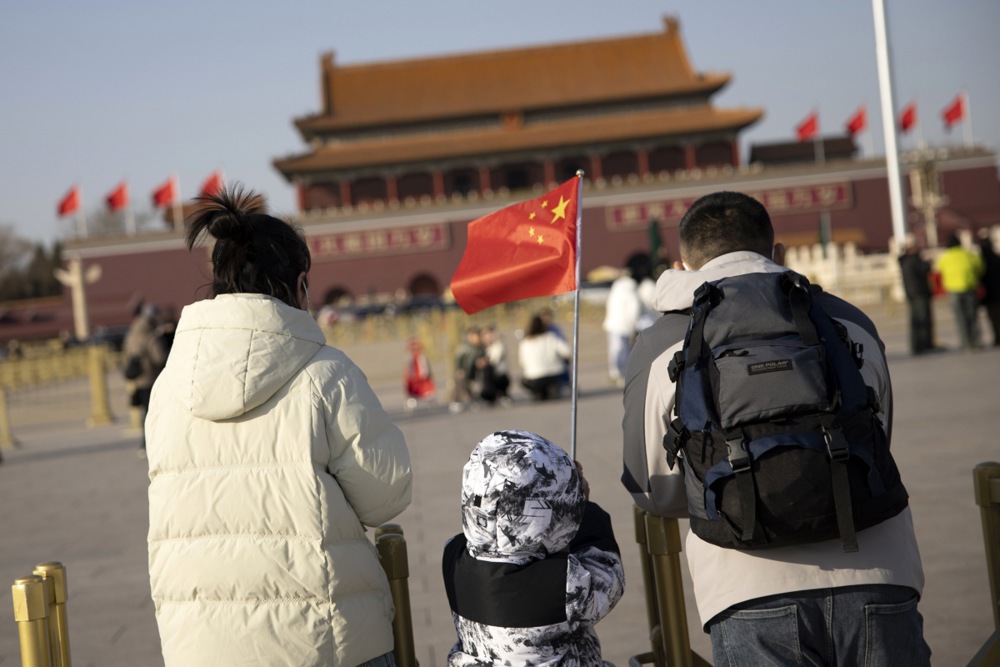

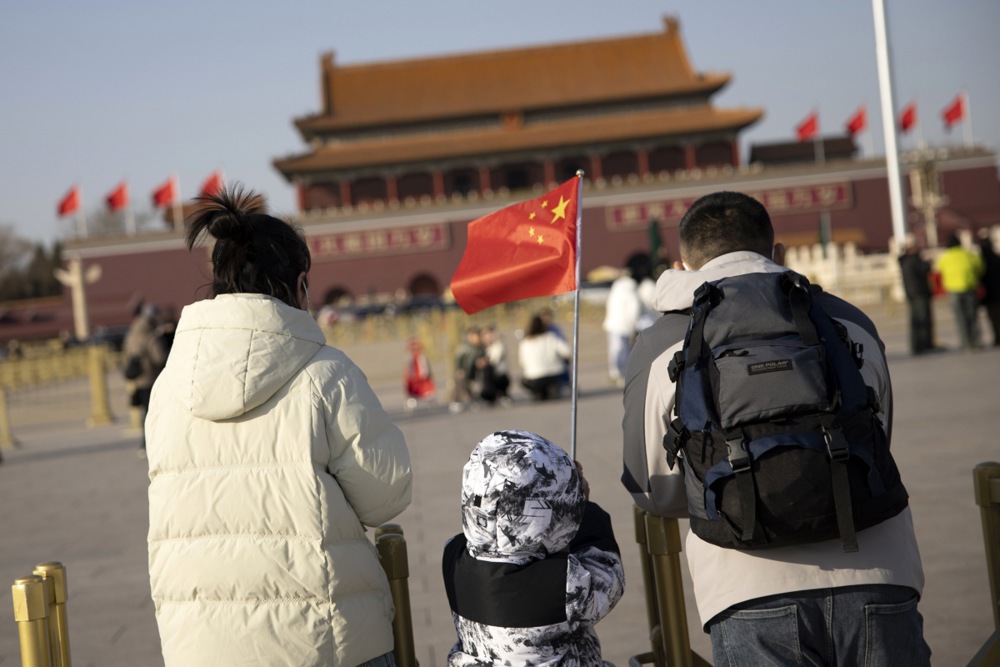

China’s highly focused session weeks begin. The annual “two sessions” kick off today with the advisory body, the Political Consultative Conference. Far more important signals come from the National People’s Congress, the parliament of the People’s Republic.

Premier Li Qiang has just reiterated that he and his government primarily consider themselves the executive body for the decisions of the Communist Party. However, the fact that the NPC publishes decisions made in back rooms in official form makes it one of the few windows into China’s opaque politics.

The economy is once again at the center of this year’s NPC. Although the economy slumps, experts expect the NPC to be more business-as-usual than huge economic stimulus package. Xi reportedly has a plan for how he wants to restructure the economy and align it more closely with the requirements of power politics. And he is sticking to this plan.

However, economic security is not just important to Xi Jinping, it is a global issue. And so, the EU Commission has put together an economic security package, combining trade and security issues for the first time. The new strategy is Brussels’ attempt to counter the influence of China and other countries on the European economy.

However, there have not been enough concrete plans to date, says Tobias Gehrke, a researcher at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), in an interview with Amelie Richter. According to Gehrke, a clear objective and an agenda for a comprehensive industrial and trade policy are needed, especially when it comes to raw materials.

Nearly 3,000 delegates will gather on Tuesday for the annual National People’s Congress (NPC). The difficult economic situation will take center stage. However, few expect any significant reforms or stimulus programs. There have been fewer clear signals in the run-up to the NPC than there have been for a long time – and what is known points to continuity. The directives for the NPC are likely to be fuelled directly by the ideas of state and party leader Xi Jinping himself.

Because Xi personally directs everything in China that he deems important. China’s economy is currently subordinate to his security policy priorities. “The priorities that Xi and the leadership have set will not change,” said Jacob Gunter, an economic expert at the China Research Institute Merics, at a webinar organized by the institute on the NPC last Friday.

For instance, Gunter does not expect any significant stimulus package to boost consumption. There will be some smaller measures in tax policy, monetary policy or to relieve the burden on low-income families – “but only marginally, to support and underpin the economic base.” Government money currently flows less to households, infrastructure and property – and more to the supply side of the economy, says Gunter: Into the modernization and expansion of industry. Neil Thomas and Jiang Qian from the Asia Society Policy Institute are convinced that Xi “is set on reorienting the economy away from a growth model driven by risky debt and rooted in the property market.”

Premier Li Qiang’s work report on Tuesday will likely provide the first signals about the future economic direction and, as always, will announce a growth target. The state newspaper China Daily confirmed the general expectations on Sunday: “It now looks increasingly likely that the growth will be set at ‘around 5 percent’.” This can be derived from the provincial targets, most of which are also around five percent again for 2024. Only Beijing, Liaoning, Tianjin, and Zhejiang have formulated higher growth targets for 2024 than for 2023.

“a higher target of around 5.5 percent would boost stimulus expectations,” write Thomas and Qian. But they do not expect such a move. According to China Daily, indicators such as the inflation target (three percent) and the budget deficit (three percent of GDP) will also not change compared to 2023. This all speaks against aggressive stimulus policies.

One of the few clear signals before the NPC came from Zhang Shanjie, Chairman of the important National Development and Reform Commission: Following visits to AI companies and research institutes, Zhang urged to “accelerate the high-quality development of our country’s artificial intelligence industry.” Thus, AI is likely to be a priority – as is a general focus on technological development.

The China Daily expects “a comeback in public housing projects” as part of support measures for the ailing property sector in 2024. The NPC could also provide details on consumption incentives, such as encouraging the exchange of old products for new ones or promoting “large-scale equipment modernization” in the manufacturing sector.

Last week, the equally state-owned Global Times reported that proposals to raise the retirement age will likely become a hot topic. Considering the aging of society, this is understandable, especially as Chinese people retire comparatively early.

Foreign observers always look closely at the defense budget. “At a time when the Chinese economy is not doing so well, defense spending will tell us a lot about the leadership’s priorities,” says Merics foreign policy analyst Legarda. Despite the poor economy, another increase of between six and seven percent would be a sign of concern about geopolitical risks.

Legarda expects a renewed commitment to stability as the main focus of foreign policy. Whether the NPC will toughen its rhetoric towards Taiwan remains to be seen. The plenum could appoint a new foreign minister to replace the interim minister Wang Yi.

Observers speculate that Liu Jianchao, the current head of the International Department of the Chinese Communist Party, could become the new foreign minister. His election could signal the desire for détente because, according to Legarda, Liu is no wolf warrior: “Beijing will use its openness, friendliness and competence to stabilize relations with countries in the West.”

Xi also signaled that climate action is climbing back up his list of priorities. At the last Politburo study session before the NPC last Thursday, he clearly emphasized the issue and highlighted the opportunities that the new economic sector around renewable energies or electric cars offered for China’s economy. According to Xinhua, Xi said “that it is imperative to set sights on the global frontiers of energy science and technology.”

Xi is sending “a very important signal,” says Nis Gruenberg, a policy analyst at Merics. He expects the NPC to include reminders to cadres to take climate action seriously – without a roadmap for the coal phase-out. He only expects concrete targets for phasing out coal in the 2026-2030 five-year plan.

Gunter believes that cadres at all levels will be looking to the NPC for signals that give them a sense of where Xi’s priorities lie. “If you look at the results of the Central Work Conferences, for example, all kinds of topics were summarized and everything seems to be a priority. However, this means that the cadres don’t know what they are supposed to prioritize.”

The EU Commission’s economic security package combines trade and security for the first time. This has never been done before. But isn’t the EU already too late?

I would say it’s late, but still in time. Many countries are just waking up. It is quite clear that the global economy is increasingly being defined by security interests. Specifically, this means that the superpowers USA and China are increasingly focussing on who innovates, who produces, who trades with which strategic capacities. This is not just a matter of ‘Who makes more money?’ but a clear security concern. The list of strategic capacities has been very narrowly defined in recent years. We have talked about dual-use goods primarily for weapons production. The list of strategic goods is growing. China is very openly and broadly defining strategic industries in which they intend to lead. Such leadership positions are of national security interest to China.

So it’s simply about control?

Yes, especially over certain technologies and supply chains. Who controls and who has access to them? This is increasingly considered to be the core of national security. It is now about pharmaceutical goods and certain energy technologies. Other sectors are constantly being added. As Europe, we cannot stay out of this. The EU Commission is already focussing on this industrial and technological battle with economic security. Perhaps more than some member countries.

And what happened so far?

The EU Commission defined the strategy last June and has virtually forged ahead. The staff around Commission President Ursula von der Leyen seized the issue and defined it very transatlantically. The comprehensive strategy drawn up last year was very ambitious. But not much has happened since then. There was an update and white paper in January. Last year, the Commission was still talking about significant economic security risks and the fragmentation of global trade chains. In the update, however, the strategy is now very much centered on narrowly defined risks of some technologies and how these threaten to flow off.

Had you hoped for more than what has now been presented?

Yes, definitely. Unfortunately, we are vulnerable in many areas – often due to the reality that many of these areas fall under national competencies. When it comes to economic security, Europe is only as strong as its weakest link. This is currently the case with export controls, for example. The pressure on Europe to find a common position here is high. We are not really managing to question national competences here fundamentally. There is a lack of fundamental questions about how we actually work together in general as member states and the Commission on this issue. Various platforms are churned out ad hoc, where companies and member states then try to exchange ideas. However, there is no ambitious agenda to really create fundamentally new structures.

Was there pressure to deliver something because of the upcoming European elections?

I think the pressure was pretty high. Even in the cabinet itself from the outset. However, the member states and companies had also warned from the start that the time was too short. In any case, I think there was political pressure for the current Commission to deliver something before the election. On the other hand, they wanted to avoid throwing everything into the balance in this super election year.

What does it take to implement the strategy? To a large extent, it consists of proposals that do not necessarily have to be implemented.

There is a lack of money and, above all, a lack of European resources. On top of that, we pledge ourselves to de-risking at some point. That sounds very good and everyone can sign up for it. But it’s also extremely undefined at the moment. What exactly does it mean? There must be a clear purpose. Which risks have priority? To this end, we need an agenda for a comprehensive industrial and trade policy, especially concerning raw materials.

What about the Critical Raw Materials Act, which aims to secure access to key raw materials such as copper or rare earths?

The Critical Raw Materials Act also has grand ambitions but no plan on how to achieve them. There are no clear EU instruments that could have an impact on this, for example, a fund at the European level. This also reflects the problem that the industrial policy instruments are all laid out at the national level – while the goals are actually all defined at European level. In my opinion, there is a clear need for European resources and strategic funds. Because without them, the EU Commission can only fiddle around with existing regulations, such as export controls or FDI screening. That is just not enough.

The once prominently discussed outbound investment screening will not happen for the time being. Can you explain why?

For starters, the outbound investment screening was a US agenda. Ursula von der Leyen defined her security strategy very transatlantically. She traveled to Washington for a meeting with Joe Biden and returned with a joint statement in which export controls, outbound investment screening and research security were central. But when it came to the issue of outbound, the Commission failed to clearly define in this short amount of time what Europe’s risk is. The outbound risks the Americans have defined may differ from ours.

What are the differences?

The main focus in Washington is on venture capital, which primarily transfers know-how to Chinese tech companies. We have different investment relationships with China, so we have to define our risk differently. And the second question is: How big is the risk really? And can our existing export control instruments not achieve the same thing in principle? These questions remain unanswered. The member states were highly skeptical about the whole thing anyway and put it on the back burner for the time being. But the matter is not over. I believe they also plan to wait and see how the Americans approach it, including after the US election.

Wouldn’t it have been better to wait and see instead of rushing it?

Yes, you could say that. We definitely need a clear risk definition and analysis. We need to prepare ourselves better and define our standards for risk investments. We are now taking a little more time and the January paper reflects this.

What impact do you expect this to have on European companies?

Naturally, companies always worry that restrictive measures such as export controls will spoil their business. But the actual threat is that we will fragment our export controls in Europe and that different standards will exist. Companies don’t want that either. One example are semiconductor machines from the Netherlands, which are now subject to different requirements than those of German suppliers. Or in the field of quantum technology, where new national export controls in Spain, Finland or France increase the risk of European fragmentation. Companies should certainly have an interest in this being regulated at the European level. Of course, there are still open questions about the balance between security, competitiveness and green transition – and the debate about solar panels and EVs from China, for example, is only just beginning.

How does China see all this?

China has not had the best experience of waging such trade conflicts and then escalating them politically. I think the sanctions on European MPs, for example, were really detrimental to China. They have had very negative consequences for China’s reputation.

What could we conclude from this?

Beijing is more likely to resort to tried and tested practices: Putting politically important and politically well-connected companies through the wringer. For example, French wine exporters or European car manufacturers in the People’s Republic. Or with its own targeted export controls, such as last year’s measures against gallium and germanium exports. But I don’t think China is currently interested in escalating things. We also have some breathing room because China needs us as an export market.

Tobias Gehrke is a Senior Policy Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, based in the Berlin office. He covers geoeconomics, focusing on economic security, European economic strategy, and great power competition in the global economy. Before joining ECFR, Gehrke was a research fellow with the Egmont Royal Institute in Brussels from 2017 to 2022, where he covered geoeconomics. He has also been a visiting fellow at the National University of Singapore, the University of Nottingham, and the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies at Johns Hopkins University, Washington DC. He holds a PhD in political science from Ghent University.

Shortly before today’s meeting of China’s top advisory body, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), its Deputy Secretary-General Zhang Xiaoming was unexpectedly dismissed. State broadcaster CCTV reported this on Sunday without providing any details. He had served in the position since 2022. The change was part of a “series of normal reshuffles,” a Hong Kong delegate of the National People’s Congress (NPC) told the South China Morning Post. Zhang is 60 years old, meaning that his removal cannot have been due to age.

Zhang spent over three decades as Beijing’s representative in Hong Kong, where he had always taken a tough stance against the city’s dissidents. During the major protests in the special administrative region in 2019 and the landslide election defeat for pro-Beijing party candidates, he was director of the central government’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office (HKMAO). He was demoted to vice director in 2020 as a result of these events and was succeeded by the current director, Xia Baolong. ck

Vice President Han Zheng has pledged to continue to open up more industries to foreign investment and create a market-oriented and law-based international business environment. “China’s development successes have been achieved through opening up,” he said at an American Chamber of Commerce in China (AmCham) banquet on Friday, “We will unswervingly adhere to a high degree of opening up to foreign countries.”

Vice President Han Zheng has pledged to continue to open up more industries to foreign investment and create a market-oriented and law-based international business environment. “China’s development achievements have been made through opening up,” he said at an American Chamber of Commerce in China banquet, according to the news agency AP. “We will unwaveringly adhere to a high level of opening-up to the outside world.”

Chamber officials said Han’s appearance at the annual dinner was a positive signal that the government is serious about addressing the concerns of American and other foreign companies about operational uncertainties and other challenges in the Chinese market.

Last week, Premier Li Qiang and Commerce Minister Wang Wentao received a delegation from the US Chamber of Commerce. Sean Stein, Chairman of AmCham in China, said that he had the impression that the Chinese side wanted to reassure them that there were still some things on the to-do list that they would take care of. Progress has been made in some areas but not in others, Stein said. ck

BYD is in the process of tapping into the European market while also planning an expansion in Japan. BYD plans to launch three more EV models in Japan by 2026, China’s electric market leader announced on Friday. “Our participation is changing the nation’s auto industry,” Liu Xueliang, BYD’s Head of Sales Asia-Pacific, told Nikkei Asia.

Japan is the world’s fourth-largest car market, still dominated by traditional car manufacturers. In the early stages of the sector’s transformation, Japan, particularly Toyota, focused on hybrids rather than all-electric cars. Most Japanese consumers favor domestic car brands.

BYD only entered the Japanese car market in 2023, and so far exclusively with electric models. It first launched the Atto 3 electric crossover – also available in Europe – followed by the Dolphin compact electric hatchback. In June, BYD’s first electric premium model, the Seal, will be launched on the Japanese market. “We want to further accelerate momentum and enlarge our business,” said Atsuki Tofukuji, President of BYD Japan, to journalists in Tokyo. However, sales remain relatively low. 1,700 BYD cars have been registered in Japan so far.

In the fourth quarter, BYD overtook Tesla as the world’s largest EV manufacturer for the first time. The company plans to use its own cargo ships to simplify logistics. Last Monday, shipping containers with 3000 BYD cars landed in Bremerhaven. ck

Tesla presented new purchase incentives for potential customers of its electric cars in China on Friday. Customers who buy a Model 3 saloon or a Model Y SUV by the end of March are eligible for up to 34,600 yuan (just over 4,400 euros), Tesla announced on Weibo. The incentives will also include a discount of 8,000 yuan with car insurance companies that work with Tesla and a discount of 10,000 yuan if the buyer opts for a new paint job. Tesla is also offering limited-time preferential financing plans that can save up to 16,600 yuan on Model Y purchases.

In light of disappointing sales figures, a severe price war is raging in China’s car market, which was triggered not least by Tesla itself. Yet EV sales in China rose by a fifth to over five million vehicles in 2023. As a result, their share of China’s overall market rose from 21 percent in 2022 to 24 percent in 2023. By comparison, the share of electric cars in Europe was 15 percent. rtr/ck

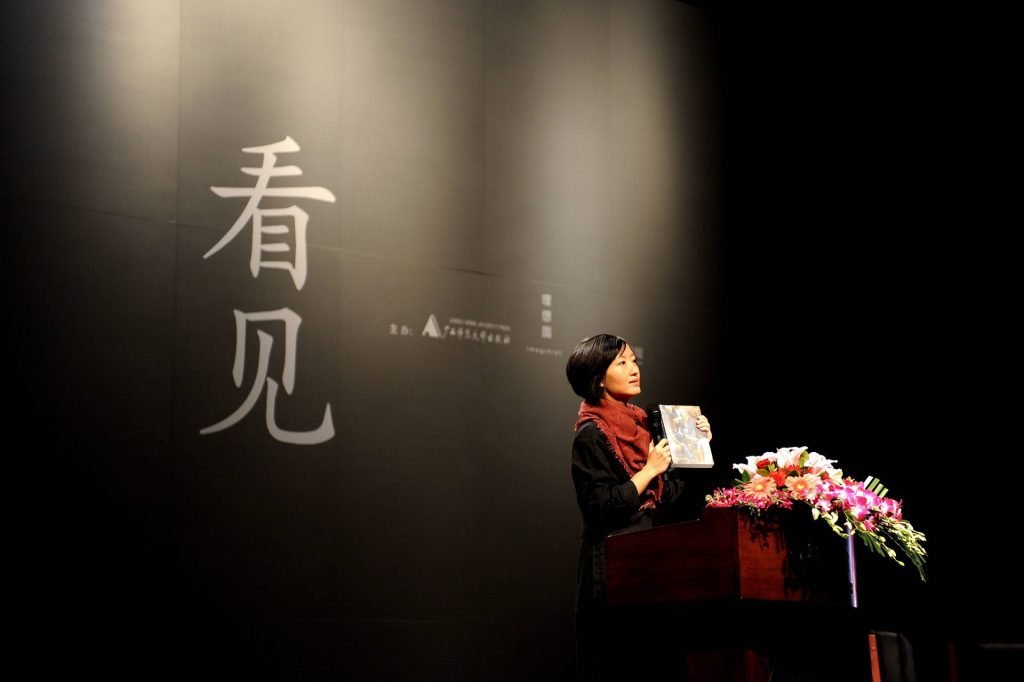

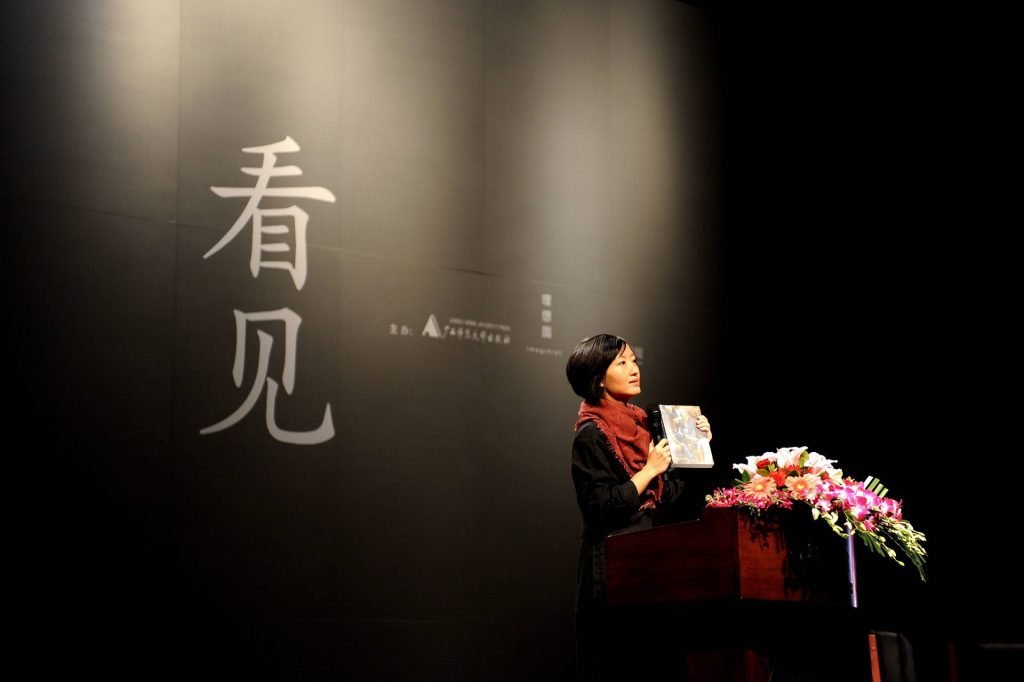

A look at Chai Jing’s past achievements gives an idea of how fundamentally China’s news world has changed in recent years. Looking back, many consider the 2000s the golden era of Chinese journalism. At the time, Chai Jing was the host of the investigative TV show “Xīnwén diàochá” (新闻调查) and a series of other formats on Chinese state television CCTV. She reported on social grievances in the rapidly developing Chinese society.

Chai Jing had a modest upbringing in Shanxi province and hosted her first show on a local news channel at the age of 19. While studying in Beijing, Chen Meng, an editor at Chinese state television CCTV, offered her the opportunity to create her own news program – under much freer conditions than today’s propaganda television.

One of Chai Jing’s first shows covered the SARS outbreak in 2002, the displacement of residents in the wake of China’s urbanization surge, the devastating AIDS epidemics in villages in Henan province that were covered up for years, and the authorities’ handling of the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan.

Some of her reports had surprising connections with Germany. Chai Jing reported on the fate of a generation of children who had hardly any contact with their migrant worker parents, based on the eyewitness account of a German volunteer. He had spent years in a community of so-called liúshǒu értóng (留守儿童 – left-behind children).

During the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, Chai Jing also reported on the personal story of Matthias Steiner, who won the Olympic weightlifting title for Germany. Chai Jing’s investigative reports and biographies are characterized by an empathetic view of individual fates, often pointing to overarching social problems.

In 2012, Chai Jing published her autobiographical book “Kànjiàn” (看見 – literally “seeing”), a collection of her journalistic reports. “The basis of understanding is experience,” she writes about her journalistic approach. The book attracted great attention as a critical study of society.

Soon after, Chai Jing left CCTV and produced her own documentary film, “Under the Dome,” about the rampant air pollution in China in 2015. To get to the root of the issue, Chai visited construction sites, power plants and steelworks, hospitals, gas stations and authorities throughout China. The film was viewed over 300 million times online within a week and was subsequently removed by the authorities.

Chai Jing’s split with the Chinese news world came in the early days of the government under Xi Jinping. After growing hostility – including the accusation that she had flown to the USA for the birth of her daughter – she withdrew from the public eye. Her work was not completely censored, but officials criticized her as unpatriotic. Shortly after her documentary film was removed, Chai Jing moved to Barcelona with her family.

After that, it was quiet around Chai Jing for a long time. But in August 2023, her book “Seeing” was published in English. She also released a series of short reports on radical Islamism in Europe on her YouTube channel, motivated by her experience of the 2017 jihadist terrorist attacks in Barcelona.

For some months now, Chai Jing has increasingly been commenting on current events in China, such as the death of former Premier Li Keqiang. She regularly reaches hundreds of thousands of people with her videos (some with English subtitles).

The circle of Chinese media professionals outside the control of the Communist Party state has grown in recent years. This circle includes exile activists as well as representatives of historically grown overseas Chinese communities. They are united by the desire to create independent sources of information and, in the face of increasing state repression, to keep the ideal of free reporting alive in the Chinese public sphere. Chai Jing is now one of their most important voices. Leonardo Pape

Veerle Nouwens has been appointed Executive Director of the International Institute for Strategic Studies Asia (IISS-Asia). In her new post, she will play a key role in Asia-Pacific research and the organization of the IISS Shangri-La Dialogue.

Melanie Miller has been Senior Manager Greater China, Japan and Korea at the IHK in Frankfurt am Main since February. Miller holds a Master’s degree in China Business and Economics from the University of Wuerzburg and studied in Qingdao and Beijing.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

This image from the Beijing Aerospace Control Centre looks like something straight from a science fiction flick. It shows Shenzhou 17 astronaut Tang Hongbo. The three-man crew on board the Chinese space station completed their second set of external activities in orbit on Saturday. Among other things, the astronauts performed maintenance on the station’s solar panels. They spent a total of eight hours outside the station.

China’s highly focused session weeks begin. The annual “two sessions” kick off today with the advisory body, the Political Consultative Conference. Far more important signals come from the National People’s Congress, the parliament of the People’s Republic.

Premier Li Qiang has just reiterated that he and his government primarily consider themselves the executive body for the decisions of the Communist Party. However, the fact that the NPC publishes decisions made in back rooms in official form makes it one of the few windows into China’s opaque politics.

The economy is once again at the center of this year’s NPC. Although the economy slumps, experts expect the NPC to be more business-as-usual than huge economic stimulus package. Xi reportedly has a plan for how he wants to restructure the economy and align it more closely with the requirements of power politics. And he is sticking to this plan.

However, economic security is not just important to Xi Jinping, it is a global issue. And so, the EU Commission has put together an economic security package, combining trade and security issues for the first time. The new strategy is Brussels’ attempt to counter the influence of China and other countries on the European economy.

However, there have not been enough concrete plans to date, says Tobias Gehrke, a researcher at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), in an interview with Amelie Richter. According to Gehrke, a clear objective and an agenda for a comprehensive industrial and trade policy are needed, especially when it comes to raw materials.

Nearly 3,000 delegates will gather on Tuesday for the annual National People’s Congress (NPC). The difficult economic situation will take center stage. However, few expect any significant reforms or stimulus programs. There have been fewer clear signals in the run-up to the NPC than there have been for a long time – and what is known points to continuity. The directives for the NPC are likely to be fuelled directly by the ideas of state and party leader Xi Jinping himself.

Because Xi personally directs everything in China that he deems important. China’s economy is currently subordinate to his security policy priorities. “The priorities that Xi and the leadership have set will not change,” said Jacob Gunter, an economic expert at the China Research Institute Merics, at a webinar organized by the institute on the NPC last Friday.

For instance, Gunter does not expect any significant stimulus package to boost consumption. There will be some smaller measures in tax policy, monetary policy or to relieve the burden on low-income families – “but only marginally, to support and underpin the economic base.” Government money currently flows less to households, infrastructure and property – and more to the supply side of the economy, says Gunter: Into the modernization and expansion of industry. Neil Thomas and Jiang Qian from the Asia Society Policy Institute are convinced that Xi “is set on reorienting the economy away from a growth model driven by risky debt and rooted in the property market.”

Premier Li Qiang’s work report on Tuesday will likely provide the first signals about the future economic direction and, as always, will announce a growth target. The state newspaper China Daily confirmed the general expectations on Sunday: “It now looks increasingly likely that the growth will be set at ‘around 5 percent’.” This can be derived from the provincial targets, most of which are also around five percent again for 2024. Only Beijing, Liaoning, Tianjin, and Zhejiang have formulated higher growth targets for 2024 than for 2023.

“a higher target of around 5.5 percent would boost stimulus expectations,” write Thomas and Qian. But they do not expect such a move. According to China Daily, indicators such as the inflation target (three percent) and the budget deficit (three percent of GDP) will also not change compared to 2023. This all speaks against aggressive stimulus policies.

One of the few clear signals before the NPC came from Zhang Shanjie, Chairman of the important National Development and Reform Commission: Following visits to AI companies and research institutes, Zhang urged to “accelerate the high-quality development of our country’s artificial intelligence industry.” Thus, AI is likely to be a priority – as is a general focus on technological development.

The China Daily expects “a comeback in public housing projects” as part of support measures for the ailing property sector in 2024. The NPC could also provide details on consumption incentives, such as encouraging the exchange of old products for new ones or promoting “large-scale equipment modernization” in the manufacturing sector.

Last week, the equally state-owned Global Times reported that proposals to raise the retirement age will likely become a hot topic. Considering the aging of society, this is understandable, especially as Chinese people retire comparatively early.

Foreign observers always look closely at the defense budget. “At a time when the Chinese economy is not doing so well, defense spending will tell us a lot about the leadership’s priorities,” says Merics foreign policy analyst Legarda. Despite the poor economy, another increase of between six and seven percent would be a sign of concern about geopolitical risks.

Legarda expects a renewed commitment to stability as the main focus of foreign policy. Whether the NPC will toughen its rhetoric towards Taiwan remains to be seen. The plenum could appoint a new foreign minister to replace the interim minister Wang Yi.

Observers speculate that Liu Jianchao, the current head of the International Department of the Chinese Communist Party, could become the new foreign minister. His election could signal the desire for détente because, according to Legarda, Liu is no wolf warrior: “Beijing will use its openness, friendliness and competence to stabilize relations with countries in the West.”

Xi also signaled that climate action is climbing back up his list of priorities. At the last Politburo study session before the NPC last Thursday, he clearly emphasized the issue and highlighted the opportunities that the new economic sector around renewable energies or electric cars offered for China’s economy. According to Xinhua, Xi said “that it is imperative to set sights on the global frontiers of energy science and technology.”

Xi is sending “a very important signal,” says Nis Gruenberg, a policy analyst at Merics. He expects the NPC to include reminders to cadres to take climate action seriously – without a roadmap for the coal phase-out. He only expects concrete targets for phasing out coal in the 2026-2030 five-year plan.

Gunter believes that cadres at all levels will be looking to the NPC for signals that give them a sense of where Xi’s priorities lie. “If you look at the results of the Central Work Conferences, for example, all kinds of topics were summarized and everything seems to be a priority. However, this means that the cadres don’t know what they are supposed to prioritize.”

The EU Commission’s economic security package combines trade and security for the first time. This has never been done before. But isn’t the EU already too late?

I would say it’s late, but still in time. Many countries are just waking up. It is quite clear that the global economy is increasingly being defined by security interests. Specifically, this means that the superpowers USA and China are increasingly focussing on who innovates, who produces, who trades with which strategic capacities. This is not just a matter of ‘Who makes more money?’ but a clear security concern. The list of strategic capacities has been very narrowly defined in recent years. We have talked about dual-use goods primarily for weapons production. The list of strategic goods is growing. China is very openly and broadly defining strategic industries in which they intend to lead. Such leadership positions are of national security interest to China.

So it’s simply about control?

Yes, especially over certain technologies and supply chains. Who controls and who has access to them? This is increasingly considered to be the core of national security. It is now about pharmaceutical goods and certain energy technologies. Other sectors are constantly being added. As Europe, we cannot stay out of this. The EU Commission is already focussing on this industrial and technological battle with economic security. Perhaps more than some member countries.

And what happened so far?

The EU Commission defined the strategy last June and has virtually forged ahead. The staff around Commission President Ursula von der Leyen seized the issue and defined it very transatlantically. The comprehensive strategy drawn up last year was very ambitious. But not much has happened since then. There was an update and white paper in January. Last year, the Commission was still talking about significant economic security risks and the fragmentation of global trade chains. In the update, however, the strategy is now very much centered on narrowly defined risks of some technologies and how these threaten to flow off.

Had you hoped for more than what has now been presented?

Yes, definitely. Unfortunately, we are vulnerable in many areas – often due to the reality that many of these areas fall under national competencies. When it comes to economic security, Europe is only as strong as its weakest link. This is currently the case with export controls, for example. The pressure on Europe to find a common position here is high. We are not really managing to question national competences here fundamentally. There is a lack of fundamental questions about how we actually work together in general as member states and the Commission on this issue. Various platforms are churned out ad hoc, where companies and member states then try to exchange ideas. However, there is no ambitious agenda to really create fundamentally new structures.

Was there pressure to deliver something because of the upcoming European elections?

I think the pressure was pretty high. Even in the cabinet itself from the outset. However, the member states and companies had also warned from the start that the time was too short. In any case, I think there was political pressure for the current Commission to deliver something before the election. On the other hand, they wanted to avoid throwing everything into the balance in this super election year.

What does it take to implement the strategy? To a large extent, it consists of proposals that do not necessarily have to be implemented.

There is a lack of money and, above all, a lack of European resources. On top of that, we pledge ourselves to de-risking at some point. That sounds very good and everyone can sign up for it. But it’s also extremely undefined at the moment. What exactly does it mean? There must be a clear purpose. Which risks have priority? To this end, we need an agenda for a comprehensive industrial and trade policy, especially concerning raw materials.

What about the Critical Raw Materials Act, which aims to secure access to key raw materials such as copper or rare earths?

The Critical Raw Materials Act also has grand ambitions but no plan on how to achieve them. There are no clear EU instruments that could have an impact on this, for example, a fund at the European level. This also reflects the problem that the industrial policy instruments are all laid out at the national level – while the goals are actually all defined at European level. In my opinion, there is a clear need for European resources and strategic funds. Because without them, the EU Commission can only fiddle around with existing regulations, such as export controls or FDI screening. That is just not enough.

The once prominently discussed outbound investment screening will not happen for the time being. Can you explain why?

For starters, the outbound investment screening was a US agenda. Ursula von der Leyen defined her security strategy very transatlantically. She traveled to Washington for a meeting with Joe Biden and returned with a joint statement in which export controls, outbound investment screening and research security were central. But when it came to the issue of outbound, the Commission failed to clearly define in this short amount of time what Europe’s risk is. The outbound risks the Americans have defined may differ from ours.

What are the differences?

The main focus in Washington is on venture capital, which primarily transfers know-how to Chinese tech companies. We have different investment relationships with China, so we have to define our risk differently. And the second question is: How big is the risk really? And can our existing export control instruments not achieve the same thing in principle? These questions remain unanswered. The member states were highly skeptical about the whole thing anyway and put it on the back burner for the time being. But the matter is not over. I believe they also plan to wait and see how the Americans approach it, including after the US election.

Wouldn’t it have been better to wait and see instead of rushing it?

Yes, you could say that. We definitely need a clear risk definition and analysis. We need to prepare ourselves better and define our standards for risk investments. We are now taking a little more time and the January paper reflects this.

What impact do you expect this to have on European companies?

Naturally, companies always worry that restrictive measures such as export controls will spoil their business. But the actual threat is that we will fragment our export controls in Europe and that different standards will exist. Companies don’t want that either. One example are semiconductor machines from the Netherlands, which are now subject to different requirements than those of German suppliers. Or in the field of quantum technology, where new national export controls in Spain, Finland or France increase the risk of European fragmentation. Companies should certainly have an interest in this being regulated at the European level. Of course, there are still open questions about the balance between security, competitiveness and green transition – and the debate about solar panels and EVs from China, for example, is only just beginning.

How does China see all this?

China has not had the best experience of waging such trade conflicts and then escalating them politically. I think the sanctions on European MPs, for example, were really detrimental to China. They have had very negative consequences for China’s reputation.

What could we conclude from this?

Beijing is more likely to resort to tried and tested practices: Putting politically important and politically well-connected companies through the wringer. For example, French wine exporters or European car manufacturers in the People’s Republic. Or with its own targeted export controls, such as last year’s measures against gallium and germanium exports. But I don’t think China is currently interested in escalating things. We also have some breathing room because China needs us as an export market.

Tobias Gehrke is a Senior Policy Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, based in the Berlin office. He covers geoeconomics, focusing on economic security, European economic strategy, and great power competition in the global economy. Before joining ECFR, Gehrke was a research fellow with the Egmont Royal Institute in Brussels from 2017 to 2022, where he covered geoeconomics. He has also been a visiting fellow at the National University of Singapore, the University of Nottingham, and the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies at Johns Hopkins University, Washington DC. He holds a PhD in political science from Ghent University.

Shortly before today’s meeting of China’s top advisory body, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), its Deputy Secretary-General Zhang Xiaoming was unexpectedly dismissed. State broadcaster CCTV reported this on Sunday without providing any details. He had served in the position since 2022. The change was part of a “series of normal reshuffles,” a Hong Kong delegate of the National People’s Congress (NPC) told the South China Morning Post. Zhang is 60 years old, meaning that his removal cannot have been due to age.

Zhang spent over three decades as Beijing’s representative in Hong Kong, where he had always taken a tough stance against the city’s dissidents. During the major protests in the special administrative region in 2019 and the landslide election defeat for pro-Beijing party candidates, he was director of the central government’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office (HKMAO). He was demoted to vice director in 2020 as a result of these events and was succeeded by the current director, Xia Baolong. ck

Vice President Han Zheng has pledged to continue to open up more industries to foreign investment and create a market-oriented and law-based international business environment. “China’s development successes have been achieved through opening up,” he said at an American Chamber of Commerce in China (AmCham) banquet on Friday, “We will unswervingly adhere to a high degree of opening up to foreign countries.”

Vice President Han Zheng has pledged to continue to open up more industries to foreign investment and create a market-oriented and law-based international business environment. “China’s development achievements have been made through opening up,” he said at an American Chamber of Commerce in China banquet, according to the news agency AP. “We will unwaveringly adhere to a high level of opening-up to the outside world.”

Chamber officials said Han’s appearance at the annual dinner was a positive signal that the government is serious about addressing the concerns of American and other foreign companies about operational uncertainties and other challenges in the Chinese market.

Last week, Premier Li Qiang and Commerce Minister Wang Wentao received a delegation from the US Chamber of Commerce. Sean Stein, Chairman of AmCham in China, said that he had the impression that the Chinese side wanted to reassure them that there were still some things on the to-do list that they would take care of. Progress has been made in some areas but not in others, Stein said. ck

BYD is in the process of tapping into the European market while also planning an expansion in Japan. BYD plans to launch three more EV models in Japan by 2026, China’s electric market leader announced on Friday. “Our participation is changing the nation’s auto industry,” Liu Xueliang, BYD’s Head of Sales Asia-Pacific, told Nikkei Asia.

Japan is the world’s fourth-largest car market, still dominated by traditional car manufacturers. In the early stages of the sector’s transformation, Japan, particularly Toyota, focused on hybrids rather than all-electric cars. Most Japanese consumers favor domestic car brands.

BYD only entered the Japanese car market in 2023, and so far exclusively with electric models. It first launched the Atto 3 electric crossover – also available in Europe – followed by the Dolphin compact electric hatchback. In June, BYD’s first electric premium model, the Seal, will be launched on the Japanese market. “We want to further accelerate momentum and enlarge our business,” said Atsuki Tofukuji, President of BYD Japan, to journalists in Tokyo. However, sales remain relatively low. 1,700 BYD cars have been registered in Japan so far.

In the fourth quarter, BYD overtook Tesla as the world’s largest EV manufacturer for the first time. The company plans to use its own cargo ships to simplify logistics. Last Monday, shipping containers with 3000 BYD cars landed in Bremerhaven. ck

Tesla presented new purchase incentives for potential customers of its electric cars in China on Friday. Customers who buy a Model 3 saloon or a Model Y SUV by the end of March are eligible for up to 34,600 yuan (just over 4,400 euros), Tesla announced on Weibo. The incentives will also include a discount of 8,000 yuan with car insurance companies that work with Tesla and a discount of 10,000 yuan if the buyer opts for a new paint job. Tesla is also offering limited-time preferential financing plans that can save up to 16,600 yuan on Model Y purchases.

In light of disappointing sales figures, a severe price war is raging in China’s car market, which was triggered not least by Tesla itself. Yet EV sales in China rose by a fifth to over five million vehicles in 2023. As a result, their share of China’s overall market rose from 21 percent in 2022 to 24 percent in 2023. By comparison, the share of electric cars in Europe was 15 percent. rtr/ck

A look at Chai Jing’s past achievements gives an idea of how fundamentally China’s news world has changed in recent years. Looking back, many consider the 2000s the golden era of Chinese journalism. At the time, Chai Jing was the host of the investigative TV show “Xīnwén diàochá” (新闻调查) and a series of other formats on Chinese state television CCTV. She reported on social grievances in the rapidly developing Chinese society.

Chai Jing had a modest upbringing in Shanxi province and hosted her first show on a local news channel at the age of 19. While studying in Beijing, Chen Meng, an editor at Chinese state television CCTV, offered her the opportunity to create her own news program – under much freer conditions than today’s propaganda television.

One of Chai Jing’s first shows covered the SARS outbreak in 2002, the displacement of residents in the wake of China’s urbanization surge, the devastating AIDS epidemics in villages in Henan province that were covered up for years, and the authorities’ handling of the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan.

Some of her reports had surprising connections with Germany. Chai Jing reported on the fate of a generation of children who had hardly any contact with their migrant worker parents, based on the eyewitness account of a German volunteer. He had spent years in a community of so-called liúshǒu értóng (留守儿童 – left-behind children).

During the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, Chai Jing also reported on the personal story of Matthias Steiner, who won the Olympic weightlifting title for Germany. Chai Jing’s investigative reports and biographies are characterized by an empathetic view of individual fates, often pointing to overarching social problems.

In 2012, Chai Jing published her autobiographical book “Kànjiàn” (看見 – literally “seeing”), a collection of her journalistic reports. “The basis of understanding is experience,” she writes about her journalistic approach. The book attracted great attention as a critical study of society.

Soon after, Chai Jing left CCTV and produced her own documentary film, “Under the Dome,” about the rampant air pollution in China in 2015. To get to the root of the issue, Chai visited construction sites, power plants and steelworks, hospitals, gas stations and authorities throughout China. The film was viewed over 300 million times online within a week and was subsequently removed by the authorities.

Chai Jing’s split with the Chinese news world came in the early days of the government under Xi Jinping. After growing hostility – including the accusation that she had flown to the USA for the birth of her daughter – she withdrew from the public eye. Her work was not completely censored, but officials criticized her as unpatriotic. Shortly after her documentary film was removed, Chai Jing moved to Barcelona with her family.

After that, it was quiet around Chai Jing for a long time. But in August 2023, her book “Seeing” was published in English. She also released a series of short reports on radical Islamism in Europe on her YouTube channel, motivated by her experience of the 2017 jihadist terrorist attacks in Barcelona.

For some months now, Chai Jing has increasingly been commenting on current events in China, such as the death of former Premier Li Keqiang. She regularly reaches hundreds of thousands of people with her videos (some with English subtitles).

The circle of Chinese media professionals outside the control of the Communist Party state has grown in recent years. This circle includes exile activists as well as representatives of historically grown overseas Chinese communities. They are united by the desire to create independent sources of information and, in the face of increasing state repression, to keep the ideal of free reporting alive in the Chinese public sphere. Chai Jing is now one of their most important voices. Leonardo Pape

Veerle Nouwens has been appointed Executive Director of the International Institute for Strategic Studies Asia (IISS-Asia). In her new post, she will play a key role in Asia-Pacific research and the organization of the IISS Shangri-La Dialogue.

Melanie Miller has been Senior Manager Greater China, Japan and Korea at the IHK in Frankfurt am Main since February. Miller holds a Master’s degree in China Business and Economics from the University of Wuerzburg and studied in Qingdao and Beijing.

Is something changing in your organization? Let us know at heads@table.media!

This image from the Beijing Aerospace Control Centre looks like something straight from a science fiction flick. It shows Shenzhou 17 astronaut Tang Hongbo. The three-man crew on board the Chinese space station completed their second set of external activities in orbit on Saturday. Among other things, the astronauts performed maintenance on the station’s solar panels. They spent a total of eight hours outside the station.