufacturers is thus to change the minds of these negative and undecided customers. They have good chances in the electric segment – where they can play on technical advantages such as higher digital affinity and access to good and cheap batteries. Moreover, this is where the cards are most likely to be reshuffled.

The experience of the South Korean manufacturer Kia, the last successful rise of an Asian, shows that the price argument can crack the market. Even when Toyota dared to enter the German market 50 years ago, the “rice cookers,” as Asian cars were called condescendingly, still earned ridicule. However, because the vehicles were not only offered at a reasonable price but were also very well built, they became established in the long term.

It is still far too early to decide who will win the race among the Chinese suppliers. However, one thing stands out: In terms of quality, Chinese cars are catching up to German manufacturers. Some brands like Lynk & Co, BYD, Nio, Wuling, Li Auto or Xpeng have caught up significantly.

And the European market is currently enticing like no other: Now, more EVs are registered in Europe than in China. In Germany, registrations of electric and partially electric passenger cars achieved the highest global growth rate last year, at around 395,000 units. This means that the market is ready for EVs. But is it also ready for Chinese EVs?

One of the flashiest Chinese EV brands to target the European market is Nio. The Shanghai-based company sold 43,728 EVs in China in 2020 – twice as many as the year before. Although the company, listed on the New York Stock Exchange, was founded only seven years ago, its market capitalization of about €75 billion exceeds that of Daimler or BMW. However, unlike Daimler and BMW, Nio is not yet making money.

In September, Nio plans to deliver the ES8 model in Norway (China.Table reported). This is an electric SUV from the premium segment. Norway already has the highest share of EVs in the world. In 2020, just over half of all newly registered vehicles in Norway were pure electric. A Nio flagship store is scheduled to open in Oslo in the third quarter, with the ET7 sedan to follow in 2022. Market entry in Germany is also planned for 2022. Around 150 of Nio’s more than 7000 employees already work in Europe.

The five-meter long ET7 with exchangeable batteries convinces with its good design. However, the curve dance is not its strength because Nio is quite stubborn. As is usual with Chinese cars, the steering also doesn’t feel as direct as in the European premium competition. The suspension is rather soft by European standards. However, all this is improvable. There are plenty of gadgets: The side windows can be raised and lowered by voice command.

The Chinese competitor Xpeng is already delivering to Norway. In December, around 100 units of the all-electric G3 SUV are said to have sold there. It is already very reminiscent of the Tesla S. The group plans to launch its P7 e-sedan on the European market later this year. Also planned is a European subsidiary. The P7 opens its door via facial recognition. If necessary, it can also be opened by fingerprint.

The Hongguang Mini EV from Wuling, currently China’s most successful EV, is also available in Europe in small numbers. Here it is imported by the Latvian Dartz Motorz Company and sold under the name Freze Nikrob EV. In 2022, the Wuling Mini EV Convertible unveiled at the Shanghai auto show should also be ready for export.

With the Elaris Finn, another electric two-seater is launching on the German market. The company of the same name, based in Grünstadt (Rhineland-Palatinate), sources its Mini from the manufacturer Dorcen in the Chinese province of Jintan. Minus all tax breaks and bonuses, the Elaris Finn is priced at €9,420. The city car has a bigger brother in the compact SUV class, the Elaris Leo. The workshop service is provided by the Euromaster chain.

MG, now Chinese, is, in a sense returning to Europe. The company was founded 100 years ago in Oxford, but since 2007 it has belonged to SAIC from Shanghai, one of China’s largest car manufacturers. With its compact electric SUV ZS EV, the company is making its e-launch in Europe. Cost: around €32,000. In the Euro NCAP crash test, the car received five stars – the maximum score. This is no longer unusual for Chinese cars. Two significantly larger E-SUVs are to follow in the course of the year. However, the Chinese models do not tie in with MG’s great times. They are practical and pleasing but confusable.

It is eagerly awaited to see how Lynk & Co’s vehicles perform in the European market (China.Table reported). The significant advantage of Lynk: You get a Volvo very cheaply. The car is based on the platform of a V40. Geely, the parent company of Lynk, bought Volvo in 2010. Interesting is the option to subscribe to the car instead of buying it. Generally, a subscription is worthwhile if the monthly price is less than 1.5 percent of the purchase price. Lynk is well in the running with 1.2 percent. The highlight: customers can share their car with other members – and earn money that way.

BYD also wants to launch in Europe this year. BYD is one of the largest EV manufacturers and one of the world’s largest battery manufacturers. BYD is about to launch three cars that are competitive in Europe. An SUV, the Tang, the Han, a sedan, and the AE-1, a compact car that was unveiled just a few weeks ago. All three cars have already been developed with the European market in mind and designed to world-class standards by former Audi designer Wolfgang Egger.

The Wuling Mini EV has a chance of being a surprise success if it does arrive on the market at a reasonable price after all EU standards have been met. In any case, the young customers in Shanghai and Beijing are not so different in their user behavior from young people in Berlin or Amsterdam. Collaboration: fin

Chinese space travel has made ever more significant leaps in recent years. The Zhurong rover is due to land on Mars before the end of May, and the first module of China’s space station has also been launched into Earth’s orbit. A string of major successes for the state space agency CNSA and its main contractors CASC and CAISC. These are the state companies that develop and manufacture rockets for space flights.

But China has also been taking off in the private space sector for several years. Spurred by the success of US companies SpaceX (Elon Musk), Virgin Galactic (Richard Branson), and Blue Origin (Jeff Bezos), Chinese entrepreneurs have set up a considerable number of similar companies.

The company’s founders were inspired by the names of major tech companies in the USA – or by science fiction series. One, for example, is called “Beijing Interstellar Glory Space Technology”, or iSpace for short. Another is called “Space Trek,” the most obviously copied name. The industry list also includes “Galactic Energy”, “C-Space” or an “Ultimate Nebula Co.”

These new players are each attacking different areas of the emerging business. iSpace and Galactic Energy, for example, focus on rocketry and satellite transportation, Ultimate Nebula Co wants to offer spaceflight consulting, while C-Space opened a research center in the Gobi Desert for a possible manned Mars mission.

Expectations are high worldwide for a huge emerging market. In 2019, the space industry turned over $366 billion (€302 billion), according to figures from the Cologne-based Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft (IW), and is growing fast. By the start of the next decade, the market could be as large as $1,400 billion. The new space ambitions in China are also relevant for Germany. A privately financed industry for rocket launches and small satellites is establishing itself there. The Nordholz airfield near Cuxhaven is already discussed as a site for a spaceport.

Besides the mining of raw materials on near-Earth celestial bodies and space tourism, both of which are still in the distant future, the main business is the construction of satellites and their placement in orbit. Satellite technology has changed a lot in the last few decades. These days, artificial celestial bodies no longer weigh tons or are as big as minibusses. Some of them weigh just 25 to 50 kilograms and do not necessarily have to be placed in a distant geostationary orbit but can operate in a near-Earth orbit.

As demand increases, satellites become cheaper because they can be mass-produced. Also, due to the shorter distance and the smaller weight, the price of transport decreases. In turn, smaller and thus much cheaper rockets are suitable.

Despite the Americans’ greater experience, experts do see market opportunities for Chinese challengers. James Zhang, CEO of the Luxembourg headquarters of Chinese company Spacety, recently told MIT Tech Review. China can “take advantage of the space industry’s new need for mass production of satellites and rockets alike.”

That’s why Chinese companies focus primarily on producing satellites cheaply and launching them into space just as cheaply. When iSpace became the first private Chinese company to successfully launch a rocket into space in 2019, several satellites were released. The company is taking a strong conceptual cue from SpaceX in that it also wants to use recyclable rocket stages. Galactic Energy, on the other hand, has already caused quite a stir among experts, as the Ceres and Pallas rockets they build are compact and can still carry considerable payloads.

If desired by the customer, the companies can also monitor the satellite in orbit. These are services particularly aimed at countries with only a small space travel budget but still require satellite technology.

The state sees the companies not as competition for its own space plans but as a complement to them. While state spaceflight pushes the boundaries of what is possible for China and grasps national prestige, commercial spaceflight has, on the one hand, the benefit for the government of opening up a pool of talent from which state spaceflight can also draw. On the other hand, companies are expected to make money. Privatization is part of the state’s strategy to develop in this area.

The Chinese government gave the starting signal in 2014, a year after the Head of State and Government, Xi Jinping, took the helm. Private spaceflight was identified as a key driver of innovation, and investment in this area was encouraged. In the recently published 14th Five-Year Plan, planners decided to build a spaceport designed specifically for commercial spaceflight.

There is also heavy investment at the provincial and municipal levels. In the last few months, there has been a flurry of reports of provinces wanting to invest in new space centers. For example, there is the Wenchang spaceport on Hainan Island, from which Long March 5 and Long March 7 rockets are launched. The latter wants to add another launch pad from which smaller commercial rockets can be launched. The city of Guangzhou has also formulated plans to form a commercial space hub. The main driver here is Chinese automaker Geely, which wants to locate its own aerospace division there. The company is specifically interested in satellite and communication technologies that will help expand a network for autonomous driving.

But how big the demand for space services from Chinese companies will actually turn out to be, depends on how much the Chinese companies are trusted. On the one hand, it’s about confidence in the company’s capabilities. The second launch of a Hyperbola rocket by iSpace failed in February. The company OneSpace also experienced significant setbacks. They join a host of companies whose rockets have so far exploded on launch.

On the other hand, it is questionable how independently the companies can ultimately operate from the Chinese government and military. There is still a lack of transparency. This relates specifically to the question of whether countries or companies are willing to have their satellites operated and monitored in space by Chinese companies. China will thus have to build trust in the world, which may take much longer than building a spaceport or a space station. Gregor Koppenburg/Joern Petring

German UN Ambassador Christoph Heusgen has called on the Chinese government to end the detention of Muslim Uyghurs in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Speaking at a virtual high-level meeting organized by the Permanent Mission of the Federal Republic of Germany to the United Nations, Heusgen said: “We appeal to China to respect the universal declaration of human rights and call on China to demolish the internment camps.”

Christoph Heusgen reminded China that all UN member states have an “unconditional obligation” to respect the Declaration of Human Rights. This was “clearly not the case” in Xinjiang. In his welcoming message, the diplomat thanked all the partners who officially supported the event, which lasted about an hour and a half, including the UN permanent missions of nine other EU states as well as the US, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Albania. Heusgen saw the lively participation as an indication of “the seriousness of the situation.”

He explicitly thanked all co-organizers “for coming together despite massive Chinese threats.” In the run-up to the event, China had called on UN members to boycott the “anti-Chinese event.”

The Chinese government is holding an estimated one million people in camps in Xinjiang against their will; most of them are Uyghurs. Meticulous research by human rights organizations, journalists, and academics reveals massive human rights crimes by the Chinese state. The US government calls the events genocide. China claims that people are receiving education to get better chances in the job market. Beijing categorically rejects any accusations of human rights crimes.

Human Rights Watch called on the UN to press China for access to an independent commission of inquiry. Heusgen took up the ball: “If they (the Chinese government) have nothing to hide, why don’t they grant access to the High Commissioner (for Human Rights)?” grz

Between 2017 and 2019, the number of births in Xinjiang is said to have fallen by 43 percent. This is derived by the Australian think tank Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) from official statistical data of the People’s Republic. If the figures are correct, then the particularly rapid decline in the birth rate supports the assumption that China is enforcing a rigid policy of population control in Xinjiang. According to the ASP, the decline was as high as 57 percent in regions where mostly Uyghurs live. The scientists speak of “family deplaning.”

Chinese officials, however, explain the development differently. The change in birth rates is related to good economic policy, a spokeswoman for the Foreign Ministry told the Reuters news agency. ASPI had falsified the data and concluded by the hair. In fact, the minority Uyghurs grew faster than the Han Chinese group in the same region during the period in question, she said. Population planning affects all ethnic groups there. fin

The state-owned oil and gas company Sinopec has signed a cooperation agreement with Great Wall Motors for the joint development of hydrogen car technologies. This includes the demonstration of hydrogen cars as well as the construction of filling stations for this vehicle technology. The two sides will “strengthen research cooperation in the fields of energy production, storage, transportation, refueling and utilization of gaseous and liquid hydrogen,” Great Wall Motors said in a statement.

In March, Great Wall Motors announced it would spend the equivalent of $465 million on hydrogen research – but without giving a time frame. Sinopec plans to build 1,000 hydrogen filling stations by 2025. Sinopec produced 3.5 million tons of hydrogen last year, 14 percent of China’s output. nib

These are still rumors – but they have been around for some time: VW considers producing the ID.3, the second model of its ID EV brand, in China at SAIC shortly. This was reported by several Chinese media on Wednesday. They show photos of an ID.3 prototype that is said to have been on a test drive in China. Youtube videos of alleged test drives of the car in Shanghai are also circulating. The SAIC VW joint venture in Shanghai is said to have expressed interest in manufacturing it. Volkswagen already produces two China versions of the ID.4 compact electric SUV on the MEB modular electric drive platform, the ID. 4 X with SAIC VW in Shanghai and the ID.4 Crozz with FAW VW in Foshan, southern China. The car directly attacks US competitor Tesla: According to the website Inside EVs, even the most expensive version of the ID.4 Crozz is cheaper than a standard Tesla Model 3 model.

The smaller ID.3 was initially only intended for Europe due to its hatchback shape and is rolling off the production line at the VW plant in Zwickau. But young people in China, once a country of sedans and SUVs, are increasingly warming up to this more compact type of car. It seems entirely plausible to bring ID.3 to China. Volkswagen Group China wants to sell up to 1.5 million EVs by 2025 with all its joint ventures.

The ID.3 rumors started back in November 2020, when Automobilwoche wrote about China’s plans for the ID.3. At the end of March, the Chinese portal Auto Sina reported that SAIC had confirmed the market launch of two other MEB EVs in China during test drives with the ID.4: that of the ID.3 and that of the ID.6. The electric seven-seater ID.6 was presented at the Shanghai auto show in April. It is initially intended for China only – and like ID.4, it will come in two versions. ck

Blackrock may launch an asset management unit in China. The world’s largest asset manager got the green light from the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission on Wednesday to set up a joint venture with China Construction Bank (CCB) and Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund Temasek. Blackrock will hold 50.1 percent, CCB 40 percent, and Temasek the remaining 9.9 percent, reports business portal Caixin.

Blackrock is one of the first Western asset managers in the Chinese market. It follows France’s Amundi Asset Management, Europe’s largest asset manager, and London-based Schroders PLC. The asset manager is also currently awaiting final approval to operate its own mutual fund company in China. The asset manager principally received permission in August last year. It would be the first wholly foreign-owned investment fund company in the People’s Republic.

Larry Fink, Chief Executive of Blackrock, said: “We are committed to investing in China to provide domestic assets for domestic investors.” The People’s Republic’s financial investment market accounted for $18.9 trillion and had grown by 10 percent between 2019 and 2020, the Financial Times reported. China opened its financial sector in April 2020 as part of a tentative trade agreement between China and the US. nib

According to a survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong, 42 percent of the expats surveyed are “considering or planning” to leave the former British colony. The given reason is Beijing’s increasing influence but also the strict quarantine rules due to the Covid pandemic.

62 percent of respondents said the National Security Law, in effect since last summer, was one reason they were considering leaving Hong Kong. The controversial law prohibits sedition, secession, and subversion against Beijing and allows Chinese state security to operate in Hong Kong as well.

In addition, the strict quarantine rules are causing resentment. 49 percent of respondents said strict quarantine rules made it difficult for them to travel and visit their families. Currently, travelers arriving in Hong Kong from abroad must spend up to 21 days in hotel quarantine at their own expense.

The financial metropolis of Hong Kong has been an attractive location for foreign companies and their employees. But uncertainty about the scope and interpretation of China’s security law made Hong Kong’s image suffer. According to the law, foreigners living and working in Hong Kong are to be covered by the security law and can be prosecuted for violations. niw

The Taiwanese graphics card manufacturer Gigabyte Technology faces calls for a boycott. This was triggered by a social media post by the company: It would rely on quality from Taiwan instead of sourcing “low quality at a cheap price” from contract manufacturers in the People’s Republic. That turned out to be a strategic mistake by the company, which sells much of its computer gaming accessories in the People’s Republic: Major online retailers JD.com and Suning demonstratively took the brand out of stock. The graphics card manufacturer apologized on Tuesday. fin

For decades complaints about brazen counterfeiting have been a constant topic of small talk among foreigners in Beijing. China’s judiciary now prosecutes intellectual property theft, but mainly where it involves protecting the innovations and patents of Chinese high-tech companies. Some defrauded businessmen believe that China’s pirates are even culturally encouraged. According to this legend, imitation is considered a special form of respect paid to the better product. Such nonsense is still propagated in brochures aimed at improving cross-cultural understanding of the Middle Kingdom.

One thing, however, is true: Over centuries, China’s traditional artisans acquired masterful copying techniques. Unfortunately, they have also perfected the art of passing off their imitations as genuine. A hundred years ago, sinologist Richard Wilhelm wrote: “In China, the ratio of fakes to genuine objects has been estimated at two to one. I consider this estimate very optimistic and would like to raise it at least to 999 to one, and still call this figure very modest.”

As early as 1800, Immanuel Kant knew how tricky China’s counterfeiters were. “They cheat in a very artistical way,” he said pointedly: “They can sew a torn piece of silk so nicely back together that the most attentive merchant does not notice it; and they patch up broken porcelain with copper wire pulled through in such a way that no one is initially aware of the breakage. He is not ashamed when he is affected by fraud but only in so far as he had thereby shown some clumsiness.”

As a correspondent, I often came across cases of incredible copying. Under Mao Zedong, China’s leadership succeeded at the most ingenious trickery in December 1969. By order of the Politburo, the 66-meter-long, 37-meter-wide, and 32-meter-high old Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tian’anmen), now the landmark of the People’s Republic, was torn down to its foundations and rebuilt. The operation, disguised as “Secret Project Number 1” (一号机密工程), lasted 112 days.

For a full 30 years, Beijing passed off its copy as the original. It was rather by chance that I discovered the secret. Around the year 2000, I found a document at an antique market in Beijing’s Baoguangsi Temple. It shows a photo of the Tian’anmen Gate and four characters: “In memory of the reconstruction.” In Mao’s handwriting, it reads, “Take great care in design and construction. There are bound to be mistakes and failures in construction. They must be corrected in time. Mao Zedong, February 4, 1970.”

While researching, I came across the new Beijing newspaper “Capital Wind” (都市风). Its first issue appeared on Jan.7, 1999, under the headline, “Why is the Tian’anmen Gate 87 centimeters higher?” It revealed how the gate was dismantled in the winter of 1969 and rebuilt by April 1970. However, it was said to be 87 centimeters higher than the original because of bigger roof gables.

In 1969, China was on the brink of war with the Soviet Union. Mao wreaked havoc with his Cultural Revolution. Beijing, however, had another concern. Construction experts had alerted their leadership the year before that the Ming-era Tian’anmen was beyond repair. Its wooden structure, including 60 supporting pillars up to 12 meters high, was rotten, its foundations had sunk due to the falling water table, and the structure had been cracked by the 1966 earthquake in Xingtai, 300 kilometers away. In short – the highly symbolic gateway from which Mao had proclaimed the People’s Republic in 1949 was in danger of collapsing. In an emergency meeting, the Politburo agreed to demolish and rebuild it.

Logistically, the secret operation turned into a nightmare. From December 12 to 15, 1969, the “largest shell in the world” was first constructed from spar fir wood, glued together with woven mats of reed, and stabilized with steel pipes on the floor. Bamboo mats closed the roof as a lid. Inside, a network of hot water pipes fed from a boiler behind the gate ensured a working temperature of 18 degrees, while outside temperatures were below zero.

From the outside, the gate looked like a wrapped giant ark. In a comprehensive report on the covert operation, a rare photo was published by a Beijing daily newspaper in April 2016.

Even the construction manager at the time, Xu Xinmin, and experts in the imperial style of wooden construction, which did not require nails, such as Yao Laiquan, or the master carpenter Sun Yonglin, now reported. The demolition took seven days. Each beam was noted where it sat and how it once sat, and thousands of photos were taken. Up to 2,700 construction soldiers, including artisans, carpenters, painters, and joiners, camped in the parks behind the gate.

Mao demanded that no “customs be changed in the reconstruction.” The construction managers, who later received Mao’s certificate as a memento, obtained dry wood from old demolished Beijing city gates. Ebony was supplied by the army of China’s subtropical island of Hainan. They had huge supporting beams imported from Gabon and northern Borneo. Beijing spared no expense. For the murals alone, six kilos of gold leaf were needed. 216 factories and institutes from 21 provinces in China participated in the supply. No one was told what it was about.

China’s rulers demonstrated their absolute power to keep their projects secret for years and still bring them to success under the most adverse conditions. Beijing still understands this political art today.

For this, even Mao was willing to jump over his shadow. His socialist China adhered to ancient geomantic traditions when lucky charms were found during the demolition of the Tian’anmen Gate. They had been deposited centuries ago in a miniature cedar box in the exact center of the roof gables during the roofing ceremony. Mao had a 17-centimeter-high and 12-centimeter-wide jade-like marble stone inscribed in gold placed in the same spot: “Rebuilt: January to March 1970”.

It makes you want to dig out your old Gameboy from the attic – does it still work? A mural in Xi’an shows Nintendo plumber Mario in a distinctive pose.