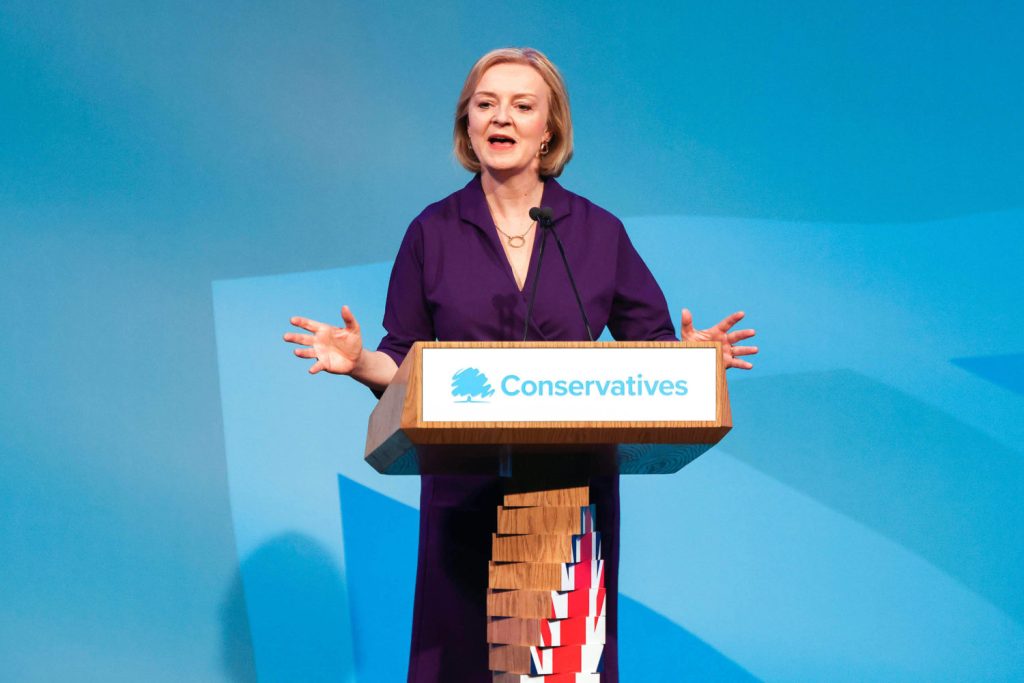

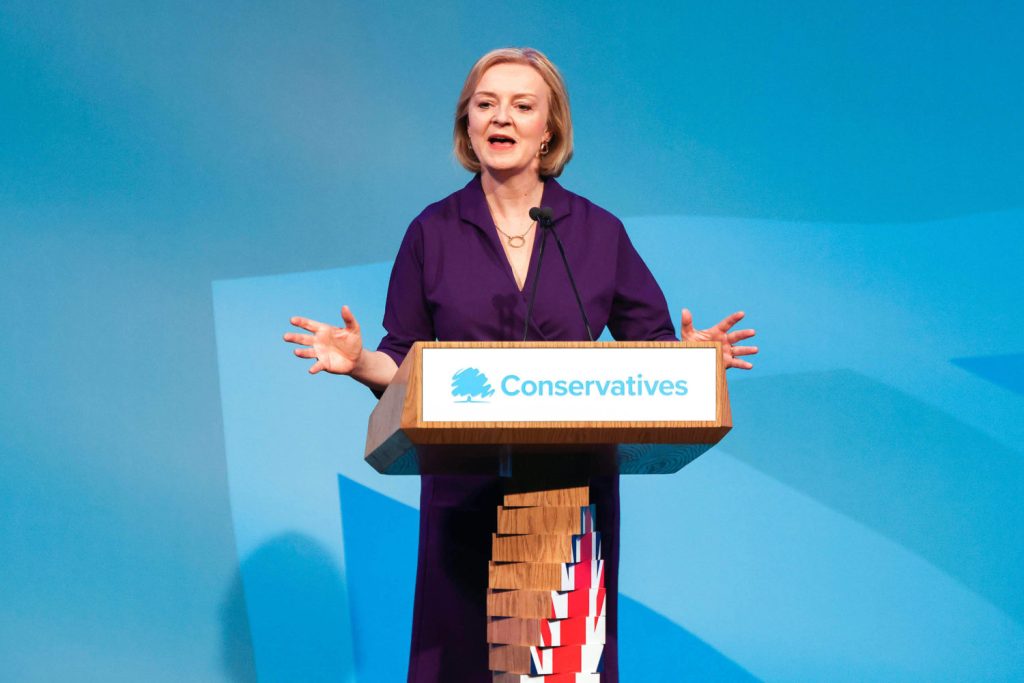

With her “cheese speech” in 2014, which went viral outside the UK this week, Britain’s new Prime Minister Elizabeth Truss has already made (Internet) history. At the time, “Liz” announced the return of domestically produced food at a Tory party conference. Very soon, the Conservative politician said at the time, British food exports will flood global markets: “And we are selling tea to China – Yorkshire tea!“

New in office, however, Truss no longer sees the People’s Republic primarily as a promising sales market for tea, but as a “threat to national security”. Under Truss, it is already clear that the United Kingdom is taking an even greater confrontational course against China. Her worldview is reminiscent of Ronald Reagan’s, who divided the world into liberal democracies and authoritarian dictatorships, writes Michael Radunski. In his analysis, he sheds light on the underlying reasons for her hard line against Beijing and the consequences this could have for the inflation-plagued island.

One consequence of the confrontation between China and the West in recent years has been the closure of many Confucius Institutes in the USA. The Chinese teaching and cultural institutions are accused of being too close to the government in Beijing. Trump in particular had it in for them during his term in office, which is why many of them had to close up shop in the USA. According to investigations by an NGO, however, they have now secretly returned to the United States. With a new name and a new coat of paint, they continue to try to exert influence on the American education system. Amelie Richter took a closer look at the report.

In October 2015, the patrons at the Plough, a pub in Cadsden, England, were quite surprised by the two well-dressed men at the bar. David Cameron and Xi Jinping each held a dark pint and casually discussed big politics. Appearances were not deceiving; the mood that evening was indeed as good as relations between the United Kingdom and China.

London had become a founding member of the Chinese-designed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – against the wishes of the United States. Moreover, as a member of the European Union, British diplomats strongly pushed for a formal EU trade and investment agreement with China. Cameron’s credo was: “The more we trade together, the more we have a stake in each other’s success, and the more we understand each other, the more that we can work together to confront the problems that face our world today.”

Elizabeth Truss, too, was part of the British government at the time. As Secretary of State for Education, she praised the opening of Confucius Institutes in the United Kingdom. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Cameron called China and Great Britain the “best partners in the West.” There was even talk of a “golden era“.

Some seven years later, Elizabeth “Liz” Truss is now British Prime Minister herself. On Tuesday, she was entrusted with the task of forming a new government by Queen Elizabeth II at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. And like David Cameron once, Truss wants to lead her country into a golden era. But China will no longer be her main partner. On the contrary.

In any case, the new leader of the Conservative Tory party leaves no doubt about her critical stance toward China: People close to the new head of government have indicated in recent days that Truss will order a comprehensive review of Britain’s security and defense strategy. In the process, she aims to classify China as a “threat to national security”.

The shift in wording would bring consequences. It would result in a further sharpening of China’s current designation as a “systemic challenge to our security, prosperity and values,” which London just made in March of last year.

If Truss were to no longer define China as a challenge but as a threat to the United Kingdom, the People’s Republic would henceforth be on the same level as Russia – a country that launched a war against Ukraine just a few months ago. It would be a severe step at the beginning of her term in office, but it would also have symbolic implications.

Truss’s plans to possibly label Chinese activities in Xinjiang as genocide are a different matter. According to reports, she has repeatedly chosen this term in confidential talks and announced such a step. It would be a harsher choice of words than those recently adopted by the United Nations.

The current report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang states that actions of the Chinese government in Xinjiang “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.” In this way, UN officials deliberately left open whether such crimes are actually being committed, even though the document speaks of “credible” allegations of torture (China.Table reported).

If the UK were to actually speak of genocide in Xinjiang, this would have far-reaching consequences: International obligations would take effect, under which active efforts would have to be made to stop genocide – for example, by imposing sanctions against the aggressor. Moreover, Truss would then be significantly limited in her options for action toward China. So it remains to be seen whether the new prime minister will begin her term with such a radical step.

However, it would be wrong to accuse Liz Truss of lightly ending the golden era between China and the UK with her pithy remarks. Rather, her stance shows how dramatically relations between the two countries have deteriorated in the time since Cameron and Xi had a merry drink together in 2015: It was the UK that became the first country in Europe to formally exclude Chinese telecommunications company Huawei from its 5G network. And after Beijing’s National Security Act in Hong Kong massively restricted freedom of expression and civil freedoms in the special administrative region, it was London that offered easier access to British citizenship for millions of Hong Kong’s citizens.

Last year, the two countries continued their confrontation course after London revoked the broadcast license of the English state broadcaster China Global Television Network (CGTN) in the UK. Only a few days later, the British BBC lost its license in China.

The reasons for the dramatic deterioration of relations are manifold. One particularly important reason is certainly Brexit. By leaving the EU, the UK severed its close ties with its biggest economic partner. As a consequence, the relationship with its closest security ally had to be reinforced: the United States. And the United States has been in open conflict with China at least since Donald Trump took office. When Trump imposed punitive tariffs against China, he urged the heads of government of other countries to side with the United States – and clearly against China.

Aside from politics, public opinion in the UK has also shifted dramatically. According to a recent poll by the think tank British Foreign Policy Group, the British public sees the rise of China as the third-biggest security threat after climate change and global terrorism.

While Britain’s future looked Chinese a few years ago in the Cadsden pub, it is now suddenly American through and through once more. Liz Truss is right in line with this: She is virtually looking for a fight with Europe and wants to immediately repeal the Northern Ireland Protocol from the Brexit treaty. And her view on global politics is very similar to that of Ronald Reagan, the former US president during the Cold War, when the world seemed to be divided into liberal democracies and authoritarian dictatorships.

But Liz Truss’ hard-headed way won’t succeed. Actions must follow pithy words – and these are also under certain constraints in London. The new prime minister is faced with several problems straight away: Prices are also rising rapidly on the island. In such a situation, it seems almost impossible to cut all ties with China.

If a product is not successful, re-branding sometimes helps. This is exactly what is happening in the United States with the controversial Confucius Institutes. Beijing-backed language and cultural centers are being renamed and simply reopened, a report by the conservative National Association of Scholars (NAS) non-governmental organization has revealed. Of the 118 Confucius Institutes that once existed in the United States, 104 had closed as of June of this year. Four more were undergoing closure.

But: Of all universities, “28 institutions have replaced their closed Confucius Institute with a similar program,” and “58 have maintained close relationships with their former CI partner.” US educational institutions have signed new agreements with Chinese sister universities and established centers closely modeled after the Confucius Institutes, the NAS reports. Universities continue to receive funding from the same Chinese government agencies that funded the Confucius Institutes. Staff and teaching materials have in many cases been passed on directly, the report continues.

The report cites several state universities and smaller colleges as examples. NAS uses a case study on Washington State University to show how the transition from Confucius Institute to new institution has taken place. The association has been monitoring developments in Confucius Institutes at US universities for some time. For its current investigation, a team collected several documents, including publicly available contracts and statements from university administrators, and conducted interviews, explains Ian Oxnevad, one of the report’s authors and a researcher at NAS. “All of our information was open-sourced, and documented,” Oxnevad tells China.Table. The report tracks the details of the closure – and, where relevant, the renaming and reopening – of 75 of the 104 Confucius Institutes closed in the United States.

During his term in office, US President Donald Trump had the Confucius Institutes investigated by several agencies, including the State Department and the FBI. In addition, in 2019, the US Senate called for more transparency on the centers or for them to be closed. In late 2020, the Trump administration filed a regulation to that effect with the Department of Homeland Security. It required US universities to disclose their affiliation with Confucius Institutes. Pressure from several sides resulted in Confucius Institutes officially closing their doors in recent years. Some US universities also had to return grant money, NAS notes.

According to the NAS report, a decision in the People’s Republic was also fundamental to the transformation of the Confucius Institutes in the United States: The governmental foreign policy cultural agency Hanban, which had once created the Confucius Institutes, renamed itself. In July 2020, the name was changed to the Center for Language Education and Cooperation (CLEC) and a separate organization was spun off, the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF).

The latter now finances and controls the Confucius Institutes, as NAS explains. The intention was to improve the image of the Confucius Institutes internationally. In reality, the line between the Chinese government and its offshoots is razor-thin: “CIEF is under the supervision of the Chinese Ministry of Education and is funded by the Chinese government,” the report says.

NAS researcher Rachelle Peterson, who was also involved in the report, emphasizes that the closure of the Confucius Institutes was “a story of success because the United States recognized the threat posed by Confucius Institutes and it addressed that threat.” But what is currently happening is also a warning. Because the Chinese government is attempting to circumvent political regulations. “In military terms, this would be called an outflanking maneuver,” Peterson said at a Heritage Foundation Thanksgiving event. The Chinese government, she said, is betting that no one will notice the Chinese government’s continued influence on higher education “if it takes away the name, Confucius Institute, and tweaks the structure of a program.”

So has the academic world in the USA now perked up all its ears? Probably not. “Our report and findings on universities was mostly met with silence and some vocal denial from several universities that asserted that their Confucius Institutes (CIs) had closed, despite evidence indicating otherwise,” Oxnevad tells China.Table. However, there is interest within the US government to also develop new policies to limit Beijing’s influence on the US university system, he said. “I would expect interest in curtailing China within academia to continue to grow, as it remains an area of bipartisan interest and connected to a pressing foreign policy issue.”

The growing tensions between the United States and China after Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan could now also lead to a renewed spotlight on academic cooperation with language and cultural centers from the government side. Most recently, however, the development went in a different direction: In 2021, the government under Joe Biden rescinded a rule according to which colleges participating in the official US student exchange program had to disclose information on potential financial ties to Confucius Institutes.

When it comes to providing Mandarin training in US schools, colleges, and universities, NAS researcher Oxnevad believes there are other ways than cooperating with Beijing. For example, native teachers: “The US is a diverse republic with American citizens who are native Mandarin speakers.” The US government has also been heavily investing in developing its own programs to improve foreign language skills in higher education, he adds. “With Chinese being one of the more sought after languages in which to invest.”

Offers from Taiwan to replace the Confucius Institutes are also an option. “Simply put, multiple options are available to offer Mandarin without Beijing’s input or influence,” Oxnevad said.

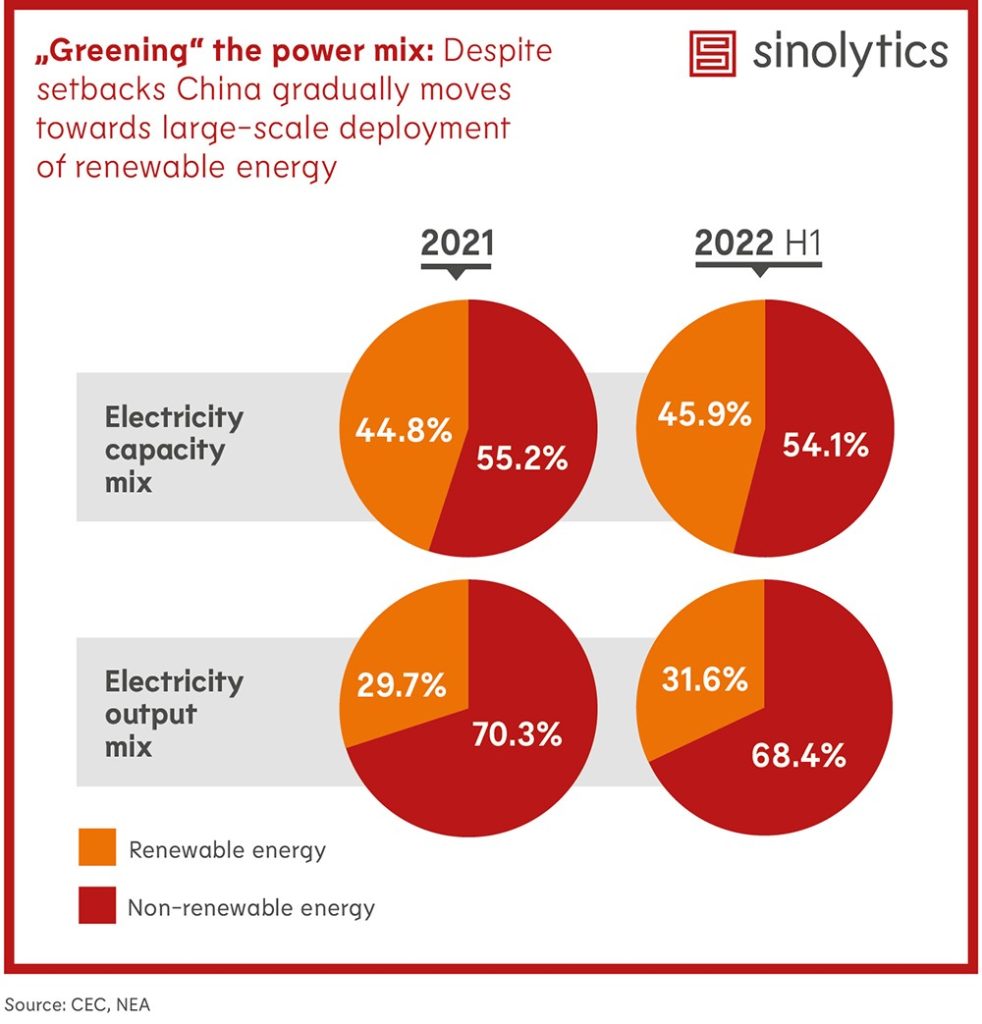

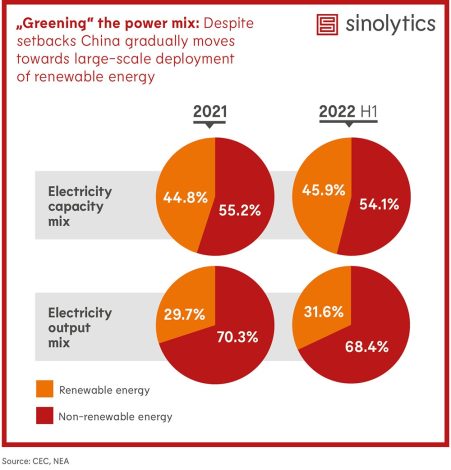

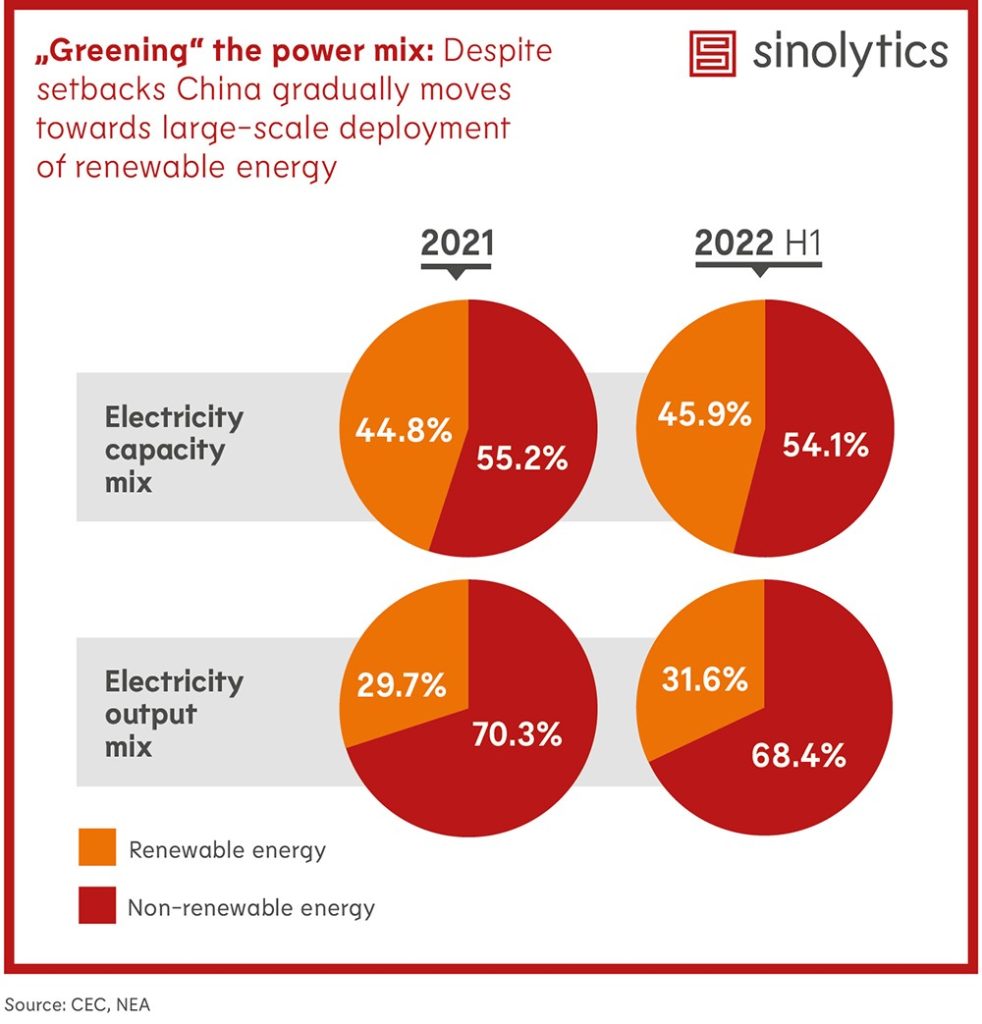

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock wants to stop Germany’s years-long policy of “change through trade,” which she said has failed spectacularly in Russia and China. “Trade is not automatically followed by democratic change,” Baerbock said at the Economics Day of the 20th Conference of Heads of German Missions Abroad on Tuesday at the Federal Foreign Office in Berlin. The mistakes made in dealing with Russia must now be taken into account by the German government when drafting a German China strategy, she said.

For too long, the focus has been on interdependence, Baerbock continued. “We cannot afford to rely on autocratic countries.” China still bars imports from Australia for “political reasons,” she said. Against Lithuania, Beijing had imposed a trade embargo, “we shouldn’t just brush that aside“. Germany would have to diversify further to minimize the impact of such sanctions, she said. There were many countries in the Indo-Pacific region with which cooperation was worthwhile, Baerbock explained. “It’s not without reason that Apple is moving part of its production to Vietnam right now.”

The German Foreign Minister also indirectly addressed the human rights situation in China. She said that one could no longer afford to shape the economy solely according to a “business-first credo”. Products made from forced labor should no longer be allowed to be offered in Europe. “Values and interests are not opposites, but two sides of the same coin.” fpe

China’s chief climate envoy, Xie Zhenhua, has promoted the opportunities of transforming China’s economy to meet climate goals at a conference. Xie projects that spending of ¥130 trillion ($19 trillion) will be needed to meet the country’s climate goals. “It is not easy to reach peak carbon emission within seven years and … 30 years after that while ensuring economic safety,” Xie said, according to National Business Daily.

President Xi Jinping announced at a UN General Assembly two years ago that the People’s Republic would achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. “China will strive to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060,” Xi said.

Sebastian Eckhardt, economist at the World Bank, demonstrated at the IfW event “Green Growth: What can we Expect from China?” that China needs to invest $13.8 trillion to become carbon-neutral by 2060 (China.Table reported and is media partner of the event series). The People’s Republic is responsible for about 30 percent of annual global carbon emissions. Per capita emissions are at a similar level to those in Germany. niw

Instead of settling its payments to the Russian gas company Gazprom in US dollars, China plans to use the Chinese yuan and ruble in the future. Gazprom made the announcement on Tuesday after signing an agreement to that effect. Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller said, according to Reuters, that allowing payments in Russian rubles and Chinese yuan would be “mutually beneficial” for both Gazprom and Beijing’s state-run China National Petroleum Corporation. Gazprom did not comment on the details, for instance when the currencies would be switched.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin had decreed in March, in response to Western sanctions imposed on Russia, that “unfriendly states” could only pay for their gas in rubles in the future. China continues to maintain close relations with Russia. Even shortly before the invasion of Ukraine, Xi and Putin had signed an extension of gas supplies from Russia (China.Table reported). niw

John Kerry, the top climate envoy for US President Joe Biden’s administration, expresses hope that climate talks with China can resume soon. “My hope is that President Xi will recognize the benefit of getting both of us moving in the same direction,” he said. “The world needs to see these two powerful countries actually working together,” Kerry said, according to Bloomberg.

China suspended climate talks with the US on August 5 as part of a series of “countermeasures” after US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan. China’s ambassador to the US, Qin Gang, then said Washington must change its behavior toward Taiwan and prevent further escalation in the region. Only then could the talks be resumed.

Kerry is currently in Southeast Asia to discuss coal phase-out options with countries including Japan, India and South Korea ahead of the G-20 summit. Last week, the United States and Indonesia already agreed on a financial and organizational framework to accelerate the transition to renewable energy. fpe

When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, discussions began almost concurrently in the media. Which side is China on? What role should it play in the conflict, according to journalists? Is an invasion of Taiwan, long thought unlikely, just as imminent? Six months later, it is clear that the invasion is not in China’s interest, nor will it inspire China to invade Taiwan. Why not? Two central arguments are always raised in discussions about an invasion: semiconductors and political motives.

The US sanctions against China in the high-tech sector are hindering China’s access to high-end semiconductors. Although this has spurred massive new investment in China’s chip sector, it will probably take at least another ten years before the country is truly at the forefront and able to substitute the imports necessary for production, analysts believe. Taiwan, to which the People’s Republic has laid claim since its founding, holds a global market share of 55 percent with TSMC (compared to China’s 8 percent) and is thus an integral part of global semiconductor production. So the idea is obvious: With an invasion, access to necessary cutting-edge technologies could be secured and, at the same time, the largest competitor and its know-how could be integrated into the country’s own semiconductor production.

But it is not as simple as it sounds. Taiwan’s chip production is rooted in regional value chains. Key components are shipped from Japan and South Korea. Even if China were able to procure them, how would the newly conquered Taiwanese top engineers be persuaded to work for the People’s Republic? They are more likely to emigrate to the West, along with their knowledge. An invasion for semiconductors would therefore hardly be a gain for China. But what about political motives?

International media repeatedly speculate that Xi Jinping secured his third term in office with the promise to “finally return Taiwan to the motherland”. It is therefore logical that the Russian breach of international law opens the window for China to do the same to Taiwan. What is overlooked: China does not need Russia to invade Taiwan. The 2005 anti-secession law already declares that the People’s Republic will resort to military action should Taiwan take any steps toward independence. What is also often forgotten, given the ubiquitous wolf-warrior rhetoric emanating from the Chinese Foreign Ministry and the state-run Global Times newspaper: Economic growth and prosperity are the central pillar of the party-state’s legitimacy. “You’ll get rich and stay out of politics in return” – with this contract, the CP has ruled through since Deng Xiaoping.

The massive resistance of the people of Ukraine against the Russian invaders has shown that all the theories of a swift conquest were an illusion. Taiwan, as should be clear by now, would fight back no less determined. Meanwhile, China is already fighting against time with its zero-Covid policy. There are massive protests nationwide, of which only a fraction make it into the Western media. The real estate crisis has also reached a new high. Meanwhile, apartment owners in over 100 cities are refusing to pay their loan installments. Southwest China is experiencing the longest heat wave ever, with massive drought, water shortages and power outages. In traditional China, economic crises, protests and weather disasters were a sign that the dynasty had lost the heavenly mandate. A Taiwanese incursion, should it turn into a lengthy and costly conflict, would not only pose a long-term threat to the legitimacy of the political leadership in Beijing. It could mean the end of party rule. In conclusion: An invasion would not be a gain for China, both economically and politically.

By the same token, the invasion of Ukraine was not a win-win for China, as its military, geopolitical, and economic consequences are also felt in Zhongnanhai. The burning of Russian troops on the Black Sea indeed reduces potential military threats from the regions above the Amur. But people certainly feel more threatened than before the invasion. There is NATO’s northern enlargement on the one hand, but also the allies’ new claim to focus more on China as a threat. Even the idea that Russia might be successful in Ukraine is likely to cause Beijing headaches. After all, should Russia win in Ukraine against all odds, Central Asia could be the next target of Putin’s revisionism. China has been massively investing in the oil and gas resources of the region that borders its west. Not only would these interests be put at risk, but resistance fighting and other instabilities could easily spill over the borders into Xinjiang and jeopardize what the Communist Party sees as a currently stable situation in the autonomous region.

And China has also underestimated the economic reactions from Ukraine and the EU. Rising energy prices and the impact of sanctions are putting pressure on the global economy. Combined with China’s real estate and banking crisis, as well as the extreme weather of recent months, this further exacerbates the political situation for the leadership.

So, just before the 20th CP Congress on October 16, Beijing is under more pressure than it has been in a long time. Not only has a military invasion of Taiwan been complicated. The economic integration of Taiwan, which was the preferred objective, has also become more distant due to the rapid deterioration of relations with Taiwan and the United States. The renewed rallying of the allies complicates China’s geopolitical ambitions, and Russia’s unpredictability threatens the stability of the western regions. Last but not least, economic difficulties and the failure of the zero-Covid policy are threatening Xi Jinping’s position within the Party. At the Party Congress, he is expected to be re-elected to his third term as Party Chairman. For him, however, the war in Ukraine has brought one thing above all: uncertainty.

This article is part of the “Global China Conversations” series of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). On Thursday, September 8, 2022 (11:00 AM CEST), Julian Hinz, trade and sanctions expert at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy and junior professor of International Economics at Bielefeld University, and Marina Rudyak will discuss the topic, “Can China Achieve its 2022 GDP Growth Target of 5.5 Percent.” China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

Marina Rudyak is an interim professor of Chinese politics at Goethe University Frankfurt and an academic assistant for sinology at Heidelberg University. Her research focuses on Chinese development policy, Global China and party discourses of the Chinese Communist Party.

Silas Dreier is coordinator of the Global China Conversations at the China Initiative of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. He is also working on his Master’s degree in China Business and Economics at the University of Wuerzburg.

Elaine Pearson is the new Executive Director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division. Based in Sydney, she will oversee the department’s work in more than 20 countries. Pearson joined Human Rights Watch (HWR) in 2007 and previously served as Deputy Director of the Asia division and then built Human Rights Watch’s Australia office, where she most recently served as the organization’s first Australia director from 2013 to 2022. Pearson has led numerous human rights investigations in the Asia-Pacific region. Prior to HWR, she worked at the UN and numerous NGOs, including in Bangkok, Hong Kong, and Kathmandu.

Richard Tibbels is the new Special Representative for the Indo-Pacific at the European External Action Service (EEAS). Tibbels previously spent four years as Head of the Eastern Partnership, Regional Cooperation (Arctic, Barents, Baltic and Black Seas) and OSCE Division in the EEAS. Prior to that, he held numerous positions in the EEAS and in the European Commission’s Directorate-General, where he managed relations with the EU’s Eastern and Southern Neighborhood. He succeeds Gabriele Visentin, who becomes the designated EU Ambassador to Australia.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

In China, the Yangtze River basin has been affected by drought. Water levels have dropped to their lowest since record-keeping began in 1865 (China.Table reported). In Wuhan, citizens can now even take photos of the exposed pier of the Wuhan-Yangtze Bridge. Due to the persistent heat, the water level dropped up to 18 meters.

With her “cheese speech” in 2014, which went viral outside the UK this week, Britain’s new Prime Minister Elizabeth Truss has already made (Internet) history. At the time, “Liz” announced the return of domestically produced food at a Tory party conference. Very soon, the Conservative politician said at the time, British food exports will flood global markets: “And we are selling tea to China – Yorkshire tea!“

New in office, however, Truss no longer sees the People’s Republic primarily as a promising sales market for tea, but as a “threat to national security”. Under Truss, it is already clear that the United Kingdom is taking an even greater confrontational course against China. Her worldview is reminiscent of Ronald Reagan’s, who divided the world into liberal democracies and authoritarian dictatorships, writes Michael Radunski. In his analysis, he sheds light on the underlying reasons for her hard line against Beijing and the consequences this could have for the inflation-plagued island.

One consequence of the confrontation between China and the West in recent years has been the closure of many Confucius Institutes in the USA. The Chinese teaching and cultural institutions are accused of being too close to the government in Beijing. Trump in particular had it in for them during his term in office, which is why many of them had to close up shop in the USA. According to investigations by an NGO, however, they have now secretly returned to the United States. With a new name and a new coat of paint, they continue to try to exert influence on the American education system. Amelie Richter took a closer look at the report.

In October 2015, the patrons at the Plough, a pub in Cadsden, England, were quite surprised by the two well-dressed men at the bar. David Cameron and Xi Jinping each held a dark pint and casually discussed big politics. Appearances were not deceiving; the mood that evening was indeed as good as relations between the United Kingdom and China.

London had become a founding member of the Chinese-designed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – against the wishes of the United States. Moreover, as a member of the European Union, British diplomats strongly pushed for a formal EU trade and investment agreement with China. Cameron’s credo was: “The more we trade together, the more we have a stake in each other’s success, and the more we understand each other, the more that we can work together to confront the problems that face our world today.”

Elizabeth Truss, too, was part of the British government at the time. As Secretary of State for Education, she praised the opening of Confucius Institutes in the United Kingdom. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Cameron called China and Great Britain the “best partners in the West.” There was even talk of a “golden era“.

Some seven years later, Elizabeth “Liz” Truss is now British Prime Minister herself. On Tuesday, she was entrusted with the task of forming a new government by Queen Elizabeth II at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. And like David Cameron once, Truss wants to lead her country into a golden era. But China will no longer be her main partner. On the contrary.

In any case, the new leader of the Conservative Tory party leaves no doubt about her critical stance toward China: People close to the new head of government have indicated in recent days that Truss will order a comprehensive review of Britain’s security and defense strategy. In the process, she aims to classify China as a “threat to national security”.

The shift in wording would bring consequences. It would result in a further sharpening of China’s current designation as a “systemic challenge to our security, prosperity and values,” which London just made in March of last year.

If Truss were to no longer define China as a challenge but as a threat to the United Kingdom, the People’s Republic would henceforth be on the same level as Russia – a country that launched a war against Ukraine just a few months ago. It would be a severe step at the beginning of her term in office, but it would also have symbolic implications.

Truss’s plans to possibly label Chinese activities in Xinjiang as genocide are a different matter. According to reports, she has repeatedly chosen this term in confidential talks and announced such a step. It would be a harsher choice of words than those recently adopted by the United Nations.

The current report on the human rights situation in Xinjiang states that actions of the Chinese government in Xinjiang “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.” In this way, UN officials deliberately left open whether such crimes are actually being committed, even though the document speaks of “credible” allegations of torture (China.Table reported).

If the UK were to actually speak of genocide in Xinjiang, this would have far-reaching consequences: International obligations would take effect, under which active efforts would have to be made to stop genocide – for example, by imposing sanctions against the aggressor. Moreover, Truss would then be significantly limited in her options for action toward China. So it remains to be seen whether the new prime minister will begin her term with such a radical step.

However, it would be wrong to accuse Liz Truss of lightly ending the golden era between China and the UK with her pithy remarks. Rather, her stance shows how dramatically relations between the two countries have deteriorated in the time since Cameron and Xi had a merry drink together in 2015: It was the UK that became the first country in Europe to formally exclude Chinese telecommunications company Huawei from its 5G network. And after Beijing’s National Security Act in Hong Kong massively restricted freedom of expression and civil freedoms in the special administrative region, it was London that offered easier access to British citizenship for millions of Hong Kong’s citizens.

Last year, the two countries continued their confrontation course after London revoked the broadcast license of the English state broadcaster China Global Television Network (CGTN) in the UK. Only a few days later, the British BBC lost its license in China.

The reasons for the dramatic deterioration of relations are manifold. One particularly important reason is certainly Brexit. By leaving the EU, the UK severed its close ties with its biggest economic partner. As a consequence, the relationship with its closest security ally had to be reinforced: the United States. And the United States has been in open conflict with China at least since Donald Trump took office. When Trump imposed punitive tariffs against China, he urged the heads of government of other countries to side with the United States – and clearly against China.

Aside from politics, public opinion in the UK has also shifted dramatically. According to a recent poll by the think tank British Foreign Policy Group, the British public sees the rise of China as the third-biggest security threat after climate change and global terrorism.

While Britain’s future looked Chinese a few years ago in the Cadsden pub, it is now suddenly American through and through once more. Liz Truss is right in line with this: She is virtually looking for a fight with Europe and wants to immediately repeal the Northern Ireland Protocol from the Brexit treaty. And her view on global politics is very similar to that of Ronald Reagan, the former US president during the Cold War, when the world seemed to be divided into liberal democracies and authoritarian dictatorships.

But Liz Truss’ hard-headed way won’t succeed. Actions must follow pithy words – and these are also under certain constraints in London. The new prime minister is faced with several problems straight away: Prices are also rising rapidly on the island. In such a situation, it seems almost impossible to cut all ties with China.

If a product is not successful, re-branding sometimes helps. This is exactly what is happening in the United States with the controversial Confucius Institutes. Beijing-backed language and cultural centers are being renamed and simply reopened, a report by the conservative National Association of Scholars (NAS) non-governmental organization has revealed. Of the 118 Confucius Institutes that once existed in the United States, 104 had closed as of June of this year. Four more were undergoing closure.

But: Of all universities, “28 institutions have replaced their closed Confucius Institute with a similar program,” and “58 have maintained close relationships with their former CI partner.” US educational institutions have signed new agreements with Chinese sister universities and established centers closely modeled after the Confucius Institutes, the NAS reports. Universities continue to receive funding from the same Chinese government agencies that funded the Confucius Institutes. Staff and teaching materials have in many cases been passed on directly, the report continues.

The report cites several state universities and smaller colleges as examples. NAS uses a case study on Washington State University to show how the transition from Confucius Institute to new institution has taken place. The association has been monitoring developments in Confucius Institutes at US universities for some time. For its current investigation, a team collected several documents, including publicly available contracts and statements from university administrators, and conducted interviews, explains Ian Oxnevad, one of the report’s authors and a researcher at NAS. “All of our information was open-sourced, and documented,” Oxnevad tells China.Table. The report tracks the details of the closure – and, where relevant, the renaming and reopening – of 75 of the 104 Confucius Institutes closed in the United States.

During his term in office, US President Donald Trump had the Confucius Institutes investigated by several agencies, including the State Department and the FBI. In addition, in 2019, the US Senate called for more transparency on the centers or for them to be closed. In late 2020, the Trump administration filed a regulation to that effect with the Department of Homeland Security. It required US universities to disclose their affiliation with Confucius Institutes. Pressure from several sides resulted in Confucius Institutes officially closing their doors in recent years. Some US universities also had to return grant money, NAS notes.

According to the NAS report, a decision in the People’s Republic was also fundamental to the transformation of the Confucius Institutes in the United States: The governmental foreign policy cultural agency Hanban, which had once created the Confucius Institutes, renamed itself. In July 2020, the name was changed to the Center for Language Education and Cooperation (CLEC) and a separate organization was spun off, the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF).

The latter now finances and controls the Confucius Institutes, as NAS explains. The intention was to improve the image of the Confucius Institutes internationally. In reality, the line between the Chinese government and its offshoots is razor-thin: “CIEF is under the supervision of the Chinese Ministry of Education and is funded by the Chinese government,” the report says.

NAS researcher Rachelle Peterson, who was also involved in the report, emphasizes that the closure of the Confucius Institutes was “a story of success because the United States recognized the threat posed by Confucius Institutes and it addressed that threat.” But what is currently happening is also a warning. Because the Chinese government is attempting to circumvent political regulations. “In military terms, this would be called an outflanking maneuver,” Peterson said at a Heritage Foundation Thanksgiving event. The Chinese government, she said, is betting that no one will notice the Chinese government’s continued influence on higher education “if it takes away the name, Confucius Institute, and tweaks the structure of a program.”

So has the academic world in the USA now perked up all its ears? Probably not. “Our report and findings on universities was mostly met with silence and some vocal denial from several universities that asserted that their Confucius Institutes (CIs) had closed, despite evidence indicating otherwise,” Oxnevad tells China.Table. However, there is interest within the US government to also develop new policies to limit Beijing’s influence on the US university system, he said. “I would expect interest in curtailing China within academia to continue to grow, as it remains an area of bipartisan interest and connected to a pressing foreign policy issue.”

The growing tensions between the United States and China after Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan could now also lead to a renewed spotlight on academic cooperation with language and cultural centers from the government side. Most recently, however, the development went in a different direction: In 2021, the government under Joe Biden rescinded a rule according to which colleges participating in the official US student exchange program had to disclose information on potential financial ties to Confucius Institutes.

When it comes to providing Mandarin training in US schools, colleges, and universities, NAS researcher Oxnevad believes there are other ways than cooperating with Beijing. For example, native teachers: “The US is a diverse republic with American citizens who are native Mandarin speakers.” The US government has also been heavily investing in developing its own programs to improve foreign language skills in higher education, he adds. “With Chinese being one of the more sought after languages in which to invest.”

Offers from Taiwan to replace the Confucius Institutes are also an option. “Simply put, multiple options are available to offer Mandarin without Beijing’s input or influence,” Oxnevad said.

Sinolytics is a European research-based consultancy entirely focused on China. It advises European companies on their strategic orientation and concrete business activities in the People’s Republic.

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock wants to stop Germany’s years-long policy of “change through trade,” which she said has failed spectacularly in Russia and China. “Trade is not automatically followed by democratic change,” Baerbock said at the Economics Day of the 20th Conference of Heads of German Missions Abroad on Tuesday at the Federal Foreign Office in Berlin. The mistakes made in dealing with Russia must now be taken into account by the German government when drafting a German China strategy, she said.

For too long, the focus has been on interdependence, Baerbock continued. “We cannot afford to rely on autocratic countries.” China still bars imports from Australia for “political reasons,” she said. Against Lithuania, Beijing had imposed a trade embargo, “we shouldn’t just brush that aside“. Germany would have to diversify further to minimize the impact of such sanctions, she said. There were many countries in the Indo-Pacific region with which cooperation was worthwhile, Baerbock explained. “It’s not without reason that Apple is moving part of its production to Vietnam right now.”

The German Foreign Minister also indirectly addressed the human rights situation in China. She said that one could no longer afford to shape the economy solely according to a “business-first credo”. Products made from forced labor should no longer be allowed to be offered in Europe. “Values and interests are not opposites, but two sides of the same coin.” fpe

China’s chief climate envoy, Xie Zhenhua, has promoted the opportunities of transforming China’s economy to meet climate goals at a conference. Xie projects that spending of ¥130 trillion ($19 trillion) will be needed to meet the country’s climate goals. “It is not easy to reach peak carbon emission within seven years and … 30 years after that while ensuring economic safety,” Xie said, according to National Business Daily.

President Xi Jinping announced at a UN General Assembly two years ago that the People’s Republic would achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. “China will strive to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060,” Xi said.

Sebastian Eckhardt, economist at the World Bank, demonstrated at the IfW event “Green Growth: What can we Expect from China?” that China needs to invest $13.8 trillion to become carbon-neutral by 2060 (China.Table reported and is media partner of the event series). The People’s Republic is responsible for about 30 percent of annual global carbon emissions. Per capita emissions are at a similar level to those in Germany. niw

Instead of settling its payments to the Russian gas company Gazprom in US dollars, China plans to use the Chinese yuan and ruble in the future. Gazprom made the announcement on Tuesday after signing an agreement to that effect. Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller said, according to Reuters, that allowing payments in Russian rubles and Chinese yuan would be “mutually beneficial” for both Gazprom and Beijing’s state-run China National Petroleum Corporation. Gazprom did not comment on the details, for instance when the currencies would be switched.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin had decreed in March, in response to Western sanctions imposed on Russia, that “unfriendly states” could only pay for their gas in rubles in the future. China continues to maintain close relations with Russia. Even shortly before the invasion of Ukraine, Xi and Putin had signed an extension of gas supplies from Russia (China.Table reported). niw

John Kerry, the top climate envoy for US President Joe Biden’s administration, expresses hope that climate talks with China can resume soon. “My hope is that President Xi will recognize the benefit of getting both of us moving in the same direction,” he said. “The world needs to see these two powerful countries actually working together,” Kerry said, according to Bloomberg.

China suspended climate talks with the US on August 5 as part of a series of “countermeasures” after US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan. China’s ambassador to the US, Qin Gang, then said Washington must change its behavior toward Taiwan and prevent further escalation in the region. Only then could the talks be resumed.

Kerry is currently in Southeast Asia to discuss coal phase-out options with countries including Japan, India and South Korea ahead of the G-20 summit. Last week, the United States and Indonesia already agreed on a financial and organizational framework to accelerate the transition to renewable energy. fpe

When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, discussions began almost concurrently in the media. Which side is China on? What role should it play in the conflict, according to journalists? Is an invasion of Taiwan, long thought unlikely, just as imminent? Six months later, it is clear that the invasion is not in China’s interest, nor will it inspire China to invade Taiwan. Why not? Two central arguments are always raised in discussions about an invasion: semiconductors and political motives.

The US sanctions against China in the high-tech sector are hindering China’s access to high-end semiconductors. Although this has spurred massive new investment in China’s chip sector, it will probably take at least another ten years before the country is truly at the forefront and able to substitute the imports necessary for production, analysts believe. Taiwan, to which the People’s Republic has laid claim since its founding, holds a global market share of 55 percent with TSMC (compared to China’s 8 percent) and is thus an integral part of global semiconductor production. So the idea is obvious: With an invasion, access to necessary cutting-edge technologies could be secured and, at the same time, the largest competitor and its know-how could be integrated into the country’s own semiconductor production.

But it is not as simple as it sounds. Taiwan’s chip production is rooted in regional value chains. Key components are shipped from Japan and South Korea. Even if China were able to procure them, how would the newly conquered Taiwanese top engineers be persuaded to work for the People’s Republic? They are more likely to emigrate to the West, along with their knowledge. An invasion for semiconductors would therefore hardly be a gain for China. But what about political motives?

International media repeatedly speculate that Xi Jinping secured his third term in office with the promise to “finally return Taiwan to the motherland”. It is therefore logical that the Russian breach of international law opens the window for China to do the same to Taiwan. What is overlooked: China does not need Russia to invade Taiwan. The 2005 anti-secession law already declares that the People’s Republic will resort to military action should Taiwan take any steps toward independence. What is also often forgotten, given the ubiquitous wolf-warrior rhetoric emanating from the Chinese Foreign Ministry and the state-run Global Times newspaper: Economic growth and prosperity are the central pillar of the party-state’s legitimacy. “You’ll get rich and stay out of politics in return” – with this contract, the CP has ruled through since Deng Xiaoping.

The massive resistance of the people of Ukraine against the Russian invaders has shown that all the theories of a swift conquest were an illusion. Taiwan, as should be clear by now, would fight back no less determined. Meanwhile, China is already fighting against time with its zero-Covid policy. There are massive protests nationwide, of which only a fraction make it into the Western media. The real estate crisis has also reached a new high. Meanwhile, apartment owners in over 100 cities are refusing to pay their loan installments. Southwest China is experiencing the longest heat wave ever, with massive drought, water shortages and power outages. In traditional China, economic crises, protests and weather disasters were a sign that the dynasty had lost the heavenly mandate. A Taiwanese incursion, should it turn into a lengthy and costly conflict, would not only pose a long-term threat to the legitimacy of the political leadership in Beijing. It could mean the end of party rule. In conclusion: An invasion would not be a gain for China, both economically and politically.

By the same token, the invasion of Ukraine was not a win-win for China, as its military, geopolitical, and economic consequences are also felt in Zhongnanhai. The burning of Russian troops on the Black Sea indeed reduces potential military threats from the regions above the Amur. But people certainly feel more threatened than before the invasion. There is NATO’s northern enlargement on the one hand, but also the allies’ new claim to focus more on China as a threat. Even the idea that Russia might be successful in Ukraine is likely to cause Beijing headaches. After all, should Russia win in Ukraine against all odds, Central Asia could be the next target of Putin’s revisionism. China has been massively investing in the oil and gas resources of the region that borders its west. Not only would these interests be put at risk, but resistance fighting and other instabilities could easily spill over the borders into Xinjiang and jeopardize what the Communist Party sees as a currently stable situation in the autonomous region.

And China has also underestimated the economic reactions from Ukraine and the EU. Rising energy prices and the impact of sanctions are putting pressure on the global economy. Combined with China’s real estate and banking crisis, as well as the extreme weather of recent months, this further exacerbates the political situation for the leadership.

So, just before the 20th CP Congress on October 16, Beijing is under more pressure than it has been in a long time. Not only has a military invasion of Taiwan been complicated. The economic integration of Taiwan, which was the preferred objective, has also become more distant due to the rapid deterioration of relations with Taiwan and the United States. The renewed rallying of the allies complicates China’s geopolitical ambitions, and Russia’s unpredictability threatens the stability of the western regions. Last but not least, economic difficulties and the failure of the zero-Covid policy are threatening Xi Jinping’s position within the Party. At the Party Congress, he is expected to be re-elected to his third term as Party Chairman. For him, however, the war in Ukraine has brought one thing above all: uncertainty.

This article is part of the “Global China Conversations” series of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW). On Thursday, September 8, 2022 (11:00 AM CEST), Julian Hinz, trade and sanctions expert at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy and junior professor of International Economics at Bielefeld University, and Marina Rudyak will discuss the topic, “Can China Achieve its 2022 GDP Growth Target of 5.5 Percent.” China.Table is a media partner of the event series.

Marina Rudyak is an interim professor of Chinese politics at Goethe University Frankfurt and an academic assistant for sinology at Heidelberg University. Her research focuses on Chinese development policy, Global China and party discourses of the Chinese Communist Party.

Silas Dreier is coordinator of the Global China Conversations at the China Initiative of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. He is also working on his Master’s degree in China Business and Economics at the University of Wuerzburg.

Elaine Pearson is the new Executive Director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division. Based in Sydney, she will oversee the department’s work in more than 20 countries. Pearson joined Human Rights Watch (HWR) in 2007 and previously served as Deputy Director of the Asia division and then built Human Rights Watch’s Australia office, where she most recently served as the organization’s first Australia director from 2013 to 2022. Pearson has led numerous human rights investigations in the Asia-Pacific region. Prior to HWR, she worked at the UN and numerous NGOs, including in Bangkok, Hong Kong, and Kathmandu.

Richard Tibbels is the new Special Representative for the Indo-Pacific at the European External Action Service (EEAS). Tibbels previously spent four years as Head of the Eastern Partnership, Regional Cooperation (Arctic, Barents, Baltic and Black Seas) and OSCE Division in the EEAS. Prior to that, he held numerous positions in the EEAS and in the European Commission’s Directorate-General, where he managed relations with the EU’s Eastern and Southern Neighborhood. He succeeds Gabriele Visentin, who becomes the designated EU Ambassador to Australia.

Is something changing in your organization? Why not let us know at heads@table.media!

In China, the Yangtze River basin has been affected by drought. Water levels have dropped to their lowest since record-keeping began in 1865 (China.Table reported). In Wuhan, citizens can now even take photos of the exposed pier of the Wuhan-Yangtze Bridge. Due to the persistent heat, the water level dropped up to 18 meters.