Despite the sanctions imposed on Russia following the attack on Ukraine, its most important export commodity is still flowing abroad unchecked. Europe also continues to purchase crude oil from Russia. However, while the EU wants to reduce its imports by 90 percent, China has now positioned itself as the most important buyer. In the spring, the country purchased around 1.6 million barrels of crude oil from Russia every day – and at hefty discounts, as Christiane Kuehl explains. With these imports, China primarily wants to replenish its strategic oil reserves. Once again, Beijing exploits global turmoil to its own advantage.

At the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles, US President Joe Biden actually wanted to show the unity between the United States and Latin America. Instead, the summit became proof of the US loss of power in the region – a loss that China in particular exploits and accelerates with targeted investments, as Frank Sieren writes. Not only is the People’s Republic the largest trading partner of Latin American countries, but it has also already incorporated many of them into Chinese-influenced institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Belt and Road Initiative. Common positions with the US, such as a joint condemnation of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, will thus be even more difficult, as the summit’s thin final paper proves.

Russia sells less oil to the EU and the USA. But the black gold is still flowing unchecked elsewhere. According to Russian statistics, the export volume, which initially collapsed as a result of the US embargo, has now returned to pre-war levels. President Vladimir Putin has Asia to thank for this: According to S&P Global, India imported around 20 times as much oil per day from Russia in April as the daily average for 2021 – at discount prices of up to $30 below global market prices (627,000 barrels per day). And China, too, after its initial reluctance, now seems to be negotiating more intensively with Russia about oil supplies – and at hefty discounts, too.

China buys Russian crude oil at a 35 percent discount from the current market price, Bloomberg recently reported, citing EU Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis. “What we are seeing, especially in this situation of Russia’s weakness, is that China is going to take good advantage of it,” Dombrovskis said. It would be less beneficial for Russia. Reuters reports about new oil contracts by various refiners, signed quietly behind the scenes.

China apparently does not want to make a big fuss about Moscow’s oil purchases, although there is currently no threat of secondary sanctions. The EU has also continued to buy Russian oil. It is possible that China is also trying out the balancing act between supporting Moscow and apparent neutrality in this field – in this case with a nice benefit for itself.

The EU wants to reduce its imports by 90 percent in response to Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia must therefore find other buyers. Since the global market price for crude oil has risen so sharply as a result of the embargos, Russia can afford to grant large discounts to friendly states. Russia still sells its oil at the equivalent of around $70 a barrel – more than before the war, but well below the current price for Brent crude oil of around $120 a barrel. Aside from China, India in particular, but also Turkey and some African states buy Russian oil at discount prices.

Russia will divert its oil to markets from which EU countries would buy it at a higher price, Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Nowak said at an event in May. Such announcements fuel the suspicion that China, for example, could become such a transshipment point for resold Russian oil – even if concrete indications of this are lacking so far.

China bought around 1.6 million barrels (bbl) of crude oil a day from Russia in the spring – making it the biggest buyer. Half of it – around 800,000 barrels per day – flowed to China through pipelines, government contracts or arrived by tanker. However, Reuters already expected an increase in Russian oil shipped to China by tankers to 1.1 million barrels a day in May

China’s imports, however, are led by Unipec, the trading arm of Sinopec, along with Zhenhua Oil, a unit of Chinese defense conglomerate Norinco, Reuters writes, citing traders, shipping data and a shipbroker’s report. According to the report, they are carrying more oil from Russia’s Baltic ports such as Ust-Luga as well as its Far East export hub Kozmino on the Pacific Ocean.

Unlike India’s state-owned oil refiners, which used public tenders to obtain Russia’s Urals crude oil, among others, China’s state-owned companies have been operating under the radar as much as possible, Bloomberg reported, citing traders. Chinese refiners have been constantly inquiring about possible shipments since March – including smaller independent refiners in Shandong. These were primarily interested in ESPO crude oil, named after the Russian Far East oil pipeline. The oil is then transferred to tankers in two Siberian ports and shipped to its destinations.

Technically, it is far easier to divert shipments by tanker than pipeline oil. But transportation is not the only problem here. Oil refineries are often designed to process certain types of crude and usually cannot turn over large volumes in a short time. Also, some commodity traders who have previously brokered Russian crude are dropping out. Two of the world’s largest commodity traders, Vitol and Trafigura, stopped buying from Rosneft, Russia’s largest oil producer, in mid-May. This hits India’s state-owned refiner Bharat Petroleum, for example. It recently bought two million barrels of Russian Urals oil from Trafigura, which were shipped in May. Glencore is also withdrawing from its Russian business. It is uncertain whether any alternative commodity markets will emerge so quickly in this environment.

Instead of letting Russian oil seep onto world markets, China is using it to build up onshore storage tanks for future emergencies, reports the Washington Post. China does not disclose the volume of its crude oil reserves, but there are estimates based on satellite imagery, for example. Bloomberg experts estimate China’s storage capacity for commercial and strategic oil reserves at over one billion barrels. There is still plenty of room to keep stockpiling, Bloomberg quoted Jane Xie, senior oil analyst at data and analytics firm Kpler, as saying. “It would be a good opportunity to do so if they can be procured on economically attractive terms.”

But that is merely only a momentary observation. The war will drag on. And of decisive importance for the global oil market will be whether Russia can win over ships and intermediaries as well as buyers. For now, China appears to be dealing directly with Russia, without intermediaries. For example, Shandong Port Group rented the tanker Kriti Future to transport oil from Kozmino to China in June, according to Bloomberg. The company has close ties to oil refineries in the Shandong province.

But for any resale, China might already need other players willing to touch Russian oil. Bloomberg, citing port agencies, lists several smaller companies that have stepped up since the war began. Litasco SA, a unit of Moscow-based producer Lukoil PJSC has become the largest handler of the Urals type, according to the report. Livna Shipping in Hong Kong is also new to the business. According to vessel-tracking data from Vortexa and Refinitiv, Livna has shipped more than seven million barrels of Russian crude to China since late April. Also emerging is a Geneva-based company with the curious name Bellatrix – an evil sorceress from the Harry Potter saga.

Like US President Joe Biden’s trip to Asia in May, last week’s 9th Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles was also marked by a loss of US political power in favor of China. The Washington Post calls the summit a “dud”.

Even before it started, things were not looking too bright for the summit: Biden had categorically ruled out the participation of authoritarian states such as Nicaragua, Cuba and Venezuela. In response, however, several democratically elected heads of government also canceled their participation, including Andrés Manuel López Obrador, President of Mexico, the US’s largest trading partner in Latin America. Xiomara Castro of Honduras, who was just recently elected, also declined to attend. The conservative President of Guatemala, Alejandro Giammattei, who was elected by a large majority in 2019, stayed away, as did Nayib Bukeles, the President of El Salvador. But government representatives of these countries were still present.

Brazilian right-wing nationalist President Jair Bolsonaro, a Donald Trump supporter, arrived after some hesitation, but beforehand publicly questioned whether Biden had actually won the US election. Argentina’s President Alberto Fernández, who leads a center-left electoral alliance, also attended the summit, but criticized that the United States hosting the Summit of the Americas “does not give the possibility to impose an admission right“.

Biden unsuccessfully tried to strike a different tone: They had come together to “demonstrate to our people the incredible power of democracies”. What was demonstrated, however, was above all the waning influence of the United States in the region. Among other things, Washington’s goal at the summit was to find a common USA and Latin American position on Russia and China. However, neither country is mentioned in the final declaration.

In his speech, Fernández made it clear that his position on Ukraine was more in line with Beijing’s than Washington’s: “It is urgent to build negotiation scenarios that will end the catastrophe that is war, without any humiliation or desire for domination,” Fernández said in a pointedly neutral manner. However, the Argentine President certainly had Argentine interests in mind: At the beginning of 2021, Argentina became part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As part of it, China wants to invest $24 billion in Argentina. This is good news for a country that only recently received a $44 billion bridging loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Similarly, many Latin American politicians are disgruntled that Biden gets a $40 billion aid package from Congress for the Ukraine war, but not $4 billion for the social crisis in Central America.

China’s investments are making it increasingly easy for Latin American countries to break away from the United States. China has long been South America’s largest trading partner. Ten years ago, trade with Latin America and the Caribbean was worth just $18 billion; today it is worth almost $450 billion. By 2035, it could be as much as $700 billion, experts estimate.

“When US authorities visit Latin America, they often talk about China and why Latin American countries should not deal with China,” says Jorge Heine, a Stanford-educated former Chilean minister with the left-liberal PPD. “When Chinese authorities visit, all the talk is about bridges and tunnels and highways and railways and trade.”

Not only does China lead by a wide margin when it comes to trade, but also in company investments and acquisitions. While the rest of the world invested a total of $44 billion in South America’s economy between 2017 and 2021, $328 billion came from China.

More than 70 percent of the investments go to the energy and electricity sector. The Chinese energy company State Grid supplies electricity to more than ten million people in Brazil alone. Chinese companies generate and distribute around twelve percent of the electricity in Brazil.

And Chinese investment is flowing into other sectors as well: The People’s Republic invested $73 billion in South America’s natural resources sector between 2000 and 2018. $4.5 billion flowed into lithium production in Mexico, Bolivia and Chile. A consortium led by Chinese companies is also building the subway in the Colombian capital Bogotá by 2028 and will operate it for 20 years. Institutionally, Beijing also has a lot to offer: Peru has been a member of the China-initiated Asian Development Bank (AIIB) since January. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador and Uruguay are already members. Founded in 2015, the global institution aims to finance infrastructure projects in the style of the World Bank – gladly including those that are part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). More than 20 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are already members of the BRI.

Last September, Daleep Singh, one of the U.S. Deputy National Security Advisors was on a promotional tour under the slogan “Build Back Better World” to offer socially responsible U.S. infrastructure financing as a counterweight to China: Transparent, sustainable and with proper labor standards. However, interest was low. At least the US has lent Ecuador $3.5 billion in the past year – under the condition that the country abandons certain Chinese technologies. Ecuador, however, is indebted to China to the tune of five billion. But that is just eleven percent of the country’s total foreign debt. The situation is more dramatic in Venezuela, which owes China $50 billion. Like Ecuador, it repays its debts with oil.

Economically, the US can no longer “match the deep pockets of Chinese investment bank,” fears Cynthia Arnson, Director of the Latin America Program at the Washington-based Wilson Center and a leading US South America specialist: “We have to come up with alternatives.”

Sinolytics is a European consulting and analysis company specializing in China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

A new study suggests that private creditors, not Chinese loans, dominate African debt. In their paper, Harry Verhoeven of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University and Nicolas Lippolis of the University of Oxford’s Department of Politics and International Relations object to the “debt trap diplomacy” narrative (China.Table reported). “What keeps African leaders awake at night is not Chinese debt traps. It is the whims of the bond market,” the report says. China is admittedly the continent’s largest bilateral creditor. But most of the debt is owed to private Western lenders, according to the researchers.

“[Chinese debt] is not the most rapidly growing segment of debt. Other credit lines have grown a lot more in recent years, especially those,” said Verhoeven, co-author of the report “Politics by Default: China and the Global Governance of African Debt”.

“These are bondholders, people from London, Frankfurt and New York who are buying African debt. That segment in the last couple of years has grown much faster than any liabilities that African states owe other creditors.”

The report cited internal estimates from international financial institutions. Sub-Saharan African sovereign debt owed to Chinese companies amounted to around $78 billion at the end of 2019. That represented about eight percent of the region’s total debt, which amounted to about $954 billion. Debt to China accounted for about 18 percent of African countries’ external debt, according to the study.

It is estimated that Beijing has lent about $150 billion to African countries since 2000, mainly through the China Exim Bank. “This is a substantial amount, but not large enough to have been the main driver of debt accumulation since 2004-05,” the study says. According to the paper’s data, the debt is concentrated in five countries: Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Zambia. “The idea that Chinese debt traps jeopardize the entire continent is hyperbolic,” the study says. ari

Taiwan’s chip industry has invested around 120 billion US dollars in the construction of new semiconductor factories. This is according to research by the Japanese newspaper Nikkei.Asia. 20 new factories are currently under construction or have recently been completed. These include three factories producing chips in the latest 3 nm process. These production facilities alone each cost over $10 billion.

Taiwan is the undisputed global market leader in the manufacturing of semiconductors. Taiwanese manufacturers hold a combined market share of over 90 percent for modern semiconductor components. The massive investments will enable Taiwan to further consolidate its market dominance. TSMC is also building two factories overseas, one in Arizona, USA and one in Kumamoto Prefecture in Japan, which will cost $12 billion and $8.6 billion respectively. nib

Semiconductor production in China is being disrupted as a result of the trucker strike in South Korea. According to Reuters, a South Korean company that produces isopropyl alcohol (IPA) on a large scale for cleaning semiconductor chips could not ship its product to China because of the blockade. According to Korea International Trade Association (Kita), the export of 90 tons of IPA, which is said to be equivalent to about a week’s supply, has been delayed.

“Followed by auto chip shortages and global shipping issues over the Russia-Ukraine war, the price of raw materials has already soared to the top level,” Yoon Kyung-sun of the Korea Automobile Manufacturers Association said at a press conference held jointly with Kita on Tuesday.

South Korea is a major supplier of semiconductors, smartphones, cars, batteries and electronic goods. Since June 7, 22,000 truck drivers have been protesting in South Korea due to a sharp rise in fuel prices. They demand higher wages and a minimum wage guarantee. Supply chains around the world, which have become fragile as a result of lockdowns and supply bottlenecks, are thus once again coming under pressure. niw/ rtr

The security pact signed between the Solomon Islands and China should be reviewed by the regional Pacific Islands Forum. This was demanded by the prime ministers of Samoa and New Zealand in a statement on Tuesday. The Pacific Island Countries Consultative Forum is scheduled to meet in Fiji in mid-July.

Beijing is trying to expand its influence in the region and most recently signed a security pact with the Solomon Islands, upsetting the US, Australia and New Zealand (China.Table reported). Speaking to China.Table, Malcolm Davis, an analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra, said that “China could extend its military presence far into the Southwest Pacific through diplomatic means, in a way that threatens Australia, New Zealand and the United States”.

Collin Beck, a top Solomon Islands diplomat who helped draft the pact, stressed in an interview with The Guardian that the Solomon Islands had no intention of allowing China to establish a permanent military presence in the country. “It has nothing to do with the establishment of a military base,” Beck said.

China also rejects criticism of the proposed pact. It says the agreement poses no military threat and that closer ties between China and the Solomon Islands would benefit everyone. Beijing is promoting a regional agreement with nearly a dozen Pacific countries that would consolidate cooperation in areas such as security and data communications. niw

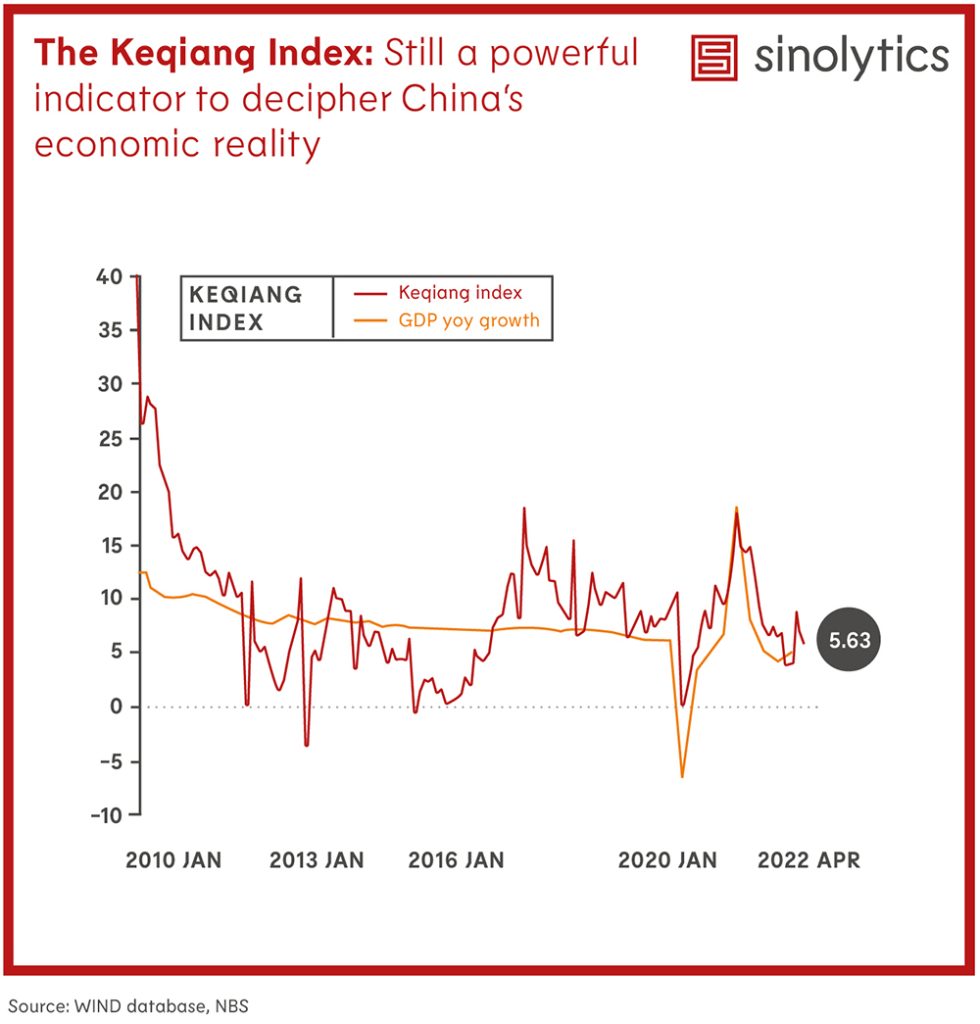

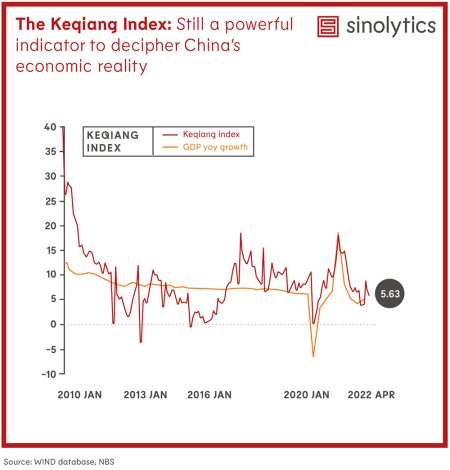

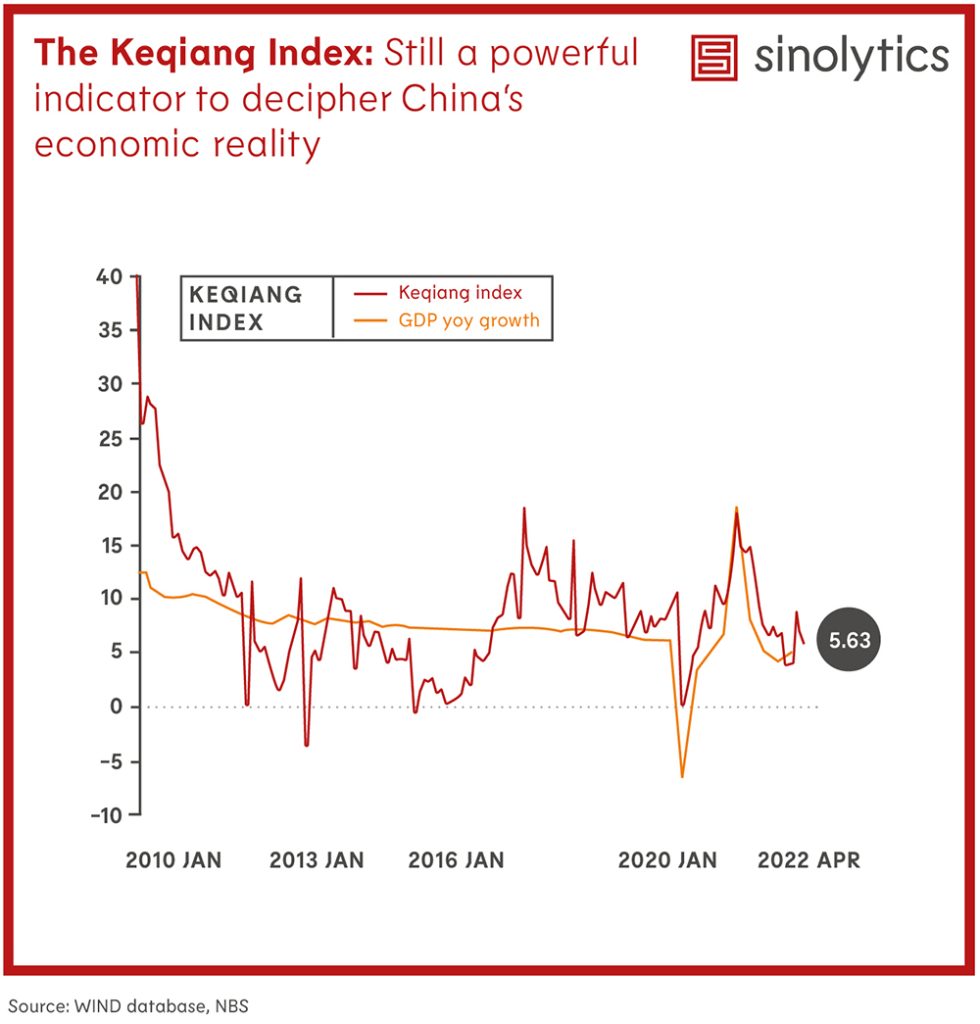

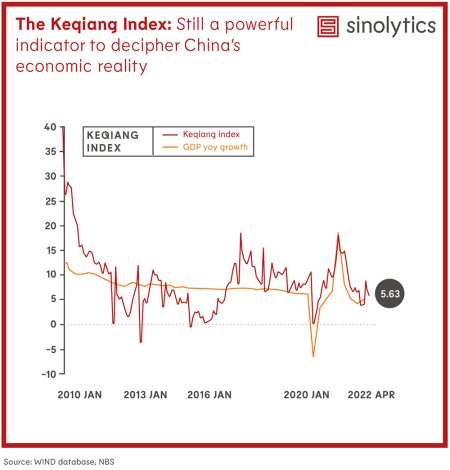

At this year’s annual meeting of the National People’s Congress in early March, Premier Li Keqiang announced China’s GDP growth target of 5.5 percent for 2022. At the time, Chinese experts tended to share the premier’s view that the target was ambitious but not unattainable. Western research institutes and organizations, in particular, already considered the target to be too ambitious. The World Bank (January 2022) projected Chinese economic growth of 5.1 percent in 2022, while the forecasts of the International Monetary Fund (IMF, January) and the Kiel Institute (March) were even more pessimistic (both 4.8 percent).

After the official growth target was announced, both the domestic and global economic environments changed in ways that made it even harder to achieve. The unprecedentedly severe, large-scale and prolonged lockdowns in Shanghai and other cities in China severely curtailed normal business operations, exacerbated supply chain disruption and weighed on consumer spending. Global economic pressures also increased. Lastly, the war in Ukraine slowed the recovery of the global economy and fueled global inflation.

The official economic statistics for China published in April clearly reflected the further increasing downward pressure on the Chinese economy with a worse-than-expected trend. Industrial production in China fell by 2.9 percent year-on-year, mainly due to the decline in value-added in the automotive industry by over 31 percent. However, there are significant differences between individual provinces and regions. Regions with pandemic-related strict lockdowns suffered more than others. Industrial production in the Yangtze River Delta (where Shanghai is located) and the northeastern region (where Jilin is located) fell by 14.1 and 16.9 percent, respectively. This disadvantageous development was not limited to the industrial sector. The service sector (which contributed most of the three economic sectors to China’s GDP growth in 2021) also suffered significantly. Retail sales in China, for example, fell by 11.1 percent year-on-year in April.

The development of the Caixin China General Composite PMI, one of the leading indicators of macroeconomic trends, was also disappointing. It is based on surveys of private companies and covers various business aspects such as sales, new orders, employment and inventories. The index fell from 43.9 in March to just 37.2 in April, with the China Composite PMI reading below 50, indicating a general downward trend in business activity. The sharp decline in new orders, especially new foreign orders, also played a role in this decline.

Against this backdrop, the IMF lowered its forecast for Chinese economic growth this year to just 4.4 percent in April. The new forecast is further below China’s official growth target of 5.5 percent. And the IMF was not alone. The same month, several leading investment banks also corrected their China forecasts in the same direction. The forecasts of Goldman Sachs, Citi, Morgan Stanley and J.P. Morgan for China, for example, were between 4 and 4.3 percent, even lower than those of the IMF.

The Chinese government is aware of the challenges facing the Chinese economy. Some Chinese experts remain convinced that GDP growth of around 5.5 percent is still possible if China can succeed with its dynamic zero-Covid policy soon and takes effective countercyclical measures. The large-scale stimulus package announced in late May signals the Chinese government’s determination to revive the Chinese economy. It also aims to show that the Chinese government is willing to do whatever it takes. It includes six main aspects:

For example, the 33 planned measures include providing over ¥140 billion in additional VAT rebates to enterprises from an expanded number of sectors, assisting the aviation industry in its bond issuance of ¥200 billion, providing ¥150 billion in additional emergency loans to the civil aviation industry, assisting in the issuance of ¥300 billion in bonds for railroad construction, and easing restrictions on car purchases and partially and temporarily reducing taxes on the purchase of passenger vehicles.

However, given the inflationary pressures, the high level of uncertainty about the development of the COVID-19 pandemic in China and the already steadily rising public debt to GDP ratio, how much policy leeway does the Chinese government have to effectively stimulate the Chinese economy? Do Chinese experts and Western experts have different assessments of the Chinese government’s policy leeway in this regard? Are there different assessments of the strengths or weaknesses of the Chinese economy? Do Western and Chinese experts have different assessments of the critical economic challenges China faces and how these might affect economic growth? What role will international trade and foreign investment play in helping China meet (or not meet) its GDP growth target? Will the stimulus package have the desired impact? What more or else can China and the Chinese government do to support the country’s economic development?

These questions should be discussed in greater depth by experts from China and the West. For this reason, the upcoming Global China Conversation # 11, “Can China achieve its 2022 GDP growth target of 5.5%?” will bring Helge Berger (IMF) and Justin Yifu Lin (Peking University) together to discuss these and other related issues.

Dr Wan-Hsin Liu is a Senior Researcher in the Research Centers “International Trade and Investment” and “Innovation and International Competition” at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. Since 2016, she has also been Coordinator for the Kiel Center for Globalization.

Silas Dreier is the Coordinator of the Global China Conversations at the China Initiative of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. He is also a Master’s student in China Business and Economics at the University of Wuerzburg.

This article is part of the Global China Conversations event series of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). On Thursday, June 16, 2022 (2:00 PM, CEST), Helge Berger, Head of the IMF’s China Mission and Deputy Director in the IMF’s Asia and Pacific Department, and Justin Yifu Lin, Professor and Honorary Dean of the National School of Development at Peking University, will discuss the topic, “Can China Achieve its 2022 GDP Growth Target of 5.5 Percent.” China.Table is the media partner of this event series.

Saskia Wenz took over the position of Head of Supply Chain Planning China at Rena Technologies GmbH at the beginning of May. The mechanical engineering company from Gütenbach in Baden-Württemberg specializes in equipment for the semiconductor, medical, solar and glass industries. Wenz has been working for Rena Technologies since 2020. Her new place of work is Suzhou in Jiangsu province.

In May, Lennard Schlüter moved from the Bertrandt Group to Edag, a Swiss engineering service provider specializing in product solutions for the automotive industry. The development engineer will be responsible for project management in the China Infotainment division at Edag.

Winter wheat was harvested in Shandong province this week. Shandong is China’s second largest wheat growing region. Most recently, China’s agriculture minister warned of the consequences of climate change on harvests. China risks losing up to 20 percent of its harvests in the long term if countries around the world fail to reduce CO2 emissions. This is the result of a study by Tsinghua University in Beijing and the London-based think tank Chatham House (China.Table reported).

Despite the sanctions imposed on Russia following the attack on Ukraine, its most important export commodity is still flowing abroad unchecked. Europe also continues to purchase crude oil from Russia. However, while the EU wants to reduce its imports by 90 percent, China has now positioned itself as the most important buyer. In the spring, the country purchased around 1.6 million barrels of crude oil from Russia every day – and at hefty discounts, as Christiane Kuehl explains. With these imports, China primarily wants to replenish its strategic oil reserves. Once again, Beijing exploits global turmoil to its own advantage.

At the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles, US President Joe Biden actually wanted to show the unity between the United States and Latin America. Instead, the summit became proof of the US loss of power in the region – a loss that China in particular exploits and accelerates with targeted investments, as Frank Sieren writes. Not only is the People’s Republic the largest trading partner of Latin American countries, but it has also already incorporated many of them into Chinese-influenced institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Belt and Road Initiative. Common positions with the US, such as a joint condemnation of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, will thus be even more difficult, as the summit’s thin final paper proves.

Russia sells less oil to the EU and the USA. But the black gold is still flowing unchecked elsewhere. According to Russian statistics, the export volume, which initially collapsed as a result of the US embargo, has now returned to pre-war levels. President Vladimir Putin has Asia to thank for this: According to S&P Global, India imported around 20 times as much oil per day from Russia in April as the daily average for 2021 – at discount prices of up to $30 below global market prices (627,000 barrels per day). And China, too, after its initial reluctance, now seems to be negotiating more intensively with Russia about oil supplies – and at hefty discounts, too.

China buys Russian crude oil at a 35 percent discount from the current market price, Bloomberg recently reported, citing EU Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis. “What we are seeing, especially in this situation of Russia’s weakness, is that China is going to take good advantage of it,” Dombrovskis said. It would be less beneficial for Russia. Reuters reports about new oil contracts by various refiners, signed quietly behind the scenes.

China apparently does not want to make a big fuss about Moscow’s oil purchases, although there is currently no threat of secondary sanctions. The EU has also continued to buy Russian oil. It is possible that China is also trying out the balancing act between supporting Moscow and apparent neutrality in this field – in this case with a nice benefit for itself.

The EU wants to reduce its imports by 90 percent in response to Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia must therefore find other buyers. Since the global market price for crude oil has risen so sharply as a result of the embargos, Russia can afford to grant large discounts to friendly states. Russia still sells its oil at the equivalent of around $70 a barrel – more than before the war, but well below the current price for Brent crude oil of around $120 a barrel. Aside from China, India in particular, but also Turkey and some African states buy Russian oil at discount prices.

Russia will divert its oil to markets from which EU countries would buy it at a higher price, Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Nowak said at an event in May. Such announcements fuel the suspicion that China, for example, could become such a transshipment point for resold Russian oil – even if concrete indications of this are lacking so far.

China bought around 1.6 million barrels (bbl) of crude oil a day from Russia in the spring – making it the biggest buyer. Half of it – around 800,000 barrels per day – flowed to China through pipelines, government contracts or arrived by tanker. However, Reuters already expected an increase in Russian oil shipped to China by tankers to 1.1 million barrels a day in May

China’s imports, however, are led by Unipec, the trading arm of Sinopec, along with Zhenhua Oil, a unit of Chinese defense conglomerate Norinco, Reuters writes, citing traders, shipping data and a shipbroker’s report. According to the report, they are carrying more oil from Russia’s Baltic ports such as Ust-Luga as well as its Far East export hub Kozmino on the Pacific Ocean.

Unlike India’s state-owned oil refiners, which used public tenders to obtain Russia’s Urals crude oil, among others, China’s state-owned companies have been operating under the radar as much as possible, Bloomberg reported, citing traders. Chinese refiners have been constantly inquiring about possible shipments since March – including smaller independent refiners in Shandong. These were primarily interested in ESPO crude oil, named after the Russian Far East oil pipeline. The oil is then transferred to tankers in two Siberian ports and shipped to its destinations.

Technically, it is far easier to divert shipments by tanker than pipeline oil. But transportation is not the only problem here. Oil refineries are often designed to process certain types of crude and usually cannot turn over large volumes in a short time. Also, some commodity traders who have previously brokered Russian crude are dropping out. Two of the world’s largest commodity traders, Vitol and Trafigura, stopped buying from Rosneft, Russia’s largest oil producer, in mid-May. This hits India’s state-owned refiner Bharat Petroleum, for example. It recently bought two million barrels of Russian Urals oil from Trafigura, which were shipped in May. Glencore is also withdrawing from its Russian business. It is uncertain whether any alternative commodity markets will emerge so quickly in this environment.

Instead of letting Russian oil seep onto world markets, China is using it to build up onshore storage tanks for future emergencies, reports the Washington Post. China does not disclose the volume of its crude oil reserves, but there are estimates based on satellite imagery, for example. Bloomberg experts estimate China’s storage capacity for commercial and strategic oil reserves at over one billion barrels. There is still plenty of room to keep stockpiling, Bloomberg quoted Jane Xie, senior oil analyst at data and analytics firm Kpler, as saying. “It would be a good opportunity to do so if they can be procured on economically attractive terms.”

But that is merely only a momentary observation. The war will drag on. And of decisive importance for the global oil market will be whether Russia can win over ships and intermediaries as well as buyers. For now, China appears to be dealing directly with Russia, without intermediaries. For example, Shandong Port Group rented the tanker Kriti Future to transport oil from Kozmino to China in June, according to Bloomberg. The company has close ties to oil refineries in the Shandong province.

But for any resale, China might already need other players willing to touch Russian oil. Bloomberg, citing port agencies, lists several smaller companies that have stepped up since the war began. Litasco SA, a unit of Moscow-based producer Lukoil PJSC has become the largest handler of the Urals type, according to the report. Livna Shipping in Hong Kong is also new to the business. According to vessel-tracking data from Vortexa and Refinitiv, Livna has shipped more than seven million barrels of Russian crude to China since late April. Also emerging is a Geneva-based company with the curious name Bellatrix – an evil sorceress from the Harry Potter saga.

Like US President Joe Biden’s trip to Asia in May, last week’s 9th Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles was also marked by a loss of US political power in favor of China. The Washington Post calls the summit a “dud”.

Even before it started, things were not looking too bright for the summit: Biden had categorically ruled out the participation of authoritarian states such as Nicaragua, Cuba and Venezuela. In response, however, several democratically elected heads of government also canceled their participation, including Andrés Manuel López Obrador, President of Mexico, the US’s largest trading partner in Latin America. Xiomara Castro of Honduras, who was just recently elected, also declined to attend. The conservative President of Guatemala, Alejandro Giammattei, who was elected by a large majority in 2019, stayed away, as did Nayib Bukeles, the President of El Salvador. But government representatives of these countries were still present.

Brazilian right-wing nationalist President Jair Bolsonaro, a Donald Trump supporter, arrived after some hesitation, but beforehand publicly questioned whether Biden had actually won the US election. Argentina’s President Alberto Fernández, who leads a center-left electoral alliance, also attended the summit, but criticized that the United States hosting the Summit of the Americas “does not give the possibility to impose an admission right“.

Biden unsuccessfully tried to strike a different tone: They had come together to “demonstrate to our people the incredible power of democracies”. What was demonstrated, however, was above all the waning influence of the United States in the region. Among other things, Washington’s goal at the summit was to find a common USA and Latin American position on Russia and China. However, neither country is mentioned in the final declaration.

In his speech, Fernández made it clear that his position on Ukraine was more in line with Beijing’s than Washington’s: “It is urgent to build negotiation scenarios that will end the catastrophe that is war, without any humiliation or desire for domination,” Fernández said in a pointedly neutral manner. However, the Argentine President certainly had Argentine interests in mind: At the beginning of 2021, Argentina became part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As part of it, China wants to invest $24 billion in Argentina. This is good news for a country that only recently received a $44 billion bridging loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Similarly, many Latin American politicians are disgruntled that Biden gets a $40 billion aid package from Congress for the Ukraine war, but not $4 billion for the social crisis in Central America.

China’s investments are making it increasingly easy for Latin American countries to break away from the United States. China has long been South America’s largest trading partner. Ten years ago, trade with Latin America and the Caribbean was worth just $18 billion; today it is worth almost $450 billion. By 2035, it could be as much as $700 billion, experts estimate.

“When US authorities visit Latin America, they often talk about China and why Latin American countries should not deal with China,” says Jorge Heine, a Stanford-educated former Chilean minister with the left-liberal PPD. “When Chinese authorities visit, all the talk is about bridges and tunnels and highways and railways and trade.”

Not only does China lead by a wide margin when it comes to trade, but also in company investments and acquisitions. While the rest of the world invested a total of $44 billion in South America’s economy between 2017 and 2021, $328 billion came from China.

More than 70 percent of the investments go to the energy and electricity sector. The Chinese energy company State Grid supplies electricity to more than ten million people in Brazil alone. Chinese companies generate and distribute around twelve percent of the electricity in Brazil.

And Chinese investment is flowing into other sectors as well: The People’s Republic invested $73 billion in South America’s natural resources sector between 2000 and 2018. $4.5 billion flowed into lithium production in Mexico, Bolivia and Chile. A consortium led by Chinese companies is also building the subway in the Colombian capital Bogotá by 2028 and will operate it for 20 years. Institutionally, Beijing also has a lot to offer: Peru has been a member of the China-initiated Asian Development Bank (AIIB) since January. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador and Uruguay are already members. Founded in 2015, the global institution aims to finance infrastructure projects in the style of the World Bank – gladly including those that are part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). More than 20 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are already members of the BRI.

Last September, Daleep Singh, one of the U.S. Deputy National Security Advisors was on a promotional tour under the slogan “Build Back Better World” to offer socially responsible U.S. infrastructure financing as a counterweight to China: Transparent, sustainable and with proper labor standards. However, interest was low. At least the US has lent Ecuador $3.5 billion in the past year – under the condition that the country abandons certain Chinese technologies. Ecuador, however, is indebted to China to the tune of five billion. But that is just eleven percent of the country’s total foreign debt. The situation is more dramatic in Venezuela, which owes China $50 billion. Like Ecuador, it repays its debts with oil.

Economically, the US can no longer “match the deep pockets of Chinese investment bank,” fears Cynthia Arnson, Director of the Latin America Program at the Washington-based Wilson Center and a leading US South America specialist: “We have to come up with alternatives.”

Sinolytics is a European consulting and analysis company specializing in China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

A new study suggests that private creditors, not Chinese loans, dominate African debt. In their paper, Harry Verhoeven of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University and Nicolas Lippolis of the University of Oxford’s Department of Politics and International Relations object to the “debt trap diplomacy” narrative (China.Table reported). “What keeps African leaders awake at night is not Chinese debt traps. It is the whims of the bond market,” the report says. China is admittedly the continent’s largest bilateral creditor. But most of the debt is owed to private Western lenders, according to the researchers.

“[Chinese debt] is not the most rapidly growing segment of debt. Other credit lines have grown a lot more in recent years, especially those,” said Verhoeven, co-author of the report “Politics by Default: China and the Global Governance of African Debt”.

“These are bondholders, people from London, Frankfurt and New York who are buying African debt. That segment in the last couple of years has grown much faster than any liabilities that African states owe other creditors.”

The report cited internal estimates from international financial institutions. Sub-Saharan African sovereign debt owed to Chinese companies amounted to around $78 billion at the end of 2019. That represented about eight percent of the region’s total debt, which amounted to about $954 billion. Debt to China accounted for about 18 percent of African countries’ external debt, according to the study.

It is estimated that Beijing has lent about $150 billion to African countries since 2000, mainly through the China Exim Bank. “This is a substantial amount, but not large enough to have been the main driver of debt accumulation since 2004-05,” the study says. According to the paper’s data, the debt is concentrated in five countries: Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Zambia. “The idea that Chinese debt traps jeopardize the entire continent is hyperbolic,” the study says. ari

Taiwan’s chip industry has invested around 120 billion US dollars in the construction of new semiconductor factories. This is according to research by the Japanese newspaper Nikkei.Asia. 20 new factories are currently under construction or have recently been completed. These include three factories producing chips in the latest 3 nm process. These production facilities alone each cost over $10 billion.

Taiwan is the undisputed global market leader in the manufacturing of semiconductors. Taiwanese manufacturers hold a combined market share of over 90 percent for modern semiconductor components. The massive investments will enable Taiwan to further consolidate its market dominance. TSMC is also building two factories overseas, one in Arizona, USA and one in Kumamoto Prefecture in Japan, which will cost $12 billion and $8.6 billion respectively. nib

Semiconductor production in China is being disrupted as a result of the trucker strike in South Korea. According to Reuters, a South Korean company that produces isopropyl alcohol (IPA) on a large scale for cleaning semiconductor chips could not ship its product to China because of the blockade. According to Korea International Trade Association (Kita), the export of 90 tons of IPA, which is said to be equivalent to about a week’s supply, has been delayed.

“Followed by auto chip shortages and global shipping issues over the Russia-Ukraine war, the price of raw materials has already soared to the top level,” Yoon Kyung-sun of the Korea Automobile Manufacturers Association said at a press conference held jointly with Kita on Tuesday.

South Korea is a major supplier of semiconductors, smartphones, cars, batteries and electronic goods. Since June 7, 22,000 truck drivers have been protesting in South Korea due to a sharp rise in fuel prices. They demand higher wages and a minimum wage guarantee. Supply chains around the world, which have become fragile as a result of lockdowns and supply bottlenecks, are thus once again coming under pressure. niw/ rtr

The security pact signed between the Solomon Islands and China should be reviewed by the regional Pacific Islands Forum. This was demanded by the prime ministers of Samoa and New Zealand in a statement on Tuesday. The Pacific Island Countries Consultative Forum is scheduled to meet in Fiji in mid-July.

Beijing is trying to expand its influence in the region and most recently signed a security pact with the Solomon Islands, upsetting the US, Australia and New Zealand (China.Table reported). Speaking to China.Table, Malcolm Davis, an analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra, said that “China could extend its military presence far into the Southwest Pacific through diplomatic means, in a way that threatens Australia, New Zealand and the United States”.

Collin Beck, a top Solomon Islands diplomat who helped draft the pact, stressed in an interview with The Guardian that the Solomon Islands had no intention of allowing China to establish a permanent military presence in the country. “It has nothing to do with the establishment of a military base,” Beck said.

China also rejects criticism of the proposed pact. It says the agreement poses no military threat and that closer ties between China and the Solomon Islands would benefit everyone. Beijing is promoting a regional agreement with nearly a dozen Pacific countries that would consolidate cooperation in areas such as security and data communications. niw

At this year’s annual meeting of the National People’s Congress in early March, Premier Li Keqiang announced China’s GDP growth target of 5.5 percent for 2022. At the time, Chinese experts tended to share the premier’s view that the target was ambitious but not unattainable. Western research institutes and organizations, in particular, already considered the target to be too ambitious. The World Bank (January 2022) projected Chinese economic growth of 5.1 percent in 2022, while the forecasts of the International Monetary Fund (IMF, January) and the Kiel Institute (March) were even more pessimistic (both 4.8 percent).

After the official growth target was announced, both the domestic and global economic environments changed in ways that made it even harder to achieve. The unprecedentedly severe, large-scale and prolonged lockdowns in Shanghai and other cities in China severely curtailed normal business operations, exacerbated supply chain disruption and weighed on consumer spending. Global economic pressures also increased. Lastly, the war in Ukraine slowed the recovery of the global economy and fueled global inflation.

The official economic statistics for China published in April clearly reflected the further increasing downward pressure on the Chinese economy with a worse-than-expected trend. Industrial production in China fell by 2.9 percent year-on-year, mainly due to the decline in value-added in the automotive industry by over 31 percent. However, there are significant differences between individual provinces and regions. Regions with pandemic-related strict lockdowns suffered more than others. Industrial production in the Yangtze River Delta (where Shanghai is located) and the northeastern region (where Jilin is located) fell by 14.1 and 16.9 percent, respectively. This disadvantageous development was not limited to the industrial sector. The service sector (which contributed most of the three economic sectors to China’s GDP growth in 2021) also suffered significantly. Retail sales in China, for example, fell by 11.1 percent year-on-year in April.

The development of the Caixin China General Composite PMI, one of the leading indicators of macroeconomic trends, was also disappointing. It is based on surveys of private companies and covers various business aspects such as sales, new orders, employment and inventories. The index fell from 43.9 in March to just 37.2 in April, with the China Composite PMI reading below 50, indicating a general downward trend in business activity. The sharp decline in new orders, especially new foreign orders, also played a role in this decline.

Against this backdrop, the IMF lowered its forecast for Chinese economic growth this year to just 4.4 percent in April. The new forecast is further below China’s official growth target of 5.5 percent. And the IMF was not alone. The same month, several leading investment banks also corrected their China forecasts in the same direction. The forecasts of Goldman Sachs, Citi, Morgan Stanley and J.P. Morgan for China, for example, were between 4 and 4.3 percent, even lower than those of the IMF.

The Chinese government is aware of the challenges facing the Chinese economy. Some Chinese experts remain convinced that GDP growth of around 5.5 percent is still possible if China can succeed with its dynamic zero-Covid policy soon and takes effective countercyclical measures. The large-scale stimulus package announced in late May signals the Chinese government’s determination to revive the Chinese economy. It also aims to show that the Chinese government is willing to do whatever it takes. It includes six main aspects:

For example, the 33 planned measures include providing over ¥140 billion in additional VAT rebates to enterprises from an expanded number of sectors, assisting the aviation industry in its bond issuance of ¥200 billion, providing ¥150 billion in additional emergency loans to the civil aviation industry, assisting in the issuance of ¥300 billion in bonds for railroad construction, and easing restrictions on car purchases and partially and temporarily reducing taxes on the purchase of passenger vehicles.

However, given the inflationary pressures, the high level of uncertainty about the development of the COVID-19 pandemic in China and the already steadily rising public debt to GDP ratio, how much policy leeway does the Chinese government have to effectively stimulate the Chinese economy? Do Chinese experts and Western experts have different assessments of the Chinese government’s policy leeway in this regard? Are there different assessments of the strengths or weaknesses of the Chinese economy? Do Western and Chinese experts have different assessments of the critical economic challenges China faces and how these might affect economic growth? What role will international trade and foreign investment play in helping China meet (or not meet) its GDP growth target? Will the stimulus package have the desired impact? What more or else can China and the Chinese government do to support the country’s economic development?

These questions should be discussed in greater depth by experts from China and the West. For this reason, the upcoming Global China Conversation # 11, “Can China achieve its 2022 GDP growth target of 5.5%?” will bring Helge Berger (IMF) and Justin Yifu Lin (Peking University) together to discuss these and other related issues.

Dr Wan-Hsin Liu is a Senior Researcher in the Research Centers “International Trade and Investment” and “Innovation and International Competition” at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. Since 2016, she has also been Coordinator for the Kiel Center for Globalization.

Silas Dreier is the Coordinator of the Global China Conversations at the China Initiative of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. He is also a Master’s student in China Business and Economics at the University of Wuerzburg.

This article is part of the Global China Conversations event series of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). On Thursday, June 16, 2022 (2:00 PM, CEST), Helge Berger, Head of the IMF’s China Mission and Deputy Director in the IMF’s Asia and Pacific Department, and Justin Yifu Lin, Professor and Honorary Dean of the National School of Development at Peking University, will discuss the topic, “Can China Achieve its 2022 GDP Growth Target of 5.5 Percent.” China.Table is the media partner of this event series.

Saskia Wenz took over the position of Head of Supply Chain Planning China at Rena Technologies GmbH at the beginning of May. The mechanical engineering company from Gütenbach in Baden-Württemberg specializes in equipment for the semiconductor, medical, solar and glass industries. Wenz has been working for Rena Technologies since 2020. Her new place of work is Suzhou in Jiangsu province.

In May, Lennard Schlüter moved from the Bertrandt Group to Edag, a Swiss engineering service provider specializing in product solutions for the automotive industry. The development engineer will be responsible for project management in the China Infotainment division at Edag.

Winter wheat was harvested in Shandong province this week. Shandong is China’s second largest wheat growing region. Most recently, China’s agriculture minister warned of the consequences of climate change on harvests. China risks losing up to 20 percent of its harvests in the long term if countries around the world fail to reduce CO2 emissions. This is the result of a study by Tsinghua University in Beijing and the London-based think tank Chatham House (China.Table reported).