Wherever Omicron spreads, severe consequences for global supply chains follow. This is what Wan-Hsin Liu from IfW Kiel explains in today’s interview with Finn Mayer-Kuckuk. The situation will become especially dire if the highly contagious virus variant were to actually gain a foothold in China. Almost two-thirds of the world’s intermediates now come from the People’s Republic, the economist said. Lockdowns are already happening so abruptly that companies can’t possibly prepare for them. For the Communist Party, the balancing act between growth and virus containment is critical to its survival. If one fails, the country’s political stability is at risk.

The supply of semiconductors is also vital for the Chinese economy at the moment. The country still cannot produce chips that match the quality produced in Taiwan or the USA. As confident as ever, China has set the goal of producing 17.4 percent of the global semiconductor volume by 2024. Shanghai serves as the testing ground for this ambitious goal. The entire value chain for Chinese computer chips will soon be centered in the 26 million metropolis. The local government is offering generous subsidies for factories and housing allowances for skilled labor. However, as Christian Domke-Seidel writes in his analysis, the technological gap cannot be closed in only a few months. Quantity is not quality.

Meanwhile, Chinese telecommunications equipment supplier Huawei has filed a complaint against Sweden. The Scandinavian country had excluded Huawei from expanding its domestic 5G network. Huawei is not willing to give up that easily. If the Shenzhen-based company wins in court, it could set a precedent, as Nico Beckert and Falk Steiner write in today’s feature. However, it could take years before a decision is reached.

Dr. Liu, there is currently a growing fear that the spread of Omicron to China could take the supply problem to a whole new dimension. The German trade association BGA and the BDI are already alerted.

These fears are definitely justified. Unfortunately, we must expect further disruptions; uncertainty is already increasing. As long as the pandemic is not under control, supply problems will continue worldwide. There will be increased problems wherever Omicron spreads. And if it happens in China, it will have a grave impact on global supply chains.

Why?

China has a particularly broad range of economic sectors. According to a study by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the Chinese economy encompasses all industrial sectors listed in the UN classification. In addition, China has an enormous share in the global commodity trade. With more than 60 percent of intermediate goods traded globally, China is among the top three exporters. Hardly anyone can avoid China.

Their strict Covid approach probably also plays a role.

Indeed, containment measures will, unfortunately, be deployed even quicker, more rigorously, more extensively, and for longer periods because of the risk of an Omicron contagion. Companies in affected regions will then barely have the time or chance to brace for the shocks. This immediately leads to gaps in production. This puts enormous strain on supply chains.

Zero Covid is clearly a priority in China.

Ideally, China wants to achieve both: Winning the fight against the pandemic and driving economic growth. But China is also well aware that it is not always possible to achieve both simultaneously. The current focus is on its zero-covid strategy. But I think the current media narrative that China is pursuing irrational epidemic control at the expense of the economy is wrong.

Can you elaborate on that?

There are two aspects to be considered independently here: Infection control and infection prevention. After the recent cases, there have been intense efforts to get infections under control as quickly as possible, currently in Tianjin and Beijing, for example, and before that in Xi’an. The expectation here is that severe, but brief containment measures prove effective. After the shock in Wuhan at the beginning of the pandemic, the economic and social costs of such short-term containment measures are considered acceptable. After all, even if the costs are high, they are still more acceptable than an uncontrolled spread of infection. A spread of COVID-19 can lead to social and economic instability, which ultimately jeopardizes political stability as well.

And the aspect of infection prevention?

The authorities see that the pandemic is a global challenge. They are trying to interfere as little as possible with everyday life in China. Hence the quarantine on entry and extensive contact and movement tracking. In other words, the economy is strengthened by creating a sense of normalcy for the vast majority of the population.

It may seem to be the best economic stimulus program for the national economy if life continues as normal. But the impact for foreign trade is enormous when entire ports are closed in response to isolated cases.

In this respect, China has now drawn lessons from the events of the past two years. Take Xi’an, for example: An important train station is located there, a hub for cargo train connections between China and Europe. This time, however, rail traffic was hardly affected by the local outbreak. Trucks were seamlessly diverted to other stations connected to Xi’an. Of course, if there is a reported case among dockworkers on the coast, a terminal may be closed again. However, to ensure that the flow of goods continues to some degree, there is a great effort to avoid shutting everything down in the affected regions unless absolutely necessary.

Now there is another dangerous scenario, which is now already indicated by the plant closure at VW and Toyota in Tianjin: If the Chinese vaccines are not stopping the pandemic, this could directly lead to losses in production.

This is exactly what China wants to avoid. Precisely because the domestic vaccines are less effective, the Chinese government is not letting up on its zero-covid strategy.

Infection numbers are currently skyrocketing around the globe. Can small impacts in many places at the same time snowball into a big problem?

The more intricate and longer supply chains are, the more likely it is that such problems will amplify each other. A prime example is the semiconductor industry. Companies from many economies are often involved in one electronic component: The United States, mainland China, but also Taiwan, South Korea, and so on. They each specialize in specific tasks along the supply chain. From the beginning to the end of the value chain, a semiconductor may have crossed national borders more than 70 times before it reaches the consumer. It’s like a traffic jam. The longer the line, the longer it takes for it to clear.

What is surprising is how long the situation has already lasted. When the first disruptions emerged in 2020, we were told that they would last until the summer. Where is the flexible adaptation to the new situation?

People and companies are generally flexible in thought, but production sites and infrastructures are not. They are stationary, at least for a long time. Production chains cannot be reconfigured on the fly. People’s mobility is also much more limited during the pandemic. Again, an example from Xi’an: Samsung and Micron operate semiconductor plants there. They have tried to continue to meet their customers’ demand using product stocks and by reorganizing their product lineups in their global manufacturing networks, albeit with delays. But when lockdowns drag on, inventories empty – and bottlenecks emerge all the more. The capacity of backup factories is also limited.

Does that mean time is playing against us?

Unfortunately, yes. Especially since logistics capacities are also tight. Only a limited number of ships can operate. The number of available containers is also limited. When everything was going well, such problems were not noticeable. But as soon as problems occurred in the supply chains, these problems amplified each other. Old weak spots will continue to crop up along supply chains, but new ones will emerge as well.

The commodity shortage is adding to the current rising prices. Energy price inflation is also believed to be related to Covid. How can this be?

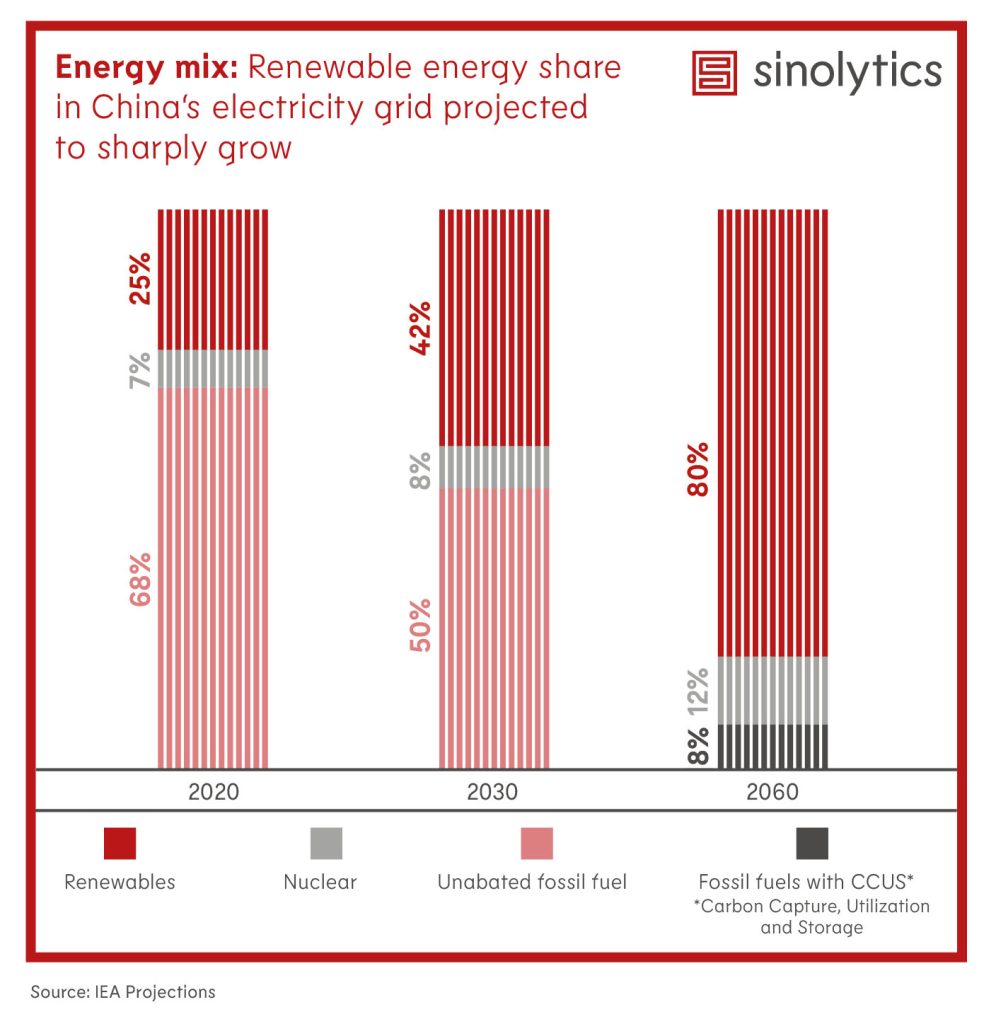

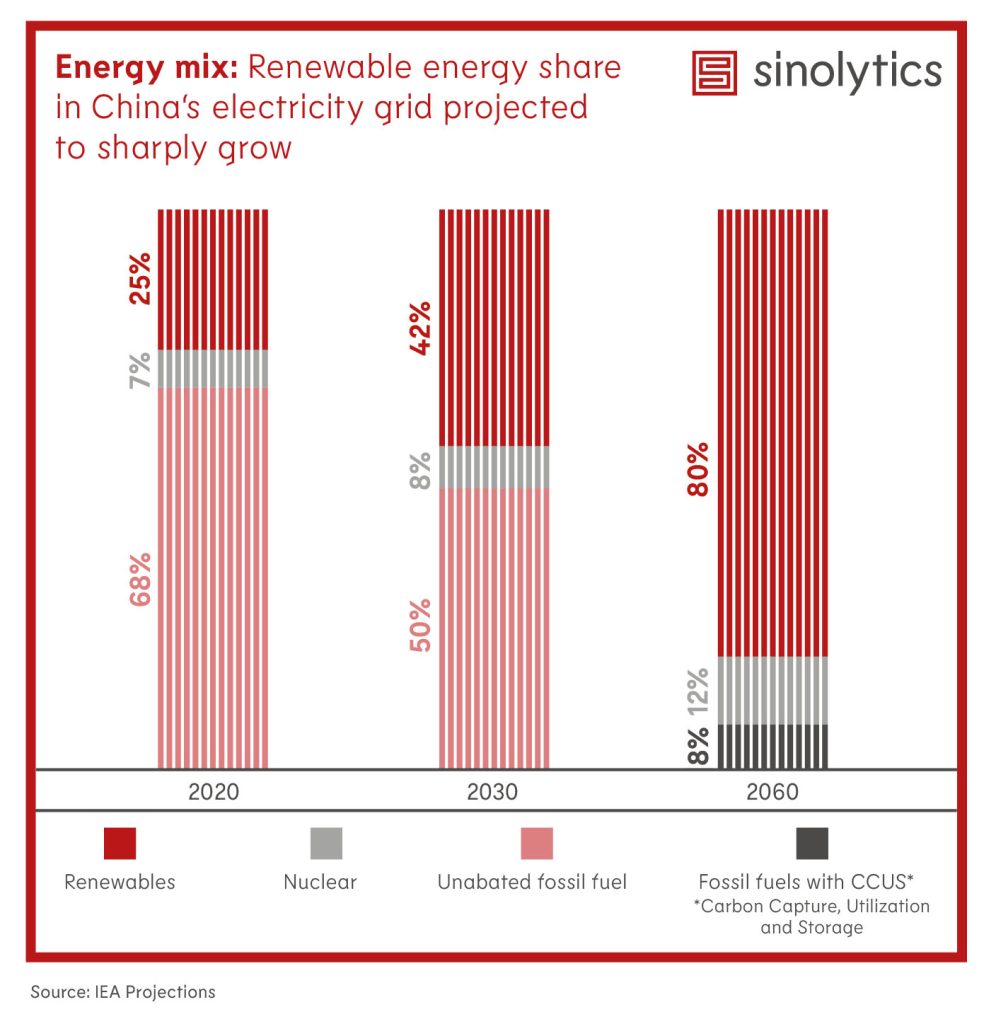

In China especially, the restructuring of its power supply has begun in parallel with achieving the climate targets. Less coal consumption is leading to greater demand for natural gas, which is now in short supply elsewhere on the global market.

Can these disruptions potentially spread to other commodity groups, such as food?

So far, the automotive sector, which relies on various electronic components, especially semiconductors, has been mainly affected. But there’s no guarantee that it won’t spread. We have simply noticed bottlenecks sooner in just-in-time production than in sectors with more warehousing or with shorter or more diversified supply chains. The spread of the Omicron variant could also affect the availability of consumer goods, food, and medicines, for example. According to a survey by the Ifo Institute, even German beverage producers are concerned about bottlenecks.

Wan-Hsin Liu researches international trade, innovation, globalization, and supply chains at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel).

Economic disaster warnings, on the one hand, euphoric plans for the future on the other: China’s massive semiconductor manufacturing problems can nowhere be observed in such a compressed form as in Shanghai. This is where China’s largest chip manufacturer (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp./SMIC) and Tesla, the world’s largest EV company, manufacture their products.

Since the outbreak of the Covid crisis, the entire economy has been suffering from crumbling supply chains. The situation is particularly bad in semiconductors. Electronics corporations and car manufacturers are having a hard time securing a sufficient chip supply of adequate quality. Volkswagen saw a 14 percent drop in vehicles shipped in China in 2021 to 3.3 million units. Stephan Woellenstein, China CEO at Volkswagen, attributed this slump to a lack of chips.

A perfect storm has formed in the semiconductor sector. In order to get a grip on the climate catastrophe and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, the government in Beijing is increasingly relying on electric cars. However, their production requires considerably more chips than ordinary combustion cars. At the same time, the trade war with the USA continues to rage on, cutting off companies from the People’s Republic from the supply of modern chips from the USA. However, China is not yet able to produce chips of the same quality as the market leaders from Taiwan or America. China’s know-how is still lagging a few years behind in this respect.

The Communist Party’s goal is for China to account for 17.4 percent of global semiconductor production in 2024. In 2020, the figure was nine percent. Currently, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC) dominates the global production of the smallest chips. Their nodes are no larger than five nanometers. These delicate semiconductors are used in modern cell phones, for example. Chinese companies, however, only dominate the production of chips whose nodes are 14 nanometers in size. It is a problem that also affects the automotive industry.

For example, a Volkswagen company spokeswoman told Table.Media, “We are in constant contact with chip brokers on all critical aspects of standard semiconductors. Wherever possible, brokerware is used after review and approval by Technical Development and Quality Assurance.” This means VW has to use chips that were not originally intended for this type of use at all, but are compatible. The problem in China is: “For certain components, however, there are no alternative commercially available processors due to specifications.”

China was only able to make great progress in the field of mass production. In 2021, 359.4 billion semiconductors were produced in China. That is at least an increase of 16.2 percent compared to the previous year.

But the quality remains the crux of the matter. In 2022, the Chinese Passenger Car Association (CPCA) calculated that one-fifth of the chips required for car production could be unavailable. Smaller manufacturers might be forced to halt production altogether. According to the market research institute AutoForecast Solutions, as many as one million vehicles less than originally planned were built in 2021 – electric cars and internal combustion engines combined. The global figure is said to be eleven million.

The metropolis of Shanghai now fears that it could become the epicenter of the crisis. Production of EVs or plug-in hybrids (NEVs) and semiconductors has been booming there for years. In 2021, 550,000 electric, hybrid, and hydrogen cars were built there – an increase of 170 percent over 2020. A proud 43 percent of all new registrations in Shanghai were NEVs. No wonder: its population is doing well. Shanghai’s economy grew by 8.1 percent in 2021 and is still expected to grow by 5.5 percent in 2022.

In return, the city is showing itself to be generous. In mid-January 2021, the government released a plan that promises extensive subsidies for the semiconductor industry. In the future, it will cover 30 percent of the costs for materials and machines used in semiconductor production. Investments in corresponding software and test procedures will also be supported with the same quota. A maximum limit of the equivalent of $15 million applies in each case.

New employees who work in this field and move to Shanghai also receive housing allowances and up to $80,000 in grants. The aim is to focus the entire value chain for semiconductors in the greater Shanghai area.

Despite its generosity, Shanghai is unlikely to achieve short-term success. SMIC has long been planning new factories in Beijing and Guangzhou. Even the technological backlog cannot be bridged within a few months, despite all the generosity. Eric Han of the consulting firm Suolei in Shanghai sums up these measures: “The mayor’s message is that huge investments will be made over the next two or three years to develop and manufacture semiconductors for cars.” However, the outcome of this effort remains to be seen.

The conflict between Huawei and Sweden is heading into the next round. The Chinese communications company has now sued the Nordic state before an international arbitration court for excluding it from the 5G network expansion. This is according to a report from the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). A spokesperson for Huawei Germany confirmed the lawsuit to Table.Media. This adds a new dimension to the dispute over the exclusion of Chinese providers from rolling out 5G networks in Western countries. In the worst-case scenario for Sweden, the country could be ordered to pay millions in damages. But lawsuits at arbitration courts can drag on for many years. It is also possible that Huawei is simply trying to deter other countries from making a similar decision.

The Huawei lawsuit against Sweden has a long history. Just over a year ago, the Chinese IT giant had already warned Sweden in a letter about a possible lawsuit. Addressing the prime minister at the time, Huawei wrote that the 5G exclusion had severely affected the business prospects of its Swedish subsidiary. The principle of “fair and equitable treatment” of international investors in the Swedish-Chinese investment agreement had been violated.

Sweden had not complied with Huawei’s request to reverse the company’s 5G exclusion. The company then sued the Swedish telecommunications regulator in April 2021. However, this lawsuit was also dismissed. Now Huawei seems to be grasping at the last straw and filed a lawsuit before an international arbitration court.

The Chinese group is facing de facto exclusion from the 5G rollout in many key markets. The USA and Australia in particular had wanted to completely exclude the company from the rollout of their 5G networks. The background to this are allegations that Huawei misused Australia’s communications infrastructure for espionage activities. European countries also shared these security concerns. By October 2021, 13 of the EU’s 27 member states had taken legal measures to prevent non-trustworthy providers from building and operating key parts of their 5G networks. Most states – including Sweden and Germany – are relying on requirements for telecommunications providers.

In Germany, the legislature added special requirements for providers to the BSI Act a year ago. According to this law, major network operators must provide the Federal Ministry of the Interior with clearance certificates from manufacturers whose systems they plan to install in critical telecommunications infrastructure. The BMI may then prohibit the deployment ex-ante. The Federal Ministry of the Interior has so far not responded to an inquiry from Europe.Table and China.Table on how often this had occurred.

Currently, the European Parliament, EU member states, and the EU Commission are also debating the so-called Network and Information Security Directive (NIS 2.0) as part of the trialogue. Huawei fears that the revision of the NIS Directive could lead to a significant expansion to areas deemed critical. If that were the case, the exclusion rules, which have so far mainly applied to core networks, could be applied to other areas, such as cloud services, throughout Europe.

Aside from Huawei, only two other network equipment suppliers have the capability of building large 5G networks. Both are European companies: Finland’s Nokia and Sweden’s Ericsson. The latter reported good annual figures for 2021 on Tuesday: Slumps in the Chinese market were more than offset by orders from other world regions such as North America – a balance sheet reflection of the geopolitical reality of 5G.

The lawsuit now filed by Huawei before an international arbitration court could cause a legal dispute lasting years. First, the arbitrators of the World Bank’s ICSID tribunal have to be appointed and determine whether the claim is valid. Once that is clarified, a great number of hearings will decide whether Huawei will receive financial compensation for the 5G exclusion. International arbitration tribunals decide whether states have breached a (bilateral) investment protection agreement – in other words, whether an investor’s rights have been violated. If this is the case, the investor will be awarded damages.

The original goal of investment protection agreements was to protect Western companies from expropriation in countries with inadequate legal systems. In the meantime, however, many Western countries have also signed investment protection agreements with each other. A few years ago, for example, Germany was sued by Vattenfall for damages amounting to €6.1 billion. The Swedish power company indirectly accused the Federal Republic of Germany of expropriation because of the nuclear phase-out. The argumentation: By phasing out nuclear power, the company would lose future profits, making its nuclear power plants in Germany worthless.

Vattenfall’s lawsuit against Germany dragged on for nine years – and ended in November 2021. The parties had settled out of court for payments amounting to €1.4 billion. However, Vattenfall filed a lawsuit at an international arbitration court and the German Constitutional Court.

Sweden is facing an arbitration claim for the first time, as reported by the expert portal Investment Arbitration Reporter (IAR). And it is also the first time Huawei got serious with a lawsuit threat. However, IAR’s experts speculate that Huawei could soon file more lawsuits as it is in a clinch with several states over its exclusion from the 5G rollout. Lengthy proceedings before international arbitration tribunals, which are also expensive for states, could deter other states from excluding Huawei from the 5G rollout. Nico Beckert/Falk Steiner

Sinolytics is a European consulting and analysis company focused entirely on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in China.

According to preliminary calculations by the Federal Statistical Office, German exports to China fell by 7.9 percent year-on-year in December to €8.5 billion. The office cited China’s zero-covid strategy as the major cause. This repeatedly led to temporary factory and port closures. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been calling on the People’s Republic to end its strict containment strategy for some time. The restrictions are a burden on both the Chinese and the global economy, according to IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva.

The Federation of German Industries (BDI) fears that the recent Cmicron outbreaks in China will lead to even more bottlenecks and rising prices. ” If the Omicron variant also spreads more quickly and easily in China, it could once again cause a bottleneck for global supply chains and fuel a recession in certain areas of the German economy,” the BDI said (China.Table reported).

While business in China weakened, exports to the USA increased by 17.6 percent to €10.7 billion euros in December. fpe

Most Chinese provinces expect lower economic growth in 2022 than in the previous year. This was reported on Tuesday by the business newspaper Caixin. According to the report, China’s developed regions such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, and Jiangsu mostly set their growth target at 5 to 5.5 percent. Less developed provinces predicted growth between 6 and 7 percent. The Covid pandemic and commodity shortages are expected to continue to weigh on economies across the country this year. Only Gansu in China’s northwest expects a higher growth compared to 2021; Inner Mongolia expects a steady growth rate. The southern island province of Hainan has set the highest target at 9 percent, followed by Tibet at 8 percent.

Provincial growth targets are published each year in advance of the National People’s Congress. During the NPC plenum in March, the premier announces the approximate growth target for all of China, which is at least partly fed by these forecasts. In 2021, China’s gross domestic product grew by 8.1 percent. Tianjin was the only one of the 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and non-government cities not to submit a forecast, according to Caixin. The port city is currently fighting a local outbreak of the Omicron variant. ck

About two months before the parliamentary elections in Hungary, the opposition has scored a success in its planned referendum on an offshoot of China’s Fudan University in Budapest. More than the 200,000 signatures needed for the referendum had been gathered, the mayor of the Hungarian capital, Gergely Karácsony, announced via social media. The citizens of Budapest will be asked whether they want to repeal a law allowing the construction of the Fudan campus.

The controversial Fudan project in Budapest had recently also made relations between China and Hungary an election issue (China.Table reported). The construction cost is estimated at around €1.5 billion. The majority, around €1.3 billion, is to be financed by a loan from a Chinese bank.

The National Electoral Authority (NVI) must now verify the signatures and set a date for the referendum. It has 60 days to do so. Budapest’s mayor attributed great symbolism to the referendum: “These signatures were collected not only because of a referendum,” Karácsony said – but also to restore confidence that politics “serves the public interest.”

The question remains whether the NVI Election Committee will schedule the referendum on the Fudan Campus during the parliamentary election on April 3. That is precisely what the opposition wants. But the organizers fear that Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s ruling right-wing Fidesz party will throw obstacles in the way – by playing for time. According to local media reports, the NVI has already announced that the counting of signatures will probably take the permitted 60 days. Critics immediately accused it of ties to Fidesz. ari

Concern over the unresolved fate of Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai has reached the Australian Open in Melbourne. Spectators at the Grand Slam tournament will now be allowed to wear T-shirts reading “Where is Peng Shuai?” after the organizers changed their stance on the matter. Over the weekend, the organizers had come under pressure after videos went viral: In them, security personnel forced spectators to take off such T-shirts. They also removed a Peng banner.

The organizers had initially insisted on tournament regulations banning clothing, banners, or signs with “promotional or political” content, according to a report by AFP. On Tuesday, CEO of Tennis Australia Craig Tiley said that people were now allowed into the stadium with clothing that could be interpreted as criticism of China’s handling of Peng Shuai – “as long as they are not coming as a mob to be disruptive but are peaceful.” Banners, however, would not be allowed to block anyone’s view of the matches.

Peng Shuai made a post on the Chinese online service Weibo in early November, accusing former Chinese Vice-Governor Zhang Gaoli of sexual assault. The post was quickly censored by Chinese authorities. Peng was not seen in public for nearly three weeks. Sports federations, the United Nations, and Western governments then expressed concern over the fate of the tennis star. Since then, the former world number one in doubles has been seen several times – including giving a television interview in Singapore. However, her situation remains unclear. Foreign countries therefore continue to worry about Peng’s well-being. The Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) has suspended its tournaments in China for the time being in protest.

China’s foreign office spokesman Zhao Lijian unsurprisingly criticized a “politicization of sports” in light of the videos on Monday. He said there was “no support whatsoever” for such protests. But that’s not entirely true. For example, 18-time Grand Slam tournament winner Martina Navratilova accused Australian Open organizers of “capitulating” to China. ck

The Coronavirus has long been considered the main threat to the Beijing Winter Olympics. Now a well-known problem has been added: air pollution in the Chinese capital. Thick smog has hung over Beijing for days; particulate matter (PM2.5) levels exceed 200 micrograms per cubic meter. The WHO recommends a level of 5 or less. Now, the Ministry of the Environment warned of persistently unfavorable weather conditions. These are typical for the transition from winter to spring, said ministry spokesman Liu Youbin. Only strong northern winds clear the winter air over Beijing; these currently do not seem to be in the forecast for the near future.

The ministry announced temporary emergency measures in Beijing and the neighboring province of Hebei in case the likelihood of severe air pollution increases during the Olympics. It said companies and vehicles with high emissions, for example, would be “managed and controlled.” The measures should have minimal impact on the economy and society, Liu said – especially on people’s livelihoods, power supply, household heating, and health care. The Games will be held from February 4 to 20.

In 2021, the capital announced that it had fully met national air quality standards for the first time. The city’s annual average PM2.5 concentration fell to 33 micrograms per cubic meter last year. That represented a 63.1 percent drop from 2013. Since Beijing won the bid to host the Winter Games in 2015, authorities have raised emissions standards for cars, closed dirty factories, and cut coal consumption. But it seems the problem is still far from over. ck

The European Commission continues to look for ways to ban imports of products made from forced labor. Sabine Weyand, Director-General for Trade from the EU Commission, rejects the approach by US authorities. The US model, which combines product-specific bans with origin bans, is “not effective,” Weyand told the European Parliament’s trade committee Tuesday. In China’s case, for example, cotton products linked to Xinjiang, but also products from Xinjiang in general, would be targeted.

The United States follows the basic assumption that all goods from Xinjiang involve forced labor. Importers are obligated to disprove this. This is a “heavy burden,” says Weyand. Under the relevant forced labor section of the US Tariff Act, US Customs is allowed to inspect and block imports for forced labor. Weyand sees this as a potential bureaucratic nightmare for EU customs processing. As an alternative, she advocated including a ban on imports of forced labor products in the planned EU Supply Chain Act. Independent legislation like that in the US would also require more time.

The EU supply chain law is to be presented on February 15. However, the EU Commission has not yet internally agreed on whether products from forced labor should be included (China.Table reported). Time could run short.

Bernd Lange, Chair of the European Parliament’s Committee on International Trade, criticized the internal disagreements of the EU Commission. “It is unfathomable that an internal body meeting in secret is slowing down the EU Commission – and thus putting off the European Parliament and the EU member states for almost a year,” Lange said. “At the latest after the State of the Union speech, in which Commission President Ursula von der Leyen promised to take decisive action against forced labor, there should have been momentum in the EU Commission.” The EU Commission chief had announced an import ban in September (China.Table reported). The presentation date for the EU supply chain law has already been postponed several times since spring 2021. ari

As in 2008, when Beijing hosted the Summer Games for the first time, the Chinese public will again be left disappointed by the external effects of the Games. After all, even then, the world press was more interested in China’s human rights violations and environmental sins than in the bright side of China’s economic miracle and the many gold medals won by Chinese athletes. The Middle Kingdom felt unfairly treated and many of its citizens were deeply offended. This year, there is a risk of an exacerbated repetition of mutual disappointment.

Let’s remember 2008: Just a quarter of a year before the Beijing Games, a devastating earthquake had caused widespread destruction in the west of the country and claimed many lives. The Summer Games offered the entire nation a chance to forget these traumatic events for a while and, as a proud host, to present the impressive results of its economic growth to the whole world.

The fact that the Games failed to bring China glory, fame, and more international respect was felt like a blow to the country’s image. This led to a rethinking of international communication in Beijing. In retrospect, the 2008 Olympic Games were a turning point in international relations with China.

Back then, most nations were battling the effects of the great economic and financial crisis that had erupted the year before – and which would spread and deepen even further around the world after the collapse of the US investment bank Lehman Brothers in September 2008. China, as it turned out a short time later, was one of the few countries that came through this economic and financial crisis unscathed in comparison. This was mainly because China’s economy and its financial sector were better protected from international influences than those of other countries. The fact that the Chinese government was able to use the opportunities of the global crisis to its own advantage at the time – in stark contrast to the USA, for example – gave it new legitimacy for its claim to power in the eyes of the Communist Party. At the same time, national self-confidence surged.

At first, Beijing tried to underpin its new power by developing a soft power strategy that would also improve China’s image in the world. But the Chinese government’s advances did not achieve the desired result: Its desire for respect and recognition among the international community did not match the way it dealt with dissidents in its own country. It lacked credibility and the lifestyle it wished to export lacked the necessary appeal.

As valid as the reasons for the West’s lack of sympathy were: They amplified the sense of disappointment. This did not remain without consequences. From around 2009 onward, the Chinese government’s tone toward the outside world became harsher. Beijing was exhilarated by its new power and frustrated by a declining yet arrogant America and a weak Europe. At the same time, it was also frustrated by its continued poor reputation in the world. The international community was suddenly talking about China’s arrogant demeanor. The confident appearance of Chinese diplomats and other representatives of the nation was indeed new. It unsettled and baffled the West.

With Xi Jinping’s rise to the top of the party and state in 2012 and 2013, China has evolved from an authoritarian to a totalitarian system. Beijing detains millions of Uyghurs in re-education camps in Xinjiang and deprives Hong Kong people of rights and freedoms that were once firmly assured. Xi has snuffed out the civil society that developed in the mid-2000s with the spread of the Internet. Today, the highly equipped censorship apparatus can hardly be overcome or circumvented by anyone in China.

This spared a large part of the Chinese population the humiliation of negative foreign media reports. However, it is to be expected that the Chinese government will filter, process, and repurpose these reports for propaganda purposes to provide its people with evidence of the hostility of foreign powers. The narrative that the US and other democracies do not welcome China’s rise and want to keep it down will circulate through the Chinese press again in the coming weeks. It has become difficult for Chinese citizens to form their own opinion about the world. But that does not mean that the disappointment about the negative external image is solely controlled by the government – or could even be controlled.

China, whose economic, political, and military power has grown dramatically since 2008, leaves no doubt that it wants to exert more influence on global affairs in the future. One indicator of this is the New Silk Road Initiative. Beyond that, much remains unclear. What is clear, however, is that China’s popularity is declining rather than increasing. According to a 14-country survey of (Western) industrialized nations by the PEW Research Center, Beijing ranked at an all-time low with an average of 73 percent negative opinion of China in 2020.

On the one hand, Beijing constantly complains about China’s negative international image. On the other hand, the government does not seem to put much effort into improving its international image by changing its behavior, if only by adopting a new, more open, and conciliatory rhetoric – not only toward the outside world. Instead, it dispatches wolf-warrior diplomats to the front, promoting rather than mitigating the image of aggressive nationalism. After all, they want to be taken seriously.

No matter how you spin it, the global crises of our time can only be solved with China, not against it. But that requires facts, not fake news. It needs science. Science thrives only in freedom, and that requires liberal democracy. The majority of international journalists who will be covering the Winter Games know this. That is why they will certainly write about China’s problems and contradictions again. If the government and its people have a hard time coping, then that is the price we have to pay in the name of our values.

Marc Bermann is a Management Consultant in Muehlheim/Ruhr. Until 2020, he was a Program Manager at Mercator Foundation, where he played a key role in setting up the Merics research institute. At the Robert Bosch Foundation, he was in charge of the China area and, among other things, organized the German-Chinese media ambassador project. Bermann has a background in sinology and political science.

Stéphane Leroy is taking over sales for China and the Asia Pacific at Bombardier. Leroy has been with the Canadian aircraft manufacturer for 20 years. He has already spent eight years in Asia. Leroy will retain his position as Vice President, Sales, Specialized Aircraft.

Andy Jones is to become President for the Asia-Pacific market region at Swiss global security group Dormakaba. He succeeds Jim-Heng Lee, who has headed the Wetzikon-based group as CEO since January 1, 2022. Jones was most recently responsible for the Japan & Korea regions as Senior Vice President. His new place of work will be Shanghai.

Wherever Omicron spreads, severe consequences for global supply chains follow. This is what Wan-Hsin Liu from IfW Kiel explains in today’s interview with Finn Mayer-Kuckuk. The situation will become especially dire if the highly contagious virus variant were to actually gain a foothold in China. Almost two-thirds of the world’s intermediates now come from the People’s Republic, the economist said. Lockdowns are already happening so abruptly that companies can’t possibly prepare for them. For the Communist Party, the balancing act between growth and virus containment is critical to its survival. If one fails, the country’s political stability is at risk.

The supply of semiconductors is also vital for the Chinese economy at the moment. The country still cannot produce chips that match the quality produced in Taiwan or the USA. As confident as ever, China has set the goal of producing 17.4 percent of the global semiconductor volume by 2024. Shanghai serves as the testing ground for this ambitious goal. The entire value chain for Chinese computer chips will soon be centered in the 26 million metropolis. The local government is offering generous subsidies for factories and housing allowances for skilled labor. However, as Christian Domke-Seidel writes in his analysis, the technological gap cannot be closed in only a few months. Quantity is not quality.

Meanwhile, Chinese telecommunications equipment supplier Huawei has filed a complaint against Sweden. The Scandinavian country had excluded Huawei from expanding its domestic 5G network. Huawei is not willing to give up that easily. If the Shenzhen-based company wins in court, it could set a precedent, as Nico Beckert and Falk Steiner write in today’s feature. However, it could take years before a decision is reached.

Dr. Liu, there is currently a growing fear that the spread of Omicron to China could take the supply problem to a whole new dimension. The German trade association BGA and the BDI are already alerted.

These fears are definitely justified. Unfortunately, we must expect further disruptions; uncertainty is already increasing. As long as the pandemic is not under control, supply problems will continue worldwide. There will be increased problems wherever Omicron spreads. And if it happens in China, it will have a grave impact on global supply chains.

Why?

China has a particularly broad range of economic sectors. According to a study by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the Chinese economy encompasses all industrial sectors listed in the UN classification. In addition, China has an enormous share in the global commodity trade. With more than 60 percent of intermediate goods traded globally, China is among the top three exporters. Hardly anyone can avoid China.

Their strict Covid approach probably also plays a role.

Indeed, containment measures will, unfortunately, be deployed even quicker, more rigorously, more extensively, and for longer periods because of the risk of an Omicron contagion. Companies in affected regions will then barely have the time or chance to brace for the shocks. This immediately leads to gaps in production. This puts enormous strain on supply chains.

Zero Covid is clearly a priority in China.

Ideally, China wants to achieve both: Winning the fight against the pandemic and driving economic growth. But China is also well aware that it is not always possible to achieve both simultaneously. The current focus is on its zero-covid strategy. But I think the current media narrative that China is pursuing irrational epidemic control at the expense of the economy is wrong.

Can you elaborate on that?

There are two aspects to be considered independently here: Infection control and infection prevention. After the recent cases, there have been intense efforts to get infections under control as quickly as possible, currently in Tianjin and Beijing, for example, and before that in Xi’an. The expectation here is that severe, but brief containment measures prove effective. After the shock in Wuhan at the beginning of the pandemic, the economic and social costs of such short-term containment measures are considered acceptable. After all, even if the costs are high, they are still more acceptable than an uncontrolled spread of infection. A spread of COVID-19 can lead to social and economic instability, which ultimately jeopardizes political stability as well.

And the aspect of infection prevention?

The authorities see that the pandemic is a global challenge. They are trying to interfere as little as possible with everyday life in China. Hence the quarantine on entry and extensive contact and movement tracking. In other words, the economy is strengthened by creating a sense of normalcy for the vast majority of the population.

It may seem to be the best economic stimulus program for the national economy if life continues as normal. But the impact for foreign trade is enormous when entire ports are closed in response to isolated cases.

In this respect, China has now drawn lessons from the events of the past two years. Take Xi’an, for example: An important train station is located there, a hub for cargo train connections between China and Europe. This time, however, rail traffic was hardly affected by the local outbreak. Trucks were seamlessly diverted to other stations connected to Xi’an. Of course, if there is a reported case among dockworkers on the coast, a terminal may be closed again. However, to ensure that the flow of goods continues to some degree, there is a great effort to avoid shutting everything down in the affected regions unless absolutely necessary.

Now there is another dangerous scenario, which is now already indicated by the plant closure at VW and Toyota in Tianjin: If the Chinese vaccines are not stopping the pandemic, this could directly lead to losses in production.

This is exactly what China wants to avoid. Precisely because the domestic vaccines are less effective, the Chinese government is not letting up on its zero-covid strategy.

Infection numbers are currently skyrocketing around the globe. Can small impacts in many places at the same time snowball into a big problem?

The more intricate and longer supply chains are, the more likely it is that such problems will amplify each other. A prime example is the semiconductor industry. Companies from many economies are often involved in one electronic component: The United States, mainland China, but also Taiwan, South Korea, and so on. They each specialize in specific tasks along the supply chain. From the beginning to the end of the value chain, a semiconductor may have crossed national borders more than 70 times before it reaches the consumer. It’s like a traffic jam. The longer the line, the longer it takes for it to clear.

What is surprising is how long the situation has already lasted. When the first disruptions emerged in 2020, we were told that they would last until the summer. Where is the flexible adaptation to the new situation?

People and companies are generally flexible in thought, but production sites and infrastructures are not. They are stationary, at least for a long time. Production chains cannot be reconfigured on the fly. People’s mobility is also much more limited during the pandemic. Again, an example from Xi’an: Samsung and Micron operate semiconductor plants there. They have tried to continue to meet their customers’ demand using product stocks and by reorganizing their product lineups in their global manufacturing networks, albeit with delays. But when lockdowns drag on, inventories empty – and bottlenecks emerge all the more. The capacity of backup factories is also limited.

Does that mean time is playing against us?

Unfortunately, yes. Especially since logistics capacities are also tight. Only a limited number of ships can operate. The number of available containers is also limited. When everything was going well, such problems were not noticeable. But as soon as problems occurred in the supply chains, these problems amplified each other. Old weak spots will continue to crop up along supply chains, but new ones will emerge as well.

The commodity shortage is adding to the current rising prices. Energy price inflation is also believed to be related to Covid. How can this be?

In China especially, the restructuring of its power supply has begun in parallel with achieving the climate targets. Less coal consumption is leading to greater demand for natural gas, which is now in short supply elsewhere on the global market.

Can these disruptions potentially spread to other commodity groups, such as food?

So far, the automotive sector, which relies on various electronic components, especially semiconductors, has been mainly affected. But there’s no guarantee that it won’t spread. We have simply noticed bottlenecks sooner in just-in-time production than in sectors with more warehousing or with shorter or more diversified supply chains. The spread of the Omicron variant could also affect the availability of consumer goods, food, and medicines, for example. According to a survey by the Ifo Institute, even German beverage producers are concerned about bottlenecks.

Wan-Hsin Liu researches international trade, innovation, globalization, and supply chains at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel).

Economic disaster warnings, on the one hand, euphoric plans for the future on the other: China’s massive semiconductor manufacturing problems can nowhere be observed in such a compressed form as in Shanghai. This is where China’s largest chip manufacturer (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp./SMIC) and Tesla, the world’s largest EV company, manufacture their products.

Since the outbreak of the Covid crisis, the entire economy has been suffering from crumbling supply chains. The situation is particularly bad in semiconductors. Electronics corporations and car manufacturers are having a hard time securing a sufficient chip supply of adequate quality. Volkswagen saw a 14 percent drop in vehicles shipped in China in 2021 to 3.3 million units. Stephan Woellenstein, China CEO at Volkswagen, attributed this slump to a lack of chips.

A perfect storm has formed in the semiconductor sector. In order to get a grip on the climate catastrophe and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, the government in Beijing is increasingly relying on electric cars. However, their production requires considerably more chips than ordinary combustion cars. At the same time, the trade war with the USA continues to rage on, cutting off companies from the People’s Republic from the supply of modern chips from the USA. However, China is not yet able to produce chips of the same quality as the market leaders from Taiwan or America. China’s know-how is still lagging a few years behind in this respect.

The Communist Party’s goal is for China to account for 17.4 percent of global semiconductor production in 2024. In 2020, the figure was nine percent. Currently, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC) dominates the global production of the smallest chips. Their nodes are no larger than five nanometers. These delicate semiconductors are used in modern cell phones, for example. Chinese companies, however, only dominate the production of chips whose nodes are 14 nanometers in size. It is a problem that also affects the automotive industry.

For example, a Volkswagen company spokeswoman told Table.Media, “We are in constant contact with chip brokers on all critical aspects of standard semiconductors. Wherever possible, brokerware is used after review and approval by Technical Development and Quality Assurance.” This means VW has to use chips that were not originally intended for this type of use at all, but are compatible. The problem in China is: “For certain components, however, there are no alternative commercially available processors due to specifications.”

China was only able to make great progress in the field of mass production. In 2021, 359.4 billion semiconductors were produced in China. That is at least an increase of 16.2 percent compared to the previous year.

But the quality remains the crux of the matter. In 2022, the Chinese Passenger Car Association (CPCA) calculated that one-fifth of the chips required for car production could be unavailable. Smaller manufacturers might be forced to halt production altogether. According to the market research institute AutoForecast Solutions, as many as one million vehicles less than originally planned were built in 2021 – electric cars and internal combustion engines combined. The global figure is said to be eleven million.

The metropolis of Shanghai now fears that it could become the epicenter of the crisis. Production of EVs or plug-in hybrids (NEVs) and semiconductors has been booming there for years. In 2021, 550,000 electric, hybrid, and hydrogen cars were built there – an increase of 170 percent over 2020. A proud 43 percent of all new registrations in Shanghai were NEVs. No wonder: its population is doing well. Shanghai’s economy grew by 8.1 percent in 2021 and is still expected to grow by 5.5 percent in 2022.

In return, the city is showing itself to be generous. In mid-January 2021, the government released a plan that promises extensive subsidies for the semiconductor industry. In the future, it will cover 30 percent of the costs for materials and machines used in semiconductor production. Investments in corresponding software and test procedures will also be supported with the same quota. A maximum limit of the equivalent of $15 million applies in each case.

New employees who work in this field and move to Shanghai also receive housing allowances and up to $80,000 in grants. The aim is to focus the entire value chain for semiconductors in the greater Shanghai area.

Despite its generosity, Shanghai is unlikely to achieve short-term success. SMIC has long been planning new factories in Beijing and Guangzhou. Even the technological backlog cannot be bridged within a few months, despite all the generosity. Eric Han of the consulting firm Suolei in Shanghai sums up these measures: “The mayor’s message is that huge investments will be made over the next two or three years to develop and manufacture semiconductors for cars.” However, the outcome of this effort remains to be seen.

The conflict between Huawei and Sweden is heading into the next round. The Chinese communications company has now sued the Nordic state before an international arbitration court for excluding it from the 5G network expansion. This is according to a report from the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). A spokesperson for Huawei Germany confirmed the lawsuit to Table.Media. This adds a new dimension to the dispute over the exclusion of Chinese providers from rolling out 5G networks in Western countries. In the worst-case scenario for Sweden, the country could be ordered to pay millions in damages. But lawsuits at arbitration courts can drag on for many years. It is also possible that Huawei is simply trying to deter other countries from making a similar decision.

The Huawei lawsuit against Sweden has a long history. Just over a year ago, the Chinese IT giant had already warned Sweden in a letter about a possible lawsuit. Addressing the prime minister at the time, Huawei wrote that the 5G exclusion had severely affected the business prospects of its Swedish subsidiary. The principle of “fair and equitable treatment” of international investors in the Swedish-Chinese investment agreement had been violated.

Sweden had not complied with Huawei’s request to reverse the company’s 5G exclusion. The company then sued the Swedish telecommunications regulator in April 2021. However, this lawsuit was also dismissed. Now Huawei seems to be grasping at the last straw and filed a lawsuit before an international arbitration court.

The Chinese group is facing de facto exclusion from the 5G rollout in many key markets. The USA and Australia in particular had wanted to completely exclude the company from the rollout of their 5G networks. The background to this are allegations that Huawei misused Australia’s communications infrastructure for espionage activities. European countries also shared these security concerns. By October 2021, 13 of the EU’s 27 member states had taken legal measures to prevent non-trustworthy providers from building and operating key parts of their 5G networks. Most states – including Sweden and Germany – are relying on requirements for telecommunications providers.

In Germany, the legislature added special requirements for providers to the BSI Act a year ago. According to this law, major network operators must provide the Federal Ministry of the Interior with clearance certificates from manufacturers whose systems they plan to install in critical telecommunications infrastructure. The BMI may then prohibit the deployment ex-ante. The Federal Ministry of the Interior has so far not responded to an inquiry from Europe.Table and China.Table on how often this had occurred.

Currently, the European Parliament, EU member states, and the EU Commission are also debating the so-called Network and Information Security Directive (NIS 2.0) as part of the trialogue. Huawei fears that the revision of the NIS Directive could lead to a significant expansion to areas deemed critical. If that were the case, the exclusion rules, which have so far mainly applied to core networks, could be applied to other areas, such as cloud services, throughout Europe.

Aside from Huawei, only two other network equipment suppliers have the capability of building large 5G networks. Both are European companies: Finland’s Nokia and Sweden’s Ericsson. The latter reported good annual figures for 2021 on Tuesday: Slumps in the Chinese market were more than offset by orders from other world regions such as North America – a balance sheet reflection of the geopolitical reality of 5G.

The lawsuit now filed by Huawei before an international arbitration court could cause a legal dispute lasting years. First, the arbitrators of the World Bank’s ICSID tribunal have to be appointed and determine whether the claim is valid. Once that is clarified, a great number of hearings will decide whether Huawei will receive financial compensation for the 5G exclusion. International arbitration tribunals decide whether states have breached a (bilateral) investment protection agreement – in other words, whether an investor’s rights have been violated. If this is the case, the investor will be awarded damages.

The original goal of investment protection agreements was to protect Western companies from expropriation in countries with inadequate legal systems. In the meantime, however, many Western countries have also signed investment protection agreements with each other. A few years ago, for example, Germany was sued by Vattenfall for damages amounting to €6.1 billion. The Swedish power company indirectly accused the Federal Republic of Germany of expropriation because of the nuclear phase-out. The argumentation: By phasing out nuclear power, the company would lose future profits, making its nuclear power plants in Germany worthless.

Vattenfall’s lawsuit against Germany dragged on for nine years – and ended in November 2021. The parties had settled out of court for payments amounting to €1.4 billion. However, Vattenfall filed a lawsuit at an international arbitration court and the German Constitutional Court.

Sweden is facing an arbitration claim for the first time, as reported by the expert portal Investment Arbitration Reporter (IAR). And it is also the first time Huawei got serious with a lawsuit threat. However, IAR’s experts speculate that Huawei could soon file more lawsuits as it is in a clinch with several states over its exclusion from the 5G rollout. Lengthy proceedings before international arbitration tribunals, which are also expensive for states, could deter other states from excluding Huawei from the 5G rollout. Nico Beckert/Falk Steiner

Sinolytics is a European consulting and analysis company focused entirely on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in China.

According to preliminary calculations by the Federal Statistical Office, German exports to China fell by 7.9 percent year-on-year in December to €8.5 billion. The office cited China’s zero-covid strategy as the major cause. This repeatedly led to temporary factory and port closures. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been calling on the People’s Republic to end its strict containment strategy for some time. The restrictions are a burden on both the Chinese and the global economy, according to IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva.

The Federation of German Industries (BDI) fears that the recent Cmicron outbreaks in China will lead to even more bottlenecks and rising prices. ” If the Omicron variant also spreads more quickly and easily in China, it could once again cause a bottleneck for global supply chains and fuel a recession in certain areas of the German economy,” the BDI said (China.Table reported).

While business in China weakened, exports to the USA increased by 17.6 percent to €10.7 billion euros in December. fpe

Most Chinese provinces expect lower economic growth in 2022 than in the previous year. This was reported on Tuesday by the business newspaper Caixin. According to the report, China’s developed regions such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, and Jiangsu mostly set their growth target at 5 to 5.5 percent. Less developed provinces predicted growth between 6 and 7 percent. The Covid pandemic and commodity shortages are expected to continue to weigh on economies across the country this year. Only Gansu in China’s northwest expects a higher growth compared to 2021; Inner Mongolia expects a steady growth rate. The southern island province of Hainan has set the highest target at 9 percent, followed by Tibet at 8 percent.

Provincial growth targets are published each year in advance of the National People’s Congress. During the NPC plenum in March, the premier announces the approximate growth target for all of China, which is at least partly fed by these forecasts. In 2021, China’s gross domestic product grew by 8.1 percent. Tianjin was the only one of the 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and non-government cities not to submit a forecast, according to Caixin. The port city is currently fighting a local outbreak of the Omicron variant. ck

About two months before the parliamentary elections in Hungary, the opposition has scored a success in its planned referendum on an offshoot of China’s Fudan University in Budapest. More than the 200,000 signatures needed for the referendum had been gathered, the mayor of the Hungarian capital, Gergely Karácsony, announced via social media. The citizens of Budapest will be asked whether they want to repeal a law allowing the construction of the Fudan campus.

The controversial Fudan project in Budapest had recently also made relations between China and Hungary an election issue (China.Table reported). The construction cost is estimated at around €1.5 billion. The majority, around €1.3 billion, is to be financed by a loan from a Chinese bank.

The National Electoral Authority (NVI) must now verify the signatures and set a date for the referendum. It has 60 days to do so. Budapest’s mayor attributed great symbolism to the referendum: “These signatures were collected not only because of a referendum,” Karácsony said – but also to restore confidence that politics “serves the public interest.”

The question remains whether the NVI Election Committee will schedule the referendum on the Fudan Campus during the parliamentary election on April 3. That is precisely what the opposition wants. But the organizers fear that Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s ruling right-wing Fidesz party will throw obstacles in the way – by playing for time. According to local media reports, the NVI has already announced that the counting of signatures will probably take the permitted 60 days. Critics immediately accused it of ties to Fidesz. ari

Concern over the unresolved fate of Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai has reached the Australian Open in Melbourne. Spectators at the Grand Slam tournament will now be allowed to wear T-shirts reading “Where is Peng Shuai?” after the organizers changed their stance on the matter. Over the weekend, the organizers had come under pressure after videos went viral: In them, security personnel forced spectators to take off such T-shirts. They also removed a Peng banner.

The organizers had initially insisted on tournament regulations banning clothing, banners, or signs with “promotional or political” content, according to a report by AFP. On Tuesday, CEO of Tennis Australia Craig Tiley said that people were now allowed into the stadium with clothing that could be interpreted as criticism of China’s handling of Peng Shuai – “as long as they are not coming as a mob to be disruptive but are peaceful.” Banners, however, would not be allowed to block anyone’s view of the matches.

Peng Shuai made a post on the Chinese online service Weibo in early November, accusing former Chinese Vice-Governor Zhang Gaoli of sexual assault. The post was quickly censored by Chinese authorities. Peng was not seen in public for nearly three weeks. Sports federations, the United Nations, and Western governments then expressed concern over the fate of the tennis star. Since then, the former world number one in doubles has been seen several times – including giving a television interview in Singapore. However, her situation remains unclear. Foreign countries therefore continue to worry about Peng’s well-being. The Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) has suspended its tournaments in China for the time being in protest.

China’s foreign office spokesman Zhao Lijian unsurprisingly criticized a “politicization of sports” in light of the videos on Monday. He said there was “no support whatsoever” for such protests. But that’s not entirely true. For example, 18-time Grand Slam tournament winner Martina Navratilova accused Australian Open organizers of “capitulating” to China. ck

The Coronavirus has long been considered the main threat to the Beijing Winter Olympics. Now a well-known problem has been added: air pollution in the Chinese capital. Thick smog has hung over Beijing for days; particulate matter (PM2.5) levels exceed 200 micrograms per cubic meter. The WHO recommends a level of 5 or less. Now, the Ministry of the Environment warned of persistently unfavorable weather conditions. These are typical for the transition from winter to spring, said ministry spokesman Liu Youbin. Only strong northern winds clear the winter air over Beijing; these currently do not seem to be in the forecast for the near future.

The ministry announced temporary emergency measures in Beijing and the neighboring province of Hebei in case the likelihood of severe air pollution increases during the Olympics. It said companies and vehicles with high emissions, for example, would be “managed and controlled.” The measures should have minimal impact on the economy and society, Liu said – especially on people’s livelihoods, power supply, household heating, and health care. The Games will be held from February 4 to 20.

In 2021, the capital announced that it had fully met national air quality standards for the first time. The city’s annual average PM2.5 concentration fell to 33 micrograms per cubic meter last year. That represented a 63.1 percent drop from 2013. Since Beijing won the bid to host the Winter Games in 2015, authorities have raised emissions standards for cars, closed dirty factories, and cut coal consumption. But it seems the problem is still far from over. ck

The European Commission continues to look for ways to ban imports of products made from forced labor. Sabine Weyand, Director-General for Trade from the EU Commission, rejects the approach by US authorities. The US model, which combines product-specific bans with origin bans, is “not effective,” Weyand told the European Parliament’s trade committee Tuesday. In China’s case, for example, cotton products linked to Xinjiang, but also products from Xinjiang in general, would be targeted.

The United States follows the basic assumption that all goods from Xinjiang involve forced labor. Importers are obligated to disprove this. This is a “heavy burden,” says Weyand. Under the relevant forced labor section of the US Tariff Act, US Customs is allowed to inspect and block imports for forced labor. Weyand sees this as a potential bureaucratic nightmare for EU customs processing. As an alternative, she advocated including a ban on imports of forced labor products in the planned EU Supply Chain Act. Independent legislation like that in the US would also require more time.

The EU supply chain law is to be presented on February 15. However, the EU Commission has not yet internally agreed on whether products from forced labor should be included (China.Table reported). Time could run short.

Bernd Lange, Chair of the European Parliament’s Committee on International Trade, criticized the internal disagreements of the EU Commission. “It is unfathomable that an internal body meeting in secret is slowing down the EU Commission – and thus putting off the European Parliament and the EU member states for almost a year,” Lange said. “At the latest after the State of the Union speech, in which Commission President Ursula von der Leyen promised to take decisive action against forced labor, there should have been momentum in the EU Commission.” The EU Commission chief had announced an import ban in September (China.Table reported). The presentation date for the EU supply chain law has already been postponed several times since spring 2021. ari

As in 2008, when Beijing hosted the Summer Games for the first time, the Chinese public will again be left disappointed by the external effects of the Games. After all, even then, the world press was more interested in China’s human rights violations and environmental sins than in the bright side of China’s economic miracle and the many gold medals won by Chinese athletes. The Middle Kingdom felt unfairly treated and many of its citizens were deeply offended. This year, there is a risk of an exacerbated repetition of mutual disappointment.

Let’s remember 2008: Just a quarter of a year before the Beijing Games, a devastating earthquake had caused widespread destruction in the west of the country and claimed many lives. The Summer Games offered the entire nation a chance to forget these traumatic events for a while and, as a proud host, to present the impressive results of its economic growth to the whole world.

The fact that the Games failed to bring China glory, fame, and more international respect was felt like a blow to the country’s image. This led to a rethinking of international communication in Beijing. In retrospect, the 2008 Olympic Games were a turning point in international relations with China.

Back then, most nations were battling the effects of the great economic and financial crisis that had erupted the year before – and which would spread and deepen even further around the world after the collapse of the US investment bank Lehman Brothers in September 2008. China, as it turned out a short time later, was one of the few countries that came through this economic and financial crisis unscathed in comparison. This was mainly because China’s economy and its financial sector were better protected from international influences than those of other countries. The fact that the Chinese government was able to use the opportunities of the global crisis to its own advantage at the time – in stark contrast to the USA, for example – gave it new legitimacy for its claim to power in the eyes of the Communist Party. At the same time, national self-confidence surged.

At first, Beijing tried to underpin its new power by developing a soft power strategy that would also improve China’s image in the world. But the Chinese government’s advances did not achieve the desired result: Its desire for respect and recognition among the international community did not match the way it dealt with dissidents in its own country. It lacked credibility and the lifestyle it wished to export lacked the necessary appeal.

As valid as the reasons for the West’s lack of sympathy were: They amplified the sense of disappointment. This did not remain without consequences. From around 2009 onward, the Chinese government’s tone toward the outside world became harsher. Beijing was exhilarated by its new power and frustrated by a declining yet arrogant America and a weak Europe. At the same time, it was also frustrated by its continued poor reputation in the world. The international community was suddenly talking about China’s arrogant demeanor. The confident appearance of Chinese diplomats and other representatives of the nation was indeed new. It unsettled and baffled the West.

With Xi Jinping’s rise to the top of the party and state in 2012 and 2013, China has evolved from an authoritarian to a totalitarian system. Beijing detains millions of Uyghurs in re-education camps in Xinjiang and deprives Hong Kong people of rights and freedoms that were once firmly assured. Xi has snuffed out the civil society that developed in the mid-2000s with the spread of the Internet. Today, the highly equipped censorship apparatus can hardly be overcome or circumvented by anyone in China.

This spared a large part of the Chinese population the humiliation of negative foreign media reports. However, it is to be expected that the Chinese government will filter, process, and repurpose these reports for propaganda purposes to provide its people with evidence of the hostility of foreign powers. The narrative that the US and other democracies do not welcome China’s rise and want to keep it down will circulate through the Chinese press again in the coming weeks. It has become difficult for Chinese citizens to form their own opinion about the world. But that does not mean that the disappointment about the negative external image is solely controlled by the government – or could even be controlled.

China, whose economic, political, and military power has grown dramatically since 2008, leaves no doubt that it wants to exert more influence on global affairs in the future. One indicator of this is the New Silk Road Initiative. Beyond that, much remains unclear. What is clear, however, is that China’s popularity is declining rather than increasing. According to a 14-country survey of (Western) industrialized nations by the PEW Research Center, Beijing ranked at an all-time low with an average of 73 percent negative opinion of China in 2020.

On the one hand, Beijing constantly complains about China’s negative international image. On the other hand, the government does not seem to put much effort into improving its international image by changing its behavior, if only by adopting a new, more open, and conciliatory rhetoric – not only toward the outside world. Instead, it dispatches wolf-warrior diplomats to the front, promoting rather than mitigating the image of aggressive nationalism. After all, they want to be taken seriously.

No matter how you spin it, the global crises of our time can only be solved with China, not against it. But that requires facts, not fake news. It needs science. Science thrives only in freedom, and that requires liberal democracy. The majority of international journalists who will be covering the Winter Games know this. That is why they will certainly write about China’s problems and contradictions again. If the government and its people have a hard time coping, then that is the price we have to pay in the name of our values.

Marc Bermann is a Management Consultant in Muehlheim/Ruhr. Until 2020, he was a Program Manager at Mercator Foundation, where he played a key role in setting up the Merics research institute. At the Robert Bosch Foundation, he was in charge of the China area and, among other things, organized the German-Chinese media ambassador project. Bermann has a background in sinology and political science.

Stéphane Leroy is taking over sales for China and the Asia Pacific at Bombardier. Leroy has been with the Canadian aircraft manufacturer for 20 years. He has already spent eight years in Asia. Leroy will retain his position as Vice President, Sales, Specialized Aircraft.

Andy Jones is to become President for the Asia-Pacific market region at Swiss global security group Dormakaba. He succeeds Jim-Heng Lee, who has headed the Wetzikon-based group as CEO since January 1, 2022. Jones was most recently responsible for the Japan & Korea regions as Senior Vice President. His new place of work will be Shanghai.